2 Grant County’s Mining District

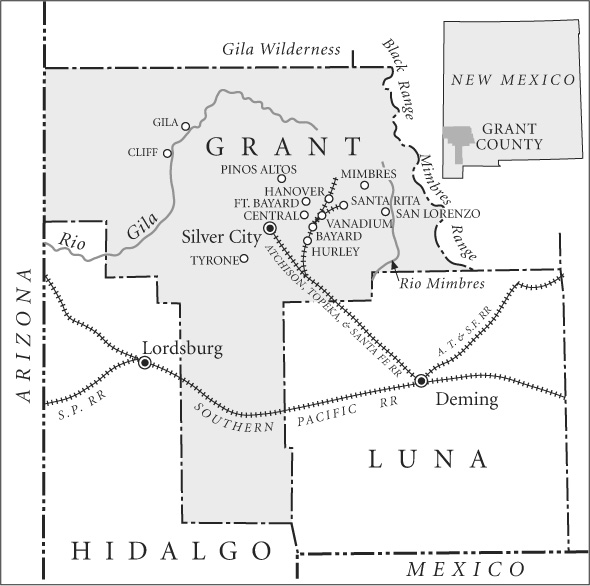

Grant County lies in the southwestern corner of New Mexico, separated from the Rio Grande by the Black Range to the east and the rugged Gila Wilderness to the north. (See Map 1.) Low rolling hills covered with scrub and grasses are interrupted by sharper inclines and canyons. Winding under the hills and mountains are metals that people want: grains and crystals of gold, silver, copper, lead, and zinc. For two centuries, these metals have been the bedrock of the European American economies here; the social relations that structured their extraction, however, have not been nearly so stable. They changed from systems of large-scale forced labor to individual prospecting by Anglos and Mexicans, then to large-scale wage labor in capital-intensive mines and mills. With this last arrangement came a new racial order, the dual-wage system, in which Mexicans were confined to the poorest-paying jobs. Spreading out from the workplace, this racial order was manifest in housing, school, and social segregation, and it grouped all Mexicans, whether native-born or immigrant, into a single, subordinate class. In this chapter I show the development of Grant County’s mining economy alongside its streams of immigrants, ending with the dual-wage system and paternalist labor relations against which miners began to rebel in the 1930s.

Two centuries is hardly anything compared to the millions of years it took to create southwestern New Mexico’s metal deposits. On the shore and on the floor of the prehistoric ocean, limestone, shale, and sandstone were gradually pressed into very thick, dense layers. About sixty million years ago, molten rock pushed upward and broke them up. Into the cracks seeped hot water carrying dissolved minerals; as the whole mass cooled, the water disappeared and the cracks remained full of minerals.1 But any miner who arrived then, hoping for a big strike, would have decided the ore was hardly worth mining: the ratio of useful mineral to rock was far too small.2

Map 1. Grant County, N.M.

These minerals became valuable to people because of erosion by water and air. In the case of copper, this erosion turned pyrite (iron-sulfur deposits) into sulfuric acid. The acid then dissolved chalcopyrite (copper-iron-sulfur) and sent copper solution down through cracks all the way to the water table, where its reactions produced chalcocite (copper sulfide).3 This was the good stuff: a vast, rock-hard pool of copper sulfide, along with porphyry copper disseminated through quartz. But 35 million years ago, before human beings could get to it, indeed, long before human beings walked the earth, lava and ash buried it. Then water and air eroded the tuff beds and exposed some of the copper in what would come to be known as the Santa Rita mines. North and west of Santa Rita, similar processes distributed gold placer, vanadium ores, lead-carbonate ores, iron, chalcocite-silver ores, and zinc sulfides in the shape of an elliptical ring, about three miles north to south and a mile east to west.4 It was “the most highly mineralized district” in what would become New Mexico.5

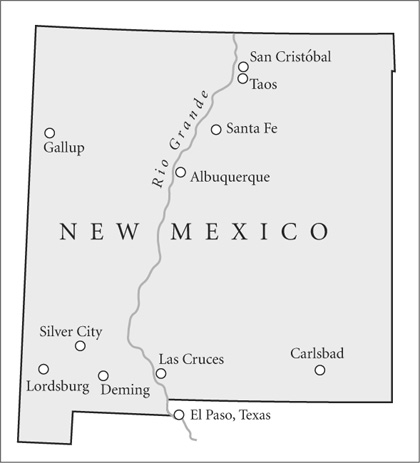

Map 2. New Mexico

MINING IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Native groups, of whom the Apache became the predominant, mined copper for centuries, but their economies rested more on hunting, gathering, and (by the end of the seventeenth century) raiding.6 Apache territory was roughly encompassed by the Gila Mountains in the north, the Rio Grande in the east, the White Mountains of Arizona in the west, and Chihuahua in the south, and groups of Chiricahua Apache swept a wide circle in their seasonal migrations. Deep in Sonora and Chihuahua they raided Spanish ranchos and villages for cattle, horses, food, and captives. An entire group typically traveled together, with warriors heading off to raid, hunters taking off to hunt, and everyone else making camp. An impressive range of elevation—some 5,000 feet between desert floor and mountain—gave them a range of food; women harvested crops and gathered mescal, piñons, mesquite beans, berries, and other plants.7

In 1798, an Apache man showed the Santa Rita mines to a Spanish army officer, José Manuel Carrasco. Carrasco was delighted to “discover” this treasure—one whose worth he recognized because he had grown up near the copper-rich Río Tinto in Spain—but he could not afford to develop the mine himself. He got the help of a Chihuahua banker and merchant, Francisco Elguea.8 Don Francisco enjoyed leases from the Spanish crown to both land and labor, which is to say that the crown built a penal colony there to supply workers.9 His adobe fort happily “served the double purpose of controlling the miners and affording protection against Apache incursions.”10 Men descended “chicken” ladders (made either of rope or of a single notched pole of pine) 100 feet into dark holes, and they climbed back out with 200-pound bags of copper—as much as ten tons of ore every day.11 Beginning in 1804, mule trains hauled copper ingots to Chihuahua for use in coinage. Mexicans continued the trade after independence from Spain in 1821, minus the forced labor and with more and more families settling the district.

Most New Mexican trade headed south to Mexico City, except for some trade confined to the upper Rio Grande. But goods from the Santa Rita area traveled a slightly different route, the “Copper Trail” overland to Janos, Chihuahua, then to Chihuahua City, where it merged with the main trunk of the Camino Real. These different paths have corresponded to different histories of the regions, too. Most historical scholarship has focused on central and northern New Mexico, where Spanish missionaries, soldiers, and settlers first claimed territory for the Spanish crown in the sixteenth century and where Anglo traders began to reshape the Mexican commercial economy in the 1820s. Conflict among Indians, Hispanics, and Anglos marks the history of this region, particularly over land title, labor, and water rights.12 Grant County, by contrast, was settled much later and much more tenuously, with Apaches defending their territory successfully against Spaniards, Mexicans, and Americans alike until late in the nineteenth century.13

If Santa Rita’s copper district differed from older New Mexican settlements, it nonetheless shared one feature with them. The mines attracted people of many nationalities whose presence was alternately a boon and an annoyance to the Mexican government far to the south in the period 1820–46. French and American adventurers mined copper in Santa Rita and trapped beaver along the Gila River, among them Kit Carson, who trapped along the Gila when he was not working as a teamster at the mine.14 Sylvester Pattie and his son James leased the Santa Rita mine in 1825–26, and their party also trapped along the Gila River.15 Irishman James Kirker arrived in 1824 and “trapped along the Gila every winter . . . , as late as 1835.”16 Robert McKnight and Stephen Courcier ran the mines from 1826 to 1834, and they hired Kirker to guard the mule trains from Santa Rita to the smelters in Chihuahua.17 Some of these mountain men married Mexican women, just as many trappers did farther north, and their descendants often belonged to Mexican American communities. James Kirker became a Mexican citizen (in order to get trapping permits), married Rita García sometime around 1831, and set up house in Janos, Chihuahua, where he and his wife reared five children.18

Unfortunately for all the settlers, and even less fortunately for the Apaches, an American trader named James Johnson arrived in 1837 and arranged “with some Mexicans at Santa Rita to rid New Mexico of the ‘Apache menace.’”19 The Apaches had accommodated some of the intruders, probably because they were more interested in raiding the productive farms and ranches farther south. Many trappers, in fact, were well regarded by the Apaches and considered Apache leaders their friends. But Johnson planned to present the governor of Sonora with the scalps of Apache leaders Juan José Compa and Mangas Coloradas and anyone else he could kill, and for each scalp he expected an ounce of gold. He invited the Apache to a trade meeting, during which he ordered his trappers to open fire.20 Juan José Compa was killed, as were many Indian women and children who had joined the festivities, but many Apaches escaped and organized a retaliation against not only Johnson and the trappers but the settlers as well. The war, for that was what it quickly became, isolated the mining town and drove all of its settlers south toward Chihuahua. Only a few made it that far; most were killed on the way.21 Johnson never got his scalps (he barely kept his life), and mining shut down for thirty years.

Mexicans continued to settle along the rivers and to prospect a bit, both before and after the U.S.-Mexican War, which transferred the territory to the United States in 1848, but settlement in the mining district remained sparse until after the Civil War. In the decade following annexation to the United States, mining attracted both families (usually Mexicans) and single men (usually Anglos). Among the miners were two of Jim Kirker’s sons, Rafael and Roberto. A few Anglo Americans and Europeans had some capital at their disposal, including a German named Henkel, who founded the town of Hanover in the 1850s and operated a copper mine and smelting works there. One hundred fifty men and thirty women, almost all Mexican, worked for him, the men earning $30 a month and women half that.22

But none of Grant County’s settlers could feel securely settled. Chiricahua Apaches kept both Anglos and Mexicans on edge, causing miners and farmers alike periodically to pack up and move out. The Apaches were threatened by the glut of people who were destroying their hunting grounds; a gold strike in Pinos Altos in 1860, for example, quickly drew thousands of people. American aggression infuriated the Apaches, most notably when leader Mangas Coloradas was savagely beaten by a group of drunken miners whom he had tried to induce to prospect farther north.23 Facing more and more settlers who enjoyed more and more military protection, various Apache groups negotiated with the U.S. government for food, livestock, and land in exchange for settling permanently on restricted areas of land, only to find that the U.S. government failed to honor its end of the bargains. A cycle of raids and peace went on for decades, the Apaches making good use of the disruption caused by the Civil War, until the U.S. Army drove them to reservations east of the Rio Grande in the 1880s.24 They were the last holdouts of the Indian wars that consolidated the continental United States.

Apache strength accounts for another difference between Grant County and other parts of New Mexico: Mexicans and Anglos settled the region at roughly the same time, albeit often in different locales, and both groups were accorded the “pioneer” status befitting anyone who endured Indian threat.25 This is quite remarkable, for the pioneer myth centered on European Americans moving westward across the continent and, to the extent that the myth acknowledged prior occupants, displacing those occupants under the banner of progress. Mexicans fared poorly in this American origin story. The ideology of manifest destiny gained currency in the 1840s precisely around the time of the U.S.-Mexican War, and Mexicans were routinely dismissed as a degraded race. In fact, this version of racism helped delay New Mexican statehood some seventy years, for Americans elsewhere feared that their polity could not absorb such large numbers of backward citizens.26

Under some circumstances, this parallel, if not entirely shared, experience might have kept Mexican Americans and Anglos on some level of social equality, and intermarriage during the period 1850–1900 may have accomplished something of the kind in rural Grant County. Joe T. Morales, a strong Mine-Mill leader and an actor in Salt of the Earth, traced his origins to one such family from the Mimbres Valley.27 In this respect, the Mimbres Valley looks a lot like the San Pedro Valley in southeastern Arizona, where Mexicans, Anglos, and other Europeans together faced the same Apache threats, owned similar amounts of land, and inter-married.28 This was less true of Silver City, the main town in Grant County, however. Compared to other areas of New Mexico, where “the overwhelming majority of married Anglo men . . . were married to Hispanic women,” only a third of such Silver City men were married to Hispanic women in 1870 and fewer than a quarter were in 1880.29 Moreover, as historian Deena J. González warns us, intermarriage does not necessarily indicate assimilation (in either direction) or cultural unity.30

But as the power of Anglo mining companies, cattle ranchers, and other local Anglo notables grew, it eroded what started out and could have remained a situation in which ethnicity did not necessarily mark social status. The transformation from small-scale to capital-intensive mining around the turn of the century decisively changed social relations in Grant County. A local Anglo elite consolidated its power, class divisions were sharpened, and the worst jobs became synonymous with “Mexican” jobs. By 1920, a German like Henkel would have been considered “Anglo,” because non-Spanish people were subsumed under that term.31 The distinction that came to matter most was that between Anglo and Mexican, a distinction manifest most clearly in the dual-wage system that developed in the mining industry.

CAPITAL AND ENGINEERING

Capital-intensive mining became the engine of Grant County’s economic growth in the twentieth century. Precious metals like gold and silver continued to be important (and they still attract prospectors to this day), but alone they could not drive Grant County’s economy. Silver City and its neighbors would have gone the way of places like Tombstone, Arizona—rapid settlement, lots of money changing hands, rough conditions, and then depletion of the ore, followed by the disappearance of its citizens—were it not for the demand for base metals and the development of new methods for extracting them, methods that required great amounts of capital and labor. Copper, lead, and zinc had been used for thousands of years, but with new manufacturing processes that depended on them came a demand for unheard-of quantities of these metals. Copper’s exceptional ductility made it indispensable for electrical wiring. Lead was needed in storage batteries and telecommunications casings. Zinc was essential in galvanizing steel and vulcanizing rubber, and it was especially important in die casting, which enabled mechanized production. The world production of finished metals increased almost tenfold between 1880 and 1920; in that same period, U.S. production grew at twice that rate, from 30,200 tons produced in 1880 to 612,000 produced in 1920.32 The world smelter production of zinc was 50,000 tons in 1850; by 1910 it had increased sixteen times to 800,000 tons.33

The Empire Zinc Company, formed in 1902, was one of many companies aiming to profit from this demand. Empire Zinc was a wholly owned subsidiary of the New Jersey Zinc Company, whose own predecessor, the Sussex Zinc and Copper Mining Company, had built the country’s first commercial zinc smelter in 1848.34 With New Jersey Zinc behind it, Empire Zinc explored and developed mines in Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and Mexico. This required no small investment, because until New Jersey Zinc developed a flotation process that could readily separate zinc from lead in complex ores, these western districts were almost worthless.35 Empire Zinc set up operations in Hanover, a few miles northwest of Santa Rita, and in Magdalena, in neighboring Socorro County.

By 1920, corporations, many of them large multinationals, had bought up numerous mining camps and dominated the local economy. In 1919, only 47 percent of New Mexican metal mines were corporate, but those corporations produced 98 percent of the value of mine products and employed 96 percent of the state’s metal miners.36 The trend continued in the 1920s such that half of New Mexico’s fourteen copper enterprises were corporately owned, producing 98 percent of the value of copper products and employing 95 percent of the state’s 2,258 copper miners. Seven of the eight zinc enterprises were corporately owned.37

Individual miners and small firms did not disappear from the landscape, though. Thirty percent of New Mexico’s mine operators in 1919 were individuals, and another 23 percent were firms, smaller operations of one or two miners that often leased claims from other individuals or from already-existing companies, and that permitted the individualist symbol of an earlier era—the prospector—to persist.38 But the prospector of the twentieth century was as likely as not to have an advanced degree in mining or metallurgical engineering. Companies turned to engineers, experts who could design and operate new mining technology and who could confirm the worthwhile deposits. Mining claims were risky, and companies needed experts to separate the promising from the disastrous. Mining engineers formed a cohesive bunch, and they came to represent the changing class structure of industrial mining as it developed within the United States and across national borders. As much as they might celebrate the virtues of individualism, they were remarkably similar to one another in background and education. And they depended on corporate largesse at the same time they were striking out on their own paths.

Ira L. Wright was typical of many mining engineers of his generation. He combined a breadth of experience—many kinds of mines, many kinds of ores; mining engineering and metallurgy alike—with an enterprising spirit that made him one of the most successful mine operators in Grant County. Wright was born in 1883 on a farm near Hughesville, Missouri. After graduating from a country school, he went on to the Missouri School of Mines in Rolla.39 Like any mining school worth its salt, the Missouri School of Mines sent its students to work all over the country during the summer. It was imperative, most engineers and educators believed, to give their students a feel for the work and, importantly, a feel for the workers. Mining engineers could expect to become mine managers in some capacity or another, and the miners who trained them on the job would probably be their employees a few years down the road.40

While still a student, Wright did stints in Utah copper mines and Missouri coal, lead, and zinc mines. These were exciting times for ambitious young engineers, who were in great demand around the turn of the century.41 After he graduated in 1907, Wright went to Bisbee, Arizona, to work for the Calumet and Arizona Copper Company, and a couple of years later he moved to the Silver City area to work for the Savanna Copper Company.42 These were typical first jobs for a mining engineer, combining surveying, assaying, and reporting on the likely worth of a mine claim. They were also relatively low-paid jobs, for companies mined recent graduates for cheap labor.43 Wright must have seen the possibilities that additional credentials would open, because he went back to Rolla for a master’s degree in mining engineering.

When he returned to Savanna Copper Company, he put this education to good use—his own. Like many engineers, Wright leased claims from the company while working full-time for a regular paycheck. He and his partner, James Bell, had few “resources except unbounded energy and sublime faith,” the local newspaper reminisced twenty-five years later. They hired some inexperienced miners to do some of the grunt work, and “one night they actually ‘gophered’ into a chamber of almost pure gold.”44 The wily Wright did not let on to the others what they had found; instead, he genially suggested that they take the night off to enjoy a local dance. The chamber was safe for him and Bell to exploit as much as they could. Over the next four years, they got somewhere between $50,000 and $100,000 from this Pinos Altos mine, a strike that “electrified southwestern mining circles.”45

After Pinos Altos, Wright worked as a metallurgical engineer for the Chino Copper Company before opening an engineering and assaying office in Silver City. Around 1920, Wright signed on with the ailing Blackhawk Mining Company, which soon elevated him to general manager. Under his capable management, Blackhawk started to turn a profit on lead and zinc ores that could be processed with the flotation method pioneered by New Jersey Zinc. Wright continued his independent projects while running Blackhawk for the next thirty years. He became one of the local notables, helping found the New Mexico Miners and Prospectors Association in 1939 and reporting regularly on the health of the mining economy.

While mining dominated the economy throughout Grant County, the centerpiece of Grant County’s mines was always Santa Rita. Francisco Elguea’s heirs, whom the U.S. General Land Office confirmed as Santa Rita’s owners, had split the property into smaller claims and sold them to J. Parker Whitney of Boston in 1881. Whitney then subleased the mines to other operators, who took as much high-grade copper as possible and left the low-grade ore as waste.46 By the turn of the century, the remaining ore was low-grade, and only expensive new technology could extract valuable copper from useless gangue. Moreover, low-grade ore promised a profit only if mined on a scale that the lone prospector could not achieve. Processing the ore required new mills for crushing rock, new chemicals for separating minerals, new reverberatory furnaces for smelting. The depletion of high-grade copper, at a time when people were eager to cash in on the copper market, set the stage for technological and social change in Grant County.

The catalyst for this change was a mining engineer named John Sully. Sully was born in Dedham, Massachusetts, in 1863, and earned a B.S. in mining engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1888. He spent fifteen years working in Montana, California, and Alabama mines before landing in Grant County in 1903. There, he inspected Santa Rita’s prospects on behalf of General Electric.47 General Electric soon lost interest in the project, but Sully did not, and after an interlude of a few years in Mexico, he returned to Santa Rita in 1908 as a consulting engineer for the Santa Rita Mining Company. Ten months of surveying convinced Sully of Santa Rita’s worth. It had, he declared, something on the order of 3,217,060 tons of developed copper ore, plus more than 5 million more tons of what he called “expectant” ore. But the copper content was only about 2.73 percent (2.39 for the expectant ore), so only new methods of mining and milling could make it pay off.48 Instead of digging tunnels and stopes underground, Sully thought that digging a wider and wider hole, and hauling the ore from the pit in railroad cars, would make it both possible and profitable to exploit the deposits.

In this he followed the lead of another mining engineer, Daniel Cowan Jackling. Jackling made a name and a fortune for himself by starting the massive open-pit mining operation in Bingham Canyon, Utah, and he would come to influence Santa Rita’s development, too.49 Like Ira Wright, Jackling was a Missouri farm boy who made his way to the School of Mines. As a teenager he was making $14 a week as a farm hand when he realized there was little future in it: the agricultural ladder that supposedly led the hardworking farm laborer up into farm ownership ended abruptly on the wage-earner rung. He worked for railroads to pay his way through school and graduated in 1892 with a degree in metallurgy. After teaching for a year at his alma mater, Jackling headed west, arriving in Cripple Creek, Colorado, with three dollars to his name.50 The gold mining camp of Cripple Creek was in its heyday, a microcosm of the emerging industrial order where miners jockeyed for prospects and investors alike.51 Jackling hooked up with other young men on the make, and through them he made contacts with wealthy investors in Colorado Springs and Denver.

Later in the decade Jackling was cashing in on one such contact. He supervised a cyanide plant at Mercur, Utah, and in 1898 the company president asked him to test ores from Bingham Canyon. Bingham Canyon was rich in copper, but it was “porphyry copper”: the metal was diffused through quartz, so recovering any of it meant mining all of the surrounding rock. This was a problem. Jackling’s solution was to use steam shovels to tear big chunks of rock from the earth and then to mill it with new methods that made a richer concentrate of copper. He had gotten this idea from seeing similar shovels at work in the Mesabi iron range in Minnesota. Building the equipment he proposed would require massive capital investment, and, just as in Sully’s case six years later, the company declined to make that investment. But Jackling was a pro at getting financial backers—fortunate, since he had no money of his own—so he formed the Utah Copper Company in June 1903 to undertake the Bingham Canyon project himself. A few years later, when he was ready to start mining the open pit, the Guggenheim family invested in his company. Jackling quickly began building a 3,000-ton concentrator in Copperton, the first mill to process the same kind of porphyry copper that Santa Rita held.52

By 1909, Jackling’s mine and mill were so successful that his approval alone secured investment in Sully’s proposal to create the new Chino Mining Company as a subsidiary of Jackling’s Utah Copper. The Chino Mining Company operated the Santa Rita mines and, in 1911, a new mill at Hurley, a railroad depot eight miles south of Santa Rita.53 Thus did Chino join a vast empire of copper mines, coal mines, and food production. Part of what made companies able to sit out a long stretch of losses in a new mining venture was its vertical integration, or the degree to which the same company controlled many aspects of production. In the case of mining, a company like the American Smelting and Refining Company (Asarco) owned mines, mills, smelters, refineries, and transportation—in short, all the stages of production.54 Jackling’s company, too, controlled many levels of production. All of Santa Rita’s and Hurley’s store provisions were shipped in, some $340,000 worth in 1937. Companies in which Jackling invested, such as the Gallup American Coal Company and the Great American Sugar Beet Company, provided the coal to run its steam shovels, trains, and mill, and the foodstuffs to feed workers in Santa Rita and all the other mining camps.55 And there were many mining camps, all pulled into a set of corporate relationships that shifted, shrank, or grew according to the demands of the metal market and the ambitions of the mine operators. Utah Copper was bought by Nevada Consolidated in 1922, which was itself bought by Kennecott Copper Corporation in 1933. But Jackling kept control over most of the western operations for many years and sent his mining engineers from one property to the next, spreading technological skill and helping consolidate these men, and their families, into a cosmopolitan class.

AN INDUSTRIAL WORKFORCE

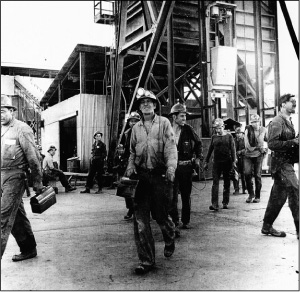

Capital was one thing, and corporations like Empire Zinc and Chino had it. But they also needed a large workforce. No machine could be trusted to blast holes, drive trains, lay new track, or repair the machines themselves. Thousands of men, Anglo and Mexican alike, took jobs in Grant County’s mines between 1910 and 1950.56 Industrial mining and milling were complex processes that required many people to fill a wide variety of jobs. Many mine workers were craftsmen plying trades common to any industrial enterprise: blacksmiths, boilermakers, electricians, carpenters, plumbers, machinists, and railroad brakemen and engineers. The miners themselves were a varied group; “miner” is both a generic term for any employee of a mine, itself denoting operations both above and under the ground, and a specific term for the individual who gets the ore.57 Subsuming the varied occupations in one term provides a useful shorthand for discussing the employees of the entire industry and their identity as workers in masculine jobs. But it also obscures the wide range of work required in Grant County’s mines and mills, a range that both reflected the industry’s complexity and reinforced the discrimination attending ethnic distinctions.

Grant County’s miners shared similar work processes and rhythms. An underground miner’s day began early in the morning or mid-afternoon, depending on his shift.58 First he changed into work clothes, if the company provided a changing room; this was an amenity won by unionized miners in the 1920s, but no unions took root in Grant County until the 1930s. Next the miner went to the main shaft and descended in a cage with twenty or so other workers.59 The main shaft traveled downward hundreds or even thousands of feet, either vertically or at an incline. A massive hoisting mechanism, hung from a headframe above the mine opening, allowed the cages and skips to be moved up and down the shaft at speeds reaching eight hundred feet per minute for men, and even more for other materials.60 The hoistman, as the Mine-Mill union observed, held “at all times men’s lives in his hands [and handled] some of the company’s most expensive property.”61

A station surrounded the shaft on each working level, and at each station the cager directed the comings and goings of men and materials. Crosscuts, or horizontal passageways, led from the shaft to the vein of ore and created a dense hive of rooms and working areas. Raises and chutes connected levels to one another, generally fifty to a hundred feet apart. Timbermen built the chutes, made the ground a safe working surface, and repaired timber supports. Trackmen and pipemen installed the critical transportation system of tracks, pipes, and trams.

Metal mining, also called hard-rock mining, depended on controlled explosions to drive tunnels from the shaft to the ore face and wrest ore from its deposits. Miners excavated the ore in a series of stopes, or step-shaped hollowed-out blocks. This method increased the number of rock surfaces, which in turn made the blasting process more precise and efficient.62 First a miner drilled a series of holes, entering the rock face at different angles. Into these holes he loaded the proper type and amount of explosive (or powder), and then he attached wires to the cartridge’s blasting cap. Moving some distance away, and warning his helpers and nearby workers, the miner ignited the cartridge, blasted the rock, and waited for the dust and debris to settle.

Miners at shift change, ca. 1950. Photo courtesy of Ricardo Trevizo.

Muckers helped load explosives, supplied the miner with steel drills, and then shoveled the ore into chutes or cars that brought it back to the station. In many instances, muckers did exactly the same work as miners, but they were never paid the same wage. By the mid-1940s, mucking machines and air-driven hoists had begun to relieve some of the backbreaking physical labor, but the machines themselves were dangerous and hard to manage.63 Crushermen, as their name implied, crushed oversized boulders into pieces that would fit in the cars. Trammers moved the cars along tracks or, as at the Peru Mining Company in Hanover, dumped and refastened ore buckets that moved along aerial trams. Grizzlymen, also called underground pocketmen, unloaded ore cars and helped the cager load the skips heading back to the surface, often drilling and blasting those rocks that were too large for the skips to lift. At the surface, toplanders helped men in and out of the cages and dumped ore and waste into railroad cars; their job resembled that of cagers. Railroads took the ore to a mill for processing.

Chino’s open pit was a different sort of operation entirely.64 The open pit expanded downward and inward in concentric circles, eating away the land under Santa Rita. The town was gradually confined to a peninsula that jutted into the pit, and the company had to move all its buildings, and the cemetery, to accommodate the ever-expanding pit; by 1960, the original site of Santa Rita had disappeared altogether. Open-pit miners were not subject to the dangers of underground mining, but their work was hazardous nonetheless. On each working level, or bench, miners drilled holes fourteen inches in diameter and sixty feet deep, typically ten or twenty feet from the edge of the bench, and blasted between twenty and fifty holes at once. Twenty-five tons of explosive, for instance, would dislodge a quarter million tons of rock.65 Shovel operators loaded rock tons at a time into railroad cars. Because the working surface changed so frequently, trackmen were always needed to lay new track along the newly blasted levels. In the 1920s, Chino replaced the steam shovels with electric shovels; during World War II it further electrified the operations and replaced the trains with gigantic trucks that hauled fifty or more tons, their drivers sitting sixteen feet above the ground.66

In Grant County, companies both mined and processed ores. Ore processing entails separating the desirable minerals from each other and from useless rock in a series of stages. The first stages take place in a mill, later stages in smelters and refineries. There were four mills in the Central mining district: Chino treated all its copper in Hurley; Empire Zinc and Asarco each treated lead and zinc in Hanover; and later the U.S. Smelting, Refining, and Mining Company treated lead in Bayard. Other companies sent their ores to local mills for initial processing or sent them straight to El Paso, Amarillo, and points east for milling or smelting. Chino built its own smelter in Hurley in 1938.

Millmen ran huge crushing and grinding machines that broke the rock into smaller and smaller pieces, often down to powder. Gravity separated metals from other rock. To the metal powder, men in the flotation department added chemicals that made the ore float to the top, from which others skimmed it—now more or less a mud—into separate tanks. After another round or so of concentration, mill workers shoveled the ore into bins for weighing and then onto railroad cars for shipping.67 Smeltermen added heat to the process. After mixing mill concentrates with silica and limestone, they melted it all down in a reverberatory furnace. The upper level was slag, or waste, that they hauled to waste dumps; the bottom layer was a copper matte that they further reduced in furnaces. Copper bars or molds were then shipped east for use or for further refining.

The men who came to Grant County’s mines in the twentieth century soon learned who belonged where. In the American Southwest, ethnicity came to determine the allotment of jobs and, as we will see below, the location of homes. As Table 1 shows for Santa Rita and Hanover mines, Mexican Americans outnumbered Anglos but were disproportionately clustered in the “laborer” category, which included very few Anglos. Mexican American men typically started as general laborers and, until the 1940s, seldom advanced far. In 1934, Chino general laborer Julián Horcasitas, for example, was earning $3.65 a day; track laborer Francisco Costales, who had started working at Chino in 1923, earned $2.60 a day.68 There was no chance for Mexicans to advance above a very low ceiling. Many Mexican jobs—like laying track for the train cars that hauled ore out of the open pit, or repairing train cars in the railroad yard—had no lines of promotion leading away from them; José M. Martínez, for instance, started working as a track laborer in 1918, and he retired from that position in 1953—thirty-five years in Chino’s lowest-paying job. The only way a Mexican American could hope for a promotion was to get transferred to another department altogether.69 So few Anglos worked as “laborers,” in fact, that the job title was probably a euphemism for “Mexican.”70

Craft and some railroad jobs pulled the highest wages and went almost exclusively to Anglo men. The railroad industry was extremely segregated all over the country, and Grant County barely diverged from the national pattern. As a matter of policy, the “Big Four” railway brotherhoods, which represented engineers, conductors, brakemen, and firemen, excluded Mexican Americans and other people deemed nonwhite; in nonunion areas like Grant County before the 1940s, however, the firemen (who fed the furnace in the engine room) were occasionally Mexican.71 V. H. Crittenden started work at Chino as a steam shovel fireman when he was teenager. He was probably helping support his widowed mother, who ran a boardinghouse in Santa Rita. By 1934, when he was just over thirty years old, he was a crane and shovel operator earning $5.25 a day.72 Locomotive fireman and engineer Joseph W. Baxter, who started working at Chino in 1920, earned $5.15 a day in 1934.73 There were some important differences between the mines in Santa Rita and Hanover, however, with respect to other craft jobs: twenty Mexican men held such jobs in Santa Rita (11 percent of the total skilled railroad and other craft workers), while none did in Hanover. By contrast, while the same number of Mexican men in both Santa Rita and Hanover worked as “other mine employees”—such as drillers, hoistmen, pumpmen, and cranemen—this number (twelve) represented very different proportions of that workforce (12 percent of Santa Rita’s versus 33 percent of Hanover’s).

Table 1. Men Employed in the Mining Industry, Santa Rita and Hanover, N.M., 1930 | ||||

| ||||

| Occupational group | Santa Rita | Hanover | ||

|

|

|||

| Mexican | Anglo | Mexican | Anglo | |

| ||||

| Laborers | 420 | 5 | 113 | 8 |

| Helpers | 11 | 23 | 1 | 4 |

| Miners | 11 | 6 | 26 | 18 |

| Skilled railroad workers and other craftsmen |

20 | 157 | 0 | 18 |

| Other mine employees (drillers, hoistmen, pumpmen, cranemen, etc.) |

12 | 90 | 12 | 24 |

| Office employees | 5 | 8 | 0 | 4 |

| Security | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Engineers, scientists, and doctors | 0 | 13 | 0 | 11 |

| Foremen, managers, and owner-operators |

3 | 28 | 0 | 15 |

| Prospectors | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Contractors | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 484 | 335 | 152 | 106 |

| ||||

Source: 1930 manuscript census, New Mexico, Grant County, Precincts 11, 13, and 16 (Hanover, Vanadium, Bayard Station, and Santa Rita).

Managers were almost always Anglo, some homegrown and some brought in from other Jackling operations. Horace Moses, for example, grew up in Grant County and worked at Chino from the beginning. He had graduated from the State Teachers College in Silver City, but even without formal training as a mining engineer he was appointed general foreman in 1912. He held that position until the 1920s, when Nevada Consolidated, which bought Chino in 1923, appointed him general manager of its coal mines in Gallup, New Mexico. He returned to Santa Rita in 1938 to superintend the whole Chino outfit.74 By 1930, only three Mexican American men had made it into the ranks of Chino foremen; the other twenty-two foremen were Anglo. Those Mexicans who did enter management did so after a much longer stint in wage work than was required of their Anglo counterparts. Felipe Huerta, for instance, began working for Chino in 1912, the same year as Horace Moses. He was a general laborer for thirty years before his 1941 promotion to the powder department, which tended the open pit’s explosives; in 1950, he was finally promoted to powder foreman.75 The situation was not much different in Hanover, where no Mexicans worked in any supervisory or clerical position in 1930.

If ethnic segregation generally defined Grant County’s mining industry, sex segregation was even more extreme, to the point that it barely warranted notice. The sexual division of labor, present everywhere, is especially pronounced in mining districts, where women have rarely found work in the mines. Women’s exclusion from North American mining has a long history. Individual nineteenth-century women found their way into prospecting and placer mining, occasionally accompanying their husbands or partners; anecdotal evidence points to some women managing mines even earlier.76 In some instances, mining—or at least the aboveground processing of ore—was evidently considered suitable work for women. Indian women mined, transported, and smelted lead in the upper Mississippi River valley until the 1830s, when their communities were pushed out of the region, and California Indian women integrated mining into their seasonal work during the gold rush. Mexican women played some role in Henkel’s Hanover mine, and other Mexican women could be found sorting ore in Guanajuato silver mines as late as 1907.77 A few women worked in Appalachian coal mines in the mid-twentieth century, despite male miners’ resistance.78

But if women occasionally worked aboveground in various aspects of mining, they seldom worked underground. Cornish miners believed that it was bad luck for women to go into the mines, and they brought this idea to North America.79 Just such a distinction may account for the differing attitudes expressed in 1904 by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), Mine-Mill’s predecessor. A paean to the “idol of Groom Creek Miners Union,” one Mrs. H. H. Keays, celebrated her accomplishments as miner and as member in her own right of Local 154. Keays accompanied her husband in his prospecting, “endowed with a sublime fortitude that [would] challenge the fearless intrepidity of the most courageous men,” yet she “lost none of the feminine graces that [made] her a queen in her home.”80 Contrast this with the hellish vision of Belgian women and girls of the same era working underground, sometimes as deep as 4,000 feet: “female slaves of toil spend[ing] 12 hours of imprisonment in the bowels of the earth to earn the pittance that prolongs a life of miserable poverty.”81

Seemingly insignificant distinctions can carry weighty ideological baggage. Both Keays and the Belgian women worked in the mining industry, but their place and conditions of work, ages, and presumed relations with men differed in critical respects. Keays and her situation met the requirements for a progressive vision of American history, particularly as played out in the American West. She exemplified “woman,” who, “by the very force of her character, has swept hoary conventionalities into the grave.”82 Keays’s work with her husband did not threaten gender divisions because she performed it within certain accepted conventions (which did not, evidently, get swept away): she was married to her coworker, not working alone or with strange men; she worked above ground in prospecting and placer mining, not in the mine shafts; and her work did not compromise her femininity, since she retained her “feminine graces.” The individual prospector assumed an important place in the myth of the ruggedly individualist West, and the WFM was willing to laud the occasional exceptional woman as well. But not those women, especially young women, working underground. The situation of Belgian female miners was no golden opportunity but rather a sad misfortune in the eyes of an American labor movement concerned over horrific industrial conditions and, just as important, over the proper place for women in European and American industrialism. Belgian women miners belonged to an inhumane system that denied working men a family wage—a system that American labor leaders feared in their own country as well: while “the American citizen, whose bosom swells with patriotism, may censure the dynasty of King Leopold, . . . in the ‘Land of the free and the home of the brave’ the mills and factories of the cotton kings present a spectacle that makes Belgium look like ‘A garden of the gods.’”83

Miners had little to fear that industrialism would directly threaten the lives of their wives and daughters, for few women worked in industrial settings in Grant County’s mining district. Few women worked for wages at all, although this varied considerably by town. In Hanover, for instance, 42 out of approximately 105 adult women (40 percent) were employed for pay in 1930—a fairly high number. In Santa Rita, by contrast, only 117 out of approximately 1,100 adult women (11 percent) were so employed.84 As Table 2 shows, those women who worked for wages in Santa Rita and Hanover in 1930 were primarily in the service sector, if they were Mexican American, and in the professional sector, if they were Anglo.

Table 2. Employed Women, Santa Rita and Hanover, N.M., 1930 | |||||

| |||||

| Sector | Santa Rita | Hanover | |||

|

|

||||

| Mexican | Anglo | Black | Mexican | Anglo | |

| |||||

| Servicea | 58 | 12 | 1b | 12 | 3 |

| Sales (in store or house-to-house) | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clericalc | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Agricultured | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Labore | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Landlady (apartments) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Professionalf | 3g | 22 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Total, by town and ethnicity | 66 | 50 | 1 | 19 | 23 |

| Total, by town | 117 | 42 | |||

| |||||

Source: 1930 manuscript census, New Mexico, Grant County, Precincts 11, 13, and 16 (Hanover, Vanadium, Bayard Station, and Santa Rita).

a Service includes servant, maid, waitress, dishwasher, cook, washwoman, housekeeper, boardinghouse keeper, dental assistant, and beauty specialist.

b Wife of a gardener; the couple worked for John Sully.

c Clerical includes clerk, stenographer, telephone operator, bookkeeper, office manager, railroad agent, postmistress, and census enumerator.

d Agriculture includes ranch helper and farmer.

e Labor includes seamstress, laundry laborer, and railroad brakeman.

f Professional includes teacher, school principal, school superintendent, nurse, and religious practitioner.

g Includes two teachers, both of whom taught Spanish in a private school.

The differences between Hanover and Santa Rita might be related to another difference: the number of female-headed households.85 Santa Rita, with ten times the population of Hanover, had slightly fewer female-headed households than that town, sixteen in Santa Rita, compared to eighteen in Hanover. In both towns, most female heads of households were widows—itself evidence of how little shielded women actually were from the ravages of industrial mining—but the ethnic compositions were almost mirror opposites of each other. Fourteen (88 percent) of Santa Rita’s female heads were Anglo, compared to only three (17 percent) of Hanover’s female heads. Fewer female-headed households in Santa Rita might account for a lower labor force participation rate; it leaves open, of course, why there was such a big gap between otherwise similar towns. It is possible that in this stricter company town, it was harder for women to keep their houses or leases if the male mine employee left or died. I return to the issue of women’s employment in Chapter 6.

THE SOCIAL GEOGRAPHY OF MINING TOWNS

In order to attract the kind of miners the companies wanted—men who would come to remote areas, who would not disappear at the rumor of better mines elsewhere—many companies in the 1910s and 1920s built towns to house workers and their families; if miners lived with their families, perhaps they would find it harder to leave. Companies’ control over housing often meant control over many aspects of a mining family’s life, although this power was not always bluntly exercised.86 Grant County’s mining towns fell along a spectrum, from towns owned outright by Chino (Santa Rita and Hurley), to towns where more than one company operated mines and owned housing (Hanover and Vanadium), to relatively independent towns (Bayard and Central). These towns kept their basic characters through the mid-1950s, when Kennecott dramatically changed the landscape by selling off the towns of Santa Rita and Hurley.

Daniel Jackling’s vision of a vast system of interlocking parts had a local component in the paternalism he and Sully used to organize Chino’s production and housing. The company would care for its employees as a father would care for his children. Once Sully started open-pit mining, he found that he needed “to take care of a great number of employees . . . at Santa Rita and Hurley.”87 His solution was to build towns. Santa Rita already existed, but the company razed all the buildings to start from scratch. Hurley—site of the company’s mill and, beginning in 1939, its smelter—was merely a railroad depot until Sully laid a grid of streets. In both places, the company “built a large number of comfortable houses,” mostly for the Anglos.88 It leased land instead to Mexicans, who built their own houses in Santa Rita’s Mexican Town and in North Hurley. Chino also owned the schools and paid the teachers, owned the mercantile store, owned the hospital and hired its doctors, and hired the deputy sheriff and the mortician. Chino owned everything.

Empire Zinc did not build the town of Hanover, which had instead been built on Henkel’s $47,000 investment in the 1850s, and the company was not the sole operation, for Peru Mining Company and Blackhawk Mining Company came to employ many people there from the 1920s onward.89 In these respects, Hanover was what historians Yvette Huginnie and Elizabeth Jameson have called “semi-independent” towns.90 But Empire Zinc nevertheless made its mark: its officials served on the school board, it owned many of the houses, and by 1920 its wage workers (almost all Mexican or Mexican American) had replaced the hundred or so Anglo miners and ranchers, none of whom worked for wages, who had lived there in 1910.91

Services in these mining towns were marked by racial distinctions, which corresponded closely to class distinctions. Santa Rita and Hurley were both segregated from the very beginning. The “comfortable houses” that Sully built were indeed comfortable: they were “lighted by electricity and furnished with water and connected with sewer systems,” amenities that were even more impressive for a remote area in 1910.92 But only Anglos could rent those houses. Mexicans typically lived in the houses they could afford to build on the lots they could afford to rent. Bill Wood’s family, for example, lived in the three-room house that his father built out of one-by-twelve boards and one-by-four slats, filled in with construction cardboard.93 Similarly, Arturo Flores grew up in a house his family built out of wood boards, two-by-fours, and cardboard.94 Empire Zinc striker and Auxiliary 209 president Mariana Ramírez bitterly remembered growing up in Hurley, where her father worked for $2.40 a day: “On the north side of the tracks the Negro and Mexican-American people lived in shacks. The Anglos had company-built dormitories and no Mexicans were allowed on the South (Anglo) side after nine o’clock. No Mexican-American family was allowed to entertain at his house, unless permitted by the Justice of Peace. . . . You could even hear the Anglo kids say that on the North side of the tracks live the bad and mean people. They picked this up from the grownups.”95 Similarly, Hanover’s Mexican residents typically paid less rent than Anglos did. The rent differential, however, did not reflect the company’s special concern for Mexicans so much as the inferior quality of the property available on the Mexican wage.96

Occupational segregation in Grant County’s mining towns was extremely rigid, and geographical segregation was almost as much so. On this foundation grew a social segregation that all residents, Anglo and Mexican American alike, perceived from childhood onward. It was apparent in schools, churches, civic organizations, and recreation, and it was reinforced by the local political structures that favored Anglo over Mexican American in almost all arenas.97 Santa Rita, Hurley, and Silver City schools were segregated through the third grade, while Bayard, Hanover, and Central schools were too small to provide separate facilities for Anglos and Mexican Americans. St. Mary’s Academy, a Catholic school in Silver City, served both Mexican American and Anglo youth. Aurora Chávez and Alice Sandoval both recalled that the Santa Rita schools and Hurley High School had separate bathrooms and drinking fountains for Mexican and Anglo students.98 Whether integrated or not, students quickly learned central facts about the relative value of Anglo and Mexican culture: the teachers and principals were all Anglo, with very few exceptions, and students were discouraged from if not outright punished for speaking Spanish on school property.99 And while Spanish-named students were the majority of eighth grade graduates, they were the minority of high school graduates. Mexican students, for whatever reason, were less likely to graduate from high school than were their Anglo counterparts.100 Many Mexican American boys, of course, expected to work in the mines, and they stayed in school only until they were old enough to work. “According to legend,” Chino labor relations manager Bernard Himes recalled, “a company official, driving by a school playground that was segregated for those of Mexican descent, remarked, companionably, ‘There’s my next generation of track laborers.’”101

Social and civic organizations were similarly segregated. Fraternal organizations, which represent the kind of social and economic ties people make with one another, rarely crossed ethnic lines, although they frequently included both small businesspeople and skilled workers: Elks, Eagles, Masons (and their ladies’ auxiliaries, too) admitted only Anglos to their brotherhood; the Alianza Hispano Americana and the Catholic Youth Organization served social and insurance needs of the Mexican Americans.102 These same patterns were established among youth; Girl Scout and Boy Scout troops generally had either Anglo or Spanish-named members, with only a few—like the Girl Scout troop at St. Mary’s—including both.103 Religious communities paralleled the civic organizations. Few Mexican Americans belonged to Protestant denominations, although Baptists and Methodists occasionally held services in Spanish for their congregants. Both Anglos (or, more accurately, Irish) and Mexican Americans belonged to the Catholic Church; Central and Silver City’s parishes seem to have consisted of both groups, but the smaller parishes, like Hanover’s Holy Family Church, were mostly Mexican Americans.

Recreation was often segregated. Movie theaters seated Mexican Americans apart from Anglos, although some Mexican American moviegoers refused to obey this informal rule, and dances were usually advertised as “Anglo-American” or “Spanish American,” with an occasional “Everyone Welcome” notice appearing after World War II.104 The swimming pool in Hurley was reserved for Anglos until Sunday, when Mexican Americans were allowed to swim—just before the pool was cleaned for the week. Sports, however, proved to be one arena in which Mexican Americans and Anglos participated together; company baseball teams were integrated and very popular among both groups of people.

Grant County’s political structure favored Anglo over Mexican American in almost every realm. Poll captains and election judges, who did not necessarily wield concrete power but were well integrated into the local political machinery, were almost all Anglo in Grant County through the 1940s. The few exceptions—in one Silver City precinct, in North Hurley, in Fierro, and in some towns on the Mimbres River—only proved the rule that Mexican Americans rarely laid claim to the workings of electoral politics. In 1951, when precincts in Hurley and Silver City were integrated, Mexican Americans disappeared from election boards altogether.105 Mexican Americans were important to county politics because they voted, but they rarely held elected office in the political, law enforcement, or judicial arenas.106 From county commissioners to mayors to justices of the peace, almost all elected officials were Anglo in the 1940s. Exceptions were the constables of Hanover and Fierro throughout the 1940s, and one member of Bayard’s town council in 1950.107 Moreover, almost all of the Anglo local officials came from local commerce. Finally, Anglos always outnumbered Mexican Americans on the juries of New Mexico’s Sixth District Court during the 1940s; out of the typical pool of thirty-six jurors, no more than eight ever had Spanish names.108

The sharp lines between Anglo and Mexican were occasionally blurred, however, by intermarriage. William Villines, for example, was the son of a French German father and a Cherokee mother. Villines married a woman named Margarita, herself the daughter of a Mexican man and an Apache woman. While Margarita bore and raised twenty-one children, William worked as a hoistman.109 Jim Blair was a Texan who drifted into Grant County late in the nineteenth century, working first as a saloon piano player, then as Grant County’s sheriff, and finally as Santa Rita’s deputy sheriff. He and his family, as well as his brother John, who lived next door, lived in a Mexican American neighborhood (named Blair Hill), probably because they had both married Mexican women. Whatever the conflicts between Anglo and Mexican in Santa Rita, Jim Blair was a force for conciliation. Many Mexican Americans remember him as an especially fair lawman; the fact that he stands out only emphasizes that intolerance was the norm. Mexican American and Anglo women alike called on him during domestic disputes.110 William Fletcher was born in 1881 in New Mexico. Early in the twentieth century he married a Mexican-born woman named Abigail. By 1920, the Fletchers, with five children, were living in Hanover, where William was a foreman in a zinc mine. They owned their own home free of mortgage. But when their son Frank entered the labor market in the 1940s, he found that the Mexican part of his parentage outweighed the Anglo part. He was given a job as a shop laborer.111

Paternalism was a system that partly rested on managers’ personal acquaintance with workers. At first the managers knew each man by name, but in later years all hiring and firing was done at a lower level. Daniel Jackling was proud of his own working-class origins, and he used that to make connections of some sort to the workers.112 Pride in his humble origins did not make him humble, though. He cut a grand figure, sweeping into town a few times a year in his personal Pullman car, the Cyprus, which also brought his wife, his valet, his male secretary, and several other servants.113 Hurley and Santa Rita would crackle with excitement at Jackling’s arrival. After meeting with the local management, Jackling and his family would typically stay at Hub Estes’s ranch near Whitewater, where Jackling and prominent local men—the district judge, other mine owners, Chino’s higher management—would go big game hunting.114 John Sully was a bit more modest in comportment, and many workers and residents found him quite approachable and easygoing.115

Grant County’s paternalist mine managers frowned on collective action by workers and successfully resisted unions until the 1940s. Unionism, in the eyes of managers like John Sully and Daniel Jackling, was only ingratitude for all the good things the company did and gave. There is little evidence that unions made much of an impact in the copper or zinc camps during the 1910s and 1920s, although that did not keep management from worrying about them. Steam shovelers struck unsuccessfully in 1912 and lost their jobs to men the company had brought from elsewhere. The strikers left town, although it is unclear whether they left voluntarily or by force.116 But mining companies were not above using force. In July 1917, at the height of a strike against the Phelps-Dodge Company in Bisbee, Arizona, the sheriff and his “citizen’s alliance” rounded up a hundred strikers—many of them members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or Wobblies—boarded them on trains, and sent them east across the New Mexico border, depositing them in the desert near Columbus.117 This dramatic event reverberated in Grant County’s mining district, where Sheriff Herbert McGrath was eager to take a stand against radicals, too. There were no Wobblies to speak of in Grant County, though, and apparently too few labor agitators to be rounded up under the pretense of protecting the citizens against Wobblies. Farther north, however, the Gallup (New Mexico) American Coal Company, a subsidiary of Utah Copper Corporation, staged its own deportation of thirty-four radicals for having in their possession “inflammatory literature” or belonging to the IWW. This action received less local support, however, because the United Mine Workers, which represented coal miners, mounted a powerful protest that also served to dissociate itself from the IWW.118 Elsewhere in Jackling’s mining empire, labor strife met with severe repression.119

What mine managers wanted did not change in the 1930s, but their ability to impose it did. With the help of a revitalized Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers Union and federal legislation sanctioning union organization, Grant County miners would begin to challenge the paternalist dual-wage system during the Great Depression, enjoy new successes during World War II, and face renewed opposition after the war. The Empire Zinc strike of 1950 culminated almost twenty years of this struggle across changing political terrains.