6

THE COLORED DOLL IS A LIVE ONE! MATERIAL CULTURE, BLACK CONSCIOUSNESS, AND CULTIVATION OF INTRARACIAL DESIRE

If, perchance, a black . . . doll finds its

way into [the] home . . . [a] child’s first

impulse is either to discard it . . . or

make it the servant of [a] white doll.

Thus . . . is the baleful work of slavery

made evident.

—Nathan B. Young,

A.M.E. Church Review (1898)

No toy you can buy for a small

colored girl will instill more of self-respect

in her—unconsciously—

than a colored doll. Burn up the

others.

—“Negro Dolls,” Christian

Recorder (1921)

Because of a doll, six-year-old Maud Evangeline Gary had an auspicious future ahead of her—at least her mother believed that this was the case. Maud Gary’s doll was ordinary in many respects: it was clothed, had combable hair, and was roughly the size of a small toddler. Maud likely spent hours on end playing with the companion “she love[d] very dearly”; the little girl might have taken her playmate with the pleasant, welcoming face nearly everywhere she went. Whatever she did with her doll, Maud probably did not suspect that her mother had an ulterior motive for giving it to her. Her mother confessed, “I do not allow her to play with [white] dolls only [those] of her own race. I am trying to make her a race woman by daily teaching her to love whatever belongs to the colored race. . . . The only way to make race-loving men and women is to start in early childhood.” For Maud’s mother, the important thing was not that Maud adored her toy but that the girl played with a colored doll: a colored doll kept her daughter out of city streets, a colored doll taught “race love,” a colored doll would help ensure that Maud grew up to become a respectable woman partnered with a black man. Maud’s acquisition of black consciousness went beyond the dolls that she cradled. Her mother was additionally convinced that “every mother should surround their children with pictures and literature of our race.” Maud Gary, then, was surrounded by a comprehensive home culture built upon race pride, objects reflective of Afro-American ability and appearance, and conscious effort to foster intraracial desire.

1Maud’s mother was so certain that such race training gave her daughter a decided edge in life that she decided to enter the little girl in a “better babies” contest. Sometime during July or August 1915, she composed a hope-filled letter, tucked a snapshot of daughter and doll into an envelope, and sent off her entry to the contest sponsor, the New York

Age. Part beauty contest, part eugenic undertaking, the

Age’s better “baby” initiative focused upon infants as well as children up to the age of twelve. The

Age proudly announced that the contest showcased “future men and women of the race” as it encouraged black parents to take an interest in the “sanitary and hygienic precautions” that constituted the recently defined science of “baby culture.” The leading Afro-American newspaper endeavored mightily to make mothers and fathers more mindful of their children’s diet and exercise. Readers were quick to respond to this strategic initiative by sending letters, entries, and feedback to the

Age. Shortly after Maud’s picture and her mother’s letter were published, another

Age reader enthusiastically wrote the paper in order to endorse the use of “Negro dolls,” “colored pictures,” and “Sunday School cards representing colored characters” as a means of ensuring that African Americans understood eugenics entailed “race pride.”

2 For this reader, a consciously eugenic version of race pride produced better children, strengthened Afro-American identity, and enabled a positive collective destiny.

The story of Maud Evangeline Gary and her doll reflects a historical moment when African Americans—especially aspiring, middling, and elite people—considered the steady proliferation of healthier home environments and “better babies” within black communities as evidence that the race had made spectacular strides since emancipation. But Maud’s story is part of other tales as well. As a child born in the first decade of the twentieth century, Maud Gary was playing with toys during an era when race reformers turned their attention to children, when black consciousness assumed new salience among aspiring-class women and men, when reformists viewed proper conduct as essential to race progress. Maud Gary carried around her doll at a time when race women and men made a connection between the toys with which children played and their impending entrance into adolescence, sexuality, and mate selection. And, Maud’s mother was a consumer who consciously decided to purchase a “colored” toy at a time when aspiring and working-class African Americans had more expendable income and access to mass-produced goods.

Demographic developments were partially responsible for the very appearance of material culture aimed at and produced by African Americans. Urbanization after the turn of the century provided better labor opportunities that, in turn, increased the number of African Americans with expendable income. Growing black literacy rates additionally expanded the market for race products in that once more children, women, and men could read billboards and print ads, then more people were likely to consider buying race literature and other forms of black material culture. Advertisements in race publications therefore reached an increased number of potential buyers as the percentage of literate black women, men, and children surpassed 50 percent during the early decades of the twentieth century. These advertisements did more than sell commodities: they promoted race pride and, at times, peddled ideas that neatly meshed with reformist discourse about black domestic spaces. Many of these same advertisements tried to convince potential buyers that specific items were essential for the proper home training of black girls and boys.

If advertisements were critical to the emergence of black consumer culture, consumer culture itself was contingent upon technological advances. Technology facilitated the manufacture of affordable mass-market goods, goods that increased the production of advertising. Critical technological advances in mass printing and innovations in advertising—refinements in lithography that led to the explosion of colorful trading cards during the 1870s and 1880s, greater reliance on memorable slogans and copy during the 1880s and 1890s—made products seem all the more appealing and enticing.

3 It was not until the early twentieth century, however, that AfroAmerican publications and the advertisements in them became more visually sophisticated. Not only did ads with better graphics help generate a niche-market of African Americans but that niche market appeared toward the end of a period in which technology greatly expanded consumer culture in the United States.

Late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century U.S. consumer culture was rife with derogatory portrayals of black people on trading cards, on packaging, and in the form of toys, souvenirs, stereographs, and everyday articles. Since African Americans generally found these items distasteful if not harmful, many black women and men felt the need to counteract offensive images and objects with items that promoted pride, self-love, and black consciousness.

4 One such race woman in Chicago, a Mrs. Mack, penned a purposeful missive to the

Half-Century in which she championed objects of race pride:

White people do not fill their houses with pictures of Colored people. ... They cover their walls with pictures of their own race. If, occasionally they do use a picture of a Colored person it is usually in a ridiculous role ... or doing menial labor. . . . At present I have no pictures on my walls ... that haven’t Colored people in them. And I don’t allow a ridiculous picture of a Colored person in my house. . . . I have purchased pretty Colored dolls for my children so that they will learn to love and respect heroes and beauties of their own color.

Suggestive in its implication that limited, unflattering, or denigrating depictions of Afro-Americans were just as, if not more, damaging than the absence of positive images, Mack’s letter underscored that “colored” material culture stood counterposed to the “menial” and the “ridiculous,” which for Mack included both “eating watermelon” and outlandish dress. This juxtaposition on her part powerfully emphasized the fact that race consumers had options—options that at once uplifted the collective and challenged the problematic. And when Mack urged other

Half-Century readers to pressure shops into stocking “beautiful Colored pictures” and to consider seriously giving their children “Colored dolls,” she articulated specific ways in which black women and men could simultaneously empower themselves and shape their children’s most personal and deep-seated tastes, preferences, and cravings.

5Mack’s own wish for her children—and other race children, for that matter—to “love and respect their own color” was as much reflective of race pride as it was indicative of a broader concern with child’s play among individuals concerned about the future of African Americans. Race-conscious individuals put aside nickels, dimes, and quarters in order to purchase the new “colored” pictures, books, and toys as activists and parents offered pointed rationales for why these items were necessary. Whereas race activists considered a range of material culture beneficial, one object in particular was accorded a unique transformative power in enabling children to become race-conscious adults who would go on to produce their own upright offspring. As the twentieth century opened and progressed, both aspiring and “representative” women and men believed that children could learn life lessons without being endowed with precocious knowledge, that material culture could simultaneously serve the goals of home training, “race” training, and the disciplining of desire. For reformers and parents who believed that playthings could have a decisive impact on the minds, bodies, psyches, and predilections of children, dolls were unrivaled in their ability to shape collective destiny.

Material culture and race consciousness converged with a reformist preoccupation over sexuality to make the colored doll an exemplary racial tool —one that ostensibly supported Afro-American industry, facilitated self-love, and enabled proper intraracial conduct. Dolls became possessed with a power to influence children’s sexuality and eventual sexual preferences: reformers imbued them with eugenic properties and the ability to ensure racial purity; one educator claimed that dolls could help reduce or even stop lynching. In order to understand why educators, reformers, and parents forged provocatively potent connections between material culture and sexuality, dolls and racial reproduction, toys and collective well-being, it is necessary to reconstruct the history of the inanimate, sepia companions that little girls like Maud Gary caressed and cherished.

During the early twentieth century, black reformers considered the placement of certain forms of material culture within domestic spaces to be a symbol of collective progress. Ideally, for purposes of racial uplift, homes were supposed to be classrooms providing constant instruction to children through an array of examples disseminated by thoughtful parents and adult relatives. Just as churchgoing folk might imbue religious faith in their daughters and sons or education-minded people might inspire members of their household on to academic achievement, chaste mothers and fathers allegedly set the moral compass of children. Spiritual guidance, ambition, and restrained sexual behavior were valued within a range of black households, including the homes of aspiring, middling, and elite race families. For many of these families and for more than a few reform-minded race activists, home life and collective progress were more than connected: collective progress was all but contingent upon domestic uplift. Given that the bulk of black reform discourse demonized certain domestic arrangements—especially crowding and boarding—for their supposed detrimental impact on sexuality, it is not surprising that race reformers believed home training should account for sex, sexual ethics, and reproducing the collective.

According to this vision of black advancement and racial destiny, the domestic sphere was one sphere over which African Americans exacted some measure of control. Destitute, struggling, working-class, and aspiring-class parents could all strive to provide their children every advantage within their means; every parent could do

something to enrich the home environment. The seemingly simple task of hanging “a few good pictures” of prominent Afro-Americans on one’s walls could enable children in the lowliest homes to learn about the race’s achievements.

6 If what the race’s youth learned at home had broad implications and if domestic spaces were seats of learning, then material culture within those spaces would facilitate uplift, progress, and, indeed, self-love. The mere ability to purchase material culture was, however, largely restricted to households with at least a modicum of expendable income—those households composed of solid working-class, middling, and representative families.

The presence of material culture in domestic spaces gained new significance for black women, men, and children around the turn of the century. Activists and advertisements alike claimed that items featuring AfroAmerican images, leaders, and achievement brought “a gleam of joy . . . [to the] eyes,” imparted a “new hope . . . [to the] soul,” and made “the heart of every race-lover beat faster.”

7 Books were cherished since literacy was closely associated with collective progress. Race reformers thus promoted books as a potent tool in the crusade to uplift, enlighten, and transform the black masses. Although these reform-minded women and men typically realized that working black families might not have the resources to purchase books, their realization was usually overwhelmed by their conviction that black mothers and fathers were duty-bound to place race literature in the home.

In 1902, for example, race woman Julia Layton Mason advised black parents that “no matter how humble [their] home” they should nonetheless “strive to start a good library . . . [and] secure the books that have been written by our own people.” Similarly, a 1906 advertisement in

Voice of the Negro urged every “Negro family in the South” to obtain their own copy of the pricey, four dollar

Afro-American Home Manual: not only did this “grand” morocco-bound volume “dea[l] with topics of vital interest to the colored people,” its pages were filled with “timely and scholarly articles” intended to educate race readers.

8 Books were valued for their contents and for what they could teach, but they were also important—to both reformers and willing, able buyers—as objects that represented black aspiration and ability. Along with other forms of material culture in the home, books were a representative item that could uplift an individual who both possessed a longing to be transformed and an urge to support “authors . . . of our own flesh and blood.”

9 As with Afro-American conduct tracts and manuals, race literature sought to reproduce class-bound values; while conduct literature stressed behavior that mirrored restrained, ostensibly bourgeois sexuality, race literature promoted a range of achievement that might lead to class mobility.

Mobility and progress were contingent upon race literature in the eyes of writer-physician Dr. Monroe A. Majors. In 1918, the author of

Noted Negro Women: Their Triumphs & Activities contended that race women and men should endeavor to “make a few big authors and poets of our own”; he maintained that production of history texts was “essential . . . in the formation of races.” As much as Majors considered it imperative for black Americans to buy and read race literature, he also believed that Afro-American texts—the “rich fruit of . . . race heritage”—would fail to realize their full potential without “a deal of race pride to go with them.” Books were certainly critical agents in terms of what they could instill and in their ability to influence readers’ self-image, thought, consciousness, and conduct. Still, as Majors pointed out, books alone did not generate “better pride.” Race pride was additionally produced through environment and representations; race pride was inculcated in children through nurture, education, and play. More than a decade before Majors equated race pride with African Americans “occupy[ing] their place in the circle of nations,” activists considered how nurture, education, and play shaped girls, boys, and collective destiny. And, if Majors focused on literature, poetry, and history during the 1910s—a time when history became professionalized among African Americans—some of his immediate activist and intellectual predecessors developed an allied preoccupation with dolls.

10Black Americans were cognizant of the varied potential of dolls as early as the 1890s. For example, during an 1891 tour of Sierra Leone when AME bishop Henry McNeal Turner noticed that the only dolls available had white faces, Turner concluded that exciting market possibilities existed for black American innovators willing to produce the “millions of colored dolls” sought by “African ladies . . . want[ing] black, brown, and yellow dolls.”

11 Others would, in time, share Turner’s belief that black dolls could play a key role in economic self-determination. Most Afro-American women and men who promoted colored dolls before 1910, however, echoed lawyer Edward Johnson’s sentiment that dolls were an integral part of “spur[ring] our race to properly teach itself.” If, as Johnson put it in 1894, the prevalence of “bad representations” made the need for positive images pressing, then it was of utmost importance for black girls and boys to be given toys and texts that “correspond[ed]” with the actual achievements, conditions, and appearance of the race. Within four years, one of Johnson’s contemporaries, Nathan Young, was relieved that race parents were “wisely beginning” to place “Negro doll[s]” in their homes for the “edification” of children.

12The importance that Johnson and Young attached to dolls as means of socialization placed both men within a larger cultural trend. If, by the 1890s, the antebellum view that dolls were practical tools that helped girls learn to sew had subsided, white middle-class parents increasingly believed that dolls helped girls “imitate social ritual[s] of polite society.” Adults in the United States—specifically white women doll makers, maternalists, and reformers—actively began to promote dolls as a means to instruct children about “social relationships.” Adults increasingly assumed that children formed emotional attachments to dolls as well. Changes in doll production enabled this shift on the part of adults and children in that the “progressive juvenilization in . . . dolls’ appearance” that occurred over the latter nineteenth century made it more likely that children would actually identify with these particular toys. As adults came to expect that most forms of child’s play with dolls mimicked parenting and fostered desires for domesticity, children were increasingly encouraged to engage in a fantasy life involving dolls. With a little imagination, girls could become little mothers and boys little fathers as their nurturing arms transformed dolls into “babies.” Doll play became all the more associated with gender role socialization in the process: both girls and boys acted in nurturing—and aggressive ways—toward dolls, yet “boys often assumed authoritative public roles such as doctor, preacher, and undertaker to sick, dying, and dead dolls.” Dolls were associated with domesticity, then, but they also assumed significance as implements that guided children as they learned to negotiate intimate relationships, gender performance, and social roles.

13Changing beliefs and expectations over the function of dolls within the broader culture informed Afro-American discourse in provocative ways. Race-conscious individuals such as Edward Johnson and Nathan Young became more explicit—albeit incrementally—about what they believed dolls could accomplish. Johnson himself, who by 1900 had produced a history of African Americans for school children as well as an account of black soldiers in the Spanish-American War, returned to the matter of what dolls could do for race children in 1908. In an article entitled “Negro Dolls for Negro Babies,” the lawyer cum author opined that “one of the best ways to teach Negro children to respect their own color would be to see to it that the children be given colored dolls. . . . In most cases they prefer white dolls . . . but this idea could easily be removed. . . . To give a Negro child a white doll means to create in it a prejudice against its own color, which will cling to it through life.” More than inconsequential child’s play, the use of white-skinned dolls “sow[ed] . . . seeds of discontent” and bred self-loathing that irrevocably warped black children’s outlook. Self-hatred hindered race progress; hatred of one’s complexion translated into the inability to be attracted to somebody else of similar hue. Without saying as much, Johnson was able to get the message across that learning to “respect [one’s] own color” during childhood was intimately tied to the eventual selection of sexual partners. His text mentioned neither illicit interracial sex nor so-called bastardization, yet provocative insinuations were nevertheless shot through his text: all one had to do was ponder the full implications of self-hatred implanted at an early age.

14Johnson’s article in the

Colored American was published just as race-conscious women and men were beginning to rally around the notion of black dolls for black children. Before 1900, dark-skinned dolls, in and of themselves, did not possess automatic appeal among black children, let alone their parents. Stereotyped images and normalized portrayals of black women and men as servants were so ubiquitous that realistic toys produced in the United States that approximated the actual appearance of African American children were at once novelty and rarity.

15 For black parents who possessed expendable income to purchase toys, choices were few: either white-skinned dolls or “‘Darky Head,”’ “‘Mammy,”’ “‘Topsy,”’ and “‘Dusky Dude”’ playthings provided by factories and department stores catering to mainstream tastes.

16 Undoubtedly, a people barely two generations removed from bondage did not relish the idea of their children playing with what were essentially kerchiefed plantation figures and, even worse, “demon[s] or caricature[s].”

17Homemade dolls were always an option since women—black and white alike—produced black rag dolls. Whereas middle-class white women doll makers in the United States produced black dolls during the late nineteenth century, these dolls tended to be “mammy” and “servant” rag or stockinet dolls that were considerably popular among middle-class white children.

18 The rag dolls that black mothers produced for their children were likely well-used and cherished items. Yet, if African American children and parents were going to reject commercial white dolls, attractive black ones needed to be mass-produced and the reasons for purchasing these new dolls sufficiently dramatized.

The artistic and technological development that enabled production of mass-market, lifelike colored dolls did not occur in the United States but in Europe. During the late 1880s, German doll makers began using unglazed porcelain, which is known as bisque; they modeled dolls’ features from life, used an array of brown tints, and pioneered the mass production of attractive, lifelike colored dolls. German factories did indeed produce stereotypical black dolls during this period, but nonetheless, their innovations resulted in the creation of dolls that resembled African American children.

19 When realistic colored dolls finally emerged on the U.S. market around the turn of the century, then, most were imported from Europe. U.S.-based E. M. S. Novelty Company, for example, sold imported colored dolls during the 1910s for use in “emancipation celebrations, bazaars, fairs.”

20 Since U.S. doll makers would not match the technological and aesthetic innovation of German companies until World War I, those African Americans who sold commercial colored dolls during the early decades of the century often went through considerable efforts to import their product.

The mere existence of lifelike colored dolls hardly ensured that they would become familiar and coveted items in black households, however. Imported dolls of any hue were expensive, therefore middle-class and elite consumers, the majority of whom were native-born whites, were their primary purchasers. Working-class children—especially the sons and daughters of immigrants—played far less with commercially produced dolls because their parents generally could not afford them. Similarly, for African Americans, imported as well as domestically produced dolls could carry a “prohibitive” price tag.

21It took initiative on the part of one of Afro-America’s largest institutions to make colored dolls more accessible to black consumers and to popularize the notion that colored dolls shaped black children’s self-esteem. Shortly after the turn of the century, the National Baptist Convention (NBC) launched several efforts to promote colored dolls.

22 Black Baptists first passed a resolution in 1908 encouraging members of the denomination to give children nothing but brown-skinned doll babies. Baptist women began organizing “‘Negro Doll Clubs”’ around 1914; along these lines, the NBC sponsored well-timed “doll bazaars” for the Christmas trade. Black Baptists also owned and operated the National Negro Doll Company (NNDC), which opened in 1908. The company sent at least one representative on a promotional tour around the United States, while company president Richard H. Boyd did some traveling of his own by crossing the Atlantic in order to establish business relationships with doll makers in Germany. While in Europe, Boyd either procured dolls or learned about manufacturing high-quality bisque products; Boyd likely accomplished both tasks, since the NNDC eventually manufactured their own product from their Nashville headquarters.

23The

Age proclaimed the National Baptist Convention’s sundry efforts to promote colored dolls “a timely and mighty step in the right direction.” Not only did celebration of the race’s likeness mean certain progress for black Americans, such a “sensible change in Negro sentiment for Negro toys and ornaments w[ould] profoundly affect Negro nature.” The

Age editorial further commented that the NBC’s endeavor would have a stronger impact on home training if used in conjunction with race pictures and calendars. In one brief news item, the

Age advanced key concepts about home life and its components: images and items contained within households shaped “Negro nature”; those same images and items possessed the power to alter the race’s overall sociopolitical trajectory.

24When the Age additionally decried unwitting promotion of “foreign standards of beauty and culture,” it pointed to the attendant pitfalls awaiting young folks without making any direct reference to gender. Danger presumably existed for both sexes. Prizing whiteness might result in girls succumbing to white men’s flatteries, while boys might develop a risky preference for white females. The underlying message, then, was that something as simple as a doll could reduce concubinage, miscegenation, black-on-white rape, and lynching. The paper did not specifically mention sex, but just as Edward Johnson spoke volumes through carefully crafted prose, the editorial subtly communicated the message that race dolls were particularly powerful toys.

The NNDC publicized its own claims regarding the potent utility of colored dolls. NNDC advertisements suggested that if other races were “teach- [ing] their children . . . object lessons” through dolls, then dolls would enable black children’s “higher intellectual” development as well. The company’s illustrated brochures proclaimed that “our dolls vividly portray the smart set, as is often referred to in society and news items.”

25 As the NNDC would have it, their dolls had three distinct properties: they shaped children’s thinking, fostered respectability, and provided a class-based example of what the race could achieve. By pricing their toys as low as fifty cents and one dollar, moreover, the NNDC placed colored dolls within closer reach of aspiring families. Lower-end NNDC dolls were not necessarily cheap, but they were certainly less expensive than other commercial dolls, both imported and domestic.

26Over the course of the 1910s, the NNDC began to have competitors as a range of companies—white-owned as well as race-operated—plied their wares on the pages of Afro-American publications. The E. M. S. Novelty Company tried to lure customers by announcing to

Crisis readers that “THE COLORED DOLL IS A LIVE ONE.”

27 Both Gadsden Doll Company and Berry & Ross advertised in the

Crisis as well as the Chicago

Defender. Gadsden Company ads made no mention of whether the company was black-owned or -operated; Berry & Ross, however, was a race concern that produced dolls fashioned by its two women founders, Evelyn Berry and Victoria Ross.

28 Another Afro-American woman, Theresa Cassell, headed the Chicago-based National Colored Doll and Toy Company (NCDTC). Significantly, many of these companies appeared on the scene during and immediately after World War I, when imported colored dolls became difficult, if not impossible, to procure. The NCDTC, for one, experienced problems with its “source of supply” during the war, yet the company was able to stay in operation all the same. In July 1919, the

Half-Century—where the NCDTC advertised—featured a profile on Cassell in which the magazine noted the entrepreneur’s conviction “that Colored children should be taught to cherish the . . . beauty of a brown skin . . . [and] the wave of curly hair.” One of Cassell’s supporters, Evelyn Jones of Tulsa, promptly wrote in to the

Half-Century to praise the magazine for drawing race consumers’ attention to the NCDTC. Jones informed other

Half-Century readers that Tulsa’s blacks were swayed by Cassell’s vision and efforts; she also confessed that her own baby “crie[d] all the time for a New ‘Tolored’ Doll” from the NCDTC.

29One of the attributes that made Gadsden, Berry & Ross, and NCDTC dolls “live” was their resolute rejection of stereotype. As one Berry & Ross advertisement put it, New Negroes did not want “old time, black face, red lip aunt Jemima colored dolls but dolls well made and truly representative of the race in hair and features.” Alvah Bottoms of Chicago concurred. She was appalled by “‘dancing coon”’ and “‘Aunt Jemima”’ toys that reinforced notions that “all colored men are fit for is to . . . amuse white people . . . [and] colored women are fit only for servants.” At a time when racist portrayals of African Americans were all too common in the United States, at a moment when black consciousness was on the rise, colored dolls and the companies that made them were in vogue. That vogue was no meaningless fad.

30

In addition to colored dolls appealing to race-conscious individuals for what they were not, the message that such dolls were synonymous with respectability would have been especially attractive to urban aspiring-class parents. This group of mothers and fathers was most likely to be concerned with the detrimental impact that employers, boarders, and street denizens might have on their children’s sexuality. Working parents could not be sure about the nature of their children’s interactions with other adults, but they could counteract environmental stressors by placing certain objects within the home. Giving a black child a black doll might not prevent that child from being molested by an adult, but it might keep that child from seeking intimate relationships with whites upon reaching sexual maturity: a black doll might keep a daughter from succumbing to the advances of an employer, a son from indulging in pleasures offered at black-and-tan watering holes. The benefit of black consciousness for the working and aspiring class, then, was that racial sensibilities might help future race women and men resist interracial sex and remain within the bounds of respectability.

Colored dolls found an unlikely champion in a relatively obscure black educator from Oklahoma named J. H. A. Brazelton. An ardent believer in developmental psychology, Brazelton was sufficiently concerned about the current cast and direction of racial reproduction that he self-published

Self-Determination, The Salvation of the Race in 1918. With a frontispiece bearing the likeness of Thomas Jefferson, his book touched upon subjects ranging from segregation and disfranchisement to the Spanish-American War and the Great War. The most striking feature of

Self-Determination was its unrelenting insistence that domestic influences and material culture decided the race’s future.

31Self-Determination was as much a “plea for character building in our race-variety” as it was a treatise on how Afro-Americans should maintain ethnic distinctiveness: “I am trying to show . . . that black children are born with honor and integrity; that our mothers, not thinking psychologically and sociologically, take away the honor and integrity of our children by . . . certain devices in the cradle. . . . Heredity counts for naught in these matters ... and ideals count for everything in the history of a race-variety. So, if we want honor and integrity in our race-variety, we must begin in the cradle to fix the next generation.” Although Brazelton recognized that structural conditions forced many adults to expend considerable energy on the material support of their families—which meant, of course, that they spent limited time at home—he still believed that parents needed to seize control of domestic influences. Schools and teachers might possess the power to correct “the faults of . . . Afro-American homes,” but the obverse was just as true: a dubious home life could obliterate progressive strides acquired through education. Public education could also backfire. According to Brazelton, standard textbooks that lionized the exploits of white Americans subjected black children to “spiritual slavery”—he even believed textbooks had a hand in “maintain[ing] illegal amalgamation.” If the race was going to sustain itself, its distinctiveness, and its honor, home life had to be carefully administered.

32

Proper administration of the household required use of race images, texts, and “devices,” namely dolls. Believing most ethnic groups partook in material culture that reflected themselves, Brazelton unfavorably compared black Americans to Puerto Ricans and Filipinos who, although colonized, allegedly had the foresight to “use their own dolls.” Brazelton offered no real proof that residents of U.S. territories either possessed or created hued dolls. Concrete evidence was beside the point, however: the mere implication that African Americans lagged behind other peoples mattered most. Such comparison made the race seem retrograde and suggested that failure to remove white dolls from black homes resulted in diminished probity of children who already belonged to a people considered morally suspect in mainstream society. In other words, no one could afford to underestimate the power of a seemingly benign toy since something as simple as a doll could prevent collective advancement.

33For J. H. A. Brazelton, dolls were a “powerful . . . silent force in the world” that should, in their own right, be looked upon as “children . . . [and] the monuments of our souls.” His poetic turn of phrase likening dolls to babies offered the compelling suggestion that children viewed dolls as friends, loved and cherished them, considered them daughters or sons when playing house. Since girls and boys developed deep attachments to these companions in miniature, once an Afro-American child began to “love and embrace” a white doll, God-given integrity diminished along with a “desire [to] . . . live forever.”

34Self-Determination and self-preservation were one and the same for the teacher from Oklahoma. With his conviction that material culture enabled black children to perpetuate and build up the race, Brazelton went so far as to argue that dolls possessed a eugenic component which helped remove “defects of body and sense-organs.”

35 This argument on Brazelton’s part was similar to earlier contentions by white women doll makers—including Martha Chase, who produced Chase Sanitary Dolls—that dolls could help “‘produce a generation of Better Babies”’ through promoting scientific motherhood along with health and domestic hygiene.

36 Brazelton, like other reform-minded African Americans, drew from eugenic discourse in order to connect children’s weal to racial health.

Brazelton departed somewhat from the argument offered by Chase and her maternalist contemporaries, who tended to view dolls as a means “to teach infant hygiene to working-class mothers and their children.”

37 Brazelton neither discussed whether dolls could shape black women’s hygienic habits nor did he stop at claiming that the eugenic benefits of colored dolls were limited to dolls’ purported benefit to their possessors’ bodies. Dolls, Brazelton maintained, played a key role in shaping racial reproduction and determining race purity. Brazelton summoned compelling language to declare “the Afro-American doll . . . a double-barrelled shot gun that will destroy in PEACE both illegal amalgamation and the first cause of lynch law.” For him, miscegenation was slow, creeping genocide: “According to the census of the United States, there are 3,000,000 mulattoes in the country today. ... We shall have to wait for the next census to find out whether . . . the rate of increase of mulattoes is greater than the rate of increase of blacks. ... I want the integrity of my race-variety sustained to the eternities. . . . I want illegal amalgamation stopped now.” With his concerns about racial reproduction, Brazelton was quick to name whom he felt was ultimately responsible for such an alarming state of affairs—African American mothers. He insisted that too many mothers failed to realize that infants possessed an innate craving to “see continued existence,” thus they unwittingly warped impressionable little minds by foisting white dolls upon their tykes. As far as Brazelton was concerned, black mothers created children who craved whiteness from infancy and would continue to do so upon reaching sexual maturity.

38What Edward Johnson gently inferred and the

Age quietly intimated a decade earlier, J. H. A. Brazelton boldly stated: black dolls ensured racial purity. Whereas neither Johnson nor the anonymous editorial writer specified how doll play affected either sex, Brazelton proposed that dolls shaped the sexuality of the entire race.

Self-Determination implied that dark-skinned dolls imbued little girls with the wish to become mothers of their own sepia-toned babies, that they primed infant boys to value blackness. As if to underscore that both sexes did indeed play with dolls, the Oklahoman alternated between gendered pronouns in his text as he connected toys, home training, and predilections for interracial sex. In the course of doing so, he reproached women for their alleged role in perpetuating miscegenation. And, whereas Brazelton drew upon statistics compiled by Afro-American sociologist Monroe Work to substantiate his own assertion that 75 percent of those lynched were actually “charged with offenses other than that unmentionable crime,” Brazelton nonetheless maintained that black-on-white rape motivated the practice of lynching. Brazelton also concluded that misguided home training induced the remaining 25 percent to assault white females. Accordingly, he implied that if black parents could not prevent mob violence from affecting their families, they could at least make sure that their sons were not exposed to rosy-cheeked, flaxen-haired dolls.

39Brazelton rendered his argument in such stark fashion to arouse a sense of urgency in his readers. Who, after all, would want to risk giving their son a toy that might ultimately lead to his murder? What decent parent would want his or her own carelessness to result in a daughter seeking illicit interracial sex? Brazelton expected his audience to be aspiring-class people like himself, and he therefore addressed their anxieties as well as their hopes. He realized that the many African Americans who led somewhat tenuous lives wanted to bequeath an honorable heritage to their children, if nothing else. Put another way, parents who could not afford a commodious home might be able to put aside a few pennies at a time and eventually buy their child a “Negro doll” for twenty-nine cents.

40 Domestic material culture certainly took other forms—such as race histories, novels, and portraits—but dolls played a particular role in black home reform in that they ostensibly had a direct influence on morality, sexuality, and racial reproduction. As J. H. A. Brazelton endeavored to suggest, dolls could prove just as critical as separate bedrooms when it came to home training and morality.

Brazelton was more than a lone voice out in Oklahoma. He embodied a growing sentiment among aspiring women and men who consumed African American material culture after the war; his arguments came during a period of especially prominent display and availability of Negro dolls. As a major Afro-American periodical observed within two years of the publication of Brazelton’s book, black dolls were “fast becoming the fashion among our people.”

41 This “fashion” was evident in race publications with aspiring, middling, and elite readership. The

Half-Century ran a photograph of a little girl and her little brown doll on its cover in 1920. Almost three years later, the

Half-Century’s cover for its November-December issue, provocatively captioned “Her Choice,” featured a race girl lovingly cradling a race doll in her arms—as a rejected white doll lay askew at the child’s feet, no less. The growing visibility of black dolls was supplemented by African Americans’ interest in doll making as a fortuitous opportunity to cultivate black consciousness and turn a profit. North Carolina’s Afro-American Novelty Shop of Wilmington attempted to win customers with ad in the

Competitor promoting itself as the “only colored wholesale and retail doll mail order house in this section.” Berry & Ross pitched their “Famous Brown Skin Dolls” on numerous levels to

Defender readers: the Harlem-based firm claimed that their products encouraged self-love in children, provided economic self-determination for adults, and offered significant employment opportunities for black women. Parents could also purchase ten-dollar shares for their children—on the “Liberty loan easy payment plan,” no less. The company even promoted Victoria Ross and Evelyn Berry as role models that could help children realize “the real value of Negro industry to the Race.”

42

Advertisement for Berry & Ross, Inc., Chicago Defender, April 5, 1919. Started by two African American women and eventually connected to the Universal Negro Improvement Association, Berry & Ross ingeniously promoted “colored dolls” by associating their product with “sound” financial, industrial, familial, and racial investments. Courtesy of General Research and Reference Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Other outfits, including New York City’s Otis H. Gadsden Company, packaged their dolls as part of a larger project in race pride, one that incorporated portraits of black soldiers and calendars featuring children “for home use.” Chicago’s National Colored Doll & Toy Company even tried to entice little boys by advertising toy replicas of World War I helmets along with miniature toy gas masks. Any lucky boy who managed to save up $1.35 could imagine himself “go[ing] over the top” just like the 369th Colored Infantry, whose heroic efforts in France earned them both the nickname of the “Hell Fighters” and the coveted Croix de Guerre. Therefore, by marketing toy war paraphernalia, the National Colored Doll & Toy Company could capitalize on the 369th’s fame and recoup wartime losses at the same time that little boys could imagine themselves ferocious warriors and race heroes.

43Dolls and other forms of material culture that reflected race pride assumed various meanings and uses, some of which were explicitly political. One of the largest political movements ever among African Americans—among members of the greater black Atlantic community, really—advocated black dolls during the 1920s. Members of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) considered black dolls integral to realizing the goals of black nationalism, and Garveyites pushed dolls in connection with their larger cultural program. When, for example, the UNIA staged an Educational and Commercial Exposition in 1922, the association announced that it would distribute black dolls to winners of its better babies contest.

44Moreover, Garveyites such as Estelle Matthews held convictions strikingly similar to those of J. H. A. Brazelton. Matthews, the Lady President of her division in Philadelphia, begged mothers in the movement to realize that they held the very destiny of the race in their hands. Matthews stressed that a good “race mother” was a vigilant molder of children’s minds:

You talk race purity, and yet, by the white pictures on your walls . . . you are teaching your children to love and idolize the other race. By the white dolls in the arms of your baby girls you are teaching them to love and honor white babies, and when these girls grow into womanhood naturally they will believe it more honorable to be the mothers of white babies than black babies. . . . By the white tin soldiers in the hands of your little boys you are teaching them to be serfs and slaves for the other race. . . . It is the babies in the cradle who will be the true Garveyites of tomorrow.

Matthews fervently believed that race mothers needed to shape little ones by controlling influences within the home, by actively promoting race pride, by “teach[ing] the instincts of Garveyism” from the cradle well into adolescence. In the process, women would serve as critical agents in promoting black consciousness as they realized the movement’s primary aim of black self-determination. Tellingly, Estelle Matthews came to the conclusion that black dolls would train race girlhood to “believe the highest joy is to love and honor their own black men.”

45Not only did the Garveyite newspaper “plu[g] the sale of black dolls,” the UNIA’s Negro Factories Corporation began manufacturing dolls once the association acquired Berry & Ross in late 1922.

46 Whether UNIA dolls were identical to those produced by Berry & Ross is open to question, but it is clear that active Garveyites were both subtly and outwardly urged to purchase UNIA dolls as a means of training their children in the very values of the movement.

47 One UNIA division in Ohio proudly reported the desirable outcome of its outreach activity: “Little Thelma Miller, eight years old, is very fond of her little colored doll. . . . She has never had the opportunity and pleasure of playing with no other doll except a colored doll. [Thelma] is a real Garveyite.”

48As colored dolls helped transform little girls like Thelma Miller into “real Garveyites,” movement girls played with dolls whose features suggested racial intermixture, a phenomenon that the UNIA deeply opposed. The Universal Negro Improvement Association—especially its leader, Marcus Garvey—condemned interracial sex and was preoccupied with racial purity. Ironically, the overwhelming majority of distributors and companies that advertised in the UNIA’s

Negro World and other race publications marketed dolls to African Americans that were “high brown,” “light-brown,” or even “mulatto.” The hair atop black dolls’ heads was yet another matter. During the 1920s, firms typically offered colored dolls with “long flowing curls” or “nice straight hair.” The cascading locks of a colored doll often reached and occasionally passed its buttocks. Black consumers had other options, but those options were somewhat limited: the Gadsden Doll Company was one of few companies to offer a doll with dark “natural hair” that can best be described as tightly curled; dolls produced by the UNIA’s own Negro Factories Corporation had “brown skin.”

49However limited, colored dolls represented a range of Afro-American looks, thus stalwart Garveyites could find the occasional doll that did not seem to vaunt a racially mixed ideal. For African Americans concerned with inculcating race pride in their children—including Garveyites in the United States, both native-born and immigrant—even a sepia-toned, silken-haired doll could promote black consciousness, police predilections, and ensure racial boundaries when compared to a white doll with golden tresses. For these people, dolls were a means to influence sexuality among both prepubescents and adolescents. Indeed, if Estelle Matthews and J. H. A. Brazelton expressed concerns about both boys and girls in terms of self-concept and intimate cravings, dynamics of race and reproduction resulted in gender-specific anxiety. Put another way, Maud Gary and Thelma Miller had something in common other than being little black girls alive during the first decades of the twentieth century: both were given colored dolls that were intended to inculcate them with a black consciousness that would, in time, shape their most intimate urges and choices.

There is little coincidence that black dolls became popular among aspiring, middling, and elite African Americans during the early decades of the twentieth century. Industrialization, migration, and urbanization transformed various forms of black leisure by providing growing numbers of African Americans with greater options along with increased opportunities to earn expendable income. Organizations such as the Negro Society for Historical Research (1912) and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (1915) started popularizing historically based versions of black consciousness as they professionalized the writing of race history. Prescriptive literature aimed at the working and aspiring classes promoted specific values and behaviors as reform-minded activists argued that the race should carefully place objects within domestic spaces as a means of uplift. Indeed, the production of prescriptive literature during the early twentieth century coincided with the appearance of children’s publications: from the books

Floyd’s Flowers and

Unsung Heroes to periodicals such as

Our Boys and Girls and the

Brownies’ Book, Afro-American children’s literature preached the virtues of good conduct, self-respect, and “race pride.”

50 Furthermore, since over half of the race had achieved literacy by 1900, more African Americans were reading newspapers and, as a result, advertising reached more black women, men, and children.

Changing demographic trends besides rising literacy rates informed how race-conscious men and women came to view texts, pictures, and toys—particularly dolls—as implements that shaped identity, behavior, and predilection. Birthrates of native-born black women in the United States declined with each decade as the nineteenth century ended and continued to do so as the new century progressed. Whereas African American women were likely to have more children than native-born white women, their fecundity experienced a sharp drop beginning with the end of Reconstruction and lasting until at least 1930.

51 A number of factors contributed to the drop in black women’s fecundity: migration, urbanization, and high levels of participation in the labor force all militated against frequent births.

52 Increasing numbers of black women made conscious decisions to limit pregnancies or delay marriage as well.

53As more black women had fewer children, aspiring, middling, and elite people had ample opportunity to read about changes in the African American birthrate. Black newspapers and magazines frequently ran stories about census statistics and race; they published analyses of what shrinking numbers meant as the percentage of blacks within the national population went from a little over 14 percent in 1860 to not quite 10 percent in 1920. Such a decrease might seem insignificant today, but at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, the decrease resulted in impassioned claims that African Americans faced extinction.

54 What was perceived as a precipitous drop in the black birthrate stoked fears about “race suicide” among a range of black people and organizations.

55 Above and beyond any anxieties that certain black people had concerning the number and quality of offspring produced by intraracial—not to mention interracial—unions, demographic transitions deeply influenced the ways in which many reformers and activists construed what black consciousness should entail.

The sharp drop in the black birthrate was significant in creating the very market for colored dolls in two different ways. First, if smaller family size ostensibly enabled parents to devote more attention and resources to the raising of each child, and if race reformers occasionally criticized working black mothers for not paying sufficient attention to their offspring, AfroAmerican doll discourse spoke to reformist, class-bound expectations that black parents could take an active role in shaping their children’s identities, intellects, and tastes.

56 Second, during the era of the “New Woman,” the possibility that young black girls would grow into women who either shunned marriage or opted out of motherhood altogether was disturbing for women and men vested in racial perpetuation.

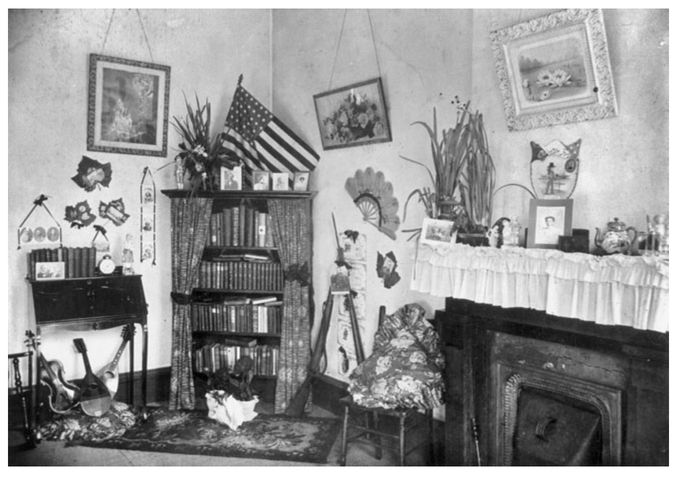

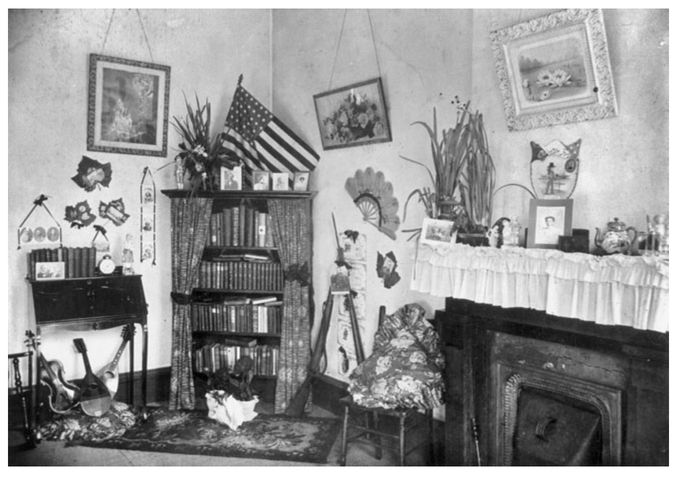

Corner in a teacher’s home, New Orleans, Louisiana, ca. 1899. Education-minded women and men imbued with race pride valued books for their content and as material objects. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-51558

Significantly, late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century anxieties over race suicide coexisted with both a nascent black consciousness movement and increased availability of commercially produced material culture that positively reflected the race’s appearance and achievement. There were strong links between black consciousness, Afro-American material culture, and the wishes of people such as J. H. A. Brazelton to see their “race variety sustained to the eternities.” As much as self-respect and love were part and parcel of an individual’s internal sense of esteem, material culture that countered racist mainstream stereotypes buttressed race pride by instructing, edifying, enlightening. Popular and material culture inspired not only through its ability to subvert endemic negative portrayals of the race but also if African Americans were the producers of commercial items. In 1921, for example, an ad for the Black Swan label not only argued that “every school child” should listen to records by “high class colored singers,” it also stressed that Black Swan records were “made by Colored People” instead of by a “Jim Crow annex to a white concern.”

57 Advertisements for race histories, calendars, pictures, and toys did not always reveal whether a company was black-owned or black-run. Companies such as Berry & Ross, however, made it a point to inform consumers that race women and men were in charge—and even to suggest that selling race products contributed to collective progress.

It is within this overall context that mass-produced and mass-marketed black dolls informed intraracial debates about collective destiny. The sale and promotion of colored dolls attempted to shape children’s sexuality at a time when lynching and rape posed serious threats to racial well-being. As commentators, activists, and eventually Garveyites expressed concerns about birthrates, miscegenation, and mob violence, advertisements promoted colored dolls as devices that could ensure racial purity by teaching children “respect for one’s self and for one’s own kind.”

58 The decision of parents (often mothers) to give their children—daughters especially—Afro-American material culture was an attempt to patrol desire in that dolls were seen as tools that influenced young Afro-Americans to select sexual partners within the race, produce children within endogamous heterosexual marriages, and eschew miscegenation.

Not every woman, man, or Afro-American publication committed to racial progress or preservation emphasized the power of dolls to shape self-image and conduct. In the mid-1910s,

Golden Thoughts on Chastity and Procreation captioned a photograph with a black girl cradling a white doll as “Maternal Instinct.” The 1922 edition of the

New Floyd’s Flowers contained a photograph of a black girl playing with white dolls; the text’s one image of a child playing with a seemingly nonwhite doll was retouched so that the doll only appeared “colored.” Neither

Golden Thoughts nor

New Floyd’s Flowers connected dolls to consciousness or predilection. Out of the two, only

New Floyd’s Flowers contained textual discussion of the power of dolls, and what Silas Floyd did write vaunted domestic life, skills, and the acquisition of maternal feeling.

59 Reform-minded African Americans associated doll play with a more general promotion of maternity and the home, then, but the specific discourse surrounding the utility of colored dolls primarily underscored that children’s toys shaped consciousness, identity, and the most personal of tastes.

The colored doll was indeed a live one, especially given anxieties over miscegenation and racial destiny—anxieties that existed from the immediate postemancipation period up into the 1920s. The women who expressed their opinions to race publications about toys they gave to their children and the men who expounded upon why parents should purchase colored dolls did so when more than a few African American activists had something to say about interracial sex and its impact on the race. Commentators ultimately did more than suggest that mothers had a special duty as consumers to purchase colored dolls and maintain that it was particularly critical to shape girls’ sexuality, then. These commentators made their contentions as heated considerations of miscegenation raged among other African American intellectuals, activists, and reformers—contemporaries whose assessments would, more often than not, also prioritize ways in which girls’ and women’s behavior needed to be controlled in the name of racial preservation.