6

Educating for Catholic Womanhood

Fill your minds with great things and there will be no room for trivialities. ... She who would be woman must avoid mediocrity!

—Sister Antonia McHugh

Secondary Academies and Women’s Colleges

As dean of the College of St. Catherine, the first CSJ institution of higher education in the United States, Sister Antonia McHugh personified a generation of women academics who challenged their young female students to move boldly into the mainstream of American life in the early twentieth century. The CSJS had been in America for almost seventy years when the College of St. Catherine opened its doors, and during this time they had developed a solid reputation in female secondary education, particularly through the creation and administration of their private academies. Created, staffed, and financed by many orders of women religious, academies or select schools provided some of the earliest secondary education for girls and young women in cities and towns throughout the country. These institutions also laid the foundation for the development of most Catholic women’s colleges in the early twentieth century.

Urging Americans to live up to their egalitarian principles and hoping to develop a justification for female education based on the concept of “Republican Motherhood,” both male and female educators openly discussed the need for and purpose of education for girls. The postrevolutionary debate on women’s education reflected some European ideas on the importance of women’s roles as mothers and educators of children, but it also had a decidedly American spin. Including both conservative and liberating aspects, “Republican Motherhood” argued that all citizens needed a broad education to maintain the new democracy and insure its survival for future generations. American mothers would be expected to train their sons for democratic citizenship and as future participants and leaders in the governance of the republic. This concept combined women’s “natural” role as mothers with their new “political” role as participants in a democracy.

3Another factor influenced the growth and development of female education in the United States, particularly for Protestants. The Second Great Awakening swept the country in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and the revivals and religious fervor associated with it provided further impetus for female education. Young Protestant girls and women flocked to these gatherings that often lasted days or weeks. Promoting youthful conversion and the individual’s right to choose church membership as a matter of conscience, the religious movement encouraged many Protestant women to assert their moral and religious influence beyond the home. Although the ideal of the Christian wife and mother reinforced the need for women’s education, Protestant women were also motivated to make their presence felt through social action outside the home, particularly as teachers. The western expansion of the United States and the growth of schools provided the stimulus for combining patriotic and

Christian ideals to justify the education of women as future mothers and teachers.

4Female academies and seminaries became the primary training ground for women teachers in antebellum America, and the academy continued to be the major institution of women’s higher learning until the 1870s. These academies and seminaries were located throughout the country, but most of the earliest and notable academies were located in New England. Although some of them were administered and directed by men, the list of Protestant women founders reads like a who’s who of nineteenth-century women educators and activists. Some of the more influential founders and/or leaders include Emma Willard (Troy, N.Y), Zilpha Grant (Derry, N.H., and Ipswich, Mass.), Mary Lyon (South Hadley, Mass.), and Catharine Beecher (Hartford, Conn., Cincinnati, Ohio, and Milwaukee, Wisc.). The seminaries in Troy, South Hadley, and Hartford “became prototypes for women’s institutions in the Midwest and Far West as well as the South.”

5For the CSJS and other European communities that transplanted themselves to the United States, teaching girls of all ages had been a part of their heritage for centuries, and many American-founded communities opened female academies soon after their inception.

6 Seven of the first eight orders of women religious in the United States opened a convent school for girls. The fact that so many early graduates of Catholic academies were Protestants indicates that Catholic academies for girls fit nicely into the gender ideology of the dominant Protestant culture and benefited from the cultural and social debates on improving female education. However, the convent academies also had another role. As schools operated by a religious minority, the academies also helped to preserve the faith of Catholic girls and women to help them persevere in an American Catholic culture that was marginalized and at times actively persecuted. By 1820 there were ten convent academies, and by the time the CSJS began St. Joseph’s Academy in St. Louis in 1840 there were approximately forty convent schools administered by many different orders of nuns. This number increased to over 200 by 1860, and by 1880 over 500 convent academies were scattered throughout the United States.

7Although convent academies continued to open in the twentieth century and provide a primary setting for Catholic girls’ education, by the 1880s the growth of parish, diocesan, and private high schools provided additional opportunities for secondary education.

8 With few exceptions, regardless of the setting, nuns created and/or staffed the vast majority of these schools. As a result of convent academies and the sisters’ focus on female education, Catholic girls, like their Protestant and secular counterparts, attended secondary schools in larger numbers than their male peers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

9Similar to other institution building, the proliferation of female schools —in this case academies and seminaries—was probably increased by the nineteenth-century competition and rivalry between Protestants and Catholics because it justified expanding women’s education and role for both groups. The success and growth of convent academies and schools in the first half of the nineteenth century, particularly in the Old Northwest and the trans-Mississippi West, provided added incentive for Protestant educators to increase funding for their academies and to train young women in New England academies to teach in the West. Although teacher graduates of Emma Willard’s and Zilpah Grant’s seminaries had been heading west for years, it was Catharine Beecher who founded the National Board of Popular Education (NBPE), a formal organization that sponsored Protestant seminary graduates to teach in Western schools. The religious intent was obvious. Before being sponsored by the NBPE, teacher applicants had to prove membership in an evangelical church and describe their conversion experience. Similar to a young Catholic woman’s calling to religious life and a “vocation,” these “women teachers shared one common ‘pull’ factor, their sense of mission to bring Protestant evangelical religion and education to the West.”

10Fearing Protestant proselytizing and alarmed that ethnic Catholics were sending their children to “Protestant” schools and Sunday schools, Catholic clergy clamored for sister-teachers to open convent academies and parish schools. Four years before the CSJS became the first group of sisters in St. Paul, the NBPE had sent a Baptist woman, Harriet Bishop, to open a “citizen’s school” in 1847. In a letter to the

New York Evangelist Bishop stated the importance of educating the French Canadian (Catholic) children who in her opinion were neither “American” nor “Christian.”

11 It is understandable that Bishop Joseph Cretin brought CSJS to St. Paul to offer Catholic parents an alternative to the “citizen’s” school. Clearly, battle lines were drawn and gender and religious ideology guided the fate of both Protestant and Catholic female academies, giving them added purpose and incentive.

The sisters’ success with their academies was both feared and admired by leading Protestant educators, particularly Catharine Beecher. Daughter of a well-known minister and anti-Catholic spokesman, Lyman Beecher, she spent her life attempting to create a place for women in the social, professional, and religious realm of public life. Referred to by one admirer as “a kind of lady-abbess in educational matters” she disseminated lists of Catholic academies in the West in order to frighten male clergy and others into supporting her efforts.

12 At the same time, she presented a plan to create a “Protestant parallel to the Catholic pattern,” establishing a web of interlocking social institutions of family, school, and church—with women in the central role. Beecher proposed that Protestant women be given the same “social support for their religious and moral activities as Catholic nuns received from their society.” Utilizing nineteenth-century gender stereotypes but also sounding like she could have been quoting from a convent novitiate manual, Beecher emphasized women’s need for “self-denial and self-sacrifice.” However, so as not to offend her Protestant listeners, she carefully differentiated the Catholic form of self-denial, which, in her view, was “selfish” and aimed “to save self by afflictions and losses,” from her Protestant version, which was not a means of “personal salvation” but a means to “save society.” To fund this national program Beecher again used her own interpretations of American Catholic culture —an interpretation that American nuns would have found amusing. Lamenting how self-sacrificing Protestant women had been rebuffed in their efforts to do public service, she stated, “Had these ladies turned Catholic and offered their services to extend that church, they would instantly have found bishops, priests, Jesuits ... to counsel and sustain; a strong public sentiment would have been created in their favor and abundant funds would have been laid at their feet.”

13Although there were the obvious differences of religious doctrine, the goals of most antebellum academies, Protestant or Catholic, were the same: to combine religious and gender ideology in preparing young women for life—a life that was to include religious and moral behavior and obligations, domestic and maternal responsibilities, and social and cultural influence. Course work that developed mental discipline, intellectual enjoyment, physical health, teacher preparation, and aesthetic accomplishments certainly fit well into this religious and gender paradigm.

14 Within those broad goals, however, curricula did vary from one academy to another and from one region of the country to another.

Beginning their American foundation in St. Louis may have provided CSJS with advantages and incentives to provide a broad-based and diverse academy curriculum. When the sisters opened their first convent academy in St. Louis in 1840, they had to compete with a large number of existing academies, both Protestant and Catholic, that had established reputations.

15 Nikola Baumgarten argues that although European-based sisterhoods had their own heritage and traditions as educators of young women, curricula in many academies in St. Louis “reflected the preferences of Emma Willard, Catharine Beecher, and other celebrated New England educators who tried to adapt the male course as far as possible without overstepping the boundaries of woman’s sphere.” Her analysis of the Sacred Heart Academy and other St. Louis academies documents the influence of these New England educators and their ideas on women’s education in the Midwest, particularly concerning curricular offerings.

16 To compete effectively, the CSJ academy had to reflect similar ideals.

Besides conforming to high standards on curriculum, the CSJS utilized another strategy to enhance their academy’s reputation. In the early and mid-nineteenth century, academies begun by French sisterhoods like the CSJS appealed to many wealthy parents who hoped to provide their daughters with a “proper French education.” St. Joseph’s Academy was popularly referred to as “Madame Celestine’s School.”

17 Profiting from their French heritage and hoping to compete with the nearby and highly respected Sacred Heart Academy in St. Louis, the CSJS moved quickly to upgrade the academy. American-born and highly educated, Sister Mary Rose Marsteller expanded and “Americanized” the secondary curriculum in the 1840s. As a result of her work, their first select school, St. Joseph’s Academy, offered French, Latin, German, sacred and profane history, geography, mathematics, rhetoric, botany, physics, chemistry, and astronomy, as well as a variety of music and ornamental courses.

18 This school and curriculum served as a prototype for future CSJ academies that opened later in other parts of the country. Between 1840 and 1920 the CSJS would establish secondary academies in eleven states in every region of the country, from New York to California, Minnesota to Alabama, and throughout the Midwestern states.

19When the CSJS came to a new town or city one of their first acts was to advertise their convent academy. In 1858 the sisters in Oswego, New York, advertised their “Select School for Young Ladies,” where they “will teach all the branches generally taught in the best academies.” The sisters also offered “private lessons in French, music, embroidery, painting, etc. to young ladies who may desire.” A sympathetic editor at the

Palladium Times added an additional plug for the sisters, probably meant for his Protestant readers: “The Sisters of St. Joseph are a similar order to the Sisters of Charity, but are more especially trained for teaching and are highly accomplished, both in the common and higher departments of study. Their system of instruction is thorough and complete, and pupils will make rapid progress under their efficient oversight and direction. The accommodations at the house of the Sisters are ample and convenient for study and the comfort of pupils.”

20The formal curriculum changed over time in response to educational trends and the expectations of American parents. As private, tuition-driven institutions, CSJ schools had to be responsive to what was educationally credible but also marketable to middle- and upper-class families. By midcentury, course work in “ornamentals” (i.e., painting, needlework, music), which had been standard fare in many New England academies also, was declining, and some scholars have argued that it never maintained the strong place in the academy curriculum that some historians have believed. Although the ornamental arts were clearly present in both Protestant and Catholic academy catalogs, in many instances they were electives and separate from the standard curriculum and required special fees. If parents wanted their daughters to take these courses, they often paid extra and sometimes steeper tuition rates than for the basic curriculum.

21CSJ academy catalogs support this interpretation, and although academies staffed by nuns were not all the same, the CSJS probably are representative of the larger religious communities that were active in female secondary education and had convent academies in urban centers.

22 In their earliest academies in St. Louis, St. Paul, and upstate New York, CSJS offered private lessons in music, art, needlework, etc., always for an extra fee. By 1860 in CSJ academies in both St. Louis and St. Paul, the cost of music, drawing, and painting was not only extra, but it also exceeded the cost for standard tuition and board for the entire year. This practice of separating the fine arts from the traditional curriculum and its higher fees continued in all CSJ academies through 1920.

23Another aspect of antebellum curricula that has only recently been explored concerns the existence of science courses in female academies. In her comparative study of girls’ and boys’ academies, Protestant and Catholic, historian Kim Tolley systematically analyzed academy curricula in all regions of the United States in the early nineteenth century. She concludes that while most boys’ academies emphasized a classical curriculum, particularly Latin and Greek, girls took many classes in botany, chemistry, natural philosophy (physics), natural history, and physiology. Science courses were viewed as a way to improve “mental discipline” and as a good substitute for the more prestigious “classical curriculum” prevalent at antebellum boys’ schools. Since girls were not expected to go to college and therefore did not need Greek and Latin to fulfill entrance requirements, science was substituted as appropriate course work for future “wives, mothers and teachers.” Tolley states that many Catholic girls’ academies “Americanized” by adding this science curriculum and by upgrading mathematics courses so that by the 1860s algebra and geometry were as common in girls’ academies as boys’. In essence, science courses are what sometimes took the place of the ornamental courses in the standard curriculum.

24 CSJ academies reflected this pattern since those of the late 1840s and 1850s offered courses in botany, physics, chemistry, and astronomy, and by the 1860s, courses in both algebra and geometry were available. To differentiate this course work from either a classical or ornamental curriculum, CSJ catalogs sometimes referred to their standard curriculum as the “English Scientific Course.”

25By the early twentieth century, academy course work reflected a new trend in girls’ secondary education—the move toward vocational or practical education. Commercial courses in typing, bookkeeping, and stenography as well as a renewed focus on domestic or home economic skills became a part of the secondary curriculum. American educators, concerned about the utility of a liberal arts education and convinced that education should not be the same for all students, utilized gender, race, and class stereotypes to create vocational or practical programs to supplement or replace courses in the formal secondary curriculum. Academy education diversified in response to this ongoing trend in coeducational public high schools; some CSJ institutions added vocational courses as electives, while others gave young women a choice of three tracks: college prep, commercial, or domestic. Although music and art continued to play a large role in academy curricula, the subjects were never perceived as “vocational” or “practical” but as additional options, particularly for the wealthier students who could afford the extra fees.

26CSJ academies in different parts of the country varied in their course listings, probably in response to the expertise of available faculty and the market demand within the town or city. In St. Louis, St. Joseph’s Academy offered a two-year commercial track and a four-year college prep track. Academies in Kansas City; Peoria, Illinois; Green Bay, Wisconsin; and Jamestown, North Dakota, offered commercial courses as electives, although St. Teresa’s in Kansas City also provided a two-year domestic science curriculum. Academies in Arizona and California focused on college prep courses with selected elective courses in more vocational areas. CSJS in Minneapolis/St. Paul had three academies by 1907. St. Joseph’s Academy offered three different tracks: a classical, an English scientific, and a commercial curriculum; St. Margaret’s Academy (formerly Holy Angels) offered a college prep and a commercial track; while Derham Hall limited students to college prep course work.

27Although the formal curriculum of the convent academy changed over time and responded to societal attitudes on gender, its “hidden curriculum” remained amazingly constant through 1920. The “hidden curriculum” is the term educators use to describe the attitudes, behaviors, and activities that are part of educational institutions but not part of the formal course work. Although most CSJ academies began with a mixture of boarders and day pupils of elementary school age (girls and boys) and girls of high school age, by the late nineteenth century few boys remained and some academies accepted only females who had completed “grammar school.” The mixture of boarders and day students remained in most academies, and the girls and young women, most between the ages of thirteen and nineteen, lived in an environment where the daily schedule of convent life was followed in many respects. Academy boarders spent twenty-four hours a day under the care of the nuns, and even local girls, who returned home each evening, spent most of the day within the convent milieu, experiencing the routines and life activities of the sisters. Mass, prayers, meals, uniform dress, celebrations and funerals, restricted hours, study, and recreation activities placed the girls in constant contact with nuns and convent life.

28Interaction with the sisters was particularly intense in the early years of many academies, where a mixture of sisters, boarders, day students, orphans, and sometimes “outsiders” had limited living space and mingled in most daily activities. Academy students visited the poor with the sisters, served as “English” interpreters for French-speaking sisters in some business transactions, and helped in times of emergency. For example, when a steamer was wrecked on the icy Mississippi River just below the convent and academy at Carondelet, the sisters and academy students raced to the scene with others from the village to bring “bottles of wine and good brandy, and bandages” to the 200 stranded passengers, thirty of whom were housed at the convent that evening.

29 An early student of St. Joseph’s Academy in St. Louis described spring and fall picnics, when all the sisters and students, including the students from the deaf institute at the convent, trekked into the surrounding woods. “Our most pleasant excursions were to the Red bridge crossing the Meramec River ... going as early as possible and carrying our lunches with us. Boarders, orphans, mutes, then became filled with joy and the woods were a perfect bedlam until we reached the bridge; there Grandpa and Grandma Pauponet came to greet us, and we lived like kings for that day as they gave us freedom to their garden orchard and hen nests.“

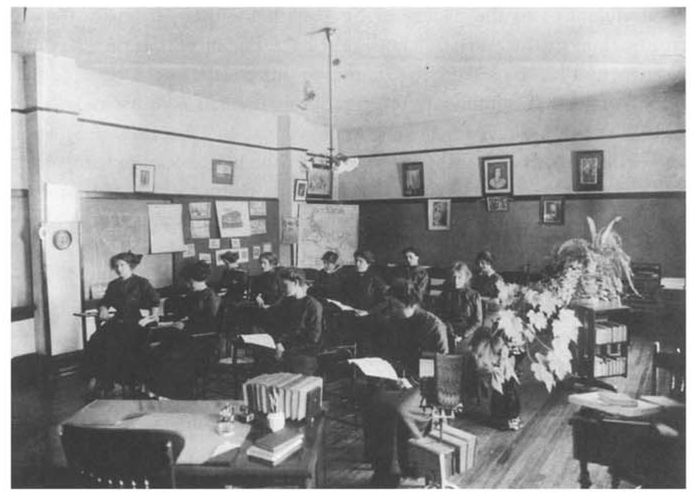

30

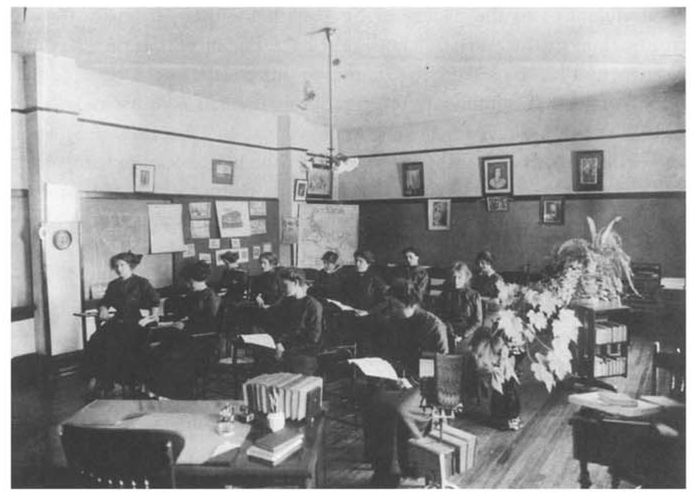

Physics class, St. Teresa’s Academy, Kansas City, Missouri, late 1880s (Courtesy of St. Teresa’s Academy Archives, Kansas City, Mo.)

The early French-born CSJS probably bonded easily with the boarders since they also experienced homesickness and loneliness. Sisters seemed to enjoy amusing the students with “horrid ghost and fairy tales” and taking part in the students’ recreation, at times forgetting piety and religious demeanor. One snowy winter two French-born sisters helped the students build a “hand sled,” although they had never seen “a sled going down a hill with no one leading it.” Sister Philomene Vilaine became so fascinated watching what she had deemed “impossible,” that one student “coaxed her to seat herself on the sled and was going to push her down the hill when [Mother Celestine] who had been watching from the upper window came on the scene and terminated our sport.”

31Later in the century well-established CSJ academies provided a more formal structure and separation between the sisters and students, but the convent environment and sisters’ influence remained. Kate Hogan, who was accompanied by her mother to the CSJ academy in St. Paul in 1876, reminisced about her first glimpse of convent life:

As we approached the stately old [building], with its round windows peering out of the gables on the roof, like the eyes of a monster, a feeling of awe came over me.... Thoughts and visions of Medieval Monasteries came to my mind, the descriptions of which I had read in story books. I dreamed of a foreign land, for I was getting farther and farther away from home, my courage was abandoning me and only that my attention was arrested by arriving at the door, I might have disappointed my mother’s expectations.

In fact, discovering the “mystery” of the nuns’ lives sometimes became a student obsession. Hogan and her friends talked constantly about the sisters’ lives; their fascination is reflected in Hogan’s description of the doorway that separated the academy from the sisters’ living quarters: “This was reserved entirely for the Sisters and no student ever crossed its sanctified threshold. Its mysteries were never fathomed and years passed without any of the girls even getting a peep into that secret cloister or knowing just what the ‘Nuns did when they were by themselves.’”

32Some girls and young women found the academy life austere, repressive, and stifling, while others thrived, emulating and admiring their favorite sisters. It is in the realm of student life and activities that convent academies were probably most distinctive from other secondary settings for girls. Based on an analysis of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century academy catalogs and student handbooks, some historians have determined that convent academies had more student supervision and regulations compared to other secondary educational settings. By the early twentieth century, even as Americans’ ideas about women’s public behavior became more flexible, Catholic secondary academies, still based on the convent model and ideal, remained more conservative than other types of schools concerning students’ vacations, correspondence, daily schedules, and extracurricular activities.

33 That a St. Paul student caused a “scandal” when her male cousin stopped to talk to her on the street during an academy outing is a reflection of this. Students at another CSJ academy realized they had breached convent propriety when, hoping to provide a special Thanksgiving drama production for the sisters, they decided to reenact the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet. With the provincial superior and professed sisters seated in the front rows, the curtain opened. Seeing “Romeo,” with a painted mustache and skirt pinned tightly to her legs to resemble pants, gazing at Juliet was “too much” for the provincial superior, who “left the hall[,] and the production was at an end.”

34Some students played pranks to break the monotony and found ways to display their displeasure with convent rigidity. Resetting clocks and disrupting convent schedules, raiding neighborhood orchards, and making ridiculous “English” retorts to French-speaking sisters added merriment to the predictability of their lives.

35 Students not only competed for academic prizes but also “vied with one another as to who could play the biggest pranks or have the most fun.” Being “smart, efficient, fearless, and daring” marked a student for “greatness” in the eyes of her peers and insured her acts would be a part of an academy tradition passed on to the next class. At times the students openly resisted when convent practices were not to their liking. Students in St. Paul, for example, returning from a school vacation, found out that their beloved music teacher had been recalled to the St. Louis motherhouse, never to return. In protest, some rebellious music pupils refused to practice and were determined “‘never to look at a piano again’ or ’take another music lesson.’”

36Although rules governing student behavior were at times restrictive and formulaic, in the area of religious tolerance and religious freedom the convent academies demonstrated remarkable flexibility and openness. From the time of the earliest convent academies in the United States, non-Catholic girls enrolled in large numbers. All denominations of Protestant girls, Jewish girls, and girls without a religious affiliation enrolled in the sisters’ schools, although the numbers diminished in the late nineteenth century when other educational institutions became available. Trying to survive among a Protestant majority and needing the money for their own subsistence, Catholic sisterhoods went to great lengths to demonstrate religious tolerance and to encourage non-Catholic enrollment. Academy prospectuses, catalogs, and advertisements boldly told the American public that religious diversity was respected and usually that the only religious requirement for non-Catholics was church attendance on Sunday. The catalog for St. Teresa’s Academy in Kansas City is typical of other CSJ catalogs. Under “Purpose” it states: “There is no interference with the religious convictions of non-Catholic students, but all, irrespective of religion are required to be present in the Chapel at Sunday services.” In Prescott, Arizona, at St. Joseph’s Academy the CSJS added an additional clause to avoid any appearance of proselytizing: “Non-Catholic pupils are not permitted to study Christian Doctrine without the written permission of parents or guardians.” The sisters in Tucson placed an advertisement in the 1881 City Directory to make their point about their academy’s religious policy. They told readers, “As an indication of the tolerant spirit and ... [to discourage] prejudice in this city, we will mention the twenty-nine children of Jewish parents” who attend the school. In Peoria, Illinois, a turn-of-thecentury Protestant writer reported to his readers that at the CSJ Academy of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, “pupils of all denominations are admitted, and except the religious instruction to the children of Catholics, all are treated alike.”

37Protestant enrollment at CSJ secondary academies was typical of many female academies taught by women religious in the nineteenth century. In some cases non-Catholic parents were lured by the reputation of the French sisterhoods; for others it may have been the only choice for secondary education for their daughters, and for others the restrictive and close supervision of students appealed to many parents who saw the convent as a “safe” environment for their daughters.

38 Indeed, it is because of Protestant enrollment and the nuns’ willingness to accept non-Catholic students that antebellum popular debate over the “Catholic plot” to convert America so many times focused on convents. Convent academies were seen as breeding grounds for such a takeover because they “captured the future mothers” of the nation. One antebellum writer warned readers that these converted Protestant daughters “will educate their children for the special service of the Pope of Rome, and their Catholic sons will become our rulers, and our nation a nation of

Roman Catholics.”

39 Regardless of the rhetoric, many non-Catholic parents sent their daughters to the sisters’ academies, and in turn, convent-educated Protestant girls were often some of the fiercest defenders of the sisters against anti-Catholic bigotry.

40In reality the sisters did have a powerful tool of conversion at their disposal—themselves. Even with the restrictions of academy/convent life, many students thrived in the environment in which they were immersed, and, in some cases, the sisters became their surrogate mothers, confidants, and role models. In many ways, what was taught at the convent academy was not that far removed from the gender and religious socialization young girls received before entering the sisters’ school. Most nineteenth-century American girls came to the academy from a white, middle-class culture already comfortable with gender-segregated activities and religious piety and practices. Living daily in a safe, supportive female atmosphere with habit-clothed religious women who practiced meaningful work outside the confines of marriage and motherhood certainly turned some Protestant girls and young women toward thoughts of conversion and possible religious life. Being present at religious celebrations, interacting with young postulants and novices, and watching some of their Catholic friends choose religious life made an impression. An academy student who watched her first “reception ceremony” provides a unique perspective on how many adolescent academy girls may have been affected by such a solemn and powerful ceremony:

When the bridal train appeared headed by the little girls out of the “E” class carrying the baskets containing the religious dress, we were all on edge, for among the group of postulants to be received were Mary Werden, Lizzie Mackey and Annie Doherty who were employed on the boarders’ side and we knew them better than the others. The singing was beautiful ... resounding throughout the chapel, as the white-robed group moved slowly up the center aisle.... [I]t could never be forgotten.

41The CSJS, like many religious orders, have some well-known converts who were exposed to convent/academy life and became a force within the community. Converts Reverend Mother Agatha Guthrie, who held the highest position in the community for thirty-two years, Sister Monica Corrigan, who was a major force in the Southwestern missions and a self-appointed archivist, and Sisters Giles Phillips and Kathla Svenson, leaders in nursing and hospital development, are notable examples of women who decided to become not only Catholics but CSJS. The story of nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century American CSJS would be very different without the presence and activities of these women.

42If some Protestant girls were tempted by conversion or religious life, certainly Catholic girls, many taught by nuns in their younger years, saw the sisters as viable role models who presented them with an acceptable alternative to traditional domesticity and a meaningful life option that was viewed by many Catholics as a “higher” life choice. Friendships and attachments to sisters and peers who chose religious life certainly influenced some young women, and the secondary academies were indeed a recruiting ground for religious vocations. Moving from an all-female academy setting to convent life proved to be a natural transition for many. Many CSJS recall friends who joined the community together and how their own attachments to sisters who taught them influenced their decision to enter the convent.

Although CSJS were successful in attracting diverse populations of girls to their schools and later to religious life, the financing of these institutions continued to provide challenges for the community, particularly in the early years. Bishops and priests initially invited the CSJS to create academies in their parishes, but the sisters soon learned that the financial support and accommodations the clergy offered were often limited and overstated. The CSJ archives are replete with stories of “misunderstandings” between clergy and the CSJS who traveled to a new mission and “promises” unkept by the clergy. In 1871, on a bitter cold day in January, a group of CSJS came to Chillicothe, Missouri, to open an academy in the recently vacated Redding Hotel. However, what the local priest, Father Abel, had not told them was that the hotel had been uncared for and recently abandoned with “bare wall and heaps of debris” on every floor. Sitting on her trunk in the “bar room” of the dilapidated hotel, the superior, Mother Herman Lacy, “gave vent to her feelings.” After working until nightfall to clear some of the debris, the sisters requested a lamp from Father Abel and were aghast when he also offered “a revolver for protection.”

43 Sisters at Hancock, Michigan, spent their first year in their “promised” convent/academy in a building whose walls had not dried before winter arrived. Sister Justine LeMay wrote that every morning the walls were covered with frost, “very nice to look at, but not so nice to feel, for when it melted, the water ran down in streams.”

44 Sister St. Barbara Reilly, who moved from the amenities of St. Louis to work in the academy in Tucson, learned quickly that candles, not gas, provided the light and eight buckets of sprinkled water “polished” the hard, dirt floor.

45Although the CSJ academies in New York were “plush” compared to those in other parts of the country, most academies survived and thrived with a mixture of funds generated from a variety of sources. Though the CSJS came to create academies at the request and often pleading of the clergy, clerical support varied widely and often diminished once the sisters arrived. For example, Father Bernard Donnelly in Kansas City had a three-story, brick building waiting for the CSJS when they arrived in 1866, but he did not have the means to continue financial support. Once classes began that fall, funding and financial obligations became the sisters’ responsibility and they began supplementing their income as they had in other towns by selling scapulars, dead habits, raffle tickets, books, scrap iron, old bottles, old rags, embroidery, and needlework.

46 By the late nineteenth century most CSJ academies were financially secure, but the nuns were always scrambling to supplement their successful academies’ incomes to help finance other, poorer institutions like the parish schools. Typical of other CSJ academies, financial records from Our Lady of Peace Academy in San Diego recorded income generated through loans (many from women), donations, fairs, tuition, board, and private lessons in art and music.

47Art and music lessons continued to be major sources of income for the sisters, and large urban academies in all parts of the country offered extensive course work in both areas. “Conservatories of art and music” were usually housed within larger CSJ academies in St. Louis, Troy, and Los Angeles, but the St. Paul province took a different approach. In 1884 they opened a separate facility strictly for the visual and performing arts. Taking advantage of a national trend in the late nineteenth century to bring “the arts to American cities,” Sister Celestine Howard conceived of the idea of founding a conservatory whose profits would help fund other financially struggling CSJ institutions. St. Agatha’s Conservatory in St. Paul became the first arts school in Minnesota, offering children, adolescents, and adults the opportunity to take a wide variety of course work in art, music, drama, and dance.

48 Sister-teachers of the arts were trained in major American universities, and a few were trained in studios, galleries, and conservatories in Europe. National and international artists performed and sometimes served as adjunct teachers at the conservatory, which became a stopping point for artists touring the Midwest. St. Agatha’s Conservatory achieved public recognition and provided large financial dividends for the St. Paul province. By the early 1920s, the conservatory was not only debt free but often generating $1,000 a day in revenue

49CSJS also resorted to a traditional method of fund-raising used by many European religious communities—begging. Some American-born sisters abhorred the humiliating task, but many probably took a philosophical approach similar to that of Pennsylvania-born Sister Francis Joseph Ivory: After being “introduced” to “begging in the markets,” she found it distasteful but stated, “[I]t seems you can get used to anything.”

50 In the Rocky Mountain states and the Southwest, railroad camps, mining camps, and military posts were targeted because they had large concentrations of men who had regular payroll schedules. The sisters arrived on payday before the men’s paychecks could be used for “entertainment purposes.” Although the sisters appealed to the men’s benevolence, the miners and railroad workers were also reminded of how they benefited from the sisters’ hospitals and their children benefited from the sisters’ schools. Sister Monica Corrigan, who made many “begging trips” throughout Arizona, had a particular flair for this activity, and stories of her exploits—including crawling into mine shafts and boarding railroad cars, soliciting from car to car on a moving train—abound.

51Another CSJ method of generating revenue was more indirect but demonstrated the sisters’ understanding of the American entrepreneurial and competitive spirit. Since the academies were so dependent upon tuition and board for their survival, it was not unusual for CSJS and other women religious to make recruiting trips to adjoining states looking for prospective students. Academies in the Midwest often attracted boarders from many neighboring states, and just as they had made recruiting trips to Ireland and Mexico to secure new members, CSJS sent groups of sisters to recruit students for their academies.

52 Newspapers advertised when the sisters would arrive and where interested parents could contact them. Although these trips were beneficial for the academies, the sisters had to deal not only with stiff competition from other religious orders but also with gender and hierarchical politics. Whether on begging trips or recruiting trips, sisters had to receive “written permission” from the local bishop to solicit or recruit in his diocese. A letter from Bishop Matz to General Superior Agnes Gonzaga Ryan illustrates the obstacles the sisters faced. Chastising her for allowing CSJS to recruit in Colorado Springs without his permission, Matz told her to “withdraw these sisters immediately” because he did “not approve of Sisters leaving their convents to canvass for pupils in this manner.” The bishop went on:

However, the chief cause for objection in this case lies in the fact that the Sisters secured rooms in the Antler’s Hotel and advertised this fact extensively in the press. This course of action caused adverse comment and reasonably so, since there are in the locality four houses of Sisters and many respectable Catholic families in which the Sisters could have received hospitality.... [T]he sisters failed to call on the local pastor of Colorado Springs, they were noticed in public parties sightseeing and spent evenings on the public veranda of the hotel.

53When it came to financing private academies and conservatories, the sisters knew that there would be little or no financial support from parish or diocesan coffers. But this had one advantage: although CSJS had to survive on their own, they struggled less with patriarchal control than sisters in parish, health care, or social service institutions who had to deal more directly with the whims of parishioners, local pastors, bishops, and male boards. However, owning and controlling an institution was not easy for any women in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century America. Married women had few if any property rights, and single women had difficulty securing loans and transacting business in the male world of bankers and attorneys. Protestant bankers had even less desire to deal with foreign-born nuns who needed loans to create Catholic academies. In these circumstances the early sisters relied heavily on male clergy to handle legal matters, which often meant that CSJ properties were deeded in the names of individual sisters, local pastors, or bishops. This ambiguity regarding ownership invariably caused problems, and the archives of women religious are replete with “horror stories” of properties lost and devastating financial losses and injustices.

54 Women religious were perennially caught in a bind of trying to survive financially and to control their institutions while attempting to live their ideals of poverty, obedience, humility, and charity. Since gender socialization reinforced religious ideals of self-sacrifice, self-effacement, and submissiveness for women, American capitalism and entrenched patriarchal authority made the sisters easy targets for exploitation, unfair treatment, and criticism.

Even with a deed in hand, women religious were still subject to patriarchal control and pressure, particularly if it came from a bishop. St. Teresa’s Academy in Kansas City provides an example of the vulnerability faced by many communities of sisters.

55 The academy property was deeded to the CSJS in 1867. In 1907, when the CSJS decided to sell it and acquire a larger space in the fast-growing southern portion of Kansas City, Bishop John Hogan intervened and flatly stated they could not sell because the property belonged to the diocese. Frustrated and clearly angry, the superior general in St. Louis, Agnes Gonzaga Ryan, argued with the bishop, but to no avail. She wrote the superior at St. Teresa‘s, Sister Evelyn O’Neill, lamenting, “There is no use! You might just as well give up the idea of a new building and a new site. I’ll never go near him again.” However, Ryan did give O‘Neill permission to talk to the bishop and encourage him to acquiesce by offering to buy him a building to use as a girls’ school for the parish. The bishop still refused, maintaining that the academy belonged to the diocese, not the CSJS. Apparently, although the sisters had a legal deed to the property, a second deed, written nineteen years later, gave them permission to sell the property only with the bishop’s permission. Undaunted, O’Neill wrote the bishop a letter “placing before him frankly the facts as I saw them”:

1. According to land prices in 1866, the entire St. Teresa’s block was worth $50 when given to the CSJS.

2. The first convent was crude, having been built by unskilled laborers and could not have cost very much.

3. The CSJS met all expense of grading and paving the streets around the block. This included areas around the Cathedral.

4. The CSJS paid all the general and special taxes on the academy for 40 years.

5. The CSJS, with no help from the Cathedral parish, maintained the parish girls’ school for 40 years.

6. The CSJS paid half the cost of the parish boys’ school.

7. The CSJS kept high standards for St. Teresa’s and had ungrudgingly provided untiring efforts for 40 years.

8. The CSJS had added to the original building, put a stone coping around the grounds and had paid for all repairs and upkeep for 40 years.

9. Only now, because of keen injustice, have the CSJS expressed any mercenary nature.

Bishop Hogan responded with a letter indicating that he would release the deed if the CSJS would indeed purchase a replacement building in the “location of his choice.” Aghast that he still required more from them but determined to act quickly, Mother Evelyn set out to find a replacement building before he could change his mind. Recalling the incident years later, she said, “Even now it seems unfair. We had saved the Cathedral Parish during those forty years far more than anything that had been given us.”

56 In hindsight, the CSJS had a “legal” right to the property, but in 1907 it would have been unthinkable for a nun to challenge a bishop in court—such was the power of gender and religious hierarchy.

Even with all the financial difficulties and the debates on the appropriate education for young women, CSJ secondary academies thrived, educating thousands of young women and influencing American Catholic culture and public life. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the CSJS moved further into women’s education by creating opportunities for higher education. For the majority of Catholic sisterhoods, secondary academies played a significant role in the creation of women’s colleges since most of the Catholic women’s colleges that opened prior to 1920 began as an extension of secondary academies.

57Throughout the nineteenth century, the debate over women’s education continued, although it changed over time. The development of the common school provided basic, coeducational education for young girls, and Catholic parochial schools, although often sex-segregated, provided similar educational opportunities for young females. By the late nineteenth century, adolescent girls were attending secondary institutions, public and parochial, in larger numbers than males.

58 However, even as more women began attending colleges after 1870 the debates over the appropriateness of higher education for American women continued well into the twentieth century.

In the 1870s, one of five college students was female, and by 1920, 47 percent of all college students were women.

59 These numbers were a result of the hard-won battle fought among American educators, physicians, theologians, social scientists, politicians, feminists, and the general public. Issues involving women’s nature, women’s place, biological determinism, psychological gender differences, divine or natural law, race suicide, and public morality all contributed to the discussions. Middle-class and wealthy Americans of various religious persuasions entered into the fray, and although Catholic colleges for women developed later than other women’s colleges, coeducational institutions, and Catholic men’s colleges, the gender aspects of the debate were strikingly similar.

From 1870 to 1900 opponents of higher education for women focused on biological and sometimes theological arguments. They viewed female education as a direct challenge to the traditional place of women in American society and in the patriarchal, Judeo-Christian family. Even in polite circles, the womb took center stage. A group of physicians and psychologists writing between 1871 and 1904 warned of the dire physical consequences awaiting women who attended colleges, particularly coeducational institutions. Former Harvard professor Dr. Edward Clarke labeled women’s higher education as “a crime before God and humanity” and so damaging to the “female apparatus” that American males would have to “import European women to be mothers of the race.”

60 Charles Darwin concluded that motherhood disadvantaged females and that through natural selection they gradually fell behind the male.

61 The medical and psychiatric establishment published “scientific data” proving that women had smaller brains, so mental and physical breakdown was assured. According to psychologist G. Stanley Hall, women were subject to “over-brain work.” The “womb doctors” claimed that the uterus was a great power that dominated a women’s mental and physical life, resulting in a weak, submissive, and generally inferior person.

62By the early 1900s coeducation had become the norm in collegiate settings, particularly in the Midwest and West, where public institutions welcomed women students whose tuition helped keep the colleges solvent.

63 Contrary to decades of dire predictions, women, who now constituted almost 40 percent of the college student body, maintained good health as well as scholastic parity and in some cases superiority to males. Male college administrators and faculty fearful of the “feminization of academia” began worrying about having “too many women” on campus and the resulting “unfair advantage” to males.

64 Consequently, the biological doom argument was replaced with cultural and theological warnings that women in higher education resulted in “mannish” females, “effeminate” men, flirtations, promiscuity, early marriages, lack of marriages, dissatisfied wives and mothers, assertive females, emasculated males and/or sexually uncontrollable males, and other potential violations of “divine law.” Although most of these sometimes contradictory fears coalesced around gender ideology, “race suicide” was also predicted, since college-educated white women not only married less frequently but had fewer children as well. This argument was not only taken seriously by many but also had the support of President Theodore Roosevelt, who publicly attacked the birth control movement and “selfish women.”

65As a result of decades of debate and the increasing enrollment of women in higher education, American colleges and universities provided diverse solutions to what one educator at Catholic University labeled “a rather difficult problem.”

66 By the early decades of the twentieth century American higher education consisted of a mixture of public and private institutions that included single-sex colleges, coordinate colleges (e.g., Radcliff and Harvard), coeducational colleges with gender-segregated curricula, and coeducational institutions with identical curricula.

67 Although the Catholic Church strongly espoused single-sex institutions taught by male and female religious, just as it did for younger students, the burgeoning Catholic middle class still wrestled with the feasibility of higher education for women and how it affected women’s traditional role of wife and mother in the Catholic home. Although placed within Catholic theological and social discourse, the debates about women’s higher education were similar to those taking place in the larger public domain and included liberal and conservative factions, with Catholic hierarchy found on both sides of the issue. Even though the vast majority of the clergy and laity tended to be conservative on this issue, proponents of women’s higher education did have some outspoken advocates in the hierarchy.

68Regardless of the volley of rhetoric within Catholic circles, by the mid- 1890s, three factors forced open the door to the creation of Catholic women’s colleges. First, Catholic laywomen were already attending college in state or secular institutions, which was deemed a threat to the faith and found unacceptable by many conservative clerics and laity. Second, nuns, who were increasingly required to obtain college course work and degrees to meet professional state accreditation in education, also were attending secular institutions. Third, no existing Catholic college or university admitted women, except in small numbers for summer or off-campus sessions. In 1895, when Catholic University opened the college to laymen but continued to bar laywomen and nuns, the sisterhoods, with the help of supportive bishops, began to take matters into their own hands.

69When the College of Notre Dame of Maryland began offering the first four-year program for women, graduating its first class in 1899, other sisterhoods followed. Aided by a small but powerful group of bishops and male clergy, the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur opened Trinity College in 1900. Unlike most other Catholic women’s colleges, Trinity did not evolve from a sisters’ secondary academy. Modeling its curriculum and structure after some “Seven Sister” colleges (e.g., Vassar, Wellesley), the nuns created it to function as a “coordinate college” to Catholic University in Washington. Terrified of having women students within a half a mile of Catholic University, the conservative Catholic press “charged that women students would present a danger to the university men” and might have the audacity “to apply to the university’s graduate school.”

70 Desperate to provide formal college training for their sisters and motivated to continue their legacy of education for Catholic girls and women, sister-sponsored colleges expanded rapidly in the early twentieth century. Although the quality of the institutions varied widely, by 1918 fourteen women’s colleges were listed as accredited by the Catholic Education Association, and almost all were located in the East and Midwest.

71Although the history of Catholic women’s colleges occurs mostly after 1920, the first two decades of the twentieth century laid the foundation for many colleges that would follow. Attempting to create viable institutions for a sometimes skeptical and reluctant clergy and laity, these early colleges (pre-1920) struggled to secure funding, students, academic credibility, support of clergy, and trained faculty. The first CSJ institution of higher education, the College of St. Catherine, provides a representative example of an early sisters’ college that dealt successfully with these problems and established itself as a premier women’s college in the Midwest.

72After decades of hope, planning, and struggle, the College of St. Catherine—the first Catholic women’s college in Minnesota—opened its doors to seven students in St. Paul in 1905. The creation of the college was to be the crowning achievement for the Northern CSJ province, which had established the first Catholic parochial school and secondary academy for girls in Minnesota in the 1850s. Critical to this endeavor was the Ireland family. Discussions about a women’s college began a few years after Sister Seraphine Ireland became a CSJ provincial superior in 1882. She was joined in her educational goals and endeavors by her first cousin, Sister Celestine Howard, and later by a younger sister, Sister St. John. When older brother John became the bishop of St. Paul in 1884, this foursome “was nowhere more bold and successful in realizing its ambitions than in the advancement of Catholic education in general and women’s education in particular.”

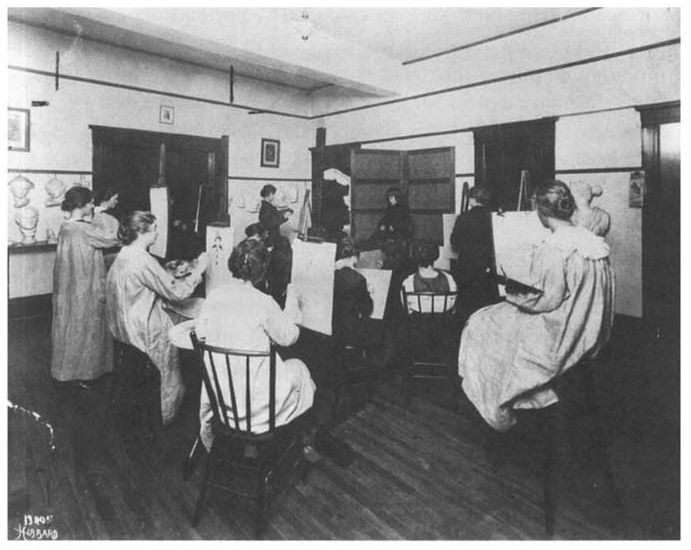

73

Latin class at the College of St. Catherine, circa 1912 (Courtesy of the College of St. Catherine Archives, St. Paul, Minn.)

Bishop Ireland, along with Bishop John Lancaster Spalding, was a prominent proponent of Catholic women’s education at the national level. Touting that he was “a firm believer in the higher education of women,” Ireland drew the ire of conservatives but continued to push for a CSJ college in his diocese: “I covet for the daughters of the people ... the opportunities of receiving under the protective hand of religion the fullest intellectual equipment of which woman is capable. In this regard I offer my congratulations to the Sisters of St. Joseph for their promise soon to endow the Northwest with a college for the higher education of young women; and I take pleasure in pointing to this college as the chief contribution of their community to religion during the half century to come.”

74 Ireland’s clout propelled the CSJS into the educational forefront in St. Paul, and unlike many other bishops who resisted higher education for women and the efforts of women religious to create women’s colleges, he constantly encouraged the endeavor. With Mother Seraphine’s vision, Sister Celestine’s financial acumen and Bishop Ireland’s financial, social, and political networks, the college became a reality.

75Hoping to use their successful secondary academies as a springboard for student recruitment, the CSJS began formulating the plans for the college in the late 1880s. An editorial in the

Northwest Chronicle in 1891 described the proposed college, and the author’s comments clearly demonstrate familiarity with the ongoing debates concerning women’s higher education. Lamenting the “past narrow sphere of woman,” the writer asserted,

[T]he education of the future must be as broad as the wide field opened up to the gentler sex. We are not here discussing the physiological questions regarding the underdeveloped and therefore uncomplicated state of the average woman’s brain as compared with man’s; we [do] accept the fact that the world thought fit to throw open to women almost every field of industry and intellect and therefore, Catholic women should be prepared to take part in this new and enlarged sphere.... There may be misdirected or one-sided education; there is no such thing as too much education.

76St. Catherine’s, which promised a curriculum that “will comprise all the branches that are usually taught in colleges for boys,” pledged to “secure the aid of outsiders who are specialists” in various curricular areas.

77 Unfortunately, a national economic recession, hitting particularly hard the Midwestern farm belt, placed the CSJS’ future college and their academies in financial peril for over a decade. Resorting to traditional fund-raising techniques, the St. Paul CSJS peddled copies of the

Catholic Home Calendar to raise funds and begged for donations. Similar to many early women’s colleges in the East and some coeducational institutions, the projected CSJ college needed private endowments to provide support and financing.

78 Bishop Ireland signed over rights to his book of essays

The Church and Modern Society, and the sisters hit the streets again, peddling it door-to-door, eventually selling 20,000 books and garnering $60,000 in royalties. Encouraged by Bishop Ireland, Hugh Derham, a local wheat farmer, donated another $20,000. The first building on campus, Derham Hall, was named after him.

79From the beginning the sisters aspired to create a high-quality institution. In addition to their vigilance and hard work in fund-raising, in 1903, in a highly unusual move for Catholic sisterhoods, the CSJS sent two sisters to tour European institutions of higher learning for women. On this fact-finding mission, Sister Hyacinth Werden, traveling with Sister Bridget Bohan, kept a diary and extensive notes about their travels, which also included stops at art galleries, museums, music halls, and other tourist attractions. Their favorite European institution, St. Ann Stift, the Catholic sisters college of Munster in Westphalia, Germany, became a model for St. Catherine’s.

80Although the doors opened in 1905, St. Catherine’s functioned only as a junior college, since early students either ended their education in one or two years or completed it at the University of Minnesota. Sisters not only struggled with financing but worked hard to attract students, sending pairs of sisters as far away as Montana to recruit. These activities directly challenge the stereotype of the demure, passive, and “otherworldly” nun. Knowing they were in a competitive and difficult economic market and understanding that they had to “sell” a women’s college to conservative, middle-class Catholics, they ran advertisements in local secular and Catholic newspapers. This personal recruiting not only was the most effective advertisement; it also placed sisters squarely in the public arena:

They went to and from the coast on the Northern Pacific and Great Northern railways on passes granted by the railroads on the assumption students would come back as paying fare. Each pair of sisters carried fifty dollars in cash to cover six weeks’ travel expenses. They stopped in a fair-sized town along the way, staying without cost in convents or hospitals and in the homes of students or alumnae. They visited the homes of those who had inquired about the college or who were known as prospective recruits by students or alumnae from the town.

81Additionally, when coming to a new town, sister-recruiters would go to the local priest and acquire the names of adolescent girls in the parish. Margaret Shelly described how Sister Bridget Bohan arrived to talk with her father on the family porch in 1909 and the next thing she knew, “I was routed out to St. Catherine’s.”

82Through the sisters’ extensive recruiting efforts, in 1911 the college had nineteen students, and when two students returned for their junior year, St. Catherine’s finally had its first graduating class in 1913. In 1914 Sister Antonia McHugh was appointed the first dean of the college, and her energy and drive pushed the school into a more competitive arena. Educated at the University of Chicago with an M.A. in philosophy, she began moving the college from obscurity to recognition as a high-quality liberal arts college for women. McHugh’s attendance at Chicago during the first decade of the twentieth century exposed her to preeminent women faculty in a variety of curricular areas. Historian Karen Kennelly credits the high-powered, academic atmosphere at the University of Chicago for much of McHugh’s belief that “women could accomplish great things, and that college for women could and ought to be a gathering of scholars, great men and women, so wholeheartedly dedicated to the spread of knowledge that they drew students into a mutual striving for learning.”

83After her appointment as dean, McHugh began to change St. Catherine’s curriculum to emulate the University of Chicago’s curricular offerings. Although Chicago was a coeducational institution and beginning to struggle with whether to have an identical or gender-segregated curriculum, she definitely moved St. Catherine’s toward a “male curriculum.” Upgrading work in mathematics, history, English, and French, McHugh made drastic revisions in the sciences by strengthening courses in chemistry, botany, and geology, while downplaying physiology, hygiene, and other gender-specific curricula offered at other women’s colleges.

84Together with solidifying the curriculum, McHugh pushed for more sisters to receive graduate degrees. She and a few other sisters in the early years of the college already held advanced degrees, and by 1920 thirteen CSJ faculty had completed M.A. degrees from the University of Minnesota, Columbia University, and the University of Chicago. This trend continued in the 1920s with sisters studying in Europe and completing the Ph.D. in some fields. The college lay faculty held M.A.’s and Ph.D.’s from European universities, the University of Minnesota, and Northwestern, Chicago, and Columbia Universities.

85 Because of McHugh’s networks at Chicago and Minnesota, the enhanced curriculum, and the faculty’s advanced degrees, national accrediting agencies began to recognize the college. Between 1916 and 1920 the College of St. Catherine was accredited by the North Central Association, the National Education Association, the National Catholic Educational Association, and the Association of American Colleges. By 1920 its 218 students, from nine states, Canada, and France, also were made eligible for membership in the American Association of University Women.

86 Never one to miss a public relations coup, Sister Antonia’s recruiting brochures now touted the College of St. Catherine as “the only college for women in the Northwest belonging to the North Central Association, which places it educationally on a par with Vassar, Wellesley, and Smith.”

87 Although the message was more rhetoric than reality, the intent was clear. This CSJ college not only wanted to provide opportunities to Catholic women, it wanted to compete in the larger public realm of American academic life.

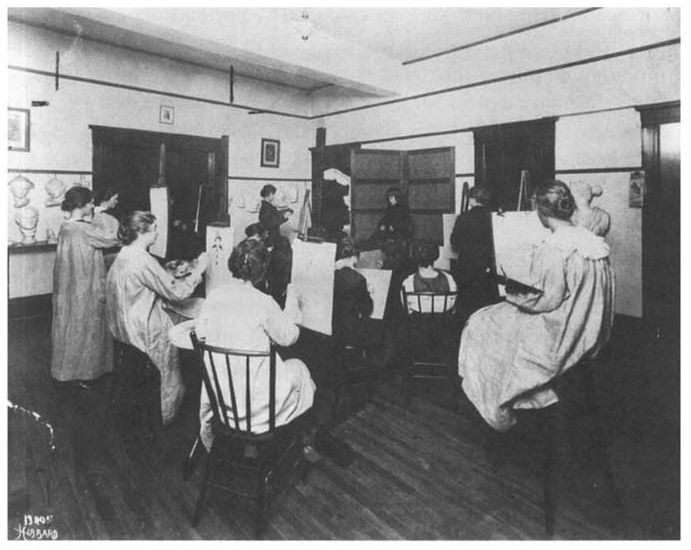

Art class at the College of St. Catherine, circa 1915 (Courtesy of the College of St. Catherine Archives, St. Paul, Minn.)

Besides the College of St. Catherine, two other CSJ institutions had begun by 1920. In Kansas City, Sister Evelyn O’Neill pushed to begin college courses at St. Teresa’s Academy, and in 1916 the junior college was established. From the beginning St. Teresa’s Junior College was established as an extension of the secondary academy course work, and it would be decades before this institution became a four-year college. In the fall of 1920 the sisters in the New York (Troy) province opened the College of St. Rose in Albany, New York. Encouraged by Bishop Edmund Gibbons, who hoped to “free our young women ... from the necessity of going far from home to pursue their studies in a Catholic college,” Sister Blanche Rooney formulated plans for the new college.

88 Within the next five years CSJ colleges began in St. Louis (Fontbonne College) and Los Angeles (Mt. St. Mary’s College). By 1925 the CSJS had created four colleges and one junior college in four different regions of the country.

89Although these five colleges had somewhat different goals, purposes, and levels of support, CSJ institutions and other colleges begun by women religious had some common aspects. Most colleges begun by nuns placed a severe strain on community finances. As had been true of their private secondary academies, women religious had to finance almost the entire cost of creating and maintaining these institutions. Eventually the colleges became sites to train young sisters inexpensively, particularly for the parochial school system, but the training was never fast enough to meet the demands and pressures from parish clergy. Some clergy resented these colleges and felt that they took money, energy, and the best teachers away from the parish schools. Accusing the sisters of selfishness and wasted energy, other clergy felt higher education was unnecessary, was wasted on females, and overprepared the nuns for parish school teaching. Like some male public school administrators, some clergy preferred young, inexperienced, and compliant sisters to staff their schools. Time taken for professional development was time away from serving parish children. Additionally, to staff their secondary academies and colleges most sisters had to complete graduate work at secular colleges, an expense that strained community coffers. Although only the brightest of the sisters were groomed for college faculty, the CSJS spent years and thousands of dollars to prepare sisters adequately. It was a huge investment made on each prospective faculty member.

Lastly, the sisters’ move into higher education often challenged their convent training and religious ideals. Taught to be humble and self-effacing and to avoid singularity, sisters had to compromise if not reject these values to complete M.A.’s and Ph.D.’s in secular institutions that challenged them to compete, excel, and strive for individual awards and accomplishments. Ironically, just at the time that CSJS discontinued their classist distinction between choir and lay sisters in 1908, it was necessary for some sisters to be singled out and propelled into positions of academic prominence and achievement if they were to accomplish their goals in women’s higher education. Formal education, not socioeconomic level, became a new source of tension within the community. Sisters who earned graduate degrees created a new distinction, and at times it must have been difficult to mesh the religious goals of uniformity and solidarity with the “special status” awarded to college faculty.

In the early days of the College of St. Catherine, “one group within the community thought that sisters would be tempted to pride if they held academic degrees. They considered that it was sufficient preparation to pursue the courses, without being presented for graduation honors.” Young Sister Antonia McHugh thought “this was worse than nonsense—she was sure that those who had this notion were too fearful of failure to make the effort to achieve standards.” Fortunately for her, Bishop Ireland agreed and proceeded to send sisters to obtain advanced degrees at the University of Chicago.

90 Sister Evelyn O‘Neill, however, received a different response from the motherhouse in St. Louis as she struggled to run a secondary academy and take advanced course work in hopes of establishing a college in Kansas City. This problem was not an issue of “pride” but an illustration of the “choice” many nuns were forced to make between daily teaching duties and working toward individual professional development and graduate degrees. Sister Evelyn O’Neill was chastised by Reverend Mother Agnes Gonzaga Ryan in 1913: “I am convinced you are doing too much [studying] and wish you to discontinue at once.... Stop all study immediately—this is a direct order; please understand it so; meant to give your mind the relief it needs. If you think it well for the sisters to keep on you may let them do so although I believe if they gave more time to class work and less to personal improvement during the year it would bring better results at the school.”

91 This struggle both to perform community work and to obtain higher education and the battle between humility and achievement would continue well into the twentieth century and was resolved only with the changes brought about by Vatican II in the 1960s.

By the 1920s, CSJS who came from France in 1836 to teach American girls had established girls’ secondary academies, high schools, and colleges in every part of the United States. Using Protestant and secular academies and colleges as an impetus and meshing American ideas about female education with their own heritage and religious ideals, CSJS expanded their educational outreach to and influence on females, from young girls to college women. Their nineteenth-century secondary academies touched the lives of Catholic and non-Catholic girls and laid the groundwork for Catholic women’s colleges. The CSJ movement into higher education set a precedent for growth and achievement through the twentieth century and marked the sisters, along with other women religious, as important shapers of Catholic culture and American life.