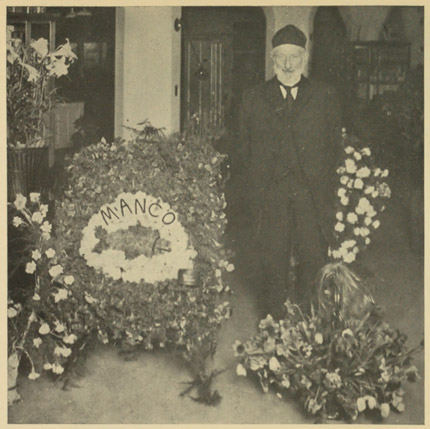

Harris Newmark, at the Dedication of M. A. Newmark & Co.'s Establishment, 1912

Through a high school friendship of my son Marco I came to know quite well one who, though physically handicapped, acquired much international fame. I refer to Homer Lea, a native of Denver, who came to Los Angeles in 1890, at the age of fourteen, studied at the High School, Occidental College and at Stanford, and then conceived the monumental idea of freeing the Chinese from the despotism of the old Manchurian dynasty. Making his first trip to China in 1900, he took an active part in a revolutionary campaign; and returning to America a Lieutenant-General and a force in the Chinese Republican party, he devoted himself to drilling Chinese troops, and to literary work, some of his writings, notably The Valor of Ignorance, when widely translated, bringing him repute as a military strategist. Having married Mrs. Ethel Powers, General Lea, late in 1911, joined Dr. Sun Yat Sen, the Chinese leader, and proceeded with him from London to Shanghai, only to arrive there after the revolution had actually started. Even then success was not to crown his labors; during the convention called to establish the Republic, General Lea was stricken with paralysis and his public career was at an end. He returned to Southern California; and at Ocean Park on November 1st, 1912, while looking out toward the land that he loved so well, Homer Lea yielded up his soul. He was not destined to see the fulfillment of his dream; but when the people for whom he labored shall some day have established a true democracy, his name will loom large in their history.

In December, the Museum of History, Science and Art, so favorably situated in Exposition Park, was informally opened[52] to the public under the scholarly administration of Dr. Frank S. Daggett, who had been appointed Director the year previous; and during the few months following, Professor Daggett, backed by the Board of Supervisors, carried forward with such enterprise the excavations of the pits at La Brea rancho that, before the ornate building was ready to receive the finds, a unique collection of fossils invaluable for the study of California fauna had been assembled. The discovery of these evidences of primeval animal life, already concentrating the attention of the scientific world, may well be regarded with pride by every Southern Californian; while the proper housing here of precious souvenirs recalling those whose lives have contributed so much to making Los Angeles what it was and is, will permanently add to the attractions of the Southland.

Pluckily resisting the inroads of an insidious disease, yet cheerful under all the discouraging circumstances and as deeply interested as ever in the welfare of this community, Charles Dwight Willard has been confined to his home for many months. On my last visit I found him very feeble,[53] though still fired with a resistless enthusiasm; the power of his mind asserting itself over the flesh in forcible, if quiet, expression. We sat in a comfortable little bower at his home on San Rafael Heights, with Mrs. Willard, his faithful companion; and after he had uttered an earnest desire to see these memoirs published, we chatted about his life and his activities here. Born in Illinois and graduating from the University of Michigan, an affection of the lungs, brought on by an attack of typhoid fever, induced him in 1888 to come to Los Angeles in search of a milder climate. His first occupation here was to serve as a reporter for the Times, and then for the morning Herald. In 1891, he was elected Secretary of the Chamber of Commerce; and during the six years of his incumbency he raised the membership from one hundred and fifty to a thousand, at the same time contributing in a powerful manner to the leading part played by this organization in the fight for a free harbor. During that period also, in conjunction with Frank A. Pattee and Harry Brook (both well-known wielders of the pen), he started the Land of Sunshine (six months later taken over by Charles F. Lummis, as editor, and in 1902 renamed the Out West Magazine;) while in 1897 he assumed the management of the Los Angeles Express, from which he resigned two years later. In 1892, he organized with others the Municipal League, serving it ever since as either Secretary or Vice-President, and in the same energetic way in which he toiled as Secretary of the Associated Jobbers. In his literary capacity, Willard has been equally efficient, being the author of a compact History of Los Angeles, a History of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, The Free Harbor Contest and a high school text-book on city government, all of which, as well as contributions to the San Francisco Argonaut, have been favorably received by a discerning public.

Frank Wiggins' name is considered by many of his friends a synonym for that of the Chamber of Commerce. Like his predecessor, Charles D. Willard, Wiggins came to California for his health; and upon its restoration, identified himself with the Chamber of Commerce on September 17th, 1889, becoming Secretary in 1897. Although ferociously bewhiskered, he is the mildest and best-natured man in town. He has had charge, in all parts of the country, of many exhibits so unique and so successful that he is known from coast to coast.

On May 24th, 1913, while many thousand people were assembled at Long Beach for a Southern California celebration of Empire Day, one of the worst of local catastrophes occurred through the caving-in of the defective floor of a crowded dancing pavilion. Medical and police aid were at once despatched from Los Angeles; but the result of the accident, the death of forty persons and injury to many more, cast a deep spell over the two cities.

Dr. Charles F. Lummis, assisted by other public-spirited men and women of Los Angeles including Lieutenant-General Adna R. Chaffee[54] (the first President), Joseph Scott, Mrs. Clara B. Burdette, Miss Mary E. Foy, M. H. Newmark and William Lacy, on the last day of 1907 incorporated the Southwest Museum.[55] On the 1st of March, 1910, Dr. Lummis, celebrating his fifty-first birthday, conveyed to the Museum his priceless collection of Americana. A sightly eminence of seventeen acres near Sycamore Grove was secured; and on November 16th, 1912, ground was broken with the formalities usual to such events, the first spadeful being turned by Miss Elizabeth Benton Frémont, daughter of the Pathfinder, followed by General Chaffee and Dr. Lummis. An inspiring feature of the day was the raising by Miss Frémont and General Chaffee of the same flag that on August 16th, 1842 General Frémont had unfurled on the crest of the Rocky Mountains. On this occasion Henry W. O'Melveny presented a certified check for fifty thousand dollars, the bequest of Mrs. Carrie M. Jones. This auspicious beginning was followed, on July 9th, 1913, by the pouring of the first concrete.[56] How broadly and well those have built who planned this much-needed institution may be seen from both the distinguishing architectural features of the structure, including the caracole tower of cement, and the location—one of the most notable occupied by any museum in the United States.

Dr. J. A. Munk, an Ohioan, to whom I have just referred, has not been in Los Angeles as long as many others, having arrived only in 1892, but he is known among his friends for his charming personality, and among historians and scientists for his splendid collection of Arizoniana—commenced on his first trip to Arizona in 1884—all of which has been given to the Southwest Museum.

Among the features of the Southwest Museum is the large square, or so-called Torrance Tower, the funds for which were generously provided by Jared S. Torrance, whose residence in Pasadena dates from 1887. In that year he came from the Empire State; and ever since he has been an active participator in the development of Southern California. The town of Torrance is an example of his enterprise.

My sixty years' residence in Los Angeles has been by no means free from the ordinary family cares, vicissitudes and sorrows, and it seems proper that I should refer to the physicians who, in times of illness, have ministered to the comfort of my home and its inmates. Our first doctor was John S. Griffin, and he continued in that capacity until I left for New York. Shortly before 1873, Dr. Griffin, whose advancing age compelled him to withdraw from general practice, had been calling Dr. Joseph Kurtz into consultation; and it was then that the latter became my family physician. For a short time, I consulted Dr. Charles A. H. De Szigethy, a relic of the old school, whose nauseating doses were proverbial; and then Dr. John R. Haynes, now well known as an advocate of Socialism, who had arrived from Philadelphia in May, 1887, assumed the responsibility. Again a long period elapsed before events caused a change. In the year 1897, my nephew, Dr. Philip Newmark, came to Los Angeles from Berlin and succeeded Dr. Haynes.

Notwithstanding these mutations and cares, my friends have often insisted that I am quick and perhaps even sprightly for my age, and have more than once asked to what I attribute this activity and alertness. It is due, I think, first, to the inheritance from my parents of a strong constitution; and, secondly, to the preservation of my health by a moderate, though never over-abstemious, manner of living.

To begin with, ever since I traveled with my father in Sweden, I have kept my mind healthfully employed, while I have never long deprived myself of rest. I have also always used tobacco and liquor in moderation; and in this connection I can testify that, although wine and beer were at the free disposal of my children, they have grown up to use it either most temperately or not at all. This fact I ascribe to liberal views on such subjects; for it has always been my belief that to prohibit is to invite, whereas to furnish a good example and at the same time to warn, is to insure rational restriction and limitation. In short, in preparation for a vigorous old age, I have followed as closely as I could the ancient ideal, "A sound mind in a sound body."

At the age of nineteen, I came to Los Angeles; and after a lapse of exactly sixty years—that is, on October 21st, 1913—I find myself completing these reminiscences, ruminating on the past, and attempting a prophecy for the future.

A battle of eighty years with the world cannot, in the nature of human affairs, leave any man or woman unscarred; but I have learned many things, and among them the consolations of philosophy. It would be presumption on my part to make complaint against the inscrutable decrees of that Providence which guides the destinies of us all; I dwell, rather, on the manifold blessings which have been my lot in this life—the decision of Fate which cast my lines in the pleasant places of Southern California; the numerous excellent and estimable friends whom I have met on life's highway; the many years of happiness vouchsafed me to enjoy; and, finally, whatever degree of success has attended my more serious efforts.

When I came, Los Angeles was a sleepy, ambitionless adobe village with very little promise for the future. The messenger of Optimism was deemed a dreamer; but time has more than realized the fantasies of those old village oracles, and what they said would some day come to pass in Los Angeles, has come and gone, to be succeeded by things much greater still. We possessed however, even in that distant day, one asset, intangible it is true, but as invaluable as it was intangible—the spirit popularly called "Western," but which, after all, was largely the pith of transferred Eastern enterprise. This characteristic seized upon a vast wilderness—the same which Daniel Webster declared, in the Senate of the United States, unworthy of membership in the sisterhood of States; and within this extensive area it builded great cities, joined its various parts with steel and iron, made great highways out of the once well-nigh impassable cattle-paths, and from an elemental existence developed a complex civilization. Nor is there to-day in all this region a greater or finer city than fair Los Angeles.

Many of us saw it grow; none of us foresaw that growth, even from decade to decade.

"Westward the course of empire takes its way." When Bishop Berkeley so poetically proclaimed this historic truth, even he could hardly have had in mind the shores of the Pacific; but here we have an empire, and one whose future is glorious. This flourishing city stands, in fact, with its half million or more human beings and its metropolitan activities, at the threshold of a new era. The operations of Nature change so slowly as to show almost no change at all: the Southern California of the coming years will still possess her green hills and vales, her life-giving soil, her fruits, flowers and grain, and the same sun will shine upon her with the same generous warmth, out of the same blue sky, as ever. The affairs of men, on the other hand, change rapidly. After gigantic labor initiated but ten short years ago, the Panamá Canal is dedicated to the use of mankind, and through its crowded waters will come the ships of every nation, bringing to the marts of Los Angeles choice products to be exchanged for our own. For this and other reasons, I believe that Los Angeles is destined to become, in not many years, a world-center, prominent in almost every field of human endeavor; and that, as nineteen hundred years ago the humblest Roman, wherever he might find himself, would glow with pride when he said, "I am a Roman!" so, in the years to come, will the son of the metropolis on these shores, wheresoever his travels may take him, be proud to declare,

"I AM A CITIZEN OF LOS ANGELES!"