Danglars therefore continued to sleep, saying to himself that he would be sure to awake at the posting-house. The carriage stopped. Danglars fancied that they had reached the long-desired point; he opened his eyes and looked through the window, expecting to find himself in the midst of some town, or at least village; but he saw nothing except what seemed like a ruin, where three or four men went and came like shadows.

Danglars waited a moment, expecting the postilion to come and demand payment with the termination of his stage. He intended taking advantage of the opportunity to make fresh inquiries of the new conductor; but the horses were unharnessed, and others put in their places, without anyone claiming money from the traveller. Danglars, astonished, opened the door; but a strong hand pushed him back, and the carriage rolled on. The baron was completely roused.

“Eh?” he said to the postilion, “eh, mio caro?”

This was another little piece of Italian the baron had learned from hearing his daughter sing Italian duets with Cavalcanti. But mio caro did not reply. Danglars then opened the window.

“Come, my friend,” he said, thrusting his hand through the opening, “where are we going?”

“Dentro la testa!” answered a solemn and imperious voice, accompanied by a menacing gesture.

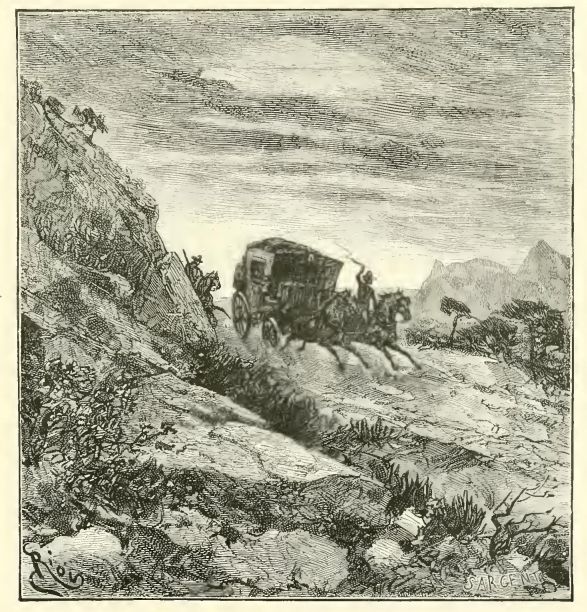

Danglars thought dentro la testa meant, “Put in your head!” He was making rapid progress in Italian. He obeyed, not without some uneasiness, which, momentarily increasing, caused his mind, instead of being as unoccupied as it was when he began his journey, to fill with ideas which were very likely to keep a traveller awake, more especially one in such a situation as Danglars. His eyes acquired that quality which in the first moment of strong emotion enables them to see distinctly, and which afterwards fails from being too much taxed. Before we are alarmed, we see correctly; when we are alarmed, we see double; and when we have been alarmed, we see nothing but trouble. Danglars observed a man in a cloak galloping at the right hand of the carriage.

“Some gendarme!” he exclaimed. “Can I have been intercepted by French telegrams to the pontifical authorities?”

He resolved to end his anxiety. “Where are you taking me?” he asked.

“Dentro la testa,” replied the same voice, with the same menacing accent.

Danglars turned to the left; another man on horseback was galloping on that side.

“Decidedly,” said Danglars, with the perspiration on his forehead, “I must be under arrest.” And he threw himself back in the calash, not this time to sleep, but to think.

Directly afterwards the moon rose. He then saw the great aqueducts, those stone phantoms which he had before remarked, only then they were on the right hand, now they were on the left. He understood that they had described a circle, and were bringing him back to Rome.

“Oh, unfortunate!” he cried, “they must have obtained my arrest.”

The carriage continued to roll on with frightful speed. An hour of terror elapsed, for every spot they passed showed that they were on the road back. At length he saw a dark mass, against which it seemed as if the carriage was about to dash; but the vehicle turned to one side, leaving the barrier behind and Danglars saw that it was one of the ramparts encircling Rome.

“Mon dieu!” cried Danglars, “we are not returning to Rome; then it is not justice which is pursuing me! Gracious heavens; another idea presents itself—what if they should be——”

His hair stood on end. He remembered those interesting stories, so little believed in Paris, respecting Roman bandits; he remembered the adventures that Albert de Morcerf had related when it was intended that he should marry Mademoiselle Eugénie. “They are robbers, perhaps,” he muttered.

Just then the carriage rolled on something harder than gravel road. Danglars hazarded a look on both sides of the road, and perceived monuments of a singular form, and his mind now recalled all the details Morcerf had related, and comparing them with his own situation, he felt sure that he must be on the Appian Way. On the left, in a sort of valley, he perceived a circular excavation. It was Caracalla’s circus. On a word from the man who rode at the side of the carriage, it stopped. At the same time the door was opened. “Scendi!” exclaimed a commanding voice.

Danglars instantly descended; although he did not yet speak Italian, he understood it very well. More dead than alive, he looked around him. Four men surrounded him, besides the postilion.

“Di quà,” said one of the men, descending a little path leading out of the Appian Way. Danglars followed his guide without opposition, and had no occasion to turn around to see whether the three others were following him. Still it appeared as though they were stationed at equal distances from one another, like sentinels. After walking for about ten minutes, during which Danglars did not exchange a single word with his guide, he found himself between a hillock and a clump of high weeds; three men, standing silent, formed a triangle, of which he was the centre. He wished to speak, but his tongue refused to move.

“Avanti!” said the same sharp and imperative voice.

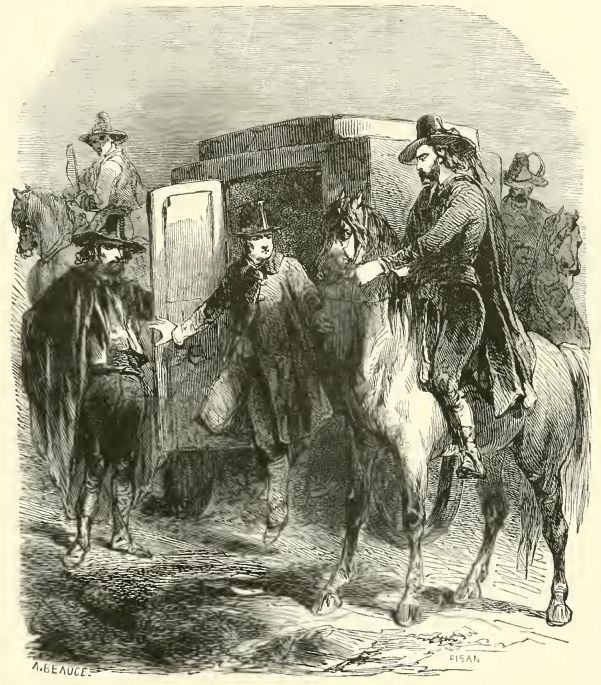

This time Danglars had double reason to understand, for if the word and gesture had not explained the speaker’s meaning, it was clearly expressed by the man walking behind him, who pushed him so rudely that he struck against the guide. This guide was our friend Peppino, who dashed into the thicket of high weeds, through a path which none but lizards or polecats could have imagined to be an open road.

Peppino stopped before a rock overhung by thick hedges; the rock, half open, afforded a passage to the young man, who disappeared like the evil spirits in the fairy tales. The voice and gesture of the man who followed Danglars ordered him to do the same. There was no longer any doubt, the bankrupt was in the hands of Roman banditti. Danglars acquitted himself like a man placed between two dangerous positions, and who is rendered brave by fear. Notwithstanding his large stomach, certainly not intended to penetrate the fissures of the Campagna, he slid down like Peppino, and closing his eyes fell upon his feet. As he touched the ground, he opened his eyes.

The path was wide, but dark. Peppino, who cared little for being recognized now that he was in his own territories, struck a light and lit a torch. Two other men descended after Danglars forming the rearguard, and pushing Danglars whenever he happened to stop, they came by a gentle declivity to the intersection of two corridors. The walls were hollowed out in sepulchres, one above the other, and which seemed in contrast with the white stones to open their large dark eyes, like those which we see on the faces of the dead. A sentinel struck the rings of his carbine against his left hand.

“Who comes there?” he cried.

“A friend, a friend!” said Peppino; “but where is the captain?”

“There,” said the sentinel, pointing over his shoulder to a spacious crypt, hollowed out of the rock, the lights from which shone into the passage through the large arched openings.

“Fine spoil, captain, fine spoil!” said Peppino in Italian, and taking Danglars by the collar of his coat he dragged him to an opening resembling a door, through which they entered the apartment which the captain appeared to have made his dwelling-place.

“Is this the man?” asked the captain, who was attentively reading Plutarch’s Life of Alexander.

“Himself, captain—himself.”

“Very well, show him to me.”

At this rather impertinent order, Peppino raised his torch to the face of Danglars, who hastily withdrew that he might not have his eyelashes burnt. His agitated features presented the appearance of pale and hideous terror.

“The man is tired,” said the captain, “conduct him to his bed.”

“Oh,” murmured Danglars, “that bed is probably one of the coffins hollowed in the wall, and the sleep I shall enjoy will be death from one of the poniards I see glistening in the darkness.”

From their beds of dried leaves or wolf-skins at the back of the chamber now arose the companions of the man who had been found by Albert de Morcerf reading Cæsar’s Commentaries, and by Danglars studying the Life of Alexander. The banker uttered a groan and followed his guide; he neither supplicated nor exclaimed. He no longer possessed strength, will, power, or feeling; he followed where they led him. At length he found himself at the foot of a staircase, and he mechanically lifted his foot five or six times. Then a low door was opened before him, and bending his head to avoid striking his forehead he entered a small room cut out of the rock. The cell was clean, though empty, and dry, though situated at an immeasurable distance under the earth. A bed of dried grass covered with goat-skins was placed in one corner. Danglars brightened up on beholding it, fancying that it gave some promise of safety.

“Oh, God be praised,” he said; “it is a real bed!”

This was the second time within the hour that he had invoked the name of God. He had not done so for ten years before.

“Ecco!” said the guide, and pushing Danglars into the cell, he closed the door upon him.

A bolt grated and Danglars was a prisoner. If there had been no bolt, it would have been impossible for him to pass through the midst of the garrison who held the catacombs of St. Sebastian, encamped round a master whom our readers must have recognized as the famous Luigi Vampa.

Danglars, too, had recognized the bandit, whose existence he would not believe when Albert de Morcerf mentioned him in Paris; and not only did he recognize him, but the cell in which Albert had been confined, and which was probably kept for the accommodation of strangers. These recollections were dwelt upon with some pleasure by Danglars, and restored him to some degree of tranquillity. Since the bandits had not despatched him at once, he felt that they would not kill him at all. They had arrested him for the purpose of robbery, and as he had only a few louis about him, he doubted not he would be ransomed.

He remembered that Morcerf had been taxed at 4,000 crowns, and as he considered himself of much greater importance than Morcerf he fixed his own price at 8,000 crowns. Eight thousand crowns amounted to 48,000 livres; he would then have about 5,050,000 francs left. With this sum he could manage to keep out of difficulties. Therefore, tolerably secure in being able to extricate himself from his position, provided he were not rated at the unreasonable sum of 5,050,000 francs, he stretched himself on his bed, and after turning over two or three times, fell asleep with the tranquillity of the hero whose life Luigi Vampa was studying.

We awake from every sleep except the one dreaded by Danglars. He awoke. To a Parisian accustomed to silken curtains, walls hung with velvet drapery, and the soft perfume of burning wood, the white smoke of which diffuses itself in graceful curves around the room, the appearance of the whitewashed cell which greeted his eyes on awakening seemed like the continuation of some disagreeable dream. But in such a situation a single moment suffices to change the strongest doubt into certainty.

“Yes, yes,” he murmured, “I am in the hands of the brigands of whom Albert de Morcerf spoke.” His first idea was to breathe, that he might know whether he was wounded. He borrowed this from Don Quixote, the only book he had ever read, but which he still slightly remembered.

“No,” he cried, “they have not wounded, but perhaps they have robbed me!” and he thrust his hands into his pockets. They were untouched; the hundred louis he had reserved for his journey from Rome to Venice were in his trousers pocket, and in that of his greatcoat he found the little note-case containing his letter of credit for 5,050,000 francs.

“Singular bandits!” he exclaimed; “they have left me my purse and pocket-book. As I was saying last night, they intend me to be ransomed. Hello, here is my watch! Let me see what time it is.”

Danglars’ watch, one of Breguet’s repeaters, which he had carefully wound up on the previous night, struck half past five. Without this, Danglars would have been quite ignorant of the time, for daylight did not reach his cell. Should he demand an explanation from the bandits, or should he wait patiently for them to propose it? The last alternative seemed the most prudent, so he waited until twelve o’clock. During all this time a sentinel, who had been relieved at eight o’clock, had been watching his door.

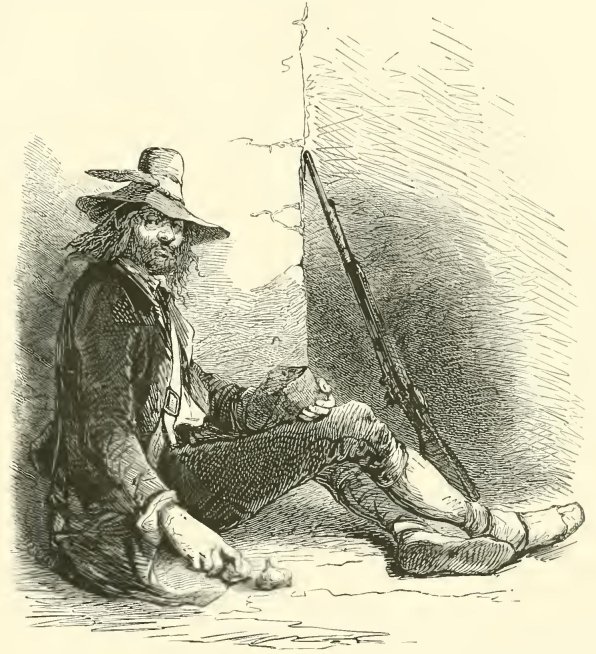

Danglars suddenly felt a strong inclination to see the person who kept watch over him. He had noticed that a few rays, not of daylight, but from a lamp, penetrated through the ill-joined planks of the door; he approached just as the brigand was refreshing himself with a mouthful of brandy, which, owing to the leathern bottle containing it, sent forth an odor which was extremely unpleasant to Danglars. “Faugh!” he exclaimed, retreating to the farther corner of his cell.

At twelve this man was replaced by another functionary, and Danglars, wishing to catch sight of his new guardian, approached the door again.

He was an athletic, gigantic bandit, with large eyes, thick lips, and a flat nose; his red hair fell in dishevelled masses like snakes around his shoulders.

“Ah, ha,” cried Danglars, “this fellow is more like an ogre than anything else; however, I am rather too old and tough to be very good eating!”

We see that Danglars was collected enough to jest; at the same time, as though to disprove the ogreish propensities, the man took some black bread, cheese, and onions from his wallet, which he began devouring voraciously.

“May I be hanged,” said Danglars, glancing at the bandit’s dinner through the crevices of the door,—“may I be hanged if I can understand how people can eat such filth!” and he withdrew to seat himself upon his goat-skin, which reminded him of the smell of the brandy.

But the mysteries of nature are incomprehensible, and there are certain invitations contained in even the coarsest food which appeal very irresistibly to a fasting stomach. Danglars felt his own not to be very well supplied just then, and gradually the man appeared less ugly, the bread less black, and the cheese more fresh, while those dreadful vulgar onions recalled to his mind certain sauces and side-dishes, which his cook prepared in a very superior manner whenever he said, “Monsieur Deniseau, let me have a nice little fricassee today.” He got up and knocked on the door; the bandit raised his head. Danglars knew that he was heard, so he redoubled his blows.

“Che cosa?” asked the bandit.

“Come, come,” said Danglars, tapping his fingers against the door, “I think it is quite time to think of giving me something to eat!”

But whether he did not understand him, or whether he had received no orders respecting the nourishment of Danglars, the giant, without answering, went on with his dinner. Danglars’ feelings were hurt, and not wishing to put himself under obligations to the brute, the banker threw himself down again on his goat-skin and did not breathe another word.

Four hours passed by and the giant was replaced by another bandit. Danglars, who really began to experience sundry gnawings at the stomach, arose softly, again applied his eye to the crack of the door, and recognized the intelligent countenance of his guide. It was, indeed, Peppino who was preparing to mount guard as comfortably as possible by seating himself opposite to the door, and placing between his legs an earthen pan, containing chick-peas stewed with bacon. Near the pan he also placed a pretty little basket of Villetri grapes and a flask of Orvieto. Peppino was decidedly an epicure. Danglars watched these preparations and his mouth watered.

“Come,” he said to himself, “let me try if he will be more tractable than the other;” and he tapped gently at the door.

“On y va,” (coming) exclaimed Peppino, who from frequenting the house of Signor Pastrini understood French perfectly in all its idioms.

Danglars immediately recognized him as the man who had called out in such a furious manner, “Put in your head!” But this was not the time for recrimination, so he assumed his most agreeable manner and said with a gracious smile:

“Excuse me, sir, but are they not going to give me any dinner?”

“Does your excellency happen to be hungry?”

“Happen to be hungry,—that’s pretty good, when I haven’t eaten for twenty-four hours!” muttered Danglars. Then he added aloud, “Yes, sir, I am hungry—very hungry.”

“And your excellency wants something to eat?”

“At once, if possible”

“Nothing easier,” said Peppino. “Here you can get anything you want; by paying for it, of course, as among honest folk.”

“Of course!” cried Danglars. “Although, in justice, the people who arrest and imprison you, ought, at least, to feed you.”

“That is not the custom, excellency,” said Peppino.

“A bad reason,” replied Danglars, who reckoned on conciliating his keeper; “but I am content. Let me have some dinner!”

“At once! What would your excellency like?”

And Peppino placed his pan on the ground, so that the steam rose directly under the nostrils of Danglars. “Give your orders.”

“Have you kitchens here?”

“Kitchens?—of course—complete ones.”

“And cooks?”

“Excellent!”

“Well, a fowl, fish, game,—it signifies little, so that I eat.”

“As your excellency pleases. You mentioned a fowl, I think?”

“Yes, a fowl.”

Peppino, turning around, shouted, “A fowl for his excellency!” His voice yet echoed in the archway when a handsome, graceful, and half-naked young man appeared, bearing a fowl in a silver dish on his head, without the assistance of his hands.

“I could almost believe myself at the Café de Paris,” murmured Danglars.

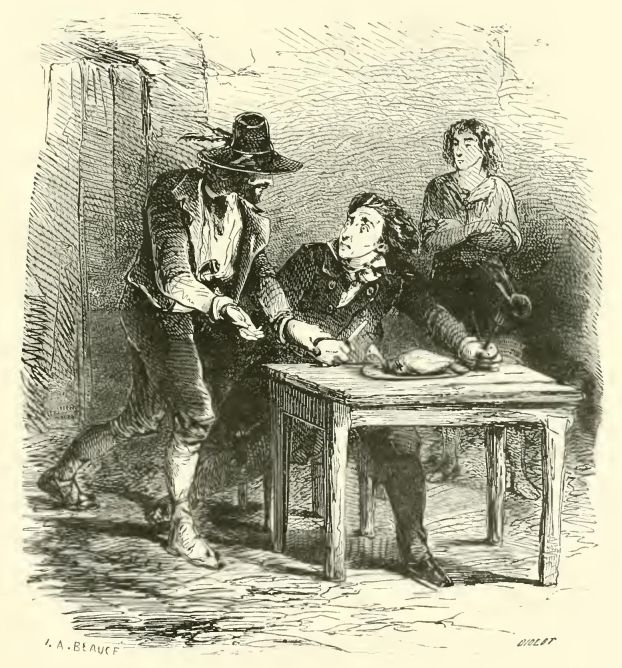

“Here, your excellency,” said Peppino, taking the fowl from the young bandit and placing it on the worm-eaten table, which with the stool and the goat-skin bed formed the entire furniture of the cell. Danglars asked for a knife and fork.

“Here, excellency,” said Peppino, offering him a little blunt knife and a boxwood fork. Danglars took the knife in one hand and the fork in the other, and was about to cut up the fowl.

“Pardon me, excellency,” said Peppino, placing his hand on the banker’s shoulder; “people pay here before they eat. They might not be satisfied, and——”

“Ah, ha,” thought Danglars, “this is not so much like Paris, except that I shall probably be skinned! Never mind, I’ll fix that all right. I have always heard how cheap poultry is in Italy; I should think a fowl is worth about twelve sous at Rome.—There,” he said, throwing a louis down.

Peppino picked up the louis, and Danglars again prepared to carve the fowl.

“Stay a moment, your excellency,” said Peppino, rising; “you still owe me something.”

“I said they would skin me,” thought Danglars; but resolving to resist the extortion, he said, “Come, how much do I owe you for this fowl?”

“Your excellency has given me a louis on account.”

“A louis on account for a fowl?”

“Certainly; and your excellency now owes me 4,999 louis.”

Danglars opened his enormous eyes on hearing this gigantic joke.

“Very droll,” he muttered, “very droll indeed,” and he again began to carve the fowl, when Peppino stopped the baron’s right hand with his left, and held out his other hand.

“Come, now,” he said.

“Is it not a joke?” said Danglars.

“We never joke,” replied Peppino, solemn as a Quaker.

“What! A hundred thousand francs for a fowl!”

“Ah, excellency, you cannot imagine how hard it is to rear fowls in these horrible caves!”

“Come, come, this is very droll—very amusing—I allow; but, as I am very hungry, pray allow me to eat. Stay, here is another louis for you.”

“Then that will make only 4,998 louis more,” said Peppino with the same indifference. “I shall get them all in time.”

“Oh, as for that,” said Danglars, angry at this prolongation of the jest,—“as for that you won’t get them at all. Go to the devil! You do not know with whom you have to deal!”

Peppino made a sign, and the youth hastily removed the fowl. Danglars threw himself upon his goat-skin, and Peppino, reclosing the door, again began eating his peas and bacon. Though Danglars could not see Peppino, the noise of his teeth allowed no doubt as to his occupation. He was certainly eating, and noisily too, like an ill-bred man. “Brute!” said Danglars. Peppino pretended not to hear him, and without even turning his head continued to eat slowly. Danglars’ stomach felt so empty, that it seemed as if it would be impossible ever to fill it again; still he had patience for another half-hour, which appeared to him like a century. He again arose and went to the door.

“Come, sir, do not keep me starving here any longer, but tell me what they want.”

“Nay, your excellency, it is you who should tell us what you want. Give your orders, and we will execute them.”

“Then open the door directly.” Peppino obeyed. “Now look here, I want something to eat! To eat—do you hear?”

“Are you hungry?”

“Come, you understand me.”

“What would your excellency like to eat?”

“A piece of dry bread, since the fowls are beyond all price in this accursed place.”

“Bread? Very well. Holloa, there, some bread!” he called. The youth brought a small loaf. “How much?” asked Danglars.

“Four thousand nine hundred and ninety-eight louis,” said Peppino; “You have paid two louis in advance.”

“What? One hundred thousand francs for a loaf?”

“One hundred thousand francs,” repeated Peppino.

“But you only asked 100,000 francs for a fowl!”

“We have a fixed price for all our provisions. It signifies nothing whether you eat much or little—whether you have ten dishes or one—it is always the same price.”

“What, still keeping up this silly jest? My dear fellow, it is perfectly ridiculous—stupid! You had better tell me at once that you intend starving me to death.”

“Oh, dear, no, your excellency, unless you intend to commit suicide. Pay and eat.”

“And what am I to pay with, brute?” said Danglars, enraged. “Do you suppose I carry 100,000 francs in my pocket?”

“Your excellency has 5,050,000 francs in your pocket; that will be fifty fowls at 100,000 francs apiece, and half a fowl for the 50,000.”

Danglars shuddered. The bandage fell from his eyes, and he understood the joke, which he did not think quite so stupid as he had done just before.

“Come,” he said, “if I pay you the 100,000 francs, will you be satisfied, and allow me to eat at my ease?”

“Certainly,” said Peppino.

“But how can I pay them?”

“Oh, nothing easier; you have an account open with Messrs. Thomson & French, Via dei Banchi, Rome; give me a draft for 4,998 louis on these gentlemen, and our banker shall take it.” Danglars thought it as well to comply with a good grace, so he took the pen, ink, and paper Peppino offered him, wrote the draft, and signed it.

“Here,” he said, “here is a draft at sight.”

“And here is your fowl.”

Danglars sighed while he carved the fowl; it appeared very thin for the price it had cost. As for Peppino, he examined the paper attentively, put it into his pocket, and continued eating his peas.

The next day Danglars was again hungry; certainly the air of that dungeon was very provocative of appetite. The prisoner expected that he would be at no expense that day, for like an economical man he had concealed half of his fowl and a piece of the bread in the corner of his cell. But he had no sooner eaten than he felt thirsty; he had forgotten that. He struggled against his thirst till his tongue clave to the roof of his mouth; then, no longer able to resist, he called out. The sentinel opened the door; it was a new face. He thought it would be better to transact business with his old acquaintance, so he sent for Peppino.

“Here I am, your excellency,” said Peppino, with an eagerness which Danglars thought favorable to him. “What do you want?”

“Something to drink.”

“Your excellency knows that wine is beyond all price near Rome.”

“Then give me water,” cried Danglars, endeavoring to parry the blow.

“Oh, water is even more scarce than wine, your excellency,—there has been such a drought.”

“Come,” thought Danglars, “it is the same old story.” And while he smiled as he attempted to regard the affair as a joke, he felt his temples get moist with perspiration.

“Come, my friend,” said Danglars, seeing that he made no impression on Peppino, “you will not refuse me a glass of wine?”

“I have already told you that we do not sell at retail.”

“Well, then, let me have a bottle of the least expensive.”

“They are all the same price.”

“And what is that?”

“Twenty-five thousand francs a bottle.”

“Tell me,” cried Danglars, in a tone whose bitterness Harpagon30 alone has been capable of revealing—“tell me that you wish to despoil me of all; it will be sooner over than devouring me piecemeal.”

“It is possible such may be the master’s intention.”

“The master?—who is he?”

“The person to whom you were conducted yesterday.”

“Where is he?”

“Here.”

“Let me see him.”

“Certainly.”

And the next moment Luigi Vampa appeared before Danglars.

“You sent for me?” he said to the prisoner.

“Are you, sir, the chief of the people who brought me here?”

“Yes, your excellency. What then?”

“How much do you require for my ransom?”

“Merely the 5,000,000 you have about you.” Danglars felt a dreadful spasm dart through his heart.

“But this is all I have left in the world,” he said, “out of an immense fortune. If you deprive me of that, take away my life also.”

“We are forbidden to shed your blood.”

“And by whom are you forbidden?”

“By him we obey.”

“You do, then, obey someone?”

“Yes, a chief.”

“I thought you said you were the chief?”

“So I am of these men; but there is another over me.”

“And did your superior order you to treat me in this way?”

“Yes.”

“But my purse will be exhausted.”

“Probably.”

“Come,” said Danglars, “will you take a million?”

“No.”

“Two millions?—three?—four? Come, four? I will give them to you on condition that you let me go.”

“Why do you offer me 4,000,000 for what is worth 5,000,000? This is a kind of usury, banker, that I do not understand.”

“Take all, then—take all, I tell you, and kill me!”

“Come, come, calm yourself. You will excite your blood, and that would produce an appetite it would require a million a day to satisfy. Be more economical.”

“But when I have no more money left to pay you?” asked the infuriated Danglars.

“Then you must suffer hunger.”

“Suffer hunger?” said Danglars, becoming pale.

“Most likely,” replied Vampa coolly.

“But you say you do not wish to kill me?”

“No.”

“And yet you will let me perish with hunger?”

“Ah, that is a different thing.”

“Well, then, wretches,” cried Danglars, “I will defy your infamous calculations—I would rather die at once! You may torture, torment, kill me, but you shall not have my signature again!”

“As your excellency pleases,” said Vampa, as he left the cell.

Danglars, raving, threw himself on the goat-skin. Who could these men be? Who was the invisible chief? What could be his intentions towards him? And why, when everyone else was allowed to be ransomed, might he not also be? Oh, yes; certainly a speedy, violent death would be a fine means of deceiving these remorseless enemies, who appeared to pursue him with such incomprehensible vengeance. But to die? For the first time in his life, Danglars contemplated death with a mixture of dread and desire; the time had come when the implacable spectre, which exists in the mind of every human creature, arrested his attention and called out with every pulsation of his heart, “Thou shalt die!”

Danglars resembled a timid animal excited in the chase; first it flies, then despairs, and at last, by the very force of desperation, sometimes succeeds in eluding its pursuers. Danglars meditated an escape; but the walls were solid rock, a man was sitting reading at the only outlet to the cell, and behind that man shapes armed with guns continually passed. His resolution not to sign lasted two days, after which he offered a million for some food. They sent him a magnificent supper, and took his million.

From this time the prisoner resolved to suffer no longer, but to have everything he wanted. At the end of twelve days, after having made a splendid dinner, he reckoned his accounts, and found that he had only 50,000 francs left. Then a strange reaction took place; he who had just abandoned 5,000,000 endeavored to save the 50,000 francs he had left, and sooner than give them up he resolved to enter again upon a life of privation—he was deluded by the hopefulness that is a premonition of madness.

He, who for so long a time had forgotten God, began to think that miracles were possible—that the accursed cavern might be discovered by the officers of the Papal States, who would release him; that then he would have 50,000 remaining, which would be sufficient to save him from starvation; and finally he prayed that this sum might be preserved to him, and as he prayed he wept. Three days passed thus, during which his prayers were frequent, if not heartfelt. Sometimes he was delirious, and fancied he saw an old man stretched on a pallet; he, also, was dying of hunger.

On the fourth, he was no longer a man, but a living corpse. He had picked up every crumb that had been left from his former meals, and was beginning to eat the matting which covered the floor of his cell. Then he entreated Peppino, as he would a guardian angel, to give him food; he offered him 1,000 francs for a mouthful of bread. But Peppino did not answer. On the fifth day he dragged himself to the door of the cell.

“Are you not a Christian?” he said, falling on his knees. “Do you wish to assassinate a man who, in the eyes of Heaven, is a brother? Oh, my former friends, my former friends!” he murmured, and fell with his face to the ground. Then rising in despair, he exclaimed, “The chief, the chief!”

“Here I am,” said Vampa, instantly appearing; “what do you want?”

“Take my last gold,” muttered Danglars, holding out his pocket-book, “and let me live here; I ask no more for liberty—I only ask to live!”

“Then you suffer a great deal?”

“Oh, yes, yes, cruelly!”

“Still, there have been men who suffered more than you.”

“I do not think so.”

“Yes; those who have died of hunger.”

Danglars thought of the old man whom, in his hours of delirium, he had seen groaning on his bed. He struck his forehead on the ground and groaned. “Yes,” he said, “there have been some who have suffered more than I have, but then they must have been martyrs at least.”

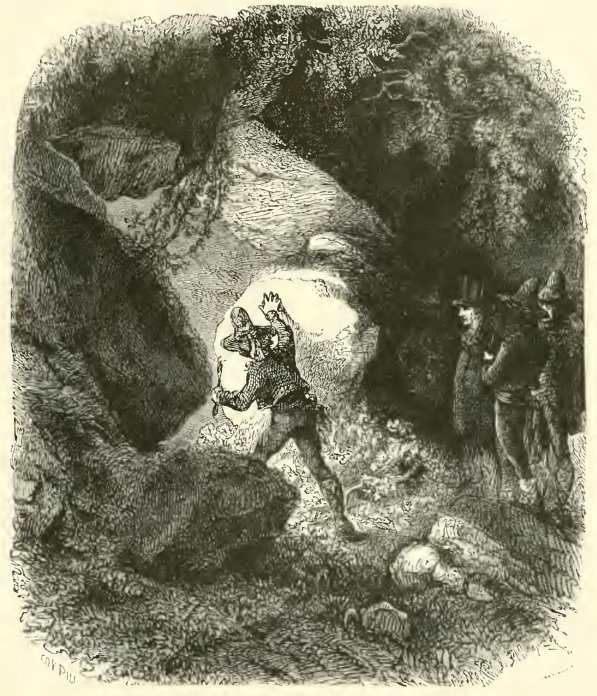

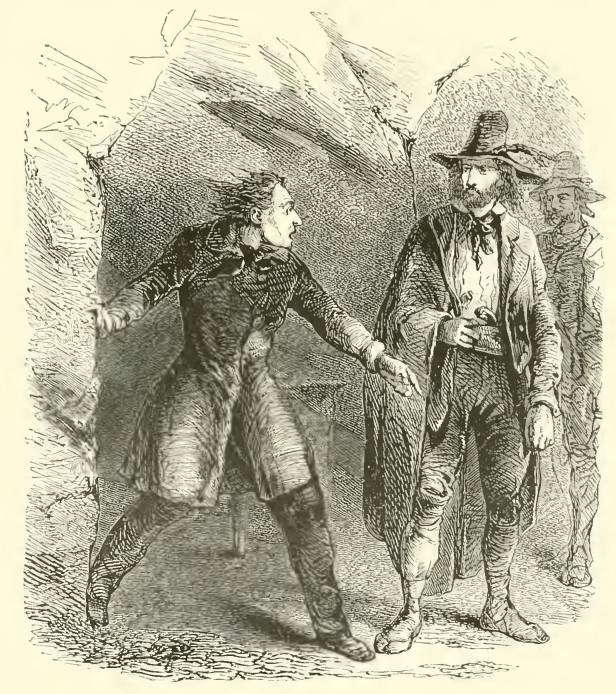

“Do you repent?” asked a deep, solemn voice, which caused Danglars’ hair to stand on end. His feeble eyes endeavored to distinguish objects, and behind the bandit he saw a man enveloped in a cloak, half lost in the shadow of a stone column.

“Of what must I repent?” stammered Danglars.

“Of the evil you have done,” said the voice.

“Oh, yes; oh, yes, I do indeed repent.” And he struck his breast with his emaciated fist.

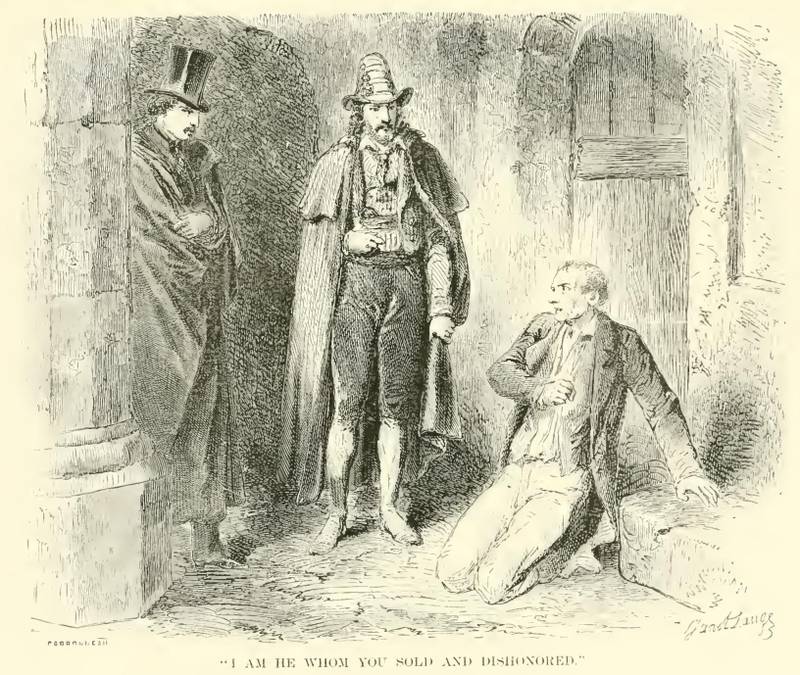

“Then I forgive you,” said the man, dropping his cloak, and advancing to the light.

“The Count of Monte Cristo!” said Danglars, more pale from terror than he had been just before from hunger and misery.

“You are mistaken—I am not the Count of Monte Cristo.”

“Then who are you?”

“I am he whom you sold and dishonored—I am he whose betrothed you prostituted—I am he upon whom you trampled that you might raise yourself to fortune—I am he whose father you condemned to die of hunger—I am he whom you also condemned to starvation, and who yet forgives you, because he hopes to be forgiven—I am Edmond Dantès!”

Danglars uttered a cry, and fell prostrate.

“Rise,” said the count, “your life is safe; the same good fortune has not happened to your accomplices—one is mad, the other dead. Keep the 50,000 francs you have left—I give them to you. The 5,000,000 you stole from the hospitals has been restored to them by an unknown hand. And now eat and drink; I will entertain you tonight. Vampa, when this man is satisfied, let him be free.”

Danglars remained prostrate while the count withdrew; when he raised his head he saw disappearing down the passage nothing but a shadow, before which the bandits bowed.

According to the count’s directions, Danglars was waited on by Vampa, who brought him the best wine and fruits of Italy; then, having conducted him to the road, and pointed to the post-chaise, left him leaning against a tree. He remained there all night, not knowing where he was. When daylight dawned he saw that he was near a stream; he was thirsty, and dragged himself towards it. As he stooped down to drink, he saw that his hair had become entirely white.

It was about six o’clock in the evening; an opal-colored light, through which an autumnal sun shed its golden rays, descended on the blue ocean. The heat of the day had gradually decreased, and a light breeze arose, seeming like the respiration of nature on awakening from the burning siesta of the south. A delicious zephyr played along the coasts of the Mediterranean, and wafted from shore to shore the sweet perfume of plants, mingled with the fresh smell of the sea.

A light yacht, chaste and elegant in its form, was gliding amidst the first dews of night over the immense lake, extending from Gibraltar to the Dardanelles, and from Tunis to Venice. The vessel resembled a swan with its wings opened towards the wind, gliding on the water. It advanced swiftly and gracefully, leaving behind it a glittering stretch of foam. By degrees the sun disappeared behind the western horizon; but as though to prove the truth of the fanciful ideas in heathen mythology, its indiscreet rays reappeared on the summit of every wave, as if the god of fire had just sunk upon the bosom of Amphitrite, who in vain endeavored to hide her lover beneath her azure mantle.

The yacht moved rapidly on, though there did not appear to be sufficient wind to ruffle the curls on the head of a young girl. Standing on the prow was a tall man, of a dark complexion, who saw with dilating eyes that they were approaching a dark mass of land in the shape of a cone, which rose from the midst of the waves like the hat of a Catalan.

“Is that Monte Cristo?” asked the traveller, to whose orders the yacht was for the time submitted, in a melancholy voice.

“Yes, your excellency,” said the captain, “we have reached it.”

“We have reached it!” repeated the traveller in an accent of indescribable sadness.

Then he added, in a low tone, “Yes; that is the haven.”

And then he again plunged into a train of thought, the character of which was better revealed by a sad smile, than it would have been by tears. A few minutes afterwards a flash of light, which was extinguished instantly, was seen on the land, and the sound of firearms reached the yacht.

“Your excellency,” said the captain, “that was the land signal, will you answer yourself?”

“What signal?”

The captain pointed towards the island, up the side of which ascended a volume of smoke, increasing as it rose.

“Ah, yes,” he said, as if awaking from a dream. “Give it to me.”

The captain gave him a loaded carbine; the traveller slowly raised it, and fired in the air. Ten minutes afterwards, the sails were furled, and they cast anchor about a hundred fathoms from the little harbor. The gig was already lowered, and in it were four oarsmen and a coxswain. The traveller descended, and instead of sitting down at the stern of the boat, which had been decorated with a blue carpet for his accommodation, stood up with his arms crossed. The rowers waited, their oars half lifted out of the water, like birds drying their wings.