And Radoub took his seat. His wound had reopened. A thin stream of blood oozed from under the bandage, from the place where his ear had been, and ran along his neck.

Cimourdain turned towards Radoub.

"You vote that the accused be acquitted?"

"I vote to have him made general," replied Radoub.

"I ask you whether you vote for his acquittal."

"I vote that he be made the head of the Republic."

"Sergeant Radoub, do you, or do you not, vote for Captain Gauvain's acquittal? Yes, or no?"

"I vote that you behead me in his place."

"Acquittal," said Cimourdain. "Write it down, clerk."

Then the clerk announced,—

"One vote for death, one for acquittal: a tie."

It was Cimourdain's turn to vote.

He rose, took off his hat, and placed it on the table. He was no longer pale or livid; his face was the color of clay.

Had every man present been lying in his shroud, the silence could not have been more profound.

In solemn, measured tones Cimourdain said,—

"Gauvain, the accused, your case has been heard. The court-martial, in the name of the Republic, by a majority of two against one—"

He broke off; he seemed to pause. Was he still doubtful whether to vote for death or for life? The audience was breathless. Cimourdain went on,—

"—condemns you to the penalty of death."

His face revealed the torture of an awful triumph. When Jacob in the darkness forced a blessing from the angel whom he had overthrown, he must have worn the same terrible smile.

It passed like a flash, however, and Cimourdain again became marble. He took his seat, replaced his hat on his head, and added,—

"Gauvain, you will be executed to-morrow at sunrise."

Gauvain rose, bowed, and said,—

"I thank the court."

"Remove the prisoner," said Cimourdain; and at a sign from him the door of the dungeon was reopened, Gauvain entered, and it closed behind him. Two gendarmes with drawn sabres were stationed on each side of the door.

Radoub, who had just fallen senseless, was carried away.

A camp is a wasps nest, especially in time of revolution. The civic sting which exists in the soldier darts forth at a moments notice, and after driving out the enemy, will often turn without ceremony upon its own chief. The brave army which had taken the Tourgue was alive with conflicting rumors. When first the escape of Lantenac was discovered, it was all against Gauvain; but when the latter was seen coming out of the dungeon where they had supposed Lantenac to be imprisoned, it was like the transmission of an electric spark, and in less than a minute the whole army knew of it. A murmur broke forth from the little band; at first it ran: "They are getting ready to try Gauvain. But it is all a farce. He is a fool who trusts these ci-devants and calotins! We have just seen a Viscount save a Marquis, and presently we shall see a priest acquit a noble!"

When the condemnation of Gauvain became known, there was a second murmur: "That is an outrage! Our chief, our brave chief, our young commander, a hero! He is a Viscount, to be sure, but so much more to his credit that he is also a Republican! What, he, the liberator of Pontorson, of Villedieu, of Pont-au-Beau: the conqueror of Dol and of the Tourgue! the man who has made us invincible! the sword of the Republic in the Vendée,—he who for five months holds his own against the Chouans, and corrects all the blunders of Léchelle and others! And Cimourdain dares to condemn him! Wherefore? Because he saved an old man who had rescued three children! Does it become a priest to put a soldier to death?"

Thus murmured the victorious and dissatisfied camp. On every side a dull sense of anger prevailed against Cimourdain. Four thousand men against one might be supposed to constitute a power; but it does not. These four thousand men were nothing more than a crowd; Cimourdain was a will. They all knew that his frown was easily provoked, and this knowledge sufficed to hold the army in awe. In those times it needed but the shadow of the Committee of Public Safety behind a man to make him formidable, and to convert an imprecation into a whisper, and that whisper into silence. Before, as well as after their murmuring, Cimourdain was absolute master of the fate of all, as well as of that of Gauvain. They knew that it would be vain to entreat him; that he would listen only to his conscience,—that superhuman voice audible to himself alone. Everything depended upon him. What he had done simply in his capacity of military judge, he could undo as civil delegate. He alone could pardon; there were no limits to his authority; it needed but a sign from him to set Gauvain at liberty; life and death were in his hands; the guillotine was at his command. In this tragic moment he held supreme authority.

There was no resource but to wait.

The night came.

Once more the hall of justice was changed into a guard-room; and as on the previous evening, the sentinels were doubled, two of whom guarded the door of the closed dungeon.

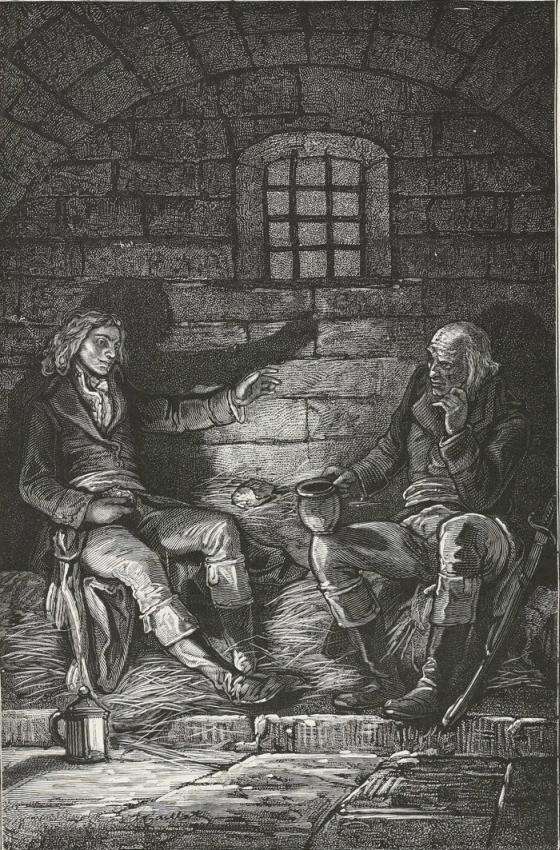

Toward midnight, a man, bearing a lantern in his hand, crossed the guard-room, where he made himself known, and ordered the dungeon to be opened. It was Cimourdain. He entered, leaving the door half open behind him. The dungeon was dark and silent. Taking one step forward in the gloom, he placed the lantern on the ground and stood still. The even breathing of a sleeping man could be heard through the darkness. Cimourdain stood dreamily listening to this peaceful sound.

On the truss of straw at the farther end of the dungeon lay Gauvain sound asleep. It was his breathing that he heard.

Cimourdain moved as noiselessly as possible, and when he had drawn near, he fixed his eyes upon Gauvain; no mother gazing upon her sleeping infant could have worn a look more unutterably tender. The expression was probably beyond his control; he pressed his clenched hands against his eyes as children sometimes do, and for a moment stood perfectly still. Then he knelt, gently lifted Gauvain's hand, and carried it to his lips.

Gauvain stirred. He opened his eyes, with the vague surprise of sudden waking. The feeble glimmer of a lantern dimly lighted the dungeon. He recognized Cimourdain.

"Ah, is that you, master?" he said.

Then he added,—

"I dreamed that Death was kissing my hand."

A sudden influx of thoughts will now and then startle a man, and so it was with Cimourdain; at times this wave rolls in so tumultuously that it threatens to submerge the soul. But Cimourdain's deep soul gave forth no sign; he could but utter the word "Gauvain!"

And the two men stood gazing at each other—Cimourdain's eyes alight with flames that scorched his tears, Gauvain with his sweetest smile.

Gauvain raised himself on one elbow, and said:—

"That scar I see on your face is the sabre-cut you received in my stead. It was but yesterday you stood beside me in the mêlée, and all for my sake. If Providence had not placed you by my cradle, where should I be to-day? In ignorance. If I have any sense of duty, it is to you that I owe it. I was born in fetters,—I mean the bonds of prejudice,—which you have loosened; you promoted my free development, and from the mummy you have created a child. You have implanted a conscience in a being who bade fair to prove an abortion. Without you my growth would have been cramped; it is through your influence that I live. I was but a lord, you have made of me a citizen; I was only a citizen, you have made of me a mind; you have fitted me to lead the life of a man upon the earth, and have shown my soul the way to heaven. It is you who placed in my hands the key of truth that unlocks the domain wherein we find the realities of human life, and the key of light to the realms above. I thank you, my master! To you I owe my life."

Cimourdain, seating himself on the straw beside Gauvain, said,—

"I have come to sup with you."

Gauvain broke the black bread and offered it to him. After Cimourdain had taken a piece, Gauvain handed him the jug of water.

"Drink first yourself," said Cimourdain.

Gauvain drank, and then passed the jug to Cimourdain, who drank after him.

Gauvain had taken but a swallow.

Cimourdain took deep draughts.

During this supper Gauvain ate, and Cimourdain drank,—a proof of the calmness of the one, and of the burning fever of the other.

A certain awful tranquillity pervaded this dungeon. The two men conversed.

"Gauvain was saying,—

"Grand events are taking form. No one can comprehend the mysterious workings of revolution at the present time. Behind the visible achievement rests the invisible, the one concealing the other. The visible work seems cruel; the invisible is sublime. At this moment I can see it all very clearly. It is strange and beautiful. We have been forced to use the materials of the Past. Hence this wonderful '93. Beneath a scaffolding of barbarism we are building the temple of civilization.

"Yes," replied Cimourdain, "these temporary expedients pave the way for the final adjustment, wherein justice and duty stand side by side, where taxation will be proportionate and progressive, and military service compulsory; where there is to be absolute equality in rank; and where, above all things else, the straight line of the Law is to be maintained,—the republic of the absolute."

"I prefer the republic of the ideal," said Gauvain.

He broke off, then continued:—

"But, oh, my master, where in the picture you have just drawn in words do you place devotion, sacrifice, abnegation, the sweet intermingling of kindliness and love? An accurate adjustment of proportions is a good thing, but harmony is still better. The lyre stands higher than the scales. Your republic deals with the material interest of man; mine transports him to the skies: it is like the difference between a theorem and an eagle."

"You are lost in the clouds."

"And you in your calculations."

"There is an element of dreaminess in harmony."

"So there is in algebra."

"I would have man fashioned according to Euclid."

"And I like him better as described by Homer."

The stern smile of Cimourdain rested on Gauvain as though to stay the flight of his soul.

"Poetry. Beware of poets!"

"Yes; that is a familiar warning: beware zephyrs, beware of sunbeams, beware of perfumes, beware of flowers, beware of the stars."

"That sort of thing can never supply us with food."

"How can you tell? There is mental nourishment: a man finds food in thought."

"Let us indulge in no abstractions! The republic is like two and two in mathematics: two and two make four. When I have given to each man his due—"

"Then your duty is to give him what does not revert to him as a right."

"What do you mean by that?"

"I mean those mutual concessions which each man owes his neighbor, and which go to make up the sum of social life."

"There is nothing beyond the just limits of the law."

"Ah, but there is—everything!"

"I see nothing but justice."

"I look higher."

"What stands higher than justice?"

"Equity."

Now and then both paused, as though a sudden light had flashed across their minds.

Cimourdain continued,—

"Explain your assertion. I challenge you to do it."

"Very well, then. You demand compulsory military service. Against whom? Against mankind. I object to military service; I would have peace. You desire to help the wretched; what I wish is the abolition of their misery. You demand proportionate taxation; I would have no taxes whatsoever. I would have the public expenses reduced to the lowest level, and paid for by the social surplus."

"What do you mean by that?"

"This: In the first place, it is for you to suppress sycophancy,—that of the priest, the soldier, and the judge. Then, use your wealth to the best advantage; distribute over your furrows all that fertilizing matter which is now thrown into your sewers. Three quarters of the soil lies fallow; plough it up; redeem the waste pastures; divide the communal lands; let each man have a farm, and each farm a man. You will increase a hundredfold the social product. At the present time, France affords her peasants meat but four times a year; well cultivated, she could feed three millions of men, all Europe. Utilize nature, that gigantic auxiliary; enlist every breeze, every waterfall, every magnetic current, in your service. This globe has a subterranean network of veins, through which flows a marvellous circulation of water, oil, and fire; pierce this vein of the globe, and let the water feed your fountains, the oil your lamps, and the fire your hearths. Consider the action of the waves,—the ebb and flow of the tides. What is the ocean? A prodigious force wasted. How stupid is the earth, to make no use of the ocean!"

"There you go, in full career with your dreams!"

"You mean with my realities."

Gauvain continued,—

"And woman,—how do you dispose of her?"

Cimourdain replied,—

"Leave her as she is,—the servant of man."

"Yes, under one condition."

"What is that?"

"That man shall be the servant of woman."

"What are you thinking of?" exclaimed Cimourdain. "Man a servant? Never! Man is the master. I admit but one kingdom,—that of the fire-side. Man is king in his own home."

"Yes, on one condition."

"What is that?"

"That woman shall be its queen."

"You mean that you demand for both man and woman—"

"Equality."

"'Equality'! Can you dream of such a thing? The two beings are so entirely unlike!"

"I said equality, not identity."

There was another pause, a sort of truce as it were, between these two minds exchanging their lightning flashes. Cimourdain broke it.

"And the child? To whose care would you intrust that?"

"First to the father who begets, then to the mother who gives him birth, later to the master who educates, and to the city that makes a man of him, then to the country which is his supreme mother, and lastly to humanity which is his great ancestress."

"You have not mentioned God."

"Each step—father, mother, master, city, country, humanity—is but a rung in the ladder that leads to God."

Cimourdain was silent, while Gauvain continued:

"When one climbs to the top of the ladder one has reached God. God is revealed, and one has but to enter into heaven."

Cimourdain made the gesture of one who calls another back: "Gauvain, return to earth. We want to realize the possible."

"Do not begin then by making it impossible."

"The possible may always be realized."

"Not always. Rough usage destroys Utopia. Nothing is more defenceless than the egg."

"Still, Utopia must be seized and forced to wear the yoke of reality; she must be circumscribed by a system of actual facts. The abstract must be resolved into the concrete: what it loses in beauty it gains in usefulness; although contracted, it is improved. Justice must enter into law; and when justice has become law, it is absolute. That is what I call the possible."

"The possible includes more than that."

"Ah, there you go again, soaring away into the land of dreams!"

"The possible is a mysterious bird, always hovering above the head of man."

"We must catch it."

"And take it alive too."

Gauvain continued:—

"My idea is this: Ever onward. If God had intended that man should go backwards He would have given him an eye in the back of his head. Let us look always towards the dawn, the blossom-time, the hour of birth. Those things which are falling to decay encourage the new springing life. In the splitting of the old tree may be heard a summons to the new one. Each century will do its work,—civic, to-day; humane, to-morrow: to-day, the question of justice; to-morrow, that of compensation. Wages and Justice are in point of fact synonymous terms. Man's life is not to be spent without a suitable compensation. When He bestows life, God contracts thereby a debt: justice is the inherent compensation; remuneration is the acquirement thereof."

Gauvain spoke with the calm serenity of a prophet; Cimourdain listened. The parts were changed, and now it seemed as if it were the pupil who had become the master.

Cimourdain murmured,—

"You go at a rapid rate."

"Perhaps because I have no time to lose," replied Gauvain with a smile.

He continued:—

"Ah, master, here is the difference between our two utopias. You would have military service obligatory; I demand the same for education. You dream of man the soldier; I, of man the citizen. You wish him to strike terror; I would have him thoughtful. You establish a republic of swords, while I desire to found—"

He broke off.

"I should like to establish a republic of minds."

Cimourdain looked down on the flag-stones of the dungeon.

"And in the mean time what would you have?" he asked.

"The existing condition of things."

"Then you absolve the present moment."

"Yes."

"Why?"

"Because it is a tempest. A tempest always knows what it is about. For every oak that is struck by lightning, how many forests are purified! Civilization has a plague; a strong wind is sent to expel it from the land. It may not choose its methods wisely, perhaps, but can it do otherwise? Its task is no light one. Viewing the horror of the miasma, I can understand the fury of the wind."

Gauvain went on:—

"But what matters the storm to me, if I have a compass; and what power can events gain over me, if I have my conscience?"

And he added in that undertone which produces so solemn an effect:—

"There is One to whose will we must always yield."

"Who is that?" asked Cimourdain.

Gauvain pointed upwards. Cimourdain looked in the direction of the uplifted finger, and it seemed to him that he could see the starry sky through the dungeon vault.

Once more they relapsed into silence.

Cimourdain continued:—

"A supernatural state of society; I tell you it is no longer possible,—it is a mere dream."

"It is a goal; otherwise, of what use is society? Better remain in a state of nature; be like the savages. Otaheite is a paradise, only in that paradise no one thinks. Better an intelligent hell than a stupid heaven. But, no,—we will have no hell whatever. Let us be a human society. Super-natural? Yes. But if you are to add nothing to Nature, why leave her? In that case you may as well content yourself with work like the ant, and with honey like the bee. Rest content among the laboring classes, instead of rising to the ranks of superior intelligence. If you add anything to Nature, you must of necessity rise above her: to add is to augment; to augment is to increase. Society is the exaltation of Nature. I would have what bee-hives and ant-hills lack,—monuments, arts, poetry, heroes, men of genius. To bear eternal burdens is no fit law for man. No, no, no! let us have no more pariahs, no more slaves, no more convicts, no more lost souls! I would have every attribute of man a symbol of civilization and an example of progress; I would present liberty to the intellect, equality to the heart, fraternity to the soul. Away with the yoke! Man is not made for dragging chains, but that he may spread his wings. Let us have no more of the reptile. Let the larva turn into a butterfly; let the grub change into a living flower and fly away. I wish—"

He broke off. His eyes shone, his lips moved, he said no more.

The door had remained open. Sounds from without penetrated into the dungeon. The distant echo of a trumpet reached their ears,—probably the réveille; then, when the guard was relieved, they heard the butt-ends of the sentinels' muskets striking the ground; again, apparently quite near the tower, so far as the darkness allowed one to judge, a noise like the moving of planks and beams, accompanied by muffled and intermittent sounds resembling the blows of a hammer. Cimourdain turned pale as he listened. Gauvain heard nothing. Deeper and deeper grew his reverie. Hardly did he seem to breathe, so absorbed was he in the visions of his brain. Now and then he moved, like one slightly startled. A gathering brightness shone in his eyes, like the light of dawn.

Some time passed thus.

"Of what are you thinking?" asked Cimourdain.

"Of the future," replied Gauvain.

And he fell back again into his meditation. Unobserved by the latter, Cimourdain rose from the bed of straw whereon they had both been sitting. His eyes rested yearningly upon the young dreamer, while he slowly moved backward towards the door. He went out. The dungeon was again closed.

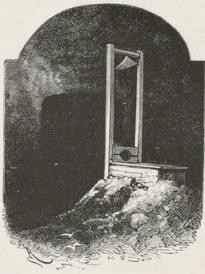

It was not long before day began to dawn on the horizon; and together with the day there sprang to light upon the plateau of the Tourgue, above the forest of Fougères, a strange, stationary, and wonderful object, unfamiliar to the birds of heaven.

It had been placed there during the night,—set up rather than built. From a distance, against the horizon, it presented a profile composed of straight and rigid lines, resembling a Hebrew letter, or one of those Egyptian hieroglyphics which formed part of the alphabet of the ancient enigma.

The first thought that entered the mind at the sight of this object was its uselessness. There it stood, among the blossoming heather. Then came the question, could it be used; and for what purpose? Then came a shudder. It was a sort of trestle-work, supported by four posts. At one end were two long upright beams, united at the top by a cross-beam, from which hung a triangle that looked black against the pale blue of the morning sky. At the other end of this trestle stood a ladder. Between these two beams, beneath the triangle, could be distinguished a sort of panel composed of two movable sections, which, fitting into one another, offered to the eye a round hole about the size of a man's neck. The upper section of the panel ran in a groove, by means of which it could be raised or lowered. For the moment the two semicircles that formed the collar were drawn apart. At the foot of the two pillars supporting the triangle was seen a plank that moved on hinges like a see-saw. Beside the plank stood a long basket, and in front, between the two posts at the end of the staging, a square one. This object was painted red, and made entirely of wood, except the triangle, which was of iron. One might know that it was built by men, so ugly, sordid, and contemptible did it look; and yet so formidable was it that it might well have been transported hither by genii.

This shapeless structure was the guillotine.

In front of it, a few paces off, in the ravine, was another monster, La Tourgue,—a stone monster, companion-piece to the monster of wood. And let us add, that after wood and stone have been manipulated by man they lose something of their original substance, taking on a certain similitude to man himself. A building is a dogma; a machine is an idea.

The Tourgue was that fatal product of the past called in Paris the Bastille, in England the Tower of London, in Germany the Fortress of Spielberg, in Spain the Escurial, in Moscow the Kremlin, and in Rome the Castle of Saint-Angelo.

The Tourgue was the condensation of fifteen hundred years,—the period of the Middle Ages, with its vassalage, its servitude, and its feudality. The guillotine showed forth but one year,—'93; but these twelve months were a fitting counterpoise for those fifteen centuries.

The Tourgue was the personification of monarchy; the guillotine, of revolution.

A tragic encounter.

On the one hand, the debt; on the other, the requirement thereof. All the hopeless entanglement of the Gothic period—the serf, the lord, the slave, the master, the plebeian, the nobility, a complex code with all the ramifications of practice, the coalition of judge and priest, the infinite variety of shackles, fiscal duties, the salt-tax, the mortmain, the poll-tax, the exception, the prerogatives, the prejudices, the fanaticisms, the royal privilege of bankruptcy, the sceptre, the throne, the arbitrary will, the divine right—opposed to that simple thing, a knife.

On one side, a knot; on the other, the axe.

For many a year the Tourgue had stood alone in this desert, and from its battlements had rained the boiling oil, the burning pitch, and the melted lead; there it stood, with its dungeons paved with human bones, its torture-chamber alive with memories of its tragic past. For fifteen centuries of savage tranquillity its gloomy front had towered above the shades of the forest; it had been the only power in the land,—the one thing respected and feared; its reign had been supreme, without a rival in its wild barbarity, when it suddenly saw rising before it, with an aspect of hostility, a thing,—nay, more than a thing; a creature as hideous as itself,—the guillotine.

Stone seems at times endowed with the sense of sight. A statue observes, a tower watches, the front of a building contemplates. The Tourgue seemed to be examining the guillotine.

It was as if questioning itself,—

"What can this object be?"

One might fancy it to have sprung from the soil.

And so, indeed, it had.

Like a poisonous tree it had sprouted from a fatal soil. From that soil so plentifully watered by human sweat, by tears, and by blood, from the soil wherein men had dug countless graves, tombs, caves, and ambushes, from the same soil wherein had rotted the innumerable victims of every kind of tyranny, from that soil covering so great a multitude of crimes, buried like frightful germs in the depths below, had sprung forth, on the appointed day, this stranger, this avenging goddess, this fierce sword-bearing instrument; and '93 cried out to the Old World,—

"Behold me!"

The guillotine had a right to say to the dungeon: "I am thy daughter."

And yet at the same time the keep—for these fatal objects live a certain obscure life—recognized its own death-warrant.

At the sight of this formidable apparition the Tourgue seemed bewildered. One might have called it terror. The immense mass of granite was both majestic and infamous; that plank with its triangle was still more dreadful. Deposed omnipotence felt a horror of the rising power. It was criminal history studying judicial history. The violence of former days was comparing itself with the violence of the present time; the ancient fortress, both the prison and the dwelling of the lords, where the tortured victims had shrieked aloud, this structure devoted to war and murder, now useless and defenceless, violated, dismantled, discrowned, a pile of stones no better than a heap of cinders, hideous to look upon, magnificent in death, dizzy with the vertigo of those terrible centuries, stood watching the passage of the awful living hour. Yesterday shuddered in the presence of To-day. The old ferocity beheld and did homage to the new terror, and that which was mere Nothingness unclosed its spectral eyes before the Terror, and the phantom gazed upon the ghost. Nature is pitiless; she never withholds her flowers, her melodies, her perfumes, her sunbeams, from human abominations. She overwhelms man by the contrast between divine beauty and social ugliness; she spares him nothing, neither the wing of butterfly, nor song of bird; on the verge of murder, in the act of vengeance or barbarity, she brings him face to face with those holy things; nowhere can he escape the eternal reproach of universal benevolence and the implacable serenity of the sky. Human law in all its hideous deformity must stand forth naked in the presence of the eternal radiance. Man breaks and crushes, lays waste, destroys; but the summer, the lily, and the star remain ever the same.

Never had the fair sky of early dawn seemed lovelier than on that morning. A soft breeze stirred the heather, the mist floated lightly among the branches, the forest of Fougères, suffused with the breath of running brooks, smoked in the dawn like a gigantic censer filled with incense; the blue sky, the snowy clouds, the clear transparency of the streams, the verdure, with its harmonious scale of color, from the aqua-marine to the emerald, the social groups of trees, the grassy glades, the far-reaching plains,—all revealed that purity which is Nature's eternal precept unto man. In the midst of all this appeared the awful depravity of man; there stood the fortress and the scaffold, war and punishment, the two representatives of this sanguinary epoch and moment, the screech-owl of the gloomy night of the Past and the bat of the twilight of the Future. In the presence of a world all flowery and fragrant, tender and charming, the glorious sky bathed both the Tourgue and the guillotine with the light of dawn, as though it said to man: "Behold my work, and yours."

The sun wields a formidable weapon in its light.

This spectacle had its spectators.

The four thousand men of the expeditionary army were drawn up on the plateau in battle array. They surrounded the guillotine on three sides, forming themselves around it after a geometrical fashion in the shape of the letter E; the battery placed against the centre of the longest line made the notch of the E. The red machine was, if we may so express it, shut in by these three battle fronts, a wall of soldiers, extending in a sort of coil and spreading as far as the edge of the escarpment of the plateau; the fourth side, left open, was the ravine itself, which looked upon the Tourgue.

This formed an oblong square, in the centre of which stood the scaffold. The shadow cast upon the grass by the guillotine lessened as the sun rose. The gunners with lighted matches stood by their pieces. A faint blue smoke curled upward from the ravine,—the last breath of the dying fire on the bridge.

This smoke obscured without veiling the Tourgue, whose lofty platform overlooked the entire horizon. Only the width of the ravine separated the platform from the guillotine, and voices could easily have been heard between them.

The table of the tribunal and the chair shaded by the tricolored flags had been conveyed to this platform. The sun rising behind the Tourgue brought into relief the black mass of the fortress, and upon its summit, seated on the chair of the tribunal, beneath the group of flags, the figure of a man, motionless, his arms crossed upon his breast.

This man was Cimourdain. He wore, as on the previous evening, his civil delegate's uniform, a hat with the tricolored cockade upon his head, a sabre by his side, and pistols in his belt.

He was silent. The entire assembly was silent likewise. The soldiers, their eyes downcast, stood at order-arms. They touched elbows, but no one spoke. They were thinking vaguely about this war,—the numerous battles, the hedge fusillades so valiantly faced, of the hosts of furious peasants scattered by their prowess, the citadels conquered, the engagements won, the victories; and now it seemed as though all this glory were turned to their shame. A gloomy expectation oppressed every breast. They could see the executioner walking up and down the platform of the guillotine. The growing light of day deepened until it filled the sky with its majestic presence.

Suddenly was heard that muffled sound peculiar to crape-covered drums; nearer and nearer came their funereal roll; the ranks opened, and the procession, entering the square, moved towards the scaffold.

First came the black' drums, then a company of grenadiers with lowered muskets, then a platoon of gendarmes with drawn sabres, then the prisoner, Gauvain.

Gauvain walked without constraint. Neither hands nor feet were bound. He was in undress uniform, and wore his sword.

Behind him marched another platoon of gendarmes.

The same pensive joy that had lighted his face when he said to Cimourdain, "I am thinking of the future," still rested upon it. Nothing could be more sublime and touching than this continued smile.

When he reached the fatal spot, his first glance was turned to the summit of the tower. He disdained the guillotine. He knew that Cimourdain would feel it his duty to be present at the execution; his eyes sought him on the platform and found him there.

Cimourdain was ghastly pale and cold. Even those who stood nearest heard no sound of his breathing.

When he caught sight of Gauvain not a quiver passed over his face; and yet he knew that every step brought him nearer to the scaffold.

As he advanced, Gauvain looked at Cimourdain, and Cimourdain looked at him. It seemed as though Cimourdain found support in that glance.

Gauvain reached the foot of the scaffold. He ascended it, followed by% the officer in command of the grenadiers. He unbelted his sword and handed it to this officer; then he loosened his cravat and gave it to the headsman. He was like a vision. Never had he looked more beautiful: his brown locks floated in the wind (at that time they did not cut the hair of those about to be executed); his fair throat reminded one of a woman's; his heroic and commanding expression gave the idea of an arch-angel. He stood upon the scaffold, lost in reverie. There, too, was a height. Gauvain stood upon it stately and calm. The sun streamed about him, crowning him, as it were, with a halo. Still, the prisoner must be bound. Rope in hand, the executioner advanced.

At that moment, when the soldiers saw their young leader so near the knife, they could no longer restrain themselves; the hearts of those warriors burst forth. Then was heard a startling sound,—the sobs of an entire army. A clamor arose: "Mercy! mercy!" Some fell on their knees, others threw down their muskets, stretching their arms towards the platform where Cimourdain stood. One grenadier, pointing to the guillotine, cried, "Here I am; will you not take me as a substitute?" All repeated frantically, "Mercy! mercy!" The very lions would have been moved or terrified; for the tears of soldiers are terrible.

The headsman paused, uncertain what to do.

Then a voice, quick and low, and yet in its ominous severity distinctly heard by all, cried from the top of the tower,—

"Execute the law!"

They recognized the inexorable tone. Cimourdain had spoken. The army shuddered.

The executioner hesitated no longer. He moved forward, holding out the cord.

"Wait," said Gauvain.

And turning towards Cimourdain, he waved his free right hand in token of farewell; then he allowed himself to be bound.

When he was tied he said to the executioner,—

"Pardon,—one moment more. Long live the Republic!" he cried.

He was laid upon the plank. The infamous collar clasped that charming and noble head. The executioner gently lifted his hair, then pressed the spring; the triangle detached itself, gliding first slowly, then rapidly: a frightful blow was heard.

At the same instant another report sounded; the stroke of the axe was answered by a pistol-shot. Cimourdain had just seized one of the pistols that he wore in his belt; and as Gauvain's head rolled into the basket, Cimourdain sent a bullet through his own heart. A stream of blood gushed from his mouth, and he fell dead.

Thus these twin souls, united in the tragic death, rose together,—the shadow of the one blending with the radiance of the other.