3

Educating the Good Sister

[A] prime attraction of convents was a way of life which gave women, who would otherwise have had no such possibilities, an access to effect change, a prominent and active role-in short, a vocation in the world. Sisterhood was seen as a great undertaking in the service of an active and enthusiastic faith.

-A Passion for Friends

Gender and Religious Identity

For nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Catholic women, having a “vocation” or a calling to religious life meant leaving their families, renouncing their former lives, and embracing a new life of religious identity and consciousness. The adolescents and young women who responded to this “call from God” entered into a female world of ritual, commitment, and service. They were asked to become “dead to the world,” to vow to live a life of poverty, chastity, and obedience. The community became the mother, the sister, and the teacher who fed, clothed, supported, and educated them, preparing them for a physical existence of prayer and service that was to be lived in preparation for the spiritual life to come. To become a CSJ the candidates were required to “practice a profound humility,... endeavor to act from the supernatural motives of faith, of hope, and of divine love,” and “devote themselves to the service of their neighbor.”

1 For active or “apostolic” communities like the CSJS, women joined the order to work actively in the world in education, nursing, or social service, combining religious fervor and ideals with public service.

2 This convent education and culture trained thousands of American sisters who, in turn, spent a lifetime engaged in caregiving activities that shaped the educational and cultural lives of American Catholics in every region of the nation.

Contrary to nineteenth-century Protestant rhetoric describing kidnapped and coerced nuns, American women made their own decisions to enter religious life, and many decided early about their future vocation. Although families varied in their support of daughters who made this choice, some young women “knew” at an early age that this was their calling, while others described a significant person or event that powerfully motivated their decision. Family considerations and connections played an important role for some. For the Littenecker sisters of St. Louis and the O‘Gorman sisters of Oswego, New York, joining the CSJS became a family tradition when three Littenecker sisters entered in an eight-year span beginning in 1853 and the five O’Gorman sisters entered the CSJS between 1862 and 1890.

3 Sister Grace Aurelia Flanagan first experienced convent life in the 1890s, when at age five she began visiting her CSJ aunt in a Toronto convent. In 1917, Sister Guadalupe Apodaca entered the convent to fulfill her “mother’s vocation” since her mother as a young woman had been unable to join a religious community.

4For other CSJS their decision to enter religious life came from other sources. Some sisters told of an almost mystical experience occurring during mass or at the death of a loved one that influenced their choice. In the late 1890s Sister Charitina Flynn was a student at St. Joseph’s Academy in St. Louis when she had a life-altering experience. During chapel one day she distinctly heard a voice say: “I want you to be a Sister of St. Joseph.” For weeks she could think of nothing else and finally decided to enter the community, but her widowed mother was adamantly opposed to her daughter’s decision. One year later she left her mother’s home to teach in another town. Later she visited her mother for the last time and left for St. Louis to enter the community without her mother’s permission.

5 Her mother’s negative reaction demonstrates the seriousness and permanence that such a decision meant for the candidate and the family left behind.

Besides family considerations and spiritual experiences, interactions with sisters who taught them in school influenced many young women to become CSJS. They often saw the life of sisters as an alternative to more traditional gender expectations and family life. Indianapolis-born Kitty O’Brien became Sister Anselm when life at home and at a university did not appeal to her: “In the fall [1914], I enrolled at Butler University, but regardless of how ardently everyone tried to build up my enthusiasm, I hated it. I felt that I didn’t belong. As soon as classes were dismissed I’d run to Holy Angels School and talk with Sister Ethna. There I could feel peace. I was comfortable with her and the sisters. Even at home, no matter how desperately I tried to be a part of all that was happening, my thoughts were somewhere else,”

6

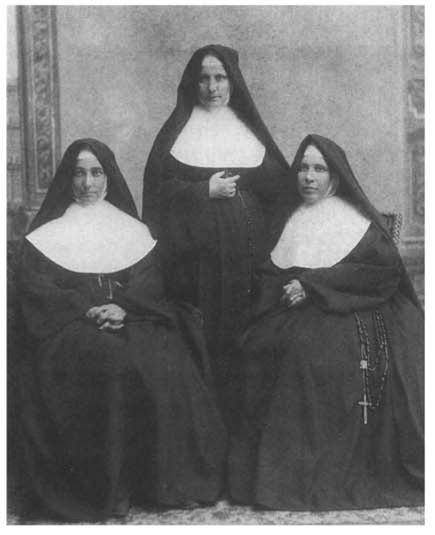

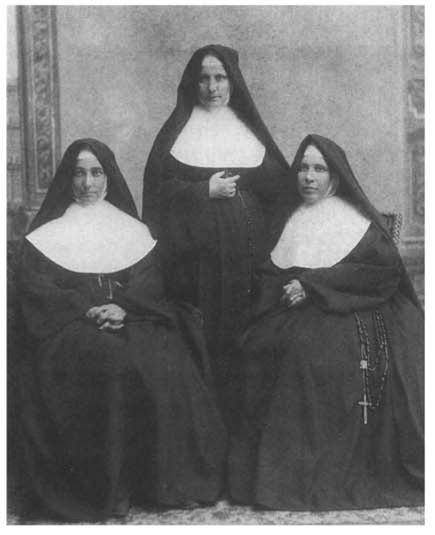

Three members of the Ireland family (left to right): Sister St. John Ireland, Sister Celestine Howard, and Sister Seraphine Ireland, St. Paul, Minnesota. 1880s (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Archives, St. Paul province)

Family life, spiritual experiences, and the presence of alternative female role models provided motivations for many young women of all religious traditions to achieve or pursue an endeavor that at times might have been at odds with more traditional societal or family expectations. In fact, one scholar has argued that by devoting their lives to God, women received “cultural and theological legitimacy in making decisions and expanding work in the public sphere for which they would otherwise have no claim against familial pressure.”

7 If one imposes contemporary values and attitudes on these motivations, one may miss the point about the significance of this decision. Women have historically struggled to find a place in religious traditions that have elevated men to “divine” status as definers and gatekeepers of religious rituals, symbols, and authority. Women have fought for autonomy and meaning against sacrosanct prescriptions that have attempted to control female behavior in both private and public settings. This seems to have been particularly true when women attempted to claim sacred space or agency in an effort to live out their religious ideals.

8 Between 1836 and 1920 (and beyond), though race, class, or ethnicity may have influenced their choice, women who chose

not to become traditional wives and mothers and who renounced family interests for a woman-only setting without attachment or subordination to fathers, brothers, or husbands made a singular choice. For Catholic women, an alternative to wife-and motherhood was the convent.

Whatever the defining moment in a young woman’s life, most nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century American Catholics, even parents who opposed their daughters’ entry, viewed religious life as a “higher” life, which, in effect, provided women with an appropriate alternative to traditional gender expectations. By seeking a higher spiritual existence, girls and women had permission to forgo marriage and focus on a larger life purpose and meaning. Equally important, a religious vocation allowed creative, ambitious, and bright women from working-class or rural backgrounds to obtain education and opportunities that their families could not otherwise provide.

9 Mary Ewens has argued that nineteenth-century nuns “enjoyed opportunities open to few other women of their time: involvement in meaningful work, access to administrative positions, freedom from the responsibilities of marriage and motherhood, opportunities to live in sisterhood, and egalitarian friendships. Perhaps it was this freedom from the restrictive roles usually ascribed to women that enabled them to exert such a powerful influence on the American Church.”

10In the CSJ community women of all ages and from a variety of urban, rural, ethnic, and class backgrounds came together seeking the new identity and culture provided by religious life. All CSJ constitutions had specific requirements for entry into the community. Each candidate had to complete three levels or stages of formation—as postulant, novice, and professed sister. Although candidates had to be between the ages of sixteen and thirty-five to enter the CSJ novitiate and receive the habit, young women could become candidates or postulants as young as fifteen. The candidates had to be born into a legal marriage and have proof of a Catholic baptism. They should be “virtuous” and “enjoy good health.” CSJ postulants were to be free of debt and “old enough to understand well the nature of the state they embrace.” By 1884, the required dowry was fixed at $100.

11 The CSJ Profession Book provides intriguing data about the women who joined the order and reveals that at times the prescriptive literature was ignored.

From 1836 to 1920, 3,335 women between the ages of fifteen and fifty-five entered and professed vows as CSJS. Contrary to popular perceptions about religious orders “robbing the cradle” and attracting young, gullible girls to the convent, these entrants averaged 22.0 years of age. This statistic varied little in the eight decades analyzed, with entrants in the 1870s recording the youngest mean age at 20.7 and candidates in the 1910s the oldest mean age at 22.7. Similar to marriage statistics for American women, a significant number of women were between eighteen and twenty-two when they entered the CSJ community, but the majority (57 percent) were between twenty and twenty-nine years of age. As was true of marriage, entering the convent was a lifelong and life-altering choice usually made by young adult women.

12 Foreign-born women who entered the CSJ community were slightly older than American-born women, which may reflect a class distinction prevalent in European convents. Some American communities, unlike European convents, often waived or reduced the required dowry, and sometimes superiors accepted material substitutes in lieu of cash. Foreign-born women who could not afford to join a religious order in Europe found that immigration to the United States eliminated financial obstacles to entering.

13The immigrant and working-class status of many American Catholics sometimes made payment of dowry money impossible. Like other American communities, the CSJS ignored this European custom when necessary in order to gain postulants. Concerned about this obvious violation of their newly approved constitution, French-born Mother St. John Facemaz wrote Bishop Kenrick in 1868 about the need to accept postulants without a dowry. Like many other American bishops he understood the problem and told her it would be “undesirable” to discuss the issue with Rome but advised her that the dowry should continue “to be determined by circumstance.”

14 Postulant records from the CSJ provinces document that the dowry “problem” occurred in all regions of the country. Some candidates paid one, five, ten, or twenty dollars, but many paid nothing at all. For example, to compensate for their lack of dowry money, the Lien-gang family of St. Louis “brought over a piano” when their daughter became a CSJ postulant in 1876, while another candidate brought the family sewing machine as “partial dowry.” Although some families could afford the dowry, with a few paying thousands of dollars, the CSJ records show that the problem continued for some candidates through 1920 and beyond.

15During the earliest years of the community, the CSJ formation process probably varied according to circumstance and need; by the 1870s the method used to shape a new candidate was extremely consistent, varying only with the style and temperament of the postulant and novice mistresses. The three- to six-month postulancy allowed the candidates to observe and interact with the novices and professed sisters at mass, meals, holidays, feast days, and in some work settings.

16 Nineteenth-century postulants retained their secular clothing and were expected to dress “modestly.” In the CSJ Customs Book of 1868, the community provided prospects with a list of clothing items to be brought with them and used during the postulancy:

bed and bedding

black woolen shawl

1 dz. chemises

½ dz. table napkins

4 nightgowns

white dress

carpet bag

2 green veils

½ dz. towels

½ dz. night caps

4 pr. shoes

overshoes

black dress w/cape

1 bonnet, extra dresses

24 white handkerchiefs

½ dz. woolen/cotton hose

3 white muslin shirts

flannel underwear.

17This was basically a “wish list,” since some candidates came with the clothes on their backs and very little else.

After completion of the postulancy, the candidate received the habit (except the crucifix) and her new religious name in a special ceremony of “reception” into the community. The next level or stage of formation, the novitiate, was a highly structured educational experience that assimilated the novices into the community, educated them spiritually, psychologically, and academically, and provided them with a two-year trial period before they took their first vows. Directed by a mistress of novices, the young women were more integrated than postulants into community life; they began to interact with a larger number of professed sisters; and their clothing, behavior, schedules, and activities more closely paralleled professed sisters’, although novices performed the major share of domestic duties required by the community. During this apprenticeship period they labored in the kitchen, laundry, sewing room, and throughout the community household, while continuing to receive education through spiritual exercises and classes. The first year of the novitiate was filled with lectures and reading, the study of church history, congregational history, and the three vows, as well as prayer and religious rituals. Gradually the novices were also taught appropriate “religious” behavior.

Young postulant dressed as a bride before receiving the habit of the Sisters of St. Joseph, 1880s (Courtesy of the Arizona Historical Society/Tucson, B#4985)

Analysis of an early novitiate manual provides an intriguing look at the formation process of CSJ novices. The first section focuses on “General Regulations,” which involve the novice’s appropriate behavior and religious practices in dressing, washing, eating, and interacting with peers and professed sisters. The second section describes “Things to be Observed During Meditation,” where again the focus is on specific practices or behaviors for prayer and meditative activities. The third section, “The Essence or Spirit of the Religious Life,” is perhaps the most compelling because it goes beyond behavioral practices and gives the novices a description of the expected and requisite attitudes necessary for a religious vocation. The novice was told that “she cannot expect to be perfect” but should have the “desire of becoming perfect.” She had to be “willing to make sacrifices,” renounce “gratifications and luxuries of the world,” and be willing to participate in “unending labor and toil,” being content “with plain and poor accommodations, food, and clothing.” Finally, she was told that it was not enough to “possess virtue”; she must “[conform) herself to the spirit of her Order.” Clearly the “old” life must be left behind; the “new” life and its challenges must be understood and embraced.

18In the second year of the novitiate, the young women were expected to achieve greater proficiency in behaving like religious women (nuns) and were also given a more advanced formal curriculum to prepare them for their future assignments, which most often meant teaching. Sister Winifred Hogan, who entered the St. Paul novitiate in 1879, wrote, “The Novitiate really was the ‘House of Study.’ We had our regular recitation periods from nine to eleven-thirty in the morning and from two-thirty to four in the afternoon. The curriculum of work consisted of: Christian Doctrine (Perry’s Catechism), Reading, Rhetoric, Grammar, Mathematics, Astronomy, Philosophy (Physics without laboratory work), Elocution, Music, Writing, and Drawing.” In addition to daily classes the novices took turns reading inspirational or educational material during chapel or meals in the “refectory” (dining room). Sister Winifred called this “an ordeal” because “we could not stand in some obscure corner ... but we had [to] sit on a high rostrum in the most conspicuous place in the room where the professed members could see and hear us to a greater advantage.” Although the listeners were expected to observe silence, this public activity often caused anxiety for the reader and amusement for the audience. One day when she should have read “Examine yourselves and see,” Sister Winifred heard herself proclaim loudly, “Examine your

sleeves and see,” much to her embarrassment.

19The six-month postulancy and two-year novitiate provided an intensive and powerful life-altering experience for these young women. Cut off from family and friends and enclosed in a self-contained, highly structured environment, they bonded with each other, absorbing community ideals as they worked toward professing vows. The powerful combination of religious ritual, structure, dress, and direct spiritual education molded, shaped, and focused their efforts to fit in and become a part of the larger professed community. This shared experience built an esprit de corps among the novices, although youthful idealism and frivolity could not always be tempered.

As postulants and novices in 1915, Sisters Anselm O’Brien and Cyril Lynch had a common bond: “talent for laughing at almost anything and saying the wrong thing at the wrong time.” Periods of “strict silence” were particularly difficult, and Sister Anselm related their dilemma:

Being quite inventive and desperate, it took no time at all until we discovered our own “talking room,” the canning cellar. This part of the basement was called the “Catacombs,” aptly named, I might add with its dark stone walls and its dampness that chilled your very bones. But [we] weren’t motivated by the same fervor as the early Christians, rather it was a fervor for folly as that was the only place where we could really laugh.... Unfortunately there were times our laughing drowned out the oncoming footsteps. Often we found ourselves having to ask for a penance for breaking silence.

20In reminiscing about her novitiate days, one sister described how her young imagination got the best of her. While caring for one of the elderly nuns, she took ritual practice a little too far. “One night I put candles around Sister Holy Cross’ bed and pretended she was dead. The Superior didn’t like it. She asked who did it and I said that I did. I said I wanted to give her a bath, and she said it was no way to give a Sister a bath to pretend she was dead.”

21 Sometimes the older professed sisters could not protect young novices from “worldly temptations.” A superior in the Troy province who endeavored to shield Sister Cecilia Marie Hurley, her young novice, from outside influences normally prohibited her from attending parish activities; on one occasion, however, she decided to take her to the parish play since it was a musical and deemed “safe.” Sister Cecelia wrote, “However, there were a few dances, which of course were popular at the time, in the show. Mother was not familiar with them, especially the Charleston. She was afraid I was scandalized. I assured her to the contrary.”

22Since temptations from the outside world and its influence were minimized if not eliminated, the novices learned to remake themselves and their ideals, assimilating the larger and “higher” aims of religious life. One of the highest compliments a nun could receive was to be called a “Living Rule,” which meant that she embodied “The Rule” (constitution), the important document that articulated the ideals and goals of the community and its founders. To form each member into a “Living Rule” was the goal of convent formation, and every aspect of training and environment supported this end. This physical, psychological, and social regime was intended to give candidates the discipline and character to withstand potentially primitive living conditions, loneliness and isolation, and at times grinding poverty and emotional disappointment. Certainly convent training facilitated the group cohesiveness and loyalty required to work for the benefit of others, to build institutions with limited financial resources, and to confront the difficult work necessary to support and ultimately shape American Catholic culture.

A highly structured, educational experience, the novitiate provided a powerful rite of passage for young girls. Anthropologist Victor Turner, utilizing both the Benedictine and Franciscan orders as models for defining and analyzing community process and formation, discusses the stages involved in rites of passage. Incorporating Arnold Van Gennep’s work, Turner defines the first stage as the “separation period,” where the individual is symbolically detached from her original group; the second stage is “liminality,” where the individual experiences a sense of disorientation while she is “in between” groups; and finally, the third stage, called “aggregation,” the point at which the society attempts to integrate the liminal person into the new role. Formal and controlled ritual trains the person to accept her new roles and responsibilities. In the convent the desired outcome of the rite of passage was described as “being dead to the world.” Turner describes the transition in similar terms, as a process of “death and rebirth” with the individual “fashioned anew.” He states that neophytes in many rites of passage dress alike and characteristically are submissive and silent and “have to submit to an authority that is nothing less than that of the total community.”

23 The postulant and novitiate periods create these stages of passage and mold the women into their new identity and community as “professed” sisters.

Not everyone who entered the CSJ community between 1836 and 1920 stayed throughout the postulant and novitiate stages to profess vows. Postulant and novitiate records show that sometimes the separation was the young woman’s idea and other times the CSJS’. Some entries state that a candidate left because she was “lonely,” “homesick,” “dissatisfied,” or had a “family obstacle.” In 1890, twenty-year-old Eva Pherson, of Newport, Kentucky, “went home of her own accord. Cause: loneliness, discontented.” Other comments reflect the community’s dissatisfaction with the candidate. Illness or a weakened physical condition almost always meant dismissal. The rigorous, demanding life of a nun was not for the physically or emotionally fragile. Ill health, particularly bad eyesight or “sore eyes,” was listed on numerous occasions. Seventeen-year-old Rose Gertrude Parker “returned [to secular life] on account of weak eyesight.” One candidate in 1906 had “poor eyesight and [was] very nervous.” Other comments focused on the candidates not having the “requisite qualities.” One had a “hard temper,” while another was deemed “very odd.” In 1916, one candidate, obviously struggling with the vow of obedience, was sent on her way and labeled “very saucy.”

24 The documents demonstrate that this was a mutual selection process and that the two and a half years prior to taking vows provided the candidate and the community with ample time to assess the lifelong commitment and “fit” of each candidate. Although the mistress of postulants and novices knew the reasons that an individual left, the woman’s peers were never told. The other novices usually discovered the absence in their group the next morning at mass. Except in private conversations, the names of the excluded would never be spoken again.

Even after the sisters were professed and took vows, convent practices continued to build the sense of community and bonding. All nuns addressed each other as “sister” or as “mother,” depending on their office in the community. The leader of the order, or superior general, was always addressed as “Reverend Mother.” Historians of women have long realized the importance of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century boarding schools and other female settings that provided this type of familial nurturing and naming. In these Protestant and secular environments, older girls “adopted” younger ones and were called “mother” by their young peers. Settlement houses created similar bonding relationships, and settlement leaders and colleagues were often fondly referred to as “mother” or “sister.” African American churchwomen and other evangelical Protestant groups also utilized the familial terms to denote respect and sisterhood within the group. These female worlds of ritual and interaction provided important environments for molding, supporting, and uniting their members.

25In these multigenerational, female environments, secular or religious, younger members cared for older or ill members while the older or mature members provided all manner of educational support, nurturance, and discipline, serving as role models for younger or newer members. In fact, in her discussion of the Chicago settlement community, Hull House, Kathryn Kish Sklar comments on the community’s lifelong substitute for family life, stating that “it resembled a religious order, supplying women with a radical degree of individuality from the claims of family life and inviting them to commit their energies elsewhere.”

26As part of this female support network of postulants, novices, and professed sisters, apprenticeship and mentoring provided important emotional, psychological, and vocational training that formed individual and group identity, enhancing the educational messages implicit in convent education. Apprenticeship was a particularly important part of convent education. After one full year in the novitiate and participation in all the required classes, many second-year novices were expected to begin teaching in the various parish schools or working in a hospital or social service setting.

27 In discussing nineteenth-century women’s lives, Carroll Smith-Rosenberg described the apprenticeship experience as a factor that “tied the generations together in shared skills and emotional interaction.” The more stable the connection between generations, the more the young accepted the older women’s world, expecting and perpetuating a women’s support network.

28 The convent environment created and perpetuated this intergenerational bonding and support system, ensuring assimilation for its young members, both novice and professed.

Mentoring provided young sisters with support not only within the convent setting but outside in the public domain. Because the demand for sisters was so great, second-year novices often began teaching, nursing, or doing social service work with very little formal preparation. Older nuns were assigned as mentors to help the young nuns through their early days of fear, anxiety, and unfamiliarity with the work situation. Life at Our Lady of Good Counsel convent on Cass Avenue in St. Louis encouraged mentoring for young teachers in the early twentieth century. Over i oo nuns lived together and taught in twenty-two parish schools. Sister Rose Edward Dailey wrote, “Here the young sisters and many second year novices began their first years of training. It was truly a community of sharing, because here the experienced teachers guided the young sister as she began her apostolate of teaching.... Among so many companions, we found many talents.”

29 Like the nuns in their convent setting, secular and Protestant women also maintained educational, religious, and organizational environments that provided mentoring opportunities.

30Because so much of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century life was spent in single-sex settings, deep, lifelong friendships were prevalent and seen as quite natural for both men and women. The convent was a place where lifetime friendships formed and where women gave much of their time and energy to each other and worked toward mutual goals. In fact, one scholar has argued that close convent friendships encouraged even greater community achievements. “In a masculinist world and church, a convent community in which women were encouraged to be worthy of each other’s and God’s love was a powerful motivation for many achievements that nuns have wrought from the early monastic period to the present.”

31 Historians of women have described the “homosocial bonds” of nineteenth-century women’s friendships that defined relationships along a broad continuum of lifetime sharing and caring among family members or close friends.

32However, even in the less judgmental atmosphere of same-sex friendships in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century America, convent culture warned novices and professed sisters against “particular friendships.” A sister was not to be exclusive in her ties to any one sister. Special friendships occurring in a close, communal setting were seen as detrimental to community, potentially divisive, and often an impediment to the vows, not just of chastity but also of obedience. Under a vow of obedience, sisters were often transferred from one mission site to another, and good friends could be separated indefinitely depending on the needs within the community.

33 Writing to a newly professed sister in 1907, Mother Elizabeth Parrott of Los Angeles advised the young nun to “have

no particular friendships.... Now is the time the instructions you received during your novitiate will be called upon to guide you.”

34Since most Americans prior to the 1920s viewed women as less sexual than men, same-sex friendships rarely had the taint of sexuality that would be associated with them later in the century.

35 Like Protestant and secular women, particularly those who spent time living or working closely together, sisters in the convent setting found that religious life offered an opportunity for enduring friendships and longtime companions. Even with the “warning” against special friends, convent archives document many close ties between sisters who lived and worked together for decades.

36Although secular comparisons are intriguing, the religious community utilized a very direct method of education that clearly distinguished it from secular and Protestant women’s communities and organizations. As religious women, novices and professed followed very stringent guidelines concerning prayer, mass, and other spiritual exercises. As if in a time warp, American nuns worked in the contemporary public culture but were still expected to participate in a strict schedule of religious exercises, many dating from the Middle Ages.

37 Mary Ewens provides insight on how sisters might have reconciled outdated, centuries-old practices with their active lives in American society: “An authentic spirituality, common sense, and a sense of humor enabled [sisters] to separate the essential from the nonessential. Practices that were anachronistic or silly were looked upon as God’s will for religious. That was reason enough to carry them out, however unreasonable they might have seemed to an outsider.”

38Along with the long, and sometimes physically demanding spiritual exercises, prayers, and meditations before and after a strenuous work day, the novices and professed participated monthly in the “Chapter of Faults.” This activity required each novice and professed sister to publicly confess minor transgressions, ways that she had failed to live “The Rule” (i.e., breaking silence, temper display, etc.), to her superiors and peers. If she did not confess or if her confession was deemed incomplete, other community members were encouraged to reprimand her by stating her transgressions in front of the entire group. After acknowledging her mistakes the sister was to “listen with humility to the correction ... and accept the penance imposed.” Similar to public shaming techniques used by colonial Puritans and eighteenth-century colleges, the “Chapter of Faults” provided a powerful incentive for appropriate behavior and an opportunity for sisters to display humility through open confession. The attitude that no one was perfect or above correction included the community superiors as well.

39 This “public shaming” supplemented the required private confessions of transgressions that sisters made weekly to the priest confessor assigned to the convent.

Much of the sisters’ training and experience reflected aspects of both traditional gender and religious ideology. Gender ideals associated with Victorian womanhood demanded that women be passive, self-effacing, and self-sacrificing in order to prove their “natural” femininity and to counter and temper their more “naturally” outgoing, self-centered masculine counterparts. As Colleen McDannell and other scholars have noted, Catholic women, particularly in middle-class families, embraced traditional ideas of Victorian womanhood and domesticity.

40 Individuals, male or female, who joined a religious community were trained to embrace humility by subsuming the self within the larger community, working toward the greater good of others. However, unlike male religious, women religious, socialized from childhood in appropriate female behavior, received a double dose of instructions on humility, self-sacrifice, and passivity, since these behaviors were expected and reinforced in both patriarchal secular society and within the context of religious life.

41 The CSJ Rule, Customs Book, Spiritual Directory, and Novitiate Manual consistently maintained the importance of these behaviors, and approximately one-third of the “Maxims of Perfection” stressed the need for humility, self-effacement, and self-sacrifice.

42For nuns this meant avoiding “singularity” or the appearance of standing out in any way. Similar to the silent woman behind the man, individual nuns were subsumed within the community. Special talents were to be hidden to avoid pride or any temptation to receive individual accolades for activities. According to CSJ historian Patricia Byrne, for a sister to appear “singular” would be “a serious transgression of good convent manners.”

43 Consequently, most sisters have left sparse records of their personal achievements or thoughts. CSJS involved in nursing during wars or epidemics or other dramatic events have rarely written about their feelings or accomplishments unless they had been asked by superiors to do so.

44 Uniformity of dress, manners, and attitudes insured absorption into the community rather than individuality. Priests, especially members of religious orders such as the Jesuits and Franciscans, were also encouraged to take on selfless and self-obliterating behaviors, but as males they received quite different messages from secular society.

45Unfortunately, this “requirement,” coupled with similar gender messages, prevented nuns from taking ownership of their talents, their work, and their major contributions to Catholic culture and American life. The Maxims of Perfection instructed, “Let your actions be hidden in time, and known only to God.... [R]ejoice more when in the eyes of the world it appears that His glory is promoted by others rather than by yourself.”

46 In effect this prescribed avoidance of recognition gave male clerics permission to ignore sisters’ efforts and at times take credit for their achievements. A good nun would not challenge such expectations. Struggling with religious hierarchy, male privilege, and patriarchal interference, women religious had to appear to acquiesce or remain detached while attempting to control their institutions, maintain their community’s autonomy, or even receive simple acknowledgment and recompense for their services. As in the gendered struggles of many Protestant and secular women, sisters could assert themselves only on behalf of others—an acceptable “feminine” trait that women have historically utilized in efforts to gain agency in a patriarchal society.

47On the other hand, nuns also utilized religious traditions and symbols to subvert gender limitations and expand their possibilities. In her discussion of the relationship between gender and religion, Carolyn Walker Bynum writes that all human beings are “gendered” and that “no participant in ritual is ever neuter.”

Religious experience is the experience of men and women, and in no society is this experience the same. Gender-related symbols, in their full complexity may refer to gender in ways that affirm or reverse it, support or question it.... [M]en and women of a single tradition—when working with the same symbols and myths, writing in the same genre, and living in the same religious or professional circumstances—display certain consistent male/female differences in using symbols.

48For example, Protestant women, drawing material from the Bible, have utilized the “androgynous” qualities of Jesus and St. Paul’s epistle, “there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus,” as ways to attack gender limitations and claim “moral authority” and female agency in their various churches, schools, and philanthropic endeavors, legitimizing their presence and influence in the private and public domain.

49 Madeleine Sophie Barat, founder of the Religious of the Sacred Heart, certainly understood the potential influence of women on religion and society when she wrote in the early nineteenth century, “More than ever, the hope of salvation will be in the weaker sex. The men of our time are becoming women; transformed by faith, the women can become men.”

50Like Protestant women, nuns used their own religious symbols and tradition to create new identities that, as Bynum notes, had the potential to reverse or minimize gender limitations. As nuns, women had the prerogative to identify with male gender and status in certain ways. Names and titles often expressed gender oxymorons. Many sisters’ religious names came from male saints or martyrs. A demure, tiny nun became Sister St. John or Sister George. The 1860 CSJ Constitution refers to the superior general as the “Mother General,” blending female nurturance with the status of a male military title.

Emulation of male role models also expanded gender prerogatives. Through the prescriptive literature, CSJS were encouraged to emulate the lives of male saints, to welcome the most severe deprivations and even risk martyrdom if necessary. Their CSJ patron and male role model, St. Joseph, provided incentives for patience, stoicism, and hard work. Most importantly, to justify sisters’ behavior and at times create space for their endeavors, CSJ prescriptive literature encouraged them to emulate Jesus and his “sacrifice” for others. Although the Virgin Mary is venerated, the CSJ prescriptive literature encouraged CSJS to model themselves after Jesus; the literature is strangely silent on emulation of Mary. Part of the formation process included self-discipline and the willingness to forgo physical comfort, individuality, and other human needs. The goal was shared sacrifice and the development of “Christ-like virtues.”

51 This emulation of Jesus’ work took nuns into the public domain to succor the needy, wherever they were found.

Even symbols specifically associated with females could be perceived in ways that evoked power and influence. Although committing one’s life to virginity and becoming a “bride of Christ” symbolized a “safe” alternative to heterosexual marriage, it also signified a direct connection to the “divine spouse,” a role no mortal man could attain. Additionally, this elevated status set nuns apart and effectively “transferred allegiance from worldly men and the larger expectations of women’s roles as wives or mothers.”

52 In her study of nuns across two millennia, Jo Ann Kay McNamara writes that this “independent” existence has often been perceived as a perennial threat to male control and power over women’s bodies and behavior. In response, the patriarchal church has attempted to control these “loose” women with regulations and/or cloistered convents, while secular officials, particularly in Protestant America, denigrated the commitment to convent life, convinced that women could not freely choose to become nuns—that coercion must be involved.

53Utilizing two thousand years of history and tradition, CSJS also learned about and identified with female saints and religious women who challenged prescribed gender roles. European convents produced some strong, female role models who defied patriarchal privilege and took on “male traits” by asserting their right to become scholars, mystics, and spokespersons for their faith. They used the convent to write, think, and live autonomous lives even at the risk of punishment. St. Teresa of Avila, one of only two women designated as a “Doctor of the Church,” engaged in theological discourse when this was forbidden to women, and she is a particularly important role model for CSJS. Complimenting her brilliance, one of her male admirers stated, “She is a man.” Comments made about her frequently describe her as “a virile woman,” “a manly soul,” and “endur[ing] all conflicts with manly courage.” Living in sixteenth-century Spain during the Spanish Inquisition, Teresa walked a tightrope of gender and religious orthodoxy.

54In addition to the utilization of religious symbols and traditions to modify some gender limitations, another important factor that dominated convent formation and had the capacity both to suppress and to encourage female autonomy was the profession of three vows—poverty, chastity, and obedience.

55 Although the vow of poverty could be used to justify lack of payment or underpayment of their services, it also aligned CSJS with the majority of their constituency, the Catholic immigrant population. The vow of poverty justified harsh living conditions and gave CSJS the strength to endure significant physical and financial deprivations in more primitive areas of the country. The vow of chastity prohibited sexual thoughts or behavior, but it also provided a buffer against male sexual advances as well as heterosexual marriage, and allowed sisters access to isolated settings on the frontier and other male-dominated milieus with less fear of scandal or unwanted sexual attention. They used this vow as many Protestant women utilized the ideology of “passionlessness” to gain moral superiority, public space, and agency over their bodies and activities.

56 Lastly, the vow of obedience provided a double-edged sword of submission and strength. Although holy obedience provided a hierarchical structure in which both female and male dictators could flourish, it also created a barrier to clerical control, particularly for communities that had “papal approbation” like the CSJS. Female superiors and superiors general stood between most individual CSJS and male clerics. When the superior general wanted to say “no” to a bishop she could ultimately withdraw her sisters from his diocese or use communication with Rome (which took weeks, months, and sometimes years for an answer) as a method to stonewall or ultimately refuse a demanding bishop.

Even with uniformity of dress, schedule, values, and training, two factors had the potential to divide a religious community or limit its influence. Differences in class and ethnicity provided challenges for the CSJS as they did for other communities in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. European convents maintained a class consciousness that continued with communities like the CSJS that transplanted to the United States. From the beginning this attitude was problematic, for it clashed with American ideals of egalitarianism and equality. Besides the dowry issue discussed earlier, this class consciousness was evident in the convent practice of a two-tiered membership—choir and lay sisters.

57 Choir sisters wore a veil and participated in activities that required some education such as “teaching and works of charity.” Lay sisters wore a “cap of black taffeta without veil or band.” They had minimal education and were “chiefly devoted to manual labor and to domestic duties” in the community. Lay sisters had no voice in community elections and ranked below the choir novices.

58Although one of the six original sisters who came from France in 1836 was probably a lay sister, Bishop Rosati had encouraged the group to discontinue the lay dress because of its unpopularity with American Catholics who viewed the lay habit as a marker of servant status within the religious community.

59 Even without the distinctive clothing, it appears that sisters were working as lay sisters in the 1840s and that the lay habit was reintroduced in the early 1850s. The memoirs of Sister Febronie Boyer indicate that she was a lay sister and that the lay habit was reinstated. Sister Febronie entered the CSJ community in 1848. She was raised by her father in Old Mines, Missouri, where she was a baptized and confirmed Catholic but without the benefit of any formal schooling. She came to the convent at age fifteen, having never seen a nun. “When the community found that I could [recite] the ‘Veni Creator’ they rejoiced thinking they had received a great scholar and were disappointed that I knew very little.” Ultimately, she was given charge of the kitchen, although she had never seen a stove. Sent to Cahokia, Illinois, at the request of Mother Celestine, she was supposed to study when her work was finished in the kitchen. The more class-conscious sisters in Cahokia refused to give her time to study or to allow her to learn to write. Sister Febronie said that once the lay habit was reintroduced, some of the first sisters who received it left the community soon after.

60Although the CSJS did not abolish the distinction between choir and lay sisters until 1908, Americanization had its effect in modifying or blurring the distinction between the two classes of sisters. In the 1847 French constitution, the lay sisters are referred to as “servants.” Even though the lay habit was reintroduced in the 1850s, the first American constitution in 1860 demonstrated that the sisters understood the limitations of this distinction. No longer called “servants,” the lay sisters, although expected to do domestic work, could, “if necessary ... be otherwise employed.”

61 The reality of the situation was that they were desperately needed to work as teachers and caregivers for young children. Likewise, the choir sisters could also “be otherwise employed,” and in the primitive conditions of their nineteenth-century missions, CSJ choir sisters often found themselves engaged in the lower status jobs of cleaning, cooking, and other domestic chores. Even Sister Febronie’s duties went well beyond domestic work. During her seventy years as a CSJ, Sister Febronie worked as a teacher of religion, chapter councillor, local superior, and procurator as well as cook, laundress, and housekeeper.

62The demands of the American environment, both practical and ideological, eventually forced the CSJS to discontinue this classist distinction. During the General Chapter meeting of 1908 and with strong encouragement from Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul, who labeled the practice “Un-American,” and “antiquated and practically meaningless,” the CSJS abolished it, although for many years it remained a sensitive issue until lay sisters were “integrated” fully into the community.

63A less significant class-related problem brought regional rivalry and discord. In 1866, Mother Assissium Shockley was appointed as the provincial superior in the Eastern province of Troy, New York. Born of a family whose origins dated back to the Revolution, Mother Assissium was well educated and not easily intimidated. After her appointment as provincial superior she began a massive building project to erect a provincial house/novitiate, even though the Eastern province had little money and only small numbers of recruits. Apparently her building ideas were considered too extravagant by the motherhouse in St. Louis, but she forged ahead, acquiring most of the money through her own fund-raising abilities. Undaunted by opposition from St. Louis, Mother Assissium felt that “the bone of contention seems to have been the introduction of the modern improvements which up to that time were not seen in any of our convents.” Clearly the sisters in New York had access to more “modern conveniences” in the late 1860s than their counterparts west of the Mississippi, who probably had different understandings of “poverty” and “humility.”

Mother Assissium’s class-sensitive superiors in St. Louis were not the only ones stirred up by her plans. The local Know-Nothing Party, fueled by anti-Catholic sentiment, also responded to her ambitious building project. Spurred on by this visible and audacious symbol of “popery” rising on the Troy hillside, their annual event of burning St. Patrick in effigy on the frozen Hudson River took on new meaning with the new novitiate and large statue of St. Joseph looming nearby. Trouble was anticipated the day of the dedication, but Mother Assissium had loyal defenders at the ready. “A number of Catholic men headed by a brawny butcher with a meat axe” confronted the “bigots,” and Mother Assissium, the novitiate, and “St. Patrick” were all saved from the torch.

64Despite the heterogeneous ethnicity of American Catholicism, ethnic rivalries abounded, and convents and religious orders were not spared from this potentially divisive issue. For some orders of religious women, ethnic problems caused divisions and at times impeded a community’s ability to recruit postulants. Some of these orders, particularly Irish and German, retained their homogeneous ethnic identity, and some German orders, hoping to maintain linguistic and cultural purity, expected their English-speaking postulants to learn German upon entrance.

65As discussed earlier, part of the reason that the CSJS survived and continued to grow was that they were able to Americanize quickly, particularly in the linguistic transition from French to English. Margaret Susan Thompson points out, for example, that, unlike many communities of women religious, the CSJS and the Sisters of the Holy Cross in Indiana, both from France, were able to provide a “melting pot” of ethnic heterogeneity very early in their American foundations.

66 As evidenced by their American constitution and customs book, the CSJS nonetheless saw a danger of ethnic and class division and took steps to limit problems by adding a clause, not present in the earlier French constitution, to their vow of obedience: “[Sisters] should detest the spirit of independence, of nationality, and of faction, that, laying aside all worldly considerations of personal qualities, and of advantages, which they enjoyed in the world, all pretensions to privileges and favors on account of talents, natural or acquired [they may] labor with perfect union of will to procure the glory of God and the salvation of their neighbor.”

67 The CSJ Customs Book of 1917 told sisters that “to question novices and postulants with regard to their station in life, their family or similar subjects ... is in direct opposition to the religious spirit, which we are obliged to inculcate in word and manner.”

68In a community diversifying as quickly as the CSJS, attempts to eradicate ethnic and/or class prejudices were necessary to insure unity and avoid, as much as possible, ethnic infighting. By the 1870s, American-born outnumbered foreign-born sisters, and over the next fifty years this trend continued. The American-born/foreign-born ratio remained two to one until the 1910s, when 90 percent of all new candidates were born in the United States. Between 1836 and 1920, the nationality of foreign-born sisters remained diverse and represented nineteen countries. The largest groups came from Ireland, Canada, Germany, and France, but the community also included women from countries as disparate as England, Russia, and Mexico. Although the number of American-born CSJS of immigrant parentage is impossible to assess, an informal analysis of the CSJ Profession Book documents the preponderance of Irish and, to a lesser extent, German surnames.

69Further analysis reveals some interesting provincial or regional differences among foreign-born sisters. St. Louis, St. Paul, Troy, and either Tucson or Los Angeles were the geographic headquarters of the four regional provinces.

70 Not surprisingly, the vast majority (72 percent) of Canadian-born members entered the St. Paul province and all French-born sisters entered either in France or in the St. Louis province, where the community began. Three-quarters of all German-born entered in St. Louis, which reflected the city’s large German population. The rest of the German-born sisters entered in either St. Paul or Troy. Mexican-born women entered in Tucson, Los Angeles, or St. Louis. All fifteen Russian-born sisters entered the Troy province between 1906 and 1919. Lastly, the large Irish-born contingent entered in all four provinces, but half of the 632 Irish women entered in St. Louis, with St. Paul and Troy also boasting large numbers of recruits from Ireland.

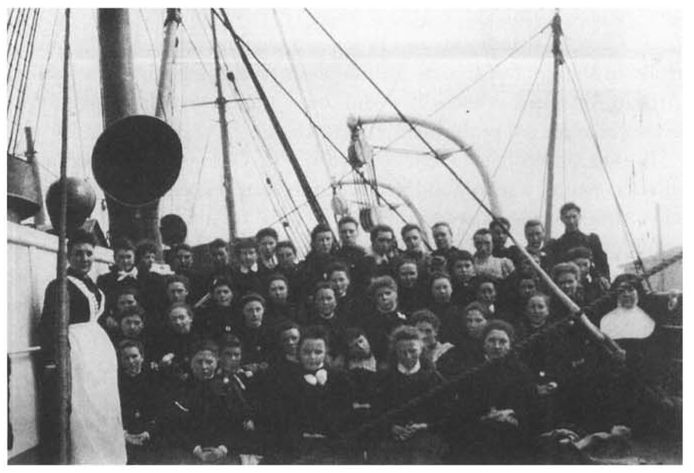

71As was the practice of many religious communities in the United States, the CSJS took recruiting trips to garner candidates to help handle the heavy demands of their missions in America. Sisters from St. Paul went to Canada and Ireland to secure recruits, and sisters from Troy and St. Louis made numerous visits to Ireland. In 1898, thirty-seven of the fifty-five postulants in St. Louis had been recruited from Ireland, and eight more entered the following year.

72Sister Ailbe O’Kelly was seventeen when she and four friends left Ireland in 1911 with two CSJS who had come to recruit from Troy, New York. Full of life and ready for adventure, the adolescents could hardly be contained by the sisters. Spending their first night in a hotel before boarding the ship to New York, the girls amused themselves by dropping chicken bones on unsuspecting passersby and quickly dropping to their knees to say the “Third mystery of the Rosary” when one of the sisters came to check on them. Later, on shipboard they played pranks on passengers and crew. “We had more fun on that boat,” Sister Ailbe recalled. “Everyone thought we were let loose out of an orphanage.... [The older nun] was so worried about us. We were having so much fun; I think she thought we were going to fall overboard.” After a brief stop in New York City, where the girls “thought the people were crazy” because they were “running and wouldn’t wait for nobody to pass or move or anything, [they] were glad to get on the train [to Troy].”

73Thousands of young women like Sister Ailbe came to the United States to enter the convent, and many others entered religious life after emigration from Ireland. What made Irish women such good candidates for religious life in the United States? Historian Hasia Diner’s book

Erin’s Daughters in America provides some insights into this phenomenon. Diner states that Irish emigrant women outnumbered their male peers and many migrated in “female cliques,” as did Sister Ailbe. The young women hoped to escape economic and social factors that made their future life in Ireland a grim prospect. Women left Ireland because “they could not find a meaningful role for themselves in its social order [and] American opportunities for young women beckoned.... Ireland became a place that women left.”

74Other aspects of Irish culture made a religious vocation particularly appealing for these young women. The Irish married later, and gender segregation and celibacy were far more common in Irish culture than in other European countries. The Catholic church, clergy, and women religious were highly respected in Ireland. Irish orders of nuns were rarely contemplative but functioned as activists, working in the everyday world of teaching, healing, caring for destitute women and children, and administering all types of social services. Nineteenth-century Irish women were at the forefront in founding new religious orders in Ireland and the United States. As Diner writes,

These young women, the daughters from the thousands of small farms that dotted the countryside, the daughters of the survivors of the great Famine, saw themselves not as passive pawns in life but as active, enterprising creatures who could take their destiny in their own hands. Although possessed of a profound religiosity that belittled what people could do for themselves to alter the course of human events, the Bridgets, Maureens, Norahs, and Marys decided to try just that.

Forty-five Irish “recruits” who came to the United States to join CSJ communities in St. Louis and Troy, New York. This is a shipboard photograph of their arrival on the Pennland in the port of Philadelphia, 1898. (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Archives, St. Louis province)

Irish women were prime candidates for religious orders in the United States, and recruiting trips, undertaken by many religious orders, proved to be fruitful endeavors.

75Although the Irish recruitments were successful and the young women seemed to integrate easily into the CSJ community, race remained a barrier to CSJ diversity. The nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century CSJS taught and interacted with Native Americans and African Americans, as did most other Catholic sisterhoods and Protestant churchwomen, but they never made an attempt to integrate their order by receiving Native American or African American women. They did successfully recruit Hispanics, however, which proved problematic nevertheless.

In 1892, Sisters Julia Littenecker and Monica Corrigan visited Mexico to discuss opening a school and to recruit Mexican women into the community. Although the CSJS were making inroads in Arizona and California, ethnic prejudice and the impoverished circumstances limited their recruiting efforts in the Southwest. The Arizona novitiate became the home for six Hispanic novices, but Anglo parents, who did not appreciate the “foreign aspect and primitive conditions,” sent their daughters east to St. Louis for their novitiate. After fourteen years, having recruited only a handful of new vocations, the novitiate closed.

76Sisters Julia and Monica were unsuccessful in negotiating a CSJ school in Mexico, but they returned to St. Louis with fourteen Mexican girls and women who entered the postulate in 1892. Cultural differences proved to be too much for five, who returned within the year to Mexico.

77 Struggling to make a success of their Western missions and needing a novitiate in the West, the CSJS decided in 1899 to reopen the Western province. After a three-year study the novitiate opened its doors in fast-growing and ethnically diverse Los Angeles. This locale proved to be a wise choice because the new novitiate steadily gained candidates each year, including some Hispanic women from CSJ Arizona missions.

78The ethnic heterogeneity of the CSJS made them popular with priests and bishops whose ethnic parishes often preferred sisters of a similar ethnicity. Nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century American Catholic life revolved around the ethnic parish, and the parochial school provided the focal point. Ethnic rivalries abounded, and clergy and sisters had to be savvy about working with individuals with a variety of national loyalties.

79 In 1911, when Sister Mary Eustace Huster told her mother that she wanted to enter the CSJS, her German-born mother refused permission because she did not want her daughter in an “Irish Order.” Her mother relented when a CSJ explained that “we have sisters of different nationalities including German and we need sisters who could teach German.”

80 This ethnic adaptability and diversity enhanced the CSJS’ influence as they were called to serve in small towns and urban centers throughout the United States.

In a way the CSJS had the best of both worlds. By the late 1800s, their ethnic diversity opened doors in many parts of the country, but the predominance of Irish among them provided them with distinct advantages that contributed to their growth and influence and gave them access to power in both the secular and religious worlds. Many Irish American men were attracted to politics and the church. By the turn of the century, many major cities were controlled by Irish political machines that doled out monies for city and state charitable institutions, many of which were run by nuns. Additionally, American Catholic life was heavily influenced by Irish culture because a large majority of the male hierarchy were born in Ireland or of Irish descent. In 1900 half of American Catholics were of Irish descent, but 62 percent of the bishops were Irish, and so were a large number of parish clergy. Among the diocesan clergy of St. Louis, Germans outnumbered the Irish but eleven of twelve clergy promoted to the episcopacy between 1854 and 1922 were Irish.

81 Clearly, power in the church came from Irish connections, and this gave the Irish-dominant CSJS added influence and clout.

82Although Irish women flooded into the CSJ community, a few notable sisters born in Ireland or of Irish parentage struggled with the regime and became mavericks or free spirits who left the Carondelet community or founded their own orders. In the 1860s, Irish-born sisters Blanche Fogerty and George Bradley remained angry over the introduction of general government and both left the Carondelet community. Sister Blanche asked to be transferred to the Wheeling community, which had become diocesan and separate from Carondelet. Two years later, still resisting centralized authority, she left the Wheeling community and the Catholic Church, “obstinately refusing to accept the dogma of Papal Infallibility.”

83 Sister George, a former provincial superior of the St. Paul province, left the community in 1868 with four other sisters who were also disgruntled with general government. She pursued a different track: she left her current community and, at the request of a bishop in another diocese, established a new diocesan foundation with herself as superior general. American bishops were in such dire need of sisters that they encouraged these “unattached” and sometimes disaffected nuns to come and work in their dioceses. Sisters might leave a particular community, but they could remain vowed religious and start over in a new setting as founders and/or members of a diocesan order. In Sister George’s case she became the founder of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Cleveland and one of her companions, Sister Aurelia Bracken, eventually founded a community in Lewiston, Idaho.

84Sometimes sisters left to “escape” conflicts with their female superiors, but just as often they left because of battles with male clergy and bishops. Sister Stanislaus Leary, born in New York to Irish parents, had been the first CSJ postulant in Canandaigua, New York. At the time of general government and the split with Carondelet, she chose to stay in the Buffalo diocese. When the Rochester diocese was formed in 1868, she became the superior general of this CSJ diocesan community. In the early 1880s she and Bishop Bernard McQuaid had a “misunderstanding” over some property willed to the sisters. In 1882, he deposed Mother Stanislaus and ordered the sisters to elect another superior. Ignoring the bishop’s directive, the sisters voted Leary back into office, but he immediately overruled their vote and installed his own candidate as superior. In a diocesan community, Mother Stanislaus had no alternative but to accept the bishop’s decision or leave the community she had led for fourteen years. She left the diocese and went on to found two CSJ diocesan communities and assisted in the foundation of two more.

85The case of maverick Sister Mary Herman Lacy (a.k.a. Sister Margaret Mary Lacy) perhaps best illustrates the gendered politics that encompassed the life of a woman religious. Unlike other CSJS who left a community, she had no intention of starting her own foundation, but a series of clashes with members of the male hierarchy resulted in her founding two diocesan communities and helping to found a third. By all accounts Lacy was well educated and multilingual, with considerable business acumen. Physically attractive and assertive, she had an independent spirit and enthusiasm that attracted young postulants. The chronology of events leading up to each founding is difficult to sort out, but her gendered power struggles are evident in various sources. Accounts of two events that precipitated her leave-taking survive. Both incidents probably occurred in the early to mid- 1870s, and both involved her challenges to male authority.

86While serving as superior at the Cathedral School in Albany, New York, Lacy became embroiled in a dispute among the clergy of the diocese. Her biographers believe that she, as well as several priests, may have been trying to protect a well-liked bishop who had alcohol problems from the attempts of his coadjutor, Bishop Francis McNierney, to have him removed from office. McNierney, who won the dispute and became bishop, ordered Lacy out of his diocese for her insubordination and strong verbal support of the former bishop. Soon thereafter, Lacy was involved in another conflict that also demonstrated her independence, confidence, and unwillingness to be bullied as well as the sexual double standard regarding insubordination.

87After working a few years in the Midwest, Lacy returned to New York. While a superior in Albany, she visited a CSJ friend who was a superior in Kansas City. During the visit she was told of rumors that her friend was being “too friendly” with a local priest. Satisfied that the rumors were false, Lacy ignored them until the Kansas City bishop, John Hogan, summoned CSJ superior general Agatha Guthrie to Kansas City, demanding to know why nothing had been done in response to these rumors. After being reprimanded by the bishop, Mother Agatha was told that Sister Mary Herman Lacy had also known about the “scandal.” Summoned from her convent in Albany to Kansas City, Lacy met with Bishop Hogan, her accused CSJ friend, and Mother Agatha Guthrie. All were “exonerated” (including the accused priest) except Sister Mary Herman Lacy. Her sin had been to verbally challenge and infuriate the bishop. Apparently during the meeting with the bishop, she made an impassioned argument on her friend’s behalf, quoting canon law and directly challenging the bishop’s authority. To placate the bishop, Mother Agatha removed her from office and sent her to “rest” until matters calmed down.

88Frustrated, Lacy left the CSJS and became a postulant in the community of the Religious of the Sacred Heart in Brooklyn. Unfortunately, during her postulancy, Bishop Hogan of Kansas City happened to pay a visit to the Sacred Heart Convent. He pretended not to recognize her, but as soon as he returned to Kansas City he wrote the bishop in New York, who forced the Sacred Heart sisters to dismiss her. After that she disappeared, and what she did next is disputed by community historians. She appears to have traveled about, stopping with various CSJ diocesan communities that took her in for periods of time.

89Records indicate that in 1880 she began a diocesan community in Watertown, New York, renaming herself Sister Margaret Mary. Her community struggled economically, but some of the sisters went on to establish a new foundation in Tipton, Indiana.

90 Battling illness, disappointment, and dissension within the Watertown community, she left Watertown and founded a community in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Soon after her arrival she and Father Frank O‘Brien, the parish priest who had invited her to Kalamazoo, clashed. He began interfering in the internal affairs of the community and demanding her unquestioned obedience to his wishes. As a ruse, he sent her on “vacation” with his biological sister and upon her departure deposed her as superior, appointing another sister who would follow his orders. Unaware of his actions, she wrote letters to her community informing them of her whereabouts and activities. Father O’Brien intercepted her letters to the sisters, told them she had run off, and ordered her locked out of her convent when she returned. O‘Brien accused Lacy of “disrespect to priests and ecclesiastical (male) superiors ... criticizing and making light of them generally.” Frantic to get her community back she attempted to contact O’Brien, but her letters went unanswered. Unable to comprehend her assertiveness and lack of submission to his authority, Father O’Brien lamented her “queer way of acting” as if

she were in charge, not himself or the bishop. Ultimately, he wrote her and accused her of insanity:

I believe, what I have had reason to presume for a long while, that you are insane, and a proper course of treatment at the Asylum is what you stand in need of. If, however, you are sane, no explanation is necessary. The vile language of your letters must be atoned for and the proper penance received and performed. When you express a desire to do this in the proper language of a lady, not to say religious, I will then, and only then, consent to an interview.

91Out of desperation Lacy agreed to a mental examination, and the doctor found her exhausted, emotionally stressed but totally sane. She was ordered from the diocese by the bishop and was told that if she returned she was to be treated as “an intruder.” Ill, exhausted, and emotionally spent, she wrote Mother Agatha Guthrie, her former superior, who allowed her to return to the Carondelet community in St. Louis and eventually resume her original rank.

The saga of Sister Mary Herman Lacy provides a portrait of the limitations experienced by American nuns. The need for sisters and their labor in nineteenth-century dioceses opened doors for individual autonomy and the creation of new religious communities. However, this “liberation” went only so far since women’s power and authority could be limited by male clerics and bishops, particularly in diocesan communities. Like their Protestant and secular counterparts, women religious who challenged male authority often found themselves ostracized and labeled “unladylike” and their very sanity questioned. The entrenched male hierarchy of the American Catholic Church provided a formidable obstacle for nuns who either lacked the political savvy to maneuver through this gender and hierarchical minefield or who simply chose not to play the game.

Religious identity and gender created space for women religious within the parameters of nineteenth-century American life. Convent culture and education provided messages that challenged gender ideology even as they reinforced and maintained it. Similar to their Protestant and secular counterparts, women religious lived in a world of ambiguities that gave meaning and value to their lives and work at the same time that it limited their opportunities. Women who were members of religious communities like the CSJS became a powerful, trained workforce (numbering 90,000 by 1920) who lived in female settings across the country, teaching, nursing, and caring for hundreds of thousands of Americans, both Catholic and Protestant.

92 Convent training and education prepared them physically, mentally, and spiritually to relinquish individual needs and identity in favor of community identity and cohesion. Trained to persevere even in the most difficult of circumstances, they placed themselves on the cutting edge of institution building in the American West and throughout the nation in schools, hospitals, and social welfare settings.