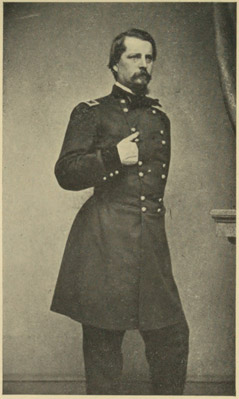

Winfield Scott Hancock

We expect to see coasting steamers make their regular trips to New Town, discharging freight and loading passengers on the wharf, safe from the dangers of rough weather, instead of lying off at sea, subjecting life and property to the perils of southeast gales and the breakers. The Senator even, in the opinion of experienced persons, might easily enter the channel on the easterly side of Dead Man's Island, and thence find a safe passage in the Creek. It will yet happen!

John M. Griffith came to Los Angeles in 1861, having four years previously married a sister of John J. Tomlinson. With the latter he formed a partnership in the passenger and freight-carrying business, their firm competing with Banning & Company until 1868, when Tomlinson died.

This same year, at the age of about eighteen, Eugene Meyer arrived. He first clerked for Solomon Lazard, in the retail dry-goods business; and in 1867 he was admitted into partnership. On November 20th of that year Meyer married Miss Harriet, the youngest daughter of Joseph Newmark—who officiated.

Felix Bachman, who came in 1853, was at various times in partnership with Philip Sichel (after whom Sichel Street is named, and Councilman in 1862), Samuel Laubheim and Ben Schloss, the firm being known as Bachman & Company; and on Los Angeles Street near Commercial they carried on the largest business in town. Bachman secured much Salt Lake trade and in 1861 opposed high freight rates; but although well off when he left here, he died a poor man in San Francisco, at the age of nearly one hundred years.

In 1861, Adolph Junge arrived and established a drug-store in the Temple Block, his only competitor being Theodore Wollweber; and there he continued for nearly twenty years, one of his prescription books, now in the County Museum, evidencing his activity. For a while, F. J. Gieze, the well-known druggist for so many years on North Main Street, and an arrival of '74, clerked for Junge. At the beginning of the sixties, Dr. A. B. Hayward practiced medicine here, his office being next to Workman Brothers' saddlery, on Main Street. Wollweber's name recalls a practical joke of the late sixties, when some waggish friend raised the cry that there was a bear across the river, and induced my Teutonic neighbor to go in hot pursuit. After bracing himself for the supreme effort, Wollweber shot the beast dead; only to learn that the bear, a blind and feeble animal, was a favorite pet, and that it would take just twenty-five dollars to placate the irate owner!

The absence in general of shade trees was so noticeable that when John Temple, on January 31st, planted a row facing Temple Building there was the usual town gossip. Charley Ducommon followed Temple's example. Previously, there had been several wide-spreading trees in front of the Bella Union hotel, and it came to pass within the next five years that many pepper-trees adorned the streets.

In 1861, the Post Office was removed from North Spring Street to a frame building on Main Street, opposite Commercial. About the same time when, owing to floods, no mail arrived for three or four weeks and someone facetiously hung out a sign announcing the office "To Let!" the Washington postal authorities began issuing stamped envelopes, of the values of twelve and twenty-four cents, for those business men of Los Angeles and the Pacific Coast who were likely to use the recently-developed Pony Express.

Matthew Keller, or Don Mateo, as he was called, who died in 1881, was a quaint personality of real ability, who had a shop on the northwest corner of Los Angeles and Commercial streets, and owned the adjoining store in which P. Beaudry had been in business. His operations were original and his advertising unique, as will be seen from his announcement in the Star in February:

M. Keller, to His Customers

You are hereby notified that the time has at last arrived when you must pay up, without further delay, or I shall be obliged to invoke the aid of the law and the lawyers.

Your most ob't servant,

M. Keller.

Which warning was followed, in the next issue, by this:

M. Keller, to His Customers

The Right of Secession Admitted!

You are hereby notified that the time has arrived when you must pay up, without further delay, or I shall be obliged to invoke the aid of the law and the lawyers.

After such settlement, slow-payers are requested to secede.

M. Keller.

(to be augmented next week)

This later advertisement, with the line in parenthesis, continued to be printed, week after week, without change, for at least twelve months.

The following year, Keller, in flaring headlines, offered for sale the front of his Los Angeles vineyard, facing on Aliso Street, in building lots of twenty by one hundred feet, saying, in his prospectus:

Great improvements are on the tapis in this quarter. Governor Downey and the intrepid Beaudry propose to open a street to let the light of day shine in upon their dark domains. On the Equerry side of Aliso Street, "what fine legs your master has," must run to give way for more permanent fixtures. Further on, the Prior estates are about to be improved by the astute and far-seeing Templito; and Keller sells lots on the sunny side of Aliso Street. The map is on view at my office; come in and make your selections,—first come, first served! Terms will be made handy!

M. Keller.

Nathaniel Pryor—sometimes known as Don Miguel N. Pryor or Prior—is the pioneer referred to by Keller. At the age of thirty, it is said, in 1828, he came here, and fifteen or twenty years later, about the time that he was a Regidor or Councilman, was one of eight or ten Easterners who had farms within the pueblo district. His property, in part a vineyard, included what is now Commercial to First streets and possibly from Los Angeles Street to the river; on it was an adobe which is still standing on Jackson Street, and is the only mud-brick structure in that section. For a while, and probably because he had loaned Pryor some money, F. P. F. Temple had an interest in the estate. Pryor was twice married, having a son, Charles, by his first wife, and a son, Nathaniel, Jr., by his second. Pablo Pryor of San Juan was another son. The first Mrs. Pryor died about 1840, and is one of the few—with the mother of Pio Pico—buried inside of the old church at the Plaza. The second Mrs. Pryor, who inherited the property, died about 1857. A granddaughter, Mrs. Lottie Pryor, is a surviving member of this family.

During the administration of Padre Blas Raho, a genial, broad-minded Italian, several attempts were made, beginning with 1857 or 1858, to improve the old church at the Plaza; and in 1861, the historic edifice, so long unchanged, was practically rebuilt. The front adobe wall, which had become damaged by rains, was taken down and reconstructed of brick; some alterations were made in the tower; and the interesting old tiled roof was replaced—to the intense regret of later and more appreciative generations—with modern, less durable shingles. A fence was provided, and trees, bushes and plants were set out. The church was also frescoed, inside and out, by Henri Penelon, the French pioneer artist and photographer, who painted upon the wall the following inscription:

Los Fieles de Esta Parroquia á la Reina de los Angeles, 1861.[23]

Early in March, Sanchez Street was opened by the Common Council. It was opposite the northern section of Arcadia Block, passed through the properties of Sanchez, Pico, Coronel and others, and terminated at the Plaza.

The Los Angeles Mounted Rifles, part of the five thousand militia wanted by California, was organized on March 6th at a meeting in the Court House presided over by George W. Gift, with M. J. Newmark, who became an officer in the company, as Secretary.

Late in March, John Fröhling rented from the City Fathers a space under the Temple Market building for a wine cellar; and in December, 1860, at the close of his vintage, when he had conducted a hearty harvest-home celebration, he filled the vault with pipes and other casks containing twenty thousand or more gallons of native wines. In a corner, a bar was speedily built; and by many Angeleños that day not associated with at least one pilgrimage to Fröhling's cool and rather obscure recesses was considered incomplete.

Few who witnessed the momentous events of 1861 will forget the fever-heat of the nation. The startling news of the attack on Fort Sumter took twelve days by Pony Express to reach the Coast, the overland telegraph not being completed until six months later; but when, on the twenty-fourth of April, the last messenger in the relay of riders dashed into San Francisco with the story, an excited population was soon seething about the streets. San Francisco instantly flashed the details south, awakening here much the same mingled feelings of elation and sorrow.

When the war thus broke out, Albert Sidney Johnston, a fellow-townsman who had married a sister of Dr. J. S. Griffin, and who, in 1857, had successfully placed Utah under Federal control, resigned from his command as head of the Department of the Pacific—General Edwin V. Sumner succeeding him—and, being a Southerner, left for the South, by way of Warner's Ranch and the Overland Route, with about a hundred companions, most of whom were intercepted at Fort Yuma through the orders of Captain W. S. Hancock. According to Senator Cornelius Cole, Sumner arrived at Johnston's headquarters in San Francisco after dark; and in spite of Johnston's protest, insisted on assuming command at once. Johnston took up arms for the Confederacy, and was made a Brigadier-General; but at Shiloh he was killed, the news of his death causing here the sincerest regret. I shall speak of the loss of one of General Johnston's sons in the disaster to the Ada Hancock; another son, William Preston, became President of Tulane University.

Others of our more enthusiastic Southerners, such as Cameron E. Thom and J. Lancaster Brent, also joined the Rebellion and proceeded to the seat of war. Thom, who has since attained much distinction, returned to Los Angeles, where he is still living[24]. Brent never came back here, having settled near New Orleans; and there I again met him, while I was attending the Exposition. He had fought through the War, becoming a General before its close; and he told me that he had been arrested by Federal officers while on his way to the South from Los Angeles, but had made his escape.

Among the very few who went to the front on the Union side and returned here was Charles Meyrs Jenkins, already referred to as a city Zanjero. Owing to the possible need of troops here, as well as to the cost of transportation, volunteers from the Pacific slope were not called for and Jenkins joined an Eastern cavalry battalion organized in October, 1862. Even then, he and his comrades were compelled to pay their own way to the Atlantic seaboard, where they were incorporated into the Second Massachusetts Cavalry. Jenkins engaged in twenty battles, and for fifteen months was a prisoner of war confined at both Andersonville and Libby; suffering such terrible hardships that he was but one of three, out of a hundred and fifty of his battalion, who came out alive.

Not everyone possibly even among those familiar with the building of the Los Angeles & San Pedro Railroad, knows that an effort was made, as far back as 1861, to finance a railroad here. About the middle of February in that year, Murray Morrison and Abel Stearns, Assemblymen, learned of the willingness of Eastern capitalists to build such a road within eighteen months, providing the County would subscribe one hundred thousand dollars toward the undertaking, and the City fifty thousand. The Legislature therefore on May 17th, 1861, granted the franchise; but important as was the matter to our entire district, nothing further was done until 1863 to give life to the movement.

For almost a decade after I came here, St. Valentine's Day was seldom observed in Los Angeles; but about 1861 or 1862, the annual exchange of decorated cards, with their sentimental verses, came to be somewhat general.

Phineas Banning was a staunch Republican and an ardent Abolitionist; and it was not extraordinary that on May 25th, at a grand Union demonstration in Los Angeles, he should have been selected to present to the Union Club, in his characteristically vigorous manner, an American flag made for the occasion. Columbus Sims, as President, accepted the emblem, after which there was a procession, led by the First Dragoons' band, many participants being on horseback. In those days such a procession had done its duty when it tramped along Main Street and around the Plaza and back, by way of Spring Street, as far as First; and everyone was in the right frame of mind to hear and enjoy the patriotic speeches made by Captain Winfield Scott Hancock, General Ezra Drown and Major James Henry Carleton, while in the distance was fired a salute of thirty-four guns—one for each State in the Union.

Senator William McKendree Gwin was another man of prominence. Following his search for gold with the Forty-niners—due, he used to say, to advice from John C. Calhoun, who, probably taking his cue from Dana's prophecy in Two Years Before the Mast, one day put his finger on the map and predicted that, should the bay now called San Francisco ever be possessed by Americans, a city rivaling New York would spring up on its shores—Gwin came to Los Angeles occasionally, and never forgot to visit me at my home. In 1861, he was arrested by the Federal Government for his known sympathy with the South, and was kept a prisoner for a couple of years; after which he went to France and there planned to carry through, under force of arms, the colonization of Sonora, Mexico, depending in vain on Napoleon III. and Maximilian for support. Notwithstanding this futile effort, Gwin became a leader in national Democratic councils, and was an intimate adviser of Samuel J. Tilden in his historic campaign.

Oscar Macy, son of Dr. Obed Macy, having as a newspaper man enthusiastically advocated the election of Frémont in 1856, was appointed, on Lincoln's inauguration, to the Collectorship of Customs at San Pedro; a post which he continued to fill even after the office had been reduced to an inspectorship, later resigning in favor of George C. Alexander. This recalls another appointment by Lincoln—that of Major António María Pico, a nephew of Pio Pico, to the Receivership of Public Moneys at Los Angeles. Pico lived at San José; and finding that his new duties exiled him from his family, he soon resigned the office.

Old-time barbers, as the reader may be aware, were often surgeons, and the arrival in Commercial Street, in the early sixties, of J. A. Meyer, "late of San Francisco," was announced in part as follows:

Gentlemen will be waited on and have Shaving, Hair-Dressing, and Shampooing prepared in the most luxurious manner, and in the finest style of the art; while Cupping, Bleeding, and Teeth-Extracting will also be attended to!

Fort Tejón had been pretty well broken up by June, when a good deal of the army property was moved to Los Angeles. Along with Uncle Sam's bag and baggage, came thirty or more of the camels previously mentioned, including half a dozen "young uns." For some months they were corralled uncomfortably near the genial Quartermaster's Main Street office; but in October they were removed to a yard fixed up for them on D. Anderson's premises, opposite the Second Street schoolhouse.

Starting with the cook brought to Los Angeles by Joseph Newmark, the Chinese population in 1861 had increased to twenty-one men and eight women—a few of them cooks and servants, but most of them working in five or six laundries. About the middle of June of that year, Chun Chick arrived from San Francisco and created a flurry, not merely in Chinatown, but throughout our little city, by his announcement that he would start a store here; and by the thirteenth of July, this pioneer Chinese shop, a veritable curiosity shop, was opened. The establishment was on Spring Street, opposite the Court House; and besides a general assortment of Chinese goods, there was a fine display of preserves and other articles hitherto not obtainable in town. Chun Chick was clever in his appeals of "A Chinese Merchant to the Public;" but he nevertheless joined the celebrities advertised for delinquent taxes. Chun Chick—or, as he appeared on the tax collector's list, Chick Chun—was down for five hundred dollars in merchandise, with one dollar and twenty-five cents for City, and the same amount for school taxes. Sing Hop, Ching Hop and Ah Hong were other Chinamen whose memory failed at the critical tax time of that year.

For years, until wharves made possible for thousands the pleasures of rod and reel, clams, since used for bait, were almost a drug on the market, being hawked about the streets in 1861 at a dollar a bucket—a price not very remunerative considering that they came from as far north as San Buenaventura.

When the Civil War began, California and the neighboring territory showed such pronounced Southern sympathies that the National Government kept both under close surveillance, for a time stationing Major, afterward General James Henry Carleton—in 1862 sent across the Colorado River when the Government drove out the Texans—with a force at Camp Latham, near Ballona, and dispatching another force to Drum Barracks, near Wilmington. The Government also established a thorough system of espionage over the entire Southwest. In Los Angeles and vicinity, many people, some of whom I mention elsewhere, were arrested; among them being Henry Schaeffer who was taken to Wilmington Barracks but through influential friends was released after a few days. On account of the known political views of their proprietors, some of the hotels also were placed under watch for a while; but beyond the wrath of the innkeepers at the sentinels pacing up and down their verandas, nothing more serious transpired. Men on both sides grew hot-headed and abused one another roundly, but few bones were broken and little blood was shed. A policy of leniency was adopted by the authorities, and sooner or later persons arrested for political offenses were discharged.

The ominous tidings from beyond the Colorado, and their effect, presaging somewhat the great internecine conflict, recalls an unpublished anecdote of Winfield Scott Hancock, who was a graduate of West Point, an intense patriot and a "natural born" fighter. One day in 1861, coincident with the Texan invasion, and while I was visiting him in his office on Main Street near Third (after he had removed from the upstairs rooms adjoining the Odd Fellows' Hall in the Temple Building), John Goller dropped in with the rumor that conspirators, in what was soon to become Arizona, were about to seize the Government stores. Hancock was much wrought up when he heard the report, and declared, with angry vehemence, that he would "treat the whole damned lot of them as common thieves!" In the light of this demonstration and his subsequent part as a national character of great renown, Hancock's speech at the Fourth of July celebration, in 1861, when the patriotic Angeleños assembled at the Plaza and marched to the shady grove of Don Luis Sainsevain, is worthy of special note. Hancock made a sound argument for the preservation of the Union, and was heartily applauded; and a few days afterward one of the local newspapers, in paying him a deserved tribute, almost breathed an augury in saying:

Captain Hancock's loyalty to the Stars and Stripes has never for a moment been doubted, and we hope he may be advanced in rank and honors, and live to a green old age, to see the glorious banner of our country yet waving in peaceful glory over a united, prosperous, and happy people.

Few of us, however, who heard Hancock speak on that occasion, dreamed to what high position he would eventually attain.

Soon after this episode, that is, in the early part of August, 1861, Hancock left for the front, in company with his wife; and taking with him his military band, he departed from San Pedro on the steamer Senator. Some of my readers may know that Mrs. Hancock—after whom the ill-fated Ada Hancock was named—was a Southern woman, and though very devoted to her husband, had certain natural sympathies for the South; but none, I dare say, will have heard how she perpetrated an amusing joke upon him on their way north. When once out upon the briny deep, she induced the musicians to play Dixie, to the great amusement of the passengers. Like many Southerners, Mrs. Hancock was an Episcopalian and frequently contributed her unusual musical talent to the service of the choir of St. Athanasius Church, the little edifice for a while at the foot of Pound Cake Hill—first the location of the Los Angeles High School and now of the County Courthouse—and the forerunner of the Episcopal Pro-Cathedral, on Olive Street opposite Central Park.

Having in mind the sojourn in Los Angeles for years of these representative Americans, the following editorial from the Los Angeles Star on the departure of the future General and Presidential nominee, seems to me now of more than passing significance:

While resident here, Captain Hancock took great interest in our citizens, the development of our resources, and the welfare of this section of the country; and as a public-spirited, enterprising gentleman, he will be missed from among us, and his most estimable lady will long live in the hearts of her many friends. We desire their prosperity, happiness, and long life, wherever their lot may be cast.

The establishing of Drum Barracks and Camp Drum at Wilmington was a great contribution to the making of that town, for the Government not only spent over a million dollars in buildings and works there, and constantly drew on the town for at least part of its supplies, but provisions of all kinds were sent through Wilmington to troops in Southern California, Utah, Yuma, Tucson and vicinity, and New Mexico.

P. H., popularly known as Major Downing, was employed by Banning for some time during the War to take charge of the great wagon-trains of Government supplies sent inland; and later he opened a general merchandise store in Wilmington, after which he transacted a large volume of business with H. Newmark & Company.

At the breaking out of the War, the Southern Overland Mail Route was discontinued and a contract was made with Butterfield for service along a more central course, by way of Great Salt Lake. There was then a stage six times a week; and a branch line ran to Denver, the terminus having been changed from St. Joseph to Omaha. Twenty days was the time allowed the company to get its stages through during eight months of the year, and twenty-three days for the more uncertain winter months. This contract was made for three years, and one million dollars a year was the compensation allowed the Butterfields. After the War, the old route was resumed.

J. De Barth Shorb came to Los Angeles at the commencement of the War, as Assistant Superintendent of the Philadelphia & California Oil Company; and in 1867 he bought the Temescal grant and began to mine upon the property. The same year he married a daughter of B. D. Wilson, establishing a relationship which brought him a partnership in the San Gabriel Wine Company, of which he eventually became manager. His position in this community, until he died in 1895, was important, the little town of Shorb testifying to one of his activities.

Not only were the followers of the indefatigable padres rather tardy in taking up the cultivation of olives, but the olive-oil industry hereabouts was a still later venture. As an illustration, even in 1861 somewhat less than five hundred gallons of olive oil was made in all Los Angeles County, and most of that was produced at the San Fernando Mission.

How important was the office of the Zanjero, may be gathered from the fact that in 1861 he was paid twelve hundred dollars a year, while the Mayor received only eight hundred dollars and the Treasurer two hundred dollars less than the Mayor. At the same time, the Marshal, owing to the hazardous duties of his office, received as much as the Mayor; the City Attorney one hundred dollars less than the Treasurer; and the Clerk but three hundred and fifty.

By 1861, there were serious doubts as to the future of cattle-raising in Southern California, but Banning & Company came forward proposing to slaughter at New San Pedro and contracted with John Temple, John Rains and others, to do their killing. For a while, the enterprise was encouraged; Temple alone having six hundred head so disposed of and sold.

In September, Columbus Sims, the popular attorney of unique personality who from 1856 to 1860 had been Clerk of the United States District Court, was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel in the United States Army and placed in charge of Camp Alert, at the Pioneer Race Course, San Francisco, where twelve companies were soon assembled; and a month or two later he was made Colonel in the Second Cavalry. Late in December of that year, however, he had an altercation with D. D. Colton, in San Francisco, when blows were exchanged and Sims drew "a deadly weapon." For this, the doughty Colonel was arrested and held to await the action of the Grand Jury; but I am under the impression that nothing very serious befell the belligerent Sims as a result.

On September 11th, H. Stassforth, after having bought out A. W. Schulze, announced a change in the control of the United States Hotel, inviting the public, at the same time, to a "free lunch," at half-past four o'clock the following Sunday. Stassforth was an odd, but interesting character, and stated in his advertisement that guests were at liberty, when they had partaken of the collation, to judge if he could "keep a hotel." Whether successful or otherwise, Stassforth did not long continue in control, for in November, 1862, he disposed of the business to Webber & Haas, who in turn sold it to Louis Mesmer.

In the fall, an atrocious murder took place here, proving but the first in a series of vile deeds for which, eventually, the culprit paid with his own life at the hands of an infuriated populace. On Sunday evening, September 30th, some Frenchmen were assembled to sit up with the body of one of their recently-deceased countrymen; and at about eleven o'clock a quarrel arose between two of the watchers, A. M. G., or Michel Lachenais—a man once of good repute, who had cast some slurs at the French Benevolent Society—and Henry Delaval, a respected employee of the Aliso Mills who spiritedly defended the organization. Lachenais drew a weapon, approached Delaval and tried to shoot him; but the pistol missed fire. Thereupon Lachenais, enraged, walked toward a lamp, adjusted two other caps, and deliberately shot Delaval through the body. The next day his victim died. Lachenais made his escape and so eluded the authorities that it was not until the middle of February, 1866, that he surrendered himself to Deputy Sheriff Henderson. Then he was tried, but was acquitted.

About October, Remi Nadeau, a Canadian, after whom Nadeau Street is named and father of George A. Nadeau, came across the Plains to Los Angeles, having spent the previous winter, en route, in Salt Lake City; and for a while he teamed between here and Montana. Within the year, believing that San Francisco offered a larger field, he moved to that city and continued his operations there.

In the front part of a little building on Main Street, between Second and Third, Lorenzo Leck, whom I have already mentioned, conducted a grocery, living with his family in the rear. He was a plain, unassuming, honest Dane of the old school, who attended scrupulously to his business and devoted his Sundays and holidays to modest amusements. On such days, he would put his wife, Caroline, and their children on a little wagon that he owned and take them to his vineyard on the outskirts of the town; and there he would enjoy with them those rural pastimes to which he had been accustomed in the Fatherland, and which to many early-comers here were a source of rest and delight.

On the afternoon of Saturday, October 17th, Francisco Cota, a Mexican boy fifteen years of age, entered Leck's store while he was out, and, taking advantage of the fact that Frau Leck was alone, whipped out a knife, stabbed her to death, stole what cash was in sight and then escaped to a vineyard, where he hid himself. John W. Henderson, the son of A. J. Henderson, a Deputy Sheriff here still living in Los Angeles, came in soon after and finding Mrs. Leck horribly disfigured, he gave the alarm. Neighbors and friends at once started in pursuit and caught Cota; and having tied a rope around the murderer's neck during the excitement they dragged him down to Alameda Street, where I witnessed the uproar. As they proceeded by way of Aliso Street, the mob became more and more infuriated, so that before it reached the spot which had been selected for his execution, the boy had been repeatedly stabbed and was nearly dead. At length, he was strung up as a warning to other malefactors.

A short time after this melancholy event, I was driving with my wife to the Cerritos rancho and, missing our road, we stopped at a Mexican home to inquire the way. The woman who answered our summons proved to be one who knew, and was known by all Los Angeles merchants on account of her frequent excursions to town; she was, in fact, the mother of the Mexican boy who had been mobbed and hung for the murder of poor Leck's wife! The sight of Gringos kindled anew her maternal wrath; and she set up such a hue and cry as to preclude any further intelligible conversation.

California being so far removed from the seat of war did not awake to its full significance until the credit of the Government began to decline. Four weeks were required, it is well to remember, to complete the trip from New York to San Francisco via Panamá, and our knowledge of events in the East was far from perfect. Until the completion of the continental telegraph in October, 1861, the only immediate news that reached the Coast came privately and we were, therefore, pretty much in the dark until the arrival of Eastern papers, and even after that telegraphing was so expensive that our poorly-patronized little news-sheets could not afford the outlay. A few of us therefore made up a purse of one hundred dollars a month, which small sum enabled us to allay our anxiety at least in the case of very important happenings.

It must not be forgotten, though, that we then had a little relief from San Francisco, whose newspapers, containing some telegraphic despatches, arrived in town perhaps three to four days after their publication. I may add, in fact, that it was not until about the beginning of the eighties that Los Angeles dailies could afford the luxury of regular direct telegrams.

In other respects as well, editing a local newspaper during the War was apt to entail financial loss. The Los Angeles News, for instance, was outspoken for the Union and so escaped the temporary eclipse suffered by the Star through Government censorship; but the Unionists being in a decided minority in the community, pickings for the News were mighty poor. Perhaps this want of patronage suggested the advisability, in 1863 (when that paper was published by C. R. Conway and Alonzo Waite, on Main Street, opposite the express office), of reducing the subscription rate to five dollars a year.

Probably one of the most interesting visits to Los Angeles ever made by a well-known personage was the sudden call with which Lady Franklin, the wife of the eminent, lost Arctic explorer, honored our little town far back in 1861. The distinguished lady, accompanied by Mrs. Cracroft, her niece, Commodore and Madame Watkins and Collector and Mrs. Rankin, arrived at San Pedro on the Golden State during the first week in November and was driven, with her companions, to the Bella Union hotel, from which she made such short excursions about the city as were then possible; and as sympathy for her in her sorrow, and admiration for her long years of plucky though vain search for her husband were still general, every courtesy possible was afforded her. During Lady Franklin's stay Benjamin D. Wilson arranged a delightful garden party at his hospitable mansion at Lake Vineyard in her ladyship's honor, and Phineas Banning also entertained her with a reception and collation at his San Pedro home; and these receptions and collations were as enjoyable as they were notable. After a day or two, Lady Franklin and her party left on the Senator for San Francisco, being accorded, as the vessel weighed anchor, a marked ovation.

For many years funerals were attended by men on horseback and by women on foot, as hacks were unknown in early days; and while the good citizens were doubtless then conducted to their last resting-place in a manner just as satisfactory to themselves as are their descendants who are buried according to present-day customs, those who followed in the train were very seriously inconvenienced by the melancholy, dusty processions to the old and now-forgotten burial-grounds; for in those days the trip, in summer exceedingly hot and in winter through rain and mud, was a long, fatiguing one.

Speaking of funerals, a strange sight was witnessed in our streets about the end of November, 1861, attending the burial of a child. The father and mother, both native Californians, were seated in a wagon, in which was also placed the strikingly plain little coffin or box containing the dead. Beside the wagon walked an old man, playing a fiddle. Two or three persons followed in the deep mud; the whole forming a weird picture, said to be the relic of an almost obsolete back-woods custom.

Banning & Hinchman's Comet proving insufficient, the Gondolier was put on in the fall of 1861 and became a familiar craft in the conveying of passengers and freight between New San Pedro and the ships lying off the harbor.

Two years previous to the completion of the telegraph from San Francisco to Los Angeles—that is, in 1858—the first continental telegraph was undertaken; and by October, 1861, Governor Downey of California sent a congratulatory message to President Lincoln. On November 7th, the line was open to the public. Several months before, all the companies in the State had consolidated into the California State Telegraph Company. Banning & Hinchman having succeeded, for a short season, Phineas Banning, the sub-contractor for the building of the first telegraph, they made an effort, following the establishment of communication between the Atlantic and the Pacific, to secure a line to New San Pedro; and at the end of October, 1861, the first telegraph pole in the long row from Los Angeles to the harbor was formally set. About the middle of November, this line was completed; and though it was widely proclaimed as "working like a charm," the apparatus soon got out of order and by the following January there were many complaints that both poles and wire had fallen to the ground, blocking the thoroughfares and entangling animals in such a way as to become a nuisance. Indeed, there was soon a public demand either to repair the telegraph or to remove it altogether and throw the equipment away. Soon after the first of February, 1862, the line was working again; but by that time the telegraph to San Francisco had gotten out of order! And so great were the difficulties in repairing that line, that Los Angeles was not again talking uninterruptedly over the wire with its neighbor until July.

On November 15th, the first number of El Amigo del Pueblo, printed in Spanish, appeared from the shop of José E. Gonzales & Company; but native support being withheld, "The Friend of the People" starved to death in the following May.

Whaling, like shark-hunting, continued brisk in 1861 and 1862, and many vessels were fitted out at San Pedro; Los Angeles merchants selling them most of their supplies. The sea-monsters usually moved up the coast about the first of the year, the males keeping in toward the shore going up, and the females hugging the coast, coming down; and small boats such as Captain W. Clark's Ocean, used to take from four hundred and fifty to five hundred barrels of oil in five or six weeks. For six days, in March, 1862, San Pedro whalers harpooned a whale a day, bringing to the landing over two hundred barrels of oil as a result of the week's labor.

The bitter fight between Abolitionists and Southern sympathizers was immediately reflected in the public schools. Defenders of the Union worked for a formal oath of allegiance to the National Government, as a preliminary to granting teachers' certificates; while the Confederates, incensed at what they deemed a violation of personal rights, assailed the institutions. The result was that attendance at the public schools gradually fell off until, in the winter of 1865-66, only about three hundred and fifty children of school age were being instructed by public teachers; another third of a thousand was in private schools, while some three hundred and sixty-nine were not on any roster.

The gloom naturally caused by the outbreak of war was sometimes penetrated by the brightness of social life, and among the happier occasions of the winter of 1861 was the marriage, on December 23d, in the presence of a large circle of friends, of Tom D. Mott to Ascención, daughter of Don José Andrés and Doña Francisca Ábila Sepúlveda.

The winter of 1861-62 recorded the greatest of all floods, especially in the North where, in December and January, something like thirty-five inches of rain was precipitated. In Los Angeles County the rivers soon rose and overflowed the lowlands; but the rise was gradual, causing the loss of but few or no lives and permitting the stock to reach the neighboring hills in safety. In Anaheim the water was four feet deep in the streets and people had to seek flight to the uplands or retreat to the roofs of their little houses. Vineyards were sometimes half-ruined with the layers of deep sand; banks of streams were lined for miles with driftwood; and ranchers saw many a clod of their farms carried off and deposited to enrich their neighbors, miles away. For a month it rained so steadily that the sun peeped out for scarcely an hour.

I witnessed this inundation in Los Angeles, where much damage was done to business buildings, especially to Mellus's Row, and saw merchants in water up to their waists, trying to save their goods. The wall of the room occupied by Sam Meyer fell first, whereupon Hellman & Brother became intensely interested in the removal of their stock, while poor Sam, knee-deep in water, sadly contemplated his losses. Before the Hellmans had made much headway, they observed a tendency on the part of their walls to crumble, and their exit was neither graceful nor delayed. After that the store occupied by Meyer & Breslauer caved in, smashing show cases and shelves, and ruining a large amount of merchandise. The ludicrous picture of this rush for "safety first" is not a fit reflection of the feelings of those pioneers who saw the results of years of labor obliterated in a moment. Friends and neighbors lent assistance to the unfortunate, and helped to save what they could. After this flood, Hellman & Brother and Sam Meyer removed to the Arcadia Block, while Meyer & Breslauer secured accommodations north of the Plaza Church.

On the first of January, 1862, after an experience of about five years, I retired from the selling of clothing, which was never congenial to me; and as I had been buying hides and wool on a small scale since the middle of the fifties, I forthwith devoted myself to the commission business. Frenchmen from the Basque country, among whom were Miguel Leonis, Gaston Oxarart, Domingo Amestoy and Domingo Bastanchury, had commenced to appear here in 1858 and to raise sheep; so that in 1859 large flocks were brought into Southern California, the sheep commanding a price of three dollars and a half per head. My own operations, exceedingly small in the beginning, increased in importance, and by 1862 I was fairly equipped for this venture. Corn, barley and wheat were also then being raised, and I busied myself with these commodities as well.

Most of the early sheepmen prospered and in time bought large tracts of land for their flocks, and with all of them I had dealings of more or less importance. Amestoy's career is worthy of particular mention as exemplifying the three cardinal virtues of business: honesty, application and frugality. He and his wife took in washing; and while the husband went from house to house, leading a horse with a large basket strapped to either side, to collect and deliver the clothes, the wife toiled at the tub. In the end, what they together had saved became the foundation of their important investments in sheep and land. Pedro Larronde, another early sheepman, married the widow of his Basque fellow-countryman, Etchemendy, the tippling baker.

Having regularly established a commission business, I brought consignments of varied merchandise from San Francisco on the semi-monthly steamer Goliah, whose Captain at one time was Robert Haley, and at another his brother Salisbury Haley, a brother-in-law of Tom Mott; and I disposed of them to small dealers with whom I thus became pretty well acquainted. These consignments were sold almost as soon as they arrived. I was careful to bring in only staple articles in the grocery line, and it was long before I appreciated the advantage of carrying sufficient stock to supply a regular demand. On the return trips of the steamer to San Francisco I forwarded such produce as I had accumulated.

I do not recall any important changes in 1862, the declining months of which saw the beginning of the two years' devastating drought. The Civil War was in progress, but we were so far from the scene of strife that we were not materially affected. Sympathy was very general here for the Confederate cause, and the Government therefore retained in Wilmington both troops and clerks who were paid in a badly-depreciated currency, which they were obliged to discount at exorbitant rates, to get money at all; while other employees had to accept vouchers which were subject to a still greater discount. Notwithstanding these difficulties, however, pay-day increased the resources of the pueblo considerably.

Hellman & Brother, a partnership consisting of I. M. and Samuel Hellman, dissolved, on January 2d, I. M. continuing in the dry goods business while Sam took the books and stationery. Another brother and associate, H. M. Hellman, a couple of years before had returned to Europe, where he died. If my memory is accurate, I. W. remained with I. M. Hellman until the former, in 1865, bought out A. Portugal. Samuel A. Widney, who later had a curio store, was for a while with Sam Hellman in a partnership known as Hellman & Widney.

On January 17th, Don Louis Vignes passed away in Los Angeles, at the age of ninety-one years.

January also witnessed one of those typical scenes, in the fitting out of a mule- and wagon-train, never likely to be seen in Los Angeles again. Two hundred wagons and twelve hundred mules, mostly brought from San Francisco on steamers, were assembled for a trip across the desert to convey Government stores.

M. J. Newmark became a partner, on February 1st, in the firm of Howard, Butterworth & Newmark, Federal and State Attorneys with offices in the Temple Building, Los Angeles, and Armory Hall, San Francisco; and it was considered at the time a rapid advance for a man of but twenty-three years of age. The Los Angeles Star of that date, in fact, added a word of good fellowship: "We congratulate friend Newmark on the association."

The intimate relations characteristic of a small community such as ours, and the much more general effect then than nowadays of any tragical occurrence have already been described. Deep sympathy was therefore awakened, early in February, on the arrival of the steamer Senator and the rapid dissemination of the report that Dr. Thomas Foster, the ex-Mayor, had been lost overboard, on January 29th, on the boat's trip northward. Just what happened to Foster will never be known; in San Francisco it was reported that he had thrown himself into the sea, though others who knew him well looked upon the cause of his death as accidental.

But slight attention was paid to the report, brought in by horsemen from San Bernardino on February 4th, that an earthquake had occurred there in the morning, until Captain Tom Seeley returned with the Senator to San Pedro and told about a seismic disturbance at sea, during which he struck the wildest storm off Point Concepción, in all his sea-faring experience. Sailors were then better all-round seamen than now; yet there was greater superstition in Jack Tar's mind, and such a storm made a deep impression upon his imagination.

I have alluded to the dependence of Los Angeles on the outside world, no better evidence of which, perhaps, can be cited than that on the twenty-second of February, George W. Chapin & Company of San Francisco advertised here to furnish servants and other help to anyone in the Southland. About the same time, San Bernardino parties, wishing to bore a little artesian well, had to send to the Northern metropolis for the necessary machinery.

In October, 1860, as I have intimated, Phineas Banning took A. F. Hinchman into partnership, the firm being known as Banning & Hinchman, and they seemed to prosper; but on February 12th, 1862, the public was surprised at the announcement of the firm's dissolution. Banning continued as proprietor, and Hinchman became Banning's Los Angeles agent.

Although cattle-raising was the mainstay of Southern California for many years, and gold-mining never played a very important part here, Wells Fargo & Co., during the spring, frequently shipped thousands of dollars' worth of gold at a time, gathered from Santa Anita, San Gabriel and San Fernando placers, while probably an equally large amount was forwarded out through other channels.

I have already pointed to the clever foresight shown by Abel Stearns when he built the Arcadia Block and profited by the unhappy experience of others, with rain that flooded their property; but I have not stated that in elevating his new building considerably above the grade of the street, somewhat regardless of the rights of others, he caused the surplus water to run off into neighboring streets and buildings. Following the great storm of 1861-62, the City sued Stearns for damages, but he won his case. More than that, the overflow was a Godsend to him, for it induced a number of people to move from Mellus's Row to Arcadia Block at a time when the owner of vast ranches and some of the best town property was already feeling the pinch of the alternate dry and over-wet seasons. The fact is, as I shall soon make clear, that before Stearns had seen the end of two or three successive dry seasons yet to come, he was temporarily bankrupt and embarrassed to the utmost.

By April, the walls and roof for the little Protestant Church at Temple and New High streets had been built, and there the matter rested for two years, when the structure, on which the taxes were unpaid, was advertised for sale.

We have seen that the first Jewish services here were held soon after the arrival of Joseph Newmark in 1854; under the same disadvantageous conditions as had hampered the Protestant denominations, Mr. Newmark volunteered to officiate on the principal holidays until 1862, when the Reverend Abraham Wolf Edelman arrived. Born at Warsaw in 1832, Rabbi Edelman came to America in 1851, immediately after he was married to Miss Hannah Pessah Cohn, and settled successively in New York, Paterson and Buffalo. Coming to California in 1859, he resided in San Francisco until 1862, when he was chosen Rabbi of the orthodox Congregation B'nai B'rith of Los Angeles, and soon attained distinction as a Talmudic scholar and a preacher. The first services under Rabbi Edelman were held in Stearns's, or Arcadia Hall; next, the Congregation worshipped in Leck's Hall on Main Street between Second and Third; and finally, through the courtesy of Judge Ygnácio Sepúlveda, the court room was used. In 1873 the Jews of Los Angeles erected their first synagogue, a brick building entered by a steep stairway leading to a platform, and located on the east side of Fort Street between Second and Third, on what is now the site of the Copp Building next to the City Hall. In 1886, when local Jewry instituted a much more liberal ritual, Rabbi Edelman's convictions induced him to resign. The purchase of a lot for a home on the corner of Sixth and Main streets proved a fortunate investment, later enabling him to enjoy a well-deserved comfort and to gratify his charitable inclinations. It is a strange coincidence that Reverend Edelman's first marriage ceremony was that which blessed Samuel Prager; while the last occasion on which he performed the solemn rites for the dead—shortly before his own death in 1907—was for the same friend. A. M. Edelman, the architect, and Dr. D. W. Edelman, both well-known here, are sons of the Rabbi.

As late in the season as April, hail and snow fell in and near Los Angeles. To the North of the city, the white mantle quite hid the mountains and formed a new and lower snow-line; while within the city, the temperature so lowered that at several intervals during the day, huge hail-stones beat against the window-panes—a very unusual experience for Angeleños.

Because of political charges preferred against A. J. King, then Under Sheriff of the County, the latter, on April 10th, was arrested by Henry D. Barrows, United States Marshal, who had been appointed by President Lincoln, the year previous. Colonel Carleton, Commander of the Southern Military Division, however, soon liberated King. On the last day of the year, the Under Sheriff married the estimable Miss Laura C. Evertsen.

Travelers to Europe have often suffered much annoyance through safe-conduct regulations, but seldom have Americans had their liberty thus restricted by their own authorities. Toward the middle of June, word was received in Los Angeles that, owing to the suspicion lest disloyalists were embarking for Aspinwall, all passengers for California via the Isthmus would be required to take out passports.

Anticipating, by forty years or more, Luther Burbank's work, attention was directed, as early as 1862, to the possibility of eating the cactus and thus finding, in this half-despised plant of the desert, relief from both hunger and thirst. Half a century later, in 1913, Los Angeles established the cactus candy industry through which the boiled pulp of the bisnaga, often spoken of as the fishhook, barrel and nigger-head variety, is made deliciously palatable when siruped from ten to thirty days.

Ygnácio Sepúlveda, declared by the Los Angeles Star "a young gentleman of liberal education, and good, natural endowments, already versed in legal studies," on September 6th was admitted to the District Court Bar.

On January 18th, 1860, the first number of the Semi-Weekly Southern News appeared, containing advertisements in both English and Spanish. It was issued by C. R. Conway and Alonzo Waite, who charged twenty-five cents a copy, or seven dollars a year. On October 8th, 1862, the title was changed to the Los Angeles Semi-Weekly News.

In 1860, the Bella Union, as I have said, was under the management of John King, who came here in 1856; while in 1861 J. B. Winston & Company, who were represented by Henry Reed, controlled the hotel. In 1862 or 1863, John King and Henry Hammel were the managers.

I have told of the purchase of the San Pasqual rancho by Dr. J. S. Griffin. On December 11th, Dr. and Mrs. Griffin for five hundred dollars sold to B. D. Wilson and wife some six hundred and forty acres of that property; and a few hours afterward the Wilsons disposed of two hundred and sixty-two acres for one thousand dollars. The purchaser was Mrs. Eliza G. Johnston, wife of General Albert Sidney Johnston. Mrs. Johnston at once built a neat residence on the tract and called it Fair Oaks, after the plantation in Virginia on which she had been born; and from this circumstance the name of the now well-known Fair Oaks Avenue in Pasadena is derived. At the time of her purchase Mrs. Johnston had hoped to reside there permanently; but the tragic fate of her son in the Ada Hancock disaster, following the untimely death of her husband at Shiloh, and the apparent uselessness of the land, led her to sell to Judge B. S. Eaton what to-day would be worth far more than thousands of acres in many parts of the Southern States. A curious coincidence in the relations of General Sumner, who superseded General Johnston, to the hero of Shiloh is that, later in the War, Sumner led a corps of Union troops at Fair Oaks, Virginia!

Don Ygnácio Coronel, father of António Franco Coronel, and the early school patron to whom I have referred, died in Los Angeles on December 19th, aged seventy years. He had come to California in 1834, and had long been eminent in political councils and social circles. I recall him as a man of strong intellect and sterling character, kind-hearted and popular.

Another effort, without success, to use camels for transportation over the California and adjacent sands, was made in January, 1863, when a camel express was sent out from New San Pedro to Tucson.

Elsewhere I have indicated the condition of the public cemetery. While an adobe wall enclosed the Roman Catholic burial-place, and a brick wall surrounded the Jewish resting-place for the dead, nothing was done until 1863 to improve the Protestant cemetery, although desecration went so far that the little railing around the grave of poor Mrs. Leck, the grocer's wife who had been murdered, was torn down and burned. Finally, the matter cried to Heaven so audibly that in January, Los Angeles Masons appropriated one hundred and fifty dollars, to be added to some five hundred dollars raised by popular subscription; and the Common Council having appointed a committee to supervise the work, William H. Perry put up the fence, making no charge for his services.

About the middle of January word was received in Los Angeles of the death, at Baltimore, of Colonel B. L. Beall, commander for years of the Fort Tejón garrison, and active in the Mojave and Kern River campaigns.

Death entered our home for the first time, when an infant daughter, less than a month old, died this year on February 14th.

In February, the editor of the News advised the experiment of growing cotton as an additional activity for the Colorado Indians, who were already cultivating corn, beans and melons. Whether this suggestion led William Workman into cotton culture, I do not know; at any rate, late in November of the same year F. P. F. Temple was exhibiting about town some well-matured bolls of cotton raised on Workman's ranch, and the next spring saw in El Monte a number of fields planted with cotton seed. A year later, J. Moerenhout sent Los Angeles cotton to an exhibition in France, and received from across the water official assurance that the French judges regarded our product as quite equal to that grown in the Southern States. This gave a slight impetus to cotton-culture here and by January, 1865, a number of immigrants had arrived, looking for suitable land for the production of this staple. They soon went to work, and in August of that year many fields gave promise of good crops, far exceeding the expectations of the experimenters.

In the month of March a lively agitation on behalf of a railroad began in the public press, and some bitter things were said against those who, for the sake of a little trade in horses or draying, were opposed to such a forward step; and under the leadership of E. J. C. Kewen and J. A. Watson, our Assemblymen at that session, the Legislature of 1863 passed an act authorizing the construction of the Los Angeles & San Pedro Railroad. A public meeting was called to discuss the details and to further the project; but once more no railroad was built or even begun. Strange as it seems, the idea of a railroad for Los Angeles County in 1863 was much too advanced for the times.

Billed as one who had "had the honor of appearing before King William IV. and all the principal crowned heads of Europe," Professor Courtier held forth with an exhibition of magic in the Temple Theatre; drawing the usual crowd of—royalty-haters!

In 1863, Santa Catalina was the scene of a gold-mining boom which soon came to naught, and through an odd enough occurrence. About April, Martin M. Kimberly and Daniel E. Way staked out a claim or two, and some miners agreed on a code of laws for operations in what was to be known as the San Pedro Mining District, the boundaries of which were to include all the islands of the County. Extensive claims, chiefly in Cherry and Joly valleys and on Mineral Hill, were recorded, and streets were laid out for a town to be known as Queen City; but just as the boom seemed likely to mature, the National Government stepped in and gave a quietus to the whole affair. With or without foundation, reports had reached the Federal authorities that the movement was but a cloak to establish there well-fortified Confederate headquarters for the fitting out and repair of privateers intended to prey upon the coast-wise traders; and on February 5th, 1864, Captain B. R. West, commanding the Fourth California Infantry, ordered practically all of the miners and prospectors to leave the island at once. The following September the National troops were withdrawn, and after the War the Federal authorities retained control of a point on the island deemed serviceable for lighthouse purposes.

In the spring of 1863, feeling ill, I went to San Francisco to consult Dr. Toland, who assured me that there was nothing serious the matter with me; but wishing to satisfy myself more thoroughly, I resorted to the same means that I dare say many others have adopted—a medical examination for life insurance! Bernhard Gattel, general agent of the Germania Life Insurance Company, at 315 Montgomery Street, wrote out my application; and on March 20th, a policy, numbered 1472, was issued, making me, since the fall of 1913, the oldest living policy-holder in the Southwest, and the twentieth oldest of the Germania's patrons in the world.

Californians, during that period of the War when the North was suffering a series of defeats, had little use for greenbacks. At one time, a dollar in currency was worth but thirty-five cents, though early in April it was accepted at sixty-five, late in August at ninety, and about the first of October at seventy-five cents; even interest-bearing gold notes being worth no more. This condition of the money market saw little change until some time in the seventies; and throughout the War greenbacks were handled like any other commodity. Frank Lecouvreur, in one of these periods, after getting judgment in a suit against Deputy Surveyor William Moore, for civil engineering services, and being paid some three hundred and eighty-three dollars in greenbacks, was disconcerted enough when he found that his currency would command but one hundred and eighty dollars in gold. San Francisco merchants realized fortunes when a decline occurred, as they bought their merchandise in the East for greenbacks and sold it on the Coast for gold. Los Angeles people, on the other hand, enjoyed no such benefit, as they brought their wares from San Francisco and were therefore obliged to liquidate in specie.

Among the worst tragedies in the early annals of Los Angeles, and by far the most dramatic, was the disaster on April 27th to the little steamer Ada Hancock. While on a second trip, in the harbor of San Pedro, to transfer to the Senator the remainder of the passengers bound for the North, the vessel careened, admitting cold water to the engine-room and exploding the boiler with such force that the boat was demolished to the water's edge; fragments being found on an island even half to three-quarters of a mile away. Such was the intensity of the blast and the area of the devastation that, of the fifty-three or more passengers known to have been on board, twenty-six at least perished. Fortunate indeed were those, including Phineas Banning, the owner, who survived with minor injuries, after being hurled many feet into the air. Among the dead were Thomas W. Seeley, Captain of the Senator; Joseph Bryant, Captain of the Ada Hancock; Dr. H. R. Myles, the druggist, who had been in partnership, opposite the Bella Union, with Dr. J. C. Welch, an arrival of the early fifties who died in 1869; Thomas H. Workman, Banning's chief clerk; Albert Sidney Johnston, Jr.; William T. B. Sanford, once Postmaster; Louis Schlesinger and William Ritchie, Wells Fargo's messenger, to whom was entrusted ten thousand dollars, which, as far as my memory goes, was lost. Two Mormon missionaries, en route to the Sandwich Islands, were also killed. Still another, who lost not only his treasure but his life, was Fred E. Kerlin of Fort Tejón: thirty thousand dollars which he carried with him, in greenbacks, disappeared as mysteriously as did the jewelry on the persons of others, and from these circumstances it was concluded that, even in the presence of Death, these bodies had been speedily robbed. Mrs. Banning and her mother, Mrs. Sanford, and a daughter of B. D. Wilson were among the wounded; while Miss M. Hereford, Mrs. Wilson's sister and the fiancée of Dr. Myles, was so severely injured that, after long suffering, she also died. Although the accident had happened about five o'clock in the afternoon, the awful news, casting a general and indescribable gloom, was not received in town until nearly eight o'clock; when Drs. Griffin and R. T. Hayes, together with an Army surgeon named Todd, hastened in carriages to the harbor where soldiers from Camp Drum had already asserted their authority. Many of the victims were buried near the beach at New San Pedro. While I was calling upon Mrs. Johnston to express my sympathy, the body of her son was brought in; and words cannot describe the pathos of the scene when she addressed the departed as if he were but asleep.

In June the Government demanded a formal profession of loyalty from teachers, when Miss Mary Hoyt and Miss Eliza Madigan took the oath, but Mrs. Thomas Foster and William McKee refused to do so. The incident provoked bitter criticism, and nothing being done to punish the recalcitrants, the Los Angeles Board of Education was charged with indifference as to the allegiance of its public servants.

During 1863 sectional feeling had grown so bitter on account of the War that no attempt was made to celebrate the Fourth of July in town. At Fort Latham, however, on the Ballona Ranch, the soldiers observed the day with an appropriate demonstration. By the end of July, troops had been sent from Drum Barracks to camp in the city—for the protection, so it was asserted, of Union men whose lives were said to be in danger, although some people claimed that this movement was rather for the purpose of intimidating certain leaders with known sympathy for the South. This military display gave Northerners more backbone; and on the twenty-sixth of September a Union mass-meeting was held on Main Street in front of the Lafayette Hotel.

Eldridge Edwards Hewitt, a Mexican War veteran who came to California in 1849 to search for gold, arrived in Los Angeles on July 31st and soon went on a wild-goose chase to the Weaver Diggings in Arizona, actually tramping with luggage over five hundred miles of the way! After his return, he did odd jobs for his board, working in a stationery and toy store on Main Street, kept by the Goldwater Brothers, Joe and Mike, who had arrived in the early sixties; and later he entered the employ of Phineas Banning at Wilmington, with whom he remained until the completion of the Los Angeles & San Pedro Railroad in 1870, when he became its Superintendent. When the Southern Pacific obtained control of that road in 1873, Hewitt was made Agent, and after the extension of the line from San Francisco he was appointed Division Superintendent. In that capacity he brought Senator Leland Stanford to me, as I shall elsewhere relate, to solicit H. Newmark and Company's patronage.

It was in 1863 that Dr. J. S. Griffin, father of East Los Angeles, purchased two thousand acres in that section, at fifty cents an acre; but even at that price he was only induced to buy it by necessity. Griffin wanted sheep-pasture, and had sought to secure some eight hundred acres of City land along the river; but as this would prevent other cattle or sheep from approaching the water to drink, the Common Council refused Griffin's bid on the smaller area of land and he was compelled to buy the mesa farther back. It seems to me that B. D. Wilson, J. G. Downey and Hancock M. Johnston, General Johnston's son, also had something to do with this transaction. Both Downey and Griffin avenues derived their names from the association of these two gentlemen with that section.

A smallpox epidemic which had started in the previous fall spread through Los Angeles in 1863, and owing possibly to the bad sanitary and climatic conditions much vigilance and time were required to eradicate it; compulsory vaccination not having been introduced (as it finally was at the suggestion of Dr. Walter Lindley) until the summer of 1876. The dread disease worked its ravages especially among the Mexicans and Indians, as many as a dozen of them dying in a single day; and these sufferers and their associates being under no quarantine, and even bathing ad libitum in the zanjas, the pest spread alarmingly. For a time fatalities were so frequent and the nature of the contagion so feared that it was difficult to persuade undertakers to bury the dead, even without funeral or other ceremony.

Following the opening of the Owens River Mines this year, Los Angeles merchants soon established a considerable trade with that territory. Banning inaugurated a system of wagon-trains, each guarded by a detachment of soldiers. The San Fernando mountains, impassable for heavy teaming, were an obstacle to regular trade with the new country and compelled the use of a circuitous route over poor roads. It became necessary, therefore, to consider a means of overcoming the difficulty, much money having already been spent by the County in an abortive attempt to build a tunnel. This second plan likewise came to naught, and it was in fact more than a decade before the Southern Pacific finally completed the famous bore.

Largely because of political mistakes, including a manifestation of sympathy for the Southern Confederacy that drew against him Northern resentment and opposition, John G. Downey, the Democratic nominee for Governor, was defeated at the election in September; Frederick F. Low, a Republican, receiving a majority of over twenty thousand votes.

In October, a peddler named Brun was murdered near Chino. Brun's brother, living at San Bernardino and subsequently a merchant of prominence there, offered two hundred dollars of his slender savings as a reward for the capture of the slayer; but nothing ever came of the search.

In November the stern necessities of war were at last driven home to Angeleños when, on the ninth of that somber month, Don Juan Warner, Deputy Provost Marshal, appeared with his big blank books and began to superintend the registering of all able-bodied citizens suitable for military service. To many, the inquisition was not very welcome and, had it not been for the Union soldiers encamped at Drum Barracks, this first step toward compulsory enrollment would undoubtedly have resulted in riotous disturbances.

I have frequently named Tom Mott, but I may not have said that he was one of the representative local Democratic politicians of his day. He possessed, indeed, such influence with all classes that he was not only elected Clerk of Los Angeles County in 1863, but succeeded himself in 1865, 1867 and 1869, afterward sitting in the State Assembly; and in 1876, he was appointed a delegate to the National Convention that nominated Samuel J. Tilden for the Presidency. His relations in time with Stanford, Crocker, Huntington and Hopkins were very close, and for at least twenty-five years he acted as their political adviser in all matters appertaining to Southern California. Tall, erect and dignified, scrupulously attired and distinguished by his flowing beard, Tom was for more than half a century a striking figure in Los Angeles.