8 A Progressive Vision of Popular Culture

MICHAEL WILSON VISITS THE PICKET

Henrietta Williams noticed him up on a hill. He was a stranger, dressed casually but not in workers’ clothes, gray-haired but probably only in his late thirties. He was watching the women as they walked in their circle outside the Empire Zinc mine in Hanover early in the fall of 1951. Williams, a picket captain, suspected that “he was a company man, that he was writing down names to take us women to jail.” She was certainly prepared to confront him: months on the picket line and a week in jail made her a force to be reckoned with. The picketing women were surprised to learn instead that he was a writer from Hollywood, interested in their stories. So “we let him come down and drink coffee with us, talk to us,” she explained later.1

The man was Michael Wilson, and he had come to the women’s picket because his brother-in-law, producer Paul Jarrico, and director Herbert Biberman wanted him to tell the women’s story in a screenplay that would be produced by blacklisted artists in a new film company, Independent Productions Corporation. In fact, Wilson had been reluctant to visit Grant County. Blacklisted after invoking the Fifth Amendment before the House Un-American Activities Committee on September 21, 1951, Wilson had finally begun working on a novel. Only after Jarrico and Biberman agreed that the people of Local 890 would exercise final say over the script did he take on this new project instead. “If you think something’s great and they think it’s lousy,” he warned, “they’re going to win.” They were “to be the censors of it and the real producers of it . . . in point of view of its content.”2

There, by the picket line, Wilson interviewed the women, “what [they] thought, what [they] were doing, how hard [it was] walking in that sun, so hot.” He wanted to know what the women thought would happen and whether they were going to win. “All those things he asked,” Henrietta Williams recalled. “He asked a lot of questions, and we answered them. Everything that was true, we told what was going on there.”3 Wilson stayed in Grant County for a month, and he kept himself on the margins, not drawing attention to himself. “He sat by the picket line,” Clinton Jencks remembered. “He sat in the union hall. He went to the dance. He sat in our homes. We talked, you know. But he didn’t hardly say anything. You wouldn’t know he was there. . . . He had this capacity to just become a part of the thing so that people weren’t self-conscious and were just going ahead and doing what they were doing.”4

Wilson may not have said much, but he was deeply affected by the solidarity that the union families demonstrated. Most men had first opposed the women taking over picket duties, fearing violence and a threat to their authority in the household. By the time Wilson visited, though, many had grudgingly taken on some of the women’s work. The situation in Grant County also impressed him with its complexity: “There are battles for equality taking place there on so many levels I can hardly unskein them myself,” he told Biberman when he returned to California.5 Wilson did not rush to interpret those battles in a definitive way; indeed, it took him three months to figure them out and write an initial scenario. Wilson concluded that one form of equality was hollow in the absence of the others, and he anchored his screenplay in the idea of the “indivisibility of equality.” The strike began as a struggle for ethnic equality. But once women took over the line, “the struggle for equality move[d] to a new level, which include[d] the old.”6 Only after men accepted women as equals, and Anglo and Mexican American workers allied with one another, could the mining families sustain and ultimately win the strike. Wilson’s script did not focus on the history of Local 890’s political and community activism of the 1940s. Instead, it centered on personal relationships, which may have been more suitable for the kind of drama he envisioned: something that would make viewers identify with the characters and appreciate the transformations they underwent. In this respect, Salt of the Earth was able to portray precisely the kind of conflict—one between a husband and a wife—that had been largely neglected by the union until the Empire Zinc strike brought it to center stage.

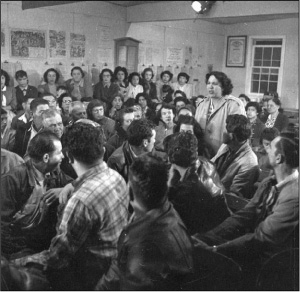

Wilson returned to Grant County in January 1952, just as the strike was coming to an end, to read the screenplay’s outline to the union families.7 Gathered in the union hall, at first “everybody just sat and listened,” Clinton Jencks recalled. But before long “they began to interrupt. It was not a self-conscious thing. They’d say, ‘No, no, it wasn’t like that at all.’”8 Virginia Chacón said that the script had “too much Hollywood stuff. We [told] him, ‘It has to be the real thing.’”9 Lorenzo Torrez objected to a scene in which Esperanza used her dress to wipe up a beer spill. He felt it reinforced “the stereotype that Chicanos are dirty, and that they aren’t smart enough to use a towel.”10 And one union member felt that “the screenplay had the liberal white man—modeled on Clinton Jencks—saving the Mexican masses.”11

There was a clear gender division in the script’s reception. The men overruled an adultery subplot, an objection that the women derided. “Oh, you’re all so pure!” they jeered. “You don’t do things like that?” The women, for their part, rejected the depiction of too much drinking: “Our husbands are not drunkards,” they insisted.12 Whether men or women prevailed on a particular point depended on their relative strength in articulating their positions, but women’s recent history of organizing and leading the strike gave them additional clout in the script discussions. Had union men alone been consulted, for instance, it is doubtful that men would have been portrayed as comically as they often were.

Michael Wilson understood his task to be honoring the people of Grant County, and he believed that to do them justice meant to defer to them—albeit after rigorous discussion—on critical matters. Whatever beliefs about workers or ethnic minorities he brought with him, he did not apply them indiscriminately to a passive and inarticulate people. He listened carefully to the historical actors and tried to recast his own thinking to match their situation. And whatever shyness Local 890 members may have initially felt upon meeting glamorous Hollywood people, they clearly and forthrightly expressed their own opinions about the project and the way it should be done. After all, they had plenty of experience seeing Mexican Americans portrayed stereotypically and disrespectfully on film. This was true both of Hollywood’s movies, as one might expect, and of Mexican cinema, which stereotyped Mexican Americans as deracinated pachucos.13 Perhaps the union families’ predisposition to critique Wilson’s script reflected the influence of the cultural activism of the Asociación Nacional Mexicana Americana. In any case, they found a ready listener in Michael Wilson. As Clinton Jencks put it, “Any communication is two-way. Since people were telling their own story, they had a right to say it the way they wanted to say it. And that’s one part. But I think the other part of it is there was somebody that would . . . listen. So it was worth saying. . . . We had to take some risks in criticizing these people that came from so far. . . . But similarly, it had to be important enough to [IPC] to be able to accept that criticism.”14

Charles Coleman as Antonio Morales, ruefully hanging laundry to dry. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lot #A108.

Wilson accepted the criticisms. He did not, as Jencks put it, “have to defend [the script] as a child.”15 The excised scenes, Wilson explained to Biberman, were “perfectly legitimate dramatic scenes and illustrations. In a script in which you’re after drama for its own sake, they’d be perfectly acceptable. But we’re dealing with something else. Not just people. A people. And you don’t necessarily express them in naturalistic detail. You have to really synthesize them, all of them; the weaknesses and the virtues, until the individual expresses a real element of the whole and not something untypical of the whole, even though a variant of it.”16 Some men were unfaithful to their wives, Wilson acknowledged, but to project that on screen might only reinforce stereotypes of “the sensuous, promiscuous, Latin male.”17 Even on purely dramatic grounds, he thought the adultery subplot was poorly resolved.

Another detail in the original outline that did not appear in the final script was the role of religion and the Catholic Church in Esperanza’s life. In the outline, Esperanza’s devotion to the Catholic Church serves as a barometer of her political consciousness: as she becomes more involved in the strike, the church exerts less influence on her. Perhaps this device rang untrue to the many Empire Zinc strikers who appreciated the support given by Father Smerke of Hanover’s Holy Family Church; certainly these mining families had little trouble reconciling their religious beliefs with their union activism, and when they did encounter antiunion sentiment from priests they did not hesitate to criticize it.18 In any case, Wilson’s deference to criticism from the union was the key to synthesizing the disparate parts of the community. After six more months, Wilson came up with a script of which Local 890—men and women—approved.

The unique way in which Wilson crafted the script for Salt of the Earth was part of creating a new kind of popular culture, one in which working people themselves, allied with artists, would dramatize their own struggles. Independent Productions Corporation, incorporated in September 1951, was created in order to make this new kind of movie. Employing blacklisted artists, IPC would fight McCarthyism; even more importantly, it would contribute to a democratic culture, its entertainment presenting, as Biberman described it, “people to people in such a way as to give them their own experience clarified, organized, enriched—to such a degree that it gives confidence and faith and direction.” And people would see more than their own individual stories. They would see the stories of other Americans and begin the hard process of talking to one another, of discarding “the distrusts and hatreds which have been foisted upon them—and [of finding] joy and hope and fulfillment in each other.”19

The stakes were high in cultural politics, and Biberman knew precisely what he did not want: to follow the popular media’s prescription for attracting a female audience. The “publication True Experience,” he observed, “urges writers to submit ‘hard-hitting, earthy love stories.’ It continues: ‘What does the everyday woman want? Give her marriage and seduction. Give her Cinderella and rape. Give her love and delinquency. Give her addiction, adoption and abandonment. Give her crime, abortion and frigidity. Give her insanity and murder. Every man and woman having an affair must pull toward each other with so much gravity that the earth stops spinning.’”20 Without an alternative medium, Biberman believed, American cultural values would deteriorate. People would become inured to violence and brutality “until, little by little, the horrible finality of official brutality, which yesterday they would have called fascism and resisted, tomorrow they accept only because they yielded little by ever so little all along the way.”21 Perhaps Biberman, more than other members of IPC, exaggerated the stakes in cultural politics, but all of them shared a vision of popular culture in which filmmakers could venture onto socially critical or ambiguous terrain. They were convinced that IPC could offer Americans something truer to life than anything True Experience would publish.

This vision of cultural politics provided the foundation for Salt of the Earth. It was influenced by, but not coextensive with, Hollywood Communists’ theorizing on culture, which in turn influenced the way IPC would address the themes of race and sex discrimination that Communists had long theorized about and organized around. Wilson’s starting point was the Communist Party (CP) consideration of the “Woman Question”—this was, in fact, the first title of his screenplay, and hardly anyone besides Communists continued to use this nineteenth-century term.22 But Wilson parted company with CP thinking by placing the Woman Question at the center of a feature film that addressed sexism, first, as a serious and substantive problem and, second, as a problem connected to but neither determinant of nor subordinate to ethnic and class inequality. Wilson was probably predisposed to do so because left-wing women in Hollywood had pushed the party to discuss women’s issues, including housework. When asked how he came to write a story about miners that focused on miners’ wives, Wilson replied, “I never conceived of it any other way.”23 But even more important, the families in Grant County wanted to portray their struggle in this way. If Wilson had the lead female character, Esperanza, bravely confront her husband in one of the turning points of the film, it was because the women in Grant County told him to do so. The script reflected their recent history and the leverage women had gained.

In this chapter I first analyze the efforts of Hollywood Communists to determine their role in film production, efforts that took place in a number of settings in the 1930s and 1940s. Next, I examine IPC’s first projects to show the lessons its filmmakers learned in trying to translate their political beliefs into art, lessons they brought to the production of Salt of the Earth in 1951–53. Finally, by analyzing the film’s production, I take up the themes of authenticity and the meanings of representation in this most unusual worker-artist alliance.

In a climactic scene in Salt of the Earth, Esperanza (Rosaura Revueltas) confronts her husband Ramón (Juan Chacón). Note the protective image of the Virgen de Guadalupe behind her. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lot #A108.

COMMUNIST FILM THEORY

To work as a Communist in Hollywood was to work within severe constraints. No studio gave free rein to its writers’ imaginations (as we saw in Chapter 7), and Communists, individually and as a group, struggled to define the relation of cultural production to political conviction. They never fully succeeded in developing a Marxist aesthetic that they could practice in Hollywood’s film industry.24

Two positions regarding the place of Marxism in Hollywood film production emerged in the course of what Paul Jarrico later described as “knock-down/drag-out fights” on cultural politics.25 The dominant view was reductionist and didactic: genuine communist art would explicitly advance the class struggle. Since the studio system was a purely capitalist institution, it would never brook radical film content; thus it was futile and fundamentally misguided for Communists to tamper with the ideological trappings of the superstructure, as opposed to the economic base—the real source of power and real site of political transformation. This analysis received some sanction from Earl Browder, who led the party from 1934 to 1945. According to Richard Collins, a former CP screen-writer who testified before HUAC (in the same hearings in which he named Paul Jarrico as a Communist), Browder instructed the Hollywood branches not to inject films with Communist ideology.26

While Browder may have subscribed to this reductive view of culture, he also represented the Popular Front and, during World War II, adopted an accommodationist policy toward American business, both positions helping to generate the alternative vision of culture discussed below. Thus, when the party repudiated “Browderism” in 1945 and predicted instead a period of unavoidable class conflict, it adopted an even more rigid cultural policy. An episode in 1946 reflected this change. Albert Maltz, soon to become one of the Hollywood Ten, raised the issue of creativity and radical politics in an article for the Communist publication New Masses. Thinking of art as no more than a weapon in the class struggle, Maltz argued, was a “straitjacket” that he had had to abandon in order to write anything at all.27 Even though Maltz’s opinion was widely—if tacitly—accepted among many CP members in the arts, his article provoked a storm of abuse from the centers of party power. Chastened, Maltz recanted his views within a month. V. J. Jerome, head of the party’s Cultural Commission, also expressed the harder line when he reviewed postwar films about African Americans in 1950. Although films like Pinky and Home of the Brave portrayed African Americans in a sympathetic light, Jerome interpreted those slight improvements as diversionary tactics, which only bolstered the underlying strategy of monopoly capital.28 Communists should not deceive themselves, either as audience or as creative artists, about the real nature of these cultural expressions.

The “Maltz Affair” was widely cited by anticommunists “as proof of a totalitarian Communist effect on popular culture.”29 But as historians Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner point out, the episode was more complex than that: when Maltz first submitted his article to New Masses, the editors approved it “virtually unanimous[ly]” and anticipated “vigorous and high[-]level discussion.”30 Moreover, when Maltz met with national leaders, he was joined by several other screenwriters who stoutly defended Maltz’s position, and none of them was actually punished. Buhle and Wagner interpret the controversy “as a continuation of an old discussion” in a period when the national leadership was trying—and generally failing—to rein in the Popular Front aesthetic sensibilities of its Hollywood artists.31

Future IPC associates Herbert Biberman, Sylvia Jarrico, Paul Jarrico, and Michael Wilson shared those sensibilities, which placed them in the second camp of Hollywood Communists of the 1930s and 1940s. They believed that there was always room, and therefore always the obligation, to introduce progressive ideas into cinema. Films reached millions of people, and radicals should neither abandon commercial film production to the mercies of the politically reactionary nor forsake it for documentary production alone. Biberman related that Lazarus had approached him early in the 1940s to start an independent film company. At the time, however, Biberman believed that progressives needed to work within the mainstream of the industry—the good favor that Communists found during World War II was not to be passed up.32 Sylvia Jarrico observed that radical writers “did not look to alternative film making. They believed that socially responsible writers belonged in the film industry because feature films were the most significant way in which the people of the world were being educated. The medium reached so far, that any victory was important.”33 Paul Jarrico insisted that “if you could change their attitude toward women, workers, Blacks, and minorities in general—and you could—then that was an important contribution. Sure they wouldn’t let us make a really revolutionary picture, but if we were good writers and skillful at our craft we could subtly affect the content [toward progressive ends]. It was a battle we did not resolve at the time.”34 Michael Wilson believed that the humanist writer “did not meekly deliver what the philistine ordered, but struggled tenaciously to preserve human values in all his work; . . . Hollywood writers in particular, dealing like all their kind in the radioactive commodity of ideas, were accountable to the peoples of the world for the effects of their ideas.”35

“Humanism” was not a term that most Communists employed, and perhaps Wilson’s usage here, and elsewhere, points to his way of navigating the political waters of Communism in Hollywood and of fashioning a powerful feminist story in Salt of the Earth. Committed to Marxist class analysis, Wilson nonetheless asserted a standard of “human values” that would, first, supersede a reductionist Marxism and, second, open to artistic exploration a world of topics taking as their starting point a concern with the human condition. In speaking of “humanism,” Wilson was asserting the legitimacy of artistic work that would otherwise have been dismissed by Marxists as “bourgeois.” This position was considered the “right-wing opportunist” position, as opposed to the “left sectarian” position.36

In this manner, Wilson was carrying on the discussion that had developed in several Popular Front–style organizations for Hollywood artists. The League of American Writers (LAW) sponsored screenwriting classes beginning in 1939. Led by writers such as Paul Jarrico, these classes addressed technical and political questions alike and were conducted as workshops, rather than as formal lectures.37 Jarrico recalled that these workshops fostered fruitful debates between “historians” and “humanists,” the former trying to grasp characters’ historical motivations and the latter “look[ing] to the story as story, probing . . . more for interpersonal conflicts.”38 The Hollywood Writers Mobilization (founded in 1943), in many ways a continuation of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, continued the Popular Front by bringing together leftists, liberals, some industry executives, and academics both to promote wartime unity and to set the stage for a transformed film industry after the war.39 Finally, two film theory journals, Hollywood Quarterly (1945–51) and Hollywood Review (1953–56), pushed far beyond the film criticism of party organs like New Masses or the Daily People’s World. Hollywood Quarterly grew out of the Hollywood Writers Mobilization and brought together leftists and liberals under the respectable aegis of UCLA, which in turn ensured institutional freedom from party control. Sylvia Jarrico was its managing editor; her graduate adviser, psychology professor Franklin Fearing, was its editor. Screenwriters, animators, composers—all sorts of film practitioners, as well as academics, wrote about the social and political implications of film technique and genre.40 However, the journal did not survive the blacklist era with the same ecumenical theoretical approach or left-wing participation. Hollywood Review was an attempt by Helen Levitt and Sylvia Jarrico in 1953 to rekindle Hollywood Quarterly’s critical edge. Jarrico herself wrote a piercing feminist critique of what she called the “Evil Heroines of 1953.” “The complacent theme that submission is the natural state of women,” she wrote, “has given way to the aggressive theme that submission is the necessary state of women. . . . Hollywood’s sinister heroines [were] ruthless killers” who reflected the Cold War counterattack on women who had been mobilized for war.41 Jarrico connected Hollywood images of women to the Cold War push to get women to leave paid employment. Hollywood Review also paid particular attention to race and racism in American film and film production.42

Conflicts over radical artists’ role in creating popular culture—whether or not the media would permit progressive ideas, however defined, into the mainstream of cultural production—should not mask, however, one essential similarity between the two basic positions staked out by Hollywood Communists. Both were predicated on a left-wing critique of mass culture that assumed that the audience was only a passive receptacle for the media’s productions.43 In this formulation, the public simply ingested whatever the popular culture served, whether conservative or progressive on race and gender issues. Biberman’s excoriation of True Experience was actually part of a long tradition of radical cultural criticism that labeled popular culture decadent and often pornographic, gratifying people’s basest instincts without stimulating people to crave something nobler.44

EARLY IPC PROJECTS

The evolution and structure of IPC also tell us about its members’ political beliefs, both implicit and explicit. While IPC members’ ideas about representing working-class struggles, and the ethnic and gendered dimensions of those struggles, had their origins in CP theory, they transcended the confines of CP analysis. Even more importantly, IPC members developed their ideas in the course of implementing them in specific projects. By the end of 1951, IPC was considering several ideas for feature films, all of which concerned either the situation of ethnic minorities or the question of individual conscience and the state. A screenplay by Dalton Trumbo (exiled in Mexico) portrayed an African American nurse accused of being a Communist. Paul Jarrico wrote a script about an atomic scientist who came to accept the government’s argument that the “bomb is our strength.”45 While she did not develop a screenplay herself, Sylvia Jarrico’s ideas on women in cinema might also have influenced the development of IPC. The first project slated for production, though, was a feature about the Scottsboro Boys, nine African American men in Alabama who were convicted in the early 1930s of raping two white women. One woman later admitted that she had fabricated the story, partly under coercion from local authorities. The CP’s International Labor Defense had taken on the case and publicized it across the country at a time when the Birmingham African American elite and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) backed away.46

IPC had trouble developing the Scottsboro story as a feature film, however, and never managed to write a successful screenplay. The company ran through “half a dozen approaches” before consulting African American artists in New York City.47 Director Biberman reported that the IPC screenwriters were surprised and somewhat embarrassed not to have known more about the contemporary “Negro Liberation Movement.” “Then we began to see some forest and some trees . . . that the Negro artists were not ‘experts’ on Negro subjects to be consulted when we white artists had come a cropper . . . but they were really leading the most vital and numerically significant cultural fight in our country today, and that it was a pretty late date for us to come to them . . . let us face it, a lily-white company . . . and ask for favors.”48 The shortcoming of the Scottsboro story, according to Biberman, was that it portrayed victims when it should have shown “the Negro people in action”; the reason IPC had failed in this respect was that “the stories had to be conceived by Negro artists and developed under their understanding [and] guidance.”49

Underlying Biberman’s explanation of the Scottsboro project’s failure were complex ideas of political theory and practice. IPC sincerely desired to show African Americans in a favorable light, to restore dignity to their history through an artistic medium that had kept them subjected to white supremacy. This imperative came out of humanism and a CP analysis that kept the struggle of African Americans in the foreground; the party saw African Americans as an “oppressed nation,” the struggles of which were in and of themselves revolutionary.50 Yet, finally freed of studio censorship, and armed with the “correct” analysis and political sensibilities, IPC still had trouble creating a genuine and compelling reflection of African American life. None of its approaches rang true; the mere belief in racial equality, however sincere, was inadequate to the task.

Those same political convictions, challenged by what they first believed was no more than an aesthetic problem, nonetheless formed the basis of IPC’s action on the Scottsboro project. For, to these Communists, the structure of their organizations had to embody their political convictions. Biberman and the others in IPC recognized that the “lily-white” composition of their company was more than a problem of image: it also compromised the very art that they sought to create. Frequently, the party paid no more than lip service to full representation in leadership and membership, just as the democratic centralism that characterized the party’s hierarchy was always more centralized than democratic. Still, the CP was far ahead of other interracial organizations of its day in searching for and promoting African American leadership. (The same was not true of female leadership.) Indeed, Biberman’s comments have the timbre of the breast-beating confessions of white chauvinism that the party occasionally demanded of its members.51

But any tendency toward histrionic self-abnegation was tempered by Biberman’s immediate action: not to purge the company of the people who had been shortsighted but to solicit the active participation of two notable African Americans in the arts. Carlton Moss and Frances Williams joined the company late in 1951 as vice presidents and producers. Moss had written and produced plays for the Federal Theatre and had written radio scripts for NBC. During World War II he produced a film for the War Department, The Negro Soldier, which many white soldiers and “almost every black [soldier] in the Army and Air Corps” saw between February 1944 and August 1945.52 Williams was an actress who had helped start an African American community theater in Cleveland when she was a teenager. She served on the executive board of Actor’s Equity and on Los Angeles’s Central Labor Council, and she had had plenty of experience with Hollywood stereotyping, once “ma[king] a stir by refusing seventeen different bandannas for her role in [a] remake of Show Boat.”53 Never, according to Biberman, had black and white people together formed a film company in the United States. He hoped that IPC’s example would inspire African Americans to prod Hollywood to integrate its own studios. IPC scrapped the Scottsboro story and instead adopted a project Moss had begun elsewhere, a biography of Frederick Douglass in collaboration with the National Council of Negro Women. John Howard Lawson agreed to write the screenplay. But once IPC got the idea for Salt of the Earth, and a commitment from Mine-Mill to support the movie, it moved forward with that project and placed the others on the back burner.

FORGING A WORKER-ARTIST ALLIANCE

Michael Wilson reminded Biberman that the problem with earlier IPC projects, like the Scottsboro script, was that they were trying to tell people’s story “from our point of view.” Salt of the Earth would be something different. The goal was to convey the essence of this people, and the means to do so were to be found in a worker-artist alliance in which the workers provided more than raw material for artists to fashion into a movie. This alliance depended not only on workers’ participation in creating the script, as we saw above, but also on careful decisions about casting and on a formal structure that ensured equal participation of union families and artists. These arrangements allowed the union families to reenact and recreate the drama of the strike and, in so doing, to process the changes wrought by the strike while making connections to blacklisted artists, blacklisted technicians, and sympathetic audiences.

Casting

Herbert Biberman came to Salt convinced that a nonprofessional cast consisting of the miners’ families would prove vital to the film’s success. Excited by Soviet theater in the early 1930s, as a young director in New York Biberman had united professional and nonprofessional Chinese American actors in the play Roar China. Biberman saw his role as one of drawing out the essence of “the people,” and he discovered that “the Chinese developed a homogeneity, a group presence, that endowed each individual with stature that was a gift from the whole. It brought a power in relaxation to them that few actors achieve. If they brought less skill, they brought the authority and dedication of their own persons and that incomparable thing—the reality of a people.”54

Biberman’s correspondence with the leaders of Mine-Mill reflected his excitement at the thought of working with the mixture of “the skill per se” of professional actors and “the authenticity the real people have.”55 He showed a genuine commitment to utilizing the talents of Mexican Americans, not just to depicting them. (He preferred Mexican American over Mexican actors because with the former there would be “no accents.”)56 In casting the lead roles, Biberman had first turned to fellow blacklisted artists like his own wife, Academy Award–winning actress Gale Sondergaard. But shortly into the casting process the producers “were jolted by recognition of a primary obligation.” As Biberman recounted it, “We had thought of ourselves as ‘the blacklisted.’ And we were the veriest newcomers. Culturally and socially, as well as politically and economically, vast numbers of our American people had been blacklisted for centuries. Had they not been, we might never have been. Were we, the new blacklisted, to blacklist the older ones?”57 IPC decided that Sondergaard would not play Esperanza. In this instance we can see how political beliefs about equality can be deepened—and made concrete, as in casting decisions—by the flash of recognition of oneself in another’s situation, or of another in one’s own situation. The blacklist had been a dramatic episode with a clear beginning, the 1947 HUAC hearings. Realizing that blacklisting in a wider sense, with no discrete event to mark its inception, happened to “vast numbers” of Americans, and that this broader form of exclusion was something they had all nominally opposed without connecting it to themselves, pushed Jarrico, Wilson, and Biberman to change their approach. “The first humiliating recognition of our discriminatory inheritance,” Biberman related in his memoirs, “was sufficient. We knew what we had to do.”58

And that was to engage Rosaura Revueltas, a respected Mexican actress, to play Esperanza. Revueltas’s mother came from a mining family in northern Mexico, and in Mexico City, where Rosaura’s father owned a small shop, the family became prominent in the arts and in left-wing politics. One brother had been a composer, another a painter, a third a novelist and well-known Communist.59 Revueltas herself had appeared in only a few films, but she had won European and Mexican awards for those performances. Biberman described her as “beautiful for this role, sensitive, earthy and not Hollywoodesque in her beauty which is deeper and richer.”60

And until the last weeks before the shooting began, a Mexican actor (never named in Biberman’s letters or later memoir but identified by Deborah Rosenfelt as Rodolfo Acosta) was to have played Ramón. Acosta had “played some twenty-six pictures in Mexico, [was] a Mexican Academy Award winner, and [had] played some nine pictures for the studios in Hollywood.”61 He had been waiting all his life, he told Biberman, to play such a role. It would permit him “to express his national pride, his love of a character such as Ramon, the heroic struggles of his own people.”62 (This flowery language was Biberman’s, not necessarily Acosta’s.) In casting, then, IPC members were taking the lessons from the Scottsboro film project to heart. People of Mexican descent needed to participate in the production, not simply to provide the material for the story.

Biberman tried to work out the relationship between authenticity and professionalism. It was important to him to have Mexican Americans perform in Salt of the Earth, and for some of them to be professional actors. But the casting process elicited two challenges to his vision. The first concerned working on a project that deliberately challenged the dominant McCarthyism; the second inhered in the complicated process of uniting workers and artists. Simply lining up professional actors and actresses proved difficult, and finding them in the United States proved impossible. No Mexican American actors accepted the roles. Having only recently, and barely, made inroads into the studios, they understood that performing in Salt of the Earth would end their careers. Rodolfo Acosta changed his mind by the time Biberman was ready to move operations to the Silver City area.63 “His agent,” Biberman recalled, “had warned him against any association with us. It would sound the death-knell for his Hollywood career.”64 In the end, Biberman failed to find a satisfactory Mexican American professional actor to play Ramón.

Sonja Dahl and Rosaura Revueltas used this crisis, which erupted just days before shooting was to begin, as an opening for an actor whom Biberman had wholeheartedly dismissed: Kennecott employee Juan Chacón. Chacón was born and raised on a small ranch in the Mimbres Valley. During World War II, he worked as a welder in California and Hawaii shipyards, but after the war he decided to return to Grant County. Despite his training and experience, Kennecott hired him as a laborer. He quickly became active in the union and even ran for political office in 1948. By the time of the film production, Chacón was a Local 890 officer.65 Chacón had been active in the Mine-Mill union since his return from defense industries in California and Hawaii after World War II. Dahl had met him in one of her early visits to Grant County to look for shooting sites and “felt that this man exuded a certain kind of posture in that cold union set-up, that . . . was very sympathetic.” Chacón, she commented later, “commanded respect. . . . He [was] a very simple man. But there was a quality of dignity about him . . . that really impressed” her.66 Revueltas, too, believed that Chacón could fill the role.

But Biberman deemed Chacón “much too shy, too small in stature, too sweet and retiring for Ramón.”67 He eventually agreed, however, to let the two women choose between Chacón and another auditioner. Dahl and Revueltas “were delighted when Herbert finally deigned to listen to [them], after [they] pushed and pushed him.”68 And despite what Biberman considered an “utterly pedestrian” reading, Chacón got the part.69 Just as Michael Wilson responded both to Hollywood women and to local women in developing the story in Salt, so too did Herbert Biberman accept the interference by two women into what he had most emphatically deemed the director’s prerogative. “I had been casting all my adult life,” he commented. “There were certain attributes for a role!”70

Biberman worked closely with Chacón to make the best of what he thought was a dismal situation. He told Chacón to spend several hours on the top of a nearby mountain, remembering

everything that has taken place in the valleys below you for three hundred years. . . . Not just remember it in your brain, but see it in your eyes. And everything you see I’d like you to feel yourself in the middle of. . . . And as you stand there, seeing yourself, seeing this country, seeing its history, seeing its struggles, seeing its strength and promise, I want you to talk back at it, and with words, spoken by your eyes. . . . If you do this you’ll come back tomorrow no longer John Chacon. Not even Ramon. But the vital spark of the people of this valley out of which we will make Ramon.71

This kind of focus reflected Biberman’s ideas—deeply romantic, to say the least—on how to draw out the essence of “the people.”72 Chacón had his own take on the process: “Herbert Biberman handed me the script, and he said, ‘Here, take this. Go up to the hills and talk to those rocks up there, and learn it.’ So I went up there, and I opened the script, and I started reading it. And I started looking at the rocks and reading the script. And I said, ‘Well, I’ll be darned. Here I am, an actor in Salt of the Earth. Trying to learn a script.’ So, I went ahead, and I went up there several times. I looked at those rocks, and I kept on reading and reading the script. So finally, we started filming Salt of the Earth. And it didn’t take me very long to learn the script.”73

Romanticism inflected Wilson’s and Biberman’s ideas for Salt. Both men referred to “the people” without any direct or personal connection to them; in this respect, Biberman and Wilson resembled many writers on the Left who casually or effusively spoke of “the people” as a group that possessed singleness of purpose and for whom these writers claimed to speak. An outsider status, they thought, could help artists “enter into [the people’s] lives [and] inspire them into resistance—into refusing to make the little day by day concessions of their decency.”74 Wilson was very attentive to the union families’ own words and the texture of their lives: he did not apply preconceived ideas of how an oppressed minority feels or how it should act. But the very project of distilling an essence speaks of an illusory homogeneity, the imagination of which may have resulted, in part, from seeing Mexican Americans as exotic. Wilson essentialized Mexican Americans and workers, but on that basis he also deferred to them. In the context of producing a script, he attempted to integrate their understanding of their history with his ability to write a story.

Biberman went down the same path when he tried to capture the

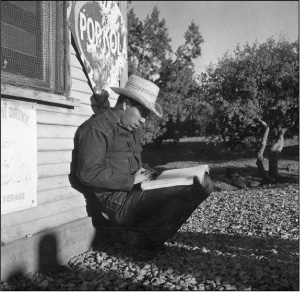

Juan Chacón studying the script of Salt of the Earth. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lot #A108.

essence of the people through art. He described his reaction to meeting the miners and their families: they were “such a beautiful group of people . . . that well photographed they will just knock people out of their seats with their strong and clean and incredibly attractive character.”75 Like Wilson, Biberman essentialized Mexican Americans and workers, but rather than deferring to them on this basis he confined them to his own vision of a worker-artist alliance in which nonprofessionals stayed in their place. Romanticism had a flip side in this case: condescension perceptible in some of Biberman’s (and, to a lesser extent, Wilson’s) comments about Mexican Americans. Biberman and Wilson respected the Mexican American community in Bayard; at the same time, they exalted or romanticized that community, finding in it an essence that obfuscated differences among its members. Mexican American working families in Grant County challenged Wilson and Biberman from a position of “authenticity.” Wilson was already inclined to accept this, but Biberman could not, and did not, entirely do so.76

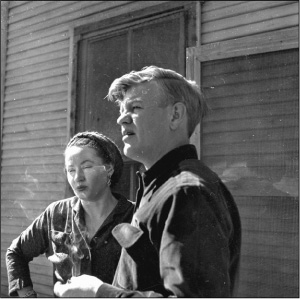

Virginia and Clinton Jencks on the set of Salt of the Earth. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lot #A108.

Casting the lead female character brought out this problem of authenticity. Union members in Grant County saw no reason why professional actors should play the lead roles. Intimidated, perhaps, by the “high society” that IPC seemed to represent, Local 890 families also wanted to protect their own story and feared that professional actors might compromise it. Virginia Chacón, for instance, said “We just didn’t want a movie made and let somebody else come and take our places, you know.”77 Many a female picketer, in fact, probably thought the character Esperanza was modeled on herself.78 This feeling grew even stronger once Herbert Biberman cast Juan Chacón as Ramón. Union members—women particularly, but supported by the men and by union officials like Clinton Jencks—then saw even less reason to bring in an outsider to play the female lead. Angie Sánchez, who played Consuelo Ruiz, later stated that Biberman had originally slated her to play Esperanza.79 Biberman had stopped in Bayard early in July 1952 to begin screening local people for roles. He wrote to Travis that he had “discovered a wonderful and natural-born actress in Bayard who has lifted my hopes considerably,” but he neither identified her nor indicated that she might play Esperanza.80

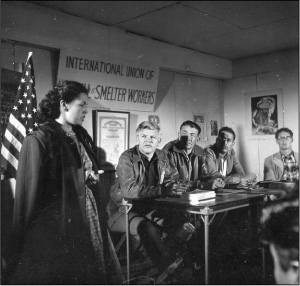

Angie Sánchez as Consuelo Ruiz, offering the ladies auxiliary’s help to the striking Delaware Zinc miners. Sitting next to her are Clinton Jencks as Frank Barnes, Joe T. Morales as Sal Ruiz, and Ernesto Velásquez as Charley Vidal. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lot #A108.

The final cast featured nine 890 members—most having been in leadership positions in the union and auxiliary—in leading roles. Juan Chacón played Ramón. Clinton and Virginia Jencks played organizer

Henrietta Williams as Teresa Vidal, proposing that women take over the picket lines. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lot #A108.

Frank Barnes and his wife, Ruth. Joe T. Morales, long a Kennecott employee and 890 leader, played Sal Ruiz, with Angie Sánchez playing his wife, Consuelo. Henrietta Williams, who had been jailed during the Empire Zinc strike, played Teresa Vidal, and Ernesto Velásquez, the chairman of the Empire Zinc strike negotiating committee, played her husband, Charley. And rounding out the nonprofessional cast in prominent roles were Clorinda Alderette and Charles Coleman as Luz and Antonio Morales. Casting the scabs and deputies proved difficult; eventually two brothers, E. A. and William Rockwell, agreed to take on the odious role of the sheriff’s deputies, but only after Biberman demonstrated that the violent scenes involved fake blows: neither wanted to hit a union brother.81 Some blacklisted professional actors played minor roles. Will Geer, who would later gain fame as Grandpa Walton on television, played the sheriff, and David Wolfe played the company’s representative.

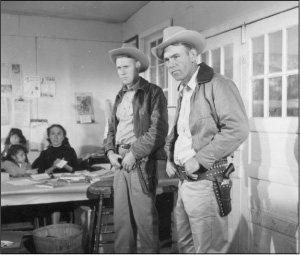

E. A. and William Rockwell as the sheriff’s deputies, delivering the court injunction to the union hall. Director Herbert Biberman had trouble casting the deputies, because no one wanted to hit a union brother. Only after showing the Rockwell brothers that the punches were fake did Biberman persuade them to accept the roles. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lot #A108.

The Gender Politics of IPC

Interestingly, lessons from the Scottsboro project did not perceptibly shape the gender politics within IPC. Sylvia Jarrico and Sonja Dahl Biberman both worked on the production of Salt, but they were not afforded the same kind of formal recognition as women in a film on the Woman Question that Carlton Moss and Frances Williams received as African Americans in projects on the Negro Question. Rosaura Revueltas did not join IPC’s production company but did join its distribution company. Biberman referred to his sister-in-law as the “secretary of our company,” instead of the assistant producer that she really was. Sonja Dahl Biberman first scouted out the county for possible locations and housing in December 1952.82 She was trusted enough, and in sufficient contact with the set and crew, to be one of two signatories on the IPC bank account in Silver City.83 She worked on the set as “script girl” and on whatever else needed to be done, alternating jobs with other crew members.84 Later she was critical to the film’s distribution. Historians Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund refer to Sylvia Jarrico as an associate producer; and, although the film credits do not list her, she certainly was on the set throughout shooting and, according to Biberman, very popular among the union families. She had walked the picket with union women when the Jarricos first visited the strike late in 1951. Clearly she had plenty to say and plenty to offer.

In IPC’s film projects, as in CP thinking in general, there were obvious parallels between the treatment of African Americans and that of women. The first IPC project was a film about African Americans and racism, while the second addressed women and sexism. Furthermore, Communists and people in IPC used similar language to discuss the two issues: “the Negro Question” and “the Woman Question,” “white chauvinism” and “male chauvinism.” But these linguistic similarities did not carry over into concrete applications of theory on race and gender; the women’s issues did not resonate in the same way with the leaders of IPC and did not, evidently, require the same formal attention to the place of women within the organization.

Here we witness a blindness regarding women’s contributions that was characteristic of mixed-gender political and business organizations. This may have come from Sylvia Jarrico and Sonja Dahl Biberman having been family members of the principal players in IPC. To some degree, women were subsumed into the project as wives and sisters. This subsumption may be related to the romanticism regarding “the people” being represented: assumptions of a unity, a wholeness, obscured any divisions among its components. This is ironic given Wilson’s own enthralled attention to the complex layers of struggle; still, it is not much of a surprise that in some instances there would be a neglect of that complexity in favor of a simpler whole, particularly when the complexity was in their own families and company.

This analysis is not meant to accuse IPC members of myopia or of acting at odds with the implications—implications that we perceive fifty years later—of their egalitarian beliefs. Instead of passing judgment, we should understand these issues as giving fuller shape to their political thought as they developed it in their personal lives and in collective endeavor, and seek to understand the reasons that their ideas and actions on gender and Mexican American ethnicity lagged behind their ideas on African Americans and racism. Even to discuss “lagging behind” is to apply standards that they may or may not have held. Still, Communists possessed enough theoretical commitment to women’s equality and to Mexican American social advancement that those standards were indeed relevant.

The Production Committee

Once the project moved to Grant County in early January 1953, a production committee, consisting of six representatives each from IPC, Local 890, and Auxiliary 209, managed the daily work. The appointment of representatives from Local 890 and Auxiliary 209 in equal numbers hints at women’s assertions of equal representation in putting their story on film; the structure affirmed that they could not be subsumed in the general category of “union members” but rather warranted their own standing. And with IPC in the minority on the production committee, the filmmakers were in no position to trump the decisions of the union families if the union representatives were united on a particular question. Although Mine-Mill’s international executive board had agreed in the summer of 1952 to sponsor the picture (without contributing money), the international occupied no formal position on the production committee. Morris Wright, editor of Mine-Mill’s national newspaper, served as public relations representative.85

Production involved many tasks: getting crew and cast to the film location, building sets, gathering props, coordinating the crowds for group scenes, feeding and housing everyone, scheduling the shooting to accommodate men and women who also had regular jobs. To assistant director Jules Schwerin, the ladies’ auxiliary deserved most of the credit for these logistics.86 He was also quite moved by “the relationship developing between the crew and the miners.” It was “a wonderful thing to watch,” he said, “a real spirit of brotherhood, each group learning from the other. . . . Every day more miners pitch in to help the crew, some of them after a grueling eight-hour day in the mines. Our construction team can take pride in the fact that the miners find our mine-head set authentic.”87

Sonja Dahl Biberman made sure that the production committee also arranged adequate child care to allow women to participate, both behind and in front of the camera. Some women had tried individual solutions to the problem of child care. Anita Torrez, for instance, persuaded her younger sister to come to Hanover to take care of the Torrezes’ infant while Anita helped with production. But the problem posed by inadequate child care was of such great dimension that it required a collective solution. The mass scenes, in particular, were difficult to arrange and caused many changes in the production schedule. Herbert Biberman knew that the production would require “women, and child care,” but he did nothing to arrange it; the men in Local 890 had overlooked the issue entirely.88 It took Sonja Dahl Biberman’s persistence to make men recognize babysitting as a legitimate concern of the filmmakers. “Most of the families have no phones and distances are fantastic,” Schwerin noted. “Organizing a baby-sitting-and-jitney service for a hundred people is really something. . . . We are all impressed by the stamina and courage of the women and the relaxed nature of their children.”89

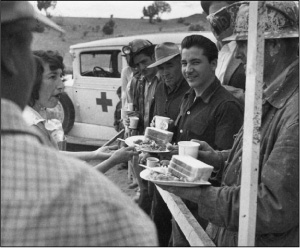

Meals on the set were provided by the production committee, composed equally of representatives from IPC, Local 890, and Auxiliary 209. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lot #A108.

The production committee was responsible for more than the day-to-day logistics. It was, as Juan Chacón explained, also “a policy-making body, with the responsibility of seeing that our picture ran true to life from start to finish. Occasionally there were meetings in which the union people pointed out to our Hollywood friends that a scene we had just shot was not true in certain details. When that happened we all pitched in to correct the mistake. Most of these mistakes were made because the movie craftsmen had not lived through all our struggles; but they had all the heart and the good will in the world.”90 Clinton Jencks corroborated Chacón’s account but emphasized conflict within the committee: “This wasn’t all easy. There were people who came in, making the film, [who] had very strong ideas about how the film should be made. . . . We’d have arguments. . . . We’d be working hard all day, . . . and we’d have meetings until late at night, hammering out problems for the next day.” Still, this conflict was productive because no one group could dominate. As Jencks put it, “It was a beautiful kind of process of interchange.”91

The struggles within the production committee show how important it was to the mining families that the story be “true.” This truth consisted not only of the fidelity of particular details to the events they portrayed but also of an ownership of both the strike and its representation. Making the strike into a movie was a transformative process. The movie was not, and could never be, the same thing as the strike, and the artistic distance between the two was necessary if the participants were either to process the events of the strike in an emotionally satisfying way or to share their story with audiences near and far. But the union families wanted to ensure that the transformation of their story would not also be an expropriation of their story.

Acting and Reenacting

Scenes before the camera felt real to the Grant Countians who performed them, and the casting process brought this out into the open: couples hesitated to play the spouses of other men and women; the Rockwell brothers did not want to play deputies because they were afraid of hurting a union brother. The experience of actually shooting the scenes, too, shortened the distance between acting and reenacting, while reliving the events provided some of the amateur actors with emotional release. For others, however, closeness to the real events made filming the scenes traumatic.

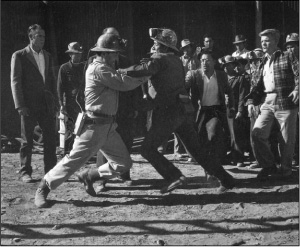

In one early scene, after an accident that precipitates the strike, Ramón assaults a foreman who calls him “Pancho” and a “liar, a no-good,

The lines between acting and reenacting were often blurred. Here, Ramón assaults the foreman, with Charley Vidal and Frank Barnes trying to restrain him. Chacón acted with such intensity—Jencks was kicked in the shin in the process—that Jencks was convinced this scene was a catharsis for pent-up anger toward managers. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lot #A108.

dirty—.” This was the first scene shot with dialogue, and, as assistant director Jules Schwerin noted in his diary, “Everyone was tense. One miner kept muffing his lines. He apologized, explaining that the actor-foreman reminded him of a real foreman he had known, and added: ‘He gets me so damn mad I forget my lines.’ If we can sustain this kind of reality, a few muffed lines won’t matter.”92 For Juan Chacón, acting in this scene proved to be something of a catharsis for years of pent-up resentment at racist management. He tore into the actor playing the foreman with such force that Clinton Jencks and Ernesto Velásquez could barely restrain him; Jencks got a bruised shin in the deal. “He didn’t pull all that anger out of the sky,” Jencks commented.93 Chacón later said, “One of the most surprising things to us was that we found we didn’t have to ‘act.’ El Biberman, as we came to call him, was happiest when we were just ourselves. So after awhile, we stopped pretending and then, from the ‘rushes’ we saw, the movie began to look better.”94 Clinton Jencks felt that the movie was “so close to the time [of the strike]. It was a part of us. . . . I wouldn’t even know the camera [was there].”95

The union families, like Biberman, were trying to distill an essence—not of “a people,” necessarily, but of the meanings of the strike for them, their families, and their union community. By reenacting their experience they reordered it. Putting on the mask of a theatrical role allowed them to articulate what felt to them to be central truths and, they hoped, to reach and engage audiences everywhere. Watching the first “rushes” on January 29, 1953, the union people “howled and cheered and laughed . . . when they saw themselves on the screen. . . . It was a catharsis.”96

Not everyone welcomed the chance to relive the strike experience, however. Willie Andazola, a child who had been jailed with his mother, Camerina Andazola, after the mass arrests of June 16, 1951, did not want to play any role in the picture and only did so unwillingly. The jail had scared him very deeply, and he had nightmares about the bars.97 And Rachel Juárez, who had been struck by a car on the picket line, never saw the film: even fifty years later, the prospect of seeing fellow picketers like Consuelo Martínez wounded by strikebreakers and deputies on screen was too traumatic for her.98

What Making Salt of the Earth Meant to the Participants

The blacklist devastated progressives in Hollywood, but it also opened the space for trying a new kind of artistic project. Going into the project, the Jarricos, Biberman, and Wilson were excited at the prospects of crafting a worker-artist alliance; coming out of it, they were transformed. Biberman made the fight to distribute the movie into a lifelong battle, suing Hollywood studios for conspiring to block the movie’s distribution and working strenuously to get the movie shown in countries around the globe. Sylvia Jarrico found that working on Salt of the Earth “refurbished [her] sense of political usefulness.”99 And for Michael Wilson, who would go on to write even more widely acclaimed screenplays, writing Salt of the Earth was the most important thing he had ever done.100

The worker-artist alliance appealed to technicians as much as to writers, directors, and actors. A veteran of the battles against racketeering in the International Association of Theater and Stage Employees, technician Paul Perlin was blacklisted after the big Hollywood studio strikes of 1945 and 1946. HUAC subpoenaed him in November 1951, but Perlin was not intimidated—he “gave the committee a rough time.” He was thrilled to work on Salt of the Earth because it was the first movie where he was encouraged to “cross the bridge between craft and talent crews”; gone was the “jungle-like competition” that compromised Hollywood productions.101 Similarly, prop maker Irving Hentschel was proud to have been hired to work on Salt, seeing it as his reward for years of union activity. “Pictures in Hollywood had all the guts taken out of them,” Hentschel observed, but the people in Grant County made an unabashedly pro-union movie.102

Willie Andazola (left) as a striker’s son. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lot #A108.

Making this movie was also a way to rekindle women’s activism, which dwindled after the strike ended in January 1952. For example, the auxiliary had planned to start a nursery that would, as the union newspaper

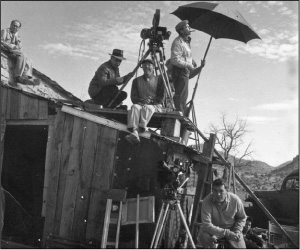

Filming Salt of the Earth. Paul Jarrico is on roof at far left, Herbert Biberman is seated on the roof beneath the camera, and Michael Wilson is seated on the ground at right. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Lot #A108.

put it, “[benefit] our women who have been tied up and are having trouble in preparing care.”103 But the nursery plan fell through. While “the men are still fighting together, daily on the job,” Virginia Jencks observed in March 1952, “the women who showed courage and determination seem almost like by-products of the strike now that it is over.” Salt of the Earth would give picketers “recognition and a feeling of accomplishment and personal pride,” she explained. “In socialist countries there are many ways of showing how a person is a public hero, but here we have let this historical strike and these historic people fade away.”104 Jencks understood that part of the trouble was women’s isolation as housewives, but she was especially frustrated with the international leadership and its failure to take women’s situation seriously. According to Jencks, a speaker sent to lead a workers’ education class for women in February 1952 “said nothing to us as women, or for us, and although there were sixteen women there, they were not involved in the discussion in any way. I’m still sore about the way this progressive guy never spoke about women in his discussions. . . . I’m losing objectivity. Clint tells me I’m a man-hater. Lately, I’m damned sure he’s right.”105 As historian James Lorence suggests, Wilson’s script was able to affirm women’s activism in a way that transformed the actual outcome of the strike into a longer-lasting and more positive lesson in solidarity than what the strikers could have achieved.106

Perhaps most importantly, and most simply, the union participants wanted to get their story out, and Salt of the Earth promised to help them do so. Henrietta Williams could hardly believe that so much ugliness could be unleashed during the Empire Zinc strike against working people just trying to improve their lives. Making the movie, she said, was a way to show people “one of the worst things that could happen here in the United States.”107 But this was not in order to discredit the United States in the eyes of a hostile world, as Salt’s anticommunist enemies would insist. Instead, it was to affirm the dignity and the humanity of the strikers. To Williams, the title, Salt of the Earth, meant “the sweat of the miner, and the ground of the mines”—powerful images of working-class strength and the force of nature.108 Clinton Jencks saw in the movie a chance to affirm the heroism of ordinary people and to make connections with audiences. Making Salt was a high point in their lives precisely because, as he put it, “we were reaching out, and we were making ourselves naked in all our weaknesses, and our strengths. And we weren’t trying to cover up the problems. But we also wanted to say we’ve learned how to overcome some of those problems. . . . And we found people that were willing to help us say it. And that was beautiful.”109 Juan Chacón believed that Salt of the Earth “help[ed] to expose the lie” that Mexicans were “naturally inferior,” a lie told by the mining companies to prevent Anglo-Mexican unity.110 For all of these participants, the essence of making the movie was making connections to others, just as Biberman had described. Salt of the Earth brought workers and artists together and had the potential to connect both groups to American audiences more broadly. It was this challenge to the isolation imposed by the blacklist and by anticommunism more broadly that most threatened the mining industry and the film industry. And it was the potential to bring people together that, ironically, allowed both the mining industry and the film industry to unite in order to stifle Salt of the Earth.