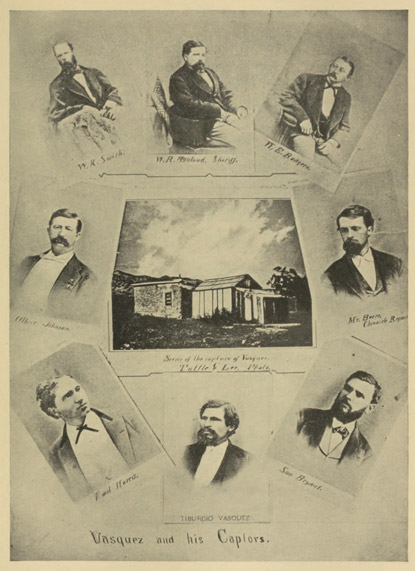

Vasquez and his Captors

(Top) D. K. Smith,

William R. Rowland,

Walter E. Rodgers.

(Middle) Albert Johnson,

Greek George's Home,

G. A. Beers.

(Bottom) Emil Harris,

Tibúrcio Vasquez,

J. S. Bryant.

Although a high school had been proposed for Los Angeles as early as 1860, it was not until 1873, during Dr. W. T. Lucky's superintendency and under his teaching, that high-school courses were inaugurated here. Then the more advanced students were accommodated in the schoolhouse on Pound Cake Hill, where the Court-house now stands; and from this humble beginning the present high-school system of Los Angeles has been evolved. Later, under Dr. T. H. Rose's leadership, the grammar departments were removed to the other school buildings and the High School was conducted as an independent institution.

In 1874, S. Lazard & Company dissolved, Eugene and Constant Meyer succeeding, on June 15th, under the firm name of Eugene Meyer & Company or, as the store was better known, the City of Paris.

Charles H., or Charley White, long prominent in the passenger department of the Southern Pacific, entered the service of the Los Angeles & San Pedro Railroad in 1874, as John Milner's assistant, and soon became the regular ticket-agent here. After forty years of invaluable service, he is still with the Southern Pacific occupying the important position of Chief Clerk of the General Passenger Office.

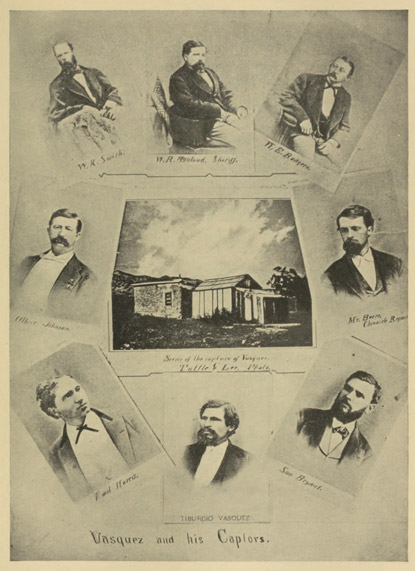

Vasquez and his Captors

(Top) D. K. Smith,

William R. Rowland,

Walter E. Rodgers.

(Middle) Albert Johnson,

Greek George's Home,

G. A. Beers.

(Bottom) Emil Harris,

Tibúrcio Vasquez,

J. S. Bryant.

George H. Peck, County Superintendent of Schools between 1874 and 1876, was a Vermonter who came in 1869 and bought five hundred acres of land near El Monte. On his first visit to the Coast, Peck handled hay in San Francisco when it was worth two hundred dollars a ton; then he mined a little; and subsequently he opened the first public school in Sacramento and the first industrial school in San Francisco.

Andrew A. Weinschank, a veteran of the Battle of Vera Cruz who came to Los Angeles in 1856, died on February 16th, 1874. For a while, he sold home-made sauerkraut, pickles and condiments, and was one of a well-known family in the German pioneer group here. Carrie, one of Weinschank's daughters, married a circus man named Lee who made periodical visits to Los Angeles, erecting a small tent, at first somewhere in the neighborhood of the present Times Building, in which to conduct his show. Later, Polly Lee became a rider in the circus and with her father electrified the youth of the town when Lee, in the character of Dick Turpin, and mounted on his charger, Black Bess, carried off the weeping Polly to his den of freebooters. A son, Frank A. Weinschank, was a pioneer plumber.

In the early seventies, while the Southern Pacific Railway was building from San Francisco to San José, some twelve or fifteen bandits, carousing at a country dance in the Mexican settlement, Panamá (about six miles south of Bakersfield) planned to cross the mountains and hold up the pay-car. They were unsuccessful; whereupon, they turned their attention to the village of Tres Pinos, robbed several store-keepers and killed three or four men. They were next heard of at little Kingston, in Tulare County, where they plundered practically the whole town. Then they once more disappeared.

Presently various clues pointed to the identity of the chief bandido as one Tibúrcio Vasquez, born in Monterey in the thirties, who had taken to the life of an outlaw because, as he fantastically said, some Gringos had insolently danced off with the prettiest girls at fandangos, among them being his sweetheart whom an American had wronged. With the exception of his Lieutenant, Chavez, he trusted no one, and when he moved from place to place, Chavez alone accompanied him. In each new field he recruited a new gang, and he never slept in camp with his followers.

Although trailed by several sheriffs, Vasquez escaped to Southern California leading off the wife of one of his associates—a bit of gallantry that contributed to his undoing, as the irate husband at once gave the officers much information concerning Vasquez's life and methods. One day in the spring of 1874, Vasquez and three of his companions appeared at the ranch of Alessandro Repetto, nine miles from town, disguised as sheep-shearers. The following morning, while the inmates of the ranch-house were at breakfast, the highwaymen entered the room and held up the defenceless household. Vasquez informed Repetto that he was organizing a revolution in Lower California and merely desired to borrow the trifling sum of eight hundred dollars. Repetto replied that he had no money in the house; but Vasquez compelled the old man to sign a check for the sum demanded, and immediately dispatched to town a boy working for Repetto, with the strict injunction that if he did not return with the money alone, and soon, his master would be shot.

When the check was presented at the Temple & Workman Bank, Temple, who happened to be there, became suspicious but could elicit from the messenger no satisfactory response to his questions. The bank was but a block from the Courthouse; and when Sheriff Rowland hurriedly came, in answer to a summons, he was inclined to detain the lad. The boy, however, pleaded so hard for Repetto's life that the Sheriff agreed to the messenger's returning alone with the money. Soon after, Rowland and several deputies started out along the same trail; but a lookout sighted the approaching horsemen and gave the alarm. Vasquez and his associates took to flight and were pursued as far as Tejunga Pass; but as the cutthroats were mounted on fresh horses, they escaped. Even while being pursued, Vasquez had the audacity to fleece a party of men in the employ of the Los Angeles Water Company who were doing some work near the Alhambra Tract. The well-known Angeleño and engineer in charge, Charles E. Miles, was relieved of an expensive gold watch.

In April, 1874, Sheriff Rowland heard that Vasquez had visited the home of "Greek George"—the Smyrniot camel-driver to whom I have referred—and who was living about ten miles from Los Angeles, near the present location of Hollywood. Rowland took into his confidence D. K. Smith and persuaded him to stroll that way, ostensibly as a farmer's hand seeking employment; and within two weeks Smith reported to Rowland that the information as to Vasquez's whereabouts was correct. Rowland then concluded to make up a posse, but inasmuch as a certain element kept Vasquez posted regarding the Sheriff's movements, Rowland had to use great precaution. Anticipating this emergency, City Detective Emil Harris—four years later Chief of Police—had been quietly transferred to the Sheriff's office; in addition to whom, Rowland selected Albert Johnson, Under Sheriff; B. F. Hartley, a local policeman; J. S. Bryant, City Constable; Major Henry M. Mitchell, an attorney; D. K. Smith; Walter Rodgers, proprietor of the Palace Saloon; and G. A. Beers, a correspondent of the San Francisco Chronicle. All these were ordered to report, one by one with their horses, shortly after midnight, at Jones's Corral on Spring Street near Seventh. Arms and ammunition, carefully packed, were likewise smuggled in. Whether true or not that Vasquez would speedily be informed of the Sheriff's whereabouts, it is certain that, in resolving not to leave his office, Rowland sacrificed, for the public weal, such natural ambition that he cannot be too much applauded; not even the later reward of eight thousand dollars really compensating him for his disappointment.

By half-past one o'clock in the morning, the eight members of the posse were all in the saddle and silently following a circuitous route. At about daybreak, in dense fog, they camped at the mouth of Nichols's Canyon—two miles away from the house of Greek George—where Charles Knowles, an American, was living. When the fog lifted, Johnston, Mitchell, Smith and Bryant worked their way to a point whence they could observe Greek George's farm; and Bryant, returning to camp, reported that a couple of gray horses had been seen tied near the ranch-house. Shortly thereafter, a four-horse empty wagon, driven by two Mexicans, went by the cañon and was immediately stopped and brought in. The Mexicans were put in charge of an officer, and about the same time Johnston came tearing down the ravine with the startling statement that Vasquez was undoubtedly at Greek George's!

A quick consultation ensued and it was decided by the posse to approach their goal in the captured vehicle, leaving their own horses in charge of Knowles; and having warned the Mexicans that they would be shot if they proved treacherous, the deputies climbed into the wagon and lay down out of sight. When a hundred yards from the house, the officers stealthily scattered in various directions. Harris, Rodgers and Johnston ran to the north side, and Hartley and Beers to the west. Through an open door, Vasquez was seen at the breakfast table, and Harris, followed by the others, made a quick dash for the house. A woman waiting on Vasquez attempted to shut the officers out; but Harris injected his rifle through the half-open door and prevented her. During the excitement, Vasquez climbed through a little window, and Harris, yelling, "There he goes!" raised his Henry rifle and shot at him. By the time Harris had reached the other side of the house, Vasquez was a hundred feet away and running like a deer toward his horse. In the meantime, first Hartley and then the other officers used their shotguns and slightly wounded him again. Vasquez then threw up his hands, saying: "Boys, you've done well! but I've been a damned fool, and it's my own fault!" The identity of the bandit thus far had not been established; and when Harris asked his name, he answered, "Alessandro Martinez."[32] In the meantime, captors and prisoner entered the house; and Vasquez, who was weakened from his wounds, sat down, while the young woman implored the officers not to kill him. At closer range, a good view was obtained of the man who had so long terrorized the State. He was about five feet six or seven inches in height, sparely built, with small feet and hands—in that respect by no means suggesting the desperado—with a low forehead, black, coarse hair and mustache, and furtive, cunning eyes.

By this time, the entire posse, excepting Mitchell and Smith (who had followed a man seen to leave Greek George's), proceeded to search the house. The first door opened revealed a young fellow holding a baby in his arms. He, the most youthful member of the organization, had been placed on guard. There were no other men in the house, although four rifles and six pistols, all loaded and ready for use, were found. Fearing no such raid, the other outlaws were afield in the neighborhood; and being warned by the firing, they escaped. One of Vasquez's guns, by the way, has been long preserved by the family of Francisco Ybarra and now rests secure in the County Museum.

Underneath one of the beds was found Vasquez's vest containing Charley Miles's gold watch, which Harris at once recognized. The prisoner was asked whether he was seriously hurt and he said that he expected to die, at the same time admitting that he was Vasquez and asking Harris to write down some of his bequests. He said that he was a single man, although he had two children living at Elizabeth Lake; and he exhibited portraits of them. He protested that he had never killed a human being, and said that the murders at Tres Pinos were due to Chavez's disobedience of orders.

The officers borrowed a wagon from Judge Thompson—who lived in the neighborhood—into which they loaded Vasquez, the boy and the weapons, and so proceeded on their way. When they arrived near town, Smith and Mitchell caught up with them. Mitchell was then sent to give advance notice of Vasquez's capture and to have medical help on hand; and by the time the party arrived, the excitement was intense. The City Fathers, then in session, rushed out pellmell and crowds surrounded the Jail. Dr. K. D. Wise, Health Officer, and Dr. J. P. Widney, County Physician, administered treatment to the captive. Vasquez, in irons, pleaded that he was dying; but Dr. Widney, as soon as he had examined the captive, warned the Sheriff that the prisoner, if he escaped, would still be game for a long day's ride. Everybody who could, visited him and I was no exception. I was disgusted, however, when I found Vasquez's cell filled with flowers, sent by some white women of Los Angeles who had been carried away by the picturesque career of the bandido; but Sheriff Rowland soon stopped all such foolish exuberance.

Vasquez admitted that he had frequently visited Mexicans in Los Angeles, doing this against the advice of his lieutenant, Chavez, who had warned him that Sheriff Rowland also had good friends among the Mexicans.

Among those said to have been in confidential touch with Vasquez was Mariano G. Santa Cruz, a prominent figure, in his way, in Sonora Town. He kept a grocery about three hundred feet from the old Plaza Church, on the east side of Upper Main Street, and had a curiously-assorted household. There on many occasions, it is declared, Vasquez found a safe refuge.

Five days after the capture, Signor Repetto called upon the prisoner, who was in chains, and remarked: "I have come to say that, so far as I am concerned, you can settle that little account with God Almighty!" Vasquez, with characteristic flourishes, thanked the Italian and began to speak of repayment, when Repetto replied: "I do not expect that. But I beg of you, if ever you resume operations, never to visit me again." Whereupon Vasquez, placing his hand dramatically upon his breast, exclaimed: "Ah, Señor, I am a cavalier, with a cavalier's heart!"—¡Señor Repetto, yo soy un caballero, con el corazón de un caballero!

As soon as Vasquez's wounds were healed, he was taken by Sheriff Rowland to Tres Pinos and there indicted for murder. Miller & Lux, the great cattle owners, furnished the money, it was understood, for his defense—supposedly as a matter of policy. His attorneys asked for, and obtained, a change of venue, and Vasquez was removed to San José. There he was promptly tried, found guilty and, in March, 1875, hanged.

Many good anecdotes were long told of Vasquez; one of which was that he could size up a man quickly, as to whether he was a native son or not, by the direction in which he would roll a cigarette—toward or away from himself! As soon as the long-feared bandit was in captivity, local wits began to joke at his expense. A burlesque on Vasquez was staged late in May at the Merced Theater; and the day the outlaw was captured, a merchant began his advertisement: "Vasquez says that Mendel Meyer has the Finest and Most Complete Stock of Dry Goods and Clothing, etc."

In the spring of 1874, Charles Maclay, with whom were associated George K. and F. B. Porter, purchased the San Fernando rancho which consisted of fifty-six thousand acres and embraced the old Spanish Mission; and on April 20th, Maclay invited fifty of his friends to a picnic on his newly-acquired possession. During the day some one suggested founding a town there. The name of the new settlement was to be decided by a vote of the participants, and almost unanimously they selected the title of San Fernando. Within a couple of weeks, hundreds of lots were sold and the well-known colony was soon on the way to prosperity. Boring for petroleum commenced in the San Fernando Mountains about that time, and the new town became the terminus of the Southern Pacific until the long tunnel was completed. Maclay, who was a native of Massachusetts, came to California at about the same time as I did; he was at first a tanner in Santa Cruz, but later came south and, entering into politics in addition to his other activities, became State Senator, in which position he attained considerable local prominence.

A charming home of the seventies was that of Dr. and Mrs. Shaw, pioneers situated, as I recollect, on San Pedro Street perhaps as far south as what is now Adams. They conducted a diversified nursery, including some orange trees, to obtain which Shaw had journeyed all the way to Nicaragua.

Toward the end of April, 1874, General E. F. Beale and Colonel R. S. Baker, representing themselves and New York capitalists, sought support for a new railroad project—a single-track line to run from this city to Shoo-Fly Landing, located, I think, near the present Playa del Rey and considerably north of San Pedro; where a town, Truxton—doubtless named after the General's son—was to be founded. The proposed railway was to be known as the Los Angeles & Truxton Railroad, with a route from the western part of the city in the direction of Ciénega and the Rincon de los Bueyes, and along a corner of the Ballona. The estimated length of the line was fourteen miles, and the projectors claimed that it would enable the Angeleño to reach San Francisco within thirty hours, with but one night at sea, and so add to the comfort, convenience and cheapness of passenger travel. A new harbor and an additional pier stretching far into the ocean were to be features of the enterprise; but for some reason or other, nothing grew out of the movement. As late as the following September, the promoters were still interviewing councilmen and ranch-owners; but the Los Angeles & Truxton Railroad remained a mere fancy of the financier and engineer.

For a resort that never came to be settled by a community, Truxton acquired some fame in the early seventies, a rumor also being current in the summer of 1874 that a fine sea-shore hotel was to be built there. A clipping before me of the same date even says that "the roads to Santa Monica, Truxton and Will Tell's are in splendid order—the former being the finest natural highway on the Pacific Coast."

F. X. Eberle and wife, Marsetes, came here in 1874, bought six or seven acres on the corner of San Pedro and the present Eighth streets, and fitted up the City Gardens, with bowling alleys, swings, lawns and bowers, erecting there also a picturesque windmill.

I have expressed the surprise that I felt, when, upon my return from New York in 1868, I observed that the approaches to the hills were dotted here and there with little homes. This extension of the residence area, together with the general lack of street and sidewalk improvements making travel to and from the town somewhat inconvenient, suggested, I have no doubt, the need of the first street railroad here. In 1869, Judge R. M. Widney, together with his associates, obtained a fifty-year franchise; and by 1874, the little Spring and Sixth Street line—in time bought by S. C. Hubbell and J. E. Hollenbeck—had been built and was in operation. It is my recollection that this line (partly paid for by subscriptions from property owners along the selected route, each of whom contributed fifty cents per running foot) began at the Plaza and extended as far out as Pearl and Sixth streets by way of Main, Spring, First, Fort, Fourth, Hill, Fifth and Olive; and that it was at the Sixth and Pearl Street terminus that the almost miniature wooden barn was put up. For the convenience of the traveling public, two bob-tailed, one-horse cars with a small platform at each end were used over a single track approximately but two and a half miles in length; and to permit these cars to pass each other when they met halfway along the line, a turnout or side-track was constructed. Many a time at such a siding have I wasted precious minutes awaiting the arrival of the other, belated car; and the annoyance of these delays was accentuated when, in winter, the cars stuck in the mud and often required an hour or more to make the run from one end of the line to the other. Indeed, the ties having been laid almost on the surface of the streets, service in bad weather was sometimes suspended altogether. Each car was in charge of a driver who also acted as conductor and was permitted to stop as often as he pleased to take on or let off passengers; and while the single horse or mule jogged along slowly, the driver, having wound his reins around the handle of the brake, would pass through the never-crowded vehicle and take up the fares. Single rides cost ten cents; four tickets were sold for two bits; and twenty tickets were given for a dollar. So provincial was the whole enterprise that passengers were expected to purchase their tickets either at W. J. Brodrick's book store or of Dr. Fred. P. Howard, the druggist. At a later period, a metal box with a glass front was installed, into which the passenger was required to drop his coin or ticket.

In those modest days, small compensation in public utility enterprises—if such they could be called—was quite acceptable; and since the Spring and Sixth Street line had proven rather profitable, it was not long before W. J. Brodrick, Governor Downey, O. W. Childs, Dave Waldron, I. W. Hellman and others inaugurated a second horse-railway. This was popularly known as the Main Street line and extended straight down Main Street from Temple Block to Washington Gardens. Much the same kind of equipment was used, one horse or mule poking along with a bob-tailed car in tow, seating at most eight or ten passengers; but the fare for adults was ten cents, and for children five. At night, the motor power and the couple of cars were housed in a barn at either Main or Washington Street.

Soon after this line was in running order, it was extended from Washington south to Jefferson, out Jefferson to Wesley (now University) Avenue, and thence to the race-track at Agricultural Park; and there the shed for this section was erected. Still later, a branch was built out Washington Street to Figueroa, and down Figueroa to Jefferson, where it connected with the first extension. No formal transfers were made, transfer-tickets first coming into vogue in Los Angeles about 1889. Two routes for the cars were arranged, both running between Temple Block and the race-track. The entire system was controlled by the Main Street & Agricultural Park Railroad Company, with which W. J. Brodrick was associated as its first President, continuing in that office until his death in 1898. In 1877, Colonel John O. Wheeler, the quondam journalist, was Manager. Later, E. M. Loricke was Superintendent—the same Loricke who built the line between Oakland and Berkeley, and was finally killed by one of his own cars. James Gallagher, who went to work for the Main Street & Agricultural Park Railroad Company in October, 1888, and who had charge also of one of the first electric cars run here, is still a street-car conductor pleasantly known, with the longest record for service of any conductor in the city. As I have said, travel in winter was anything but expeditious and agreeable; and it was not uncommon for passengers, when a car left the track, to get out and assist in the operation of putting it back. Notwithstanding these drawbacks, however, the mule-car novelty became popular with some; and one Spanish girl in particular, whose father amply supplied her with pocket-money, was a frequent passenger, riding back and forth, from hour to hour, for months. As late as 1887, there were no cars before six o'clock in the morning or after ten o'clock at night; and in that same year, serious complaint was made that, despite a city ordinance forbidding any street railway company to carry more than forty persons in a car drawn by a single horse, the ordinance was shamefully disregarded. Another regulation then frequently disobeyed was supposed to limit smoking to the rear end of street cars.

The same year, D. V. Waldron bought about thirty-five acres on the southwest corner of Main and Washington streets, soon known as the Washington Gardens, later Chute's Park. These Gardens, among the most popular pleasure resorts here, were served by the Main Street cars which ran direct to the gate. In addition to a Sunday afternoon variety show that held forth in a small pavilion and secured most of its talent from Wood's Opera House, there was also dancing for those who wished to indulge. I may add that this so-called opera house was nothing more than a typical Western song and dance resort, the gallery being cut up into boxes where the actresses, between the acts, mingled with the crowd. Patrons indulged in drinking and smoking; and the bar in front did a thriving business. An insignificant collection of animals—one of which, an escaping monkey, once badly bit Waldron—attracted not only the children, but their elders as well; and charmingly-arranged walks, amid trees and bowers, afforded innocent and healthful means of recreation. Waldron later went to Alaska, where a tragic death closed his career: alone and in want, he was found, in May, 1911, dead in his hut.

Waldron and Eberle's prosperity may have influenced George Lehman's fortunes; but however that was, he always maintained his popularity. Many a joke was cracked at his expense; yet everybody had a good word for him. Here is a newspaper note of '74:

Round House George is making great improvements in his property at Fort and Sixth streets. He has already, at great expense, set out a post and whitewashed a cactus plant!

The popularity of the 38's Fire Company soon inspired a second group of the good men of Los Angeles; and in 1874 or 1875, George Furman, George E. Gard, Joe Manning, John R. Brierly, Bryce McClellan and others started Confidence Engine Company No. 2, obtaining a steamer known as an Amoskeag, which they installed in a building on Main Street near First, on what was later the site of Childs' Opera House. It soon developed, as in the days of the San Pedro stages when the most important feature of the trip was the race to town, that a conflagration was a matter of secondary importance, the mad dash, in rivalry, by the two companies being the paramount object. This was carried to such an extent that the day following a fire was largely given to discussing the race, and the first thing that everybody wished to know was, who got there first? Indeed, I believe that many an alarm was sounded to afford the boys around town a good chance to stake their bets! All this made the fire-laddies the most popular groups in the pueblo; and in every public parade for years the volunteer fire companies were the chief attraction. In 1876, Walter S. Moore, an arrival of 1875, became the Confidence Engine Company's Secretary, that being the commencement of his career as a builder of the department. In 1877, Moore was elected President, occupying that office till 1883 when he was made Chief Engineer of the Los Angeles Fire Department.

On May 13th, 1874, the Los Angeles Daily Star contained the following reference to Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Newmark and an event of particular interest to me and my family:

Mr. Newmark, père and wife, were among the passengers for San Francisco by the Senator yesterday. This well-known and highly-esteemed couple go to attend the marriage of their son, Judge M. J. Newmark, which event occurs on the seventh proximo, as announced in the Star some time ago.

Eugene Meyer and myself attended the wedding, leaving Los Angeles by stage and completely surprising the merry company a few moments before the groom's father performed the ceremony. The fair bride was Miss Sophie Cahen, and the occasion proved one of the very agreeable milestones in an interesting and successful career. The first-born of this union, Henry M. Newmark, now of Morgan & Newmark, has attained civic distinction, being President of the Library Board.

The reason we journeyed north by stage was to escape observation, for since the steamer-service had been so considerably improved, most of our friends were accustomed to travel by water. The Pacific Mail Steamship Company at that time was running the Senator, the Pacific, the Orizaba and the Mohongo, the latter being the gunboat sold by the Government at the end of the War and which remained on the route until 1877; while the line controlled by Goodall, Nelson & Perkins or Goodall, Nelson & Company had on their list the Constantine, the Kalorama, the Monterey and the San Luis, sometimes also running the California, which made a specialty of carrying combustibles. A year later, the Ancon commenced to run between San Francisco and San Diego, and excepting half a year when she plied between the Golden Gate and Portland, was a familiar object until 1884.

The Farmers & Merchants Bank, on June 15th, 1874, moved to their new building on the west side of Main Street, opposite the Bella Union.

On July 25th, 1874, Conrad Jacoby commenced in the old Lanfranco Building the weekly Sued-Californische Post; and for fifteen years or more it remained the only German paper issued in Southern California. Jacoby's brother, Philo, was the well-known sharpshooter.

Henry T. Payne, the early photographer, was probably the first to go out of town to take views in suburbs then just beginning to attract attention. Santa Monica was his favorite field, and a newspaper clipping or two preserve the announcements by which the wet-plate artist stimulated interest in his venture. One of these reads:

Mr. Payne will be at Santa Monica next Sunday, and take photographic views of the camp, the ocean, the surrounding scenery, and such groups of campers and visitors as may see fit to arrange themselves for that purpose;

while another and rather contradictory notice is as follows:

To make photographs of moving life, such as Mr. Payne's bathing scenes at Santa Monica next Sunday, it is absolutely necessary that everybody should keep perfectly still during the few seconds the plate is being exposed, for the least move might completely spoil an otherwise beautiful effect. Santa Monica, with its bathers in nice costume, sporting in the surf, with here and there an artistically-posed group basking in the sunshine, ought to make a beautiful picture.

As late as 1874, Fort Street—not yet called Broadway—was almost a plain, except for the presence of a few one-story adobe houses. J. M. Griffith, the lumberman, put up the first two-story frame dwelling-house between Second and Third streets, and Judge H. K. S. O'Melveny the second; shortly after which Eugene Meyer and myself built our homes in the same block. These were put upon the lots formerly owned by Burns & Buffum. Within the next two or three years, the west side of Fort Street between Second and Third was the choicest residence neighborhood in the growing city, and there was certainly not the remotest idea at that time that this street would ever be used for business purposes. Sometime later however, as I was going home one day, I met Griffith and we walked together from Spring Street down First, talking about the new County Bank and its Cashier, J. M. Elliott—whom Griffith had induced four years previously to come to Los Angeles and take charge of Griffith, Lynch & Company's lumber yard at Compton. We then spoke of the city's growth, and in the course of the conversation he said: "Newmark, Fort Street is destined to be the most important business thoroughfare in Los Angeles." I laughed at him, but Time has shown the wisdom of Griffith's prophecy.

The construction of this Fort Street home I commenced in the spring, contracting with E. F. Keysor as the architect, and with Skinner & Small as the builders. In September, we moved in; and I shall never forget a happy compliment paid us the first evening. We had already retired when the sound of music and merriment made it unmistakable that we were being serenaded. Upon opening the door, we saw a large group of friends; and having invited them into the house, the merrymakers remained with us until the early morning hours.

In July, 1874, the Los Angeles County Bank was started with a capital of three hundred thousand dollars, its first directors being R. S. Baker, Jotham Bixby, George S. Dodge, J. M. Griffith, Vincent A. Hoover, Jonathan S. Slauson and H. B. Tichenor, with J. M. Elliott as Cashier. Its first location was the room just rented by the Farmers & Merchants Bank adjoining the Bella Union, the County Bank's step in that direction being due, no doubt, to a benevolent desire to obtain some of its predecessor's business; and in July, 1878, it moved into the Temple & Workman banking-room, after the latter's failure. For a while the County Bank did both a commercial and a savings business; but later it forfeited the savings clause of its charter, and its capital was reduced to one hundred thousand dollars. In time, John E. Plater, a well-known Angeleño, became a controlling factor.

About the end of 1874, Edward F. Spence, who had come to California by way of the Nicaragua route a year earlier than myself, reached Los Angeles. In 1884, Spence was elected Mayor on the Republican ticket. In the course of time, he withdrew somewhat from activity in Los Angeles and became a heavy investor in property at Monrovia.

In 1874 or 1875, there appeared on the local scene a man who, like his second cousin, United States Senator Mallory of Florida, was destined to become a character of national renown; a man who as such could and, as a matter of fact, did serve his constituents faithfully and well. That man was Stephen M. White. He was born in San Francisco a few weeks before I saw that harbor city, and was, therefore, a Native Son, his parents having come to the Coast in 1849. While a youth, he was sent to Santa Clara where, in June, 1871, he graduated from the well-known college; he read law at Watsonville and later at Santa Cruz; and having been admitted to the Bar in 1874, he shortly afterward came to the Southland.

Arriving in Los Angeles, White studied law with John D. Bicknell, who afterward took him into partnership; and he soon proved to be a brilliant lawyer. He was also an orator of the first magnitude; and this combination of talent made him not only prominent here, but attracted great attention to him from beyond the confines of city and county. Standing as a Democrat in 1882, he was elected District Attorney by a large majority and in that capacity served with distinction, in the end declining renomination. In 1886 he was elected State Senator and soon became President of the Senate, and then acting Lieutenant Governor. After a phenomenal career both in his profession and in the public service—during which he was one of three counsel elected by the California Legislature to maintain the Scott Exclusion Act before the United States Supreme Court and thus conclude the controversy in the Chae Chan Ping case—he was elected to the United States Senate, and there, too, his integrity and ability shone resplendent.

The zeal with which White so successfully entered the conflict against C. P. Huntington in the selection of a harbor for Los Angeles was indefatigable; and the tremendous expenditures of the Southern Pacific in that competition, commanding the best of legal and scientific service and the most powerful influence, are all well known. Huntington built a wharf—four thousand six hundred feet long—at Port Los Angeles, northwest of Santa Monica, after having obtained control of the entire frontage; and it was to prevent a monopoly that White made so hard a fight in Congress in behalf of San Pedro. The virility of his repeated attacks, his freedom from all contaminating influence and his honesty of purpose—these are some of the elements that contributed so effectively to the final selection of San Pedro Harbor. On February 21st, 1901, Senator White died. While at his funeral, I remarked to General H. G. Otis, his friend and admirer, that a suitable monument to White's memory ought to be erected; and on December 11th, 1908, the statue in front of the County Courthouse was unveiled.[33]

Hotel competition was lively in 1874. Charles Knowlton concluded his advertisement of the Pico House with a large index-finger and the following assurance:

The unpleasant odor of gas has entirely disappeared since the building of the new sewer!

Hammel & Denker announced for the United States (commonly known as the U. S.):

We have all Spring Beds at this Hotel!

Fluhr & Gerson—the latter long a popular chap about town—claimed for the Lafayette:

The Eating Department will be conducted with especial care;

and this was some of the bait displayed by the Clarendon, formerly the Bella Union:

Carriages are kept standing at the door for the use of the guests, and every effort is being made by Col. B. L. Beal, the Present Manager, to render the guests comfortable and happy.

A couple of years later, the name of the Clarendon was changed to the St. Charles; next to which, during the Centennial year, the Grand Central, pretentious of name though small of dimension, opened with a splurge. Hammel & Denker continued to manage the United States Hotel. The Lafayette in time became, first the Cosmopolitan and then the St. Elmo.

Octavius Morgan, a native of the old cathedral town of Canterbury, England, came to Los Angeles in 1874 and associated himself with the architect, E. F. Keysor, the two forming the firm of Keysor & Morgan. They were charter members of the Southern California Architects Association, and for many years Morgan and his associates have largely influenced the architectural styles of Los Angeles.

A really picturesque old-timer even now at the age of nearly seventy, and one who, having withstood the lure of the modern automobile, is still daily driving a "one-hoss" buggy to the office of the Los Angeles Soap Company, is J. A. Forthman. In 1874, he brought a small stock of groceries from San Francisco and started a store at what is now Sixth and Olive streets; but at the end of three months, having sold out at a loss, he bought a quarter interest in a little soap plant conducted by C. W. Gibson. Soon thereafter, vats and fat were moved to their present site on First Street. In 1875, W. B. Bergin and in 1879, Gideon Le Sage joined Forthman and Gibson; and in 1887, the latter sold out to his associates. J. J., a brother of W. B. Bergin, was added to the force in 1895. For many years the concern dealt in hides, and this brought us into close business relations. I have referred to the death of four children. Edith, a child of six, was taken from us on October 15th, 1874.

While William F. Turner, son of the miller, was busy in his little store near the Puente Mills about three miles from El Monte, on the third of June, 1874, a Californian named Romo, who lived at Pio Pico's Ranchito, entered and bought some goods, also asking to be shown a pair of boots. Turner stooped to reach the articles, when the stranger drew a pruning-knife across his throat. In defense, the storekeeper caught hold of the sharp blade with both hands and thereby crippled himself for the rest of his days.

Turner had been in the habit of closing before dark on account of the rough element near by; and when he did not return home at the accustomed hour, Mrs. Turner, taking with her a little five-shooter, set out to find him and arrived in the midst of the murderous assault. Her pistol missed fire, but she succeeded in seizing the assassin and dragging him away from her husband; after which, the Mexican shot her just as Turner, bleeding, fell in the road. The explosion aroused a neighbor who reached the scene after Romo had fled with some boots—mostly for one foot!—and seventy dollars in cash.

When the news passed from mouth to mouth in El Monte, a posse started out to hunt for the Mexican; but after two days' unsuccessful search, they gave up the job. Then Fred Lambourn, who had a share in Turner's business, rushed in on Jake Schlesinger, shouting excitedly, "By God, Jake, I know where the fellow is!" and Jake and others responded by saddling their horses and hurrying to a rendezvous at Durfee's farm. The party of nineteen, including John Broaded and Bill Cooper, broke up into divisions of one or two and in time found themselves wading in and out of the San Gabriel River and the Puente Creek. Soon old Dodson spied their quarry floundering across stream; and when Schlesinger took a pop at him, the culprit cried out, "Don't shoot!" and agreed to come ashore. Of the money stolen, all but a few dollars was found on the prisoner; nevertheless, the captors told him that, as soon as Turner should identify him, he would be hung and that there was not much time for foolishness. Romo said that he had assaulted the storekeeper in order to get money with which, on the following Sunday, to marry; that his immediate need was a cigar; and that, if he must die, he would like to have his friends notified, that they might bury him. Jake handed the doomed man his only weed; and soon after, five or six masked men rode up and announced that they would care for the criminal. Then they drove under a tree on the bank of the river and there, in short order, the cutthroat was hanged.

Pio Pico soon heard of the lynching and sent Jake and the El Monte boys word that he would come over and "kill the whole damned lot" of them; in reply to which, El Monte forwarded to the last of the Mexican governors a cordial invitation to come, at the same time pledging to receive him in true California style—with due hospitality and warmth. This was contemporaneous with the Vasquez excitement, and Romo was probably bent on imitating the outlaw.

Until near the end of the seventies, there was very little done toward the laying of sewers, although the reader will remember that a private conveyor connected the Bella Union with the zanja running through Mellus's Row. Los Angeles Street from First to Second, in 1873, had one of brick and wood; and in 1875, a brick sewer was built from the corner of Main and Arcadia streets down to Winston and thence to Los Angeles Street. It must have been in the early seventies that a wooden sewer was constructed on Commercial Street from Los Angeles to Alameda, and another on New High Street for about one block. In 1879, one of brick was laid from Los Angeles and Commercial as far north as Arcadia, and connecting with the Main Street sewer. At about the same time, vitrified clay was used on a portion of Temple Street. My impression is that there was no cloaca laid on Spring Street until after 1880, while it was still later that Fort, Hill and Olive streets were served. As late as 1887, Hope Street had no sewer and very little conduit-building, if any, had been undertaken south of Seventh or west of Flower.

In January, 1875, the Commercial Bank, that was to change five years later into the First National, began business. Most of the incorporators were San Diego men—among them being Captain Henry Wilcox—although four—L. J. Rose, S. H. Mott, R. M. Town and Edward Bouton—were from Los Angeles. M. S. Patrick, of Chicago, was President; and Edward F. Spence was Cashier. Their room was on Main Street between Commercial and Requena. J. E. Hollenbeck, who was succeeded by Spence, was the first President of the National Bank. J. M. Elliott, made Cashier in 1885, has for years well filled the office of President. A pillar of strength in this institution is Vice-president Stoddard Jess.

Captain Wilcox, owner of the Colorado Steam Navigation Company, who finally sold out to the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, brought to California, on his own vessel in 1848, the first light-houses. He married Señorita María Antónia Arguello, the granddaughter of an early Governor of California. One of his daughters became the wife of Lieutenant Randolph Huntington Miner, and another married Lieutenant J. C. Drake. Captain Wilcox had induced E. F. Spence to come from San Diego to Los Angeles, and thereby gave a decided impetus to the starting of the Commercial Bank.

Milton Lindley, formerly an Indiana saddle-maker and Treasurer of Los Angeles County in 1879, arrived here in 1875, accompanied by Walter, the physician; Henry, the banker, who settled at Whittier; Albert, an attorney; and Miss Ida B., a teacher. In the eighties, he was twice Supervisor. Dr. Walter Lindley, once a Minnesota schoolmaster, so soon established himself that in 1878 he was elected health officer and, in 1880, a member of the Board of Education. The following year, he was President of the County Medical Society. With Dr. Widney, he contributed to the literature setting forth California's natural attractions; and with his brother-in-law, Dr. John R. Haynes, he took a leading part in organizing the California Hospital. Both Lindley and Haynes have identified themselves with many other important local institutions and movements.

Madame Caroline Severance, already distinguished as the founder, in 1868, of the first woman's club in America—the New England, of Boston—took up her residence in Los Angeles in 1875 and soon made her home, El Nido, the center of many notable sociological and philanthropic activities. Especially active was she in promoting the free kindergarten, working in coöperation with Mrs. Grover Cleveland and Kate Douglas Wiggin, the California author who was her protégée and resided for some time at El Nido when she was first becoming famous as a story-writer.

On March 27th, the Weekly Mirror was again enlarged and a subscription rate of one dollar a year was charged. By the beginning of 1876, a bindery was established in connection with the printery; and a Potter cylinder press—one of the first operated west of the Rockies—was installed.

E. J. Baldwin bought the Santa Anita rancho, in April, from H. Newmark & Company—a transaction recalled thirty-eight years later when, in 1913, the box which had been sealed and placed in the corner-stone of the Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church, at about the time of the sale, was brought forth from its long burial. Baldwin had just sold his controlling interest in the Ophir mine of the Comstock district for five million, five hundred thousand dollars. In the same year, we purchased of the Vejar estate the splendid vineyard of fifty acres commencing at Washington Street, on the south and a little east of Main Street, and taking in many important sections of to-day; selling it, in the early eighties, to Kaspare Cohn who, in turn, disposed of it during the boom of that decade. George Compère, somewhat noted as a local entomologist, cared for this vineyard while we owned it. Baldwin died on March 1st, 1909.

The sale of the Santa Anita is not without an incident or two, perhaps, of exceptional interest. On "Lucky" Baldwin's first visit, he offered us one hundred and fifty thousand dollars for the property; but learning that we wanted two hundred thousand dollars, he started off in a huff. Then Reuben Lloyd, the famous San Francisco attorney who accompanied him, said on reaching the sidewalk, "Lucky, go back and buy that ranch, or they'll raise the price on you!" and Baldwin returned, carrying under his arm a tin-box (containing several million dollars) from which he drew forth twelve thousand, five hundred, tendering the same as a first payment.

One can hardly refer to Baldwin without recalling H. A. Unruh, in the late sixties in the employ of the Central Pacific. It is my impression that I first met him at the Baldwin Hotel in San Francisco. This meeting may have occurred nearly thirty-five years ago; and after his removal to the Santa Anita Ranch, where he took charge of Baldwin's interests in the Southland, he transacted a large amount of business with H. Newmark & Co. In 1887, Unruh was also in partnership at La Puente with a man named Carroll, the firm advertising as "Agents for Baldwin's Grain Warehouse, Wells Fargo & Co.'s Express and Postmaster." When Baldwin died, his will named Unruh executor; Bradner W. Lee being the attorney.

Ravenna, on the Southern Pacific, was a town of the middle seventies, at whose start James O'Reilly, an Irishman of medium build, with reddish hair and a pug nose decidedly indented at the bridge, turned up with a happy-go-lucky air. Always slovenly, he wore a big, black slouch hat on the back of his head, as well as a good-natured expression, in days of prosperity, on his comical face. He had a grocery, famed for a conglomeration of merchandise not at all improved by age and hard usage; and this he sold to a none too fastidious clientele. He also cooked for himself, bragging that he was sufficiently adroit to throw a slapjack up the chimney and catch it in the pan, outside the shanty on its flop or turn! When Jim took to working a couple of claims known as the New York and Parnell Mines, his tribulations began: he spent more in the development of his property than he ever recovered, and claim-jumpers bothered him to death. In truth, once ascribing debatable motives to a man prowling there, he took aim at the intruder and—shot off an ear! Later, he married; but his wife soon divorced him. In time, his troubles affected his mind; and having lost everything and come to fancy himself an alchemist, he would sit for hours in the burning sun (his temples plastered with English mustard) industriously stirring a pestle and convinced that he could bring about a transmutation of the mortarful of mud. In the end, this good-natured Son of Erin was one day found dead in his little shanty.

J. A. Graves arrived in Los Angeles on June 5th and soon entered the office of Brunson & Eastman, lawyers. The following January he was admitted to practice before the Supreme Court and then became a member of the firm of Brunson, Eastman & Graves, dissolved in 1878. Practicing alone for a couple of years, Graves, in 1880, formed a partnership with J. S. Chapman. On the dissolution of this firm, in 1885, Graves joined, first H. W. O'Melveny and then J. H. Shankland; Graves, O'Melveny & Shankland continuing until January, 1904. On June 1st, 1903, Graves became Vice-president of the Farmers & Merchants National Bank. In the fall of 1879, the young attorney married Miss Alice H., daughter of J. M. Griffith, and for nine years they lived at the corner of Fort and Third streets. In 1888 they removed to Alhambra, where they still live. In 1912, Graves published some entertaining reminiscences entitled, Out of Doors California and Oregon.

Colonel W. E. Morford, a native of New Jersey and, late in the eighties, Superintendent of Streets, returned to Los Angeles in 1875, having previously been here. Morford had been assistant to Captain Sutter; and when he left San Francisco on March 14th, 1849, to return East, he carried the first gold taken from the diggings in the exciting era of 1848. This gold was sent by Frank Lemon, a member of Stevenson's Regiment, to his brother William, a partner of John Anderson, the New York tobacco merchant; and Morford liked to tell how, when the strange find was displayed on August 22d, in a little window of the well-known jewelry store of Benedict at 7 Wall Street near a high-hatted guard, the narrow thoroughfare was soon beyond hope of police control, thousands of curious, excited people struggling to get a glimpse of the California treasure.