CHAPTER 8

The Native Americans

All of the numerous voyages to America by Englishmen during the three-quarters of a century following John Cabot’s 1497 expedition to Newfoundland were but prelude to the establishment of the first English settlement in America, on Roanoke Island, in 1585.

This was the beginning of residency by Englishmen in what was to become the United States, the first time that subjects of the British crown lived for an extended period on the North American mainland. Yet few Americans have ever heard of the Ralph Lane settlement, for it is seldom mentioned in texts used in the study and teaching of American history.

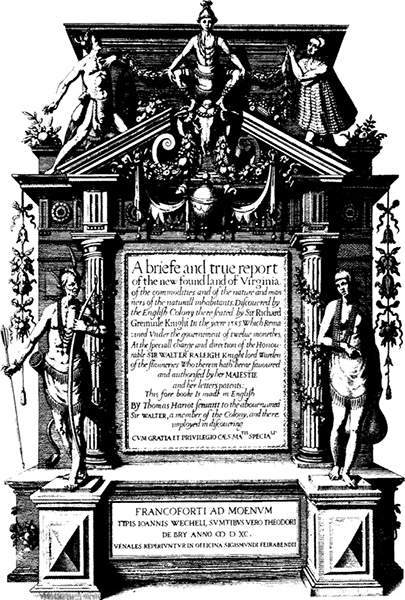

The documentation is readily available and, with one exception, has been available for nearly four hundred years. It is found in five different sources, which frequently corroborate or expand on each other: (1) the accounts of Grenville’s 1585 voyage to Roanoke Island with Lane and his colonists; (2) an extensive report on the settlement, written by Lane, its governor; (3) the drawings John White made during his stay of approximately one year in Virginia, long thought to have been lost, but later rediscovered; (4) Thomas Hariot’s Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, a fascinating book first published in 1588; and (5) Theodor de Bry’s engravings for the 1590 edition of Hariot’s Briefe and True Report, which were based on White’s drawings. All of these except White’s drawings and de Bry’s engravings have been printed in various editions of Hakluyt’s Principall Navigations.

FIGURE 7. Title page from Thomas Hariot’s Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia.

It was not by chance that the complement of England’s first American colony included two such highly qualified specialists as White the artist and Hariot the scientist, for Raleigh had planned it so. And he must have been pleased with the result, for there emerged from this joint effort the first clear picture of the native American Indians. From it we know not only of their appearance but of how they lived and worshiped, and the way they harvested their crops, and built their boats, and fished, and hunted, and warred.

Thomas Hariot (the tendency now is to spell the name “Harriot,” though it appears with only one r on the title page of his most famous work) was the younger member of the team, twenty-five-years old in 1585, and already an important figure in Raleigh’s household, where he served as a tutor in science and mathematics. Paul Hulton, a leading authority on White’s drawings and Hariot’s Briefe and True Report, is of the opinion that Hariot’s scientific knowledge, and especially his understanding of navigation, probably “acted as a stimulus to Raleigh’s concern with overseas exploration.” Hariot is known to have provided navigational instructions for Amadas and Barlowe, to have made astronomical observations on the 1585 voyage, and to have kept extensive scientific records of what he saw in America. In addition, he has since been recognized as the founder of the English school of algebra, as the designer and builder of one of the earliest telescopes, and as the discoverer of the law of refraction, or bending of light.

Hariot’s greatest contribution to Raleigh’s colonization efforts, however, may have been in an entirely different field—that of linguistics. He was possibly the first Englishman to learn to speak and understand the language of the native residents of North America. Modern historians speculate that Manteo and Wanchese, the two Indians who returned to England with Amadas and Barlowe in the fall of 1584 and spent the winter there, were housed at Raleigh’s estate, and that Hariot was assigned the task of learning to converse with them. Besides teaching them basic English, this would have involved his acquiring a working knowledge of their native tongue. Thus, when Hariot finally arrived on Roanoke Island in the summer of 1585, he could well have been prepared, as no other Englishman had been before him, to gain a full understanding of what Indian life was really like.

For all of his diverse talents, Hariot might best have been a clergyman, for throughout his writings he places emphasis on the religious beliefs of the Indians and on his own efforts to convert them to Christianity. “Manie times and in every towne where I came,” he wrote, “I made declaration of the contentes of the Bible; that therein was set foorth the true and onelie GOD, and his mightie woorkes” and the “true doctrine of salvation through Christ.” Ironically, he was later to be labeled an atheist, but on Roanoke Island he seemed almost obsessed with spreading the gospel.

Hariot soon learned, and in fact probably had already learned from Manteo and Wanchese in England, that the Indians had a religion of their own, one in which some beliefs were not too different from those of Protestants. “Although it be farre from the truth,” Hariot said of the Algonkian religion, “there is hope it may bee the easier and sooner reformed.”

The foundation of the Indian religion was that there was “one onely chiefe and great God, which hath bene from all eternitie.” When this chief and great God decided to create the world, he found it necessary to make petty gods, one in the form of the sun, another the moon, and still others the stars. He created the water next, then delegated to the lesser gods the task of creating the great “diversitie of creatures” that were to inhabit the earth. As for mankind: “They say a woman was made first, which by the working of one of the goddes, conceived and brought foorth children.”

The Indians represented all of their gods “by images in the formes of men, which they call Kewasowak,” with a single such idol called a Kewas. Hariot said the Kewasowak were housed in special buildings, or temples, where the Indians worshiped, sang, and made “manie times offering unto them.” Some of the temples housed only a single Kewas, while others had two or three. White pictured one Kewas, a life-sized figure, fully clothed, and wearing a broad-brimmed conical hat, sitting on a platform in a burial tomb and guarding the mummified remains of deceased chieftains. One of the larger temples, shown in an engraving of the White drawing of the town of Pomeiooc, was a circular structure with a pagodalike roof covered with mats made of animal skins.

According to Hariot’s report the Indians had their own heaven and hell, and believed strongly in “the immortalitie of the soule.” Following death, and “as soone as the soule is departed from the bodie,” he said, it is carried either to heaven “the habitacle of the gods, there to enjoy perpetuall blisse and happinesse” or to “a great pitte or hole,” located in the furthest part of the world toward the sun, “there to burne continually.” Their name for this place of perpetual residence for the wicked was Popogusso, and in life they tried their best to conduct themselves in a manner that would preclude the possibility of ending up there.

The Indian sought guidance and protection from his gods in almost every conceivable circumstance, from birth to death, and even after. He prayed, danced, and shook his rattles in an effort to pacify his gods before going into battle, during battle, and even after the battle was over. He sought godly sanction when going hunting or fishing, or just out for a ride in his canoe; and he invariably turned to prayer when threatened by storm or devastated by drought and when ill, injured, or just feeble from the infirmities of age. He was in truth, by his own precepts, a devout disciple of his gods.

The appearance of the strangely garbed, white-skinned men in their huge winged craft, the sound and devastation wrought by their weapons, and numerous evidences of their seemingly mystical powers caused some to think that these beings might themselves be gods, direct representatives of their own great and only Kewas, the biblical father of Christ. Hariot was to learn later just how much bearing these thoughts would have on his own missionary work.

It was common practice for the Indians to accompany their prayers by offering sacrifices to their gods, and they carried with them for this purpose on all of their travels and adventures small pouches filled with the crushed and powdered dry leaves of a plant they called uppowoc. Hariot said uppowoc was held in such “precious estimation amongest them,” that they thought their gods were “marvelously delighted therwith” and so offered it to them often. During religious ceremonies they would build large fires, paying special tribute to the gods by casting uppowoc on the flames. Whenever a new fishing weir was set they scattered the powdered leaves about to bring good luck. And only a foolhardy Indian would have considered venturing very far from shore in his canoe without carrying with him a packet of uppowoc, to be cast into the air and spread upon the waters when a storm arose. Hariot said the offering was often accompanied by unusual gestures, stamping, dancing and clapping. Those caught up in the religious fervor, he added, would hold up their hands and stare into the heavens, all the while “chattering strange words & noises.”

They grew uppowoc in carefully tended plots near their houses and dried it in a time-consuming curing process, before cutting or crushing it into smaller particles. The Indians had yet another use for the cured uppowoc: as described by Hariot, they “take the fume or smoke thereof by sucking it thorough pipes made of claie, into their stomacke and heade: from whence it purgeth superfluous fleame & other grosse humours, openeth all the pores & passages of the body.” This marvelous substance, medicine both to the body and to the soul, was grown also in certain parts of the West Indies, according to Hariot, with “divers names,” though “The Spaniardes generally call it Tobacco.”

The Algonkian Indians living in the Roanoke Island area grew other crops in addition to uppowoc, for they were, basically, an agricultural people. Maize, or corn, was a staple of their diet and the one crop without which they would have had difficulty surviving. Hariot said some of the Indian farmers “have two harvests, as we have heard, out of one and the same ground.” This statement was probably closer to the truth than Barlowe’s report, a year earlier, that the corn “groweth three times in five moneths: in Maye they sowe, in July they reape, in June they sowe, in August they reape: in July they sowe, in September they reape,” though in his Secotan drawing White shows corn in three stages of growth.

Hariot left a detailed description of how the Indians planted, tended, and harvested their corn. “The ground they never fatten with mucke, dounge, or any other thing,” he said, nor do they “plow nor digge it as we in England.” Instead, a few days before the time for sowing, the men and women would take to the fields together, breaking only enough of the surface soil to remove weeds, grass, and old corn stubs. The men, walking between the rows, used hoelike wooden instruments with long handles. The women, accustomed to working while squatting or sitting, used much shorter tools, which Hariot described as “peckers or parers.” As soon as the weeds and stubble had dried for a few days, all of the material was scraped up into small piles and burned. “And this,” Hariot added, “is all the husbanding of their ground that they use.”

When the time came for planting, Hariot continued, “beginning in one corner of the plot, with a pecker they make a hole, wherein they put foure grains.” It was a meticulous operation: they carefully spaced the grains of seed corn about an inch apart before covering them with rich earth, or “moulde,” to form small hills. Then they left approximately a yard of open ground between the hills, “where according to discretion here and there” they planted as many beans and peas as would grow without affecting or being affected by the taller corn. The Indians also grew a variety of roots, including potatoes, as well as melons, gourds, and several different vegetables in or near the cornfields. Even small plots of pumpkins and sunflowers are shown in the Secotan drawing.

In addition to harvesting these special crops the Algonkians took advantage of the natural bounties of the forests, picking wild fruit, berries, and nuts in season. They relied heavily on the meat of wild animals and fowl and on fish for their food, and the Indian men spent much of their time hunting and fishing, combining sport with the quest for food. Lacking conventional tools, they employed a high degree of ingenuity in devising methods for catching or killing fish and game.

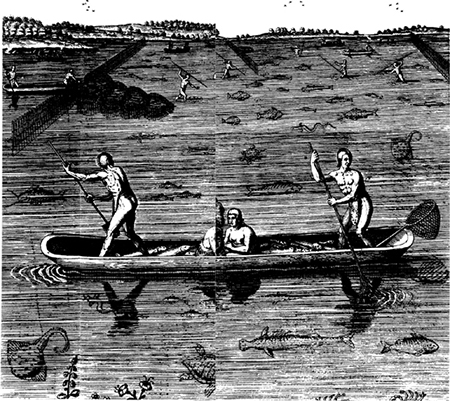

The Europeans were especially impressed with their fishing techniques, which proved much more effective in the shallow sounds surrounding Roanoke Island than those employed by the colonists. For the most part the Indians caught their fish in netlike obstructions called weirs, which they placed across streams or channels, much as modern pound-netters do to catch the seasonal runs of striped bass and shad. The weirs were made of reeds, woven or tied together and anchored to the bottom by poles stuck into the sand. With their tops extending above the surface of the water the weirs looked much like fences. They were arranged in varied patterns designed to catch the fish and then impound them.

Hariot added that yet another fishing technique “which is more strange, is with poles made sharpe at one ende, by shooting them into the fish after the maner as Irishmen cast dartes.” The spears or harpoons used in this operation were fitted with sharp points, some of them made from the hollow tail of what Hariot described as “a certaine fishe like to a sea crabbe.” The Indians were adept at spearing fish, whether wading in shallow waters or fishing from their canoes, and apparently they fished at night as well as in the daytime, probably using torches of lightwood knots both for illumination and as a means of attracting fish to the surface.

The Englishmen reported that the Indians caught a wide variety of fish, ranging from trout, mullet, and flounder to giant rays and porpoise. Hariot added that there were “many other sortes of excellent good fish, which we have taken & eaten, whose names I know not but in the countrey language,” some of which are pictured by White in his watercolors. In the months of February, March, April, and May, Hariot added, there were large quantities of sturgeon and herring, some of the latter ranging up to “two foote in length and better.”

As was the case with most other American Indians, the natives of the Albemarle and Pamlico Sound regions relied to a great degree on bows and arrows for hunting. Hariot made special mention of black bears, which he said were “good meat,” and he described how the Indians would chase the bears until they sought safety by climbing a tree, “whence with arrowes they are shot downe starke dead.” Hunting the fleet-footed deer with bow and arrow called for different skills, but the Indians had devised a special technique there as well, and one involving a high degree of cunning and patience. After foraging for food, the deer would often seek protection in areas covered by high reeds and underbrush, where they could sleep in relative security. But the crafty Indians, having observed the habits of the deer, would hide in the reeds for hours, waiting for their quarry to return so they could shoot them at close range.

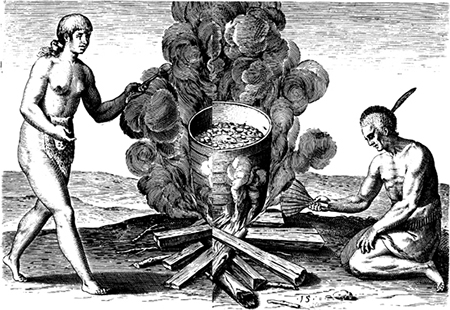

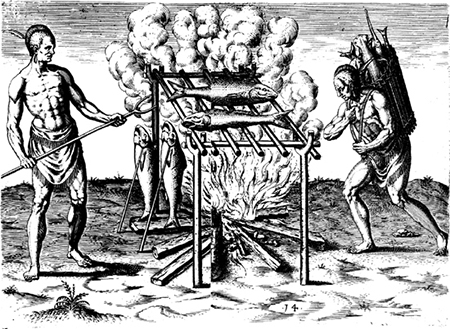

The wide assortment of food items available to the Indians called for varied methods of preparation and preservation. Most of the fruit and nuts and some of the vegetables were eaten raw, but the meat and fish and other foods had to be cooked before being consumed. They did their cooking outside over open fires, since they had no flues or chimneys in their houses. Most of the cooking was done in handmade, round-bottomed earthen pots resting on small mounds of dirt, with carefully tended fires underneath. In this way they boiled or stewed a wide variety of native foods including meat, fish, fruit, nuts, roots, and such vegetables as corn, potatoes, beans, and peas. They also broiled certain items, including fish and meat. In one of his drawings White pictures fish laid out on an elevated grill made of reeds, the grill in turn supported and kept away from the flame by four large stakes driven into the ground. Dried and smoked meat and fish were preserved along with corn and certain roots and nuts for use during the winter season. In the spring, when the reserve supply had been depleted, they went over to the seashore “to live upon shell fishe” while “their grownds be in sowing, and their corne growing.” In the process they accumulated vast mounds of shells at their favorite meeting places.

They seem to have had a wider variety of bread than the average modern American family. Usually they made their bread from corn or wheatlike grain, but sometimes, for variety, they boiled beans or peas, mashed them in a mortar, and shaped them into “loaves or lumps of dowishe bread.” They did the same with walnuts and chestnuts, pounding the meat into a great mushy meal which they served as a sort of spoonbread. They even made bread of acorns, first drying them “upon hurdles made of reeds with fire underneath,” then storing the cooked nuts until they were needed, at which time they soaked them in water and mashed them into a kind of dough.

The dishes used by the Indians were described by Barlowe as “woodden platters of sweete timber”; and wood was undoubtedly the material from which they made their ladles and spoons. Gourds, which they cultivated in their fields, served as containers for liquids.

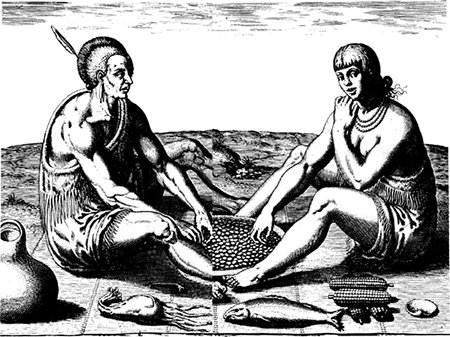

At mealtime, instead of sitting around tables, the Indians sat on large stitched or woven mats of reeds, which were spread on the ground. The men and women customarily sat facing each other with the food in large wooden plates or bowls between them, and they picked up food with their fingers. For the most part the Indians appear to have been very careful not to overeat, leading one of the colonists to describe them as “verye sober in their eatinge, and drinkinge, and consequentlye verye longe lived because they doe not oppress nature.”

The Indian houses were made of “small poles made fast at the tops in rounde forme after the maner as is used in many arbories in our gardens of England.” Normally rectangular in shape, with their length “commonly double to the breadth” and ranging from thirty-six to more than seventy feet long, the houses were usually covered with bark, although Hariot said he saw some covered with “artificiall mattes made of long rushes, from the tops of the houses downe to the ground.”

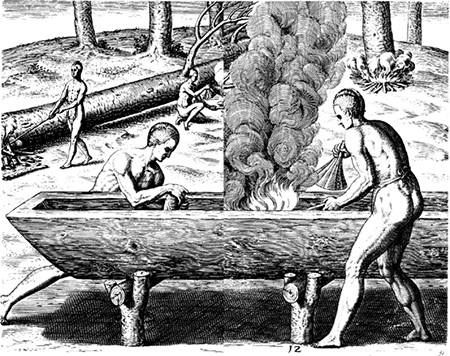

Despite their lack of tools the native Americans were expert boat builders, and both Barlowe and Hariot described their unusual technique in detail. Selecting “some great tree,” preferably one that had been blown down in a storm, they began by burning through the massive trunk to get the approximate length desired. After scraping off the bark with sharp shells, they began the laborious process of burning out the interior. This was accomplished by spreading gum or rosin “upon one side thereof,” then cutting away the coals with shells. They repeated the process time after time, first spreading and setting fire to the gum, then chipping away with the shells, until the craft finally took shape. “In this way,” Barlowe said, “they fashion very fine boats and such as will transport twenty men.”

FIGURE 8. Their manner of fishynge in Virginia. Engraving by Theodor de Bry from a drawing by John White.

FIGURE 9. Cooking in earthen pots. Engraving by Theodor de Bry from a drawing by John White.

FIGURE 10. Broiling fish. Engraving by Theodor de Bry from a drawing by John White.

FIGURE 11. Their sitting at meate. Engraving by Theodor de Bry from a drawing by John White.

FIGURE 12. The manner of makinge their boates. Engraving by Theodor de Bry from a drawing by John White.

The English chroniclers have left us with considerable detailed information on the appearance of the natives, and especially on the way they dressed. Most clothes were made of deerskin. The women pictured in White’s drawings wore apronlike skirts extending from their waists downward to above their knees, with their breasts exposed. Some of the men wore similar skirts, while others were dressed in full-length capes, either draped over the left shoulder or tied behind the neck. Most often the material was slit to form tassels, and when attending “solemne feasts” or preparing for hunting expeditions the men would sometimes attach long tails to the rears of their garments.

The conjurers, or medicine men, would “fasten a small black birde above one of their ears as a badge of their office” and carry a bag attached to a belt or rope around their waists. The priests, on the other hand, wore “a shorte clocke made of fine hares skinnes quilted with the hayre outwarde” and were further identified by having “their heare cutt like a creste, on the topps of thier heades as other doe, but the rest are cutt shorte, savinge those which growe above their foreheads in manner of a perriwigge.” All of the women shown in the drawings had their hair trimmed in bangs; most wore their hair shortly cropped on the sides, while others had longer hair hanging down in the rear or tied in a loose knot.

The Indians used cosmetics extensively, on their bodies as well as their faces, and often had permanent body markings. In most instances the women decorated their arms with either body paint or tattoos in fairly intricate designs that made them appear almost as though they were wearing armlets. Some had similar designs on their legs and equally elaborate facial makeup. Such decorations did not usually appear on the men. When visiting other villages, engaging in religious ceremonies or festivities, or preparing for battle, however, they painted their backs with distinctive symbols to identify their tribe and the individual’s status within the tribe.

Although several of the women pictured wore necklaces, the men usually outdid them, with ornaments in their ears in addition to those around their necks. Wingina and the other “cheiff Lordes” wore chains of copper “beades” or “smoothe bone” about their necks. Others strung pearls from their ears and wore bracelets of pearls on their arms “in token of authoritye, and honor.”

From these verbal descriptions by Hariot and his associates, supplemented with the detailed drawings of White, there begins to emerge a coherent picture of the life-style of the native people. They lived in neatly organized villages, sometimes in houses with several rooms. They maintained orderly and productive fields; worshiped their gods; hunted and fished when they needed to, or when the urge was overwhelming; and adhered to common sense and their own established rules of etiquette when dining. There were wars, of course, and periods of drought; and on occasion devastating hurricanes moved up from the Caribbean. But in many respects it was a nearly idyllic existence. Until, that is, the civilized Englishmen arrived.