Chapter 1

SPECULATIVE PRODUCERS

The Production of Korean Drama

Korean television dramas are known for a typical narrative structure that appeals to a primarily East Asian audience, but also, more recently, a global audience. Thus, textual analyses to examine “the kind of stories that are told in Korean TV dramas” have dominated Hallyu studies. This chapter redirects attention to the industrial arena and analyzes “why such stories are told in particular ways.” More important, rather than accounting for the popularity of Korean dramas, I examine how Hallyu has reconfigured their industrial dynamics and production practices. I argue that the Korean Wave has turned the Korean drama industry into a speculative field in which the industrial players have vested interests in export. The unexpected performance of some Korean television dramas in foreign markets in the early 2000s caused a sudden proliferation of independent drama producers. Despite their sizable numbers and mounting expectations of achieving a megahit in foreign markets, the independent producers’ industrial positions are marginal on account of their being exploited by the broadcasters’ monopolistic power. Their suppressed status causes independent producers to engage in even more speculative practices, pushing them to seek more and more sponsors. This chapter illustrates how the speculative nature of their business has, in turn, affected the production practices, forms of sponsorship, and storytelling methods typical of Korean television dramas. The focus of the analyses will be to show how K-drama narratives are commercially crafted to attract sponsors and do well in export markets.

Hallyu and the Growth of Independent Producers

Under the military dictatorship that ruled South Korea until the 1980s, the central state monopolized the country’s broadcasting system through the direct control of two broadcasting channels, KBS (Korean Broadcasting System) and MBC (Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation). As public networks, the two stations produced virtually all television dramas and their in-house crews constituted the labor force in drama production. The country’s democratization in the late 1980s, albeit superficial in nature, fostered a growing societal interest in mass culture that allowed the private sector to establish commercial stations. Korea’s first commercial channel, SBS (Seoul Broadcasting System), was launched in 1991. As a newcomer to the industry, SBS’s market position was weak compared with its two already established competitors.1 To make up for SBS’s weak self-production capabilities, the 1990 Broadcasting Act set up a new “independent production quota system (oejujejak uimu pyeonseong jedo)” requiring the three terrestrial stations to air a certain proportion of content produced outside the broadcasting firms.2 The new regulation was designed to check the monopolistic power of broadcasters, diversify content producers, foster the broadcasting content market, and enhance services for the audience. Broadcasters assigned the bulk of the mandatory quota of externally produced material to television dramas because they believed that independent producers would be more flexible and better able to attract funding from various sources, such as investment and sponsorship. Therefore, the new quota system had the effect of gradually shifting drama production from broadcasting stations to independent production companies.

Independent drama producers, then, for the purposes of this book and in view of the circumstances in which they came into being, are production companies that have no access to broadcasting channels of their own on which they can release their products. What matters in defining independent drama producers is their independent status vis-à-vis broadcasters, so they need to secure a contract with a broadcaster to gain access to a channel. The company’s size and the attributes of the products it creates are not what determines its status as an independent drama producer. During the earlier stages (1991–1994), independent producers were often subsidiary companies of broadcasters such as MBC Production and Korea Broadcasting Entertainment System and Technology. Independent production was outsourced from broadcasters, but their in-house management and in-house prototyping virtually controlled all aspects of it. It was only after the mid-1990s, when the new operations of ten regional terrestrial television stations and the introduction of digital multimedia broadcasting (DMB) and Internet-protocol television (IPTV) boosted demand for drama content, that independent producers in a real sense appeared, hoping to sell drama content to these new channel operators. Until the 1990s, however, individual firms that could independently produce drama content were almost nonexistent. Although some high-profile directors at the broadcasting stations launched their own firms, actual production was mostly carried out using the broadcasters’ resources, personnel, and equipment. In addition, credibility and personal connections, not reasonable market values such as price and quality, virtually determined the market transactions in dramas between networks and independent production companies.

What really caused the proliferation of independent drama producers was the unforeseen popularity of Korean dramas during the early 2000s: the drama-driven First Korean Wave. The media liberalization of the 1990s enabled East Asian countries to move away from a defensive attitude toward importing television programming and develop a more active intraregional trade in television programs (Langdale 1997; Shim 2008; Jin 2011). The growing number of regional transactions resulted in some Korean dramas that received recognition overseas. The very first of these pioneering dramas was What Is Love All About (Sarangi Mwogillae 1991), which was broadcast and very popularly received in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China in the late 1990s.3 After a long period during which diplomatic relations between China and South Korea had been severed, the drama series established a new image for Korea. Indeed, it sparked a buzz about Korean popular culture among Chinese-speaking audience groups. After the success of this series, other Korean dramas such as Star in My Heart (Byeoreun Nae Gaseume 1997), Sunflower (Haebaragi 1998), and Goodbye My Love (Annyeong Nae Sarang 1999) were exported to China one after the other. Nevertheless, although the term hanliu/hallyu, meaning “Korean Wave,” was in fact first coined during the late 1990s in the Chinese-speaking areas,4 the impact of Hallyu during that decade remained limited to a series of temporary and local sensations.

It was the drama series Winter Sonata (Gyeoul Yeonga) that created the Korean drama fever in East Asia, exerting a phenomenal influence on and beyond the drama industry. Winter Sonata is a conventional melodrama that was originally aired in Korea in 2002 on KBS. In 2003, BS, a NHK (Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai; Japan Broadcasting Corporation)-owned satellite broadcasting channel, imported and aired the drama series. Completely unexpectedly, it went viral among middle-aged women.5 BS rebroadcast the series by popular demand in early 2004; NHK rebroadcast it on a terrestrial channel later that same year. The actors who appeared in the drama became extraordinarily famous in Japan, and the male lead, Bae Yong-jun, earned the title “Yon-sama” (sama being an honorific suffix). Beyond mere television watching, Winter Sonata became a social phenomenon, causing enormous changes in cultural, economic, and political arenas in both Korea and Japan. NHK reported that the network earned more than ¥9 billion from airing the drama series. Sales of the DVD of the series amounted to more than 450,000 copies in Japan, while more than 60,000 copies were sold of the Winter Sonata Tourism DVDs that covered the locations used in filming the drama. More than 900,000 albums of Winter Sonata Original Soundtrack (OST) were sold, taking top place in the Oricon chart in 2003. Earnings from the drama series in Korea exceeded $5 billion, mainly generated by drama-driven tourism to the filming sites. More than 200 tourism and merchandising products theming Winter Sonata have been developed and sold both in Japan and Korea (KOFICE 2008).

The drama series that has had the greatest impact on the predominantly ethnic-Chinese locations in East Asia is Jewel in the Palace (Dae Jang Geum). This series, which originally aired in 2003 on MBC, is about the first female imperial physician at the time of the Chosun dynasty in the sixteenth century. GTV (Gala Television Corporation) in Taiwan imported and showed the series in 2004, achieving peak ratings of 62.2 percent and second place in the all-time ratings. Backed by this extraordinary popularity, Dae Jang Geum was rerun in 2005. The Dae Jang Geum craze in Taiwan even revitalized the Seoul–Taipei flights that had been stopped following the establishment of relations between China and South Korea in 1992. The series was also screened on TVB (Television Broadcasts Limited) in Hong Kong in 2004 and recorded an average of 47 percent in viewer ratings, putting it in third place in the all-time ratings; the total viewership exceeded 3.21 million, around half of the entire Hong Kong population. Hunan Satellite Television in China aired Dae Jang Geum in 2005 and later broadcast it again at the national level. Since its extraordinary success in East Asia, Dae Jang Geum has made inroads into Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. It has been exported to more than sixty countries, driving the Korean Wave across the globe.6

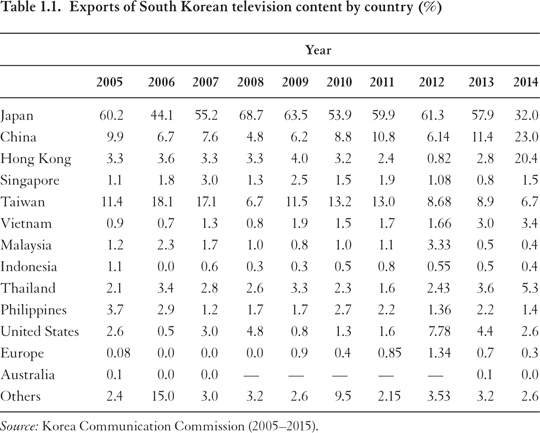

After the astonishing sensation created by these two dramas, more than 500 million dollars’ worth of Korean drama was exported to overseas markets during the period from 2002 to 2013. The proportion of television dramas has continuously increased and now dominates Korean exports of television content. The geographical coverage is also diverse, expanding from East and Southeast Asia to Europe, the Middle East, and Latin America (see table 1.1). The fortuitous overseas visibility acquired by some pioneering dramas and the expansion of the export market has fundamentally changed the Korean drama industry since the 2000s. The emergence of export markets triggered a mushrooming of drama production companies. Some star directors left the networks and started their own production companies, such as Kim Jong Hak Production led by Kim Jong-hak, who directed two stunning dramas, Eyes of Dawn (Yeomyeongui Nundongja 1991) and Sandglass (Moraesigye 1995), and Yoon’s Color launched by Winter Sonata’s Yoon Seok-ho. The growing markets and expectations have also attracted players from various fields into the drama industry. Some music labels entered; Pan Entertainment established itself in the drama industry, earning more than $10 million from Winter Sonata in Japan alone; DSP E&T produced Three Leaf Clover (Seip Keullobeo 2005), My Girl (Mai Geol 2006), and Yeon Gae So Mun (Yeongaesomun 2006). Entertainment agencies also turned into production players; Sidus HQ merged with Castle in the Sky, which had previously produced Lovers in Paris (Pariui Yeonin 2004), and went on to produce Spring Days (Bomnal 2005), Sad Love Story (Seulpeun Yeonga 2005), Only You (Onri Yu 2005), and Princess Lulu (Ruru Gongju 2007). Film production houses expanded their business areas to include television drama production; Popcorn Film, for instance, produced Stranger than Paradise (Cheongukboda Naccseon 2006). Daily Sports, a subsidiary of the media giant JoongAng Daily, launched A Story, which has produced more than twenty dramas, including Air City (Eeo Siti 2007) and Cinderella’s Sister (Sinderella Eonni 2010) (Korea Communication Commission 2007). In sum, riding on the Hallyu wave, the number of drama production companies, as registered under the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, skyrocketed from 331 in 2000 to 1,329 in 2013, yet many of them exist on paper only.7 The number of those that have actually sold their programs to broadcasters increased from 391 in 2008 to 628 in 2011, and 503 in 2013 (Korea Creative Content Agency 2015). The newly established independent production houses also caused big shifts in in-house labor forces. High-profile directors quit their jobs at broadcasting firms and moved to independent companies with big lump sum contract deals, and many filming and lighting crews became freelancers, serving both the production and broadcasting firms.

Marginal Producers

Despite their sizable numbers, the market position of independent production firms is marginal in terms of their lack of autonomy and power vis-à-vis broadcasters. Independent producers become even more marginal because most of them are small sized. What characterizes Korean independent producers is the stark divide between the few major outfits and the mostly small-sized majority. The growth of major independent producers gained momentum during the early 2000s when so-called communication capital flowed into the drama industry.8 By establishing private equity funds and practicing backdoor listing, most of the major producers went public around the mid-2000s.9 Public listing enabled them to find various financial sources to cover megaproduction costs on the one hand, and to generate more profits through the stock market than from content production on the other. Yet the majors that have self-sufficient production and financial capability are limited to less than ten firms among more than fifteen hundred.

Most independent production firms are small, with only small numbers of contracted writers and office staff (who take care of multiple miscellaneous jobs, such as project development, casting, and filming assistance), and sometimes a few contracted directors. Starting up their business with nothing more than connections to broadcasting companies, minor independent production firms are far short of both the human and financial capital required to kick off a production. The strategy for these seemingly name-only production firms is to circulate their drama proposals among the three broadcasting stations in hopes of attracting a channel that will broadcast their drama. Only after a channel is guaranteed do their proposals become tangible and can they start to plan a funding scheme. A network buyer of a soon-to-be-made drama, however, usually offers only around 70 percent of the total production cost,10 and even this insufficient payment is made only after a whole series has been aired, which means four to fifteen months after the initial production stage. Since preparations for the production and funding procurement schemes are already underway, independent firms have to accept the cost settlement proposed by a network. To actually start production and cover the rest of the production costs, therefore, drama producers must attract funding in the form of investments, sponsorships from enterprises or cities, or product placements, or by borrowing that results in debt. As these financial flows show, most independent drama producers jump into the market with buyers’ and investors’ money rather than their own. Although this flexible way of securing a budget lowers the entry barrier to the industry, the unstable financial base contributes to the precarious positioning of most independent drama producers.

To facilitate investment and other forms of funding, producers need heavyweight names in their cast lists. Given the export-oriented nature of the industry, producers particularly prefer Hallyu stars who have already established recognition and popularity in East and Southeast Asia. Yet this star system, which independent producers opt into as a survival strategy, has actually made their situation worse. During the 2000s, the independent production system turned drama production into a market-friendly business that clearly differentiated between star actors and others with less monetary value, causing an unfettered rise in appearance fees for top talent. For example, the maximum guaranteed fee per episode for leading actors began to rise drastically during the early 2000s, breaking through the $10,000 level in 2004 and continuously increasing, reaching around $30,000 to $50,000 in the late 2000s.11 In 2008, to curb the ever-increasing star guarantees, the drama producers’ association created a rule that an actor’s performance fee per episode should not exceed $15,000. Yet the ever-increasing competition for star actors easily nullified that ruling in the late 2000s. Therefore, when independent producers pay $60,000 to $100,000 per episode for actors in the two leading roles, these (two) stars’ guarantees account for as much as 70 to 80 percent of the budget (generally $80,000 to $100,000 per episode) that they receive from broadcasters. Producers are supposed to use the remaining 20 to 30 percent of their budget to pay for other supporting roles, crew, equipment, and on-location shooting. Unless a drama hits the jackpot in terms of audience ratings and attracts more sponsorship during the course of its airings, independent producers end up having to cover the deficits.12

The lack of self-sufficient production capabilities also speaks to the marginality of independent producers. As stated above, only after securing a channel do producers’ proposals become tangible and a substantial production team is established. Most small-sized production firms, however, do not have independent production capabilities. Once a channel is fixed, production firms “rent” personnel (mostly film directors) and equipment from the broadcasting firm. Undertaking a so-called combined production (between a producer and a broadcaster) is also a way of gaining a channel in the intense competition among miscellaneous producers. The actual filming of a drama series is centered on the “leased” director; thus, the voices of independent producers, that is, those who initially proposed the project, become diminished over the course of the actual production process. Moreover, the director provided by the broadcasting firm holds the exclusive right to edit the film, controlling the eventual direction of a drama series and the final product. Under the established precontract and postproduction system, there is extremely limited room for independent producers to exercise their discretion over production matters. For these reasons, significant numbers of independent drama producers in Korea lack, and rarely develop, independent production capabilities.

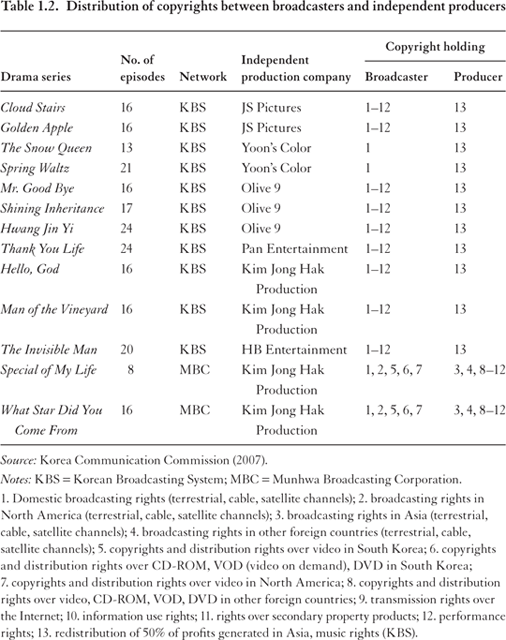

Independent producers’ marginality is also reinforced by the industry’s structure, in which terrestrial channels are limited to only three networks that, naturally, have monopolistic power. Taking advantage of their monopoly on television channels, the three big terrestrial networks usually, with only a few exceptions, force independent producers, by contract, to surrender the copyright to their dramas. Components of the copyright include broadcasting rights in various countries; the right to sell the dramas to second-round channels such as cable and Internet stations; copy and distribution rights over DVDs, VODs (video on demand), and CD-ROMs in Korea and overseas; transmission rights; information use rights; rights over secondary property products; performance rights; and music copy rights (see table 1.2). While the areas covered by copyright are diverse and complex, as shown in table 1.2, networks have most of the rights; independent producers only retain the music rights (only in the case of KBS) and 50 percent of the profits generated from exports are redistributed to them but only from Asia and only for three years.13 Some independent producers have been able to exercise full power over the distribution rights to second-round channels and overseas markets, but such cases are very rare and limited to a few major producers who do not need finance from networks (i.e., those who can self-finance by attracting investment from other sources), and in such cases, a broadcasting firm usually offers less than 50 percent of the production cost. In sum, independent drama producers are in a disadvantageous position regarding profit redistribution. The reason independent producers acquiesce in unfair contracts with the broadcasters lies, first, in their urgent need to gain channels, and second, in their dependence on receiving advance payment from a network to start filming. Winning a contract with a broadcasting firm that has channels and funding, however unfair it might be, is a top priority and profit redistribution is something to be dealt with later.

Speculative Nature

The number of independent producers increased explosively within a short period of time due to the fortuitous success of some pioneering dramas in overseas markets. Having grown out of expectation rather than actual market demand, the industrial position of independent producers is again marginal; they have to deal horizontally with enormous competition among themselves and vertically with the monopolistic power of broadcasters. Their proliferation and peripheral industrial position are jointly responsible for their speculative attributes. Drama production is always speculative, but I argue that the Korean drama industry became even more speculative during the 2000s. I focus particularly on the sudden overheating in the industry during the 2000s due to Hallyu, which eventually led to the drastic shifts in production and content. By their “speculative” nature, I mean (1) the ways Korean drama producers had collective expectations about the Korean Wave, which seemed to guarantee the unconditional success of Korean dramas in overseas markets, and (2) a tendency on the part of Korean drama producers to see uncertainty about the popularity of a drama as an opportunity for a big hit from which they would be able achieve greater turnover rates in the short term.

While the emergence of overseas markets drove the sudden mushrooming of independent producers, overseas markets can be accessed almost solely through the domestic airing of programs on terrestrial stations,14 which means that foreign buyers tend to be interested only in those dramas whose success has already been verified in the domestic market. Given that there are only three terrestrial stations, the competition among the more than fifteen hundred producers to gain access to a channel is fierce.15 Excessive competition aggravates the speculative nature of producers’ thinking and actions, because they stake on a few dramas that they barely have the opportunity to produce. Small-sized independent production houses often fail because they do not find an on-air station and, in many cases, because the program on which everything has been staked records poor ratings. A hard-won channel does not necessarily translate into high ratings, and the commercial success of television dramas remains uncertain. Nevertheless, the number of producers has not begun to shrink. Rather, companies try to stay in the business at all costs, hoping to achieve the one hit that will compensate for all their losses. Since nobody knows whether, and to what extent, a drama will strike gold, that very uncertainty drives independent producers toward the fantasy of a jackpot.

Unpredictable nature plays both as risk and opportunity, particularly in the cultural industry. The uncertainty sometimes functions as opportunities for new figures (directors, writers, and actors) to gain fame. Yet what I point out regarding the Korean drama industry is the excessive extent to which drama producers regard uncertainty as the very chance to achieve a hit, much as a gambler views the roll of the dice as a chance to come out ahead. Both investment and speculation assume the risk of loss in return for the uncertain possibility of gain. While investment systemically calculates the potential risks and prepares reasonable measures to deal with them, speculation bets more on the uncertain possibility of gain. Edward Chancellor (1999) discusses speculation by comparing it with gambling: “While a bad investment may be a speculation, a poorly executed speculation is often described as a gamble.… The name given to financial uncertainty is ‘risk.’ Economists differentiate gambling and speculation on the grounds that gambling involves the deliberate creation of new risks for the sake of diversion while speculation involves the assumption of the inevitable risks of the capitalist process” (Chancellor 1999, xi–xii).

Given the then ever-expanding waves of Hallyu, not a few drama producers believed that once they produced a drama, popularity would automatically follow. Considering the extremely slim chance of winning a channel and the equally slim chance of making a hit, the blind expectation of popularity is nothing more than the creation of risks—that is, equivalent to the practice of gambling. Actually, the overall industrial ambiance I sensed in the field is not that different from gambler-like fantasy. One informant put it bluntly: “We only need one big hit that will compensate for past losses and guarantee future profits. The big hit will secure us a channel and casting for a while. If we keep trying, someday that one jackpot is going to come our way.”16 Although this remark is an extreme case of raising the speculative tendency to the level of gambling, it is worth noting some other interview quotes that imply the extent to which speculation dominates the industry: “The industry considers that megahits like Winter Sonata or Jewel in the Palace are not possible any more. But other ways to turn a drama into a business product have been developed and producers’ positions vis-à-vis broadcasters have also strengthened during the 2000s. Two or three solid hits, if not a jackpot hit, will surely bring in enough of a fortune”; “It is not really about the production or ratings. What matters is to get a channel, and that will bring investment and sponsorship. If one is savvy enough, one will make profits even before the production, let along the airing.”17 The last quote suggests that the drama production has become an entirely profit-seeking business as far as speculative producers are concerned, one that is entirely disconnected from its presumed basis in cultural creativity.

The speculative nature can also be found in Korean drama producers’ cultural practices. The film and music industries have developed measures to deal with their products’ unpredictability, strategies such as the use of genres, formulaic plot devices, expensive special effects, and reliance on the star system. They also employ business organizations such as portfolio management, vertical integration, vertical disintegration, and networks of pseudoindependents (Bilton 1999). The Korean drama industry has also used some cultural methods to manage the uncertainty. Yet the solutions are more patchy than systematic: Korean broadcasters and producers tend to follow previously successful models, relying on conventional repertoires and the star system, rather than developing more systematic and creative measures, such as collective writing, investing in fresh themes, and producing more polished and sophisticated plotlines. Because the former hit makers gained success by using, for example, such Cinderella story romance, the industry as a whole tended to be convinced that repeating the same story format, rather than experimenting with new styles, would be safe, or even bring unexpected accomplishment. Although the attempt to structure drama production around similar formulas and brands was successful—at least during the 2000s—these methods now show serious limitations and are facing criticism.

I argue that the perhaps temporary overseas popularity of Korean popular culture has reconfigured the Korean drama industry into a speculative field in which the unpredictable, and thus risky, nature of cultural production is regarded as an opportunity. Unexpected overseas popularity has not only turned the drama industry into an export-oriented field but has also implanted a collective illusion about its export markets, drawing in more gambler-minded players. Its speculative nature has done more than redefine methods of finance and distribution. It has also, and more important, reconstructed production practices, forms of sponsorship, interactions between production and consumption, and storytelling. The next sections will show in more detail how speculativeness has reshaped the essential features of Korean television dramas.

Live Production

The process of “last-minute live filming” (saengbang chawaryeong) is a standard practice in the Korean drama industry.18 Apart from the first few episodes, filming is usually done only a few days in advance of (or on the same day as) the airdate. Script changes are often made last minute, while the final editing of the film is just as rushed, with little time to review the episode before it is released. The closer to the final episode, the more tense the shooting because the demands of production mount. Drawing on the conventional way of referring to last-minute production in the industry, I call these practices as a whole live production. Many hit dramas suffered from lamentably poor endings because of hasty scriptwriting and rushed shooting. For the last episode of Sign (Ssain 2011), shooting was completed only fifty minutes before broadcasting. It is reported that four staff members raced against time to bring the video to the editing room.19 As a result, the protagonist’s voice was lost (due to lack of sound) for twenty minutes during the broadcast. In the middle of episode 19 of The Equator Man (Jeokdoui Namja 2012), the screen suddenly reproduced scenes from the beginning and then went black. Subsequently, a caption was displayed stating that, due to unforeseen circumstances, episode 19 had ended and the final episode would be aired on the next day. News articles revealed that the edited version of film shot on the airdate was not delivered to the network’s master control room in time.20 In Athena: Goddess of War (Atena Jeonjaengui Yeosin 2010) and Painter of the Wind (Baramui Hwawon 2008), injuries to the leading actors led to one episode of each series being canceled. Both incidents were due to the tight shooting schedules.

What and who are driving these “crazy,” but constantly repeated, practices? Three factors are responsible: first, uncertainty about channels; second, the emphasis on raising viewer ratings; and third, attempts to cut production costs.

Independent producers cannot shoot more than two or three episodes before broadcasting without the guarantee of a channel. Yet the more usual practice for independent firms is not to produce any filmed episodes, or even a trailer, before the confirmation of a channel. There are more than fifteen hundred independent production firms in Korea, as has already been mentioned, and only three terrestrial broadcasting stations. The disparity in numbers indicates the fierceness of the competition among producers to win a channel and has led to the establishment of a precontract and postproduction system. Again, as discussed above, independent producers circulate drama proposals (usually consisting of a show synopsis and a script of the first episode) among the three broadcasting stations to win a channel that will broadcast their drama. Only after a channel has been confirmed do their proposals become reality and a substantial production team is established. Broadcasters usually narrow down the possibilities to a short list of two or three dramas before choosing a winner only a few months before the actual airdate. Under these circumstances, the preproduction of a whole drama series is extremely risky. The series Dance in the Sky (Bichunmu) was filmed in its entirety in 2004, but aired only in 2008 on SBS because it took the producer four years to find a distribution channel. The martial arts genre was booming at the time the film was made, but had become passé by the time of airing. Consequently, Dance in the Sky did not go over well with viewers. In fact, the series was ridiculed for its out-of-date computer graphics technology. Its failure educated other producers about the risk of preproduction within the uncertain landscape of the Korean drama industry. Even for risk-taking speculative producers, the risks surrounding the public airwaves pose a more serious problem than popularity in the abstract.

Last-minute filming is a business practice intended to realize high viewer ratings. Broadcasting firms and drama producers share an interest in viewer ratings. Higher ratings not only generate more sales of commercials but also raise their unit price. In addition, ratings are the basis not only for whether a drama will be sold in overseas and additional markets but also for its price in those markets. This critical commercial logic has created a system of what is called jjokdaebon (a slice of script), or “hasty script,” in the Korean drama industry. In this system, extremely short sections of the script arrive on set, barely meeting the live-shoot schedule. Without having the whole plot of an episode or time to study the script, actors shoot the short scene contained in the one-page script. Later, multiple short scenes are patched together during the editing process, leaving questions about the controlling plotline and message. The business rationale for last-minute script writing and revisions is to allow the audience’s voices to be listened to. After airing the first few episodes and observing the viewers’ response, directors and writers collaboratively rework the direction of a drama by changing plotlines, introducing new figures, or adding some provocative scenes. If a particular character attracts the audience’s attention, stories are reconfigured around that character. A drama producer remarked: “Television series have to change in accordance with the audience’s reaction; thus, the script must be carefully polished and a lot of time has to be invested in it. Dramas that are shot in advance cannot gauge the viewers’ reaction, so they are often not accepted by them.”21 Some 100 percent preproduced series did in fact fail to achieve either commercial or critical success. The preproduced series I Love You (Saranghae 2008), Road No. 1 (Rodeu Neombeowon 2010), Tarma, the Island (Tamnaneundoda 2009), and Paradise Ranch (Paradaiseu Mokjang 2011) all received poor ratings and the industry insiders agreed that this was due to inflexibility and an unwillingness to modify story lines. The drama plots are being adjusted all the time, and the translation of scripts into actual film is a last-minute occurrence.

To cut production costs, the filming process is made as short as possible, which also contributes to last-minute shooting. Production costs are two-tiered: costs for creative workers and actual production costs. Above the line, money is invested in star actors, ace writers, and sometimes high-profile directors who are paid on a per-episode basis. Below-the-line expenses, usually less than half the budget, are for supporting and extra cast members, on-the-spot crew members, camera work, sets and special equipment, visual effects, and on-location shooting. Given that crew and supporting actors are paid by the day, the best way to cut the actual production cost is to reduce the number of filming days.22 In On Air (Oneeo 2008), a drama that depicts the situation inside the Korean drama industry, one dialogue between a producer and a staff member at an independent production firm is particularly instructive: “Once the cameras roll, the minimum cost will be no less than $20,000.… So we’ll take a day off.” To produce a drama with minimum cost and maximum efficiency, most episodes need to be shot only a few days before (or on the very day of) the airdate.

The mechanisms used to maintain eleventh-hour production have led to labor exploitation as the intensive workloads necessitated by tight deadlines are shifted onto workers. South Korea has intensive landscapes of drama airing and watching. The fierce commercial competition among broadcasters for advertisement revenues has put an extraordinary emphasis on prime-time television dramas, leading to a “drama war” among the three terrestrial networks. The drama war has been materialized in an increasing broadcasting time. Given that the amount of television commercials cannot exceed 10 percent of the show’s running time, longer running times can sell more commercials. In addition, when its airtime is extended by 10 minutes, a program may attract viewers from other channels who have just finished watching an earlier show. Hence, a longer running time can also raise viewer ratings.23 The three broadcasters gradually increased the prime-time running time from its previous 50 minutes to as much as 80 minutes, before finally agreeing to freeze their dramas’ show time at 70 minutes in 2008. In addition, Korea is unique inasmuch as prime-time dramas air two episodes per week. No commercials interrupt television shows on terrestrial channels in Korea. Weekly filming, consequently, has to fill a total of 140 minutes—more than a feature-length film—which is a challenge, especially in the last-minute production environment.

To meet production requirements, live production entails intensive and often seriously excessive labor, forcing workers into a condition in which they suffer from constant sleep deprivation and alternating periods of waiting on standby and multitasking during the three- to six-month period when a drama is being aired. Excessive working hours in drama production have caused several rounds of controversial debates in the industry. In August 2011, Han Ye-seul, who played the title role in the KBS drama Myung Wol the Spy (Seupai Myeongwol), boycotted further production of the drama by running away to Los Angeles in the middle of shooting and airing, complaining about poor working conditions. But heated criticism from the media and viewers made her return to the set only forty-eight hours after her departure. Although public discourse generated during the earlier stages of the scandal criticized her, saying that a guaranteed $30,000 per episode was sufficient compensation for all the hard work, the event actually shed light on the reality of the working conditions in the drama industry. In response to this event, the Korean Actors Association released a statement saying: “We have to blame the broadcaster and producer for killer filming schedules.… According to Korean labor laws, normal workers are allowed to work only 12 hours overtime per week, in addition to the regular eight-hour working day. Broadcasters, however, never felt guilty even when actors worked 100 hours overtime, reasoning they were not under the legal protection of standard labor law.” In fact, Park Shin-yang, who starred in the hit drama Lovers in Paris (Pariui Yeonin 2004), once said, “The poor working conditions where the cast and production team had to work 42 hours straight need to be improved,” while veteran actor Lee Soon-jae even went as far as to say, “Korean actors currently work in life-or-death situations.”24

Excessive labor is sustained by the workers’ attitude to the public nature of broadcasting. A film crew member remarked: “Not sleeping is required practice in this field. We are so used to it. Nevertheless, drama should be broadcast. It is a promise made to the public.”25 Given this explicit promise to the public, there is an implicit consensus among all participants that broadcasting cancellations should be prevented. Scholarly discussions on labor in the television industry have concerned the affective nature of the work: the pleasures of acclaim, rewards, self-realization, and creativity do matter and become the basis for self-exploitation in creative work (Hardt 1999; Ursell 2000; Hesmondhalgh and Baker 2008; Hesmondhalgh 2011). Affective labor in the Korean drama industry, however, is more associated with the responsibility arising out of the public aspect of television dramas than with the pleasures of creative work (Kim 2008). Actors are not deemed free from a duty to the public. To fulfill her acting responsibilities, Hong Su-hyun, who acted in the drama The Princess’s Man (Gongjuui Namja 2011), returned to the set even after a car accident in which she fractured a rib. These incidents, however, prompt media and public discourse to highlight, and even glorify, the passionate spirit of workers rather than disclose the harsh realities of the industry.

Live production and its associated labor conditions show the speculative nature of the Korean drama industry. Because producers are drawn by expectations of export opportunities without possessing actual financial and production capabilities, the production process itself ends up being last minute and haphazard. For the sake of an immediate turnover, producers show a blind obsession with ratings at the expense of creativity in a drama series. The pursuit of short-term profits turns an already commercial genre, television drama, into a medium of vulgar materialism. To reduce production costs, the cultural production is built on labor exploitation, mirroring the labor-intensive, export-oriented industrialization during the developmental era. Controversies surrounding the exhausting labor conditions are usually dealt with as individual rather than systemic problems.

Live production, however, embodies intriguing twists. The improvised production environment has nurtured an atmosphere in which producers actively listen to the views of the audience and actually accept and apply them in the ongoing production. Benefiting from the practices of live filming, drama producers can immediately reflect audience responses and alter the story lines. Plot change is a direct form of interaction through which audience opinion can be adopted in the drama production. Plot changes mainly fall into two categories. The first kind involves modifying the planned endings of dramas. More than a few dramas have revised their proposed endings as a result of viewers’ requests. The scriptwriters of Love Story in Harvard (Reobeuseutori in Habeodeu 2004) originally intended to include the death of a female protagonist. In response to frantic viewer requests, however, the drama concluded with a happy ending. Audience groups also changed the direction of the drama Wonderful Life (Wondeopul Raipeu 2005), which initially intended to feature the death of a girl, Shin-bi, who failed to get a bone marrow transplant. Meddling viewers reacted to the original story line, saying, “How could the drama be about a ‘wonderful life’ if it ends with the death of Shin-bi?” Writers gave in to viewer demands and, eventually, the conclusion of the drama was converted into a happy ending. Recently, passionate viewers overwhelmed the website of the drama Secret Garden (Ssikeurit Gadeun 2010), calling for a happy ending without anybody dying. Responding to the flood of viewer requests that paralyzed the drama website, a writer working on the drama posted a message on her Twitter account, assuring adoring fans that both couples in the drama would have happy endings.

The second kind of plot change is about adjusting how and how often particular characters appear. Korean television dramas have developed stereotyped character relations in which four main characters (two male and two female) form a love rectangle. The top male and female protagonists make up the lead couple and the other pair acts as the subcouple. But “sometimes totally unexpected character couples emerge into the spotlight. In such cases, we have to modify the love lines.”26 In Giant (Jaieonteu 2010), the Min-woo and Mi-joo couple garnered widespread support from viewers who called for them to make more frequent appearances. Later episodes of the drama How to Meet a Good Neighbor (Wanbyeokhan Iuseul Mannaneun Beop 2007) allowed more appearances of I-man, who originally had a supporting role, because of the character’s popularity. Sometimes groups of fans have heated online discussions about the quantity of screen time their favored actors are allowed. In Dream High (Deurim Hai 2011), fans of Sam-dong and Jin-kuk competitively requested writers to give their stars as high a profile as possible and to allocate more screen time to them. Plot change indicates the flexible, adjustable, and improvised aspects of Korean television dramas, whose writers are always ready to make modifications to cater to sensitive audience groups.

Interactive production27 capitalizes on the nature of the serial, defined by Robert Allen as “a form of narrative organized around institutionally-imposed gaps in the text.… These gaps leave plenty of time for viewers to discuss with each other both the possible meanings of what has happened thus far as well as what might happen next” (Allen 1995, 17). Taking advantage of live filming, the gaps between texts not only allow viewers to reflect on what they have seen and discuss it among themselves but also provide producers with time to listen to viewers and take action. Although John Fiske (1989) claims that meanings and entertainment value derived from consumers’ interventions are not made use of in exchange for material profits, Korean drama producers capitalize on discursive consumption by drawing on audience groups as free labor providing feedback and suggestions. Riding on the practices of last-minute filming and the benefits of social media, the commercial utilization of the audience’s discursive consumption takes place every week, almost in real time. On the other hand, the audience is rewarded by flexible texts that favor them more and serve them better.

The practices of live production have actually facilitated the drama–city and culture–place association. As chapter 2 will discuss in detail, city sponsorship, that is, the practice of municipalities delivering cash grants to productions in exchange for revealing their location in a drama, is sometimes secured even during the middle of airing a drama series. In such cases, the shooting locations should be flexibly shifted to feature the sponsoring cities. A live production system makes such unplanned interventions possible and easier by promptly adjusting story lines and thereby the spatial background of a drama. Such location promotions via television drama are not prearranged; they can be contracted even during the course of airing a series and the target places can be inserted in the drama even when the drama story has already begun to unfold.

Product Placement

The finale for Elegant Revenge is airing tonight, but filming is not finished yet and the scenes in the last ten minutes have to be filmed and edited within less than ten hours. Moreover, a managing director has been trying to insert a ten-second orange juice PPL (product placement) scene (worth roughly $300,000), while the scriptwriter is refusing to change the script; the writer has explained in rather coarse terms to the director that there is no place for orange juice when the main character is supposed to be dying “elegantly” after completing his revenge. The director has therefore moved to plan B and has let an assistant writer edit the script and put the orange juice scene in it, appealing to the assistant writer’s dreams of stardom (i.e., debuting as a main writer). Filming with the revised scripts is done less than an hour before airing time and a motorcycle rider is hired to rush the tape to the broadcasting station that is located more than one hundred miles away from the filming site.

This is a summary of the first episode of The King of Dramas (Deuramaui Jewang 2012), whose director publicly asserted that the series dared to depict the “100% actual” features of the industry.28 The first episode tells how the plots of Korean dramas are modified even at the very last minute to take advantage of product placement.

Product placement entails “incorporating brands in movies in return for money or for some promotional or other consideration” (Gupta and Gould 1997, 37). The Korean drama industry only began to use PPL, even in limited ways, in 2000. The Integrated Broadcasting Act that became effective in 2000 stipulates that “any broadcasting business operator may announce a commercial sponsor, who provides costs, gifts, a location, costumes, vignettes, information, etc.” (emphasis added). The announcement of sponsorship is mostly carried out through textual displays of sponsors’ names at the end of each episode. Although the actual publicity effects of an acknowledgment of corporate names in the titles, displayed for only a few seconds, are in question, independent producers use sponsorship as one of the main channels for funding. Beside the brief textual notification, since direct displays of brand names or corporate logos in the middle of a show were totally prohibited, most dramas tried to suggest the sponsored brand or products through characters mentioning their particular functions through displays of similar logos or of the distinctive interiors of, for example, a coffee franchise. The frequency and level of placements of the sponsored products until this phase, however, remained moderate and did not hamper dramatic storytelling in general.

A sea change came about in January 2010 when the Korea Communications Commission, the nation’s broadcasting regulator, eased regulations concerning product placement in television programs on national networks. Under the new law, all television programs except news, documentaries, and editorial and debate shows are allowed to display brand names and corporate logos. The new regulation has brought about a fundamental transformation in the channels of production funding and, more important, in storytelling in Korean television dramas. The financially unstable independent producers began to use product placement excessively as the main means of covering their production costs. To increase the number of sponsors, and thus the number of PPLs, Korean dramas now insert unnecessary or out-of-context anecdotes and dialogue to display brands and products. This signifies a fundamental change in the commodification of popular culture. By appealing to the tastes of a mass audience, popular cultural products are sold to advertisers (Allen 1985). The conventional method of securing better advertising deals is to present more intriguing and substantial stories to attract more viewers. Product placement, however, turns the story itself into a host of advertising slots. Now Korean television dramas do not really tell a story; instead, they display brands and products. Narrative is a supplementary tool to exhibit the sponsored commodities. Next, I analyze in detail the ways Korean television dramas insert product placement, using the case of Secret Garden (2010) as a classic example of how to attract and insert PPLs.29

Secret Garden features a love story across classes involving Gil Ra-im (played by Ha Ji-won), a poor but proud stuntwoman, and Kim Ju-won (played by Hyun Bin), an arrogant and eccentric CEO who maintains an image of seeming perfection. The apparently conventional Cinderella theme unfolds through several cases of body swapping between the two characters, which enables them to understand one another’s class conditions. Recording up to 35.2 percent of audience share, Secret Garden was a phenomenally successful drama series that went on to be exported to more than thirteen countries. I was doing industrial ethnography as the drama series was about to end. When I interviewed people in the industry, Secret Garden was on everyone’s lips not because of its high ratings and explosive popularity, but because of its savvy integration of product placement into its stories. The production company, Hwa and Dam Pictures, publicly admitted that its story lines had been carefully designed from the synopsis stage to take product placement into account; the firm cooperated with a marketing firm to strategically build characters and set their occupations and residential spaces with reference to the products that were being promoted.30 In addition, one of my interviewees informed me that the writer of the drama maintained a close relationship with the drama production company and was extremely cooperative in including product placements in her scripts; given writers’ customary tendency to avoid advertisements that will hamper the narrative logic of their story, this is an unusual case of a writer sacrificing her creativity to commercial considerations.

Secret Garden made extensive use of product placements intertwined with the storytelling. Even its cases of simple placement31 (which refers to the ways products are either shown in the background or actually used) are well blended with character building. The female protagonist, Ra-im, often wears outdoor gear, in keeping with her occupation as a stuntwoman. Behind this particular piece of character depiction lay the sponsorship of Mont-bell, an outdoor apparel manufacturer, which paid $300,000 to support the drama series, an exceptional amount for a clothing firm. There is one particular scene in which Ra-im’s stunt colleagues go to a Mont-bell store to pick up winter jackets and the store’s logo is prominently displayed right behind the actors. In another scene, Oscar, one of the leading male characters who is depicted as a Hallyu star, holds a meeting with his fans at a Mont-bell store, which enables the brand’s logo and store displays to be directly presented. The sponsoring brand enjoyed huge publicity by being showcased by characters and in backgrounds, selling out of the products that the characters wore.

The series’ protagonist (Ju-won) and his cousin (Oscar) live in a luxurious suburban house whose spaciousness and high ceilings effectively symbolize Ju-won’s claustrophobia and loneliness. Evoking the drama’s title, Secret Garden, the house’s broad and exotic garden with a lake in it features as a critical site in which the two lead characters’ emotional lives are represented through dialogues, flashbacks, and imagined events. The residential space and garden are actually Maiim Vision Village, a human resources training site belonging to the Maiim Corporation (a company that sells cosmetics and health food products). Although not a single Maiim product was placed in the drama series, rendering the corporation’s headquarters publicly recognizable successfully planted Maiim’s brand images in viewers’ minds. When public interest had been aroused in the actual location where filming had taken place, the Maiim Corporation issued a press release introducing Maiim Vision Village.

Yet what Secret Garden truly showcased was its art of integrated placement, that is, the ways product placement became a key feature of the show’s plotline, and thus part of the script (Wenner 2004). A 2009 model BMW Z4, a luxurious sports convertible, appeared throughout the series as the protagonist’s car. The convertible played a critical role in building the character of the protagonist (Ju-won), who drives an open car even in winter because he suffers from claustrophobia. More critically, the drama’s climax highlighted the Z4. When Ra-im is seriously injured in an accident during a stunt and suffers brain death, Ju-won wants to swap bodies with her so that she can continue her life in his body while he takes her place in her brain-dead one. Knowing that their bodies can be switched in the rain, Ju-won takes Ra-im from her hospital bed and drives off in his convertible to await the coming storm. As he sits in the car, he tells her: “I’m going to miss you a lot. I love you”; then he drives the Z4 into the storm. This climactic scene in which the convertible is vital to the plotline produces a far greater effect than conventional advertising, which simply provides consumers with information about the product, because it generates powerful affective values around the BMW. The symbolic process creates more powerful advertising effects, which is why sponsors always prefer integrated placement despite the huge price difference.

The “cappuccino foam kiss” scene is one of the most parodied product placements. In Secret Garden, all the characters are regular patrons of one café: Café Bene. Sponsored by the then newly emerging local coffeehouse chain, the drama series used the café as the venue for the characters’ daily conversations. One day, Ju-won and Ra-im meet at the café and Ra-im drinks a cappuccino. Noticing foam left on her upper lip, Ju-won kisses her to wipe it off. This kiss scene turned out to be sensational and many celebrities parodied the scene by posting photos of themselves with foam on their lips. Photos showing people sitting in a café with a cup of cappuccino also became a phenomenon among bloggers. One blogger wrote: “After watching Secret Garden, I have become a fan of doing sit-ups and drinking cappuccino.… I hope a Prince Charming will approach me and leave a sweet kiss.” Merging product placement into an interesting incident in the drama, the “cappuccino kiss scene” is indicative of a well-designed integrated placement strategy.

After the huge success of Secret Garden in terms of PPLs, there was a fundamental change in the methods of storytelling. Not only did scenes with product placement become a necessity in Korean television series but the invasion of commercial sponsorship narrowed the genre, characters, and story lines of modern dramas down to those that would enable product placements to be easily inserted. Trendy dramas based on the Cinderella theme seem to be the most attractive material for producers, broadcasters, and commercial sponsors, because they are so well suited to a display of lifestyle-oriented consumer goods catering to a young female audience.32 The presence of upper-class characters (known as chaebol in Korean) is required to attract large-scale sponsorship for the display of luxury cars and designer brands, as in Secret Garden. Both producers and broadcasters avoid particular genres such as thrillers, police procedurals, and dramas dealing with serious social issues, because they do not offer enough spaces for the exhibition of commodities targeting viewers’ vanity.33 Thanks to live production, the stories of Korean dramas are extremely flexible, so producers are always able to add scenes with product placement even in the middle of a series. Because late-coming sponsors merely tend to ride on the ongoing popularity of a series, their sponsorship has nothing to do with preplanning characters or plots; producers consequently need to insert awkward offbeat scenes simply to be able to accept the sponsorship. Hence, heightened commercialism not only diminishes the diversity and creativity of the stories in Korean dramas but can also render them a collage of commercial advertisements without a solid narrative.

In response to this heightened commercialism, audience complaints and media criticism have mounted. Blatant product placements have caused some viewers to grumble that this can ruin the experience of watching a show. One viewer complained: “Secret Garden has strong production values with a creative story and mighty performances, but frequent product placements detract from its overall quality.… I’m sick and tired of these advertisements.”34 The drama Style (Seutail 2009) was also criticized for its extensive product placements and suggestive stretches of dialogue that constituted indirect advertisements, leading one viewer to comment, “I feel like I’m watching one long commercial.”35 Given the financial predicament of independent drama producers, however, such criticism has been unable to stop them from relying heavily on product placement as a major funding source. Instead, even historical dramas have recently begun to attract product placement by using the technique of time slip, in which characters travel through different time periods. Due to the restrictions imposed by premodern settings, time-slip historical dramas intersperse some episodes set in the contemporary world, which have scenes featuring product placements. Dr. Jin (Dakteo Jin 2012), Faith (Sinui 2012), and Rooftop Prince (Oktapbang Wangseja 2012) are examples of shows featuring the narrative technique of time slip.

The excessive dependence of Korean prime-time serials on product placement reflects the speculative approach and weak financial conditions of independent drama producers. To put it another way, the speculative nature has redefined the genres, characters, scenes, and narrative methods of K-dramas. The practice of product placement is particularly significant because it defines other forms of sponsorship, and thereby storytelling. In chapter 2, I will discuss how cities are placed in dramas through the practice of city sponsorship. In the same way that drama stories become a patchwork of commercial advertisements regardless of their actual relevance to the plot, urban places and landscapes are simply inserted into the story lines. Product placement was originally aimed at domestic audiences only. With the growing influence of Hallyu and easier travel between Asian countries, the transregional audience has become a target, too. As chapters 2 and 5 will show, drama-inspired transnational tourists now actively consume the food, products, and places that they have seen on the screen.

Catering to the Overseas Markets

Another way in which the industry’s speculative nature determines storytelling in drama is by its catering to potential importers. Just as an expectation of export opportunities triggered the sudden speculative growth in the number of independent producers, the lucrative nature of overseas markets made it imperative for the industry to tailor productions to serve them. Throughout the 2000s up until 2013, Japan was the biggest overseas buyer of Korean television dramas, with its robust markets in broadcasting and secondary products such as DVDs, drama-themed tourism, and celebrity merchandise. More than 60 percent of Korean drama exports went to the Japanese market until 2013 and the unit price of television dramas remains particularly high in Japan (see table 1.1). My informant on the marketing team of a broadcasting station remarked: “Even if you add up all the other Asian markets, profits from exports to them remain far short of the share from Japan. It is the Japanese market that absorbs the oversupply of television drama content in South Korea, instigating the numerous small-sized independent producers to steadily proliferate.”36 This profitable export market acts like a sponsor, leading Korean drama producers to engage in a variety of often desperate tactics to fabricate story lines to serve the audience in Japan.

The most obvious way for Korean drama producers to appeal to Japanese buyers is by exploiting star power, that is, by casting so-called Hallyu stars, actors and actresses who are already popular in Japan. Following the megapopularity of Bae Yong-jun in Winter Sonata, several Korean stars have won celebrity status in Japan: Lee Byung-hun in All In (Orin 2003) and IRIS (Airiseu 2009); Song Seung-heon in Autumn in My Heart (Gaeul Donghwa 2000), Summer Scent (Yeoreum Hyanggi 2003), East of Eden (Edenui Dongjjok 2008), My Princess (Mai Peurinsese 2011), and Dr. Jin; Kwon Sang-woo in Stairway to Heaven (Cheongugui Gyedan 2003), Sad Love Story, Cruel Love (Mosdoen Sarang 2007), Cinderella Man (Sinderella Maen 2009), and Big Thing (Daemul 2010); Jang Keun-suk in Hwang Jin Yi (Hwangjini 2006), You’re Beautiful (Minamisineyo 2008), Marry Me, Mary! (Maerineun Oebakjung 2010), and Love Rain (Sarangbi 2012); Park Yoo-chun from the idol band JYJ in Sungkyunkwan Scandal (Seonggyungwan Seukaendeul 2010), Miss Ripley (Miseu Ripeulli 2011), Rooftop Prince, and I Miss You (Bogosipda 2012); and Lee Min-ho in Boys over Flowers (Kkoccboda Namja 2009), Personal Taste (Gaeinui Chwihyang 2010), City Hunter (Ssiti Heonteo 2011), and Faith. Because the Japanese audience tends to show long-term loyalty to their favorite stars, a critical success factor in exports has been who appears in a drama. This is much more important than what the drama is about. A chief producer at a broadcasting station stated: “In most cases, if not always, the casting of Hallyu stars works, I mean works, in Japan. So when channel lineups are being decided, independent firms who cast a Hallyu star are highly likely to win a channel—mostly regardless of the story synopsis of their proposed drama.”37 The interviewee implies that the lucrative export market virtually determines what kind of stories domestic viewers get to watch. The appearance of particular celebrities trumps ratings in the competition for export contracts to Japan. The drama Marry Me, Mary! was sold on favorable terms to Japan despite its low domestic viewing figures merely because of the exceptional popularity of its leading man, Jang Keun-suk, in Japan. Due to market conditions in which star power controls export potential, Hallyu stars have commanded extraordinary appearance fees during the 2000s, leaving the industry with an even greater financial struggle.

With the rise of K-pop music in Japan, one recent phenomenon has been to cast K-pop idols in Korean dramas. Although the primary channel for K-pop idols to debut is as members of idol bands, idols are an intertextual commodity whose promotion is carried out through the ubiquitous creation and circulation of images via a variety of media (see chapter 3). A synergetic transaction underlies the idols’ appearance in television dramas; idol producers can promote their talents to wider audiences and the drama producers can exploit idols’ popularity. Successful idol acting stars include Park Yoo-chun, previously in TVXQ and now in JYJ, who starred in Sungkyunkwan Scandal, Miss Ripley, Rooftop Prince, and I Miss You; Jung Yong-hwa from CNBLUE, who appeared in You’re Beautiful and Heartstrings (Neon Naege Banhaesseo 2011); Girls’ Generation’s Yoona, who starred in Cinderella Man and Love Rain; Suzy from Miss A, who acted in Big (Bik 2012) and Gu Family Book (Gugaui Seo 2013); and EXO’s D.O., who appeared in It’s Okay, That’s Love (Gwaenchanha Sarangiya 2014). The casting of a K-pop idol as a lead character brings huge publicity not only in Korea but also in various other foreign countries. Once idols mention the drama in which they will be appearing on social networking services (SNS), postings can be circulated everywhere within a very short time thanks to their global fandom. Fan-driven distribution is a bigger deal than media and press attention thanks to its explosive and affective nature: passionate fans volunteer to raise publicity. Besides, the loyalty of passionate fan groups tends to raise viewer ratings as well.

Employing idol singers, however, has raised a number of issues. Celebrity idols are trained as singers and dancers; acting is not their primary area of expertise. The lack of acting ability on the part of some singers diminishes the overall quality of a drama. Not a few veteran actors have raised issues about the singer-actors. For example, an actor who has more than twenty years of experience remarked: “Acting requires emotions. Idols are only technically trained for acting, and even that is totally inadequate due to their crazy schedules (for performing as singers in various venues). Casting an idol is advantageous in terms of attracting investment and product placements. However, their poor acting turns a drama into vulgar commercial content.”38 Viewers also pointed out idols’ lack of acting skills, saying: “I cannot concentrate on the drama because of their awkward acting. Why don’t producers cast new actors who have been properly trained to act?”39 Drama producers’ responses to such comments are usually based on the idea of reducing risk. Producers (if not directors) tend to avoid the risk of employing newcomers who have not had any exposure to the public. One producer commented: “In reality, there are few new actors who are good enough to be cast. Idol singers are at least familiar with the camera. Some new actors even fall far short of being adjusted to appearing on camera.”40 In addition, it is said that idol singers’ appearance fees are quite low relative to their name values. Since paying the top four lead actors comprises more than 60 percent of the total production cost of a television drama, having an actor who is both popular and inexpensive is always preferable for producers.

A more fundamental reason for casting K-pop idols in dramas, despite the pervasive criticism, lies in the fact that idol stars have repaved the way for exports to Japan. Particularly since the K-pop–driven Second Korean Wave, the celebrity qualities of individual idols have developed into something that cannot be neglected even in the drama industry. Given that 30 to 50 percent of profits come from drama copyrights sold in the Japanese market, the casting of idol singers has become standard practice, rather than a one-time publicity event. When a particular drama production company cast a super-idol star who was big in Japan as a leading character, it accepted unfavorable terms from a broadcaster, receiving less than half the normal production costs in the hope of gaining the export rights to sell the show in Japan. This case indicates the significance of casting that targets the Japanese market. In another case, a writer whom I interviewed revealed that when one particular idol singer was cast in a drama, the production company pressed for his appearances in the drama to be expanded, despite his having only a minor supporting role, to facilitate exporting the program to Japan. In any case, acting matters less overseas because most dramas are dubbed into local languages; the mere appearance of K-pop idols and their good looks tend to mean more to foreign viewers. The separation between casting and acting is an indication of how Korean prime-time dramas have tended to “display” people and products more than deliver stories.

Second, Korean television dramas have adjusted their content with a view to lowering transnational barriers to penetrate the Japanese market. In Bread, Love, and Dreams (Jeppangwang Kimtakgu, 2010), as an interview with a staff member at the production firm of the drama revealed: “The name of the title role, Kim Tak-goo, was intentionally created to target export to Japan. Kim Tak-goo (Kimu Tagoo in Japanese) is one of the easiest Korean names for Japanese to identify and pronounce. The pronunciation is also very similar to that of the Japanese superstar, Kimura Takuya. An easy name significantly lowers the cultural barriers in the overseas market.”41 Recently, more and more dramas have also featured incidents that take place in Japan. IRIS, a spy drama involving North and South Korea, includes several episodes set in Japan (sponsored by Akita Prefecture). The Innocent Man (Chakan Namja 2012) shows events happening in Aomori Prefecture in Japan and features the exotic landscapes of the area. In Miss Reply, one of the main male characters grew up in Japan and went to Korea. Since he travels back and forth between Korea and Japan, Japan plays an important role in the story.42 Such an intentionally orchestrated role for Japan in a Korean drama serves to facilitate its appreciation by Japanese audiences.

A third way of catering to the Japanese market is by assimilating Japanese culture. There are an increasing number of cases in which Korean television dramas have adapted Japanese manga, plays, or novels, including Behind the White Tower (Hayan Geotap 2007), Naughty Kiss (Jangnanseureon Kiseu 2010), Royal Family (Royal Paemilli 2011), Dr. Jin, That Winter the Wind Blows (Geu Gyeoul Barami Bunda 2013), The Queen of the Office (Jikjangui Sin 2013), and The Queen’s Classroom (Yeowangui Gyosil 2013). The remaking of Japanese originals boomed because it guaranteed distribution stability both in Korea and Japan. In Korea, of the hundreds of drama proposals they receive in a year, broadcasters tend to favor remade dramas when granting a channel because the public has already proved the quality of originals. Industrial insiders comment: “Remade dramas at least get us our money back. With already proven fresh and solid stories, they always guarantee stable, if not very high, ratings”; “The strong points of Japanese dramas are innovative characters and themes, while most Korean dramas develop stories around class relations and secrets of birth.”43 The potential of Japanese dramas to communicate with Korean audiences also buttresses ratings: “It is hard to guarantee success by remaking U.S., U.K., or Chinese dramas because of the different systems and topics involved. When a solo writer creates a whole drama series, it is impossible to capture the deeper levels of U.S. and U.K. dramas. But Japan is different. Japan and South Korea have similar social issues, such as those concerning irregular workers (addressed in The Queen of the Office; a remake of Haken No Hinkaku, 2007) and education (as in The Queen’s Classroom; a remake of Jyoou no Kyoushitsu, 2005). Shared experiences and sensibilities ease the transnational barrier.”44

From the independent producers’ perspective, a more fundamental reason to favor the remaking of Japanese originals is to get the upper hand in negotiations with broadcasters. Having acquired the rights to the original, independent firms do not need to deliver all the rights in a drama to a broadcaster under contract. Remaking also curtails the fees paid to writers, as adaptations do not require producers to hire a star writer as is the case with an original teleplay. Such economic factors lie behind the boom in Korean adaptations of Japanese originals within the industry.45 What is most notable is that Japanese dramas and films are often remade as Korean television dramas and reexported to Japan. Their acceptance in Japan is facilitated by the Japanese audience’s enhanced familiarity with the material; the adaptation of Japanese serials is a means of overcoming the double barrier between the Korean and Japanese markets.

The appropriation of Japanese styles is not limited to stories. Japanese fashions, music, and food are actively represented in television dramas through scenes and characters. The history of Japanese colonial rule in Korea prevented cultural exchanges between the two countries until 1998, when the then president of South Korea agreed to phase in Japanese cultural products. Despite the official opening up of cultural markets, South Korea continued to be hesitant to accept Japanese cultural content. Whereas Japan is proactive in airing Korean television dramas, Korean terrestrial broadcasting stations do not show the Japanese equivalents.46 Nevertheless, despite South Korean cultural protectionism, Japanese styles are overtly and heavily represented in Korean television dramas as facilitators of exports to the Japanese market. Discussing the global popularity of Japanese pop culture, Koichi Iwabuchi (2002) suggests that “culturally odorless” products in which “a country’s bodily, racial, and ethnic characteristics are erased or softened” have been critical in making inroads into international markets; for example, “the characters of Japanese animation and computer games … do not look ‘Japanese’ ” (Iwabuchi 2002, 28). Cultural odorlessness helps the comfortable acceptance of the content by international consumers. Since the Korean Wave in the early 2000s, the “cultural odor” of Korean dramas has certainly been suppressed. Rather, scenes in Korean serials have been increasingly “Japanized” to tailor them to the Japanese market.

After a decade-long Japanese domination of the export market, however, China is newly emerging as the biggest export destination for Korean dramas (see table 1.1). Local policy and industrial dynamics in China are very dissimilar to those in Japan, causing substantial changes in Korean industrial practices. China has retained a defensive attitude to importing foreign content. Airing overseas films and television dramas cannot exceed 25 percent of daily broadcasting time and is completely prohibited during prime time (19:00–22:00). The Chinese government also bans the import of foreign dramas consisting of more than fifty episodes. Against the background of these strict regulations, one of the popular ways of exporting Korean content has been to sell a format or the originals from which Chinese producers can create a remake version. Temptation of Wife (Anaeui Yuhok 2008) was broadcast on Hunan TV as the Chinese remake drama Hui Jia De You Huo in 2011 and got to number 1 in the national ratings. Zhejiang Satellite TV aired and achieved great success with Fall in Love with Anchor Beauty (Ai Shang Nu Zhu Bo), based on the Korean drama All About Eve (Ibeuui Modeun Geot 2000). Fall in Love (Yī Bùxiǎo Xīn Ài Shàng Nǐ), a Chinese adaptation of the Korean original Autumn in My Heart brought in a huge profit for Hunan Satellite TV in 2010. Two Korean television dramas, I’m Sorry, I Love You (Mianhada Saranghanda 2004) and Secret Garden, were reproduced as films in China, Sorry, I Love You (Wo De Ling Jie Nan You 2014) and The Secret Garden (Mi Mi Hua Yuan 2012). Other successful cases of format export include such entertainment shows as Where Are We Going, Dad? (Appa Eodiga) and I Am a Singer (Naneun Gasuda), both originally produced by MBC. Hunan Satellite TV bought the formats for both and achieved great ratings, producing and airing multiple seasons of the same format.

Nevertheless, the Chinese audience has a much broader experience of Korean dramas via informal routes. Online video sites such Youku, Tudou, and Sohu have functioned as platforms through which Korean television dramas have been widely and freely circulated in ethnic Chinese regions. In the early stages, individual users informally recorded and uploaded K-dramas. Having observed how popular and profitable they are, site operators have recently begun to buy the transmission rights of Korean dramas officially and release the dramas free to consumers, as the sites’ revenues are based on advertising sales. The distribution of Korean dramas via online streaming sites in China has narrowed the time lag between the two countries, enabling almost real-time viewing of episodes in China immediately after their airing in Korea. The accessibility of content via mobile units also enhances online drama watching, since it frees consumers from spatial and temporal constraints. In addition, online platforms operate under relatively relaxed regulations regarding content. These features of the platform and of state policies have found good fits with Korean television dramas, causing more Chinese movie site operators to be interested in importing them. Released on Youku, the biggest online streaming site in China operated by YoukuTudou, The Heirs (Sangsokjadeul 2013) attracted more than one million viewers. The movie streaming site, iQiyi, which is operated by Baidu (the largest Chinese search engine) bought the VOD rights for My Love from the Star (Byeoreseo On Geudae 2013) and distributed it via eight streaming sites including iQiyi, PPTV, LeTV, and Xunrei. Online distribution of the drama recorded more than 3.7 million viewings within a period of just four months, igniting the Second Korean Wave in China.