5

The Nixon Administration and Nation Building

When he heard that Richard Nixon had been elected president in late 1968, the British counterinsurgency strategist Sir Robert Thompson had severe misgivings about what lay ahead. Although he had become highly critical of the way the Johnson administration was prosecuting the war, he never doubted that it placed a high priority on the containment of communism in the Far East. But the new president was an unknown quantity. It would be easy for him to declare that Vietnam was a war that had been started by Democrats and lost by Democrats, and that all an incoming Republican administration could do was get out. Thompson was not the only one who thought Nixon might take the easy option. According to Thompson, the staunchly anti-Communist Singaporean prime minister Lee Kuan Yew took much the same view shortly after Nixon’s election, bursting out to the Brit: “They’ve lost, haven’t they?”1 At the other end of the political spectrum, Daniel Ellsberg, by this point an ardent skeptic of the war, recalled that he felt no special alarm at Nixon’s electoral triumph over Hubert Humphrey: “I knew no reason to think that Nixon would prolong the Democrats’ failed war longer than Humphrey; if anything, as a Republican, he might do the contrary.”2 Buoyed by such hopes, Ellsberg even agreed to work with the administration in its early days.

His disillusionment, however, came quickly. Everything hinged on how Nixon reacted to the two key legacies of 1968: an increasingly inflamed and antiwar public discourse in the United States and an altered strategic situation in South Vietnam. Confounding expectations of a quick withdrawal, Nixon and his key national security aides—particularly National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger—aimed to pull out slowly and cautiously. By doing so they hoped to prevent withdrawal from harming either their domestic political position or U.S. credibility abroad.

Historians have tended to be transfixed by Kissinger’s diplomatic activities in Paris and Nixon’s military ventures into Laos and Cambodia, which were two cornerstones of this strategy. Less attention has been given to the administration’s attitude toward strengthening the GVN. Alongside the policy of strengthening the ARVN, which came to be known as Vietnamization, the Nixon administration also showed a keen interest in the development of GVN rural governance. They did not carry out any dramatic interventions in policy in this area, as Johnson had through the creation of CORDS. Nor did they share the reformist impulses that had led Johnson to first place a focus on the need to improve the lot of the South Vietnamese peasant through economic development. Instead, the new administration was focused on what Kissinger sometimes called “the control war.”3 It stressed the need for the GVN to exercise effective control over its population both to strengthen its hand at the negotiating table and to be able to stand up to the Vietnamese Communist movement after an agreement. Dismissing the idea that providing material benefits to the population was the key to success and unconvinced by the necessity of active as opposed to passive support for the GVN, Nixon and Kissinger came to stress “security” and physical control of the rural population, much as Komer eventually had. There was as a result substantial continuity between the two administrations, a fact that has been missed either because historians have overemphasized Johnson’s initial reformist impulses or underemphasized Nixon and Kissinger’s concern with “pacification.”4 Communist histories, on the other hand, emphasize the importance of “pacification” in the latter years of the war.5

While not ordering any dramatic departure in nation-building policy in South Vietnam, the administration did bring about a revolution in the White House’s ability to understand its progress. While Komer and Johnson had been preoccupied with the herculean task of creating CORDS and had little time left over for asking larger strategic questions about its chances of success, Nixon and Kissinger inherited a mature policy and then subjected it to withering analysis. Through the creation of a Vietnam Special Studies Group (VSSG) dedicated to the task, Kissinger brought a sophisticated understanding of the limits of nation building in South Vietnam to the White House. The fact he did so shows how important he considered the effort. But the group’s sobering conclusion that the GVN was unlikely to survive U.S. withdrawal undermined a key requirement for the success of a strategy that the administration had inherited but never truly believed in. If the Vietnam War was “effectively” won by the early 1970s as some have claimed, then this was far from apparent to Nixon or Kissinger.6

Nixon, Kissinger, and Nation Building

The inauguration of Richard Nixon as president in January 1969 brought to an end the period in which the making of Vietnam policy had been dominated by the now tired men who John F. Kennedy had brought to Washington nearly a decade earlier. The main members of Nixon’s national security team—Kissinger, Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird, and Secretary of State William Rogers—were not personally committed to the policies of the past. Kissinger especially was known to be highly skeptical of the way the war had been conducted, and especially of U.S. nation-building efforts. In an article for Foreign Affairs written before he was selected to serve in the White House, Kissinger had criticized Johnson’s strategy for the war and especially weaknesses in the “so-called pacification” program. In the article, he highlighted two key weaknesses of U.S. efforts to strengthen the GVN, pointing out there was “no concept as to how to bring about a political framework relating Saigon to the countryside,” and that current strategy resulted only in “military successes that could not be translated into permanent political advantage.”7

Like Nixon, Kissinger placed great emphasis on the manner in which withdrawal from Vietnam took place. In a widely cited passage in his Foreign Affairs article, Kissinger argued that the United States could not simply abandon the GVN: “The commitment of 500,000 Americans has settled the issue of the importance of Viet Nam. For what is involved now is confidence in American promises.”8 Keeping that confidence alive throughout the world, Kissinger thought, depended on ensuring the survival of the Thieu government after American withdrawal. This sometimes brought Kissinger into conflict with other members of the administration. Laird, a nine-term congressman who had served on the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee, was highly attuned to domestic politics and the strains that the continuation of the war was placing on the U.S. military in a time of budget constraints. This often led him, along with Rogers, to push for a faster withdrawal of U.S. forces than Kissinger thought wise.9 Laird’s ability to manipulate the Pentagon budget in a way that forced a certain pace of troop withdrawals from Vietnam meant that even though Kissinger was the most influential of Nixon’s courtiers on matters pertaining to Vietnam, he did not always operate in circumstances of his own choosing.

There was no individual at the top level of the Nixon administration who placed the same emphasis on reforming South Vietnam as Johnson had done, nor did the administration order a dramatic restructuring of the U.S. nation-building apparatus that had taken shape in CORDS. But this did not mean that the administration had lost interest in strengthening the GVN. Despite their military escalations, Nixon, Kissinger, and Laird were not inclined to believe that a “military victory” was possible in Vietnam, especially after Nixon abandoned plans for a dramatic escalation in the first year of his presidency.10 As Laird told Nixon when the latter requested that maximum pressure be put on the enemy, Communist attacks could be “repulsed with heavy [enemy] losses,” but there was little that could be done to “produce any significant change in the military situation over any short run period of time.”11 The lack of any unilateral military option was worrying because, as Laird told Thieu during a trip to Saigon, “time had run out on the last administration in terms of public support for our Viet-Nam policy.” The administration had to stay ahead of the American public by ordering troop withdrawals and shifting the burden of fighting to the ARVN.12 At the end of the trip, Laird recommended the withdrawal of from fifty to seventy thousand U.S. troops from South Vietnam in 1969.13 While he later backtracked officially from this high figure and settled on twenty-five thousand, Rogers continued the pressure for an even larger withdrawal. Thus began the steady drumbeat from both the Pentagon and Foggy Bottom, which would continue throughout the administration.14 Nixon would prove receptive, and he eventually announced the withdrawal of sixty thousand troops in 1969.

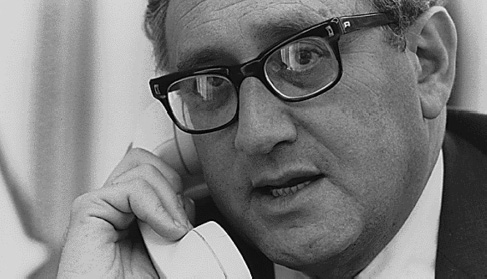

Figure 7. National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger set up a sophisticated system in the White House to monitor the progress of nation building in South Vietnam.

Photograph GRF-WHPO-A4263(26), Gerald R. Ford White House Photographs, White House Photographic Office Collection, Gerald R. Ford Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

The withdrawal of U.S. forces without the abandonment of the goal of maintaining the Thieu regime naturally placed a large burden on U.S. efforts to strengthen the GVN, as the Saigon regime could now foresee the day when it could no longer rely on U.S. forces to defend it. The thought that this day would come too soon “torment[ed]” Kissinger.15 As he told Nixon in July 1970, he feared “a crunch point where we are caught between an ally that cannot withstand any further American withdrawals and a public that will not stand for any further involvement.”16 Nixon likewise wrote in his memoirs that he agreed that the “central problem” was “whether the South Vietnamese were sufficiently confident and prepared to defend themselves against a renewed Communist offensive at some time in the future.”17 Kissinger was concerned that the pace of U.S. withdrawal was being determined by budgetary and political considerations rather than an objective assessment of the situation in South Vietnam. He was also concerned that what seemed to be steady gains in the GVN’s strength depended on a U.S. security shield that was being steadily withdrawn, and not Saigon’s intrinsic strength.18 When Tony Lake and Roger Morris, two members of Kissinger’s staff who were to resign over the Cambodian incursion, warned their boss that the United States was on course to withdraw from South Vietnam faster than was prudent, Kissinger was receptive and continued to mention his concerns to Nixon.19

Lake and Morris eventually went even further, warning that they did not believe there was “any option” that could achieve “an eventual political solution in South Vietnam in which most of us could take comfort.”20 This, however, was not a viewpoint that Kissinger expressed to the president. Instead, Kissinger placed his faith in two parallel tracks: negotiations with Hanoi, and the policy of “Vietnamization,” which focused on developing the military capabilities of the ARVN through training, expansion, and equipment transfers. In the negotiations, Kissinger perceived that the United States had three bargaining chips. One was the rate of withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Vietnam. The second was the level of coercion that could be brought to bear against North Vietnam’s assets. The third was the extent and durability of the GVN’s control of the South Vietnamese population. If Vietnamization allowed Saigon to durably establish control over much of the rural population, the allies would be strengthened at the negotiating table. Hanoi might be forced to settle faster if it felt it was faced with a situation in which the GVN was continually strengthening and improving its relative position.21 The more the GVN was able to accomplish without American support, then the more durable its position would appear. The strength of the GVN was hence a crucial bargaining chip in the negotiations with Hanoi. As the negotiations deadlocked over demands by the North Vietnamese delegation that the United States overthrow Thieu as the price for a peace agreement, it became in fact the key point in the negotiations; this was not surprising, as the governance of South Vietnam was the central issue of the war.

The strengthening of the GVN was thus central to both the policy of Vietnamization and U.S. negotiating strategy. It was also implicated in the administration’s coercive strategy in Cambodia and Laos. Both when U.S. forces invaded Cambodia in 1970 and when they backed an ARVN assault into Laos in 1971, the main aim was to clear out NVA supply and logistical networks. As raids, they could set back impending Communist offensives and buy more time for the GVN to strengthen itself, but without fundamentally altering the balance of the war. Kissinger listed the benefits of the Laos operation as including “very important” blows to the NVA logistical network and the deterrent effect that would compel the NVA to maintain combat forces in Laos in the future, meaning “these forces (a portion of which were formerly in South Vietnam) cannot be used to threaten Vietnamization in South Vietnam.”22 The Cambodian incursion had been deemed to have a positive impact for the same reasons.23 But even though these temporary escalations could divert North Vietnamese resources and alleviate pressure in the South in the short term, it remained the case that developments in South Vietnam itself would decide whether the Nixon administration’s strategy was a success. This was so whether the war was “doomed always just to trickle out the way it is,” as Nixon believed in a pessimistic moment in September 1971, or whether a negotiated settlement could eventually be reached.24 As a result, efforts to bolster the GVN remained central to the success of U.S. strategy.

The Vietnam Special Studies Group and the War

If Komer had been a doer, then Kissinger was, especially at the outset of the new administration, an analyzer. Kissinger had received his PhD from Harvard in 1954 and had spent the decade and a half since in the academic study of international relations. He brought a sophisticated view of the complexity of the Vietnam War—and especially of nation building—with him to the office. “Throughout the war, criteria by which to measure progress have been hard to come by; this problem has continued during the negotiations,” Kissinger wrote in his Foreign Affairs article of January 1969. “The dilemma is that almost any statement about Viet Nam is likely to be true; unfortunately, truth does not guarantee relevance.”25 Kissinger was skeptical of the accuracy and relevance of the statistics that were used to measure progress in the war.26 The first communication that Kissinger sent to William Colby, Komer’s successor as the head of CORDS, stressed “the need for realism in reporting on the pacification program.”27 Laird and Nixon felt likewise. After hearing an optimistic assessment from Johnson administration holdovers about the declining morale of enemy forces in South Vietnam and their apparent willingness to surrender, Nixon pointed out that “I think there is a tendency to get skeptical of these optimistic reports,” while Laird interjected: “I have heard these briefings each year and each year they get more optimistic and, therefore, I hope that we will be very careful in digesting the material which is put forth.”28 When Nixon met Abrams for the first time in May, Kissinger suggested that he inquire whether “the apparent progress in pacification is significant and whether or not he estimates that GVN control of the countryside is actually progressing.”29

Kissinger set in motion an internal White House effort to measure progress in nation building, down to the analysis of individual provinces. Like much of the broader reshaping of the NSC and the policy-making process that Nixon and Kissinger embarked upon, this was done in a conscious attempt to improve on the informal style of the Johnson administration, which had made its policy at secretive and much-derided Tuesday lunchtime meetings. The NSC system that Nixon and Kissinger constructed has often been viewed as a cynical means of expanding White House control over government agencies and narrowing the channels of debate and dissent. On Vietnam, at least, this is only a partial impression. Nixon personally made some of the most controversial decisions of his term—such as the Cambodian incursion—against the wishes of almost all his advisers, but the new NSC system was not integral to his ability to do so. Similarly, Kissinger’s ability to conduct negotiations with the North Vietnamese without the knowledge of most of the rest of the government did not depend on the new NSC system and would have been just as possible between Tuesday lunchtimes. While Nixon and Kissinger may have carried out a lonely policy at the negotiating table in Paris or in the Oval Office during the Cambodian incursion, the regular NSC machinery they set up actually served to widen the debate and information flow within the government on more routine matters. The new system provided multiple forums in which periodic and detailed assessments of the situation in South Vietnam could be presented as papers by the relevant agencies and then discussed, something never possible under Johnson. One typical meeting in January 1972 had twenty participants from State, Defense, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the CIA, Treasury, and the NSC and debated matters such as enemy intentions and capabilities, the accuracy of intelligence, and the progress of Vietnamization.30 The wide variety of agency input provided for a much greater degree of debate about the progress of the war and of nation building in particular than had been possible under the Johnson administration.

Johnson had created Komer’s office as a means of bringing White House influence to bear in shaping the development of the nation-building program in South Vietnam. But he had never grappled in a holistic fashion with what exactly he wanted from the program and how it could help achieve U.S. war aims. Inheriting a mature program, Kissinger instead organized his own office specifically for the purpose of assessing that program’s effectiveness. Kissinger’s NSC machinery included two forums specifically devoted to the study of issues related to Vietnam. The first of these, the Ad Hoc Group on Vietnam, was created in February 1969 to prepare papers for consideration by the wider NSC.31 In recommending its creation to Nixon, Kissinger told him that while the group would be useful to coordinate responses to Communist offensives, “it will not preclude the type of planning we conducted on Tuesday with Mel Laird and [Air Force Chief of Staff] General McConnell”—in all probability a reference to planning for Operation Menu, the secret bombing of Cambodia. Such sensitive matters, Kissinger assured the president, could be kept out of this channel. Nixon duly signed off on the recommendation to create the group.32 This demonstrated that while Kissinger and Nixon did indeed work together against other agencies and government officials, this was not the purpose of the regular NSC machinery.

This also applied to the second group that Kissinger created, the Vietnam Special Studies Group. Its purpose was the “systematic analysis of U.S. policies and programs in Vietnam.”33 The group was chaired by NSC staff members, first Laurence Lynn and later Wayne Smith.34 Until he left the administration after the Cambodian incursion, Lynn was considered by Kissinger to be a rigorous analyst, and the VSSG continued to impress him under Smith.35 The memo that Kissinger sent to Nixon suggesting the creation of the VSSG—which was drafted by Lynn—cited numerous “preconceptions” that were said in the past to have led officials “astray even though a careful and objective analysis of readily available facts would have told them differently.” It cited the failures of the Strategic Hamlet Program, optimistic assessments of the impact of bombing North Vietnam, the shock of the Tet Offensive, and “our excessively optimistic expectations for the various ‘revolutionary-development’ type cadre programs.” Once constituted, the memo continued, the group could help to guard against such misconceptions by considering the progress of Vietnamization, land reform, territorial control, and other aspects of the war and nation-building effort in South Vietnam.36

Kissinger was receptive to these proposals. From the beginning of the new administration, he had displayed skepticism toward reporting systems inherited from the Johnson administration. He was also dissatisfied with the quality of analysis available on the strength of the GVN and progress of the war in general. Despite Ellsberg’s reputation as a well-established critic of the war, Kissinger brought him into the administration to help him define broad policy options.37 While working for Kissinger, Ellsberg suggested that the White House should issue each national security agency involved in Vietnam with a series of questions designed to expose inconsistencies and gaps in knowledge and interpretations of the war among the agencies. Ellsberg thought this would be especially useful in temporarily wresting the monopoly of interpretation on certain issues from the agencies and showing the wide variety of interpretation that existed within the government.38 Kissinger took this advice and set Ellsberg to work developing a set of questions that would most accurately reveal where the bureaucratic bodies were buried. Kissinger’s use of outside experts both to increase his own knowledge and bolster the White House’s position set the tone for an administration that would be both much more intellectually curious about the war and more dedicated to setting up an independent analytical capability in the White House to understand it. When Lynn wrote to Kissinger suggesting the creation of the VSSG, he noted that Ellsberg’s project was the first time that many granular details of the war, including those related to nation building, had been discussed at the White House level. He proposed the VSSG as a way to institutionalize this process.39 Although Ellsberg became a strident critic of the administration, the early example he had set with National Security Study Memorandum 1 of how to best challenge the national security bureaucracy hence lived on through Lynn’s proposals and the creation of the VSSG. The group was created on September 16, 1969.40 Ellsberg thus contributed to the running of the Nixon administration’s Vietnam policy in a way not appreciated by historians to date.

Despite their interest in strengthening the GVN, Nixon and Kissinger viewed this task mainly through the lens of increasing its military capabilities. At the very first NSC meeting on Vietnam, one of Nixon’s priorities was Saigon’s internal security forces. Echoing Johnson’s words from late 1966 about the ineffectiveness of civilian nation builders, Nixon stated that he believed that “the AID people are totally unsuited to supervise the development of local security forces, stating it is like the blind leading the blind, adding AID is incompetent to handle this mission.” Nixon also inquired about the leadership of the Chieu Hoi program, which was designed to encourage defections from Communist forces in South Vietnam. When told that the job fell under the remit of CORDS, headed by Colby, Nixon asked “is he a specialist, does he have any idea of what he is doing?” He seemed satisfied to hear that Colby’s qualifications included having previously served as CIA chief of station in Saigon. Nixon was not similarly satisfied, however, with the answers he received on local security forces—and so he ordered a “complete report on the whole program to include who is doing it, whether he is qualified, what system he is employing.”41

This concern with measures that either increased Saigon’s coercive capacities or cut directly into the insurgency—but not on those that aimed at increasing popular support for the GVN or reforming local governance—prefigured the administration’s focus. It was a preoccupation shared by Kissinger. In his Foreign Affairs article, Kissinger had drawn an explicit link between the negotiations and territorial control, complaining that U.S. and GVN assets were spread too thinly to produce durable gains for the GVN in extending its control of the rural population. “For purposes of negotiating, we would have been better off with 100 percent control over 60 percent of the country than with 60 percent control of 100 percent of the country,” he explained—a viewpoint he continued to repeat in almost the exact same words throughout the Nixon administration.42

Unlike the Johnson administration’s early moves toward promoting social and economic reform, or the CIA’s concept of participative nation building, Nixon and Kissinger focused on the physical control of the population. Like Komer, they were dismissive of those with a wider view that differentiated between nation building and mere pacification. When Johnson had moved to put CORDS under the military, Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms had warned him that success in South Vietnam depended on a “motivated population, not merely an administered one.”43 Others made similar arguments in the Nixon administration. Recognizing the link between the GVN’s political base and negotiations, Lake advised that the key factor would be how many areas of the country were “loyal to the GVN—not those militarily occupied or undergoing pacification.” Lake warned that GVN “control” of areas of the country where the population was not loyal would prove ephemeral, especially when the GVN could no longer benefit from U.S. troops and resources and had to spread itself more thinly. Instead he suggested that the GVN carry out local political reforms, to include province and district elections, in areas where support for it was already the deepest. The development of a true political base for the GVN “puts the most meaningful kind of pressure on Hanoi … since it threatens their future prospects in a way that current casualty levels cannot.”44

As Johnson had brushed Helms’s concern aside, so Kissinger did with Lake’s. While Lake’s focus on priority areas may have seemed to chime with Kissinger’s preference for “100 percent control over 60 percent of the country,” it also rested on a fundamentally different concept of what constituted “control.” For the purposes of the negotiations, which were Kissinger’s hope of ending the war without the risks of mere unilateral withdrawal, the GVN’s ability to claim control of the rural population was more important than whether it had gained their “loyalty.” Kissinger focused on the GVN’s institutions of control rather than on whether it had developed ties of mutual obligation with its population. Another reason to minimize the role of loyalty was that it was difficult to measure. A Special National Intelligence Estimate released just before Nixon’s inauguration had warned that it was “almost impossible to measure” the GVN’s progress in “gaining the allegiance of the people.”45 This was a stark admission of the limited manner in which U.S. nation builders, even those with a wider conception of their task, had managed to penetrate and understand South Vietnamese rural society. Like the reports of a decline in enemy morale that Laird and Nixon had questioned in their first NSC meeting, an assessment of loyalty to the GVN was bound to be impressionistic and vague. Kissinger’s interests in what he sometimes called “the control war” were more concrete.46

This became apparent as the VSSG developed, under his tutelage, the most sophisticated analysis of the situation in the South Vietnamese countryside that had yet graced the White House. The analysis reflected both the administration’s focus on what could be tangibly and reliably measured and its interest in the extent of GVN control of the rural population. An early VSSG study defined control as “the ability of one side or the other to possess resources—people and their production—for its own purposes and to deny the use of such resources to the enemy.”47 This was a narrow conception of nation building that concentrated on population control rather than active political loyalty. This physical control of the countryside was thought to be “closely related” to the overall strength of the GVN, as “the GVN must achieve dominate [sic] control over the countryside, if it is to survive.”48 Control was defined as the permanent presence in any given hamlet of both local GVN officials and local security forces to the complete exclusion of their equivalents from the NLF, the hamlet infrastructure, and local guerrillas. Conversely, a hamlet was said to be under enemy control if the latter two existed to the complete exclusion of the GVN equivalents. In between these two poles lay a large gray area of hamlets said to be “influenced by both sides.”49 Those under GVN control, meanwhile, had to be subject to its predominant influence both day and night.

Within the study, the concept of control was explicitly differentiated from the concepts of “security” and of “support.” While security was said to exist where the population was safe from enemy-initiated violence, this was seen as a mere prerequisite for control and not in itself indicative. An area may be secure simply because the enemy had made a decision not to challenge security at that time, perhaps to carry out other tasks of military significance such as recruiting or political activity. This meant that areas of apparent security always exceeded areas of GVN control in size, a situation that the authors of the study felt had given a misleading impression of the GVN’s strength in the past. The situation with regard to the concept of support was different. The authors considered positive endorsement of one side or the other by the population to be of “only limited relevance” to the situation in South Vietnam, as well as being difficult to measure.50 Within this framework, neither USAID’s materialist approach or the cadre programs designed by Chau and the CIA had any significance. As Kissinger pointed out in a meeting to discuss the paper, social and economic assistance programs did not necessarily have implications for control, as the enemy could simply be choosing not to contest these programs.51 As critics of the Tigers had pointed out in the past, nor was it the case that support for the GVN could necessarily be inferred from a program’s existence. The VSSG concluded that popular support was more likely to follow than lead control gains, and that social and economic reform was not necessarily relevant to control, as the NLF could welcome such improvements without any lessening of control. Reforms “may even be credited to the Viet Cong if Viet Cong presence is viewed as the only guarantee that the GVN will continue to perform on behalf of the rural inhabitant.”52

Using this framework, the VSSG set about analyzing recent shifts in the “control war” and what had brought them about. Writing in late 1969, the group concluded that the GVN had improved its position markedly since the enemy offensives of 1968. Prior to the offensives, a situation that the report labeled a “control stalemate” had existed, with the GVN in control of around 20 percent of the population compared with the NLF’s 35 percent, and the rest under the influence of both sides. CORDS hence seems to have had little impact. But while the GVN position had then suffered markedly as a result of the Tet Offensive, the decimation of the NLF’s infrastructure and personnel during the offensive had prepared the way for impressive GVN control gains afterward. By September 1969, the VSSG concluded that the GVN controlled 54.7 percent of the rural population to the NLF’s 6.7 percent, with 38.6 percent under the influence of both sides.53 However encouraging these figures sounded, an analysis of the factors that had brought them about was less so. The study was based on an in-depth analysis of the situation in five provinces, and in four of them it was found that it was principally aggressive action by U.S. forces that had created the environment in which the control gains were possible. So even though the proximate cause of the increase was a vast expansion of the GVN apparatus and local security forces, this had taken place behind a shield of U.S. forces. It had also been helped by the damage that had been dealt to the enemy infrastructure during the 1968 offensives.54

A trip to South Vietnam by Lynn and the NSC staffer Robert Sansom in January 1970 “to make a first hand evaluation of the situation in the countryside and of the extent and durability of recent improvements in GVN control over the rural population” only reinforced these impressions. The two found that the momentum of GVN control gains seemed to be slowing rapidly and that it was “far more likely that the GVN will lose control than it is they will significantly increase it” during the period of American troop withdrawals.55 Even though Sansom was an expert on the social and economic situation in South Vietnam who would soon publish a book titled The Economics of Insurgency in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam, he and Lynn made little comment on such matters in their report, instead focusing narrowly on population control.56 They agreed that popular support tended to follow rather than lead control, placing the emphasis on “pacification.”57 As they likewise attributed control gains to aggressive actions by the very U.S. forces that were now being withdrawn, it followed that the loss of control likely to follow would be significant.

Kissinger wrote in his memoirs that the conclusions of the VSSG studies were “moderately encouraging, but we also knew that North Vietnam’s confidence was unbroken.”58 He put his finger here on the central weakness of the GVN position. As the VSSG analysis had recognized, recent control gains were attributable to the two factors that the United States and the GVN were least able to control in the future. The first was the presence of American forces, which provided the shield behind which GVN control had been consolidated, and the second was the damage done to the Communist movement in 1968. If the Communist movement could capitalize on its “unbroken” confidence to challenge the GVN again, Saigon would be in trouble. As U.S. forces continued to be withdrawn, it was not clear if ARVN local security forces would be able to meet this challenge in the long term. None of the VSSG studies indicated that Vietnamization was proceeding quickly enough to allow the ARVN to take over from the United States militarily. Moreover, the conclusion that measures leading to increased popular support had only a marginal impact on control indicated that there was also little opportunity for the GVN to improve or maintain its position through reforming local governance.

Boasting about the studies to the British counterinsurgency expert Sir Robert Thompson in a way that also revealed his doubts about the underlying reality in South Vietnam, Kissinger said: “There never before had been a government consensus on what was actually happening, and we were trying now to reach such a consensus—perhaps five years too late.”59 Both parts of this statement were significant. It was certainly true that the VSSG allowed for a sober and clear-eyed view of the “control war,” even if narrowly defined, in a way that the Johnson administration had never managed. Nixon thought the resultant analysis “excellent.”60 But the VSSG studies illustrated just how fragile those “control” gains could be, especially in the face of exogenous shocks like Communist offensives. They also took a pessimistic view of future trends, and dismissed the idea that nation building as it was understood by many Americans on the ground in South Vietnam—as encouraging the emergence of a rural GVN administration that was considered legitimate by its citizens—could have a meaningful impact on the future course of the war.

The analysis, pointing as it did toward the weakness of the GVN in the event of U.S. withdrawal, can only have hardened Kissinger’s desire for a negotiated settlement that would not amount to a unilateral withdrawal but rather would win concessions from North Vietnam to relieve pressure on the South and allow it to weather the storm of withdrawal. The incursions into Cambodia and Laos also appeared logical within the VSSG framework. They allowed diminishing U.S. forces to be leveraged to maximum effect to disrupt enemy lines of communications and supply caches in a way that further relieved pressure on the GVN and allowed it to consolidate its control gains. The operations also increased the pressure on North Vietnam to negotiate. Thus Nixon’s chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, recorded Kissinger saying that the Laos operation in 1971 “would in effect end the war because it would totally demolish the enemy’s capability.”61 If Haldeman recorded this remark accurately, it was a brief moment of ebullience that soon passed.

The Fragility of Control

According to the VSSG’s “control indicator,” GVN control did indeed expand steadily, standing at 76 percent of the rural population of the country in December 1971.62 But then came the Easter Offensive of March 1972, which dealt just the sort of setback to GVN control that the VSSG had warned of. Although the offensive was eventually beaten back, the damage to GVN control of the rural population was extensive, and only during the declining pace of hostilities following the signing of the Paris Peace Accords did the GVN manage to achieve 74 percent control, still below the level of a year earlier.63 The fragility of GVN control in the face of major enemy offensives had hence been established, especially as the Easter Offensive had been contained only by the extensive deployment of U.S. air and naval assets. This clearly threatened the long-term survival of the GVN, but it was not a surprising situation—indeed, Kissinger had worried about this scenario all along, and it was one reason he had set up the VSSG to provide a comprehensive analysis of the situation in the countryside and the progress of nation building. Thus although the analysis proved prescient, the question remains as to whether it was too narrow and whether the decision to slight the importance of social, economic, and political reform and to regard it as marginal to the GVN’s ability to withstand military attack led to deficiencies in the understanding of the situation in South Vietnam or in Washington’s ability to influence it.

This question arises because of the paradox of the Nixon administration’s Vietnam War policy, which was that even though none of the main policy-making triumvirate—Nixon, Kissinger, and Laird—showed much interest in the reform of South Vietnam, by the time they came into office the role had already been institutionalized under CORDS. As we saw in this chapter, while Kissinger brought in outside experts and set up a sophisticated system for understanding the progress of “the control war,” he did little to intervene in the way it was being run. As we shall see in the next chapter, CORDS had a great deal of autonomy in deciding how to approach nation building in South Vietnam. That this was so is apparent from the fact that CORDS stressed the very reformist measures Kissinger and Nixon underplayed in their approach to the problem of nation building in South Vietnam. Kissinger and the VSSG recognized that the GVN had to expand its control of the rural population and to generate the manpower and revenues necessary to defend South Vietnam from the Vietnamese Communist movement, but did not believe that reform measures aimed at actively generating support for the GVN were particularly consequential. They hence stressed only one part of the equation of mutual obligation between the GVN and its citizens, which Helms had referred to when he called for creating a “motivated population, not merely an administered one.” This was an idea that Colby and other CORDS officials had taken to heart, even if Nixon and Kissinger had not. Using the autonomy they had gained under Johnson, CORDS officials were able to implement their ideas in the latter years of the war. Even though Kissinger and Nixon remained uninterested and even largely unaware of it, Americans in South Vietnam were attempting a nation-building effort of ambitious scope. The question that remained was whether they would be successful and could prove the skepticism of their superiors in the White House to be invalid.