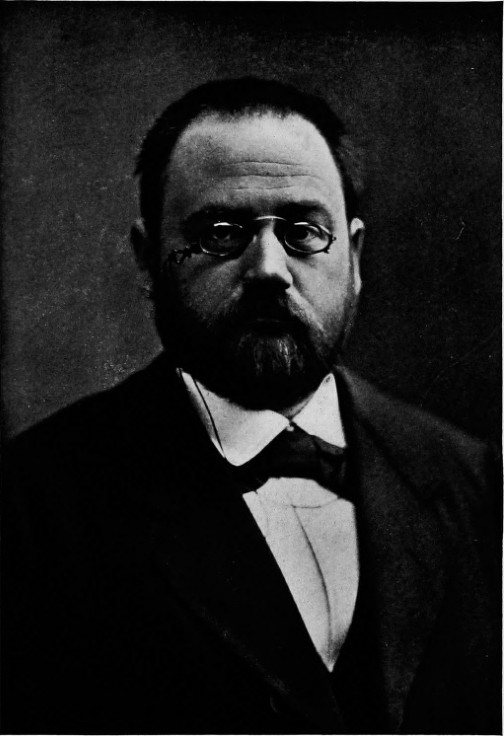

Émile Zola, 1876-1880—Photo by Nadar

[1] "Lettres de Jules de Goncourt," etc., Paris, 1885, p. 219. (Letter dated February 27, 1865.)

[2] "Lettres de Jules de Goncourt," p. 273 (February 5, 1868).

[3] "Journal des Goncourt," Paris, 1888, 1ère Série, Vol. III.

[4] "Lettres de Jules de Goncourt." See those of January 10, January 17, and April 10, 1869.

[5] "Journal des Goncourt," Vol III, p. 245 et seq.

[6] "Journal des Goncourt," Vol. IV, p. 15.

[7] "La Tribune," October, 1869.

[8] "Traité philosophique et physiologique de l'Hérédité Naturelle dans les états de santé et de maladie du Système Nerveux," Paris, 1847-1850, 2 vols. 8vo.

[9] This tree was subsequently inserted at the beginning of "Une Page d'Amour," 1878 et seq. The leaves bear the names of twenty-six characters. But the series expanded, and with its last volume, "Le Docteur Pascal," 1893, a new genealogical tree was issued giving six more names.

[10] That was then the usual price of a French novel. The rise to 3 francs 50 centimes took place after the War of 1870.

[11] £240, about $1,200.

[12] See ante, p. 30.

[13] Notably with regard to the publication of that extraordinary romance, "L'Homme qui Rit," for which Lacroix paid much more than its value.

[14] The Parnassians, who were brought together by Xavier de Ricard, dated from about 1860. The first series of "Le Parnasse contemporain" was issued by Lemerre in 1866.

[15] "The Adventures of my Life," by Henri Rochefort, English edition, London, 1896, Vol. I, p. 206.

[16] His brother, Charles Vacquerie, after marrying the poet's daughter, Léopoldine Hugo, had been drowned with her off Villequier, in 1843.

[17] This was perhaps due to the circumstance that Glais-Bizoin, the enfant terrible of the Republican opposition in the Corps Législatif, played the chief part in the directorship of the paper, the latter's better features being imparted to it by his co-editor, the scholarly Eugène Pelletan. It was run chiefly in view of the 1869 elections and Zola subsequently remarked that excepting himself and the office boy every member of its staff was a parliamentary candidate.

[18] "Journal des Goncourt," Vol V, p. 150 (November 13, 1874).

[19] "Papiers et Correspondance de la Famille Impériale," Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, 1870.

[20] See ante, p. 100.

[21] "L'Œuvre," p. 208.

[22] "L'Œuvre," p. 251. Alexis, p. 91.

[23] "Le Gaulois," March 26, 1869.

[24] The "Blowitz Memoirs" (London, 1903) give an erroneous version of this story, transferring the scene to the Quai d'Orsay, in Paris, and making Cavalié secretary to Paschal Grousset, "Delegate for Foreign Affairs" of the Commune of 1871. As Lord Lyons was not then in Paris, that version is obviously wrong. The incident, which the ambassador himself narrated more than once in after years, really occurred at Tours late in 1870, Cavalie's words being: "Dites donc, mon vieux, il ne faut pas se faire de bile, au sujet du patron. Allons plutôt prendre in bon bock!" Cavalié was a notorious bohemian, worthy of Murger; he had been one of the leaders of the cabal against the Goncourts' play, "Henriette Maréchal."

[25] Alexis, l. c., p. 173.

[26] This was a crisis provoked by Thiers' Presidential Message of November 13, 1872, by which he asked for the definite constitution of a Republic, a proposal which led to a great outcry on the part of those who wished to place the Count de Chambord or the Count de Paris on the throne.

[27] See "Souvenirs; XIV," in the "Nouveaux Contes à Ninon."

[28] "La Fortune des Rougon," Librairie Internationale. 1st and 2d editions: 1871, 389 pages, 18mo, 3 francs; 3d edition, Charpentier, 1872, 385 pages, 18mo, 3 francs 50 centimes. Thirty-eighth thousand on sale in 1903.

[29] "La Curée," Librairie Internationale; 1st edition: covers dated 1872, title-pages, 1871, 360 pages, 18mo, 3 francs; 2d edition, Charpentier, 1872, 354 pages, 18mo, 3 francs 50 centimes; 5th edition, 360 pages, 1876; fiftieth thousand on sale in 1903.

[30] M. Adolphe Brisson in "Le Temps," October 3, 1902.

[31] All that the author retained was the dramatic rights.

[32] About $1,200.

[33] The books sold at 3 francs 50 centimes each; so the above would represent a royalty of about 11 per cent.

Flaubert and his intimates: Zola, Goncourt, Tourgeneff, Daudet, and Maupassant—"Thérèse Raquin" as a play—"Le Ventre de Paris" and the sensitive critics—A first charge of plagiarism—The "Dinners of the Hissed Authors"—Zola and good fare—Sunday gatherings at Flaubert's—"La Conquête de Plassans"—"Les Héritiers Rabourdin"—Zola in the Rue St. Georges—His contributions to a Russian review—"La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret"—"Nouveaux Contes à Ninon"—"Son Excellence Eugène Rougon"—The truth about "back-stairs gossip"—Flaubert's mimicry of Napoleon III—Zola, Daudet, and "personalities" in fiction—Zola "sees mice and birds"—His stay at St Aubin-sur-Mer—He plans "L'Assommoir"—Publication of "Son Excellence"—Dramatic criticism for "Le Bien Public"—Zola's income early in 1876—Serial issue of "L'Assommoir"—The outcry and the cessation of publication—Catulle Mendès to the rescue—"L'Assommoir" as a book—Its large sales—A furious controversy—Articles, pamphlets, poems, parodies, and lectures—The years of "L'Assommoir" a date in French Literature—Other writings of the time—Zola's "band," Alexis, Huysmans, Maupassant, Céard, and Hennique—Flaubert, "L'Assommoir" and "Naturalism"—Zola's hammer, journalism—Self-assertion and pushfulness the weapons of the age.

After the Franco-German War, Gustave Flaubert, who during fifteen years of the imperial régime had resided, when in Paris, on the Boulevard du Temple, found a pied-à-terre in the Rue Murillo, near the Parc Monceau, thereby becoming one of Zola's neighbours, for the Rue Murillo is only a few minutes' walk from the Rue de La Condamine. Zola frequently called on Flaubert, whom he at first found very downcast, for the fall of the Empire seemed to him the end of the world, and besides, he had not yet recovered from the failure of his book, "L'Education sentimentale," published in 1869. It was at Flaubert's that Zola again met Edmond de Goncourt, who was still mourning his brother, and feeling so discouraged that he hardly dared to take pen in hand. With Zola and Goncourt came Flaubert's young disciple, Guy de Maupassant, at that moment little more than one-and-twenty, then Ivan Tourgeneff and Alphonse Daudet, whom Zola had already met in the days of "L'Événement," these five being for a time the only intimates of the author of "Madame Bovary." They were not a very gay party, it would seem. One Shrove Sunday, says Zola, while the carnival horns were resounding in the streets, he sat till nightfall listening to Goncourt and Flaubert, who for hours did not cease recalling the past and lamenting its disappearance.[1] Goncourt, on his side, receiving Zola about this time (June, 1872), once more found him sickly and neurotic, complaining confusedly of rheumatism, heart and bladder trouble, and mastered by such acute nervous trembling that he had to employ both hands to carry his glass to his lips.[2]

At that date Zola was planning a novel on the Paris markets—"Le Ventre de Paris"—and dramatising his earlier book, "Thérèse Raquin," working, so he told Goncourt, some nine hours and a half every day. When his play was finished he offered it to M. Hostein, the director of a new Parisian theatre, La Renaissance, and after numerous alterations had been effected, its five acts being reduced to four, it was staged and produced on July 11, 1873, when it met with a curious reception. The more frivolous, the "society" section of the audience, could not endure such tragic sombreness, and Francisque Sarcey, who held that the stage only existed for the amusement of the public, declared that "this man Zola" made him feel "quite ill." If, however, there was some hissing at the first performance of "Thérèse Raquin," there was also some applause, and when the curtain fell the question of success or failure seemed still to be hanging in the balance. But the professional critics agreed to slate the play, and moreover the "dog-days" were just beginning, the heat emptying even those theatres which had hitherto drawn large audiences, in such wise that after nine performances La Renaissance closed its doors for the summer vacation, and "Thérèse Raquin," as a play, was heard of no more.

Zola consoled himself with the comparative success of his novel, "Le Ventre de Paris,"[3] which reached a second edition deservedly, for its kaleidoscopic pictures of the Paris markets were the best descriptive work that the author had as yet penned. Nevertheless, the book encountered some severe criticism at the hands of the few reviewers who condescended to notice it. Writers devoid of any Rabelaisian sense denounced it as the apotheosis of gluttony; the transference of a pork-butcher's shop to literature was regarded as outrageous; and a certain "symphony of cheeses" gave one critic such a fit of nausea, that an unsuspecting foreigner reading his remarks might have imagined cheese to be an abomination to the delicately constituted Parisians, whereas, in fact, they then consumed—and still consume to-day—a greater amount and a greater variety of cheese, often with the strangest flavours and odours, than any other community in the world.

But, apropos of this same "symphony," a Parnassian poet,—one who was then regarded as a neo-Grecian, neither more nor less,—M. Anatole France, pointed out rightly enough that the imagery in which Zola indulged was inconsistent with his claim already put forward, though not definitely enunciated, to be a realistic writer. "Such vain, empty, and detestable virtuosité" had no place, said M. France, in the realist system, and indeed, taking that system as it was defined by Zola under the name of naturalism a little later, M. France was assuredly correct. As a matter of fact the duality of Zola's nature was always appearing. He was for ever straying beyond the limits of the doctrines he propounded, having quaffed too deeply of Hugo's rhetoric in his youth to be able to restrain himself. And it was as well, perhaps, to show that even at this early stage of his great series, his vagaries, his deviations from his self-chosen principles, already attracted attention.

It was also apropos of this same "Ventre de Paris," that the first of many charges of plagiarism was preferred against Zola. In this instance it was M. Nadar, photographer, aeronaut, caricaturist, and author, who declared that "the colour scale" of the sea of vegetables which Zola showed spreading around the Paris markets had been borrowed from something which he, Nadar, had written. But Zola had merely expanded a passage of one of his own early articles; and the suggestion of plagiarism was the more ridiculous as the first thing which strikes anybody, even with only a little artistic perception, when witnessing daybreak at the Paris markets, is the diversity of the picture's hues, the great medley of colour gradually accentuated by the light of the rising sun. M. Nadar probably realised that his contention could not be regarded seriously. At all events the matter dropped, and Zola turned to his next volume, "La Conquête de Plassans," as well as to a new play, a three-act comedy, which he entitled "Les Héritiers Rabourdin."

Meantime, it had occurred to Flaubert to unite his intimates in a monthly dinner, which, said he, might be called "the Dinner of the Hissed Authors." He himself had been hissed for his play, "Le Candidat," Zola had encountered a similar experience with "Thérèse Raquin," Alphonse Daudet with "L'Arlésienne," and Edmond de Goncourt with "Henriette Maréchal." Tourgeneff, also, was admitted to the company on the strength of his assertion that he had been hissed in Russia; but, according to Daudet, when Émile de Girardin, hearing of the project, wished to join the others—pleading, no doubt, the reception given to the notorious "Supplice d'une Femme"—they promptly blackballed him on the ground that he was not a littérateur.[4]

Thanks to the wine provided at those monthly dinners, they were livelier, though perhaps not more interesting, than the Sunday meetings in Flaubert's rooms. They took place at various restaurants, the first at the Café Riche, on April 14, 1874.[5] Then, as Flaubert was starting for Le Croisset, near Rouen, the next was adjourned till the winter months. As Zola tells us, during the years over which these dinners were spread, the choice of a restaurant for the next repast invariably led to great discussion among the five convives. Anxious apparently to sample every kind of cuisine, they went from the Café Riche to Voisin's in the Rue St. Honoré; from Voisin's to Adolphe and Pelé's near the Grand Opera House, and thence to the Byron on the Place de l'Opéra Comique. They feasted now on bouillabaisse, now on poulet au kari. Tourgeneff naturally required caviar to whet his appetite; Flaubert always insisted on having Normandy butter, and revelled in Rouen ducklings à l'étouffade; while Goncourt evinced a depraved taste for preserved ginger. As for Zola, he, according to Alphonse Daudet, was addicted to shellfish and sea-urchins! His friends occasionally twitted him respecting the partiality he began to evince for good fare,—which cast, they said, a lurid light on his novel, "Le Ventre de Paris"—and he frankly acknowledged his gourmandise, pleading, however, that it was his only vice, and that he had gone hungry so many years!

Of course there was no ceremony at those monthly dinners. Flaubert and Zola often took off their coats and sat down at table "in their shirt-sleeves," as the phrase goes, while between the courses Tourgeneff would sprawl on a sofa. And directly the coffee was served the waiters were turned out of the room, and a long discussion on literary subjects began, that is when it had not been started already at the outset of the repast. "I remember," wrote Zola, in his recollections of Flaubert,[6] "a terrible discussion on Chateaubriand, which lasted from seven in the evening till one o'clock in the morning. Flaubert and Daudet defended him, Tourgeneff and I attacked him, while Goncourt remained neutral. At other times we took up the subject of the passions, talked of women and love, and on those occasions the waiters looked at us aghast. Then, as Flaubert detested having to walk home alone, I accompanied him through the dark streets, and did not get to bed till three o'clock in the morning, for we halted at the corner of every open space to philosophise."

Meantime the Sunday gatherings at Flaubert's had become far less gloomy. The author of "Madame Bovary" had gradually accustomed himself to the new order of things, and when he removed from the Rue Murillo to the Faubourg St. Honoré, a number of admirers surrounded him, as well as his half-dozen chosen intimates.[7] On some occasions as many as twenty visitors assembled in his half-furnished white and gold drawing-room, which from three till six o'clock became full of tobacco-smoke, everybody except Zola freely indulging in pipe, cigar, or cigarette. He had ceased smoking under compulsion, in his days of dire necessity, and though no such compulsion existed now, even Flaubert seldom succeeded in forcing a pipe upon him.

In his account of those Sunday gatherings, he allows us to understand that the speech often suggested the style of Rabelais, perhaps even of Villon, that spades were called plumply spades, which will not surprise those who know the Cambronnesque epithet that Flaubert—the stylist—applied to his own work, "Madame Bovary," in his anger and weariness at being incessantly complimented on it. For the rest, Zola tells us that the company "rattled through every subject, always reverting to literature, to the book or the play of the hour, or to some general question or venturesome theory; but, at the same time, excursions were made into every field, and neither men nor things were spared. Flaubert thundered, Tourgeneff told stories of exquisite originality and savour, Goncourt pronounced judgment on one matter and another with all his shrewdness and personal style of phraseology. Then Daudet acted his anecdotes in that charming manner of his, which made him the best of companions; while as for myself I did not shine at all, for I am a very poor conversationalist, and only worth anything when I feel a deep conviction on some subject, and fly into a passion."

To some of the aforementioned gatherings and dinners it will be necessary to refer again in the course of this narrative. What has been set down here will, however, indicate the nature of the companionship which came to Zola as he toiled along the path leading to success. He had not shaken off his old friends, he still gave his weekly dinners which one or another—Alexis, Marius Roux, Coste, Duranty, and Béliard, the painter,—attended, though some began to fall out of the ranks, carried hither and thither by their private interests. Meantime, he worked very zealously. In 1874, he completed his story, "La Conquête de Plassans,"—the fourth volume of the Rougon-Macquart series—and ran it through "Le Siècle" as a serial. When it was published, soon afterwards, in volume form by Charpentier, there was a sufficient demand to justify the printing of a second edition of this tale of priestly intrigue in public and private life.[8]

But Zola's eyes were still turned towards the stage, partly because he desired to apply certain theories to play-writing, and partly because he knew that the successful dramatist advanced far more rapidly than the successful novelist along the path to fortune. Thus, having finished his three-act comedy, "Les Héritiers Rabourdin,"[9] in which the gruesome was mingled with the farcical, he offered it to the Palais Royal Theatre. But the manager of that house only cared for amusing plays free from all lugubrious taint, his chief author being Labiche, whose name was synonymous with unadulterated merriment; so Zola soon carried his manuscript to M. Montigny of the Gymnase. Writing on July 23, 1874, to his friend and publisher, M. Charpentier, he gave the following account of the issue of his endeavours:——

"My negotiations with Montigny have fallen through. He handed me back my manuscript in the most charming manner, vowing that he had a keen desire to stage a play of mine. He even gave me my entrées to the Gymnase, by way of consolation, no doubt. Briefly, my play frightened him, but it is certain that he long hesitated about it, and that the doors of his theatre will be open to me if I only undertake 'to be good.' As soon as my manuscript was returned to me I was eager to carry it elsewhere. Decidedly, it is a disease; one wants to be 'played,' whatever may be the chances. The only thing left for me to do was to knock at the door of the Théâtre de Cluny. I went there. And, yesterday, Weinschenk [the manager] accepted my play. It will pass before Flaubert's,[10] about the middle of September, heaven knows under what conditions, for the company frightens me terribly. But what would you have had me do? I had no alternative, I had to go to that galley to ensure myself some little peace of mind. It would have rendered me so unhappy to have left the manuscript lying in a drawer."

The Théâtre de Cluny was then a third or fourth rate little house in the Quartier Latin, and Zola's fears respecting its company were fully justified. To give an idea of the fate which befell his play it will be enough to mention that one of the "parts," that of Chapuzot, an octogenarian, was confided to a young fellow named Olona, who in his efforts to imitate an old man's voice ended by speaking like a "Punch." Nevertheless, there was no hissing at the first performance which was delayed until the 3d of November (1874); the demeanour of the audience being rather one of bewilderment, particularly when in the third act illness and death suddenly intruded into the midst of farce. But the critics did not hesitate. They damned the play even as they had damned "Thérèse Raquin," "Le Figaro" curtly declaring that it was repulsive, tiresome, and immoral; and after seventeen performances, given to well-nigh empty houses, except on Sundays when the shopkeepers and working-people of the district attended and laughed good-naturedly,[11] "Les Héritiers Rabourdin" disappeared from the stage without hope of revival.

But this was not Zola's only work during the year 1874. He had now moved from the Rue de La Condamine to 21, Rue St. Georges (now Rue des Apennins) at Batignolles. Here again, unlike most Parisians, who live in flats, he had a house to himself, with a garden, both considerably larger than the previous ones. In the Rue de La Condamine he himself had attended to his garden, made a kennel for his dog, erected his own fowl and rabbit houses—for he was skilful with his hands—just like any other modestly circumstanced dweller in Suburbia. But in the Rue St. Georges his prosperity increased, and instead of employing a mere femme-de-ménage to help his wife in the housework, he was soon able to engage two servants, man and wife.

His increased prosperity was due to the good offices of his friend, Ivan Tourgeneff, who took no little interest in him. At this time Zola no longer wrote political articles for the Paris press, for editors deemed his pen too violent; and as he also carried revolutionary methods into literary discussion, he was unable to find in France any satisfactory outlet either for certain critical studies on eminent writers which he had often thought of undertaking, or for any adequate expression of his theories respecting fiction. In these circumstances Tourgeneff recommended him to a St. Petersburg review, the "Viestnik Yevropi," otherwise "The European Messenger." To this periodical Zola became a regular and well-paid contributor for several years. The essays and short stories which he wrote for it were naturally translated into Russian, in which language they became known long before the French text was printed.

It was also this Russian review that first issued "La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret," the fifth instalment of the "Rougon-Macquarts" and one of the most romantic of all Zola's novels. He wrote it in the Rue St. Georges in the summer of 1874, after arranging for the publication in book form of ten short stories which he had contributed during recent years to newspapers, almanacs, and other periodicals. The little volume was called "Nouveaux Contes à Ninon," and the reception given to it by both the critics and the public was distinctly encouraging.[12] The former, however, cold-shouldered "La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret," which was published by Charpentier in 1875, though this was the first of Zola's novels that reached, not a great sale certainly, but one which may fairly be called considerable for that period. In 1876 a sixth edition of it was reached, followed by another in the ensuing year.[13]

When "Abbé Mouret" was placed on the market, Zola, who seldom if ever rested, was already working on his next book, "Son Excellence Eugène Rougon," in which he dealt with the political side of the Second Empire and sketched the life of the Imperial Court at Compiègne. Some years previously, in 1865, when he was writing for "L'Événement," that journal had published a series of articles signed "D," chronicling the imperial sojourn at Compiègne; and these had been collected in a volume to which the fanciful subtitle of "Confidences d'un Valet de Chambre"[14] was given, though, in point of fact, the author was simply a journalist, recommended by Théophile Gautier for the express purpose of reporting the doings of the court during its villegiatura, and in that way refuting the thousand rumours of indescribable orgies at Compiègne, which circulated among the more credulous Parisians. From the record in question, a very accurate one, Zola, who, of course had never been a guest at Compiègne, derived considerable information, but sundry critics, unacquainted with the truth, twitted him for having placed reliance on back-stairs gossip, when in reality he had taken as his guide statements issued with the Emperor's express approval.

But further information was given him by Flaubert, who had visited Compiègne more than once as a court guest. And Goncourt tells us that Flaubert, when questioned by Zola, proceeded to mimic the late sovereign in characteristic fashion, walking up and down with his figure bent, resting one hand on his back, and twirling his moustache with the other, while mumbling idiotic remarks. "Napoleon III," added Flaubert, by way of comment, "was unadulterated stupidity"; to which proposition Goncourt retorted, wittily and with great truth, that stupidity was usually loquacious, whereas the Emperor's had been silent stupidity. "It was that which made his strength, it allowed one to suppose everything."[15] No better judgment than this was ever passed on Napoleon III. For twenty years the world regarded him as "deep," though, in reality, he was in many respects a fool, one who would never even have reigned over France had it not been for the energy and acumen of his bastard half-brother, the Duke de Morny.

Apropos of the latter, Goncourt mentions that one day when Alphonse Daudet, who had been in the Duke's employment, was giving various particulars about him, Zola expressed a keen regret that he had not possessed this information in time to use it in "Son Excellence," which contains but a very imperfect sketch of Morny under the name of Marsy. In a discussion which ensued, Zola evinced great eagerness to put everything into his books—that is everything he learnt which might be germane to his subjects and likely to cast light upon them. On the whole, however, he was far less "personal" than Daudet. Both in "Son Excellence Eugène Rougon" and in his later novel, "Paris," although many of the characters suggested well-known people, almost every one of them was a blend, so to say, of three or four originals, whereas Daudet, sketching his characters from the life, often modified them so little that those who knew their Paris could not regard some of his books otherwise than as pillories.

The writing of "Son Excellence Eugène Rougon" proved a somewhat laborious task for Zola, the period selected for the story being largely antecedent to his participation in newspaper life, from which he had learnt so much both politically and socially. And his desire to be scrupulously accurate in all essential particulars led him to undertake a variety of fatiguing researches. Hard work, indeed excessive work, for he wrote regularly for the Russian review, and penned some Parisian correspondence every day for "Le Sémaphore" of Marseilles, besides proceeding with his novel, again reduced him to a nervous condition, and one day, when he was with Goncourt and others, he complained that while he wrote he often fancied he could see mice scampering about him, or birds flying away on one hand or the other. That spring (1875) others also felt "run down," as the saying goes. Tourgeneff, for instance, complained of his nerves, and Flaubert was haunted by the idea that there was always somebody behind him while he worked.[16]

At last, when the summer came and his book was finished, Zola resolved to seek a change, though not absolute rest, for idleness was repugnant to him. His circumstances had now greatly improved; M. Charpentier had torn up the original agreement for the Rougon-Macquart series, and opened his cash-box, and Zola had at last liquidated the liabilities which he had incurred by the failure of Lacroix. So, with his wife and mother, he betook himself to a little Norman watering-place, St. Aubin-sur-Mer, lying between the mouth of the Orne and the Calvados rocks, and reached, in those days, by coach from Caen.

It was there, as Alexis relates, that he planned his next book, "L'Assommoir," the idea of which had occurred to him before his departure from Paris. In his previous volumes he had dealt with the Imperial Court, the Parisian society, the political world, the provincial life, the clerical intrigues of the Second Empire, and it was only in "Le Ventre de Paris" that he had cast some side-lights upon the working class of the capital. They, however, deserved an entire volume to themselves, and Zola felt that he could write one, based largely on his own personal knowledge of their habits and customs, for in his days of poverty he had dwelt among them at Montrouge, and in the Rue St. Jacques, and again on the Boulevard Montparnasse. Besides what he had written about them in a few newspaper articles or short stories, such as "Le Chomage," "Mon voisin Jacques" and "Le Forgeron,"[17] which will be found in the "Nouveaux Contes à Ninon," he remembered a great many things, funerals, festivities, and junketings. He had discovered, too, a suitable title—"L'Assommoir"—in Alfred Delvau's slang dictionary, and it was this circumstance which, when he had written two chapters of the book in his usual style, suddenly inspired him with the idea of penning it in the real vernacular of the Parisian masses, not the special slang of thieves and prostitutes, such as Eugène Sue had employed, and, in part, invented, in "Les Mystères de Paris," but in the current langage populaire, understood by everybody.[18]

It was during Zola's stay at St. Aubin, face to face with the sea,—whose influence was not lost upon him for, as will be shown, it suggested in part a later work, "La Joie de Vivre,"—that he mapped out this book on the Parisian prolétaire, which was to raise him to fame, and Alexis tells us that though he already had the chief scenes of the story in his mind he was for a time at a loss for a suitable intrigue which would weld them well together. The idea of taking a girl of the people, who stumbles and has two children by her seducer, then marries another man, establishes herself in business by dint of hard work, but is borne down by the conduct of her husband, who becomes a drunkard, had previously occurred to him, figuring, indeed, in the original genealogical tree which he had drawn up for his series, but he felt that the husband's drunkenness might not fully account for the wife's downfall, and he remained at a loss how to proceed until, all at once, he was inspired to bring the woman's seducer back into her home. That would make everything possible, and he decided to model his story accordingly.

He busied himself with "L'Assommoir" on his return to Paris in the autumn, and arranged for the "serialisation" of his completed novel, "Son Excellence Eugène Rougon," in "Le Siècle" early in the following year, 1876.[19] He was then in high spirits. "Fortune," he said to Edmond de Goncourt, "was at last finding its way to his home." Indeed, a stroke of luck had befallen him. A daily evening paper, "Le Bien Public," had appointed him its dramatic critic at a salary of six thousand francs a year. This journal had been started with the support of Thiers, since whose resignation of the presidency of the Republic in 1873 France had been governed in a reactionary spirit by MacMahon's ministers. During that troublous period "Le Bien Public," whose connection with Thiers was well known, rendered good service to the Republican cause, first rallying many hesitating people, then becoming more and more democratic, and helping on that alliance of the middle class and the proletariat which saved France from monarchical intrigues and resulted in MacMahon's downfall. Zola was delighted to join the paper, particularly as it allowed him all freedom in his dramatic criticisms, which were written in his usual trenchant style. Of course he had to give to them some of the time he had hitherto allotted to his books, but he was not afraid of additional work, particularly when it was of a nature to bring him nearer to the Parisian stage, on which, in spite of every rebuff, he still dreamt of triumphing. Moreover, the increase in his income was very welcome; with the salaries he deceived from "Le Bien Public" and "Le Sémaphore"—for which he still wrote—the proceeds of his contributions to the Russian review, which some months amounted to eight hundred francs, and the money accruing from his books, his income, in the early part of 1876, before the serial publication of "L'Assommoir," represented quite twenty-five thousand francs, and perhaps thirty thousand francs a year.[20] But he decided to offer his new story to "Le Bien Public"; and that he could now command good terms is shown by the fact that the paper agreed to pay him ten thousand francs for the serial rights without even seeing his manuscript, which, by the way, was not ready, though he had given information respecting the subject he meant to treat.

The serial issue began in June (1876) and there was an immediate outcry. Whatever might be thought of Zola's novels in book form, they were not liked by the newspaper readers of those days; and, in the case of "L'Assommoir," there were not only complaints of immorality, but the author was accused, ludicrously enough, of slandering the masses, insulting the working classes. The latter charge alarmed the director of "Le Bien Public" far more than the first did. Important political issues were then at stake, and it was essential that the working-man should not be offended! Of course people judged the story merely by the instalments as they appeared, and these as yet gave little indication of what it would be when completed. Thus a very narrow view was taken by some readers, while others were more particularly horrified by the slang in which the work abounded, complaining notably of its appearance, not only in the dialogue but in the descriptive and narrative passages, into which Zola had introduced it with the express object of suggesting that this was a story of the masses told by one of themselves. Briefly, in all respects, the outcry became so great that in July the director of "Le Bien Public" decided to cease publication. Nevertheless, the paper honestly paid Zola the full amount specified in the agreement

At this moment M. Catulle Mendès again came to the rescue, and, for a nominal sum, a thousand francs or so, Zola handed him the remainder of his manuscript for publication in "La République des Lettres"; then, leaving his literary bombshell to complete its work, betook himself to Piriac, on the Breton coast, between Vannes and St. Nazaire, for a holiday. In Paris the periodical edited by M. Mendès suddenly leaped into notoriety. It supplied the latter part of "L'Assommoir" gratuitously to those subscribers of "Le Bien Public" who desired to read it, but at the same time its sales increased largely, for so much was said about this extraordinary story, so violent were the attacks upon it, that many, who as yet had seen nothing of it, wished to ascertain its character and form their own opinions.

Amid all the hubbub, a well-known Parisian journalist of that period, Tony Révillon, who had catered for the working classes since the latter years of the Empire, meeting Paul Alexis one day in the autumn, said to him: "Tell Zola to make his mind easy. His book will sell like hot cakes.... 'L'Assommoir' will be a wonderful success."

In a pecuniary sense, such was indeed the case directly M. Charpentier published the book in 1877.[21] Of the ordinary edition fifty thousand copies—a very large figure for those days—were soon sold, and at the end of 1879, eighty thousand had been disposed of; these being independent of a "popular" illustrated edition, issued in fifty-nine "parts" at ten centimes apiece, forty thousand copies of which were disseminated chiefly among the Parisian working classes (whom the story was said to libel) in the course of 1878 alone. From 1877 onward an unexampled controversy raged round the book as well as round Zola's principles and methods generally—a controversy to which additional zest was imparted both by a dramatic adaptation of the story, which drew all Paris to the Théâtre de l'Ambigu, and by the publication in French of some of the articles on French literature and literary men which Zola had written for the Russian review. More fuel was added to the fire by a pamphlet he penned and called "La République française et la Littérature," and by a series of papers he contributed to "Le Voltaire" and collected a little later under the title of "Le Roman Expérimental." Wherever one went in Paris one heard allusion to or discussion of Zola, "L'Assommoir," and "naturalism." The newspapers were full of articles: the author was attacked by such men as Henri Fouquier in "Le XIXe Siècle," Francisque Sarcey in "Le Temps," Jules Claretie in "La Presse," Gaucher in "La Revue Bleue." "La Revue de France" joined in the hostile chorus and so, too, did the Olympian "Revue des Deux Mondes"; while "La Vie littéraire" and "La Jeune France" joined "La République des Lettres" in defending the much-abused author.

But pamphlets also rained upon Paris, there was "Zola, Pape et César," by Madame Arnault; "Monsieur Zola," by "Papa Cadet"; a "Petit Traité de Littérature Naturaliste," by "Camille B." and Albert Vanier; "Naturalisme ou Réalisme," by F. de Bus; "M. Zola et son Assommoir," by Frédéric Erbs; "Apropos de l'Assommoir," by Édouard Rod, and several others. But mere pamphlets did not suffice, there came "poems" like "En r'venant d' l'Assommoir," by Galipaux; parodies like "L'Assommoir du Cirque Franconi" and "L'Assommoir pour rire," by Blondelet and Beaumaine; and finally there were lectures both against Zola and in defence of him, the most notable of the latter, one which particularly angered both the conservative critics and the sensitive Parnassians, being delivered by M. Léon Hennique in the Salle des Conférences on the Boulevard des Capucines.

To a few of the matters enumerated above, the production of "L'Assommoir" as a play, and the publication in volume form of some of Zola's literary papers, it will be necessary to refer again in following the thread of this narrative; but they have been mentioned here in order that the reader may at once form some idea of the sensation which the appearance of "L'Assommoir" caused, first in the literary world of Paris, whence it spread throughout the reading public. In the literary annals of France, 1876, 1877, and 1878 must always rank as the years of "L'Assommoir." Yet they were by no means barren in other respects. They cover the period when Victor Hugo published, not only a new series of "La Légende des Siècles," but also "L'Art d'être Grandpère" and "L'Histoire d'un Crime." And other poets were raising their voices: Leconte de Lisle was issuing his translation of Sophocles, Mallarmé his "Après-midi d'un Faune," Dierx his "Amants," Anatole France his "Noces Corinthiennes," Richepin his "Chanson des Gueux." And fiction, as usual, poured from the printing presses of France. Flaubert's "Trois Contes"; Daudet's "Jack" and "Le Nabab"; Goncourt's "La Fille Élisa"; Octave Feuillet's "Amours de Philippe"; George Sand's last stories, "La Tour de Percemont" and "Marianne"; Ferdinand Fabre's best book, "L'Abbé Tigrane," were then first offered to the reading public. And going further afield one finds "Le Train 17" and "La Maison Vide," by Jules Claretie; "Les Batailles du Mariage" and "Sans Famille," by Hector Malot; "Samuel Brohl," by Cherbuliez; "Raymonde," by André Theuriet; "Michel Strogoff," by Jules Verne; "L'Homme de la Croix-aux-Bœufs," by Léon Cladel, also appearing at this time. But none of these, and indeed, briefly, no novel, or play, or poem, or historical or philosophical work of the time stands forth conspicuously, preëminently, as "L'Assommoir" does, to give its name to the date, to mark the period, to indicate a climax or an evolution in French literature.

Before "L'Assommoir," the critics had often treated Zola's books and theories with silent contempt, but they could do so no longer. They were at last compelled to recognise that a new force had arisen, and that they must be up and doing if they wished to prevent it from gaining the mastery. As happens at every literary evolution, as was the case when the Romantic supplanted the Classic school, all the older men, and, indeed, nearly all of any age who had acquired a recognised position, were against Zola, his adherents being mostly young writers whose positions were not yet made. It has been mentioned that some of the friends of his youth and early manhood had dropped away from him, in a measure by the force of circumstances. But "Le Ventre de Paris" and "L'Assommoir" brought him others, and in particular there were five young men of great promise who, for a time, became known as his "band." Taking them by order of seniority, one may place first the ever-faithful Paul Alexis, a Provençal, in 1877 thirty years of age. Second came Joris Karl Huysmans, a Parisian of Dutch origin, nine and twenty years old, and already the author of a volume of prose poems suggestive of Baudelaire, and a novel, "Marthe." Next there was Guy de Maupassant, a Norman, seven and twenty, introduced to Zola by their mutual friend and master, Flaubert; then Henri Céard, a thoroughbred Parisian, six and twenty, who without introduction had called upon Zola one Sunday to tell him that he had read his books and admired them; and, finally, Léon Hennique, a native of Guadeloupe, who numbered but five and twenty years against the seven and thirty which Zola completed at the time when his first great book was published.[22]

Every Thursday, for some years, those five young men, two of whom, Maupassant and Huysmans, afterwards rose to eminence, visited Zola and talked "literature" with him, even as on Sundays he and they visited Gustave Flaubert. The latter, amid all the hubbub and controversy provoked by "L'Assommoir," felt that Zola was going too far, at least farther than he, Flaubert, would have gone. He always underrated his own realism—or naturalism, if one prefer that term—as displayed in "Madame Bovary," as well as his own philosophy, outlined in "L'Education sentimentale" and "La Tentation de St. Antoine"; and if Zola's account of him be accurate, his one ambition was to be known and remembered as a stylist, a master of impeccable French. He even denied that "Madame Bovary" marked any evolution in fiction, he shut his eyes to the deductions which others drew from it, and thus, when he found himself confronted by Zola's venturesome theories, he was at first at a loss to account for them. In one sense his astonishment was amusing: it suggested the surprise of the cause at the sight of so remarkable an effect. But if he twitted Zola about his naturalist professions of faith he did so, as Goncourt observes, "avec de très grands coups de chapeau" for he fully recognised the ability of the man who claimed to be his disciple. One thing which he did not like was the eagerness with which Zola accepted controversy and proclaimed his doctrines on all possible occasions, for this seemed to be too suggestive of self-advertisement.

Zola, however, replied very naturally, frankly, and boldly, that he, Flaubert, possessed a small fortune and was therefore able to disregard all sorts of considerations, whereas he, Zola, had been obliged to earn his living by his pen and undertake at times all kinds of writing, even contemptible work. "What I write," he added, "may be divided into two parts. There are my books by which I am judged, and by which I desire to be judged, and there are my critical notices in 'Le Bien Public,' my Russian articles, and my correspondence for Marseilles which I regard as of no account, which I reject, and which I only undertake in order to help on my books. I first placed a nail in position and with the stroke of a hammer I drove it half an inch into the brain of the public, then with a second blow I drove it in an inch. Well, my hammer is the newspaper work which I myself do round my own books."[23]

Nothing could have been more frank than this, not even his remark on the same occasion—in reply evidently to some criticism of Flaubert's, which Goncourt does not exactly specify,—that he cared not a rap for the word "naturalism," and yet intended to repeat it, because things required christening in order that the public might regard them as new.[24] In all this one traces the determination to succeed at any cost, the fighting spirit which had prompted Zola to write to Antony Valabrègue, more than ten years previously, that he belonged to an impatient age, that if he did not trample others under foot they would pass over him, and that he did not desire to be crushed by fools. Thus, whatever might be his contempt for the weapons of his time—advertisement and pushfulness—he readily made use of them, feeling that if he neglected to do so, amid all the stress, all the fierce competition around him, he might well go under and fail to reach the goal, in spite of the talent of which he was conscious. The battle of the age was the keenest there had ever been, a man could only triumph by incessantly thrusting himself forward, and Zola, for his part, did so without hesitation.