“Why, that he is no other than Lord Ruthven himself in a living form.”

This fresh allusion to Byron5 drew a smile to Franz’s countenance; although he could but allow that if anything was likely to induce belief in the existence of vampires, it would be the presence of such a man as the mysterious personage before him.

“I must positively find out who and what he is,” said Franz, rising from his seat.

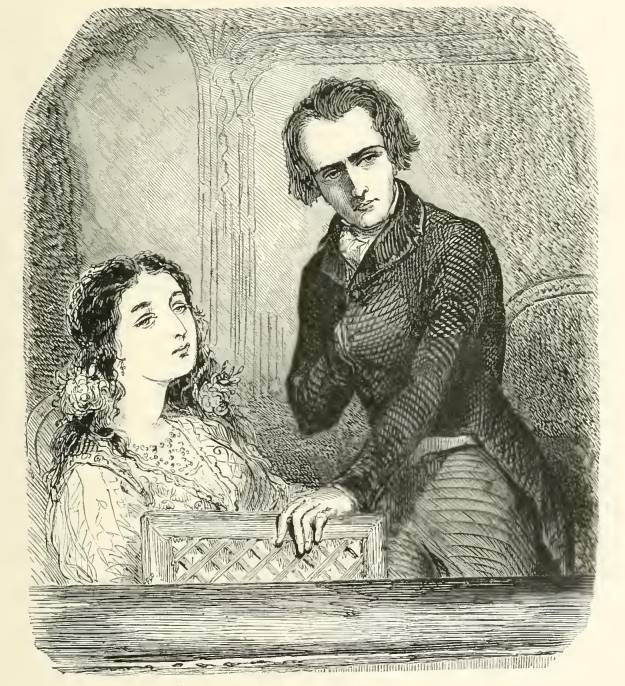

“No, no,” cried the countess; “you must not leave me. I depend upon you to escort me home. Oh, indeed, I cannot permit you to go.”

“Is it possible,” whispered Franz, “that you entertain any fear?”

“I’ll tell you,” answered the countess. “Byron had the most perfect belief in the existence of vampires, and even assured me that he had seen them. The description he gave me perfectly corresponds with the features and character of the man before us. Oh, he is the exact personification of what I have been led to expect! The coal-black hair, large bright, glittering eyes, in which a wild, unearthly fire seems burning,—the same ghastly paleness. Then observe, too, that the woman with him is altogether unlike all others of her sex. She is a foreigner—a stranger. Nobody knows who she is, or where she comes from. No doubt she belongs to the same horrible race he does, and is, like himself, a dealer in magical arts. I entreat of you not to go near him—at least tonight; and if tomorrow your curiosity still continues as great, pursue your researches if you will; but tonight you neither can nor shall. For that purpose I mean to keep you all to myself.”

Franz protested he could not defer his pursuit till the following day, for many reasons.

“Listen to me,” said the countess, “and do not be so very headstrong. I am going home. I have a party at my house tonight, and therefore cannot possibly remain till the end of the opera. Now, I cannot for one instant believe you so devoid of gallantry as to refuse a lady your escort when she even condescends to ask you for it.”

There was nothing else left for Franz to do but to take up his hat, open the door of the box, and offer the countess his arm. It was quite evident, by her manner, that her uneasiness was not feigned; and Franz himself could not resist a feeling of superstitious dread—so much the stronger in him, as it arose from a variety of corroborative recollections, while the terror of the countess sprang from an instinctive belief, originally created in her mind by the wild tales she had listened to till she believed them truths. Franz could even feel her arm tremble as he assisted her into the carriage. Upon arriving at her hotel, Franz perceived that she had deceived him when she spoke of expecting company; on the contrary, her own return before the appointed hour seemed greatly to astonish the servants.

“Excuse my little subterfuge,” said the countess, in reply to her companion’s half-reproachful observation on the subject; “but that horrid man had made me feel quite uncomfortable, and I longed to be alone, that I might compose my startled mind.”

Franz essayed to smile.

“Nay,” said she, “do not smile; it ill accords with the expression of your countenance, and I am sure it does not spring from your heart. However, promise me one thing.”

“What is it?”

“Promise me, I say.”

“I will do anything you desire, except relinquish my determination of finding out who this man is. I have more reasons than you can imagine for desiring to know who he is, from whence he came, and whither he is going.”

“Where he comes from I am ignorant; but I can readily tell you where he is going to, and that is down below, without the least doubt.”

“Let us only speak of the promise you wished me to make,” said Franz.

“Well, then, you must give me your word to return immediately to your hotel, and make no attempt to follow this man tonight. There are certain affinities between the persons we quit and those we meet afterwards. For heaven’s sake, do not serve as a conductor between that man and me. Pursue your chase after him tomorrow as eagerly as you please; but never bring him near me, if you would not see me die of terror. And now, good-night; go to your rooms, and try to sleep away all recollections of this evening. For my own part, I am quite sure I shall not be able to close my eyes.”

So saying, the countess quitted Franz, leaving him unable to decide whether she were merely amusing herself at his expense, or whether her fears and agitations were genuine.

Upon his return to the hotel, Franz found Albert in his dressing-gown and slippers, listlessly extended on a sofa, smoking a cigar.

“My dear fellow!” cried he, springing up, “is it really you? Why, I did not expect to see you before tomorrow.”

“My dear Albert,” replied Franz, “I am glad of this opportunity to tell you, once and forever, that you entertain a most erroneous notion concerning Italian women. I should have thought the continual failures you have met with in all your own love affairs might have taught you better by this time.”

“Upon my soul, these women would puzzle the very Devil to read them aright. Why, here—they give you their hand—they press yours in return—they keep up a whispering conversation—permit you to accompany them home. Why, if a Parisian were to indulge in a quarter of these marks of flattering attention, her reputation would be gone forever.”

“And the very reason why the women of this fine country, ‘where sounds the si,’ as Dante writes, put so little restraint on their words and actions, is because they live so much in public, and have really nothing to conceal. Besides, you must have perceived that the countess was really alarmed.”

“At what? At the sight of that respectable gentleman sitting opposite to us in the same box with the lovely Greek girl? Now, for my part, I met them in the lobby after the conclusion of the piece; and hang me, if I can guess where you took your notions of the other world from. I can assure you that this hobgoblin of yours is a deuced fine-looking fellow—admirably dressed. Indeed, I feel quite sure, from the cut of his clothes, they are made by a first-rate Paris tailor—probably Blin or Humann. He was rather too pale, certainly; but then, you know, paleness is always looked upon as a strong proof of aristocratic descent and distinguished breeding.”

Franz smiled; for he well remembered that Albert particularly prided himself on the entire absence of color in his own complexion.

“Well, that tends to confirm my own ideas,” said Franz, “that the countess’s suspicions were destitute alike of sense and reason. Did he speak in your hearing? and did you catch any of his words?”

“I did; but they were uttered in the Romaic dialect. I knew that from the mixture of Greek words. I don’t know whether I ever told you that when I was at college I was rather—rather strong in Greek.”

“He spoke the Romaic language, did he?”

“I think so.”

“That settles it,” murmured Franz. “’Tis he, past all doubt.”

“What do you say?”

“Nothing, nothing. But tell me, what were you thinking about when I came in?”

“Oh, I was arranging a little surprise for you.”

“Indeed. Of what nature?”

“Why, you know it is quite impossible to procure a carriage.”

“Certainly; and I also know that we have done all that human means afforded to endeavor to get one.”

“Now, then, in this difficulty a bright idea has flashed across my brain.”

Franz looked at Albert as though he had not much confidence in the suggestions of his imagination.

“I tell you what, M. Franz,” cried Albert, “you deserve to be called out for such a misgiving and incredulous glance as that you were pleased to bestow on me just now.”

“And I promise to give you the satisfaction of a gentleman if your scheme turns out as ingenious as you assert.”

“Well, then, hearken to me.”

“I listen.”

“You agree, do you not, that obtaining a carriage is out of the question?”

“I do.”

“Neither can we procure horses?”

“True; we have offered any sum, but have failed.”

“Well, now, what do you say to a cart? I dare say such a thing might be had.”

“Very possibly.”

“And a pair of oxen?”

“As easily found as the cart.”

“Then you see, my good fellow, with a cart and a couple of oxen our business can be managed. The cart must be tastefully ornamented; and if you and I dress ourselves as Neapolitan reapers, we may get up a striking tableau, after the manner of that splendid picture by Léopold Robert. It would add greatly to the effect if the countess would join us in the costume of a peasant from Puzzoli or Sorrento. Our group would then be quite complete, more especially as the countess is quite beautiful enough to represent a Madonna.”

“Well,” said Franz, “this time, M. Albert, I am bound to give you credit for having hit upon a most capital idea.”

“And quite a national one, too,” replied Albert with gratified pride. “A mere masque borrowed from our own festivities. Ha, ha, ye Romans! you thought to make us, unhappy strangers, trot at the heels of your processions, like so many lazzaroni, because no carriages or horses are to be had in your beggarly city. But you don’t know us; when we can’t have one thing we invent another.”

“And have you communicated your triumphant idea to anybody?”

“Only to our host. Upon my return home I sent for him, and I then explained to him what I wished to procure. He assured me that nothing would be easier than to furnish all I desired. One thing I was sorry for; when I bade him have the horns of the oxen gilded, he told me there would not be time, as it would require three days to do that; so you see we must do without this little superfluity.”

“And where is he now?”

“Who?”

“Our host.”

“Gone out in search of our equipage, by tomorrow it might be too late.”

“Then he will be able to give us an answer tonight.”

“Oh, I expect him every minute.”

At this instant the door opened, and the head of Signor Pastrini appeared. “Permesso?” inquired he.

“Certainly—certainly,” cried Franz. “Come in, my host.”

“Now, then,” asked Albert eagerly, “have you found the desired cart and oxen?”

“Better than that!” replied Signor Pastrini, with the air of a man perfectly well satisfied with himself.

“Take care, my worthy host,” said Albert, “better is a sure enemy to well.”

“Let your excellencies only leave the matter to me,” returned Signor Pastrini in a tone indicative of unbounded self-confidence.

“But what have you done?” asked Franz. “Speak out, there’s a worthy fellow.”

“Your excellencies are aware,” responded the landlord, swelling with importance, “that the Count of Monte Cristo is living on the same floor with yourselves!”

“I should think we did know it,” exclaimed Albert, “since it is owing to that circumstance that we are packed into these small rooms, like two poor students in the back streets of Paris.”

“When, then, the Count of Monte Cristo, hearing of the dilemma in which you are placed, has sent to offer you seats in his carriage and two places at his windows in the Palazzo Rospoli.” The friends looked at each other with unutterable surprise.

“But do you think,” asked Albert, “that we ought to accept such offers from a perfect stranger?”

“What sort of person is this Count of Monte Cristo?” asked Franz of his host.

“A very great nobleman, but whether Maltese or Sicilian I cannot exactly say; but this I know, that he is noble as a Borghese and rich as a gold mine.”

“It seems to me,” said Franz, speaking in an undertone to Albert, “that if this person merited the high panegyrics of our landlord, he would have conveyed his invitation through another channel, and not permitted it to be brought to us in this unceremonious way. He would have written—or——”

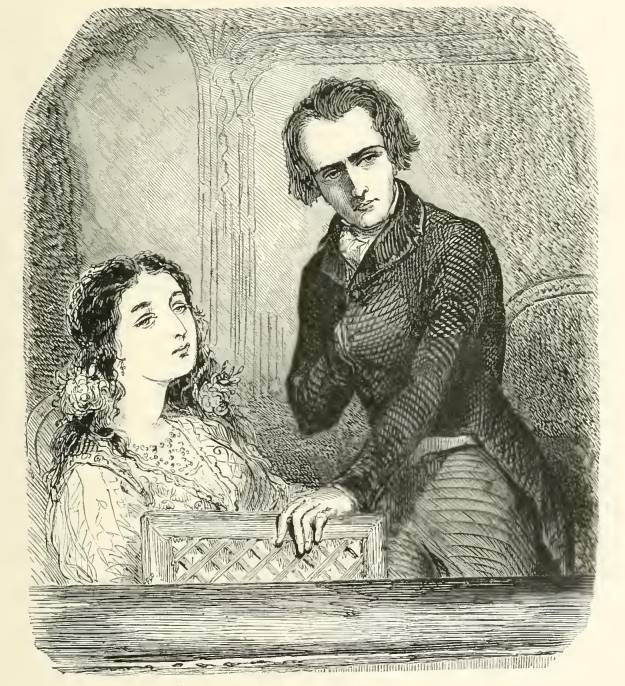

At this instant someone knocked at the door.

“Come in,” said Franz.

A servant, wearing a livery of considerable style and richness, appeared at the threshold, and, placing two cards in the landlord’s hands, who forthwith presented them to the two young men, he said:

“Please to deliver these, from the Count of Monte Cristo to Vicomte Albert de Morcerf and M. Franz d’Épinay. The Count of Monte Cristo,” continued the servant, “begs these gentlemen’s permission to wait upon them as their neighbor, and he will be honored by an intimation of what time they will please to receive him.”

“Faith, Franz,” whispered Albert, “there is not much to find fault with here.”

“Tell the count,” replied Franz, “that we will do ourselves the pleasure of calling on him.”

The servant bowed and retired.

“That is what I call an elegant mode of attack,” said Albert, “You were quite correct in what you said, Signor Pastrini. The Count of Monte Cristo is unquestionably a man of first-rate breeding and knowledge of the world.”

“Then you accept his offer?” said the host.

“Of course we do,” replied Albert. “Still, I must own I am sorry to be obliged to give up the cart and the group of reapers—it would have produced such an effect! And were it not for the windows at the Palazzo Rospoli, by way of recompense for the loss of our beautiful scheme, I don’t know but what I should have held on by my original plan. What say you, Franz?”

“Oh, I agree with you; the windows in the Palazzo Rospoli alone decided me.”

The truth was, that the mention of two places in the Palazzo Rospoli had recalled to Franz the conversation he had overheard the preceding evening in the ruins of the Colosseum between the mysterious unknown and the Transteverin, in which the stranger in the cloak had undertaken to obtain the freedom of a condemned criminal; and if this muffled-up individual proved (as Franz felt sure he would) the same as the person he had just seen in the Teatro Argentina, then he should be able to establish his identity, and also to prosecute his researches respecting him with perfect facility and freedom.

Franz passed the night in confused dreams respecting the two meetings he had already had with his mysterious tormentor, and in waking speculations as to what the morrow would produce. The next day must clear up every doubt; and unless his near neighbor and would-be friend, the Count of Monte Cristo, possessed the ring of Gyges, and by its power was able to render himself invisible, it was very certain he could not escape this time.

Eight o’clock found Franz up and dressed, while Albert, who had not the same motives for early rising, was still soundly asleep. The first act of Franz was to summon his landlord, who presented himself with his accustomed obsequiousness.

“Pray, Signor Pastrini,” asked Franz, “is not some execution appointed to take place today?”

“Yes, your excellency; but if your reason for inquiry is that you may procure a window to view it from, you are much too late.”

“Oh, no,” answered Franz, “I had no such intention; and even if I had felt a wish to witness the spectacle, I might have done so from Monte Pincio; could I not?”

“Ah!” exclaimed mine host, “I did not think it likely your excellency would have chosen to mingle with such a rabble as are always collected on that hill, which, indeed, they consider as exclusively belonging to themselves.”

“Very possibly I may not go,” answered Franz; “but in case I feel disposed, give me some particulars of today’s executions.”

“What particulars would your excellency like to hear?”

“Why, the number of persons condemned to suffer, their names, and description of the death they are to die.”

“That happens just lucky, your excellency! Only a few minutes ago they brought me the tavolettas.”

“What are they?”

“Sort of wooden tablets hung up at the corners of streets the evening before an execution, on which is pasted up a paper containing the names of the condemned persons, their crimes, and mode of punishment. The reason for so publicly announcing all this is, that all good and faithful Catholics may offer up their prayers for the unfortunate culprits, and, above all, beseech of Heaven to grant them a sincere repentance.”

“And these tablets are brought to you that you may add your prayers to those of the faithful, are they?” asked Franz somewhat incredulously.

“Oh, dear, no, your excellency! I have not time for anybody’s affairs but my own and those of my honorable guests; but I make an agreement with the man who pastes up the papers, and he brings them to me as he would the playbills, that in case any person staying at my hotel should like to witness an execution, he may obtain every requisite information concerning the time and place etc.”

“Upon my word, that is a most delicate attention on your part, Signor Pastrini,” cried Franz.

“Why, your excellency,” returned the landlord, chuckling and rubbing his hands with infinite complacency, “I think I may take upon myself to say I neglect nothing to deserve the support and patronage of the noble visitors to this poor hotel.”

“I see that plainly enough, my most excellent host, and you may rely upon me to proclaim so striking a proof of your attention to your guests wherever I go. Meanwhile, oblige me by a sight of one of these tavolettas.”

“Nothing can be easier than to comply with your excellency’s wish,” said the landlord, opening the door of the chamber; “I have caused one to be placed on the landing, close by your apartment.”

Then, taking the tablet from the wall, he handed it to Franz, who read as follows:

“‘The public is informed that on Wednesday, February 23rd, being the first day of the Carnival, executions will take place in the Piazza del Popolo, by order of the Tribunal of the Rota, of two persons, named Andrea Rondolo, and Peppino, otherwise called Rocca Priori; the former found guilty of the murder of a venerable and exemplary priest, named Don César Torlini, canon of the church of St. John Lateran; and the latter convicted of being an accomplice of the atrocious and sanguinary bandit, Luigi Vampa, and his band. The first-named malefactor will be mazzolato, the second culprit decapitato.

“‘The prayers of all good Christians are entreated for these unfortunate men, that it may please God to awaken them to a sense of their guilt, and to grant them a hearty and sincere repentance for their crimes.’”

This was precisely what Franz had heard the evening before in the ruins of the Colosseum. No part of the programme differed,—the names of the condemned persons, their crimes, and mode of punishment, all agreed with his previous information. In all probability, therefore, the Transteverin was no other than the bandit Luigi Vampa himself, and the man shrouded in the mantle the same he had known as “Sinbad the Sailor,” but who, no doubt, was still pursuing his philanthropic expedition in Rome, as he had already done at Porto-Vecchio and Tunis.

Time was getting on, however, and Franz deemed it advisable to awaken Albert; but at the moment he prepared to proceed to his chamber, his friend entered the room in perfect costume for the day. The anticipated delights of the Carnival had so run in his head as to make him leave his pillow long before his usual hour.

“Now, my excellent Signor Pastrini,” said Franz, addressing his landlord, “since we are both ready, do you think we may proceed at once to visit the Count of Monte Cristo?”

“Most assuredly,” replied he. “The Count of Monte Cristo is always an early riser; and I can answer for his having been up these two hours.”

“Then you really consider we shall not be intruding if we pay our respects to him directly?”

“Oh, I am quite sure. I will take all the blame on myself if you find I have led you into an error.”

“Well, then, if it be so, are you ready, Albert?”

“Perfectly.”

“Let us go and return our best thanks for his courtesy.”

“Yes, let us do so.”

The landlord preceded the friends across the landing, which was all that separated them from the apartments of the count, rang at the bell, and, upon the door being opened by a servant, said:

“I signori Francesi.”

The domestic bowed respectfully, and invited them to enter. They passed through two rooms, furnished in a luxurious manner they had not expected to see under the roof of Signor Pastrini, and were shown into an elegantly fitted-up drawing-room. The richest Turkey carpets covered the floor, and the softest and most inviting couches, easy-chairs, and sofas, offered their high-piled and yielding cushions to such as desired repose or refreshment. Splendid paintings by the first masters were ranged against the walls, intermingled with magnificent trophies of war, while heavy curtains of costly tapestry were suspended before the different doors of the room.

“If your excellencies will please to be seated,” said the man, “I will let the count know that you are here.”

And with these words he disappeared behind one of the tapestried portières. As the door opened, the sound of a guzla reached the ears of the young men, but was almost immediately lost, for the rapid closing of the door merely allowed one rich swell of harmony to enter. Franz and Albert looked inquiringly at each other, then at the gorgeous furnishings of the apartment. Everything seemed more magnificent at a second view than it had done at their first rapid survey.

“Well,” said Franz to his friend, “what think you of all this?”

“Why, upon my soul, my dear fellow, it strikes me that our elegant and attentive neighbor must either be some successful stock-jobber who has speculated in the fall of the Spanish funds, or some prince travelling incog.”

“Hush, hush!” replied Franz; “we shall ascertain who and what he is—he comes!”

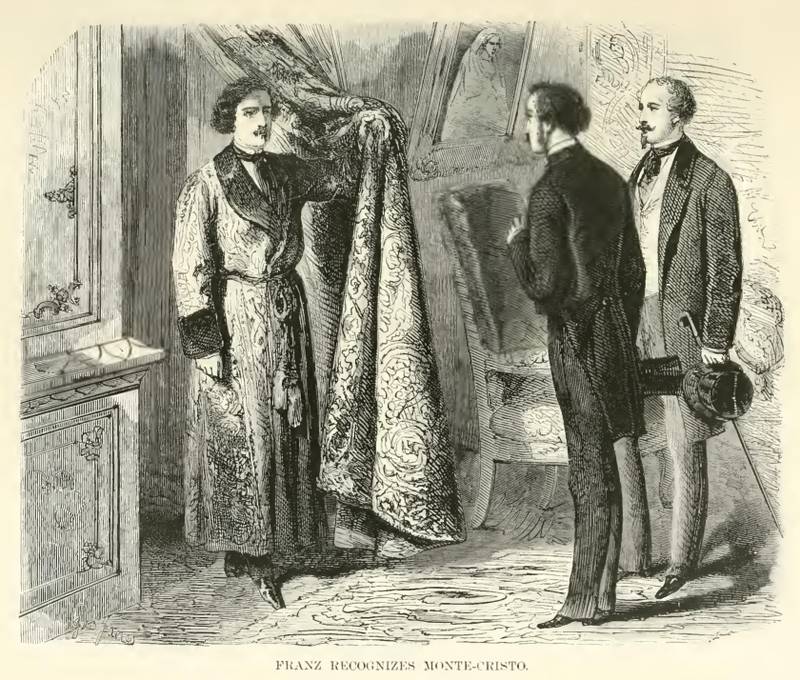

As Franz spoke, he heard the sound of a door turning on its hinges, and almost immediately afterwards the tapestry was drawn aside, and the owner of all these riches stood before the two young men. Albert instantly rose to meet him, but Franz remained, in a manner, spellbound on his chair; for in the person of him who had just entered he recognized not only the mysterious visitant to the Colosseum, and the occupant of the box at the Teatro Argentina, but also his extraordinary host of Monte Cristo.

Gentlemen,” said the Count of Monte Cristo as he entered, “I pray you excuse me for suffering my visit to be anticipated; but I feared to disturb you by presenting myself earlier at your apartments; besides, you sent me word that you would come to me, and I have held myself at your disposal.”

“Franz and I have to thank you a thousand times, count,” returned Albert; “you extricated us from a great dilemma, and we were on the point of inventing a very fantastic vehicle when your friendly invitation reached us.”

“Indeed,” returned the count, motioning the two young men to sit down. “It was the fault of that blockhead Pastrini, that I did not sooner assist you in your distress. He did not mention a syllable of your embarrassment to me, when he knows that, alone and isolated as I am, I seek every opportunity of making the acquaintance of my neighbors. As soon as I learned I could in any way assist you, I most eagerly seized the opportunity of offering my services.”

The two young men bowed. Franz had, as yet, found nothing to say; he had come to no determination, and as nothing in the count’s manner manifested the wish that he should recognize him, he did not know whether to make any allusion to the past, or wait until he had more proof; besides, although sure it was he who had been in the box the previous evening, he could not be equally positive that this was the man he had seen at the Colosseum. He resolved, therefore, to let things take their course without making any direct overture to the count. Moreover, he had this advantage, he was master of the count’s secret, while the count had no hold on Franz, who had nothing to conceal. However, he resolved to lead the conversation to a subject which might possibly clear up his doubts.

“Count,” said he, “you have offered us places in your carriage, and at your windows in the Rospoli Palace. Can you tell us where we can obtain a sight of the Piazza del Popolo?”

“Ah,” said the count negligently, looking attentively at Morcerf, “is there not something like an execution upon the Piazza del Popolo?”

“Yes,” returned Franz, finding that the count was coming to the point he wished.

“Stay, I think I told my steward yesterday to attend to this; perhaps I can render you this slight service also.”

He extended his hand, and rang the bell thrice.

“Did you ever occupy yourself,” said he to Franz, “with the employment of time and the means of simplifying the summoning your servants? I have. When I ring once, it is for my valet; twice, for my majordomo; thrice, for my steward,—thus I do not waste a minute or a word. Here he is.”

A man of about forty-five or fifty entered, exactly resembling the smuggler who had introduced Franz into the cavern; but he did not appear to recognize him. It was evident he had his orders.

“Monsieur Bertuccio,” said the count, “you have procured me windows looking on the Piazza del Popolo, as I ordered you yesterday.”

“Yes, excellency,” returned the steward; “but it was very late.”

“Did I not tell you I wished for one?” replied the count, frowning.

“And your excellency has one, which was let to Prince Lobanieff; but I was obliged to pay a hundred——”

“That will do—that will do, Monsieur Bertuccio; spare these gentlemen all such domestic arrangements. You have the window, that is sufficient. Give orders to the coachman; and be in readiness on the stairs to conduct us to it.”

The steward bowed, and was about to quit the room.

“Ah!” continued the count, “be good enough to ask Pastrini if he has received the tavoletta, and if he can send us an account of the execution.”

“There is no need to do that,” said Franz, taking out his tablets; “for I saw the account, and copied it down.”

“Very well, you can retire, M. Bertuccio; I need you no longer. Let us know when breakfast is ready. These gentlemen,” added he, turning to the two friends, “will, I trust, do me the honor to breakfast with me?”

“But, my dear count,” said Albert, “we shall abuse your kindness.”

“Not at all; on the contrary, you will give me great pleasure. You will, one or other of you, perhaps both, return it to me at Paris. M. Bertuccio, lay covers for three.”

He then took Franz’s tablets out of his hand. “‘We announce,’ he read, in the same tone with which he would have read a newspaper, ‘that today, the 23rd of February, will be executed Andrea Rondolo, guilty of murder on the person of the respected and venerated Don César Torlini, canon of the church of St. John Lateran, and Peppino, called Rocca Priori, convicted of complicity with the detestable bandit Luigi Vampa, and the men of his band.’

“Hum! ‘The first will be mazzolato, the second decapitato.’ Yes,” continued the count, “it was at first arranged in this way; but I think since yesterday some change has taken place in the order of the ceremony.”

“Really?” said Franz.

“Yes, I passed the evening at the Cardinal Rospigliosi’s, and there mention was made of something like a pardon for one of the two men.”

“For Andrea Rondolo?” asked Franz.

“No,” replied the count, carelessly; “for the other (he glanced at the tablets as if to recall the name), for Peppino, called Rocca Priori. You are thus deprived of seeing a man guillotined; but the mazzolata still remains, which is a very curious punishment when seen for the first time, and even the second, while the other, as you must know, is very simple. The mandaïa6 never fails, never trembles, never strikes thirty times ineffectually, like the soldier who beheaded the Count of Chalais, and to whose tender mercy Richelieu had doubtless recommended the sufferer. Ah,” added the count, in a contemptuous tone, “do not tell me of European punishments, they are in the infancy, or rather the old age, of cruelty.”

“Really, count,” replied Franz, “one would think that you had studied the different tortures of all the nations of the world.”

“There are, at least, few that I have not seen,” said the count coldly.

“And you took pleasure in beholding these dreadful spectacles?”

“My first sentiment was horror, the second indifference, the third curiosity.”

“Curiosity—that is a terrible word.”

“Why so? In life, our greatest preoccupation is death; is it not then, curious to study the different ways by which the soul and body can part; and how, according to their different characters, temperaments, and even the different customs of their countries, different persons bear the transition from life to death, from existence to annihilation? As for myself, I can assure you of one thing,—the more men you see die, the easier it becomes to die yourself; and in my opinion, death may be a torture, but it is not an expiation.”

“I do not quite understand you,” replied Franz; “pray explain your meaning, for you excite my curiosity to the highest pitch.”

“Listen,” said the count, and deep hatred mounted to his face, as the blood would to the face of any other. “If a man had by unheard-of and excruciating tortures destroyed your father, your mother, your betrothed,—a being who, when torn from you, left a desolation, a wound that never closes, in your breast,—do you think the reparation that society gives you is sufficient when it interposes the knife of the guillotine between the base of the occiput and the trapezal muscles of the murderer, and allows him who has caused us years of moral sufferings to escape with a few moments of physical pain?”

“Yes, I know,” said Franz, “that human justice is insufficient to console us; she can give blood in return for blood, that is all; but you must demand from her only what it is in her power to grant.”

“I will put another case to you,” continued the count; “that where society, attacked by the death of a person, avenges death by death. But are there not a thousand tortures by which a man may be made to suffer without society taking the least cognizance of them, or offering him even the insufficient means of vengeance, of which we have just spoken? Are there not crimes for which the impalement of the Turks, the augers of the Persians, the stake and the brand of the Iroquois Indians, are inadequate tortures, and which are unpunished by society? Answer me, do not these crimes exist?”

“Yes,” answered Franz; “and it is to punish them that duelling is tolerated.”

“Ah, duelling,” cried the count; “a pleasant manner, upon my soul, of arriving at your end when that end is vengeance! A man has carried off your mistress, a man has seduced your wife, a man has dishonored your daughter; he has rendered the whole life of one who had the right to expect from Heaven that portion of happiness God has promised to everyone of his creatures, an existence of misery and infamy; and you think you are avenged because you send a ball through the head, or pass a sword through the breast, of that man who has planted madness in your brain, and despair in your heart. And remember, moreover, that it is often he who comes off victorious from the strife, absolved of all crime in the eyes of the world. No, no,” continued the count, “had I to avenge myself, it is not thus I would take revenge.”

“Then you disapprove of duelling? You would not fight a duel?” asked Albert in his turn, astonished at this strange theory.

“Oh, yes,” replied the count; “understand me, I would fight a duel for a trifle, for an insult, for a blow; and the more so that, thanks to my skill in all bodily exercises, and the indifference to danger I have gradually acquired, I should be almost certain to kill my man. Oh, I would fight for such a cause; but in return for a slow, profound, eternal torture, I would give back the same, were it possible; an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, as the Orientalists say,—our masters in everything,—those favored creatures who have formed for themselves a life of dreams and a paradise of realities.”

“But,” said Franz to the count, “with this theory, which renders you at once judge and executioner of your own cause, it would be difficult to adopt a course that would forever prevent your falling under the power of the law. Hatred is blind, rage carries you away; and he who pours out vengeance runs the risk of tasting a bitter draught.”

“Yes, if he be poor and inexperienced, not if he be rich and skilful; besides, the worst that could happen to him would be the punishment of which we have already spoken, and which the philanthropic French Revolution has substituted for being torn to pieces by horses or broken on the wheel. What matters this punishment, as long as he is avenged? On my word, I almost regret that in all probability this miserable Peppino will not be beheaded, as you might have had an opportunity then of seeing how short a time the punishment lasts, and whether it is worth even mentioning; but, really this is a most singular conversation for the Carnival, gentlemen; how did it arise? Ah, I recollect, you asked for a place at my window; you shall have it; but let us first sit down to table, for here comes the servant to inform us that breakfast is ready.”

As he spoke, a servant opened one of the four doors of the apartment, saying:

“Al suo commodo!”

The two young men arose and entered the breakfast-room.

During the meal, which was excellent, and admirably served, Franz looked repeatedly at Albert, in order to observe the impressions which he doubted not had been made on him by the words of their entertainer; but whether with his usual carelessness he had paid but little attention to him, whether the explanation of the Count of Monte Cristo with regard to duelling had satisfied him, or whether the events which Franz knew of had had their effect on him alone, he remarked that his companion did not pay the least regard to them, but on the contrary ate like a man who for the last four or five months had been condemned to partake of Italian cookery—that is, the worst in the world.

As for the count, he just touched the dishes; he seemed to fulfil the duties of a host by sitting down with his guests, and awaited their departure to be served with some strange or more delicate food. This brought back to Franz, in spite of himself, the recollection of the terror with which the count had inspired the Countess G——, and her firm conviction that the man in the opposite box was a vampire.

At the end of the breakfast Franz took out his watch.

“Well,” said the count, “what are you doing?”

“You must excuse us, count,” returned Franz, “but we have still much to do.”

“What may that be?”

“We have no masks, and it is absolutely necessary to procure them.”

“Do not concern yourself about that; we have, I think, a private room in the Piazza del Popolo; I will have whatever costumes you choose brought to us, and you can dress there.”

“After the execution?” cried Franz.

“Before or after, whichever you please.”

“Opposite the scaffold?”

“The scaffold forms part of the fête.”

“Count, I have reflected on the matter,” said Franz, “I thank you for your courtesy, but I shall content myself with accepting a place in your carriage and at your window at the Rospoli Palace, and I leave you at liberty to dispose of my place at the Piazza del Popolo.”

“But I warn you, you will lose a very curious sight,” returned the count.

“You will describe it to me,” replied Franz, “and the recital from your lips will make as great an impression on me as if I had witnessed it. I have more than once intended witnessing an execution, but I have never been able to make up my mind; and you, Albert?”

“I,” replied the viscount,—“I saw Castaing executed, but I think I was rather intoxicated that day, for I had quitted college the same morning, and we had passed the previous night at a tavern.”

“Besides, it is no reason because you have not seen an execution at Paris, that you should not see one anywhere else; when you travel, it is to see everything. Think what a figure you will make when you are asked, ‘How do they execute at Rome?’ and you reply, ‘I do not know!’ And, besides, they say that the culprit is an infamous scoundrel, who killed with a log of wood a worthy canon who had brought him up like his own son. Diable! when a churchman is killed, it should be with a different weapon than a log, especially when he has behaved like a father. If you went to Spain, would you not see the bull-fights? Well, suppose it is a bull-fight you are going to see? Recollect the ancient Romans of the Circus, and the sports where they killed three hundred lions and a hundred men. Think of the eighty thousand applauding spectators, the sage matrons who took their daughters, and the charming Vestals who made with the thumb of their white hands the fatal sign that said, ‘Come, despatch the dying.’”

“Shall you go, then, Albert?” asked Franz.

“Ma foi, yes; like you, I hesitated, but the count’s eloquence decides me.”

“Let us go, then,” said Franz, “since you wish it; but on our way to the Piazza del Popolo, I wish to pass through the Corso. Is this possible, count?”

“On foot, yes, in a carriage, no.”

“I will go on foot, then.”

“Is it important that you should go that way?”

“Yes, there is something I wish to see.”

“Well, we will go by the Corso. We will send the carriage to wait for us on the Piazza del Popolo, by the Via del Babuino, for I shall be glad to pass, myself, through the Corso, to see if some orders I have given have been executed.”

“Excellency,” said a servant, opening the door, “a man in the dress of a penitent wishes to speak to you.”

“Ah! yes,” returned the count, “I know who he is, gentlemen; will you return to the salon? you will find good cigars on the centre table. I will be with you directly.”

The young men rose and returned into the salon, while the count, again apologizing, left by another door. Albert, who was a great smoker, and who had considered it no small sacrifice to be deprived of the cigars of the Café de Paris, approached the table, and uttered a cry of joy at perceiving some veritable puros.

“Well,” asked Franz, “what think you of the Count of Monte Cristo?”

“What do I think?” said Albert, evidently surprised at such a question from his companion; “I think he is a delightful fellow, who does the honors of his table admirably; who has travelled much, read much, is, like Brutus, of the Stoic school, and moreover,” added he, sending a volume of smoke up towards the ceiling, “that he has excellent cigars.”

Such was Albert’s opinion of the count, and as Franz well knew that Albert professed never to form an opinion except upon long reflection, he made no attempt to change it.

“But,” said he, “did you observe one very singular thing?”

“What?”

“How attentively he looked at you.”

“At me?”

“Yes.”

Albert reflected. “Ah,” replied he, sighing, “that is not very surprising; I have been more than a year absent from Paris, and my clothes are of a most antiquated cut; the count takes me for a provincial. The first opportunity you have, undeceive him, I beg, and tell him I am nothing of the kind.”

Franz smiled; an instant after the count entered.

“I am now quite at your service, gentlemen,” said he. “The carriage is going one way to the Piazza del Popolo, and we will go another; and, if you please, by the Corso. Take some more of these cigars, M. de Morcerf.”

“With all my heart,” returned Albert; “Italian cigars are horrible. When you come to Paris, I will return all this.”

“I will not refuse; I intend going there soon, and since you allow me, I will pay you a visit. Come, we have not any time to lose, it is half-past twelve—let us set off.”

All three descended; the coachman received his master’s orders, and drove down the Via del Babuino. While the three gentlemen walked along the Piazza di Spagna and the Via Frattina, which led directly between the Fiano and Rospoli palaces, Franz’s attention was directed towards the windows of that last palace, for he had not forgotten the signal agreed upon between the man in the mantle and the Transtevere peasant.

“Which are your windows?” asked he of the count, with as much indifference as he could assume.

“The three last,” returned he, with a negligence evidently unaffected, for he could not imagine with what intention the question was put.

Franz glanced rapidly towards the three windows. The side windows were hung with yellow damask, and the centre one with white damask and a red cross. The man in the mantle had kept his promise to the Transteverin, and there could now be no doubt that he was the count.

The three windows were still untenanted. Preparations were making on every side; chairs were placed, scaffolds were raised, and windows were hung with flags. The masks could not appear; the carriages could not move about; but the masks were visible behind the windows, the carriages, and the doors.

Franz, Albert, and the count continued to descend the Corso. As they approached the Piazza del Popolo, the crowd became more dense, and above the heads of the multitude two objects were visible: the obelisk, surmounted by a cross, which marks the centre of the square, and in front of the obelisk, at the point where the three streets, del Babuino, del Corso, and di Ripetta, meet, the two uprights of the scaffold, between which glittered the curved knife of the mandaïa.

At the corner of the street they met the count’s steward, who was awaiting his master. The window, let at an exorbitant price, which the count had doubtless wished to conceal from his guests, was on the second floor of the great palace, situated between the Via del Babuino and the Monte Pincio. It consisted, as we have said, of a small dressing-room, opening into a bedroom, and, when the door of communication was shut, the inmates were quite alone. On chairs were laid elegant masquerade costumes of blue and white satin.