CHAPTER 3

A Departure from Their Place

During the winter of 1835 Hannah H. Smith of Glastenbury, New York, obtained a petition printed by an antislavery society in her state asking Congress to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. After affixing her name, she convinced her relatives, Julia E. and Nancy L. Smith, to support the plea by signing their names. The petition then made its way to Pamela and Sarah Hale and then to Mrs. Joseph Wells and her circle of Lucy, Clarissa, Abigail, and Maria. By the time the petition had progressed through town, signatures had been added by clusters of women from various families such as the Collinses, the Hollisters, the Hales, and the Williamses. Elsewhere in the state the women of Marshfield were engaged in similar activities as 107 females scribbled their names on a printed petition form bearing the same words as the Glastenbury petition and sent it off to Representative John Quincy Adams.

During the winter of 1835 and the spring of 1836 the Smiths, the Hales, the Williamses, and other New York women lent their names to a form of petition that designated signers as “ladies” and depicted them “humbly” approaching congressmen. The message they sent Congress was expressed in a mere fifteen lines of print, nine of which were devoted to justifying the unusual behavior of women petitioning Congress on an issue of national policy. The lady petitioners acknowledged “that scenes of party and political strife are not the field to which a kind and wise Providence [had] assigned them.” The women promised that they “would not appear thus publicly, in a way which, to some, may seem a departure from their place.” They assured the congressmen that if the issue were “any matter of merely political interest,” they would remain “silent.” Nevertheless, they were petitioning Congress, they explained, not because it was proper for women to do so but because it was necessary. They were compelled to instruct congressmen, the petition disclosed, because “the weak and innocent are denied the protection of law” and “all the sacred ties of domestic life are sundered for the gratification of avarice.” Knowing of these moral wrongs, the petitioners stated, “they cannot but regard it as their duty to supplicate for the oppressed those common rights of humanity.”

1These 1835 petitions constitute examples of what can be viewed as the first of four major phases of women’s antislavery petitioning. In this initial phase from 1831 to 1836, before passage of the gag rule, women used long forms, often a full page of single-spaced type. Many of these forms were written exclusively for women and employed deferential language to justify the propriety of women petitioning against slavery. In the second phase from 1837 to 1840, abolitionists adopted short, single-sentence forms that could be read quickly on the floor of the House before they were declared out of order. These short forms left no room for elaborate justifications of women’s right to petition and, because they made little or no reference to the gender of the petitioners, were signed by both men and women. After the split of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) in 1840 until passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, women’s petitioning entered a third phase when control of the campaign shifted to the hands of Representative John Quincy Adams. After 1840 women’s antislavery petitioning declined precipitously, though thousands of women continued to lend their names to memorials decrying the Fugitive Slave Law, the annexation of Texas, and the extension of slavery into the territories. By 1854, when women from throughout the expanding nation petitioned against passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the language of their petitions had become much bolder than it had been during the initial phase in the early 1830s. The final surge of women’s antislavery petitioning occurred from 1861 through 1865 when hundreds of thousands of women responded to appeals by the Woman’s National Loyal League to sign petitions requesting emancipation of the slaves and passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.

During the first period of women’s antislavery petitioning from 1831 to 1836, the rhetoric employed in petitions designed specifically to win female signatures attempted to cloak the political nature of signing and circulating memorials. As women crossed into new terrain by petitioning their political representatives in hopes of influencing debate on a national issue, their petitions employed a rhetoric not of newly found political authority but of humility and disavowal. Rather than invoking natural rights principles and demanding the right to petition, over and over again women described their actions as motivated by Christian duty and as an extension of the religious speech act of prayer. As products of the abolitionist crusade, moreover, many women’s petitions were infused with republican and free labor rhetoric aimed at constructing a uniquely northern middle-class conception of citizenship, a conception that relied heavily on notions of virtue and thus elevated the power of woman.

Among the earliest female antislavery petitioning efforts was that of the self-titled ladies of New York who during the summer of 1834 attended mixed-race and mixed-sex antislavery meetings that inspired and organized the circulation of petitions. These women were especially courageous in soliciting signatures, for they defied criticism of the propriety of their behavior as well as threats of violence. When on July 8, 1834, about 50 free blacks of both sexes met with about 100 whites to discuss abolition, the rabidly antiabolitionist

Morning Courier and New York Enquirer lamented that “white women were, we are sorry to say, among the latter.” The editor warned “the colored people of this city” against attending another antislavery meeting scheduled that evening: “No one who saw the temper which pervaded last night, can doubt, that if the blacks continue to allow themselves to be made the tools of a few blind zealots, the consequences to them will be most serious.” As predicted, and probably because the

Courier fanned the flames of prejudice, riots erupted that night. The mob attempted to vandalize the dry goods store of Arthur Tappan, president of the AASS, but was thwarted by a watchman. Unable to lay their hands on Tappan, the crowd turned its anger on free blacks. The African Church on Center Street and the adjoining home of its minister were vandalized as were homes in the free black neighborhood of Five Points. The mob even attacked the Mutual Relief Society Hall on Orange Street, and one black man was robbed of $192, four watches, and several other articles. Despite violence aimed at free blacks in retribution for antislavery activities and the accompanying threat against whites associated with abolitionism, the New York women persisted in circulating an antislavery petition and won 800 signatures.

2That same year elsewhere in the northern states, significant numbers of women began to circulate abolition petitions. Early in 1834, 218 women of Jamaica, Massachusetts, and vicinity asked Congress to enact laws to prevent the slave trade in the District of Columbia and to educate the District’s black children. Months later women in neighboring Boston instructed Congress “to declare every person coming into the District free.” Also in 1834 members of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society began circulating petitions asking Congress to abolish slavery, and a year later the organization formalized plans for circulating petitions for abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia and federal territories. On the frontier of Ohio on February 18, 1834, Mary Ladd joined Henry Ladd, Hannah Harrison joined Miles Harrison, and Eliza Coe joined Lot B. Coe in signing an antislavery petition sent to Congress. About five months later Chloe Richmond shepherded another abolition petition through the women’s circles of Harrisville, Ohio.

3By the spring of 1836 antislavery petitions were circulating in New York, Connecticut, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Ohio. Unlike British abolitionists who employed handwritten petitions, a method that implied spontaneous requests from individual citizens, in the United States officers of both male and female antislavery societies wrote and then usually printed petitions in newspapers and on handbills. British abolitionist Harriet Martineau credited Maria Weston Chapman, a leader in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, with drawing up a form of petition circulated widely throughout Massachusetts as well as other New England states. Chapman’s petition, which Martineau deemed “a fair specimen of the multitudes of petitions from women which have been piled up under the tables of Congress,” decried the sinfulness of slavery and asked Congress not only to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia but also “to declare every human being free who sets foot upon its soil.” It concluded with a pledge to present the same petition to Congress every year, “that it may at least be a ‘memorial of us,’ that in the holy cause of Human Freedom ‘we have done what we could.’”

4Although thousands of women signed antislavery petitions from 1834 to 1836, and although hundreds of separate petitions were circulated, many appeals said exactly the same thing. Sometimes several petitions of the same form were circulated throughout a county and then returned to a petition committee whose members glued the lists of signatures together and topped them with one copy of the form. Other times signed copies of the same form of petition were sewn together with red string. Commonly a single form of petition circulated throughout a state and even through all northern states. For example, the message that the slave trade constituted piracy was sent to Congress in 1836 on identical petitions signed by Patience Chandler in Ohio and Susan Roe in New York.

5Published forms enabled abolitionists not only to circulate large numbers of petitions but also to take advantage of typographical techniques such as bold print and capital letters to call attention to the most important elements of their petition. Lest there be any question as to the nature of the document presented to potential signers or congressmen, the forms often were headed by the word “PETITION” in large, thick letters. Set apart from the text by white space and printed usually in italics or large, upper-case letters came the address: “TO THE HONORABLE THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.” Also set off from the text and often italicized were a line or two indicating the origin of the petition, such as, “The petition of the undersigned Ladies of the County of Orange respectfully sheweth.” Because forms were printed for mass circulation and were used in many different towns and several different states, the printer left blanks for those who circulated the petition to write in the city from whence it originated (for example, “The petition of the undersigned Ladies of _ humbly sheweth”).

Many of the petition forms circulated from 1834 to 1836 immediately indicated whether the petitions emanated from men or women. Petitions printed for women’s signatures represented subscribers as “Ladies,” “Females,” and “Women,” while those printed for men’s signatures denoted the signers as “Citizens,” “Electors,” and “Voters.” When women could not obtain a petition crafted specifically for their sex, they employed standard petitions that represented the signers as “citizens.” But from 1834 to 1836 at least, women understood that it would be controversial to describe themselves as citizens, so they commonly scratched out the label “citizen” and replaced it with “women” or “ladies.” When women signed petitions with men, it could no longer be asserted that the memorial came from citizens. Faced with this situation, canvassers sought a term to represent the status of the signers. Because it was too awkward to write something like “citizens and their female relatives and neighbors,” the petitioners settled for “inhabitants” or “residents” of a certain town.

These labels encoded the perceived political status of potential signers, their authority to instruct elected representatives, and their expectations about how heavily their requests would be weighed. The distinct contrast between labels male and female petitioners applied to themselves is telling. Male abolition petitioners, most of whom were white and enfranchised, asserted their status as voters, electors, and citizens. Female petitioners, however, avoided naming their relationship to the state in the same way as men by consciously rejecting the label citizen. Instead the majority of women presented themselves and expected to be heard as ladies, females, and female citizens. What these differences in naming make clear is that antislavery petitioners understood women to possess a form of citizenship distinct from that of men—a citizenship modified by femaleness.

The hierarchy of gender status in the republic conveyed by the titles subscribers gave to themselves was reinforced by the manner in which the petitions were signed. Throughout the 1830s antislavery petitioners took great pains to maintain strict separation between the signatures of male and female signers. Typeset forms often labeled the left column MALES and the right column FEMALES. Even when the titles were absent and even when canvassers glued several sheets to the bottom of the petition, men signed in the left column, while women signed in the right. This practice might be accounted for as a logical ramification of the ideology of separate spheres; women’s signatures were not intermingled with men’s because they would be a record of improper sexual mixing. Such behavior would have been construed as promiscuous, and the indecorous petition would have been ejected from Congress.

That explanation is inadequate, however, in light of the fact that a number of forms contain three columns of signatures. In such cases the third column is reserved for minors, and there the names of boys and girls are mixed indiscriminately. Abolitionists separated the names of men from those of women and minors, we may conclude, because they believed that men’s signatures—the marks of full, voting citizens—carried greater weight in the eyes of their democratic representatives than those of women, girls, and males too young to vote. We can also conclude that abolitionists thought that adult females were distinct from children. Indeed, on some petitions the columns were labeled LEGAL VOTERS and LADIES. Because the rule of maintaining the separation was almost never violated and instructions to keep men’s signatures distinct were often repeated, it appears that men expected that their requests would be heard in stronger tones than would the pleas of women. Apparently women recognized that they approached their representatives wielding a power different from that of men.

6The purpose of male and female antislavery petitions from 1831 to 1836 was nevertheless the same: to convince congressmen to agree with the request that slavery and the slave trade be ended. Short of provoking Congress to pass an emancipation measure, abolitionists hoped that a constant stream of petitions would stir debate over slavery that would be reported in newspapers and influence public opinion. To meet either of these goals, abolitionists recognized that they must limit the requests of their petitions to the District of Columbia because in 1789 Congress had decided that it possessed no control over slavery in the individual states. Petitions that touched on the regulation of slavery in the states were rejected immediately on the grounds that they were unconstitutional. In response antislavery activists narrowed the focus of their petition campaign to the District, knowing that most representatives recognized the absolute authority of the states but agreed that Congress was charged with legislating for the District. The ladies of New York, for instance, stated in their 1835 petition, “We understand that this District is under the sole jurisdiction of the National Government, who are fully authorized to mold, according to their own will, the provisions of its legislation.” The women also made clear that their intention was not to bid Congress to transcend the constitutional limits of its powers. “It is to the exercise of no doubtful, or contested prerogative that we would move you. With the sovereignty of state rights we ask you not to intermeddle.”

7In addition to Congress, antislavery petitions were aimed at another important audience: potential signers. After all, the canvasser’s first task was to convince women to sign petitions. Failure to justify female petitioning to members of the public among whom petitions were circulated would result undoubtedly in women rejecting entreaties to sign for fear that their reputations would be compromised. Convincing women to sign was no small task because besides the campaign against Cherokee removal, no precedent existed for women’s collective petitioning of Congress. While women’s organizations such as the New York Female Benevolent Society, which sought the charitable goal of building a state-funded asylum for “wandering women,” carried out their petitioning relatively unhampered, the petitioning of antislavery women differed from that of women’s charitable societies. Petitions from charitable societies were almost always limited to seeking money for the poor from local governing bodies. Female antislavery petitions, by contrast, addressed distant male representatives with the goal of instructing them how to deal with the national controversy over slavery. While petitions of benevolent groups encoded an act of humbly requesting or begging a favor from legislators, those from female abolitionists inscribed the action of telling male representatives what to do.

8Besides this implicit assertion of political power, women’s antislavery petitions were liable to criticism as a result of the cause they advanced. Immediate abolitionism was at the radical or “ultraist” extreme of antebellum reform movements. Motivated by religious zeal, male and female abolitionists alike sought to dismantle the institution of slavery and to effect a moral reconstruction of society. Many other women were involved in less drastic reform efforts, such as tract societies, which sought self-improvement or “perfectionism,” while still others, almost exclusively the wealthy, undertook the traditional female work of charity, or “benevolence.” These women drew little criticism for their efforts. Indeed, they were typically praised for meeting their womanly obligations by aiding the needy. Lori D. Ginzberg explains that the goals of ultraist women, among them abolitionists, “provided sufficient excuse for attacks by those who in other settings supported female organizing but who suddenly took a stand against women’s public activity.” In other words, women who signed antislavery petitions risked repudiation not only from those who desired to limit women’s influence but also from those who wanted to arrest the growth of abolitionism.

9These rhetorical constraints necessitated that petitions be written in a manner that potential signers would find so appropriate that they would be comfortable conveying the expressed sentiments to their representatives in the exact words of the petition. Because no one person took credit for writing the petition, by ascribing her name, each signer assumed responsibility for its content. In this way each petition implied a multiple authorship because even though the petition was written by a single person, once it was signed by others, it became authorized as a message from dozens, if not hundreds or thousands, of individual women. A major rhetorical challenge for the authors of petitions, therefore, was to create within the petitions the ethos of those most likely to sign, so that signers could feel confident that the petitions embodied their personal ideas and language.

Far from intruding on the scene of politics, petitions depicted women as assuming a humble stance and politely seeking the attention of representatives rather than making political demands on male authorities. The tone of the petition submitted by the 800 women of New York, for example, was extremely complaisant. “That while we would not obtrude on your honorable body, the expression of our opinions on questions of mere pecuniary expediency or political economy,” they said, “yet we conceive that there are occasions when the voice of female remonstrance and entreaty may properly be heard in the councils of great nation.” The petitioners, who approached as ladies rather than citizens or voters, described themselves as “wives and daughters of American citizens,” constituents who were a step removed from full citizenship. Drawing on the biblical story of Esther, the petitioners reminded their leaders that throughout history “female entreaties . . . have prevailed, even in the counsels of absolute monarchs, whose decrees ‘from India to Ethiopia’ have been supposed changeless as the laws of the Medes and Persians.” The antislavery women said that they were compelled to address their leaders because they feared that the country had been dishonored and would be punished by God. They petitioned not from self-interest, the signers claimed, but for those who could not petition for themselves. Recognizing in every enslaved woman a sister, said the New Yorkers, “[we] plead for her as we would plead for ourselves, our mothers, and our daughters. We plead for our suffering and abused sex.”

10Perhaps the most deferential of all female antislavery petition forms was the “Fathers and Rulers of Our Country” form, which cultivated for its signers a stance of humility and supplication commensurate with the degree to which it was considered acceptable for women to attempt to instruct their legislators. This form was signed by women from almost every northern state and was the most popular of all petition forms employed by abolitionists before 1837. Interestingly, authorship of this form has been attributed to Theodore Weld by the editors of his correspondence, who cite as evidence for this attribution the existence of a printed copy of the Fathers and Rulers form at the bottom of which was scribbled in Weld’s handwriting, “T.D.W. 1834.” Yet in January 1836 the

Emancipator, the official organ of the AASS, attributed authorship of the Fathers and Rulers form to “a woman from North Carolina who was residing in Putnam, Ohio.” Five months later the form was attached to the appeal published by the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Muskingham County, which met in Putnam. Although we cannot know for sure whether the petition was written by the North Carolina woman or by Weld, its rhetoric offers clues about what sort of claims and tone abolitionists believed would appeal to potential female signers.

11Unlike petitions signed exclusively by men, which were addressed “To the Honorable Senate and House,” the Fathers and Rulers form replaced that appellation with “To the Fathers and Rulers of our Country.” Such phrasing elevated the recipients from political representatives to even more powerful figures and diminished the petitioners from constituents to dependents. The text of the petition continued in this supplicatory vein, stating in its first line, “Suffer us, we pray you, with the sympathies which we are constrained to feel as wives, as mothers, and as daughters, to plead with you in behalf of a long oppressed and deeply injured class of native Americans.” Rather than directly stating why they approached their representatives, the petitioners begged and prayed to be heard. The signers implied that they were not even worthy of claiming their own thoughts but that they had been “constrained to feel” those thoughts by some unidentified outside force. After fawning, they switched to flattering: “We should poorly estimate the virtues which ought ever to distinguish your honorable body could we anticipate any other than a favorable hearing when our appeal is to men, to philanthropists, to patriots, to the legislators and guardians of a Christian people.”

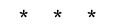

12

Women signers crossed out the word “citizens” in the address and inserted the term “ladies” on this form of petition circulated in Massachusetts during 1834 and presented to Congress in February 1835. (Courtesy of the National Archives)

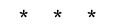

Throughout the 1830s petition signers kept their signatures in separate columns based on their political status. While the names of minors of both sexes were combined, those of adult white males and females were separated because the signatures of electors were understood to carry greater weight with their representatives. (Courtesy of the National Archives)

The Fathers and Rulers of Our Country form reigned as the most common antislavery petition used by women from 1834 until 1837. Although its authorship has been attributed to Theodore Weld, the Emancipator printed the form in January 1836 and ascribed its authorship to a woman from North Carolina who was residing in Putnam, Ohio.

(Courtesy of the National Archives)

This prayerful, supplicatory stance reflected the women’s religious motivation for taking action against slavery. But it also functioned rhetorically to obfuscate the nature of their petitioning, which was public, political, and considered inappropriate for women, by aligning it with praying, which was private, religious, and regarded as entirely appropriate for females. These sentiments were evident in many of the petition forms circulated by women from 1834 to 1836, but nowhere were they more apparent than in the Fathers and Rulers form, which read like a public prayer and described signers as engaging in the speech act of praying. In its opening the petition employed and elaborated on the verb “to pray” twice in short compass. After listing numerous wrongs perpetrated against the slave, the Fathers and Rulers form restated that the petitioners were importuning “high Heaven with prayer, and our national legislatures with appeals,” until “this christian people abjure forever a traffic in the souls of men.” The petition also followed the standard form of prayer by offering a salutation, recognizing the power and goodness of those solicited, stating requests, and concluding with a reiteration of the supplicant’s commitment to the request (such as “amen,” which in essence means “be it really so,” or in the case of the Fathers and Rulers petition, “And as in duty bound your petitioners will ever pray”). The prayerful petition was appended to

An Address to Females in the State of Ohio, published by the Female AntiSlavery Society of Muskingham County, in which Corresponding Secretary Maria A. Sturges wrote, “Let every petition, as it goes forth on its silent embassy, . . . be baptized with prayer, and commended with weeping and supplication to Him in whose hands are the hearts of all men, that he would turn the channel of their sympathies from the oppressor to the oppressed.”

13Aligning the act of petitioning with Christian duty in the texts of petitions was a particularly fitting rhetorical strategy, considering the audience from whom signatures were solicited. While women likely felt hesitant about instructing their representatives on a matter of national policy, undoubtedly they felt more comfortable engaging in the act of praying. Prayer was not only acceptable behavior for women, but it was considered to be the duty of Woman, who was believed to be inherently more religious than Man. Women reformers, abolitionists among them, often prayed and sang hymns at their regular meetings, in addition to holding special “concerts of prayer.” These practices, Julie Roy Jeffrey has noted, “showed not only the belief in the sacred nature of the antislavery cause but how easily women might fall into the familiar patterns of the prayer meeting.” Likewise, Deborah Bingham Van Broekhoven has commented on the similarities between the rituals of signing one’s name to a church membership roll, an earthly recognition that God had written names in “the lamb’s book of life,” and letting one’s “name be enrolled” on the constitution of a female antislavery society to indicate formal membership.

14This is not to suggest that female antislavery petitioners employed religious discursive rituals only, or even primarily, as rhetorical strategies to downplay their increasingly political behavior. There is no evidence to cast doubt on the claims of women signers that they were motivated by moral commitment and Christian duty. In fact, it is unlikely that they viewed religious duty as distinctly separate from political action. The virtually seamless blending of Christian conviction with antislavery activism is illustrated by the words of Catherine Birney when she recalled that prayer was at first woman’s “only idea of aid in the great cause” of abolition. She wrote that men universally granted during the 1830s that prayer was woman’s “special privilege” and encouraged woman to pray as long as she limited her supplications to “private prayer—prayer in her own closet—with no auditor but the God to whom she appealed.” Before long, though, antislavery women sought to intensify their efforts and began to “make their prayers public in the form of petitions to legislatures and to Congress.” It was then, remembered Birney, that the “reprobations began.”

15In hopes of escaping such reprobations, in their antislavery petitions women exhibited extreme deference to elected male authorities, a complaisance absent from those composed for and most often signed by men. Petitions aimed at winning men’s signatures identified signers as citizens and spent no time justifying the propriety of men petitioning their legislators. The tone of men’s petitions, moreover, was declaratory rather than hedging. In a petition submitted to Congress in 1834, for example, Massachusetts men made no apology or explanation for their petitioning. They launched immediately into arguments and declarations that slavery was wrong and should be abolished because it violated laws, and they sternly reminded legislators that Congress possessed jurisdiction over the District. “By the plain words of the Constitution,” the petition stated, “the remedy for these evils, by abolishing slavery, is placed in the power of Congress. No other body can, constitutionally, legislate on the subject.” Whereas women’s petitions often supported claims by alluding to Bible verses, men’s petitions were more likely to cite laws and especially the Constitution. Overall the tone of men’s petitions was legalistic, confident, and insistent rather than, like women’s, religious, tentative, and hedging.

16The noticeably humble stance of women petitioners compared with that of men reflected in part the petition authors’ understanding, which they assumed would be shared by potential signers, that women possessed political status separate from men. Rather than instructing their representatives because it was an exercise of their natural rights or privileges of citizenship, both of which were unclear and unstable, in this first stage with few exceptions women indicated that they petitioned in order to fulfill their Christian duty. An 1834 petition calling for abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia signed by women from Harrisville, Ohio, made it clear that they were doing so “as Christians wishing to act in conformity to the precepts of our Lord.” Even though it was unusual for women to petition about an issue such as slavery, the form stated, women could “no longer keep silent,” and though they were aware that they were violating notions of respectable female behavior, they expected to be protected by “Him that has numbered the very hairs on our heads.” A petition circulated throughout Vermont during 1835 and signed by women proclaimed that as Christians they mourned toleration of slavery and deprecated a system that so clearly violated the “pure and benignant precepts of our Holy Lawgiver.” An 1836 petition signed by females of Winthrop, Maine, stressed upholding Christian principles as a motivation for petitioning: “We believe the time has fully come when this Christian nation should wipe the foul blot of slavery from our national character.” Time and again in this fashion petitions designed to win female signatures called on women as Christians to overturn slavery and invoked Christian duty as a justification for lending their names to the cause. These arguments served a dual function. On one hand, they emphasized that petitioning against slavery was an action motivated by Christian duty rather than political gain. On the other hand, these arguments implied that should a woman refuse to sign, she was neither upholding her religious duty nor acting like a respectable, pious woman.

17Women also professed to petition in order to fulfill obligations based on their connection with other members of their sex, with female slaves. A petition circulated during the fall of 1835 in Massachusetts and New Hampshire emphasized that “your petitioners believe it to be their duty to urge upon your serious consideration the perpetual wrongs of women and children, whose husbands and fathers are deprived of all legal power to protect them.” The women explained that they could not remain silent “while thousands of their sex are condemned to helpless degradation, and even denied the privilege of making known their sufferings.” “History would blush for American women,” the petitioners predicted, “if, under such circumstances, they ever allowed their voice of expostulation and entreaty to cease throughout the land.” Signers from Washington County, Vermont, explained: “As females, we deeply sympathize with the disgraced and afflicted of our sex, and feel constrained by every sentiment of humanity to plead for scourged and heart-crushed woman, whose anticipations of domestic happiness are often ruthlessly blighted by the hand of insatiable avarice, and her dearest ties in life forever severed, while her benighted soul is excluded from a participation in the consoling hopes and sustaining promises of eternal life, and her solitary progress to the tomb unenlivened by one gleam of holy joy.”

18It is not surprising to find in the petitions an emphasis on the similarities between free and slave women. During the 1830s the woman-and-sister appeal permeated a host of antislavery literature directed at women. In its verbal form the woman-and-sister motif stressed that because free and slave women belonged to the same sex, they shared common concerns, such as children, family, domesticity, religion, and sexual vulnerability. These shared relations were conveyed in phrases such as “slaves of our sex,” “am I not a woman and a sister,” and “we are in bonds bound with them” (Hebrews 13:3). In its pictorial form the woman-and-sister motif usually featured a kneeling slave woman who covered her bare breasts with raised arms, clasped her hands, and cast her gaze toward heaven while praying for emancipation. In some depictions the bowing slave woman looked up to an elevated white woman draped in robes and glowing with the light of saving grace.

The woman-and-sister image originated with British antislavery women, who reproduced it in their reports and appeals starting in 1826. In May 1830 Elizabeth Margaret Chandler, who edited the Women’s Repository in the

Genius of Universal Emancipation, an antislavery newspaper published by Benjamin Lundy, mentioned receiving from Englishwomen “a seal, bearing the device of a female kneeling slave, and the very appropriate motto ‘Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?’” In that same issue Chandler, inspired by the image, printed a poem she had composed titled “Kneeling Slave,” in which she contrasted the lady’s pleasant life with the slave’s miserable existence and demanded that the reader work to bridge that gap. By 1832 Garrison had adopted the woman-and-sister image to head the Ladies’ Department of the

Liberator, and the next year Child selected a version of the image as the frontispiece for her

Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans. Thereafter, as Jean Fagan Yellin has noted, American antislavery women “individually and informally, as well as collectively and officially” adopted the image and the motto as their own. They reproduced it in words, in drawings, in needlework, on stationery, and in their petitions.

19The woman-and-sister theme was especially valuable for getting women to empathize with the plight of slaves even though for most northerners slavery was a mere abstraction. Chandler explained the abolitionists’ rhetorical strategy in an article called “Mental Metempsychosis.” Drawing on the concept of metempsychosis, which is the soul’s passage at death into another body, Chandler urged readers to move beyond a mere intellectual response to feel the same cruelties that were inflicted on slave women. Readers, Chandler insisted, should imagine themselves to be slaves in fetters, “its wearing weight upon their wrists, as they are driven off like cattle to the market, and the successive strokes of the keen thong fall[ing] upon their shoulders till the flesh rises to long welts beneath it, and the spouting blood follows every blow.” The woman-and-sister image aimed to make vivid the horrors visited on female slaves and to arouse such emotion that action would be inevitable.

20Descriptions of the horrors of slavery in women’s petitions dwelled on the particular afflictions suffered by slave women. Over and over again, petitions lamented that female slaves were “degraded,” “brutified,” “the victims of insatiable avarice,” “wronged,” and “denied of male relatives to offer them protection.” The ladies of Dousa, New Hampshire, for instance, mourned, “The universal tendency of this system is degradation of the female character; for it unavoidably places a large class entirely out of the protection of law or public opinion. . . . Your petitioners believe it to be their duty to urge upon your serious consideration the perpetual wrongs of women and children, whose husbands and fathers are deprived of all legal power to protect them. They cannot be silent while thousands of their sex are condemned to helpless degradation, and even denied the privilege of making known their sufferings.” These images emphasized the sexual and spiritual vulnerability of the slave woman and implied that slavery was not only the purchase of labor, but also of flesh and soul. The concern of white women over the harsh and indelicate treatment of slave women, at least one critic has concluded, “redefined [slave women’s] suffering as feminine, and hence endowed with all the moral value generally attributed to nineteenth-century American womanhood.”

21For northern women who read the petitions and contemplated adding their names, such language conveyed the notion that slavery gave men unrestrained power over women and that slaveholding men were using their unchecked power in the most evil way. Even though northern middle-class women were far removed geographically from slavery, the image of a man lording villainous power over a sexually vulnerable woman would easily evoke a visceral reaction. A good deal of the literature of antebellum female moral reformers (those involved not in charitable and benevolent work but, rather, in more radical causes) warned that men of all sorts were lustful and licentious and at all times sought to ruin the virtue of women. Ginzberg emphasizes that “one cannot exaggerate the hostility toward men” in female moral reformers’ journals, constitutions, and especially discussions of poverty and prostitution. “Lust appeared to be a disease that had infected the entire male population,” she writes. Prompted by class shifts and economic anxieties during the early to mid-1830s, many radical female reformers harbored intense hostility toward men. Moral reformers argued that women possessed little control over their material wealth and that they were completely dependent on men for their economic well-being. When men failed to do their job, reform literature professed, women were abandoned to become the victims of seduction and vice. The narrative of women being completely at the mercy of men and becoming the victims of men’s inherent licentiousness was echoed by the woman-and-sister theme. By focusing on the ruthless behavior of the slave master toward the defenseless slave woman, the petitions could provoke northern middle-class women to feel the same anger toward the slaveholder that they felt toward the men whom they perceived as controlling their lives through economic power. Yet while the motif enhanced the persuasiveness of antislavery petitions for an audience of northern free white women, it obscured the vast differences between the sexual vulnerability of female slaves and free white women, especially those of the middle class.

22Emphasizing the connection between enslaved African American women and free white women not only provided a means to articulate anxieties about sexual vulnerability that could be appreciated by free white women, but it also provided a crucial rationale justifying white women’s petitioning. The petitions repeatedly stressed that a major reason northern women were obligated to petition for their slave sisters was that slave women could not petition themselves, nor could slave men seek redress for their wives and daughters. Female petitioners from Ohio deemed it “not only our privilege but our duty” to come before Congress “to open our mouths for the dumb” to plead the cause of “the poor and those that have none to help them.” Vermont women declared, “We plead for the enslaved, the smitten, the oppressed!” Vina Wendell, along with 358 other ladies of Massachusetts, complied with the statement that it was her duty as a woman to urge upon congressmen the sufferings of women and children “whose husbands and fathers are deprived of all legal power to protect them.” These arguments implied a narrative of the helpless slave and the valiant liberator, which reinforced the idealized moral superiority of white women by demonstrating that they were acting in a benevolent manner befitting their gender and class.

23Although the emphasis on concern for enslaved women implied a shared identity based on sex, women’s petitions enacted a significant power differential between free women (most of whom were white) and female slaves. As long as the female slave could not petition for herself, the petitions insisted, free women were obligated to petition for them. In this way the rhetoric of female moral duty combined with a certain notion of stewardship was appropriated by free women to elevate themselves from dependents to representatives of those who lacked the autonomy to speak for themselves. By adopting the mantle of public representative of female slaves, abolitionist women in essence reappropriated the political power arrangements between white men and all women. Similar to the rationale that endowed white men with the political power to represent the interests of their dependents—wives, daughters, and sisters—the petitions claimed that free women were qualified to represent the interests of female slaves, who, they claimed, depended on them. In so doing the petitions constructed identities for antislavery women and slave women that intersected along the line of gender but diverged along the line of race. The discursive act of identification, in other words, amounted not only to appropriation but to exploitation. Ironically, the petitions’ radical aim of expanding female abolitionists’ access relied on the conservative rhetoric of woman’s moral superiority. Even more ironic, perhaps, is that despite the fact that petitions served an ultraist movement that professed to seek the overturn of the dominant social, economic, and political structures, the petitions invoked a deeply conservative political vision of indirect representation in an era of growing democracy that privileged a language of direct representation.

24Positioning themselves to represent slaves was but one element of the rhetoric of women’s antislavery petitions that elevated the political power of white and free black women. That small minority of northern women and men who were abolitionists during the 1830s appropriated the issue of slavery to construct a concept of American nationhood built on revised notions of republicanism. Abolitionist rhetoric, as Daniel J. McInerney has demonstrated, insisted on the virtues of an economy built on free labor and critiqued the slave labor system as not only harmful to the republic but defying the principles of the American Revolution. The most common manifestation of the rhetoric of antislavery republicanism in the female forms was the warning that slavery was ruining the nation’s character and that the American people would be punished by God. “As daughters of America, we blush for the tarnished fame of our beloved country,” proclaimed a petition signed by the Females of Washington County, Vermont, in 1836. “We lament her waning glory, and we entreat that you, as patriots, will erase this stain from her dishonored character.” The popular women’s petition attached to the Address of the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Philadelphia declared that slavery was “inconsistent with our declaration that ‘equal liberty is the birth-right of all,’” and thus the signers urged abolition in the District. A petition from the female inhabitants of South Reading, Massachusetts, decried,

That the Congress of the United States—the Representatives of a free, republican and Christian people—in the nineteenth century, and at a period when the nations of the earth are modifying their institutions in favor of the rights and liberties of mankind, should deliberately, and of their own free will and pleasure, declare in the presence of the whole world, their consent to and approval of the extension of the evils of slavery in our land, and of the perpetual and everlasting bondage and degradation of any portion of the human family, would be a blot on our national character that could never be effaced, and a sin which would invoke the judgments of Heaven.

The Ladies of Dousa, New Hampshire, and of Massachusetts argued in 1836 that they considered the toleration of slavery in the District of Columbia as shamefully inconsistent with the principles promulgated in the Declaration of Independence.

25At the root of these apprehensions about the health of the republic was a fear and conviction that the institution of slavery threatened the northern free labor system. Slavery should be abolished in the District of Columbia, argued a popular petition signed by women and men alike, because it was “oppressive to the honest free laborer, and tends to make labor disreputable as well as unprofitable.” The same petition, which was circulated in Vermont, Ohio, and New York, claimed that immediate abolition was practicable because “it will not annihilate the laborers nor their labor, but will merely make it necessary for the employers to pay fair wages.” Men and women of Lockport, New York, ascribed their names to a petition that demanded abolition in Washington, D.C., and the western territories and argued that slavery was “detrimental to the interests and

subversive of the liberties of the labouring population of our republic.”

26Statements about the superiority of free labor in antislavery petitions encapsulated characterizations of virtue and vice familiar to many northern women through their reading of popular novels. During the 1830s Catharine Sedgwick, Sarah Hale, Eliza Follen, and others published novels that boasted that free labor was the fairest system because it allowed all people to rise through hard work. Characterizing northern women as industrious and conscientious while depicting elite southern women as slothful and selfish, these novels functioned as powerful proof of the moral superiority of free labor over slavery. By demonstrating that only the northern free labor system recognized individual independence and natural rights, the novels argued that the North, not the South, preserved the ideals of the American Revolution.

27Female antislavery petitions that featured the idealized moral superiority of woman strengthened abolitionists’ claim to the virtues that constituted the founders’ vision of the republic. Assertions of Christian and womanly duty to speak out against slavery aided abolitionists in condemning slaveholders as morally unqualified to call themselves true republicans and heirs to the legacy of the American Revolution. Slaveholders were, according to abolitionist rhetoric, unfit to be American citizens. In essence, then, antislavery women joined men in decrying wealth, especially wealth gained from slave labor, as a warrant for political power. The radical potential of women embracing in their petitions the rhetoric of antislavery republicanism lay in the fact that northern women could claim the virtues cultivated by free labor and could thus position themselves over elite southerners and especially slaveholding congressmen. As true republicans under the cosmology created by abolitionist republicanism, free laboring women possessed a stronger claim to U.S. citizenship than even the wealthiest, most powerful slaveholding senator. Moreover, it was the duty of the free laboring woman as a citizen to exercise her right of petition in order to safeguard the republic.

It would not be long before the assertion that duties were grounded in the responsibilities of citizenship led to the argument that duties implied rights. Recognizing their roles as moral caretakers and emboldened with republican duty, the women of Harrisville, Ohio, on June 13, 1834, put into circulation an exceptionally bold petition. Bathseba Brown, Susan Hicklen, and others approached their leaders not only as wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters who valued the endearments of domestic life but as “good citizens desiring the prosperity of our nation.” Deeply affected by the “degrading and unprecedented sufferings . . . [of] our brethren of the African race,” the petitioners urged abolition in the District. But they asked for much more:

And believing that the wisdom and calm reflection that should influ-ence the deliberation of those who give laws to nations will be capable of presenting to your minds the incalculable advantages of having your legislative halls surrounded by a pure moral atmosphere; . . . your memorialists further petition for the immediate enfranchisement of every human being that shall tread this soil; that since righteousness alone exalteth a nation, ours may no longer suffer the additional abasement of the foulest stains in the catalogue of our crimes.

28Fourteen years before the Seneca Falls Woman’s Rights convention where the wisdom of seeking woman suffrage was debated, Ohio women petitioned Congress for universal suffrage. The petition, signed by more than thirty-five females, implied that suffrage should be extended especially to women because they were needed to cleanse the nation of the “foulest of stains”—slavery. Although based on essentialized notions of superior female morality rather than natural rights principles, the petition considerably disrupts the widely accepted chronology of American women’s struggle for suffrage. Its existence provides evidence that neither the 1848 Seneca Falls convention nor state constitutional conventions held a few years earlier were the first instances in which women appealed to legislators for enfranchisement. Indeed, the 1834 petition adds yet another piece to what Jacob Katz Cogan and Lori D. Ginzberg have called the “newly emerging puzzle of women’s past political and intellectual lives.” It demonstrates that even as far back as the early 1830s some women rejected the tenets of separate spheres and “dared suggest that only the vote would guarantee them the influence due adult Americans.”

29

The petition of Hannah H. Smith, Sarah Hale, and other ladies of Glastenbury, along with that signed by the ladies of Marshfield, arrived in Washington, D.C., for consideration during the first session of the Twenty-fourth Congress, which convened on December 7, 1835. Besides the New York women’s handiwork, Congress received 174 other antislavery petitions; 84—almost half—were from women, a ninefold increase in female petitions over the preceding session. The pleas had been signed by 34,000 people, 15,000 of whom were women. Faced with more abolition memorials than ever before, Senator John C. Calhoun complained that the petitions came not as in the past, “singly and far apart, from the quiet routine of the Society of Friends or the obscure vanity of some philanthropist club,” but “from soured and agitated communities.”

30The general disposition in Congress toward abolitionists and their petitions was anything but friendly. Like many Americans, members of Congress were fuming over the “incendiary” literature abolitionists had been sending South through the federal mails. With the bloody scenes of Nat Turner’s rebellion emblazoned in their minds, southerners and northerners alike blamed Arthur Tappan and William Lloyd Garrison for inciting Turner and his followers to revolt against their masters. Antiabolitionist sentiment ran so deep that one northern representative, Samuel Beardsley, a Jacksonian Democrat, had been elected to Congress in large part because of his fight to keep antislavery societies from holding their state convention in Utica, New York. Animosity toward abolitionists was compounded by the fact that 1836 was an election year, and northern Democrats who hoped to elect New Yorker Martin Van Buren to the presidency wished to dodge discussion of slavery for fear such talk would upset southern Democrats and voters.

31On December 16, 1835, a little more than a week into the congressional session, Representative John Fairfield of Maine, the first state called upon for petitions, presented a memorial signed by 172 females praying for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade in the District of Columbia. He then moved that it be referred to the Committee on the District of Columbia, which had become the routine way to dispose of antislavery petitions with almost no chance that they would reappear for discussion. Before the motion could be debated, however, John Cramer, a Democrat from Van Buren’s home state of New York, moved that the women’s petition be laid on the table. A companion petition, sent by 172 male citizens of Maine, met a similar fate, though this time it was Fairfield himself who, after presenting the petition, moved that it be tabled.

32Despite the fact that the mood of the House toward abolition petitions was made clear by its treatment of the Maine memorials, two days later Representative William Jackson of Massachusetts presented a petition from sundry inhabitants of the town of Wrentham against slavery in the District of Columbia and asked that it be referred to a select committee. South Carolina’s representative James Henry Hammond, fed up with what he perceived as the constant insult he and his section suffered from the petitions, in a motion unprecedented in the annals of Congress asked that the petition not be received. Hammond explained that he was gratified by the resounding rejection of the abolition petitions two days earlier, and he hoped that the large majority for tabling would convince all members of the impropriety of presenting abolition petitions. Judging from Jackson’s motion, however, Hammond deduced that was not the case. Consequently the South Carolinian asked the House to “put a more decided seal of reprobation on them, by peremptorily rejecting” the petition at hand.

33After Hammond was seated, Representative John Patton of Virginia moved for reconsideration of a petition that earlier had been presented to the House and referred to the Committee on the District of Columbia. He did so because he believed that the only way to get rid of the petitions was to deal once and for all with the question they raised. “Mr. Speaker,” said Patton, “it is necessary that this House should be apprized and fully impressed with the necessity of quieting the anxiety, the agitation, and the alarm for the institutions of the country, which are abroad in the land, and that as the means, perhaps the only means, of doing so, it should meet those questions directly, and dispose of them decisively and permanently.” At this point Representative John Quincy Adams rose to give the first of many speeches on the issue of antislavery petitions. Adams said that he hoped the motion to reconsider would not prevail for the same reason Patton hoped it would. “It appears to me,” Adams stated, “that the only way of getting this question from the view of the House and of the nation, is to dispose of all petitions on the same subject in the same way.” To accomplish this, Adams urged that the House follow the twofold method it had been using for years: first, refer the petitions to a committee that would report on them and, second, unanimously accept the committee’s report. Then Adams issued a dire warning to the House about the consequences that would follow if it decided to discuss the issue of slavery. He predicted that speeches by representatives on the evils of slavery would be turned into incendiary pamphlets that would be printed for the entire country to read.

34The controversy over the treatment of petitions raged for months and pushed aside all other business of the House. The situation became so severe that in February 1836 the House appointed a special committee headed by Representative Henry L. Pinckney of South Carolina, who, like Adams, was a son of one of the framers of the Constitution, to study the petitions and report to the body as a whole. From that day until Pinckney’s committee reported, all abolition petitions were referred to it. On May 18 Pinckney presented the report, which proposed three resolutions aimed at silencing the abolition petitioners. These resolutions were debated by the House for more than a week before members agreed to vote on each separately. On May 25 the House approved by a vote of 182-9 the first resolution, which held that Congress possessed no constitutional power to interfere with slavery in any of the states. The next day the second resolution, stating that Congress ought not to interfere with slavery in the District of Columbia, was approved by a vote of 142-45. Then the vote was taken on the third resolution, which read, “

Resolved, That all petitions, memorials, resolutions, propositions or papers, relating in any way, or to any extent whatever, to the subject of slavery, or the abolition of slavery, shall, without being either printed or referred, be laid upon the table, and that no further action whatever shall be had thereon.” This resolution would come to be known as the gag rule. When Adams was called to vote, he rose and exclaimed, “I hold the resolution to be a direct violation of the constitution of the United States, the rules of this House, and the rights of my constituents.” Calls of order rang out from all parts of the hall as Adams took his seat. The resolution was adopted by a vote of 117-68. For the rest of the first session of the Twenty-fourth Congress, which lasted until July 4, 1836, abolition petitions were tabled upon presentation.

35

After passage of the gag rule, abolitionists faced a strategic decision. Should they cease to petition? After all, was not petitioning a waste of time, since Congress tabled the memorials without considering the requests? Quite to the contrary James G. Birney, a repentant Kentucky slaveholder, recommended that “every effort ought to be made to get up petitions for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia.” Birney believed that petitioning would be a forceful, persuasive strategy because southern congressmen treated antislavery petitions with such “rabid contempt” that the people would see clearly that slaveholders would protect their peculiar institution at any cost, even by trampling northerners’ rights. Petitioning, Birney stressed, “would give us a great means of moving people.” In order to stimulate even greater petitioning activities, antislavery societies published addresses appealing to abolitionists to circulate petitions despite the affront in Congress. It was at this time that female antislavery societies joined the petition drive in earnest. In fact, passage of the gag rule inspired women abolitionists to produce a major outpouring of discourse aimed at encouraging female activism and articulating in greater detail an emerging ideology of female citizenship.

36