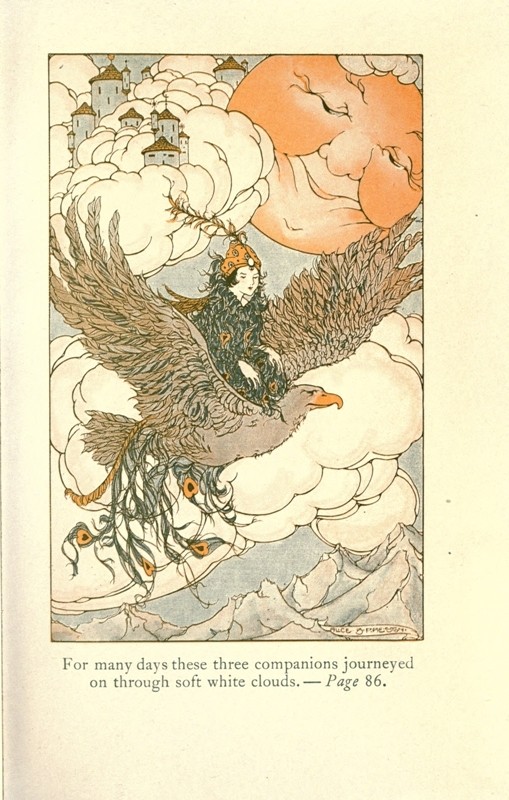

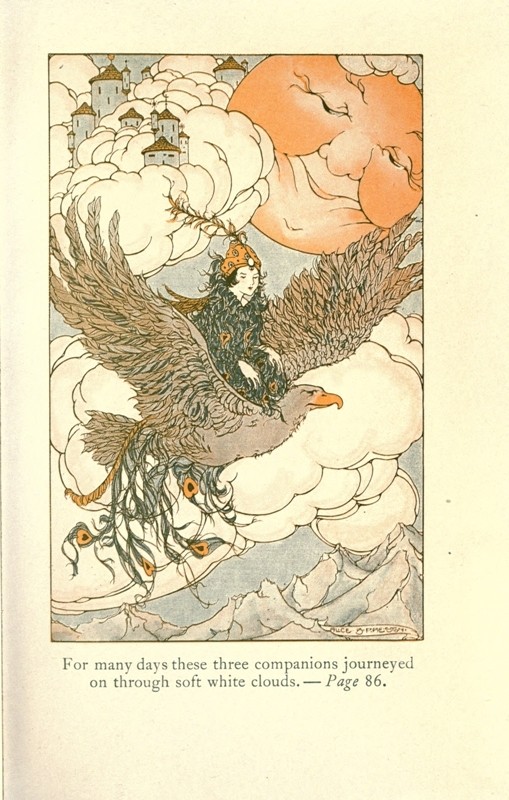

For many days these three

companions journeyed on through soft white clouds.—Page 86.

For many days these three

companions journeyed on through soft white clouds.—Page 86.

And so the good dame settled down to dwell in peace and happiness. Kings' palaces and dukes' castles were all very well, said she, but after all, there was no place like home. As for climate and a clear blue sky in summer, there was no place to equal the country quite close to the top of the earth, Dame Grumble thought. Often and often, just at candlelight, Dame Grumble peered into the dusk and gloom in hopes of seeing the Traveler coming toward her door; but he came not. Sometimes she asked the North Wind for news of him, but he could tell her little.

"I think," said the North Wind, "that the Traveler still journeys round the earth, but always in advance of me. Sometimes I travel over cities where all folk are content, and where there are no strifes nor quarrels. I hear folk speaking of a noble traveler who has lingered with them, and I have often thought it is the Traveler whom we seek. If I should ever meet him, I shall tell him that Dame Grumble waits each evening to welcome him."

"But my mistress, and you too, North Wind," said the Apple Tree, "have you not heard it said the Traveler visits only those who are sad and sorrowful, or who are afflicted with cold, selfish hearts? If that be true, he will return to our little cottage no more; there is no need for him."

Now it would seem that the Apple Tree was right, for the Traveler returned no more. And in all the world there was not such another place for comfort and good cheer as Dame Grumble's little cottage quite close to the top of the earth where the North Wind blew fiercely each spring.

Long, long ago, in a certain far-off region of the world, there was a land of ice and snow, and this land was called the Northland Kingdom. There each year the ice broke on the rivers and flowed out to the sea, and the snow melted in the valleys. Then corn and rye and other good grains would grow; but these mild seasons were short, and for the most part ice and snow abounded everywhere.

Added to this, in the time of my tale there was no light in the Northland Kingdom. All time was deep gray twilight or inky darkness, and there was no day. Neither Moon nor Stars had ever pierced the overhanging gloom and mists, and the sun had never shone upon the Northland Kingdom. Reindeer flitted silently through this land of shadows, and great white bears made their homes in icy caves by the sea. When birds of passage reached this land of darkness, they trilled their softest songs and went to rest, and when they waked, they soared away in search of brighter lands. But knowing nothing of the light of day, the folk of this dark land mourned not its lack and were content to dwell ever in shadow. A thousand silver lamps and myriads of waxen tapers gleamed always in the palace of the king; and in the fields the workers sowed and reaped by light of flaming torches. The herders built great fires on the hillsides, and in their light and warmth told their flocks. The housewives spun by firelight.

Now in the time of which I tell, the good king Tamna ruled the Northland Kingdom. He was a wealthy sovereign even as the wealth of kings is reckoned. King Tamna owned a thousand mountains of gold and silver and the fish of ten thousand streams. Herds of reindeer and caribou beyond all counting were also his, as well as the forests and plains over which they roamed. Beside all this, King Tamna was sovereign lord of one hundred princes of the Northland Kingdom. These hundred princes paid King Tamna tribute; that is to say, they brought him yearly certain portions of their flocks and herds and of their grain and gold and of all that was theirs, for such was the law of the Northland Kingdom.

Now good King Tamna had a daughter, Maiden Matanuska, Princess of the Silver Birches. She was so called because her marriage portion was a forest of silver birch that lay between two swift-flowing streams and reached from sea to sea. Some folk thought Maiden Matanuska was part wood sprite, for in spite of dark and shadows she would roam for hours in the paths and lanes among the birches and was not afraid. The Maiden Matanuska understood the language of the trees and learned from them just when the ice and snow would melt.

The silver foxes that roamed this forest were her pets. They frisked and followed her about like faithful dogs; and though their furs were worth a king's fortune, Maiden Matanuska would not consent to have them slain. For this the silver fox were grateful and loved her dearly. They taught her secrets never known before by men, and from their wisdom Maiden Matanuska learned to tell when icy winds would blow and snow begin to fall and when the grain would grow again. Maiden Matanuska understood the songs of birds as well, and when the birds of passage sang of other lands, where there was light of day, she listened eagerly. But when she begged these birds to sing her more, they answered her with sleepy chirps, for birds would not sing long in that dark land.

It was from these sweet songs the birds of passage sang that Maiden Matanuska came to know that there was such a thing as light of day. The more she heard, the more she longed to see this marvel. While she wandered in her birchen forest, she would dream bright dreams of other lands, she knew not where,—lands where ice and snow were not, but where gay flowers bloomed instead, and there was day as well as night.

"Oh, my father," said she with a sigh, "how pleasant our land would be if all the shadows and the gloom departed for a time and we had light of day as well as night."

"Ah, yes, my daughter," said King Tamna, with an answering sigh, "but how to brighten this dark land I know not. For your sake I would that I could; but for myself, I care not. Now I am growing old and soon must journey all alone to lands where light or darkness matters not."

"Oh, my father! Speak not of that time," cried Maiden Matanuska, bursting into tears. She loved her father tenderly and knew he spoke of the time when he must die. "If you were not here with me, neither light nor darkness would matter to me, and I should be desolate and lonely."

"Then speak no more of your longing for light," replied the king. "It grieves me that I cannot give you what you most desire. But before I have departed from this life, I hope to see you wedded to some brave prince who will love you and protect you in my place."

And though Maiden Matanuska vowed she wished no prince at all, her father gave her protests no heed. "There is a handsome youth who wears a feather mantle with whom I see you wandering in the forest. Who is he?" King Tamna asked.

"He is Prince Kenai of the burning mountain," said the maiden. "He, too, has dreams of light and tells me wonder tales which I do love to hear."

"Prince Kenai is the poorest prince in all the Northland Kingdom," said the king; "but if his wonder tales please you, I shall say nothing."

Now, as may be supposed, there was no lack of suitors for the maiden's hand. Indeed these hundred princes of the Northland Kingdom each longed to marry her. She was the fairest maiden in the land, and moreover, she was as lovely of mind and manner as she was fair of face.

There came at last a certain night when good King Tamna sat in state to greet his tribute-bearing princes, and Maiden Matanuska sat beside her father. In robes of purple velvet bordered deep with ermine and thickly sewn with threads of beaten gold, with golden crown and sceptre too, King Tamna looked a very king of kings,—a monarch of great state and dignity. The Maiden Matanuska, robed in shimmering gossamer white, her golden hair, that fell about her like a cloak, crowned with a wreath of leaves, and in her hand a holly branch, looked like some angel newly come from paradise. She seemed some lovely maiden in a dream, who would perhaps take flight and float away in the encircling gloom and mists. These hundred princes knelt before the throne and begged the lovely maiden's hand in marriage.

At this the king was troubled, for clearly Maiden Matanuska could not wed them all, and how to choose among them he knew not. At last the royal counselors advised him in the following way:

"Now since these hundred youths be princes all, and therefore suitable in rank to wed your daughter, let Maiden Matanuska for herself decide which one she'll wed."

When this was told, the Maiden Matanuska sat some time in thought and then she spoke. "I'll wed the prince who brings to me the thing which I have never seen before, for which I long with all my heart, and which I shall love well."

The hundred princes then departed to their various lands and began to seek among their treasures to find the thing they thought would please the maiden. Some princes brought her toys of ivory wrought in wondrous ways, and some brought robes of doeskin, soft as satin, white as milk, embroidered all in beads of many colors. But these proved not the thing for which the maiden longed. Some princes brought her great carved silver chests, and some brought chains and bracelets made of purest gold; but none of these were what the Maiden Matanuska wished, and all these princes failed to win their suit. So fared they all until at last there were but three to try their fate,—Prince Kathalan, Prince Katala, and Prince Kenai.

Now Prince Kathalan was the greatest warrior of all the Northland Kingdom. He had won a hundred battles and boasted that he would win a hundred more. He gloried in his warlike fame and doubted not that Maiden Matanuska would favor him above all others.

Katala, who was wealthiest prince of all, rejoiced because his slaves had lately found a diamond mine, the like of which was never known before in all the Northland Kingdom. Prince Katala had great faith in the power of his riches and was full sure that Maiden Matanuska would smile upon his suit.

Prince Kenai dwelt in the land of a burning mountain whose fires destroyed his forests and laid waste his lands, and the land itself, moreover, was not enriched with gold or silver or with any other metal. Because of this, Prince Kenai was called poorest prince of all; but because in all the Northland Kingdom none other dared venture near this burning mountain, he was counted bravest prince of all.

Of these three, Prince Kathalan spoke first. "Oh, Maiden Matanuska, Princess of the Silver Birch," cried he, "I bring to you this magic bird of battle, my raven. Black as its wings are, wise is the bird, and moreover it hath the gift of speech and prophecy. With this magic raven as my omen, no warrior can worst me in battle, and I can conquer legions. So marry me, O Maiden, and I will make you the most powerful queen the world has ever known."

The Maiden Matanuska shook her head. "You have not guessed my meaning rightly," answered she. "I care not to be a queen of power, for such queens are unhappy, I have often heard; and I hate the thought of battle. So keep your magic raven, warrior prince. I love far better the gentle doves that flutter around me in my forest."

Prince Kathalan departed in a rage, and Prince Katala stood before the throne.

"Oh, Maiden Matanuska, Princess of the Silver Birch," cried he, "I bring to you a golden casket filled full of gems called diamonds which you have never seen before, and which you will love well, for they are truly lovely. And these are not a thousandth part of all my wealth; so marry me, O Maiden, and I will make you the richest queen the world has ever known."

The gems within the casket flashed forth purple fire and shone like brilliant stars; but Maiden Matanuska sighed again.

"I care not for great riches, Prince Katala," answered she, "for I have riches of my own in goodly store. As for thy diamonds,—though they be truly lovely, as you say, I should as soon love the icicles that cluster round my casement in the storm. They are as hard and cold."

Prince Katala departed likewise in a rage, and Prince Kenai bowed low before the throne.

"And now what treasure do you bring to win my hand, brave prince?" asked Maiden Matanuska.

To which the prince replied, "I bring you none, and neither do I seek to win your hand. Your heart is what I do desire, O Maiden, for I do love you truly and would die to serve you.

"Now in your father's halls are treasures and all riches in great store. Fair silken banners hang the walls to shut the cold drafts out; a thousand gleaming silver lamps light the way; great chests are filled full of ornaments of beaten gold, as well as many other things my eyes have not discovered. With all this wealth heaped high on every hand, if you still long for that which you have never seen, think you that in my barren land it will be found? In my land so poor that even crows forsake it?"

"Well said, brave prince," the king replied, "and if you have not treasures such as men hold dear, you have indeed a noble gift of speech. But even so, some gift or token you must surely bring, or otherwise you had not come at all but stayed within your barren land. Come, tell us what it is."

"I bring no treasure save the treasure of a wonder tale which you will hear," said Prince Kenai, and then began to tell.

"Within my land, as well you know, there lies a burning mountain from which men flee in fear, but which I love. Now when my mountain has burst forth in flames, and tongues of fire that reach to heaven light the sky of all the world, I have seen wondrous things. I have seen other lands far distant, where ice and snow are not, but where the green grass clothes the hills and plains; where poppies shaped like golden chalices grow thick, and birds sing hour after hour. And in these pleasant lands of which I tell, there is a time of light as well as dark. This time of light lasts many hours long and is called day."

"Then tell me this, Prince Kenai," cried the king. "How comes this light of day to other lands? It comes not to this dreary realm of ours, where it would be most welcome."

"I'll tell you that," replied the prince. "There is a wondrous traveler called the Sun who high up in the clouds does journey ceaselessly about the world. He has great power over night and causes darkness to break forth in light wherever he does turn his face toward any land.

"And now farewell, good king and Maiden Matanuska, whom I love. I go to seek the Sun and beg him to return with me and shine upon the Northland Kingdom as he does on other lands upon the earth. Then will we have the light of day as well as night, and Maiden Matanuska will have that which she has never seen, for which she longs with all her heart, and which she will love well. Farewell."

Prince Kenai wrapped his flowing feather mantle around him and took leave of the king. The Maiden Matanuska walked with him through her forest where the silver birches grew down to the borders of the sea, and there they parted.

"Oh, my brave prince," wept Maiden Matanuska, "my heart cries out against your going, for since the day I met you I have loved you dearly; but I was always fearful lest my father bid me wed another because you had no fortune. Therefore I set the riddle which only you did guess. And now, may all good powers guard you on your quest and bring you safely back to me. While you are gone, the waking hours will often find me standing on this shore, awaiting the glad sight of your return."

"My beloved maiden!" sighed the prince. "With such sweet faith and love to bless me, I cannot fail." He rent his flowing feather mantle in two parts and wrapped a portion of it around the maiden. "I would I had a richer token for you, love," said he. "But even so; this feather mantle is no mean gift. Who wears it will be ever safe from icy blasts and snow and cold and will be ever young and fair as on the day they wore it first. Now kiss me in farewell and promise me that when I do return and bring the Sun, you'll marry me."

The Maiden Matanuska kissed him thrice and promised, and springing into his boat, Prince Kenai sailed away. She stood upon the shore and blew him kisses and caresses, but soon his form was lost in darkness and the mists, and Maiden Matanuska was left forlorn.

Now in those olden days, when princes journeyed around the world on errands for the maidens whom they loved, the space of time they usually were gone was a year and a day. So when a year and a day had passed, the Maiden Matanuska often wandered through the birch wood and stood upon the border of the sea. She strained her gaze far to the south to see the sight of any sail; but Prince Kenai came not.

She asked the birds of passage if they had seen her prince, and sometimes they had news of him. "Oh, tell me, ye wild Gulls, of the wild skies," she asked, "do you know aught of my brave Prince Kenai? He wears a feather robe like mine and seeks in lands afar to find the Sun for me."

"Ah, yes," replied the Gulls. "We've seen a prince so dressed, and he was sailing westward on the sea and seemed to seek the Sun."

"And found he what he sought?" cried Maiden Matanuska eagerly.

"Alas!" the Gulls replied. "The truth is, he did not. For many evenings when the day was done, we saw this prince sail westward. He hoped to meet the sun just where the sky bends down to meet the sea, but though he sailed for days and days, the place he sought seemed sailing too, and so he reached it not."

"That is sad news," the maiden sighed. "But when again you see my prince, tell him that all my thoughts are his, and I am sure he cannot fail."

Another time she asked a Kite-bird had he seen Prince Kenai.

"Oh, yes, dear maiden," the Kite-bird made reply. "And he was in the Southland, whither he had gone to seek the Sun. But he was worn and wearied with much wandering, and the road was long; and by the time he reached there, the Sun had long departed on his journey to the Eastland."

"That is sad news, good Kite-bird," said the maiden, "but when you see my prince again, pray tell him that my hopes are his, and I am sure he cannot fail to win his quest."

And still another time did Maiden Matanuska ask an Auk to tell her of Prince Kenai.

"I saw him," said the Auk, "and from the feather robe he wore I judged him first to be some bird. In lands where scarlet poppies lull the weary travelers to deep sleep, and waterfalls make thunder down the mountain sides, Prince Kenai I saw toiling up a rocky slope where it is said the Sun does rise."

"And did he reach the top of this steep slope?" asked Maiden Matanuska.

"Now that I could not say," the Auk replied, "for I was flying swiftly and paused not at all. But this I know; the Sun's a mighty, glowing being and is like to burn all those who venture near his presence. Unless Prince Kenai have some magic charm, I doubt if the Sun will heed him."

"That is the saddest news of all," sighed Maiden Matanuska. "But even so, I shall not weep but pray for him instead. When you next see my prince, good Auk, tell him that all my love is his, and I'll await his coming though he remain a thousand years."

"I shall," replied the Auk, and soared away.

And so the Maiden Matanuska waited while the time sped on. Wrapped in her feather mantle, she wandered through the birches like a lonely spirit, and the trees were grieved for her. She still dreamed dreams and loved to think about the time when she would greet her prince; when the light of day would banish all the gloom and shadows of the Northland Kingdom. Still years passed on, and still Prince Kenai came not. King Tamna feared him dead or that perhaps he had lost his way and was a wanderer forlorn; but Maiden Matanuska knew no fears.

"The journey to the Sun is long, my father," she would say, "and my brave prince no magic hath to make it short. He will return and bring with him this wondrous traveler whom he seeks, and what a pleasant place the Northland Kingdom then will be!"

But as the time went by there came great sadness in the Northland Kingdom. The good King Tamna laid him down to sleep one night and never waked again. All folk both high and low mourned deeply, for good King Tamna had been like a kindly father rather than a king. When at last the time of mourning passed, Lord Boreas, cousin to King Tamna, came to rule the Northland Kingdom.

Now Lord Boreas was a cruel sovereign, a tyrant, and the people were unhappy under his rule. He made harsh laws, and if these laws were not obeyed, he punished with severity. Lord Boreas, it was whispered, had an evil power over the icy winds and rivers in the Northland Kingdom, and few dared resist his will. His anger, it was said, had caused many a village to be blown into the sea and noble cities to be flooded with a rush of waters. But while the rule of this harsh king fell hard on all alike, on Maiden Matanuska it fell hardest. Lord Boreas was her guardian. He scorned the simple customs of the good King Tamna and straightway ordered all things to his liking. He planned to fell the Maiden Matanuska's forest and build a city in its place.

"However, my sweet cousin," said Lord Boreas, "I'll wait until the next mild season is at hand. Then when the silver foxes come from their winter's sleep, my hunters shall lay traps for them and slay them every one. Their skins will sell for gold, and for your marriage portion you shall have a noble city and ten thousand chests of gold, and I myself will marry you and make you queen."

Though Maiden Matanuska's heart was sad, and she wept bitter tears for her loved trees and pets, she made no protest at her cousin's words. She feared his wrath, and so she bowed her head submissively. But when the palace slept and all was still, wrapped in her feather mantle, she stole softly out. Down through the shadowy lanes and misty isles among the silver birches she sped, until she reached the border of the sea. Then through the gloom she peered to see the sight of any sail; but no sail she saw.

"Oh, my beloved prince," she wept, "I fear that when you come 'twill be too late. For rather than to wed my cruel cousin, I'll fling myself into the sea and die!"

"Now, Maiden Matanuska, what grave sorrow can this be?" a gruff voice spoke beside her. It was old Reynard, chief of all the silver foxes. He had stolen from the burrow to learn how went the season and to know when he might waken all his sleeping tribe.

"Oh, Reynard, my good friend!" exclaimed the maiden. "Since first you did begin your winter's sleep, I have had many sorrows. My father, good King Tamna, is no more, and now my cruel cousin Boreas rules the Northland Kingdom." She told her tale of sorrows, and old Reynard listened, all alert.

"Without a doubt, your cruel cousin Boreas hath an evil power over the winds and streams," said he, when she had finished, "but he shall learn it is not simple to outwit the cunning fox. Now in the past, as you, dear maiden, have protected me and all my tribe from harm, so will we now protect you in your need. Come, follow me; do as I bid, and all will yet be well." So saying, old Reynard then led the maiden down beneath the earth to where the silver foxes still slept their winter's sleep, and birch roots wound about in and out.

"Now, Maiden Matanuska," said Reynard, "if you will place a feather from your mantle at the root of every tree, they will be safe from cold and icy blasts, in spite of all Lord Boreas in his wrath may do. Then when that's done, wrap you all warmly in what's left of it and rest you safely with my people. When Prince Kenai comes I'll waken you."

The Maiden Matanuska did as Reynard bid, and far beneath the earth she hid herself from cruel Boreas. 'Twas well she did, for when her cousin found her fled, his anger knew no bounds. He sent great parties out to search the land, and he himself, with flaming torch in hand, set out to seek her in the forest. Among the birch trees he found traces, showing that the Maiden Matanuska passed that way. Upon a branch he found a scarlet ribbon she had worn, and in the thorn-bush was caught a silken scarf; but though he sought for hours and called her name, Lord Boreas could not find the maiden.

"Because I do not know the winding paths among the trees as well as you, you think to trick me, Maiden Matanuska," he cried at last, in fury, "but you shall know my vengeance now." Then climbing up the steep slopes of a near-by mountain, and summoning all his powers of evil, he commanded thus:

"Rise, rise, ye rivers that flow swiftly to the sea, until the birchen forest in the valley be all flooded with a mighty rush of waters! Then blow, ye chill winds, from the east and north until these waters to a solid wall of ice are all transformed."

The rivers, obedient at his command, then rose swiftly and overran their banks so that soon the tallest trees were all submerged, and nothing but a lake was seen. The winds began to blow their wildest, and the lake became a solid bank of ice that threw off chilling mists.

Then Boreas called the people of the Northland Kingdom and addressed them thus: "Behold the fate of Maiden Matanuska and beware! For so shall perish all who dare defy me."

The people wept and mourned in secret for the maiden whom they dearly loved, but there were none who dared cry out against the cruel Boreas.

Meanwhile Prince Kenai, bent upon his quest, was wandering still in lands afar. Each morning in the dawn he saw the wondrous traveler that he sought rise in the eastern sky and scatter clouds of darkness; and each evening, when the day was done, he saw the wondrous traveler set far in the west and take with him the day. But though Prince Kenai journeyed all around the earth and halfway back again, he found no road to reach the Sun, and he was sad. Still he continued on his way with hope and courage.

It happened once, while he lay sleeping on a mountain, an eagle wounded by a poison dart dropped down beside him.

"Ah!" cried the eagle bitterly, "from the great cloak of feathers which you wear, I thought you to be one of my own race. But since you are a man and I am wounded and can fly no more, I must prepare to die. You'll take my beak and claws to show your fellow men your skill at hunting and stuff my body to adorn your walls. Alas! That I, a prince of air, should come to this!" the great bird moaned.

"Fear not that I shall take your life, good eagle prince," said Prince Kenai. "For though I am not of your race, I am a prince of earth, and to my mind all princes, whether of the earth or air, should be as brothers."

Prince Kenai fetched water from a near-by spring and dressed the eagle's wound with healing herbs. For many days he did the same until the pain grew less, and by and by the great bird's wound was healed.

"Now, brother," said the eagle, when he could fly once more, "you've served me nobly, and in my turn I shall serve you to prove my gratitude. You told me of your quest to reach the Sun, and I will tell you this. There is no road to reach the Sun that mortal man may tread. The way lies through the clouds, and indeed, 'tis only I and all my brother eagles that have strength to travel there. So get you on my back without delay, good Prince Kenai, and we shall start."

Straight upward soared the eagle through the clouds, and when the day was nearly done they reached the splendid mansion of the Sun. Good luck was theirs, because the wondrous traveler had returned from his day's journey round the world and was well pleased to see them. He bade them welcome and asked the reason of their visit.

"Oh, Golden Sun," said Prince Kenai, "far in my land which is the Northland Kingdom, I learned that you had power over night and brought the light of day to lands wheresoever you did turn your face. Therefore I set out to seek you and entreat you to return with me and shine upon the Northland Kingdom, which is a land of night and darkness. All around the world I've followed you in vain, and never would have met you had not this good eagle borne me thither on his wings."

"Prince Kenai does not tell the reason why," exclaimed the eagle. "He saved my life when it was in his power to slay me, and, therefore, I have brought him hither, as was his wish." The eagle told his tale, and when the Sun had heard, he praised Prince Kenai.

"Now see," the Sun declared, "the mighty power of a kindly deed. Had you, Prince Kenai, slain this noble bird, as most men would have done, he had not brought you to my mansion, and you could not have begged this boon of me. For your reward, I'll go with you. To-morrow morning when I rise, we'll start for this dark land, and thou, my eagle, bear Prince Kenai on thy wings that he may all the faster lead the way."

For many days these three companions journeyed on through soft white clouds and summer skies until thick, gloomy mists came into view. The wind blew chill as though from fields of ice and snow, and the dull skies were leaden gray. From this, Prince Kenai knew the Northland Kingdom was at hand, although a pall of darkness overhung the landscape, and nothing could be seen.

For many days these three

companions journeyed on through soft white clouds.—Page 86.

For many days these three

companions journeyed on through soft white clouds.—Page 86.

"I'll soon change this!" exclaimed the Sun, and then began to shine full on the Northland Kingdom. Straightway all the scene began to change as though by magic. The lowering mists dissolved and rolled away in rosy clouds or formed gay-colored rainbows in the skies; the skies themselves changed to bright blue, all flecked with white instead of leaden gray. The birds of passage wakened from their sleep and sang their sweetest songs. Upon the mountain side the snow began to melt away, and many-colored flowers bloomed where it had been. No bank of ice or snow, however high or deep, was able to withstand the genial warmth of all the beams the Sun poured down. The wall of ice that bound the birchen forest broke and with a roar plunged down into the sea. Then upon the waves were seen a thousand glittering banks of ice that seemed like noble palaces afloat. The birch trees all began to bud and bloom with silvery leaves that rustled softly; and green grass, thick with violets, went creeping underfoot.

On learning what had come to pass, old Reynard wakened Maiden Matanuska and led her from the burrows until she stood once more upon the border of the sea.

"Oh, my beloved Prince Kenai!" she cried, as she beheld him. "Though in your absence I have suffered many sorrows, now that you are returned, I'll soon forget them all. How marvelous is the light of day! And how divine the Sun!"

"And tell me, maiden," said Prince Kenai, "now that you see all around the light of day, dost love it still as well as in the old dark days when you did dream of it?"

"Indeed, I find the light which you bring more lovely than my wildest dreams," she answered. "To see the smiling skies, the blue sea all a-sparkle with great glittering banks of ice, the green grass thick with flowers everywhere, and over all the Sun shine down in wealth of golden beams—I knew not how to dream a dream so fair; and next to thee, my prince, I love the light of day above all else."

Here they heard shouts of cheer and praise, and soon great multitudes of folk went running through the forest. "A miracle! A marvel 'tis," cried they, "that Maiden Matanuska is alive!" And then, in deep amazement, they listened to the tales the Maiden Matanuska and Prince Kenai told. Such tales were rare, even in those olden days of wonders. When both were done, the Chief Counselor of the Northland Kingdom spoke.

"Now listen, all good folk," said he, "and learn that in this very hour the cruel Boreas, fearing the great power of the Sun, has fled the Northland Kingdom, and we are now without a king. Whom shall we choose?"

"Prince Kenai! Prince Kenai!" cried the people. "'Twas he who gave our Maiden Matanuska the magic robe that saved her life; and he it was who brought the Sun to brighten our dark land. He was our benefactor; let him be our king!"

"Wilt be our king, Prince Kenai?" asked the counselor.

"If Maiden Matanuska marry me and be your queen, I shall be king," said Prince Kenai. "What say you, my loved one?"

"I'll marry you, my prince," she answered, "for I do love you truly. Our feather mantles which have so nobly served us in the past shall be our wedding robes; the birds our royal choristers; the birches tall our stately chapel walls, and the blue sky above all, glowing with the Golden Sun, shall be our ceiling. Your good eagle and my good Reynard shall stand beside us and let all folk both high and low be bidden to our feast to wish us joy and happiness."

All things were done as Maiden Matanuska ordered, and they were married on that very day. A royal feast was made, and sports and games were set; indeed there was a holiday that lasted forty days. The Sun was bidden to attend, and so well pleased was he that he stayed in the sky above the Northland Kingdom and set not once until the forty days had passed, and all that time was burning daylight.

Then, when the holiday was done at last, the Sun took leave. "Farewell, all folk, and you good king and queen," said he. "And though night come when I have turned my face from you, fear not. For in the morning I will come again and bring with me the light of day." Which thing he did.

And from that time the Northland Kingdom was no more a land of darkness and of gloom. The overhanging mists returned no more, and when 't was night, the Moon and Stars shone softly down. The Sun his face turned toward there every day, and though his beams were pale and wan when he was in the Southland, he stayed each summer forty days and nights and set not once; which custom he continues to this very day.

Prince Kenai and the Maiden Matanuska reigned many years and were beloved by all their subjects. Though scores of years passed, by virtue of their feather mantles they were always young and fair as on the day they wore them first. Indeed, 'tis said they never died, though folk who dwell still in the Northland Kingdom differ as to what became of them. Some say that when Prince Kenai and Maiden Matanuska grew weary of this life at last, they wrapped their feather mantles round them, and borne upon the eagle's wings, set off to visit at the mansion of the Sun. But other folk declare that on dark misty nights a pair resembling them are often seen to wander through the dim aisles of a certain birchen forest where the silver foxes are found.

Long, long ago, when the world was very young, so young that the flowers and trees and grasses had voices and talked with each other, or sang with the breezes that blew softly around them, there lived in the midst of a forest a very little tree.

Now, though the Little Tree was straight as an arrow and had glossy green leaves, she was the most unhappy little tree in all the world. She could not sing with the winds, and neither could she speak to the other trees around her. These other trees often spoke to the Little Tree and asked her questions. When she did not answer, they thought the Little Tree stupid and sulky. These other trees that could sing and speak began to grow tall, and after a time they grew so high their topmost branches seemed to touch the sky. Then, even though the Little Tree had spoken, they could never have heard her. These other trees grew tall as giants. The Little Tree grew each year, it is true; but she grew so slightly that it could scarcely be noticed. She was greatly ashamed of her small stature.

As the seasons went on, the branches of the tall trees grew so very thick that they shut out the light down in the forest. Then the Little Tree could not see the sun at all, and one by one the ferns and flowers at her roots died from the dampness, and the Little Tree was all alone! Nothing broke the silence of the dark, still forest save the calls of the birds when they returned each year to build their nests, or the sound of the branches swaying in the breeze. Then there came at last one soft spring day when the Little Tree waked from her winter's sleep and began to sing. She was so happy that she sang for hours; but alas! there was no other tree to hear her or to answer her song. So the Little Tree, though she now possessed the voice for which she had longed, was more lonely than ever before.

At night, when all the world was sleeping, and while the Night Wind roamed the forest, the Little Tree would weep softly to herself because she was so sad. Then, after a time, her lament grew to be a song, a very sad song, it is true; but oh, so very beautiful! The Night Wind, who was fond of singing, came to listen each evening for the Little Tree's lament, and as he blew upon his way, he carried her song to the Stars. Now it happened one night the Little Tree was so sad and lonely that she could not sing; instead, she wept until her tiny branches shook with sobbing.

"Oh," mourned the Little Tree, "I am so lonely here! I wish I could die. If only I might burn on some cottager's hearth or warm poor children's hands; but alas, I am the most useless tree that grows!"

The Night Wind heard the Little Tree sobbing, and going close, whispered softly to her:

"Oh, Little Tree, please do not be so sad. What does it matter that your singing voice came after all the other trees had grown too tall to hear you, or that you are such a very little tree? Your voice is so sweet and lovely that the birds of this forest now model their choicest songs on yours. Each night I carry your songs to the Stars, and they too have sung your lovely music."

"Oh, Night Wind, do you tell me true?" begged the Little Tree. "For I am such a little tree, how can the Stars hear me?"

"They hear you thus, my Little Tree," replied the Night Wind, and brushed aside the branches of the tallest trees.

Then looking up, the Little Tree beheld the Stars high up in the heavens shining down on her. They seemed to smile and beckon as she watched, and so she sang her sweetest songs to please them. The Night Wind and the Stars themselves sang with the Little Tree, and made such lovely music that had any one been listening, they would have thought they heard sweet strains from paradise. But all this happened when the world was very young, and there were but few people dwelling on it.

"And now, my Little Tree," the Night Wind said, when he had dropped the branches of the tall trees once again, "pray do not wish for some woodman to cut you down. I would miss you sadly, if you were to go away from the forest."

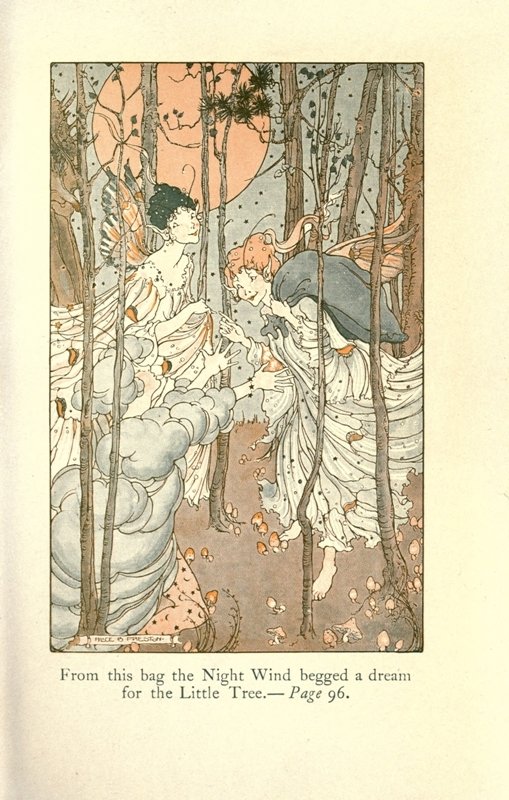

Farther on in the forest, the Night Wind met the Spirits of the Woods. They were two sister spirits robed in floating garments made of mists. They roamed the forest and cared for all the trees. They knew how long each tree would dwell in the forest and when the woodman's ax would fell it. The Spirits of the Woods possessed a magic bag of dreams, and from this bag the Night Wind begged a dream for the Little Tree.

"Ah," he pleaded, "the Little Tree is so sad and lonely, the other trees have grown so far away they cannot hear her sing, and neither can she talk with them. She would dearly love a beautiful dream from this dream bag of yours, Spirit."

"Ah, Night Wind," replied the Spirit doubtfully, "there is but one dream left, and that is the Little Tree's dream of the future. If we give it to her, you must promise that you will not answer her questions concerning it. For it is a strange dream and will puzzle her greatly. Will you promise?"

From this bag the Night Wind

begged a dream for the Little Tree.—Page 96.

From this bag the Night Wind

begged a dream for the Little Tree.—Page 96.

"I promise," said the Night Wind, and blew upon his way.

And after that night, the Little Tree was not lonely or sad. She never became a joyous tree—her youth had been too sorrowful for that—but she was content. Each night, when all the forest filled with creeping shadows, she sang her songs to the Stars, and she came to love the Night Wind dearly. Each night the Little Tree dreamed the dream the Spirits of the Woods had given her, and strange to tell, it was always the same dream. It was such a pleasant, lovely dream that sometimes the Little Tree was puzzled, and wondered whether she really lived in her beautiful dream, and only dreamed that she lived in the forest.

Each night the Little Tree dreamed she floated far away, until she reached a palace which was set on a high hill. Within the palace was a great hall richly hung with silken tapestries and gleaming softly with light that shone from carved crystal bowls. Within this palace hall a great king and his court were seated, and sweet strains of music floated on the breeze. But the strangest thing of all was this: the Little Tree often thought she heard her own songs in this palace hall. She was not sure, but she was greatly puzzled. She knew that she had dwelled always in the forest, and how could she know the music of noble lords and ladies? Then one night in her dream the Little Tree was startled to hear the sound of her own voice singing the songs she had so often sung to the Stars. She pressed eagerly to the palace window to see within, but because of her branches she could not go very near, and she could not see. Then came the dawn, and her dream floated far away.

All through the day, the Little Tree called again and again to the tall trees and asked them of her curious dream; but, of course, they could not hear her. She waited eagerly to see the daylight fade, and when the Night Wind came, she questioned him:

"Oh, Night Wind," cried the Little Tree, "will you tell me of my dream? I am sure I heard my own voice singing; but how could it be that noble lords and ladies within that palace hall would listen to me? For am I not the least of little trees?"

But the Night Wind did not tell her truly. He had given his promise that he would not, and so he answered her, saying:

"Now that I do not know, my dear, but though you are indeed the least of little trees, you are the only Little Tree in all this world to me. Of noble lords and ladies and their ways I know nothing, for do they not shut me from their homes and hearths when I would enter and warm myself? But now, Little Tree, it grows late; will you not sing for me?"

Thus with the Night Wind and the Stars for company, the Little Tree lived on for many years. From them she learned much wisdom and came to know about the great world which lay beyond the forest, and that all trees would one day go there. And all this time the world was growing older, and the forest was not so silent as it had been in the time when the Little Tree first dwelled there. Sometimes the woodcutter's ax rang out, and the Little Tree would hear a great tree come crashing down to earth.

"Oh, why must I leave the freedom of the forest and be torn limb from limb in some wretched mill!" cried one of the tall trees, as he fell close by the Little Tree one day.

"Ah," replied the Little Tree softly, "you would not wish to dwell forever in this forest, would you? In the world there is much that a great tree may do to bring happiness."

"Who is it that speaks to me thus gently?" asked the Fallen Tree. "I do not know the voice, although I thought I knew all trees growing in this forest, for I was among the first trees to grow here."

"And so was I," replied the Little Tree. "Do you not remember the Little Tree that could neither speak nor sing? I am she. For though I am ages and ages old, I am scarcely taller than yonder little fir of ten seasons."

"In those days we thought you stupid and sulky, Little Tree," replied the Fallen Tree, "but by your speech I now can see that we were wrong. Who has taught you all your wisdom, and have you not been lonely all these years?"

"Indeed, I was very lonely," said the Little Tree. "Even after I could sing, it was no better. The flowers and ferns had died, and there was none to hear me or talk to me. One night I wept and wished to die, and the Night Wind, who is of a kind heart, cheered me with words of praise. Since then I have never been sad, for I have had a lovely dream each night, and I have sung to the Stars."

But this the Fallen Tree could not believe, and so he answered sharply:

"Now, Little Tree, how can that be? Tall as I was, and high as I stood when I was monarch of this forest, never once could I send my songs to the Stars, although I tried to do so many times. Now surely such a little tree as you could not accomplish what a monarch failed to do! You have learned wisdom without doubt, and you sing very sweetly, I daresay; but take care lest your dreaming lead you in untruthful ways."

"Oh, pray believe me!" cried the Little Tree. "Wait only until the twilight comes, and the Night Wind himself will tell you so."

"More foolish talk!" scoffed the Fallen Tree. "The Night Wind is but a feeble creature to a monarch of the forest, such as I. When I stood aloft in all my glory, the Night Wind could not bend the smallest twig of mine unless I willed it so."

"That is true, my friends," spoke a gentle voice beside them. It was the voice of the Night Wind, for all unknown to them, darkness had fallen. "Because you were so proud and held your branches firm against my gentle breezes, never once did I carry your songs to the Stars; but I have done so for the Little Tree." Then he brushed aside the branches of the tall trees, and the Little Tree sang to her shining audience so far above in heaven. She sang until the Fallen Tree slept, and then the Night Wind gently dropped the branches until the forest was all dark once more. Then he kissed the Little Tree farewell and blew upon his way.

Now, as more people came to dwell upon the earth, more trees were needed every year to shelter them. The forest was no longer dark and silent. The woodman's ax rang out, and here and there the sun shone down where groves of noble trees had once stood. But even so, the ferns and flowers and grasses did not bloom again. The woodcutters made dusty roads and trails, and heaps of dead leaves eddied in the breeze. At last one day a certain king gave orders that all remaining trees of this forest should be cut down. He planned to build a noble city where the forest stood. Now charcoal fires flared all night, and herds of oxen tramped the whole day through, and soon a dreary waste of withering branches whose brown leaves crackled dismally was all that remained of the noble forest.

"Ah, Little Tree," the Night Wind mourned, "there is no longer any need for me. When the forest stood, it was my work and pleasure to brush the fallen leaves and lull the trees to sleep. Indeed, were it not for you, I would be desolate. Each night I tremble lest I shall not find you awaiting me."

"Ah, Night Wind," replied the Little Tree softly, "it is because you love me that you fear to lose me; but do not be troubled. I have seen great trees fall to my right and to my left, and small trees likewise, yet no one seems to want me. I am such a little tree; I am sure that you will find me here forever. That does not grieve me, even so, for I have come to love you dearly, and it would break my heart to be parted from you."

Then one dull winter's day, the Little Tree felt a human hand laid on her slender trunk, and she knew her fate had come. She was such a little tree that it took but two blows to fell her. When the Night Wind came again, he found the Little Tree moaning with the pain of her wounds. He caressed her tenderly and begged her to say her pain was better.

"Oh, Night Wind, the pain is truly better since you have come," whispered the Little Tree bravely, and died in his arms.

When the Night Wind knew the Little Tree was gone, he flung himself down on the earth beside her, and wept and wailed so bitterly that the Spirits of the Woods came from the ends of the world to see what troubled him.

"Ah," sighed the first Spirit. "How sad it is the Night Wind should be parted from the Little Tree. Could we not make him a mortal, so that he may meet her again in the world?"

"Agreed," replied the second Spirit. So while the Night Wind slept, the Spirits of the Woods changed him to a mortal and called him Robello.

Thus it was that some time later a youth called Robello came to dwell on the outskirts of the noble city which stood in place of the great forest. Now this Robello did not till the soil, and neither did he herd flocks on the hillsides. Instead, at evenings, he played his violin so sweetly and so sadly that some folk could not tell his music from the wailing of the winds. People from that region, as they passed his cottage at nightfall, paused to listen to Robello's playing, and many a one wiped a tear from his eye at the memories it stirred. Robello's fame began to go abroad, and wise men learned in the arts of song declared that if Robello but possessed a fine violin, the world could hear no better music.

Now, at this time it happened that the king (the same who had ordered the great forest cut down) received the gift of a rare violin. The maker of this violin vowed that its like was not to be found the whole world over, for when 'twas touched with the bow, it sent forth a sobbing sound like the cry of a broken heart. The maker of this rare violin besought the king and begged that no mere fiddler be allowed to touch it, and that a music master should play it always. The king agreed and accordingly commanded that all who played the violin should appear at the palace. Robello went in company of a thousand other players.

The palace of the king was set on a high hill, and as Robello entered, he seemed dimly to remember it, although he knew well that he had never been within its gates before. The king and court sat waiting within a great hall richly hung with silken tapestries and gleaming with lights that shone softly through carved crystal bowls. The violin players were gathered together, and to Robello fell the lot of playing first.

The king himself placed the violin in Robello's arms, and slowly, as though in a dream, Robello drew the bow across the strings. With the first notes wakened memories that had long been slumbering. Then as he played, Robello felt the great hall grow dim, until at last it seemed to fade away, and he saw naught but a vision: the deep dark forest just at dusk, and he was once more the Night Wind caressing the Little Tree.

"Ah, my Little Tree," he whispered, as he bent lovingly above the violin. "This is the dream that you did love so dearly. Do you remember me?"

"Ah, Night Wind," sang the Little Tree, "although they call thee by another name, to me thou wilt be the Night Wind forever. He who fashioned me thus spoke truly when he said I sobbed like a broken heart, for my heart has been broken with longing for thee. Let us sing the songs we sang to the Stars so long ago."

Then Robello played as he had never played before, and the violin sang as never violin had sung before. When the last notes died away, there were tears in the eyes of the noble lords and ladies, and the king sat silent for a time. At last he spoke, and ordered that all other players be sent away, and declared that none save Robello should ever touch this rare violin.

So Robello remained in the palace of the king and was made chief musician to his majesty, and never had the Little Tree sung so sweetly in the forest as she sang now at Robello's magic touch. Robello played at all court festivals, and nothing had such power to soothe the king as had Robello's music when he played his violin at nightfall.

Then came a sad day when his servants went to waken him and found Robello dead, his beloved violin clasped closely in his arms. The king and all his court mourned the passing of Robello for many days. Then one evening, just at dusk, they buried him with his beloved violin still clasped closely in his arms, and strewed his grave with boughs of trees. And in that region, to this day, there are some folk who say that when night falls Robello can still be heard playing his violin within the palace hall; but others say this is not right; it is the Night Wind calling softly to the Little Tree that never grew up.

There lived once long ago, in days of jesters and court fools and harlequins, a certain clown called Punchinello. This Punchinello, like all others of his trade, whitened his face and painted it in grotesque fashion. He wore gay satin robes of many colors all hung with silver bells that jingled when he danced, and pom-pom slippers turned up at the toes. This Punchinello was a clown of clowns, and his droll dances and his merry tricks and songs had made thousands laugh.

Punchinello traveled around the world in company with a circus. Whenever this circus reached a city, it formed a great parade before it entered. Then would the people throng the streets and highways, eager for the show. They clapped their hands when lions roaring in their cages and elephants led by their keepers passed along; but when this famous Punchinello, prancing and twirling, came in view, the crowds cheered wildly with applause.

"Oh, welcome! Welcome, Punchinello!" they would shout.

The ladies threw him flowers and children blew him kisses. Kings and queens had often hailed him thus, for Punchinello pleased all folk. Those who were sad and those who sorrowed often sent for Punchinello when the circus show was done, and he would dance and sing to cheer them. But for this service he would take no gold or present. So though he grew to fame, this Punchinello grew not rich.

"It is enough that I can make sad faces glad," said Punchinello, and wrapping his great cloak about him, he would steal away, leaving happiness behind him.

"My store of wealth lies in the golden smiles my antics bring," he often said, "and when my merry songs and dances please the world no more, I shall be poor indeed." But with his light, fantastic dancing, and his songs and jests, with his twirlings and his leapings,—was it likely that the world would ever cease to smile on Punchinello? The world is always fond of fun and laughter.

"Punchinello is the greatest man in all the world," some folk said when they had seen him dance and heard him sing.

"That is not right," said others. "He would be emperor if that were true; but Punchinello is the greatest man in all the circus."

"But neither is that right," still others said. "For if he were, he would be owner of the circus. But Punchinello is the greatest clown in all the world." And on this all folk agreed.

Now on its way about the world, the circus chanced to journey to a city where a king and queen held court. These royal folk and all their court watched the gay procession from their balconies and were delighted. The king and queen sent heralds, saying on a certain night that they would grace the show and to be sure that Master Punchinello played before the royal box. Then as the pageant wound upon its way, with banners flying and with music of the fife and drum, they passed a building where the sick were tended. It was a hospital. No eager faces gave them welcome here, and lest they should disturb the sick, the fife and drum ceased playing. Punchinello fell to walking soberly along. Suddenly he chanced to spy a tiny, wistful face pressed to the window pane. Then Punchinello bounded lightly up the ladder, and leaping into the room, began to dance and twirl about to please this little child.

"And does my dancing please you, little one?" asked Punchinello when he paused.

"Oh, yes, sir!" cried the child. His name was Beppo. "Please dance again for me. It makes my pain grow better."

"Alas! I cannot, little one," said Punchinello, pointing to the circus that was passing. "I must make haste to join my friends again."

"Then would you come to-night when it is dark and dance for me?" begged little Beppo. "The pain is always worse when it is dark, you know."

"Indeed, I'll come, my little one," said kindly Punchinello, and his gayly painted face grew sad. "Just leave your window open, little one, and I'll steal in and dance for you and sing you to the land of happy dreams."

And that night, when the circus show was done and all the lights were out, while other tired players slept, this kindly Punchinello wrapped his cloak about him and stole out underneath the stars to visit little Beppo. The little lame child was delighted with his songs and dances, so kindly Punchinello vowed that he would come each night and do the same, while the circus remained in the city. Each night the child lay waiting for him eagerly, and how he hugged and kissed this Punchinello when at last he came!

"Last night I dreamed of running through the woods," cried little Beppo to him one night. "I saw tall trees that seemed to touch the sky and heard the birds sing in their nests. I never had a dream like this before, and your sweet songs did give it to me, Punchinello. Come, dance and sing for me."

Then Punchinello danced his best. His slippered feet like lightning flew; the bells upon his robes rang out, and he would twirl upon his toes until his many-colored baggy robes stood out and he seemed like a brilliant human top. He jumped, he twirled, he leaped high in the air and bowed before the little cot as though it were a royal throne. When he at last grew weary, he would stop, but then the child would beg for more.

"Oh, please, dear Punchinello," he would say, "just once again. It makes my pain grow less to see you whirl." Then Punchinello could not refuse, and he would whirl and twirl again until he was too weary to do more. Folding little Beppo in his arms, he sang him lullabies until the child fell fast asleep. And so the nights went on.

The nurses noticed that little Beppo's cheeks grew plump and that his eyes grew bright. He said his pain was better, and they thought it was the medicine. They knew nothing of this Punchinello. He entered each night through the window and departed the same way. The circus folk said Punchinello was not well and told him he must rest.

"Our show would be as nothing if it were not for you, Punchinello," they declared. "To-morrow the king and queen will come to see us play, so rest you well to-night that you may dance your gayest for them." Though Punchinello promised, late that night, when all the world lay sleeping, he stole away to dance for little Beppo.

"Oh, Punchinello!" cried the little lame child. "I'll tell you of my dream. I dreamed I wore a spotted satin robe like yours and pom-pom slippers turned up at the toes. I dreamed I danced and twirled as lightly as you do yourself. Now is that not a pleasant dream for one who cannot even walk?"

"It is, my little one," said Punchinello. "Come sit upon my knee and wind your arms about my neck. Now tell me, has your pain been less to-day?"

"Much less, much less, good Punchinello," said the child. "Indeed, I think your dances and your songs have charmed it all away. I think about my lovely dreams by day, and lie and wait for you by night, and have no time for pain, it seems. Come dance for me, my Punchinello."

"To-night I'll sing instead, my little Beppo," answered Punchinello. He was weary, and when he whirled his head grew dizzy. "I'll sing you a song of ships that sail through seas of clouds; and trees as sing the world to slow sleep when winds do blow."

But little Beppo wished to see him dance. "See, Punchinello," said he softly, "around your neck I tie my locket. It is my only treasure. They say my mother placed it on me when she died. It has a bluebird painted on it which is the only bird I've ever seen. Now wilt thou dance for me, dear Punchinello?" He kissed the clown's queer painted face, and Punchinello danced.

And never had he danced so well before. As though he heard afar the music that the fairies make at midnight, he waltzed and twirled faster and yet faster, pausing not at all. He pranced, he leaped and spun upon his toe as though he were a dancing doll wound up to dance so long. The little lame child watched him eagerly, and as he watched, as though he too heard magic strains from fairyland, he sprung up from his cot and straightway danced and whirled about in Punchinello's footsteps.

"Look, look, dear Punchinello!" little Beppo cried. "I am no longer lame but dance as well as you yourself."