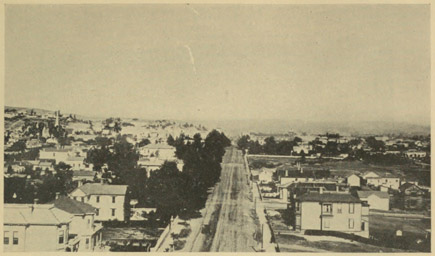

Main Street, Looking North from Sixth, Probably in the Late Seventies

In the height of the Winter season of 1881-82, when the semi-tropical glory of Southern California was most appealing, Helen Hunt Jackson, exploring the Southwest for materials of value in the study of the Indian, came to Los Angeles and met, as I have already related, Abbot Kinney, himself a student of the aborigines. She also met Don António F. and Doña Mariana Coronel; and finding in the latter a highly intelligent and affable lady, she passed some hours each day at the hospitable Coronel mansion, driving out there from her hotel and reclining under the broad palm trees. When Mrs. Jackson first came, with her pencils and note-books, the retiring Señora (as she used to tell me), having little comprehension of the Eastern lady's ambitious plans, looked with some suspicion on the motives of her enthusiastic visitor; but fortunately this half-distrust was dispelled by the warmth of the author's geniality, and Doña Mariana, opening both her house and heart, contributed inestimably to the success of the now famous Ramona, most of the rough notes for which were written at a little table on the Coronel veranda. On Doña Mariana's advice, Mrs. Jackson selected the Del Valle ranchhouse at the Camulos, as the best-preserved and most typical place for a background; although, disappointed in not finding the Del Valles at home, and consequently seeing the imagined headquarters of Ramona for but an hour or two, she was compelled to rely upon her Los Angeles hostess for many of the interesting and singularly accurate details. On departing from Southern California, Mrs. Jackson wrote for the Century Magazine a charming description of life at the old Coronel adobe, whence she never departed without a carriageful of luscious fruit. She also added her tribute to the attractions of the San Gabriel and San Fernando valleys. Now the world at large has been made more conversant with the poetical past of Los Angeles for the most part through the novel Ramona.

In 1882, the telephone was first introduced here, H. Newmark & Company so early subscribing for the service that they were given 'phone No. 5, the old River Station having No. But it may amuse the reader to know that this patronage was not pledged without some misgivings lest the customary noises around the store might interfere with hearing, and so render the curious instrument useless!

On January 20th, Don Juan Forster died at his Santa Margarita rancho, in San Diego County; followed to the grave but a few months later by Mrs. Forster, a sister of Pio Pico.

As rugged as the climate of his native State of Maine, A. T. Currier, after the usual hazardous life of the pioneer on the plains and in mines, proved his good judgment when, in the late sixties, after riding through California in search of the best place to found a home, he selected a ranch close to that of Louis Phillips. For years, I had pleasant relations with Currier; and I must confess that it was not easy to decide, in 1882, when two such friends as he and Billy Rowland were the opposing candidates, how I should vote for Sheriff. Currier was elected.

The Arroyo Vista—later and more correctly named the Vista del Arroyo—kept by Mrs. Emma C. Bangs, was the only hotel in the Pasadena settlement in 1882, and not infrequently passengers who journeyed there by the narrow, stuffy stage, running every day except Sunday, found on arriving that they could not be accommodated. So small, in fact, was the hostelry that it became necessary to advertise when all the rooms had been taken. The stage left for Los Angeles at nine o'clock in the morning and returned at three; and the driver, who was a student of the classics from the East, doled out to the passengers both crossroad data and bits of ancient lore.

Fire having destroyed the State Normal School at San José, in 1880, then the only institution of its kind in California, the Legislature, on March 14th, 1881, provided for the establishing here of a branch; and the following March George Gephard, a German who had come in 1875, raised eight thousand dollars to purchase the orange grove at Bellevue Terrace, near Fifth Street and Charity, for a site. On August 29th, 1882, the school was opened with Charles H. Allen of San Francisco as first Principal, two other teachers and sixty-one students. In 1883, Allen was succeeded by President Ira More and the school became an independent institution. Edward T. Pierce, who followed Professor More, retired in 1904. An instructor there for twenty-two years was Professor Melville Dozier, who made for California, by way of Panamá, in 1868. Largely through the devotion of these pioneer teachers, as well as through those qualities which have marked the administration of Dr. Jesse F. Millspaugh, scholar and pedagogue, for nearly the last decade, this Normal School has grown, each year, from a very humble beginning until now it sends out hundreds of men and women into one of the noblest of all professions.

A commencement of the Los Angeles High School of particular interest to me was celebrated in June in the old Turnverein Hall, on Spring Street—Superintendent James M. Guinn presenting the diplomas—when my daughter Ella graduated. Among her instructors had been Mrs. Chloe P. Jones, for three years Principal of the school and for one year Superintendent (having been the last incumbent, at the same time, of both offices), and the late Mrs. Anna Averill, a noted club woman. Mrs. Jones came to California from Ohio in 1873, taught for a while in Santa Rosa and, after a year of grade work here, began to instruct in the new high school; and there, after a service of nearly four decades, she is still a highly esteemed member of the staff. Mrs. Averill was the first woman to enter the Board of Education; and in her honor a bell was placed on the Mission Road, El Camino Real, to celebrate her seventieth birthday.

Colonel Harrison Gray Otis, who had been a farmer's boy, printer, Union soldier, foreman of the Government printing office, newspaper correspondent and editor, and had first visited Los Angeles late in 1874 or 1875 to familiarize himself with local conditions, on August 1st, 1882 joined the firm of Yarnell, Caystile & Mathes, thereupon assuming the management of both the Times and the weekly Mirror. In October, 1883, Yarnell and Mathes retired. A year later, the Times-Mirror Company was incorporated with a capital stock of forty thousand dollars.

Notwithstanding the failure of the Evening Republican, in 1878-79, Nathan Cole, Jr. started another afternoon daily, the Evening Telegram, on August 19th. It was very neatly printed; was delivered by carrier at sixty-five cents a month; and was a pioneer here in inserting free advertisements for those desiring situations.

In the spring of 1882, my attention had been called to the public need of proper facilities for obtaining a drink of good water; and no one else having moved in the matter, the following communication was sent, during the heated summer, to the City authorities:

Los Angeles,

August 25, 1882.

To the Honorable,

The Council of Los Angeles City:

Gentlemen:—

The undersigned hereby tender to the city a drinking fountain, as per the accompanying cut, to be placed on that portion of Temple Block fronting the junction of Main and Spring streets, for the free use of the public, and subject to the approval of your honorable body.

Respectfully,

H. Newmark & Co.

About the same time Stephen H. Mott, Secretary of the Los Angeles City Water Company, promised enough drinking water, free of charge, to supply the fountain.

The unpretentious gift having been accepted, the fountain was installed. The design included an iron pedestal and column, surmounted by a female figure of attractive proportions; while below, the water issued from the mouth of a lion's head. Though but seven feet in height and not to be compared with more ambitious designs seen here later, the fountain may have given some incentive to city service and adornment.

It has been shown that Remi Nadeau bought the southwest corner of Spring and First streets at what I then considered a ridiculously high price. On that site, in 1882, he commenced building the Hotel Nadeau—the first four-story structure in town. This fact is not likely to escape my memory, since he acquired the necessary funds out of the profit he made in a barley speculation involving the sale, by H. Newmark & Company, of some eighty thousand bags of this cereal; his gain representing our loss. It thus happened that I participated in the opening festivities (which began with a banquet and ended with a ball) to a greater extent than, I dare say, the average guest ever suspected. For many years thereafter, the Nadeau, now comparatively so deserted, was the center of social and business life in Los Angeles.

On October 11th occurred the death of Don Manuel Dominguez, his wife surviving him but a few months.

In 1882, F. H. Howland, representing the Brush Electric Lighting Company, made an energetic canvass in Los Angeles for the introduction of the electric light; and by the end of the third week in August, forty or more arc lamps had been ordered by business houses and private individuals. He soon proposed to light the city by seven towers or spliced masts—each about one hundred and fifty feet high—to be erected within an area bounded by the Plaza, Seventh, Charity and Main streets, and supplied from a power-house at the corner of Banning and Alameda streets. The seven masts were to cost seven thousand dollars a year, or somewhat more than was then being paid for gas. This proposition was accepted by the Council, popular opinion being that it was "the best advertisement that Los Angeles could have;" and when Howland, a week later, offered to add three or four masts, there was considerable satisfaction that Los Angeles was to be brought into the line of progress. On the evening of December 31st, the city was first lighted by electricity when Mayor Toberman touched the button that turned on the mysterious current. Howland was opposed by the gas company and by many who advanced the most ridiculous objections: electric light, it was claimed, attracted bugs, contributed to blindness and had a bad effect on—ladies' complexions!

In 1883, Herman Flatau came to Los Angeles from Berlin and soon entered the employ of H. Newmark & Company. His first duty was to bale hides; in a year, he was a porter in the grocery department; and by another year he had advanced to a place in the billing-office. Since then, he has risen step by step until he is now a stockholder in M. A. Newmark & Company and is taken into the most confidential and important councils of that firm. On the nineteenth of February, 1888, Flatau married Miss Fanny Bernstein, a lady distinguished as the first girl graduate of a Los Angeles high school to enter the State University, receiving therefrom the Ph.B. degree.

Dr. Elizabeth A. Follansbee registered in Los Angeles in February, 1883, and as one of the earliest women physicians here soon secured an enviable position in the professional world, being called to the chair for diseases of children in the College of Medicine of the University of Southern California.

J. W. Robinson in 1833 established a small dry goods shop at the corner of Temple and Spring streets, which he named the Boston Dry Goods Store.[36] A couple of years later he moved into the Jones Block opposite the Court House, the growth of his business having warranted such a change. In 1895 the block next to Blanchard Hall was built by this firm, and this he has occupied ever since. In March, 1896, the present manager, J. M. Schneider, became associated with the Boston Dry Goods Co., which was incorporated in 1891. N. B. Blackstone, a kinsman of Robinson, once in business with him, in time withdrew and set up for himself, under his own name, on Broadway.

One of the most shocking railroad accidents in the history of California blotted the calendar for January 20th, when over twenty persons were killed and sudden grief was brought to several happy Los Angeles circles. About three o'clock on a cold wintry night, an express train, bound south, stopped at the Teháchepi Station, near the summit; and while the engineer and fireman on the detached locomotive and tender were busy loading water and fuel, and the conductor was in the office making his report, the brakeman, with what proved to be uncalculating gallantry, was hastening to escort a young lady from the car to the railway station. In his hurry, he had forgotten to apply the brakes; and before he could return, the entire train, started by a heavy gale, had begun to move away—at the outset slowly, then dashing, with ever-increasing momentum, down the heavy mountain grade!

The conductor, upon leaving the depot, was the first to discover that the cars had started away; the disappearing lights having become so faint as to be scarcely visible. The passengers, too, had noticed nothing unusual until too late; when the train, plunging along at fearful velocity, leaped the track and fell in a heap to the ravine below. The old-fashioned lamps and stoves set fire to the débris; with the result that those who were not crushed were burned. The dead and wounded were brought to Los Angeles as quickly as possible; but the remains of some were never identified. Governor Downey, who was on the train, was rescued, though for years he suffered from the nervous shock; but among those lost was his charming wife.

Marshall & Henderson established themselves, in 1883, in the wholesale iron and wagon-supply trade; whereupon we sold that branch of our business to them. Shortly after, we vacated the storerooms in the Arcadia Block, which we had continuously occupied since the establishing of H. Newmark & Company in 1865, and moved to the two-story Amestoy Building on Los Angeles Street, north of Requena, but a few paces from the corner on which I had first clerked for my brother.

At a meeting in the office of the Los Angeles Produce Exchange, in the Arcadia Block on Los Angeles Street on March 9th, presided over by C. W. Gibson when J. Mills Davies acted as Secretary, the Board of Trade of Los Angeles was organized, M. Dodsworth, C. W. Gibson, A. Haas, J. M. Davies, Eugène Germain, J. J. Mellus, John R. Mathews, Walter S. Maxwell, I. N. Van Nuys and myself being the incorporators. Six directors—Gibson, Van Nuys, Haas, Dodsworth, Mathews and Newmark—were chosen. On March 14th, 1883, the Board was formally incorporated for fifty years. After a while the Board met in the Baker Block, and still later it assembled in a two-story brick structure at the northwest corner of Fort and First streets. In October, 1906, the Board of Trade and the Wholesalers' Board of Trade were consolidated, the new organization becoming known as the Wholesalers' Board of Trade. This move was initiated by Herman Flatau.

The republication, in the Los Angeles Express of March 23d, 1908, under the caption, "Twenty-five Years Ago To-day," of several paragraphs, savoring of village gossip such as the following—

Some very fine nugas [nougats?] are to be seen at Dol's Commercial Restaurant. They are meant for the silver-wedding feast at Mr. Newmark's—

calls to mind an event of March 21st, when my wife and I celebrated our silver wedding at our home on Fort Street. At half-past six in the evening, all of my employees sat down at dinner with us, having come in a body to tender their congratulations. A reunion of three generations of the Newmarks, some of whom then saw one another for the first time, came to a close a week or two later.

As the anniversary approached, I prepared a surprise for my wife, arranging that her brother, Abraham Newmark of St. Louis, should be present in Los Angeles for the occasion. His visit, however, had a grievous termination: while in San Francisco on his way home from Los Angeles, death came to him suddenly in the home of a friend.

In May, the Los Angeles Board of Education sold the northwest corner of Spring and Second streets—a lot one hundred and twenty by one hundred and sixty-five feet, where the City, in 1854, had built the first schoolhouse—to the city authorities for thirty-one thousand dollars; and the next year the Council erected on the inside sixty feet the first municipal building of consequence. When the Boom was at its height in 1887, the City sold the balance of the lot with its frontage on Spring Street and a depth of one hundred and five feet for one hundred and twenty thousand dollars, to John Bryson, Sr., an arrival of 1879 and ten years later Mayor of Los Angeles; and George H. Bonebrake (who came a year earlier than Bryson, and was in his day a prominent financier) opened, if my memory serves me correctly, the first agency for Eastern vehicles. Together, they built the Bryson Block.

This sale and purchase reminds me that when the lot was cleared to make way for the new City Hall, ten or twelve fine black locust trees were felled, much to the regret of many old-timers. These were the same shade trees for the preservation of which Billy McKee, the early schoolmaster, had risked bodily encounter with the irate waterman.

When the Board of Education sold this lot, it bought another, which extended from Fort Street to Spring between Fifth and Sixth streets and had a frontage of one hundred and twenty feet on each street. The price paid was twelve thousand five hundred dollars. This is the lot now known as Mercantile Place, whose retention or sale has been so much debated and which, with its many small stores, reminds the traveler not a little of those narrow but cosy, and often very prosperous, European streets and alleys on both sides lined with famous shops.

August 22d was the date of the City ordinance creating Elysian Park, the act leading the early settler back to pueblo days when the land in question passed from Mexican to American control and remained a part of the City lots, already described, and never subdivided and sold.

The last companies of volunteer firemen were organized in 1883, one being in the Morris Vineyard, a district between what is now Main, Hill, Fifteenth and Sixteenth streets, and the other in East Los Angeles, where a hose company was formed.

During September or October, a party of distinguished German bankers and statesmen, who had come to the United States to investigate certain branches of business, visited Los Angeles. The most important of this commission was Dr. Edward Lasker of the German Reichstag, other eminent members being Henry Villard, President of the Northern Pacific Railroad, and Judge Siemens, President of the German Bank of Berlin. A committee, consisting of I. W. Hellman, C. C. Lips, M. Morris, A. W. Edelman, Conrad Jacoby, Dr. Joseph Kurtz and myself took charge of these gentlemen, as well as a number of others, whose names I forget. Dr. Lasker, during his brief stay, accepted the hospitality of my home, and there received considerable honor at the hands of his German admirers, a large body of enthusiasts serenading him. Even while with us, it was evident that Dr. Lasker was an ailing man; and on the fifth of the following January, while riding in a carriage in Galveston, he suddenly died.

General George H. Stoneman, when he retired from the army in 1871, settled near San Gabriel; and continuing more or less in public life, he was elected in 1883 Governor of California.

In December, 1883, Eugene Meyer sold out to Nathan Cahn and Leon Loeb, his partners in the City of Paris store, and engaged in banking with Lazard Frères, in San Francisco, in which enterprise he continued until 1892, when he moved to New York and became one of the managing partners of the same institution in that city, retiring from active business nearly a decade later.

When Meyer left, he sold his home on Fort Street, which had originally cost him six thousand, to Moses L. Wicks for sixteen thousand dollars; and his friends told him that so successful a sale proved the Meyer luck. Wicks in time resold it to John D. Bicknell, whose heirs still own it.

With the coming at Christmas in 1883 of Robert N. Bulla, began a career that has made itself felt in local legal, political, commercial, social and scientific circles. In 1884, he joined the law firm of Bicknell & White; nine years later, he was representing his district in the State Assembly; in 1897, he was a State Senator; and his efficient activity as a director of the Chamber of Commerce, together with his forensic talent, lead one to anticipate his rise to further distinction in that body. As a director of the Southwest Museum, Bulla performs another of his services to the community.

After an unsuccessful canvass made by Judge Noah Levering, which resulted in the attendance of just four persons, the Historical Society of Southern California was finally organized at meetings in Temple Block, in November and December, 1883. J. J. Warner was the first President; H. D. Barrows, A. F. Coronel, J. G. Downey and John Mansfield, the Vice-Presidents; J. M. Guinn, Treasurer; and C. N. Wilson, Secretary. For a time, the Society's meetings were held in the City Council room, after that in the County Court room; and later at the houses of the members. On February 12th, 1891, the Society was incorporated.

Le Progrès, a seven-column paper, was started here, in 1883, as the organ of the French population, some rather prominent citizens of Gallic origin becoming the stockholders. Dr. Pigné du Puytren was the first editor, and he was succeeded, in a year or two, by Georges Le Mésnager, the wine-grower.

On February 18th, another flood of unusual proportions, continuing until May, devastated the Southland. Following several days of heavy rain, the river rose and fifty houses and large sections of vineyards and orchards in the low-lying portions of the city were carried away by the mad waters; several lives being lost. In that year, the Santa Ana cut its new channel to the sea, deviating from the old course from one to three miles, but still holding to the southwest, a direction apparently characteristic of rivers in this vicinity.

Speaking of rains, reminds me that, in 1884, one of the difficulties in the way of solving the water problem was removed in the purchase, by the City of Los Angeles, for fifty thousand dollars, of Colonel Griffith J. Griffith's right to the water of the Los Angeles River.

Charles F. Lummis, long a distinguished and always a picturesquely-recognizable resident, walked across the continent "for fun and study," from Cincinnati to Los Angeles, by a roundabout route of 3507 miles in one hundred and forty-three days, in 1884, having made an arrangement with the Los Angeles Times to which he contributed breezy letters on the way. The day after his arrival he became city editor of that newspaper, and in the last Apache campaign, in 1886, he was its war correspondent. In 1887 a stroke of paralysis sent him to New Mexico; and recovering, he spent several years exploring and studying Spanish-America from Colorado to Chile, becoming acknowledged here and abroad as an authority on the history and the peoples of the lands he visited. In 1893, returning from Peru, he edited for a dozen years the Land of Sunshine magazine (later Out West); after that founding the Landmarks Club to which we owe the preservation, from utter ruin, of several of the old Missions. This club has lately been reorganized to care for all of the twenty-one Missions of the State. Later Lummis incorporated the Sequoya League which has so much bettered the condition of thousands of California Indians—securing, in particular, for the evicted Warner's Ranch Indians a better reservation than that from which they were driven. From 1905 to 1911 he was Librarian of the Los Angeles Public Library. In 1903 he founded the Southwest Society of the Archæological Institute of America which conducted many scientific expeditions in Arizona, New Mexico and Guatemala, acquired valuable collections and maintained the first free public exhibits of science in Southern California. In 1907 he and others incorporated the Southwest Museum, whereupon the Society conveyed to it all its collections, a twenty-acre site and the fifty thousand dollars bequeathed by Mrs. Carrie M. Jones for the first buildings. Besides other and many literary activities, Lummis has published over a dozen notable books on the Southwest and Spanish America.[37] Clad in corduroys from Barcelona—coat and trousers, with very wide wales, of olive or green—wearing no vest, but having a shirt of heavy drawn-work of the Pueblo Indians (with whom he dwelt six years), a red-and-white faja or waist-band made by the same people, and a grey sombrero banded with Mexican braided horse-hair, Lummis roams the desert or is welcome at the most exclusive functions; having already been a guest many times at the White House and the palaces of Diaz and other presidents in Spanish America. "I don't change my face for company," he says, "then why my garb—so long as both are clean?" An interesting figure at scientific meetings and on the lecture platform, Lummis is equally so at home where, after twenty years' work with his own hands, he is still building his stone "castle," El Alisal; and as his house is a rendezvous for artists, musicians, authors and scientists, his guests often find him toiling as either carpenter or mason. The Alisal, by the way, is built around the huge sycamore under which Greek George camped with his camels on his first arrival in Los Angeles nearly sixty years ago.

In 1884, Colonel H. Z. Osborne—always a foremost citizen of the town and in 1912 a most energetic President of the Chamber of Commerce—and E. R. Cleveland bought the Express; and two years later they organized the Evening Express Company, J. Mills Davies, once Secretary of the Board of Trade, becoming business manager. In 1897, Colonel Osborne was appointed United States Marshal for the Southern California District, whereupon Charles Dwight Willard became general manager of the paper, to be succeeded by J. B. Abell. For a short time in 1900, the Express fell into the hands of a group of men, of whom John M. Miller acted as President and Richard Beebe served as Secretary.

O. W. Childs opened his new theater known as Childs' Opera House, on Main Street south of First, in what was then the center of the city, on May 24th, when the School for Scandal was given, Mlle. Rhea taking the leading part. This, the first theater of real consequence built in Los Angeles, had a seating capacity of eighteen hundred; and for some time, at least, an entertainment was booked there for every night of the week. Frequently, too, whenever anything of moment was going to happen there, Childs sent me an invitation to occupy his private box.

An interesting personality for many years was C. P. Switzer, a Virginian, who came in 1853 with Colonel Hollister, W. H. Perry and others. Switzer became a contractor and builder; but in 1884, in search of health, he moved to an eminence in the Sierras, where he soon established Switzer's Camp, which gradually became famous as a resort generally reached on burros. A few years ago, "Commodore" Switzer—or Sweitzer as he was also called—retired, but the camp, more than ever popular, has been continued as "Switzer's."

Toward the middle of the eighties, excitement among citrus growers throughout Southern California gave way to deep depression due to the continued ravages of the fluted scale, a persistent insect whose home, according to research, is Australia, and which had found its way, on Australian plants (and especially on Acacia latifolia) into South Africa, New Zealand and California, arriving on the Pacific Coast about 1868. This particular species, known to the scientist as the Icerya purchasi, resisted and survived all insecticide sprayings, washes and fumigation, and for a while it seemed that one of the most important and growing industries of the Southland was absolutely doomed. Indeed, not until 1889, when the result of Albert Koebele's mission to Australia, as a representative of the Department of Agriculture, was made known, did hope among the citrus orchardists revive. In that year, the tiny ladybird—styled by the learned the Novius cardinalis, but more popularly spoken of as the ladybug—the most effective enemy of the fluted scale, was introduced here, the Government establishing, among other stations, an experimental laboratory on the Wolfskill ranch under the charge of Professor D. W. Coquillett; and so rapidly was this tiny favorite of children propagated and disseminated, that the dreaded scale was exterminated and the crops were saved. Wolfskill, by the way, though he fought hard with the assistance of his foreman, Alexander Craw, to save his noted trees, lacked the coöperation of his neighbors; and the injury then inflicted largely influenced him to subdivide his famous citrus property.

With the arrival on March 1st, 1887, of J. O. Koepfli, a man came on the scene who during the next twenty-five years was to be not only one of the real forces in the development of the city, but, as a whole-souled gentleman, was to surround himself, through his attractive personality, with a large circle of representative and influential friends. As President of the Merchants' Association, his record was such that in 1896 he was elected a director of the Chamber of Commerce where, during twelve years, he performed valiant service on all the important committees. His work in behalf of the harbor and the Owens River aqueduct is especially memorable. He was President of the Chamber in 1905 and 1906. With such men as C. D. Willard and R. W. Burnham, he founded the Municipal League, whose President he was for seven years. His efforts were always free from the taint of personal aggrandizement, and he thus had the public confidence. He is a member of the well-known firm of Bishop & Company.

Among the present social organizations of the city, the Los Angeles Athletic Club takes second place in point of age. It was organized in 1879 by forty young men, among whom were Fred Wood, Bradner W. Lee, Mark G. Jones, Frank M. Coulter, Frank A. Gibson, John S. Thayer, M. H. Newmark, W. G. Kerckhoff, Alfredo Solano, J. B. Lankershim, W. M. Caswell, James C. Kays, Joseph Binford, and Samuel Dewey. The initial meeting took place in Wood's office in the McDonald Block, and a hall in the Arcadia Building was the Club's earliest headquarters. J. B. Lankershim was the first President. A few years later, the Club moved to the Downey Block; and there the boys had many a merry bout. In the course of time, the gymnasium was located on Spring Street, between Fourth and Fifth; now it occupies its own spacious and elaborate building on Seventh Street, at the corner of Olive, the Club's quarters being among the finest of their kind in America.

Ten or twelve months after the starting of the first cable railway here, Los Angeles, in 1885, resumed the march of progress, this time with an electric street car line. Poles—with huge arms stretching out into the middle of the street and often spoken of derisively as gallows-poles—and wires were strung along Los Angeles and San Pedro streets, down Maple Avenue to Pico Street and thence westward to what was known as the Electric Homestead Tract, just outside of the city limits. A company owned much land not likely to be sold in a hurry, and to exploit the same rapidly, the owners built the road. F. H. Howland, who introduced the electric light here, was a prime mover in this project, but ill fortune attended his efforts and he died a poor man.

On January 11th, my wife and I left for a trip to the City of Mexico, where we spent four or five days and were pleasantly entertained, before going to the New Orleans Exposition, by our old friend, Judge Ygnácio Sepúlveda and his wife. Previous to crossing the border, we stored our trunks in El Paso and received them upon our return, strapped as before. Some valuables, however, which I had hidden away in the linen were missing when I reopened the trunk, and have never been recovered. Among other companions on this outing were Fred, son of J. M. Griffith, and James S., son of Jonathan S. Slauson. By the bye, James himself has had an honorable public career, having served in one of his activities as President of the Chamber of Commerce.

Early in March, I believe, sewing was first introduced into the public schools of Los Angeles, the Board of Education consenting to it only as an experiment.

Two celebrities divided the honors in the spring and summer in local circles: United States Senator John Sherman, who visited Los Angeles on May 8th, 1885, and Sir Arthur Sullivan, the distinguished English composer, of Pinafore and Mikado fame, who tarried near the ocean in the hot days of August.

About 1885, a Dr. Sketchley, who enjoyed some reputation for his work in the natural history field and had been a traveler through many remote countries, brought to Los Angeles quite a collection of ostriches and opened, about where Tropico lies, an amusement resort known as "The Ostrich Farm." Having provided a coach to connect with the end of the Temple Street cable cars and advertised the strange peculiarities of his finely-feathered animals, the Doctor soon did a thriving business, notwithstanding the task of caring for the birds in their new environment. Later, Sketchley removed from Los Angeles to Red Bluff; but there he failed and lost all that he had.

Soon after Dr. Sketchley arrived here with his ostriches and three or four men and one woman from Madras, Edwin Cawston, an Englishman now retired and living in Surrey, happening (while on a tour through America) to glance at an article in Harper's Magazine pointing out the possibilities of successfully raising ostriches, returned to London, secured the necessary capital and in 1887 began shipping these camel-birds from South Africa to Los Angeles. Many of the easily-affected creatures died at sea; yet forty, as good luck would have it, survived, and with them Cawston and a partner named Fox opened a second "ostrich farm" at Washington Gardens. In time, Cawston transferred his establishment to La Habra, associating with himself E. H. Rydall as publicity agent; and in 1908 the Cawston Ostrich Farm, between Los Angeles and Pasadena, was incorporated.

Quite naturally with the advent of the settler from the East and the Middle West, the zanjas, in early years so serviceable both for domestic and irrigation purposes and, therefore, more or less venerable, came to be looked upon as mere surface-conveyers and public nuisances; a sign, in 1883, at the corner of Sixth and Olive streets warning teamsters against crossing the ditch. By 1885, such opposition had developed that most of the zanjas were condemned, the one extending from Requena Street to Adams via Figueroa being, if I am right, one of the last that was buried from view.

For some time, East Los Angeles maintained its character as a village or small town, and in 1885 the East Side Champion, started and edited by Edward A. Weed, voiced the community's interests.

This year was marked by the demise of a number of well-known Angeleños. On the second of March, John Schumacher, a man esteemed and beloved by many, died here of apoplexy, in the seventieth year of his age. Six days later, General Phineas Banning, who had been sick for several months, expired at San Francisco, his wife and daughters being with him; and on March 12th, he was buried in Rosedale Cemetery. In his declining years, illness often compelled General Banning to remain at home in Wilmington; and when needing the services of his physician, Dr. Joseph Kurtz, he would send a locomotive to fetch him. On June 5th, Dr. Vincent Gelcich, the pioneer surgeon, died here at the age of fifty-six years.

In 1885, the first medical school in Los Angeles was founded in the house once occupied by Vaché Frères, the wine-makers, on Aliso Street between Lyons and Center. For years the school was conducted as a part of the University of Southern California, and Dr. J. P. Widney was Dean.

In the fall of 1885 Dr. M. Dorothea Lummis, a graduate in medicine of the Boston University, settled in Los Angeles and in time became President of the Los Angeles County Homeopathic Medical Society. Distinguished in her profession, Dr. Lummis became a leader in humane endeavor, reorganizing here the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and founding the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

The first train of the Santa Fé Railroad to enter the city of Los Angeles ran from Colton over the rails of the Southern Pacific, on November 29th, the two corporations having come to an agreement to use the one set of tracks until the spring of 1887, when the Santa Fé finished building from San Bernardino to its junction with the Los Angeles & San Gabriel Valley Railroad. The locomotive bore the name, L. Severy—a prominent director in the Company, and the father of the well-known resident of Pasadena—and the number 354.

After twenty years' association with the wholesale grocery business, I withdrew, on December 5th, 1885, from H. Newmark & Company, and on that day the business was absorbed by M. A. Newmark, M. H. Newmark, Max Cohn and Carl Seligman, and continued as M. A. Newmark & Company. This gave me the opportunity of renewing my association with one of my earliest partners, Kaspare Cohn, the new firm becoming K. Cohn & Company; and the change in my activities found me once again shipping hides and wool.

Looking through the haze of years, many are the recollections—often vague, it is true—of those with whom I had business relations. In the picturesque adobe days, the majority of my customers were simple-mannered natives such as Manuel Carizosa, on South Alameda Street; José María Dávila, in Sonora Town next door to José María Fuentes, his competitor; and M. G. Santa Cruz, in the same district. Jordan Brothers, Americans, kept store on Aliso Street opposite the Aliso Mill, and G. Ginnochio, father-in-law of James Castruccio, on Macy Street, near the river; while Bernardino Guirado, Mrs. John G. Downey's brother, and Max Schwed supplied the wants of Los Nietos. J. B. Savarots, who went to South America when he sold out to J. Salaberri & Company—a firm composed of two Basques, Juan Salaberri and Domingo Oyharzabel—was in general merchandise in San Juan Capistrano. Hippolyte Cahen (whose widow is a member of the Lazarus Stationery Company,) had an up-to-date general store at Anaheim; and Simon Cahen, son-in-law of Bernard Cohn, was similarly occupied in the Azusa district. Others of about the same period, were Dominico Rivara, who established himself on Main Street near Commercial, shortly to be succeeded by Vignolo & Sanguinetti, in whose store—known as La Esperanza and near Castruccio Brothers' La Mariposa—Jim Moiso bought an interest. Two more Main Street merchants were A. C. Chauvin, who conducted his El Dorado Store in the Lanfranco Building, and his neighbor, Joe Lazarowich. And near them Francisco Vassallo had his little fruit stand. The erratic Lucas Sciscisch, who terminated his life as a suicide, attended diligently to business on First Street, near Los Angeles; and not so very far away Thomas Strohm was laying the foundation, in his grocery trade, for that popularity which caused him, in the eighties, to be chosen Chief of the Fire Department. António Valle, who built on the northeast corner of First and Los Angeles streets (calling the block in honor of his five sons, the Five Brothers), for a number of years had a grocery store on Main Street near Requena and not far from the butcher shop of Vickery & Hinds.

In view of the ravages of time among the ranks of these old-timers, it is a satisfaction to observe that at least some of those who were active before I retired are still in the trade. The first-comer was George A. Ralphs, who, reaching Los Angeles as a boy, learned brick-masonry and was known as the Champion Bricklayer of California until, while on a hunting expedition, he lost an arm.[38] With a man named Francis, he started, in 1877, the Ralphs & Francis Grocery, on the old Georgetown corner. This was the beginning of the Ralphs Grocery Company. In February, 1882, Hans Jevne, a Norwegian by birth, who had been associated with his brother in Chicago, came to Los Angeles, and a few months later he opened a small grocery store in the Strelitz Block at 38 and 40 North Spring Street. In less than no time, so to speak, the good housewives of the town were able to secure the rarest tidbits from all the markets of the world; and not only that, but Jevne, since his advent here, has been identified with most important steps in the evolution of the city. W. F. Ball for thirty years or more has been a tobacconist, and for thirty years, or somewhat less, has occupied the same premises on Spring Street, north of First. The Williams family came from England in 1882, and George soon established his grocery business out in what was then known as the University district, where he bought a block of land. George has given of his time for the public weal, having been for several terms a City Councilman. Another Los Angeles merchant who has attained success is Albert Cohn; and while his start in life, in an independent career, began a couple of years after my retirement, he had been in my employ as a clerk almost from the time of his arrival, in 1882. Marius Bellue has been located on South Alameda Street so long that it seems as though he must have arrived here in the Year One.

So much for the merchants of the city; among such tradesmen in the districts outside of Los Angeles, I can recall but three active in my day and still active in this. Alphonse Weil, a native of the sunny slopes of France, has grown up with the town of Bakersfield. John R. Newberry opened his doors in 1882, and, after moving to Los Angeles in 1893, commenced that meteoric career, during which he established stores throughout Los Angeles and its suburbs. George A. Edgar, about thirty-one years ago, brought a stock of groceries and crockery to Santa Ana and deposited the contents of his cases in the same location, and on the same shelves, from which he still caters to his neighbors.

The great flood of 1886 reached its first serious state on January 19th. All of Los Angeles between Wilmington Street and the hills on the east side was inundated; levees were carried off as if they were so much loose sand and stubble; and for two or three weeks railway communication with the outside world was impossible.

During this inundation on January 19th, Martin G. Aguirre, who was a deputy under Sheriff George E. Gard, gave an exhibition of great courage. So rapidly had the waters risen that many persons were marooned; and it was only by throwing himself on the back of his favorite horse that Aguirre, at very great risk, rescued twenty or more people from drowning, the number including many children. In the last attempt, Aguirre nearly lost his own life. Somewhat of a hero, in November, 1888, he was elected Sheriff, defeating Tom Rowan for that office.

Rebecca Lee Dorsey, another of the early women practitioners of medicine, came to Los Angeles in January, 1886, a graduate both of Eastern colleges and of a leading Vienna hospital. Peddling vegetables as a child, later working as a servant and hiring out as a nurse while finishing her course in Europe, Dr. Dorsey was of a type frequently found among the early builders of the Southwest.

Largely to a board of Commissioners, consisting of Mayor E. F. Spence, H. Sinsabaugh and the ever-ready Jake Kuhrts, appointed in 1886 when provision was made for a paid fire department, is due the honor of having successfully arranged the present excellent system in Los Angeles.

It was in 1886 that we bought the Repetto rancho, under circumstances of such interest that it may be well to tell something about the owner and his connections. Alessandro Repetto was an Italian of such immense size that he was compelled, when standing, to shift the weight of his body from one leg to the other. He was miserly in the extreme, but this was compensated for by his honesty and uprightness of character. He was also far from being neat, and I remember the way in which he dispensed hospitality when I visited his ranch to buy wool. He would bring out some very ordinary wine and, before serving it, would rinse out the glasses with his fat fingers; and it was courtesy alone that prompted me to partake of what he offered. He lived on his ranch, but when attacked by his last illness, he took a room at the New Arlington Hotel, formerly the White House, on the southeast corner of Commercial and Los Angeles streets.

There, finding him alone and neglected, I advised him to go to the Sisters' Hospital on Ann Street; but the change did not save him and after a few days he died. A fellow Italian named Scotti, a knave of a chap who was with him in his last moments, knowing that I was Repetto's executor, soon brought to my house a lot of papers which he had taken from the dead man's pockets.

Repetto being a recluse somewhat on the misanthropic order, I had difficulty in getting pallbearers for his funeral, one of my applications being to James Castruccio, President of the Italian Benevolent Society and then Italian Consul, who said that Repetto had never helped anyone, but that if I would give, in his name, five hundred dollars to charity, the attendants would be supplied. To this I demurred, because Repetto had made no such provision in his will; and Castruccio giving me no satisfaction, I went to Father Peter, explained to him that Repetto had bequeathed six thousand dollars to the Church, and stated my needs; whereupon Father Peter arranged for the bearers. All the provisions for the funeral having been settled, I cabled to his brother and heir, then living in the mountains near Genoa, whose address I had obtained from Castruccio. Repetto had really hated this brother and, in consequence, he had very unwillingly bequeathed him his large estate.

In due season, the brother, a hunchback, appeared on deck as an intimate with Scotti, and I found him to be an uncouth, ignorant fellow and a man who had probably never handled a ten-dollar gold piece or its equivalent in his life. He had on shoes that an elephant might have worn, a common, corduroy suit, a battered hat and plenty of dirt. Wishing to take him to Stephen M. White, my lawyer, I advised the purchase of new clothes; but in this, as in other matters, I appealed in vain. So miserly was he indeed, that one day, having purchased a five-cent loaf of bread in Sonora Town, he was seen to hide himself behind a building while he ate it, doubtless fearful lest someone might ask him for a bite.

Alessandro Repetto had lived with an Indian woman by whom he had a son; and a Los Angeles attorney soon had himself appointed guardian, declaring that the property belonged, not to the brother, but to the boy. This, because the woman had never left her husband, was blackmail, pure and simple; besides Repetto had willed the lad some property in San Gabriel. Stephen M. White was the attorney for the estate; but when this lawsuit started, Scotti advised the unsophisticated brother to take other lawyers. Two men, accordingly, one named Robarts and the other Jim Howard, suddenly appeared at the trial; and when I asked why they were there, they replied that they had been engaged by Repetto's brother. Four hundred and seventy-five dollars settled this extortion, the lawyers taking all but twenty-five dollars, which was paid to the mother of the boy.

Early in the morning, a few days later—either on Christmas or New Year's—there was a knock at my door; and when the girl answered the call, the Sheriff was found there with the interesting news that Repetto had been arrested and that he wished me to bail him out! I learned that Robarts and Howard had presented him with a bill for three thousand five hundred dollars, for services; and that, since the money was not immediately forthcoming, they had trumped up some sort of a charge and had had the foreigner incarcerated. White advised a settlement, and after much difficulty we succeeded in having their bill reduced to three thousand dollars, which we paid.

Repetto's troubles now seemed at an end; but just as he was ready to leave for Italy, Scotti put in an appearance with a claim for benefits bestowed, which the much-fleeced Italian refused to pay. Scotti, knowing along which road the unfortunate man would travel, was early at San Gabriel with the Sheriff, to intercept Repetto and return him to limbo; and the Genoese being brought back, he again appealed to me. It was now my turn, as executor, to have an interesting inning with Scotti. While I was settling the estate, I was made aware that Repetto had loaned another Italian named G. Bernero, on his note, some three thousand dollars; but this document I missed, and it was only by accident that I traced it to Scotti. He had abstracted it from the papers found in Repetto's pocket, carried it to the borrower, and sold it back to him, for four hundred dollars! I recovered this note and collected the balance due; nevertheless, when Scotti had Repetto arrested, I threatened the former with prosecution on the charge of stealing and selling the note, with the result that Scotti did not press his suit and Repetto was released.

In connection with this move by Scotti, Robarts and Howard reappeared to defend Repetto, notwithstanding his previous announcement that he would have nothing more to do with them; and to bolster up their claim, they drew forth a paper certifying that Repetto had engaged them to attend to any law business he might have while he was in this country! Repetto, now really alarmed, once more quickly settled; but the crafty Robarts and Howard had another bill up their sleeves, this time for three or four thousand dollars, and poor Repetto was obliged to pay that, too!

Kaspare Cohn, J. D. Bicknell, I. W. Hellman and S. M. White, in conjunction with myself, bought the Repetto Ranch from the brother, before he left for Italy, for sixty thousand dollars. All in all, the heir, who survived the date of his windfall but a few years, carried away with him the snug sum of one hundred thousand dollars.

This fine domain, lying between Whittier and Los Angeles, was apportioned long before 1899, among the five purchasers. In that year, Kaspare Cohn and I, on the advice of William Mulholland, developed water on our undivided share, meeting with as great a success as has attended all of the operations of that eminent engineer. After an abundance of water was secured, we sold the property in five-acre and smaller lots, locating the town site of Newmark near the tracks of the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad, and naming the entire settlement Montebello.

It was in the spring of 1886 that Colonel H. H. Boyce, who had been business manager of the Times-Mirror Company, was bought out by Colonel H. G. Otis and became editor-in-chief and general manager of the Los Angeles Tribune, conducting the paper, during his short association, with some vigor.

One more reference to the Times-Mirror publishing house. On April 8th, the company was reorganized, with Colonel H. G. Otis as President and General Manager, Albert McFarland as Vice-President and Treasurer and William A. Spalding as Secretary. About the middle of July, the company bought the corner of Fort and First streets, and in the following May moved to its new home erected there. On February 1st, 1887, the Times began to appear seven days in the week.

After grinding away for ten years as the sole owner of the Los Angeles Herald, J. D. Lynch, in 1886, took into partnership his former associate, James J. Ayers, and once more the alliance of these puissant forces made of the paper a formidable bulwark for the Democracy.

Colonel John Franklin, or plain J. F. Godfrey as he was known in those days, was rather a prominent attorney in his time; and I knew him very well. About 1886, as chairman of a Democratic committee, he headed the delegation that invited me to become a candidate for Mayor of Los Angeles; but a contemplated European trip compelled me to decline the honor.

In the spring of 1886, a falling out between the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fé railroads brought on a rate-war, disastrous enough to those companies but productive of great benefit to Los Angeles. Round-trip tickets from points as far east as the Missouri River were hammered down to fifteen dollars, and for a few days, Charley White (who then conducted the Southern Pacific office in the Baker Block, and had full authority to make new fares) defied the rival road by establishing a tourist rate of just one dollar! When normality again prevailed, the fare was advanced to fifty dollars for first-class passage and forty dollars for second-class. The low rate during the fight encouraged thousands of Easterners to visit the Coast, and in the end many sacrificed their return coupons and settled here; while others returned to their Eastern homes only to prepare for permanent removal West. In a sense, therefore, this railroad war contributed to the Boom of a year or two later.

Freight as well as passenger rates were slashed during this spasmodic contest, and it was then that the ridiculous charge of one dollar per ton permitted me to bring in by rail, from Chicago, several carloads of coal, which I distributed among my children. Such an opportunity will probably never again present itself to Los Angeles.

Another interesting shipment was that of a carload of willow-ware from New York, the freight-bill for which amounted to eight dollars and thirty-five cents. These goods ordinarily bear a very high tariff; but competition had hammered everything down to a single classification and rate. I remember, also, that M. A. Newmark & Company brought from New York a train-load of Liverpool salt, then a staple commodity here, paying a rate of sixty cents per ton.

Stimulated, perhaps, through the setting aside of Elysian Park by the City Council, another pleasure-ground, then known as East Los Angeles Park, was assured to the public toward the middle of the eighties; the municipal authorities at the same time spending about five thousand dollars to improve the Plaza, one of the striking features of which was a circular row of evergreens uniformly trimmed to a conical shape.

On October 14th, H. T. Payne and Edward Records published the initial number of the Los Angeles Tribune, this being the first newspaper here to appear seven days in the week. The following January, a company was incorporated and for years the Tribune was well maintained.

Charles Frederick Holder, the distinguished naturalist, came to California in search of health,[39] in 1886, and settled in Pasadena, where he was appointed Professor of Zoölogy in the Throop Institute. An enthusiastic admirer of the Southland and an early explorer of its islands and mountain ranges, Professor Holder has devoted much attention to Pasadena and the neighboring coast. As early as 1891, he published Antiquities of Catalina; later he wrote his spirited Southern California book on Life and Sport in the Open; and with his gift for popularizing, probably no other scientific writer has contributed more to make known, both in America and abroad, this attractive portion of our great State.

Prudent and Victor Beaudry bought considerable land on the west side of New High Street, probably in 1887, including the site of one of the old calabozos; and as some of the purchase was a hill, he spent about one hundred thousand dollars grading the property, excavating fifty thousand or more cubic feet of earth and building the great retaining wall, finished in 1888, four hundred and sixty-five feet long and fifty feet high, and containing two hundred thousand cubic feet of stone. When he was ready, Beaudry began to advertise the superior merits of his land; and I still have in my possession one of the flaring circulars, printed in red ink, including such headlines as these: