4

Expanding American Catholic Culture

We were quite far from the church and there were not as yet any

streets or roads in St. Paul. All they had done was to cut down

trees in a row and leave all the stumps.... Once the snow came

we would sink in two or three feet, or we would walk over it as if

It were ice. It was on one of these mornings that the hungry wolf

tried to get a piece or all of my body.

—Mother St. John Fournier

The Trans-Mississippi West

When the first CSJS arrived in St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1851, the town was a small frontier community, isolated in winter by the frozen and impassable Mississippi River. After spending the previous four years in the “civilized” confines of Philadelphia, Mother St. John Fournier and her companions learned to thrive and develop new skills in the rugged, primitive environment typical of much of the American West in the nineteenth century. As the federal government claimed land from Native American and Hispanic peoples through military campaigns and treaties, women religious, like Protestant and secular women, traveled west and helped build towns and cities in many areas of the United States and its territories.

Although male religious orders, particularly the Jesuits and Franciscans, had been in the trans-Mississippi West for centuries, the influx of white settlers, especially immigrants, created new opportunities and new demands for services. Responding to the opening of lands for white settlement, Protestants and Catholics jockeyed for moral and cultural influence, hoping to save the bodies and souls of Eastern transplants, European and Asian immigrants, Hispanics, and native peoples who populated much of the American West. Lyman Beecher’s A Plea for the West stirred many Protestants to “save the West from the Pope” and work toward fulfilling the nation’s manifest destiny through the spread of Anglo-Protestant influence and culture. Calling the Catholic Church “the most skillful, powerful, dreadful system of corruption ... slavery and debasement to those who live under it,” Beecher skillfully used fear to galvanize Protestants to fund “introducing the social and religious principles of New England” to Westerners.1 Hoping to promote their own religious and cultural influence in the West, Catholics, with contributions from European philanthropic associations, aspired to support “the growth of the Roman Catholic Church in Protestant and heathen countries, and more specifically, ... Catholic missions in the United States.”

2

Both Protestant and Catholic women participated in this battle for the minds, hearts, and souls of the multiethnic peoples of the trans-Mississippi West. Scholarship in Western women’s history has provided new insights into the gendered and multicultural dimensions of life west of the Mississippi River.

3 However, nuns have remained mostly invisible in more recent Western history and in Catholic histories of the West. Discussing the historiography of Western women and religion, some scholars have noted, “The study of religion has led scholarship in two different directions : the first an examination of the church as an institution and as a community ; the second a reading of personal conversion and vision. Within these parameters, whether as witches or as missionaries, women have generally been placed within the framework of American Protestantism.”

4The experiences of nineteenth-century women religious are critical to understanding the interaction of gender, ethnicity, religion, and class in the American West. American sisters were some of the first white women brought in to “civilize” newly forming towns and other areas of settlement. Male clerics, who usually preceded the sisters’ arrival and often had large territories to cover, frequently functioned as itinerant clergy, forced to travel vast distances to serve Catholic parishes and communities.

5 The sisters came in larger numbers and were important shapers of American Catholic culture and public life because they worked directly with the people on a daily basis, administering and staffing some of the first religious, educational, health care, and social service institutions in isolated frontier settings that included both Protestants and Catholics. The scarcity of clergy meant that women religious often functioned as surrogate priests at baptisms, at religious services and ceremonies, and at the death bed. They trained the children, helped the poor, nursed the sick, and buried the dead.

6The sisters’ ability to accommodate and adapt to rugged, and sometimes dangerous, frontier conditions enabled them to provide much needed educational and social services to men, women, and children in a variety of Western settings, counteracting the often hostile, anti-Catholic attitudes prevalent in nineteenth-century America. Mary Ewens states that “it might well be shown that sisters’ efforts were far more effective than those of bishops or priests in the Church’s attempts to meet these challenges. It was they who established schools in cities and remote settlements to instruct the young in the tenets of their faith, who succored the needy ... who changed public attitudes toward the church from hostility to respect.”

7 Using their religious beliefs, convent training, and vows, the sisters, by their early presence in the American West, were at the forefront of the development and expansion of Catholic culture.

The work CSJS did to build institutions in three diverse geographic locations and milieus in the West illustrates their adaptability and influence there. First, St. Paul, Minnesota, and Kansas City, Missouri, provide representative examples of the urban West and how the sisters shaped American Catholic culture in settings that began as frontier camps and grew into important regional centers. Second, the sisters’ greatest challenges may have been in the Southwest, specifically Arizona and California, where they experienced cross-cultural interactions with Hispanics and Native Americans. Finally, the predominantly male, Rocky Mountain mining communities of Central City and Georgetown, Colorado, supplied their own obstacles.

Urban West

Both St. Paul and Kansas City were “frontier towns” in the mid-nineteenth century. In each place the CSJS were called by local clergy to open a school and provide an early visible presence of American Catholic culture. The sisters, though challenged by the journey and the physical deprivations, poverty, and isolation of the first few years, filled a variety of needs in these ethnically diverse settings. By the end of the nineteenth century, as economic, commercial, and transportation advantages placed St. Paul and Kansas City on a course for growth, prosperity, and regional prominence, the CSJS were deeply rooted in St. Paul and adjoining Minneapolis, in Kansas City and western Missouri. Through their successful participation in town building and a variety of educational, health care, and social service institutions CSJS made important contributions to American Catholic culture and public life in the urban West.

To meet the people’s needs Bishop Cretin sought French- and English-speaking sisters who were willing to come to the northern and isolated setting to work with a variety of ethnicities, including Native American. Turned down by other groups of nuns, Bishop Cretin invited the CSJS, whose ethnic profile and variety of work experience would fit well in his new diocese.

9 With the opening of agricultural lands, Minnesota and the St. Paul/Minneapolis area soon attracted large numbers of people, including Germans, Scandinavians, and Irish. In addition to this population explosion, the twin cities experienced significant economic and commercial growth between 1865 and 1900 and soon became a shipping, transportation, industrial, and agricultural hub for the region.

10Similar to the first convent/school in St. Louis, the first CSJ home in St. Paul had a prominent location on the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River; but it had little else to recommend it. Sister Francis Joseph Ivory described their “small frame shanty” and “privations of the most severe kind”: “We had a small stove on the first floor—the pipe of which was set upright through the roof, around this opening we could count the stars; the rain storms were frequent. When the rain poured down through the roof, we (like the man in the gospel) would take up our beds and walk, but only to rest in the water on the second floor. As there was only one well in the place, and this was generally locked, we often had a long wait for our coffee in the morning.

11In spite of the physical deprivations, the sisters persevered, opening the first Catholic school in the territory, St. Joseph’s Academy, and also began teaching at the Winnebago Indian Mission, 100 miles north of St. Paul. In 1854, with the large influx of immigrants, the CSJS moved boldly to open the first hospital in St. Paul and the state, although they had actually begun nursing in the city and caring for orphans during the outbreak of cholera a few years earlier. Within three years of arriving in St. Paul the sisters had established an academy, an Indian school, and a hospital/orphanage; and as Minneapolis began expanding across the river, the CSJS extended their activities in both communities, providing multiple services to the two cities and the region.

Over the next six decades as the twin cities grew and prospered, the CSJS became leaders in education, health care, and social service.

12 By 1920 they created and/or staffed fourteen parish schools (plus catechism classes in twelve other parishes), three academies, a music and art conservatory, two hospitals, two orphanages, and a women’s college. The CSJ contribution to American Catholic culture and service in St. Paul/Minneapolis encompassed thousands of schoolchildren and hospital patients and hundreds of art/music students, orphans, and young women in secondary and postsecondary education.

13Kansas City, Missouri, also began as a “glorified frontier camp” that, according to one historian, even prostitutes avoided in the 1850s. The town was best known as a “jumping off spot” for the Overland and Santa Fe Trails and as a haven for proslavery renegades who made intermittent border raids into “Bleeding Kansas.” In 1861 the town’s 4,000 inhabitants were joined by Union troops, who established a military outpost after the outbreak of the Civil War. Kansas City boomed after the war when the town won the rights to the economically strategic railroad bridge over the Missouri River that connected the city to Kansas and Western markets; the town’s future seemed assured. Like St. Paul in the late nineteenth century, Kansas City grew as a transportation hub and as a center for social, commercial, and economic interests. The addition of the railroad stock-yards in the 1880s established the city as the regional center of agricultural markets.

14Predicting economic prosperity and an influx of settlers, Father Bernard Donnelly, a local priest, called the CSJS to serve the fast-growing Catholic population. But, however promising the future may have seemed, in 1866 when five CSJS arrived to begin a school, led by forty-two-year-old Sister Francis Joseph Ivory, Kansas City was still a “cow town.” Upon arrival, the sisters found unpaved dusty or muddy streets, ugly wooden buildings, numerous saloons, open drunkenness, and frequent fights among a rough and transitory population that included many thieves and gamblers.

15Pennsylvania-born Ivory, who had fifteen years earlier founded the St. Paul mission, was an important member of many “advance teams” to new mission sites because of her strong physical endurance, education, interpersonal skills, and her ability to speak English. Arriving in Kansas City by train in 1866, Sister Francis Joseph utilized her years of experience in beginning new missions. Within weeks, she had acquired free railroad passes for the sisters and quickly raised funds for the convent/school. “We took possession of the walls as the house was not furnished,” she wrote. “Our first possession was a cow—We got up an entertainment, and in one night cleared Thirteen Hundred Dollars thus we were able to furnish the house in necessaries. Providence came to our aid, that we had no difficulty in getting along on temporals.” The sisters’ school, St. Teresa’s Academy, opened that fall with 150 pupils (girls and small boys) and for the next twenty-five years was the only Catholic school providing more than an elementary education for girls in Kansas City. Although other religious orders had institutions in western Missouri, nuns in habits were still a novelty in Kansas City. As Sister Francis Joseph humorously recalled, once when a group of them were traveling across town, “the people thought we were the Circus.”

16As was true of CSJ institutions in St. Paul, those in Kansas City grew with the city’s population and prominence. In 1874 the sisters opened St. Joseph’s Hospital, the first private hospital in Kansas City and one of the earliest in the trans-Mississippi West. Having cared for orphans in all their institutions, they established a separate orphan home for girls in 1880.

17 By the early twentieth century, the sisters had expanded their teaching activities into a number of ethnically diverse parish schools, educating Irish, Germans, Hispanics, and a growing Italian population.

18 By 1920, when Kansas City’s population had grown to more than 300,000, the CSJS had established or were staffing many successful institutions in Kansas City, St. Joseph, and Chillicothe. Serving thousands of women, men, and children, Protestant and Catholic, they conducted twelve parish schools, two academies (elementary and secondary), an orphanage for girls, a hospital, and a junior college for women.

19The CSJS in St. Paul and Kansas City are good examples of the important role women religious played in town building in the trans-Mississippi West. In both cities, CSJS established institutions that were among the first in the city and/or state. Like Protestant and secular women who formed organizations and groups to promote schools, health care, and social services, sisters provided labor, time, and monies by caring for children, the sick, and the poor of society. To these raw frontier towns the sisters “brought higher education with its appreciation of culture and the arts, as well as practical science,” particularly in the education of girls.

20 Many historians of the West have described the importance of Eastern capital, government subsidies, and the migration of families in creating the urban West, thereby rejecting the myth of the rugged, lone male riding into the sunset, unencumbered by family and society, and “winning” the West. Clearly, institutions such as churches, schools, hospitals, and orphanages helped support frontier families by providing much wanted and needed community services. The sisters’ and Protestant women’s organizations were important builders and caregivers that helped these towns thrive and grow into urban centers.

21

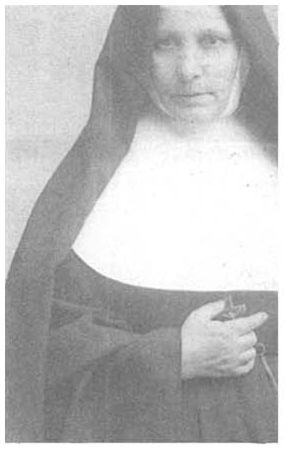

Young girls feeding the chickens at St. Joseph’s Orphan Home for Girls in Kansas City, Missouri, 1910 (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Archives, St. Louis province)

Even with gender and religious ideology supporting women’s active work, nuns, like their Protestant counterparts, often needed the support of influential males to make their institutions a reality in the gendered and patriarchal world of nineteenth-century America. Similar to Protestant women who utilized the monetary and political connections of male relatives and friends, the sisters benefited from networking with clerics who had the political clout and influence to serve as “town boosters” in the secular realm and as advocates of the sisters’ projects in promoting Catholic culture in their cities. In both St. Paul and Kansas City, CSJS had male advocates with the power and foresight to provide invaluable economic, political, and social support for their endeavors.

In St. Paul, Archbishop John Ireland played a leading role in CSJ successes, encouraging, if not propelling, the sisters into prominence and power. Even before his sister Seraphine took over the leadership of the St. Paul province in 1882, Bishop Ireland had provided extensive monetary and political advantages that made the CSJS the preeminent female religious group in St. Paul for decades. Nationally and internationally known, John Ireland brought thousands of Catholic immigrants to Minnesota and interacted with an extensive network of powerful men in business, government, and the clergy.

22 Besides providing financial support for the CSJS he helped them secure new mission sites and institutions, sometimes by removing the competition.

23Father Bernard Donnelly, a local priest, also proved to be a strong advocate for the early Kansas City CSJS, although he had little of Archbishop Ireland’s national clout. Donnelly was a trained civil engineer whose skills were utilized by early town builders and developers.

24 A savvy businessman whose vision and planning helped shape Catholic growth and influence in Kansas City, he invited the CSJS to become the first female religious order in the city and helped provide for their monetary needs, at times using his personal funds to support the academy, and later the hospital and orphanage. For over two decades his shrewdness and foresight supported the CSJS’ institution building and strengthened the Catholic community and its recognition in Kansas City.

25Religious and gender ideology and the support of influential males provided an effective combination for justifying and encouraging women’s presence and work in the public domain. And the types of community services that women provided were often seen as a responsibility of the church as well as a continuation of nurturing activities that women performed in their families. Furthermore, since religious affiliation was such an important marker of nineteenth-century life, the religious rivalry between Catholics and Protestants may have aided the proliferation of female institution building. The animosity and suspicion between Catholics and Protestants made separate institution building desirable and often necessary as each group “competed” for clients. Certainly Catharine Beecher and other Protestant educators utilized gender ideology and fear of Catholicism to raise funds for female seminaries to train Protestant teachers to “save the West” from teaching orders of nuns whose success they both respected and feared.

26 In discussing women’s push to establish “female moral authority” in the American West, Peggy Pascoe describes the difficulty Protestant women had when they encountered women whose “influence emanated from ... sources” other than their traditional roles as wife and mother. The behavior and activities of nuns were particularly problematic for women who viewed Protestantism as elevating to the status of women. Through their eyes nuns were degraded as women and “a Catholic embarrassment.” According to historian Mary Ryan, Protestant women saw themselves as benevolent “guardians of immigrant children, often of Catholic background.”

27Likewise, American Catholic clergy and sisters utilized the threat of Protestant proselytizing and bigotry to secure thousands of dollars from European and American philanthropic sources and to justify the need for sisters and their work. Hoping to acquire CSJS for a Western school, one cleric wrote to Reverend Mother Agatha Guthrie asking her to help him save the children from “our arch-enemy and his helpers ... and accept that school and prevent it from dropping into Protestant control.”

28 Such inflammatory rhetoric as well as the real competition that existed between Protestants and Catholics opened doors for nuns and Protestant women to help fund, staff, and administer educational and caregiving institutions. From their initial journey to St. Paul and Kansas City in the mid-nineteenth century until 1920, the CSJS contributed with other women religious to the building of urban centers throughout the West. The CSJS expanded and shaped Catholic culture in locations such as Fargo and Grand Forks, North Dakota; Denver, Colorado; Tucson, Prescott, and Yuma, Arizona; and San Diego, Oxnard, Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Francisco, California.

29

Southwest/Indian Mission Schools

In 1870 the CSJS moved into a second Western locale that provided physical, educational, and interpersonal challenges unlike any previous missions. On April 20th a band of seven CSJS left the motherhouse in St. Louis to travel to Tucson, Arizona Territory, to open a school. This move would open Arizona and eventually California to the sisters, allowing them to continue their institution building in newly expanding towns and cities and on Indian reservations. More importantly, however, it gave the CSJS opportunity to work in what one historian has called a “frontier of interactions” or a “cultural crossroads” among the various multicultural groups in the Southwest.30 Besides encountering a plethora of European, and to a lesser extent, Asian immigrants, the sisters established institutions that put them in touch with a variety of Native American and Hispanic populations in settings where race, class, religion, and gender collided in a myriad of intercultural and cross-cultural interactions.

31 Although the CSJS were certainly not the first group of women religious in the Southwest, their experiences provide a good representation of the journeys, deprivations, activities, and accomplishments of other American nuns who worked in the region.

32

Sister Monica Corrigan’s journal offers intriguing insights into the CSJS’ thirty-seven-day odyssey to Tucson by train, ship, and overland trek. The seven sisters traveled by train from St. Louis to San Francisco, where they boarded the steamer that took them down the coast of California to San Diego. From there they rode and walked for twenty days to reach Tucson. Along the way Sister Monica recorded sights, events, and feelings about her experiences. As in the accounts of many women who traveled west before and after her, it is her personal perspective that fascinates and gives the reader the opportunity to see the West through her eyes.

33Before making her historic journey, Sister Monica (born Anna Taggert) had taken a unique path to the convent. Born in Canada to Anglican parents, she eloped with John Corrigan, a Catholic, and moved to Kansas City, Missouri. In 1866, she found herself a widow at twenty-three, her husband and two children dead from diphtheria. Utilizing the college training in mathematics that she had received in Canada, she began teaching at St. Teresa’s Academy and within a year had converted to Catholicism and joined the CSJS. After taking vows in 1869, she was sent with five French-born nuns and an Irish-born lay sister to Tucson the following spring. Although her newness to religious life kept her from being appointed superior of the Tucson-bound sisters, she was chosen for this difficult assignment because the CSJS “needed a woman with more worldly knowledge than many of the others had. Having been in Canada, at the university, and married and a widow, her experience was wide.”

34The train ride began April 20, 1870, with stopovers in Kansas City and Omaha, Nebraska. West of Omaha the sisters encountered four Protestant missionaries and their wives in the dining car, and Sister Monica noted, “Whether owing to our presence or not we do not know, but religion was the principal topic of conversation. ... Everyone maintained his own opinion and proved it from the

Bible, agreeing only on one thing, Catholicity is intolerable.”

35 Later in the journey while traveling through Utah, Sister Monica, having some sense of her own preconceived notions, expressed her sentiments about another religious group—Mormons: “They arc a degraded looking set, but perhaps it is prejudice that makes me think so.” Winding their way through the chasms and gorges on the narrow train tracks through the Rocky Mountains, an excited sister urged Sister Monica to “wake up and take notes” as the “silent” passengers “enjoyed the scenery” but prayed to survive “dangers, terrors, and perils of the place.”

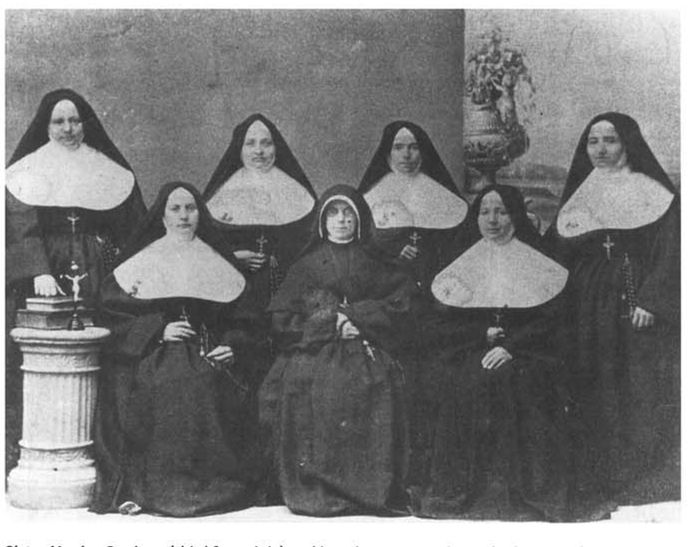

Sister Monica Corrigan (third from right) and her sister companions who journeyed to Tucson in 1870. The sister in the center wears the lay habit. (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Archives, St. Louis province)

Upon reaching San Francisco the CSJS lodged with the Sisters of Mercy, who fortified them with provisions for the sea journey, which included “some crackers and a couple of bottles of liquor.” After four days on the ocean battling seasickness, the sisters arrived in San Diego, where they stayed for three days preparing for the final twenty-day trek to Tucson. On May 7th, the seven sisters and their male driver headed east in their covered “spring wagon” into the desert. The heat, desolation, and unknown “terrors” of the desert must have frightened them considerably. French-born Emerentia Bonnefoy, superior of the group, was nearly “inconsolable” when she heard “wolves” howling the first night, fearing that they would eat her and “all of our crackers and tea.” Trying to calm her down, the driver said, “to her great consolation and our amusement, that there was no danger as wolves in this country had no teeth.” Mother Emerentia was less assured when she was awakened one night by screams from the driver and Sister Martha Peters, who in the darkness had been tending the fire and mistakenly grabbed the sleeping driver’s leg thinking it was a log. Mother Emerentia’s trials continued when, walking ahead of the wagon one morning to pray, she became lost. The sisters and driver became very concerned and went looking for her. When the driver finally spotted her, he began running toward her and yelling to attract her attention. “When Mother saw the man in pursuit of her, not recognizing him, she was terribly frightened, and ran too, as fast as she could.”

At times the sisters stayed at ranches or lodges along the way, but even this “luxury” had its challenges. In an environment where males far outnumbered females, the sisters found themselves in difficult situations. At one ranch a group of men proposed marriage to them, and at another they had to fight off a group of drunken men who “annoyed us very much.” At a later stopover, the sisters were forced to share a “stable” with “40 men” who were boarding for the night.

The greatest challenge of the twenty-day trek was the terrain itself and the accompanying physical deprivations and dangers. Sister Monica described the difficult trials they endured—trials that at times may have challenged their faith and resolve. They came upon “thousands” of dead cattle and sheep and a spot where only a month earlier a stage had been buried in a sudden sandstorm, leaving the seven passengers entombed inside. Probably to allay fears and anxieties, the sisters “sang nearly all the time,” alternately walking and riding. Dressed in their woolen black habits and veils, they were poorly equipped for the extreme heat and rugged terrain of desert and mountain crossings. An exhausted Sister Monica wrote, “For several miles, the road is up and down mountains. We were obliged to travel on foot. At the highest point it is said to be four thousand feet above the level of the sea. We were compelled to stop here to breathe. Some of the Sisters lay down on the roadside, unable to proceed any farther. Besides this terrible fatigue, we suffered still more from thirst.” Blistered by the “scorching sunbeams” and unaccustomed to walking in desert terrain, one sister suffered even more physical discomfort: “One of the sisters happen to wear ‘low’ shoes. Her feet and ankles were badly scratched, her stockings bloody and sticking to her. On removing her stockings, there were 22 bleeding sores produced by cactus thorns that had worked their way through her stockings.”

Relieved to see Fort Yuma, the Colorado River, and water ahead of them the sisters faced another near disaster. To expedite the river crossing they were told to stay in the wagon, which would be secured to a raft for crossing. During the crossing, when the raft carrying their wagon tipped as one of the horses fell, Sister Monica managed to leap to safety. She watched in terror while her six companions teetered over “17 feet of water” before two men with ropes could stabilize the carriage.

When they reached Fort Yuma they were joined by Father Francisco, who had been sent by Bishop Salpointe to accompany them to Tucson. To avoid the heat during the final leg of their journey, the group began traveling more at night; Martha Peters, the Irish-born lay sister, shared some of the driving duties to allow the driver and Father Francisco time to sleep. Approximately seventy-five miles west of Tucson, sixteen soldiers, “some miners,” and “citizens” arrived to accompany them through “Apache territory” Once they were within three miles of the city on the evening of May 26th, they were given an exuberant welcome: “We entered the city about 8 o’clock P.M. As we approached the crowd increased ... some discharging firearms, others bearing torches. The city was illuminated, fire-works in full play, balls of combustible matter thrown in the streets through which we passed, many of them exploding, bells ringing. At every explosion, Sister Euphrasia made the sign of the cross.”

36The culmination of this incredible journey resulted in the first of many CSJ institutions in the Southwest. During the next fifty years CSJS built and/or staffed schools, academies, hospitals, and orphanages in medium and large cities throughout Arizona and California. Because of the distance from the St. Louis motherhouse, the CSJ presence and successful institution building spawned a novitiate and a new Western province, its headquarters originally in Tucson and later relocated to Los Angeles. Besides “urban” successes during the first fifty years, the CSJS also dramatically expanded their work with Native Americans in both Arizona and California. They participated in “contract schools” funded by the federal government and worked with the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions (BCIM) by staffing boarding and day schools. Although they had already administered and staffed some schools for Native Americans in Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin, the CSJS experienced some of their most difficult challenges in the more primitive and isolated settings of the American Southwest.

37In 1869, before the CSJS arrived in the Southwest, as part of President Grant’s peace policy a board of Indian commissioners, composed of wealthy, mostly Protestant laymen, was created in an attempt to monitor government subsidies to Native Americans more effectively and provide a more consistent educational system for Indian children. Many religious denominations agreed to provide supplies, furnishings, buildings, and other educational necessities to Indian children in return for a fixed annual per capita appropriation from the federal government. To counteract “federal prejudice and to augment their native evangelical apostolate,” Catholics created the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions to fund and oversee Catholic mission schools.

38 When monies became available for these “contract” or government schools, the BCIM lobbied Washington for funds, assisted and helped finance Catholic Indian schools, and attempted to protect Catholic mission schools from “Protestant” interference.

39 As part of this Catholic push to increase and expand work with native tribes, religious orders like the CSJS were asked to send sisters to staff the schools.

40The CSJS’ work with native tribes in the Southwest began with Papago and Pima children, south of Tucson at San Xavier del Bac Mission in 1873.

41 Four other Indian mission schools followed: Fort Yuma Government School in Yuma, California (1886), St. Anthony’s Indian School in San Diego (1886), St. Boniface Indian School in Banning, California (1890), and St. John’s School in Komatke, Arizona (1901).

42 Although these schools differed in size and longevity and had varied financial resources and native support, they were typical of many schools run by nuns and provide insights into the cross-cultural interactions of race, class, religion, and gender.

The CSJS had come to the United States with a mandate to work with Native Americans, but funding for this work had always been problematic. By far the greatest share of monetary support given to the BCIM and directly to Catholic sisterhoods for work among American Indians came from one woman—a nun, Mother Katharine Drexel. A Philadelphia heiress who entered the convent in 1889, Drexel founded her own order—the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored People in 1891.

43 In her book

The Catholic Philanthropic Tradition in America, Mary Oates states, “As Catholics generally ignored appeals for Indian schools, Drexel was nearly singlehandedly subsidizing them when government funding ceased entirely in 1900. She channeled most of her donations through the [BCIM], concerned that if the extent of her personal largess became known, grassroots contributions would decline even further and the church would be publicly embarrassed.”

44

CSJS and Native American students at San Xavier del Bac Mission in the 1890s (Courtesy of the Arizona Historical Society/Tucson, B#109,287)

Even with the millions of dollars provided by Mother Katharine Drexel, CSJ Indian missions and most missions staffed by women religious barely survived, and living conditions, for both the Indians and the sisters, certainly reflected the deprivations of life at the mission schools in the Southwest. Arriving at Fort Yuma, one sister described the CSJS as “children of ‘holy poverty’. [The] Government does not supply furniture nor rations to the employees of these schools. They have to supply themselves.”

45 Sisters at San Xavier del Bac “shoveled bat dirt and debris” from their convent/school and begged boxes from Tucson merchants to use as desks for students. Battling with desert creatures for living space, Sister Bernadette Smith described several days and nights of burning pans of sulfur in their sleeping quarters “to oust the centipedes, scorpions, tarantulas ... which had nested there for years. As a result they began to fall half dead upon the floor from the dried mud which formed the ceiling. When one of these things would fall, the Sister who saw it first would call out its name, then we would run and get a broom or stick and finish him only to find another one soon again.”

46Letters and memoirs of sisters who worked at the missions described the poverty of the Indian people and the constant “begging” done by the sisters to secure funds and clothes. “The Indians were very poor.... [W]e frequently suffered from shortage of food.... We had no horse, cow, goat—not even a chicken. There was no well and the water had to be carried quite a distance.”

47 Sisters at government schools often faced similar shortages while waiting for promised government supplies to materialize. One sister recalled, “In answer to our request for fifty pairs of overalls for the boys, it was not unusual to receive one hundred pairs in the shipment. Then, at other intervals, our petitions would be of no avail.”

48 At St. John’s School the children had only one change of clothing, if that, and during their weekly baths “whatever shawls we had or anything that could be called a covering we put on them ... until their clothes were dry.”

49 CSJS used their vow of poverty to justify and deal with their own deprivations, but the poverty and the deplorable living conditions of the people often interfered or took precedence over the activities in the schoolroom.

When the CSJS were not addressing the daily needs of the children and adults on the reservation, they taught the basic academic curriculum used at most Indian schools in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Like mission schools run by Protestants and secular groups, the sisters’ schools reflected the prevailing stereotypes held by white Americans in regard to educating Native American children. Viewed as “uncivilized,” and “undisciplined,” Indian children were subjected to a strict routine with the goal of inculcating white, middle-class values that included “proper” ideas about dress, speech, manners, and work habits—all perceived to be lacking in native cultures. A daily regime of religion classes, vocational skills training (domestic and industrial), and basic education in the three R’s formed the core of Indian mission education.

50 Sometimes music and art were part of the curriculum, and the entire structure of the day was interspersed with military drills or calisthenics to insure discipline and wean children, particularly boys, away from “Indian time” and lack of submission to authority. Vocational classes reinforced gender stereotypes of Victorian America. The sisters taught the academic basics to both sexes and domestic skills to girls; male religious or a priest taught the older boys vocational skills. If no male clerics were available to work with young males, laymen were hired to teach farming, military drill, and discipline.

51Many historians have documented the misguided and unsuccessful aspects of this ethnocentric curriculum, regardless of whether it was taught by Protestants or Catholics. Children who succeeded in gaining basic skills and who assimilated some white middle-class values often became alienated from their families and culture only to be rejected again by white society. Many children succeeded in absorbing white culture while at the school but at the end of the term simply returned home to resume their former cultural practices.

52Although the CSJS adhered to the prescribed curriculum, when it came to certain cultural and religious practices some sisters clearly showed a degree of admiration for and acceptance of native culture. The nuns attended some Indian social activities and were fascinated with their dances, music, and native games. Sister Marsina Power was enthralled watching the women of San Xavier play a ball and stick game. She admired the colorful clothing, free-flowing hair, and athletic prowess of the Papago women. Sister Marsina attended dinner in Papago homes and described the women as “good cooks” who extended “exquisite courtesy” to strangers.

53 At times the sisters were more than spectators. When picnicking with the schoolchildren, Sister Bernadette Smith wrote, “I took part in their modest little dances which they had taught me. We went in a line one after the other with a certain step and carrying a little branch of a bush.”

54 Some sisters also made every attempt to learn the language of the people in order to prepare them better for spiritual guidance and conversion. Mother Mary Aquinas Duffy learned the Papago language in two years, and Sister Mary Thomas Lavin served as an interpreter so a local priest could provide instruction for engaged couples who were to be married in the church at Fort Yuma.

55Working toward the goal of Indian conversion, the sisters also may have benefited from both their visible role as “holy women” and the symbols, rituals, ceremonies, and sensuous aspects of Catholicism. Jacqueline Peterson and other historians have hypothesized that the various Catholic statues, rituals, and symbols that so offended Protestant eyes might have been accepted more readily by Native Americans, who sometimes chose to “graft” Catholic rituals onto their traditional religious customs. Although Native American religious practices are highly diverse, Peterson writes, “It is likely that American Indian peoples responded most positively to Christianity when a convergence of religious symbolism or ceremony revealed itself.” She adds that “rosaries” and other “power objects” could “add to the store of sacred paraphernalia revered by American Indian people without disrupting traditional beliefs.”

56Some CSJS seemed to feel that motivation and fervor might be more important than perfecting the aesthetics of religious practice. As preparation for one Catholic observance, a young man named Venancio was asked to decorate the “Blessed Mother’s altar for the month of the Holy Rosary.” Venancio was devoted to honoring the Virgin Mary and had spent many hours in the church, caring for the altar and statues. However, the sisters were somewhat surprised when they saw his approach to honoring Mary. “When we gathered there the first day ... the statue of our Blessed Mother was painted yellow. She had a little straw hat on her head and the ribbons were tied under her chin. The altar was banked with flowers, which were hard to get, all put in tomato cans as we had no vases. This was Venancio’s way of doing honor to our Blessed Mother.”

57The CSJS reported some religious conversions and intercultural successes, but their greatest contribution may have been in their humanitarian activities—the spiritual, material, and medical sustenance they provided for children and adults, particularly on the poverty-stricken reservations. The sisters shared much of the poverty as well as many tragedies of the people and did what they could to alleviate suffering. The sisters baptized, held services for, taught religion and catechism classes to, and officiated at funeral services for Native Americans who adopted Catholicism and some Christian spiritual practices. With a shortage of priests, particularly in the Arizona missions, the sisters filled a surrogate role. At St. John’s the sisters had no priest for two Sundays a month, so they would hold “services for our Indians by reciting the rosary and singing hymns.”

58 In San Xavier and Yuma death and hardship came often, and when asked, the sisters would “baptize the dying babies ... sprinkle the home-made coffin containing the dear one, say some prayers, and then go to the grave with the sorrowing ones, speak words of consolation to them. This was done for the older people as well as for the little ones when Father could not be present.”

59Although the majority of Native Americans living on reservations were not Christian, many of them came to the sisters for assistance in time of need.

60 The sisters assumed a “political” and fund-raising role to secure donations and materials to meet the daily needs of children and adults. They wrote family and friends and cajoled local merchants for money, resorted to “begging” to secure funds or material goods, and served as intermediaries between Native Americans and local whites. As a buffer between hostile whites and native peoples, the sisters may have served as what Peggy Pascoe called “intercultural brokers, mediators between two or more very different cultural groups,” thus keeping ethnic hostility and rivalry to a minimum.

61 Taking on this mediator role sometimes meant resisting unwanted government interference. At Fort Yuma, Mother Ambrosia O’Neill corresponded constantly with Washington to secure supplies and had continual confrontations with “inspectors” sent from the Interior Department to check on the “government nunnery” and school. For example, she resisted one inspector’s demand that she enforce harsher discipline practices with the children and parents: “He thought we should punish them or lock them up in prison when they disobeyed.”

62Additionally, the sisters functioned as the only “doctors” during epidemics, and the Native Americans often came to ask for help during these times of illness or disease. During the 1887 measles epidemic at Fort Yuma the people “flocked in great numbers to the mission, begging help from the Sisters.” In San Xavier the sisters crawled on hands and knees into native homes that were “so dark inside that it was necessary to feel until you found the sick person.” Sister St. Barbara Reilly performed many medical duties during her work at the missions. “The job didn’t end at nightfall for a summons might and did come at any time.”

63One of the more fascinating aspects of the CSJ experience in their Indian mission work revolves around the construction of gender roles and how religion, race, and class impacted the sisters’ activities and experiences. Clearly, the sisters’ educational and humanitarian roles crossed gender lines—they functioned as priest, politician, and doctor. More than Protestant women missionaries, they may have expanded gender parameters. Operating in an all-female group, often without the assistance of priests, the sisters were not as restricted by gender stereotypes. Historians tell us that Protestant women also felt a strong call to work among the Indians, but for most that meant marrying a missionary. Most Protestant churches refused to send single women alone or in groups to an Indian mission, which was viewed as too dangerous for them. Single Protestant women usually joined a married couple, living and working with them at the mission.

64 Additionally, Protestant women missionaries carried a double burden of work and responsibility. As a wife and/or mother, a Protestant woman missionary was responsible for her home duties as well as her teaching or working with native women. Nuns had no such conflict of interest or family responsibilities; they had no need to divide their energies and time between private and public work. Their entire purpose for working at the mission was to focus on the needs of the people.

Even without the additional burden of family responsibilities, CSJS and women religious could not ignore the limitations of gender. The CSJS’ fourteen-year experience at the Fort Yuma Government School provides further illustrations of challenges and complications that they faced when gender, race, religious, and class prejudices interacted and boundaries blurred.

Pressured for months by the BCIM to staff the newly formed government school in Fort Yuma, California, Reverend Mother Agatha Guthrie had refused. Primitive conditions, dangerous terrain, and some past difficulties with mission priests caused her to decline. Father Zephyrin Engelhardt of the BCIM, in a twelve-page letter, utilized both religious and gendered discourse to plead his case. He implored her to “make it

impossible for

Protestants to gain a strong foothold among [the tribe].... If that school gets into Protestant hands and those Indians become non-Catholic, I do not think Our Lord would overlook that matter.” He also assured her that the sisters would not have to work under some “narrow-minded man.” He went on to say, “It would be a blessing if no priest were in charge.... [T]he priest is not necessary to carry on the school work there.” And in a last attempt to play on gender he compared the sisters’ work to a that of a “mother, tenderhearted and soothing.”

65Engelhardt’s appeal and a preliminary visit to Yuma by her experienced and multilingual assistant, Sister Julia Littenecker, convinced Mother Agatha to change her mind.

66 Five CSJS, led by Sister Ambrosia O‘Neill, arrived in 1886 to take over the school located at a former army post at Fort Yuma. O’Neill had an exceptional position because she was also appointed as “Superintendent” of the school, a job almost exclusively held by men in Indian mission schools.

67 Her initial contact with the tribal chief, Pascual, and the Yuma people seemed friendly, and they began calling her “El Capitan” out of respect for her rank. Local whites, however, expressed opposition to the nuns immediately. A Mr. A. Frank led the attacks, which were expressed in local gossip and the newspapers. Writing to St. Louis, Mother Ambrosia quotes Mr. Frank as saying that “it was against the laws of the country for a woman to hold an office, and more especially a religious one.... [H]e thinks we are deceiving Washington ... and he would like to know why I did not write my name Sister instead of Mary O’Neill.”

68 Two months later letters to the editor appeared in the

San Francisco Argonaut about the “governmental nunnery” at Fort Yuma that some whites found “galling in the extreme.”

69With the blessing of the elderly and ailing Chief Pascual, the sisters had little conflict with the tribe. When Pascual died and a new chief, Miguel, was elected, however, intratribal conflicts erupted. Unlike Pascual, Miguel openly opposed Christianity and began withdrawing the children from the sisters’ school. Father J. A. Stephan, during a routine visit for the BCIM, attempted to intimidate the new chief. Treating Miguel as a naughty child, Stephan gave him “a good scolding” and threatened to have the “great Father in Washington ... take the children by force and place them in an Eastern school.”

70Although angry and insulted, Miguel appeared to soften his resistance for a while, but after two epidemics (measles and typhoid) and increased government indifference, he blamed the CSJS when he failed to be reelected chief in 1893. In an attempt to punish the sisters and assert his authority, he took thirty older girls, ages twelve to seventeen, from the convent school and sold them as prostitutes to white men, profiting five to twelve dollars a girl.

71 The CSJS were devastated, and conflict continued to escalate. As further revenge, Miguel had planned to murder Mother Ambrosia, but Yumans loyal to the sisters hid her outside the fort and repelled the attack against the convent. Miguel and eight co-conspirators were arrested and sentenced to jail in Los Angeles.

72Faced with dwindling support in Washington, the CSJS at Fort Yuma received less and less material and financial assistance from the government in the 1890s. Interestingly, the CSJS viewed this as hostility from the “Protestants and Republicans,” who they feared would remove them from the school. In reality, the federal government was moving away from providing political and financial support for any church-run Indian schools.

73Driven by growing shortages of food and supplies and residual anger at the sisters, Miguel’s son, Patrick, set fire to the school. Patrick’s arson attempt probably resulted from more than family revenge since a “group of Yuma Methodists” paid legal fees for Patrick’s defense and arranged for Miguel to be present during the trial.

74 Discouraged and frightened, the CSJS resigned at the end of the school term in 1900 when the government discontinued funds. Frustrated with their never-ending struggle with the political and power dynamics of gender, race, class, and religion, the sisters withdrew after a fourteen-year effort.

The sisters, like many Protestant missionaries, gave years of their life to a cause they firmly believed in, providing educational and humanitarian aid to native peoples. Although the devastating impact of federal policy and the ethnocentricity of whites cannot be denied, the CSJS had strived to do and be what their religious ideals had required of them. Their vows and their sense of charity, particularly in humanitarian assistance, guided their actions; and although they certainly made every attempt to indoctrinate the native peoples in white culture and religion, they also made extraordinary attempts to support and assist them, particularly during times of illness and suffering.

Colorado Mining Frontier

Sister Perpetua’s two-month correspondence with Mother Julia Littenecker describes the beginnings of what proved to be a physical and spiritual odyssey for herself, her companion, and the CSJS. But over the next forty years the CSJS became firmly entrenched in the rugged mining communities of Central City and Georgetown, Colorado, where they created and maintained educational, health care, and social welfare institutions.

76The CSJS’ arrival in Colorado in 1877 predated that of most organized Protestant women’s groups, but other nuns had been in the territory since 1864.

77 Similar to preparations for establishing other new mission sites, two sisters were sent to Colorado as an advance team that “networked” its way across the country. Traveling by train from St. Louis to Denver, the two stopped off in Kansas City, where they stayed with CSJS who were teaching at St. Teresa’s Academy. There they left trunks filled with potential lottery prizes to be shipped to Colorado later to be used as a way to make money for the new institutions. When they reached Denver, the sisters boarded at St. Mary’s Convent as guests of the Sisters of Loretto.

78In Colorado, Sister Perpetua Seiler and her young travel companion, Sister Angelica Porter, served as representatives from the St. Louis motherhouse and negotiated directly with Bishop Joseph Machebeuf for purchase of a building and creation of a school in Central City. Machebeuf, a well-known cleric with a reputation as a shrewd businessman, was assisted by attorneys, investors, and advisers in administering diocesan finances and institutions. On the surface, Sister Perpetua appeared to be greatly overmatched. Little is known of her except that she was born in Lyons, New York, in 1837, and her letters give evidence of many years of formal schooling.

79 From March 25 to May 2, 1877, she engaged in hard-nosed bargaining with Machebeuf and was forced to play the middle ground between him and Father Honoratus Burion, the parish priest of Central City.

80 Sister Perpetua’s letters to St. Louis document the bishop’s constant bickering, mood swings, financial ploys, and last-minute pressures to strike a better deal for the diocese at the sisters’ expense. After her first meeting with Machebeuf she wrote, “One dreaded interview with the Bishop is at last over. He is indeed a hard man to deal with.” Seiler firmly held her ground on the price, interest rate, and payment schedule, refusing to assume additional debts incurred by the parish priest and bishop or to offer the motherhouse property as collateral.

81Assuming a role frequently required of other nineteenth-century nuns, Seiler negotiated contractual agreements, traveled to Central City, inspected the building, talked with local parishioners, kept counsel with an attorney and banker in Denver, and set up a soliciting trip that encompassed three states and hundreds of miles. She had to make some important decisions without the advice of her superiors since the mail rarely came consistently or quickly enough to provide complete communication with St. Louis. In fact, she shrewdly used the geographic distance and her vow of obedience to resist and eventually refuse demands made by the bishop. After a particularly grueling two-hour negotiating session, Sister Perpetua wrote Mother Julia that she refused the bishop’s demands by reminding him of her vow of obedience to her own superiors. This tactic proved useful at those times in the negotiations when the bishop became most demanding.

82 After the deal was finalized, she wrote: “The opening is a good one for us in the state, but I am truly sick of it all. Have done everything I could to make all come out right; can now do no more. All our prayers and fatigue have been offered for this end.” Later, feeling much relieved and confident after her difficult five weeks of negotiations, Sister Perpetua suggested that “someone possessed of great tact, prudence and skill in business and virtue to be at the head of the Central City house. Neither of them [Burion and Machebeuf] are hard to deal with, by those who know how to handle them.”

83Like their Protestant counterparts, women religious learned how to subvert patriarchal power in an acceptable but effective way, passing on their strategies for other women to emulate. Sister Perpetua’s letters to Mother Julia show that she clearly knew what she was doing and enjoyed outmaneuvering the bishop. On the day the contract for the Central City properties was to be signed, Bishop Machebeuf had asked that a clause be added to it. Seiler agreed immediately, realizing that the bishop’s clause had no affect on the amount paid by the CSJS. She wrote Mother Julia, “The lawyer had a good laugh at the simplicity of the Bishop. And I know you will have another when I tell you that [the bishop] ... invited me to take up my abode [in Central City.” Clearly the bishop was not in the position to make such a request, and Sister Perpetua once again refused by telling him she would be guided by obedience to her own superiors.

84In discussing power relationships between men and women, Carroll Smith-Rosenberg discourages historians from viewing women as “victims” or as “co-opted spokespersons for male power relations.” Historically, nuns have been seen as both. Smith-Rosenberg believes that one who takes this kind of approach “fails to look for evidence of women’s reaction, of the ways women manipulated men and events to create new fields of power or to assert female autonomy. ... But if we reject the view of women as passive victims, we face the need to identify the sources of power women used to act within a world determined to limit their power, to ignore their talents, to belittle or condemn their actions.”

85 Sister Perpetua Seiler clearly understood the gender dynamics in her interactions with the economically, politically, and religiously powerful bishop. However, it was her gender and her identity as a woman religious that allowed her to appear to acquiesce even as she manipulated the bishop to achieve her ultimate goals. The source of her power came from her identity as a woman and a vowed religious in an all-female community. Publicly, she was polite, demure, and submissive, but she was shrewd in handling the male cleric, who had both his gender and his religious office to buttress his authority.

After signing the contract, Sister Perpetua and Sister Angelica traveled for six to eight weeks with the U.S. Cavalry and the paymaster on a fund-raising mission to all the military outposts in northern Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota. Traveling in potentially dangerous territory only one year after the Little Bighorn battle, they toured Indian reservations, observed native dances, and visited and solicited money from officers and enlisted men. They stayed in the company of the post commander (Catholic or Protestant) and his wife on each stop of the journey. They camped, slept in a tent, and traveled on trains, stagecoaches, ambulances, and freight wagons to their various destinations. To find suitable lottery prizes, they dug for gems and crystals, hiked mountains, explored caves, and panned river beds. Clearly the frontier environment presented the sisters with a range of experiences unknown to most secular or religious women in the nineteenth century.

Like her predecessor Monica Corrigan, Sister Angelica Porter kept a diary of their journey with the army. Although Angelica made it clear that Perpetua required her to keep the journal, she wrote with emotion and childlike wonder of the sights and adventures of her Western travels on the rugged terrain. On a trip to Crystal Cave, the sisters, accompanied only by another woman and her young son, rode in freight wagons up a mountain before beginning their journey on foot. After picking strawberries, flowers, and prairie apples, the sisters entered the cave. Sister Angelica wrote, “[We] descended a very steep side of mountain[,] could scarcely support ourselves and keep from falling. Reached cave after great difficulty. Were first ladies ever in it. Picked crystals and explored it with torch light.” Nineteen years old and Canadian born, Sister Angelica gave a poetic description of the mountain sights around her on their perilous climb: “Saw bone of huge animal miners had found in earth. Named a large rocky peak ‘The Way to Heaven’ on account of difficulty of ascent. Remarkable! Saw a rainbow formed by the reflection of sun on water leaking from flume, crossing the Gulch, the water fell like rain.”

86 Even Sister Perpetua, after her difficult financial dealings in Denver, appreciated the wonders and isolation of the West. On an early soliciting trip, while camped on the Powder River with the military payroll company, New York—born Perpetua pondered the spiritual significance of the frontier setting as she wrote of her feelings to Mother Julia: “The scenery here is picturesque and beautiful. Our tents are camped on the brink of the stream, which is lined with cottonwood trees.... There is to me something sublime in the thought that we have bent the knee in prayer in these far off wilds ... in the wilderness in the midst of 40 armed soldiers.”

87Although steeped in religious and spiritual metaphors, the sisters’ accounts of their adventures are similar to those of other women traveling in the West.

88 As Catholic nuns, they also utilized their vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience to interpret their life experiences. Like many women in the frontier West, they experienced homesickness and at times stringent physical deprivations and difficulties, but seen in religious context, these hardships could be welcomed as God’s blessing and an opportunity to serve God in a more humble and edifying way—the goal of every CSJ. Certainly, the sisters utilized their religious worldview and vows to calm their fears and justify their physical or emotional challenges. Their faith helped them accept and persevere in extraordinarily difficult circumstances in an isolated and potentially life-threatening environment.

89After five months the advance team successfully completed their negotiations and solicitation and had prepared the way for CSJ teachers, and later, nurses, to be sent from St. Louis to create and maintain the new Colorado institutions. In turn, the nuns who settled there adapted their roles, institutions, and social interactions to the specific needs and circumstances of the diverse mining communities of Central City and Georgetown.

90In the 1860s and 1870s Central City functioned as a mining and commercial rival of Denver. The majority of the male population worked in mining or as suppliers to the mines. In fact, Central City’s Gilpin County encompassed one of the most famous gold districts in Colorado. By the 1870s, the merchant class was attempting to attract families and encourage the arrival of clergy and the building of churches and schools. For any mining town this was desirable as the way to acquire long-range stability for the community.

91Central City was the site of the first Catholic parish outside of Denver to be established by the Denver diocese, and Georgetown was the site of the second. Its large Catholic population and wealthy patrons could well afford to support a private academy. When four CSJS arrived in 1877 to open Mt. St. Michael’s Academy, St. Mary’s of the Assumption Church boasted 700 parishioners from throughout Gilpin County. Central City called itself the “richest square mile on earth,” and the townspeople built the CSJ academy on a hilltop overlooking the city; the $30,000, two-story, Gothic revival structure included a bell tower and a large Celtic cross that could be seen for miles. For forty years academy children daily climbed the 150 steps up the hill to Mt. St. Michael’s. When the population of the town peaked in 1900 at 3,114, six sisters were teaching 120 students, Protestant and Catholic, in the academy.

92In 1880, the CSJS accepted the call to Georgetown to open a parish school and a hospital. With silver prices escalating in the late 1870s and 1880s, Georgetown became the “Silver Queen” of the mining towns, and the census of 1880 revealed what would be the population peak for the mining community: 3,294.

93 In contrast to other mining towns, freewheeling dance and gambling halls, saloons, and brothels occupied a “quieter” place amid public outcries for churches, schools, and civic reforms in Georgetown. In a community where families predominated, parents worried about the “moral well-being” of their children and the variety of bad influences present in most mining communities, where 90 percent of the population moved on within ten years.

94 The large contingent of Catholic families had created Our Lady of Lourdes parish in 1866, which boasted the largest and finest church in Georgetown. Unlike the private academy in Central City, where tuition ranged from $1.00 to $2.50 a month, the parish school, opened in 1880, was free to all Catholic children, and 100 boys and girls were reciting lessons by 1885.

95Protestants and Catholics alike welcomed the opening of the CSJ hospital in 1880. Before it opened, local women in Georgetown, as in other mining communities, bore the brunt of nursing care; women who ran boardinghouses and wives of miners often found themselves nursing not only their husbands but other “unattached” men.

96 Although the sisters’ first hospital in Georgetown was located in a former residence, the Demin House, in 1883 the lay board of Protestants and Catholics created a new brick facility. The new hospital, staffed by two doctors and eight nun-nurses, included a large ward and eight private rooms. Most of the patients were miners who paid $.50 a week to use the hospital at any time. Sometimes mining companies paid in advance for all their employees’ hospital stays. Over 90 percent of the patients were males between the ages of twenty-one and sixty-five, and the typical hospital stay was three or four days, or with serious injuries, two to three weeks. The surviving patient lists describe a variety of injuries, accidents, and diseases.

97In the mining communities of Central City and Georgetown, the CSJS faced two potential barriers that had to be overcome for them to create and successfully maintain their Colorado institutions: anti-Catholic sentiment and class and ethnic rivalries. In Central City, where the CSJS established their first school, some anti-Catholic attitudes surfaced as the nuns prepared to initiate their mission in the territory. Earlier, the Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth, who began a school in 1874, left Central City ill and disillusioned, having received no remuneration for their three years of service. In her correspondence to the motherhouse, Perpetua Seiler wrote that the sisters were “withdrawn because they were not happy here.” Local gossip included rumors about conflict between the priest and sisters and an unaccounted for infant staying in the rectory. One sister had “left the order under suspicious appearance.” In a later letter, Sister Perpetua assured Mother Julia that the accusations were false: “There has been no public scandal given here” and the “sisters bear a good name.”

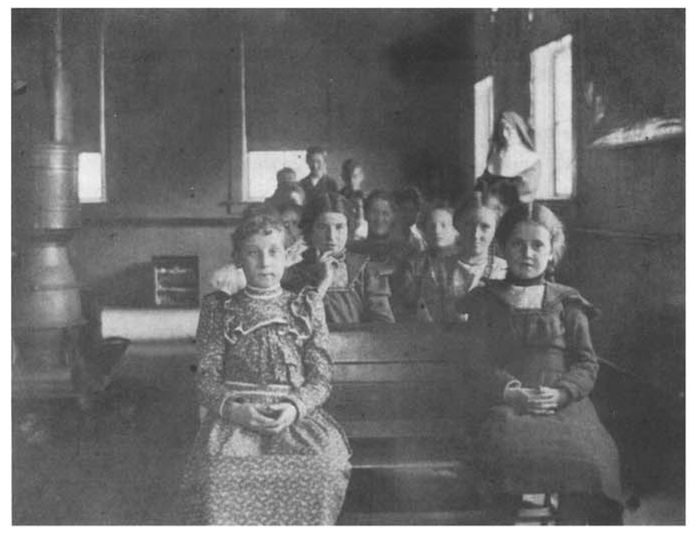

98

Our Lady of Lourdes School, Georgetown, Colorado, late 1890s (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Archives, St. Louis province)

The CSJS worked hard to establish their good name and reduce anti-Catholic attitudes. Sister Perpetua’s letters to St. Louis mention the importance of performing duties for “the honor of Religion.” The sisters’ efforts in Central City appeared to be successful. The academy was filled with students, and community support boomed. The sisters would recall later their successful fund-raising fairs and plays and townspeople throwing money into a big kettle in front of the Teller Opera House on Eureka Street. One account of this incident claimed that thousands of dollars were collected within a few days.

99Even in Georgetown, which had a large Catholic population, religious bigotry surfaced. A local Methodist was appalled at the “gambling” by which “Catholic ladies raised considerable money with raffles.” He went on to describe Catholics as “different” because of their “strange statues and paintings” and because “they had to get up real early on Sunday mornings and go to Mass. Of course, this was compensated for by their being allowed to play ball on Sunday afternoon, and use strong drink, and be forgiven once a week by the priest for all they might have done amiss.”

100Many in the mining town were grateful for the sisters’ attention, however, and “reconciled” their anti-Catholic sentiments. Newspaper clippings from Georgetown referred admiringly to the “Sister’s Hospital.” In describing the community effort to keep the hospital financially solvent, the

Georgetown Courier stated, “The makeup of the [hospital] committee speaks for itself and plainly shows that neither religious beliefs nor nationality enters into the matter in any way whatsoever.” The writer went on to say that the sisters kept the hospital in a “far more efficient manner than a private concern can.”

101 Mr. Thomas West provided a personal testimonial in the July 5, 1888,

Georgetown Courier. Mr. West said he expected his hospitalized Protestant friend would receive “scant attention” and be charged higher prices; however, he assured the local readers that he had witnessed “kindly” care at the hands of the sisters.

102 Clearly, the CSJS in Colorado functioned in an educative role that softened Protestant attitudes toward nuns and Roman Catholics in general.

The CSJS also played a pervasive role in caring for and ministering to the large majority of immigrant Catholics in both mining areas. Religious and ethnic familiarity helped integrate the sisters into the Colorado mining communities they served and enabled them to reduce divisive ethnic rivalries that often prevailed in larger urban settings such as Denver.

103 Either by design or necessity, the CSJS sent a large percentage of foreign-born sisters into Colorado. Of the twenty-two CSJS who served in Georgetown, 40 percent were foreign-born, and their ethnicity matched well with the Georgetown Catholics, who were predominantly German, Irish, Italian, and French.

104 It is clear from the sisters’ records that they also considered ethnicity an important marker of identity and recorded a patient’s birthplace as well as age and other data. Records from the Georgetown hospital provide a representative sample of the heterogeneous mixture of patients. In the thirty-three years of the hospital’s existence, the approximately 1,500 patients admitted for care came from eighteen countries and eighteen different states in the United States. The majority of foreign-born patients were miners who came from England and the predominantly Catholic countries of Italy, Germany, and Ireland.

105In contrast to Georgetown, over half of Central City’s immigrants were non-Catholics from Canada, Wales, and England (largely Cornish). The forty-year roster of CSJS who worked in Central City included 26 percent foreign-born, ethnically matched with the Catholic population that consisted mostly of German-, Irish-, and, later, Italian-born miners.

106 It is also plausible that many of the American-born sisters in both locations were second generation and therefore capable of relating to ethnic, cultural, and language differences within the towns.

Compared to middle-class Protestant women, the sisters bonded and blended well with the local communities ethnically; but equally important, most CSJS and other women religious came from working-class backgrounds similar to those of the people to whom they ministered. Additionally, as a result of their vow of poverty, the sisters knew firsthand of the deprivations and needs of the many Catholic and non-Catholic immigrants and families. Although elevated spiritually in the eyes of their parishioners, their lack of financial security kept them on a par materially with the people they served. Their own poverty helped the CSJS avoid a tendency to patronize the needy, which was characteristic of some Protestant women’s groups.

107By 1917, the mining boom was over, and the CSJS withdrew from Central City and Georgetown; the communities could no longer support the CSJ institutions. The growing population in Denver and surrounding areas had expanding needs, which the sisters met by establishing additional schools and other institutions there. Their forty-year ministry on the mining frontier demonstrates the significance and importance of their activities and provides one of many examples of the religious community’s ability to adapt to life in the American West.

The CSJS’ presence in the urban West, Southwest, and the Colorado mining frontier helped to preserve, sustain, and shape American Catholic culture in the trans-Mississippi West. In all three environments their support networks and institutions provided important services to men, women, and children. Gender ideology, particularly “domestic ideology,” supported the role of both Protestant women and Catholic women religious. In his discussion of “domestic ideology” in the American West, Robert Griswold defines it as “a shared set of ideas about women’s place [that] also bound non-related women to each other.” He goes on to state that domestic ideology strengthened bonds of sisterhood among women by “offering women a cultural system of social rules, conventions, and values—a moral vocabulary of discourse—that gave meaning to their daily behavior and to their friendship with other women.”

108 Although Catholic sisters and Protestant churchwomen defined their religious missions in different ways and at times competitively, both used gender ideology as an impetus and justification for expanding their influence and providing necessary social services in the American West.

The isolated and primitive conditions of the frontier, particularly during their early years there, gave sisters additional autonomy and influence. Clearly the travel and business activities of the advance teams thrust nuns into all kinds of social, legal, and economic situations. Long-distance travel by land and sea in isolated and potentially dangerous environments and interaction with secular and clerical males forced them to adapt their behavior and develop much more flexibility and spontaneity than was required by daily convent routine in established areas of the country. The CSJ Customs Book of 1868 provided very explicit direction about avoiding “unnecessary” conversation and involvement with seculars. It told sisters to avoid “levity” and interactions with laymen that were not of spiritual benefit.

109 The sisters’ journals and correspondence demonstrate that secular interaction, encompassing the federal government, local businesses and authorities, and a vast range of ethnically diverse women and men, was not only necessary but also constant and ongoing. The sisters’ conversations certainly ranged well beyond religious edification. CSJS established women’s support networks and institutions that educated the young and cared for the physically and spiritually needy. Gender ideology limited them, even as it provided a justification for their educational and nurturing roles, but their vows of poverty, obedience, and chastity may have allowed more latitude in their behavior and provided them with ways to avoid male influence and unwanted attention. Like many secular and Protestant women who traveled west, CSJS challenged and appreciated the rugged terrain of the frontier even as they fought off homesickness and fear. Its physical isolation and deprivation provided constant reminders of their mortality and their call as religious women. Present in larger numbers than male clerics, the CSJS and other women religious lived and worked daily with the people they served. Creating and/or staffing parish schools, Indian missions, private academies, colleges, hospitals, and orphanages, they expanded and shaped Catholic culture and American life throughout the trans-Mississippi West.