6 Household Relations

BACK AT HOME

Agustín Chávez was not happy. As a striker at Empire Zinc, he worried about taking care of his family on limited strike benefits. He and his wife, Aurora, had three children, the eldest only nine years old, and Aurora was pregnant with their fourth. But now he had something bigger to worry about: his wife on the picket line. He confronted her after the union meeting on June 12, 1951, despite—or perhaps because of—her having been one of the women to propose the women’s picket. He “didn’t like it at all. He knew how it was gonna be and he didn’t like it,” Aurora recalled. Agustín Chávez feared the violence that his wife would face, and he also feared—correctly—that he would have to take care of the children.1

Aurora Chávez, though, stood her ground against her husband, because over the past nine months she had become very personally invested in the strike. At first she had taken “very little interest in the whole affair,” but as she worked with the ladies’ auxiliary she came to “understand that this is not simply a fight for higher wages.” “That is but a minor part of our demands to help improve our standard of living,” she explained. “What we are mainly concerned with is the health and safety of our husbands and brothers while on the job.”2 Health and safety, not just wages, would improve the standard of living, and at age twenty-seven she knew well what the standard of living for mining families was—and what it should rightly be. Her parents both arrived in Grant County from Mexico as children during the Mexican Revolution.3 Her paternal grandfather, a miner, died shortly after bringing his family from Guanajuato. Her grandmother opened a boardinghouse, and her father gave up school and started working for Chino at the age of thirteen. By the time of Aurora’s birth in 1924, he worked in Chino’s powder department, blasting the sides of the open pit copper mine with explosives so that railroad cars could haul the ore away for processing. He and his young family lived in Santa Rita.

The oldest of ten children, Aurora had begun helping her mother around the age of six or seven. Her mother worked at a bakery during the Depression: with children all under the age of ten, the family relied on her outside employment to make ends meet rather than sending one of the children into the labor market. Even with substantial household responsibilities, Aurora managed to continue school until she was eighteen years old. That was when she married Agustín, a twenty-year-old Empire Zinc miner whom she had met at a dance. After their marriage, the Chávezes set up house in Hanover, renting from Empire Zinc a three-room house that had few modern conveniences. There was a water tap outside but no bathroom indoors. Aurora used a woodstove for cooking and a coal one for heating, and she had to chop the wood and carry the coal to keep both stoves stoked. She did this while bearing and raising three children within nine years.

Aurora ultimately prevailed against her husband regarding the women’s picket, but not because her husband agreed to look after the children. Instead, Aurora’s father sent her teenaged sister Rachel to help out while Aurora walked on the women’s picket line. Thus the Chávezes resolved their conflict by preserving Agustín’s prerogatives in one area—not performing child care—but challenging them in another: Aurora would face the violence on the picket lines, and Agustín would stand to one side. He still was not happy about it, but it was the agreement they reached. Importantly, the couple resolved their conflict by turning to the wider family, one in which male authority also carried great weight. Aurora’s father, Domitilio Juárez, had the authority to send one of his daughters to Hanover and to persuade Agustín that this was a reasonable solution. Domitilio regretted his decision a month later, when sheriff’s deputy Marvin Mosely struck his daughter Rachel Juárez with a car.4

The picket brought women from all corners of the mining district into one lively place. But the picket’s effects extended outward, too, into each woman’s home. With women walking the pickets for hours on end—often stretched even longer by women’s reluctance to leave at the end of their shift—men found that their houses were not nearly as well kept nor their children as well tended as they expected. Men confronted their wives for abandoning these responsibilities, which posed an implicit challenge to men’s authority in the home. As Local 890 officer Angel Bustos later remarked, “We had a lot of trouble with some of our members that the women should not take any positions or defend any picket lines in any labor movement.”5 Children picked up on these conflicts and compared notes on them, trying to understand the changes they were witnessing but not allowed to discuss with their parents. “You should have heard the fights last night,” one youngster would tell another. “Yeah,” the other would reply. “My dad’s sleeping in the living room.”6 The story of the women’s picket, then, became a story of women’s rebellion, not just against the Empire Zinc Company but also against their own husbands. Women did not begin their strike activities with gender relations in mind; they aimed only to defend the union community. But the resistance women encountered from their husbands made them realize that there was perhaps more at stake than first met the eye. It made them argue explicitly for women’s rights to work for the union movement on their own terms and, if necessary, to reorganize their households.

Women and men argued at home, and some women even carried this discussion right back into the union hall. Just two days after the momentous vote, Chana Montoya insisted upon “more help from men on the jobs off the line. More help on the job we cannot do at home while we are doing this job.”7 Montoya spoke with some authority. She was married to Local 890 president Cipriano Montoya, so her words probably carried weight in a union meeting. But her candor is all the more remarkable given the sad fact that her husband regularly abused her. Many people knew this; no one discussed it. She was probably speaking from her own experience at home, and for her even to hint at domestic conflict is astonishing. Clearly she felt that the union community was an authority to which she could appeal and the union hall a safe place in which to voice women’s needs. Perhaps her call was made easier by Cipriano’s absence from that particular meeting.

Cipriano Montoya was, however, present at—indeed he presided over—another important union meeting, where he hinted at women’s proper duties. In October 1951, Local 890 celebrated the first anniversary of the Empire Zinc strike. While strike chairman Ernesto Velásquez praised the women as “veterans,” a term fully laden with masculine honor, Cipriano Montoya congratulated first the entire membership and then the women, for “knowing that they have work to do at home.”8 At this meeting, meant to reflect upon the difficulties they had faced and the victories they had won, Montoya chose to remind women of their household duties and to limit his praise to their meeting those obligations. Chana did not speak at this meeting.

Conflict strained the relationships between husbands and wives, and everyone understood that it jeopardized the unity needed against a mining company. But women and men disagreed on the source of the conflict. Women understood their picket duty as a temporary assumption of male duties, similar to the “deputy husband” role that historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich has described for colonial American women: under unusual circumstances—most notably widowhood or the temporary absence of a husband—women took on men’s responsibilities without posing a serious threat to the normal order of things.9 Many men, on the contrary, believed that women did not belong on the picket lines for two simple reasons. First, exposing their wives to violence made the men look weak, which challenged husbands’ sense of manhood. Second, this threat to their manhood was made even more serious when women expected men to assume women’s duties at home. Men did not see this as an equal exchange. While women might assume the role of deputy husband, it was quite another thing for men to take on women’s work. In other words, men and women generally agreed on a division of labor and of responsibilities, but that division did not entail a symmetry of responsibilities. The sexual division of labor was by definition asymmetrical, and male authority depended in part on this asymmetry. Any disruption of male authority at home risked undermining the strength and stability of the household, the foundation of the union “family’s” strength.

A household has a dual nature. It may be considered a single unit, its members sharing the goal of bringing together cash and noncash resources in order to feed, clothe, and house themselves as well as to produce and raise children. But the household is also a composite of individuals—men and women, adults and children—exercising different kinds of power and having distinct material interests.10 Its unity is a fiction, not in the sense of being false or untrue, but in the sense of being created by the people within the household and by society more broadly. The fiction needs to be maintained, and in systems of male dominance its maintenance demands that male authority be able to override female authority at critical moments, whether by cultural prerogative or by physical force. While a family might pursue a shared goal—sending some children into the workforce, for instance, so that the mother might remain at home—the compromises made over which goals to pursue and how to pursue them are products of unequal power relations between men and women in the household.11 The apparent unity of the family results from men’s and, to some degree, parents’ ability to impose that unity upon the family’s actions. Thus, to understand how families worked together to make the women’s picket succeed, and how the picket, in turn, affected families, we must uncover the power relations that lay beneath the appearance of unity behind a common goal.

Divisions of labor are not only gendered; as we have seen, a central organizing principle of Grant County’s economy was an ethnic division of labor. These two divisions of labor share certain features. In both situations, people ascribe different values to different types of work—some work is considered dirty and debasing, other work ennobling—and assign that work to people based on ethnicity or sex. This ascription is a social process, not a natural one, but it is made to seem natural and unchangeable. Ultimately it serves to mark and reinforce power differences between groups or individuals. Still, there are some important differences between ethnic and sexual divisions of labor, and these differences bear on the varied ways that working-class people built solidarity in Grant County’s mining district. The key difference lies in the family: the sexual division of labor resides in the family (as well as in the larger labor market); the ethnic division of labor does not. Both divisions entail a certain symbiosis, but of very different sorts. The sexual division of labor in the household is maintained by the emotional and practical ties that bind a family together. There are no such emotional ties binding Mexican American workers to Anglo workers. The definition of “Mexican” work, of course, depended on a counterdefinition of “Anglo” work. But the ethnic division of labor, unlike the sexual division, does not entail interdependence so much as complementarity. And whereas the sexual division of labor allows families to pursue shared goals, the goals advanced by the ethnic division of labor are not workers’ goals but rather those of their employers. As much as Anglo managers and workers might speak of the ethnic division of labor as natural, efficient, and contributing to the benefit of all, the people on the bottom—the Mexicans—are more likely to see those divisions as artificial, unjust, and harmful. By contrast, family members on both sides of the sexual division of labor constantly experience the ties that bind them to one another, and it is hard to alter some of those ties without sundering them altogether. This does not mean that the sexual division of labor is natural, or necessarily desirable, but that family members of both sexes receive some benefits from it.

In this chapter I analyze these household relations, considering both the ways that people made their families and the ideology that supported particular arrangements, in order to see what women were rebelling against and how they experienced and understood the conflicts that shook up their families. The breadwinner ideal, discussed in Chapter 4, was manifest in women’s desire to marry, in the economic structure that limited women’s options outside of marriage, in women’s daily household work and management, and in husbands’ attitudes—accompanied by the power to enforce their beliefs.

CHOOSING MARRIAGE

Most women in Grant County got married, usually quite willingly. Dolores Villines, for example, had grown up very shy, very reserved, and forbidden to date boys. Frank Jiménez was her first and only boyfriend, and she was struck, as she called it, “love blind.” “I just loved that man very much. For me he was everything.” She married him when she was only seventeen years old, and she had both of her sons by the time she was nineteen.12 For girls tired of their parents’ restrictions, marriage promised excitement and the release from childhood. Elena and Daría Escobar grew up under close supervision by their mother, who raised them and their eight siblings alone by taking in boarders. Neither girl was allowed to date boys, or even to walk through the neighborhood unescorted; Daría used the time when her mother was at church to run quickly from one neighbor’s house to the next, desperate for some social contact.13 Marriage provided an escape from this cloistered upbringing. To some women I spoke with, marriage was something they had wanted very much—at least at the time they decided to get married; perhaps there was some wistfulness at the eagerness with which they had gotten married, or some regret at the mistakes of the young. But in all cases, they implied that marriage was something definitive, perhaps inevitable.

If marriage played a part in most women’s graduation to adulthood, it was also a choice heavily influenced by the job market and cultural expectations. There were material reasons why staying single was a difficult path to follow: it was hard for a woman to support herself or her family without a male wage-earner. “A woman could work in the stores,” Josie Flores remembered. “Or in the restaurants,” added her husband Arturo. “Just hardly anything else.”14 As is discussed below, job opportunities for women, regardless of their ethnicity, expanded and contracted within the economic sectors of clerical, sales, service, and, to a lesser extent, professional work. Ethnicity further determined women’s opportunities. Anglo women were more likely to work as professionals and clerical workers than were Mexican American women.15

Marriage often ruled out a paying job, though this was not the case with two of the Empire Zinc strikers and Salt of the Earth actors: both Henrietta Williams and Clorinda Alderette worked outside the home while married. But many women I spoke with laughed off the suggestion that they could have done both. When asked what happened to the jobs they had held as young women, Dora Madero and Alice Sandoval both gave the same explanation, “I got married.” Sandoval said that her husband did not want her to work—“I guess I wanted to get married more than I wanted to work”—and Madero hinted as much.16 Virginia Chacón worked for five years as a nurse’s aide for a doctor she respected, but she turned down his offer to transfer to Phoenix and go to school at his expense. Recounting the story fifty years later, Chacón first laughed when she explained her decision: “Oh, I got married!” She paused, then confessed regretting her choice “in a sense, because [Dr. Meyers and his wife] were such good people to work with. They were so good to me.”17

DIVISIONS OF LABOR

When women boldly suggested that they take over the Empire Zinc picket line in June 1951, they were acting on the basis of class and ethnic consciousness that reflected both their own work histories and their recent union activism. When men agreed to “let” women assume picket duty, their actions, too, were based on class and ethnic consciousness. But as discussed in Chapter 4, the arguments unleashed during that contentious union meeting suggest that there was more to this class and ethnic consciousness than meets the eye. Since it provided the basis for different stances, its meanings seem to have varied for men and women. Experiences in jobs and families provided the basis for both men’s and women’s consciousness, but the work they performed, the responsibilities they met, and the authority they held in the family were very different.

Women’s virtual absence from mining—the region’s dominant industry—was a critical feature of the economic structure that limited their opportunities and made marriage a necessity for many, if not most, women. Put simply, women enjoyed few opportunities for paid work. Western mining camps of the nineteenth century sprang up wherever ore was discovered, not according to a well-planned model of urban expansion, and although some operations eventually became industrial processing centers themselves, they were typically located far from urban industrial centers that might have offered a range of jobs to women. The Silver City area presented a greater range of occupations than some mining regions because Silver City was the county seat and also home to the state teachers’ college. But it was by no means a “city” with a diverse industrial base, and most mining families lived in the smaller towns ten to fifteen miles from Silver City. Some women commuted to Silver City, but limited transportation kept many women isolated in their homes and small towns.18

Only a minority of women in Grant County belonged to the paid labor force, although the number and percentage grew from 1940 to 1950.19 In 1940, 1,126 (17 percent) women aged fourteen and older considered themselves part of the labor force; this number rose to 1,585 (22 percent) in 1950. Most employed women worked in sales, clerical, and service jobs, their numbers more than doubling between 1940 and 1950 from 169 women (15 percent of the female labor force) to 453 (28 percent of the female labor force).20 Only 41 women worked as factory operatives in 1940, and, while that number almost doubled to 74 in 1950, it still represented only 1 percent of adult women and just under 5 percent of the adult female labor force.21 Over the same period, the professional ranks remained relatively stable. The number of professional women increased from 236 to 307, but the proportion of women professionals in the adult female labor force actually dropped from 21 percent in 1940 to 19 percent in 1950. Teaching, nursing, and administrative work were the most common professions for women.

Of course, these jobs were not distributed equally: ethnicity determined women’s jobs as much as it did men’s. Anecdotal evidence—job notices and descriptions of individuals in the local newspapers—as well as the 1930 census data suggest this job segregation.22 Professions were almost exclusively Anglo through the 1950s, as were most clerical positions, but both Anglos and Mexicans held sales jobs.

Exceptional circumstances brought a few dozen Grant County women into local mines and mills during World War II. Chino hired several dozen women to fill the male labor shortage, although all 63 underground workers in 1944 were still men. That year, 29 women joined the track gangs that laid, repaired, and moved the railroad tracks on which cars hauled ore from the Chino open pit mine in Santa Rita.23 Guadalupe Fletcher, divorced and responsible for her daughter’s care, quit domestic service to work on the track gang.24 Younger women worked there, too, among them Dora Madero, a Silver City teenager. Walking to school one morning, she and a friend happened upon some girls boarding a Santa Rita–bound bus in Silver City. “Let’s get on the bus,” Madero told her friend, “and see what happens.” “[We] rode all the way to Santa Rita, and believe it or not . . . were hired right way,” Madero explained. “They didn’t even ask your age, or nothing. Not even if you had social security or anything like that. They just hired you. So they gave us a little money, and they had a company store and we went up there and we got our safety shoes, and a lunch box, and a safety hat.” They stayed until the bus left for Silver City at 4 P.M. Madero normally came home from school at 3:30, however, and her suspicious mother met her at the door. She looked at her daughter’s new safety shoes. “Where were you all this time?” she wanted to know. “I’ve been worrying about you.” Madero was supposed to graduate from high school but insisted on working at Santa Rita instead; she would finish school after the war, she told her mother. Only because the family needed money—Madero’s father had run off (“like most men do,” Madero commented) and Dora’s mother was raising her daughters alone—did her mother finally come to accept her daughter’s job and overlook her daughter’s willfulness.25

Madero enjoyed the work, the camaraderie, and the money (even though she had to turn it over to her mother). Her foreman was less thrilled to have a group of young women working under him. “You women,” he complained. “First snowfall we get, you’re going home. You’re not staying here and you’re going to mess up everything. We’re not going to have nothing to work with, nobody.” But all of them stayed on the track gang. And apparently her foreman liked her enough to let her drive other girls to their work sites in a little car and then to let her work as “water girl,” bringing water to all the workers in her car.26

A handful of women also worked as laborers in other Santa Rita departments. One woman worked as an electrical laborer, another in the machine shop, four in the carpentry department, and two as drill laborers in the powder department.27 None of these occupations was considered skilled labor, which suggests that the wartime labor shortage drew women selectively into the workforce. Any consideration of the work appropriate to women apparently did not turn on the question of physical danger: most women’s jobs were demanding and difficult. Chino hired women in large blocks separately from the men hired in the same departments; moreover, women were singled out and identified on the seniority lists as “F” for “female.” This suggests that Chino’s management opened the doors to women’s employment in a conscious and regulated way. The two powder drill laborers, for instance, occupied a new, separate classification; there were no male powder drill laborers. Peru Mining Company and its subsidiary, the New Mexico Consolidated Mining Company, also employed women during the war, as did the American Smelting and Refining Company (Asarco), but not in the numbers that Chino did.28 Clorinda Kirker, a Mexican American woman, worked underground at the Blackhawk mine when she was nineteen years old; she was in charge of the pumps at the 500-foot level, and she joined Local 604 in December 1942. “Probably she is the first girl in this part of the country to take over such duties,” the Silver City Daily Press commented, “but it is said that she performs her task with exceptional ability and carefulness and that there aren’t many men who could do much better.”29 In the context of wartime emergency, the occasional female worker could be accommodated. Later, Kirker married Frank Alderette, and in 1952 she played the role of Luz Morales in Salt of the Earth.

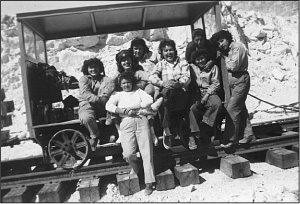

Women working at Chino during World War II. Photo courtesy of the Silver City Museum.

After the war, women left the mining industry. A few stayed on at Chino through 1945 and part of 1946, but by 1947, three of Kennecott’s four female employees were maids. The exception, Guadalupe Fletcher, continued to work for Chino and was eventually promoted to truck driver in the 1950s, retiring in 1983.30 Whether other women left voluntarily or were fired is unclear. But the employment history of Rita S. Jiménez suggests that she, in any case, did not wish to leave the mining industry altogether. After leaving Chino in 1945, Jiménez worked in Asarco’s Hanover office at least until April 1947, continuing as a union member once Mine-Mill gained certification to represent Asarco’s office staff. The 1950 census reveals 14 Grant County women engaged in primary metals manufacturing (mills and smelters), compared to 892 men. Only 22 women worked in the mining industry as a whole, compared to 1,313 men.31 While the wartime employment of women in mining was temporary, it nonetheless may have allowed some women to imagine alternatives to low-paid or unpaid work.

WORKING IN THE HOME

In Grant County, almost all adult women kept house, whether or not they also performed paid work.32 Indeed, throughout New Mexico in 1950, according to one marketing survey, New Mexican housewives “outnumber[ed] the women in all other roles combined, by a ratio of more than three to two.”33 By contrast, very few men kept house, even if they did not belong to the labor force.34 Male unemployment, then, did not free up men to do housework: the basic asymmetry in the sexual division of labor overrode the seemingly similar experience of not holding a paid job.

Women’s relative absence from the formal paid labor force did not divorce them from the local economy. The family wage economy was intimately, and thoroughly, tied to the formal economy of wages and production industries. Within the household economy, a clear division of labor prevailed. Men in mining families provided most of the family’s income from wage labor, and women, whether also working for wages or not, assumed almost complete responsibility for household work. Men and women alike were invested in marriage and stable families and in upholding the distinctions between men’s and women’s work.35 Moreover, women’s household working conditions resulted from their own, albeit indirect, relationship to corporate power, which was manifest in the housing available to workers and the credit arrangements in company stores.

Women’s unpaid work sustained the paid labor force. Feminist scholars of the 1970s and 1980s have interpreted household work as “reproductive labor,” which complemented the productive labor to which most Marxist analysts had long given their exclusive attention. Feeding and clothing their families, housewives maintained the living standards that enabled men, and sometimes children, to work for wages. The unpaid nature of housework, far from representing a holdover from precapitalist social relations, was instead an inherent feature of the industrial capitalism that developed in Europe and the United States. Capitalists’ ability to pay low wages effectively rested on the unpaid—and often unacknowledged—labor of women.36

Surveying the living and working conditions of women in coalmining families in 1925, the Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor drew similar conclusions about the importance of women’s housework to the entire industry:

The mine worker’s wife occupies a position of peculiar industrial and economic importance whether she falls in the class of gainfully employed or not. . . . The bunk house and the mine boarding and lodging house long ago proved themselves inadequate to attract a requisite number of workers or to maintain a stable labor supply. Only the presence of his family can keep the mine worker in the mining region, and because of the isolation of so many mining operations the mine worker’s wife assumes an unusual importance to the industry. The mine worker can not at will substitute the restaurant for family table as can the wage earners in other important industries. He is more continuously dependent upon his home for the essentials of health and working efficiency.37

In a practical sense, women’s housework consisted of a series of tasks that promoted their families’ well being: cleaning, cooking, laundering, buying food, and taking care of children. Alice Sandoval recalled her mother “always cooking, baking, praying, or nursing.”38 Uneven technological advances in municipal services and household appliances made working-class housework dramatically different from that performed in middle-class homes. Women could delegate some chores to children, but only the middle classes, both Anglo and Mexican American, could afford the labor-saving appliances that might lessen for housewives the defining burden and drudgery of housework, or the domestic servants who would relieve the burden altogether. Housework also had a managerial dimension. Housewives managed the family’s money, figuring out each day how to stretch a small income to cover many financial needs. Budgeting that portion of men’s wages that made it home did not mean, however, that women fully controlled the family’s money. Not only did working-class men bring home small incomes, but they also took out what they wanted before handing over the pay packet to their wives. Thus, household chores and family budgeting both acquired political and economic dimensions that underscored local class and gender power relations. Finally, women’s work in the home had an emotional aspect: women were caregivers, and the definition of their role in the family as that of nurturer shaped the ways in which they performed and thought and felt about their work.

Tracing the day’s work of a housewife allows us to analyze the implications of new technology and municipal services for women’s work. A woman’s work day began while her husband was still asleep. Cooking breakfast for her family entailed much more work than simply pouring a bowl of cereal. Into the 1930s, many Mexican American women still made their own tortillas at home, which required pounding corn or wheat masa by hand, rolling out the dough, and cooking the tortillas over a wood stove. Some women prepared tortillas to sell to neighbors, as did Bill Wood’s mother.39 By the late 1940s, Eligio’s Tortilla Factory, run by Eligio Ynostroza and perhaps also his wife, provided tortillas to nearby restaurants and housewives in the Bayard vicinity. It is likely that women still made their own tortillas, but only for special occasions, like Christmas.40 But even without having to make tortillas by hand, as some women continued to do into the 1950s, preparing the day’s first meal required a number of steps from which most middle-class women were free by the 1920s.

First and foremost, few miners’ houses had indoor plumbing, and Mexican American families were generally worse off than Anglo families in this regard. By the end of the nineteenth century, most urban areas had running water, if only from a tap in a tenement courtyard. But rural Americans carried water from an outdoor pump or well long into the twentieth century.41 The difficulty of getting and using water affected almost every aspect of housework, whether cleaning, laundering, or feeding one’s family. In the mid-1940s, Virginia Chacón, for example, enjoyed no indoor plumbing in her North Hurley house. Her husband, Juan, “had to make a cistern and he’d carry water from Hurley.” She explained, “We bought a jalopy truck, and a friend of his built him a tank, and he’d fill that tank with water every evening when he got out of work. . . . And then we bought a little electric pump and he installed the water inside.”42 This kind of small electric or gasoline-motored pump became common in rural areas in the early part of the century.43 The Chacóns improved their water facilities only gradually: prior to installing the electric pump, Virginia Chacón had to bring the water inside for every chore, and even with the pump, she had to heat the water on the stove and then dispose of waste water outside. As historian Ruth Schwartz Cowan reminds us, tap water is only a “small [part] of what we now consider the total water system. The full system contains pipes to conduct water into more than one room . . . , devices for heating some of the water and distributing it, as well as specialized containers . . . which make it fairly easy to use water for different purposes and to dispose of it.”44 Most or all of this system was lacking for many Grant County mining families.45

Insurance agent C. B. Ogás, visiting Grant County homes in the late 1940s, found that frequently “one [outdoor] water faucet took care of three or four homes with no indoor facilities” and that outdoor privies were the norm.46 Most of Hanover’s Mexican American residents lacked even a tap on the side of the house. Elena and Raymundo Tafoya shared a well with other town residents, and Matías Rivera, growing up in Fierro and Hanover in the late 1940s, had indoor plumbing in neither childhood home. His mother put him to work hauling the water. He was fortunate when his family moved, because Hanover’s well was closer to home than Fierro’s well had been.47 This deplorable situation did not change quickly for miners and their families. At the time of the Empire Zinc strike, fewer than half of Grant County’s dwelling units had “running hot water, private toilet and bath, and [were] not dilapidated.”48

Stoves generally burned wood, which required chopping, hauling, and igniting before a woman could cook the family’s meal, calling to mind the indignant tirade of Luz Morales in Salt of the Earth: “Listen, we ought to be in the wood choppers’ union. Chop wood for breakfast. Chop wood to wash his clothes. Chop wood, heat the iron. Chop wood, scrub the floor. Chop wood, cook his dinner.”49 Wood-burning stoves created more grime than did gas or electric stoves, and grime meant more work for a housewife. These stoves could prove dangerous, too. Adelaida Martínez Sánchez of Turnerville was badly burned when her stove exploded; a week later she died in the Santa Rita hospital.50 Local authorities traced many Grant County fires to faulty kitchen and heating systems. An oil-burning stove, for instance, seemed like an advance over a wood-burning stove to the Hubble family in Bayard, but an overflow of oil caused a small fire in their apartment.51

Cooking was a constant activity for a woman, who had to accommodate the varying schedules of her husband, family, and (frequently) boarders. A husband who worked on the graveyard shift, for instance, needed meals at unusual times of the day. The combination of fatigue, difficult work schedules, and dangerous living conditions combined in a tragic fire that killed one miner’s wife and her children in 1950. Anita Domínguez, a twenty-eight-year-old housewife, had gotten up on August 22 to prepare breakfast for her husband, Manuel, who was at work on the graveyard shift at Asarco’s Groundhog mine. Evidently she fell asleep again, and the wood stove burned down the wood-frame house early that morning. She and two of her children, ages ten and one, died before neighbors could get them out.52

Constant meal preparation also meant constant food gathering. The daily shopping might involve walking between one or more grocery stores to find the lowest prices; women knew which stores had the best deals for which items. Many stores delivered groceries to miners’ houses, and often mothers sent their children to the stores with lists if, as was likely, the family had no telephone. A woman often needed to shop every day because few families had refrigerators to store perishables. Refrigeration required electricity, which was more common than indoor plumbing, but often houses “were wired just for lights”; Matías Rivera and Aurora Chávez used kerosene lamps into the 1940s because their houses had only a single overhead light.53 Refrigerator prices reached affordable levels for many middle-class families in the 1920s and then dropped considerably in the 1930s.54 Anita Torrez recalled that after a year or so of marriage, she and her husband were able to purchase a refrigerator—one of the few appliances they had in their two-room house in Hanover.55 Growing up on a ranch near Hanover, though, Albert Vigil watched his mother use a cold spring as a refrigerator in the 1920s and 1930s. She eventually moved into Bayard, in fact, because of the conveniences there, leaving her husband to run the ranch without her.56

If refrigerators made it into some homes, washing machines did not. Fifty-two percent of American homes had power washing machines in 1941, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, but only the middle classes did so in Grant County.57 Laundering clothes and linens without a washing machine was difficult. Matías Rivera and his siblings hauled the water and heated it on the wood stove so that their mother could wash the clothes on a washboard, as did Bill Wood for his mother.58 Then came another round of hauling and heating for rinsing the clothes. It is little wonder that laundering has been one of the most eagerly abandoned household tasks for American women, and for women in mining towns, as in industrial cities, washing took on an even more odious dimension because mining was such filthy work. Men brought their sweaty, dirty clothes home (although changing rooms allowed some men to leave their work clothes at the mine), and women had to make those clothes presentable again. There were a few self-service laundries in Bayard: Mr. and Mrs. L. H. Gray ran Ruby’s Help-U-Self Laundry and D. F. Christopher ran Porter’s Help-U-Self Laundry. Clearly some residents made use of their services, but most working-class women did the work themselves.59

With clothing washed and hung outside to dry, women would then prepare to iron. Here, too, women, and sometimes children, worked without the benefit of the electrical appliances that became common elsewhere in the United States during the 1920s through the 1950s. A woman heated an iron on the stovetop, removing or replacing it frequently to regulate the heat. Performed in winter, this chore could heat up the kitchen pleasurably; performed in summer, it was stifling.60 The first appliance that Bill Wood’s mother got was an electric iron, which eased her son’s work hauling wood.61

Not all of Grant County lacked amenities like indoor plumbing or electricity. The Phelps-Dodge company housing in Tyrone, which closed when the mine closed in 1921, offered utilities to many of its residents, even some Mexican American families; Chino’s company housing outside of Santa Rita provided them to the Anglo workers.62 Silver City boasted substantial municipal services very early in its history. By 1887, it had telephone service, electric lights, and a public water system.63 The local newspapers regularly advertised gleaming electrical appliances like stoves and washing machines. But these examples, far from diminishing the deprivations suffered by the majority of miners’ families, instead underscored a critical aspect of local conditions: the maldistribution of technology and services.

While Silver City provided considerable amenities for some of its residents in the late 1880s, photos of the Mexican neighborhood of Chihuahua Hill from the period reveal dilapidated buildings, graphically demonstrating that municipal services were unevenly spread.64 As late as 1944, Chihuahua Hill residents petitioned for a sewer line; they got a gas line in 1946 when a gas main was extended to a new housing division just beyond Chihuahua Hill.65 Brewer Hill, southeast of downtown and the home of Mexican Americans and Silver City’s few African Americans, lacked adequate water connections. Its streets were so bad that firefighters had trouble reaching and then extinguishing a fire there in July 1948.66 In Santa Rita, recalled former resident George De Luna, the “Anglo side [of town] was paved by the company, while on the Mexican side, every time it rained the [dirt] roads would be washed out.”67

And when Juan Chacón brought water home every evening, it was precisely because, unlike the Anglo houses in Hurley, Mexican American homes in North Hurley lacked indoor plumbing.68 The situation was the same in Hanover. The Empire Zinc Company, which owned much of the housing there, provided indoor plumbing for its Anglo workers but not for the Mexican Americans.69 As Anita Torrez commented during the Empire Zinc strike, “Empire thinks us second-class workers,” undeserving of the plumbing that Anglos enjoyed.70

The prevalent myth that housewives did not “work” hardly reflected the reality of working-class women’s lives. Mining men in particular were not likely to think of their wives as working, when “work,” for them, connoted dangerous, physical work in the mines—not unpaid housework, divorced as it was from the very concept of the breadwinner. In Salt of the Earth, Luz Morales insists that women “ought to be in the wood choppers’ union” because women did hard work. And she resented the added insult of her husband’s attitude: “And you know what he’ll say when he gets home. [Mimics husband Antonio] What you been doing all day? Reading the funny papers?”71

MONEY

One way to understand the family wage economy is to consider both money and its absence. The flow of money and the effort to substitute housewives’ goods and services for commercial ones illuminate the relations between husbands and wives, and between the family and society. A miner’s wife typically managed the household’s budget, but this managerial duty took place within considerable constraints that operated on two levels, one from outside and the other from within the household. First, while mining paid better than many jobs, the work was frequently interrupted by layoffs during the downswings of the mining economy and strikes during contract negotiations (once the union was recognized). During wartime, a miner’s wife dealt with shortages of fats, sugar, and other necessities, and if she lived in a company town she had to pay inflated company-store prices. And a husband’s injury or death on the job was a constant possibility, regardless of war or strikes. Second, the household’s income passed first through the filter of her husband’s personal spending patterns. Wives in Grant County employed a number of strategies to keep their families afloat within these constraints, and constraints and strategies alike placed housewives firmly within, not beyond, the local economy.

The primary constraints within which a woman managed the household budget were the amount of wages and what she could do with them. Metal miners typically earned decent wages compared to local workers who performed other forms of labor, and over the course of the 1940s and 1950s miners’ wages doubled from between six and eight dollars a day to twelve or more dollars a day. Mexican American housewives, though, could count on their husbands to be at the lower end of the wage scale because of occupational segregation that resulted in a “Mexican wage” far below what Anglo workers earned. Serious unemployment crises in 1949–50 and 1952–53, as well as strikes, quickly dried up any family savings and made it hard for a housewife to make ends meet. Only a steady income could accomplish that, and the ebbs and flows of metal production—and the periodic strikes—made income unsteady. Moreover, a housewife was constrained by the cost of goods and services—costs that rose ever higher during the war (even with price controls) and then again once the U.S. Office of Price Administration lifted the controls in 1947. Prices remained stable through the early 1950s, but, again, this stability must be seen against the backdrop of unemployment surges.

Also shaping the decisions a housewife could make were her husband’s spending patterns. Men often turned over their pay to their wives, but not before taking a cut themselves. By cashing the check in a local bar, for instance, a man had the opportunity—if not the obligation, if he owed a tab—to leave some of the wages behind. Anecdotal evidence that men frequently cashed their paychecks in bars finds corroboration in the actual canceled checks from union bank accounts.72 One evening in October 1943, a distraught Tony Sena told police that he had been robbed on the highway. The investigation revealed, however, that Sena had lost the forty-three dollars gambling and “feared to go home without the money.”73

First among women’s strategies for coping with limited incomes was to live on credit. Every grocery store in the Central mining district extended credit at some point to its customers, and every person I interviewed recalled having kept a running bill at the grocery store. During strikes, some stores, like Southwestern Food and Sales of Bayard, extended credit and occasionally erased the union’s strike accounts altogether. Small businesses generally saw their own well-being tied up in workers’ wages. For example, while the Empire Zinc strike stretched the bonds of this limited cross-class solidarity, it is noteworthy that most of the bonds posted to keep strikers out of jail were provided by sympathetic local businesses.74 Checks paid to union members—reimbursements, or rewards for signing up new members during organizing drives—were frequently cashed at grocery stores and other retail establishments.75 Stores might have functioned as banks simply because they were convenient; with only two banks in the district—the American National Bank of Silver City and the Grant County State Bank in Bayard—someone who needed to cash a check on the weekend or in one of the smaller towns would have been out of luck if stores did not cash customers’ checks. It is reasonable to infer that sometimes the check casher left some of the cash in the till to pay off debts.

Besides living on credit from month to month, most working-class wives kept expenses down by replacing purchased goods and services with goods they produced themselves; at other times, they simply did without. They supplemented the family’s income by working for wages, taking in boarders, or marketing goods produced at home. None of women’s paid work eliminated housework. Indeed, for those women who took in boarders, the work was an extension of their existing housework and increased that workload. Elena Tafoya’s mother ran a boardinghouse, first in Santa Rita and then in Bayard in the late 1930s, feeding meals to miners each day. Matías Rivera’s mother was providing the same service to miners in the late 1940s, as well as running a bar that another son owned. Boarding and lodging characterized life in mining camps, in the United States as elsewhere, but much less so by the 1950s.76

Many women had to work outside the home in order to make ends meet, and they performed this work on top of whatever housework they could not delegate to children. Paid workers were always the minority of Grant County women. But the difficulties facing families with uneven or inadequate income—or, especially, those without a male breadwinner—made some female employment a part of many a family’s strategy to survive.

POWER STRUGGLES

Cooperation and conflict shaped working-class marriages in Grant County. Men and women frequently agreed on the obligations of husbands and wives; men should provide wages, and women should make a home. The terms of the family wage economy were not necessarily at issue. But individuals could not always meet their obligations within that economy, and couples could not always agree on exactly what constituted meeting them. The relative power of husbands and wives both reflected and determined these negotiations.

Despite the interdependence that defined the family wage economy, not all couples stayed together. During and after World War II some men left their families, either to find better work elsewhere or to escape altogether. Several—almost all Mexican American—found themselves hauled before District Court Judge A. W. Marshall for abandoning their families. Sentences ranged from six months to a year in jail, sometimes with hard labor, but the judge typically suspended the sentence if the husband agreed to support his family.77 Dislocations of wartime accounted for a rash of divorces in 1946 and 1947. The Silver City Daily Press commented on “the usual grist of divorces filed” in November 1946 and on the “flourishing divorce business” of the year as a whole: 179 of Grant County’s 304 civil cases were divorces.78 Perhaps because of the cost and the Catholic proscription against divorce, proportionally fewer Mexican American than Anglo couples divorced; the ratio was approximately one to five.79 In addition, some Mexican Americans lived in common-law marriages, which would have made divorce unnecessary for those couples who wanted to part ways.

Domestic violence disrupted many households. Dolores Jiménez, for example, was brutalized by her husband, Frank, during both of her pregnancies, before she was even twenty years old. “I shouldn’t say this,” she said later. “That was the greatest thing, to have my two boys. But that’s one of the things I didn’t care [for in] being married. Because I was abused, every which way. Pregnant and everything. I don’t think it’s right. But I wouldn’t change my two sons for anything, and I’ll go through fire for them, but that’s one of the things I didn’t like. If I had to have kids again and go through that, there’s no way. There’s no way I would let it happen. Being dragged, being hit.”80

Rarely did this kind of violence make it onto the public radar screen, much less into the courts. But in Grant County there were enough published notices of husbands charged with assaulting their wives to dispel any idea that this was a completely hidden crime.81 Both Anglo and Mexican American husbands tried to keep control over their households by beating their wives. Certainly these were not private conflicts, in the sense of no one else knowing of them; neighbors were very likely to hear violent conflicts. But they remained private in that rarely did anyone intervene to stop them. The case of the Montoyas is illustrative. Cipriano was a physically imposing man, used to exercising power at home, as well as in the union hall. Feliciana (“Chana”) had married him when she was quite young, and she had few resources with which to resist his violence. Other union officials, including men close to the Communist Party and familiar with its critique of male chauvinism, knew about this abuse, but no one confronted Cipriano or tried to help Chana.

Rarely did these conflicts end in divorce. Dolores Jiménez tried to deal with Frank’s violence by running out of the house. She did not want to leave him because he was a good provider—even though she also knew that he had been unfaithful to her.82 One exception is the McNutts, a couple who often tangled with the Empire Zinc picketers (see Chapter 5). Homer McNutt was charged with assaulting his wife on several occasions in 1946. She had evidently had enough by 1948, when she successfully sued for divorce, yet just four months later Homer again pleaded not guilty of assaulting his wife.83 Sometimes these conflicts resulted in shootings, if weapons were handy, and even if a woman got out of the marriage, there was no guarantee that she had escaped the power of an angry ex-husband. Certainly most families did not experience this kind of violence, but the examples serve to underscore how men possessed a prerogative to keep their families in line by force.

AN UNEASY RESOLUTION

Women’s awareness of the interdependent nature of the family, and their knowledge of the critical contributions they made with the work that defined each day of their lives, proved essential to their ability to imagine, contemplate, and eventually insist upon playing an active and ultimately transformative role in the Empire Zinc strike. They arrived at that awareness over time, as they became more involved in the union. The film’s matter-of-fact depiction of Esperanza’s and Ramón’s work shows a recognition, generated by the Empire Zinc strike, of women’s and men’s respective contributions to the family’s survival, of women’s unpaid housework as work on a par with that performed by the “breadwinner.”

The women’s picket challenged husbands to shoulder some of their wives’ responsibilities, and some men did change, at least temporarily. “It sure was a shock to us women,” one picketer remarked, “to find out that our husbands were such good cooks and housekeepers and the shock to the men that their women could hold the picket lines as well as they have.”84 Clinton Jencks, Bob Hollowwa, and Cipriano Montoya explained the process to the international’s executive board in August 1951. Interestingly, they focused on the problem of men helping women at the picket location, although housework had also been under discussion; they were trying to cast the strike in the most positive light possible, and perhaps introducing another level of complexity ran counter to their aims. “In the past few weeks considerable improvement has been made in organizational problems which have come up from time to time,” they reported. “Such problems as the participation of strikers in helping the women with work in and around the picket line—such as hauling water, chopping wood, furnishing transportation to women pickets, carrying out the numerous odd jobs required at the picket line. Solving these problems have been accomplished by and thru ‘frank’ discussion of all the people involved.”85 Symbolizing these changes was the preparation for a dinner to celebrate the first anniversary of the strike. Local 890 president Cipriano Montoya asked which woman would head the food committee. Mariana Ramírez, captain of the women’s picket, asked if the dinner was meant to honor the women; reassured that it was, she suggested that Montoya ask “what brother would volunteer to head the food committee, because, personally, she expected to sit all through the celebration and be honored.” Ramírez got what she requested. “The evening of the dinner the men were at the tables serving the food and cutting the hams and sweeping the floors.”86

But even with men assuming some of women’s duties, women often relied on other women to pick up the slack. “All those women we didn’t see,” Dolores Jiménez recalled, “they were taking care of our kids. The men were maybe taking care of the kids, some took us to the picket, some were busy, some were in the bar drinking. And some were angry, [wondering] how long is this gonna go on.”87

Ernesto Velásquez provides a good example of the complexities bound up in men’s experiences of the women’s picket. An employee of Empire Zinc since 1948, he quickly assumed leadership within the Empire Zinc unit of Local 890. Velásquez chaired the strike negotiating committee and emerged as one of the women’s most consistent supporters. Unlike Cipriano Montoya, who generally referred to the strikers as “brothers,” Velásquez acknowledged women as full-fledged union members. (He was by no means alone in this; several men did so.) He frequently and publicly encouraged women to participate, and the steady participation of his wife, Braulia, speaks to his willingness, on some level, to put his money where his mouth was. On the occasion of the strike anniversary, for instance, he described to the union brothers and sisters how he felt “as a newborn, . . . good as to how solid everything has been over the past year. One year of suffering of our strikers. . . . The women . . . knew nothing about strikes but [now] they are veterans. The women were tear-gassed, jailed, these women have suffered.”88 In stressing women’s suffering, Velásquez did not dwell on men’s failure to protect their wives. Instead, he cast it as women’s strength in the face of company assaults. Such a picture drew on an unassailable cultural value, that of women’s patient strength. Moreover, he acknowledged that he himself had been transformed: he was the newborn, birthed by these women.

At the September 1951 Mine-Mill convention, Velásquez again expressed appreciation for the women picketers. But here, in this national setting, a convention primarily of men, he also expressed ambivalence. Joking about the role reversals effected by the women’s picket, Velásquez revealed some of his discomfort and, perhaps, his way of easing it: “We will see what my wife says—and I hate to be calling her a wife now—she’s the boss of the family. It so happened the 13th of June she took over the household. We have a little baby and she said you go home and wash the dishes and change the diapers. That puts me in an embarrassing situation. I have washed the dishes and I have swept the house, but one thing I cannot get myself to do and that is change a diaper. Let’s see what Sister Velásquez has to say.”89 Sister Velásquez had nothing to say about “taking over the household”; instead, she described the picket and her time in jail. There are any number of reasons why she might have remained silent on the topic that her husband had so clearly and so publicly raised. Perhaps she believed that nothing of substance had changed, or that the subject was too touchy to be aired in this public setting. Perhaps she felt that Ernesto had used humor to trivialize the extent and meaning of changes in gender relations and had thereby won over the largely male audience to his own perspective. For what could be more ridiculous than a female “boss of the family”? And how could a man boss the family if he had to change diapers? What, indeed, could changing diapers represent, if not the debasement that necessarily accompanies wifehood?

Enough men accepted the changes, at least for the duration of the strike, for the strike to succeed. In January 1952, the Empire Zinc Company finally returned to the negotiating table and agreed to a contract that granted many of the union’s demands. Some weeks later, the company quietly agreed to add indoor plumbing to all of its company houses—a demand raised as early as 1949, but one that the male negotiating committee had quickly abandoned when it was challenged.

Throughout the summer and fall of 1951, then, women undertook two sorts of defensive actions. The first was to defend their community against the company and the scabs, police, and local court functionaries that the company marshaled. The second was to defend their actions against the resentment and active opposition of their own husbands, who believed that domestic relations should remain constant lest the community be fractured. Convinced that their motivations and actions were just, women picketers bristled at the opposition they encountered from husbands and insisted that the real threat to stability and unity lay with men’s “backward” ideas.

Once the strike ended, however, the pull of the old ways proved very powerful. Men and women alike desired things to get back to normal, even if they were not sure exactly what that would look like. They all had a stake in making the family unit work. The Empire Zinc strike may have made many couples rearrange the assignments of authority and responsibility, but the strike’s conclusion did not consolidate those changes for all of them. Strike families’ experiences making Salt of the Earth show both how household power relations were still uncertain and how women were making use of their strike experience to continue to shape those relations.