INTRODUCTION

Most Korean1 television dramas end with a still screen image, designed to act as a cliff-hanger to each episode. The tension is left to linger for a while; then the credits start to run, accompanied by background music against the still screen frame, revealing the names of the drama series sponsors one by one. Since the mid-2000s, the names of Korean municipalities have started appearing in the first few credits, implying that they are the production’s biggest sponsors. My inquiry into cities’ drama sponsorships began with a very brief discovery of one small city’s name in the list of fast-rolling credits of a 2006 megabudget historical drama. Initially, like most other viewers, I did not notice or pay much attention to the credit lists. My accidental recognition that one day, however, caused me to formulate questions about the logistics of these arrangements. Municipalities sponsor drama productions not only to garner public recognition of their areas, but more important, to promote their respective places. In return, Korean television dramas strategically reveal these cities’ landscapes, iconic places, and popular attractions by blending them with stories and characters’ experiences, as well as by including them in the textual notices at the end of each episode. The underlying logic is that the audiences for television dramas represent potential visitors to the sponsoring areas. The rise of K-pop (Korean pop music) since 2011 has offered another medium for Korean municipalities to employ in their place marketing. Korean cities, counties, and districts increasingly try to project K-pop images in their locales by inviting K-pop groups to their local festivals, employing K-pop idols as their public relations ambassadors, or holding K-pop concerts. These strategies intend to deliberately cultivate a K-pop–evoking ambiance in their physical places to help boost the tourism industry. This book explores cases of place promotion as mediated through Korean popular culture since the early 2000s, specifically television dramas and K-pop music. Arrangements for mutual employment between popular culture and cities are now a common phenomenon, one that more than sixty South Korean municipalities have engaged in since the beginning of the new millennium.

The alliance between cultural production and urban policies reveals the untold stories about Hallyu, or the so-called Korean Wave, referring to the overseas popularity of Korean entertainment products, including films, television dramas, pop music (K-pop), and online games. The Korean Wave emerged and swept East Asia beginning in the mid-2000s, and has continued to enjoy international visibility in the United States, Latin America, the Middle East, and parts of Europe. The unexpected and unprecedented international attention given to Korean media has given rise to nationalistic celebrations to mark South Korea’s becoming a culture-exporting country after many years of being a culture importer. Various scholarly works have aimed to understand what aspects of Korean culture appeal to foreign audiences, mainly focusing on content analyses of television dramas, K-pop music (videos), or ethnography-based reception studies.2 The rise of the Korean Wave is undoubtedly an important phenomenon that helps us understand contemporary global Korea; however, I contend that the question should be shifted from “How has Hallyu been possible?” to “How is Hallyu reconfiguring the country?” Since the 2000s, Hallyu has significantly transformed South Korea, so that everybody now seems to be riding the Korean Wave. Korean manufacturers, the beauty, fashion, and tourism industries, culinary services, and even medical services, are trying to use the power of Hallyu to sell their products and services. With the meteoric rise of K-pop in particular, everything seems to be prefixed with a K, a letter that brands made-in-Korea products and culture: for example, K-drama, K-pop, K-food, K-beauty, K-style, and K-culture. What I wish to call attention to in this book is that K-prefixed products and services are not abstract but manifested in and associated with specific places, thus engendering “K-places.” Korean television dramas and pop music not only project an international image of Korean consumer goods and services but brand Korean cities by cultivating and displaying their images and meanings therein. The global spread of Korean entertainment has extended beyond the cultural arena, reconfiguring Korea’s multiple regions and locations as well by attracting its audience as tourists. This book reinterprets the Korean Wave by casting new light on the influence of Korean pop culture not only on commercial and economic life but also on the transformation of cities.

By focusing on the spatial aspects and impacts of Hallyu, this book explores the ways Korean municipalities commodify and sell their urban and rural spaces to potential tourists by being represented in and associated with popular culture. First, I discuss why Korean cities are desperate to promote their specific locations. I focus particularly on the reasons Korean municipalities have needed to use popular culture, rather than other tools, in their place-promotion strategies. Beyond the obvious benefits of circulating Korean entertainment globally, this book discusses the historical, material, and political conditions in Korean cities and their urgent need for the affective and sensational power wielded by popular culture. Second, I examine the nature of popular culture–mediated urban promotion. Urban spaces, as I shall demonstrate, are produced and sold in exactly the same way that television dramas and pop idols are: by promoting spectacular images of them rather than developing their substantial physical and cultural qualities, and by capturing and capitalizing on consumers’ emotional engagement. By revealing how the speculative, image-based, and consumer-harnessing nature of popular culture shapes the commodification of urban space, I argue that pop culture–associated place promotion entails capital’s domination of urban space in more sophisticated and fetishized ways than in the past. In addition to the synergies between abstract popular culture and physical urban spaces, however, this book also delves into the inherent contradictions between them, emphasizing the limits of a form of promotion in which the latter make use of the former.

Why Selling Places?

The concept of “selling places” emerged with the changing conditions of capitalism that occurred during the 1970s, that is, the demise of Fordism and the emergence of flexible accumulation strategies (Harvey 1989b). Since then, many once-thriving Western cities have experienced deindustrialization as increasingly mobile capital movements abandon previous industrial bases in search of new geographies where labor costs less and its organization is weaker. Reacting to the erosion of industrial bases, the practices of urban governance shifted from the provision of public services to those concerned with urban (re)development, what David Harvey (1989a, 4) calls a move from “boosterism” to “entrepreneurialism.” According to Harvey, urban entrepreneurialism is marked by the public sector’s assumption of risk in development projects conducted through public–private partnerships. By attracting private investment, urban governments initiate various development projects, such as creating festival marketplaces, renovated waterfronts, shopping malls, convention centers, sports stadia, aquariums, theme parks, museums, and other cultural places. The construction of spectacular places and the themed built environment is designed to sell the experiences of leisure and entertainment. That is, a strategy to attenuate capital flight and lure residents and tourists entails creating and selling the consumption experiences offered by cities. What should be noticed here is the mutual construction, commodification, and marketing of urban places and the place-based consumption experiences. The postindustrial strategies to revive urban economies involves the making of place as a marketable commodity packaged with goods, services, and experiences that can be consumed in many different ways, signaling a relative transformation of cities from sites of production to sites of consumption. With the changing conditions of capitalism, selling places through the commodification of urban space has emerged and functioned as a new accumulation strategy in cities such as New York, London, Boston, Baltimore, Barcelona, and Glasgow, among many others (Harvey 1990; Paddison 1993; Zukin 1995).

Place selling is not limited to deindustrialized Western cities, however. Aspiring megacities in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East such as Beijing, Shanghai, Dubai, and Brasilia are also active participants in consumption-oriented place promotion and practicing the “art of being global” through the construction of urban spectacles such as iconic landmarks or Olympic stadia (Roy and Ong 2011). For these aspiring cities, deindustrialization is not necessarily a prerequisite for carrying out place selling. In the tough struggles against increasingly fluid capital mobility, the creation and selling of distinctive places is an obligatory survival strategy within contemporary capitalism. Building and selling the spectacular places also works as a political strategy to assert power, boost global recognition, or pacify social discontent (Broudehoux 2007; Shin 2012). The display of urban spectacles can also represent a postcolonial imperative to practice self-determination by combining local heritages and indigenous cultures with cutting-edge forms of architectural innovation (Yeoh 2005).

Rather than deindustrialization or the search for global status, the central driver of widespread place selling in Korea has been the administrative decentralization that has brought drastic changes in urban governance since the mid-1990s. Previously, the country’s military regimes3 governed through a centralized bureaucratic system by which the central government appointed local governors and mayors in a rotational system with four-year terms. During the developmental period from the 1960s to the 1980s, local areas were mere utilizable parts with which the central government orchestrated the nation’s economic development. Due to the centrally appointed local leaders’ compliance with the administrative center’s requests, local interests were muted in favor of the more urgent and bigger task of national development. Since the late 1980s, when the country’s democratization movements burgeoned, Korea has been taking steps to decentralize public administration. In 1988, the Sixth Republic made sweeping revisions to the Local Autonomy Act to revive local control and grassroots democracy, which had been suppressed under the military regimes. In 1991, local elections were carried out to establish local councils, and in 1995 South Koreans had their first experience of electing their own local governors and mayors.4 The newly introduced popular election system has created an environment in which the local state and society envision self-determined futures for their hometowns and energetically design projects for their own interests.

Taking local interests into account is directly connected with accumulating political assets for elected local officials. The elected politicians’ top priority is to be reelected, so they are under pressure to amass a number of visible achievements quickly, that is, within their limited tenure of four years. Elected leaders have two types of local audience that pay attention to their performance: first, local residents within their administrative territories, that is, those who vote them into or out of office; second, residents within the next-level administrative boundaries, that is, in provinces for cities and counties, and in metropolitan cities for districts. From my field research, I observed how elected officials had strong political aspirations not only to be reelected at their present level but also to become leaders of a higher-level administration. Given their determined political ambitions, local politicians need their administrative performances to be highly visible so that the public can easily recognize them. How, then, to impress the local audience with their work? In the field, I asked the same question to all mayors, governors, and civil officials I met: “What is the local government’s priority?” Surprisingly, most of the interviewees gave similar answers: “To develop our areas” (emphasis added). The word develop can be translated into Korean in two ways: baljeon, meaning “bringing advancement,” and gaebal, meaning “improving the economy” or “the built environment,” or both. The conventional understanding of development in the post–Korean War developmentalist period is that gaebal (the urban/industrial infrastructure construction for economic development) brings baljeon (betterment).5 For those local politicians in the decentralized era, however, development means realizing baljeon by increasing publicity. Publicity entails both enhancing the recognition status of municipalities (and thereby that of their leaders) and attracting tourists. There are critical factors that drive elected local leaders to pursue baljeon only by boosting publicity rather than through gaebal, which appears to be more tangible and visible.

Before examining local governments’ recent practices of publicity-oriented place marketing, I would like to briefly overview South Korea’s urbanization process, which mainly focuses on achieving baljeon by carrying out gaebal. The country’s urbanization in the post–Korean War period went hand in hand with its industrialization. The developmental state poured a huge amount of investment into the installation of infrastructure such as expressways, railways, bridges, ports, dams, and industrial parks that became the basis for economic development.6 The construction of large-scale industrial complexes (gongdan) located in the greater Seoul area and across southeastern Korea drove the development of labor-intensive light industries (such as plywood products, shoe manufacturing, textiles, and food processing) in the 1960s and capital-intensive heavy industries (such as steel, petrochemicals, automobiles, machinery, metals, and shipbuilding) in the 1970s. The first industrial complex was built in Ulsan in 1962 and several more appeared in the 1960s and 1970s in places such as Kuro (Seoul), Pohang, Kwangyang, Kumi, Yeochun, and Changwon. To initiate new high-tech industries such as computers, semiconductors, new materials, telecommunications equipment, and biotechnology, the central government continued to develop new industrial sites throughout the 1980s in Suwon, Namdong (in Incheon), Sihwa, and Ansan. The construction of major expressways (Seoul–Busan, Seoul–Incheon, Honam, and Yeongdong) facilitated logistics and transportation between industrial parks and major ports, which contributed to export-oriented industrialization. The state orchestrated the urbanization associated with industrialization through site allocation, land acquisition, and legal regulations in the three rounds of the Comprehensive National Physical Plan (gukto jonghap gyehoek).7

Housing construction is another kind of fixed-asset promotion that was guided by the central government. The “enclosure” process that released rural labor from agriculture through a ruthless cutting of the price of rice caused rural-to-urban migration on a massive scale beginning in the 1960s. The extraordinary concentration of the country’s population in Seoul, in particular, catalyzed sociospatial restructuring of the capital city through multiple rounds of creative destruction in residential areas. To solve the chronic housing shortage, the central government initiated massive residential development through Land Adjustment Development (toji guhoek jeongri) between the 1960s and 1980s.8 Beginning in the 1970s, state policy focused on constructing mass-produced apartment complexes (apateu danji), most of which were developed in Seoul during the 1980s and 1990s, containing more than 310,000 housing units. These large-scale, high-rise standardized apartment complexes signified a growth ideology of massive quantity and high speed on the one hand, and contributed to producing an urban middle class by bringing its members modern living conditions and home ownership on the other (Gelézeau 2007).

State-led, megascale housing construction reached its zenith in the development of five new towns (odae sindosi) between 1989 and 1993. The Five New Towns (FNT) project aimed to build new cities on the outskirts of Seoul as a way of implementing the Roh Tae-woo administration’s (1987–1993) ambitious Two Million Housing Units Construction Plan (jutaek ibaengmanho geonseol gyehoek), according to which the government promised to produce two million housing units within five years. Coming to power within the new democratic presidential election system,9 the Roh Tae-woo administration was required to focus not only on achieving economic growth but also a fairer distribution of that growth. While housing was at the center of distributive politics, property values were skyrocketing in the late-1980s10 and the unfettered rising prices were aggravated by the chronic housing shortage in Seoul. Under the pressure of this political, social, and economic situation, yet wielding the state’s enormous managerial powers, the Roh Tae-woo administration completed the construction of five new towns—Ilsan, Bundang, Pyungchon, Sanbon, and Jungdong—where a grand total of 2,720,000 housing units were established in just five years.11

Even after the demise of the developmental state in the 1990s, state-centered developmentalism did not disappear in Korea. Rather, it was revived in the form of the “neodevelopmentalism” associated with neoliberalism in the wake of the financial crisis of the late 1990s. Myung-rae Cho (2004) conceptualizes “neodevelopmentalism” as the way neoliberalism has caused a new developmental boom, invading everyday spaces and environments. While developmentalism in the 1970s and 1980s placed a heavy emphasis on the economic sector and its requisite spatial interventions, neodevelopmentalism has operated through the commodification of (urban) space. A series of urban development projects since the 1990s—the Five New Towns project; the Cheonggyecheon Restoration; new redevelopment-oriented town projects in Seoul; the Multifunctional Administrative City; Innovation Cities;12 and the Four Rivers Project—indicates how neodevelopmentalism has controlled the spaces of people’s daily lives, extracting the maximum degree of exchange value from urban spaces. In contrast to the developmental state’s proactive role in governing the market, capital now drives neodevelopmentalism. Yet it is still mediated by the state, particularly the central state, in the sense that state urban projects facilitate the movement of capital.

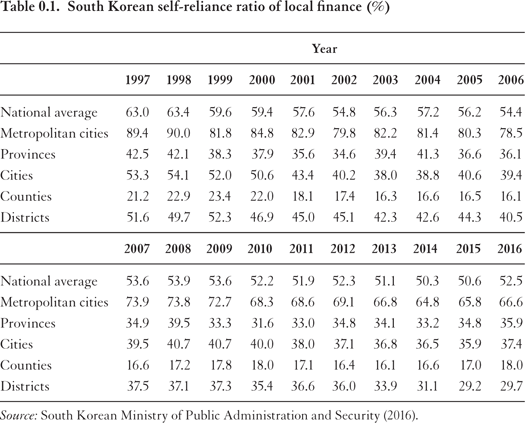

The practices of gaebal, particularly in the developmental era and to some extent in the postdevelopmental period, are concerned with the transformation of the built environment on a massive scale. The primary driver of gaebal is the central state, with its previous authoritarian and still dominant power. Contrary to such central state–dominated, fixed asset–focused forms of developmental urbanization, recent local municipalities’ urban policies mainly focus on culture-mediated place promotion. These new trends, however, do not signal the abandonment of infrastructure-oriented urbanization; on the contrary, major development projects in Korea still mainly embody accumulation through the (re)construction of the built environment. When the primary developer is shifted from the central to local governments, however, the nature of development is inevitably changed because local municipalities lack sufficient material bases and discretional capacities to initiate hardware-driven megadevelopment projects. Despite the political devolution of power, local fiscal autonomy remains extremely weak even after decentralization. As shown in table 0.1, the level of fiscal independence of local states has hovered around 50 percent during the past two decades. What should be carefully scrutinized, however, is the degree of local fiscal independence possessed by small-sized cities, counties, and districts, which is generally less than 40 percent.13 The overall average was boosted due solely to the metropolitan-level municipalities. The figures express local governments’ continuing dependency on the central government, on the one hand, and their weak material foundation for launching development projects, on the other. Attracting industries or launching megaurban projects, therefore, is far beyond local governments’ capabilities. Moreover, due to the chronic regional disparity between the center and periphery caused by uneven development (discussed below), it would hardly be an exaggeration to say that there is no substantial demand for megadevelopment in local areas.

With immense developmental desires yet limited political and financial resources, what can local leaders do to develop their areas, that is, to achieve baljeon in a situation in which they cannot carry out gaebal? Selling place, or place marketing, emerged in this context as a promising strategy to attract tourists as a means of raising publicity and boosting local economies. Compensating for material deficiencies, renewed attention has been given to local cultural assets such as unique artifacts, art forms, histories, traditions, vernacular cuisines, or certain features of the natural environment that aim to act as tourism magnets (Hae 2017).14 Pushing such a culture-oriented paradigm were intellectuals and Western-educated urbanists who planted the notion that place marketing provides locals with the power to foster endogenous development and actualize practices of participatory democracy in the era of local autonomy (Hae 2017). As decentralization itself was promoted by the central state’s policy drive, however, it was the central government that actively sparked the proliferation of place marketing in the form of local cultural festivals (jiyeok chukje) since the mid-1990s. When the tourism15 sector was transferred from the Ministry of Transportation to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in 1995, the central government pushed for the integration of culture and tourism by introducing a system to support promising local cultural festivals. The Ministry of Culture and Tourism, first, selected 8 cultural tourism festivals in 1996 and gradually increased the number to 21 in 1999, 25 in 2000, 30 in 2001, and 29 in 2002 (Korea Culture and Tourism Institute 2006). The selected municipalities receive not only forms of financial aid but also support for publicity directed at both domestic and international audiences. As of 2006, a total of 1,176 local festivals were counted, a number that indicates that central state support has kindled fierce competition among local municipalities. While the central subsidy system contributed to the mushrooming of local festivals, at the same time, it also caused financial and public relations problems among those that did not receive assistance.

To summarize the discussion thus far, the country’s political decentralization and the weak fiscal capabilities of local governments triggered the rise of place selling as a feasible local development strategy. Municipalities at all levels—provinces, cities, counties, and districts—are engaging in place promotion. Thus, the scope of place selling in this book covers both urban and rural places, although I draw on scholarly works on the commodification of urban space. Decentralization prompted strong developmental aspirations in municipalities, but at the same time revealed their lack of the fiscal recourses needed to initiate large-scale infrastructure projects. Given their deficiency of material bases, their methods of pursuing baljeon do not necessarily involve engaging in raw, material competition to attract more capital investment; rather, they undertake tourism-oriented development by promoting distinct local cultural assets. Patrick Mullins (1991, 331) defines “tourism urbanization” as “urbanization based on the sale and consumption of pleasure.” As discussed above, the sale of urban consumption experiences is usually accompanied by the spectacular construction of place. While resource-poor Korean municipalities also resort to tourism urbanization as a development strategy (Hoffman, Fainstein, and Judd 2003), they do not carry out the physical construction of dazzling forms of tourist infrastructure such as upscale consumption places and megaevent venues. Instead, those hidden assets that were once treated as “indigenous,” “primitive,” or even “backward” are reinterpreted as profitable source materials for holding local festivals that primarily target tourists rather than local residents. Without a central subsidy, however, there are financial and publicity problems that arise when presenting local festivals, while the competition among municipalities increases.

Since the mid-2000s, Korean municipalities have attempted to capitalize on the overseas popularity of the Korean entertainment industry. As globally circulating popular culture functions as a window through which audiences come to know Korea,16 specific places within the country have emerged as physical sites through which K-culture experiences can be extended: sites where television shows or films were made; K-pop concert venues; areas where entertainment agencies are aggregated; shops selling celebrity merchandise; and places associated with K-stars’ personal memories. Sites represented in or linked to popular culture have become fantasy places that audience-tourists aspire to visit, and such desires have actually been materialized through a boom in culture-driven tourism.17 Both central and local governments have made various efforts to attract (foreign) tourists by marketing places through their associations with dramas and K-pop. The Korea Tourism Organization, a state corporation supervised by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, has employed top Hallyu stars as advertisement ambassadors since the mid-2000s. Its recent slogan, “Imagine Your Korea,” which has replaced the previous “Dynamic Korea” and “Korea Sparkling,” particularly showcases the country’s cultural appeal to foreigners, portraying Korea as “a trendy and creative tourist destination that leads global pop-culture.”18 What should be noticed here is not merely the deployment of culture to attract overseas tourists. The new motto, “Imagine Your Korea” (emphasis added), highlights the value of personal experiences, motivating individuals to discover the various charms of Korea for themselves. Tourist-centered and experience-focused visits mark a departure from previous guided sightseeing tours to areas noted for their natural or historical value. It is important to recognize that the “must-see” destinations in these guided tours include the tourism complexes developed by the central state, such as Bomun Tourist Complex (gyeongju bomun gwangwang danji) and Jungmun Tourist Complex (jungmun gwangwang danji). When tourists themselves act as agents who design their own travel experiences, their destinations are diversified, leading to the discovery of jibang (regional districts) beyond Seoul and already famous attractions. The transition in the mode of development from infrastructure-driven megaconstruction to small-scale culture-focused place selling has neatly dovetailed with changes in the tourism industry from directed tours of some renowned places to agent- and experience-oriented tours of diverse areas. Korean popular culture publicizes Korea, brings international audiences to the country, and acts as a specific tool through which foreign tourists discover and experience various places in Korea.

The concurrence of the globalization of Korean popular culture, political decentralization, and the boom in transnational tourism created a perfect environment through which pop culture–based place marketing has become one of the most viable methods for enhancing elected local leaders’ visibility. Tourist destinations are not necessarily the sites with preexisting historical, cultural, or natural resources; they can be “created” by giving cities a new image. Television dramas and K-pop music can instantly provide entirely new images to certain places through their stories and characters, regardless of the area’s preexisting identities. Due to the quick and easy creation of pop culture–amalgamated places, municipalities that are poorly endowed with material and cultural resources now have new opportunities to promote tourism. With the rise of new tourism patterns that emphasize individual tourists’ experiences in exploring hidden corners of the country, even previously unmarketable places can be rendered appealing to (foreign) tourists. Yet even traditional tourist destinations such as Jeju and Kyungju are active practitioners of culture-mediated place marketing and tourism promotion because they act as powerful mechanisms to create publicity.

Popular culture possesses some enticing attributes that fiscally weak but entrepreneurial local states cannot resist harnessing. First, popular culture has an affective power that lures audiences. The blooming of emotions in television dramas and idol performances represents an intrinsically different method of attracting tourists than more traditional print media such as brochures. Relying on the affective appeal of pop culture via characters, story lines, idols, and so forth, place promotion strategically targets emotionally susceptible audience groups with the aim of igniting a desire to actually visit the featured sites. Emotionally motivated fan-tourists take the branding of media-associated places one step further by spreading their affective engagement with them among fan communities. Second, popular culture has the power to cause a sensation. As mentioned above, local policies in the era of decentralization are almost entirely designed to showcase the political performance of elected mayors and governors. Urban policies aim to grab the attention of the media and local audiences as much as to actually enhance the living conditions of local communities. Globally rising K-dramas, K-pop, and K-stars are, in that sense, effective channels for advertising local leaders’ urban projects widely and sensationally. Local leaders love to release press reports that put the names of the top stars they are working with on the front page to garner immediate media attention. That is, reports in secondary media additionally publicize any municipalities linked with drama stories and idol imagery. Once municipalities reveal their locales in the cultural content, they do not need to be overly concerned with enhancing publicity; the commercial entertainment yields a multiplied promotion system across diverse media and by the audiences themselves.

In sum, within the context of the globalization of Korean entertainment and the country’s decentralization, Korean municipalities that are developmental and entrepreneurial but financially and politically weak are attempting to render their locales more noticeable and seductive to tourists through popular culture. As Hallyu and Hallyu tourism have become targets of urban development projects, this seemingly cultural phenomenon has manifested itself in the urban environment. As local governments try to revive local areas by attracting foreign tourists by capitalizing on Korean entertainment’s global popularity, their ways of solving local (subnational) problems—such as underdevelopment, poverty, or lack of recognition—are transnational.

How Does Popular Culture Help Sell Places?

I have discussed the recent global hype surrounding Korean entertainment and the political and economic reasons that Korean municipalities have chosen popular culture as a dominant element in their urban policies. In this section, I will provide a detailed discussion of how popular culture facilitates the selling of place. The primary aim of this section is to illustrate the crucial difference between place marketing pursued predominantly through thematic motifs versus via pop culture methods. There is also a perfect match between the selling mechanism of popular culture–featured places and the weak material conditions of Korean municipalities.

In response to cities’ entrepreneurial turn under late capitalism (Hall 1998), urban governments are increasingly compelled to practice the marketing of cities to attract incoming capital investment, boost local economic development, and improve their cities’ images. As the commodification of urban space to attract capital, investment, residents, and tourists has become a critical part of capitalist accumulation, rampant place-making strategies emerge in which distinct images of places are created via the following methods: (1) the transformation of public spaces into privatized consumption areas characterized by a thematic and spectacular built environment; (2) the commodification of local festivals, histories, traditions, and culture in an attempt to attract tourists; (3) the promotion of cultural spaces, cultural institutions, and cultural policies in association with the creative and cultural industries; and (4) the active incorporation of natural elements, landscapes, and eco-designs (Paddison 1993; Zukin 1995; Gottdiener 2001; Harvey 2001a; Hannigan 1998; Gotham 2005; Oh 2014). As Mark Gottdiener (2001) contends, the political economy of place making hinges on endowing a place with symbolic value as a vehicle for profit realization. Thematic designs, eco-concepts, commodified history and traditions, and cultural forms generate additional value—symbolic value—in the built environment by conferring onto it associations with style, quality, or cosmopolitanism that cater to consumers’ desires for status, fashion, sex appeal, or power. In line with Bourdieu’s concept of “symbolic capital,” defined as “the collection of luxury goods attesting to the taste and distinction of the owner,” (1977, 188) symbolic value functions as a means of social distinction that often exceeds and replaces the use-value of a commodity or place. Harvey (2002) explains the creation of collective symbolic capital wherein special marks of distinction attach to some place to help yield monopoly rent. As rent is based on exclusive control over tradable items, some special qualities enable owners to extract rents from those desiring to use them. The creation of symbolic value by accumulating marks of distinction, therefore, facilitates marketing a place, guaranteeing fast and stable rates of return. What becomes critical in place making, therefore, is deciding which themes (distinguishable marks) to employ to produce symbolic value. Over time, more diversified themes have been employed—from nature, culture, history, sports, and heritage, to even traumatic memories of disaster.

The cases in this book focus on the deployment of popular culture in creating unique images of place. At a superficial level, the places’ meanings and values are created by linking them to distinctive themes drawn from television dramas or K-pop music, as in conventional place making. Pop culture–channeled place promotion, however, exercises a very distinct selling mechanism because the urban/rural places are blended with cultural content. It is not the remarkable themes but the places’ affective qualities and consumers’ emotional attachments to them that enhance the value of the places. Operation of the entertainment industry is based on the ability to manipulate affect within the audience. Affect becomes a source of value by bringing emotions into the relationship between cultural products and viewers, thereby transforming commodities into emotionalized communication tools (Lukaćs 2010a). The success of the pop culture industry therefore hinges on the formation of affective relations with consumers. In this book, I argue that pop idols and drama characters are human agents used to build an affective intimacy with audiences. The same principle applies to entertainment-based place marketing. The power of commercial entertainment lies in its ability to turn a physical space into an affective place. The media presentation of stories, characters, dramatic scenes, performances, and idol images reconstructs a televised space not merely as a themed place but as an affective place filled with emotion, imagination, desire, and fantasy.

For many scholars of affect, the difference between affect and emotion is critical (Massumi 2002). Emotions involve specific feelings such as “anger, anxiety, comfort, depression, desire, desperation, envy, exclusion, fear, guilt, happiness, hardship, joy, longing, love, pain, romance, suffering, or worry” (Pile 2010, 6). Affect is a bodily function that arises in a particular context; it is something that is difficult to represent in linguistic terms and lies beyond consciousness. Whereas emotions are cognitive, representable, and personal, affect is precognitive, nonrepresentable, and interpersonal (ibid.). The body matters for both, but in different ways: while the body is a site of feeling and experience for emotion, it is also a device that enables the transpersonal in affect (ibid.). Scholars of affect argue that although experiences and feelings are embedded in social relations, they are ultimately personal and are thus nontransmittable. Affect, on the other hand, is transmittable because it is unformed and unstructured (abstract), which is why it can be such a powerful social force. Due to its capacity to bypass the discussion of intention, meaning, or interpretation, affect is often used in discussions of social, political, and cultural domains (Trigg 2014). The theorization of the difference between emotion and affect is certainly not the focus of this book. Rather, I use emotion and affect as interchangeable terms,19 as they share multiple qualities, drawing on Sara Ahmed’s theorization: “The distinction between affect/emotion can under-describe the work of emotions, which involve forms of intensity, bodily orientation, and direction that are not simply about ‘subjective content’ or qualification of intensity. Emotions are not ‘after-thoughts’ but shape bodies are moved by the worlds they inhabit” (2010, 230–231n1).

Both emotion and affect matter in studying the ways popular culture provides places with emotional qualities and the ways people feel, enact, and extend the cultural experience in a physical place. I call attention to all types of affect/emotions associated with popular culture: the emotions represented in television dramas or K-pop music; the emotions and affect generated in the process of appreciating popular culture; and the affect and emotions developed in audiences as they experience places associated with pop culture. Drama characters and K-pop idols not only exist as images but can affect people through their affective labor, encouraging them to engage in other types of affective labor such as transmitting the appreciation of media content throughout diverse media. Some deeply immersed fans talked about their experience of affect (although they did not use that specific term) by describing the ways “the intense sensation and emotions acted and impinged upon the body” (Choe 2008, 114; Choe 2016) while viewing the television dramas and visiting the drama-filmed sites. The intense bodily emotional sensations that are triggered by both pop culture and pop culture–featured sites, but are not discursively representable, speak to the approaches of “affective geography.” Yet, in both my physical and virtual ethnography of Korean pop culture fans, I was able to recognize such experiences of affect and associated emotions and communicate them through interviewees’ proactive expressions in verbal, bodily, textual, and visual forms. Taking such emotional expressions seriously, this book also follows the perspectives of “emotional geography”20 that investigate the quality/capacity of place to evoke emotions and the bodily experiences of such places.

I argue that popular culture confers affective values on place through its intense displays of emotions such as tension, love, longing, and desire. An affective place is distinct from a merely themed place in the way it attracts visitors. An emotion-laden place draws prospective tourists by stimulating their interest, yearning, and empathy. Because the audience-tourists have already developed a certain level of emotional attachment with dramas or pop idols—albeit to varying degrees among different groups and individuals21—their consumption of a culture-related place transcends mere appreciation of the site and entails developing empathetic bonds with it. Particularly the so-called pop culture–induced pilgrims, who are serious devotees of television series or K-pop idols, do not seek the touristic consumption of place but rather wish to deepen their personal or shared connections with the drama plot, characters, or idols.22 Through the self-motivated tourists’ bodily, haptic, and affective consumption of places associated with dramas and K-pop, they amplify, deepen, and sometimes challenge and negotiate the affective values of places, constructing a new place identity that transcends the reality of the place and culture-depicted images. Such emotional engagement with a place turns visitors into agents of value creation on its behalf—that is, into facilitators of place selling.

In media studies, it is now commonplace to see audiences as active agents, rather than as passive objects trapped in “cultural determinism” (Adorno 1991; Adorno and Horkheimer 2002), in producing their own meanings and pleasure through the consumption of media content (Hall 1980; De Certeau 1984; Fiske 1989; Du Gay 1997). More recent discussions acknowledge the role of the audience as “a collective of active agents whose labor may generate alternative forms of market value” (Jenkins, Ford, and Green 2014, 116). The consumption of media content, unlike other commodities, does not diminish the value of goods. Rather, the collective aggregation of consumption generates greater value, such as when more viewership leads to greater ratings and the selling of more advertisements. Elsewhere, I have explored the ways the collaborative and discursive consumption of Korean television dramas cultivates additional pleasures (beyond the pleasures from the original content) and facilitates interactions between people via social media (Oh 2015). The amplified pleasures in the discursive consumption of popular culture can also be translated into both cultural and material values because the highly engaged audiences pass along the cultural content (both original and secondary fan-made content) across diverse media. Such fan activities help to retain the size of fandom, recruit new members, or further fuel audience fascination. For those reasons, anthropologist Grant McCracken (2005) has proposed shifting the description of people away from “consumers,” as the term locates people at the end of a chain of value creation, to “multipliers” as an alternative that acknowledges the ways audience members generate value through their activities. An audience is not a one-time commodity whose viewership is sold to advertisers but can also be a labor whose engagement and activities can produce renewable values. The media industry has already acknowledged and tapped into passionate fans’ investments in the media content by promoting secondary products such as video on demand, DVDs, electronic rentals, or media merchandise.

Within the disciplines of urban studies and geography, there have been few efforts to identify consumers as value generators. In conventional place making, a commodified urban space decorated with motifs from culture, history, and spectacular events is sold to investors, tourists, and potential residents. Here, the presumed users of the place are seen as passive objects and outsiders to be invited in and encouraged to consume preproduced urban environments such as shopping malls, upscale restaurants, and gated communities. In pop culture–based place making, the audience-tourists are active participants, as well as consumers, in enriching the meanings and values of a place through their development of an affective attachment to it. Visitors to the place broaden, deepen, materialize, and challenge the images and meanings presented in popular culture. Thus, pop culture–mediated place marketing goes through a dual process of value generation. First, the original entertainment content of the kind found in television dramas or popular music imparts affective values to the built environment. Second, visitors’ appreciation of and engagement with the place amplify these affective values, further branding the place. As popular cultural products require a certain level of consumer involvement (e.g., longing, loyalty, and fandom), the commodification of urban space via popular culture similarly harnesses audience groups’ (particularly fans’) emotional investments as free but dedicated labor to facilitate its selling. The “affective economics” (Jenkins 2006, 61) can be extended into the selling of place by commodifying passionate fans’ desires, commitment, and their social power. Exploitation, however, might not be an adequate descriptor of this mechanism because audience members themselves benefit from their willing participation in such arrangements. Fans’ “labor of love” (Galbraith 2016, 234) can be rewarded by increased enjoyment and deepened emotional fulfillment. The affective economy both commercializes and satisfies fans, but “in asymmetrical ways” (Takeyama 2010, 238) between place marketers and consumers.

The utilization of users’ emotional engagement in selling places speaks to the severe disinvestment by both public and private marketers of place. Because dramatizing the urban environment relies on images from television dramas or of K-pop idols, place-based extravaganzas do very little to improve cities’ actual physical qualities or to resolve community issues. Harvey (1989a) points out that entrepreneurialism focuses much more closely on the political economy of place than on territory. In other words, the construction of places such as new civic centers, privatized public spaces, or dazzling new entertainment complexes has a limited spatial impact and concerns only the actual place itself, whereas welfare projects such as housing, education, and health care work to improve living or working conditions within a particular jurisdiction. The construction of place embodies elitism in action; it has a much smaller impact on a territory as a whole, and thus raises issues of spatial injustice (MacLeod 2002). What I wish to point out is the further narrowing of the public’s role in image-dominated and user-harnessed place construction through popular culture, although the public sector (i.e., local government) hypes place promotion at the policy and publicity level. As entertainment-oriented place marketing taps into consumers’ emotional resources and engagement in enriching the values of places and advertising them, the place marketers’ investment is even further diminished. The spectacular cultural images projected onto the urban landscape obfuscate this continuing disinvestment. The process is a sophisticated mechanism in the commodification of urban space: pop culture fetishes confer dramatized images on urban space and lure affective consumers to engage with and further advertise the place in question. By drawing on consumer agency to both consume and sell place, place marketers can reap returns without significant investments. Korean place marketers’ utilization of fan-tourists’ emotional investment to rebrand and promote places reveals their resource-strained condition, which, ironically, leads them to rely more on consumer engagement.

Such a refined and instant commodification process creates tensions for local residents, who are almost invisible in the urban image construction process. Popular culture and media create pseudo local histories that do not engage with the community, but simply elicit audience affection that will smooth the marketing and selling of places. Flamboyant urban spectacles mediated through commercial entertainment have nothing to do with the lived experiences of local residents; instead they conceal and distort the existing local reality, local demands, and local politics. Although newly generated meanings are not necessarily related to preexisting local history, municipalities remain eager to utilize the instant, pseudohistory created by popular culture to boost their recognition and entice tourists. Scholars point out the dual effects of urban spectacles in relation to the state: image construction serves political ends as an instrument of state legitimation and as a means of popular pacification, on the one hand, and urban beautification also has a depoliticizing effect by distracting society’s attention from social and economic inequities and reducing a city to a transparent and unproblematic surface, on the other (see, e.g., Debord 1994; Broudehoux 2004; Shin 2012). Nevertheless, another critical function of spectacles is to render such discrepancies and tensions even more visible (Gotham 2005; Broudehoux 2007). The exaggerated representation of a place can cause local residents to recognize how they have been detached from the process and thereby spark their political will to combat the conflicts and struggles that arise when converting cities into tourist spectacles. Place marketers, who are mostly local leaders and civil officials, face a contradictory situation in which the accumulation of political capital through the sort of instant publicity that popular culture can furnish clashes with their imperative of maintaining legitimacy to enable them to manage the local community.

Speculative Venture

Harvey (1989a) argues that the place marketing practices of urban entrepreneurialism are speculative because they involve risk-bearing scenarios for the deployment of local fiscal resources, as opposed to rationally planned and coordinated forms of development. Interpreting entrepreneurialism as a type of innovation in which urban entrepreneurs devise new ways of doing urban governance to be as competitive as possible, Jessop agrees that an entrepreneurial function involves uncertainty “since innovation means venturing into the unknown” (1998, 82).23 Cities cannot predict whether their investments in property-oriented development will be successful. Moreover, only a few cities can enjoy competitive advantages within the ever-intensifying interurban competition, because holding iconic events (such as the Olympic Games and world fair) as a place promoter, for example, is a rare and fleeting opportunity. The recent pop culture–featured place marketing practices in Korea—the central focus of this book—are extremely speculative not only because the public sector (i.e., local governments) assumes the risks involved in the place projects, but more important, because the practices are associated with popular culture. I will outline the ways both the Korean pop culture industry and Korean local municipalities are venturing into speculative business. Their speculative character has been intensified due to the mutual reliance between the two speculative players: the entertainment industry and local municipalities.

I would like to first examine the speculative features of the culture industry by outlining the industrial changes that have occurred since the beginning of the Korean Wave. All business is risky, but the culture industry is particularly risky because it is centered on the production and selling of texts and symbolic goods that depend on subjective judgment at the point of consumption (Bilton 1999). The accidental and unexpected formation of the Korean Wave, I argue, has aggravated speculation in the Korean pop culture industry to the point that it has spiraled out of control. The reason for this lies in the characteristics of cultural products. According to Nicholas Garnham (1990), cultural commodities have special features,24 one of which is their relatively low reproduction cost.

Because one of the use-values of culture is novelty or difference, there is a constant need to create new products which are all in a sense prototypes. This drive for novelty within cultural production means that in general the costs of reproduction are marginal in relation to the cost of production. Thus the marginal returns from each extra sale tend to grow, leading in turn to a powerful thrust towards audience maximization as the preferred profit maximization strategy. (160)

Therefore, once a television drama has been filmed and edited, and an accompanying music album has been recorded, the production of an additional physical copy costs relatively little. In the current era of digitization, which Bolin describes as “the process whereby media texts are broken down into digits, and are hence reproducible without a loss of quality” (2009, 347), the marginal returns from each extra sale are relatively high because the reproduction costs are negligible.25 The high ratio of fixed to variable costs means that big hits are extremely profitable because the surplus rises without any increase in the production cost. This point has been critical to the Korean culture industry since Hallyu began because the unexpected overseas popularity of Korean pop culture has led to the acquisition of additional markets, meaning pure profits without extra production costs.26 In contrast to the finite domestic market, the number of overseas markets is vast. For example, Jewel in the Palace (2003), one of the drama series that drove the formation of the Korean Series, has been exported to more than sixty countries. The focus therefore becomes the search for export markets that might yield profit jackpots.

The sudden and accidental formation of the Korean Wave sparked expectations about overseas markets among previously domestic-focused cultural producers. Anticipation caused a sudden increase in the number of industry players—drama producers, entertainment management agencies, record labels, and idol wannabes—who hoped to take advantage of potentially lucrative export opportunities. Yet the Korean Wave does not necessarily indicate a rise in actual overseas demand for Korean entertainment. Rather, there has been an increase in potential demand initiated by the success of some pioneering shows, and the industry has advanced only far enough to see the latent opportunities. The proliferation of industrial players driven more by expectations than by actual demand has rendered the industry highly speculative, because competition is heightened among nascent players whose capabilities have not yet been verified. Moreover, most anticipation-driven industrial newcomers lack financial power, driving them to search for funding sources. While financial struggles drive industrial players to be even more speculative, as chapter 1 and 3 will elaborate, Korean cities (and, to some extent, other East Asian cities) emerge as one of the sources of funding, opening up a marriage between the culture industry and cities, and thus between culture and place.

The global popularity of Korean entertainment has generated a great sense of anticipation among place marketers, in particular because overseas audiences are seen as potential tourists. Attracting foreign tourists certainly boosts local economies due to the high number of visitors and their strong purchasing power. Yet a more critical role of overseas tourists is to create sensations. The gaze of foreigners has been a persistent theme in South Korean development. In pursuing export-oriented economic development, the developmental state cultivated a mentality of consciousness of the foreign gaze: an outlook that emphasizes the extent to which the international community is paying attention to the performance of South Korea, a postcolonial latecomer on the world stage. To verify the extent of this gaze, domestic media have competed with one another to deliver overseas responses to major sporting events such as the Seoul Olympic Games in 1988 and the Korea–Japan World Cup in 2002. The developmental state harnessed the imaginary but powerful idea of overseas attention paid to Korea to mobilize the population, increasing the amount of both exports and labor, and forcing individuals to make sacrifices for the greater cause of national development. The foreign gaze stimulated the country to speed up development and hasten modernization, implanting the normative notion of national progress. Now, in an effort to transform urban space from a production to a consumption space, the presence of foreign bodies is celebrated to make these cities appear global, truly attractive, and worthy to visit. As the presence of foreign tourists has become the central promotional asset, chapter 2, 4, and 5 will recount the ways municipalities pay attention to the number of foreign tourists that visit their areas and capitalize on these numbers in their second-round advertisements. But how are foreign tourists allured to every corner of Korea? The instant popularity of entertainment content does not lead to constant inflows of tourists; consequently, intermunicipal rivalry for attracting foreign tourists is intense. Moreover, other political and diplomatic matters significantly affect the number of tourists. For example, when the sinking of the ROKS (Republic of Korea Ship) Cheonan occurred in 2010, the number of inbound Japanese tourists dropped significantly for a while, and the deployment of the antimissile Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) in 2016 virtually stopped the previously high influx of Chinese tourists.27 Drawing overseas travelers to local places is therefore also speculative because there is never any guarantee of steady streams of tourists.

Both the Korean pop culture industry and Korean municipalities are engaging in speculative ventures to penetrate overseas markets and draw overseas tourists. Both groups may be well aware that the Hallyu-driven hype is more or less supply-driven rather than demand-driven. Despite the risks involved in the oversupplied race, both the cultural producers and place marketers appear confident because of the sheer amount of uncertainty involved. That is, nobody knows whether a play, show, song, and so forth, will be a hit or not; therefore, it is never clear whether the place selling packaged within particular entertainment content will be successful or not. Due to the Korean Wave, or more precisely due to the megasuccess of some pioneering shows such as Winter Sonata and places like Chuncheon (the spatial setting of the drama series), Korean cultural producers and local governments consider such unpredictability to be an opportunity. Because some former successful cases enjoyed huge fortunes through just one megahit, small independent producers, minor music labels, and poor local municipalities keep engaging in the venture despite several failures they have experienced. Due to this uncertainty, they believe one big hit will come and compensate for the past losses. The practices of gambling on unpredictability aggravate their speculative tendencies.

Another factor contributing to the speculative character of the Korean culture industry and urban governance is their increasing financialization. The critical problem of contemporary financialized capitalism (or rentier capitalism) is that it seeks capital gains without producing any tangible benefits to society. In industrial capitalism, the surplus value that is created is reinvested to expand markets, invest in new production techniques, or produce future manufacturing bases. Financialized capitalism, by contrast, seeks profits through rents accrued by monopolizing access to physical, financial, cultural, or intellectual properties (Hudson 1998). Place marketers’ search for short-term profits by generating buzz via popular culture without tangible long-term investment resembles the practices of financialized capitalism. The mechanism of culture-mediated place marketing that costs relatively little and extracts surplus value through the audience’s emotional dedication mirrors rentier capitalism’s speculative proclivities—that is, aiming for instant returns without solid resources.

Intriguingly enough, the highly speculative nature of Korean cultural industries and cities has spawned culture–place associations based on the groups’ mutual needs. The cultural producers in search of funds have found Korean cities to be both financial and spatial sponsors that are willing to both cover the production costs and provide the filming sites. The buzz-seeking municipalities reap multiple advantages from their employment of popular culture, that is, spontaneous publicity, relative inexpensiveness, and the ability to inspire users’ loyalty. The linkage between cities and pop culture, however, does not always produce synergies. In fact, the dynamics between the two are quite complicated. Television dramas and music, as abstract media, are different from physical urban spaces in the ways they operate through time: the instant nature of commercial entertainment quickly generates dramatic promotional results for cities, but its unpredictability and subordination to current fashions render the benefits unstable and volatile. While popular cultural industries simply leave particular urban places after receiving sponsorship from them, local authorities are forced to deal with any material and physical problems that they leave behind. Although municipalities are already familiar with such instability after witnessing many failure cases, many of them still venture into projects nonetheless in the hope of being part of a megahit. Two critical questions arise. First, could the mobilization of local finance and resources for such speculative projects be justified? By channeling public resources into the image-making project, local governments often forgo other opportunities concerning welfare and social well-being in general. Although place selling is, of course, place-specific—that is, the creation of superficial seductive images only focuses on limited places—its impacts exceed the place boundary and affect local communities at large. Thus, a second question emerges regarding who is responsible for the lingering challenges that the pursuit of a faster return imposes on urban communities and how to deal with them.

Unevenness

Unevenness is a key critical concept discussed throughout this book. While virtually all municipalities at every level display a similar desire to promote their areas, there are stark contrasts between players in Seoul and those in other parts of the country in the strategies and channels they choose, and in the outcomes of their place-promotion efforts. Unevenness operates in multiple realms and at multiple levels in spatial, cultural, and socioeconomic processes. First, I tackle the spatial disparities created by the country’s unbalanced development (bulgyunhyeong baljeon) among regional cities and districts in Seoul in terms of their development, power, and wealth. Second, I underscore the fact that this very spatial unevenness makes it inevitable that regional cities and Seoul’s districts will choose different promotional media: television dramas for regional cities and K-pop idols for Gangnam and Myeong-dong, two affluent central districts in Seoul. Third, this book shows how the different promotional media have brought about different outcomes and challenges to the two groups of actors.

The multilevel asymmetries referred to above originate from the country’s uneven development. Scholars argue that the concept of uneven development provides a sound basis for understanding the shifting geographies of capital accumulation and social inequality (see, e.g., Smith 1994; Harvey 1978, 1996, 2001a). Capitalism requires continual growth and is subject to periodic crises of overaccumulation in such forms as idle productive capacity or augmented labor power. One solution to both problems is geographical relocation, what David Harvey labels a “spatial fix.” Excess capital may find alternative places for production, property development, or other speculative investment (Harvey 2001b). The incorporation of East Asia into the world industrial production system—as a site to absorb surplus capital in the form of foreign aid, as a new export market, and as a provider of inexpensive manufactured goods—can be understood as a spatial fix for the potential crises in the West in the 1950s and 1960s. When the country was about to initiate industrialization after the Korean War, the Korean state was forced to start from scratch on war-torn land. The Korean developmental state adopted strategies to mobilize national resources and people, then concentrate them in a few selected sectors or areas as an effective means of initiating development. In other words, South Korea’s international competitiveness was created and maintained through uneven development at the national level.

The state’s so-called picking winners policy favored capital, men, and the greater Seoul area over labor, women, and local regions in the name of expediting economic development. For example, the developmental state preferred export-targeted industries and, therefore, actively promoted labor-intensive light industries such as textiles, shoes, and wigs in the 1960s and heavy and chemical industries in the 1970s. In light of the country’s resource constraints, spatial selectivity and concentration were also evident in the channeling of investments for infrastructure into a few designated areas to maximize efficiency. Strategic spatial selection favored the Seoul Metropolitan Area (SMA; sudogwon) and the southeast coast, which turned into major industrial sites as a result of the state’s investment (Park 2008). While Marxist geographers discuss uneven development as characteristic of and functional to capitalism by bringing wealth to the center and exploiting the peripheries,28 uneven development in South Korea was brought about by state policies that controlled the operation of capital. But planned concentration likewise created center–periphery unevenness.

Within such a context, the SMA was a primary destination for resource distribution, capital investment, and population movement. The outcome of such spatial selectivity has been an extraordinary degree of concentration of capital, people, and power in the greater Seoul area, which can be expressed in multiple numerical indicators. For instance, more than half of the Korean population lives in the Seoul metropolitan region, despite the fact that the area comprises a mere 11.8 percent of South Korea’s territory. As of 2010, the greater Seoul area was home to approximately 55 percent of the country’s manufacturing firms, 66 percent of universities offering regular four-year degrees, 73 percent of the research and development institutions, and 77 percent of Korean venture businesses. As of 2000, the SMA was said to have 46.5 percent of the working population and to be responsible for 48 percent of the total gross domestic product. Not surprisingly, the headquarters of 95 of the 100 largest enterprises, all 27 central ministries, and 87.6 percent of their affiliated organizations are also located in the SMA.29 As a result, the SMA has commanded hegemony in all aspects, while the rest of the country has held merely a peripheral status.30 The trend implies that the benefits gained from already established agglomeration economies and relatively abundant employment opportunities outweigh the negative congestion that accompanies extreme concentration.

Many regional cities located outside of the greater Seoul area, and even some cities and counties within the SMA, mostly those designated as greenbelt or nature preservation areas, have been neglected by national development and have suffered from economic stagnation, poverty, and underdevelopment. “Regional city” is an English translation of the Korean word jibang dosi, used as an opposite concept to sudogwon, meaning the Capital Region, the greater Seoul area, or the SMA. In this book, “regional city” refers to a small, local, peripheral, and marginalized city, county, or district, shaped by South Korea’s uneven development trajectories of the post–Korean War era. I argue that the legacy of uneven development relegated Korean regional cities to marginal status, thereby creating within them strong aspirations toward betterment. In the decentralized era, regional cities have tried to transcend their marginal position by boosting self-motivated development.

Intriguingly, however, the underdeveloped conditions of regional cities can be capitalized on by portraying them as exotic, lyrical, and imaginary elements in popular culture. For television drama producers who require spacious nonurban land to build drama sets or provide exotic visual elements to be integrated into drama stories, regional cities emerge as the perfect spatial backgrounds for television dramas and also attract eager financial sponsors. Thus, during the First Korean Wave (2003–2011), which was driven by dramas, mutual needs and synergies were formed between regional cities and drama producers. By dramatically displaying places in regional cities, television programs, on the one hand, conferred new meanings and identities on them and, on the other, allowed audience members (who were potential tourists) to get to know the jibang. The 2000s witnessed the formation of critical interconnections between the transnational buzz of Korean television dramas and the political decentralization of Korea itself. Thus, television dramas have been used in regional cities’ recent efforts to turn the trajectories of uneven development around by actively promoting their areas.

The Second Korean Wave (since 2011) led by K-pop music has engaged in a very different kind of spatial development. While the global K-pop boom has also drawn on international fans’ interest in K-pop–associated places, their destinations are not nationwide but are concentrated only in the Seoul districts where entertainment agencies and music labels are clustered. Thanks again to the country’s uneven course of development, Seoul, particularly the Gangnam area, boasts rich cultural resources, including in particular companies that produce dramas, films, music, animation, and commercials. For those ardent fans who wish to meet their favorite K-pop idols in person, Seoul is the place where they can extend their experience of K-pop from the visual and virtual, via online music videos, to the corporeal and physical. Under the local election system, some ambitious district governors in Seoul began tapping into the already established cultural infrastructure to promote their areas. Without any tangible investments, Seoul districts have fortunately “found” and utilized historically formed popular culture resources in their areas. Two representative districts are discussed in this book: Gangnam and Myeong-dong, whose meanings, landscapes, and identities have shifted in recent years because of K-pop images.

Many cities, counties, and districts are vigorously promoting their areas using K-dramas and K-pop. Local states cannot ignore the sensational publicity effects that popular culture can bring. Yet the different forms of media—television dramas and K-pop music—that the center and margins are able to utilize in their place marketing reveal the continuing legacy of uneven development. Regional cities with limited material and cultural assets are associated with television dramas that target their less urban landscapes. Yet one-off sponsorships of a drama production without providing a stable cultural infrastructure to support it have their limits in terms of stability and sustainability, leaving regional cities with long-term revitalization problems. Affluent districts in Seoul, the fortunate beneficiaries of unbalanced development, on the contrary, can easily take advantage of the cultural infrastructure they already possess. Although both players engage in short-term, publicity-seeking speculative investment, thanks to their concentration of resources, districts in Seoul are able to devise more renewable and diversified cultural strategies through the cooperation of entertainment firms. Unevenness, therefore, still permeates the country, as shown by the different media and outcomes of pop culture–mediated place promotions in different areas.

The discussion of unevenness reveals the spatial aspects of Hallyu by identifying how the cultural phenomenon constructs and is constructed by the urban changes in Korea. The spatial impacts of the Korean Wave that alter local places complicate the conventional understanding of Hallyu as a vehicle for outward expansion in tune with Korea’s global aspirations. The outward circulation of Korean entertainment has spawned inbound global flows by drawing in its audience as tourists and shoppers. Specific places in South Korea, particularly those in local areas that have been historically overshadowed by the hegemonic power of Seoul, have recently emerged as sites of consumption for both domestic and foreign tourists. The actual influx of visitors has caused “friction” (Tsing 2005) in specific localities, transforming their economies, landscapes, and politics. The preexisting uneven historical, political, and economic geographies turn such frictions into uneven flows. Hallyu is not just a cultural phenomenon but an amalgam of multiple domains, including popular imaginaries, cultural desires, consumer markets, tourism, and local development. The changes in cultural production and consumption, tourism, and urban places that has been driven by the Korean Wave show how global, national, and subnational flows are intertwined. This book identifies the correlation between culture and space by clarifying the Korean Wave as a multisphere, multiscalar, and multidirectional phenomenon.

Organization of the Book

Pop City is organized around the two different waves of Korean media entertainment that have engendered distinct types of place marketing: the drama-driven First Korean Wave from 2003 until 2011, and the pop music–led Second Korean Wave since 2011. The year 2011 was the turning point when the Korean media started to circulate the term shinhallyu, meaning New Korean Wave. The third generation of K-pop idols, including Girls’ Generation and KARA, made successful inroads into Japan in 2011. SM entertainment held the SM TOWN Concert in Paris that year, signifying the true globalization of K-pop beyond Asia. Since 2011, Korean popular music and pop idols have emerged as front-runners in attracting international audiences to consume South Korean culture. The periodization does not necessarily signal a downturn in Korean dramas’ performance overseas. China has replaced Japan as the main importer of television dramas since 2013, so the export markets for Korean dramas have broadened recently, driving production to even higher levels. Nevertheless, the preferred medium for municipalities’ place promotion has certainly transitioned from television dramas to K-pop music, particularly in areas associated with K-pop idols.

Moreover, the two different waves are associated with two distinct geographies: the First Korean Wave is tied with regional cities (part 1) and the Second Korean Wave, with districts in Seoul (part 2). The two parts of the book have a parallel structure. Each pairs an analysis of a Korean pop culture industry with an examination of place-promotion cases featuring that culture and demonstrates how the profit-seeking practices of the culture industry have neatly dovetailed with Korean cities’ branding schemes. Part 1 examines how the speculative nature of Korean drama production has been projected onto drama-themed place marketing practices that are short term and high risk. Part 2 shows how place marketing cases using K-pop reflect the visually oriented and affective qualities of K-pop production and consumption. In sum, I examine how place-promotion strategies mirror precisely the speculative, image-dominated, and consumer-exploitative popular cultural industry, on the one hand, and how the ways their cooperation with the cultural industry31 bring both short-term opportunities and long-term managerial challenges to cities, on the other.