5 Political Consciousness and Community Formation

ON THE PICKET LINES

The road was about fifteen feet wide, unpaved, uneven. It was an easy walk in work boots but a little trickier in ladies’ shoes, especially in predawn darkness. Older women held the arms of their neighbors, sisters, or daughters as they walked to a hut within sight of the massive headframe above Empire Zinc’s mine. From down the road came cars, one or two at a time, slowing and then edging off the road to park; more women and kids got out and joined the group at picket headquarters. The picket captain took charge and formed them into a circle in the middle of the road. As the sun came up the women’s picket was well under way.

Dolores Jiménez was one of the women who had come from a distance, carpooling with neighbors for the twelve-mile drive north from Hurley. Her husband, Frank, worked at Kennecott, but she had heard about the Empire Zinc strike and its need for women’s help, and she had been encouraged to join by her friend Clorinda Alderette. Dolores was young, just twenty-one, but already had two sons under the age of five. It would have been harder to go to the picket that morning had not another woman, a grandmother herself and “not even from working people,” offered to watch the children.1 Other women had children they could still carry, but some picketers, like Anita Torrez, who brought her infant daughter, soon found it very tiring to hold a child while walking all day. The best situation was to have children who no longer needed constant attention, like Daría Chávez’s two teenaged sons. It was her family situation as much as her skill and enthusiasm that made Chávez one of the picket captains; her sister, Elena Tafoya, found it next to impossible to go to the picket with her many children under age ten.2

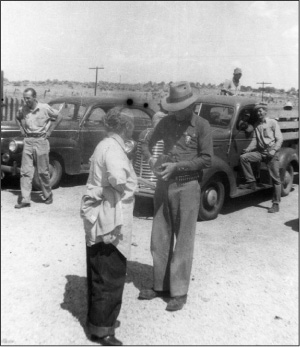

Women picketing, with men and women on the hillside nearby, summer 1951. Photo courtesy of Luis Ignacio Quiñones.

Beyond the circle of women and children, against a hill by the road, stood a group of men. These were fellow strikers waiting to see if the new strategy would work; they were also husbands and brothers and fathers, waiting to see how their women would behave. The picketers walked “in circles and circles and circles,” Dolores Jiménez later recalled, “talking, laughing, singing.”3 They sang “our ‘Solidarity Forever,’ our union songs” as they walked—or danced, when some men brought guitars to the picket.4 Some crocheted or knitted. It was, Henrietta Williams thought, the most beautiful thing she had ever seen.5

But before the festive mood set in fully, more cars arrived, this time carrying Sheriff Goforth, his twenty-four deputies, and the handful of men who wanted to cross the picket line to work at Empire Zinc. Climbing out of his car, Goforth saw women where there should have been men. Some were no doubt familiar to him; Elvira Molano had been arrested two days before, and Virginia Jencks was already well known. But most were strangers, all were women, and Goforth did not quite know what to do. He may have been among the county officials who “opined that the women were not technically union members and therefore would not be affected by [Judge] Marshall’s order.”6 In any case, he chose to watch carefully rather than act hastily, and the Silver City Daily Press reported that “quiet was the rule” on the picket that day.7

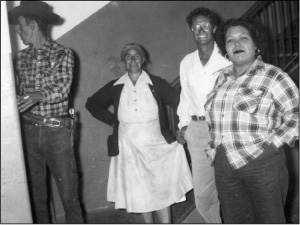

Women picketers trying to shame strikebreakers. Photo courtesy of Luis Ignacio Quiñones.

The strikebreakers were probably also surprised by the women’s picket. To Anglos like Grant Blaine or Denzil Hartless, the women were unfamiliar, distinguishable one from the other only by age.8 Hartless lived in Hanover, but he lived with his family in the Anglo section and probably had little reason to visit the other side of town. Only seventeen years old, he had left school after eighth grade and was working with his brother Carl digging ditches when Empire Zinc announced that it would reopen in June 1951.9 The two brothers simply saw this as a way to earn some money, not as the start of a career in mining; in Carl’s case, he was waiting for induction into the army.10

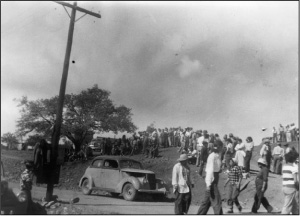

Strikebreakers trying to go onto the Empire Zinc property, summer 1951. Photo courtesy of Luis Ignacio Quiñones.

Unlike their Anglo counterparts, Mexican American strikebreakers like Francisco Franco and Jesús Avalos came from the same community as the picketers. Franco had lived in Hanover and the nearby village of Fierro since at least 1939, and Avalos had even been a steward in Local 890—that is, until the union suspended him for helping the company organize its back-to-work movement in April 1951.11 These two men became special objects of the women’s derision as the strike went on, and they responded with insults, abuse, and, at one point, a shotgun.

Things heated up the second day of the picket, when strikebreakers tried, and mostly failed, to sneak onto the company property. Women may have had “problems catching the sneaking scabs, crawling through the pine trees,” but few strikebreakers, if any, slipped through their grasp.12 That night, June 14, women swept into the union hall, eager to tell stories of the picket. “No scabs were crossing our lines,” Aurora Chávez announced. Elvira Molano and Daría Chávez exhorted the assembled women—“We don’t need men”—to join the picket the next morning. The hundreds who answered their call found the pickets an exciting place to be.

The women’s picket, from June 13 until the end of the strike the following January, generated tremendous solidarity. Violent conflict with strikebreakers showed women a collective strength that did not depend on men. On June 15, for example, the strikebreakers were ready to act forcefully against the picketers. Jesús Avalos tried to drive through the line, but the women and children threw rocks and pushed his car back. Grant Blaine and Denzil Hartless tried to move through on foot, but the picketers “grabbed them and tore their shirts.”13 Most of the time, certainly, life on the picket was routine: day after day of walking in circles, making lunches in the picket hut, writing letters to the newspaper, apportioning strike rations. But these activities built the framework for catalyzing, interpreting, and responding to events that were quite out of the ordinary; they required women to organize, and the strength of their organization became apparent in the moments of intense conflict that punctuated the long stretches of routine picketing. Furthermore, by calling into question the injunction’s scope, the women created a backdrop of legal uncertainty against which the confrontation between the picketers and the strikebreakers played out while the enforcers of the law could only stand back and wait for the courts to clarify the bounds of their authority. By the time the legal authorities caught up with them—extending the injunction, issuing warrants, making arrests, and hauling them off to jail—the women had gained the collective strength to resist new legal measures. They had filled a legal vacuum with their own solidarity.

The reactions of local police and the courts to picket violence further convinced women picketers that those authorities were aligned with the mining companies and therefore corrupt. This distilled the contest down to one between an illegitimate power structure and a righteous union community. Picketers’ confrontations with deputies and judges were confrontations with the institutions of political power, and they generated more than solidarity: they carried lessons about power itself. The women’s picket stripped away the mask of power. Women were not just asserting that different people should occupy the positions of power in Grant County. They were reinvigorating the very concept of legitimacy, basing it in what they considered true justice.14

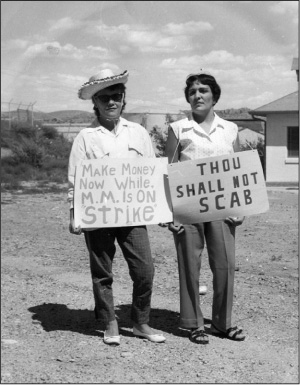

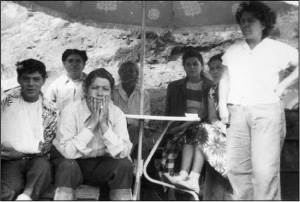

Women and children near the picket line, summer 1951. Rudy Chapin, age fourteen, is seated at far left; Daría Chávez, picket captain, is standing at far right. Photo courtesy of Luis Ignacio Quiñones.

As the Empire Zinc picketers were marking the lines between themselves and their opponents, they found support among many local merchants and businesspeople, but other people increasingly found themselves alienated from the strikers who, opponents believed, were disrupting the community by following the instructions of outsiders. Opponents of the strike were outraged at women’s behavior. They laid claim to the legitimacy of citizenship and denied it to the strikers, a denial that drew upon both anticommunism (communists were “un-American”) and racism. Alignments gradually hardened over the summer, and by autumn they were explicit, emerging generally, but not always, along ethnic and class lines and finding expression in debates over communism.

JOCKEYING FOR POSITION

By June 15, Sheriff Goforth had gotten over his surprise at seeing the women on the line. That day, District Attorney Tom Foy issued warrants to arrest six women and ordered Goforth to break up the road blocks so that cars with replacement workers could reach the Empire Zinc mine. The following morning, Goforth tried to clear the road. Three women threw rocks at one car, and a deputy pushed Virginia Chacón out of the way of strikebreaker Francisco Franco’s car. “So the rest of the women went around me and pushed the car—it was not very far,” Chacón recounted. “[They pushed it] back and the other ladies were running up . . . to put [some rocks] on the sides of the road so the car would not go by. And these scabs were pretty much mad at us, were very angry and began calling us names, and were just dirty to us.”15 The women “surrounded the deputies and pushed the car back down the road to an intersection.”16

Around 10 A.M., the sheriff and his deputies raised the stakes. “[They] took red-covered tear gas grenades, held them in their hands and looked toward the picket line, which consisted then of women and children. Men . . . sat or moved about on the hillside above the road.”17 Into this tense scene a deputy “let go one of the gas grenades. It skewered and rolled among the pickets, spewing the white gas and dispersing the screaming women.” But the wind was in the pickets’ favor, and they soon reorganized their line.18 On a hill, “about a hundred women and children . . . cursed and jeered the sheriff. . . . For a moment officers feared violence.”19

The officers had, of course, committed some of the violence, but Goforth moved in to arrest as many women as he could haul away, in a manner that would later be quite faithfully depicted in Salt of the Earth.20 Once arrested, the women did not resist the deputies. “But until the moment of arrest, sheriff’s deputies said, they resisted bitterly.”21 Three carloads of women and children, with Goforth scrambling to round up a school bus for more arrests, made their way to the Grant County jail, which adjoined the courthouse in Silver City. Goforth’s arrests, though, did not disperse the picket line; some 300 women remained on the line in Hanover. Lucy Montoya was “proud to be the one who started the second picket line . . . after the D[istrict] A[ttorney]’s gunmen broke [the] first one.”22 “We can keep arresting them,” Undersheriff Lewis Brown remarked, “but they keep moving in. We could clear the road, but someone would be hurt in the process.”23

Fifty-three women were ultimately arrested, and they took their children to jail with them. Braulia Velásquez carried her newborn infant; most of the kids were between the ages of six and ten. Virginia Chacón had never seen the inside of a jail before and was very nervous at first. But when the sheriff told them they could leave if they agreed not to return to the picket, she recounted, “we all responded at the same time we would not go home, we would go back to the picket lines and help our strikers, help our union members.”24 The women refused to leave individually on bail or to make any deals with the district attorney.25 After that, the women “had a very good time” playing cards, singing, and making “all kinds of noise.”26

The jail cells were filthy and the food unappealing. “All we had for lunch,” Virginia Jencks complained, “was cold beans and a few loaves of bread we couldn’t eat.”27 Union attorney David Serna sent food and soft drinks, which jailer Jim Hiler refused to deliver because “orange peelings stop[ped] up prison plumbing and jail rules forb[ade] glass bottles.” (Hiler finally ladled soda from a bucket.)28 Children posed special problems; one had a nosebleed, and Braulia Velásquez’s infant cried for its formula.29 The women made such a racket in the county jail—“the worst mess” that Hiler had ever seen—that Goforth released them that night. “It looks like an endless job,” he admitted.30 And it was. The women returned to the picket that night and the following morning, setting up a picket tent with a stove, cots, and food: a home away from home.31

Women’s festive and resolute solidarity blossomed in these new circumstances, but it had grown out of their recent history of organizing themselves as miners’ wives. The sheriff’s offer to release them provided they not return to the picket, for instance, sparked an immediate response—rejection—because the women already knew and trusted each other, and their ultimate victory over the sheriff deepened their faith in one another and in their collective endeavor. The national press failed to perceive the level of organization that permitted women to launch a jail protest. The New York Times, for instance, described the women’s resistance to police on the line as “screeches and fingernail attacks,” conveying a picture of wild animals.32 The Communist Party (CP) press also tended to play up the spontaneous and spectacular elements of the jail scene, although it did mention in a light-hearted way that the “wives and children of the miners organized themselves even in jail.”33 The sympathetic CP press reacted to the unusual situation with outrage at the brutality, but it also reported with humor the incongruity of women taking on the local authorities.

Women’s organization enabled them to respond to the threats from outside, the most important of which was direct, physical violence, and they often responded violently themselves. Throughout the summer of 1951, violence continued to characterize the relations between the picketers and the sheriff, his deputies, and strikebreakers. These episodes solidified the community spirit that animated the pickets. As Anita Torrez reflected many years later, “At the moment when the ladies took over, there was a lot of fear. [But] being among these women every day, . . . more ladies were eager to participate, [and] we gained confidence. [There was] a moment when you let go of your own fear.”34 In fact, she commented, “once the violence started, everybody wanted to be there. Everyone.”35 The cumulative effect of this violence was not to inure people to it, to make them dismiss it as constituting the normal course of events, but rather to see in its very unexpectedness and intensity the embodiment of the true nature of local power. It sharpened tensions and raised union complaints against local officials to a higher pitch, even as it ennobled the women whose valor was on public display.

To legal authorities like Silver City justice of the peace Andrew Haugland and Sixth District judge A. W. Marshall, these women were far from noble. The scene on the picket line was chaotic, disruptive, and fundamentally at odds with the law and order the judges were bent on enforcing. And to bring that scene into the courthouse, as a hundred picketers and their supporters did on June 18, was truly shocking. That morning, forty-five of the jailed women were scheduled for arraignment, and they “jammed the courthouse corridors” waiting for Haugland to open court. “It’s like a picnic,” said one woman. “We’re having fun—and we’re going to stay on the picket line, too.”36 District Attorney Tom Foy had decided not to charge anyone younger than sixteen, and one younger girl complained, “But I fought the sheriffs. I fought ’em good. I hit one real hard and I spit in another’s eye.”37 Recording the deputies’ complaints and finding all of the arraignees delayed the hearings by almost two hours, and Haugland, a sober Methodist, must have been grinding his teeth by the time the women entered his courtroom in groups of five.38 All pleaded not guilty. Haugland released them on their own cognizance and ordered them bound for district court. Their case then moved into the jurisdiction of Judge Marshall, who “took elaborate precautions to prevent any outbursts of sentiment during the hearing” on June 21: no photographs, no radio broadcast, no overflow crowd on the floor where the courtroom was located, no standing-room visitors, no entering or leaving during recesses. And no children.39

On June 29, in a separate legal case, Judge Marshall decided that the temporary restraining order against the mine workers also covered women and children as agents of the union, and on July 9 he made that injunction permanent.40 But the new ruling did not cause the same dilemma as the temporary injunction had done on June 12. The women’s picket had taken the sheriff and company by surprise; this surprise resulted in a power vacuum that women filled through their numbers, particularly during and after being jailed, and through their solidarity. The point at which Marshall ruled that the injunction covered women and children came after women had shown the futility of mass arrests: women had changed the terms of the conflict. For their part, law enforcement officials took from this the lesson that women were acting outside the law, and when those officials reasserted power, it was more closely and obviously connected to the company’s agenda. This convinced women of the corruption of legal authority and the righteousness of their own cause.

PICKETERS, STRIKEBREAKERS, AND SHERIFF’S DEPUTIES

Failing to stop the women’s picket, the permanent injunction instead prompted a new round of picket-line clashes. Whenever violence broke out on the lines, women mobilized car caravans to bring more people to the lines, and children walked out of school to join their parents.41 Some 300 women showed up on July 11, the day the permanent injunction took effect, to defy the order and confront the strikebreakers, who were escorted by several deputies. Strikebreaker Grant Blaine, who had apparently made it into the Empire Zinc mine and done a day’s work, “was inching his way out [in his car] when one woman threw a rock and broke his windshield.”42 Deputy Robert (Bobby) Capshaw tried to arrest her but found himself “ganged up by several others,” according to Sheriff Goforth. One of them, Mrs. Antonio Rivera, even managed to seize Capshaw’s blackjack. Then “the whole bunch ganged up on about seven deputies and the battle wound up as a standoff.”43

This was not what Bobby Capshaw had signed on for. He was twenty-two years old when Sheriff Goforth assembled his deputy force in June. He was not a miner himself, but he had lived in several Grant County towns while growing up and knew the district well. His family had moved to Santa Rita in the mid-1930s when his father, Jessie, could no longer find work in Oklahoma’s lead-mining district. Jessie Capshaw was killed in a mine explosion in 1939, leaving his wife, Ann, with six children (fortunately, the two eldest were adults) and fifty dollars a month from Chino.44 Ann took a correspondence nursing course and got a job at Fort Bayard Hospital, and she also got the help of her brother-in-law and of Tom Foy to build a house in Whiskey Creek. Ann remarried, and early in the war the family moved to San Diego, where Bobby’s brother Ross was stationed in the navy and his stepfather worked in the shipyards. Bobby and his brother Dorman soon returned to Grant County alone. By the time the Empire Zinc strike began, their mother and sister had also come back to Grant County, and it is possible that Ann’s work for Tom Foy’s 1948 campaign for district attorney brought Bobby to Foy’s and Goforth’s attention.45

Picketers especially disliked Deputy Marvin Mosely. On July 12, he drove his green Buick into the picket line and struck fourteen-year-old Rachel Juárez, Aurora Chávez’s younger sister. Mosely claimed that Juárez “deliberately threw herself on the left fender of my car. I stopped to get her off and she cussed me.”46 Mosely had particularly bad relations with Elvira Molano, the picketer who had landed herself in jail even before the women had taken over. Molano refused to go to jail on July 20 without her children. Silver City justice of the peace Andrew Haugland, who had ordered Molano committed in lieu of $500 bond, told Mosely, “The children stay out. You take as many men as you think you need and put her in jail.”47 Mosely successfully got her to the door of the jail when his luck ran out and Molano fought back. Later she claimed that a peace officer, presumably Mosely, had spanked one of her children, and in retaliation she “‘spanked him in the face and then . . . gave him this.’ She swung her foot in a high kick and indicated she was aiming for the groin.”48

Even away from the picket line, strikers faced violence. Tomás Carrillo, a child at the time of the Empire Zinc strike, was awakened one night by a knock at the door. “My stepmother asked, ‘Who is it?’ No answer. ‘¿Quién es?’ No answer. My bedroom was right there, and I saw a man, a silhouette, in the light of the moon. I knew if I moved the guy would think I was my dad and he’d shoot me. My dad had a rifle, and he said, ‘Who is it? If you don’t tell me I’ll blow your head off,’ and boom—the man took off.”49 In another incident, strikers Henry and Anselma Polanco were driving to the Hanover picket on August 21 when a car driven by Francisco Franco hit and overturned their vehicle. They claimed that Franco hit them deliberately; Franco denied it, telling Assistant District Attorney Vincent Vesely that “he didn’t know of the accident until he looked behind him and saw Polanco’s car rolling along the highway.”50 Mine-Mill union men saw the incident and drove the couple to the Silver City hospital, where both were treated for severe bruises; Henry Polanco suffered serious cuts and a broken ankle as well. Franco and his passenger, Marvin Mosely, continued on to the picket and, according to the union, taunted the women there with obscenities.51

Obscenities were directed at other pickets as well. Pete Loya and Denzil Hartless, both working inside the Empire Zinc plant, were charged with separate counts of “indecent exposure in the presence of minors” on August 18, 1951. Loya and Hartless were alleged to have exposed themselves to a group of children on the picket line on August 8, and Loya was also charged with having done so on July 22 near his home, “in front of a group of minor girls.” Both pleaded not guilty and were held in bond of $1,000 each; a few weeks later, charges against Hartless were dropped but Loya was ordered held for district court.52

Of course, picketers committed violence as well. Five men attacked Luis Hinojosa, a strikebreaker, and there is some question of whether they also attacked his pregnant wife when the couple was leaving the Empire Zinc area. Women threw red pepper on the strikebreakers and poked them with straight pins. Children threw rocks at strikebreakers, and they sabotaged strikebreakers’ cars by burying boards with nails in the dirt roads and by stuffing gas tanks with tailings from the mine.53

An even more serious conflict flared on August 23. Five cars of strikebreakers approached the picket line, which was blocking the road with about forty women and children. “The cars neared the line and stopped,” according to the Silver City Daily Press. “Then, bumper to bumper, they moved into the picket line as the pickets struggled to hold the cars back.”54 One car and a pickup truck made it through the line, and in the meantime four pickets were seriously injured. Consuelo Martínez, who was with her five children, had her leg broken when a car ran over it, and another car ran down Bersabé Yguado, who had been sitting on a bench some ten feet from the side of the road.55 Martínez reportedly lay on the ground for forty-five minutes. A call to the Kennecott hospital at Santa Rita, which residents not associated with the company had often used for emergencies, met with flat refusal to send an ambulance: “If this call is for the pickets,” the hospital spokesperson allegedly declared, “we have no ambulance. The pickets will have to take care of themselves.”56

For the first time, guns were used for more than show. One strikebreaker “jumped out of the car with a gun in his hand and began shooting” at the women.57 He wounded thirty-four-year-old Augustín Martínez, a war veteran who had been discharged from the army just nine days earlier.58 And, according to a Mine-Mill Civil Rights Committee report from late September, for the first time a woman joined the attack: A “gunman woman by the name of Mrs. Clanton,” the report claimed, exchanged blows with a woman picketer after first “trying to stomp” on Rachel Juárez, who was injured again after having been hit by a car a month earlier.59

The events of August 23 came just days before Mine-Mill was scheduled to begin a nationwide strike in the copper industry. Local 890’s Kennecott and Asarco units had voted early in the month to join that strike, set for August 27, but the violence on the Empire Zinc picket prompted 1,400 members of Local 890 to walk out several days early. The union issued a call for reinforcements over radio station KSIL, and, according to the managers of three companies, men walked off the job by noon.60 By that point, Local 890 had held two emergency meetings to set up strike committees. In Grant County, AFL and CIO unions observed the pickets, but elsewhere in the nation those unions crossed the picket lines in order to deliberately weaken Mine-Mill. The relative respect shown Mine-Mill in Grant County suggests that CIO and AFL workers were disgusted at the violence directed against the Empire Zinc picket.61

All of these events on the picket line convinced picketers that the police were in the company’s pockets. “It took . . . the sheriff department almost twenty-four hours,” Anita Torrez complained, “to approach the scene of the accident where my husband was deliberately run over by a car.”62 Not only did Sheriff Goforth pay the deputies with Empire Zinc money, but the very deputies keeping “order” on the picket line were also sometimes strikebreakers. Daría Chávez was disgusted to see Mosely and Capshaw sneaking to work at Empire Zinc early on the morning of August 10. “It certainly seems funny to us women on the line,” she said, “to see these so-called peace officers, who are supposed to be neutral, now working as scabs. And these are the men the court told us we should respect. . . . They have gone from one dirty job to another. What could be lower than a scab?”63 After a court hearing in which Marvin Mosely was acquitted of assault charges, Elvira Molano commented, “I had never in my life been involved in courts or the law until the Empire Zinc strike. I thought the law of Grant County was to protect us, not throw us in jail like animals and beat us with blackjacks.”64

The picketers did not meekly accept this version of law and order. Around noon on July 21, a hundred men visited Sheriff Goforth in the county courthouse. One man told him, “We want Mosely fired before someone gets hurt”; another reminded him that “we are the ones who put you in office”; and a third explained that Mosely lacked even the qualifications to vote in Grant County, having moved there too recently. “If you keep this man on,” another told him, “there may be trouble.” Goforth

Picketer confronting deputy, possibly Marvin Mosely, who is armed with ammunition and a camera. Deputy Robert Capshaw is standing at far left. Photo courtesy of Luis Ignacio Quiñones.

promised he would meet with them at 2 P.M. From the back of the crowd came one last shout: “If you don’t get him out of there, we will do it!”65 Sheriff Goforth started out of his office, expecting to get lunch, only to find a group of women blocking his way. Elvira Molano pointed at Mosely and declared, “We don’t want him.”66 Then began an even noisier confrontation. The women would not wait until 2 P.M. “Now! Now! Now!” they shouted. Molano called for silence—“Silencia, muchachas”—and one woman tried to explain: “Sheriff Goforth, you’re okay but that man (gesturing to Mosely) isn’t.”67 Sheriff Goforth did not fire any of his deputies, but he did suspend Mosely and Capshaw for a few days late in August.

A picketer (far left) turning the tables on the photo-taking deputy while women pose for another camera. Photo courtesy of Luis Ignacio Quiñones.

PICKETERS AND JUDGES

Alongside the picket-line battles that summer, arrest warrants and court proceedings drained Local 890’s bank account at the same time as they shored up people’s resolve. In almost every instance, the local justice of the peace, whether in Bayard or Silver City, and the district judge ruled against the union and its members. Justice of the Peace Andrew Haug-land routinely dismissed charges that picketers brought against the deputies, and sometimes he went a step further by criticizing or punishing the complainants instead. On August 8, for example, not only did he dismiss the women picketers’ assault charges against Marvin Mosely and Robert Capshaw, but he also commended the deputies. The complainants had not “come to the court with clean hands,” he explained, “and any injuries [they] may have sustained they brot [sic] on themselves.”68 Haugland dismissed assault charges brought against Mosely by Rachel Juárez’s parents, explaining that the charges were based on hearsay, and, according to the union, he then cited her parents for “contributing to the delinquency of a minor by permitting her to go to the picketlines.”69

The justice of the peace is a holdover from the English common law, hearing charges of minor crimes and either ruling on them right away or sending the alleged miscreants to district court. Into his office (often his home), the sheriff or deputy brought a string of people arrested for drunkenness, fighting, petty larceny, juvenile delinquency, burglary, or just plain disturbing the peace.70 Sometimes the justice of the peace appeared on coroner’s juries, too. The office required no formal training. Mexican Americans seldom served as justices of the peace, but they were elected constable in several Grant County towns. The men—and it was almost always men—typically came from the ranks of small business or the professions, and in Grant County they were elected every two years.71

It should come as little surprise that many Grant County justices came from the mining industry, whether as managers or as people with their hands in one or two mining ventures alongside their main occupation. But it is somewhat surprising to find that wage workers held court as justices of the peace. Bob Brewington of Hanover, for example, served as justice from at least 1947 to 1951 while still working for Empire Zinc.72 But Brewington did not exercise jurisdiction over the cases that came out of the Empire Zinc strike.73 Perhaps more palatable to the political leaders of Grant County was Bayard justice of the peace Robert O. Day. Day had been a wage-earner at Chino and a member of Local 890 from 1941 to 1947. He left the mining industry that year and opened a service station. Day was interested in local politics and law enforcement, and in 1950 he was elected justice of the peace in Bayard. Just like Haugland, Day typically ruled against the picketers, dismissing, for example, Elvira Molano’s assault charge brought against Marvin Mosely.74

Also at work in Grant County was the state’s district court, which heard felony cases and was empowered to issue injunctions, as A. W. Marshall did in June and July, and to cite individuals for contempt of court, as he did in July and August. Marshall traveled the circuit of New Mexico’s Sixth District, hearing cases twice a year in Silver City, then moving on to Deming, Socorro, and other county seats. Marshall claimed descent from U.S. Supreme Court justice John Marshall and from pioneering parents in the railroad town of Deming, southwest of Silver City. He had little patience with rabble to begin with, and hearing crowds in the courthouse hall only reinforced his sense that he stood between order and disorder.

Marshall counted among his friends Horace Moses, Chino’s superintendent, Hub Estes, a big rancher, and other men of the local elite. He was probably inclined to support the Empire Zinc Company against picketers because Empire Zinc represented order and property against disorder. This is not to say that the judge was blatantly biased; to the contrary, he would have prided himself on the rational deliberation with which he decided the cases before him. But he moved in the circles of people whose sense of public order was closely bound up with the protection of property. There did not need to be any backroom deals precisely because Grant County’s legal authorities shared with mining managers the worldview in which strikes, by their very nature, ran contrary to how things should be. All of Grant County’s lawyers had ties of one sort or another to mining concerns, whether they were retained as regular counsel for Chino (as was the firm of Woodbury and Shantz) or belonged to the same social, civic, and religious organizations.75

That said, there does seem to have been something of a backroom deal in the meeting that leaders of the Grant County Bar Association held with Judge Marshall shortly before noon on July 23 to “plan an appeal to the governor for aid in preserving peace.”76 That same day, Marshall ruled that Mine-Mill, Local 890, and six local union leaders—all men—were in contempt of court for, as Empire Zinc claimed, violating the June 12 injunction. He fined the international and local unions each $4,000 and sentenced the six members of the bargaining committee to ninety days in the county jail. He said he would suspend the jail sentences and remit half of the fines if the union and its officials obeyed the injunction, and he accepted $8,000 bond from the union and $500 bond each for the individuals.77 By this time, Local 890 had gotten the help of prominent attorney Nathan Witt, who had once served on the National Labor Relations Board and who, during the McCarthy period, defended left-wing unions like Mine-Mill; he was regularly red-baited himself. At the contempt hearing of July 21, Marshall denied Local 890’s motion to dismiss the company’s claim, and the union officials and attorneys walked out of the hearing. Witt told Marshall, “Our clients are convinced that law and order have broken down as far as protecting their lives on the picket line is concerned. Women and children have been thrown into jail on the least excuse and have been held in unreasonable bond. It has come to a point where their confidence in law and order here is broken.”78

Just as in their relations to Sheriff Goforth and his deputies, the picketers became bolder in confronting the county’s political and legal authorities, while those authorities tried harder and harder to control the situation. After the contempt hearing, Local 890 broadcast a call over radio station KSIL for a massive demonstration. Three hundred cars drove into Silver City late that night, horns blaring all the way, and rallied outside the courthouse. A thousand people “gathered on the courthouse lawn to hear the six sentenced members of the bargaining committee and their wives pledge to carry on the fight against Empire Zinc.”79 They carried signs saying “No Marshall Law” and “Fooey on Foy.”

Some of Grant County’s legal authorities were deeply alarmed by the rowdy caravan into Silver City and the union’s inflammatory accusations of corruption. The day after the courthouse rally, Marshall issued another contempt ruling, this time for Mine-Mill, Local 890, Jencks, international treasurer Maurice Travis, and Cipriano Montoya. The ruling concerned two occasions on which the union had criticized the local judiciary. On June 15, Mona Lucero broadcast a union message over radio station KSIL: “They have bought and paid for a restraining order to break our strike. They have failed.”80 And five days later, before a public meeting in the Fierro nightclub, Travis predicted that Empire Zinc would get its permanent injunction: “They’ve got enough people bought off to get it, I think. I think that Brother Witt is the best lawyer in the country. But I also think that if we had three of Brother Witt with us in this thing the company would still get its injunction. The company has enough money to do this. We don’t have that much money.”81 These comments infuriated the president of the Grant County Bar Association, C. C. Royall Sr., who persuaded Marshall to issue the contempt citation. “We lawyers do not intend to stand by and let the courts be insulted and be flaunted,” he said. “We intend to come to the defense of the courts because if we don’t our system of justice will be endangered.”82 To Marshall’s complaint that the Empire Zinc strike was getting out of hand, strike committee chairperson Ernesto Velásquez replied, “The only thing getting out of hand is the eagerness of company bootlickers in politics and at the bar to smash the only organization that has been able to raise the living standards of the working people, especially the Mexican American workers, of Grant County.”83 Local 890 charged the Grant County Bar Association with “unwanted interference” in the strike and wrote to Governor Edwin Mechem to counter the bar association’s alleged misrepresentation of the situation in Grant County.84 Mechem offered to mediate, and Local 890 accepted—but Empire Zinc refused the offer.

Criticism of the union’s radio message extended only to male union officials; the union’s opponents dismissed Mona Lucero’s participation as simply something manipulated by the men. This was a key to the union’s success: women’s participation was highly visible and disruptive at the same time it was not fully comprehensible to the local authorities or to Empire Zinc. As Daría Chávez put it, “The reason the Empire Zinc co. hasn’t noticed the wives of the strikers is because the company need[s] glasses.”85

Local law officials began to employ a new tactic to control the strikers in August: the “peace bond.” If someone (typically a deputy, strikebreaker, or relative of a strikebreaker) declared that a person threatened him or her, a justice of the peace could require the alleged intimidator to post a peace bond. If then, on the word of the complainant, the defendant did anything questionable—arguing with a deputy, for example, or taunting a strikebreaker—the defendant forfeited the peace bond and was jailed. Henrietta Williams, her sister Mary Pérez, Elvira Molano, Sabina Salazar, Fred Barreras, and Antonio Rivera all stayed in jail for a week late in August rather than pay peace bonds, which they understood as a blatant attempt to tie up the union in excessive court costs. “We are the peaceful ones,” they declared from the Grant County jail. “What have we done? The ones breaking the peace around here are those gunmen who have charged us, who come to the lines after working as scabs, and always try to start trouble.”86 A “Citizens’ Committee” petitioned Justice Haug-land to release them without the peace bonds, but he refused. By going to a higher authority—district judge Charles Fowler in Socorro, New Mexico—the six gained release on a writ of habeas corpus. Fowler criticized the peace bonds as “so drastic a restraint of the freedom of individuals that a judge must be scrupulous in seeing that any complaint fulfills exactly all of the requirements of law.”87 Scrupulous the local judiciary was not, and the union strenuously objected to the tenor and outcomes of the court proceedings. It circulated a petition to New Mexico’s attorney general for a grand jury proceeding to address “the atrocities of the District Attorney and the Sheriff of Grant County.”88 For their part, the newly released strikers were strengthened by the experience. Henrietta Williams was “happy to be together with the sisters in the picket line. She [felt] glad and not ashamed of being in jail,” while Sabina Salazar thought that after “staying eight days in jail, she could stay in longer if necessary.” The union supporters voted to extend their August 22 meeting by fifteen minutes, and the four recently jailed women “came up front to sing ‘We Shall Not Be Moved’ in Spanish[,] accompanied on the piano by Brother Juan Antonio.”89

Authorities at some distance from Grant County proved somewhat more even-handed in the course of the strike. U.S. senator James Murray of the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare was “greatly shocked by newspaper accounts of the jailing of pickets, including women and children.” He asked that Senator Hubert Humphrey, of the Senate Subcommittee on Labor and Labor Management Relations, consider investigating the Empire Zinc dispute.90 Governor Mechem, a Republican

Elvira Molano, Fred Barreras, and Sabina Salazar, three of the six picketers jailed on “peace bonds,” in the Grant County courthouse. Deputy Louis Rhea (generously nicknamed “Horseface Rhea”) is at left. Photo courtesy of Luis Ignacio Quiñones.

elected the previous November, was suspicious of communist involvement in the strike, but his actions suggest that he was at least equally suspicious of Empire Zinc’s sincerity in resolving the crisis. He spoke over the radio on July 28, offering to mediate, and while he dispatched the state police on occasion, he never declared martial law, as some Grant County Anglos had asked—and as plenty of earlier governors had done in labor disputes, including Mechem’s own father.91 State police chief Joe Roach, in fact, actually helped restore order in Grant County. He publicly criticized Goforth and Foy for “magnifying minor complaints and . . . criticizing our system. If the condition again gets out of hand,” he continued, “it can in all probability be directly chargeable to the sheriff and the district attorney and this department would rather have no hand in it.”92 It took a judge from Socorro, some 200 miles away, to draw the brakes on the peace bonds. And the National Labor Relations Board indicted the New Jersey Zinc Company for “refusal to bargain” on August 14. This measure did not, of course, force the company to take any action; unlike the injunctions against unions, a Taft-Hartley injunction or ruling against a company carried no enforcement provisions.

THE PICKET SEEN FROM OUTSIDE

The strike reverberated beyond the picket lines in Hanover, forcing people only indirectly connected to the picketers to choose sides. Many believed the union cause was just, the company intransigent, and law enforcement compromised. Late in June 1951, for example, all of Central’s business managers, owners, and operators save one petitioned Empire Zinc to negotiate with the strikers and to fire strikebreakers and armed deputies.93 They accepted the union rationale for the strike and saw their own interests tied to the strength of the union. Gertrude Gibney, a Central hotel proprietress, explained that “the feeling of the business people in the town of Central is that if Empire Zinc cannot do as much for its employees as the other companies in the district do for theirs, they might as well sell out, and let another mining company that knows how to treat its employees try to do a better job.” Grant County would “go backward, instead of forward,” if the company denied the union its demands.94 The company may have prevailed in local courts, local businesspeople intimated, but it was also on trial in the community: “Failing to grant these established district-wide conditions to your employees, your management and company will stand further convicted in the eyes of the people of ours and other communities in this district, as fully responsible for prolonging the strike and for all future violence or bloodshed connected with [the strike].”95

Some businesspeople matched their nominal support with concrete aid. Fred Sullivan, owner of El Zarape nightclub, regularly opened his floor to union meetings and benefits; José Martínez donated food from his two businesses, Mi Ranchito and the Central Commercial Company.96 In September, Gertrude Gibney again came forward for the union, this time testifying before Justice of the Peace Haugland on behalf of Rudy Chapin and his mother. Rudy was a teenager, a regular picketer and, apparently, handy enough with rocks to infuriate Sheriff Goforth’s deputies. He found himself in danger of being sent to the boys’ industrial school (reformatory) at Springer, New Mexico, and Haugland was also considering punishing his mother for contributing to his delinquency. Chapin’s mother was a widow, Gibney explained to Haugland, and she was doing the best she could with her son. It was a hardship for her to report weekly to the juvenile officers because she was sick and on relief and had to travel twenty miles round-trip.97 Gibney probably understood how hard it could be to run a household; she herself had married at age fourteen and by the time she was in her mid-twenties was running a household consisting of two children, her husband Ruben, her father-in-law, and her husband’s cousin.98 In any case, Haugland was unmoved. He was being “extremely lenient,” he replied, and (according to the union’s press release) he “wanted to make it tough for the Chapins.”99

Catholic priests generally supported the strikers, especially Father Francis Smerke of Hanover’s Holy Family Church. On October 14, 1951, for example, he held a special high mass “to pray for the successful conclusion of the . . . strike.”100 Father Smerke had come to this parish in 1948, a time when Mine-Mill was starting to push its agenda beyond the workplace, and his parishioners were almost entirely working-class Mexican Americans. Other Grant County towns, like Santa Rita, Silver City, and Central, had Catholic congregations that crossed class and ethnic boundaries; in Central, for example, Tom Foy’s family attended the same services at Santa Clara Church that many workers’ families did. We cannot make too much of a distinction between Holy Family and the other Catholic parishes, however, because Father John Linnane, who served Silver City’s San Vicente Church, also helped the strikers and, the following year, the filmmakers. In fact, the Catholic churches in the region, in addition to St. Mary’s Academy, were probably the only churches integrated to that degree; all other churches seem to have had either Anglo, African American, or Spanish-speaking congregants of similar class backgrounds.

If Empire Zinc strikers and their supporters believed that the Empire Zinc Company was responsible for escalating the conflict, other townspeople laid the blame at the feet of the strikers. Illustrative of the complicated fissures the strike opened in Grant County is the case of C. B. Ogás, a Mexican American insurance agent in Bayard. Ogás felt that the strike got out of hand, with both sides to blame. For years he had sold policies to the poorer people of Grant County and witnessed firsthand the difficult and dispiriting conditions in which many lived.101 Long a friend of Tom Foy, Ogás had managed the campaign that got Foy elected as district attorney in 1948. By 1951 he was managing the Copper Real Estate Company, which Foy owned.

Ogás sympathized with the Empire Zinc strikers, but on terms different from those prescribed by the union leadership. He adopted what he considered to be an even-handed attitude toward the strike, and he deplored the effect of outsiders on the community. To his way of thinking, the company should not have tried to import scabs, nor should the union have brought in “outside agitators” like Clinton Jencks. The escalating violence that galvanized community support struck Ogás as evidence that the situation had gotten out of control. “One woman,” he recalled, “even put her newborn child in front of a truck. It got that bad.”102 The strikers seemed to be provoking violence almost as much as suffering from it, or possibly even using it for their own propaganda purposes. The horror of the brutality could make any such efforts appear at best cavalier, at worst immoral.

Ogás’s perspective shows how the strike spread beyond the confines of the Empire Zinc mine and into the lives of people only indirectly connected to the union or to the individual strikers. As an agent of Tom Foy’s business, Ogás felt he could not sign the Copper Real Estate Company’s name to a petition supporting the strike circulated by Local 890 among Bayard businesses. He saw his refusal as simple business practice: the name was not his to sign. (At the same time, however, he did sign a petition that claimed “neutrality” regarding the strike and repudiated the union’s attempt to solicit help from businesspeople through a petition.) The union saw this as a fundamental betrayal of the community. For the petition was not simply the union’s means of soliciting support: it was a means of marking out the union’s supporters from its detractors along a clear axis. There could be no middle way, and Ogás’s attempt to forge one cost him dearly. He was seen not just as a union opponent but as a traitor to his fellow Mexican Americans. His own family relations were ruptured as his cousin denounced him for not supporting the strike. The union published the list of those businesses that did not sign its petition and then boycotted them. In Ogás’s case, the boycott effectively drove him out of business by 1955 and out of town shortly thereafter; only in the 1990s did he and his wife return to Silver City from their thirty-year exile in Santa Fe.

This was a divided community, and in some respects Ogás was correct in attributing blame for the widening division to both sides. This does not mean that we can satisfy ourselves with a facile “there are two sides to every story” explanation. Instead, it is worth examining the mechanisms by which Local 890 members both built and inhibited “community.” The strike laid bare some of the class and ethnic divisions that had long existed. The company’s intransigence consistently ratcheted up the stakes, and the strikers—witnessing the apparent collusion of local officials with Empire Zinc—identified their strength in a simple unity to match that of the powerful. Local 890 reached out to Mexican Americans throughout the district and, significantly, attracted many non-Mexican Americans to its cause. In staffing the pickets, squaring off against the judicial system, and trying to get the word out to the public, the union made people into genuine “brothers and sisters.” But in some ways the strength of their bond lay in the sharply etched divisions between this group and the rest of the community. The perceived clarity of the political situation—the company against the “community”—actually obscured circumstances that might have made an individual refrain from supporting the strike in the ways staked out by the union. People like C. B. Ogás fell through the cracks of the community that 890 built.

Some initially sympathetic businesses, like Ogás’s real estate firm, also had financial reasons for ceasing to support the strike. Silver City’s only radio station, KSIL, had broadcast Local 890’s weekly “Reporte a la Gente” (“Report to the People”) since May 1949, prefaced by an editorial disclaimer. After the violent episode of August 23 and the subsequent districtwide strike, under pressure from the station’s advertisers, station manager James Duncan asked that the union submit the “Reporte” ahead of time for censorship. But even this did not satisfy the station’s advertisers, who forced KSIL owner Carl Dunbar to cancel the show early in September. The radio program, he explained, was “contrary to the public interest.”103

Southwestern Foods had supported Local 890 during previous strikes. Almost all of the strike relief receipts for the Asarco and Empire Zinc strikes came from this Bayard grocery store, and on occasion it wiped the account books clean as a donation to the union. Its generosity notwithstanding, the store’s management also benefited from Local 890’s coffers; according to Virginia Jencks, the union had spent “over $17,000” at Southwestern Foods over the previous four years. By September, though, the store began to curtail credit to striking families. A picket of women, children, and men demonstrated against this new policy that month. During the demonstration, perhaps angry that the strike seemed to be spreading beyond Hanover—or perhaps just angry—a crowd of “businessmen and cowboys” gathered around the picketers and pushed them onto the street, where cars were positioned to run them down. The crowd called the picketers “dirty Communists” and told them to “get the hell out of there.” Southwestern’s butcher, David Gray, came out of the store and joined in the fight. He tried to grab a sign from the hands of a little boy, and Virginia Jencks told him “to pick on someone his own size.” After that he attacked her—and her daughter—by pulling her hair and slapping her.104 Jencks was also assaulted by local residents L. H. and Vivian Patton. She told Justice of the Peace Andrew Haugland that L. H. Patton “smashed me in the eye with his fist [and] was insolent.”105 Only when the picketers dragged a policeman from across the street, where he had been watching the fight, did the brawl end.106 Gray and the Pattons each pleaded not guilty of assault, and Gray charged Jencks with “unlawfully touching [him] in a rude and insolent manner.”107 Gray admitted that he “had grasped Mrs. Jencks and her 14-year-old daughter, Linda, by the hair in the fracas.” But he claimed he did so only after Virginia Jencks attacked him.108 On September 27, Jencks was found guilty while her attackers were acquitted of assault charges.109

Families of strikebreakers were particularly angry at the women’s picket because they bore the brunt of union hostility. Mary Hartless, the mother of Denzil and Carl, was furious at the Empire Zinc strikers for mistreating both the strikebreaking workers and the community more broadly, and she was convinced that the Jenckses were the cause of all the trouble. “For ten months it’s been a fight, scratch and growl,” she declared. “The people of Local 890 have insulted and spit at the people of the community. It’s a shame we have to put up with this. The people acted decent until Clinton Jencks and his wife came here, started their rotten talk, and stirring the people up.”110 She and her husband, Odell, had come to Grant County in the 1930s, each having grown up on farms in Oklahoma, Texas, and eastern New Mexico, but unable to make a living on the farm in the Depression. Memories of the Depression made them glad for employment in Grant County, even though Odell’s work made the family move frequently from town to town.111 For this reason Mary especially resented the Empire Zinc strikers, who aimed to keep her sons and husband from bringing home a paycheck. The strikers’ refusal to work did not seem to her a sacrifice for a principle; instead, it was proof of the strikers’ laziness. “Just as long as there are anyone giving Local 890 handouts they are not going to work. Why should they? As long as their families are taken care of it’s much better they don’t have to work.”112 The Hartlesses may not have known what a typical company house for Mexicans looked like (their own company house had three bedrooms, electricity, running water, and a regular bathroom), so the workers’ complaints may have seemed precisely that: complaining.113

As frustrated as Mary Hartless was, the strike was probably more difficult for her daughter Betty Jo, a seventh-grader at Hanover School. She had been a quiet student, and during the strike she tried to keep to herself. But the polarization engendered by the strike extended even to the schools, and fights, even among girls, broke out in the schoolyard. Strikers sometimes blocked the road leading to the Hartlesses’ house, too. Conflict with picketers became so intense that the family moved to Bayard, where Betty Jo finished out the school year.114

Families only indirectly connected to the strike felt the pressure to choose sides, too. Juanita Escobedo’s parents, for example, covered the back of their pickup with a tarp to protect the children from rocks as they drove near the picket line to visit a brother, Pete Quintana, who lived in Fierro and continued working at Empire Zinc. “Of course, we knew why they were striking,” she recalls. “But there was no room” to explain to angry picketers why the family was going through the picket line.115 Cecilia Pino was a child whose grandfather crossed the picket lines, and she recalled considerable abuse by strikers—enough that fifty years later she was still distressed by it.116

Anger at the picketers helped spark the August 23 incident, in which picketers were injured. Thirty strike opponents met with Goforth on August 22. “We are tired of having to face rock throwing and having pepper thrown in our faces as we go to and from our homes,” they explained.117 Catalyzing the next day’s violence was “an alleged assault upon a car driven by Roy Sanders, bookkeeper at the company’s office for a number of years.”118 Many of those who went to Goforth stressed that they were simply Hanover residents, although a closer look reveals that many were strikebreakers, or relatives of strikebreakers. And some of the strike opponents certainly behaved the same way as the strikebreakers. Oleta and Homer McNutt, for example, threatened Vicente Becerra with a gun.119

Violence on the part of union opponents was seldom punished. Sheriff Goforth required a $250 peace bond from both Oleta and Homer McNutt (but required a $500 bond from Becerra), and the district attorney charged Jesús Avalos with discharging a weapon in a settlement, but law enforcement generally left the strike opponents alone. Sheriff Goforth was a little uneasy, though, when a vigilante group was formed in September. In response, Goforth organized a posse consisting of five men, all ranchers and former law enforcement officers, but made a point to exclude “hotheads and . . . misfits.”120 Goforth chaired a meeting on September 24, 1951, organized by the “law and order” group who had approached him in August. About 150 people attended, among them Local 890 official Joe T. Morales. Goforth agreed to give him the floor, and Morales stated that he too disliked having the women and children on the picket line. He also declared that the communist issue was irrelevant. The audience applauded him when he finished.121

Some Grant County residents saw in the opposition to the Empire Zinc strike the chance to settle old scores, some of which dated from the 1947 amalgamation of Locals 530, 69, 63, and 604 into Local 890. Robert Day, formerly an Asarco worker and secretary-treasurer of Local 530, was elected a justice of the peace in Bayard in 1950.122 Charles J. Smith had served as Local 530’s first president. Both men lost their union offices to Mexican Americans at the time of amalgamation into Local 890, and Smith went on to run his own garage and gas station. Day, Smith, and Earl Lett, a druggist who came to Grant County in 1949 from Deming, were cornerstones of a “law and order committee” that solicited Governor Mechem to impose martial law on Grant County after the August 23 incidents. Earl Lett singled out Clinton Jencks, assaulting him on a Bayard street on October 1. He then dropped by Justice of the Peace Day’s house for punishment—a fine of one dollar.123

Charles Smith insisted that he was not antiunion: he was proud of his work organizing workers into Local 530, and he was only angry that the wrong leaders had gotten control of the union. “What,” he asked, “can American citizens do to protect themselves from a group of irresponsible leaders who are following the communistic line and using good American citizens, and an American institution, ‘Unionism[,]’ as a front, to get by with what has been going on here lately?”124 To show his support for the right kind of unionism, Smith and his committee invited the United Steelworkers to raid Local 890 in September and October; the Steel-workers organized an opposing union, aimed at all of Local 890’s jurisdiction, under the name Grant County Organization for the Defeat of Communism.125

In this the Steelworkers were using the same tactic they had been using since the late 1940s: sending in organizers to persuade workers—sometimes through direct violence and intimidation, often through race-baiting, and always through red-baiting—to abandon Mine-Mill. Arturo Flores, for example, had recently taken a job as international representative in order to fight just such raids in Arizona and El Paso. Raiding, or trying to lure union members from one union into another and ultimately to win jurisdiction over a set of workers, was nothing new in the 1940s; Communist unions, in fact, had routinely raided AFL unions during the CP’s “dual-union” period of the 1920s and early 1930s until the Popular Front strategy directed them to work within existing unions. After World War II, raiding became a weapon used against left-wing unions by rivals motivated by anticommunism, opportunism, or a combination of the two. These raids were extremely disruptive, whether the existing union was displaced or survived. In its 1945 raid on the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers in California, for example, the Teamsters violently attacked FTA workers and organizers and ultimately defeated what had been a progressive force for Chicana labor rights.126 Steelworker raids on Mine-Mill locals often divided communities and families regardless of the jurisdictional outcome. And in Anaconda, Montana, gender played an important role in crafting both Steelworker and Mine-Mill propaganda during these campaigns; Mine-Mill’s stifling of the women’s auxiliary in the 1940s compromised the community unionism that was needed to resist Steelworker raids in the 1950s.127

Still, throughout the 1950s, the Steelworkers’ political attacks failed either to dislodge Mine-Mill locals in the Southwest, where Mexican American loyalty was important to Mine-Mill’s survival, or to eradicate it elsewhere in the United States. Like most southwestern Mine-Mill members, Local 890’s members—Anglo and Mexican alike—were not swayed by the Steelworkers’ appeal.128 They “spoke bitterly about some of the businessmen who . . . asked CIO Steel to the district [and] recalled the weak local they had until Mine-Mill organized the area.”129 Asarco worker Cornelius “Bud” DeBraal explained, “We never knew where our dues went, or what good we got from them. The money just disappeared when those birds, who used to be our officers, got it. And today they are the same businessmen telling us we should have another union.”130 The Grant County Organization for the Defeat of Communism elevated the anti-communist tenor of the strike’s opposition (which had been remarkably muted until the summer of 1951), but it did not thereby weaken either Local 890 or the Empire Zinc strike.

Both instances of physical assault away from the Hanover picket lines were directed against the Jenckses. There are several possible explanations for their being targeted. The Jenckses did come from “outside”—Colorado—and the press and local antagonists consistently labeled them “outside agitators.” Related to this was the fact that they were Anglos who forthrightly threw in their lot with the district’s Mexican Americans. In the eyes of union opponents, local Mexican Americans’ agitation for civil rights was bad enough—and in fact likely to have arisen only when outsiders stirred them up—but Anglos struggling alongside Mexican Americans was unthinkable. Virginia Chacón believes that Anglos were furious that the Jenckses would ally themselves with Mexican Americans.131 The Jenckses exposed the social system’s inequities that, for the privileged, had remained “natural” and therefore comfortably unexamined. It was this publicity—and not the material or social inequalities between Anglos and Mexican Americans—that, in the minds of union opponents, created a race problem where none had previously existed. As the Silver City Daily Press commented in July 1951, the “worst feature of the situation now is the continued effort to stir up animosity between anglos and the people who—judging by letters to the Daily Press—prefer to call themselves Mexican-Americans. . . . The two races are here and doing pretty well in this prosperous mineral district. They get along alright, too, except when politicians and walking delegates get ’em stirred up.”132

Conflict with strikebreakers and their families caused some Empire Zinc strikers to sharpen their understandings of ethnicity. Teenager Lupe Elizado, for instance, wrote an impassioned letter that raised the danger of Mexican Americans being treated as badly as African Americans were. “We are not going to give ourselves to slavery and be treated as colored people,” she announced. “The treatment that is given to colored people is nothing to be proud of. They are human beings just like we are. Their color makes no difference as long as they’re decent people.”133 Elizado challenged Mrs. Tex Williams, wife of one of the deputies, for calling the kids on the picket line “brats” in a letter to the Silver City Daily Press.134 Elizado took a stand on the proper names for Mexican Americans: “You know why we’re living here, Mrs. Williams? Because we have a right to do so, even more than you Anglo-Americans because this land once belonged to Mexico. We’re not Spanish or Spanish-Americans as you call us. We are Mexican-Americans, our parents came from Mexico, not from Spain.”135 Not only did Elizado lay claim to her Mexican ancestry, but she also rejected the label “Spanish-American” as an Anglo term. In fact, it was common for Anglos and Mexican Americans alike to refer to the “acceptable” Mexican Americans as Spanish. By calling this usage an Anglo practice, Elizado was implicitly condemning those Mexican Americans who also used the term for rejecting their Mexicanness.136

As women picketers refined their understanding of the local political economy, they transferred this newfound confidence to their dealings with the international union. Relations between Local 890 and the international took a turn for the worse in September 1951. Shortly before the Mine-Mill convention in Nogales, Arizona, the executive board hastily dismissed international representative Bob Hollowwa. Hollowwa’s dismissal resulted from the conflicts between Local 890 and area businesses, specifically the Law and Order Committee. Hollowwa was a rather confrontational leader, and the international leadership believed that he pushed otherwise neutral people into the opposite camp.137 Hollowwa’s correspondence with Cipriano Montoya the following winter and spring hinted that the real issue was that “top brass” like Orville Larson and Maurice Travis objected to his militancy.138 Precipitating his dismissal was publicity generated by the Steelworkers in their attempt to discredit Mine-Mill. Hollowwa, they revealed, had served four years in San Quentin on a 1934 kidnapping conviction and, along with his wife, reputedly attended CP meetings.139

If Hollowwa was unpopular with moderates and a magnet for anti-communist agitation, he was very popular with the women picketers. He had pushed for women to take over the picket line; he had accompanied them when they tried to get the Silver City Daily Press to publish union messages about the strike violence; and he showed tremendous confidence in the women’s abilities. At a September 19 meeting, he was quick to point out that the women were crucial to the strike but he was not.140

Local 890 was confused and indignant over Hollowwa’s dismissal in the middle of the strike. At the September 19 meeting, men and women commented that Hollowwa’s past problems should have been dealt with long ago, and not in the middle of the strike. Braulia Velásquez denounced the “propaganda” as “part of the move to disrupt the union.” Her statements stirred the people to extend the meeting by fifteen minutes, during which time the local voted to send another telegram to the international. Vicente Becerra suggested that the local “chip in to pay for Brother Hollowwa if necessary,” and Joe Ramírez praised Hollowwa for his hard work on the strike. Thirty-one women sent a very strong message to Mine-Mill president John Clark on September 26, demanding that the international meet with the local to explain the dismissal and, ultimately, reinstate him. “Should this not be granted,” the telegram concluded, “we shall take action ourselves.”141

Clearly these were not deferential union members. The women and men who gathered in the union hall that September night proved quite adept at pushing to the political heart of the matter, even when such effort meant challenging their national leaders. Local 890 members suspected that behind the dismissal lay personal differences that should not influence the union’s strike strategy. In the same way that a left-wing union like Mine-Mill might question the motives or timing of government or corporate actions, so too did the local members penetrate beyond the surface of claims of the national leadership to question that leadership’s motives and timing.142

Experience on the picket line, in the courtroom, and in jail showed women their collective strength in the face of hostile local authority, often without any help from men. It strengthened their solidarity and contributed to new understandings of the local political economy, shaping their ideas, as historian Dana Frank has put it, of “who they believed was in power; what they thought should be done to alleviate their stress, and, most importantly, how they believed they as women could affect the economic system in which they were enmeshed.”143 Lola Martínez, for example, complained that “justice was not for the working people” in Grant County. Her comment came after Assistant District Attorney Vincent Vesely backed strikebreaker Jesús Avalos in a dispute over armed scabs trying to cross the picket line. Avalos, Vesely declared, did not mean to shoot at women picketing the mine. On the picket line, women witnessed the supposedly neutral sheriff actively transporting strikebreakers across the line; if the women interfered with a scab-bearing car, as did Henrietta Williams, Mary Pérez, Eva Becerra, and Elvira Molano, they were arrested and held on a peace bond.

The strike persisted into a second year. Aid from other unions throughout the country kept food baskets reaching strikers’ homes, and the legal snares that the union dealt with each day only drove home the lessons in political economy that its members had learned during the summer. After another series of violent incidents in early December, the company finally agreed to negotiate early in January 1952. The settlement hammered out between the parties provided wage increases totaling 39½ cents, vacation benefits, collar-to-collar pay, and a new rate classification. Striking Empire Zinc workers ratified the contract unanimously at the amalgamated union meeting of January 24. Thus, the fifteen-month Empire Zinc strike ended with substantial, though not overwhelming, contract gains and, as Clinton Jencks stressed, “substantial recognition” won by the women of the district. It was, strike chairman Ernesto Velásquez said, “the entire membership [that] made it possible for us to bring the fight to the end.”144

The women strikers had their own understanding of where the thanks lay. Back in September, spirits had been flagging. People were tired. The women met on September 11, 1951, to discuss the “picket line problems,” and they “decided to form competing teams for picket line duty, with awards or similar recognition going to top teams.” Schoolchildren would be allowed to volunteer on Saturdays “to relieve those with household duties.”145 The women picketers thus relied on the strength of their organization to pull themselves together to address the problem and think up a solution. But they sought spiritual help in other quarters as well. A group of about twenty-five women (possibly the same as those who in October asked Father Smerke for a high mass) pledged to make a pilgrimage to the Church of San Lorenzo, some fifteen miles away in the Mimbres Valley, if God willed that the strike should succeed. When the strikers won in January, the women fulfilled their pledge. From Bayard to San Lorenzo they walked, their physical effort expressing their gratitude.146

Actually, the strike did not end there. The legal cases that Empire Zinc refused to drop against 890 officials and members constituted more than “aftermath”: they formed a central part of the story and also one of the many links to the Hollywood filmmakers who would approach Mine-Mill and Local 890 to produce a feature film about the strike. District judge A. W. Marshall fined the union and twenty members a total of $37,750 on March 10; the union posted a $76,000 bond to keep the twenty out of jail while they appealed the verdict.147 On March 18, twelve Mine-Mill defendants appeared in district court. The union paid $600 in fines and charges without contest because it still faced around seventy-five additional cases. “We had to clear away the ‘underbrush,’”—a union spokesperson explained, “to be able to concentrate on more serious charges.”148 In September, serious charges resulted in ninety-day jail sentences for Ernesto Velásquez, Cipriano Montoya, Clinton Jencks, Fred Barreras, Vicente Becerra, and Pablo Montoya. Their attorney, former governor A. T. Hanett, could not persuade Judge Marshall that “it was unfair that the union had been hauled before the court when the National Labor Relations Board had ruled against New Jersey Zinc.”149 As a special punishment, the jailer isolated Jencks from the others. Union members did enjoy one victory that fall: Although Tom Foy held onto his office, voters defeated Sheriff Goforth in his reelection bid. And the following spring, Sheriff’s deputies Marvin Mosely and G. W. Clanton tried to parlay their Empire Zinc service into elected office. They were both defeated soundly in the Hanover constable race by Cecilio Torres, a union man.150