6

CORDS and the Village System

Back on the ground in South Vietnam, the sun rose over a changed war on January 31, the anniversary of the beginning of the 1968 offensives. Unable to summon anything like their effort a year earlier, the Communist movement stepped up artillery strikes and terror attacks on urban centers. Five rockets landed in Hue, and bombs killed two girls near a school in Saigon. About fifty miles northwest of the city, near the Cambodian border, the U.S. First Cavalry Division were busy operating in a Communist base area that they had previously been unable to penetrate. After driving off the rear-echelon forces who were left to guard it, they discovered a tunnel complex covering four square miles and containing a three-thousand-bed hospital. Large formations of NVA had been forced to disperse under the American pressure, and a counterattack they launched on a nearby First Cav firebase was easily repulsed. Meanwhile, deep in the Mekong Delta near the town of Can Tho, American B-52 bombers unloaded one thousand tons of explosives on “suspected enemy troop concentrations,” bringing terror to the countryside.1

These events presented a microcosm of the war over the next several years. Recovering their poise in late 1968 and taking advantage of the failure of Hanoi’s offensives, U.S. and ARVN forces had swept out into the countryside like never before, drastically expanding the GVN-controlled area. Reeling from their losses in the 1968 offensives, the Communist movement was forced to break down its large units into smaller and smaller pieces in order to avoid American sweeps. Lacking the freedom of movement they had enjoyed for years and with even their base areas under pressure, they risked becoming targets for devastating displays of American firepower when they massed for assaults. They were increasingly unable to deter the allies from operating in the former “liberated areas,” leaving the NLF’s local and regional guerrillas and cadres vulnerable. At the same time, U.S. and ARVN counteroffensives were saturating parts of the country with a tremendous amount of firepower, causing civilian casualties on a scale hitherto unknown in some populated areas. In one well-documented case, the U.S. Ninth Division, which became the first U.S. unit of its size to operate in the delta during the entire war, claimed 10,889 enemy killed in one operation, but recovered only 748 weapons, suggesting there were a large number of civilians among the dead. Attempting to escape this indiscriminate bombardment of Communist-controlled zones, a sizable number of civilians relocated to areas dominated by the GVN, further depriving the revolutionary movement of manpower and resources.

These military operations rapidly increased the number of civilians who were living in areas that were secure in the narrow sense defined by the VSSG studies of the Nixon administration. The attrition of the Communist movement’s political as well as its military apparatus, along with population movements occasioned by allied firepower, loosened the movement’s grip on the population in much of the delta to its lowest ebb of the entire conflict. In its traditional strongholds on the central coast, the movement was stronger, but still on the defensive in a manner it had not been prior to the military debacle of 1968.

These shifts in the dynamics of the war coincided with the emergence of a new CORDS leadership determined to take advantage of the situation, along with Thieu’s consolidation of power, to translate temporary security gains into a genuine long-term strengthening of the GVN. Headed by William Colby, the group had all been sharply critical of the way the war was fought prior to 1968. They favored a new strategy that would minimize the role of the military’s firepower and divisions and stress nation building in the rural villages, just as the Communist movement did. Though these individuals often found themselves working at cross-purposes to the military units providing the security shield on which their efforts depended, the final years of the war presented them the most favorable conditions in which to attempt their approach. Their ideas came to dominate CORDS and determine the shape of U.S. nation-building efforts.

CORDS’s Strategy for Rural Reform, 1969–1972

Since CORDS’s formation by Komer, its officials had believed that the absence of large enemy units was a vital prerequisite to nation building. The Communist movement’s travails after the 1968 offensives created the most permissive environment for U.S. forces to operate in since 1965 and made it much easier to keep NLF and NVA units away from populated areas. Colby told the Senate in 1970 that it had been “amply proven” that CORDS’s programs could not be effective “unless hostile regiments and divisions are kept away.” But he added: “At the same time, however, we have found that their absence does not thereby produce peace nor offer political fulfilment to the people.” Representing the “CIA school” of nation building that had been present in South Vietnam since the early 1960s but marginalized when CORDS was headed by Komer, Colby had definite ideas about how to offer “political fulfilment” of a sort that he hoped would allow the GVN to build a base of support comparable to that of the Communists.2

Prior to becoming the head of CORDS, Colby had spent decades in the CIA, including a term as chief of station in Saigon in the early 1960s. He had believed that neither the military’s focus on training the ARVN to fight an offensive war nor the State Department’s concern with liberalizing the Diem regime held the key to the conflict. A conventionally oriented ARVN would struggle against guerrillas, and a liberalization of the Diem regime to include other nationalist factions meant little to villagers who rarely left their own district. The key to the conflict, he thought, “would be found only in the villages, not in political circles in Saigon or in General Staff Headquarters.”3 Colby was not in a policy-making role in the early years of American involvement, and he later spoke with deep regret about how the correct “counter to revolutionary war” was developed by CORDS only long after the war had already been Americanized.4 He had watched the escalation of the conflict under Johnson with alarm, and continued to believe that true victory lay in the GVN involving South Vietnam’s rural population in a collaborative effort against the Communists—that is, in nation building. He was concerned like many of his agency colleagues that the militarization of nation building under CORDS would undermine the need for “some degree of engagement by the population as shown by a willingness to contribute to intelligence, local security and community development.” He further warned of an “impatient desire on our part to impose ‘pacification’ and security on the population rather than engaging in a common effort.”5

Although concerned about nation building being placed under military leadership, Colby eventually came to see how CORDS could be turned to his advantage—provided it was kept under operational civilian control. After going to Saigon to become Komer’s deputy in 1967, he saw how CORDS’s sandwich structure of management in fact allowed for wide discretion in the running of the organization by its civilian head. He even came to appreciate Komer. “Komer knew that if you put pacification under the military it would be lost, because the military would go out and shoot everybody,” Colby explained to Chau. “But Komer also understood that the military would never accept anything but unity of command. Therefore the only way to make it work was to put pacification under the military, in civilian hands. He had the genius to see that.”6

CORDS was now in Colby’s very own hands, and, as he put it in the memoirs, he finally “had the chance to try out my idea that political development from the ground up was really the central part of winning a people’s war, and not just a supplement to the military and territorial-force part.”7 Colby’s tenure also saw the ascendancy of a certain faction of other like-minded officials who shared his approach to the war. This group, including Colby’s deputy George Jacobson, John Paul Vann—who under Colby served as head of CORDS in the delta and later the top American adviser in II Corps—and his policy chief Clay McManaway, made a sizable imprint on the war effort. Theirs was a collaborative effort that built on what they had learned during their many years in Vietnam. An internal CORDS assessment written in June 1969 put it this way: “The 1969 pacification plan represents the culmination to date of progressive developments in the techniques of attaining Vietnamese popular identification with the Government of Vietnam and a concurrent increase in control of the government over its population.”8 But this was an understatement. Rather than just being an incremental progression of what had come before, Colby’s focus on building mutual ties of obligation between the GVN and its citizens transformed the character of U.S. nation-building efforts after 1968.

Since the early 1960s, Colby believed the key to the war was building up the civil institutions of the GVN at the lowest level rather than militarily defeating the Communist movement. The inspiration for his schemes came not from American modernization theorists, of whom he seldom if ever talked, but rather from what he understood of the practice of the Vietnamese Communist movement. Colby’s interest in the techniques of the Communist movement dated back at least to his time as chief of station in Saigon in the early 1960s, when he spent long hours discussing revolutionary warfare with former president Diem’s brother Ngo Dinh Nhu, who shared the fascination.9

As Colby told a military audience in 1971, he believed that the basis of “revolutionary war” as fought by the Vietnamese Communists was “the organization of the people and the use of the people.”10 Colby believed that the success of the Vietnamese Communist movement depended on their superior ability to motivate and organize the rural population in support of their movement, and that the GVN had to replicate this success to survive. The Vietnamese Communist movement engaged in what he called “political development from the ground up,” mobilizing the rural population into functional groups focused on discrete tasks such as intelligence gathering, land reform, women’s affairs, and youth activities.11 Colby understood that Communist rule was a participatory experience for the villagers, creating a sense of political identification between them and the movement for which they worked, against their shared enemy in the Saigon regime. This not only provided a means for the NLF to control the population; it also created a sense of joint enterprise. Colby wanted the GVN to organize the population in a similar way, believing that successfully replicating this Communist practice was key to the war effort. Vann had likewise come to believe in the importance of the “organization of the population” through his long association with Chau, and became an enthusiastic backer of Colby’s ideas.12

The approach to nation building that CORDS advanced during Colby’s tenure reflected this, although Colby favored the word “participation” (of the people) over the term “use.” “The war cannot be won,” he repeatedly said, “unless the people participate.”13 Rejecting the attempt to impose nation building from the top down, Colby instead wanted to build a nation from the bottom up by focusing on what he called the “three selfs”—“self-development, self-government and self-defense.”14 From the Accelerated Pacification Campaign (APC) onward, CORDS sought to actively involve the country’s rural citizens in the running of their own affairs under the auspices of local GVN authorities. This did not require the construction of a sense of South Vietnamese nationhood and patriotism, which had thus far proven elusive. Instead, like the Communist movement, CORDS aimed to engage with the rural population not as citizens of a wider entity called South Vietnam but instead as citizens of their home village. Like the NLF, they would stress concrete reforms and social empowerment that had an immediate and tangible impact on villagers’ lives within their own sphere of interest in the village. Doing so would give rural citizens a stake in defending the new village order, in paying their taxes promptly and volunteering for service in the local militia. This focus on the village also chimed with Vietnamese tradition. As a GVN strategic plan for 1970 observed, the village was “the traditional community in Vietnamese society.”15 The village had indeed been the central unit of Vietnamese rural life since the time of the Chinese conquest, and since Viet colonizers had first moved onto the central plains and Mekong Delta centuries afterward. As with the Communists who had based their own system of administration and mobilization on the village, the new strategy would require a blend of “relevant tradition and necessary innovation.”16 Appropriately enough, the Americans called their innovation “the village system.”

This approach was one that Jeffrey Race, in his classic analysis of the Vietnamese Communist movement, called “communalism.” The movement’s effort, he said, was “communal in the sense that it took place within the framework of the peasant’s span of interests, largely limited to issues within his own community.” The loyalty of the population to the movement was based on its ability to “resolve concrete local issues … [such as] land, taxation, protection from impressment into the national army, or a personally satisfying role in the activities of the community.” Race found in his extensive research in the province of Long An that nationalism as such was rarely a motivating theme for villagers. Rather, it was defense of the local order in their village, plus the direction of Communist leadership cadres whose job was to ensure the village acted in the strategic interests of the movement, that led peasants to give service to the NLF. This was the beginning of the conveyor belt that allowed the movement to mobilize the population and transmit taxes, food, and manpower to the higher levels. Race criticized GVN efforts to mobilize the rural population for focusing on nationalism and a “diffuse anticommunism,” for which peasants were unwilling to make sacrifices in their personal interests.17 While a strident and highly centralized South Vietnamese nationalism did indeed mark Diem’s nation-building efforts, after 1968 CORDS attempted to work with the GVN to foster something different. The village system was based on a vision of rural communities that was remarkably similar to the bottom-up approach pursued by the Communists. “Rather than considering it the lowest of a series of bureaucratic levels through which authority descends from the Palace to the people,” Colby claimed in 1970, “it became the first assemblage of the population to conduct its own affairs.”18

In its broad outlines, the village system drew on a wider discourse of colonial counterinsurgency among Westerners who had fought movements similar to the NLF in Malaya, Algeria, and colonial Indochina. All of these theorists believed that conventional military operations were useless or downright harmful in such conflicts, and that the organization and motivation of the population was the key to victory. Sir Robert Thompson was the most prominent. He had earned his reputation in Malaya as, according to the British magazine the New Statesman, “the world’s leading counter-insurgency expert.”19 Although he could sometimes be blind to the differences between the situation in Vietnam and that which had pertained in Malaya, Thompson drew some lessons from his earlier career that chimed with Colby’s thinking. Like Colby, Thompson was critical of the role played by the U.S. military in South Vietnam after the Americanization of the conflict, believing that its heavy use of firepower alienated the population. Meanwhile, the United States had shortchanged the only thing that could ultimately give them an exit strategy from the conflict: nation building. In a book published in 1969, Thompson wrote that “the problem in Vietnam was, and still is, that of government in its broadest sense and of organization, both in the military and civilian administrative structure.” It was a problem, he claimed, that the Americans had hitherto “refrained from tackling.”20 Thompson viewed the Revolutionary Development program and its parapolitics as a “pathetic” gimmick that ignored the need to reform the regular GVN bureaucracy.21 Although he had an authoritarian streak, Thompson agreed with the necessity of involving the rural population in the effort rather than simply imposing outside solutions on them. During his time in Malaya, Thompson had believed that a nation-building effort had “to involve the people” as well as government institutions.22 Similarly, in Vietnam, he believed that only the South Vietnamese villagers themselves could bring about victory. But an administrative “machine” had to be created in the villages to discipline their efforts and lead them there, just as the Communists created their own organizational machine to both mobilize and control the population.23

In Thompson’s view, there were three main components to the U.S. effort in Vietnam. The most important was “nation building,” which was the “offensive constructive programme” that strengthened the GVN and eventually set the conditions in which U.S. withdrawal could take place. Military operations, the second component, were defensive in nature and designed to hold off the military forces of the Communist movement while nation building proceeded. “The programme which linked these two together was pacification,” he remarked, “because on the one hand it was designed to restore governmental control throughout the country and to establish a permanent link between the central government and the villages and, on the other hand, to destroy the hold which the Vietcong’s political underground organization had on the population.”24 Pacification—the third component—allowed for the clearing away of the organizational infrastructure of the Vietnamese Communists. It also brought the GVN into contact with the rural population. But pacification alone was not enough. Nation building meant building permanent links between the GVN and its citizens. The strengthening of village governments, local militias, and village police would allow the GVN to organize and control the population and preclude the Vietnamese Communist movement from doing the same. Thompson believed that it was this nation-building element that the Americans had given short shrift, as they had been too focused on the mere territorial control implied by “pacification.”25

Other European writers agreed with Thompson, particularly veterans of France’s war in Indochina.26 Bernard Fall was a prominent French war correspondent and academic who had arrived in French Indochina in 1953 to carry out research into the war there. Fall likewise saw a stark difference between “pacification” and the establishment of durable ties between the central government and the rural population. Noting that “to the last breath a government will try to collect taxes,” Fall had checked village tax rolls in areas of the Red River Delta that the French claimed were pacified and found that most of the population of the delta was not paying taxes. He similarly discovered that although village schoolteachers were supposedly assigned by the central government, there were large areas in which they were not present. Even though the entire area was inside a large French military cordon, he concluded that the central government could not be said to have an administrative presence in about 70 percent of the delta. This lack of administrative and political links between the central government and the villages was what allowed the Viet Minh “to take over a country under our feet” by bringing the rural population under its own administration. As he wrote in a U.S. military journal in 1965, Fall believed that “when a country is being subverted it is not being outfought; it is being out-administered.” If the Americans were going to avoid losing in Vietnam, they would have to avoid the same fate. “The question in my mind is this,” wrote Fall. “Can we in Viet-Nam, or anywhere else, save (or improve) the administrative or governmental structure?” Only by extending government administration into the villages, where the bulk of the population resided, could the Americans win the war.27

Fall in turn drew on the works of Roger Trinquier, a veteran of the French wars in both Indochina and Algeria. In 1962, Trinquier published his book Modern Warfare, in which he synthesized the experiences he and many other French officers had drawn from these two conflicts. Like Colby, Thompson, and Fall—who wrote the introduction to an English translation of Modern Warfare—Trinquier was critical of the traditional military establishment. He wrote that “our military machine reminds one of a pile driver attempting to crush a fly, indefatigably persisting in repeating its efforts.” The key to winning what he termed modern wars—by which he meant counter-guerrilla campaigns that required nation building—was not firepower but the organization of the populace. It was not necessary, he held, to have “the sympathy of the majority of the population in order to rule them. The right organization can turn the trick.” He believed that groups like the NLF derived their success from a “specially adapted organization” that allowed them to mobilize the population to provide them with manpower, supplies, and intelligence. Neither Thompson nor Trinquier was myopic enough to totally dismiss the fact that groups like the NLF enjoyed popular support. But they believed that a more salient factor was that the government had ceded control of village organization and administration to the insurgents.28 Like Thompson, Fall and Trinquier advocated spreading central government control over rural areas, uprooting the local infrastructure of the Vietnamese Communist movement, and then building up a pro-government infrastructure from below. They referred to this process by the French term quadrillage, or “gridding.”29 Only by dismantling the enemy’s political and administrative infrastructure and constructing a “similar organization” on the government side could the GVN hope to triumph.30 This required the establishment of a governmental presence in the villages and the mobilization of the population into pro-government militias and political organizations.

This all implied a renewed focus on the village itself. South Vietnam was a unitary state whose constitution provided that power was vested in the villages in a manner of the central state’s choosing. The village was the lowest rung of the GVN that was allowed to make a budget, levy taxes, and own property, and was therefore considered by the GVN to be “the basic echelon of rural administration.”31 This legal standing made it able to become the basis for a lasting devolution and decentralization of power.32 As the GVN’s 1969 pacification plan explained, this would “ensure lasting success.”33 The cornerstone of the village system was “a decentralization of some degree of power to the population in order to stimulate them and invite them into … participation.”34 In turn, this was based on the idea of the “three selfs.” Through “self-government,” villagers would be able to elect their own village leaders. “Self-development” entailed the provision of central government material aid to the village administrations so that they could, at least in theory, respond to the need of their constituents. “Self-defense” programs aimed to raise local militia who would defend the village against small Communist units and free up the ARVN to take the place of departing American forces. The village system tied together numerous strands of American nation-building thinking—the materialist, the security-oriented, and the participative.

The focus, though, was definitely on the latter. The self-government, self-defense, and self-development programs were designed to create a mesh of organizations in each village that would structure and direct the energies of the population in the service of the GVN and against the NLF. In 1969, Thompson had critiqued the nation-building effort to date for allowing the GVN’s “administrative organization … to decay while the corresponding Vietcong asset was allowed to flourish.” This had allowed the Vietnamese Communist movement greater success at “harvesting the surplus energy, manpower and production of the South Vietnamese people.”35 The village system was designed to change that. Just as Thompson, Fall, and Trinquier recommended, the pro-government administrative structure at village level would match and—it was hoped—ultimately displace the NLF’s own structure. Summing up the new American nation-building thrust in 1969, McManaway wrote that “the PSDF [People’s Self-Defense Force], village self development, and village administration programs are directly aimed at building an organizational structure within which political activity can flourish. Our ‘rural political strategy’ … is to get as many people as possible affiliated in some kind of organization—whether para-military, economic, social, youth, or political—using self-interest as the incentive.”36 Just as CORDS used the GVN’s own self-interest in mobilizing rural resources to persuade Saigon to adopt reforms, so the reforms themselves aimed to use the decentralization of power to villagers to convince them that their own self-interest lay with the Saigon government.

Building up the capacities of the GVN in the villages also meant progress on another issue on which Colby and the European theorists were in agreement: the importance of reducing the military’s role. From the vantage point of a memoir written decades later, Thompson would criticize the United States and the GVN for a tendency to militarize civil functions, and contrast the situation unfavorably with Malaya. “In Malaya the army supported the civil power during an ‘emergency,’ ” he wrote, “but in Vietnam the civil power, where it existed, supported the army in a war.”37 Trinquier, Fall, and Colby also believed that large-unit sweeps and heavy firepower were counterproductive. Instead, the village system was designed to eventually allow the burden of the war to be shifted onto locally raised militias and village governments. As Vann explained, overreliance on the military led to what was effectively an “occupation” of rural areas by a GVN and ARVN administration imposed from the outside. This was not only unlikely to elicit the active support of the population, but also inevitably allowed the NLF to reemerge when government forces moved on.38 “Without an overt commitment from the population in favor of GVN objectives,” read policy guidance written in 1971, “pacification is hardly distinguishable from military occupation.”39

Though the military occupation of rural areas and the driving out of large Communist units constituted a first step, the village system was designed to translate these short-term gains at pacification into durable nation building. According to Vann, “the willing cooperation of the people with their government because they believe it will be in their own self-interest,” along with the rejection of the NLF, would allow the GVN to withdraw its military forces from an area sometime after the initial “occupation.” This was a vital facet of the village system at a time when Vietnamization was reducing the number of U.S. forces who were able to provide a security shield behind which nation building could take place, meaning that the ARVN would have more tasks to accomplish with declining resources. By contrast, the active participation of the population meant that “a relatively smaller number of armed men, more centrally located, can respond to the warnings or ‘intelligence’ given by a watchful loyal population.”40

The opportunity to implement the village system arose in part because declining violence across South Vietnam between 1968 and the Easter Offensive led to a vast improvement in the country’s refugee situation. The number of internally displaced persons recorded in official statistics in South Vietnam peaked in early 1969 at nearly 1.5 million before declining thereafter. In 1969, just over half a million of these refugees returned to their original homes, and another 586,388 were paid resettlement allowances by the GVN to allow them to move somewhere else.41 At the same time, the practice of forcibly relocating civilians during military operations was increasingly discouraged by both the United States and Thieu. In January 1968, Westmoreland had noted that the allies had two basic options to isolate the civilian population from the NLF. “Either the communists and their political control must be driven from the populated areas and security provided to keep them out,” he wrote, “or the people must be relocated into areas that will facilitate security and prevent communist control apparatus from re-entering the community.” While the first course of action was “preferred,” it was also “time-consuming and expensive.”42 Civilians had therefore often been forcibly moved to areas of GVN control from the time of the Strategic Hamlet Program under Diem. The resentment and disruption this caused undermined attempts by the GVN to build a positive relationship with its rural citizens. Recognizing this, from 1969 onward Thieu and Colby repeated the mantra that security should be brought to the people rather than the people to security.43 As GVN territorial control spread and the pace of military operations in populated areas declined, huge numbers of rural citizens returned to their villages. This made it possible for the village system to be implemented on a scale that would have been impossible during the chaotic and fluid environment before the 1968 offensives.

In the context of wider U.S. policy under Nixon, the village system represented the civil side of Vietnamization. In fact, as one briefer noted in 1971, CORDS had been involved in a process of Vietnamization ever since its creation in 1967.44 Official policy guidance on Vietnamization sent out by Colby and General Creighton Abrams in 1971 asserted that “the nub of the policy is assistance and support of the Vietnamese constitutional structure to build the strength necessary to sustain itself in the future against the external and internal problems it will face.”45 Vietnamization also placed new pressures on the GVN. The U.S. involvement in South Vietnam was now time-limited, subject to political pressures in the United States. GVN leaders likewise realized that they would increasingly have to rely on their own resources to run South Vietnam and keep the Communists at bay as American forces and monetary assistance were withdrawn. As an American government economist who studied South Vietnam intensively for USAID argued, since 1965 the GVN had pursued a policy of relying on foreign resources to fight the Communists rather than mobilizing domestic assets.46 Both the American combat troops fighting for Saigon and the American aid dollars flowing into its coffers attested to this. With the onset of Vietnamization, Thieu and his allies in Saigon realized that there was a need for their government not only to spread its control of the rural population but also to harness the assets of rural South Vietnam—its manpower and economic resources—to bolster itself for a time when it would have to rely much more on its own resources.

The GVN and the Village System

The village system represented a blending of American and Vietnamese thinking on political organization and revolutionary war in South Vietnam. But the Vietnamese figures whom Americans like Colby and Vann had learned from were not mainstream ARVN province chiefs or GVN politicians, but mavericks and outsiders like Chau. In turn, Chau had based his thinking on the example of the Vietnamese Communist movement and his own time in the Viet Minh. Much of what he taught went against the entrenched interests and worldview of the urban class who staffed the ARVN officer corps and served as provincial and district officials. CORDS advisers who tried to bring about the implementation of the village system were hence always working with and simultaneously against the GVN.

The fate of Chau and Major (later Colonel) Nguyen Be, his successor as head of the Vung Tau center, illustrated the problem. Both were eventually jailed by Thieu, who disliked their independent streaks, opposition to the GVN hierarchy, and closeness to the Americans. A former Viet Minh battalion commander like Chau, Be shared his distaste for the typical province chiefs who were distant from the rural population. Be once told a visiting Vice President Hubert Humphrey that the majority of district chiefs in South Vietnam were corrupt, raising eyebrows from Washington to Saigon.47 Training GVN cadres at Vung Tau, he preached about the evils of landlordism and official corruption in the Vietnamese countryside, as well as the danger of the Communist movement. As can be imagined, these views did not endear him to his fellow officers who staffed the lower levels of the government bureaucracy. Be believed in creating a genuine village democracy, but feared that his program would be diluted or destroyed by entrenched interests in rural government. Thieu was wary of Be, and remarked on at least one occasion that “better educated and more patriotic people—Army people” ought to be put in charge of the RD cadre program that Be was now running.48 Only the fact he was highly regarded by the Americans protected Be from Thieu’s wrath, and Bunker had to head off at least one attempt to fire him.49 Criticizing his own countrymen while enjoying the protection of the Americans placed Be in a tricky position. When American advisers had all left following the Paris Peace Accords, Be was promptly accused of embezzlement, fired, and replaced by a Thieu loyalist.50 Chau, meanwhile, had entered politics as a legislator and become highly critical of Thieu. After being accused of making contact with his brother who was serving in the NLF—hardly an unusual act, given how political loyalties had fractured families across South Vietnam—Chau was imprisoned following a controversial trial.51 Neither example encouraged the emergence of other crusading reformers from within the ARVN or the GVN.

CORDS’s activities in the final years of the conflict involved a complex dance of negotiation and compromise with the GVN at all levels, from Thieu and his ministers in Saigon down to the province and district chiefs with whom field advisers worked. Colby and his lieutenants in Saigon were successful at persuading Thieu and officials in the Ministry of Rural Development to adopt the tenets of the village system, at least in principle. A series of decrees promulgated by the GVN, including a major circular on the reorganization of village government in April 1969, laid the groundwork for the village system.52 Each year afterward until the American withdrawal, ministries in Saigon promulgated large strategic plans that provided instructions for priority rural reforms and the implementation of the village system over the coming year. These documents reflected CORDS’s priorities well, not least because CORDS officials had a heavy hand in writing them.

These plans continued to run into problems when passed to local officials for implementation, reflecting the entrenched difficulty of bringing about reforms at the local level. Some Vietnamese officials such as “Anh” were in sympathy with the aims of the village system and its de-emphasis of the military role. As early as 1967, Anh complained about the pattern of occupation followed by withdrawal that typified “pacification.” Military units would move in, order the people to cooperate with government forces, then “before the village is strong enough they move to another place because they are understrength … leaving the village to the VC again. After such an experience, you can never expect to be successful if you come back the second time.”53 But while NIA-trained officials like Anh were more likely to support the village system, the military-trained province and district officials and corps commanders who held most sway in the countryside would ultimately decide whether implementation of it would be successful. Anh and most civilians like him never rose to the position of province chief, which remained mostly a military prerogative. There was only so far Thieu was able—or wanted—to go in imposing the village system on the military officers who still staffed most of the GVN. Thieu had consolidated his position following the 1968 offensives and had been able to replace a sizable proportion of local leadership. But it was very tricky for him to carry out what amounted to a revolution in local governance while relying on the very officials whose power the revolution would undermine to both carry it out and to keep fighting the war. In the paraphrased words of an American officer, Thieu did not have the luxury of destroying the GVN in order to save it. Nor, as his treatment of Be and Chau showed, was he in total sympathy with the aims of the reformers.

From the 1969 plan onward, the GVN stressed the need to capitalize on the improved security environment to carry out reforms. “We are now stronger than we have ever been, and the enemy is at his weakest period,” exulted the 1969 plan. “Presently, our resources ready to be used in the Pacification Program are larger than ever before.” In rhetoric that echoed Colby’s words about the need for correct technique, it warned that “we may repeat the same mistakes of the past if we do not learn and apply the important Principle of the Community Spirit.” This principle, which recurred frequently in GVN discourse on nation building, called for “cooperation among the people, cooperation between the people and the Government, and cooperation among Government organizations.”54

Although the Community Spirit Principle was compatible with the American concept of the “three selfs,” it tended to stress the responsibility of citizens toward the GVN more than the reverse. In private remarks, top GVN officials also consistently placed more emphasis than CORDS on the fact that the bargain between people and government did not just involve resources and rights flowing downward to the people, but also demanded that they actively assist the GVN. “The important factor here is to instill in the people a sense of responsibility for their community for it is the people themselves who must actively combat the Communists,” Thieu explained in early 1969. “The people must participate in all activities to defend and develop themselves.”55 Along with the Americans, Thieu felt that “the people must be held under GVN control from a political and ideological point of view, not just administrative.”56 Yet it is interesting that he talked of ideological and political control rather than democracy and participation, as the Americans did. According to his aide Nguyen Tien Hung, Thieu and his close advisers believed that Vietnam was not ready for democracy and went along with liberalizing ideas only to maintain American support.57 This made him unwilling to risk too much of his support from the military for the sake of ideas of whose usefulness he was not convinced. Nghiem Dang, the head of the NIA, also placed a greater accent on the control of the population rather than seeking spontaneous commitment. “Whether interest groups are spontaneous or co-ordinated or whether they are organized for the purpose of public control or for population regimentation,” he wrote, “the very fact of their existence shows the extent to which citizens participate in administrative activities.”58 Prime Minister Huong likewise stressed the responsibility of citizens, saying that “the guiding principle of the program was that the people would do more for themselves and that the government would support them.”59 The 1970 plan also took up his theme, stressing on its first page: “All people must understand their mission, their private responsibility, and support the government.”60 As Vietnamization advanced, this point remained pertinent. In fact, it amounted to a matter of the GVN insisting that the burden of Vietnamization would fall on the country’s rural citizenry. With the withdrawal of U.S. military forces, the need for the GVN to enlist the cooperation of its local citizens in national defense only grew stronger. The result was that, as the 1971 plan explained, “a greater share of the burden of defense must be borne locally, by the villagers themselves.”61

On the other hand, Thieu realized that the reforms CORDS pushed were a logical response to Vietnamization because they helped enlist the GVN’s citizens in the common defense. He also appreciated the value of keeping the Americans onside for as long as possible. As Colby explained, Thieu had a particular way of dealing with his American advisers, realizing that “to handle their enthusiasm it was not appropriate to challenge them directly … but it was sensible to accept their ideas rather than reject them and then try to adjust them to make them more practical.” In this way he channeled CORDS’s ideas “to what could practically be accomplished in the real world of Vietnam.”62 Of particular relevance to Thieu was that the village system chimed with his own need to expand the coercive reach of the GVN throughout the South Vietnamese countryside. Thieu and his principal subordinates could see the benefits of enacting reforms in local government to enable them to enlist South Vietnamese citizens in militias and police forces that would help with this goal. Their priorities for the implementation of the village system reflected this. After the war, ARVN chief of staff Cao Van Vien remembered CORDS’s role in raising local militias and police as “by far the most important and outstanding among US contributions” to what he called “pacification.”63 Thieu and many other generals could see the benefits of changes to rural governance that promoted pacification.64 But this did not necessarily mean they had embraced a vision of participative nation building.

Nor did it mean Thieu had become a mere puppet of the Americans. Thieu and his principal allies in the GVN might see the benefit in the broad outlines of the village system, but they were by no means prepared to go along with a clean sweep of rural administration. Like every South Vietnamese leader since Diem who had stacked the localities with his own allies, Thieu’s consolidation of power gave him an interest in protecting the structure he had established. By 1970, he was becoming less susceptible to American advice about the hiring and firing of province chiefs.65 Frank Scotton, who during these years was working for Colby on the case files of officials suspected of corruption, could not remember one case, from 1970 to 1972, of the United States managing to have a senior official removed.66 Thieu’s growing distrust and paranoia as the war wound down made him seem increasingly distant in the final years of the American presence. On Kissinger’s first visit to South Vietnam, he met with opposition leaders as well as making a trip to the Presidential Palace, which Thieu took as a disturbing indication that Washington was still keeping eggs in more than one basket. According to Hung, he even put forces on alert against a possible coup. Thieu also suggested that Americans whipped up debates against his regime, claiming, “Any time the American ambassador came to see me and asked me to do something and I refused, you could count two weeks before the demonstrations erupted.”67

Yet it was clearly out of the question for Thieu to break with the Americans, and he sought to pursue what he called a “long haul / low cost” strategy to keep the United States engaged as long as possible.68 In different ways, Vietnamization and the village system both allowed for the GVN to reduce the cost of U.S. involvement in the conflict, thus allowing the United States to engage for a longer period. The support of CORDS, which had aimed from the beginning to build the capacities of the GVN to the point that it could exist independently of American support, was naturally vital to this process. Thieu’s goals were to squeeze as much support out of the Americans as possible while keeping one eye on the time when the Americans would be gone and he would have to rely on his own political base to stand up to the Communist movement. “I know that you are going to go, but before you go, you have to leave something for us as friends,” he told Nixon at Midway. “Leave something to help me out.”69

From Pacification to Nation Building?

The first major post-Tet initiative undertaken by CORDS was the Accelerated Pacification Program (APC). As Komer later explained, the APC was a “highly simplified” program whose purpose was to get GVN forces back out into the countryside to reestablish a minimal government presence. The aim was to organize pro-GVN militias, install a GVN hamlet government—preferably by election, but by appointment if the security situation did not permit it—and to carry out one local development project in each target hamlet. Over thirteen hundred hamlets were eventually targeted.70 The APC benefited from close coordination with large U.S. military units and their heavy firepower, which operated to screen target hamlets from overt attack and separate cadres and guerrillas from villagers. At Colby’s insistence, the APC focused on the Mekong Delta, where some six million South Vietnamese lived. It was also the area where MACV believed that the NLF was still at its strongest, an anomaly given that 70 percent of the enemy’s combat and combat support strength in South Vietnam was assessed as being NVA by early 1969.71

CORDS officials conceived of the APC as the first step before they could move to implement the village system. It was the necessary pacification, or “occupation,” element of establishing control over the countryside before genuine nation building could be attempted. Vann, now head of CORDS in the delta, saw the APC as a process of a “fast and thin” expansion of GVN control aimed at “unwrapping the GVN from around the province and district flagpoles they had clustered to during the 1968 Tet offensive.”72 Colonel Robert M. Montague, Komer’s military aide, later described the APC as a “once-over-lightly” whose goal was “to show the government’s flag.”73 CORDS officials also hoped that the APC would focus the minds of GVN local government on the problem of expanding control of the rural population. Under the plan, district chiefs were required to visit target hamlets once a week, and village chiefs were required to visit them three times a week.74 Furthermore, in Colby’s words, “the arrival of government force and authority was accompanied by some immediate impact project such as a school.” Although in the past these material projects had usually been assessed as having little impact on villager loyalty or motivation (a fact Colby did not mention, but was aware of), it was hoped they would “give an immediate visible indication of government presence, benevolence, and intention to stay.”75

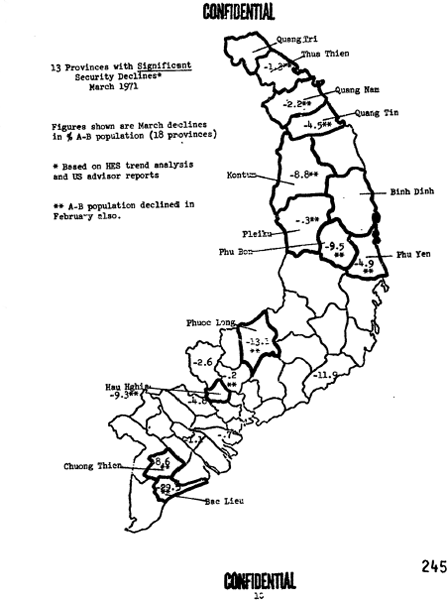

Figure 8. Deterioration in pacification in eight provinces as measured by HES, August 1970–August 1971. Thomas C. Thayer, ed., A Systems Analysis View of the Vietnam War, 1965–1972, vol. 9, Population Security (Washington, DC: OASD(SA)RP Southeast Asia Intelligence Division, 1975), 251.

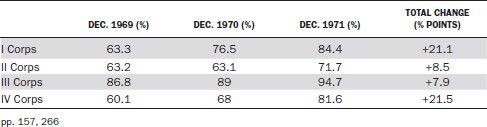

Measuring the impact of such intangibles was difficult, but the APC inaugurated a period of almost uninterrupted gains in government control of the countryside, which lasted until the Easter Offensive of 1972. According to Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) figures, some 1.6 million more Vietnamese were living in rural areas classified as secure when the APC came to an end at the beginning of February.76 Elections were held in 41 percent of the targeted hamlets, and 170,000 weapons were distributed to local militia.77 While the number of weapons distributed was easy to measure, CORDS officials were more cautious about the other figures. Given pressures to succeed and the subjective nature of the HES figures, Colby was careful not to read too much into them. “Some of the statistics … we thought were fairly soft, to put it mildly,” Colby later wrote. He considered reports of 1.1 million recruited to the People’s Self-Defense Force, with four hundred thousand trained, to be particularly risible.78 Bunker cabled Washington that while the HES numbers were “sometimes questioned,” their value lay in giving a “definite reflection of the trend.”79 One reason to believe that the figures were at least useful for establishing a trend was that HES ratings had tracked sharply downward following the Tet Offensive, showing that the system also measured setbacks.80 The HES system also continued to measure localized setbacks despite the broad pattern of increasingly positive results between 1968 and 1972. By the summer of 1971, the HES system was showing some 77 percent of South Vietnam’s population were living under government control, but also showed that a sharp deterioration had taken place in eight provinces since the previous summer. This deterioration, depicted in figure 8, vindicated HES’s usefulness as a tool that measured setbacks as well as trumpeted victories, but also carried an underlying warning about the fragility of apparent gains in the face of increased enemy activity.81 Top CORDS officials such as Colby were aware of this, and therefore treated the overall HES trends (shown in table 3) with skepticism. In the words of Willard E. Chambers, a high-ranking CORDS official in Saigon, South Vietnam in late 1971 was “pockmarked with areas where both advisors and their counterparts are suffering from a euphoria which the VC could negate overnight.”82

Table 3. Percentage of population living in hamlets with security rated “A” or “B” by HES, 1968–1971

Even if the impressive HES figures in table 3 are taken at face value, Colby and his team knew they did not necessarily represent a success at the more intangible task of nation building. This was clear even in the immediate aftermath of the APC. In September 1969, CORDS’s Pacification Studies Group (PSG) carried out an assessment of security in a village in Phu Yen Province whose HES ratings indicated it was secure. They found that the RD cadre and territorial forces who were supposed to be keeping the village free of enemy influence were in fact “submissively cowed to the point where contact is avoided when possible.” The lack of security incidents in the village was due to the fact that the enemy forces who dominated it did not want to draw attention to the village and have their freedom of movement disrupted.83 Vann had warned earlier in the year that large areas of the Mekong Delta may have appeared more secure than they were because the NLF was quietly governing areas and harnessing their resources in ways that fell below the GVN and U.S. radar.84 As we saw in the last chapter, the Nixon White House had reached similar conclusions about the limited optimism that could be derived about the true progress of nation building from a mere absence of violence. For Colby, the Phu Yen report reinforced what he had long known. “When we started the APC we said that our objective was to expand government authority ‘thin and fast,’ ” he wrote in response. “It is quite apparent that that is exactly what occurred. The government presence in this area is a thin veneer indeed.”85 It was clear that establishing a governmental presence in the countryside under the APC was only the beginning of nation building; establishing mutual bonds of obligation between the GVN and the people, and thus transitioning from “occupation” to true nation building, was longer and more nebulous work. As MACV believed that the lack of serious enemy opposition had been the main reason the APC has been successful, nation building would also be reliant on continued cooperation by the enemy.86 The serious deterioration that took place in Phu Yen shortly afterward (see figure 8) showed what could occur when such cooperation was not forthcoming.

As GVN control of the rural population spread, CORDS advisers and higher officials in Saigon began to grapple with the much thornier problem of implementing the village system. As one of Vann’s subordinates in the Mekong Delta argued in a think piece he wrote for his boss, now that the GVN was in “direct contact with the six million people of the Delta” it was time to capitalize on the “momentum in military security” and “parallel that effort with a political effort.”87 This political effort was intended to move beyond the mere “occupation” of rural South Vietnam and instead to implement the “three selfs.” This proved a far more difficult task. The shift from quantitative targets based on improving security to qualitative ones based on political development raised a host of problems that advisers had to struggle with. In a candid assessment for Bunker in July 1970, Colby said that “the novelty and excitement of expanding into new territories” had been “followed by the comparative drudgery and inconclusiveness of improving performance, remaining alert, and wrestling with fundamental economic and social problems.”88 These thorny problems would consume the efforts of American nation builders until the end of U.S. involvement in South Vietnam.