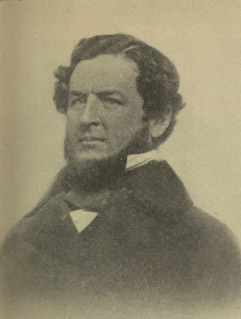

Henry Mellus

From a Daguerrotype

Gentlemen of the Jury: The District Attorney prosecuting my client is paid by the County to convict this prisoner, whether he be guilty or innocent; and I plead with you, gentlemen, in the name of Impartial Justice, to bring in a verdict of "Not guilty!"

Through the help of his old-time friend, Secretary William H. Seward, Dimmick toward the end of his life was appointed Attorney for the Southern District of the United States in California; but on September 11th, 1861, he suddenly died of heart disease.

Eaton, another prominent representative of the Bar, came from New England as early as 1850, while California government was in its infancy and life anything but secure; and he had not been here more than a few months when the maneuvers of António Garra, Agua Caliente's chief, threatened an insurrection extending from Tulare to San Diego and made necessary the organization, under General J. H. Bean, of volunteers to allay the terror-stricken community's fears. Happily, the company's chief activity was the quieting of feminine nerves. On October 3d, 1853, Eaton was elected District Attorney and in 1857, County Assessor. Later, after living for a while at San Gabriel, Eaton became a founder of the Pasadena colony, acting as its President for several years; and in 1876 he was one of the committee to arrange for the local Centennial celebration. Frederick Eaton, several times City Engineer and once—in 1899-1900—Mayor of Los Angeles, is a son of Benjamin Eaton and his first wife, Helena Hayes, who died a few years after she came here, and the brother of Mrs. Hancock Johnston. He reflects no little credit on his father by reason of a very early, effective advocacy of the Owens River Aqueduct. Under his administration, the City began this colossal undertaking, which was brought to a happy consummation in the year 1913 through the engineering skill of William Mulholland, Eaton's friend. In 1861, Judge Eaton married Miss Alice Taylor Clark, of Providence, R. I., who is still living.

While I am upon this subject of lawyers and officialdom, a few words regarding early jurists and court decorum may be in order. In 1853, Judge Dryden, who had arrived in 1850, was but a Police Justice, not yet having succeeded Dimmick as County Judge; and at no time was his knowledge of the law and things pertaining thereto other than extremely limited. His audacity, however, frequently sustained him in positions that otherwise might have been embarrassing; and this audacity was especially apparent in Dryden's strong opposition to the criminal element. He talked with the volubility of a Gatling gun, expressing himself in a quick, nervous manner and was, besides, very profane. One day he was trying a case, when Captain Cameron E. Thom (who had first come to Los Angeles in 1854, as the representative of the National Government, to take testimony before Commissioner Burrill) was one of the attorneys. During the progress of the case, Thom had occasion to read a lengthy passage from some statute book. Interrupting him, the Judge asked to see the weighty volume; when, having searched in vain for the citation, he said in his characteristic, jerky way:

"I'll be —— damned, Mr. Thom, if I can find that law!"

All of which recalls to me a report, once printed in the Los Angeles Star, concerning this same jurist and an inquest held by him over a dead Indian:

Justice Dryden and the Jury sat on the body. The verdict was: "Death from intoxication, or by the visitation of God!"

Dryden, who was possessed of a genial personality, was long remembered with pleasure for participation in Fourth of July celebrations and processions. He was married, I believe, in 1851, only one year after he arrived here, to Señorita Dolores Nieto; and she having died, he took as his second wife, in September, 1868, another Spanish lady, Señorita Anita Dominguez, daughter of Don Manuel Dominguez. Less than a year afterward, on September 10th, 1869, Judge Dryden himself died at the age of seventy years.

Thom, by the way, came from Virginia in 1849 and advanced rapidly in his profession. It was far from his expectation to remain in Los Angeles longer than was necessary; and he has frequently repeated to me the story of his immediate infatuation with this beautiful section and its cheering climate, and how he fell in love with the quaint little pueblo at first sight. Soon after he decided to remain here, he was assigned as associate counsel to defend Pancho Daniel, after the retirement of Columbus Sims. In 1856, Thom was appointed both City and District Attorney, and occupied the two positions at the same time—an odd situation which actually brought it about, during his tenure of offices, that a land dispute between the City and the County obliged Thom to defend both interests! In 1863, he was a partner with A. B. Chapman; and twenty years later, having previously served as State Senator, he was elected Mayor of the city. Captain Thom married two sisters—first choosing Miss Susan Henrietta Hathwell, and then, sometime after her death, leading to the altar Miss Belle Cameron Hathwell whom he had named and for whom, when she was baptized, he had stood godfather. A man ultimately affluent, he owned, among other properties, a large ranch at Glendale.[2]

Another good story concerning Judge Dryden comes to mind, recalling a certain Sheriff. As the yarn goes, the latter presented himself as a candidate for the office of Sheriff; and in order to capture the vote of the native element, he also offered to marry the daughter of an influential Mexican. A bargain was concluded and, as the result, he forthwith assumed the responsibilities and dangers of both shrieval and matrimonial life.

Before the Sheriff had possessed this double dignity very long, however, a gang of horse-thieves began depredations around Los Angeles. A posse was immediately organized to pursue the desperadoes, and after a short chase they located the band and brought them into Los Angeles. Imagine the Sheriff's dismay, when he found that the leader was none other than his own brother-in-law whom he had never before seen!

To make the story short, the case was tried and the prisoner was found guilty; but owing to influence (to which most juries in those days were very susceptible) there was an appeal for judicial leniency. Judge Dryden, therefore, in announcing the verdict, said to the Sheriff's brother-in-law, "The jury finds you guilty as charged," and then proceeded to read the prisoner a long and severe lecture, to which he added: "But the jury recommends clemency. Accordingly, I declare you a free man, and you may go about your business." Thereupon someone in the room asked: "What is his business?" To which the Judge, never flinching, shouted: "Horse-stealing, sir! horse-stealing!"

Lander was here in 1853, having come from the East the year previous. He was a Harvard College graduate—there were not many on the Coast in those days—and was known as a good office-practitioner; he was for some time, in fact, the Bar's choice for Court Commissioner. I think that, for quite a while, he was the only examiner of real estate titles; he was certainly the only one I knew. On October 15th, 1852, Lander had married Señorita Margarita, a daughter of Don Santiago Johnson, who was said to have been one of the best known business men prior to 1846. Afterward Lander lived in a cottage on the northeast corner of Fourth and Spring streets. This cottage he sold to I. W. Hellman in the early seventies, for four thousand dollars; and Hellman, in turn, sold it at cost to his brother. On that lot, worth to-day probably a million dollars, the H. W. Hellman Building now stands. Lander died on June 10th, 1873.

Granger was still another lawyer who was here when I arrived, he having come with his family—one of the first American households to be permanently established here—in 1850. By 1852, he had formed a partnership with Jonathan R. Scott, and in that year attained popularity through his Fourth of July oration. Granger was, in fact, a fluent and attractive speaker, which accounted, perhaps, for his election as City Attorney in 1855, after he had served the city as a member of the Common Council in 1854. If I recollect aright, he was a candidate for the district judgeship in the seventies, but was defeated.

Ogier, a lawyer from Charleston, S. C., came to California in 1849, and to Los Angeles in 1851, forming a partnership on May 31st of that year with Don Manuel Clemente Rojo, a clever, genial native of Peru. On September 29th, Ogier succeeded William C. Ferrell, the first District Attorney; in 1853, he joined the voluntary police; and later served, for some years, as United States District Judge. He died at Holcombe Valley in May, 1861. Ogier Street, formerly Ogier Lane, was named for him. Rojo, after dividing his time between the law and the Spanish editorial work on the Star, wandered off to Lower California and there became a "sub-political chief."

Kewen, a native of Mississippi and a veteran of the Mexican War, came to Los Angeles in 1858 with the title of Colonel, after fiasco followed his efforts, in the Southern States, to raise relief for the filibuster Walker, on whose expedition A. L. Kewen, a brother, had been killed in the battle at Rivas, Nicaragua, in June, 1855. Once a practitioner at law in St. Louis, Kewen was elected California's first Attorney-General, and even prior to the delivery of his oration before the Society of Pioneers at San Francisco, in 1854, he was distinguished for his eloquence. In 1858, he was Superintendent of Los Angeles City Schools. In the sixties, Kewen and Norton formed a partnership. Settling on an undulating tract of some four hundred and fifty acres near San Gabriel, including the ruins of the old Mission mill and now embracing the grounds of the Huntington Hotel, Kewen repaired the house and converted it into a cosy and even luxurious residence, calling the estate ornamented with gardens and fountains, El Molino—a title perpetuated in the name of the present suburb. Kewen was also a member of the State Assembly and, later, District Attorney. He died in November, 1879.

Gitchell, United States District Attorney in the late fifties, practiced here for many years. He was a jolly old bachelor and was popular, although he did not attain eminence.

Isaac Hartman, an attorney, and his wife, who were among the particularly agreeable people here in 1853, soon left for the East.

Volney E. Howard came with his family in the late fifties. He left San Francisco, where he had been practicing law, rather suddenly, and at a time when social conditions in the city were demoralized, and the citizens, as in the case of the people of Los Angeles, were obliged to organize a vigilance committee. William T. Coleman, one of the foremost citizens of his city, led the Northern movement, and M. J. Newmark, then a resident of San Francisco, was among those who participated. Howard, who succeeded William T., afterward General Sherman in leading the Law and Order contingent, opposed the idea of mob rule; but the people of San Francisco, fully alive to the necessity of wiping out the vicious elements, and knowing how hard it was to get a speedy trial and an honest jury, had little sympathy with his views. He was accordingly ordered out of town, and made his way, first to Sacramento, then to the South. Here, with Kewen as their neighbor, Howard and his talented wife, a lady of decidedly blue-stocking tendencies, took up their residence near the San Gabriel Mission; and he became one of the most reliable attorneys in Los Angeles, serving once or twice as County Judge and on the Supreme Court bench, as well as in the State Constitutional Convention of 1878-1879.

Speaking of the informality of courts in the earlier days, I should record that jurymen and others would come in coatless and, especially in warm weather, without vests and collars; and that it was the fashion for each juryman to provide himself with a jack-knife and a piece of wood, in order that he might whittle the time away. This was a recognized privilege, and I am not exaggerating when I say that if he forgot his piece of wood, it was considered his further prerogative to whittle the chair on which he sat! In other respects, also, court solemnity was lacking. Judge and attorneys would frequently lock horns; and sometimes their disputes ended violently. On one occasion, for example, while I was in court, Columbus Sims, an attorney who came here in 1852, threw an inkstand at his opponent, during an altercation; but this contempt of court did not call forth his disbarment, for he was later found acting as attorney for Pancho Daniel, one of Sheriff Barton's murderers, until sickness compelled his retirement from the case. As to panel-service, I recollect that while serving as juror in those early days, we were once locked up for the night; and in order that time might not hang too heavily on our hands, we engaged in a sociable little game of poker. Sims is dead.

More than inkstands were sometimes hurled in the early courts. On one occasion, for instance, after the angry disputants had arrived at a state of agitation which made the further use of canes, chairs, and similar objects tame and uninteresting, revolvers were drawn, notwithstanding the marshal's repeated attempts to restore order. Judge Dryden, in the midst of the mêlée, hid behind the platform upon which his Judgeship's bench rested; and being well out of the range of the threatening irons, yelled at the rioters:

"Shoot away, damn you! and to hell with all of you!"

After making due allowance for primitive conditions, it must be admitted that many and needless were the evils incidental to court administration. There was, for instance, the law's delay, which necessitated additional fees to witnesses and jurors and thus materially added to the expenses of the County. Juries were always a mixture of incoming pioneers and natives; the settlers understood very little Spanish, and the native Californians knew still less English; while few or none of the attorneys could speak Spanish at all. In translating testimony, if the interpreter happened to be a friend of the criminal (which he generally was), he would present the evidence in a favorable light, and much time was wasted in sifting biased translations. Of course, there were interpreters who doubtless endeavored to perform their duties conscientiously. George Thompson Burrill, the first Sheriff, received fifty dollars a month as court interpreter, and Manuel Clemente Rojo translated testimony as well; officials I believe to have been honest and conscientious.

While alluding to court interpreters and the general use of Spanish during at least the first decade after I came to California, I am reminded of the case of Joaquín Carrillo, who was elected District Judge, in the early fifties, to succeed Judge Henry A. Tefft of Santa Bárbara, who had been drowned near San Luis Obispo while attempting to land from a steamer in order to hold court. During the fourteen years when Carrillo held office, he was constantly handicapped by his little knowledge of the English language and the consequent necessity of carrying on all court proceedings in Spanish, to say nothing of the fact that he was really not a lawyer. Yet I am told that Carrillo possessed common sense to such a degree that his decisions were seldom set aside by the higher courts.

Sheriff Burrill had a brother, S. Thompson Burrill, who was a lawyer and a Justice of the Peace. He held court in the Padilla Building on Main Street, opposite the present site of the Bullard Block and adjoining my brother's store; and as a result of this proximity we became friendly. He was one of the best-dressed men in town, although, when I first met him, he could not have been less than sixty years of age. He presented me with my first dog, which I lost on account of stray poison: evil-disposed or thoughtless persons, with no respect for the owner, whether a neighbor or not, and without the slightest consideration for pedigree, were in the habit of throwing poison on the streets to kill off canines, of which there was certainly a superabundance.

Ygnácio Sepúlveda, the jurist and a son of José Andrés Sepúlveda, was living here when I arrived, though but a boy. Born in Los Angeles in 1842, he was educated in the East and in 1863 admitted to the Bar; he served in the State Legislature of the following winter, was County Judge from 1870 to 1873, and District Judge in 1874. Five years later he was elected Superior Judge, but resigned his position in 1884 to become Wells Fargo & Company's representative in the City of Mexico, at which capital for two years he was also American Chargé d'Affaires. There to my great pleasure I met him, bearing his honors modestly, in January, 1885, during my tour of the southern republic.[3] Sepúlveda Avenue is named for the family.

Horace Bell was a nephew of Captain Alexander Bell, of Bell's Row; and as an early comer to Los Angeles, he joined the volunteer mounted police. Although for years an attorney and journalist, in which capacity he edited the Porcupine, he is best known for his Reminiscences of a Ranger, a volume written in rather a breezy and entertaining style, but certainly containing exaggerations.

This reference to the Rangers reminds me that I was not long in Los Angeles when I heard of the adventures of Joaquín Murieta, who had been killed but a few months before I came. According to the stories current, Murieta, a nephew of José María Valdez, was a decent-enough sort of fellow, who had been subjected to more or less injustice from certain American settlers, and who was finally bound to a tree and horsewhipped, after seeing his brother hung, on a trumped-up charge. In revenge, Murieta had organized a company of bandits, and for two or three years had terrorized a good part of the entire State. Finally, in August, 1853, while the outlaw and several of his companions were off their guard near the Tejón Paso, they were encountered by Captain Harry Love and his volunteer mounted police organized to get him, "dead or alive;" the latter killed Murieta and another desperado known as Three-fingered Jack. Immediately the outlaws were despatched, their heads and the deformed hand of Three-fingered Jack were removed from the bodies and sent by John Sylvester and Harry Bloodsworth to Dr. William Francis Edgar, then a surgeon at Fort Miller; but a flood interfering, Sylvester swam the river with his barley sack and its gruesome contents. Edgar put the trophies into whiskey and arsenic, when they were transmitted to the civil authorities, as vouchers for a reward. Bloodsworth died lately.

Daredevils of a less malicious type were also resident among us. On the evening of December 31st, 1853, for example, I was in our store at eight o'clock when Felipe Rheim—often called Reihm and even Riehm—gloriously intoxicated and out for a good time, appeared on the scene, flourishing the ubiquitous weapon. His celebration of the New Year had apparently commenced, and he was already six sheets in the wind. Like many another man, Felipe, a very worthy German, was good-natured when sober, but a terror when drunk; and as soon as he spied my solitary figure, he pointed his gun at me, saying, at the same time, in his vigorous native tongue, "Treat, or I shoot!" I treated. After this pleasing transaction amid the smoky obscurity of Ramón Alexander's saloon, Felipe fired his gun into the air and disappeared. Startling as a demand like that might appear to-day, no thought of arrest then resulted from such an incident.

The first New Year's Eve that I spent in Los Angeles was ushered in with the indiscriminate discharging of pistols and guns. This method of celebrating was, I may say, a novelty to me, and no less a surprise; for of course I was unaware of the fact that, when the city was organized, three years before, a proposition to prohibit the carrying of firearms of any sort, or the shooting off of the same, except in defense of self, home or property, had been stricken from the first constitution by the committee on police, who reported that such an ordinance could not at that time be enforced. Promiscuous firing continued for years to be indulged in by early Angeleños, though frequently condemned in the daily press, and such was its effect upon even me that I soon found myself peppering away at a convenient adobe wall on Commercial Street, seeking to perfect my aim!

Trivial events in a man's life sometimes become indelibly impressed on his memory; and one such experience of my own is perhaps worth mentioning as another illustration of the rough character of the times. One Sunday, a few days after my arrival, my brother called upon a tonsorial celebrity, Peter Biggs, of whom I shall speak later, leaving me in charge of the store. There were two entrances, one on Main Street, the other on Requena. I was standing at the Main Street door, unconscious of impending excitement, when a stranger rode up on horseback and, without the least hesitation or warning, pointed a pistol at me. I was not sufficiently amused to delay my going, but promptly retreated to the other door where the practical joker, astride his horse, had easily anticipated my arrival and again greeted me with the muzzle of his weapon. These maneuvers were executed a number of times, and my ill-concealed trepidation only seemed to augment the diversion of a rapidly-increasing audience. My brother returned in the midst of the fun and asked the jolly joker what in hell he meant by such behavior; to which he replied: "Oh, I just wanted to frighten the boy!"

Soon after this incident, my brother left for San Francisco; and his partner, Jacob Rich, accompanied by his wife, came south and rented rooms in what was then known as Mellus's Row, an adobe building for the most part one-story, standing alone with a garden in the rear, and occupying about three hundred feet on the east side of Los Angeles Street, between Aliso and First. In this row, said by some to have been built by Barton & Nordholt, in 1850, for Captain Alexander Bell, a merchant here since 1842, after whom Bell Street is named, and by others claimed to have been the headquarters of Frémont, in 1846, there was a second-story at the corner of Aliso, provided with a large veranda; and there the Bell and Mellus families lived. Francis Mellus, who arrived in California in 1839, had married the niece of Mrs. Bell, and Bell having sold the building to Mellus, Bell's Row became known as Mellus's Row. Finally, Bell repurchased the property, retaining it during the remainder of his life; and the name was again changed. This famous stretch of adobe, familiarly known as The Row, housed many early shopkeepers, such as Ferner & Kraushaar, general merchants, Kalisher & Wartenberg, and Bachman & Bauman. The coming to Los Angeles of Mr. and Mrs. Rich enabled me to abandon La Rue's restaurant, as I was permitted to board with them. None the less, I missed my brother very much.

Everything at that time indicating that I was in for a commercial career, it was natural that I should become acquainted with the merchants then in Los Angeles. Some of the tradesmen, I dare say, I have forgotten; but a more or less distinct recollection remains of many, and to a few of them I shall allude.

Temple Street had not then been opened by Beaudry and Potts, although there was a little cul-de-sac extending west from Spring Street; and at the junction of what is now Spring and Temple streets, there was a two-story adobe building in which D. W. Alexander and Francis Mellus conducted a general merchandise business, and at one time acted as agents for Mellus & Howard of San Francisco. Mellus, who was born in Salem, Massachusetts, February 3d, 1824, came to the Coast in 1839, first landing at Santa Bárbara; and when I first met him he had married Adelaida, daughter of Don Santiago Johnson, and our fellow-townsman, James J. Mellus—familiarly known as plain Jim—was a baby. Alexander & Mellus had rather an extensive business in the early days, bringing goods by sailing vessel around Cape Horn, and exchanging them for hides and tallow which were carried back East by the returning merchantmen. They had operated more or less extensively even some years before California was ceded to the United States; but competition from a new source forced these well-established merchants to retire. With the advent of more frequent, although still irregular service between San Francisco and the South, and the influx of more white people, a number of new stores started here bringing merchandise from the Northern market, while San Francisco buyers began to outbid Alexander & Mellus for the local supply of hides and tallow. This so revolutionized the methods under which this tradition-bound old concern operated that, by 1858, it had succumbed to the inevitable, and the business passed into the hands of Johnson & Allanson, a firm made up of Charles R. Johnson, soon to be elected County Clerk, and Horace S. Allanson.

Most of the commercial activity in this period was carried on north of First Street. The native population inhabited Sonora Town, for the most part a collection of adobes, named after the Mexican state whence came many of our people; there was a contingent from other parts of Mexico; and a small sprinkling of South Americans from Chile and Peru. Among this Spanish-speaking people quite a business was done by Latin-American storekeepers. It followed, naturally enough, that they dealt in all kinds of Mexican goods.

One of the very few white men in this district was José Mascarel (a powerfully-built French sea-captain and master of the ship that brought Don Luis Vignes to the Southland), who settled in Los Angeles in 1844, marrying an Indian woman. He had come with Prudhomme and others; and under Captain Henseley had taken part in the military events at San Bartolo and the Mesa. By 1865, when he was Mayor of the city, he had already accumulated a number of important real estate holdings and owned, with another Frenchman, Juan Barri, a baker, the block extending east on the south side of Commercial Street, from Main to Los Angeles, which had been built in 1861 to take the place of several old adobes. This the owners later divided, Mascarel taking the southeast corner of Commercial and Main streets, and Barri the southwest corner of Commercial and Los Angeles streets. In the seventies, I. W. Hellman bought the Mascarel corner, and in 1883, the Farmers & Merchants Bank moved to that location, where it remained until the institution purchased the southwest corner of Fourth and Main streets, for the erection of its own building.

Andrés Ramirez was another Sonora Town merchant. He had come from Mexico in 1844, and sold general merchandise in what, for a while, was dubbed the Street of the Maids. Later, this was better known as Upper Main Street; and still later it was called San Fernando Street.

Louis Abarca was a tradesman and a neighbor of Ramirez. Prosperous until the advent of the pioneer, he little by little became poorer, and finally withdrew from business.

Juan Bernard, a native of French Switzerland, whose daughter married D. Botiller, now an important landowner, came to California by way of the Horn, in search of the precious metal, preceding me to this land of sunshine. For awhile, he had a brickyard on Buena Vista Street; but in the late seventies, soon after marrying Señorita Susana Machado, daughter of Don Agustin Machado, he bought a vineyard on Alameda Street, picturesquely enclosed by a high adobe or brick wall much after the fashion of a European château. He also came to own the site of the Natick House. A clever linguist and a man of attractive personality, he passed away in 1889.

An American by the name of George Walters lived on Upper Main Street, among the denizens of which locality he was an influential person. Born at New Orleans as early as 1809, Walters had trapped and traded in the Rocky Mountains, then teamed for awhile between Santa Fé and neighboring points. Near the end of 1844, he left New Mexico in company with James Waters, Jim Beckwith and other travelers, finally reaching Los Angeles. Walters, who settled in San Bernardino, was at the Chino Ranch, with B. D. Wilson and Louis Robidoux, when so many Americans were made prisoners.

Julian Chavez, after whom Chavez Street is named, was here in 1853. If he was not native-born, he came here at a very early day. He owned a stretch of many acres, about a mile northeast of Los Angeles. He was a good, honest citizen, and is worthy of recollection.

Ramón Alexander, a Frenchman often confused with David Alexander, came to Los Angeles before 1850, while it was still a mere Mexican village. Pioneers remember him especially as the builder of the long-famous Round House, on Main Street, and as one who also for some time kept a saloon near Requena Street. Alexander's wife was a Señorita Valdez. He died in 1870.

Antoine Laborie was another Frenchman here before the beginning of the fifties. He continued to live in Los Angeles till at least the late seventies. A fellow-countryman, B. Dubordieu, had a bakery in Sonora Town.

Philip Rheim, the good-natured German to whom I have referred, had a little store and saloon, before I came, called Los dos Amigos, as the proprietor of which he was known as Don Felipe. Nor was this title amiss; for Felipe married a native woman and, German though he had been, he gradually became, like so many others who had mated in the same way, more and more Californian in manners and customs.

A month after I arrived here, John Behn, who had a grocery business at the northeast corner of First and Los Angeles streets, retired. He had come to Los Angeles from Baden in 1848, and, after forming one or two partnerships, had sold out to Lorenzo Leck, a German Dane, who reached here in November, 1849, and whose son, Henry von der Leck, married a daughter of Tom Mott and is living at San Juan Capistrano. Leck opened his own store in 1854, and despite the trials to which he was to be subjected, he was able, in 1868, to pay John Schumacher three thousand dollars for a lot on Main Street. Leck had a liking for the spectacular; and in the November previous to my arrival was active, as I have been told, with Goller and Nordholt, in organizing the first political procession seen in Los Angeles. The election of Pierce was the incentive, and there were gorgeous transparencies provided for the event. It was on this occasion that a popular local character, George the Baker, burned himself badly while trying to fire off the diminutive cannon borrowed from the Spanish padre for the event.

In the one-story adobe of Mascarel and Barri, on the corner of Commercial and Main streets, now the site of the United States National Bank, an Irishman named Samuel G. Arbuckle, who had come here in 1850 and was associated for a short time with S. Lazard, conducted a dry goods store. From 1852 to 1856, Arbuckle was City Treasurer.

In the same building, and adjoining Arbuckle's, John Jones, father of Mrs. J. B. Lankershim and M. G. Jones, carried on a wholesale grocery business. Jones had left England for Australia, when forty-seven years old, and a year later touched the coast of California at Monterey and came to Los Angeles. Twice a year, Jones went north in a schooner, for the purpose of replenishing his stock; and after making his purchases and having the boat loaded, he would return to Los Angeles. Sometimes he traveled with the round-bellied, short and jolly Captain Morton who recalled his illustrious prototype, Wouter van Twiller, so humorously described by Washington Irving as "exactly five feet six inches in height, and six feet five inches in circumference;" sometimes he sailed with Captain J. S. Garcia, a good-natured seaman. During his absence, the store remained closed; and as this trip always required at least six weeks, some idea may be obtained of the Sleepy Hollow methods then prevailing in this part of the West. In 1854 or 1855, Jones, who was reputed to be worth some fifty thousand dollars, went to San Francisco and married Miss Doria Deighton, and it was generally understood that he expected to settle there; but having been away for a couple of years, he returned to the City of the Angels, this being one of the first instances within my observation of the irresistible attraction of Los Angeles for those who have once lived here. It is my recollection that Jones bought from John G. Downey the Cristóbal Aguilar home then occupied by W. H. and Mrs. Perry; a building the more interesting since it was understood to have served, long in the past and before the American occupation, as a calabozo or jail, and to have had a whipping-post supposed to have done much service in keeping the turbulently-inclined natives quiet. How many of the old adobes may at times have been used as jails, I am unable to say, but it is also related that there stood on the hill west of the Plaza another cuartel, afterward the home of B. S. Eaton, where Fred, later Mayor of Los Angeles, was born. Like Felix Bachman and others, Jones entered actively into trade with Salt Lake City; and although he met with many reverses—notably in the loss of Captain Morton's Laura Bevan, which sank, carrying down a shipload of uninsured goods—he retired well-to-do.

John, sometimes called Juan Temple—or Jonathan, as he used to sign himself in earlier years—who paid the debt of Nature in 1866, and after whom Temple Street is named, was another merchant, having a store upon the piece of land (later the site of the Downey Block, and now occupied by the Post Office) which, from 1849 to 1866, was in charge of my friend, Don Ygnácio Garcia, his confidential business agent. Garcia imported from Mexico both serapes and rebozos; and as every Mexican man and woman required one of these garments, Temple had a large and very lucrative trade in them alone. Following the death of Temple, Garcia continued under Hinchman, the executor of the estate, until everything had been settled.

It was really far back in 1827 when Temple came to Los Angeles, started the first general merchandise store in town, and soon took such a lead in local affairs that the first Vigilance Committee in the city was organized in his store, in 1836. Toward the fifties, he drifted south to Mexico and there acquired a vast stretch of land on the coast; but he returned here, and was soon known as one of the wealthiest, yet one of the stingiest men in all California. His real estate holdings in or near Los Angeles were enormous; but the bad judgment of his executor cost him dear, and valuable properties were sacrificed. After his death, Temple's wife—who once accompanied her husband to Paris, and had thus formed a liking for the livelier French capital—returned to France with her daughter, later Doña Ajuria, to live; and A. F. Hinchman, Temple's brother-in-law, who had been Superintendent of Santa Bárbara County Schools, was appointed administrator. Hinchman then resided in San Diego, and was intensely partial to that place. This may have prejudiced him against Los Angeles; but whatever the cause, he offered Temple's properties at ridiculous prices, and some of the items of sale may now be interesting.

The present site of the Government Building, embracing as it then did the forty-foot street north of it, was at that time improved with an adobe building covering the entire front and running back to New High Street; and this adobe, known after Temple's death as the Old Temple Block, Hinchman sold for fifteen thousand dollars. He also disposed of the new Temple Block, including the improvement at the south end which I shall describe, for but sixteen thousand dollars. I remember quite well that Ygnácio Garcia was the purchaser, and that, tiring of his bargain in a couple of weeks, he resold the property to John Temple's brother, Francisco, at cost.

Hinchman, for fourteen thousand dollars, also disposed of the site of the present Bullard Block, whereon Temple had erected a large brick building, the lower part of which was used as a market while the upper part was a theater. The terms in each of these three transactions were a thousand dollars per annum, with interest at ten per cent. He sold to the Bixbys the Cerritos rancho, containing twenty-six thousand acres, for twenty thousand dollars. Besides these, there were eighteen lots, each one hundred and twenty by three hundred and thirty feet, located on Fort Street (now Broadway), some of which ran through to Spring and others to Hill, which were bought by J. F. Burns and William Buffum for one thousand and fifty dollars, or fifty dollars each for the twelve inside and seventy-five dollars each for the six corner lots.

Returning to the Fort Street lots, it may be interesting to know that the property would be worth to-day—at an average price of four thousand dollars per foot—about nine million dollars. Eugene Meyer purchased one of the lots (on the west side of Fort Street, running through to Hill, one hundred and twenty by three hundred and thirty feet in size), for the sum of one thousand dollars; and I paid him a thousand dollars for sixty feet and the same depth. In 1874 I built on this site the home occupied by me for about twelve years, after which I improved both fronts for F. L. Blanchard. These two blocks are still in my possession; the Broadway building is known as Blanchard Hall. Blanchard, by the way, a comer of 1886, started his Los Angeles career in A. G. Bartlett's music store, and has since always been closely identified with art movements. He organized the system of cluster street-lights in use here and was an early promoter of good roads.

Charles L. Ducommun was here in business in 1853, he and John G. Downey having arrived together, three years before. According to the story still current, Ducommun, with his kit and stock as a watchmaker, and Downey, with his outfit as a druggist, hired a carreta together, to transport their belongings from San Pedro to Los Angeles; but the carreta broke down, and the two pilgrims to the City of the Angels had to finish their journey afoot. Ducommun's first store, located on Commercial Street between Main and Los Angeles, was about sixteen by thirty feet in size, but it contained an astonishing assortment of merchandise, such as hardware, stationery and jewelry. Perhaps the fact that Ducommun came from Switzerland, then even more than now the chief home of watchmaking, explains his early venture in the making and selling of watches; however that may be, it was to Charlie Ducommun's that the bankrupt merchant Moreno—later sentenced to fourteen or fifteen years in the penitentiary for robbing a Frenchman—came to sell the Frenchman's gold watch. Moreno confessed that he had organized a gang of robbers, after his failure in business, and had murdered even his own lieutenants. Ducommun, pretending to go into a rear room for the money, slipped out of the back door and gave the alarm. Ducommun's store was a sort of curiosity-shop containing many articles not obtainable elsewhere; and he was clever enough, when asked for any rarity, to charge all that the traffic would bear. I wonder what Charlie Ducommun would say if he could return to life and see his sons conducting a large, modern wholesale hardware establishment on an avenue never thought of in his day and where once stretched acres of fruit and vine lands! Ducommun Street commemorates this pioneer.

Ozro W. Childs, who came to Los Angeles in November, 1850, was for awhile in partnership with J. D. Hicks, the firm being known as Childs & Hicks. They conducted a tin-shop on Commercial Street, in a building about twenty by forty feet. In 1861, H. D. Barrows joined them, and hardware was added to the business. Somewhat later the firm was known as J. D. Hicks & Company. In 1871, Barrows bought out the Childs and Hicks interests, and soon formed a partnership with W. C. Furrey, although the latter arrived in Los Angeles only in 1872. When Barrows retired, Furrey continued alone for several years. The W. C. Furrey Company was next organized, with James W. Hellman as the active partner of Furrey, and with Simon Maier, the meat-packer and brother of the brewer, and J. A. Graves as stockholders. Hellman, in time, succeeded this company and continued for himself. When Childs withdrew, he went in for importing and selling exotic trees and plants, and made his home place, in more modern days known as the Huntington Purchase and running from Main to Hill and Eleventh to Twelfth streets, wonderfully attractive to such tourists as then chanced this way; he also claimed to be the pioneer floriculturist of Los Angeles County. Toward the end of his life, Childs erected on Main Street, south of First, a theater styled an opera house and later known as the Grand, which was popular in its time. Childs Avenue bears the family name.

Labatt Brothers had one of the leading dry goods houses, which, strange as it may seem, they conducted in a part of the Abel Stearns home, corner of Main and Arcadia streets, now occupied by the Baker Block. Their establishment, while the most pretentious and certainly the most specialized of its day in town, and therefore patronized by our well-to-do people, would nevertheless make but a sorry appearance in comparison with even a single department in any of the mammoth stores of to-day.

Jacob Elias was not only here in 1853, in partnership with his brother under the firm name of Elias Brothers, but he also induced some of his friends in Augusta, Georgia, to migrate to California. Among those who came in 1854 were Pollock, whose given name I forget, and L. C., better known as Clem Goodwin. The latter clerked for awhile for Elias Brothers, after which he associated himself with Pollock under the title of Pollock & Goodwin. They occupied premises at what was then the corner of Aliso Street and Nigger Alley, and the site, some years later, of P. Beaudry's business when we had our interesting contest, the story of which I shall relate in due time. Pollock & Goodwin continued in the general merchandise business for a few years, after which they returned to Augusta. Goodwin, however, came back to California in 1864 a Benedick, and while in San Francisco accidentally met Louis Polaski who was then looking for an opening. Goodwin induced Polaski to enter into partnership with him, and the well-known early clothing house of Polaski & Goodwin was thus established in the Downey Block. In 1867, they bought out I. W. Hellman and moved over to the southeast corner of Commercial and Main streets. Goodwin sold out to Polaski in 1881, when the firm became Polaski & Sons; in 1883 Sam, Isidor and Myer L. Polaski bought out their father, and in time Polaski Brothers also withdrew. Goodwin became Vice-president of the Farmers & Merchants Bank. Polaski died in 1900, Goodwin having preceded him a short time before. Goodwin left his wife some valuable property, and as they were without issue, she so richly endowed the Children's Hospital, at her death, that the present building was made possible.

The Lanfranco brothers—Juan T. and Mateo—came from Genoa, Italy, by way of Lima, Peru and New York, whence they crossed the Plains with James Lick the carpenter later so celebrated, and they were both here in business in 1853; Juan, a small capitalist or petit rentier, living where the Lanfranco Building now stands, opposite the Federal Building, while Mateo kept a grocery store on Main Street, not far from Commercial. In 1854, Juan added to his independence by marrying Señorita Petra Pilar, one of fourteen children of Don José Loreto Sepúlveda, owner of the Palos Verdes rancho; the celebration of the nuptials, in dancing and feasting, lasting five days. It was at that ranch that a great stampede of cattle occurred, due to fright when the pioneer sulky, imported by Juan Lanfranco from San Francisco, and then a strange object, was driven into their midst. About 1861, the first Lanfranco Building was erected. Mateo died on October 4th, 1873, while Juan passed away on May 20th, 1875. His wife died in 1877. A daughter married Walter Maxwell; a second daughter became the wife of Walter S. Moore, for years Chief of the Fire Department; and still another daughter married Arthur Brentano, one of the well-known Paris and New York booksellers.

Solomon Lazard and Maurice Kremer, cousins of about the same age, and natives of Lorraine, were associated in 1853 under the title of Lazard & Kremer, being located in a storeroom in Mellus's Row, and I may add that since nearly all of the country development had taken place in districts adjacent to San Gabriel, El Monte and San Bernardino, travel through Aliso Street was important enough to make their situation one of the best in town. Lazard had arrived in San Francisco in 1851, and having remained there about a year, departed for San Diego, where it was his intention to engage in the dry goods business. Finding that there were not enough people there to maintain such an establishment of even moderate proportions, Lazard decided upon the advice of a seafaring man whom he met to remove his stock, which he had brought from the Northern town, to Los Angeles. He told me that he paid fifty-six dollars' steamer fare from San Francisco to San Diego, and that the freight on his merchandise cost him twenty dollars a ton. Among his native friends, Lazard was always known as Don Solomon, and being popular, he frequently acted as floor-manager at balls and fandangos. Lazard is still living at the good old age of eighty-seven years. Kremer also reached here in 1852. In time, Timoteo Wolfskill, a son of William Wolfskill, bought Kremer's interest, and the firm name became Lazard & Wolfskill. Each of these worthy pioneers in his day rendered signal service to the community—Lazard serving as Councilman in 1862; and I shall have occasion, therefore, to refer to them again. Abe Lazard, a brother of Solomon, who had spent some years in South America, came in the late fifties. Dr. E. M. Lazard is a son of S. Lazard.

While speaking of San Diego, I may remark that it was quite fifteen years before the interesting old Spanish settlement to the South, with which I had no business relations, attracted me; and as I was no exception, the reader may see how seldom the early settlers were inclined to roam about merely for sight-seeing.

In 1853, M. Norton and E. Greenbaum sold merchandise at the southwest corner of Los Angeles and Commercial streets (when Jacob, J. L., an early Supervisor and City Treasurer, 1863-64 and Moritz Morris, Councilman in 1869-70, were competitors). In time, Jacob returned to Germany, where he died. Herman Morris, a brother, was a local newspaper reporter. Jacob Letter was another rival, who removed to Oakland. Still another dealer in general merchandise was M. Michaels, almost a dwarf in size, who emigrated to South America. Casper Behrendt—father-in-law of John Kahn, a man prominent in many movements—who arrived in 1851, was another Commercial Street merchant. Still other early merchants whom I somewhat distinctly recall were Israel Fleishman and Julius Sichel, who had a glassware, crockery and hardware business; and L. Lasky, on Commercial Street.

Thomas D. Mott, father of John Mott, the attorney, who was lured to California by the gold-fever of 1849, and to Los Angeles, three years later, by the climate, I met on the day of my arrival. His room adjoined my brother's store, so that we soon formed an acquaintanceship which ripened, in the course of time, into a friendship that endured until the day of his death. In the early sixties, he was the proprietor of a livery stable on Main Street, opposite the Stearns home. He was very fond of hunting, being an expert at dropping a bird on the wing; and frequently went dove-shooting with his friends.

All of which, insignificant as it may at first appear, I mention for the purpose of indicating the neighborhood of these operations. The hunting-ground covered none other than that now lying between Main and Olive streets from about Sixth Street to Pico, and teeming to-day, as the reader knows, with activity and life. There sportsmen hunted, while more matter-of-fact burghers frequently went with scythes to cut grass for their horses.

Prudent Beaudry, a native of Quebec destined to make and lose several fortunes, was here when I came, having previously been a merchant in San Francisco when staple articles—such as common tacks, selling at sixteen dollars a package!—commanded enormous prices. Two or three times, however, fire obliterated all his savings, and when he reached Los Angeles, Beaudry had only about a thousand dollars' worth of goods and two or three hundred dollars in cash. With these assets he opened a small store on Main Street, opposite the Abel Stearns home; and again favored by the economic conditions of the times, he added to his capital very rapidly. From Main Street Beaudry moved to Commercial, forming partnerships successively with a man named Brown and with one Le Maître. As early as 1854, Beaudry had purchased the property at the northeast corner of Aliso Street and Nigger Alley for eleven thousand dollars, and this he so improved with the additional investment of twenty-five thousand dollars that he made his now elongated adobe bring him in an income of a thousand a month. As stated elsewhere, Beaudry went to Europe in 1855, returning later to Montreal; and it was not until 1861 or later that he came back to Los Angeles and reëngaged in business, this time in his own building where until 1865 he thrived, withdrawing, as I shall soon show, in the beginning of 1866. Beaudry Avenue recalls this early and important man of affairs.

David W. Alexander, Phineas Banning's enterprising partner in establishing wagon-trains, was here when I came and was rather an influential person. An Irishman by birth, he had come to California from Mexico by way of Salt Lake, in the early forties, and lived for awhile in the San Bernardino country. From 1844 to 1849, John Temple and he had a store at San Pedro, and still later he was associated in business with Banning, selling out his interest in 1855. In 1850, Alexander was President of the first Common Council of Los Angeles, being one of the two members who completed their term; in 1852, he visited Europe; and in September, 1855, he was elected Sheriff of the County, bringing to his aid the practical experience of a Ranger. Before keeping store, Alexander had farmed for awhile on the Rincon rancho; he continued to hold a large extent of acreage and in 1872 was granted a patent to over four thousand acres in the Providencia, and in 1874 to nearly seventeen thousand acres in the Tejunga rancho. George C. Alexander, David's brother, was Postmaster at San Pedro in 1857.

The Hazards arrived in 1853 with a large family of children, Captain A. M. Hazard having made his way with ox-teams from the East, via Salt Lake, on a journey which consumed nearly two years. At first they took up a claim about four miles from Los Angeles, which was later declared Government land. The eldest son, Daniel, was employed by Banning as a teamster, traveling between Los Angeles and Yuma; but later he set up in the teaming business for himself. George W. Hazard became a dealer in saddlery in Requena Street; and taking an active interest in the early history of Los Angeles, he collected, at personal sacrifice, souvenirs of the past, and this collection has become one of the few original sources available for research.[4] In 1889, Henry T. Hazard, after having served the City as its Attorney, was elected Mayor, his administration being marked by no little progress in the town's growth and expansion. Henry, who married a daughter of Dr. William Geller, and after whom Hazard Street is named, is the only one of the brothers who survives.

Sam Meyer, who met me, as related, when I alighted from the stage, was another resident of Los Angeles prior to my coming. He had journeyed from Germany to America in 1849, had spent four years in New Orleans, Macon, and other Southern cities, and early in 1853 had come to California. On Main Street, south of Requena, I found him, with Hilliard Loewenstein, in the dry goods business, an undertaking they continued until 1856, when Loewenstein returned to Germany, to marry a sister of Meyer. Emanuel Loewenstein, one of the issue of this marriage, and a jolly, charitable fellow, is well known about town. On December 15th, 1861, Meyer married Miss Johanna,[5] daughter of S. C. and Rosalia Davis, and the same year formed a partnership with Davis in the crockery business. After two and a half years of residence in Germany, Loewenstein returned to Los Angeles. Meyer, so long identified with local freemasonry, died in 1903. A daughter married Max Loewenthal, the attorney.

Baruch Marks, one of the very few people yet living who were here when I arrived, is now about ninety-one years of age, and still[6] a resident of Los Angeles. He was with Louis Schlesinger (who lost his life when the Ada Hancock was destroyed) and Hyman Tischler in the general merchandise business in 1853 at Mellus's Row, the firm being known as B. Marks & Company; and having prospered, he went to Berlin. There, after the Franco-Prussian War, when much disaster befell speculators, he lost most of his means; and greatly reduced in resources, he returned to Los Angeles. Since then, however, he has never been able to retrieve his fortune. Luckily he enjoys good health, even being able at his advanced age, as he told me recently, to shave himself.

In 1851, Herman Schlesinger reached Los Angeles and engaged in the dry goods business with Tobias Sherwinsky. In 1855, Moritz Schlesinger, Herman's brother, came here and clerked for the firm. In 1857, Schlesinger & Sherwinsky, having made, approximately, fourteen thousand dollars, which they divided, sold out to Moritz Schlesinger and returned to Germany. A few years later Sherwinsky lost his money and, coming back to California, located in San Diego where he died. Schlesinger remained in Germany and died there, about 1900.

Collins Wadhams had a general store on the northeast corner of Main and Commercial streets—a piece of property afterward bought by Charlie Ducommun. At another time, Wadhams & Foster were general merchants who, succeeding to the business of Foster & McDougal, were soon followed by Douglass, Foster & Wadhams. Clerking for this firm when I came was William W. Jenkins, who left for Arizona, years afterward, where he led an adventurous life.

Henry G. Yarrow, often called Cuatro Ojos or four eyes, from the fact that he wore a pair of big spectacles on a large hooked nose, was an eccentric character of the fifties and later. He once conducted a store at the southwest corner of Los Angeles and Requena streets, and was the Jevne of his day in so far as he dealt in superior and exceptional commodities generally not found in any other store. In other respects, however, the comparison fails; for he kept the untidiest place in town, and his stock was fearfully jumbled together, necessitating an indefinite search for every article demanded. The store was a little low room in an adobe building about twenty feet long and ten feet wide, with another room in the rear where Yarrow cooked and slept. He was also a mysterious person, and nobody ever saw the inside of this room. His clothes were of the commonest material; he was polite and apparently well-bred; yet he never went anywhere for social intercourse, nor did he wish anyone to call upon him except for trade. Aside from the barest necessities, he was never known to spend any money, and so he came to be regarded as a miser. One morning he was found dead in his store, and for some time thereafter people dug in his backyard searching for the earnings believed to have been secreted there; but not a cent of his horde was ever found. There were all kinds of rumors, however, respecting Yarrow. One was to the effect that he was the scion of a noted English family, and that disappointment in love had soured and driven him from the world; while another report was that his past had been somewhat shady. Nobody, apparently, knew the truth; but I personally believe that Yarrow was honest, and know that when at one time, despite his efforts, he failed in business, he endeavored to settle his debts upon the most honorable basis.

Charles Hale, later associated with M. W. Childs, had a tin-shop just where Stearns's Arcadia Block now stands. This shop stood on elevated ground, making his place of business rather difficult of access; from which the reader will gain some idea of the irregular appearance of the landscape in early days. Hale in time went to Mexico, where he was reported to have made a fortune.

August Ulyard arrived with his wife on the last day of December, 1852, and rented a house near the Plaza. In competition with Joseph Lelong, who had established his Jenny Lind bakery a couple of years previous, Ulyard opened a bake-shop, making his first bread from yeast which Mrs. Ulyard had brought with her across the Plains. There had been nothing but French bread in Los Angeles up to that time, but Ulyard began to introduce both German and American bread and cake, which soon found favor with many; later he added freshly-baked crackers. After a while, he moved to the site of the Natick House, at the southwest corner of Main and First streets; and once he owned the southwest corner of Fifth and Spring streets, on which the Alexandria Hotel now stands. Having no children of their own, Ulyard and his wife adopted first one and then another, until eventually they had a family of seven!

Picturing these unpretentious stores, I recall a custom long prevalent here among the native population. Just as in Mexico a little lump of sugar called a pilon, or something equally insignificant, was given with even the smallest purchase, so here some trifle, called a pilon, was thrown in to please the buyer. And if a merchant neglected to offer such a gratuity, the customer was almost certain to ask for it.

Among the meat-handlers, there were several Sentous brothers, but those with whom I was more intimately acquainted were Jean and Louis, father of Louis Sentous the present French Consul, both of whom, if I mistake not, came about the middle of the fifties. They engaged in the sheep business; and later Louis had a packing-house of considerable importance located between Los Angeles and Santa Monica, where he also owned over a thousand acres of valuable land which he sold some time before his death. They were very successful; and Sentous Street bears their name. Jean died in 1903, and Louis a few years later.

Refúgio Botello was another wholesale cattle- and meat-dealer.

Arthur McKenzie Dodson, who came here in 1850 and later married Miss Reyes, daughter of Nasário Dominguez, conducted a butcher shop and one of the first grocery stores. He was also the first to make soap here. For a while Dodson was in partnership with John Benner who, during a quarter of a century when in business for himself, in the old Temple adobe on Main Street, built up an important trade in the handling of meat. James H. Dodson is Arthur's son.

Santiago Bollo also kept a small grocery.

"Hog" Bennett was here in the middle fifties. He raised and killed hogs, and cured the ham and bacon which he sold to neighboring dealers.

Possessed as he was of an unusual sense of rectitude, I esteemed Francisco Solano, father of Alfredo Solano, for his many good qualities. He was in the butcher business in Sonora Town, and was prosperous in the early fifties.

An odd little store was that of Madame Salandie, who came to California in 1849, on the same vessel that brought Lorenzo Leck. She had a butcher shop; but, rather curiously, she was also a money-lender.

I believe that Jack Yates was here in 1853. He owned the first general laundry, located on Los Angeles Street between First and Requena, and conducted it with success and profit for many years, until he succumbed to the competition of the Chinese. Yates's daughter, Miss Mary D., married H. J. Woollacott, at one time a prominent financier.

More than once, in recording these fragmentary recollections, I have had occasion to refer to persons who, at one time or another, were employed in a very different manner than in a later period of their lives. The truth is that in the early days one's occupation did not weigh much in the balance, provided only that he was honorable and a good citizen; and pursuits lowly to-day were then engaged in by excellent men. Many of the vocations of standing were unknown, in fact, fifty or sixty years ago; and refined and educated gentlemen often turned their attention to what are now considered humble occupations.