He was finishing the last line when a cry behind him made him start, and the pen fell from his hand.

“Haydée,” said he, “did you read it?”

“Oh, my lord,” said she, “why are you writing thus at such an hour? Why are you bequeathing all your fortune to me? Are you going to leave me?”

“I am going on a journey, dear child,” said Monte Cristo, with an expression of infinite tenderness and melancholy; “and if any misfortune should happen to me——”

The count stopped.

“Well?” asked the young girl, with an authoritative tone the count had never observed before, and which startled him.

“Well, if any misfortune happen to me,” replied Monte Cristo, “I wish my daughter to be happy.” Haydée smiled sorrowfully, and shook her head.

“Do you think of dying, my lord?” said she.

“The wise man, my child, has said, ‘It is good to think of death.’”

“Well, if you die,” said she, “bequeath your fortune to others, for if you die I shall require nothing;” and, taking the paper, she tore it in four pieces, and threw it into the middle of the room. Then, the effort having exhausted her strength, she fell, not asleep this time, but fainting on the floor.

The count leaned over her and raised her in his arms; and seeing that sweet pale face, those lovely eyes closed, that beautiful form motionless and to all appearance lifeless, the idea occurred to him for the first time, that perhaps she loved him otherwise than as a daughter loves a father.

“Alas,” murmured he, with intense suffering, “I might, then, have been happy yet.”

Then he carried Haydée to her room, resigned her to the care of her attendants, and returning to his study, which he shut quickly this time, he again copied the destroyed will. As he was finishing, the sound of a cabriolet entering the yard was heard. Monte Cristo approached the window, and saw Maximilian and Emmanuel alight. “Good,” said he; “it was time,”—and he sealed his will with three seals.

A moment afterwards he heard a noise in the drawing-room, and went to open the door himself. Morrel was there; he had come twenty minutes before the time appointed.

“I am perhaps come too soon, count,” said he, “but I frankly acknowledge that I have not closed my eyes all night, nor has anyone in my house. I need to see you strong in your courageous assurance, to recover myself.”

Monte Cristo could not resist this proof of affection; he not only extended his hand to the young man, but flew to him with open arms.

“Morrel,” said he, “it is a happy day for me, to feel that I am beloved by such a man as you. Good-morning, Emmanuel; you will come with me then, Maximilian?”

“Did you doubt it?” said the young captain.

“But if I were wrong——”

“I watched you during the whole scene of that challenge yesterday; I have been thinking of your firmness all night, and I said to myself that justice must be on your side, or man’s countenance is no longer to be relied on.”

“But, Morrel, Albert is your friend?”

“Simply an acquaintance, sir.”

“You met on the same day you first saw me?”

“Yes, that is true; but I should not have recollected it if you had not reminded me.”

“Thank you, Morrel.” Then ringing the bell once, “Look.” said he to Ali, who came immediately, “take that to my solicitor. It is my will, Morrel. When I am dead, you will go and examine it.”

“What?” said Morrel, “you dead?”

“Yes; must I not be prepared for everything, dear friend? But what did you do yesterday after you left me?”

“I went to Tortoni’s, where, as I expected, I found Beauchamp and Château-Renaud. I own I was seeking them.”

“Why, when all was arranged?”

“Listen, count; the affair is serious and unavoidable.”

“Did you doubt it!”

“No; the offence was public, and everyone is already talking of it.”

“Well?”

“Well, I hoped to get an exchange of arms,—to substitute the sword for the pistol; the pistol is blind.”

“Have you succeeded?” asked Monte Cristo quickly, with an imperceptible gleam of hope.

“No; for your skill with the sword is so well known.”

“Ah?—who has betrayed me?”

“The skilful swordsman whom you have conquered.”

“And you failed?”

“They positively refused.”

“Morrel,” said the count, “have you ever seen me fire a pistol?”

“Never.”

“Well, we have time; look.” Monte Cristo took the pistols he held in his hand when Mercédès entered, and fixing an ace of clubs against the iron plate, with four shots he successively shot off the four sides of the club. At each shot Morrel turned pale. He examined the bullets with which Monte Cristo performed this dexterous feat, and saw that they were no larger than buckshot.

“It is astonishing,” said he. “Look, Emmanuel.” Then turning towards Monte Cristo, “Count,” said he, “in the name of all that is dear to you, I entreat you not to kill Albert!—the unhappy youth has a mother.”

“You are right,” said Monte Cristo; “and I have none.” These words were uttered in a tone which made Morrel shudder.

“You are the offended party, count.”

“Doubtless; what does that imply?”

“That you will fire first.”

“I fire first?”

“Oh, I obtained, or rather claimed that; we had conceded enough for them to yield us that.”

“And at what distance?”

“Twenty paces.” A smile of terrible import passed over the count’s lips.

“Morrel,” said he, “do not forget what you have just seen.”

“The only chance for Albert’s safety, then, will arise from your emotion.”

“I suffer from emotion?” said Monte Cristo.

“Or from your generosity, my friend; to so good a marksman as you are, I may say what would appear absurd to another.”

“What is that?”

“Break his arm—wound him—but do not kill him.”

“I will tell you, Morrel,” said the count, “that I do not need entreating to spare the life of M. de Morcerf; he shall be so well spared, that he will return quietly with his two friends, while I——”

“And you?”

“That will be another thing; I shall be brought home.”

“No, no,” cried Maximilian, quite unable to restrain his feelings.

“As I told you, my dear Morrel, M. de Morcerf will kill me.”

Morrel looked at him in utter amazement. “But what has happened, then, since last evening, count?”

“The same thing that happened to Brutus the night before the battle of Philippi; I have seen a ghost.”

“And that ghost——”

“Told me, Morrel, that I had lived long enough.”

Maximilian and Emmanuel looked at each other. Monte Cristo drew out his watch. “Let us go,” said he; “it is five minutes past seven, and the appointment was for eight o’clock.”

A carriage was in readiness at the door. Monte Cristo stepped into it with his two friends. He had stopped a moment in the passage to listen at a door, and Maximilian and Emmanuel, who had considerately passed forward a few steps, thought they heard him answer by a sigh to a sob from within. As the clock struck eight they drove up to the place of meeting.

“We are first,” said Morrel, looking out of the window.

“Excuse me, sir,” said Baptistin, who had followed his master with indescribable terror, “but I think I see a carriage down there under the trees.”

Monte Cristo sprang lightly from the carriage, and offered his hand to assist Emmanuel and Maximilian. The latter retained the count’s hand between his.

“I like,” said he, “to feel a hand like this, when its owner relies on the goodness of his cause.”

“It seems to me,” said Emmanuel, “that I see two young men down there, who are evidently, waiting.”

Monte Cristo drew Morrel a step or two behind his brother-in-law.

“Maximilian,” said he, “are your affections disengaged?” Morrel looked at Monte Cristo with astonishment. “I do not seek your confidence, my dear friend. I only ask you a simple question; answer it;—that is all I require.”

“I love a young girl, count.”

“Do you love her much?”

“More than my life.”

“Another hope defeated!” said the count. Then, with a sigh, “Poor Haydée!” murmured he.

“To tell the truth, count, if I knew less of you, I should think that you were less brave than you are.”

“Because I sigh when thinking of someone I am leaving? Come, Morrel, it is not like a soldier to be so bad a judge of courage. Do I regret life? What is it to me, who have passed twenty years between life and death? Moreover, do not alarm yourself, Morrel; this weakness, if it is such, is betrayed to you alone. I know the world is a drawing-room, from which we must retire politely and honestly; that is, with a bow, and our debts of honor paid.”

“That is to the purpose. Have you brought your arms?”

“I?—what for? I hope these gentlemen have theirs.”

“I will inquire,” said Morrel.

“Do; but make no treaty—you understand me?”

“You need not fear.” Morrel advanced towards Beauchamp and Château-Renaud, who, seeing his intention, came to meet him. The three young men bowed to each other courteously, if not affably.

“Excuse me, gentlemen,” said Morrel, “but I do not see M. de Morcerf.”

“He sent us word this morning,” replied Château-Renaud, “that he would meet us on the ground.”

“Ah,” said Morrel. Beauchamp pulled out his watch.

“It is only five minutes past eight,” said he to Morrel; “there is not much time lost yet.”

“Oh, I made no allusion of that kind,” replied Morrel.

“There is a carriage coming,” said Château-Renaud. It advanced rapidly along one of the avenues leading towards the open space where they were assembled.

“You are doubtless provided with pistols, gentlemen? M. de Monte Cristo yields his right of using his.”

“We had anticipated this kindness on the part of the count,” said Beauchamp, “and I have brought some weapons which I bought eight or ten days since, thinking to want them on a similar occasion. They are quite new, and have not yet been used. Will you examine them.”

“Oh, M. Beauchamp, if you assure me that M. de Morcerf does not know these pistols, you may readily believe that your word will be quite sufficient.”

“Gentlemen,” said Château-Renaud, “it is not Morcerf coming in that carriage;—faith, it is Franz and Debray!”

The two young men he announced were indeed approaching. “What chance brings you here, gentlemen?” said Château-Renaud, shaking hands with each of them.

“Because,” said Debray, “Albert sent this morning to request us to come.” Beauchamp and Château-Renaud exchanged looks of astonishment. “I think I understand his reason,” said Morrel.

“What is it?”

“Yesterday afternoon I received a letter from M. de Morcerf, begging me to attend the Opera.”

“And I,” said Debray.

“And I also,” said Franz.

“And we, too,” added Beauchamp and Château-Renaud.

“Having wished you all to witness the challenge, he now wishes you to be present at the combat.”

“Exactly so,” said the young men; “you have probably guessed right.”

“But, after all these arrangements, he does not come himself,” said Château-Renaud. “Albert is ten minutes after time.”

“There he comes,” said Beauchamp, “on horseback, at full gallop, followed by a servant.”

“How imprudent,” said Château-Renaud, “to come on horseback to fight a duel with pistols, after all the instructions I had given him.”

“And besides,” said Beauchamp, “with a collar above his cravat, an open coat and white waistcoat! Why has he not painted a spot upon his heart?—it would have been more simple.”

Meanwhile Albert had arrived within ten paces of the group formed by the five young men. He jumped from his horse, threw the bridle on his servant’s arms, and joined them. He was pale, and his eyes were red and swollen; it was evident that he had not slept. A shade of melancholy gravity overspread his countenance, which was not natural to him.

“I thank you, gentlemen,” said he, “for having complied with my request; I feel extremely grateful for this mark of friendship.” Morrel had stepped back as Morcerf approached, and remained at a short distance. “And to you also, M. Morrel, my thanks are due. Come, there cannot be too many.”

“Sir,” said Maximilian, “you are not perhaps aware that I am M. de Monte Cristo’s friend?”

“I was not sure, but I thought it might be so. So much the better; the more honorable men there are here the better I shall be satisfied.”

“M. Morrel,” said Château-Renaud, “will you apprise the Count of Monte Cristo that M. de Morcerf is arrived, and we are at his disposal?”

Morrel was preparing to fulfil his commission. Beauchamp had meanwhile drawn the box of pistols from the carriage.

“Stop, gentlemen,” said Albert; “I have two words to say to the Count of Monte Cristo.”

“In private?” asked Morrel.

“No, sir; before all who are here.”

Albert’s witnesses looked at each other. Franz and Debray exchanged some words in a whisper, and Morrel, rejoiced at this unexpected incident, went to fetch the count, who was walking in a retired path with Emmanuel.

“What does he want with me?” said Monte Cristo.

“I do not know, but he wishes to speak to you.”

“Ah?” said Monte Cristo, “I trust he is not going to tempt me by some fresh insult!”

“I do not think that such is his intention,” said Morrel.

The count advanced, accompanied by Maximilian and Emmanuel. His calm and serene look formed a singular contrast to Albert’s grief-stricken face, who approached also, followed by the other four young men.

When at three paces distant from each other, Albert and the count stopped.

“Approach, gentlemen,” said Albert; “I wish you not to lose one word of what I am about to have the honor of saying to the Count of Monte Cristo, for it must be repeated by you to all who will listen to it, strange as it may appear to you.”

“Proceed, sir,” said the count.

“Sir,” said Albert, at first with a tremulous voice, but which gradually became firmer, “I reproached you with exposing the conduct of M. de Morcerf in Epirus, for guilty as I knew he was, I thought you had no right to punish him; but I have since learned that you had that right. It is not Fernand Mondego’s treachery towards Ali Pasha which induces me so readily to excuse you, but the treachery of the fisherman Fernand towards you, and the almost unheard-of miseries which were its consequences; and I say, and proclaim it publicly, that you were justified in revenging yourself on my father, and I, his son, thank you for not using greater severity.”

Had a thunderbolt fallen in the midst of the spectators of this unexpected scene, it would not have surprised them more than did Albert’s declaration. As for Monte Cristo, his eyes slowly rose towards heaven with an expression of infinite gratitude. He could not understand how Albert’s fiery nature, of which he had seen so much among the Roman bandits, had suddenly stooped to this humiliation. He recognized the influence of Mercédès, and saw why her noble heart had not opposed the sacrifice she knew beforehand would be useless.

“Now, sir,” said Albert, “if you think my apology sufficient, pray give me your hand. Next to the merit of infallibility which you appear to possess, I rank that of candidly acknowledging a fault. But this confession concerns me only. I acted well as a man, but you have acted better than man. An angel alone could have saved one of us from death—that angel came from heaven, if not to make us friends (which, alas, fatality renders impossible), at least to make us esteem each other.”

Monte Cristo, with moistened eye, heaving breast, and lips half open, extended to Albert a hand which the latter pressed with a sentiment resembling respectful fear.

“Gentlemen,” said he, “M. de Monte Cristo receives my apology. I had acted hastily towards him. Hasty actions are generally bad ones. Now my fault is repaired. I hope the world will not call me cowardly for acting as my conscience dictated. But if anyone should entertain a false opinion of me,” added he, drawing himself up as if he would challenge both friends and enemies, “I shall endeavor to correct his mistake.”

“What happened during the night?” asked Beauchamp of Château-Renaud; “we appear to make a very sorry figure here.”

“In truth, what Albert has just done is either very despicable or very noble,” replied the baron.

“What can it mean?” said Debray to Franz.

“The Count of Monte Cristo acts dishonorably to M. de Morcerf, and is justified by his son! Had I ten Yaninas in my family, I should only consider myself the more bound to fight ten times.”

As for Monte Cristo, his head was bent down, his arms were powerless. Bowing under the weight of twenty-four years’ reminiscences, he thought not of Albert, of Beauchamp, of Château-Renaud, or of any of that group; but he thought of that courageous woman who had come to plead for her son’s life, to whom he had offered his, and who had now saved it by the revelation of a dreadful family secret, capable of destroying forever in that young man’s heart every feeling of filial piety.

“Providence still,” murmured he; “now only am I fully convinced of being the emissary of God!”

The Count of Monte Cristo bowed to the five young men with a melancholy and dignified smile, and got into his carriage with Maximilian and Emmanuel. Albert, Beauchamp, and Château-Renaud remained alone. Albert looked at his two friends, not timidly, but in a way that appeared to ask their opinion of what he had just done.

“Indeed, my dear friend,” said Beauchamp first, who had either the most feeling or the least dissimulation, “allow me to congratulate you; this is a very unhoped-for conclusion of a very disagreeable affair.”

Albert remained silent and wrapped in thought. Château-Renaud contented himself with tapping his boot with his flexible cane.

“Are we not going?” said he, after this embarrassing silence.

“When you please,” replied Beauchamp; “allow me only to compliment M. de Morcerf, who has given proof today of rare chivalric generosity.”

“Oh, yes,” said Château-Renaud.

“It is magnificent,” continued Beauchamp, “to be able to exercise so much self-control!”

“Assuredly; as for me, I should have been incapable of it,” said Château-Renaud, with most significant coolness.

“Gentlemen,” interrupted Albert, “I think you did not understand that something very serious had passed between M. de Monte Cristo and myself.”

“Possibly, possibly,” said Beauchamp immediately; “but every simpleton would not be able to understand your heroism, and sooner or later you will find yourself compelled to explain it to them more energetically than would be convenient to your bodily health and the duration of your life. May I give you a friendly counsel? Set out for Naples, the Hague, or St. Petersburg—calm countries, where the point of honor is better understood than among our hot-headed Parisians. Seek quietude and oblivion, so that you may return peaceably to France after a few years. Am I not right, M. de Château-Renaud?”

“That is quite my opinion,” said the gentleman; “nothing induces serious duels so much as a duel forsworn.”

“Thank you, gentlemen,” replied Albert, with a smile of indifference; “I shall follow your advice—not because you give it, but because I had before intended to quit France. I thank you equally for the service you have rendered me in being my seconds. It is deeply engraved on my heart, and, after what you have just said, I remember that only.”

Château-Renaud and Beauchamp looked at each other; the impression was the same on both of them, and the tone in which Morcerf had just expressed his thanks was so determined that the position would have become embarrassing for all if the conversation had continued.

“Good-bye, Albert,” said Beauchamp suddenly, carelessly extending his hand to the young man. The latter did not appear to arouse from his lethargy; in fact, he did not notice the offered hand.

“Good-bye,” said Château-Renaud in his turn, keeping his little cane in his left hand, and saluting with his right.

Albert’s lips scarcely whispered “Good-bye,” but his look was more explicit; it expressed a whole poem of restrained anger, proud disdain, and generous indignation. He preserved his melancholy and motionless position for some time after his two friends had regained their carriage; then suddenly unfastening his horse from the little tree to which his servant had tied it, he mounted and galloped off in the direction of Paris.

In a quarter of an hour he was entering the house in the Rue du Helder. As he alighted, he thought he saw his father’s pale face behind the curtain of the count’s bedroom. Albert turned away his head with a sigh, and went to his own apartments. He cast one lingering look on all the luxuries which had rendered life so easy and so happy since his infancy; he looked at the pictures, whose faces seemed to smile, and the landscapes, which appeared painted in brighter colors. Then he took away his mother’s portrait, with its oaken frame, leaving the gilt frame from which he took it black and empty. Then he arranged all his beautiful Turkish arms, his fine English guns, his Japanese china, his cups mounted in silver, his artistic bronzes by Feuchères or Barye; examined the cupboards, and placed the key in each; threw into a drawer of his secretaire, which he left open, all the pocket-money he had about him, and with it the thousand fancy jewels from his vases and his jewel-boxes; then he made an exact inventory of everything, and placed it in the most conspicuous part of the table, after putting aside the books and papers which had collected there.

At the beginning of this work, his servant, notwithstanding orders to the contrary, came to his room.

“What do you want?” asked he, with a more sorrowful than angry tone.

“Pardon me, sir,” replied the valet; “you had forbidden me to disturb you, but the Count of Morcerf has called me.”

“Well!” said Albert.

“I did not like to go to him without first seeing you.”

“Why?”

“Because the count is doubtless aware that I accompanied you to the meeting this morning.”

“It is probable,” said Albert.

“And since he has sent for me, it is doubtless to question me on what happened there. What must I answer?”

“The truth.”

“Then I shall say the duel did not take place?”

“You will say I apologized to the Count of Monte Cristo. Go.”

The valet bowed and retired, and Albert returned to his inventory. As he was finishing this work, the sound of horses prancing in the yard, and the wheels of a carriage shaking his window, attracted his attention. He approached the window, and saw his father get into it, and drive away. The door was scarcely closed when Albert bent his steps to his mother’s room; and, no one being there to announce him, he advanced to her bedchamber, and distressed by what he saw and guessed, stopped for one moment at the door.

As if the same idea had animated these two beings, Mercédès was doing the same in her apartments that he had just done in his. Everything was in order,—laces, dresses, jewels, linen, money, all were arranged in the drawers, and the countess was carefully collecting the keys. Albert saw all these preparations and understood them, and exclaiming, “My mother!” he threw his arms around her neck.

The artist who could have depicted the expression of these two countenances would certainly have made of them a beautiful picture. All these proofs of an energetic resolution, which Albert did not fear on his own account, alarmed him for his mother. “What are you doing?” asked he.

“What were you doing?” replied she.

“Oh, my mother!” exclaimed Albert, so overcome he could scarcely speak; “it is not the same with you and me—you cannot have made the same resolution I have, for I have come to warn you that I bid adieu to your house, and—and to you.”

“I also,” replied Mercédès, “am going, and I acknowledge I had depended on your accompanying me; have I deceived myself?”

“Mother,” said Albert with firmness. “I cannot make you share the fate I have planned for myself. I must live henceforth without rank and fortune, and to begin this hard apprenticeship I must borrow from a friend the loaf I shall eat until I have earned one. So, my dear mother, I am going at once to ask Franz to lend me the small sum I shall require to supply my present wants.”

“You, my poor child, suffer poverty and hunger? Oh, do not say so; it will break my resolutions.”

“But not mine, mother,” replied Albert. “I am young and strong; I believe I am courageous, and since yesterday I have learned the power of will. Alas, my dear mother, some have suffered so much, and yet live, and have raised a new fortune on the ruin of all the promises of happiness which heaven had made them—on the fragments of all the hope which God had given them! I have seen that, mother; I know that from the gulf in which their enemies have plunged them they have risen with so much vigor and glory that in their turn they have ruled their former conquerors, and have punished them. No, mother; from this moment I have done with the past, and accept nothing from it—not even a name, because you can understand that your son cannot bear the name of a man who ought to blush for it before another.”

“Albert, my child,” said Mercédès, “if I had a stronger heart, that is the counsel I would have given you; your conscience has spoken when my voice became too weak; listen to its dictates. You had friends, Albert; break off their acquaintance. But do not despair; you have life before you, my dear Albert, for you are yet scarcely twenty-two years old; and as a pure heart like yours wants a spotless name, take my father’s—it was Herrera. I am sure, my dear Albert, whatever may be your career, you will soon render that name illustrious. Then, my son, return to the world still more brilliant because of your former sorrows; and if I am wrong, still let me cherish these hopes, for I have no future to look forward to. For me the grave opens when I pass the threshold of this house.”

“I will fulfil all your wishes, my dear mother,” said the young man. “Yes, I share your hopes; the anger of Heaven will not pursue us, since you are pure and I am innocent. But, since our resolution is formed, let us act promptly. M. de Morcerf went out about half an hour ago; the opportunity is favorable to avoid an explanation.”

“I am ready, my son,” said Mercédès.

Albert ran to fetch a carriage. He recollected that there was a small furnished house to let in the Rue des Saints-Pères, where his mother would find a humble but decent lodging, and thither he intended conducting the countess. As the carriage stopped at the door, and Albert was alighting, a man approached and gave him a letter.

Albert recognized the bearer. “From the count,” said Bertuccio. Albert took the letter, opened, and read it, then looked round for Bertuccio, but he was gone.

He returned to Mercédès with tears in his eyes and heaving breast, and without uttering a word he gave her the letter. Mercédès read:

“Albert,—While showing you that I have discovered your plans, I hope also to convince you of my delicacy. You are free, you leave the count’s house, and you take your mother to your home; but reflect, Albert, you owe her more than your poor noble heart can pay her. Keep the struggle for yourself, bear all the suffering, but spare her the trial of poverty which must accompany your first efforts; for she deserves not even the shadow of the misfortune which has this day fallen on her, and Providence is not willing that the innocent should suffer for the guilty. I know you are going to leave the Rue du Helder without taking anything with you. Do not seek to know how I discovered it; I know it—that is sufficient.

“Now, listen, Albert. Twenty-four years ago I returned, proud and joyful, to my country. I had a betrothed, Albert, a lovely girl whom I adored, and I was bringing to my betrothed a hundred and fifty louis, painfully amassed by ceaseless toil. This money was for her; I destined it for her, and, knowing the treachery of the sea I buried our treasure in the little garden of the house my father lived in at Marseilles, on the Allées de Meilhan. Your mother, Albert, knows that poor house well. A short time since I passed through Marseilles, and went to see the old place, which revived so many painful recollections; and in the evening I took a spade and dug in the corner of the garden where I had concealed my treasure. The iron box was there—no one had touched it—under a beautiful fig-tree my father had planted the day I was born, which overshadowed the spot. Well, Albert, this money, which was formerly designed to promote the comfort and tranquillity of the woman I adored, may now, through strange and painful circumstances, be devoted to the same purpose.

“Oh, feel for me, who could offer millions to that poor woman, but who return her only the piece of black bread forgotten under my poor roof since the day I was torn from her I loved. You are a generous man, Albert, but perhaps you may be blinded by pride or resentment; if you refuse me, if you ask another for what I have a right to offer you, I will say it is ungenerous of you to refuse the life of your mother at the hands of a man whose father was allowed by your father to die in all the horrors of poverty and despair.”

Albert stood pale and motionless to hear what his mother would decide after she had finished reading this letter. Mercédès turned her eyes with an ineffable look towards heaven.

“I accept it,” said she; “he has a right to pay the dowry, which I shall take with me to some convent!”

Putting the letter in her bosom, she took her son’s arm, and with a firmer step than she even herself expected she went downstairs.

Meanwhile Monte Cristo had also returned to town with Emmanuel and Maximilian. Their return was cheerful. Emmanuel did not conceal his joy at the peaceful termination of the affair, and was loud in his expressions of delight. Morrel, in a corner of the carriage, allowed his brother-in-law’s gayety to expend itself in words, while he felt equal inward joy, which, however, betrayed itself only in his countenance.

At the Barrière du Trône they met Bertuccio, who was waiting there, motionless as a sentinel at his post. Monte Cristo put his head out of the window, exchanged a few words with him in a low tone, and the steward disappeared.

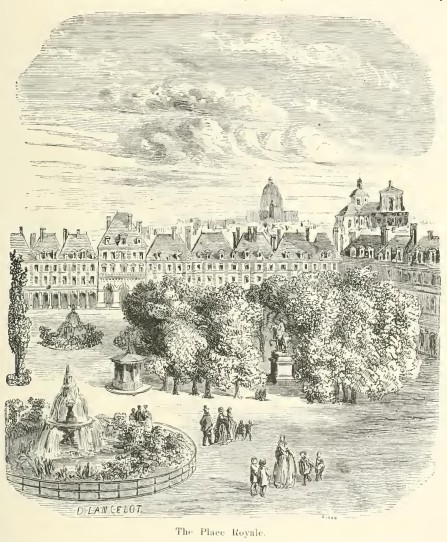

“Count,” said Emmanuel, when they were at the end of the Place Royale, “put me down at my door, that my wife may not have a single moment of needless anxiety on my account or yours.”

“If it were not ridiculous to make a display of our triumph, said Morrel, I would invite the count to our house; besides that, he doubtless has some trembling heart to comfort. So we will take leave of our friend, and let him hasten home.”

“Stop a moment,” said Monte Cristo; “do not let me lose both my companions. Return, Emmanuel, to your charming wife, and present my best compliments to her; and do you, Morrel, accompany me to the Champs-Élysées.”

“Willingly,” said Maximilian; “particularly as I have business in that quarter.”

“Shall we wait breakfast for you?” asked Emmanuel.

“No,” replied the young man. The door was closed, and the carriage proceeded. “See what good fortune I brought you!” said Morrel, when he was alone with the count. “Have you not thought so?”

“Yes,” said Monte Cristo; “for that reason I wished to keep you near me.”

“It is miraculous!” continued Morrel, answering his own thoughts.

“What?” said Monte Cristo.

“What has just happened.”

“Yes,” said the Count, “you are right—it is miraculous.”

“For Albert is brave,” resumed Morrel.

“Very brave,” said Monte Cristo; “I have seen him sleep with a sword suspended over his head.”

“And I know he has fought two duels,” said Morrel. “How can you reconcile that with his conduct this morning?”

“All owing to your influence,” replied Monte Cristo, smiling.

“It is well for Albert he is not in the army,” said Morrel.

“Why?”

“An apology on the ground!” said the young captain, shaking his head.

“Come,” said the count mildly, “do not entertain the prejudices of ordinary men, Morrel! Acknowledge, that if Albert is brave, he cannot be a coward; he must then have had some reason for acting as he did this morning, and confess that his conduct is more heroic than otherwise.”

“Doubtless, doubtless,” said Morrel; “but I shall say, like the Spaniard, ‘He has not been so brave today as he was yesterday.’”

“You will breakfast with me, will you not, Morrel?” said the count, to turn the conversation.

“No; I must leave you at ten o’clock.”

“Your engagement was for breakfast, then?” said the count.

Morrel smiled, and shook his head.

“Still you must breakfast somewhere.”

“But if I am not hungry?” said the young man.

“Oh,” said the count, “I only know two things which destroy the appetite,—grief—and as I am happy to see you very cheerful, it is not that—and love. Now after what you told me this morning of your heart, I may believe——”

“Well, count,” replied Morrel gayly, “I will not dispute it.”

“But you will not make me your confidant, Maximilian?” said the count, in a tone which showed how gladly he would have been admitted to the secret.

“I showed you this morning that I had a heart, did I not, count?” Monte Cristo only answered by extending his hand to the young man. “Well,” continued the latter, “since that heart is no longer with you in the Bois de Vincennes, it is elsewhere, and I must go and find it.”

“Go,” said the count deliberately; “go, dear friend, but promise me if you meet with any obstacle to remember that I have some power in this world, that I am happy to use that power in the behalf of those I love, and that I love you, Morrel.”

“I will remember it,” said the young man, “as selfish children recollect their parents when they want their aid. When I need your assistance, and the moment arrives, I will come to you, count.”

“Well, I rely upon your promise. Good-bye, then.”

“Good-bye, till we meet again.”

They had arrived in the Champs-Élysées. Monte Cristo opened the carriage-door, Morrel sprang out on the pavement, Bertuccio was waiting on the steps. Morrel disappeared down the Avenue de Marigny, and Monte Cristo hastened to join Bertuccio.

“Well?” asked he.

“She is going to leave her house,” said the steward.

“And her son?”

“Florentin, his valet, thinks he is going to do the same.”

“Come this way.” Monte Cristo took Bertuccio into his study, wrote the letter we have seen, and gave it to the steward. “Go,” said he quickly. “But first, let Haydée be informed that I have returned.”

“Here I am,” said the young girl, who at the sound of the carriage had run downstairs and whose face was radiant with joy at seeing the count return safely. Bertuccio left. Every transport of a daughter finding a father, all the delight of a mistress seeing an adored lover, were felt by Haydée during the first moments of this meeting, which she had so eagerly expected. Doubtless, although less evident, Monte Cristo’s joy was not less intense. Joy to hearts which have suffered long is like the dew on the ground after a long drought; both the heart and the ground absorb that beneficent moisture falling on them, and nothing is outwardly apparent.

Monte Cristo was beginning to think, what he had not for a long time dared to believe, that there were two Mercédès in the world, and he might yet be happy. His eye, elate with happiness, was reading eagerly the tearful gaze of Haydée, when suddenly the door opened. The count knit his brow.

“M. de Morcerf!” said Baptistin, as if that name sufficed for his excuse. In fact, the count’s face brightened.

“Which,” asked he, “the viscount or the count?”

“The count.”

“Oh,” exclaimed Haydée, “is it not yet over?”

“I know not if it is finished, my beloved child,” said Monte Cristo, taking the young girl’s hands; “but I do know you have nothing more to fear.”

“But it is the wretched——”

“That man cannot injure me, Haydée,” said Monte Cristo; “it was his son alone that there was cause to fear.”

“And what I have suffered,” said the young girl, “you shall never know, my lord.”

Monte Cristo smiled. “By my father’s tomb,” said he, extending his hand over the head of the young girl, “I swear to you, Haydée, that if any misfortune happens, it will not be to me.”

“I believe you, my lord, as implicitly as if God had spoken to me,” said the young girl, presenting her forehead to him. Monte Cristo pressed on that pure beautiful forehead a kiss which made two hearts throb at once, the one violently, the other secretly.

“Oh,” murmured the count, “shall I then be permitted to love again? Ask M. de Morcerf into the drawing-room,” said he to Baptistin, while he led the beautiful Greek girl to a private staircase.

We must explain this visit, which although expected by Monte Cristo, is unexpected to our readers. While Mercédès, as we have said, was making a similar inventory of her property to Albert’s, while she was arranging her jewels, shutting her drawers, collecting her keys, to leave everything in perfect order, she did not perceive a pale and sinister face at a glass door which threw light into the passage, from which everything could be both seen and heard. He who was thus looking, without being heard or seen, probably heard and saw all that passed in Madame de Morcerf’s apartments. From that glass door the pale-faced man went to the count’s bedroom and raised with a constricted hand the curtain of a window overlooking the courtyard. He remained there ten minutes, motionless and dumb, listening to the beating of his own heart. For him those ten minutes were very long. It was then Albert, returning from his meeting with the count, perceived his father watching for his arrival behind a curtain, and turned aside. The count’s eye expanded; he knew Albert had insulted the count dreadfully, and that in every country in the world such an insult would lead to a deadly duel. Albert returned safely—then the count was revenged.

An indescribable ray of joy illumined that wretched countenance like the last ray of the sun before it disappears behind the clouds which bear the aspect, not of a downy couch, but of a tomb. But as we have said, he waited in vain for his son to come to his apartment with the account of his triumph. He easily understood why his son did not come to see him before he went to avenge his father’s honor; but when that was done, why did not his son come and throw himself into his arms?

It was then, when the count could not see Albert, that he sent for his servant, who he knew was authorized not to conceal anything from him. Ten minutes afterwards, General Morcerf was seen on the steps in a black coat with a military collar, black pantaloons, and black gloves. He had apparently given previous orders, for as he reached the bottom step his carriage came from the coach-house ready for him. The valet threw into the carriage his military cloak, in which two swords were wrapped, and, shutting the door, he took his seat by the side of the coachman. The coachman stooped down for his orders.

“To the Champs-Élysées,” said the general; “the Count of Monte Cristo’s. Hurry!”

The horses bounded beneath the whip; and in five minutes they stopped before the count’s door. M. de Morcerf opened the door himself, and as the carriage rolled away he passed up the walk, rang, and entered the open door with his servant.

A moment afterwards, Baptistin announced the Count of Morcerf to Monte Cristo, and the latter, leading Haydée aside, ordered that Morcerf be asked into the drawing-room. The general was pacing the room the third time when, in turning, he perceived Monte Cristo at the door.

“Ah, it is M. de Morcerf,” said Monte Cristo quietly; “I thought I had not heard aright.”

“Yes, it is I,” said the count, whom a frightful contraction of the lips prevented from articulating freely.

“May I know the cause which procures me the pleasure of seeing M. de Morcerf so early?”

“Had you not a meeting with my son this morning?” asked the general.

“I had,” replied the count.

“And I know my son had good reasons to wish to fight with you, and to endeavor to kill you.”

“Yes, sir, he had very good ones; but you see that in spite of them he has not killed me, and did not even fight.”

“Yet he considered you the cause of his father’s dishonor, the cause of the fearful ruin which has fallen on my house.”

“It is true, sir,” said Monte Cristo with his dreadful calmness; “a secondary cause, but not the principal.”

“Doubtless you made, then, some apology or explanation?”

“I explained nothing, and it is he who apologized to me.”

“But to what do you attribute this conduct?”

“To the conviction, probably, that there was one more guilty than I.”

“And who was that?”

“His father.”

“That may be,” said the count, turning pale; “but you know the guilty do not like to find themselves convicted.”

“I know it, and I expected this result.”

“You expected my son would be a coward?” cried the count.

“M. Albert de Morcerf is no coward!” said Monte Cristo.

“A man who holds a sword in his hand, and sees a mortal enemy within reach of that sword, and does not fight, is a coward! Why is he not here that I may tell him so?”

“Sir,” replied Monte Cristo coldly, “I did not expect that you had come here to relate to me your little family affairs. Go and tell M. Albert that, and he may know what to answer you.”

“Oh, no, no,” said the general, smiling faintly, “I did not come for that purpose; you are right. I came to tell you that I also look upon you as my enemy. I came to tell you that I hate you instinctively; that it seems as if I had always known you, and always hated you; and, in short, since the young people of the present day will not fight, it remains for us to do so. Do you think so, sir?”

“Certainly. And when I told you I had foreseen the result, it is the honor of your visit I alluded to.”

“So much the better. Are you prepared?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You know that we shall fight till one of us is dead,” said the general, whose teeth were clenched with rage.