So at last, after much thought,

the goose girl did as the blue gander bade.—Page 237.

So at last, after much thought,

the goose girl did as the blue gander bade.—Page 237.

sang the old man and his old wife as they climbed up the steep hill.

sang King Crosspatch and Queen Grumpy, and they went trudging down. Then when they reached the snug little cottage, how pleased they were to be sure! Everything was so cozy and comfortable to behold. The kettle on the hearth was boiling, and the loaves in the oven were browning; the bird in the cage was singing, and the cat on the cushion was purring. The table was laid with all manner of good things for tea.

"The blackberry pie! The blackberry pie! My dear, let's have it at once!" cried King Crosspatch, and went searching through cupboard and larder to find it.

"Wait just a moment until I have made the tea," answered Queen Grumpy, busily bustling about the kitchen. She made the tea, and he found the blackberry pie, and then they both sat down to supper. There were ever and ever so many good things on the table. There were cold roast fowls and quince preserves; there were strawberry tarts and plum as well; there was fresh new butter, and there was thick sweet cream. Queen Grumpy and King Crosspatch ate them all and then began to think about dessert!

"Now would you mind, my dear, if I should eat all the blackberry pie myself?" asked King Crosspatch of Queen Grumpy. "You see, I have only read about blackberry pie in books and have never tasted one in all my life before."

"Not at all, my dear!" replied Queen Grumpy most amiably. "I intend to eat all this ginger cake which I have never seen or tasted before." And so this royal old couple continued to eat until both larder and cupboard were bare.

"How fine this little cottage is and how very snug!" said Queen Grumpy, seating herself in a rocker before the blazing logs. She began to knit on a gray wool sock she found. "I think we shall be very happy here."

"And I think so too," agreed King Crosspatch. "We have eaten a fine supper in a very few minutes and without any fuss of footmen or ladies-in-waiting either." He found a briarwood pipe and began to doze peacefully in deep contentment. Queen Grumpy knitted busily until the logs burned low, when she began to nod and doze also. Then they both went to bed.

But the beds in the snug little cottage were not of the excellent quality of its cold roasted fowls and new butter and jam. The mattresses were rough affairs. They were stuffed here with corn husks and there with straw and yet again with goose feathers, which pricked Queen Grumpy and King Crosspatch like so many pins. On these rough husky beds the royal old couple tossed restlessly until morning. They vowed they did not sleep a wink. (Perhaps they had eaten too much blackberry pie and ginger cake; what do you think about it?) When it was daylight at last, King Crosspatch clapped his hands to call his servants to attend.

"Ah, my dear!" said Queen Grumpy, "have you forgotten that we are no longer royal folk but simple cottagers instead?"

"Indeed, I had quite forgotten all about it," replied King Crosspatch. "Well, I am glad we are," and he began to dress.

Together they set about making breakfast; but again the breakfast proved a different matter from supper. You will remember that they had eaten everything in the cupboard and larder the night before. There was no milk, for they had forgotten to milk the cow, and neither were there eggs. They had neglected to search the nests. Moreover, the wood box was empty, and the fire was out.

"Now do you go out and chop some wood for the fire, my dear," said Queen Grumpy. "I shall milk the cow. I have always liked to look at pictures of milkmaids." She took the pail on her arm and went in search of the three-legged stool. Then she seated herself beside Bossy-Cow and began to milk. But sad to tell, Bossy-Cow, who herself was rather disagreeable, waited until the pail was nearly filled, and then she gave a sudden kick. Such a vicious kick it was, too! It upset the milk-pail, three-legged stool, Queen Grumpy and all, and frightened the poor old queen half out of her wits. She began to scream so loudly that she quite frightened King Crosspatch, and the hatchet slipped and chopped a bit of his little finger.

"Oh! Oh! Oh!" wailed King Crosspatch at the very top of his voice. "I think this hatchet is bewitched! Oh! Oh! Oh!" he wept, holding up his little finger. (It was not much of a cut; just a little scratch; but he was a great crosspatch, you know.) "Oh, what shall I do? What shall I do?" he wailed. "With this terrible cut on my little finger, I can't do anything at all!"

"There now, there now," petted Queen Grumpy soothingly. "Don't chop any more wood. There are still a few drops of milk left in my pail, and we shall drink that and eat bread for our breakfast." She led her weeping husband within the snug little cottage, but when she looked in the oven she found another disappointment. Queen Grumpy had forgotten to take the loaves out of the oven the night before, and they were burned to a crisp.

"Oh, this plagued cottage!" exclaimed Queen Grumpy, thoroughly vexed. "Everything goes wrong here. I wish I were back in my own palace once more! I would never sigh again to leave it."

"Neither would I," agreed King Crosspatch, drying his tears suddenly. "Let's go back!"

They made up their minds in an instant, and slamming the door of the snug little cottage, they began to climb the steep hill to their splendid palace. Every step of the way they were in a perfect torment of fear lest the old man and the old woman would refuse to change places again.

"That old woman will never want to give me my trailing velvet robes," said Queen Grumpy, as they sat to rest on the stone stile.

"And I have been thinking that the old man will fight to keep my diamond crown," said King Crosspatch anxiously. But at that very minute they heard voices, and behold! around the turn in the road came the old man and old woman, hurrying as though an army were after them. The old man was thumping his stick, and the old woman was making angry gestures with her hands; and both the old man and the old woman looked very cross and ill-humored.

"Ah, here you are!" exclaimed the old man, stopping short before the stone stile. "Now give me my hat and take back your hateful crown without any further nonsense! I could not sleep a wink last night, because it was so heavy on my head. Such a hateful palace too! I never saw the like! I could not smoke my briarwood pipe which I brought along for company, and this morning two villains were like to drown me in a pool before I was fully awake."

"They did not try to drown you," replied King Crosspatch haughtily. "That pool was a bath. Here is your hat; give me my crown."

"You may call it a bath or not, just as you choose," declared the old man warmly, "but let those two villains drown you instead of me, is what I say! I was never so disappointed in all my life as I was with your palace. The royal throne was hard as stone; the royal beds were soft as dough; everything was wrong."

Meanwhile Queen Grumpy and the old woman were having a time of it.

"Your cow has no manners," complained Queen Grumpy. "She kicked me, and she spilled the milk. I should behead her if she were mine."

"Would you, indeed?" asked the old woman scornfully, "and drink water and eat bread without butter all the rest of your life, I suppose? Let me tell you, Your Royal Highness, that your servants are lazy and good-for-nothing! I saw dust on the tops of all the doors and windows, and the silver flagon was not polished as brightly as my old pewter pots. Your royal cooks make griddlecakes heavy as lead; you had best behead them instead of my good Bossy-Cow." Then she added, "Did you feed my bird and give him water?"

"I could hardly feed myself in that awkward cottage of yours!" retorted Queen Grumpy.

"Oh, my poor bird!" exclaimed the old woman. "Here, hurry and give me back my own dress that I may loop it above my red flannel petticoat and be comfortable once more. I suppose you took the bread out of the oven in time—did you?"

"I forgot it, and it burned," sulkily replied Queen Grumpy, buttoning herself into her trailing velvet robes.

"Oh, what stupid folk are kings and queens!" cried the old woman in a passion. "Come along, husband," she called, and down the hill they went.

"And what stupid folk are cottagers!" called King Crosspatch after them. "Come along, wife," said he, and up the hill they went.

And so these four old folk again went on their separate ways. All four were sure that they were walking on the road to happiness at last, and so all were very jolly and smiling in consequence.

sang the old man and his old wife, as they went trudging down to the little cottage so snug.

sang Queen Grumpy and King Crosspatch, as they went climbing to their splendid palace on the top of a high hill; and there we will bid them all adieu!

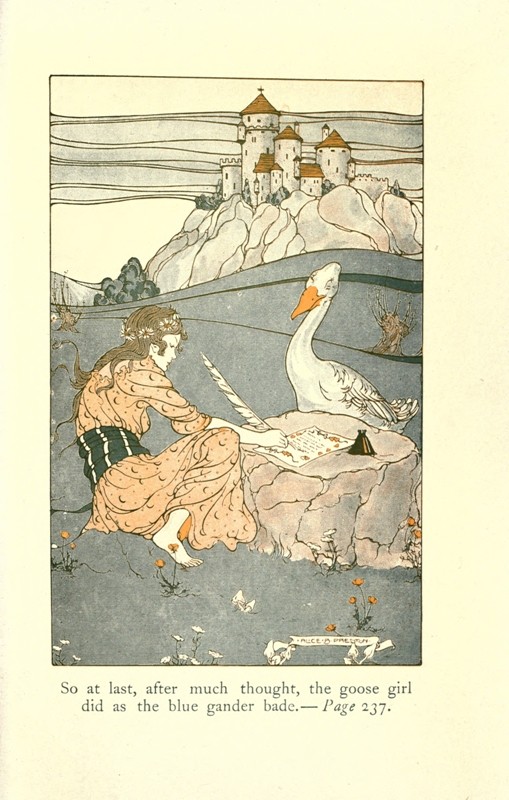

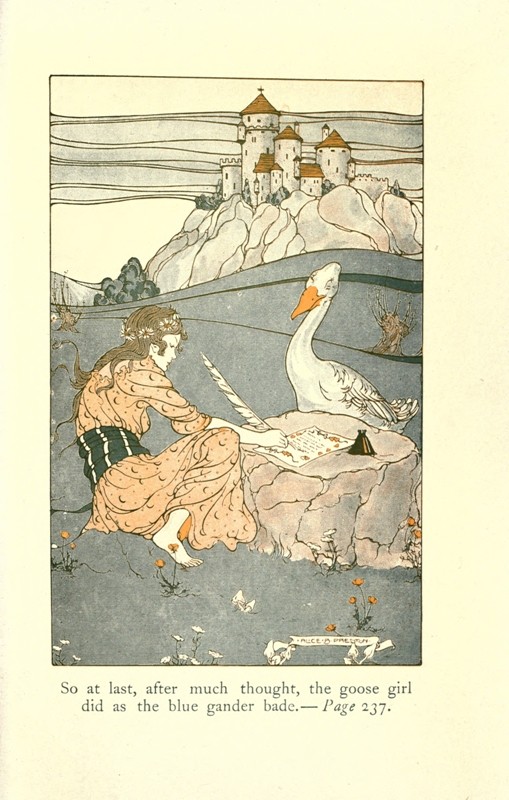

Once upon a time there was a goose girl who tended her flock in a green meadow. The meadow was dotted with forget-me-nots and yellow buttercups, and the sun shone down on it; her geese were fine blue geese and uncommonly knowing. She should have been the happiest goose girl in all the world, but she was not. She thought not of the beautiful meadow nor of her geese that were a pleasure to tend, for they were so wise and always did her bidding; but instead this goose girl wept every day because she longed to marry a certain lord who lived in a gray stone castle at the top of a high hill. All day long she sat looking at this castle, and her eyes could see nothing else for admiration of it. She dreamed dreams a hundred times a day, in which she married the lord, and was cross with her geese because she had to tend them.

Now when the lord of the castle went riding by the green meadow, this silly goose girl would run after the carriage, shouting his name and throwing bouquets of wild flowers to him. But alas! The carriage always whirled by so quickly that the lord heard her not, and the bouquets of wild flowers fell in the dust by the roadside. Each time the goose girl wept and threw sticks at her geese because she had been disappointed, until they fled to shelter.

"It is the stupid coachman's fault," said the goose girl to herself one day, after she had chased the carriage for a long distance. "My lord is within, of course, and cannot hear me, for the windows of glass shut out all sound." She knew that maidens often wrote letters when they were unable to obtain speech with those whom they fancied, and she resolved to write to the lord of the gray stone castle.

She spent her year's earnings on some pink paper with red hearts lovingly entwined on the border, and that her letter might be colorful and splendid, she bought also some purple ink. Then the goose girl sat before a flat rock and strove to compose such a letter to the lord that he would stop his carriage the next time he rode by the meadow.

"The first day he will ask me to ride with him, and the second day he will ask me to wed him," thought the goose girl, as she sat gazing at the gray stone castle. "The third day I shall ride with him a bride to yonder castle, where I shall dwell forevermore and have naught to do with geese but to eat them roasted!"

Her geese, thinking perhaps she had spread on the rock something fine to eat, crowded about her, but she drove them off. They bothered her, and she wished to give her mind to the letter. One large blue gander remained near, in spite of her angry motions and cross words. The goose girl was about to begin her letter when she remembered that she had brought no pen.

"Ah me! What shall I do?" she cried. "I shall have no more earnings for another year, and by that time my lord may be wed to some fair maiden, and I will surely die of a broken heart!" She covered her face and wept aloud at her misfortune. Suddenly she began to laugh instead.

"Oh, that I should be so foolish!" she exclaimed. "Here waiting my hand I have a hundred pens." She seized the large blue gander and plucked a fine quill from under his wing, but no sooner had she done so than the bird began to speak.

"That is not right," declared the gander. "You have taken what belongs not to you but to me. Put back my quill, or I shall be vexed."

"And who is there to care?" replied the goose girl rudely. "When I have written a letter to my lord of the gray stone castle, you shall have your quill and not before."

She began to speak her thoughts aloud, as goose girls often do, and started once more to compose the letter. "To my dearest lord of the gray stone castle, whom I love with all my heart, but who whirls past me as I sit tending geese in the meadow," she planned to write, and dipped the quill in the purple ink. To her dismay the pen wrote not at all as she planned, but seemed possessed of a spirit to go of itself. It wrote with a remarkable flourish:

"Dear gander!"

But the goose girl pulled it from the paper before it could write more.

"What manner of pen is this?" she cried in vexation.

"It is not your quill," said the blue gander. "I am its master, and it will write letters to none but me."

"Well, upon my word!" declared the goose girl. "You are the most forward creature I have yet seen, and this is what you will get." She took a long branch and beat the gander until he hid from sight in the bushes. Then again she strove to write her letter, but again the pen was possessed of a spirit of mischief.

"Oh! Oh!" wept the goose girl, "I have spent all my earnings on splendid pink paper with red hearts lovingly entwined on the border, and purple ink I bought also that my letter might be fine as a valentine. But, alas! I am bothered with a stubborn quill that will not write as I think. If I write not my letter to my lord, he will never know of me. Then he will never marry me, and I shall dwell forever in my wretched hut instead of the gray stone castle, as I have desired."

"You weep because you cannot marry the lord who lives in yonder gray stone castle," said the blue gander, poking his long neck from the bushes where he had fled. "Let me give you some advice. A wretched hut is not a pleasant place, 'tis true, but your manners suit it better than the castle of your dreams."

"Hold your tongue, forward bird!" screamed the goose girl in anger. She seized a clod of earth and hurled it with such force that had it struck the gander, he would have fallen flat in his tracks; but luck was with him, and he dodged.

The next day and the next day after that the goose girl sat down to write before the flat rock in the meadow; but the quill was stubborn as ever. She spoiled all but one sheet of the precious pink paper. Then once more the blue gander spoke to the goose girl.

So at last, after much thought,

the goose girl did as the blue gander bade.—Page 237.

So at last, after much thought,

the goose girl did as the blue gander bade.—Page 237.

"You have spoiled many sheets of your precious pink paper," said the gander, nodding his head and cocking his eye in the wisest sort of way. "Why will you not let the quill write a letter to me,—if only to see what will happen?"

"But then I shall have no more paper on which to write to my lord, and I shall dwell forever in my wretched hut instead of the castle of my dreams," answered the goose girl.

"Mayhap there might be a betwixt and between," remarked the gander sagely. "Write the letter and hand it to me with a bow."

So at last, after much thought, the goose girl did as the blue gander bade. She dipped the quill in the purple ink, and immediately it touched the paper it began to write such a marvelous letter as never before was seen or read! It called the blue gander all manner of tender names and vowed he was handsome and knowing. At the end, this remarkable quill wrote the goose girl's name with a flourish so fine that she was pleased in spite of herself. She folded the letter and handed it to the gander with a bow.

No sooner had she done this than the blue gander spread his wings and flew away in the clouds, and in his place stood a handsome shepherd lad dressed in blue corduroys. He had a hundred sheep in the fold that followed him, and in his hand a bag of silver.

"Dearest Goose Girl, wilt be mine?" asked he. "Yonder is my cottage, where I am sure we shall be very happy."

The goose girl was amazed at the change. But so handsome was this young shepherd lad, and so winning of speech and manner, that all thoughts of the gray stone castle and the lord tumbled out of her head. She gazed with delight at the little cottage to which the shepherd lad pointed. Blue smoke was curling from its chimney, and a bluebird was singing in a cage beside the kitchen door.

"We shall be married at once, shepherd lad of my heart," she answered him sweetly, "and I shall make you griddlecakes for your supper."

So the goose girl and the shepherd were married and went to live in the little cottage. Indeed, for all that I know, there they may be living to this day, for I have met no one who has ever told me of the death of either.

Once upon a time, there lived at the top of a very tall tree a little magic sprite. Now this magic sprite was called the Little Brown Man, and the tree was called the Tall Pine Tree. The Little Brown Man was so very small that had you ever seen him skipping and hopping about in his tree, you would have thought him some lively little brown squirrel. The Little Brown Man was always busy as a bee and twice as cheerful. He spent his days sweeping away the withered pine needles so that fresh new green needles might grow. With his cunning hands and powers of magic he mended broken places in the bark with healing herbs. At night the Little Brown Man rested from his labors. He curled himself up in the topmost boughs of the Tall Pine Tree, and the tree would rock him gently and sing him songs about the sea.

Thus the Little Brown Man, scarce bigger than my hand, and the Tall Pine Tree so high lived on in peace and happiness until an evil time befell them. It happened on a black winter's night, when the Storm Wind in a rage went crashing through the forest. Lashing the heavy branches of the tallest trees, he tore them loose and flung them to the ground as though they had been but so many twigs. Uprooting tiny trees and saplings by the score, the Storm Wind tore his way along until he reached the Tall Pine Tree. There he saw the Little Brown Man asleep in its topmost boughs.

"Ha, Little Brown Man!" laughed the Storm Wind wickedly. "At last I've caught you unaware, and I will do you mischief!" So saying, he blew a furious blast and flung the Little Brown Man to the ground beneath. Then, in a wailing voice, the Storm Wind wove a spell of deep enchantment round the Little Brown Man, singing thus:

And then the Storm Wind blew away.

For a long time, the Little Brown Man lay still as one dead, for the fall had hurt him cruelly. The Tall Pine Tree wept bitterly at the little sprite's misfortune, and by and by its tears, falling like rain, wakened the Little Brown Man. But alas! The Storm Wind's wicked spell had changed him, and the Little Brown Man with flaming eye and clawlike hand was very fierce and terrible to look upon.

"Oh, tell me, my Pine Tree!" cried the Little Brown Man in dismay, "how am I changed thus? My hands are hands no longer, but claws like those of wild beasts; my eye flames redder than the wicked wolf's! I cannot hop or skip; indeed, I scarce can hobble, so bent and twisted have I grown."

"Alas, my Little Brown Man!" the Tall Pine Tree replied. "While you did sleep, the Storm Wind tore you from my topmost bough, and wove this wicked spell around you. Until some child will speak to you a kindly word, you must remain thus bound by this evil spell."

In spite of his twisted back, the Little Brown Man tried again and again to climb into the Tall Pine Tree, but all his efforts were in vain. Wearied and tired out at last, he made himself a nest among the withered pine needles and began to wait for the magic word to break the Storm Wind's evil spell.

At last the winter passed. The snow began to melt; the brook, freed of its coat of ice, began to sing and chatter as it splashed along; the birds built nests; the sun shone down; the pussy willows, gray and brown, began to bud and bloom. Then boys and girls came out to play beneath the trees and gather buttercups and bluebells. The Little Brown Man's heart rejoiced, for he was sure the evil spell that bound him soon would end. Whenever happy children played beside the Tall Pine Tree, he would hobble toward them, saying:

"Good day to you! Good day to you, my children!"

But alas! The boys and girls were frightened of his clawlike hands and flaming eye, and so they screamed and ran away. Thus springtime went, and summer followed after; the maple leaves flamed red and gold in autumn, and winter came again to wrap the forest in its cloak of snowy white. Still the magic words to break the Storm Wind's spell remained unspoken. Thus years and years rolled on. In winter now the Storm Wind tore the branches of the Tall Pine Tree and flung them to the ground. The Little Brown Man, with his cunning hands and powers of magic, could no longer bind them fast. The Tall Pine Tree, once so green, grew old and rusty looking, because the Little Brown Man could no longer sweep the withered needles from its boughs. The Little Brown Man, down upon the ground, was in despair. It seemed the wicked spell would never be broken. No children ever lingered near the Tall Pine Tree. Indeed, when once they passed that way, they never came again. They thought the Little Brown Man was a wicked pixie who would do them harm.

Then at last the Little Brown Man peered from his nest one bright morning and saw a little girl walking slowly toward the Tall Pine Tree. Little Nannie always walked very slowly, because she was quite lame, and leaned upon a crutch. Sometimes she paused to watch a bee or butterfly; sometimes she leaned against a tree to rest, and all the while the Little Brown Man watched her eagerly. At last she reached the Tall Pine Tree, and then he hobbled forward, saying:

"Good day to you! Good day to you, my child!"

His flaming eye and clawlike hand so startled Little Nannie that she dropped her crutch; but when she saw that the Little Brown Man was also very lame, she was sorry for him, and so she answered bravely:

"Good day to you, good sir! I hope your health is fine," and so the magic words were spoken.

The Little Brown Man could scarcely believe his ears and began to caper about and prance with glee. Then presto! In a twinkling vanished all his ugly features, his back grew straight, and he was once more kindly-eyed.

"Oh, Tall Pine Tree! Oh, Tall Pine Tree!" he cried in joy. "Behold now I am free to climb up to your topmost boughs once more!" But in his joy the Little Brown Man did not forget Little Nannie, who stood staring, wide-eyed, at the wonders she had seen.

"And now, my child!" cried he, "what can I do to serve you?"

"Oh, please, sir," answered Little Nannie timidly, "if you would give me my crutch, I would be most grateful. I am so lame that I cannot stoop to pick it up myself."

"Your crutch!" screamed the Little Brown Man in a passion of rage. "It is a wicked stick that holds you back when you would run and play, and so I treat it thus!" He seized the crutch and flung it in the brook, and there it floated swiftly in the current.

"Oh, Little Brown Man, what have you done!" wept Little Nannie. "Now I can never wander in the forest any more, but must sit always in my chair. I cannot walk without my crutch, and my mother is too poor to buy me another." She leaned against the Tall Pine Tree and sobbed aloud.

"Stop, stop, Little Nannie!" cried the Little Brown Man, "I meant you no harm, as you will see. Now tell me this: Is it your wish to walk always with a crutch? If so, say but a word, and I will bring it back again, for now my powers of magic are returned."

"Oh, Little Brown Man!" answered Little Nannie through her tears, "I do not wish to walk always with a crutch; indeed, I often weep because I wish to run and play like other boys and girls."

"Then try and see if your wish come true, Little Nannie," commanded the Little Brown Man.

Little Nannie took a step forward, and then another and another, and found her feet like wings. So, singing and laughing, she danced home through the forest, the happiest child in all the world. When she reached her gate, she cried out:

"Oh, Mother! Mother! Come quickly and see! I can run and play like other boys and girls! The Little Brown Man has granted my wish to me!"

"My child!" cried her mother in amazement, "this is the work of a good fairy without doubt! And what did you say to thank the Little Brown Man?"

"Oh, mother, I was so happy I forgot," replied Little Nannie, hanging her head.

"Then let us go in search of him at once," said her mother.

So hand in hand they sought the Little Brown Man, but though they called loud and long at the foot of the Tall Pine Tree, they could not find the Little Brown Man. For at the magic of a kindly word, he had flown to the topmost boughs, and there he dwelled for evermore.

Babette and Antone were the children of a very poor woodcutter. They lived in a little cottage on the side of a steep mountain, and the mountain looked upon a great forest. Now though their father toiled in this forest from dawn until dark, he could earn but little. Wood in that region was plentiful, and woodcutters were numerous. Their mother made fine laces which Antone carried to the market to sell; but in spite of all their efforts, the poor parents seldom could give their children more than bread and broth to eat. Often indeed the broth was lacking if the woodcutter found no hare in the traps he set. Babette and Antone, however, were happy little children and never thought of their poverty. But it worried the woodcutter that Antone was ten years old and had not yet gone to school. Antone's mother taught him to read and write, that the other boys and girls would not be too far beyond him, and Antone studied his lessons diligently. Often as he sat doing his sums on the hearthstone, with a bit of charcoal for a pencil, his mother would sigh sadly. Antone did not like his mother to be sad, and so he always laughed to cheer her.

"Never fear, Mother," he would say. "Soon I shall send myself to school. My vegetable patch does finely. Then, when I am a great scholar, you shall be poor no longer. My father shall have a team of oxen and you a fine satin gown; Babette shall have a dozen real dollies instead of the turnip dollies she now rocks in her dolly cradle."

"Ah, Antone, my son," his mother would answer with a sigh, "unless you make your fortune as a maker of toys, I fear you will have no fortune at all. Your fingers are as clever as a wizard's even now; and though you are past ten, we cannot spare you to go to school."

It was true, as she said. Antone made boats from bits of cedar wood, and when he had fitted them with sails you could not tell them from any that had come out of a shop. He carved a doll's cradle from a pine knot, and for a dolly painted the white face of a turnip until one would think it was the face of some fair maiden,—so blue were this turnip dolly's eyes and so pink her cheeks, her hair of golden corn silk fell in such waves and her robe of young cabbage leaves was so green and beautiful. Then as often as this turnip dolly faded and began to shrivel, Antone made another, which Babette declared was always more beautiful than the one before. Babette had never been to the village and therefore knew nothing of real dollies. She loved her turnip babies tenderly indeed; she always carried them in her arm when she went with Antone to meet their father and sang them little songs as she rocked them to sleep.

Now it happened one night in the season of Halloween that Antone sat carving jack-o'-lanterns to sell in the village. Babette, who was rocking her dolly to sleep, sat watching him. Being but six, she knew nothing about the fun which comes with Halloween, and so she listened round-eyed with wonder to Antone, who knew all things about jack-o'-lanterns. When she heard that boys and girls dressed like goblins and witches frolicked in the village streets, Babette made up her mind to frolic too.

"How fine it must be!" she cried, clapping her hands. "Halloween must be quite like Christmas!"

"Not quite so fine as Christmas, Babette," answered Antone, as he carved the teeth in the last jack-o'-lantern, "but Halloween is very fine nevertheless. It is comical to see the jack-o'-lanterns bobbing up and down with their faces grinning in the candle light. And on Halloween the boys and girls play pranks on their elders that they would be well switched for at any other time; but every one laughs and is gay on that night." Antone finished the jack-o'-lantern and piled it with a dozen more in his little cart. He would sell them all in the village when he took his vegetables to market the next day; no one else could carve such splendid pumpkin faces as Antone.

"Then let us go and play pranks in the village too, Antone," cried Babette. "Mother will make us goblin dresses, and there is still one great pumpkin in your garden for a jack-o'-lantern. Oh, what a frolic we shall have!"

"Babette!" exclaimed Antone in astonishment. "Wherever did you get such a notion? The frolic in the village is not for us. Mother has no time to make us goblin dresses, and if she did, she has no goods; besides, how should we find our way home through the forest?"

"You know the way through the forest, Antone," insisted Babette, "and if Mother cannot make us goblin dresses, we can go without. It will be dark and our jack-o'-lantern will be as fine as any. Do come," she begged, "I have never been to a Halloween frolic."

"Now, Babette, I tell you we cannot go to the village to-morrow night," answered Antone. "I could not find my way home through the forest after dark, and we would both be lost. Be a good girl and do not tease any more."

Antone spoke sternly, and Babette burst into tears. She was very fond of her own way, and when she could not have it, sometimes she was a very naughty little girl. She sobbed and wept so piteously that Antone found it hard to refuse her. However, he dared not go to the village at night, as he feared to lose his way in the forest. So Antone trotted Babette on his knee and whispered that he would buy her chocolate; but she only wept the harder.

"Now, Babette!" cried Antone at last, when Babette showed no signs of stopping, "I cannot take you to the village; but if you are a good girl and stop crying at once, I will make a little Halloween frolic just for you and me. Now promise me you will not cry any more."

Babette dried her eyes and promised. She wished a Halloween frolic, but whether she frolicked at home or in the village mattered not at all.

"Will we wear goblin dresses or ghost dresses, Antone?" she asked.

Antone puzzled a moment before he answered. "Oh, ghost dresses, I think," said he.

The next day Babette was very good. She helped Antone gather his vegetables for market, and when he returned sat beside him quietly while he carved the last pumpkin from his garden. When the jack-o'-lantern was finished, Antone lighted the candle just for one second so that she might see it grinning in the light. Babette clapped her hands; but he held up a warning finger. The Halloween frolic was to be a secret. After supper the children went to bed as usual, but instead of undressing, they pulled their white nightdresses over their heavy coats.

"They will do for ghost dresses," whispered Antone when all was still, and they crept softly out. In the moonlight the jack-o'-lantern was grinning broadly to greet them.

"Pumpkin is smiling at us," laughed Babette. She was very happy, for her frolic was about to begin.

Antone struck a match to light the candle, but there was no candle in the jack-o'-lantern.

"I put the candle in; I know I did," said he in surprise. He searched in the dark, and Babette stopped her laughing. Antone looked about, and there beneath the bench lay the remainder of his precious candle. It was chewed to bits, and the wick was in shreds.

"Oh, Babette!" cried he. "A wicked rat has stolen our candle, and I paid a whole penny for it too!"

"Oh, the bad rats!" cried Babette, bursting into tears. She stamped her foot and sent the jack-o'-lantern rolling off the bench. It struck the earth with a bump and dented its nose a trifle.

"Now, Babette, what a baby you are! See what you have done!" cried Antone. He stooped to pick up the pumpkin, but the pumpkin was too quick for him.

"Oh, no, you don't," laughed Pumpkin in a thick throaty sort of voice. "Babette smashed my nose a little, but that's no matter on a Halloween night. Good-by, boys and girls," he called airily and rolled swiftly down the hill.

"You come back here; you're my pumpkin," cried Antone and started after the runaway. Babette followed, weeping and crying aloud.

"Oh, my Halloween frolic! Oh, my Halloween frolic!" she mourned. "Now we have no jack-o'-lantern and no candle either."

"But just you wait until he rolls down into the vegetable garden," shouted Antone, as he chased the swiftly rolling pumpkin. "He'll have to stop at the hedge." He took his little sister's hand that she might run faster. Pumpkin rolled along just in front of them but always just out of their reach. When he reached the hedge, he gave a great leap and landed directly in the vegetable patch.

"Come on, you Turnips! Come on, you Carrots!" called Pumpkin, as he rolled along. At his words the Carrots and Turnips tore themselves from their beds and followed after him, shouting.

"Come on! Come on!" called Pumpkin, and Parsnips and Beets followed the Carrots and Turnips.

"Look at Antone following us," yelled Pumpkin, and all his vegetable followers turned and laughed in derision.

"Ordinary nights you may be master, Antone," cried they, "but not on Halloween. This is our night."

"Well, you wait until I catch you and then see how hard you'll laugh," called Antone angrily. To see his vegetable patch laid waste made him furious.

"But you'll wait until you catch us before you punish us, won't you, Antone?" they answered mockingly.

"Oh, it's Halloween! It's Halloween!" sang Pumpkin, turning handsprings as he rolled along, and the rest of the vegetables did cartwheels as they went careering after him. They looked like a dozen market stalls upset on the hillside, and poor Antone nearly wept when he thought of his loss. He followed them with determination. Antone was not a lad to give up easily.

"Follow me! Follow me!" sang Pumpkin, as he led the way to a tiny door that opened beneath the forest. Turnips and Carrots squeezed through, and Antone, fearing to be left behind, caught up Babette and ran faster. Just as he reached the little door, a rough Potato tried to slam it in his face. But Antone was too quick for him. He ran through and climbed down the hole into the underground forest. There he continued the chase, but the ground here was springy and elastic, and with each step Antone began to gain on the vegetables. Babette's fatigue left her, and she shook herself free of Antone's hand.

"We'll catch up to them," declared Antone as they ran along. Even as he spoke, Potato stubbed his toe, and Babette caught him. She held him firmly, although he squirmed and tried his best to get free.

"Help! Help!" bawled Potato, when he saw he was a prisoner. "Oh, Pumpkin, wait for me!" he cried. The tears streamed from every one of his eyes, and he looked truly sad. At his cries Pumpkin turned around, and all the vegetables followed their leader.

"Come now, Antone," began Pumpkin in a persuasive voice. "You might let us have one night off, you know. Halloween is our night." Somewhere on his run, Pumpkin had picked up two twigs, and on these he now balanced himself rather unsteadily and thrust his leaves in the place where his pockets would have been if he had had pockets. He looked so very jolly and his grin was so very broad that Antone was inclined to give up the prisoner; but just then he thought of the ruined vegetable garden and grew angry again.

"It is all very well for you to be polite, Pumpkin, and try to beg off your friend," said Antone, "but this is the very fellow that tried to slam the door in my face not two seconds ago."

"Oh, Antone," cried Potato, "that's wrong. It was three seconds ago as true as I live. I looked at my watch just as I was trying to pinch your nose in the underground door, and it's quite three seconds ago; maybe it's four."

"Oh, hush up!" cried Pumpkin. "That's no way to talk when you are trying to beg off. Let him off for my sake, Antone," he continued in a most winning voice. "You'd get everlastingly tired of being in bed yourself; you know you would. See if you wouldn't take the first chance to kick up your heels if you could get it."

"But, Pumpkin," replied Antone, "think of my vegetable garden; it is ruined. I was saving all my vegetable money to go to school, and now I cannot go for ever and ever so long. Besides, how could I know you got tired of being in a bed? You never spoke to me before."

"Well, I speak to you now," replied Pumpkin, "and as for your vegetable patch, we'll all make that up to you, won't we, boys?"

"We will! We will!" called the vegetables in chorus, and the Potato in Babette's little fist yelled the loudest of all.

"There, now, you see we mean no harm," declared Pumpkin, "so let Potato go. Then you can both join us in our Halloween frolic."

At the magic words "Halloween frolic," Babette put Potato down at once. She was bound to have her fun, and, after all, the vegetables seemed to be a jolly lot. So peace was made, and the children followed the bobbing Turnips and Onions. Then shouts were heard, and Pumpkin ordered a halt. Presently they were joined by a dozen or more Cabbages.

"You're nice ones!" panted the Cabbages. "There we sat in the storeroom waiting for you to call us, and the first thing we knew we saw you pelting off down the hill like mad things."

"My gracious!" said a very stout Cabbage, who was terribly out of breath, "I'll have to take off my outer leaves before I go another step. I feel as though I were boiled."

Antone recognized the Cabbages at once. "You are Father Minette's cabbages, are you not?" he inquired politely as they marched along.

"Why, if it isn't little Antone, the woodcutter's son!" exclaimed the very stout Cabbage. "Yes, we come from Minette's farm. Mother Minette saved us for pickle, but we fooled her and slipped out of the storeroom when she was not looking. Oh, we Cabbages are not so green as we look!" The Cabbages all laughed, and Antone was surprised to find that he laughed too.

As they went marching on, Pumpkin sang and danced in the lead, and Onions and Carrots echoed his hearty songs. Presently great black cats with shining yellow eyes stepped from behind the trees, and each cat was soon joined by its mistress, who was no other than a real witch in tall peaked hat and carrying a broomstick. The Cabbages, who were a friendly lot, introduced Antone and Babette to these witches, and the witches seemed pleased to meet the children.

"They do not seem to be wicked witches, do they, Antone?" whispered Babette.

"Oh, my dear," replied a witch who overheard, "we are not a bit wicked on Halloween, you know. Any other night, I would probably do you a mischief. It is my nature, you know." She reached in her bag and handed Babette a peppermint. Babette, who was very fond of peppermint, ate it up with all haste.

"You shouldn't do that, my dear," reproved the witch. "It is seldom witches give peppermints, and when they do the peppermints should be treasured. Here is another to keep for your pocket, and then you will never be without a peppermint when you want one." And she handed Babette another. Babette curtseyed so prettily that the witch was charmed and took her to ride on her broomstick.

It was the gayest company one ever could imagine, as they marched along. Every vegetable was singing a different Halloween song in a different key, and they all had voices that sang out of tune by nature. Babette, her little white nightdress flying in the breeze, was riding on the witch's broomstick and singing loudly as the rest. When they reached the dancing-floor it was lighted with millions and millions of glowworms, and an orchestra of ten thousand frogs hummed lively tunes in their throats. Pumpkin seized a handful of glowworms and put them in his head. Then with his features all aglow he cried out:

"Ready for the dance!"