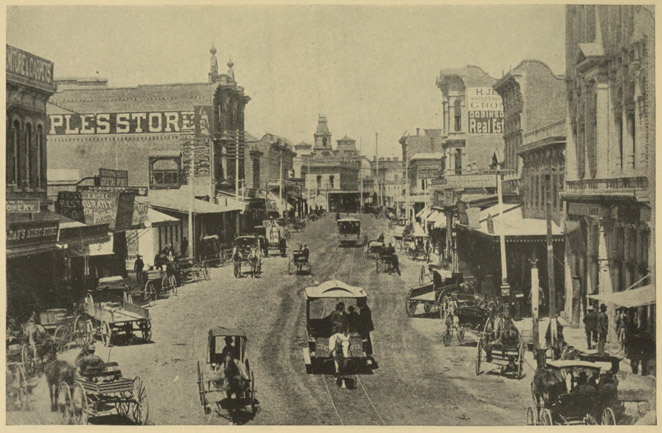

Spring Street, Looking North from First, about 1885

NOW IS THE TIME!

DON'T SHUT YOUR EYES AND TURN YOUR BACK!

and the following:

Have a Home on the Hills! Stop paying rent in the Valleys! View from your own home the broad Pacific, the green hills and the model city! Best water supply. Drainage perfect. Best sunny exposures. Pure air, and away from fogs!

Have a Home on the line of the great Cable Railway system!

Mark your Catalogue before the day of sale!

February 15, 16 and 17, at 10 o'clock each Day.

Bear in mind that this property is on the HILLS, and on the line of the Cable Railway System! No such opportunity has ever been offered to the people of Southern California. Public School and Young Ladies' Seminary in the immediate vicinity.

Four years after he had built the Nadeau Block, Remi Nadeau died here, at the age of sixty-eight, on January 15th. The same month, another man of marked enterprise, Llewellyn J., brother of Reese and William Llewellyn, founded the Llewellyn Iron Works, attaining a success and fame very natural considering that the Llewellyns' father, David, and uncle, Reese before them had acquired a reputation as ironworkers both in Wales and San Francisco.

In January, Fred W. Beau de Zart and John G. Hunsicker established The Weekly Directory, whose title was soon changed to that of The Commercial Bulletin. Under the able editorship of Preston McKinney, the Bulletin is still fulfilling its mission.

Phineas, son of J. P. Newmark, my brother, came to Los Angeles in 1887 and associated himself with M. A. Newmark & Company. In July, 1894, he bought out the Southern California Coffee and Spice Mills, and in the following September, his younger brother, Samuel M. Newmark, also came to Los Angeles and joined him under the title of Newmark Brothers. On December 26th, 1910, the city suffered a sad loss in the untimely death of the elder brother. Sam's virility has been amply shown in his career as a business man and in his activity as a member of the Municipal League directorate.

Among the hotels of the late eighties were the Belmont and the Bellevue Terrace, both frame buildings. The former, at the terminus of the Second Street Cable Railway, was known for its elevation, view, fresh air and agreeable environment of lawn and flower-bed, and the first floor was surrounded with broad verandas. For a while it was conducted by Clark & Patrick, who claimed for it "no noise, dirt or mosquitoes." The latter hotel, on Pearl Street near Sixth, was four stories in height and had piazzas extending around three of them; both of these inns were quite characteristic of Southern California architecture. The Bellevue Terrace, so full of life during the buoyant Boom days, still stands, but alas! the familiar old pile has surrendered to more modern competitors.

The Tivoli Opera House, on Main Street between Second and Third, was opened by McLain & Lehman in 1887, and for a time it was one of the attractions of the city. It presented a curious mixture of Egyptian, East Indian and Romanesque styles, and was designed by C. E. Apponyi, an architect who had come to the Coast in 1870. The stage was the largest, except one—that of the San Francisco Grand Opera House—on the Coast, and there were eight proscenium boxes. The theater proper stood in the rear of the lot, and entrance thereto was had through the building fronting on the street; and between the two structures there was a pretty garden, with grottos and fountains, and a promenade gallery above.

In February, the Postmaster packed the furniture and other outfit—only two or three good loads—and moved the Post Office to the Hellman Building, at the corner of North Main and Republic streets; but it was soon transferred to an office on Fort Street, south of Sixth, a location so far from the center of the city as to give point to cards distributed by some wag and advertising rates for sleeping accommodations to the new office. In that year, the sum-total of the receipts of the Los Angeles Post Office was not much over seventy-four thousand dollars. During the twelve months of the Boom, mail for over two hundred thousand transients was handled; and a familiar sight of the times was the long column of inquirers, reminding one of the famous lines in early San Francisco when prospectors for gold paid neat sums for someone else's place nearer the general delivery window.

I have told of some incidents in the routine of court proceedings here, in which both judge and counselor played their parts. Now and then the juror also contributed to the diversion, as was evidenced in the late eighties when a couple of jurymen in a San Gabriel Cañon water case created both excitement and merriment through a practical joke. Tiring of a midnight session, and bethinking himself of the new invention to facilitate speaking at a distance, one of the jurors telephoned police headquarters that rioters were slashing each other at a near-by corner; whereupon the guardians of the peace came tearing that way, to the merriment of the "twelve good men and true" peeking out from an upper window. The police having traced the telephone message, the jury was duly haled before the judge; and the latter, noting the reticence of the accused, imposed a fine of twenty-five dollars upon each member of the box for his prank.

William H. Workman, who had repeatedly served the City as Councilman, was elected Mayor of Los Angeles in 1887. During Workman's administration, Main, Spring and Fort streets were paved.

About 1887, Benjamin S. Eaton, as President, took the lead in organizing a society designed to bring into closer relationship those who had come to California before her admission to the Union. There were few members; and inasmuch as the conditions imposed for eligibility precluded the possibility of securing many more, this first union of pioneers soon ceased to exist.

Professor T. S. C. Lowe, with a splendid reputation for scientific research, especially in the field of aëronautics—having acquired his first experience with balloons, as did also Graf Ferdinand Zeppelin, by participating in the Union army maneuvers during our Civil War—took up, in the late eighties, the business of manufacturing gas from water, which he said could be accomplished beyond any doubt for eight cents a thousand feet. C. F. Smurr, the capable Los Angeles agent of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, as well as Hugh Livingston Macniel, son-in-law of Jonathan S. Slauson and then Cashier of the Main Street Savings Bank, became interested with Lowe and induced Kaspare Cohn and me to participate in the experiment.

Accordingly, we purchased six acres of land on the southeast corner of Alameda and Seventh streets for fifteen thousand dollars, and there started the enterprise. We laid pipes through many of the streets and, in the course of a few months, began to manufacture gas which it was our intention to sell to consumers at one dollar per thousand feet. The price at which gas was then being sold by the Los Angeles Gas Company was one dollar and fifty cents per thousand, and we therefore considered our schedule reasonable. Everything at the outset looked so plausible that Smurr stated to his associates that he would resign his position with the railroad and assume the management of the new gas works; but to our chagrin, we found that gas was costing us more than one dollar per thousand, and as one discouragement followed another, Smurr concluded not to take so radical a step. Yet we remained in business in the hope that the Los Angeles Gas Company would rather buy us out than reduce their price fifty cents a thousand feet, and sure enough, it was not so very long before they did. The large gas tank now standing at the corner of Seventh and Alameda streets is the result of this transaction.

Late in the spring, Senator Stanford and a party of Southern Pacific officials visited Los Angeles with the view of locating a site for the new and "magnificent railroad station" long promised the city, and at the same time to win some of the popular favor then being accorded the Santa Fé. For many years, objection had been made to the tracks on Alameda Street, originally laid down by Banning; and hoping to secure their removal, Mayor Workman offered a right of way along the river-front. This suggestion was not accepted. At length the owners of the Wolfskill tract donated to the railroad company a strip of land, three hundred by nineteen hundred feet in size, fronting on Alameda between Fourth and Sixth streets, with the provision that the company should use the same only for railroad station purposes; and Stanford agreed to put up a "splendid arcade," somewhat similar in design to, but more extensive and elaborate than, the Arcade Depot at Sacramento. Soon after this, the rest of that celebrated orchard tract, for over fifty years in the possession of the Wolfskill family, was subdivided, offered at private sale and quickly disposed of.

The old-fashioned, one-horse street car had been running on and off the tracks many a year before the City Railroad, organized, in the middle eighties, by I. W. Hellman and his associates, W. J. Brodrick, John O. Wheeler and others, made its more pretentious appearance on the streets of Los Angeles. This, the first line to use double tracks and more modern cars with drivers and conductors, followed a route then considered very long. Starting as it did at Washington Street and leading north on Figueroa, it turned at Twelfth Street into Olive and thence, zigzagging by way of Fifth, Spring, First, Main, Marchessault, New High, Bellevue Avenue, Buena Vista, College, Upper Main and San Fernando streets, it passed River Station (the Southern Pacific depot on San Fernando Street), and ran out Downey Avenue as far as the Pasadena Railroad depot.

The year 1885 saw the addition of another Spanish name to the local map in the founding of Alhambra, now one of the attractive and prosperous suburbs of Los Angeles.

Sometime in the spring of 1885, or perhaps a little earlier, the Second Street Cable Railway was commenced when Isaac W. Lord turned a spadeful of earth at the corner of Second and Spring streets; and within a few months cars were running from Bryson Block west on Second Street over Bunker Hill along Lakeshore Avenue and then by way of First Street to Belmont Avenue, soon bringing about many improvements on the route. And if I am not mistaken, considerable patronage came from the young ladies attending a boarding school known as Belmont Hall. Henry Clay Witmer was a moving spirit in this enterprise. In course of time the cable railway connected with the steam dummy line, landing passengers in a watermelon patch—the future Hollywood.

Unlike Sierra Madre, so long retarded for want of railway facilities, Monrovia—founded in May, 1886, by William N. Monroe, at an altitude of twelve hundred feet, and favored by both the Santa Fé and the Southern Pacific systems—rapidly developed, although it did not attain its present importance as a foothill town until it had passed through the usual depression of the late eighties, due to the collapse of the Boom, of which I am about to speak.

Not as impulsively perhaps as on previous occasions, I left Los Angeles for Europe on April 30th, 1887, accompanied by my wife and our two children, Marco and Rose. Mrs. Eugene Meyer, my wife's youngest sister, and her daughter joined us at San Francisco and traveled with us as far as Paris. We took passage on the French ship Normandie, departing from the Morton Street Pier in New York on May 14th, and nine days later we landed at Havre, from which port we proceeded to the French capital.

On this trip we visited France, England, Scotland, Ireland, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Germany, Austria—including Bohemia—and Italy. We also touched at points in Sweden, although we did not "do" that country thoroughly until a later voyage. While in Germany, where I met my nephew Leo—son of J. P. Newmark—then a student in Strassburg, I was impressed with the splendid hotels and State highways, and the advantage taken of natural resources; and from Ems on July 22d, I wrote a letter on the subject to Kaspare Cohn, which I later found had been published by one of the Los Angeles dailies. During this journey we traveled with M. J. Newmark and his family. It was also on this tour, on June 10th, that I returned to my native town of Loebau, both to visit the graves of my parents and once more to see some relatives and a few old friends.

In Paris we had an exciting experience as observers of a conflagration that might have terminated seriously for us. We had been thinking of going to the Opéra Comique in the evening, but instead had accepted an invitation to dinner at the residence of Alexander Weil, the well-known international banker, formerly of San Francisco; and only on our return to the Hôtel du Helder, a comfortable family hostelry in the Rue du Helder (within a couple of blocks of the theater), did we learn of a disastrous fire in the opera house which caused the loss of many lives. For blocks around, streets and sidewalks were roped in and great was the confusion everywhere. The following day a number of solicitous inquiries arrived from friends in America.

In connection with our departure for this tour of Europe, I am reminded of a unique gift to my wife of a diary in eight volumes, tastefully bound in Russian leather—the whole neatly encased for traveling. With almost painful regularity my wife entered there her impressions and recollections of all she saw, refusing to retire at night, as a rule, until she had posted up her book for the day. Glancing over these pages written in her distinct, characteristically feminine hand, I note once more the intellectual vigor and perspicuity displayed by my companion in this, her first contact with European life and customs.

It was during my absence, on May 2d, that Erskine Mayo Ross was appointed, by President Cleveland, Judge of the new United States District Court just established. He was then in partnership with Stephen M. White. A native of Belpré, Virginia, he had come to Los Angeles in 1868 to study law with his uncle, Cameron E. Thom. Soon admitted to the Bar, he was elected in 1879, at the age of thirty-four, to the Supreme Bench of the State. The Judge, with whom I have been on friendly terms since his arrival, is still living in Los Angeles, a familiar and welcome figure in club circles.

Speaking of this esteemed Judge, I am reminded of a visit here, in 1887, of Justice Stephen J. Field, when he sat with Judge Ross in the United States Circuit Court, the sessions of which were then held over the Farmers & Merchants National Bank at the corner of Main and Commercial streets. On that occasion the members of the Bar, irrespective of party, united to do him honor; and Justice Field, in turn, paid a warm tribute to Los Angeles and her hospitality.

D. W. Hanna, a Michigan pedagogue who had come to Los Angeles in 1884 to open Ellis College on Fort Street near Temple—burned in 1888—established on September 2d, 1885, the Los Angeles College, a boarding school for girls, in a couple of buildings at the corner of Fifth and Olive streets. In 1887 Hanna, having formed a stock company, erected a new school structure at the southwest corner of Eighth and Hope streets, where eighteen teachers soon instructed some two hundred and fifty students. But the institution failed, and the building, still standing, was finally bought by Abbot Kinney and named the Abbotsford Inn.

In a note regarding the life and accomplishments of Mme. Severance, I have referred to the distinguished rôle played by this Angeleña in the early advocacy of the kindergarten for America. It took three years, however, for the educational authorities here to awake to the significance of the departure, for it was not until 1887 that Froebel's plan was admitted for experiment into the Los Angeles schools.

A group of Presbyterian clergymen from Los Angeles and vicinity in 1887 joined in establishing Occidental College—now, as developed under John Willis Baer, one of the promising institutions of the Southwest—locating its site east of the city between First and Second streets, both lots and acreage having been donated with the usual Southern California liberality. There, the following year, the main college building was erected; but in 1896 that structure and most of its contents were destroyed by fire.

Early in June, as ex-Mayor E. F. Spence was about to leave for Europe, some enthusiasm was created in educational circles by the announcement that he would deed certain property, including the lot at the corner of Pearl and Sixth streets (on which the Gates Hotel now stands), to the University of Southern California for the establishing of a telescope on Mount Wilson. The matter had been communicated to President M. M. Bovard, who ordered a glass from the celebrated Cambridge grinders, Alvan Clark & Sons. When President Bovard died, Spence was too ill to arrange the details necessary to the further carrying out of his plans; the property that he had promised to give remained part of his estate; and the great glass, when ground, had to be resold, the University of Chicago becoming the lucky purchaser. As all the scientific world knows, the Carnegie Foundation at Washington some years later established, to the extension of California's fame, the celebrated Wilson telescopes on the mountain Spence once had in view.

Early in June, also, Smith & McPhee issued a directory of Los Angeles. But two weeks afterward, George W. Maxwell published another book of addresses with more than five thousand additional names! The second directory listed over eighteen thousand adults, from which fact it was estimated that Los Angeles then had a population of quite sixty thousand.

In 1887, Mrs. Charlotte LeMoyne Wills, wife of the attorney, John A. Wills, and daughter of Dr. Francis Julius LeMoyne (who in 1876 erected at Washington, Pennsylvania, the first modern crematory in the world, notwithstanding that he was denied permission by the cemetery authorities there and was compelled to construct the furnace on his property outside of the town), inspired the establishing here of what is said to have been the second crematory in the United States and certainly the first built west of the Rocky Mountains. It was opened at Rosedale Cemetery by the Los Angeles Crematory Society, which brought to the Coast an incinerating expert. Dr. W. LeMoyne Wills, a son, was one of the leading spirits in the enterprise and among the first directors of the local organization. The first cremation occurred in June; and the first body so disposed of was that of the wife of Dr. O. B. Bird, a homeopathic physician. The experiment stirred up a storm of adverse, as well as of favorable criticism.

The brothers Beaudry were interested, doubtless through their undeveloped hill-property, in organizing the Temple Street Cable Railway, running from the foot of Temple Street at Spring out Temple as far west as Union Avenue, with cars operated every ten minutes. The Company had an office at No. 10 Court Street, and the Directors were: Prudent Beaudry, Victor Beaudry, Walter S. Maxwell, E. T. Wright, the surveyor, Octavius Morgan, Ralph Rogers, Thomas Stovell, John Milner and E. A. Hall.

About July, the trustees of James Lick sold Santa Catalina Island to George R. Shatto (who founded Avalon[40]—at first giving it his name—and after whom Shatto Street is called), the price fixed upon being one hundred and fifty thousand dollars, Shatto making a partial payment; whereupon the latter agreed to resell the island to an English syndicate. Failure to find there the store of minerals they expected, however, led the English bankers to refuse the property; and in 1892, after a friendly suit had reëstablished the title of the Lick trustees, they disposed of that part of the estate (for about the same price offered Shatto), to William, J. B. and Hancock Banning—sons of my old friend, Phineas Banning—the three forming the Santa Catalina Island Company. Several years later, George S. Patton was admitted as a partner. Little by little Catalina became a favorite resort, although it was years before there was patronage enough to warrant a daily steamer service. In the summer of 1887, for example, at the height of the Boom, William Banning, manager of the Wilmington Transportation Company, ran the steamer Falcon (whose Captain was J. W. Simmie) only once every seven or eight days. Then the vessel used to leave San Pedro wharf at one o'clock in the afternoon and return the next day in time to connect with the three o'clock train for Los Angeles. The fare for the round trip was four dollars.

The year 1887 witnessed the completion of the Arcadia Hotel at Santa Monica, named after Doña Arcadia, wife of Colonel R. S. Baker. It was built on a bluff, was four stories high and had a great veranda with side wings; and with its center tower and cupola was more imposing than any hotel there to-day. Under the proprietorship of J. W. Scott, the Arcadia became one of the first fine suburban hotels in Southern California.

As late as 1887 there was no passenger service between the city and Santa Monica from six to seven o'clock in the evening, though I cannot say just how many trains ran during the day. I am sure, however, that there were not many. Merchants spending their summers at the beach were more inconvenienced through this lack of evening service than at any other time; and after repeated complaints, a coach was hooked onto a freight train. Later, the Board of Trade objected to this slow method, and arrangements were made for another passenger train.

Speaking of Santa Monica in the late eighties, I am reminded of a gravity railroad, somewhat on the principle of the present-day roller-coaster, which was opened near the Arcadia Hotel and as a novelty was a great success. The track was not more than fifteen feet above the ground at its highest point of elevation—just sufficient to give the momentum necessary for an undulating movement.

As the final sequence to the events of three or four preceding years, Los Angeles, at the time when I left for Europe, had already advanced beyond the threshold of her first really violent "boom;" and now symptoms of feverish excitement were everywhere noticeable in Southern California. The basis of real estate operations, heretofore sane enough, was quickly becoming unbalanced, a movement that was growing more and more intensified, as well as general; and as in the case of a mighty stream which accumulates overwhelming power from many feeders, there was a marshalling, as it were, in Los Angeles of these forces. The charms of climate and scenery (widely advertised, as I have said, at the Philadelphia Centennial and, later, through the continuous efforts of the first and second Chambers of Commerce and the Board of Trade), together with the extension of the Southern Pacific to the East and the building of the Santa Fé Railroad, had brought here a class of tourists who not only enjoyed the winter, but ventured to stay through the summer season; and who, having remained, were not long in seeking land and homesteads. The rapidly-increasing demand for lots and houses caused hundreds of men and women to enter the local real-estate field, most of whom were inexperienced and without much responsibility. When, therefore, the news of their phenomenal activity got abroad, as was sure to be the case, hordes of would-be speculators—some with, but more without knowledge of land-manipulation, and many none too scrupulous—rushed to the Southland to invest, wager or swindle. Thousands upon thousands of Easterners swelled the number already here; dealers in realty sprang up like mushrooms. It was then that the demand for offices north of First Street, exceeding the supply, compelled many an agent unwillingly to take accommodations farther south and brought about much building, even to—Second Street! It also happened that a dozen or more competitors occupied a single store-room. Selling and bartering were carried on at all hours of the day or night, and in every conceivable place; agents, eager to keep every appointment possible, enlisted the services of hackmen, hotel employees and waiters to put them in touch with prospective buyers; and the same properties would often change hands several times in a day, sales being made on the curbstone, at bars or restaurant tables, each succeeding transfer representing an enhanced value. Although I was abroad during the height of this period, psychologically so interesting, newspapers, letters and photographs from home—supplemented, on my return, by the personal narratives of friends—supplied me with considerable information of the craze.

As I have already remarked, the coming of the Santa Fé—as well as the ensuing railroad war—was a very potent factor in this temporary growth and advance in values; and soon after the railroad's advent, a dozen towns had been laid out on the line between Los Angeles and San Bernardino, the number doubling within a few months. Indeed, had the plan of the boomers succeeded, the whole stretch between the two cities would have been solidly built up with what in the end proved, alas! to be but castles in the air. Wherever there was acreage, there was room for new towns; and with their inauguration, thousands of buyers were on hand to absorb lots that were generally sold on the installment plan. More frequently than otherwise, payments became delinquent and companies "went broke;" and then the property reverted to acreage again. This sometimes led to serious complications, especially when the contract between the landowner and the so-called syndicate allowed the latter to issue clear title to those who paid for their lots. In such cases, the acreage when recovered by the original owner would be dotted here and there with small possessions; and to reinstate his property was, as a rule, no easy task. This, of course, refers to the failures of which there were more than enough; on the other hand, many of the towns inaugurated during the Boom period not only have survived and prospered, but have become some of our most attractive and successful neighbors.

If every conceivable trick in advertising was not resorted to, it was probably due to oversight. Bands, announcing new locations, were seen here and there in street cars, hay and other wagons and carriages (sometimes followed by fantastic parades a block long); and for every new location there was promised the early construction of magnificent hotels, theaters or other attractive buildings that seldom materialized. When processions filled the streets, bad music filled the air. Elephants and other animals of jungle and forest, as well as human freaks—the remnants of a stranded circus or two—were gathered into shows and used as magnets; while other ingenious methods were often invoked to draw crowds and gather in the shekels. The statements as to climate were always verified, but in most other respects poor Martin Chuzzlewit's experience in the Mississippi town of Eden affords a rather graphic story of what was frequently in progress here during the never-to-be-forgotten days of the Boom. As competition waxed keener, dishonest methods were more and more resorted to; thus schemers worked on the public's credulity and so attracted many a wagon-load of people to mass-meetings, called ostensibly for the purpose of advancing some worthy cause but really arranged to make possible an ordinary sale of real estate. An endless chain of free lunches, sources of delight to the hobo element in particular, drew not only these chronic idlers but made a victim of many a worthier man. Despite all of this excitement, the village aspect in some particulars had not yet disappeared: in vacant lots not far from the center of town it was still not unusual to see cows contentedly chewing their cud and chickens scratching for a living. In 1889, however, the Council governed this feature of domestic life by ordinance, and thenceforth there was less of the "cock's shrill clarion."

Extraordinary situations arose out of the speculative mania, as when over-ambitious folks, fearful perhaps lest they might be unable to obtain corner- and other desirably-situated lots, stationed themselves in line two or three days before the date of anticipated land-sales; and even though quite twenty selections were frequently the limit to one purchase, the more optimistic of our boomers would often have two or three substitutes waiting in a line extending irregularly far down the sidewalk and assuming at night the appearance of a bivouac. I have heard it said that as much as a hundred dollars would be paid to each of these messengers, and that the purchaser of such service, apprehensive lest he might be sold out, would visit his representative many times before the eventful day. Later, this system was improved and official place-numbers were given, thus permitting people to conduct their negotiations without much loss of time.

So little scientific consideration was given to actual values that they were regulated according to calendar and clock; lots in new subdivisions remaining unsold were advertised to advance to certain new prices at such and such an hour, on such and such a day. After these artificial changes, investors would gleefully rub their hands and explain to the downcast outsider that they had "just gotten in in time;" and the downcast outsider, of whom there were many, yielding after repeated assaults of this kind, would himself become inoculated with the fever and finally prove the least restrained boomer of them all. From what I read at the time and heard after my return, I may safely declare that during the height of the infection, two-thirds of our population were, in a sense, more insane than sane.

Syndicates, subdivisions and tracts: these were the most popular terms of the day and nearly everybody had a finger in one or the other pie. There were enough subdivisions to accommodate ten million people; and enough syndicates to handle the affairs of a nation. And talking about syndicates: the disagreement of members themselves as to values frequently prevented the consummation of important sales and resulted in the loss of large profits to the objectors as well as to their associates. In many a well-authenticated case, the property remained on the owners' hands until it became almost worthless.

Wide-awake syndicates evolved new methods, one of which—the lottery plan—became popular. A piece of land would be prepared for the market; and after the opening of streets, as many chances would be sold as there were lots in the tract. On the eventful day, the distribution took place in the presence of the interested and eager participants, each of whom made a selection as his number was drawn. To increase the attractiveness of some of these offers, cottages and even more elaborate houses were occasionally promised for subsequent erection on a few lots. The excitement at many of these events, I was informed, beggared description. Among others sold in this manner at the beginning, or possibly even just before the Boom, were the Williamson Tract, beginning at the corner of Pico and Figueroa streets and once the home-place of the Formans, and the O. W. Childs orchard on the east side of Main Street and running south from what is now about Eleventh. Both of these drawings took place in Turnverein Hall, and the chances sold at about three hundred and fifty dollars each.

Tricksters, of whom at such times there are always enough, could exercise their mischievous proclivities; and the unwary one, who came to be known as the tenderfoot, was as usual easily hoodwinked. Land advertised as having "water privileges" proved to be land under water or in dry creeks; land described as possessing scenic attractions consisted of—mountains and chasms! So situated were many of these lots that no use whatever could be made of them; and I presume that they are without value even now. One of the effects of subdividing a good part of the ten thousand or more acres of agricultural land in the city then irrigated from the zanjas was both to reduce the calls for the service of the city Zanjero, and to lessen considerably the importance and emoluments of his office.

Advertisers tried to outdo themselves and each other in original and captivating announcements; with the result that, while many displayed wit and good humor, others were ridiculously extravagant. The Artesian Water Company came onto the market with three hundred acres of land near Compton and the assurance that "while the water in this section will be stocked, the stock will not be watered." Alvan D. Brock, another purveyor of ranches, declared:

I mean business, and do not allow any alfalfa to grow under my feet.

A. F. Kercheval, the poet, to whom I have already referred, relieved himself of this exuberance regarding the Kercheval Tract (on Santa Fe Avenue, between Lemon and Alamo streets):

HE OR SHE

That Hesitates is Lost!

An axiom that holds good in real estate, as well as in

affairs of the heart.

Selah!

Another advertisement read as follows:

HALT! HALT! HALT!

Speculators and Homeseekers, Attention!

$80,000—Eighty Thousand Dollars—$80,000

Sold in a Day at the Beautiful

McGarry Tract

Bounded by Ninth and Tenth and Alameda Streets.

Come Early, before they are All Gone!

Still another was displayed:

Boom! Boom!

ARCADIA!

Boom! Boom!

And now and then, from a quarter to a full page would be taken to advertise a new town or subdivision, with a single word—the name of the place—such as

RAMIREZ!

Vernon and Vernondale were names given to subdivisions on Central Avenue near Jefferson Street. Advertising the former, the real-estate poet was called into requisition with these lines:

Go, wing thy flight from star to star,

From world to luminous world as far

As the universe spreads its flaming wall,

Take all the pleasure of all the spheres,

And multiply each through endless years,

One Winter at Vernon is worth them all!

while, in setting forth the attractions of the Lily Langtry Tract, the promoter drew as follows from the store of English verse:

Sweet Vernon, loveliest village of the plain,

Where health and plenty cheers the laboring swain,

Where smiling Spring its earliest visit paid,

And parting Summer's lingering blooms delayed;

concluding the announcement with the following lines characteristic of the times:

Catch on before the whole country rushes to Vernondale!

Every man who wishes a home in Paradise should locate in this,

the loveliest district of the whole of Southern California.

This is where the orange groves are loveliest!

This is where the grapes are most luxuriant!

This is where the vegetation is grandest!

This is where the flowers are prettiest!

With the Boom affecting not only Los Angeles but also each acre of her immediate vicinity, Pasadena and the district lying between the two towns took on new life. Five thousand inhabitants boasted a million dollars in deposits and a couple of millions invested in new buildings; while "gilt-edged Raymond," a colony surrounding the Raymond Hotel, became a bustling center. In March, George Whitcomb laid out Glendora, naming it (with the use of a couple of additional letters) after his wife, Ledora; and at the first day's sale, he auctioned off three hundred lots. In December, the old-established town of Pomona was incorporated. Whittier, started by Quakers from Indiana, Iowa and Illinois, and christened in honor of the New England poet, began at this time with a boom, two hundred thousand dollars' worth of property having been sold there in four months. This prosperity led one newspaper to say with extreme modesty:

Whittier is the coming place! It will dwarf Monrovia and eclipse Pasadena. Nothing can stop it! The Quakers are coming in from all over the United States;

and another journal contained an advertisement commencing as follows:

WHITTIER! WHITTIER!! WHITTIER!!!

Queen of the Foothills and Crown of the San Gabriel Valley.

I. W. Lord established Lordsburg—or at least an elaborate hotel there, for in those days a good hotel was half of a town; and when Lordsburg slumped, he sold the building to a colony of Dunkers for a college. Nadeau Park was projected as a town at the junction of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fé's Ballona road and the Southern Pacific. Santa Ana, too, after its sale in June of over eighty thousand dollars' worth of land, came forward in the summer with this confident salutation:

THIS IS PURE GOLD!!!

Santa Ana,

The Metropolis of Southern California's Fairest Valley!

Chief Among Ten Thousand, or the One

Altogether Lovely!

Beautiful! Busy! Bustling! Booming! It

Can't be Beat!

The town now has the biggest kind

of a big, big boom.

A Great Big Boom! And you

Can Accumulate Ducats by Investing!

Fullerton was started in July, when ninety-two thousand dollars changed hands within half a day; and conditions favoring the young community, it survived. Rivera, in the Upper Los Nietos Valley, also then came into being. The glories of Tustin (founded in 1867 by Columbus Tustin, but evidencing little prosperity until twenty years later) were proclaimed through such unassuming advertisements as this:

TUSTIN

THE BEAUTIFUL

Unexcelled in charm and loveliness.

An Earthly Eden Unsurpassed in

Wealth of Flower and Foliage.

However, Imagination Cannot Conceive It:

It must be seen to be realized,

supplemented by the following versification:

When the Angel of Peace to Earth first descended,

To bless with his presence the children of men,

'Mid the fairest of scenes his pathway e'er tended,

And unto his smile the glad earth smiled again.

He joyed in the fragrance of orange and roses,

And loved 'mid their glances to linger or roam,

And he said: "Here in Tustin, where Beauty reposes,

I also will linger or build me a home!"

In April, Jonathan S. Slauson and a company of Los Angeles capitalists laid out and started the town of Azusa, on a slope eight hundred feet high in a rich and promising country. Not so far away was Palomares, announced through the following reassuring poster:

Grand Railroad Excursion and Genuine

AUCTION SALE!

No Chenanekin!!

Thursday, June 7, 1887.

Beautiful Palomares, Pomona Valley!

Lunch, Coffee, Lemonade, and Ice Water Free!

Full Band of Music.

And here it may not be without interest to note the stations then passed in making such an excursion from Los Angeles to the new town: Commercial Street, Garvanza, Raymond, Pasadena, Lamanda Park (named, Henry W. O'Melveny tells me, after Amanda, wife of L. J. Rose), Santa Anita, Arcadia, Monrovia, Duarte, Glendora, San Dimas and Lordsburg. Providencia rancho, consisting of seventeen thousand acres of mountain and valley, was opened up in 1887 and the new town of Burbank was laid out; J. Downey Harvey, J. G. Downey's heir, and David Burbank, the good-natured dentist and old-timer, then living on the site of the Burbank Theater (once the orchard of J. J. Warner), being among the directors. About the same time, twelve thousand acres of the Lankershim rancho, adjoining the Providencia, were disposed of. Sixty-five dollars was asked for a certificate of stock, which was exchangeable later for an acre of land. Glendale was another child of the Boom, for the development of which much dependence was placed on a new motor railroad. Rosecrans and its Addition were two other tracts relying on improved facilities for communicating with Los Angeles. Under the caption, Veni, Vidi, Vici! a motor road was promised for service within ninety days; and lots, from one hundred dollars up, were then to be advanced five hundred per cent! Excursions, accompanied by Colonel Bartlett's Seventh Infantry Band, to "magnificent Monte Vista, the Gem of the Mountains! the Queen of the Valley!" near San Fernando, fifteen miles from Los Angeles, were among the trips arranged.

Speaking of the Boom, I recall an amusing situation such as now and then relieved the dark gloom of the aftermath. When a well-known suburb of Los Angeles was laid out, someone proposed that a road be named Euclid Avenue; whereupon a prominent citizen protested vigorously and asked what Mr. Euclid had ever done for Southern California?

During 1887, and at the suggestion of George E. Gard, many neighboring towns—a number of which have long since become mere memories—donated each a lot, through whose sale a Los Angeles County exhibit at the reunion of the Grand Army of the Republic was made possible; and among these places were Alosta, Gladstone, Glendora, Azusa, Beaumont, Arcadia, Raymond, San Gabriel, Glendale, Burbank, Lamar's Addition to Alosta, Rosecrans, St. James, Bethune, Mondonville, Olivewood, Oleander, Lordsburg, McCoy's[41] Addition to Broad Acres, Ivanhoe, New Vernon, Alta Vista, Nadeau Park, Bonita Tract, San Dimas, Port Ballona, Southside, Ontario, Walleria and Ocean Spray. When the lots were sold at Armory Hall, some ten thousand dollars was realized—twelve hundred and seventy-five dollars, paid by Colonel Banbury for a piece of land at Pasadena, being the highest price brought. Not even the celebrity given the place through the gift of a lot to the Grand Old Man of England saved Gladstone; and St. James soon passed into the realms of the forgotten, notwithstanding that one hundred and fifty vehicles and five hundred people were engaged, in June, in caring for the visitors who made their way to the proposed town-site, five miles from Anaheim, and bought, when there, forty thousand dollars' worth of property in a few hours.

Ben E. Ward—a good citizen whose office was in the renovated municipal adobe—operated with Santa Monica realty during the Boom, somewhat as did Colonel Tom Fitch in the cradle days of the bay city. He ran private trains and sold acre and villa lots, and five-and ten-acre farms, for ten per cent. of the price "at the fall of the hammer;" the balance of the first quarter payable on receipt of the agreement, and the other payments in six, twelve and eighteen months. On one occasion in June, Ward was advertising as follows:

HO, FOR THE BEACH!

To-morrow, To-morrow!

Grand Auction Sale at

Santa Monica.

350—Acres—350

One of the Grandest Panoramic Views the Human Eye ever rested upon, including Ballona, Lake and Harbor, with its outgoing and in-coming vessels, the Grand Old Pacific, the handsome new Hotel Arcadia, while in the distance may be seen Los Angeles, the Pride of All, and the coming city of two hundred thousand people.

Long Beach came in for its share of the Boom. In July, H. G. Wilshire (after whom, I believe, Wilshire Boulevard was named), as general manager of the new hotel at that place, offered lots at one hundred and fifty dollars and upward, advertising under the caption, "Peerless Long Beach!" and declaring that the place was "no new settlement, but a prosperous town of two thousand people," to be "reached without change of cars." The hotel was to be doubled in size, streets were to be sprinkled and bathhouses—with hot and cold water—were to be built. One of the special attractions promised was even a billiard-room for ladies! But the hotel was afterward destroyed by fire, and Long Beach dwindled away until, in 1890, it had scarcely a population of five hundred.

Besides the improving of Santa Monica and the expanding of San Pedro, several harbor projects were proposed in the days of the Boom. About the first of June, 1887, Port Ballona—formerly Will Tell's—began to be advertised as "The Future Harbor of Southern California" and the ocean terminus of the California Central Railroad, which was a part of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fé system. In August, thousands of people assembled at the beach to celebrate the opening of La Ballona Harbor. The enterprise had been backed by Louis Mesmer, Bernard Mills, Frank Sabichi and others; and Mesmer, General Nelson A. Miles, ex-Governor Stoneman, Eugène Germain and J. D. Lynch were among the speakers. A syndicate, headed by J. R. Tuffree, which purchased the Palos Verdes rancho, announced its intention of creating the harbor of Catalina at Portuguese Bend. The syndicate was to build there a large hotel named Borromea, while a Mr. Kerckhoff, encouraged by the prospect of a railroad around Point Firmin, was to erect another huge hotel and lay out a watering place.

As the Boom progressed and railroads continued to advertise Los Angeles, the authorities began to look with consternation on the problem of housing the crowds still booked to come from the East; and it was soon recognized that many prospective settlers would need to roost, for a while, as best they could in the surrounding territory. The Hotel Splendid, an enterprise fostered by Hammel & Denker, proprietors of the United States Hotel, was then commenced on Main Street, between Ninth and Tenth, though it was never completed. Numerous capitalists and business houses encouraged the proposition; yet the site was sold, but a single generation ago, to O. T. Johnson, a local philanthropist, for about twenty-five thousand dollars—a conservative estimate placing its present value at not much less than two and a half millions.

But there are other indications of the strength, or perhaps the weakness, of the Boom. In 1887, the total assessment of the young City and County was three million dollars, or about one-third that recorded for the longer-developed City and County of San Francisco. In one day in July, real estate valued at $664,000 was transferred; on another day in the same month, $730,000 worth; and soon after, in one day, property to the value of $930,000 changed hands. From forty million dollars in March, 1886, the wealth of the county jumped, in just two years, to one hundred and three millions. So many, indeed, were the purchasers of real estate in Los Angeles at that time who soon left the town and were seldom or never heard of again, and so many were the sales effected by proxy, that even in August of 1887 one of the newspapers contained over three pages of taxes listed on property whose possessors were unknown.

During this wild excitement, few men of position or reputation who came to town escaped interrogation as to what they thought of the Boom. "Phil" D. Armour, head of the Armour Packing Company, was one who arrived late in July, and whose opinion was immediately sought; and his answer indicated the unbounded confidence inspired in the minds of even outsiders by the unheard-of development of land values. "Boom—will it break soon?" repeated Armour and proceeded to answer his own query. "There is no boom to break! This is merely the preliminary to a boom which will so outclass the present activities that its sound will be as thunder to the cracking of a hickory nut!" Nor was Armour the only one who was so carried away by the phenomena of the times: San Francisco watched Los Angeles with wonder and interest, marveling at all she heard of the magic changes south of the Teháchepi, and asking herself if Los Angeles might not be able to point the way to better methods of city-building?

I have thus endeavored to give a slight idea of the lack of mental poise displayed by our good people in the year 1887, when the crop of millionaires was so great that to be one was no distinction at all. But alas! the inevitable collapse came and values tumbled fully as rapidly as they had advanced, finding many (who but a short period before had based their worth on investments figured at several times their value) loaded with overwhelming debts and mortgages quite impossible of liquidation. Indeed, readjustments took years and years to accomplish; and so it happened that many an imaginary Crœsus then became the bidder, often unsuccessful, for humble employment. Just as is always the case, too, in periods such as I have described, the depression, when it came was correspondingly severe and sudden. Many of our greatest boomers and speculators lost all hope; and more than one poor suicide so paid the price of his inordinate craving for wealth.

To be sure, some level-headed people, acting more conservatively than the majority, in time derived large profits from the steady increase in values. Those who bought judiciously during that period are now the men of wealth in Los Angeles; and this is more particularly true as to ownership in business sections of the city. Even at the height of the Boom but little property on any of the streets south of Fifth was worth more than two hundred dollars a foot. Following the Boom, there was an increase of building, much of it doubtless due to contracts already entered into.

Incidental to the opening of the Southern Pacific Railroad's route between the North and South by way of the coast, on August 20th, a great railway fête was held at Santa Bárbara, the first through trains from San Francisco and Los Angeles meeting at that point. A procession, illustrating the progress in transportation methods from the burro pack and stage coach to the modern train of cars, filed about the streets of the old Spanish town. On the return of the Los Angeles excursion train, however, a defective culvert near the Camulos Ranch caused the cars, with one hundred and fifty passengers, to plunge down an embankment—luckily with but few casualties.

L. E. Mosher, who had much literary ability and is still remembered as the author of the poem, The Stranded Bugle, joined the Times staff in August and became prominently identified with the conduct of that newspaper. Later, he left journalism and entered on a business career in New York; but experiencing reverses, he returned to Los Angeles. Failing here, he at length committed suicide, to the deep regret of a large circle of friends.

Late in August, the paving of Main Street, the first thoroughfare of Los Angeles to be so improved, was begun, much to the relief of our townspeople who had too long borne the inconvenience of dusty and muddy roadways, and who, after heavy rains the winter before, had in no uncertain fashion given utterance to their disgust at the backward conditions. This expression was the result of a carefully and generally organized movement; for one morning it was discovered that all of the principal streets were covered with mounds of earth resembling little graves, into each of which had been thrust imitation tombstones bearing such inscriptions as the following: