4

The “Opportunity”

As 1967 drew to a close, the war in South Vietnam was stalemated. In the dry season that lasted from October 1966 to May 1967, U.S. commander William Westmoreland had sent the formidable U.S. military machine that had been built up in South Vietnam on a series of offensives designed to win back the initiative and inflict heavy losses on Communist forces. U.S. brigades spread out in a checkerboard fashion over the countryside and sought out the enemy, drawing on their advantages in mobility and artillery. The main focus was the area around Saigon, where two massive U.S. operations code-named Cedar Falls and Junction City sought to annihilate the Iron Triangle, a Communist base area that had existed since the war against the French. Though they inflicted heavy damage on NLF and NVA forces, U.S. troops were soon forced to withdraw, ceding the sanctuary back to its occupants. Meanwhile, Communist forces maintained the initiative both in the northern part of South Vietnam and in the mountainous areas of what had formerly been Annam, and a grueling guerrilla war simmered on in the Mekong Delta. Westmoreland simply did not have enough troops to guard against enemy offensives in the north, destroy and occupy enemy base areas around Saigon, and drive the enemy from the delta. The result was stalemate.1

It would fall to Hanoi to break it. Throughout 1967, the Communist leadership was split into two factions. One, headed by party general-secretary Le Duan, believed the time would soon be ripe to launch a final military offensive in South Vietnam. Much like in the months before the U.S. intervention in 1964–1965, the Communists hoped they could break the ARVN with one decisive push and triumphantly enter the cities amid an anti-GVN and anti-American popular uprising. The presence of substantial U.S. forces in South Vietnam added a new layer of complexity that would be dealt with by diverting their attention to battles far from the cities, such as the famous siege of Khe Sanh. On the other side of the debate stood a group of officials headed by Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap, who argued that Le Duan’s adherents misunderstood the state of the war and that the Communists needed to dig in for a long struggle. A premature push would waste revolutionary resources and make the final victory more difficult to attain. As the matter was settled by day in high-level debates dripping with Marxist-Leninist verbiage, by night the secret police rounded up journalists, academics, and mid-ranking officials opposed to Le Duan’s approach and spirited them away. Ho and Giap left the country in unclear circumstances and remained there when the offensive began. Certainly not any more democratic than the Saigon regime, the dominant faction in Hanoi was more ruthlessly effective at imposing a strategic direction on its agents. Le Duan had won, and the orders for the offensive were carried south in August.2

The decisive push that North Vietnam’s paramount leader wanted came on the night of January 30, when combined NLF and NVA forces struck nearly every major urban area in South Vietnam. Saigon, which had long existed in an insulated bubble punctured only by acts of terrorism, saw major combat for the first time. The attackers seized almost all of Hue, where they would remain until dislodged by bloody street-to-street fighting in early March. While neither the collapse of the ARVN nor the urban uprising that Le Duan had hoped for occurred as a result of the offensive, its impact on American policy eventually marked a turning point in the war. Under domestic pressure from a public and media who had been led to believe that the war was on the verge of being won, Johnson soon announced that he was halting almost all bombing of North Vietnam and seeking to open peace talks with Hanoi. Formal talks opened in Paris on May 13. Sensing weakness, Le Duan ordered a second wave of attacks, resulting in a May offensive that the Americans dubbed “mini-Tet.” While the ARVN still held firm, Saigon again saw widespread destruction. Hanoi ordered a third wave in August, but by this point the Communist movement could summon only scattered ground attacks and the indiscriminate bombardment of the civilian population in Saigon by long-range rockets. After the August offensive fizzled, Communist main forces withdrew to base areas and cross-border sanctuaries to lick their wounds, allowing Bunker to report in October that allied forces had “more freedom of movement than they have had at any time since the start of the U.S. build-up.”3

The year 1968 was hence one of dizzying and seemingly contradictory shifts. By its end, Le Duan’s hope of a quick termination to the war lay in tatters, but apparently faltering American will had opened up a new possible path to victory through diplomacy. Meanwhile, the situation in the countryside had been rendered fluid by the Communist decision to mobilize all of its resources for the urban offensives. After an initial period in which they were stricken by despair, as the dust settled U.S. and GVN leaders in South Vietnam saw the opportunity to launch a nation-building offensive unlike anything they had attempted before.

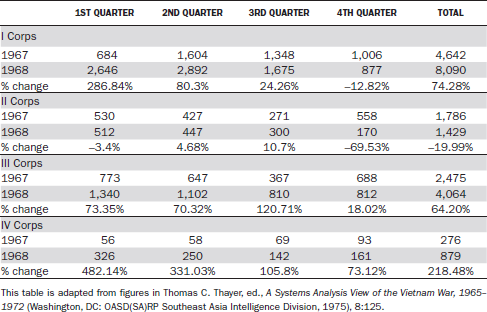

Table 1. U.S. KIA by corps area, 1967–1968

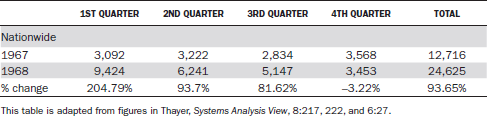

Table 2. ARVN KIA by quarter, 1967–1968

Holding the Line: The 1968 Offensives and Urban Relief

Although some high-ranking Americans would claim in postwar accounts that they did not share the panic that struck U.S. media and political circles in early 1968, those involved in the nation-building effort were gravely shaken.4 It is easy to understand why. As tables 1 and 2 show, “Tet” should be understood not as a singular event but as the beginning of a year of unremitting military pressure on the United States and the GVN that only began to tail off in the fourth quarter. There were only three instances over the whole year when any given part of the country was safer for allied forces than it had been at the equivalent time the previous year, and two of these came in the last quarter.

Physical damage was also widespread. Around 150,000 homes had been destroyed during the year’s offensives, primarily in Hue and the greater Saigon area.5 But smaller towns were not immune from the destruction either. In My Tho, the Mekong Delta hometown of President Thieu’s wife, the firepower required to dislodge two regiments of Communist forces left 25 percent of the population homeless.6 The fact that much of the damage was inflicted by U.S. firepower raised fears of rising anti-Americanism. As Saigon police chief Nguyen Van Luan, a close ally of Ky, complained: “The Viet Cong has no air force of its own, so it uses ours.”7 Playing on these themes, NLF propaganda attempted to drive a wedge between the Americans and their “puppets” in the GVN. Leaflets were distributed accusing “Thieu-Ky” of “lending a hand to the foreigner’s colonialist mission … destroying countless lives and properties, flooding our country with death, sorrows and sufferings.”8 With both U.S. firepower and Communist shelling of major cities bringing destruction to the urban population like never before, NLF propaganda could easily prove effective. Bui Diem had previously noted on trips to Saigon that the war had seemed very distant, and the population occupied with making a living and the twists and turns of the Thieu-Ky rivalry.9 After the offensives of 1968, the war would never seem so distant. Nguyen Thi Thu-Lam remembered that “never again were we to feel safe on the streets of Saigon.”10 The steady military pressure during the first three quarters of the year also vastly complicated the effort of resettling the homeless and restoring a sense of normalcy.

The initial damage to the GVN’s position in the countryside also seemed grave. Large numbers of RD cadres and local GVN officials had to be withdrawn from rural areas to aid with urban relief efforts and because of threats to their security, leading Komer to report in April that rural administration had been “seriously reduced.”11 As at other times of stress and insecurity, fleeing from the rural communities of which they supposedly were the leaders into the protective embrace of a distant state only underlined whom these officials really represented.12 By August and September, the NLF was announcing the creation of “liberation committees” in areas it controlled, following the promulgation of a Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) in June.13 Although little more than a rebranding exercise for its infrastructure in South Vietnam, these moves allowed the Communist movement to demonstrate to the world the extent of its political reach in South Vietnam and hence negotiate from a position of strength in the unfolding peace talks. Colby, now Komer’s deputy at CORDS, briefed military commanders in September that “in the event of a cease-fire, the enemy might claim political control of about one-half of the population of South Vietnam.”14 As Komer recognized, it would require new military offensives into the countryside to dislodge this PRG infrastructure and restore GVN rule.15 Thus, the military pressure placed on both the United States and the GVN in 1968 was matched by a new political challenge. Both the top civilian and military leadership in South Vietnam recognized its importance, but they first had to deal with the crisis in the cities.16

Figure 5. Devastation in Saigon in February 1968.

National Archives identifier 558530, General Black and White Photographic File of the Department of the Navy, Record Group 428, National Archives II at College Park, Maryland.

If Vietnamese civilians no longer felt safe in the streets of Saigon, then American officials no longer felt safe in their strategy. The relentless military and psychological pressure of the spring of 1968 led Bunker to write to Washington during a dark moment to question “how long this can be endured without threatening all that has been achieved here.”17 Komer was even more pessimistic. In a briefing to journalists in late February, he said that pacification had suffered extremely heavy setbacks in the Mekong Delta and I Corps, and that many hamlets previously considered “pacified” would now need returning to. While he noted there was a “vacuum” in the countryside after the heavy losses suffered by the Communist movement, he was pessimistic about the ability of the GVN to capitalize on it. And if the movement shifted its attention from the cities onto what was left of the GVN’s rural infrastructure, then “we’ll have problems, real problems,” Komer concluded.18 Several days after the briefing, Bunker dispatched Komer back to Washington to recuperate from the psychological strain placed on him by events. Bunker was so concerned about his subordinate’s mental state that he sent a secret cable to the White House asking that Komer not be pestered to take part in official meetings during his time in the capital.19

Nor was Colby immune from doubts. In February, shortly before he left to take over as Komer’s deputy at CORDS, Colby was one of several officials to place his name to a memo that seemed to ooze complete despair over current American strategy.20 The proposal, dubbed Operation Shock, stated, “Over the years the current leaders of Vietnam have developed a complacent assurance that American support is immutable. Consequently, they have felt free to approach the war in terms of gradualism, favoritism among the limited circle of personalities at the top and only a casual attention to mobilizing popular support and engaging the population actively in the war… . The Tet offensive can be utilized in a frontal assault on these attitudes and habits.”

In the view of the memo, the GVN’s inability to protect its own borders without half a million American troops and to keep the enemy out of the American Embassy “demonstrated that the present GVN lacks some of the principal attributes of sovereignty.” Faced with a weak state that was dependent on it for survival, the United States was justified in demanding that the GVN “follow U.S. direction” and allow its own structure to be remade according to U.S. wishes. The authors argued that Thieu should be compelled to give a greater role to Thang and Ky and that the GVN should then be given one hundred days to reinvigorate the pacification effort, tackle corruption, and expand the government’s base among the population. If it failed, unspecified but severe consequences were to be threatened.21 Operation Shock was circulated by Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms to several key figures in Washington, but without the authors being identified on the memo. It does not appear to have been circulated in Saigon.

Operation Shock was wildly unrealistic in assuming that the United States could simply snap its fingers and solve problems that had already failed to be resolved in nearly fifteen years of American involvement in South Vietnam. It also ignored political realities in Saigon. As a later CIA study noted: “No one can seriously have thought that President Thieu would consent to put his nemesis Nguyen Cao Ky in charge of both a mass corruption purge and a national political front.”22 Colby’s contribution to the memo is curious because his actions after he became head of CORDS did not remotely reflect anything written in the document. Nor were the other authors—Helms’s special assistant for Vietnam affairs, George Carver, and former Saigon station chief John Hart—bureaucratic gadflies. Consequently, it is hard to see the document as anything but the product of panic in the CIA in the immediate aftermath of the Communist offensives of early 1968.

American optimism was gradually restored as it became clear the Communist offensives would face military defeat, and as 1968 wore on, Komer turned to organizing joint U.S./GVN relief efforts for the urban population. As well as hoping to restore confidence in the government among the ravaged urban population, Komer hoped to establish a model of cooperation between CORDS and the Saigon regime in the future. The United States and the GVN formed a joint executive committee to run what became known as Project Recovery.23 Project Takeoff had failed because of a lack of GVN cooperation, but Komer and his colleagues “in effect operated as part of the Vietnamese government” during Project Recovery.24 The Central Recovery Committee was initially chaired by Ky, with Komer acting as his U.S. opposite number and Thang serving as chief of staff. Komer and his deputies also began attending GVN cabinet meetings during this period.

Project Recovery’s immediate focus was to provide for the vast numbers of evacuees created during Tet and the subsequent offensives. A CORDS report later noted that enemy offensives between Tet and August “generated over a million cases of people who, while they did not have to leave their homes for more than a few days, required assistance in reestablishing themselves after the death of relatives and/or the destruction of their homes.”25 Unlike rural refugees, the urban refugees generated during Tet usually moved only very short distances from their homes and maintained access to their livelihoods once normal economic life was restored in the cities. But many saw their homes destroyed in heavy fighting and needed to be rehoused. There was also a fear among Americans in Saigon that food shortages might quickly lead to riots, which the Communists could then misrepresent as the general uprising they had predicted.26

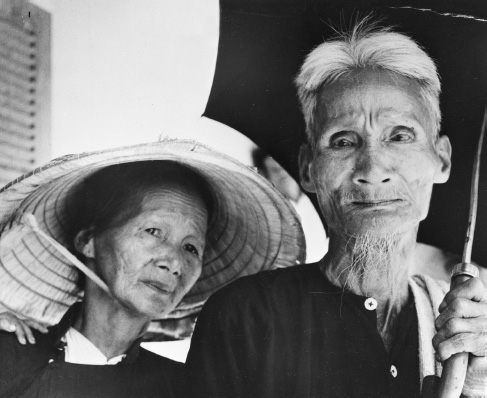

Figure 6. Vietnamese refugees in northern South Vietnam, 1965. According to the U.S. Marine Corps photographer, “the wages of many years of war are reflected in the faces of this aged Vietnamese couple.”

National Archives identifier 532436, General Photograph File of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, National Archives II at College Park, Maryland.

Feeling unable to trust its bureaucracy to oversee the rebuilding of shattered urban centers, the GVN decided the effort would take the form of “a community action project, with the government furnishing funds and materials and the people building their own houses on presurveyed plots.”27 The plan was to provide direct, tangible aid to the refugees rather than relying on the GVN administration to supervise building projects. Thang won an argument with the Americans on the committee over whether the corps commanders could be made responsible for delivering aid to refugees. As well as not wanting the United States to completely supplant the GVN at the most basic task of providing shelter for its citizens, he also argued that officials could be observed and punished for corruption during the process.28 As one U.S. official explained to a journalist, failure could have dire consequence for the GVN: “I think even the most corrupt official realizes what is at stake. The Government’s best support comes from the cities, and if it lost this support because of corruption in the refugee program it would be in serious trouble.”29

Komer was enthusiastic about Project Recovery, but his enthusiasm betrayed how limited was his grasp of the challenges of genuine nation building. It was one thing for the GVN to perform adequately in the distribution of American largesse to its citizens, and quite another for it to undertake fundamental reforms to build an active base of support and undermine the political appeal of the Communist movement. The need to focus on urban recovery had also meant a transfer of attention and resources away from rural areas, where the real battle for the allegiance of the population was still to be won.30 In addition, the nationwide refugee caseload actually grew substantially over the course of 1968 despite Project Recovery’s efforts. There were nearly eight hundred thousand refugees at the end of 1967, and this caseload had increased to over 1.3 million individuals by January 1969 despite the resettling of over a million temporary evacuees during 1968.31 Where the GVN’s rural administration was still functioning at all, it remained as sclerotic, centralized, and unresponsive as before. Local officials had to get permission from Saigon to take the smallest action, such as rebuilding a bridge or a classroom, and they could wait months for their requests to be answered.32 Komer’s earlier statement that he was lowering his sights “from the desirable to the doable” had now brought his sights very low indeed, admittedly through necessity. Project Recovery accomplished little more than helping the GVN stave off collapse in 1968, a necessary achievement but one that did not automatically promise a future of U.S.-GVN cooperation once the immediate emergency had passed. As the Americans stood eager to help, what happened next depended primarily on Thieu.

“A Great Opportunity to Be Seized”: GVN Reform in 1968

The initial Communist assault had found Thieu celebrating Tet in his wife’s hometown of My Tho, a fact unknown to the assaulting Communist forces. Had the rural cadres attempting to guide the attack not got lost in the unfamiliar streets, and had Thieu’s personal guard of elite rangers not helped fend them off, the president might have been captured. As it was, he escaped My Tho in a U.S. helicopter on the second day of the attack to return to Saigon.33 Absent from the political scene in Saigon in the first weeks of the offensive in unclear circumstances, the cautious general eventually emerged to take control. Over the course of 1968, he consolidated his grip on the GVN, never to relinquish it. “Little by little,” Ky later conceded, “the balance of power between us swung in his favor.”34 Tran Van Don observes that during this time “Ky gradually lost power, much like American vice presidents, but remained in the government.”35

Alongside this sidelining of his adversaries in Saigon, Thieu managed over the course of 1968 to strengthen Saigon’s grip on the localities. Liquidating Ky’s power also allowed him to bring to heel the corps commanders who were Ky’s most important allies, and to appoint his own men in their place. Unsure of his own position when the Thieu-Ky regime started in 1965, Ky had given the corps commanders “total authority over local decisions” in return for their loyalty to the central regime.36 If Thieu wanted to get a firmer grip on rural administration, he would have to rescind that authority. In consequence, Thieu worked with, and became reliant on, CORDS’s network of provincial and district advisers to provide support to local GVN officials, but also to spy on them. Only by using the United States was he able to make inroads against the corps commanders and their traditional system of corruption and patronage. In this sense, Thieu turned the concept of leverage on its head and used CORDS as leverage against his domestic opponents. By October, Bunker was able to report back to Washington: “Thieu is in fact now close to exercising the full powers vested in him by the constitution, and the extra-constitutional power of Vice President Ky and the other generals has continued to decline.”37 Thieu’s newfound reliance on the United States also made him appear more willing to listen to U.S. advice and engage in a genuinely collaborative relationship with CORDS to reform the GVN.

Amid the nerves of spring 1968, one word kept recurring to U.S. officials in South Vietnam. That word was “opportunity.” Even since the creation of CORDS, top U.S. officials had struggled to gain traction for their reformist ideas inside the GVN. The 1968 offensives came to be seen as an opportunity to galvanize the GVN to achieve reforms that would ultimately strengthen the South Vietnamese state once the immediate emergency passed. Lansdale was urging Bunker to see the offensive in this light in a memo typed even before the first day of the attacks was over. He wrote that “the extraordinary events of the past few hours open up a rare opportunity for President Thieu to exhibit some extra leadership right now that can have most rewarding consequences.”38 Bunker quickly took up the theme. At a meeting with Thieu shortly after the latter returned from My Tho, he told the South Vietnamese leader that the attacks presented “an ideal moment for him to demonstrate his leadership and to galvanize the nation.”39 Days later he told Thieu that the offensive was “a moment of opportunity” for him and Ky to bury their differences and unite with other top GVN leaders to prosecute the war more effectively.40 In a message back to Washington, Bunker said that the GVN faced a “crisis of confidence” caused by its inability to prevent the widespread destruction caused by the offensive. Nevertheless, he claimed the cloud had a silver lining: “It is to meet the crisis of confidence to which I have referred that I have been pressing, as strongly as I know how, on Thieu and other leaders in the government the idea that there is a great opportunity to be seized in this situation; that if the government moves quickly to help the victims, to move ahead vigorously with recovery and reconstruction, if it mobilized the potential support available to these efforts, it can score a very significant political as well as military success.”41

As well as hoping that the GVN would be invigorated by the offensive, U.S. officials calculated that the new level of political and military threat felt by the GVN might allow the United States to exercise greater leverage over the government’s behavior and structure. This had been the idea behind Operation Shock. Vann, who had been sharply critical of the softly-softly attitude toward leverage at the top of CORDS, likewise thought Tet and subsequent events provided an opportunity to change this approach. Cynical as he was of the GVN’s capacity to reform itself, he believed there was a need for much greater U.S. involvement in South Vietnam’s “so-called ‘internal affairs.’ ” Following the Tet Offensive and Johnson’s speech of March 31, Vann thought the GVN was more susceptible to such pressure than ever before.42 He also thought that effective change would require it. In July, Vann was asked by Ellsberg to explain why he thought the GVN would “rise to this which you describe as their opportunity.” “Well, we don’t know that they will,” Vann replied. “All I’m suggesting is that we try to force them to.”43 Bui Diem remembers that “in Saigon, strangely enough, the mood was exuberant” in government circles as the Communist offensives were easily beaten back.44 Bunker’s own sense that Tet presented an opportunity that could nevertheless be squandered was encapsulated in his invocation of a line from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar that he felt captured the moment well: “There is a tide in the affairs of men which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune: omitted, all the voyage of their life is bound on shallows and in miseries.”45

It remained to be decided how the United States could best help the GVN take fortune at its flood. Komer and Bunker were not of a mind to make dramatic gestures that undermined South Vietnamese sovereignty, as Operation Shock had called for, fearing that this would only vindicate Communist propaganda and undermine the long-term confidence and viability of the GVN. Instead, Komer and Bunker quietly pressured Thieu behind closed doors in the manner they had always considered appropriate. President Johnson set the tone in a message to Bunker a few days after the Tet Offensive had begun, instructing the ambassador to tell Thieu that the United States could no longer live with a “business as usual” approach and criticizing the GVN president for his previous “cautious approach to problems.” Present events, Johnson suggested, were an “opportunity” for Thieu to act more boldly.46 Bunker took the rare step of showing this presidential message to Thieu to demonstrate that the demand came from Thieu’s supreme patron. Bunker also told Thieu that “it is of the highest urgency for the GVN to act vigorously to meet both the immediate problems, as well as those of longer range and more deep-seated in nature.” In the latter category Bunker placed the incompetence and corruption of local administration, and the role of the corps commanders in perpetuating it. Rather than minimizing the scale of the problem as he had done previously, Thieu admitted that “probably some eighty per cent” of current province chiefs were incompetent or corrupt.47 Even before the shock of Johnson’s March 31 speech, Bunker and Komer attempted to scare Thieu into greater reforms by threatening him with a collapse in U.S. support on the home front.48 Bunker reported by May that “the Vietnamese are really beginning to face up to the fact that the time will come when they are on their own.”49

The operation of Project Recovery was initially beset by mutual recriminations in which both sides in the Thieu-Ky dispute appeared more interested in pinning blame for failure on the other than making the effort operate smoothly. Thieu at first absented himself from the committee, leaving Ky to chair it, and then Ky and Thang resigned, claiming that the rest of the government was not cooperating with them.50 In a blueprint eerily similar to that of Operation Shock, Thang reportedly urged Ky to have the constitution amended “so that he, Ky, can hold the post of Prime Minister, or to have Thang appointed to that post.” Thang claimed the corps commanders would back such a move. Ky dismissed the suggestion as “foolish talk,” adding that he and Thang “must work within the existing governmental framework for present.”51 Another source of pressure on Thieu was the powerful commander of the III Corps region, Le Nguyen Khang. Like many generals in ARVN, Khang was suspicious of the U.S.-backed trend toward democracy and civilian rule in South Vietnam, and favored a strong military dictatorship.52 Among the top leadership of the ARVN, he was far from alone in this point of view. As Bui Diem explained, the generals “stood to lose a great deal in the transition to civilian government … they would find themselves subordinate to political leaders with whom they carried no special influence… . Their attitude dripped with contempt for the very idea that a civilian government could rule effectively.”53

Khang also controlled the crucial military region around Saigon, which would be vital in any coup attempt. But realizing that the Americans would not tolerate any further coups, Khang forbade to openly entertain them, instead hoping to parlay his position into leverage over Thieu.54 On February 18, Khang led a meeting in which he, Thang, Ky, and Joint General Staff chief Linh Quang Vien blasted Thieu for the GVN’s “weakness” and what they saw as the ineffectiveness of the civilian ministries. Khang offered his resignation at this meeting as a symbolic gesture, knowing Thieu did not feel secure enough to accept it.55 Despite having initially chided Thang for his “foolish talk,” Ky began to press Thieu to appoint a general as prime minister as the year wore on.56

To the seeming surprise of his opponents, rather than bowing to demands to give the military and the Ky faction a greater role in governance, Thieu instead flashed his steel. He opted to ally himself with the Americans against his domestic opponents. Only the strong support and cooperation he received from CORDS both in Saigon and the provinces made this feasible.

Thieu’s first step was providing effective leadership to the relief effort. After Ky and Thang resigned from Project Recovery, Thieu leapt in and made a success of it, in the process demonstrating that it seemed to lose little through not having Ky and Thang’s participation. Buoyed by this close cooperation with CORDS and eager to take advantage of the crisis atmosphere as new enemy offensives struck, Thieu then began to implement more structural reform. On March 1, he removed the commanders of both IV Corps and II Corps, citing their incompetence under military pressure.57 Thieu appointed Major General Lu Lan, widely perceived as an apolitical general, to II Corps. Thang, still popular with the Americans and a key confidant of Ky, was sent to become head of IV Corps.

At the same time as replacing these two commanders, Thieu announced wide-ranging reforms in the relationship between corps commanders, province chiefs, and the central government. Province chiefs would no longer be appointed by corps commanders, but rather would be picked and supervised by the central government. Invoking the success of the Project Recovery task force, Thieu said that “province chiefs will act as the head of a task force in each province for the ministries’ representatives there.” They would be supported by CORDS. Meanwhile, civilian inspectors appointed by Saigon would oversee the province chiefs, whose ultimate responsibility would be to the interior minister.58 This returned South Vietnam to the system that had existed under Diem, in which the corps commanders were not yet official warlords in their own domains but answered to the central government.

Thieu soon began to demonstrate that this shift in responsibility had not just taken place on paper. Ten days after his initial announcement, he dismissed seven province chiefs in the II and IV Corps areas, where he had just appointed new commanders. He also dismissed the mayor of Hue, who had also failed to distinguish himself during the Tet Offensive.59 This amounted to a nearly 16 percent turnover in provincial leadership in one day. By the end of the year, twenty of the country’s forty-four province chiefs had been removed for corruption or incompetence, and some placed on trial. Ninety-one district chiefs, out of 243 nationwide, had also been removed.60 By September, Thieu had replaced nine of sixteen province chiefs and nearly half of the district chiefs in the Mekong Delta.61 When turnover due to deaths and other causes were added, over 50 percent of the country’s provincial leaders were changed during the course of the year. The replacements were handpicked by Thieu.62

The support of CORDS was vital in enabling Thieu to make these changes. Since the beginning of Project Recovery, CORDS officials had been observing GVN provincial and district officials to sniff out corruption and incompetence.63 Thieu made use of dossiers of evidence and advice from CORDS officials in deciding which chiefs to change, generally but not always following U.S. advice. CORDS was also vital in providing support to province and district chiefs whom the corps commanders shunned because they had been appointed from over their heads and were not part of the traditional networks of patronage and corruption. When Bunker told Thieu that CORDS had received reports that the corps commanders were not cooperating with local government officials and providing them military support when needed, Thieu “grew visibly annoyed” at the situation. It was clear under his reforms, he said, that corps commanders remained responsible for providing military support to the local chiefs when needed, even if they no longer had civil responsibilities. He also conceded that “province chiefs must depend more on CORDS and USAID than on corps and subordinate commanders to help them do their various jobs” in the civil sphere, but the ARVN “clearly must help” as well when military support was required.64 Thieu’s annoyance notwithstanding, it was only the existence of CORDS’s networks of advisers and the resources at its disposal that allowed province and district chiefs to declare any independence from the corps commanders at all. Had it not been for CORDS, province and district chiefs would have remained reliant on local ARVN units in both civil and military matters, with all the dilution of central government authority this had entailed since 1963. But the existence of CORDS gave Thieu an alternative to relying on the troublesome commanders and instead allowed him to align himself with the Americans, using their network to project his power throughout the country.

Thieu concurrently took steps to solidify his rule in Saigon. In May 1968, he felt secure enough to appoint Tran Van Huong to the position of prime minister, ignoring the growing military clamor for a general to get the job.65 Unlike many of the top figures in the GVN, Huong was actually born in what would later become South Vietnam, in the delta province of Vinh Long. Huong had refused to take sides in the Franco–Viet Minh War, then entered Diem’s service as the mayor of Saigon after South Vietnamese independence. Huong resigned the post after falling out with Diem and became a prominent oppositionist, eventually being jailed by his former patron for demanding liberal reforms along the lines of those favored by the U.S. State Department at the time. Being opposed to Diem did not stop Huong being critical of the generals who murdered him, even as he served in the short-lived regime that followed the 1963 coup. Huong later became prime minister in his own right in November 1964, only to be removed in January 1965 amid widespread Buddhist protests at his attempt to increase mobilization for the war effort. This clash with his co-religionists was only the latest episode in a career marked by independence, bloody-mindedness, and anti-Communist nationalism. Huong was also widely regarded as incorruptible. He had run against Thieu in the 1967 presidential election, coming fourth in a field of eleven.

In appointing Huong, Thieu was hewing closely to American advice. Bunker had personally indicated that he considered Huong, whom the CIA rated as the “most widely respected politician in South Vietnam,” as the best candidate for the post of prime minister.66 But Huong’s reputation and the fact he was a civilian also helped Thieu bolster the image of his government. With Huong on board, it would be harder for Thieu’s opponents to accuse him of sliding toward Diemist dictatorship as he centralized power. Bunker also hailed the new cabinet as “a considerable move towards civilian government,” both because Huong was expected to be a strong civilian leader and because it represented another way in which Thieu was strengthening the constitutional government at the expense of the military’s power.67 Huong also brought back General Tran Thien Khiem, another southern Buddhist who was then in Taipei as GVN ambassador, to serve as minister for interior. This role was vital now that province chiefs were responsible to the Interior Ministry. Khiem had been out of the country since he was ousted from one of the revolving-door juntas of 1964, and was feared throughout the ARVN because of the grudges he was presumed to hold from this incident.68

Huong’s appointment was opposed bitterly by Ky and Khang.69 They continued to tell American officials about the perils of civilian rule and the need for a military strongman, but they did not receive a sympathetic ear.70 A number of factors were by this time working to undermine the power and influence of Ky and his allies. The first was the simple fact that as Thieu’s government became more effective at carrying out reforms while working closely with the Americans, the space for criticism became more limited. Ky and Khang were increasingly unable to point to the GVN’s ineffectiveness as justification for their standpoint. The dilemma of the Ky faction on this point was illustrated when Khang held forth to Samuel Berger, the U.S. deputy ambassador, on his favorite topic: that South Vietnam “could not afford democratic institutions at this time” and that the United States “had made a major mistake in forcing them” on the country. Khang again questioned whether Thieu’s rule was “clear and firm” enough.71 But for the Americans, it increasingly was, and any deficiency did not stem from a surfeit of military involvement. It was precisely the trend toward the increased “civilianization of the government” that Bunker praised as the year wore on.72 What Bunker and other CORDS officials wanted was a GVN that was coherent enough to work with as a nation-building partner, and which had a network of responsive officials in the localities. Because Khang and Ky refused to participate in the GVN constructively, it began to look like their complaints stemmed purely from factionalism rather than valid ideological or policy concerns. It was not the form of government they objected to; it was their own declining power within it.

Ky’s entourage had limited options in response. The Americanization of the war in 1965 had put an end to the series of coups that had characterized Saigon politics since the fall of Diem, and Americans in both South Vietnam and the United States were in even less of a mood to tolerate them now. As Komer had stressed to Thieu upon his return from visiting the United States in March, American public opinion could not countenance internal strife in South Vietnam. Even Khang, considered by Bunker to be an “avowed opponent of constitutional democracy,” realized that acceptance of the GVN’s constitution was a prerequisite for continued U.S. support.73 With the seizure of power not an option, Ky and his allies could only access it through cooperation with Thieu and his American patrons. As CORDS allowed Thieu to expand his own power both by supporting his reforms of the GVN’s rural apparatus and by the advice its leadership provided to both him and his ministries, Ky’s faction found themselves increasingly irrelevant to the main concerns of the Americans. They hence became not only expendable but also to be seen mainly as potential spoilers by South Vietnam’s U.S. backers.

A third factor in the declining fortunes of the Ky faction was a series of deaths in May and June of 1968 that thinned the ranks of Ky’s supporters and close friends. On the first day of mini-Tet in May, National Police chief Nguyen Ngoc Loan sustained serious injuries while hunting snipers in the back alleys of Saigon. Then, on June 3, an errant U.S. helicopter missile badly wounded the mayor of Saigon and killed seven other officials, including Luan, the Saigon police chief who had made the apposite remark about the NLF “using” U.S. firepower. All the dead and wounded were allies of Ky, among them his “closest supporters.”74 Thieu moved quickly to appoint his own men to the now-vacant positions.75 The sudden loss of so many close allies and hence influence was dizzying for Ky. He seemed to vanish from the political scene, and newspaper reports placed him “out of Saigon, depressed and tired.”76 While his mental state was said to have improved by September, Berger still found him “subdued, pensive, and introspective”—adjectives that previously had rarely been applied to the flamboyant and belligerent former fighter pilot.77

A fourth factor that undermined the position of Ky’s faction was their repeated resignations, which only enhanced the impression that they were more interested in their faction’s power than in the effective running of the GVN. Both Ky and Thang had left the Central Recovery Committee before a month was even through, and Ky subsequently adopted and then abandoned a key role in the raising of territorial defense forces.78 Nor was Ky the only one who couldn’t hold down a job even when it was one the Americans considered vital. With the decline in Ky’s fortunes only accelerating, both Thang and Khang jumped ship in late June. Thang resigned from his position as head of IV Corps, claiming that Thieu did not trust him. This was the final straw among Thang’s American backers, and the general was left without effective supporters in either the GVN or on the U.S. side. He played no further role in the war.79 Khang also offered his resignation to Thieu as a token of responsibility for the rocket attack in Saigon that had killed so many prominent GVN officials. The offer was widely interpreted as a protest against the installation of the Huong government and the dilution of the Ky faction’s power in general.80 Thieu accepted the resignation and brought his close ally, Do Cao Tri, back from the ambassadorship to South Korea to become the new commander of III Corps.81

Thieu had emerged on top through a combination of his own cunning, chance events such as the rocket strike that killed Ky’s closest allies, and American support. The military and political challenges of 1968 had finally spurred the notoriously cautious general into action, and he had moved quickly to consolidate both American support for his regime and his own power within it. Attempting to ensure that American support would remain over the “long haul,” he moved to seize the power that was technically his under the constitution and use it to adopt reforms that pleased the Americans.82 The result was almost the opposite of what had been proposed in the Operation Shock memo earlier in the year. Rather than stepping aside and ceding power to Ky, Thieu had emerged in charge and had sidelined his rivals. It was a remarkable turnaround in Saigon politics. Now it remained to be seen if a similar turnaround might be produced where it really counted, in the villages.

Seizing the Nation-Building Initiative

For Komer, Colby, and other top CORDS officials, the most important item of business in the GVN’s in-tray was the need to reassert its rural presence. Komer had become increasingly concerned as 1968 wore on that Project Recovery was diverting the GVN’s attention from “rural recovery.”83 The Communist movement’s success at bringing the war to the cities had put the GVN on the defensive and forced it to spend nearly a year concentrating on its own base areas, to the detriment of rural nation building. The unremitting enemy military pressure and the need to consolidate the GVN’s control over the broadly pro-government cities made Thieu cautious and unwilling to embark on a counteroffensive for much of 1968. Back on the up and up following his convalescence in Washington, Komer told Thieu as early as March that he thought a “vacuum” was developing in the countryside. While the United States and the GVN had withdrawn to defend the cities and oversee Project Recovery, the NLF likewise had to weaken its grip over the countryside to generate the manpower for its continued offensives. While Komer said that a spirit of “offensive-mindedness” was needed, Thieu was much more cautious. He said that the GVN had to abandon grand ambitions for 1968 and cut back pacification activities to “oil spot areas around cities, towns, prosperous villages, and vital roads and canals.” Emphasizing the spirit of consolidation, he summed up by saying: “We should know what to sacrifice.”84

By October, Thieu came to accept the need for the GVN to reassert its rural presence. The starkly deteriorating military position of the Communist movement in the countryside was becoming apparent by this time. As a Communist history puts it, by late 1968 “our offensive posture began to weaken and our three types of armed forces suffered attrition. The political and military struggle in the rural areas declined and our liberated areas shrank… . Most of our main force troops were forced back to the border or to bases in the mountains.”85 A new GVN offensive seemed especially important, given the formation of the PRG and the Communist promulgation of its “liberation committees.” With its military campaign petering out, the movement seemed to be shifting to focus on political struggle.86 “By surfacing this apparatus,” Komer told the Mission Council, “they could attempt to validate a claim to ‘rule the countryside’—thus justifying either partition or a coalition government.”87 GVN officials were likewise concerned that the Communist movement’s network of village committees would allow it to assert “extravagant claims of political control.”88

CORDS and the GVN set out to work together on a counteroffensive. At a U.S. military conference in September, Colby issued the previously noted warning that the enemy might be able to claim control of nearly half of the South Vietnamese population in a cease-fire as things stood.89 He also displayed a map showing the extension of the liberation committees over South Vietnam and argued that, as he recalled, “a vigorous extension of security and political presence by the Government, with American support,” was necessary both to preempt the spread of NLF control and to penetrate areas they currently claimed.90 With the blessing of Abrams, what became known as the Accelerated Pacification Campaign (APC) was then developed by CORDS and the GVN. In early October, a series of bilateral meetings were held at which the Americans put the proposal to top GVN officials including Thieu, Huong, and a brooding Ky. On the U.S. side, Bunker, Abrams, Komer, and Colby were among the participants. These large bilateral meetings became the norm for developing strategies through which to bolster the GVN’s strength in the local areas. GVN cooperation with CORDS was spurred by the repeated emphasis that Thieu put on the need to win over the rural population.91 Following the pattern of Project Recovery, the United States and the GVN were working closely on joint campaigns.

As well as the influence gained by their close working relationship with the central GVN, CORDS officials up and down the chain of command were newly empowered by the APC and the interest that Thieu showed in it. In the early stages of presenting the plan to the GVN, Komer had sent word down to the DepCORDS in the four main corps areas to sell the concept of the APC to the corps commanders. When the commanders were asked by Vien whether the program was feasible, they said it was.92 Now that Thieu had made it clear that the corps commanders served at his pleasure and that he was aligning himself more forcefully with the Americans and with CORDS specifically, it behooved the corps commanders to follow American advice. Another key factor in boosting the influence of CORDS personnel was the fact that the APC relied on an American system called the Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) for measuring progress. The 1,084 hamlets selected to be part of the APC all had HES ratings of D or E, indicating that they were considered insecure by American advisers. Under the plan, success would be defined as upgrading them to category C or greater. The APC set specific numerical targets in every corps and province to be upgraded in this manner. As it was CORDS advisers who filled in the reports that determined what HES ratings were ascribed to each hamlet in South Vietnam, this gave them enormous influence over the central government’s perception of both the plan’s success and the performance of individual officials. HES had previously been criticized as a means of making false claims of progress in the war. But developments during the APC and thereafter showed that HES had another use—as a means by which CORDS advisers could focus the minds of their counterparts on the issues that they considered important in a local area, and then pass judgment on their performance up the chain of command via the HES ratings. As a GVN briefing noted, “President Thieu, in order to gauge progress more accurately and to provide a common basis for planning, chose to use the American Hamlet Evaluation System.”93 In this context it was more important as a tool of leverage than as an objective measure of progress. CORDS officials were careful not to make a public fanfare about the campaign and especially not to make a public relations issue of the numerical targets. Though the broad outline of the plan was revealed in the press, even the detail of its name was not widely known. Three weeks into the campaign, the veteran New York Times correspondent Charles Mohr erroneously reported that the APC was called “Quick Fix.”94

HES was hence not being used to create an illusion of progress. It had instead become a tool both in reinforcing Saigon’s rule over the provinces and in solidifying the role of CORDS advisers in acting as the central government’s eyes and ears to assess the performance of its own officials. Unlike during the 1968 planning process, when Thang had not even been able to get the corps commanders to alter their plans, the APC was centrally conceived from the start. To further demonstrate his commitment to the APC and to nation building more broadly, Thieu established a Central Pacification and Development Committee. Chaired by Huong and often attended by Thieu, the committee met to consider policy issues and oversee cooperation on plans for 1969, in which the GVN would try to build on the gains of the APC.

Using leverage of the form that Komer had long advocated—behind the scenes in Saigon—combined with the newfound ability of U.S. officials to use their influence in the localities, CORDS finally seemed to have a chance to work as intended. It is little surprise then that Komer stated shortly after leaving his job that he was “perhaps prouder of the APC than anything else.”95 Even Vann, who had been so critical of Komer’s leverage concept and his understanding of nation building in the past, was impressed. The situation in Vietnam, he stated in January 1969, is “better … than I have ever before seen it.” He continued: “The changes in province chiefs and district chiefs have generally been good, and in retrospect, I attribute Bob Komer’s initiative in securing leverage, establishing management tools such as HES and TFES (and initiating the Accelerated Pacification Campaign), to mark him as the greatest single American contributor to progress in Vietnam.”96 Given that Vann had previously been critical of both Komer and his “management tools,” this was high praise indeed. Berger evinced similar optimism in September, when he told a chastened Ky that “many long term observers say the Huong government is the best one in a decade.”97

Yet the events of 1968 also contained a cautionary tale. It was initiatives by the Communists that had changed the dynamics of the war. The nation-building effort, which had barely begun to be implemented at the grassroots, would be vulnerable to similar shocks in the future. And in 1969, there was a new administration in Washington—one determined to put its own stamp on the war.