CHAPTER 4

A Firebrand in Our Hands

Passage of the gag rule incensed abolitionists. As soon as a copy of the report that proposed and justified the gag rule reached Boston, it was splashed over the pages of the

Liberator. The Pinckney report, editorialized Garrison, was “weakness itself.” Early in July 1836 the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) published

An Appeal to the People of the United States in hopes of attracting to the antislavery cause Americans who were unsympathetic to abolitionism but who cherished the First Amendment. “Let no one think for a moment that because he is not an abolitionist, his liberties are not and will not be invaded,” the

Appeal warned. Angered by what they perceived as a bald abrogation of their constitutional rights, abolitionists denounced Pinckney as “foolish and infatuated” to suppose that his report would induce them to cease agitating the slavery issue. Instead they pledged that the rule “shall be a ‘firebrand’ in our hands to light anew the flame of human sympathy and public indignation.”

1Garrison and the AASS were not alone in seizing the “firebrand” of the gag rule to ignite public indignation. Passage of the first gag rule also inspired female abolitionists during the summer of 1836 to issue calls for intensified petitioning and to denounce slaveholders for conspiring to trammel northerners’ civil rights. In four major printed addresses female abolitionists elaborated at length on their justifications for petitioning, situating this form of political influence in a broad discussion of women’s proper role in antislavery activism. Although representatives passed the gag rule to silence abolition petitioners, instead the rule functioned as a catalyst for female antislavery leaders, who in their addresses constructed the Pinckney resolution as an immoral law enacted by morally flawed men. The addresses repeatedly instructed women to ignore the will of men who wished to suppress their pleas and to follow their own moral conscience with respect to the sin of slavery. The implications of these appeals were radical, for they urged women to trust their own judgment and to abandon millennia of customs and law requiring women to submit to the desires of men.

The 1836 addresses persuaded more women to lend their names to the cause, which contributed significantly to the success of the campaign that in December of that year deluged Congress with abolition petitions. Aggravated congressmen reacted by instituting a second gag rule, refusing to receive a petition from slaves, and questioning the right of free blacks to petition. In response female abolitionists, determined to multiply the number of names submitted to Congress and concerned about the security of their right of petition, took the unprecedented step of meeting in convention. At their convention, which marked the beginning of the second phase of female antislavery petitioning, women practiced important skills of political organizing, such as running meetings, forming networks, debating resolutions, and writing circulars. The convention also provided an opportunity for women to debate what constituted their appropriate role in the antislavery cause and to formulate justifications of their expanding activism. These justifications were articulated in published resolutions and addresses that, unlike the 1836 appeals, advanced beyond claiming that women possessed a moral duty to petition to asserting that women were citizens and, as such, possessed a constitutional right to petition. Antislavery women also asserted a bolder, more straightforwardly political identity in the new petitions they adopted at the convention. These petitions were much shorter than those circulated in the first phase of female involvement and left no space for women to excuse their petitioning as motivated by female duty. Not only did women cease offering elaborate justifications for their petitioning, but they more frequently signed the same forms that men signed.

Though the Pinckney gag was intended to deter antislavery petitioning, it inspired an outpouring of discourse in which female abolitionists encouraged women to follow God’s will to eradicate the sin of slavery and called on them to defy political representatives who wished to quell the petitions. Women’s alleged moral purity freed them from political motivations that corrupted congressmen, the 1836 addresses argued, urging them to ignore the dictates of men who opposed their petitioning and to follow their own consciences to instruct representatives to abolish the evil of slavery. While the addresses extended moral appeals to inspire women to increase their antislavery activism, they also bemoaned denial of northerners’ civil rights, which eventually led to particular defenses of women’s right of petition based on constitutional arguments. Among the addresses was that of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, published in July 1836 and likely written by Maria Weston Chapman, that lamented that with passage of the gag rule, “we may not know whether the men we call our representatives are truly such.” Approval of the Pinckney resolution, it decried, made the whole nation “feel the Slave-holder’s scourge.” It nonetheless urged, “Let us petition;—petition, till, even for our importunity, we cannot be denied. Let us know no rest till we have done our utmost to convince the mind, and to obtain the testimony of every woman, in every town, in every county of our Commonwealth, against the horrible Slave-traffic.” A month earlier Maria A. Sturges, corresponding secretary of the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Muskingham County, Ohio, and coordinator of women’s antislavery petitioning in her state, had published

An Address to Females in the State of Ohio, which was circulated as a handbill throughout Ohio, reprinted in the

Philanthropist and the

Emancipator, and sent to New England female antislavery societies. In August, Angelina Grimké published her

Appeal to the Christian Women of the South, which was sold as a pamphlet in both the United States and England. In mid-October there appeared

An Address of the Female AntiSlavery Society of Philadelphia to the Women of Pennsylvania with the Form of a Petition to the Congress of the U. States, signed by the organization’s president, Esther Moore, and its secretary, Rebecca Buffum. In addition to advancing arguments about slavery and the importance of petitioning, the addresses sought to accomplish the practical tasks of distributing petition forms (the Ohio appeal, for example, included the Fathers and Rulers of Our Country form) and providing directions for their circulation.

2Passage of the gag rule presented an added constraint to female petitioning efforts, for it compounded general negative attitudes toward women’s collective petitioning with congressmen’s formal disapproval of abolition petitions. In response the appeals repeatedly urged women to ignore the will of men who attempted to thwart their petitioning. “Women are not excused from obedience to the Apostolic injunction, ‘

Remember them that are in bonds as bound with them,’” preached the Ohio

Address, bidding women to “labor with untiring vigor” for the slave because the Bible promised that on the day of revelation, “not our sons only, but our daughters shall prophesy.” If women were to share in the blessings of the coming of the Lord, the

Address reminded, “surely it must be our duty, as well as privilege, to be auxiliaries in accelerating it.” Grimké invited women to ignore man’s laws and man’s opinions and to take as their sole source of guidance the word of God as they interpreted it. Women should not follow the lead of men if they believe male direction to be immoral, she advised. In fact, they should resist the will of men to satisfy the will of God even if it meant sacrificing their lives just as biblical women such as Miriam, Huldah, Anna, Deborah, and Esther had “stood up in all the dignity and strength of moral courage to be the leaders of the people, and to bear a faithful testimony for the truth whenever the providence of God has called them to do so.”

3Furthermore, the addresses emphasized that given the sectional and partisan nature of debates over slavery and the gag rule, because of their alleged moral purity, women were uniquely qualified to petition for an end to the moral evil of slavery. Women, stated the Ohio

Address, were particularly suited to send antislavery petitions to Congress because they remained “untrammeled by party politics, and unbiased by the love of gain,” while men, on the other hand, were “ready to prostrate themselves before the swift running car of this mighty Juggernaut which slavery hath set up.” The

Address to the Women of Massachusetts claimed that it was especially incumbent upon women to counteract the “hatred of [God’s] character and laws” that was “intrenched in

men’s business and bosoms.” “As

wives and

mothers, as

sisters and

daughters, we are deeply responsible for the influence we have on the human race. We are bound to exert it; we are bound to urge men to cease to do evil, and learn to do well.” Women’s petitions would be “irresistible,” assured Grimké, “for there is something in the heart of man which

will bend under moral suasion.” Even if only six signatures could be obtained on a petition, she urged women to “send up that petition, and be not in the least discouraged by the scoffs and jeers of the heartless, or the resolution of the house to lay it on the table.” Women should persevere because they could introduce the subject of abolition “in the best possible manner, as a matter of

morals and

religion, not of expediency and politics.”

4Perhaps most significantly, the addresses warned that slaveholders were conspiring to destroy northerners’ civil rights and included women’s right of petition among those guaranteed by the Constitution. The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society’s appeal deplored that because of the gag rule, “the whole nation is being made to feel the Slave-holders’s scourge” and that the “Slave-system” caused the “institutions of the free” to break down, and thus the lives of those who avowed the principles of the Declaration of Independence were threatened. The Ohio address cited the gag rule as evidence that northern members of Congress were plotting with slaveholders and were willing “to appease the blood-stained god of southern slavery.” By advancing these arguments, the women’s addresses contributed to propagation of what Russell Nye has called the “great slave power conspiracy theme,” which, after taking root in abolitionist discourse in the 1830s, became a primary weapon in the abolitionist rhetorical arsenal during the 1850s. Gradually abolitionists—women and men—began to claim, as would Abraham Lincoln some years later, that the Union could not exist half-slave and half-free. Although Nye credits only male abolitionists with perpetuating the conspiracy theme, decades before Lincoln would speak nearly the same words, the Boston women’s address warned, “Weak and wicked is the idea, that union in oppression is possible. Every nation that attempts it, ‘God beholds, and drives asunder.’”

5Not only did the appeals advance the slave power conspiracy theme, but in the course of decrying destruction of northerners’ civil liberties, the Philadelphia address advanced beyond claiming that women possessed a moral duty to petition to asserting that women were citizens endowed with a constitutional right of petition. “Will you say that woman’s duties lie within the hallowed precincts of home, not in the field of controversy, or the halls of Congress?” the Philadelphia address asked readers. Employing arguments used to deny women access to public debate, the address accused congressmen of corrupting the deliberative process by letting “loose the storms of passion . . . instead of listening to the voice of woman’s entreaty for the rescue” of the slave. Congressmen, the Philadelphians complained, “would fain rob her of the right of petition, and the privileges of a citizen, in order to close her lips for ever in behalf of her outraged sisters.” In the course of calling women to petition, again and again the Philadelphia address asserted in no uncertain terms that women were citizens and must fulfill the duties incumbent upon citizens. This was no time for women to “keep silence,” no time “for

woman to shrink from her duty as a citizen of the United States,—as a member of the great human family.” “As Northern citizens

we are bound, dear sisters, to put forth all

our energies in this mighty work. Yes, although we are

women, we are still citizens, and it is to

us, that the captive wives and mothers, sisters and daughters of the South have a peculiar right to look for help in this day of approaching emancipation.”

6

Inspired by appeals published by women during the summer of 1836 after passage of the gag rule, during the fall northerners sent to Congress more antislavery petitions than ever before. When the second session of the Twenty-fourth Congress convened on December 5, 1836, congressmen found that despite the Pinckney report and resolution of the last session, the petition issue had not gone to sleep. So “conspicuous” were the “sedative properties” of the gag rule, John Quincy Adams remarked facetiously in his diary, that in the new session of Congress “it multiplied fivefold the antislavery petitions.” When the first abolition petition was presented on December 26, the Speaker of the House, Tennessee slaveholder and future president James K. Polk, decided that the rules and resolutions of the last session, including the gag rule, had expired. That meant that abolition petitions were no longer tabled immediately upon presentation; the floodgates were opened, and antislavery memorials washed into the House. As in the preceding session, debates over how to dispose of the abolition petitions dragged on. Much time was spent dealing with the petitions, and other business of the House ground to a halt. Finally, on January 18, Representative Albert G. Hawes of Kentucky moved for adoption of a resolution with the same wording as the previous gag rule. After no debate the resolution was adopted by a vote of 129-69.

7Passage of the resolution, however, did not keep Adams and others from presenting abolition petitions. On February 6, for example, Caleb Cushing of Massachusetts presented a petition signed by 3,824 ladies of the city of Lowell and the towns of Amesbury, Andover, Haverhill, Newburyport, Reading, and Salisbury. He also presented petitions signed by women from twenty-seven towns in New Hampshire. All were received and, under the Hawes resolution, laid on the table. The effect was “electrical” when time after time a few members to whom the memorials had been entrusted rose to state the content of the petitions. “If a nest of rattle-snakes were suddenly let loose among them,” reported a Capitol observer during the first days of 1837, “the members could manifest but little more ‘agitation’—except perhaps, that they retain their seats a

little better. . . . The Southern hotspurs are almost ready to dance with very rage at the attack, as they called it, upon their peculiar domestic institutions.”

8But the greatest commotion was caused by Adams, who on February 6 presented a petition from nine free black women of Fredericksburg, Virginia, and inquired of the Speaker whether it would be acceptable to present a second petition signed by twenty-two persons purporting to be slaves. Polk referred the question to the House, igniting a fiery debate over whether slaves possessed the right of petition. Immediately after the inquiry about the alleged slave petition, “the torrid zone was in commotion,” Adams recalled. He heard “half-subdued calls of ‘

Expel him, expel him’” from various parts of the chamber. One southern member declared that should any representative “disgrace the government under which he lived” by presenting a petition from slaves for their emancipation, the House should order the petition “committed to the flames.” The man who presented such a petition, pronounced another, also should be consigned to the combustion. Invectives such as these were restated as formal resolutions condemning Adams’s behavior and denying adamantly that slaves possessed the right of petition. One such resolution offered to the chamber by Representative Bynum of North Carolina stated “that any attempt to present any petition or memorial, from any slave or slaves, negro or free negroes, from any part of the Union, is a contempt of the House, calculated to embroil it in strife and confusion, incompatible with the dignity of the body; and any member guilty of the same justly subjects himself to the censure of the House.” Bynum’s resolution expressed slaveholders’ distaste for petitions from slaves and free blacks, but it did not explicitly deny slaves the right of petition. That task was left to Representative John M. Patton of Virginia:

Resolved, That the right of petition does not belong to the slaves of this Union, and that no petition from them can be presented to this House, without derogating from the rights of slaveholding states, and endangering the integrity of the Union.

Resolved, That any member who shall hereafter present any such petition to the House, ought to be considered regardless of the feelings of the House, the rights of the South, and an enemy of the Union.

Patton’s resolution went beyond claiming that it was improper for slaves to petition and stated clearly that slaves had no right of petition. While the precedent for denying slaves the right of petition had been set in 1797, Patton’s resolution also indicted the goodwill and patriotism of representatives who would present slave petitions, thus censoring members’ right of free speech. In the end the House debated a resolution brought forth by Representative Charles Jared Ingersoll of Pennsylvania that proclaimed that the body could not receive the slave petition “without disregarding its own dignity, the rights of a large class of the citizens of the South and West, and the Constitution of the United States.”

9Adams responded systematically to each averment. Rather than disregarding the dignity of the House, Adams argued, receiving the petition would maintain its dignity. Most Americans would view a refusal to hear a petition, said Adams, as “beneath the dignity of the General Legislative Assembly of a nation, founding its existence upon natural and inalienable rights of man.” The petition did not encroach on the rights of southern and western citizens because although it was purportedly from slaves, it prayed for the preservation of slavery, and likely came from slaveholders. Adams’s revelation incensed southern members, who saw themselves as the butt of a parliamentary practical joke.

In the course of his response to the claim that the Constitution denied slaves the right of petition, Adams argued that the Constitution “expressly forbids Congress from abridging, even by

law, the right of petition, and which, not by the remotest implication, limits that right to freemen.” He urged congressmen and their constituents to read the Constitution, where they would find that “in a compact formed for securing to the people of the Union the blessing of liberty,” in respect to decency there is no use of the word “slave.” Instead, every allusion to slaves employed the word “persons,” and according to Adams these persons were recognized as members of the community and as human beings who possessed rights. “Their right to be represented in Congress is admitted,” he maintained, “even in the provision which curtails it by two fifths, and transfers the remainder to their masters.”

10After lengthy debate the House adopted by wide margins Ingersoll’s and another resolution denying slaves the right of petition. Passage of these resolutions constituted an important chapter in the continuing negotiation of the meaning of the right of petition and the meaning of U.S. citizenship. The event demonstrated that when it came to controversial issues such as slavery, Congress was capable of denying the right of petition outright to certain classes of the nation’s inhabitants, namely slaves. Debate over whether slaves possessed the right of petition raised other fundamental questions: Is the right of petition linked to citizenship? Are slaves citizens? Is a person denied the right of petition a citizen? The decision to deny slaves the right of petition, moreover, left open the possibility that because of the questionable citizenship status of women, their right of petition was vulnerable to similar incursion. After all, Bynum’s resolution called for any attempt to present a petition from “a negro or free negroes” to be ruled in contempt of the House. As Adams warned, the deprivation of the right of petition in the case of slaves “yields a principle that may be applied in numberless others, till the whole right of petition shall, . . . be numbered among the

spoils of victory—the exclusive possession of the dominant party of the day.” Because women’s political status remained unclear, their right of petition could easily be challenged (and as we shall see, it was). This debate over slaves’ and free blacks’ right of petition supports Jan Lewis’s observation that during the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century, “women’s membership in civil society would be defined in relationship to that of free blacks.” She notes in particular that “the understanding of women’s civil rights emerged most clearly in discussions about attempts to limit the civil rights of free blacks.”

11

Outright denial of slaves’ right of petition combined with passage of a second gag rule outraged abolitionists, especially abolitionist women, thousands of whom had circulated and signed the petitions that were tabled. Abuses hurled by southern congressmen against the petitioners and disrespectful treatment of the venerable Adams did little to discourage antislavery women from petitioning. Instead they sought to streamline petitioning into a more effective operation. Female abolition leaders recognized that the haphazard approach of leaving petitioning to local antislavery societies would not suffice. One problem with allowing local societies to run the campaign was that often volunteers started gathering signatures too late for petitions to reach congressmen before the deadline for presentation. In some cases, moreover, congressmen alleged that the petitions bore false signatures, an accusation abolitionists could not refute without a systematic plan for checking the names. A further weakness was that the memorials circulated by local societies were drawn up by individuals who often lacked the rhetorical acumen necessary to compose petitions befitting presentation to Congress. Instead, petitions written by local male and female antislavery societies often employed harsh language to which more than one congressman took offense. In addition, rather than strategically selecting a sympathetic representative to present the petitions, local volunteers sent hundreds of legitimate petitions to their own congressmen, many of whom were hostile to abolition and refused to introduce the memorials. As a result, hours of grueling work spent persuading people to sign petitions were completely wasted.

12In response to events in Congress and to rectify problems with the signature-gathering process, leaders of several New England female abolition societies suggested the idea of coordinating petitioning to the next session of Congress. On August 4, 1836, Maria Weston Chapman, corresponding secretary of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, sent a letter to Mary Grew, her counterpart in the Philadelphia Female AntiSlavery Society, proposing formation of “a general executive committee” to systematize the work of petitioning. Grew replied that the Philadelphia society found the idea “expedient and desirable” but noted that some members of her society “would much prefer a recognition of female members and delegates in the American Society.” The Boston women responded by suggesting that a national female convention be organized in May 1837 at the same time and in the same city as the meeting of the AASS. The Philadelphia organization then sent a letter to female antislavery societies throughout Pennsylvania and another missive to Methodist women inviting them to participate in the convention.

13Likely these invitations were greeted with surprise because during the 1830s the notion of women meeting in convention to debate and to pass resolutions was highly unusual. Women commonly gathered in parlors and churches to participate in sewing circles, literary organizations, and charitable societies, but seldom had American women from several states assembled to discuss a controversial public issue such as the abolition of slavery. In fact, the 1837 female antislavery convention likely was the first public political meeting of American women and, as Dorothy Sterling has noted, “the first interracial gathering of any consequence.”

14The dearth of women’s conventions at a time when such gatherings had become an effective means for influencing public opinion can be explained by the abundance of warnings against females holding such meetings. Newspapers and ladies’ magazines published satirical accounts of women meeting in fictitious conventions to discuss trifling issues such as fashion and the availability of husbands. In 1812 an article in Philadelphia’s

Lady’s Miscellany, for example, portrayed women as collectively petitioning the legislature against efforts “to deprive them of the indefeasible right of dress.” Articles such as these published during the early national period, Rosemarie Zagarri explains, were meant to stifle women’s growing political aspirations by implying that women were foolish and could not possibly deliberate. During the Jacksonian era even radical male reformers, including abolitionists, curtailed full female participation in conventions. When, for example, sixty-four men gathered in Philadelphia during the first week of December 1833 to found the AASS, four women observed the proceedings. Of these four women—Lucretia Mott, Lydia White, Esther Moore, and Sidney Anne Lewis—only Mott spoke, and she did so during only one meeting. Mott’s oratorical outburst was so unusual that a male delegate recalled, “I had never before heard a woman speak at a public meeting.” Male abolitionists expressed appreciation for Mott’s contributions; but none of them recognized the women as full delegates, and no woman was invited to sign the organization’s founding document, the Declaration of Sentiments.

15Nevertheless, female antislavery leaders were familiar enough with the process of holding conventions that they followed the accepted practice of publicizing their meeting by issuing a circular. The convention circular, likely written by Chapman, was published in March 1837 by antislavery newspapers such as the

Liberator, the

Emancipator, and the

Friend of Man. Like the circular issued before the founding convention of the AASS, a major goal of the women’s call was to attract a large number of participants, which would appear to reflect public opinion in the free states. But unlike the AASS’s call, the women’s announcement needed to overcome both the unpopularity of abolitionism and the taboo against females attending conventions. Rather than protest too much by directly addressing the issue of propriety, the call portrayed meeting in convention as a common and acceptable thing for women to do. “We believe there will be hundreds, if not thousands of the women of New England, whose gushing sympathies will impel them to attend this convention, to join the glorious company of faithful women who will be there assembled,” the circular proclaimed.

16The major argument of the circular was that because women in particular suffered the effects of slavery, women were especially responsible to work for emancipation. Chapman’s rhetorical strategy was to appeal to the self-interest of her readers by demonstrating for her primary audience of northern white women that they were affected by slavery both as mothers and as women. She appealed to women as “mothers of New England,” asking if they could passively “send your sons abroad in the world, exposed to the scorching fires of temptation enkindled by slavery, while you are doing nothing to quench the flame.” Every year, Chapman warned, young men born and bred in the North visited the South, where they were “soon swallowed in the whirlpool, in which they sink to rise no more.” Nor, she warned, were the “blighting influences” of slavery confined to the South. Every summer slaveholders came North to evangelize their proslavery ideals: “They call evil good, and bitter they call sweet. . . . They put light for darkness, and darkness for light, and accustom their northern friends to do the same.” Women had to put aside their fears of impropriety in order to save the nation, Chapman claimed, because if they “sleep over the iniquities of slavery for another generation, . . . they will leave their children exposed to God’s severest judgments.”

17In addition to appealing to her readers as mothers and moral individuals, Chapman emphasized the horrid effects slavery wreaked on women as a group. Slavery, she charged, held “more than a million of our sisters” in an unholy institution where they were unable to find “protectors who can perform the duties of a husband.” Thus slave women were left “down in a state of universal prostitution” and faced “punishment of death, if they presume to protect themselves.” This argument, which was employed often by women abolitionists in their petitions to Congress, drove slaveholders apoplectic with anger. It violated southern gentlemen’s implicit agreement that sexual relations with slaves were acceptable as long as they remained unmentioned in polite company. It insulted the honor of slaveholding men, their wives, and their legal children. As such, it appealed to northerners’ sense of moral superiority over southerners.

18To bolster the circular’s call for a convention, the

National Enquirer defended the unusual event by emphasizing that the antislavery movement needed woman’s moral power. The editors ridiculed anyone who would balk at the idea of a female convention. New modes of proceeding were necessary at this time, they proclaimed, because abolitionists sought to remove a “stupendous mountain of evil” so as to accomplish an important reformation. The convention of women was necessary for the abolition movement because “every avenue, hitherto open, has been studiously barricaded. Other means are requisite to bring our artillery to bear upon the Bastille of despotism.” The

Enquirer was especially desirous of selecting a new site on which to “erect the lever of moral power” for the “overthrow and annihilation” of slavery. “Let no genuine Female Philanthropist hold back, from a timid apprehension of exceeding the limits of propriety, of deviating from the acknowledged principles of female duty, or of transgressing the legitimate privileges and immunities of her sex,” the newspaper exhorted. Indeed, the editors concluded, “We look forward with the pleasing expectation, that a mighty convocation of female piety, philanthropy, and talent will be witnessed.”

19On Tuesday, May 9, 1837, 71 delegates gathered in the Third Free Church at the corner of Houston and Thompson Streets for the First Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women. In addition to the delegates, the convention was populated by 103 corresponding members, who attended in an unofficial capacity and were allowed to vote. The largest representations came from Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, both of which sent 22 delegates. New York sent 19; Rhode Island, 3; New Hampshire and Ohio, 2 each; and New Jersey, 1. Membership of the convention was 94 percent white, and the makeup of corresponding members was 84 percent white. Among the African American women attending were Maria Stewart, who was living in New York, as well as Philadelphians Sarah Mapps Douglass and Grace Douglass. Mary S. Parker was elected president of the convention due in large part to the fact that she was president of the influential Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, which had achieved singular success in its petitioning efforts. The convention chose six vice-presidents: Mott (Philadelphia), Grace Douglass (Philadelphia), Lydia Maria Child (Boston), Abby Ann Cox (New York), Sarah Grimké (representing South Carolina), and Ann C. Smith (New York). Four secretaries were also selected: Mary Grew (Philadelphia), Angelina Grimké (representing South Carolina), Sarah Pugh (Philadelphia), and Anne Warren Weston (Boston). Women who had gained leadership skills and confidence in local antislavery societies refused Theodore Weld’s offer to help them run the first national female convention, telling him that they had “found that they had

minds of their own and could transact their business

without his direction.”

20“Petitions to Congress,” the convention resolved, “constitute the one central point to which we must bend our strongest efforts.” The women set as their main goal “to collect a million signatures on petitions calling on Congress to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia and in Florida.” The convention discussed a systematic plan for circulating petitions to achieve this goal. Child proposed establishing three Central Committees with whom abolition workers could correspond. These committees were to be anchored in the major urban centers and included Grew, Pugh, Sarah Mapps Douglass in Philadelphia; Rebecca Spring, Juliana A. Tappan, and Anna Blackwell in New York City; and Chapman, Henrietta Sargent, and Catharine Sullivan in Boston. State antislavery offices were to appoint one woman in each county who would in turn name one woman in each town in her county to whom the Central Committee could send blank petitions. Cities were to be divided into districts, and antislavery women were directed to “visit every house and present every female over sixteen years of age, a petition for her signature.” Rather than sending the petitions from cities and towns directly to congressmen, as had been the practice, they were now to be forwarded to the county coordinator, who would check the signatures. From there the petitions were to go to the state committees, where they would be counted, recorded, and sent to Congress. After the petition plan was discussed and agreed on, “the Free States were called in rotation, and from most of them pledges were given by their daughters rising to the call, and promising their exertions in this cause.”

21The fact that the women adopted a detailed plan of petitioning at their May 1837 convention has been overlooked by historians who attribute invention of the petition strategy to AASS men who met at the same time and in the same city. Not only did women precede men in organizing their petitioning, but it is likely that the AASS derived its national campaign strategy from the method instituted by the women. It was only after the conventions had adjourned and after the women’s plan had been published that Weld, John G. Whittier, and Henry Stanton went about the task of organizing the AASS petition campaign. Their plan, developed for the most part by Stanton, was remarkably similar to the one implemented by the women’s convention. Indeed, it is plausible that Stanton used the women’s plan as a model, for by the time he was charged with developing a petition scheme for the AASS, Stanton was familiar with the Boston women’s system of collecting signatures. In November 1836 he had reported to the Rhode Island Anti-Slavery Society convention that “the ladies of Boston had districted the whole state [of Massachusetts] with reference to the circulation of petitions” and had succeeded in gathering twice as many names as their male counterparts.

22Along with instituting a petitioning strategy for the free states, much of the 1837 female antislavery convention was devoted to discussing whether it was proper for women to partake in various forms of antislavery activism such as petitioning. The discussion was long overdue because women had been attacked by the clergy and others for petitioning and otherwise stepping outside their proper sphere to do the work of abolition. Because convention participants varied in class, race, and regional and religious backgrounds, they far from agreed on what constituted acceptable boundaries of female activism. At the vanguard was Angelina Grimké, who, like Mott and the other Philadelphia delegates, was comfortable with females exerting themselves on behalf of moral causes, due perhaps to her association with Quakerism. Grimké offered a resolution stating that certain rights and duties were “common to all moral beings” and that the time had come “for woman to move in that sphere which Providence has assigned her, and no longer remain satisfied in the circumscribed limits with which corrupt custom and a perverted application of the Scripture have encircled her.” It was the duty of woman, the resolution maintained, “to plead the cause of the oppressed in our land, and to do all that she can by her voice, and her pen, and her purse, and the influence of her example, to overthrow the horrible system of American slavery.”

23But Grimké’s assertion of women’s natural rights and the claim that scripture had been “perverted” was too strong for some delegates. According to the convention minutes, her resolution touched off an “animated and interesting debate.” After several amendments were offered, the resolution was adopted without changes, though as the proceedings noted, “

not unanimously.” Twelve women were in such deep disagreement with Grimké’s resolution, which in essence redrew the proper sphere of female activism, that they voted against its adoption and asked that their names be recorded in the minutes as disapproving parts of the resolution. Ten of the twelve negative votes came from New York City women who were Presbyterians and Methodists, denominations that tended to be less radical than their Quaker and Unitarian counterparts in Philadelphia and Boston. Later in the convention, in the interest of unity Child tried to resuscitate discussion of the province of woman by moving that Grimké’s resolution be reconsidered, but the motion was defeated. Then Cox and Spring, both from New York, attempted to make peace by offering a resolution couched in the acceptable terms of motherhood. Cox stated, “There is no class of women to whom the anti-slavery cause makes so direct and powerful an appeal as to

mothers.” Cox encouraged mothers to “lift up their hearts to God on behalf of the captive,” not only because they could sympathize with the slave mother’s condition, but also to guard their own children from evils of slavery and prejudice. Cox’s resolution was approved unanimously. The unhampered passage of Cox’s resolution based on the duties of motherhood as opposed to the troubled journey of Grimké’s resolution based on the notion that women and men possessed common rights and duties demonstrated that many antislavery women did not view rights as grounded in individuals but as deriving from their collective status as women.

24Undaunted, Grimké presented another resolution stating that “the right of petition is natural and inalienable, derived immediately from God, and guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States.” Grimké’s resolution was a condemnation of the House’s passage some three months earlier of measures that denied slaves the right of petition. In an attempt to establish the rights of both abolitionists and women to petition, the resolution further stated that the delegates regarded every effort by Congress to abridge the sacred right of petition, whether exercised by a man or a woman, the slave or the free, “as a high-handed usurpation of power, and an attempt to strike a death-blow at the freedom of the people.” This resolution was approved unanimously, indicating perhaps that antislavery women perceived a link between the civil rights of slaves and free blacks and those of free women.

25More questions about the propriety of expanding female activism were raised in New York newspapers not long after the convention adjourned. William Stone, a staunch colonizationist and editor of the

New York Commercial Advertiser, published a report of the convention under the headline “Billingsgate Abuse” and dubbed the meeting an “Amazonian farce” attended by “a monstrous

regiment of women” who were “petticoat philanthropists.” Questioning the femininity of those who attended the convention, he referred to them as “female brethren” and accused them of being deluded by “the charming” George Thompson, the British abolitionist who had recently concluded a speaking tour of the northern states. “The spinster has thrown aside her distaff—the blooming beauty her guitar—the matron her darning needle—the sweet novelist her crow-quill,” wrote Stone. He continued to rant: “The young mother has left her baby to nestle alone in the cradle—and the kitchen maid her pots and fryingpans—to discuss the weighty matters of state—to decide upon intricate questions of international polity—and weigh, with avoirdupois exactness, the balance of power.” Stone also ridiculed the convention’s “oratoresses” and the “rich rivers of rhetoric which flowed through the broad aisle.”

26Soon after it adjourned, the convention of antislavery women issued

An Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States, which urged northern women to work against slavery in several ways, especially by petitioning. The

Appeal was drafted by Angelina Grimké before the convention and, according to the convention minutes, a committee of Grimké, Lydia Maria Child, Grace Douglass, and Abby Kelley was appointed to edit the document. The poem that appeared on the title page was written by Sarah Forten, and the section of the

Appeal that discussed race prejudice was based in part on information supplied by Grace Douglass’s daughter, Sarah Mapps Douglass.

27The pamphlet enumerated the ways in which the peculiar institution violated political, moral, and religious principles held dear by all people regardless of sex. Slavery, it stated, robbed “MAN” of his humanity, of his “inalienable right to liberty,” of the fruits of his labor, and of the ability to protect himself. But slaves were not the only victims, it argued, for so, too, were northerners. Slavery outlawed “every Northerner who openly avows our Declaration of Independence,” destroyed northerners’ ability to communicate through the mail, threatened with assassination any congressman who dared speak about it, and trampled “the right of petition when exercised by free men and free women.” To stamp out the institution that had denied slaves access to the Bible, creating “A NATION OF HEATHEN IN OUR VERY MIDST,” the

Appeal urged women to read about slavery and join abolition societies. By gaining information about slavery, it explained, “you will prepare the way for circulation of numerous petitions, both to ecclesiastical and civil authorities of the nation.” The

Appeal urged that “

every woman, of every denomination, whatever may be her color and creed,

ought to sign a petition to Congress for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade in the district of Columbia—slavery in Florida—and the inter-state slave traffic.”

28In the course of calling women to participate in the petition campaign, the

Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States sounded arguments that were much bolder than those employed in the 1836 addresses. Rather than attempting to distance women’s antislavery activism from politics, the

Appeal readily acknowledged political aspects of women’s activities and shirked the notion that women possessed no duties beyond the parlor and the nursery. Asserting that “every citizen should feel an intense interest in the political concerns of the country,” it demanded that women be recognized as citizens. “Are we aliens because we are women? Are we bereft of citizenship because we are the

mothers, wives, and

daughters of a mighty people? Have

women no country—no interest staked in public weal—no liabilities in common peril—no partnership in a nation’s guilt and shame?” Instead of attempting to move slavery into the home, where it would seem proper for woman to attack it, the

Appeal attempted to lay a republican path on which women, whom it characterized as citizens of the republic, could walk a route of expanded political participation.

29The convention’s

Appeal, moreover, went beyond emphasizing the duties incumbent upon women as members of the female sex to stress their responsibilities based “on the broad ground of human rights and human responsibilities.” “All moral beings have essentially the same rights and duties, whether they be male or female,” it proclaimed. Instead of arguing that it was appropriate for woman to petition because she was more moral than man, the

Appeal declared that women should be allowed to petition because they were equal to men and possessed the same rights. In making this demand, the

Appeal moved beyond a critique of male social dominance based on alleged masculine moral inferiority to the claim that men were denying women their natural rights. “The denial of our duty to act is a bold denial of our right to act; and if we have no right to act, then may we well be termed ‘the white slaves of the North’—for, like our brethren in bonds, we must seal our lips in silence and despair.” In this passage the

Appeal deconstructed the attacks leveled against women petitioners by explaining that questioning the propriety of female petitioning (“denial of our duty to act”) in effect entailed a denial of women’s constitutional right to freedom of speech. Because their right of petition had been abrogated and they were denied the right to vote, the

Appeal contended, women were no better off than slaves when it came to the exercise of political rights. Although this argument obscured the significant material differences between the lives of slaves and those of the predominantly white, middle-class antislavery women, by articulating the denial of women’s natural rights and placing it in perspective, the

Appeal made a major contribution to nineteenth-century feminist thought.

30

The convention’s

Appeal directed women to petition because slavery violated the principles of Christianity and natural rights, but it made no mention of the issue of Texas annexation. Yet during 1837 abolitionists had elevated the Texas question, along with the gag rule controversy, to the forefront of their case against slavery. Abolitionists devoted their attention to the issue of Texas after Benjamin Lundy published a series of essays and a widely circulated pamphlet titled

The War in Texas, which argued that the drive for Texan independence was part of the ongoing conspiracy to expand the slave power. Lundy demonstrated that the Texans were rebelling not because they had been oppressed by the Mexican government but because they wanted to break away from Mexico, whose constitution prohibited slavery. Not only would an independent Texas perpetuate slavery in the West, Lundy argued, but it would likely spawn six to eight new slave states. This shift in the balance of power between the sections, according to Lundy, threatened to dissolve the Union. Lundy’s interpretation of the events in Texas and his predictions about the future of the Union were accepted by Adams, who encouraged Lundy to circulate his arguments as widely as possible to rouse public sentiment against annexing Texas.

31Because none of the pamphlets published by the women’s convention discussed the important issue of Texas annexation, immediately after the convention the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society issued

An Address to the Women of New England. It was signed by Parker, who was president of both the society and the convention. In addition to being printed in the

Liberator, the

Address was published on letter sheets to which were attached petitions opposing the annexation of Texas. Like Lundy’s pamphlet, the

Address to the Women of New England claimed that if slaveholders succeeded in their plot to annex Texas, the freedom and the very lives of northerners would be endangered. But why, asked the Boston entreaty, should women care about Texas? Because, it answered, if Texas were annexed to the Union, “our husbands and our sons should be drafted from our household-floors, to encounter the storm of fire and blood that will sweep along the south-western border.” The Union would be dissolved, “brother should battle against brother and friend against friend,” and the slaves would take advantage of the crisis and “rise to the shedding of blood on every southern threshold!” The Boston women warned that “the unutterable destruction that sooner or later awaits our country, unless slavery is abolished, is as certain as that God judges and punishes nations, in this world, according to evil deeds.” In light of the destruction sure to follow from annexation of Texas, women were asked to petition Congress against this policy. “Let every woman into whose hands this page falls, INSTANTLY (for the work must be done before the extra September session) prepare four rolls of paper, and attach one to each of the annexed forms of petition; and with pen and ink-horn in hand, and armed with affectionate but unconquerable determination, go from door to door ‘among her own people,’ that every one of them may have an opportunity of affixing her name to these four memorials.”

32Like the

Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States, which more directly asserted that women possessed the right of petition than previous female antislavery publications had, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society

Address directed women to take action on a specific issue that was undoubtedly political. Women must petition against annexation, the Boston

Address explained, so northern representatives would know the true wishes of their constituents. More explicitly than ever before, this address described female petitioning as advising representatives on a political matter, rather than as “praying” to the “guardians of our nation” to do what was right. Furthermore, the

Address insisted that women were not just the “mothers, wives, daughters and sisters” of male constituents but that women themselves were, in fact, the constituents of northern congressmen—that they were full citizens. “Remember that the

representation of our country is based on the numbers of population, irrespective of sex,” the Boston women prompted. Here was a novel argument for women’s rights that harkened back to the rhetoric of the American Revolution, to abolitionist critiques of the three-fifths clause, and to Adams’s defense of the right of slaves to petition. When calculating population in order to determine how many representatives each congressional district would be awarded, the

Address observed, a female was counted as a full person. If the Constitution acknowledged women as worthy of being counted to determine representation in Congress, the

Address claimed, then surely they possessed the right to make their opinions known to their representatives.

33

Appealing to women to continue petitioning was but one of the means of persuasion set in motion at the 1837 convention. Another important task accomplished as a result of the meeting was the introduction of new petition forms. In the first phase of women’s antislavery petitioning from 1831 to 1836, local antislavery societies had relied on long, printed petition forms that ran about a page in length and emphasized that slavery was sinful. But when male and female abolitionists implemented strategies discussed at the 1837 conventions, they cast aside the petition forms that they had been using for several years. During this second major phase of women’s antislavery petitioning, no longer were the lengthy forms with their protracted explications of the evils of slavery, their sentimental statements about woman’s duty to petition, and their detailed descriptions of slave auctions within sight of the nation’s Capitol able to meet the demands of the situation in Congress. Passage of the gag rule necessitated a change in strategy. After no small amount of contemplation, petition campaign coordinators realized that the gag did not prevent Adams and his cohorts in the House from stating the title of a petition. To get their message across before cries of “Order!” rang out from all sides, abolitionists did away with the long petitions and composed short forms that in the same breath announced the title and the prayer of the petition.

34The switch to short forms not only affected presentation of the petitions in Congress but also marked a major change in the way women went about petitioning. More and more women signed the same forms as men, though they kept their names in separate columns, and short petitions allowed no room for veiling the political requests of women or for elaborate discussions of the propriety of female petitioning. The language of humility, ever present in women’s petitions submitted during the early 1830s, began to disappear. Gone was the elaborate type; gone was the palaverous prose. The typical short form cut directly to the chase:

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:

The undersigned, _ of _ in the State of _ Respectfully pray your honorable body immediately to abolish SLAVERY and the SLAVE TRADE in the DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA.

35

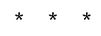

Lucretia Mott, who helped organize Philadelphia Quaker women in 1831 to send the first collective female antislavery petition to Congress, played a leading role in the 1837 female antislavery convention. (Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society)

Maria Weston Chapman, a leader in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, wrote petition forms and public addresses and led implementation of a systematic plan of petitioning. (Reprinted with permission of the Boston Public Library/Rare Books Department—Courtesy of the Trustees)

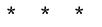

In 1837 abolitionists switched to short forms, which allowed John Quincy Adams and other sympathetic representatives to shout out the statement of the petition before being silenced by calls for order. Short form petitions were often printed in reform newspapers, from which they were cut out and pasted on sheets of paper to be circulated for signatures.

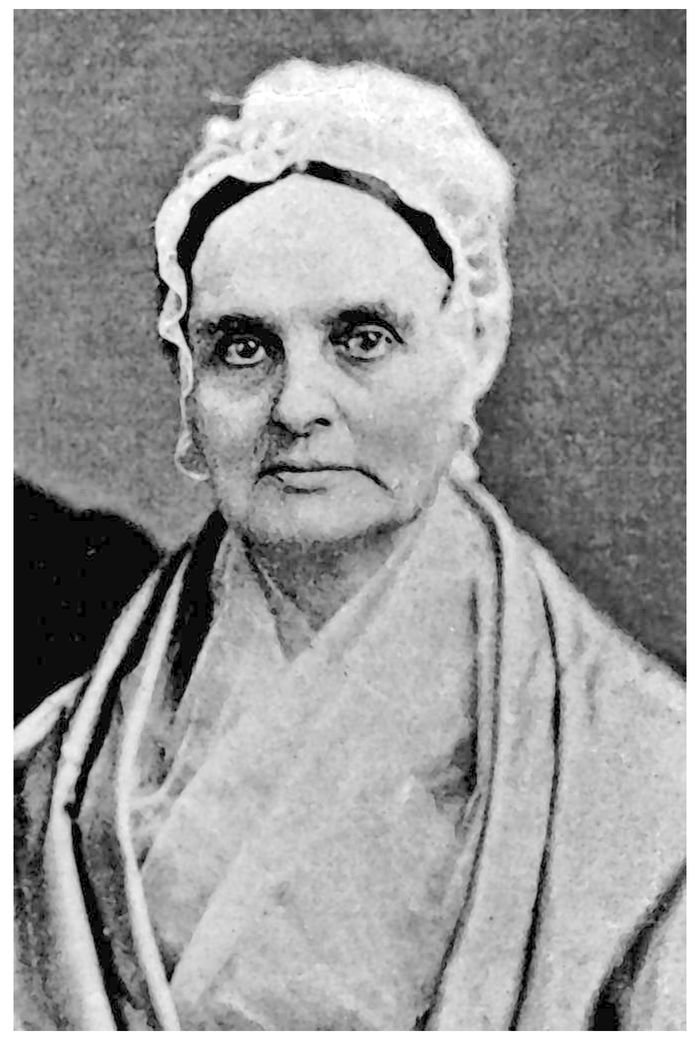

Sarah M. Grimké and Angelina E. Grimké joined the women of Brookline, Massachusetts, in signing this short petition protesting passage of the gag rule. The sisters’ 1837 New England lecture tour won many signatures to petitions like this one. (Courtesy of the National Archives)

Plain and simple, most of the short petitions rarely exceeded five lines. Some were longer, usually about ten lines, but rarely did they reach the length of petitions circulated in previous years.

Not only could antislavery congressmen state the short form request quickly, but up to twelve different requests could easily be printed on a single handbill. Canvassers—women and men alike—were supplied with forms and instructions printed in New York by the national office of the AASS and reproduced in abolitionist periodicals. Immediately after the May convention the AASS published a large edition of a petitioning circular, which provided eleven petition forms. Six of the forms were addressed to Congress; five, to state legislatures. The first petition related to slavery in the District of Columbia, an issue that “is now a test question. As it shall be decided, so will be the fate of liberty in this nation.” The second petition, which involved slavery in the territories, was described in much the same manner as the first. For the third petition, regarding the interstate slave trade, the circular provided petitioners with an argument: “Congress has declared the traffic in men on the high seas and on the coast of Africa,

piracy. Is it less practical in

America?” The fourth petition addressed the admission of Florida to the Union as a slave state. On this issue the circular urged adherents to “be ready in season, so that we may not be taken by surprise, as in the case of Arkansas.”

36The last two petition forms addressed the most important issue for abolitionists in 1837: the admission of Texas. The petition drive to halt Texas annexation not only laid the groundwork for the political organization of abolitionists in general, but it pushed women closer to overt political activity. By signing petitions for repeal of the gag rule and against annexation of Texas, women joined men in voicing their opinions to Congress on issues of national policy. Moreover, the short petition forms did not provide space for women to divorce their activism from politics and to insist that their goals were purely benevolent. From 1837 on, women expressed their requests in petitions by using the same language and by assuming the same stance as male petitioners. Prominent black abolitionist women Margaretta and Sarah Forten and Sarah and Grace Douglass signed a petition that assumed this new bold attitude. Lucretia Mott, Mary Grew, and 222 other women of Philadelphia joined the others in affixing their names to a petition that read,

To the House of Representatives of the United States:

The memorial of the subscribers, citizens of Philadelphia, respectfully represents: That we have perceived, with deep regret, that a resolution has passed your distinguished body, virtually denying to all the inhabitants of the free States the right of petition, and consequently abridging the freedom of speech. As such an act is obviously contrary to the constitution of our country, we do respectfully protest against it, and ask for its immediate reconsideration and repeal.

This petition is noteworthy both for what it said and for what it did not say. It said that the female signers were willing to affix their names to a petition that claimed to emanate from “citizens.” In previous years the vast majority of women had scratched out the word “citizens” on printed petitions and replaced it with “inhabitants” or “residents.” By using the appellation “citizens,” women claimed for themselves a new status in the young republic. Unlike most female petitions sent between 1831 and 1836, this one did not describe women as approaching their representatives deferentially, nor did it insist that women were motivated by a unique female morality.

37These changes came about partly because of the lack of space on standardized short form petitions and also because of changes in attitudes about women petitioning. When given the opportunity for elaboration, women expressed in their petitions a new, bolder stance. Nowhere is this more evident than in the petition of women against the admission of Texas to the Union circulated among the women of Ohio. Even though it was much shorter than the Fathers and Rulers and other long petition forms, this entreaty was about three times as long as the short forms and offered ample space for the petitioners to develop a rationale for approaching their representatives and for explaining their objections to annexation. Whereas in 1836 the women of Ohio had addressed their legislators as the “Fathers and Rulers of Our Country,” in 1837-38 their display of deference had vanished, and they addressed their petition “To the honorable, the Senate and House of representatives of the United States.” Absent also were characterizations of the humility of female petitioners. No longer did they “pray” with “sympathies” they were “constrained to feel as wives, mothers, and daughters.” Instead they said in the first line of the petition, “Women have one inalienable mode of representing what might be for their own interests or for the interests of mankind, namely, supplication.” Unlike the Fathers and Rulers form, which began by stating that the signers would not dare to “obtrude” on the business of Congress unless the issue was pressing, in the antiannexation petition the women of Ohio opened by forthrightly stating that petitioning was women’s “inalienable mode” of communicating their sentiments to their representatives. No longer did they describe their petitioning as motivated by some outside force. No longer did they identify themselves as adjuncts of male citizens.

38Furthermore, when stating grievances against the policy of annexation, the women’s antiannexation petition did not mention Christianity or the suffering female slave. Unlike the sentimental expressions of the evils of slavery common in the long form petitions, the later Ohio form was almost legalistic. It stated, “One prominent reason amongst others, why we deprecate its [Texas’s] annexation, is, its constitution expressly sanctions slavery, and encourages the slave trade between [Texas] and the United States. When most governments in the civilized world, where slavery has been instituted, are taking measures for its abrogation, we humbly pray that our Republican Legislators will not be found legislating for its extension, and augmenting the horrors of its traffic.” The petition grounded rejection of the Texas annexation on constitutional law and republicanism rather than on benevolence or female duty. Indeed, the word “duty” was used only once in the petition, when the signers stated that they considered it their “imperative duty” to entreat Congress to reject the proposal for annexing Texas. But even here the duty was not that of wives, mothers, sisters, or even Christians, but of republican citizens.

39In addition to altering the petitions strategically, coordinators of the campaign recognized that volunteers needed specific directions on how to circulate and submit petitions. To this end they printed circulars in which a number of short petitions were accompanied by explicit instructions directing volunteers when to begin petitioning, how to petition, and when the completed petitions were to be submitted. The volunteers were encouraged to start gathering signatures immediately and not to confine their efforts to abolitionists. “All who hate slavery, and love the cause of mercy, and would preserve our free institutions, should put their names to them, without regard to their view of abolitionism. It should be a movement of THE PEOPLE.” This consideration, the circular stated, should be “emphatically urged.” Volunteers were instructed to circulate all the petition forms at the same time because this method would be most economical and because individuals willing to sign one petition would be likely to sign them all. Yet the petitions were to be separated in case those called on were willing to sign some but not others. The circular also asked readers to make sure each town in the county had received blank petition forms. If not, the annexed petitions should be copied and conveyed to a “suitable person” in the town with a request that they be returned to the person who copied them.

40The last section of the circular was devoted to details of handling the petitions and was titled “Small, but Necessary Matters.” The person who received the circular and the attached blank forms was asked first to cut the petitions apart and to paste each one at the top of a half-sheet of paper. Next they were to fill in the first blank in the body of the petition, which described the persons who were submitting it with the words “citizens,” “inhabitants,” “legal voters,” “women,” or whatever the case may be. In the second blank they were to write, if the memorial was directed at a state legislature, the name of the city or town in which the petition originated; if the petition was aimed at Congress, they were to write the city or town and the county. Volunteers were instructed to make sure that signatures were written on only one side of the paper and to paste on more sheets if needed. The circular emphasized that everyone should write his or her own name: “Names should not be

copied on—it might lead to a suspicion that they were forged.”

41The last instructions detailed how to submit the completed petitions to Congress or the state legislature. It was important, the circular emphasized, that the names on each petition be counted and that the number be written clearly at the top before it was forwarded. The completed petitions were to be sent by each town with a letter to a member of Congress or to the state legislature, though in some cases arrangements could be made to paste together all the petitions from one county to send in a large roll. Volunteers were also told that petitions of any size as well as letters under two ounces could be sent postage free. Even better, the circular advised, signed petitions could be handed to congressmen before they departed for Washington. All petitions relating to Texas were to be submitted at the beginning of the special congressional session starting in September 1837, while the other memorials were to be sent at the beginning of the regular session in December.

42In addition to circulars, personal letters were employed to send blank petition forms to women who could be trusted to put them into circulation in their towns. Letters enclosing blank petitions were sometimes sent to women whom organizers knew through family or other social networks. At other times organizers sent letters and forms to women with whom they were completely unacquainted. On July 10, 1837, just two months after the convention, a member of the Philadelphia Female AntiSlavery Society composed a letter to a woman in Bedford County, Pennsylvania, on the back of a blank petition. “Although an entire stranger,” prefaced the writer, “I take the liberty of requesting you to hand this to any lady who is willing prove her christian principles (which enjoin love to all), her patriotism, and her sympathy, for the oppressed by exerting herself to circulate these petitions.” The correspondent explained how the society had taken charge of petitioning in each county and asked the recipient to reply promptly, stating whether or not she would circulate the petition. “Deeply reflect on it before you refuse to act” on behalf of the slave, the writer urged, “for we are commanded not only to remember them that are in bonds bound with them, but to do unto others as we would they should do unto us.” Like other personal letters aimed at encouraging petitioning, this missive repeated female antislavery rhetoric from petitions, addresses, and other abolition literature. Apparently its entreaties succeeded, for the petition was circulated throughout Bedford County and sent to Congress.

43Personal letters were also used to gather lists of women to whom petitions could be sent and to instruct volunteers how to circulate petitions. Henrietta Sargent, a member of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, agreed to distribute blank forms in Worcester County, but she ran into difficulty because she knew not “a single individual of fidelity to address” with the exception of Abby Kelley. So Sargent wrote a letter to Kelley asking, “Will you have the goodness to furnish me with such names as you can recommend, with the town where each person resides, and help me by inquiry to a full list.” In like manner Mary G. Chapman addressed a letter to John O. Burleigh and enclosed a blank form asking him to have the “goodness to place this memorial in the hand of a friend who will exert herself to obtain signatures to its petitions from the women of Oxford.” She reminded Burleigh that after signatures were obtained, the volunteer should count the names and put the figures at the top of the petition before sending it with a letter to the representative of her district or town.

44As effective as personal letters were in persuading individual women to circulate petitions, abolitionists knew that creating a massive persuasive campaign around the right of petition required the power of the antislavery press. Abolition newspapers provided male and female petition coordinators the opportunity to report on the progress of signature gathering, to offer tips, and to remind volunteers of deadlines. On July 14, for example, Amos A. Phelps offered a few suggestions in response to inquiries he had received regarding the simultaneous circulation of memorials to Congress and to state legislatures. He described two ways to go about the task. Volunteers could either circulate both state and national petitions simultaneously or circulate them separately. For those employing the first method, Phelps recommended trying to get each individual to sign every petition. “If, however, the individual should be unwilling to write his name so many times, precedence should be given to those petitions of greatest importance—those for instance which refer to Texas and the abolition of slavery and the slave-trade in the District of Columbia.” Volunteers were instructed that if the person being solicited refused to sign these petitions, they should have others ready. “Some, for example, will sign a memorial for the abolition of the inter-state trade, who will not sign one for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia.” If volunteers chose to circulate the petitions separately, Phelps asked that memorials designed for Congress be circulated first and “those for the

State Legislature . . . carefully preserved, for circulation at another time.”

45The abolitionist press aided in the petitioning effort by printing further inducements, instructions, and reminders. In mid-August, for example, the

Emancipator ran an article headlined “How to Do It,” which included a form of petition against the annexation of Texas. The reader was urged to put the petition into circulation and to “get every man and woman in your neighborhood to sign it.” Volunteers were to attach long rolls to each petition and to take care that men and women signed in separate columns. The number of each class of signers was to be counted and marked on the back, and the petition was to be sent to Washington, D.C., by September 1. The next week the newspaper suggested that “sometimes it is advantageous to petition Congress in classes. For instance, ministers of the gospel in a certain district; lawyers in a county, the merchants of the village, and so on.” In September volunteers were further encouraged by a letter from a member of the legislature of New York who proclaimed the new system to be a success. “I am glad a system has been fixed upon for petitioning the state and national legislatures at the approaching sessions,” he said. “Hitherto, what has been done has been at haphazard, especially in this state.” The legislator reported that a man in his city who was calling on every family with ten different petitions he received from the antislavery office was meeting with great success. “

Very few refuse to sign.”

46Constant reminders in abolition newspapers and personal letters aimed at increasing the efficiency of signature-gathering efforts also strengthened connections among women. These reminders accomplished on a broader scale what women had managed to do at the first female antislavery convention. The convention fulfilled a need, stated a report of the Dorcester Female Anti-Slavery Society, for “woman [to] consult with woman” even though participants became subjects of public “ridicule and contempt.” The gathering, explained the Dorcester society, enabled women to join men in bearing a “united, public testimony against the brutalizing system of slavery.” The convention inspired Abby Kelley, who after meeting with other abolition women became “even more energetic in her activities.”

47Part of Kelley’s enthusiasm may have come from the fact that the convention provided a crucial setting for women to express their frustration over limits on female activism and to devise a rationale to justify expansion of their role. Mary G. Chapman’s letter to the convention illustrated the centrality of this issue: “The present state of the world demands of woman the awakening and vigorous exercise of the power which womanhood has allowed to slumber for ages,” wrote Chapman. “She has been oppressed, kept in ignorance, degraded—not in vain if she has thereby learned active sympathy for the enslaved—not in vain, if her sufferings contribute to her salvation.” Indeed, as Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote years later, the 1837 meeting and subsequent female antislavery conventions were “the initiative steps to organized public action and the Woman Suffrage Movement

per se.”

48

Historians have recognized that passage of the first gag rule proved a god-send to the abolition movement by wedding the unpopular cause with the sacred right of petition. Yet approval of Pinckney’s resolution also had a profound effect on the rhetoric of female abolitionists, who began to articulate natural rights arguments to justify their petitioning and to claim that they were citizens. Passage of a second gag rule, moreover, created an urgency that led female antislavery leaders to call an unprecedented convention to organize a systematic plan of petitioning and to alter the petition forms. In the process women asserted an increasingly bold political stance grounded in their standing as republican citizens rather than in their moral and religious duties. So drastically did women expand their petitioning to influence public opinion about slavery that jealous conservators of traditional female roles soon attempted to put women back in their place. Yet as we shall see, traditionalists succeeded only in forcing women to develop even bolder defenses of their right to petition and to participate in political decision making.