7

Succoring the Needy

The most visible and impressive aspect of the Catholic response to the social problems of the age was the founding of hospitals and orphanages. The people most responsible were women religious.... Care of the sick and of orphans was an area that attracted their attention from the very beginning.

-The American Catholic Experience

Nursing, Hospitals, and Social Services

Although the history of the development of hospitals and orphanages is separate and distinct, in the early days of most new missions to American cities, the CSJS often provided nursing services and care for orphans in the same building. The early CSJ convents, academies, and hospitals routinely cared for abandoned infants and children, but epidemics and wars created a dual need for more hospital and child care since many children were orphaned or abandoned during these citywide or national crises. Between 1836 and 1920, the sisters’ nursing activities during epidemics and two wars spawned the development of CSJ hospitals in every region of the country but the Deep South.

Nursing and Hospitals

Even without the social prohibitions of gender, nursing was also tedious, emotionally and physically exhausting, and dangerous, particularly when epidemics of highly contagious diseases and/or devastating war wounds required nurses to endure long hours, tedious bodily care, emotional and physical stress, and a high risk of death. Antebellum hospitals were viewed as places to die and places where the indigent were sent because they had no family to care for them. For women religious the religious ideal of “charity to the neighbor” provided them with the physical and emotional strength needed to carry out the necessary work. Viewed within a spiritual context, nursing gave sisters the opportunity to tend to the physical and spiritual needs of their patients and, if necessary, face martyrdom for their efforts. Also, their vow as celibate women allowed them to ignore some prescriptive gender prohibitions and, to a limited degree, nurse males or anyone who needed their assistance. In Europe and the United States, the constitutions and customs manuals of most religious communities had specific mandates and instructions for visiting and caring for the sick.

3Although historically care for the sick has been viewed by some as a “religious calling,” the nursing profession received a boost and a renewal of the tie between religious commitment and nursing in the mid-nineteenth century with the accolades given Florence Nightingale and her nurses during the Crimean War. Twenty-four of her thirty-eight nurses were from Anglican and Roman Catholic religious orders. In Europe and the United States their well-publicized success brought recognition and a heightened public interest in nursing as a vocation and intensified the religious commitment of sisters to nursing. Some antebellum Protestant women looked for ways to participate in their own “religious communities” devoted to their “calling” to care for the sick. Lutheran and Episcopalian women, although attacked for their “Catholic tendencies,” became deaconesses, staffed some hospitals, and managed to establish small numbers of sisterhoods in the United States.

4The CSJS’ entry into American health care began more as spontaneous responses to “nursing opportunities” (epidemics, disasters, and wars) than as a systematic plan for sister-run hospitals. In fact, the creation and staffing of CSJ hospitals often resulted from the successful nursing done by sisters in their convents, in private homes, and in “isolation camps” during citywide epidemics. During the early decades of the CSJ mission in St. Louis, the sisters provided nursing care after devastating floods, riverboat accidents, and chronic cholera outbreaks prevalent in Mississippi River ports. Although the Sisters of Charity had a hospital by 1828 in St. Louis, the CSJS also nursed cholera victims during outbreaks in the 1840s, 1850s, and 1860s.

5When the CSJS moved outside of St. Louis, their nursing activities expanded as well. In the late 1840s sisters began nursing cholera victims in Philadelphia, where the CSJS staffed their first American hospital from 1849 to 1859. In the early 1850s the sisters sent to Toronto, Canada, Wheeling, (West) Virginia, and St. Paul, Minnesota, also provided nursing during epidemics. CSJS were specifically called to Wheeling to staff the first private hospital that opened in the city in 1853.

6 Likewise, within a year of their arrival in St. Paul, the CSJS began nursing cholera victims. In 1854, they officially opened St. Joseph’s hospital but had been providing nursing since their arrival.

7Other Catholic sisterhoods also began health care work in antebellum America. A decade before the Civil War, twelve different religious communities staffed hospitals, both private and public, and many other religious orders gained nursing experience from their work during citywide epidemics. By 1861, sisters in seventeen congregations had created and/or were staffing approximately thirty hospitals in the United States. With this background, communities of women religious were the most experienced nurses in the country when war began, and their services were utilized by both Union and Confederate armies.

8In her book on sister-nurses during the Civil War, Mary Denis Maher states that the sisters brought four important contributions to Civil War nursing: tradition and experience, skills and religious commitment as a model for others, a willingness and ability to adapt to the needs of unpredictable situations, and written regulations for nurses, patient treatment, and personal discipline. CSJS in Philadelphia and Wheeling became part of the group of over 600 sisters from twenty-one different Catholic women’s communities, representing twelve separate orders, who served during the Civil War. One in five army nurses was a nun. The sister-nurses staffed military hospitals and hospital ships, performed battlefield triage, operated “pest” hospitals for soldiers with contagious diseases, and turned their convents into makeshift hospitals.

9When the war began the CSJS in both Philadelphia and Wheeling had almost a decade of hospital experience behind them. The Philadelphia sisters helped staff a military hospital and later the hospital ships the

Commodore and the

Wilden. With the hospital ship anchored in the middle of the river, the sisters would be sent in small boats to gather the wounded from the battlefield before transporting them back to the ship. An account by a Sister of Charity described the ordeal that sisters experienced on hospital ships: “[We] ministered to the men on board what was properly known as a floating hospital. We were often obliged to move further up the river, being unable to stand the stench from the bodies of the dead on the battlefield. This was bad enough, but what we endured on the field of battle while gathering up the wounded is beyond description.”

10 To avoid attacks from Confederate gunboats, hospital ships used the sisters’ presence as deterrents to battle. On one occasion, naval officers on a ship floating downriver near Richmond assembled the Philadelphia CSJS on deck to alert a Confederate battery of its peaceful mission. Firing began before the Confederates recognized the sisters, and flying bullets narrowly missed Mother Monica Pugh. Later in the war, CSJ teachers from the academy in McSherrystown, Pennsylvania, found themselves within a few miles of a major battle. In its aftermath, they loaded their wagon “with bandages and homemade remedies for emergency aid” and headed for the wounded at Gettysburg.

11CSJS in Wheeling, West Virginia, were already running a hospital when the war began. After the battle of Harpers Ferry, 200 wounded soldiers were brought to the sisters’ hospital. To make room, the CSJS sent the orphans to another location and agreed to make the hospital available for wartime nursing. By 1864 the CSJ Wheeling hospital officially became a “post hospital”; field tents were added, and the Union army paid the sisters $600 a year rent and commissioned the sisters as paid army nurses.

12 The sisters treated both Confederate and Union soldiers and “prepared the corpses for burial and made the shrouds.” With the scarcity of food and the inconsistency of government supplies and money, the CSJS were forced to beg in the markets. In February 1865, frustrated with the government’s unpaid bills, Mother de Chantal Keating headed to Washington to personally plead her case. Taking an “orphan girl, an insane soldier, and his keeper” with her, Irish-born Keating (in habit) probably caused quite a stir roaming the halls of the War Department; however, within two weeks the CSJS finally received their overdue government funds.

13The anti-Catholic attitudes of nursing superintendent Dorothea Dix caused friction between her and the Catholic sisterhoods during the war, but nuns made a strong positive impression on many doctors, soldiers, and some Protestant women nurses. Most doctors appreciated the nuns’ discipline, skills, and discretion. For soldiers who had never seen a nun in habit, their first experience was at best comical and at worst hostile. Some hid under blankets and refused to let the sisters touch them, others asked the nuns if they were men, and a few even spit, cursed, or struck the sisters. However, by the end of the war secular newspapers, government officials, and popular fiction lauded the nuns’ discipline, selflessness, and dedication to duty.

14 The fact that sister-nurses were perceived differently from secular women by society was not lost on one Protestant woman frustrated with Victorian gender barriers that limited her participation as a nurse. Critical of people who deemed nursing unladylike for Protestant women but acceptable for nuns, she wrote, “A very nice lady, a member of the Methodist Church, told me that she would go into the hospital if she had in it a brother, a surgeon. I wonder if the Sisters of Charity have brothers, surgeons, in the hospitals where they go? It seems strange that they can do with honor what is wrong for Christian [

sic] women to do. Well, I cannot but pity those who have such false notions of propriety.”

15 The nursing activities and notable service of women religious during the Civil War had a major effect on diminishing anti-Catholic sentiment in the United States. Their religious identity also modified gender limitations, and their highly visible presence in nineteenth-century public life helped make inroads for the acceptance and expansion of the role of other American women in the field of nursing.

16After the war the CSJS and other Catholic sisterhoods continued to expand their health care mission. Soon after the CSJS arrived in Kansas City in 1866, they opened a “neighborhood clinic” for indigents when a cholera epidemic struck the city. Eight years later and after a smallpox epidemic in 1872, the CSJS opened St. Joseph’s Hospital, one of only two hospitals in the city, in 1874.

17 CSJS also nursed the sick during the yellow fever epidemics that devastated Memphis in the 1870s. Although they were there as parochial school teachers, they became nurses during the years that the Memphis population was dying by the thousands. In fact, in 1878, during one of the last major outbreaks, six of the nine Memphis CSJS were in St. Louis for a retreat. Fearing for the lives of the remaining sisters, Reverend Mother Agatha Guthrie planned to bring them back to St. Louis, but the three sisters pleaded to stay in Memphis to nurse. Guthrie acquiesced and agreed to send three more sister-nurses, who volunteered from St. Joseph’s Hospital in Kansas City, to help the Memphis CSJS during the crisis. Since no passenger trains were allowed to enter Memphis because of the epidemic, the three CSJS reached the isolated city by riding twenty-five hours in the caboose of a freight train.

18During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, sister-run hospitals, and American hospitals in general, expanded to serve a variety of special populations.

19 In 1878 and 1880 CSJ hospitals were created to serve the needs of railroad men and miners in Prescott and Tucson, Arizona, and Georgetown, Colorado. Although the Prescott hospital and eventually the Georgetown one failed when the railroads pulled out and the mines closed, the sisters had provided health care for large groups of single men, many without families or female caregivers, who worked in accident-prone work settings and environments.

20Like their academies, CSJ hospitals accepted non-Catholics, a policy that was important enough that it was recorded in the CSJ Manual of Customs. The section providing instructions for “Sisters Employed in Hospitals” states, “If the patient be a Protestant, his religious convictions are respected, and he is not refused the consolations which his conscience may prompt him to ask. All will endeavor to show him the greatest courtesy and respect.”

21 An early-twentieth-century brochure advertising the CSJ hospital in St. Paul contained the following sentence in its first paragraph. “The Hospital is in no sense a sectarian institution, as people of all creeds and nationalities receive alike the best that modern nursing is capable of supplying.“

22 Although all CSJ hospitals served Catholics and non-Catholics, the hospitals in the West, because of their scarcity, were particularly diverse. Ledgers from the hospital in Georgetown, Colorado, from 1880 to 1914 recorded a patient population that was 90 percent male and was Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish. During the thirty-four years of the “Sisters’ Hospital,” the approximately 1,000 patients represented eighteen countries and eighteen states.

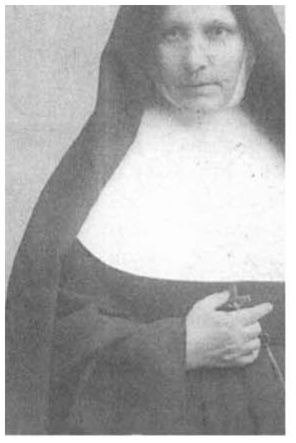

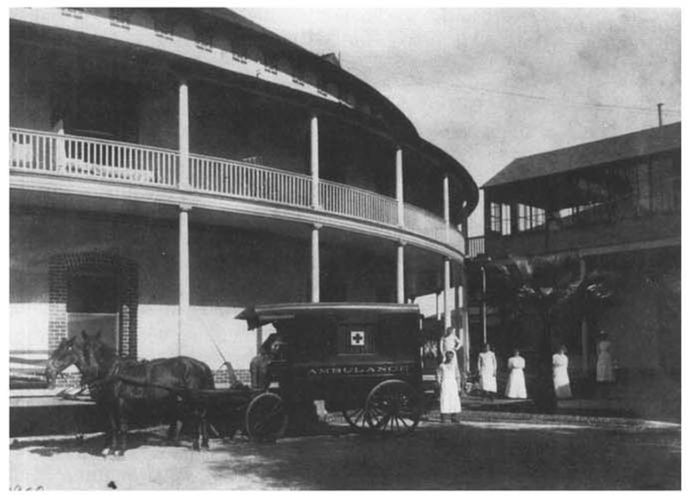

23

Horse-drawn ambulance in front of the circular tuberculosis sanatorium at St. Mary’s Hospital, Tucson, Arizona, 1900 (Courtesy of the Arizona Historical Society/Tucson, B#110,385)

In the late nineteenth century, hospitals sponsored by ethnic and/or religious groups proliferated and formed a large segment of American hospitals. The CSJS took over hospitals to serve the Menominee Indians in Wisconsin and the Catholic populations in Lutheran-dominated Minneapolis and Winona, Minnesota. Various Protestant denominations and ethnic groups organized locally to provide their special populations with hospital care. At the turn of the century in a competitive and growing market, linguistic, ethnic, racial, and religious compatibility became important factors in hospital care with which women religious hoped to serve the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of patients.

24 Kansas City, Missouri, provides a representative microcosm of late-nineteenth and earlytwentieth-century urban health care and the highly “segregated” character of urban hospitals. Although a municipal hospital began first in Kansas City, followed by the CSJ hospital in 1874, other groups created institutions catering to particular patrons. At a locale dubbed “Hospital Hill,” university and college hospitals were established in addition to the hospitals and clinics created by city funds and private interests such as the Wabash Railroad, the Missouri Pacific Railroad, the Red Cross, homeopaths, osteopaths, African Americans, German Americans, Swedish Americans, the Christian Church, the Episcopal Church, the Lutheran Church, the Scaritt Bible School, and Catholic religious orders.

25As sister hospitals and other hospitals continued to expand nationwide, the CSJS were brought back into military nursing with the Spanish-American War. When the war began, 282 women religious, including 11 CSJS, were inducted into wartime nursing. The CSJS served with the Second Division of the Volunteer Army, first at Camp Hamilton, Kentucky, then Camp Gilman, Georgia, and eventually in Matanzas, Cuba. The eleven CSJ nurses were from the sisters’ hospitals in Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Kansas City. The CSJS found army life very different from convent life, but they learned to live in their “convent tent” and, adjusting their schedules, they “soon learned to obey taps and bugle calls.” Although less intense than during the Civil War, distrust and animosity between secular nurses and sister-nurses abounded. Mother Liguori McNamara, the CSJ superior there, related in a letter to the St. Louis motherhouse that the secular nurses “are watching every move we take,” but to avoid sexual scandals some doctors wanted sisters in all the wards “as [our] presence is a check to the [secular] nurses and doctors.”

26 Indeed the sisters seemed to draw night duty, serving as a deterrent to romantic liaisons between secular nurses and doctors or patients. Besides the tension with secular nurses, McNamara also wrote about the competition between the three religious communities. Somewhat resentful that a Holy Cross Sister was given “command” over the CSJS and the Sisters of Charity, McNamara privately referred to her as “Major Lydia.” Another CSJ described the “segregation” in the nurses’ dining room. “We all dine in the same room but at different tables. The Holy Cross nuns of course have a table for themselves. The [secular] nurses are seated at another table and poor St. Joseph and Saint Vincent’s daughters (Sisters Of Charity) have a table together.”

27Even with the periodic tension, the sisters seemed to enjoy themselves and had “many hearty laughs” as they dealt with “army rumors” that changed “every two seconds” and learned to “fight and steal” supplies since “it is the only way to get along.” The CSJS also worked closely with young soldiers who served as hospital aides to care for thousands of soldiers in camp, many of whom were suffering from typhoid or malaria. The sisters became very protective of the young men, refusing to report them when they fell asleep on night duty. To spare them time in the guardhouse on “bread and water,” a sister would go “running into the wards” when a doctor made night rounds to alert the “poor lads” who found it “impossible to keep their eyes open” after midnight.

28 When the sisters returned from Cuba in 1899, their wartime experience was utilized to open new hospitals and deal with epidemics in other parts of the country.

CSJ nurses and soldiers in the military hospital at Matanzas, Cuba, 1899 (Courtesy of St. Joseph Health Center Archives, Kansas City, Mo.)

In late 1899 some sister-nurses, including Sister Liguori McNamara, headed to Hancock, Michigan, after their return from Cuba to take over a newly created hospital abandoned by the Franciscans, using their government war salaries to finance the venture. When smallpox broke out during the first year, the sisters again found themselves in an “isolation camp.” Harassed nightly by fearful and angry townspeople who wanted the sisters and their patients far from town, two sisters with wartime nursing experience moved with the ill patients to an isolated shack on the edge of the city. For over a month they were quarantined with their patients, coming out of the building only to receive food that was left on a fence post at a safe distance from the house.

29Likewise in 1918, with many doctors and nurses participating in the war effort, the widespread influenza epidemic strained the space and staffs in Catholic sister hospitals as it did in all American hospitals. Sisters volunteered to staff some “emergency hospitals,” even as they nursed the adults and children in their social service institutions and provided some home care nursing. CSJ hospitals in densely populated areas such as St. Paul, Minneapolis, Kansas City, and New York State struggled both to meet the war needs and to handle the flu crisis. Although CSJS did not nurse in World War I, many of the graduates of their nursing schools did.

30By the end of the decade, the CSJS had added additional hospitals in North Dakota and upstate New York. Of the sixteen hospitals founded by the Carondelet CSJS after their arrival in 1836, ten remained under their sponsorship, serving approximately 17,000 patients a year in 1920.

31 If hospitals founded by diocesan and daughter communities were also included, the Sisters of St. Joseph had founded thirty-five hospitals nationwide.

32 Although they had come to St. Louis originally to teach, they had become full participants in the nation’s health care system. Beginning with “nursing opportunities” that placed them and other Catholic sisterhoods on the front lines during epidemics, disasters, and wars, they had parlayed their learned expertise into creating major health care institutions that over time served both Catholics and non-Catholics. However, two factors had dramatically changed their nursing activities during their first eighty-four years. First, hospitals and women nurses had become an accepted feature in American health care, and sister-nurses and sister-run hospitals formed an important part of the national scene. In the vanguard of early-nineteenth-century nursing and hospital care, sister-run hospitals in the twentieth century remained a visible symbol of American Catholic culture and its growing prominence in American public life. Second, as large numbers of trained doctors and nurses utilized advanced technology and staffed the growing number of American hospitals, schooling for all medical personnel became more rigorous and regulated. As in the arena of education, by the early twentieth century, sisters had to make adjustments to meet the growing demands of formal nurses’ training.

During much of the nineteenth century, the sisters’ discipline, dedication, and hands-on experience helped compensate for lack of formal training in nursing care. Dressed in habit and avoiding “singularity,” sister-nurses responded well to the regulation, routine, and stoicism sometimes necessary for handling what could be highly charged, emotional situations, particularly during a crisis. But they were not the heartless “machines” that some Protestant nurses had labeled them during wartime.

33 Undoubtedly sisters were frightened and often repulsed by their nursing duties as they battled their own natural reactions and sometimes insufficient training. Throughout most of the nineteenth century, training was achieved through on-the-job experience, mentoring, and, later in the century, in-house teaching by doctors. Sisters recorded some of their difficulties and recognized the problems of mastering both the medical skills and emotional aspects of the job. Mother St. John Fournier had to help her young novices and sisters through the initial training in their Philadelphia hospital in the late 1840s. She wrote, “Our Sisters were so afraid of the dying that I had to stay with them during the night. If there was a festering sore to dress the Sister would faint. Little by little these poor children got accustomed to working for the sick and the dying.”

34Arriving in Memphis to teach at St. Patrick’s school in 1873, two CSJS found the Memphis sisters in the midst of a yellow fever epidemic. The new arrivals “were both deathly afraid of the fever on hearing of its ravages” and asked to remain in the convent while the other CSJS went to nurse the victims. Two days later when the doorbell rang the sisters were afraid to answer it, fearing it was a plague-stricken person needing their assistance. After repeated rings, Sister Mary Walsh opened the door to a local priest who asked her to nurse a dying parishioner and his family. After a “goodly number of tears, with fear and trembling,” Sister Mary agreed to care for the patient.

35At St. Mary’s Hospital in Tucson, Sister Mary Thomas Lavin, who was volunteering for night duty, spent an anxious evening worrying that some of the critically ill patients might die. To allay her fears she checked on them often. As one patient explained the next morning, “Every time I opened my eyes there was Sister standing over me with her lantern and pitcher of water. I never had so much water in my life.”

36 Spanish-American War nurse Mother Liguori McNamara had eight very experienced CSJ nurses with her at the military camps and in Cuba, but she openly fretted about the lack of experience of two members of her group. The need to respond to the rigorous demands of army doctors and to compete with other sister-nurses and secular nurses put her under pressure to perform—and perform well. Alerting the Reverend Mother in St. Louis to her concern that even her most experienced nurses had to work hard to “hold our own” to meet the needs of the hundreds of disease-stricken soldiers, she wrote, “I do not think it advisable to send any more Sisters for the present.... Unless they are trained and well-trained, there is no use for them here.”

37Before the 1870s there had been no formal nurses’ training programs in the United States and nuns were the most experienced group of nurses in the country. However, by 1873 the need for better preparation of hospital personnel led to the introduction of formal nurses’ training at hospitals in New York City, New Haven, and Boston. The first Catholic nursing school was opened in 1886 by the Hospital Sisters of St. Francis in Springfield, Illinois. CSJ hospitals experienced the same pressures as other hospitals from doctors, patients, and state accrediting boards to upgrade the preparation of nurses. They also began to have difficulty obtaining a sufficient number of sisters to fill the staffing needs of their fast-growing health care institutions. To meet these demands CSJ- and other sister-run hospitals began creating formal schools of nursing that included training not only for sisters but for laywomen as well.

38Religion, gender, and the experiences of nursing in the Civil War strongly affected the early training schools for nurses. Historians note that these early secular nursing schools maintained a blend of “religious, domestic, and military ideals identified with the ‘calling’ to nursing.”

39 Likewise, the early application forms and informational brochures for CSJ nursing schools are reminiscent of those connected to entry into a religious community and the training of postulants and novices. When in 1915 Hulda Olivia Larson applied for admittance to the CSJ St. Michael’s Hospital Nursing School in Grand Forks, North Dakota, she was expected to be between twenty and thirty years old, have a common school education, be in good health, and provide three character references. The young female applicants were provided with lists of rules, regulations, textbooks, curriculum, clothes to bring, and behavioral expectations. They received a modest room and board and a small monthly stipend to defer uniform or other school expenses. After a two-month probationary period they were allowed to wear the “training-school uniform” but “not allowed to wear laces, ribbons or jewelry while on duty.” Subject to dismissal at any time for “inefficiency or misconduct,” candidates had to complete three years of course work and on-the-job training successfully before they would receive their diplomas.

40The sisters at St. Joseph’s Hospital in St. Paul began the first CSJ school of nursing in 1894, followed closely by hospitals in Minneapolis and Kansas City.

41 CSJS who nursed during the Spanish-American War or graduates of nursing schools often began nursing programs for CSJ hospitals, and some of these sisters had high levels of formal training at institutions such as Bellevue Hospital, Columbia University, and Mercy Hospital Chicago. Two older, highly educated converts played leading roles in the early days of CSJ schools of nursing. Swedish-born Sister Kathla Svenson received her training at Augustana Hospital in Chicago before she entered the community at age thirty-five. She served as director of the St. Mary’s School of Nursing in Minneapolis and helped prepare the first three sisters from the hospital to pass the Minnesota State Board Examinations in 1914 to become registered nurses.

42 Sister Giles Phillips, daughter and sister of Protestant ministers, received her training in Kansas City and later at Columbia University. She entered the community at age twenty-nine and soon after became director of nursing at St. Joseph’s Hospital and later at the CSJ hospital in Hancock, Michigan.

43 These highly trained and experienced sister-nurses often moved from one CSJ hospital to another to train new nurses and share expertise. This sharing of experience provided a consistent and rigorous curriculum for CSJ nursing schools, an important advantage over other nursing schools since the first standard curriculum for schools of nurses was not published until 1917.

44Training and teaching nurses was one of many collaborative endeavors between male doctors and sister-nurses. The nuns taught the textbook courses and nursing methods and the doctors provided lectures in their specialty areas. The growing specialization of health care, the sisters’ primary role in administration, the increasing revenue of the larger hospitals, and the expanding prestige of doctors provided a certain autonomy and power for hospital sisters that went beyond the gender politics of the male doctor-female nurse dyad. Doctors and sisters worked in a parallel but interdependent universe with doctors controlling the medical staff and policies and sisters providing the nursing, training of nurses, housekeeping, and most administrative duties. In the 1920s at St. Mary’s in Amsterdam, New York, the administrative and staffing contribution of the CSJS was significant and typical of most sister-run hospitals. Nuns functioned as hospital superintendents, pharmacists, nursing supervisors and faculty, pediatric supervisors, emergency and operating room supervisors, blood bank and floor supervisors, lab and x-ray technicians, cooks, laundry supervisors, seamstresses, bookkeepers, and clerks. Sister Austin Dever’s role was probably the most unique since she supervised the main office and “cared for the chickens.” All these roles were filled by sisters who took no salary and were the sole owners of the hospital.

45Clearly, doctors and sisters needed each other for the hospital to remain medically accredited and financially viable. When doctors in Kansas City felt they needed a new hospital and updated equipment in 1914, the physicians had to convince the CSJS to fund it. A series of letters from doctors in Kansas City to the superior general in St. Louis provides interesting insights into the deferential discourse between doctors and the nuns who sponsored the institutions. Calling the doctors at St. Joseph’s Hospital “twenty conscientious, faithful servants” and “your staff,” Dr. J. D. Griffith pleaded with the female superior, “We beg of you a conference.”

46The control and autonomy exerted by CSJS and other sisters working in hospitals extended to leadership in secular, national nursing and hospital associations. Early CSJ nurse educators in Arizona, Minnesota, and Missouri held offices on their respective state boards of nursing, the National League of Nursing Education (NLNE), and the Catholic Hospital Association (CHA).

47 In fact, in 1914 fourteen CSJS from the St. Paul province met with Father Charles Moulinier, a regent of the medical school at Marquette University, to discuss founding a national Catholic organization to push for professionalization and higher standards for Catholic hospitals. The CHAbegan a year later, and the sisters held many prominent positions in the organization, which provided a “unique forum for women religious representing the communities engaged in health care.”

48Although Moulinier expected the CHA to be a “sister’s organization” and felt a sister should always be its president, conservative critics had narrower interpretations of what the nun’s function was in the medical community. Compared to sisters in national educational and social service organizations the hospital sisters had unprecedented influence, but patronizing and sexist attitudes hampered the sisters’ autonomy in the CHA and in their hospitals. In the early years of the CHA, conference discussions and written debate were dominated by male clerics who obsessed about whether sisters should attend night meetings, take courses from seculars, receive training in obstetrics and massage therapy, wear “washable” habits, use labor-saving devices, and join secular accrediting boards that “graded” Catholic hospitals and nursing schools. Male clergy were particularly concerned with sisters’ participation in the secular and female-dominated National League of Nursing Education. Catholic hospital historian Christopher Kauffman places conservative critics of the CHA in two camps: One group feared that the CHA was “chasing after modern ways and secularism,” while another feared a loss of Catholic identity, since “this whole movement with its Protestant and Jewish lecturers, will gradually turn over our hospitals to control of non-Catholic bodies, such as the American Medical Association.”

49When sister-nurses’ activities could mean life or death for patients, nuns sometimes found themselves trapped in a choice between “modern science” and medieval religious practices. In practical terms it could mean a choice between staying with a patient or making it to prayers on time or between assisting in an operating room or avoiding the sight of the male body. At times, “holy obedience” was indeed challenged even when directives came from the highest authority. Representatives from the Vatican, who were concerned about the work of sisters in American hospitals, attempted to investigate the activities of sister-nurses. In 1909 superiors of women’s communities received a letter asking whether hospital sisters were performing activities “not altogether becoming to virgins dedicated to God.” The Vatican prelate was particularly interested in whether men were patients, whether the sisters did bandaging or gave baths, massages, or “other personal services,” and whether sisters assisted in operations, “especially on the bodies of men.” A superior in the St. Paul province penned a very diplomatic letter in response. Telling the cleric that the sisters did have male patients, never gave massages, and performed only “slight bandaging now and then,” she described the operating room: “At times Sisters may be found in the vicinity of the operating rooms, so as to see that whatever is needed is duly provided: but ... nothing is done or allowed that could conflict with the strictest rules of religious modesty.”

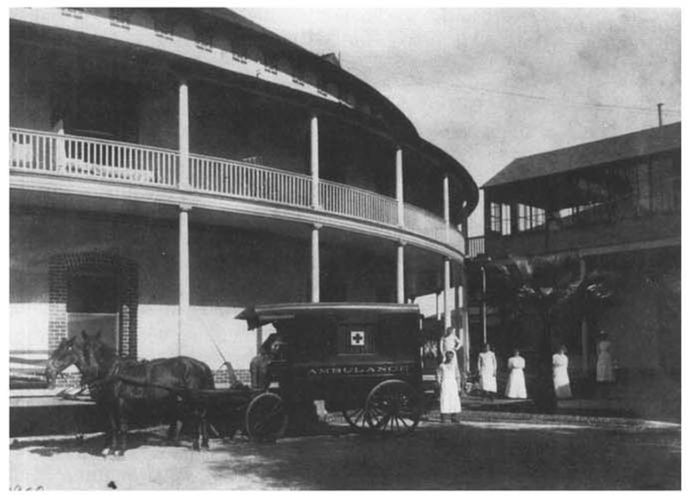

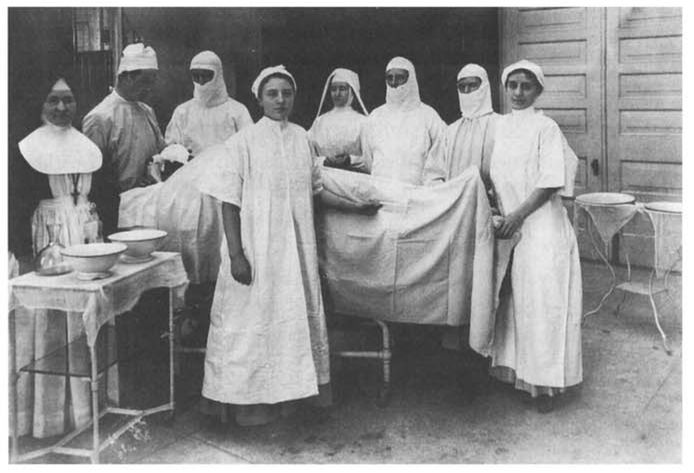

50 In reality, some sisters had received special training as operating room nurses, and archival photographs reveal that for some sisters being in the “vicinity of the operating room” clearly meant standing over the operating table next to the surgeon. CSJS and other hospital sisters, like their peers in education, tried to find a balance among the sometimes conflicting demands of their ideals and identity as nuns, to preserve autonomy within their own institutions, and to work toward professionalization in secular American society.

Orphanages and Other Social Services

Besides the emphasis on teaching and nursing, the European and American CSJ constitutions document the importance of care for orphans, the poor, and specifically young girls and women. Caring for orphans, both girls and boys, began immediately after the sisters’ arrival in St. Louis, and it became an important aspect of the CSJ mission to the United States. Early orphan care was usually provided at convents and hospitals as the CSJS expanded across America in the nineteenth century. When monies became available, separate institutions were built to house the growing number of Catholic immigrant and poor children needing assistance. Although the CSJS’ main focus in social service became orphanages, between 1836 and 1920 they, like many other Catholic sisterhoods, also staffed charitable institutions that provided for widows, working women, women with dependent children, infants, and pregnant women and offered child day care. Creating an independent system parallel to Protestant charities, Catholic sisterhoods developed a large network of charitable institutions that spanned the United States.51

Surgery, St. Mary’s Hospital, Minneapolis, 1908 or 1909 (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Archives, St. Paul province)

Historians of women have documented the importance of gender ideology in the benevolent activities of Protestant and secular women, arguing that gender construction gave distinct opportunities to create women’s culture and public activities even as it set limits on them.

52 In much the same way that female nursing moved from the home to the public domain, public female benevolence reflected women’s family role as providers of physical and emotional nurturing. Historian Anne Firor Scott writes that women realized that power and influence resided in collective action and therefore formed all manner of voluntary organizations “that lay at the very heart of American social and political development” in the nineteenth century. “[W]omen’s associations were literally everywhere, known or unknown, famous or obscure; young or ancient; auxiliary or freestanding; reactionary, conservative, liberal, radical or a mix of all four; old women, young women, black women, white women, women from every ethnic group, every religious group had their societies.”

53Although women’s public activities and goals became more secularized in the twentieth century, for most of the nineteenth century, Protestant women used religious ideology as well as gender to justify their presence and influence in public charitable work, particularly when that work involved assisting women and children.

54 Some of the first philanthropic organizations and activities begun by Protestant women focused on expanding women’s “natural” duties into the public domain. With increases in immigration and the growing problems of urbanization and industrialization, nineteenth-century Americans debated, as Europeans had for centuries, how best to differentiate between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor.

55 For some Protestant women this meant expressing their anti-Catholic sentiments. Emphasizing their “natural” role in child care, many Protestant women’s organizations focused on “saving children” from a “Popish” religion that became synonymous with poverty and intemperance. This attitude “underpinned the cultural authority of a multilayered middle class over the poor, the non-Protestant and the fallen.”

56 As one historian summarized, “In the name of a Protestant Christ, nineteenth-century women’s activists sought to contain the sexuality of working-class women and to remove Catholic children from ‘undesirable’ homes and place them as apprentices on Protestant farms.”

57Such actions alarmed Catholic clergy and mobilized the Catholic sisterhoods to expand their mission by creating more Catholic orphanages in the United States. As historian Maureen Fitzgerald notes, “Nuns’ efforts to counteract the influence of the ‘child-savers’ became the single most important strain of Catholic charitable work through the rest of the century.”

58 In her extensive study of Catholic philanthropy in America, Mary Oates states that early in the nineteenth century Catholics saw Protestant benevolent agencies as “mainly proselytizing forums” and Protestant institutions as “dangerous.” In response to overt proselytizing but also to demonstrate patriotism and social responsibility within the mainstream Protestant culture, the Catholic Church, mainly through the work of the nuns, began a massive institutional approach to charity. Sister-run charities, particularly Catholic orphanages, became a highly visible response to the social problems of nineteenth-century America and “represented an original development in American philanthropy in general.” Oates explains,

Given the rhetoric of the day concerning women’s proper sphere and [nuns’] exclusion from clerical offices in the church, their prominence in its voluntary sector was a phenomenon remarked upon by Protestant and Catholic alike. Although mainstream suspicion of them lingered, ... their public vows, distinctive dress, ecclesiastical approbation, and essential social mission brought them considerable status within the church and, to a lesser extent, in the wider society as well.

59Fitzgerald not only agrees with Oates but argues, quite convincingly, that Catholic sisterhoods in New York City and other large urban centers had a major impact on some cities’ welfare systems.

60 Certain characteristics of Catholic religious life made this possible. Unlike most Protestant women who initially learned the skills necessary for collective action in small religious or charitable organizations and usually had to balance these activities with their duties to their families, the sisters had to their advantage a centuries-old tradition of female collective living and activity, a large mobile workforce, disciplined and narrowly focused goals, and the ability to react quickly to the needs of a given situation. Responding to the problems of a growing immigrant, working-class population and coping with the aftermath of wars and epidemics, women religious, incorporating both gender ideology and religious ideals, were “natural” providers for orphaned children.

For the CSJS, the creation and maintenance of orphan asylums formed the mainstay of their social service in the United States. The sisters’ activity peaked in the 1890s when they staffed twelve orphan and half-orphan asylums in six states; by 1920, they were maintaining nine different establishments that cared for over 1,200 children. These institutions were located in large and medium-sized cities in New York, Minnesota, Illinois, Missouri, and Arizona.

61 In their orphanages the sisters attempted to fill the role of “parent,” “protector,” “nurse,” “teacher,” and sometimes “child advocate.” In a brochure describing St. Joseph’s Orphan Home for Boys in St. Louis, the CSJS advertised that they “endeavored to supply a mother’s care.” Their activities placed them in the public arena that included the court system, city hospitals, parish schools, social service agencies, and private families. The CSJS requested references for prospective adoptive parents and at times required payment from biological parents who wished to leave their child temporarily in the sisters’ care.

62Records from CSJ orphanages document that children were brought there by parents, relatives, police officers, clergy, or court order, or simply abandoned on the premises. The CSJ orphanage in Tucson, the first in Arizona, had no admission requirements other than that the child must be three years old and without a “natural protector or guardian.”

63 Nineteenth-century records clearly show that almost half of the children the sisters cared for were “reclaimed” or “taken” by one of the parents or relatives after a few months or sometimes a few years. St. Bridget’s Half-Orphanage had a very transitory clientele: the average stay was one year. Between 1872 and 1875, St. Bridget’s admitted 186 children, and of these 86 were “claimed by relatives.”

64 Clearly the sisters’ orphanages served as a backup child care facility for parents who needed temporary assistance. Correspondence between Chicago clerics described the plight of working-class Catholics and how sister-run orphanages attempted to support these families during hard times: “These poor people try to put their children ... where they will be able to see them frequently and bring them clothing and other necessaries.”

65Consequently, the nineteenth-century orphanage was sometimes used as a temporary care facility when a parent was ill, financially burdened, or simply unable to cope with child care. CSJ orphanage records reveal the irony in the contemporary discussion of the “breakdown of the family” and nostalgia for the bygone days when families “took care of their own.” Sometimes children were brought to the orphanage because they were ill or handicapped and the parents would not or could not care for them. In 1910, for example, two days after five-year-old twins and their seven-year-old sister were admitted to the sisters’ care, they were rushed to the hospital. Scarlet fever, small pox, pneumonia, and measles were common conditions for abandoned children.

66 The CSJ Home for the Friendless in Chicago accepted children who were “neglected, ill-treated, or abandoned by parents or guardians ... [or] whose mother is ill and whose father’s resources are insufficient to provide the necessary care for the little ones.”

67 The records for the girls’ home in Kansas City listed the specific family situation for eighty-one children admitted during one year: 16 percent had both parents living, 23 percent had both parents deceased, 26 percent had only a father living, and 35 percent had only a mother living. The fact that more children had a single mother probably said less about parenting commitment than the economic realities of working-class women trying to care for a family in a gender- and class-biased wage system. The sisters were no Pollyannas concerning their surroundings, and they peppered the ledger with additional comments about the girls’ families, such as “parents divorced,” “mother insane,” “parents separated and worthless.”

68From the earliest days the CSJS functioned as caseworkers by attempting to find homes for the children who had no known relatives. Although the sisters interviewed and required references from prospective adoptive parents, problems still arose and children could be “passed around” or returned if the adoptive parents decided they did not want the child. For example, Nellie Wolf Thompson, who was abandoned by her parents, was five when she came to a CSJ orphanage in 1892. Five months later she was adopted by Mrs. Edmund Hoffman, who twenty-two days later left her at the “city hospital.” Nellie was then transferred to the “children’s hospital” and returned to the CSJ orphanage after nine months.

69 By the early twentieth century most Catholic sisters were working with state agencies to screen prospective parents more effectively. After 1907, the Minnesota sisterhoods worked with the State Board of Control and had two sisters present at court placement hearings for all Catholic children. They also initiated a three- to six-month probation contract with the adoptive parents to make sure the placement was a good one.

70The sister’s role as protector and nurse more often meant daily care and protection from harm. Fires were always a major fear in orphanages, particularly those housing small children. The fast action of sisters in Troy, New York, for instance, saved the children, all eight years old or younger, when the St. Joseph’s Infant Home burned to the ground. Smelling something hot, and though no flames were visible, the sisters awoke the children and called the fire department. The youngsters were dressed, told they were going on “an excursion,” and marched or carried out of the house into a freezing December night.

71 Probably the most dramatic fire and escape came in the Chicago Fire of 1871. A CSJ orphanage located on lake-front property housed over 200 children and eighteen CSJS. Sister Incarnation McDonough wrote a firsthand account of the sisters’ evacuation: “Each sister took in her arms two infants. The larger boys and girls took charge of the smaller ones, and we formed a close line of march ... to hold on to one another. We started walking northward not knowing where we were going. Mad rushing people, some jumping through windows to save their lives, the hurrying of horses and vehicles, made it almost impossible to keep together. The greatest difficulty was crossing the streets.” The large group wound its way through the city, led by Mother Mary Joseph Kennedy, and as they were attempting to cross a street two teams of horses came rushing toward them from both directions. Seeing the children, one driver halted, but the other driver would not. Sister Incarnation wrote: “Mother stepped up and took the horses by the bridle, while he continued to beat them. Passersby, seeing the situation, tore the driver from his seat, and gave him what he richly deserved. While this was going on, we seized our opportunity and got across.”

72The gender and age of children often determined which sister-run institutions they would be placed in. As in parochial schools, gender segregation was important; some CSJ orphanages cared for only one sex, while others had both boys and girls. Compared to some religious orders, the CSJS were unusual in caring for boys. Girls who were not adopted often stayed until age sixteen or seventeen, but boys were usually transferred to a home operated by male brotherhoods or moved into a home or work setting by age fourteen.

73 The CSJ orphanages show an interesting pattern of gender segregation and differences among the four provinces. In large Midwestern cities in the St. Louis and St. Paul provinces, single-sex orphanages were the norm, but in Arizona, with small numbers of children, and in New York, with large numbers of children, CSJ institutions housed the sexes together but on separate floors or wings of the facility.

74Catholic orphanages, which were attacked by critics as warehouses where children received no individual care, varied widely in both numbers of children and numbers of sisters available to care for them. CSJ records indicate that critics may have overstated this problem. Although complete CSJ records are not available, data from the 1880s to 1920 from cities in New York, Arizona, Missouri, Illinois, and Minnesota provide some interesting insights into the sister/child ratio of these institutions. The number of children varied, but most CSJ orphanages each housed from 60 to 200 children. The data on numbers of sisters are remarkably similar in that most CSJ orphanages regardless of size averaged one sister per eleven children. In some orphanages in Missouri, Illinois, and Minnesota the ratio was even better, with one sister per eight children.

75In addition to the daily care of these children, CSJS provided the children with elementary school classes and vocational training. Sometimes the children were sent to a nearby parochial school, but many times the sisters maintained an elementary school in the institution. Providing basic education and teaching gender-specific work skills were considered important means to make the children self-sufficient and employable when they left the orphanage. A recent study states that most orphanages “provided educational advantages beyond the reach of most nineteenth-century families.”

76As caregivers and educators, the CSJS also cared for the spiritual needs of their orphaned children. A publication for a CSJ home for boys states, “Religious instruction is given the prominence due to it, as the only foundation of our holy religion.”

77 Besides descriptions of baptisms, confirmations, and prayer activities, the sisters recorded their success as role models for religious life. In 1883, Sarah, Mary, Peter, and Teresa Dunn were brought to a CSJ orphanage after the death of their parents. Years later an entry in the orphanage record book states, with obvious pride, that three of the four children entered religious life. Peter went on to become a monsignor and started an orphanage in St. Louis.

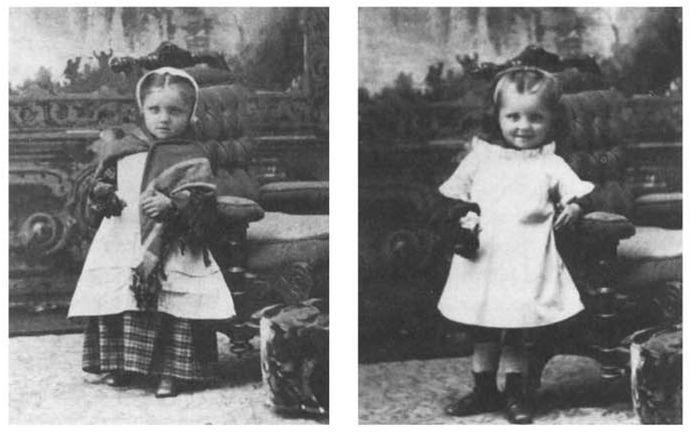

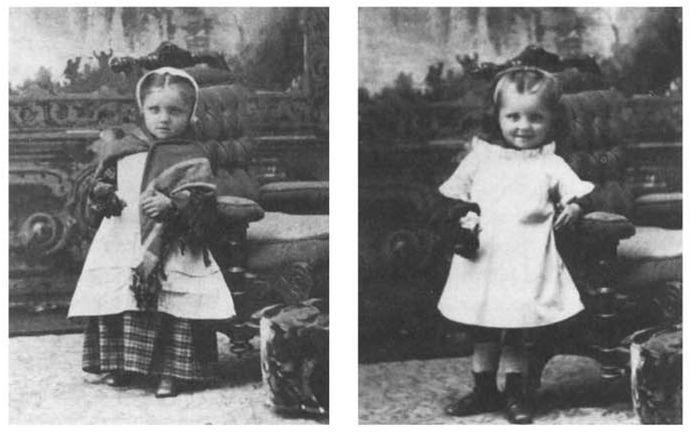

78

An immigrant child as brought to Aemilianum Orphan Asylum (left) and later in orphan’s uniform (right), Marquette, Michigan, circa 1880 (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph f Carondelet Archives, St. Louis province)

The traditional orphanage was the mainstay of CSJ social service activity between 1836 and 1920, but the sisters established other institutions that attempted to provide specific support to single women and single women with families. The CSJS came to Philadelphia to take over an orphanage, but within three years they not only had engaged in hospital work but had created St. Ann’s Widows’ Home by 1850. The aim of the widows’ home was “to take care of poor widows and even of single old ladies from the age of forty or fifty ’til their death.” Apparently there was a great need for this kind of facility. As one sister wrote, “The house can accommodate only thirty-six; it is always full and there is always a number waiting for empty places.”

79 In 1885, the St. Louis CSJS opened another facility for women only, the Home of the Immaculate Conception for Working Women. The establishment was unique in that it served as a convent for sister-teachers, a housing facility or “night refuge” for young single women, mostly Irish, and an employment bureau for domestic servants.

80Two facilities that opened in the twentieth century show the CSJS moving into different types of social service that were precursors to their post-1920 activities. A large-scale social service institution was established in Chicago in 1912 when two CSJ orphanages were consolidated and a “Home for the Friendless” was created by the diocese and run by the CSJS. More akin to a settlement house or contemporary shelter than a traditional orphanage, the well-financed institution was to be a “temporary refuge for homeless women and children.” Referring to a “comparatively new line of charitable work,” the early documents described a large campus facility that included living quarters, infirmary, laundry, school, and playgrounds. It accommodated “mothers with young families who have been abandoned or left destitute ... women, young girls and children without protection ... women and girls who are traveling and find themselves in a strange city without friends or money [and] children who are neglected, ill-treated or abandoned by parents.”

81 An even more “modern” establishment was created in 1917 in one of the poorest sections of Albany, New York. CSJS staffed the Masterson Day Nursery, which provided day care facilities for preschool and school-age children of working mothers who needed a place for their children to play safely and receive meals. During one year it provided approximately 15,000 meals to the preschool children who stayed all day and to schoolchildren who came for lunch and after-school care.

82Historians have credited nuns with providing a support system for Catholic women and girls that particularly benefited the great numbers of Irish girls and women in large cities. Male clerics, preferring to focus on children instead of adult women, often resisted efforts by nuns to establish and maintain support institutions for women only.

83 According to historian Hasia Diner, Catholic sisterhoods, particularly Irish orders, provided an extensive national network that “sustained Irish women from childhood to old age [and] services available to women exceeded those available to men.”

84Unlike sisters who worked in hospitals, CSJS and other sisters involved in social service did not actively participate on secular state charity boards or Catholic bureaus of charity. When only eight nuns attended the first National Conference of Catholic Charities in 1910, the sisters were heavily criticized. Since sister-nurses who created policy and actively participated on external boards including the Catholic Hospital Association were criticized

because of their involvement, this reaction presented an interesting gender paradox. Attacked by laity and male clerics, sisters who had been encouraged and at times pressured to build social service institutions to support Catholic children and the poor, and who had done so at a great personal and financial cost, were now told their ideas and institutions were “old fashioned” and not sufficiently “scientific.” The sisters were depicted as “out of touch” and too easily “hoodwinked” by the undeserving poor.

85Lack of money and education as well as fear of losing autonomy to central Catholic charity boards kept sisters away from the national organization. Sisters in social service had little opportunity for higher education and consequently less interaction with other secular professionals or new trends in the field. By 1910 the few sisters selected for higher education were often chosen because of the type of work they were expected to do in the community. Teaching positions at the secondary and postsecondary level still received only the brightest sisters who were given some of the best educational opportunities affordable, but the need for well-trained sister-nurses to supervise all areas of the hospitals insured that larger numbers of them also obtained college degrees. Consequently, with limited funds and the increasing demands of professionalization in the twentieth century, the education of sisters in social service took a backseat to the need to educate sisters in education and health care.

Financing and Networking with Laity

Sisters involved in health care and social service institutions faced challenges in maintaining financial stability and networking with male and female laity. In both hospitals and social service institutions sisters provided most of the labor, rarely received salaries, and had the major responsibility for funding. Although the hospitals became financially profitable in the twentieth century, solicitation trips and begging were important components of early fund-raising for both hospitals and orphanages. Sister Monica Corrigan traveled throughout Arizona to acquire funds for the hospitals in Prescott and Tucson as well as the CSJ orphanage, and her escapades on a pack mule caught the attention of Jessie Benton Fremont, the governor’s wife. According to Fremont, Sister Monica “was riding alone through the sage brush and rocks up into the mines, soliciting money for the proposed hospital, and killing snakes with a manzanita cane.”86 The spirited and indomitable Corrigan seemed to catch the interest of the public, and her solicitation activities promoting a type of “health insurance” received a lot of “good press.” The

Arizona Miner always reported her comings and goings and in 1881 wrote,

Mother Monica of Prescott branch of the sisters of St. Joseph, got back safely, after a trip of seventeen days through the mountains ... along the grade over 100 miles, visiting every camp, talking kindly, ministering angel that she is, to the workers [about] forming an association, the object of which is to have sick and wounded people along the road brought here to the hospital, and attended to, as only ladies of her order can attend to suffering mortals.

87

Twenty years later Sister Angelica Byrne, accompanied by “an orphan girl,” traveled over the same territory seeking funds to rebuild the burned out Tucson orphanage. Catching free rides in the caboose of freight trains, she took soliciting trips, returning to Tucson every six weeks to deposit her earnings. Four years later she had acquired the $16,000 to rebuild.

88CSJS and other nuns used some creative methods to support their hospitals. In Colorado and Arizona they sold monthly “subscriptions” to individual men or to railroad and mining companies. These individual and group subscriptions functioned like contemporary “insurance” policies guaranteeing that for a monthly or yearly sum an individual would have hospital care and a bed should he have an accident or become ill.

89 At St. Joseph’s Hospital in St. Paul, for $100 per year individuals could maintain a “perpetual bed” for themselves or whomever they chose “to send when a vacancy occurs.”

90 Although some of the hospital work was charity, much of it was provided to paying customers—an advantage that CSJ hospitals had over orphanages. Hospitals charged on a sliding scale for private rooms or wards; sisters in orphanages rarely received public monies or were salaried and had to rely on the donations of relatives or benefactors. With the advancement of technology, the middle-class acceptance of hospital care, and the growing prestige of male doctors, the profit and status of hospital work increased while institutional care for children began to fall out of favor in the twentieth century. As in contemporary America, child care was never a high status occupation or a lucrative one.

Parishes and dioceses rarely provided the major share of funding for hospitals or orphanages; more often it was “seed” money and occasional donations at later dates. Like the schools, many of these institutions began when a parish priest or bishop acquired a building, secured some support from Catholic and sometimes Protestant laity, and asked a group of women religious to staff it. If the CSJS agreed to staff a hospital they immediately, or within a few years, purchased the property, took on additional expenses to renovate and equip the building, and eventually filed to receive corporate status, with sisters serving as the board of directors. For example, for CSJ hospitals in Grand Forks, North Dakota, and Georgetown, Colorado, businessmen in the towns worked with local Catholic clergy to provide some property and an initial investment before asking the sisters to take charge of the facility.

91 In Amsterdam, New York, Father William Browne purchased property and a building for a hospital. Parish records indicate that Browne “gave” the hospital to the CSJS, but he actually sold it to them for $7,000, and they invested an additional $10,000 to transform the three-story building into a twenty-seven-bed hospital in 1903. Nine years later they spent $35,000 to add rooms, a sisters’ residence, and a chapel.

92 With few exceptions, the sisters financed the buildings, the cost of care and equipment, and maintenance. Sometimes they even provided the manual labor. For instance, to help lower renovation costs at St. Mary’s hospital in Amsterdam, New York, Mother Matilda Donovan, the hospital superintendent, rose very early each morning, pinned up her skirts, climbed a ladder, and painted the porch and trim “between 4:30 and 6:30 A.M. before the neighbors were awake.”

93Sometimes orphanage and hospital administrators joined forces in fairs, raffles, and other fund-raising events. In Tucson, Arizona, and Troy, New York, CSJ hospitals and orphan asylums were located in close proximity and sometimes shared a common superior and finances. In 1889 the

Tucson Daily Star advertised the upcoming “grand raffle at Reid’s opera house on New Year’s Day” to support St. Mary’s Hospital and the St. Joseph’s Orphan Home.

94 St. Joseph’s Infant Home and its maternity hospital in Troy shared receipts from a “Patriot and Field Day” that was held in 1909 to help the sisters “pay off the loan” for both institutions.

95 CSJ orphanages in Minneapolis, St. Paul, Tucson, Troy, and Kansas City saved money by having a trained sister-nurse at the orphanage treat sick children; or, in cases of serious illness children could be sent to a nearby CSJ hospital at no cost. This practice provided significant financial benefit since epidemics, childhood diseases, and the high incidence of ill, abandoned children were chronic problems in orphan homes.

96Financially sisters’ social service institutions were in a much more precarious position than hospitals: unlike hospitals that eventually generated profits for the CSJS, child care and social service institutions were lucky to break even. Although many social service institutions had a lay male board of directors, CSJS often assumed the financial burden. At St. Mary’s Home in Binghamton, New York, the bishop placed Mother Bernard Walsh in control of finances in 1888, after the male board of trustees accrued a $60,000 debt.

97 At the CSJ boys’ orphanage in Minneapolis, the male board of directors initially gave the sisters a salary, later reduced it, and finally did away with it completely. By the 1890s, their quarterly meeting “concerned itself chiefly with matters concerning the physical plant, leaving the active management and burden of support almost entirely to the Mother Superior and her staff.”

98 At times the sisters were salaried “employees,” at times not paid at all, or expected to raise most of the funds themselves. In St. Louis and Kansas City, a portion of Catholic cemetery funds helped finance orphanages, but even this yearly stipend was not secure. Father Bernard Donnelly, for example, had earmarked money from the St. Mary’s cemetery fund to help support the girls’ orphan home in Kansas City; however, a few years after Donnelly’s death, when Bishop John Hogan wanted the money for other diocesan purposes, he simply cut the monthly stipend in half, and the sisters were expected to make up the differences.

99The survival of most CSJ orphanages depended on the sisters’ free labor and their ability to acquire old clothing, supplies, and donations for their yearly expenses. Sisters from St. Mary’s Home in Binghamton went to “factories and from door to door begging” and once a year traveled in a large wagon asking local farmers to donate vegetables for the children.

100 Although it was the exception not the rule, one social service institution the CSJS staffed had solid, if not ample, funding. The diocesan-owned Home For the Friendless in Chicago was a favorite of Bishop Quigley. In this case the sisters were salaried employees and the bishop insured that funding and monies from male and female lay groups provided for the needs of the institution.

101An important and changing component for sisters in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was their interaction with Catholic laity. The remarkable aspect of Catholic philanthropy was that the massive network of charitable institutions was built by a working-class, immigrant population. Both hospitals and orphanages benefited from parish fairs, male and female benevolent organizations, special collections, and personal acts of charity. Catholic laywomen have historically supported and many times worked alongside sisters as benefactors, public advocates, organizers of parish fund-raisers, and lay staff in schools, hospitals, and social service institutions. Ladies’ aid societies, rosary and altar societies, the Queen’s Daughters, St. Margaret’s Daughters, citywide Catholic Women’s leagues and associations, and Catholic hospital guilds were examples of organized female groups that supported sister-run institutions and provided food, crafts, and monetary contributions for fairs and other fund-raising events.

102

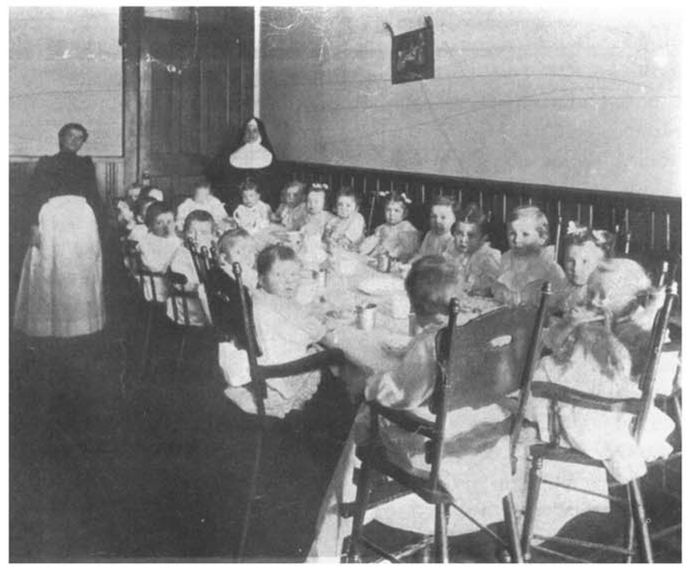

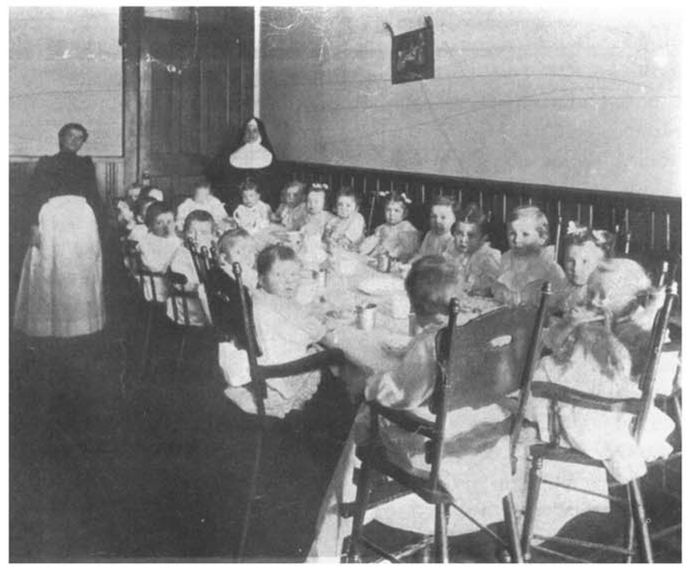

Toddlers at lunch, St. Joseph’s Infant Home, Troy, New York, circa 1910 (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Archives, Albany province)

Other laywomen worked directly with the sisters. CSJS in Minneapolis worked closely with Julia Casey, a “baby-mother” who cared for homeless infants and unmarried mothers. The babies were baptized at the CSJ orphanage, and Casey worked closely with the superior, “caring for as many as twelve babies at a time.” Casey also accompanied the superior on soliciting trips, served as a cook for parish fairs, and chaperoned the orphan children on special outings.

103 Catholic laywomen in Kansas City who were unable to achieve diocesan or private support for a small “maternity hospital” that provided care for poor pregnant women and “discarded” babies turned to the CSJS for assistance in 1907. As a way to establish obstetric training for St. Joseph’s Hospital and serve the needs of poor women, the CSJS sent student nurses to assist the employed matrons with births and infant care at the “hospital.” Besides the hands-on experience, students apparently also received a strong message about gender and class in American society. A former student recalled the “heartbreaking experiences” of witnessing the high infant mortality rate and the “little pine boxes stacked on the latticed porch at the end of the hall ... until evening when the city wagon came to take them out to a place where the city buries its outcasts and where they were all put into one unmarked grave. We have seen eight or ten go out in one single day. We nurses got the experience we went there to get, but the price we paid can never be estimated.”

104Laymen also supported the sisters’ activities through their more visible public roles as benefactors, laborers, professionals, and as members of boards, particularly for social service institutions. Because of gender politics and hierarchical and paternalistic attitudes, the sisters’ associations with laymen were at times problematic, particularly where there were male boards of sister-run institutions. Sisters who cared for orphans and staffed other social service institutions had much less autonomy than hospital sisters. They struggled for funding and often had to wrestle with lay or diocesan boards and battle with laymen over control and autonomy.

The history of the Catholic Boy’s Home in Minneapolis provides a microcosm of the many types of tensions that resulted from gender politics. In 1878 Bishop John Ireland and a group of Catholic laymen established a corporation and officers to begin a new boys’ orphanage in the city. Deciding to take “ultimate responsibility for construction and maintenance of the institution,” the laymen asked the CSJS to staff it. From the beginning the CSJS were expected to share expenses, although the mother superior was never invited to the board meetings and was expected to submit written financial and statistical reports. Board members made inspections to “investigate the condition of things,” and eventually there were “clashes of authority” between the female superior and the laymen, who accused her of “usurping functions of the board.” Wanting to reassert their authority but obviously intimidated by the religious status of the nuns, the board members agreed to “visit the asylum in a body” to acquaint the “Matron” with “business principles.” Even after the visit of the “irate gentlemen,” the mother superior continued to exercise authority; in response, the men terminated the sisters’ salaries. The superior then billed the board $1,200 for services rendered in 1888. Frustrated, the laymen asked Bishop Ireland to intervene with the sisters.

The board members continued to struggle to fund the institution adequately, so they asked their wives to organize fund-raisers for the orphanage. The laywomen organized many successful “orphan’s fairs,” and the proceeds along with the sisters’ soliciting provided the major funding for the institution. Looking for a way to cut costs and fearing the sisters were being duped by irresponsible parents, the board wanted to take control of the admission policy. They requested that the superior refuse to take children who had any living relatives and that she send the board monthly acceptance reports for their perusal. Incredibly, when a physician requested money for “electric treatments” for one of the boys who had a “hip disease,” some board members asked the doctor to consider amputation of the limb to limit the cost. By 1894 board attendance had dwindled so severely that Bishop Ireland and the remaining laymen dissolved the corporation and transferred control to the diocese.

105The twentieth-century trend toward diocesan centralization and control by bishops as well as the secular expansion of state and city charity boards and accrediting agencies effectively limited the participation and activity of Catholic laity. In the early twentieth century American bishops began to consolidate their authority within their dioceses, which, in effect, reduced the autonomy and control of the laity over their benevolent activities and monies. Mary Oates has stated that bishops tended to be suspicious of organizations they did not direct and that any organization that wished to be termed “Catholic” had to obtain episcopal approval. Although diocesan centralization may have been financially expedient, it also had a dampening effect on local lay interest and initiative. In essence, it placed all benevolent societies, male or female, in an auxiliary role and gave bishops and priests leadership and monitoring authority over charitable institutions within the diocese.

106Besides accepting clerical control, local laity who had helped support Catholic hospitals and social service institutions for a century had to submit to the authority of the “cult of professionals” and their move toward “scientific charity.” To gain respectability in the Protestant mainstream, Catholic charity boards attempted to mimic centralization practices by forcing laity and communities of women religious to subordinate and centralize their activities under diocesan or national boards controlled by clergy and educated laymen. This had a particularly limiting effect on Catholic laywomen, who had worked extensively to support local charities and who found themselves not only restricted by gender but by educational status as well. Laywomen who had worked closely with the sisters on many projects were ignored and their activities marginalized as highly educated professionals, business men, and clergy provided the “public voice” for Catholic charity.

107Struggling to work within the growing professional world of health care and social service, CSJS and other sisters were also affected by diocesan centralization and the growing control of secular and Catholic accrediting boards. Perennially dealing with the dichotomy between religious selfeffacement and humility and secular professionalization and achievement, nuns struggled to live in both worlds within religious and gender constraints that, at times, must have seemed irreconcilable. The sisters’ various roles in hospitals, particularly as superintendents and supervisors, their financial independence, their working relationship with male doctors, their increasing educational status, and their stronger presence on both Catholic and secular professional boards helped them maintain more control and autonomy over their hospitals.

108 Sisters in social service, on the other hand, struggled with funding limitations, lack of educational opportunities, and their growing dependence on institutional boards comprised of laymen or priests. These factors made them more vulnerable than hospital sisters to limitations imposed by secular regulations and paternalistic Catholic charity boards that more and more relegated the sisters to nonpaid or low-paid “employee” status similar to that of parish school teachers.

By 1920 the activities of American sisters had made a significant impact on the expansion of American health care and social service. Although they would never rival the CSJS’ and other sisters’ contributions in education, sister-run hospitals, orphanages, and support services for women and families provided an extensive support network and “safety net” for immigrant and working-class Catholics in the United States. A centuries-old tradition of collective living, a vowed life, and a variety of charitable activities made American women religious natural players in the expansion of female-dominated institution building in the nineteenth century. The sisters’ expanding activities in health care and social service helped support and shape Catholic culture and American life well into the twentieth century.