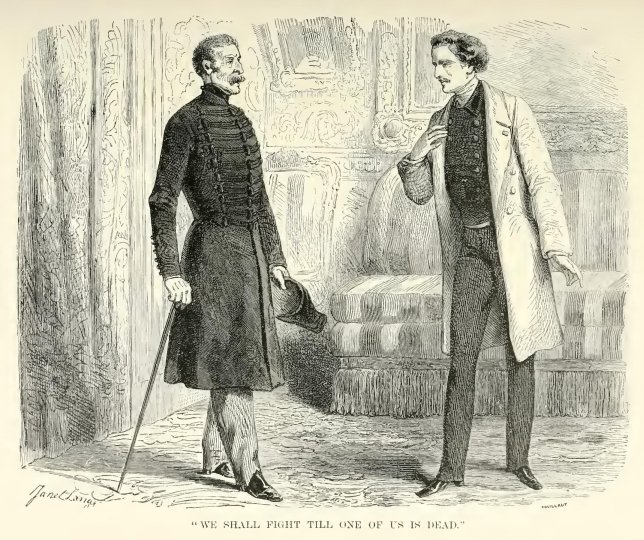

“Until one of us dies,” repeated Monte Cristo, moving his head slightly up and down.

“Let us start, then; we need no witnesses.”

“Very true,” said Monte Cristo; “it is unnecessary, we know each other so well!”

“On the contrary,” said the count, “we know so little of each other.”

“Indeed?” said Monte Cristo, with the same indomitable coolness; “let us see. Are you not the soldier Fernand who deserted on the eve of the battle of Waterloo? Are you not the Lieutenant Fernand who served as guide and spy to the French army in Spain? Are you not the Captain Fernand who betrayed, sold, and murdered his benefactor, Ali? And have not all these Fernands, united, made Lieutenant-General, the Count of Morcerf, peer of France?”

“Oh,” cried the general, as if branded with a hot iron, “wretch,—to reproach me with my shame when about, perhaps, to kill me! No, I did not say I was a stranger to you. I know well, demon, that you have penetrated into the darkness of the past, and that you have read, by the light of what torch I know not, every page of my life; but perhaps I may be more honorable in my shame than you under your pompous coverings. No—no, I am aware you know me; but I know you only as an adventurer sewn up in gold and jewellery. You call yourself, in Paris, the Count of Monte Cristo; in Italy, Sinbad the Sailor; in Malta, I forget what. But it is your real name I want to know, in the midst of your hundred names, that I may pronounce it when we meet to fight, at the moment when I plunge my sword through your heart.”

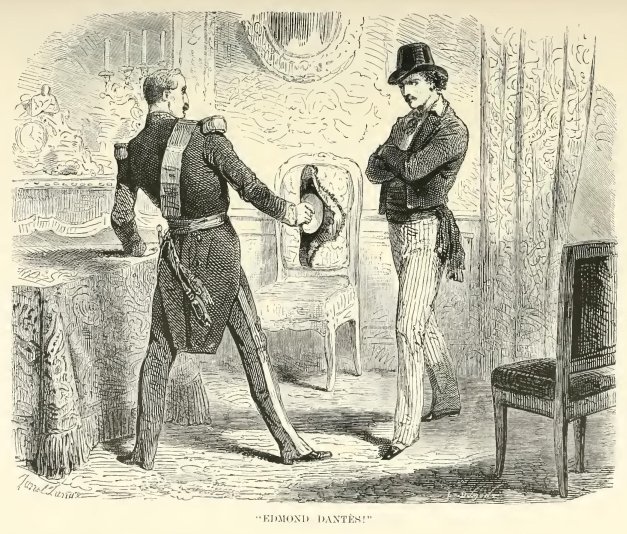

The Count of Monte Cristo turned dreadfully pale; his eye seemed to burn with a devouring fire. He leaped towards a dressing-room near his bedroom, and in less than a moment, tearing off his cravat, his coat and waistcoat, he put on a sailor’s jacket and hat, from beneath which rolled his long black hair. He returned thus, formidable and implacable, advancing with his arms crossed on his breast, towards the general, who could not understand why he had disappeared, but who on seeing him again, and feeling his teeth chatter and his legs sink under him, drew back, and only stopped when he found a table to support his clenched hand.

“Fernand,” cried he, “of my hundred names I need only tell you one, to overwhelm you! But you guess it now, do you not?—or, rather, you remember it? For, notwithstanding all my sorrows and my tortures, I show you today a face which the happiness of revenge makes young again—a face you must often have seen in your dreams since your marriage with Mercédès, my betrothed!”

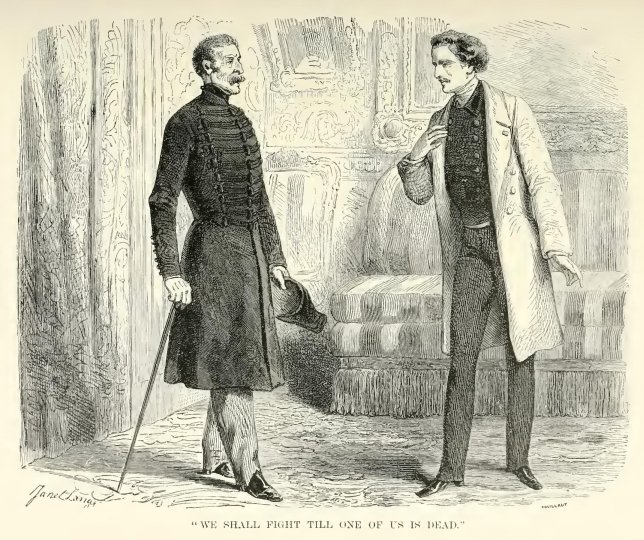

The general, with his head thrown back, hands extended, gaze fixed, looked silently at this dreadful apparition; then seeking the wall to support him, he glided along close to it until he reached the door, through which he went out backwards, uttering this single mournful, lamentable, distressing cry:

“Edmond Dantès!”

Then, with sighs which were unlike any human sound, he dragged himself to the door, reeled across the courtyard, and falling into the arms of his valet, he said in a voice scarcely intelligible,—“Home, home.”

The fresh air and the shame he felt at having exposed himself before his servants, partly recalled his senses, but the ride was short, and as he drew near his house all his wretchedness revived. He stopped at a short distance from the house and alighted. The door was wide open, a hackney-coach was standing in the middle of the yard—a strange sight before so noble a mansion; the count looked at it with terror, but without daring to inquire its meaning, he rushed towards his apartment.

Two persons were coming down the stairs; he had only time to creep into an alcove to avoid them. It was Mercédès leaning on her son’s arm and leaving the house. They passed close by the unhappy being, who, concealed behind the damask curtain, almost felt Mercédès dress brush past him, and his son’s warm breath, pronouncing these words:

“Courage, mother! Come, this is no longer our home!”

The words died away, the steps were lost in the distance. The general drew himself up, clinging to the curtain; he uttered the most dreadful sob which ever escaped from the bosom of a father abandoned at the same time by his wife and son. He soon heard the clatter of the iron step of the hackney-coach, then the coachman’s voice, and then the rolling of the heavy vehicle shook the windows. He darted to his bedroom to see once more all he had loved in the world; but the hackney-coach drove on and the head of neither Mercédès nor her son appeared at the window to take a last look at the house or the deserted father and husband.

And at the very moment when the wheels of that coach crossed the gateway a report was heard, and a thick smoke escaped through one of the panes of the window, which was broken by the explosion.

We may easily conceive where Morrel’s appointment was. On leaving Monte Cristo he walked slowly towards Villefort’s; we say slowly, for Morrel had more than half an hour to spare to go five hundred steps, but he had hastened to take leave of Monte Cristo because he wished to be alone with his thoughts. He knew his time well—the hour when Valentine was giving Noirtier his breakfast, and was sure not to be disturbed in the performance of this pious duty. Noirtier and Valentine had given him leave to go twice a week, and he was now availing himself of that permission.

He arrived; Valentine was expecting him. Uneasy and almost crazed, she seized his hand and led him to her grandfather. This uneasiness, amounting almost to frenzy, arose from the report Morcerf’s adventure had made in the world, for the affair at the Opera was generally known. No one at Villefort’s doubted that a duel would ensue from it. Valentine, with her woman’s instinct, guessed that Morrel would be Monte Cristo’s second, and from the young man’s well-known courage and his great affection for the count, she feared that he would not content himself with the passive part assigned to him. We may easily understand how eagerly the particulars were asked for, given, and received; and Morrel could read an indescribable joy in the eyes of his beloved, when she knew that the termination of this affair was as happy as it was unexpected.

“Now,” said Valentine, motioning to Morrel to sit down near her grandfather, while she took her seat on his footstool,—“now let us talk about our own affairs. You know, Maximilian, grandpapa once thought of leaving this house, and taking an apartment away from M. de Villefort’s.”

“Yes,” said Maximilian, “I recollect the project, of which I highly approved.”

“Well,” said Valentine, “you may approve again, for grandpapa is again thinking of it.”

“Bravo,” said Maximilian.

“And do you know,” said Valentine, “what reason grandpapa gives for leaving this house.” Noirtier looked at Valentine to impose silence, but she did not notice him; her looks, her eyes, her smile, were all for Morrel.

“Oh, whatever may be M. Noirtier’s reason,” answered Morrel, “I can readily believe it to be a good one.”

“An excellent one,” said Valentine. “He pretends the air of the Faubourg Saint-Honoré is not good for me.”

“Indeed?” said Morrel; “in that M. Noirtier may be right; you have not seemed to be well for the last fortnight.”

“Not very,” said Valentine. “And grandpapa has become my physician, and I have the greatest confidence in him, because he knows everything.”

“Do you then really suffer?” asked Morrel quickly.

“Oh, it must not be called suffering; I feel a general uneasiness, that is all. I have lost my appetite, and my stomach feels as if it were struggling to get accustomed to something.” Noirtier did not lose a word of what Valentine said.

“And what treatment do you adopt for this singular complaint?”

“A very simple one,” said Valentine. “I swallow every morning a spoonful of the mixture prepared for my grandfather. When I say one spoonful, I began by one—now I take four. Grandpapa says it is a panacea.” Valentine smiled, but it was evident that she suffered.

Maximilian, in his devotedness, gazed silently at her. She was very beautiful, but her usual pallor had increased; her eyes were more brilliant than ever, and her hands, which were generally white like mother-of-pearl, now more resembled wax, to which time was adding a yellowish hue.

From Valentine the young man looked towards Noirtier. The latter watched with strange and deep interest the young girl, absorbed by her affection, and he also, like Morrel, followed those traces of inward suffering which was so little perceptible to a common observer that they escaped the notice of everyone but the grandfather and the lover.

“But,” said Morrel, “I thought this mixture, of which you now take four spoonfuls, was prepared for M. Noirtier?”

“I know it is very bitter,” said Valentine; “so bitter, that all I drink afterwards appears to have the same taste.” Noirtier looked inquiringly at his granddaughter. “Yes, grandpapa,” said Valentine; “it is so. Just now, before I came down to you, I drank a glass of sugared water; I left half, because it seemed so bitter.” Noirtier turned pale, and made a sign that he wished to speak.

Valentine rose to fetch the dictionary. Noirtier watched her with evident anguish. In fact, the blood was rushing to the young girl’s head already, her cheeks were becoming red.

“Oh,” cried she, without losing any of her cheerfulness, “this is singular! I can’t see! Did the sun shine in my eyes?” And she leaned against the window.

“The sun is not shining,” said Morrel, more alarmed by Noirtier’s expression than by Valentine’s indisposition. He ran towards her. The young girl smiled.

“Cheer up,” said she to Noirtier. “Do not be alarmed, Maximilian; it is nothing, and has already passed away. But listen! Do I not hear a carriage in the courtyard?” She opened Noirtier’s door, ran to a window in the passage, and returned hastily. “Yes,” said she, “it is Madame Danglars and her daughter, who have come to call on us. Good-bye;—I must run away, for they would send here for me, or, rather, farewell till I see you again. Stay with grandpapa, Maximilian; I promise you not to persuade them to stay.”

Morrel watched her as she left the room; he heard her ascend the little staircase which led both to Madame de Villefort’s apartments and to hers. As soon as she was gone, Noirtier made a sign to Morrel to take the dictionary. Morrel obeyed; guided by Valentine, he had learned how to understand the old man quickly. Accustomed, however, as he was to the work, he had to repeat most of the letters of the alphabet and to find every word in the dictionary, so that it was ten minutes before the thought of the old man was translated by these words,

“Fetch the glass of water and the decanter from Valentine’s room.”

Morrel rang immediately for the servant who had taken Barrois’s situation, and in Noirtier’s name gave that order. The servant soon returned. The decanter and the glass were completely empty. Noirtier made a sign that he wished to speak.

“Why are the glass and decanter empty?” asked he; “Valentine said she only drank half the glassful.”

The translation of this new question occupied another five minutes.

“I do not know,” said the servant, “but the housemaid is in Mademoiselle Valentine’s room: perhaps she has emptied them.”

“Ask her,” said Morrel, translating Noirtier’s thought this time by his look. The servant went out, but returned almost immediately. “Mademoiselle Valentine passed through the room to go to Madame de Villefort’s,” said he; “and in passing, as she was thirsty, she drank what remained in the glass; as for the decanter, Master Edward had emptied that to make a pond for his ducks.”

Noirtier raised his eyes to heaven, as a gambler does who stakes his all on one stroke. From that moment the old man’s eyes were fixed on the door, and did not quit it.

It was indeed Madame Danglars and her daughter whom Valentine had seen; they had been ushered into Madame de Villefort’s room, who had said she would receive them there. That is why Valentine passed through her room, which was on a level with Valentine’s, and only separated from it by Edward’s. The two ladies entered the drawing-room with that sort of official stiffness which preludes a formal communication. Among worldly people manner is contagious. Madame de Villefort received them with equal solemnity. Valentine entered at this moment, and the formalities were resumed.

“My dear friend,” said the baroness, while the two young people were shaking hands, “I and Eugénie are come to be the first to announce to you the approaching marriage of my daughter with Prince Cavalcanti.” Danglars kept up the title of prince. The popular banker found that it answered better than count.

“Allow me to present you my sincere congratulations,” replied Madame de Villefort. “Prince Cavalcanti appears to be a young man of rare qualities.”

“Listen,” said the baroness, smiling; “speaking to you as a friend I can say that the prince does not yet appear all he will be. He has about him a little of that foreign manner by which French persons recognize, at first sight, the Italian or German nobleman. Besides, he gives evidence of great kindness of disposition, much keenness of wit, and as to suitability, M. Danglars assures me that his fortune is majestic—that is his word.”

“And then,” said Eugénie, while turning over the leaves of Madame de Villefort’s album, “add that you have taken a great fancy to the young man.”

“And,” said Madame de Villefort, “I need not ask you if you share that fancy.”

“I?” replied Eugénie with her usual candor. “Oh, not the least in the world, madame! My wish was not to confine myself to domestic cares, or the caprices of any man, but to be an artist, and consequently free in heart, in person, and in thought.”

Eugénie pronounced these words with so firm a tone that the color mounted to Valentine’s cheeks. The timid girl could not understand that vigorous nature which appeared to have none of the timidities of woman.

“At any rate,” said she, “since I am to be married whether I will or not, I ought to be thankful to Providence for having released me from my engagement with M. Albert de Morcerf, or I should this day have been the wife of a dishonored man.”

“It is true,” said the baroness, with that strange simplicity sometimes met with among fashionable ladies, and of which plebeian intercourse can never entirely deprive them,—“it is very true that had not the Morcerfs hesitated, my daughter would have married Monsieur Albert. The general depended much on it; he even came to force M. Danglars. We have had a narrow escape.”

“But,” said Valentine, timidly, “does all the father’s shame revert upon the son? Monsieur Albert appears to me quite innocent of the treason charged against the general.”

“Excuse me,” said the implacable young girl, “Monsieur Albert claims and well deserves his share. It appears that after having challenged M. de Monte Cristo at the Opera yesterday, he apologized on the ground today.”

“Impossible,” said Madame de Villefort.

“Ah, my dear friend,” said Madame Danglars, with the same simplicity we before noticed, “it is a fact. I heard it from M. Debray, who was present at the explanation.”

Valentine also knew the truth, but she did not answer. A single word had reminded her that Morrel was expecting her in M. Noirtier’s room. Deeply engaged with a sort of inward contemplation, Valentine had ceased for a moment to join in the conversation. She would, indeed, have found it impossible to repeat what had been said the last few minutes, when suddenly Madame Danglars’ hand, pressed on her arm, aroused her from her lethargy.

“What is it?” said she, starting at Madame Danglars’ touch as she would have done from an electric shock.

“It is, my dear Valentine,” said the baroness, “that you are, doubtless, suffering.”

“I?” said the young girl, passing her hand across her burning forehead.

“Yes, look at yourself in that glass; you have turned pale and then red successively, three or four times in one minute.”

“Indeed,” cried Eugénie, “you are very pale!”

“Oh, do not be alarmed; I have been so for many days.” Artless as she was, the young girl knew that this was an opportunity to leave, and besides, Madame de Villefort came to her assistance.

“Retire, Valentine,” said she; “you are really suffering, and these ladies will excuse you; drink a glass of pure water, it will restore you.”

Valentine kissed Eugénie, bowed to Madame Danglars, who had already risen to take her leave, and went out.

“That poor child,” said Madame de Villefort when Valentine was gone, “she makes me very uneasy, and I should not be astonished if she had some serious illness.”

Meanwhile, Valentine, in a sort of excitement which she could not quite understand, had crossed Edward’s room without noticing some trick of the child, and through her own had reached the little staircase.

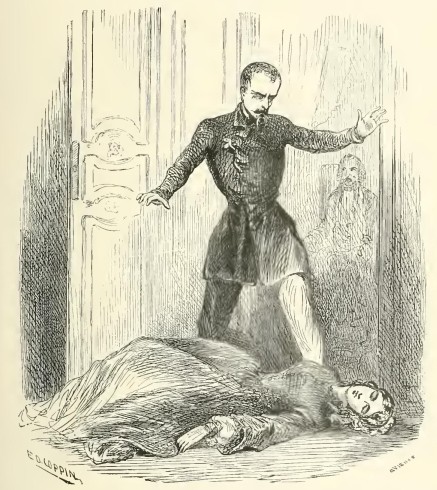

She was within three steps of the bottom; she already heard Morrel’s voice, when suddenly a cloud passed over her eyes, her stiffened foot missed the step, her hands had no power to hold the baluster, and falling against the wall she lost her balance wholly and toppled to the floor. Morrel bounded to the door, opened it, and found Valentine stretched out at the bottom of the stairs. Quick as a flash, he raised her in his arms and placed her in a chair. Valentine opened her eyes.

“Oh, what a clumsy thing I am,” said she with feverish volubility; “I don’t know my way. I forgot there were three more steps before the landing.”

“You have hurt yourself, perhaps,” said Morrel. “What can I do for you, Valentine?”

Valentine looked around her; she saw the deepest terror depicted in Noirtier’s eyes.

“Don’t worry, dear grandpapa,” said she, endeavoring to smile; “it is nothing—it is nothing; I was giddy, that is all.”

“Another attack of giddiness,” said Morrel, clasping his hands. “Oh, attend to it, Valentine, I entreat you.”

“But no,” said Valentine,—“no, I tell you it is all past, and it was nothing. Now, let me tell you some news; Eugénie is to be married in a week, and in three days there is to be a grand feast, a betrothal festival. We are all invited, my father, Madame de Villefort, and I—at least, I understood it so.”

“When will it be our turn to think of these things? Oh, Valentine, you who have so much influence over your grandpapa, try to make him answer—Soon.”

“And do you,” said Valentine, “depend on me to stimulate the tardiness and arouse the memory of grandpapa?”

“Yes,” cried Morrel, “make haste. So long as you are not mine, Valentine, I shall always think I may lose you.”

“Oh,” replied Valentine with a convulsive movement, “oh, indeed, Maximilian, you are too timid for an officer, for a soldier who, they say, never knows fear. Ha, ha, ha!”

She burst into a forced and melancholy laugh, her arms stiffened and twisted, her head fell back on her chair, and she remained motionless. The cry of terror which was stopped on Noirtier’s lips, seemed to start from his eyes. Morrel understood it; he knew he must call assistance. The young man rang the bell violently; the housemaid who had been in Mademoiselle Valentine’s room, and the servant who had replaced Barrois, ran in at the same moment. Valentine was so pale, so cold, so inanimate that without listening to what was said to them they were seized with the fear which pervaded that house, and they flew into the passage crying for help. Madame Danglars and Eugénie were going out at that moment; they heard the cause of the disturbance.

“I told you so!” exclaimed Madame de Villefort. “Poor child!”

At the same moment M. de Villefort’s voice was heard calling from his study, “What is the matter?”

Morrel looked at Noirtier who had recovered his self-command, and with a glance indicated the closet where once before under somewhat similar circumstances, he had taken refuge. He had only time to get his hat and throw himself breathless into the closet when the procureur’s footstep was heard in the passage.

Villefort sprang into the room, ran to Valentine, and took her in his arms.

“A physician, a physician,—M. d’Avrigny!” cried Villefort; “or rather I will go for him myself.”

He flew from the apartment, and Morrel at the same moment darted out at the other door. He had been struck to the heart by a frightful recollection—the conversation he had heard between the doctor and Villefort the night of Madame de Saint-Méran’s death, recurred to him; these symptoms, to a less alarming extent, were the same which had preceded the death of Barrois. At the same time Monte Cristo’s voice seemed to resound in his ear with the words he had heard only two hours before, “Whatever you want, Morrel, come to me; I have great power.”

More rapidly than thought, he darted down the Rue Matignon, and thence to the Avenue des Champs-Élysées.

Meanwhile M. de Villefort arrived in a hired cabriolet at M. d’Avrigny’s door. He rang so violently that the porter was alarmed. Villefort ran upstairs without saying a word. The porter knew him, and let him pass, only calling to him:

“In his study, Monsieur Procureur—in his study!” Villefort pushed, or rather forced, the door open.

“Ah,” said the doctor, “is it you?”

“Yes,” said Villefort, closing the door after him, “it is I, who am come in my turn to ask you if we are quite alone. Doctor, my house is accursed!”

“What?” said the latter with apparent coolness, but with deep emotion, “have you another invalid?”

“Yes, doctor,” cried Villefort, clutching his hair, “yes!”

D’Avrigny’s look implied, “I told you it would be so.” Then he slowly uttered these words, “Who is now dying in your house? What new victim is going to accuse you of weakness before God?”

A mournful sob burst from Villefort’s heart; he approached the doctor, and seizing his arm,—“Valentine,” said he, “it is Valentine’s turn!”

“Your daughter!” cried d’Avrigny with grief and surprise.

“You see you were deceived,” murmured the magistrate; “come and see her, and on her bed of agony entreat her pardon for having suspected her.”

“Each time you have applied to me,” said the doctor, “it has been too late; still I will go. But let us make haste, sir; with the enemies you have to do with there is no time to be lost.”

“Oh, this time, doctor, you shall not have to reproach me with weakness. This time I will know the assassin, and will pursue him.”

“Let us try first to save the victim before we think of revenging her,” said d’Avrigny. “Come.”

The same cabriolet which had brought Villefort took them back at full speed, and at this moment Morrel rapped at Monte Cristo’s door.

The count was in his study and was reading with an angry look something which Bertuccio had brought in haste. Hearing the name of Morrel, who had left him only two hours before, the count raised his head, arose, and sprang to meet him.

“What is the matter, Maximilian?” asked he; “you are pale, and the perspiration rolls from your forehead.” Morrel fell into a chair.

“Yes,” said he, “I came quickly; I wanted to speak to you.”

“Are all your family well?” asked the count, with an affectionate benevolence, whose sincerity no one could for a moment doubt.

“Thank you, count—thank you,” said the young man, evidently embarrassed how to begin the conversation; “yes, everyone in my family is well.”

“So much the better; yet you have something to tell me?” replied the count with increased anxiety.

“Yes,” said Morrel, “it is true; I have but now left a house where death has just entered, to run to you.”

“Are you then come from M. de Morcerf’s?” asked Monte Cristo.

“No,” said Morrel; “is someone dead in his house?”

“The general has just blown his brains out,” replied Monte Cristo with great coolness.

“Oh, what a dreadful event!” cried Maximilian.

“Not for the countess, or for Albert,” said Monte Cristo; “a dead father or husband is better than a dishonored one,—blood washes out shame.”

“Poor countess,” said Maximilian, “I pity her very much; she is so noble a woman!”

“Pity Albert also, Maximilian; for believe me he is the worthy son of the countess. But let us return to yourself. You have hastened to me—can I have the happiness of being useful to you?”

“Yes, I need your help: that is I thought like a madman that you could lend me your assistance in a case where God alone can succor me.”

“Tell me what it is,” replied Monte Cristo.

“Oh,” said Morrel, “I know not, indeed, if I may reveal this secret to mortal ears, but fatality impels me, necessity constrains me, count——” Morrel hesitated.

“Do you think I love you?” said Monte Cristo, taking the young man’s hand affectionately in his.

“Oh, you encourage me, and something tells me there,” placing his hand on his heart, “that I ought to have no secret from you.”

“You are right, Morrel; God is speaking to your heart, and your heart speaks to you. Tell me what it says.”

“Count, will you allow me to send Baptistin to inquire after someone you know?”

“I am at your service, and still more my servants.”

“Oh, I cannot live if she is not better.”

“Shall I ring for Baptistin?”

“No, I will go and speak to him myself.” Morrel went out, called Baptistin, and whispered a few words to him. The valet ran directly.

“Well, have you sent?” asked Monte Cristo, seeing Morrel return.

“Yes, and now I shall be more calm.”

“You know I am waiting,” said Monte Cristo, smiling.

“Yes, and I will tell you. One evening I was in a garden; a clump of trees concealed me; no one suspected I was there. Two persons passed near me—allow me to conceal their names for the present; they were speaking in an undertone, and yet I was so interested in what they said that I did not lose a single word.”

“This is a gloomy introduction, if I may judge from your pallor and shuddering, Morrel.”

“Oh, yes, very gloomy, my friend. Someone had just died in the house to which that garden belonged. One of the persons whose conversation I overheard was the master of the house; the other, the physician. The former was confiding to the latter his grief and fear, for it was the second time within a month that death had suddenly and unexpectedly entered that house which was apparently destined to destruction by some exterminating angel, as an object of God’s anger.”

“Ah, indeed?” said Monte Cristo, looking earnestly at the young man, and by an imperceptible movement turning his chair, so that he remained in the shade while the light fell full on Maximilian’s face.

“Yes,” continued Morrel, “death had entered that house twice within one month.”

“And what did the doctor answer?” asked Monte Cristo.

“He replied—he replied, that the death was not a natural one, and must be attributed”—

“To what?”

“To poison.”

“Indeed!” said Monte Cristo with a slight cough which in moments of extreme emotion helped him to disguise a blush, or his pallor, or the intense interest with which he listened; “indeed, Maximilian, did you hear that?”

“Yes, my dear count, I heard it; and the doctor added that if another death occurred in a similar way he must appeal to justice.”

Monte Cristo listened, or appeared to do so, with the greatest calmness.

“Well,” said Maximilian, “death came a third time, and neither the master of the house nor the doctor said a word. Death is now, perhaps, striking a fourth blow. Count, what am I bound to do, being in possession of this secret?”

“My dear friend,” said Monte Cristo, “you appear to be relating an adventure which we all know by heart. I know the house where you heard it, or one very similar to it; a house with a garden, a master, a physician, and where there have been three unexpected and sudden deaths. Well, I have not intercepted your confidence, and yet I know all that as well as you, and I have no conscientious scruples. No, it does not concern me. You say an exterminating angel appears to have devoted that house to God’s anger—well, who says your supposition is not reality? Do not notice things which those whose interest it is to see them pass over. If it is God’s justice, instead of his anger, which is walking through that house, Maximilian, turn away your face and let his justice accomplish its purpose.”

Morrel shuddered. There was something mournful, solemn, and terrible in the count’s manner.

“Besides,” continued he, in so changed a tone that no one would have supposed it was the same person speaking—“besides, who says that it will begin again?”

“It has returned, count,” exclaimed Morrel; “that is why I hastened to you.”

“Well, what do you wish me to do? Do you wish me, for instance, to give information to the procureur?” Monte Cristo uttered the last words with so much meaning that Morrel, starting up, cried out:

“You know of whom I speak, count, do you not?”

“Perfectly well, my good friend; and I will prove it to you by putting the dots to the i, or rather by naming the persons. You were walking one evening in M. de Villefort’s garden; from what you relate, I suppose it to have been the evening of Madame de Saint-Méran’s death. You heard M. de Villefort talking to M. d’Avrigny about the death of M. de Saint-Méran, and that no less surprising, of the countess. M. d’Avrigny said he believed they both proceeded from poison; and you, honest man, have ever since been asking your heart and sounding your conscience to know if you ought to expose or conceal this secret. We are no longer in the Middle Ages; there is no longer a Vehmgericht, or Free Tribunals; what do you want to ask these people? ‘Conscience, what hast thou to do with me?’ as Sterne said. My dear fellow, let them sleep on, if they are asleep; let them grow pale in their drowsiness, if they are disposed to do so, and pray do you remain in peace, who have no remorse to disturb you.”

Deep grief was depicted on Morrel’s features; he seized Monte Cristo’s hand. “But it is beginning again, I say!”

“Well,” said the Count, astonished at his perseverance, which he could not understand, and looking still more earnestly at Maximilian, “let it begin again,—it is like the house of the Atreidae;19 God has condemned them, and they must submit to their punishment. They will all disappear, like the fabrics children build with cards, and which fall, one by one, under the breath of their builder, even if there are two hundred of them. Three months since it was M. de Saint-Méran; Madame de Saint-Méran two months since; the other day it was Barrois; today, the old Noirtier, or young Valentine.”

“You knew it?” cried Morrel, in such a paroxysm of terror that Monte Cristo started,—he whom the falling heavens would have found unmoved; “you knew it, and said nothing?”

“And what is it to me?” replied Monte Cristo, shrugging his shoulders; “do I know those people? and must I lose the one to save the other? Faith, no, for between the culprit and the victim I have no choice.”

“But I,” cried Morrel, groaning with sorrow, “I love her!”

“You love?—whom?” cried Monte Cristo, starting to his feet, and seizing the two hands which Morrel was raising towards heaven.

“I love most fondly—I love madly—I love as a man who would give his life-blood to spare her a tear—I love Valentine de Villefort, who is being murdered at this moment! Do you understand me? I love her; and I ask God and you how I can save her?”

Monte Cristo uttered a cry which those only can conceive who have heard the roar of a wounded lion. “Unhappy man,” cried he, wringing his hands in his turn; “you love Valentine,—that daughter of an accursed race!”

Never had Morrel witnessed such an expression—never had so terrible an eye flashed before his face—never had the genius of terror he had so often seen, either on the battle-field or in the murderous nights of Algeria, shaken around him more dreadful fire. He drew back terrified.

As for Monte Cristo, after this ebullition he closed his eyes as if dazzled by internal light. In a moment he restrained himself so powerfully that the tempestuous heaving of his breast subsided, as turbulent and foaming waves yield to the sun’s genial influence when the cloud has passed. This silence, self-control, and struggle lasted about twenty seconds, then the count raised his pallid face.

“See,” said he, “my dear friend, how God punishes the most thoughtless and unfeeling men for their indifference, by presenting dreadful scenes to their view. I, who was looking on, an eager and curious spectator,—I, who was watching the working of this mournful tragedy,—I, who like a wicked angel was laughing at the evil men committed protected by secrecy (a secret is easily kept by the rich and powerful), I am in my turn bitten by the serpent whose tortuous course I was watching, and bitten to the heart!”

Morrel groaned.

“Come, come,” continued the count, “complaints are unavailing, be a man, be strong, be full of hope, for I am here and will watch over you.”

Morrel shook his head sorrowfully.

“I tell you to hope. Do you understand me?” cried Monte Cristo. “Remember that I never uttered a falsehood and am never deceived. It is twelve o’clock, Maximilian; thank heaven that you came at noon rather than in the evening, or tomorrow morning. Listen, Morrel—it is noon; if Valentine is not now dead, she will not die.”

“How so?” cried Morrel, “when I left her dying?”

Monte Cristo pressed his hands to his forehead. What was passing in that brain, so loaded with dreadful secrets? What does the angel of light or the angel of darkness say to that mind, at once implacable and generous? God only knows.

Monte Cristo raised his head once more, and this time he was calm as a child awaking from its sleep.

“Maximilian,” said he, “return home. I command you not to stir—attempt nothing, not to let your countenance betray a thought, and I will send you tidings. Go.”

“Oh, count, you overwhelm me with that coolness. Have you, then, power against death? Are you superhuman? Are you an angel?” And the young man, who had never shrunk from danger, shrank before Monte Cristo with indescribable terror. But Monte Cristo looked at him with so melancholy and sweet a smile, that Maximilian felt the tears filling his eyes.

“I can do much for you, my friend,” replied the count. “Go; I must be alone.”

Morrel, subdued by the extraordinary ascendancy Monte Cristo exercised over everything around him, did not endeavor to resist it. He pressed the count’s hand and left. He stopped one moment at the door for Baptistin, whom he saw in the Rue Matignon, and who was running.

Meanwhile, Villefort and d’Avrigny had made all possible haste, Valentine had not revived from her fainting fit on their arrival, and the doctor examined the invalid with all the care the circumstances demanded, and with an interest which the knowledge of the secret intensified twofold. Villefort, closely watching his countenance and his lips, awaited the result of the examination. Noirtier, paler than even the young girl, more eager than Villefort for the decision, was watching also intently and affectionately.

At last d’Avrigny slowly uttered these words: “She is still alive!”

“Still?” cried Villefort; “oh, doctor, what a dreadful word is that.”

“Yes,” said the physician, “I repeat it; she is still alive, and I am astonished at it.”

“But is she safe?” asked the father.

“Yes, since she lives.”

At that moment d’Avrigny’s glance met Noirtier’s eye. It glistened with such extraordinary joy, so rich and full of thought, that the physician was struck. He placed the young girl again on the chair,—her lips were scarcely discernible, they were so pale and white, as well as her whole face,—and remained motionless, looking at Noirtier, who appeared to anticipate and commend all he did.

“Sir,” said d’Avrigny to Villefort, “call Mademoiselle Valentine’s maid, if you please.”

Villefort went himself to find her; and d’Avrigny approached Noirtier.

“Have you something to tell me?” asked he. The old man winked his eyes expressively, which we may remember was his only way of expressing his approval.

“Privately?”

“Yes.”

“Well, I will remain with you.” At this moment Villefort returned, followed by the lady’s maid; and after her came Madame de Villefort.

“What is the matter, then, with this dear child? she has just left me, and she complained of being indisposed, but I did not think seriously of it.”

The young woman with tears in her eyes and every mark of affection of a true mother, approached Valentine and took her hand. D’Avrigny continued to look at Noirtier; he saw the eyes of the old man dilate and become round, his cheeks turn pale and tremble; the perspiration stood in drops upon his forehead.

“Ah,” said he, involuntarily following Noirtier’s eyes, which were fixed on Madame de Villefort, who repeated:

“This poor child would be better in bed. Come, Fanny, we will put her to bed.”

M. d’Avrigny, who saw that would be a means of his remaining alone with Noirtier, expressed his opinion that it was the best thing that could be done; but he forbade that anything should be given to her except what he ordered.

They carried Valentine away; she had revived, but could scarcely move or speak, so shaken was her frame by the attack. She had, however, just power to give one parting look to her grandfather, who in losing her seemed to be resigning his very soul. D’Avrigny followed the invalid, wrote a prescription, ordered Villefort to take a cabriolet, go in person to a chemist’s to get the prescribed medicine, bring it himself, and wait for him in his daughter’s room. Then, having renewed his injunction not to give Valentine anything, he went down again to Noirtier, shut the doors carefully, and after convincing himself that no one was listening:

“Do you,” said he, “know anything of this young lady’s illness?”

“Yes,” said the old man.

“We have no time to lose; I will question, and do you answer me.” Noirtier made a sign that he was ready to answer. “Did you anticipate the accident which has happened to your granddaughter?”

“Yes.” D’Avrigny reflected a moment; then approaching Noirtier:

“Pardon what I am going to say,” added he, “but no indication should be neglected in this terrible situation. Did you see poor Barrois die?” Noirtier raised his eyes to heaven.

“Do you know of what he died!” asked d’Avrigny, placing his hand on Noirtier’s shoulder.

“Yes,” replied the old man.

“Do you think he died a natural death?” A sort of smile was discernible on the motionless lips of Noirtier.

“Then you have thought that Barrois was poisoned?”

“Yes.”

“Do you think the poison he fell a victim to was intended for him?”

“No.”

“Do you think the same hand which unintentionally struck Barrois has now attacked Valentine?”

“Yes.”

“Then will she die too?” asked d’Avrigny, fixing his penetrating gaze on Noirtier. He watched the effect of this question on the old man.

“No,” replied he with an air of triumph which would have puzzled the most clever diviner.

“Then you hope?” said d’Avrigny, with surprise.

“Yes.”

“What do you hope?” The old man made him understand with his eyes that he could not answer.

“Ah, yes, it is true,” murmured d’Avrigny. Then, turning to Noirtier,—“Do you hope the assassin will be tried?”

“No.”

“Then you hope the poison will take no effect on Valentine?”

“Yes.”

“It is no news to you,” added d’Avrigny, “to tell you that an attempt has been made to poison her?” The old man made a sign that he entertained no doubt upon the subject. “Then how do you hope Valentine will escape?”

Noirtier kept his eyes steadfastly fixed on the same spot. D’Avrigny followed the direction and saw that they were fixed on a bottle containing the mixture which he took every morning. “Ah, indeed?” said d’Avrigny, struck with a sudden thought, “has it occurred to you”—Noirtier did not let him finish.

“Yes,” said he.

“To prepare her system to resist poison?”

“Yes.”

“By accustoming her by degrees——”

“Yes, yes, yes,” said Noirtier, delighted to be understood.

“Of course. I had told you that there was brucine in the mixture I give you.”

“Yes.”

“And by accustoming her to that poison, you have endeavored to neutralize the effect of a similar poison?” Noirtier’s joy continued. “And you have succeeded,” exclaimed d’Avrigny. “Without that precaution Valentine would have died before assistance could have been procured. The dose has been excessive, but she has only been shaken by it; and this time, at any rate, Valentine will not die.”

A superhuman joy expanded the old man’s eyes, which were raised towards heaven with an expression of infinite gratitude. At this moment Villefort returned.

“Here, doctor,” said he, “is what you sent me for.”

“Was this prepared in your presence?”

“Yes,” replied the procureur.

“Have you not let it go out of your hands?”

“No.”

D’Avrigny took the bottle, poured some drops of the mixture it contained in the hollow of his hand, and swallowed them.

“Well,” said he, “let us go to Valentine; I will give instructions to everyone, and you, M. de Villefort, will yourself see that no one deviates from them.”