5

Promulgating the Faith

[F]or more than 100 years, [parochial] schools were Identified with the sisters who lived in the local convent, taught in the classrooms furnished by the parish, supervised children on the playground, and carried out additional functions within the parish. In fact, by many of the local citizens, the schools in the Catholic parish were referred to as the sisters’ schools.

-They Came to Teach

Parochial Schools and American Catholic Identity

. American sisters provided the lion’s share of the labor force, and even Catholic children who attended public schools received their religious training after school or on Saturdays from the nuns.

2 The sisters’ role in parish education was extensive. They served as teachers (for grades K-12), principals, fund donors and fund-raisers, sponsors for religious organizations, choir directors, coaches, and social workers in a hierarchical and male-dominated church that often exploited and devalued their labor and contributions. Consequently, their experiences provide an intriguing and complex portrait of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Catholic parish life that was permeated by the interactions and power struggles of class, ethnicity, and gender.

When the CSJS arrived in St. Louis in 1836, the American common school movement was in its infancy, and state-supported, tuition-free, and coeducational public schools would not become a reality for most children until later in the century. In colonial America, schools, with few exceptions, had been a privilege for elite white males.

3 After the Revolutionary War and in an attempt to live up to its egalitarian principles, Americans in the new democracy debated the importance of schooling and, specifically,

who should be educated,

what should be taught, and

how schools should be funded. Race, class, and gender provided major barriers to education for the vast majority of children well into the nineteenth century. The few schools available were either church-supported, public-supported, or some combination of the two.

4From the late 1830s until the end of the century, common schools developed in a very uneven pattern across the United States, and access to education was often determined by the state legislature’s and local community’s interest and willingness to provide funds. Although historians of education continue to debate its objectives and outcomes, the common school movement reflected concerns that were both political and ideological.

5 “It was argued that if children from a variety of religious, social-class, and ethnic backgrounds were educated in common, there would be a decline in hostility and friction among social groups” and that teaching a “common political and social ideology” would enhance national identity and unity. Schools could become instruments of government policy to educate people for democracy and ameliorate any “foreign” (antidemocratic) tendencies.

6As the Catholic population grew with the influx of German and Irish immigrants prior to the Civil War, Catholic parents wanted their children to take advantage of this new American system of “mass education.” However, for many Catholic parents and clergy the “common” school appeared to be an overtly “Protestant” school. The curriculum included the use of the King James version of the Bible, Protestant hymns and prayers, and blatant anti-Catholic statements. The term “popery” appeared throughout textbooks, and even when Protestant public school committees attempted to purge offending passages from their texts they seemed to have difficulty recognizing their own biases. For example, in one “revised” New York textbook a historical character, who was a “zealous reformer from Popery,” was killed when “trusting himself to the deceitful Catholics.”

7The battle over the public schools permeated urban politics in many Eastern states. In New York City and Philadelphia public emotions spilled over into high-profile political debates and, in some instances, riots. In 1843, four years before the CSJS came to Philadelphia, thirteen people died and a Catholic church was burned to the ground during the Philadelphia Bible Riots. Although Catholics saw themselves as loyal Americans, Protestant extremists viewed the Catholic challenge to the “Protestant” culture of the public schools as “un-American.” As Jay Dolan has stated, “Because they attacked the public school, Catholics were perceived as assaulting the basic Protestant ideology that inspired not only the school, but also the nation. Thus, to attack the school was to attack God, nation, and government.”

8In the First and Second Plenary Council meetings of American bishops in 1852 and 1866, education was actively discussed, and both councils “recommended” that “in every diocese” a school be built next to every church.

9 In actuality, bishops were divided on the issue. Some sought separate Catholic schools, others hoped to work out “state-supported Christian free schools,” both Catholic and Protestant, and a few still hoped for some compromise plan with the public schools. Even when public schools became more secularized in the late nineteenth century, controversy continued because many bishops felt that even though public schools were less “Protestant,” their secularization now made them “Godless.” Consequently, by the Third Plenary Council meeting in Baltimore in 1884 a majority of American bishops had taken a strong separatist stand. The council, in turn, “commanded” the building of a school within two years for all parishes, threatened that priests could be removed from the parish if they did not comply, and asserted that parents were “bound to send their children to the parochial schools.”

10 As some historians have noted, this landmark decision spurred “probably ... the largest project undertaken by voluntary associations in American history.” The labor and low wages of nuns subsidized the cost of schools considerably and “made feasible an otherwise financially impossible undertaking.”

11Even after the 1884 mandate and even with sisters subsidizing the schools, financial limitations made school building impossible for some parishes, and some bishops and priests continued to try “alternative” arrangements with public school educators, who often had similar financial constraints. Some of these alternative plans were modeled on a plan begun in 1873 in Poughkeepsie, New York. In the “Poughkeepsie Plan” the town board of education “rented” the Catholic school during school hours, controlled the curriculum, and paid the teachers. This arrangement allowed Catholic teachers to teach Catholic children secular subjects during the regular school hours and religion classes after school when the building returned to church control, therefore avoiding a church-state conflict.

12 The CSJS were involved in a number of compromise plans with the public schools, some of which barely lasted a few months, while others continued for years.

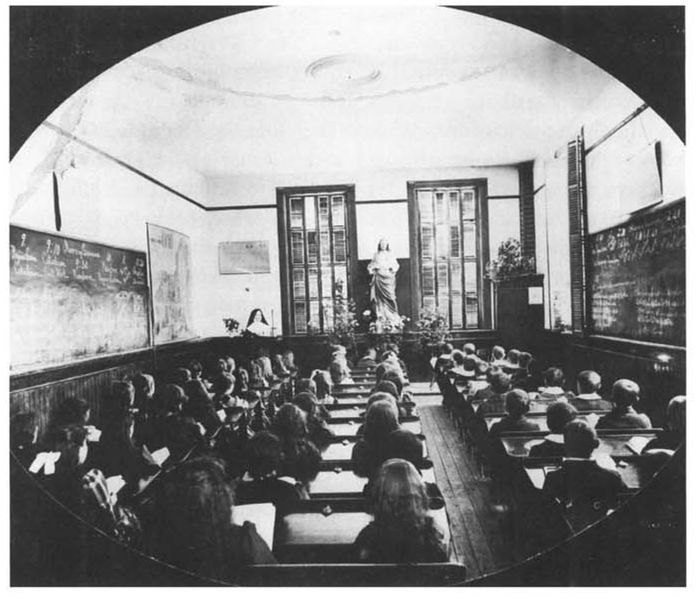

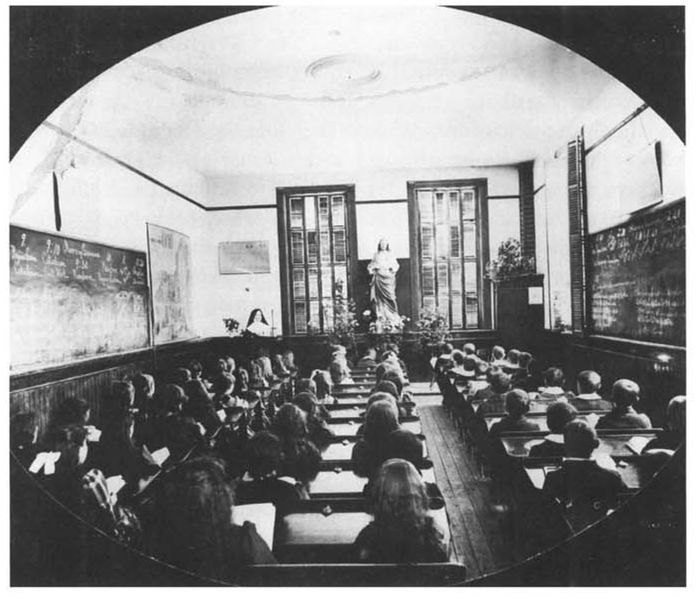

St. Vincent de Paul School, first CSJ parochial school, St. Louis, Missouri (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Archives, St. Louis province)

In 1883 sisters in Troy, New York, crossed the Hudson River in a rowboat or walked across the frozen river to teach at St. Brigid’s School in Watervliet (West Troy). By 1886, the parish had built a residence for the CSJ teachers and a new school with eight grades and an academic (secondary) department. Because the public school facilities were inadequate, the town board of education “leased” St. Brigid’s School and renamed it West Troy Union Free School. The city paid rent and maintenance costs and awarded standard teaching contracts to the CSJ teachers. The sisters were appointed under their secular names, which they used to sign legal documents and reports. By the mid-1890s this arrangement was being challenged by some local citizens who did not want the sisters teaching in a public school. At a hearing in 1897 the New York State Board of Education decided that each sister was “a duly qualified teacher” and that “no prayers or religious exercises were held during school hours” so the school board was within its rights to establish the arrangement. However, the main objection of the local citizens, that the women wore religious garb, was upheld. The CSJS could continue to teach only if they no longer wore their habits. Of course the sisters refused and they were fired at the end of the 1887 school year.

13Bishop John Ireland introduced a similar plan in 1891 in Faribault and Stillwater, Minnesota. The Dominican Sisters were teaching at Immaculate Conception school in Faribault, and the CSJS were teaching at St. Michael’s in Stillwater. In both cases the parochial schools were struggling financially, and under the new arrangement both schools acquired badly needed public funds. However, success at both sites was short-lived and within two years the Faribault-Stillwater plan was discontinued. Attacked by both Protestants and Catholics, the plan failed for many reasons, including the controversy surrounding Bishop Ireland’s “liberal” views on Americanization.

14Once again, however, the nuns’ habits seemed to be a major source of contention for Protestants. Although all religious symbols (e.g., crucifixes and religious pictures) had been removed from the schools and the sisters were deemed good teachers, the visible presence of nuns in habits seemed to undo some Protestants, who labeled the Faribault-Stillwater plan “a clever trick ... to capture the public schools for the Church of Rome.”

15 The CSJS in Stillwater were the subject of a lengthy newspaper article published in the

Minneapolis Journal on January 9, 1892. The local reporter, who visited the classrooms, provided his readers with a detailed description of the nuns’ habit. The reporter also quoted a Protestant minister who found the habits “particularly obnoxious,” and the article concluded with a cartoon of a CSJ in habit.

16Another, longer-lasting conflict involving the CSJS in the Minnesota public schools occurred at St. Mary’s in Waverly in 1893. As in Faribault and Stillwater, the plan placed nuns in a school funded by public tax dollars. Although controversy began as usual, the local citizens seemed less alarmed by the presence of teaching sisters and the arrangement with the public school continued until 1904. While sisters in some states had fewer problems than the CSJS experienced, “anti-garb laws” and negative reactions to the religious habit would continue to limit American nuns’ participation in public schools into the twentieth century.

17As the barriers between church and state increased in the 1900s, the Catholic school system continued to define itself as a separate entity. The parochial school statistics from 1880 to 1920 clearly illustrate not only the growth of the parish schools but also the financial difficulty parishes experienced in creating a Catholic school system in the United States. In 1880, six million American Catholics supported over 2,000 parochial schools with 400,000 students. By 1920, seventeen million Catholics had created approximately 6,000 schools with 1.7 million children enrolled. Although these numbers are significant and the growth rate is evident, these schools existed only in about 35 percent of Catholic parishes.

18 Fortunately for the parish schools, as the Catholic population grew so did the number of American sisters. The phenomenal increase of women religious in the United States made the growth of parochial schools possible. In 1850, fewer than 2,000 sisters lived in the United States, but by 1890 over 32,000 women had taken vows, and by 1920 the number had risen to over 90,000. One historian has estimated that between 1866 and 1917, more that 50,000 American nuns devoted their entire lives to teaching in parochial schools.

19The CSJS, like many women religious, taught in a wide variety of parochial schools throughout the United States. Between 1836 and 1920, CSJS taught in nineteen states in all regions of the country. Beginning with their first school in 1836, they had established 155 parochial schools by 1920. Over 57,000 European American, African American, Hispanic, and Native American students were enrolled .

20Besides teaching racially and ethnically diverse students, the CSJS also created schools for the education of deaf children. Beginning in 1837, with the arrival of two sisters trained in the latest French methods for teaching sign language and working with deaf students, the Carondelet CSJS created schools in St. Louis, Buffalo, and Oakland, California, and they were indirectly responsible for institutions conducted by other Sisters of St. Joseph, who traced their earliest beginnings and training methods to the St. Louis sisters. As some of the earliest trained teachers of the deaf in the United States, they taught classes for children and adults that included religious instruction, academic course work, and vocational education .

21Although CSJS taught in a wide variety of private and select schools and academies and in many of their orphanages, staffing parish schools engaged the largest number of sisters. Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Catholic school system included a diverse mix of schools that were funded by parishes, male and female religious orders, dioceses, or some combination of sources. Additional confusion was created by the variety of names used to identify these schools. Depending on the region of the country, the need of the parish, or the whim of their creators, these schools might include a mixture of elementary and secondary and sometimes postsecondary levels, and might be indiscriminately called academies, parish schools, parochial schools, high schools, institutes, and sometimes colleges. For example, in the Midwest and Western part of the country, the CSJS used the label “academy” to refer to their private or select schools, which were boarding and day schools for Catholic and Protestant young women. In reality these schools often included a mixture of young boys and girls of all ages from the parish. St. Mary’s Academy in Los Angeles provides an example of the eclectic nature of some of the early CSJ schools. In correspondence to Reverend Mother Agatha Guthrie in St. Louis, Father A. J. Meyer defined his ideas on the nature of St. Mary’s Academy: “I agree with you in calling the school an academy, for besides there being a great deal in a name, your school will be it in reality; we must also consider it a parish school, where all the girls in the parish can go, even as you so kindly mention, the poor, for we must never neglect them ... and besides we must have room for our little boys.”

22The schools in the CSJ Eastern province (Troy, New York) provided a somewhat different profile. By 1883, the Troy province no longer had private or select schools in New York, but the label “academy” or “institute” continued to be used for elementary and secondary parish schools. St. Bernard’s Academy, the parish school in Cohoes, New York, served an even broader purpose: the sisters taught night classes to accommodate children and adults who worked in the city’s factories. Sister Flavia Waldron reminisced with another CSJ about teaching a full day with parish children and then beginning night classes: “Don’t you remember the crowds of girls we had to teach at night after teaching all day? My eyes were nearly blind when we got through. Sisters Dominic and poor De Sales used to teach big young men with beards in the basement. It used to be ten o’clock before they got home. Then we had to do our washing and ironing on Saturday and take our turn to sit up with Mother Philomene every night until she died.”

23

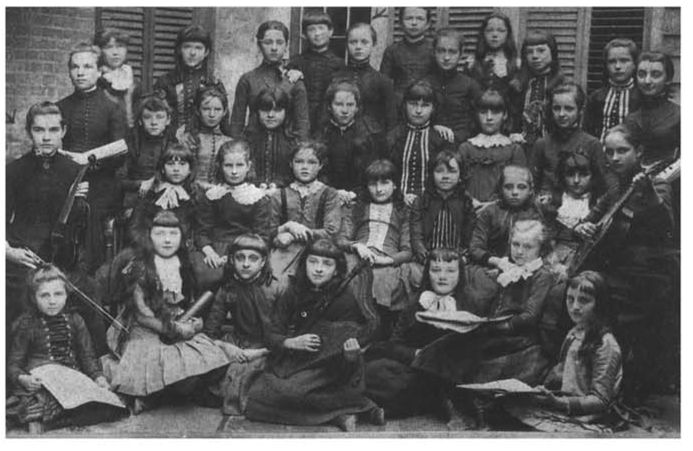

Music class at St. Peter’s School, Troy, New York, 1888 (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Archives, Albany province)

Parish schools often taught a variety of students at different skill levels, but their main purpose was to educate children, regardless of socioeconomic standing, in the tenets of the Catholic faith and provide a basic education similar to that of the public schools of the time period. Fearing the Protestant and secular influences of the public schools, Catholics wanted the parish schools to imbue children with a Catholic identity, immerse them in Catholic culture, and save their souls while educating them in the basic skills necessary to survive in American society.

As was the case in the public schools, the parish school structure and curriculum varied from school to school and could be affected by funding, geographic location, availability and expertise of teachers, parental support, and sometimes ethnicity and class. Gender segregation also reflected the availability of teachers and the variety of students to be taught. In the public schools coeducation became the accepted norm by the midnineteenth century, although sex-segregated schools lasted longer in urban centers in the East and South, where competition with private schools was most intense.

24 When it was financially feasible, most Catholic parochial schools continued the European tradition of separation of the sexes. In St. Louis, CSJS taught in St. Anthony’s parish, which had three parish schools located in two buildings—one building for elementary school boys and one building for elementary and high school girls. Boys and girls were segregated in separate schools where possible; but more likely, funding limitations required that they reside in the same building but in separate rooms or wings. Describing the physical layout of his school, a Los Angeles priest assured the new CSJ teachers that “the building is so arranged, that the little boys having their separate yard, can go to their room without ever coming in contact with any girl.”

25 However, in the primitive conditions of St. Anthony’s School in Minneapolis “one school room was closed from motives of economy, and the boys and girls were taught in the same room, and by the same teacher.”

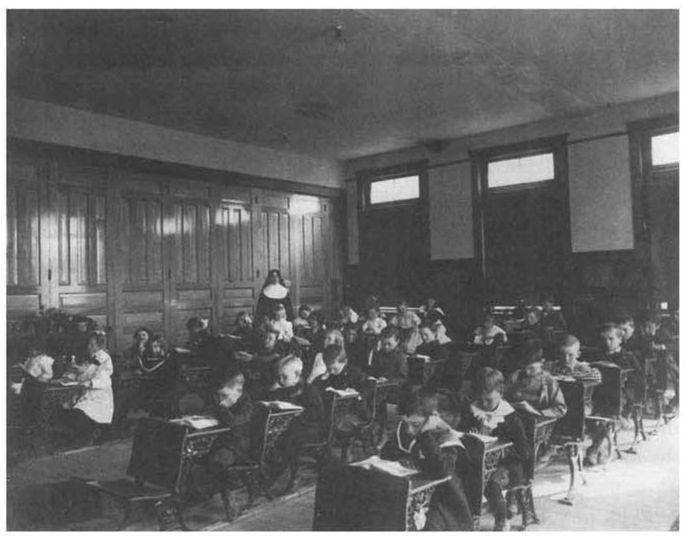

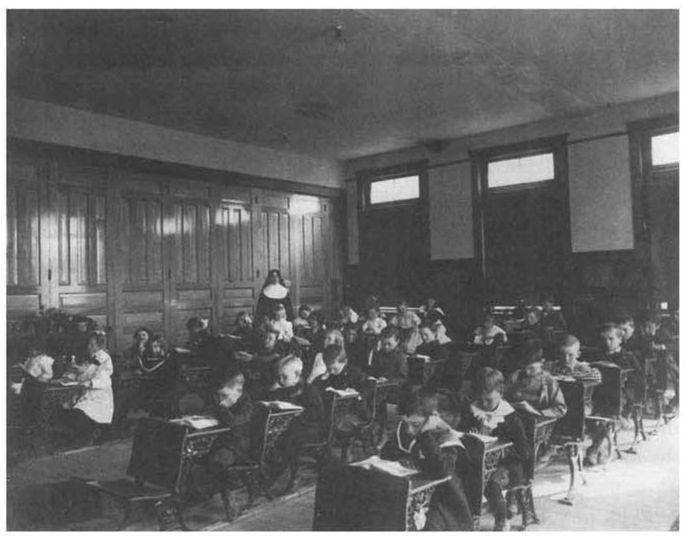

26Class size was also determined by the availability of funds and teachers. Although many nineteenth-century classrooms in cities were large, on the average Catholic schools were probably even larger than public schools. CSJS in the Troy, New York, province focused strongly on parish education. By 1920 they were teaching in twenty-three parish elementary schools and sixteen high schools in the Albany and Syracuse dioceses. They taught over 15,000 students a year; the average class size varied but ranged between thirty-seven and fifty-two students, although at times individual classes could include as many as sixty or seventy pupils. The smaller numbers were more typical of secondary classes, and the largest class sizes normally occurred in the primary grades.

27The sisters’ concern about such overcrowding was countered by the pressures of local priests and their own desires to serve the parish and provide education where it was needed. At Francis de Sales School in Denver, Father Donnelly constantly pressured the CSJ leadership for more teachers. “I recognize the wisdom of your suggestions about not overcrowding the school.... I would prefer to take only the third, fourth and fifth grade ... but I expect this will not be possible as there is so strong a demand to have the younger ones cared for by the sisters.”

28 In Oakland, Father J. B. McNally was more direct in his demands, blaming the school’s declining reputation and his poor health on the lack of CSJ teachers: “Now my Dear Mother, you are expected to fill your part of the Contract—viz. to supply teachers for the girls and all the boys up to receiving the sacraments. So far you have not done your part. I am much annoyed. I am grieved and troubled at having to provide lay teachers who give no satisfaction, who are helping to give the school a bad name (unintentionally) and all this failure at an expense that is crippling my energies.”

29The CSJS may have had little control over crowded conditions, large classes, and the constant demand for “more sisters,” but in the area of curriculum they were the experts. Before coming to the United States the CSJS had taught school for almost two centuries in France. One of the items the original sisters brought with them in 1836 was the

School Manual for the Use of the Sisters of St.Joseph.

30 In the 1840s, Sister Mary Rose Marsteller, a nativeborn Virginian, “Americanized” the French version of the manual by incorporating in it “the standard methods of her day.” She also “added a full secondary course, with mathematics, rhetoric, German, and the natural sciences of botany, physics, chemistry and astronomy.” Course work in French, vocal music, Latin, and history were retained from the earlier manual, but she added instrumental music and ornamental subjects (needlework, tapestry, etc.). In 1884, a team of teachers from all CSJ provinces worked to update and publish the first English version of the manual. In 1910, it was revised again to keep it current with changes in curriculum and teaching methodology.

31Used widely by many other religious orders who did not have specific teaching guides, the CSJ manual provided an in-depth look at the content and methods utilized by sisters teaching throughout the country. It also serves as an excellent example of the type of teaching manual written by other orders of women religious.

32 Other than the obvious inclusion of religion, the parochial school curriculum closely paralleled public school courses of study. Reading, arithmetic, grammar, history, geography, nature study, and writing formed the core of the elementary curriculum.

Although the often stilted, rote, and drill-oriented approach typical of nineteenth-century pedagogy can be found in the 1884 version of the manual, what astonishes the contemporary reader is the presence of many “modern” approaches in teaching methods. In contrast to the French version of the manual, which defined the importance of “conformity in teaching methods and disadvantages of using diverse methods,” the introduction to the 1884 American manual stressed the importance of flexibility and new ideas and discouraged uniformity of approach. “It was considered, that to restrict the teachers to particular ways of conducting the different studies, would be to close the door to future improvements, as new ideas and suggestions on these subjects are constantly appearing.... These suggestions are not intended to trammel the teacher in the exercise of a wise discretion, but are given simply as aids to those who may need them.”

33 The French version of the manual focused extensively on teacher control and the need to “inspire respectful fear” in children to “make them submissive.” Teacher control was valued in the 1884 Americanized manual, but the teaching strategies were much more child-centered and the pedagogy extended well beyond lecture and recitation. Excerpts from the American manual reflect this change in approach:

Teaching chronological tables is not teaching history.... Encouragement inspires confidence, and children, more than others, need it.... Begin each new lesson with conversation on objects or pictures illustrative of the reading lesson to awaken interest and develop an idea.... Where the text-book routine—assigning pages and hearing recitations—belongs to a past age, you must teach.... The chief object of teaching should be to elicit thought.

34Also interesting to contemporary readers is the manual’s use of the feminine pronoun. The sisters’ long tradition and centuries-old commitment to female education is obvious since all discussions and examples in reference to students used a feminine pronoun. The 1910 revision of the manual continued to use feminine pronouns even though American CSJS had been teaching boys for decades.

The CSJS also produced some of their own textbooks for use in elementary schools. Within six years of the publication of the American CSJ teaching manual in 1884, CSJ educators published two language arts and one geography/history text. The books incorporated “modern” strategies of what are currently termed “whole language” and “integrated curriculum” approaches in language arts. The authors’ intent was to “improve the difficulty we find in procuring from children written ideas.” Similar to the CSJ manual’s preference for feminine pronouns, the frequent representation of females in stories and pictures was a unique feature of these books.

35When the sisters used other textbooks, they probably ordered them from the fast-growing Catholic textbook industry. Interestingly, except for the books published for religious instruction, these publishers created schoolbooks that looked remarkably similar to those used in public schools. In his systematic analysis of nineteenth-century Catholic and public school textbooks, Timothy Walch identified three fundamental themes in both public school and Catholic school books. Both public and parochial school books stressed patriotism and the superiority of the United States over other nations, the educational value of nature, and a conservative code of social behavior. Walch’s careful analysis shows that nineteenth-century schoolbooks, Catholic or public, taught “docility, diligence, and patriotism in children.” The main difference between public and parochial texts appeared in how patriotism was taught. Both textbooks emphasized that America was “a nation of God’s chosen people.” However, Catholic texts supplemented this theme with examples of specific contributions and the importance of Catholics to the American experience—a Catholic “great men” approach to history. According to Walch, this partisan approach taught young Catholics “to render their spiritual loyalty to the Catholic Church and their temporal loyalty to the United States.” Consequently, nineteenth-century Catholic school textbooks mimicked public school textbooks in subjects and themes, but their additional emphasis on Catholic contributions clearly helped develop a Catholic identity in “Protestant” America. Likewise, the sisters’ presence as teachers of religious

and secular subjects provided a visual and constant model of how to be both Catholic

and American.

36Immigrant parents wanted the sisters to teach their children to be successful Catholics and Americans, but ethnic identity played an important role in the development of Catholic parishes and subsequently the parish school. Although communal living, religious identity, and Americanization motivated CSJS to downplay ethnicity and class in the convent, the sisters had to work within a variety of ethnic or national parishes. The ethnic parish became the vital center of Catholic life, where parishioners hoped to worship in their native tongue and recreate their “old world” social, cultural, and religious institutions, protecting or insulating them not only from anti-Catholic sentiments but also the antiforeign bigotry prevalent in nineteenth-century America. One historian asserts that one of the major reasons for the success of a separate Catholic school system was “the commitment of Catholic immigrant groups to hand on the faith according to their own cultural traditions.”

37However, within the vast pluralism of American Catholicism, different ethnic groups had varying commitments to parochial schools, and regional location as well as the size of the parish affected parents’ support of Catholic schools. Germans, with the added incentive to maintain linguistic purity, were avid supporters of parochial schools. Like their German Lutheran counterparts, they felt that if their children lost the language, they would also lose the faith.

38 In Minneapolis and Kansas City, two CSJ strongholds, more than half of all German Catholic children attended parochial schools. French Canadian and Polish immigrants also sent their children to the parish schools in large numbers. Irish parents were less motivated than German parents to build parish schools probably because their children spoke English and could more quickly integrate into the public school system. Also, Irish American children who attended public schools, particularly in large Eastern cities, often had female teachers who were daughters or granddaughters of Irish immigrants, so the ethnic connection was maintained.

39 Italian American and Mexican American parishes had the fewest parochial schools, and their children attended in very small numbers. Neither group had developed a strong parish-centered tradition, and the lack of parish schools reflected this pattern.

40 Few African American children had the opportunity to attend Catholic schools, and by 1918 only thirty-eight African American parishes had a school.

41Besides ethnicity, geographic location and the size of towns and cities affected the creation of parish schools. Children in urban areas in any region of the country attended parish schools in larger numbers than children in rural communities. Midwestern states such as Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, and Wisconsin had larger numbers of parish schools particularly compared to New England and the Southwest. There were fewer Catholics in the Deep South than in other parts of the country, but their scarcity probably encouraged more parish schools as their church-to-school ratio was often higher than in Northern dioceses. For Catholic parents in the South, parish schools provided their children with a strong Catholic identity amid an overwhelming, and at times disapproving, Protestant majority.

42The CSJS taught in all regions of the country and in urban and small-town settings where their ethnic diversity and adaptability made them highly sought-after teachers.

43 With more non-English-speaking Catholics immigrating to the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, parishes formed around ethnic groups, particularly those defined by language differences. Parishioners demanded priests and teaching sisters who had appropriate fluency to preach and teach in the church and school. Many parents of various ethnic backgrounds wanted separate parish schools not because they necessarily feared the secularization of public schools but because they wanted to maintain their linguistic and cultural traditions. This merging of American educational principles with “old world” language and culture created many parish schools that were truly bilingual and bicultural.

44 CSJS made every attempt to match sisters’ ethnicity to parish ethnicity when possible, particularly when staffing a parish school where linguistic compatibility was important. In 1851, French- and English-speaking CSJS were invited to teach in St. Paul, Minnesota, because of its large French Canadian population. A few years later, with the German population expanding, Sister Radegunda Proff was sent from St. Louis to “run the German school” at Assumption parish in St. Paul, and two other German-speaking CSJS staffed St. Boniface School in Hastings, Minnesota.

45 Beginning in the 1880s, German-speaking CSJS in St. Louis staffed what became the city’s largest parish school, St. Anthony’s. At St. Joseph’s School in Schenectady, New York, when the CSJS could not provide enough German-speaking sisters, they used a team-teaching approach: Irish-born Sister Ailbe O’Kelly learned to say prayers in German, but when it came time to teach reading in German, she traded places with another sister so she could teach spelling in English and this German-speaking sister, Honorata Steinmetz, could teach the reading class.

46Sisters Agnes Orosco and Isabel Walsh used a similar strategy in a Spanish-speaking school in Florence, Arizona. Mexican-born Orosco was fluent in Spanish and taught classes in music and religion. Walsh learned the prayers in Spanish and taught them to her English class after being tutored by Orosco in the appropriate Spanish equivalents. Sister Agnes and the other five Spanish-speaking sisters who entered the CSJ community in the 1870s played a prominent and important role in helping the CSJS staff bilingual schools in Arizona and California. However, there were never enough bilingual sisters for all the CSJ schools. At St. Augustine’s School in Tucson, Sister Serena McCarthy had to find her own solution to a language dilemma. In her classroom of 100 Spanish-speaking boys, she found a seven year old who was bilingual, and from his perch atop her desk he translated her instructions to his classmates.

47Ethnic parishes were prevalent throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the pluralism of American Catholicism and funding limitations made multi-ethnic parishes a common exception in some locations. In 1858 an eclectic group of American-, Irish-, German-, and French-born CSJS staffed the school at St. Mary’s in Oswego, New York. Initially a French priest and a French Canadian populace dominated the parish, but the growing presence of English-speaking Catholics facilitated two separate congregations that shared the same building and occupied the church at different hours on Sundays.

48In the 1880s, sisters in Waverly, Minnesota, taught children of seven different nationalities in the parish school. CSJS in the upper peninsula of Michigan taught in schools that contained a mixture of French Canadian, Italian, Irish, and German students whose fathers worked in the mining industry around Lake Superior. At St. Joseph’s School in Hancock, Michigan, classes were taught in English and, if needed, explanations or elaborations were given in French or German.

49 At St. Patrick’s parish in Mobile, Alabama, the nuns initially taught white children, but in 1894, they also staffed the Creole school in the same parish.

50 In 1904, when the CSJS came to St. Patrick’s School in Los Angeles, they adapted to a multi-ethnic parish where sermons were given in German but confessions were heard in French, Spanish, Italian, and English, as well as in German.

51 In the ethnic and muti-ethnic parish schools, the CSJS taught in a Catholic culture that took many forms, and over time, as ethnicity blurred, the American and Catholic identity remained.

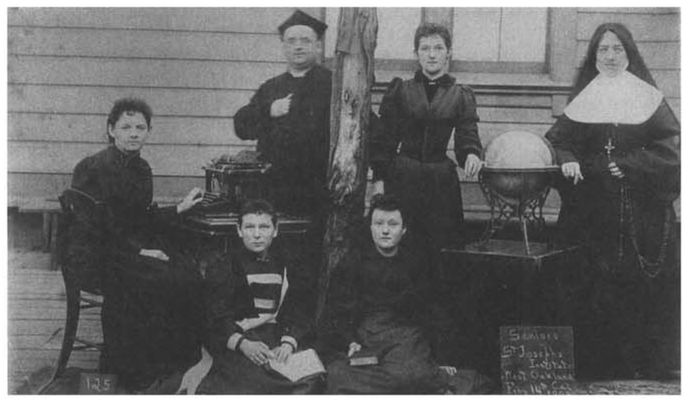

Sister Francis Joseph Ivory and her class, St. Mary’s Academy, Glens Falls, New York, circa 1900 (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Archives, Albany province)

The financing and control of parochial schools also provide an intriguing view of how class, gender, and hierarchical privilege interacted and at times clashed in shaping the newly formed school system. As new parish schools were built more sisters were called to staff them. Where parish schools had existed prior to the 1884 mandate, lay people had sometimes been the first to staff them or had shared teaching duties with nuns. This was particularly true for the CSJS in the Troy province who taught in the dioceses of Albany and Syracuse.

52 The main reason for the shift away from lay teachers to nuns was mostly economic but also a continuation of European traditions of education. Some religious orders, like the CSJS, had been teaching girls for centuries, and they came to the United States specifically to continue that tradition. Therefore, the American sisters were seen as “natural” teachers for girls and, because of the great need for teachers, young boys. More importantly, they contributed a lifelong dedication to teaching and worked for little recompense, making parish education affordable. Clearly the main reason that parochial schools survived financially was because the sisters subsidized them through their low salaries, which averaged around $200 for a ten-month period, an amount that rarely increased over decades.

53Public school teaching became a female occupation in the nineteenth century for many of the same ideological and economic reasons that sisters taught in parochial schools. Women were seen as natural teachers of young children because teaching was viewed as an extension of their maternal role in the home. As males began leaving the teaching field to pursue other job options and the number of schools rapidly increased in the nineteenth century, women, who had few job options, willingly moved in to fill the void. More importantly, male administrators and school boards saw women teachers as an economic bargain, paying them one-third to one-half the salary given to males.

54Many American nuns would have been delighted to receive this “reduced” salary since they were typically paid one-third less than what a female public school teacher earned. Caught in the double-bind of their gender and their religious ideals of poverty, charity, humility, and service, American sisters received salaries from parish schools that rarely met their basic living expenses.

55 Although male religious orders also took a vow of poverty, they received higher salaries than the sisters. Experiencing a centuries-old tradition of devaluing women’s work, European sisters had fared no better.

Underpaying and devaluing the work of sister-teachers continued in the American milieu, and as late as 1912 the practice was justified by Catholic educators, because “women could live more cheaply and consequently with a lower salary [since] the living expenses of women are not so high as those of men.”

56 At St. Mary’s, a wealthy parish in St. Paul, CSJS earned $250 per year while the parish agreed to give $450 per year for each Christian Brother and to provide an additional $200 for “outfitting, traveling and incidental expenses of the Brothers.”

57 At St. Mary’s Institute in Amsterdam, New York, the two male teachers each earned $600 for the year, the lay female teacher earned $300, and each CSJ earned $250, even though three of the six CSJS had thirteen to nineteen years of teaching experience and one of the male teachers had taught for only one year.

58The financial report of 1914 from St. Vincent’s convent in Los Angeles reflects the low compensation sisters received and indicates the ways that they supplemented their income. Twelve sisters taught over 500 children and received a combined yearly salary of $2,100. However, their expenses for the year totaled over $3,000. Using strategies similar to those of other women religious to supplement their income, the CSJS alleviated the deficit by selling books, begging for donations, and taking on private pupils. Over one-fourth of their yearly income came from teaching music lessons.

59 Sister Rose Edward Dailey, reflecting on her many years in the parish schools of St. Louis in the early twentieth century, wrote: “Our salary as teachers was twenty-five dollars a month ... [and] some of the pastors, from then flourishing parishes, took the sisters for granted and [did] not pay the sisters’ salary for years. This is hard to believe when all parishes were engaged in Social Justice and were doing intensive study of writings on [the topic].”

60 Financial records from other CSJ institutions demonstrate this pervasive practice of “taking the sisters for granted.” At St. John’s parish in Kansas City the financial accounts from 1882 to 1904 list in detail all monies paid to pastors, assistant pastors, building funds, choir directors, organists, and janitors as well as contributions sent to male colleges/seminaries, the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, “Peter’s Pence,” and the “Holy Land Fund.” Not one dollar was recorded for CSJ teacher salaries.

61In many parishes the CSJS were promised accommodations as part of their salary. Sometimes they materialized and other times not. In 1883 Father J. B. McNally wrote Mother Agatha Guthrie to thank her for agreeing to send CSJS “without any expense to me, ready, able, active, energetic, zealous and ardent” to teach in his parish school in Oakland. Then he asked her to “advance some cash for your

own benefit as well as for the sake of religion” to help him build the school and convent even though it is clear from the letter that she had already refused an earlier request for money. He wrote: “Try if you possibly can to aid me materially, as the Sisters of Notre Dame have done in a neighboring parish. I don’t plead poverty, for we have done wonders in a short time and we don’t owe anyone anything. I only fear that the strain may be felt too keenly by my faithful people.... I think that you’ll be pleased if you will send on at least $5,000 so that the building might be more grand and imposing and commodious.”

62

Senior class, St. Joseph’s Institute (St. Patrick’s School), Oakland, California, 1893 (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Archives, Los Angeles province)

Father McNally was unsuccessful, but other pastors did receive monetary assistance to finance the sisters’ housing. CSJS at St. Mary’s Academy in Hoosick Falls, New York, did share expenses in the furnishing of their convent. The financial records show that the CSJ Troy province provided a very generous share for the convent interior, spending over $2,000, compared to the parish’s $724 contribution.

63For nineteen years sisters at Ascension parish in Minneapolis waited for their convent to be built next to the school so that they would not have to endure the eighteen-block walk to and from school. Witch only their woolen shawls to protect them, they battled the fierce Minnesota winters and accompanying frostbite by walking backward or taking turns walking in front to protect the rest of the sisters from the frigid winds. The pastor refused to close the school even during blizzards. In 1916 parishioners intervened on behalf of the sisters by refusing to pledge money to help the pastor build a gymnasium for the school until the sisters had their convent.

64In the early 1900s the sisters in Oxnard, California, probably had some of the most unusual accommodations. Their convent was so small and the halls so narrow that when the portly Bishop Montgomery came to bless it, he remarked that “one has to go outdoors to turn around.” The four-room cottage had no bedroom space so two sisters slept in the bathroom, one in the small room across from the chapel, and one in the tiny kitchen. When entertaining the provincial superior, Mother Elizabeth Parrott, the sisters covered three wash tubs with boards, linens, and bouquets of flowers and served Mother Elizabeth her “first full course meal in a laundry.” The school accommodations had their own problems. Sister Liboria Wendling reminisced, “Before the new school was completed three sisters taught school in an abandoned restaurant. It was not unusual during the day to have patrons throw open the doors expecting to be served a hot meal.... The reason for the mistake was a simple explanation. No one had ever had the courage or gymnastic ability to climb atop the roof and remove the huge sign which spelled out in bold letters the single word ‘

restaurant.’ ”

65In light of their limited support from many parishes and local pastors, how did the CSJS finance their work in parish education? In addition to making ends meet through private music and art lessons, fairs and fund-raisers held in the parish, food and monetary donations from parishioners, and extremely frugal living, the CSJS used a method to earn money that they had earlier found helpful in France and one very typical of many religious orders of women. In many nineteenth-century parishes the sisters opened private, or select, secondary academies for girls that catered to wealthy families, Catholic or Protestant, who had the means to pay tuition for their daughters’ education. This select school was the “cash cow” that enabled sisters to work in parish education and receive little or no compensation. It is important to remember that these schools were often the first type of school that women religious opened when coming to a new setting, and their success often determined whether sisters could “afford” to staff schools for poor children and/or parish schools. Americans’ sensitivity to class made these schools problematic at times, but they were vital to many religious communities’ existence and financial survival.

66The CSJS in the Troy province, probably at the request of the bishop, discontinued their select schools in 1883, which forced them into low-paying parish teaching positions without the means to supplement their income. A letter from the CSJ provincial superior in Troy in 1911 that informed local parishes about the necessity for a salary increase for sisters illustrates the financial sacrifice the Troy province made when it gave up its select academies twenty-eight years earlier. Reminding the pastors of the fifty years of CSJ service in the Albany and Syracuse dioceses, she told them that “it is impossible to make ends meet ... without practicing an economy detrimental to the health and strength of our Sisters.” She continued,

Our mortality is abnormally high and as teaching is a severe drain on vitality we can only hope to counteract it by abundant nourishment. ... As a matter of record it is proper to recall that some years ago all the larger parishes had their select schools which were a source of revenue. To strengthen and develop the parochial schools and discard artificial distinctions which tended to divide members of the same [parish], these select schools were surrendered at a pecuniary sacrifice to local convents.

67Her request was actually very modest since she asked for $25 per month for elementary and $30 per month for secondary teachers—salaries that CSJS were already earning in other parts of the country and that were still significantly lower than what female public school teachers earned in 1911.

Besides struggling with limited financial support, Catholic nuns faced a problem that permeated every aspect of their work and community: the threat of patriarchal interference and control of the schools. In many CSJ settings the local pastor was the principal in name only and left the curriculum and day-to-day decisions totally in the sisters’ hands. However, if he chose to exercise his clerical privilege, the local parish priest had the authority to interfere in every aspect of decision making including scheduling, class size, numbers of students, grade levels, curriculum, sisters’ salaries and accommodations, budgets, and personnel decisions regarding individual sisters whom he favored or disfavored depending on the circumstances. In each diocese the bishop had ultimate control over all parish schools, and if the bishop and the parish priest disagreed the sisters could be caught in the middle with little recourse.

In 1909 CSJS had to battle both a parish priest and the bishop in a clash of egos and power that typified the ethnic and gender politics involved in their work. At St. Patrick’s parish in Denver, the sisters became caught in a power struggle between a popular Irish-born priest, Joseph Carrigan, and a powerful French-born bishop, Nicholas Matz. Father Carrigan wanted to build a new church at St. Patrick’s and began to do so against the express orders of Bishop Matz. The flamboyant Carrigan, who had connections at city hall, used his political influence and the Denver newspapers to make his case against the bishop. The battle raged publicly for months, and a series of letters document how the sisters were pressured by both clerics to acquiesce to their divergent demands concerning the parish school and the instruction of schoolchildren. This was humiliating for the CSJS, who hated the publicity and their constant presence in the newspapers, which they felt tarnished their hard-won reputation in Denver.

68 Gender was an important factor in this incident, not only because both men used patriarchal and hierarchical power to bully and threaten the CSJS, but also because religious communities of women had to guard their “reputation” as carefully as any individual secular woman or group of women. If the sisters’ reputation was sullied in any way, rightly or wrongly, this threatened the viability of all their institutions in Denver and their ability to recruit young women to the order.

For months both clerics sent letters and telegrams to St. Louis pressuring the Reverend Mother for the community’s unqualified support. Frustrated by what he perceived as a lack of CSJ cooperation, Father Carrigan labeled the CSJ superior in Denver “hysterical” and demanded her removal, while Bishop Matz sent veiled threats demanding obedience from the CSJS and hinting at possible repercussions for all CSJ institutions in the diocese.

69 Sister Marguerite Murphy, the superior at St. Patrick’s convent, held her ground waiting for instructions from her superiors in St. Louis. Her vow of obedience enabled her to refuse both men until her female superior, Reverend Mother Agnes Gonzaga Ryan, sent advice. Finally Ryan took matters into her own hands. She withdrew all the sisters from St. Patrick’s parish and stated that she would not let them return until the matter was settled between the men. This strategy was sometimes adopted by communities of women when “voting with their feet” seemed the only way out of an untenable situation. Ryan wrote the bishop that she was not justified “in allowing sisters to go through so much [when] there is a great scarcity of sisters” and they are needed in other places.

70 For three years, Ryan continued to refuse the bishop’s demand for their return to St. Patrick’s, using the one powerful leverage she had—withholding needed services. Some scholars have argued that historically women’s power has rested on control of “goods and services” and is expressed through the “withdrawal of their services.”

71 For women religious, the ability to control or withhold the many services they provided was key to any autonomy within the highly patriarchal Catholic Church that badly needed their labor. The nuns used their vow of obedience to their female superiors and their “Holy Rule” as leverage against male clergy. And like other women, they found that it was sometimes easier to leave a situation than continually battle with patriarchal authority.

72For American sister-teachers, and female teachers in general, the issues of autonomy, control, and professionalization became of paramount concern in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Although American women had gained a profession, they were neither able to control it nor make it their own. As large urban public schools began to centralize and move away from local political control, women teachers’ destinies were increasingly in the hands of male administrators hired by school boards. One scholar has noted that, “from the earliest days of the development of the urban school systems, women teachers were being given lessons in subservience.... These men knew exactly the kind of educational system they wanted—ordered, disciplined, with decision-making following the model of the business corporation. Thus the reformers elevated the superintendency to a position of great prestige, and spoke of the new systems of education as ‘scientific.’”

73 Some scholars have argued that this model mirrored the patriarchal family comprised of father-administrator, mother-teacher, and children-students. Calling it “scientific,” “modern,” and “efficient” was simply a way to confer new status on a very old system of male dominance and privilege.

As many states and large cities began standardizing curriculum and graduation requirements, instituting grading policies, and establishing requirements for teacher certification, Catholic educators began to make efforts to “create a complete system of Catholic training” that paralleled the public school system.

74 Under the direction of the Baltimore Council of 1884, Catholic educators hoped to create a unified system that would allow children to attend Catholic schools from elementary school through college if they so desired. Standardization, bureaucracy, male supervision, and centralization, all features of the public school system, fit well within the goals of the Catholic hierarchy and educators who strove for more uniformity and control of an ethnically divided church.

75 The archdiocese of New York selected the first diocesan school board, superintendent, and board of examiners in the 1880s, and other large dioceses soon followed its lead. Between 1904 and 1911 Catholic educators, mimicking public school educators, created a Catholic Education Association, the

Catholic Educational Review, and a department of education at Catholic University; they also established a separate Sisters’ College at Catholic University to provide education courses and degrees for nuns.

76As part of the move toward standardization and uniformity, Catholic educators called for the creation of more secondary schools. Although the majority of American children did not enroll in high schools until after 1920, earlier there was a move to provide secondary education on the East coast. By the 1880s, the CSJS in parish schools in New York began to work toward obtaining a charter for their secondary schools and helping their secondary students pass the regent’s exam, which would admit them to state-funded institutions of higher learning in New York. This accreditation required a uniformity of curriculum and a specific level of competence in core subjects; but more importantly for Catholic schools, accreditation conferred a special status on an institution since it demonstrated its competitiveness and comparability with the public schools. One year after CSJS came to teach at St. Mary’s in Amsterdam it became the first Catholic school to be chartered in the New York regent’s system.

77Although all the CSJ secondary institutions in New York became chartered over the next few decades, sisters often battled with older parish priests who resented the state intrusion. Sister Blanche Rooney, striving to achieve recognition for her school, found the leverage she needed to convince a local priest in Saratoga to allow the school to be chartered. When Sister Blanche informed the cleric that one of the daughters of a prominent man in the parish had to go to another high school to complete her exams in an “accredited” school, he finally agreed to apply for the state charter. Sister Petronilla McGowan related that the sisters often had to first convince the parish priest and then deal with the anti-Catholic bias of some of the secular examiners in Albany. The sisters worried that their students’ papers were scrutinized more carefully than others since some of the examiners showed open “hostility” toward these schools and referred to them as the “old saint schools.”

78The requirements of two school systems, public and Catholic, often presented conflicting demands for teaching orders of women religious. As nuns struggled to meet both secular and religious expectations, they were often compared unfavorably with public school teachers in regard to their training and expertise. In the period after World War I this negative comparison had merit. At that time demands for teachers to acquire more formal schooling were escalating, and public school teachers were often able to meet additional state requirements more easily than the sisters. Catholic schools usually did not require their teachers to obtain state certification, and teaching orders were under enormous and increasing pressure from bishops and local pastors to place their young nuns in classrooms, even with inadequate training. The cost of a formal college education for large groups of young sisters was also prohibitive for many congregations. As a result many young nuns entered classrooms with minimal preparation in the early and mid-twentieth century and were clearly at a disadvantage if compared to public school teachers.

However, when examining the training and expertise of female teachers prior to 1920, the comparison between sister-teachers and public school teachers provides a different picture. In fact, we would argue that sister-teachers were as skilled, if not more skilled on the average, than their public school counterparts.

79 As the urban public school system developed in the late nineteenth century, young women were needed to fill the teaching ranks of often overcrowded classrooms in the many ethnic ghettos proliferating in cities across the country. Although deemed an opportunity for women, teaching was not viewed as a high-status occupation, and many young teachers were placed in situations where they had little training and even less understanding of the immigrant children flooding urban schools. Charged with the important work of teaching American language and culture, women teachers were often treated no better than “factory hands” by an increasingly elite male administration.

80With a growing system of administrative controls and standardization, public school administrators hoped to hire young, single females who would obey without question, follow a prescribed curriculum, work for less money, and view teaching as temporary since their ultimate goal was expected to be marriage and motherhood. In reality, most women became teachers in the public schools because they needed the money, wanted meaningful work, and had few job options. If they chose to marry, most states required them to resign immediately. In 1900 the average female public school teacher was twenty-six years old or younger and worked for about five years before marriage. Only a few attended state-run normal schools, some attended summer institutes held on college campuses or took a year’s training in high school, but “most simply met the requirement to have completed a year of school beyond the grade they wished to teach.”

81 As late as 1921 only four states required a high school diploma and thirty states had no scholarship requirement at all to obtain a teaching certificate. Even in New York, a state that often was a leader in teacher training, the state commissioner of education in 1912 lamented that “the lack of preparation of teachers is one of the greatest evils of our school system.”

82Unlike their secular counterparts, sister-teachers often spent decades of their lives in teaching, gaining experience and expertise. The choice of religious life meant that their personal and professional aspirations became one, and without a family to care for they could focus on their life’s work as religious women and teachers of children. In the nineteenth century, prior to the development of professional nursing and social work, the best educated of the sisters were expected to teach and the very brightest were groomed to teach at the secondary level. Many sisters who came from European teaching orders were well-educated women who brought a strong tradition of teacher training and experience to the United States. On-the-job training and mentoring played a key role in training sister-teachers for decades. Besides using their teaching manuals, the sisters acquired ideas and expertise from others in the community, learning theory and practice simultaneously under the direction of an older member of the order.

83 Stepping into her first classroom amid disorder and chaos, Sister Mary Eustace Huster was relieved when an older, experienced nun “stayed with me for two days to give me some valuable pointers for teaching and discipline.” Later, as one of 120 sisters teaching at sixteen parochial schools and living at the Cass Avenue convent in St. Louis, Huster had extensive opportunity to work informally with other sisters who taught the same grade and who “provided a great deal of help.” Over her sixty-two years as a teacher of every elementary grade, she was able to reciprocate as a mentor for many elementary sister-teachers who came after her.

84 Reflecting on the mentoring activities of CSJ teachers and other sister-teachers in Minnesota, Sisters Annabelle Raiche and Ann Marie Biermaier write,

Oral tradition within each community has preserved stories about older, more experienced sisters who faithfully coached and encouraged younger members during their initial months and years in the classroom.... [M]entoring sessions occurred in the community rooms of convents everywhere in Minnesota.... Night after night, sisters helped one another to prepare the next day’s lessons and exchange ideas about the most effective ways of fostering the intellectual development of the students.

85Even as sisters began taking more formal classes, this tradition of on-the-job training and mentoring continued for decades. Living in large convents and sharing daily work experiences with other sister-teachers provided a constant support system that few public school teachers had. Night or day, the sister-teacher had experienced teachers close by to answer questions, give advice, or provide support.

Although the vast majority of states required little formal education of public school teachers prior to 1920, the trend toward more preparation was evident, and to enable Catholic schools to compete, women religious began to work toward increasing their formal training. Many religious communities developed “normal schools” within their novitiate programs where lay professors, experienced sister-teachers, or clergy educated the young novices in pedagogy.

86 By the late nineteenth century, CSJ provinces in St. Paul, St. Louis, and Troy developed programs to improve the education of their prospective teachers. This training varied in quantity and quality because the provincial superiors always had to choose between providing more time and training for their teachers or yielding to pressure from clergy who demanded more teachers for parish schools. As early as 1876 St. Paul CSJS had a “practice teaching school” at St. Joseph’s School, where postulants and novices did the teaching. By the early 1880s CSJS in St. Paul had created a “House of Study” for novices. Sister Winifred Hogan described a varied curriculum that included Christian doctrine, reading, rhetoric, grammar, mathematics, astronomy, physics (without lab work), elocution, music, writing, and drawing. Older sisters who specialized in each area taught the classes. Lay professors from local colleges in St. Paul and special guest speakers were hired to provide lectures to the novices and “inservice” training for sister-teachers already teaching.

87Having outside speakers and lay professors provided CSJ sister-teachers with excellent opportunities to hone their skills and receive current educational information. However, as women religious, the sisters walked a tightrope as they updated and perfected their skills without appearing to be a part of the “secular world.” In 1894 Sister Adele Hennessey used the Cass Avenue convent to hold a citywide teaching institute for sister-teachers from various orders in St. Louis. She and the CSJS were criticized by “Catholic editors and others who looked with disfavor on the experiment.”

88 This was the perennial dilemma. The teaching orders were supposed to provide an unlimited supply of superb teachers who were as good if not better than public school teachers; yet, they were also expected to minimize training to get more sisters in the classrooms faster and to avoid secular contact. They contended with a set of mutually exclusive expectations that set them up for criticism in whatever they did.

However, the CSJS consistently sought advice from public school educators, particularly if they felt it would improve their teaching strategies. The 1884 CSJ teaching manual listed helpful sources for teachers in methods and subject matter. The suggested books were from publishers not found within the Catholic publishing industry, and the most highly recommended source throughout the manual was the book

1,000 Ways of 1,000 Teachers: Being a Compilation of methods of Instruction and Discipline Practiced by Prominent Public School Teachers of the Country. Clearly, the CSJS were less afraid of secular influence than some of their Catholic critics.

89By the early twentieth century most larger teaching orders of nuns, like the CSJS, had a formal process of training that included three components: on-the-job training and mentoring, teacher preparation classes taught in the novitiate sometimes by lay educators, and college classes in secular and Catholic institutions.

90 As had happened with the nuns’ earlier attempts to obtain professional preparation, sisters received an ambivalent response from Catholic clerics when they attempted to obtain more formal college training. After criticizing the sisters both for being ill-prepared for their jobs and for taking course work at secular institutions, the hierarchy now told them that they could attend the newly created “Sisters’ College” affiliated with Catholic University, an all-male institution. The first summer institute was held in 1911, and that fall undergraduate and graduate degree programs were initiated for sister-teachers.

91 Actually, some of the sisters had already been attending college classes for years. Having been excluded from all-male Catholic colleges and with few Catholic women’s colleges available, many had taken course work on Saturdays and during the summers at nearby state universities or private colleges.

92Although finding time and opportunity to attend college classes was problematic, an even larger issue involved the costs of tuition and housing. Low-paying parish teaching did not even cover living expenses and certainly not the costs of a college education. Many CSJS in Kansas City, St. Joseph, and St. Louis attended the University of Missouri in Columbia. To minimize cost and for greater convenience, the CSJS opened Sacred Heart convent and school in Columbia in 1912 to provide housing for the many sisters who attended summer classes.

93 Sisters in the St. Paul province completed course work from the College of St. Catherine (a CSJ institution), the University of Chicago, or the University of Minnesota. In 1921, over 100 CSJS were enrolled at Moorhead State Teachers College in western Minnesota.

94Some New York CSJS attended Columbia Teachers College, and when Mother Odilia Bogan requested a higher teacher’s salary for CSJS in 1911, her rationale involved more than money for living expenses. Citing the sisters’ “competition with state schools” and having to work “under the Regents” standards that were “growing progressively more exacting and advanced,” she wrote, “To equip our teachers for these conditions we are obliged to provide exceptional training both technical and scientific at weighty expense. To illustrate: for two summers we have had four Sisters at Columbia taking courses, to be followed by the same number this summer. This year four will go to Catholic University. We have but one regret —that our limited means do not permit us to care for a larger number.”

95 Pushed by state requirements and a desire for quality teachers but limited by time and money, CSJS and other sister-teachers were in a religious, professional, and financial quandary that forced them to subsidize and improve their skills in parish schools, the very work setting that created a tremendous drain on their financial and personal resources.

When given the opportunity, sisters flocked to summer institutes, and Sisters’ College at Catholic University was successful from its inception. During its first summer in 1911, 255 sisters from twenty-three congregations in thirty-one states registered for the all-day, five-week session. Sisters of St. Joseph had the third largest attendance of any congregation.

96 Nuns who wrote about their feelings concerning the summer session probably expressed sentiments of many of the sisters who attended. One sister wrote of “how good it was to feel that we no longer stood alone and unchampioned.” Another sister thanked the college for “withdrawing its barriers” but shared her past frustration by stating, “The exigencies of the times are making such demands upon the teaching sisters as to strain their endurance to the snapping point.”

97 One has to wonder whether male academics really understood the difficulty of obtaining a college degree while teaching full time. One well-known Catholic educator told sisters, “Let it not be said that our teachers have not the time for [higher education], that they are overburdened with classes or administrative duties. The busiest teachers, it will be found generally have the most time for study and writing.... It is not a question of time or opportunity, so much as ideals and atmosphere.”

98 Obviously this academic had never spent long days in a classroom of sixty first graders while attempting to earn his degree on weekends and summers.

Some sisters completed their undergraduate degrees at Sisters’ College after accruing large numbers of credit hours at secular institutions. Anti-garb laws had often barred them from completing teaching degrees at a state colleges because the sisters could not complete the final hours of student teaching. The sisters in Minnesota were forced to quit or continue to take hours without receiving a degree because they were unable to wear their habits in a public school and were barred from student teaching in a parochial school.

99 In Wisconsin, sisters could not attend normal schools because prospective teachers had to sign an agreement to teach in the public school.

100 Since they had already accrued well over the 126 credit hours required for graduation, CSJS and other sisters receiving B.A. degrees at Sisters’ College needed only to complete a year of residence or approximately twenty credit hours to receive a degree. The list of graduates and their years of experience and past course work illustrates the dilemma for American sisters. Two CSJS, Sisters Mary Pius Neenan (St. Louis) and Mary Rosina Quillinan (Troy), were typical of the types of B.A. graduates in the first class of 1913. Both had over fourteen years experience in the classroom and had accrued hundreds of college credits before coming to Sisters’ College to receive a diploma from Catholic University.

101Although Sisters’ College helped the nuns acquire degrees and advanced education, financially it was a mixed blessing. Stretched to the maximum to send a few sister-teachers each year, communities of women religious not only paid tuition but were also asked to help finance the institution by building a separate residence for their order and paying a “ground rent sufficient to defray the expense of the upkeep of the grounds.” Desperate for the opportunity to obtain degrees and accustomed to subsidizing all manner of church institutions, twenty-five women’s communities agreed to build houses on the campus.

102The CSJS and other American sisters contributed to the workforce and financial subsidy that made the parochial schools possible in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Their work provided an important linchpin for American Catholic culture and identity for generations of children. Expanding on their European tradition of teaching, CSJS had to adapt to an American setting that required an ability to handle ethnic, linguistic, class, and gender differences while they attempted to maintain autonomy in a religious and educational setting that was moving toward more centralized authority and control. In many ways their struggles with male authority and their second-class status mirrored the difficulties of women in the public school system. However, their status as women religious, their traditional role as teachers, and the necessity of their services helped provide them with limited control in a patriarchal church and society. Nevertheless, at times they were caught between the demands of church and state and could please neither. It was in their role as educators of young women in secondary academies and colleges that they achieved more autonomy and expanded the parameters of gender in Catholic culture and American life.