“Yes,” replied the count; “a felon named Caderousse.” Danglars turned slightly pale; Andrea reached the anteroom beyond the little drawing-room.

“But go on signing,” said Monte Cristo; “I perceive that my story has caused a general emotion, and I beg to apologize to you, baroness, and to Mademoiselle Danglars.”

The baroness, who had signed, returned the pen to the notary.

“Prince Cavalcanti,” said the latter; “Prince Cavalcanti, where are you?”

“Andrea, Andrea,” repeated several young people, who were already on sufficiently intimate terms with him to call him by his Christian name.

“Call the prince; inform him that it is his turn to sign,” cried Danglars to one of the floorkeepers.

But at the same instant the crowd of guests rushed in alarm into the principal salon as if some frightful monster had entered the apartments, quærens quem devoret. There was, indeed, reason to retreat, to be alarmed, and to scream. An officer was placing two soldiers at the door of each drawing-room, and was advancing towards Danglars, preceded by a commissary of police, girded with his scarf. Madame Danglars uttered a scream and fainted. Danglars, who thought himself threatened (certain consciences are never calm),—Danglars even before his guests showed a countenance of abject terror.

“What is the matter, sir?” asked Monte Cristo, advancing to meet the commissioner.

“Which of you gentlemen,” asked the magistrate, without replying to the count, “answers to the name of Andrea Cavalcanti?”

A cry of astonishment was heard from all parts of the room. They searched; they questioned.

“But who then is Andrea Cavalcanti?” asked Danglars in amazement.

“A galley-slave, escaped from confinement at Toulon.”

“And what crime has he committed?”

“He is accused,” said the commissary with his inflexible voice, “of having assassinated the man named Caderousse, his former companion in prison, at the moment he was making his escape from the house of the Count of Monte Cristo.”

Monte Cristo cast a rapid glance around him. Andrea was gone.

A few minutes after the scene of confusion produced in the salons of M. Danglars by the unexpected appearance of the brigade of soldiers, and by the disclosure which had followed, the mansion was deserted with as much rapidity as if a case of plague or of cholera morbus had broken out among the guests.

In a few minutes, through all the doors, down all the staircases, by every exit, everyone hastened to retire, or rather to fly; for it was a situation where the ordinary condolences,—which even the best friends are so eager to offer in great catastrophes,—were seen to be utterly futile. There remained in the banker’s house only Danglars, closeted in his study, and making his statement to the officer of gendarmes; Madame Danglars, terrified, in the boudoir with which we are acquainted; and Eugénie, who with haughty air and disdainful lip had retired to her room with her inseparable companion, Mademoiselle Louise d’Armilly.

As for the numerous servants (more numerous that evening than usual, for their number was augmented by cooks and butlers from the Café de Paris), venting on their employers their anger at what they termed the insult to which they had been subjected, they collected in groups in the hall, in the kitchens, or in their rooms, thinking very little of their duty, which was thus naturally interrupted. Of all this household, only two persons deserve our notice; these are Mademoiselle Eugénie Danglars and Mademoiselle Louise d’Armilly.

The betrothed had retired, as we said, with haughty air, disdainful lip, and the demeanor of an outraged queen, followed by her companion, who was paler and more disturbed than herself. On reaching her room Eugénie locked her door, while Louise fell on a chair.

“Ah, what a dreadful thing,” said the young musician; “who would have suspected it? M. Andrea Cavalcanti a murderer—a galley-slave escaped—a convict!”

An ironical smile curled the lip of Eugénie. “In truth, I was fated,” said she. “I escaped the Morcerf only to fall into the Cavalcanti.”

“Oh, do not confound the two, Eugénie.”

“Hold your tongue! The men are all infamous, and I am happy to be able now to do more than detest them—I despise them.”

“What shall we do?” asked Louise.

“What shall we do?”

“Yes.”

“Why, the same we had intended doing three days since—set off.”

“What?—although you are not now going to be married, you intend still——”

“Listen, Louise. I hate this life of the fashionable world, always ordered, measured, ruled, like our music-paper. What I have always wished for, desired, and coveted, is the life of an artist, free and independent, relying only on my own resources, and accountable only to myself. Remain here? What for?—that they may try, a month hence, to marry me again; and to whom?—M. Debray, perhaps, as it was once proposed. No, Louise, no! This evening’s adventure will serve for my excuse. I did not seek one, I did not ask for one. God sends me this, and I hail it joyfully!”

“How strong and courageous you are!” said the fair, frail girl to her brunette companion.

“Did you not yet know me? Come, Louise, let us talk of our affairs. The post-chaise——”

“Was happily bought three days since.”

“Have you had it sent where we are to go for it?”

“Yes.”

“Our passport?”

“Here it is.”

And Eugénie, with her usual precision, opened a printed paper, and read:

“M. Léon d’Armilly, twenty years of age; profession, artist; hair black, eyes black; travelling with his sister.”

“Capital! How did you get this passport?”

“When I went to ask M. de Monte Cristo for letters to the directors of the theatres at Rome and Naples, I expressed my fears of travelling as a woman; he perfectly understood them, and undertook to procure for me a man’s passport, and two days after I received this, to which I have added with my own hand, ‘travelling with his sister.’”

“Well,” said Eugénie cheerfully, “we have then only to pack up our trunks; we shall start the evening of the signing of the contract, instead of the evening of the wedding—that is all.”

“But consider the matter seriously, Eugénie!”

“Oh, I am done with considering! I am tired of hearing only of market reports, of the end of the month, of the rise and fall of Spanish funds, of Haitian bonds. Instead of that, Louise—do you understand?—air, liberty, melody of birds, plains of Lombardy, Venetian canals, Roman palaces, the Bay of Naples. How much have we, Louise?”

The young girl to whom this question was addressed drew from an inlaid secretaire a small portfolio with a lock, in which she counted twenty-three bank-notes.

“Twenty-three thousand francs,” said she.

“And as much, at least, in pearls, diamonds, and jewels,” said Eugénie. “We are rich. With forty-five thousand francs we can live like princesses for two years, and comfortably for four; but before six months—you with your music, and I with my voice—we shall double our capital. Come, you shall take charge of the money, I of the jewel-box; so that if one of us had the misfortune to lose her treasure, the other would still have hers left. Now, the portmanteau—let us make haste—the portmanteau!”

“Stop!” said Louise, going to listen at Madame Danglars’ door.

“What do you fear?”

“That we may be discovered.”

“The door is locked.”

“They may tell us to open it.”

“They may if they like, but we will not.”

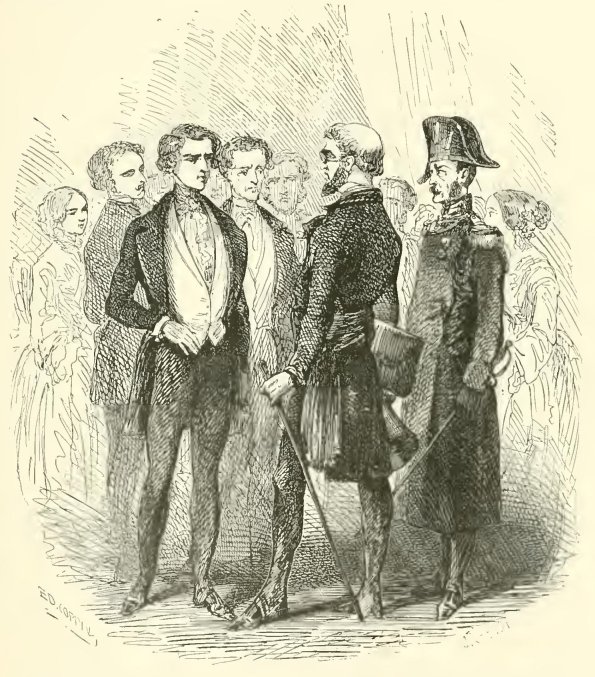

“You are a perfect Amazon, Eugénie!” And the two young girls began to heap into a trunk all the things they thought they should require.

“There now,” said Eugénie, “while I change my costume do you lock the portmanteau.” Louise pressed with all the strength of her little hands on the top of the portmanteau.

“But I cannot,” said she; “I am not strong enough; do you shut it.”

“Ah, you do well to ask,” said Eugénie, laughing; “I forgot that I was Hercules, and you only the pale Omphale!”

And the young girl, kneeling on the top, pressed the two parts of the portmanteau together, and Mademoiselle d’Armilly passed the bolt of the padlock through. When this was done, Eugénie opened a drawer, of which she kept the key, and took from it a wadded violet silk travelling cloak.

“Here,” said she, “you see I have thought of everything; with this cloak you will not be cold.”

“But you?”

“Oh, I am never cold, you know! Besides, with these men’s clothes——”

“Will you dress here?”

“Certainly.”

“Shall you have time?”

“Do not be uneasy, you little coward! All our servants are busy, discussing the grand affair. Besides, what is there astonishing, when you think of the grief I ought to be in, that I shut myself up?—tell me!”

“No, truly—you comfort me.”

“Come and help me.”

From the same drawer she took a man’s complete costume, from the boots to the coat, and a provision of linen, where there was nothing superfluous, but every requisite. Then, with a promptitude which indicated that this was not the first time she had amused herself by adopting the garb of the opposite sex, Eugénie drew on the boots and pantaloons, tied her cravat, buttoned her waistcoat up to the throat, and put on a coat which admirably fitted her beautiful figure.

“Oh, that is very good—indeed, it is very good!” said Louise, looking at her with admiration; “but that beautiful black hair, those magnificent braids, which made all the ladies sigh with envy,—will they go under a man’s hat like the one I see down there?”

“You shall see,” said Eugénie. And with her left hand seizing the thick mass, which her long fingers could scarcely grasp, she took in her right hand a pair of long scissors, and soon the steel met through the rich and splendid hair, which fell in a cluster at her feet as she leaned back to keep it from her coat. Then she grasped the front hair, which she also cut off, without expressing the least regret; on the contrary, her eyes sparkled with greater pleasure than usual under her ebony eyebrows.

“Oh, the magnificent hair!” said Louise, with regret.

“And am I not a hundred times better thus?” cried Eugénie, smoothing the scattered curls of her hair, which had now quite a masculine appearance; “and do you not think me handsomer so?”

“Oh, you are beautiful—always beautiful!” cried Louise. “Now, where are you going?”

“To Brussels, if you like; it is the nearest frontier. We can go to Brussels, Liège, Aix-la-Chapelle; then up the Rhine to Strasbourg. We will cross Switzerland, and go down into Italy by the Saint-Gothard. Will that do?”

“Yes.”

“What are you looking at?”

“I am looking at you; indeed you are adorable like that! One would say you were carrying me off.”

“And they would be right, pardieu!”

“Oh, I think you swore, Eugénie.”

And the two young girls, whom everyone might have thought plunged in grief, the one on her own account, the other from interest in her friend, burst out laughing, as they cleared away every visible trace of the disorder which had naturally accompanied the preparations for their escape. Then, having blown out the lights, the two fugitives, looking and listening eagerly, with outstretched necks, opened the door of a dressing-room which led by a side staircase down to the yard,—Eugénie going first, and holding with one arm the portmanteau, which by the opposite handle Mademoiselle d’Armilly scarcely raised with both hands. The yard was empty; the clock was striking twelve. The porter was not yet gone to bed. Eugénie approached softly, and saw the old man sleeping soundly in an armchair in his lodge. She returned to Louise, took up the portmanteau, which she had placed for a moment on the ground, and they reached the archway under the shadow of the wall.

Eugénie concealed Louise in an angle of the gateway, so that if the porter chanced to awake he might see but one person. Then placing herself in the full light of the lamp which lit the yard:

“Gate!” cried she, with her finest contralto voice, and rapping at the window.

The porter got up as Eugénie expected, and even advanced some steps to recognize the person who was going out, but seeing a young man striking his boot impatiently with his riding-whip, he opened it immediately. Louise slid through the half-open gate like a snake, and bounded lightly forward. Eugénie, apparently calm, although in all probability her heart beat somewhat faster than usual, went out in her turn.

A porter was passing and they gave him the portmanteau; then the two young girls, having told him to take it to No. 36, Rue de la Victoire, walked behind this man, whose presence comforted Louise. As for Eugénie, she was as strong as a Judith or a Delilah. They arrived at the appointed spot. Eugénie ordered the porter to put down the portmanteau, gave him some pieces of money, and having rapped at the shutter sent him away. The shutter where Eugénie had rapped was that of a little laundress, who had been previously warned, and was not yet gone to bed. She opened the door.

“Mademoiselle,” said Eugénie, “let the porter get the post-chaise from the coach-house, and fetch some post-horses from the hotel. Here are five francs for his trouble.”

“Indeed,” said Louise, “I admire you, and I could almost say respect you.” The laundress looked on in astonishment, but as she had been promised twenty louis, she made no remark.

In a quarter of an hour the porter returned with a post-boy and horses, which were harnessed, and put in the post-chaise in a minute, while the porter fastened the portmanteau on with the assistance of a cord and strap.

“Here is the passport,” said the postilion, “which way are we going, young gentleman?”

“To Fontainebleau,” replied Eugénie with an almost masculine voice.

“What do you say?” said Louise.

“I am giving them the slip,” said Eugénie; “this woman to whom we have given twenty louis may betray us for forty; we will soon alter our direction.”

And the young girl jumped into the britzka, which was admirably arranged for sleeping in, without scarcely touching the step.

“You are always right,” said the music teacher, seating herself by the side of her friend.

A quarter of an hour afterwards the postilion, having been put in the right road, passed with a crack of his whip through the gateway of the Barrière Saint-Martin.

“Ah,” said Louise, breathing freely, “here we are out of Paris.”

“Yes, my dear, the abduction is an accomplished fact,” replied Eugénie.

“Yes, and without violence,” said Louise.

“I shall bring that forward as an extenuating circumstance,” replied Eugénie.

These words were lost in the noise which the carriage made in rolling over the pavement of La Villette. M. Danglars no longer had a daughter.

And now let us leave Mademoiselle Danglars and her friend pursuing their way to Brussels, and return to poor Andrea Cavalcanti, so inopportunely interrupted in his rise to fortune. Notwithstanding his youth, Master Andrea was a very skilful and intelligent boy. We have seen that on the first rumor which reached the salon he had gradually approached the door, and crossing two or three rooms at last disappeared. But we have forgotten to mention one circumstance, which nevertheless ought not to be omitted; in one of the rooms he crossed, the trousseau of the bride-elect was on exhibition. There were caskets of diamonds, cashmere shawls, Valenciennes lace, English veils, and in fact all the tempting things, the bare mention of which makes the hearts of young girls bound with joy, and which is called the corbeille.22 Now, in passing through this room, Andrea proved himself not only to be clever and intelligent, but also provident, for he helped himself to the most valuable of the ornaments before him.

Furnished with this plunder, Andrea leaped with a lighter heart from the window, intending to slip through the hands of the gendarmes. Tall and well proportioned as an ancient gladiator, and muscular as a Spartan, he walked for a quarter of an hour without knowing where to direct his steps, actuated by the sole idea of getting away from the spot where if he lingered he knew that he would surely be taken. Having passed through the Rue du Mont-Blanc, guided by the instinct which leads thieves always to take the safest path, he found himself at the end of the Rue La Fayette. There he stopped, breathless and panting. He was quite alone; on one side was the vast wilderness of the Saint-Lazare, on the other, Paris enshrouded in darkness.

“Am I to be captured?” he cried; “no, not if I can use more activity than my enemies. My safety is now a mere question of speed.”

At this moment he saw a cab at the top of the Faubourg Poissonnière. The dull driver, smoking his pipe, was plodding along toward the limits of the Faubourg Saint-Denis, where no doubt he ordinarily had his station.

“Ho, friend!” said Benedetto.

“What do you want, sir?” asked the driver.

“Is your horse tired?”

“Tired? oh, yes, tired enough—he has done nothing the whole of this blessed day! Four wretched fares, and twenty sous over, making in all seven francs, are all that I have earned, and I ought to take ten to the owner.”

“Will you add these twenty francs to the seven you have?”

“With pleasure, sir; twenty francs are not to be despised. Tell me what I am to do for this.”

“A very easy thing, if your horse isn’t tired.”

“I tell you he’ll go like the wind,—only tell me which way to drive.”

“Towards the Louvres.”

“Ah, I know the way—you get good sweetened rum over there.”

“Exactly so; I merely wish to overtake one of my friends, with whom I am going to hunt tomorrow at Chapelle-en-Serval. He should have waited for me here with a cabriolet till half-past eleven; it is twelve, and, tired of waiting, he must have gone on.”

“It is likely.”

“Well, will you try and overtake him?”

“Nothing I should like better.”

“If you do not overtake him before we reach Bourget you shall have twenty francs; if not before Louvres, thirty.”

“And if we do overtake him?”

“Forty,” said Andrea, after a moment’s hesitation, at the end of which he remembered that he might safely promise.

“That’s all right,” said the man; “hop in, and we’re off! Who-o-o-pla!”

Andrea got into the cab, which passed rapidly through the Faubourg Saint-Denis, along the Faubourg Saint-Martin, crossed the barrier, and threaded its way through the interminable Villette. They never overtook the chimerical friend, yet Andrea frequently inquired of people on foot whom he passed and at the inns which were not yet closed, for a green cabriolet and bay horse; and as there are a great many cabriolets to be seen on the road to the Low Countries, and as nine-tenths of them are green, the inquiries increased at every step. Everyone had just seen it pass; it was only five hundred, two hundred, one hundred steps in advance; at length they reached it, but it was not the friend. Once the cab was also passed by a calash rapidly whirled along by two post-horses.

“Ah,” said Cavalcanti to himself, “if I only had that britzka, those two good post-horses, and above all the passport that carries them on!” And he sighed deeply.

The calash contained Mademoiselle Danglars and Mademoiselle d’Armilly.

“Hurry, hurry!” said Andrea, “we must overtake him soon.”

And the poor horse resumed the desperate gallop it had kept up since leaving the barrier, and arrived steaming at Louvres.

“Certainly,” said Andrea, “I shall not overtake my friend, but I shall kill your horse, therefore I had better stop. Here are thirty francs; I will sleep at the Cheval Rouge, and will secure a place in the first coach. Good-night, friend.”

And Andrea, after placing six pieces of five francs each in the man’s hand, leaped lightly on to the pathway. The cabman joyfully pocketed the sum, and turned back on his road to Paris. Andrea pretended to go towards the hotel of the Cheval Rouge, but after leaning an instant against the door, and hearing the last sound of the cab, which was disappearing from view, he went on his road, and with a lusty stride soon traversed the space of two leagues. Then he rested; he must be near Chapelle-en-Serval, where he pretended to be going.

It was not fatigue that stayed Andrea here; it was that he might form some resolution, adopt some plan. It would be impossible to make use of a diligence, equally so to engage post-horses; to travel either way a passport was necessary. It was still more impossible to remain in the department of the Oise, one of the most open and strictly guarded in France; this was quite out of the question, especially to a man like Andrea, perfectly conversant with criminal matters.

He sat down by the side of the moat, buried his face in his hands and reflected. Ten minutes after he raised his head; his resolution was made. He threw some dust over the topcoat, which he had found time to unhook from the antechamber and button over his ball costume, and going to Chapelle-en-Serval he knocked loudly at the door of the only inn in the place.

The host opened.

“My friend,” said Andrea, “I was coming from Mortefontaine to Senlis, when my horse, which is a troublesome creature, stumbled and threw me. I must reach Compiègne tonight, or I shall cause deep anxiety to my family. Could you let me hire a horse of you?”

An innkeeper has always a horse to let, whether it be good or bad. The host called the stable-boy, and ordered him to saddle Le Blanc then he awoke his son, a child of seven years, whom he ordered to ride before the gentleman and bring back the horse. Andrea gave the innkeeper twenty francs, and in taking them from his pocket dropped a visiting card. This belonged to one of his friends at the Café de Paris, so that the innkeeper, picking it up after Andrea had left, was convinced that he had let his horse to the Count of Mauléon, 25 Rue Saint-Dominique, that being the name and address on the card.

Le Blanc was not a fast animal, but he kept up an easy, steady pace; in three hours and a half Andrea had traversed the nine leagues which separated him from Compiègne, and four o’clock struck as he reached the place where the coaches stop. There is an excellent tavern at Compiègne, well remembered by those who have ever been there. Andrea, who had often stayed there in his rides about Paris, recollected the Bell and Bottle inn; he turned around, saw the sign by the light of a reflected lamp, and having dismissed the child, giving him all the small coin he had about him, he began knocking at the door, very reasonably concluding that having now three or four hours before him he had best fortify himself against the fatigues of the morrow by a sound sleep and a good supper. A waiter opened the door.

“My friend,” said Andrea, “I have been dining at Saint-Jean-aux-Bois, and expected to catch the coach which passes by at midnight, but like a fool I have lost my way, and have been walking for the last four hours in the forest. Show me into one of those pretty little rooms which overlook the court, and bring me a cold fowl and a bottle of Bordeaux.”

The waiter had no suspicions; Andrea spoke with perfect composure, he had a cigar in his mouth, and his hands in the pocket of his top coat; his clothes were fashionably made, his chin smooth, his boots irreproachable; he looked merely as if he had stayed out very late, that was all. While the waiter was preparing his room, the hostess arose; Andrea assumed his most charming smile, and asked if he could have No. 3, which he had occupied on his last stay at Compiègne. Unfortunately, No. 3 was engaged by a young man who was travelling with his sister. Andrea appeared in despair, but consoled himself when the hostess assured him that No. 7, prepared for him, was situated precisely the same as No. 3, and while warming his feet and chatting about the last races at Chantilly, he waited until they announced his room to be ready.

Andrea had not spoken without cause of the pretty rooms looking out upon the court of the Bell Hotel, which with its triple galleries like those of a theatre, with the jessamine and clematis twining round the light columns, forms one of the prettiest entrances to an inn that you can imagine. The fowl was tender, the wine old, the fire clear and sparkling, and Andrea was surprised to find himself eating with as good an appetite as though nothing had happened. Then he went to bed and almost immediately fell into that deep sleep which is sure to visit men of twenty years of age, even when they are torn with remorse. Now, here we are obliged to own that Andrea ought to have felt remorse, but that he did not.

This was the plan which had appealed to him to afford the best chance of his security. Before daybreak he would awake, leave the inn after rigorously paying his bill, and reaching the forest, he would, under pretence of making studies in painting, test the hospitality of some peasants, procure himself the dress of a woodcutter and a hatchet, casting off the lion’s skin to assume that of the woodman; then, with his hands covered with dirt, his hair darkened by means of a leaden comb, his complexion embrowned with a preparation for which one of his old comrades had given him the recipe, he intended, by following the wooded districts, to reach the nearest frontier, walking by night and sleeping in the day in the forests and quarries, and only entering inhabited regions to buy a loaf from time to time.

Once past the frontier, Andrea proposed making money of his diamonds; and by uniting the proceeds to ten bank-notes he always carried about with him in case of accident, he would then find himself possessor of about 50,000 livres, which he philosophically considered as no very deplorable condition after all. Moreover, he reckoned much on the interest of the Danglars to hush up the rumor of their own misadventures. These were the reasons which, added to the fatigue, caused Andrea to sleep so soundly. In order that he might wake early he did not close the shutters, but contented himself with bolting the door and placing on the table an unclasped and long-pointed knife, whose temper he well knew, and which was never absent from him.

About seven in the morning Andrea was awakened by a ray of sunlight, which played, warm and brilliant, upon his face. In all well-organized brains, the predominating idea—and there always is one—is sure to be the last thought before sleeping, and the first upon waking in the morning. Andrea had scarcely opened his eyes when his predominating idea presented itself, and whispered in his ear that he had slept too long. He jumped out of bed and ran to the window. A gendarme was crossing the court. A gendarme is one of the most striking objects in the world, even to a man void of uneasiness; but for one who has a timid conscience, and with good cause too, the yellow, blue, and white uniform is really very alarming.

“Why is that gendarme there?” asked Andrea of himself.

Then, all at once, he replied, with that logic which the reader has, doubtless, remarked in him, “There is nothing astonishing in seeing a gendarme at an inn; instead of being astonished, let me dress myself.” And the youth dressed himself with a facility his valet de chambre had failed to rob him of during the two months of fashionable life he had led in Paris.

“Now then,” said Andrea, while dressing himself, “I’ll wait till he leaves, and then I’ll slip away.”

And, saying this, Andrea, who had now put on his boots and cravat, stole gently to the window, and a second time lifted up the muslin curtain. Not only was the first gendarme still there, but the young man now perceived a second yellow, blue, and white uniform at the foot of the staircase, the only one by which he could descend, while a third, on horseback, holding a musket in his fist, was posted as a sentinel at the great street-door which alone afforded the means of egress. The appearance of the third gendarme settled the matter, for a crowd of curious loungers was extended before him, effectually blocking the entrance to the hotel.

“They’re after me!” was Andrea’s first thought. “Diable!”

A pallor overspread the young man’s forehead, and he looked around him with anxiety. His room, like all those on the same floor, had but one outlet to the gallery in the sight of everybody. “I am lost!” was his second thought; and, indeed, for a man in Andrea’s situation, an arrest meant the assizes, trial, and death,—death without mercy or delay.

For a moment he convulsively pressed his head within his hands, and during that brief period he became nearly mad with terror; but soon a ray of hope glimmered in the multitude of thoughts which bewildered his mind, and a faint smile played upon his white lips and pallid cheeks. He looked around and saw the objects of his search upon the chimney-piece; they were a pen, ink, and paper. With forced composure he dipped the pen in the ink, and wrote the following lines upon a sheet of paper:

“I have no money to pay my bill, but I am not a dishonest man; I leave behind me as a pledge this pin, worth ten times the amount. I shall be excused for leaving at daybreak, for I was ashamed.”

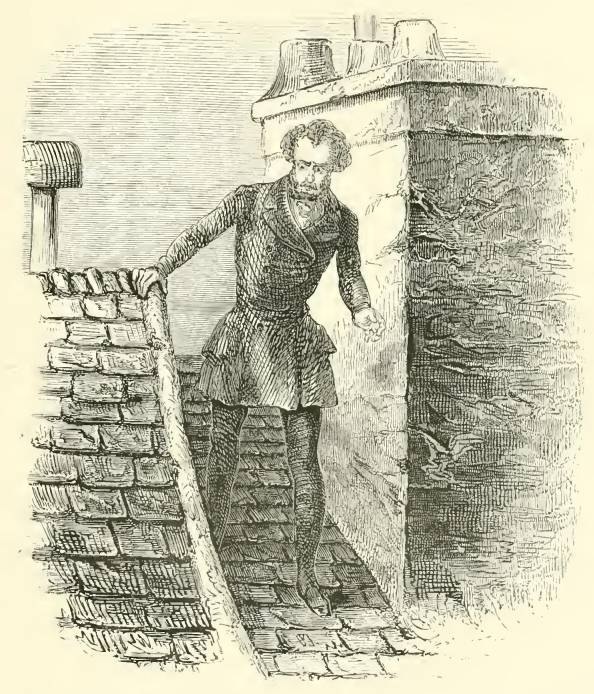

He then drew the pin from his cravat and placed it on the paper. This done, instead of leaving the door fastened, he drew back the bolts and even placed the door ajar, as though he had left the room, forgetting to close it, and slipping into the chimney like a man accustomed to that kind of gymnastic exercise, after replacing the chimney-board, which represented Achilles with Deidamia, and effacing the very marks of his feet upon the ashes, he commenced climbing the hollow tunnel, which afforded him the only means of escape left.

At this precise time, the first gendarme Andrea had noticed walked upstairs, preceded by the commissary of police, and supported by the second gendarme who guarded the staircase and was himself reinforced by the one stationed at the door.

Andrea was indebted for this visit to the following circumstances. At daybreak, the telegraphs were set at work in all directions, and almost immediately the authorities in every district had exerted their utmost endeavors to arrest the murderer of Caderousse. Compiègne, that royal residence and fortified town, is well furnished with authorities, gendarmes, and commissaries of police; they therefore began operations as soon as the telegraphic despatch arrived, and the Bell and Bottle being the best-known hotel in the town, they had naturally directed their first inquiries there.

Now, besides the reports of the sentinels guarding the Hôtel de Ville, which is next door to the Bell and Bottle, it had been stated by others that a number of travellers had arrived during the night. The sentinel who was relieved at six o’clock in the morning, remembered perfectly that, just as he was taking his post a few minutes past four, a young man arrived on horseback, with a little boy before him. The young man, having dismissed the boy and horse, knocked at the door of the hotel, which was opened, and again closed after his entrance. This late arrival had attracted much suspicion, and the young man being no other than Andrea, the commissary and gendarme, who was a brigadier, directed their steps towards his room. They found the door ajar.

“Oh, oh,” said the brigadier, who thoroughly understood the trick; “a bad sign to find the door open! I would rather find it triply bolted.”

And, indeed, the little note and pin upon the table confirmed, or rather corroborated, the sad truth. Andrea had fled. We say corroborated, because the brigadier was too experienced to be convinced by a single proof. He glanced around, looked in the bed, shook the curtains, opened the closets, and finally stopped at the chimney. Andrea had taken the precaution to leave no traces of his feet in the ashes, but still it was an outlet, and in this light was not to be passed over without serious investigation.

The brigadier sent for some sticks and straw, and having filled the chimney with them, set a light to it. The fire crackled, and the smoke ascended like the dull vapor from a volcano; but still no prisoner fell down, as they expected. The fact was, that Andrea, at war with society ever since his youth, was quite as deep as a gendarme, even though he were advanced to the rank of brigadier, and quite prepared for the fire, he had climbed out on the roof and was crouching down against the chimney-pots.

At one time he thought he was saved, for he heard the brigadier exclaim in a loud voice, to the two gendarmes, “He is not here!” But venturing to peep, he perceived that the latter, instead of retiring, as might have been reasonably expected upon this announcement, were watching with increased attention.

It was now his turn to look about him; the Hôtel de Ville, a massive sixteenth century building, was on his right; anyone could descend from the openings in the tower, and examine every corner of the roof below, and Andrea expected momentarily to see the head of a gendarme appear at one of these openings. If once discovered, he knew he would be lost, for the roof afforded no chance of escape; he therefore resolved to descend, not through the same chimney by which he had come up, but by a similar one conducting to another room.

He looked around for a chimney from which no smoke issued, and having reached it, he disappeared through the orifice without being seen by anyone. At the same minute, one of the little windows of the Hôtel de Ville was thrown open, and the head of a gendarme appeared. For an instant it remained motionless as one of the stone decorations of the building, then after a long sigh of disappointment the head disappeared. The brigadier, calm and dignified as the law he represented, passed through the crowd, without answering the thousand questions addressed to him, and re-entered the hotel.

“Well?” asked the two gendarmes.

“Well, my boys,” said the brigadier, “the brigand must really have escaped early this morning; but we will send to the Villers-Coterets and Noyon roads, and search the forest, when we shall catch him, no doubt.”

The honorable functionary had scarcely expressed himself thus, in that intonation which is peculiar to brigadiers of the gendarmerie, when a loud scream, accompanied by the violent ringing of a bell, resounded through the court of the hotel.

“Ah, what is that?” cried the brigadier.

“Some traveller seems impatient,” said the host. “What number was it that rang?”

“Number 3.”

“Run, waiter!”

At this moment the screams and ringing were redoubled.

“Aha!” said the brigadier, stopping the servant, “the person who is ringing appears to want something more than amwaiter; we will attend upon him with a gendarme. Who occupies Number 3?”

“The little fellow who arrived last night in a post-chaise with his sister, and who asked for an apartment with two beds.”

The bell here rang for the third time, with another shriek of anguish.

“Follow me, Mr. Commissary!” said the brigadier; “tread in my steps.”

“Wait an instant,” said the host; “Number 3 has two staircases,—inside and outside.”

“Good,” said the brigadier. “I will take charge of the inside one. Are the carbines loaded?”

“Yes, brigadier.”

“Well, you guard the exterior, and if he attempts to fly, fire upon him; he must be a great criminal, from what the telegraph says.”

The brigadier, followed by the commissary, disappeared by the inside staircase, accompanied by the noise which his assertions respecting Andrea had excited in the crowd.

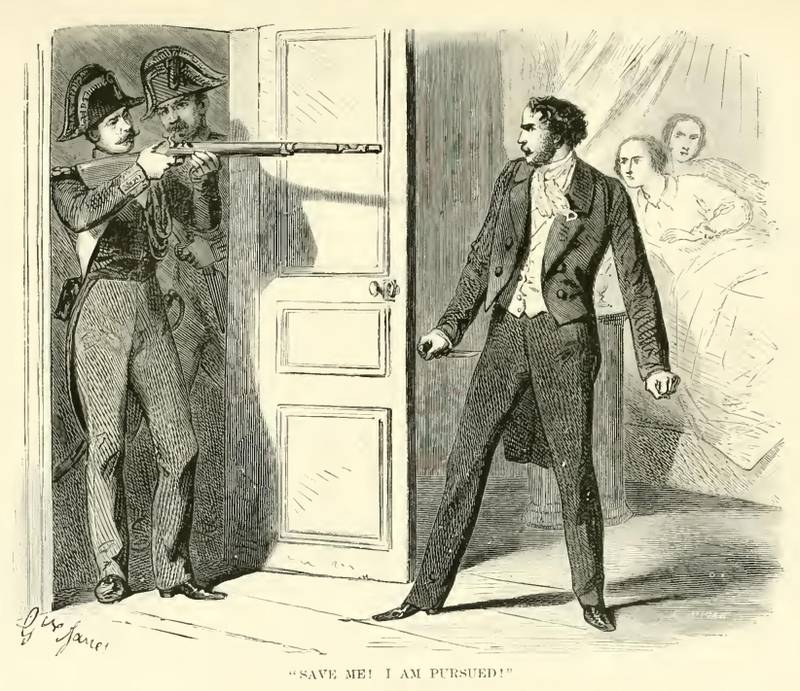

This is what had happened: Andrea had very cleverly managed to descend two-thirds of the chimney, but then his foot slipped, and notwithstanding his endeavors, he came into the room with more speed and noise than he intended. It would have signified little had the room been empty, but unfortunately it was occupied. Two ladies, sleeping in one bed, were awakened by the noise, and fixing their eyes upon the spot whence the sound proceeded, they saw a man. One of these ladies, the fair one, uttered those terrible shrieks which resounded through the house, while the other, rushing to the bell-rope, rang with all her strength. Andrea, as we can see, was surrounded by misfortune.

“For pity’s sake,” he cried, pale and bewildered, without seeing whom he was addressing,—“for pity’s sake do not call assistance! Save me!—I will not harm you.”

“Andrea, the murderer!” cried one of the ladies.

“Eugénie! Mademoiselle Danglars!” exclaimed Andrea, stupefied.

“Help, help!” cried Mademoiselle d’Armilly, taking the bell from her companion’s hand, and ringing it yet more violently.

“Save me, I am pursued!” said Andrea, clasping his hands. “For pity, for mercy’s sake do not deliver me up!”

“It is too late, they are coming,” said Eugénie.

“Well, conceal me somewhere; you can say you were needlessly alarmed; you can turn their suspicions and save my life!”

The two ladies, pressing closely to one another, and drawing the bedclothes tightly around them, remained silent to this supplicating voice, repugnance and fear taking possession of their minds.

“Well, be it so,” at length said Eugénie; “return by the same road you came, and we will say nothing about you, unhappy wretch.”

“Here he is, here he is!” cried a voice from the landing; “here he is! I see him!”

The brigadier had put his eye to the keyhole, and had discovered Andrea in a posture of entreaty. A violent blow from the butt end of the musket burst open the lock, two more forced out the bolts, and the broken door fell in. Andrea ran to the other door, leading to the gallery, ready to rush out; but he was stopped short, and he stood with his body a little thrown back, pale, and with the useless knife in his clenched hand.

“Fly, then!” cried Mademoiselle d’Armilly, whose pity returned as her fears diminished; “fly!”

“Or kill yourself!” said Eugénie (in a tone which a Vestal in the amphitheatre would have used, when urging the victorious gladiator to finish his vanquished adversary). Andrea shuddered, and looked on the young girl with an expression which proved how little he understood such ferocious honor.

“Kill myself?” he cried, throwing down his knife; “why should I do so?”

“Why, you said,” answered Mademoiselle Danglars, “that you would be condemned to die like the worst criminals.”