Introduction

On a crisp spring day in March 1772, a woman led a group of seven Comanches into the town of San Antonio de Béxar, Texas, carrying a white flag and a cross. Her approach was the initial step in a peace process between Comanche and Spanish peoples in a time of violent interaction. Since they had first come into contact thirty years before, Spaniards and Comanches in Texas had never known peace, much less friendly negotiation, with one another. Rather, hostility had ruled their relations. By 1772, the groups viewed each other with such deep suspicion that thirteen more years would pass before they completed a treaty agreement. Significantly, every time hostilities flared anew during those thirteen years, women stepped (or were pushed) forward as the chosen emissaries of truce.

It may perhaps seem strange that Comanches would send a woman at the head of this delegation. It certainly was not customary among Comanches to assign women to positions of diplomatic authority, any more than it was the custom of Spaniards to receive women in such capacities. Indeed, this woman did not travel as an authority in her own right. She was a former captive of Spaniards whom they had sent home thirty days before to win diplomatic favor with Comanche leaders. Comanche chiefs had promptly sent her back to the Spanish villa in order to retrieve other Comanches held captive by Spanish officials. Why, then, did Spanish and Comanche men choose this woman and so many others as political mediators in the eighteenth century? Because after decades of violence, it had become virtually impossible for an all-male party from either group to approach the other without being presumed hostile; the presence of women was the only way to signal peaceful intentions. This role was not a new one for women in the region, but rather one that had evolved over the eighteenth century as powerful and populous Indian nations negotiated economic and political relations with small numbers of European settlers and traders in the midst of mounting violence and enmity.

Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands investigates the history behind moments such as this one in 1772. To do so, it explores the stories of a range of Indian peoples—including Caddos, Apaches, Payayas, Ervipiames, Wichitas, and Comanches—and the varied relationships that they each formed with Spaniards at different moments in time from the 1690s, when Spaniards first attempted to settle in the region, through the 1780s, when Comanches decided a Spanish peace might be desirable—the last major native power in Texas to do so. More specifically, the book seeks to illuminate what lay beneath the surface of political ritual in order to show how those moments when women acted as mediators of peace did not simply signal cross-cultural rapport, but rather the predominance of native codes of peace and war.

The political symbols and acts of Spanish-Indian interaction in Texas must be understood as a diplomacy of gender. Hitherto, European-Indian interactions have been viewed primarily in the context of race relations. This in turn implicitly assumes that Europeans had all the power, since race was becoming the crucial component of European categories of social and political hierarchy. This book argues that Native American constructions of social order and of political and economic relationships—defined by gendered terms of kinship—were at the crux of Spanish-Indian politics in eighteenth-century Texas. In some ways, it is an old-fashioned insight that gender is about power, but in native worlds, where kinship provided the foundation for every institution of their societies, gender and power were inseparable. Once Spaniards arrived on the scene, they discovered that they too would have to operate within those terms if their relationships with Native Americans were to succeed.

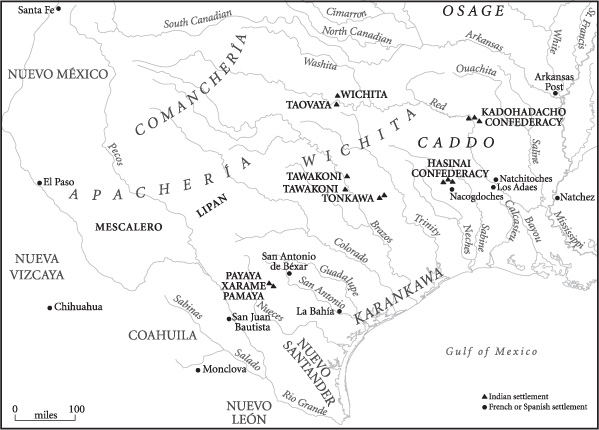

Why would Europeans have to play by native rules? Despite well-entrenched myths of Spanish conquest, claims of imperial control made by Spanish officialdom did not reflect reality on the ground in much of the region they identified as the province of Texas. Indians—and the Spaniards who lived among them—recognized most of the region as Apachería, Comanchería, Wichita, and Caddo territories. In fact one Franciscan missionary explained in a 1750 report to the king that missions in the Spanish towns of San Antonio de Béxar and La Bahía lay outside the “Province of Texas”—in other words, Texas was the province in which lived Tejas Indians (as Spaniards began calling Hasinai Caddos in the 1690s), and Spaniards certainly did not control that. The reports of military expeditions sent to reconnoiter Spanish defensive capabilities in the region in 1727 and 1767 similarly referred to the region as the “Province of the Texas Indians,” suggesting the Spaniards’ awareness that they were living in or near Caddo lands at Caddo sufferance as long as a peace alliance held. In 1727, Pedro de Rivera in turn identified the “Tejas province” as stopping at the boundary of the Apache-controlled hill country he called “Lomería de los Apaches.” Thus, as provincial governor Tomás Felipe Winthuysen described to his superiors, San Antonio stood at the core of Apachería. By 1767, Spaniards recognized that the “true dominions” of Comanches had superseded those of Apaches. Thus, presidial soldiers spent several hours a day patrolling a semicircular path twelve miles out from San Antonio de Béxar, where lay “El Paso de los Comanches” and the many other puertos (gateways) into Comanchería that surrounded the Spanish villa. Indians, not Spaniards, expanded their territorial claims over the century.1

The marqués de Rubí, head of the 1767 expedition, drew pointed distinctions between the “real” and “imaginary” boundaries of the nominal Spanish province of Texas. After almost eighty years of a Spanish presence in the region, he called for the evacuation of the few Spaniards living in Caddo, Wichita, and Comanche lands—where “imaginary missions,” empty of neophytes, huddled along “imaginary frontiers.” Only when the territory claimed by Spain, “which we call with high impropriety ‘Dominions of the King,’” was drawn back far to the south to constitute just the areas around the towns of San Antonio de Béxar and La Bahía could “those which are truly dominions of the King” (territories south of the Rio Grande) be defended against Indian invasion. Indians were the feared conquerors in Texas.2

Others agreed. In 1778, fray (friar) Juan Agustín Morfi recorded that “though we still call ourselves [the province’s] masters, we do not exercise dominion over a foot of land beyond San Antonio.” Nicolás de Lafora, a member of Rubí’s 1767 expedition, wrote that Indians “have little respect for the Spanish and we are admitted only as friends, but without any authority.” Tellingly, Lafora measured Spanish powerlessness through the story of one woman’s fate in these lands. He recorded the expedition’s galling discovery of a Spanish girl living as a “slave” of Hasinai Caddos—a girl whom neither “so-called” Spanish authority nor Spanish money could liberate, leaving Lafora to bewail how in Texas the “honorable forces of his Majesty” could be forced into “the shameful position of supplicants.”3

Yet, supplicants they were, and Lafora’s lament echoed two hundred years of Spanish experience in these lands. A much earlier chapter of Spanish subordination to Indian peoples of Texas had been written in the sixteenth century. In 1530, survivors of an expedition led by Pánfilo de Narváez had been stranded on the Texas coast after taking to the sea in flight from Indians in what would become Florida. At the end of six years living among Indian peoples of south-central Texas, only four men remained alive of the original four-hundred-man expedition. Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Andrés Dorantes, Alonso del Castillo, and an enslaved Moor named Estevanico had negotiated themselves into positions as enslaved traders and emissaries among different Indian groups. Their survival may well have rested upon their ability to play intermediary roles usually associated with women by the region’s native peoples, especially in acting as go-betweens among different groups. Though Cabeza de Vaca later, in his published narrative, put an ennobling spin on his experiences, at the time it surely represented a different but no less painful loss of male honor than that cited by Lafora.4

Indian and European settlements in the eighteenth-century Texas borderlands. Map drawn by Melissa Beaver.

In the eighteenth century, when Spaniards came again to Texas, they sought permanent settlement among native peoples from whom they still earned no recognition as representatives of the most extensive, wealthy, and powerful European empire in the Americas. The Spanish state cast little shadow in these lands. To understand the world they entered, imagine present-day Texas divided into quadrants, three under native control, with Apaches in the west, Caddos in the east, and Comanches and Wichitas in the north. The fourth, the Spanish quadrant of Texas, consisted of the south-central areas of San Antonio de Béxar and La Bahía (and a tiny pocket of soldiers, Franciscans, and civilians who lived scattered among Caddo hamlets around the presidio and missions of Los Adaes). Within these islands of Spanish settlement, mission-presidio complexes served as the primary sites of Spanish-Indian interaction, where Franciscan missionaries fought for Indian souls and soldiers fought for Spanish security—neither with much success. They had first thought to make the small settlement in the middle of Caddo territory the base for Spanish occupation. In the face of Caddo indifference and rejection by 1730, however, the area of southern, rather than eastern, Texas had emerged as the center of Spanish development. There, multiple and diverse Indian peoples, including Cantonas, Payayas, and Ervipiames began to put Spanish institutions and relationships to their own use.

Indian observers never saw Spaniards as a ruling power. Indians were the rulers in these lands. Outside of their very limited areas of settlement, in fact, Spaniards merited little native attention at all. There were no conquests and no attempts to subject Indians to tribute or labor systems as found elsewhere in Spanish America. A few missions and fewer presidios made up the Spanish landscape and aimed solely at defending the small, struggling Spanish population against superior Indian forces. The total population of Spanish Texas spread among the three areas of San Antonio, La Bahía, and Los Adaes never exceeded 3,200 people in the eighteenth century, and that number included those Indians who had chosen to enter mission settlements to live with Spaniards.5 Many Indian villages and rancherías (Spaniards’ term for native seasonal encampments) dwarfed those of Spaniards. Although the spread of epidemic disease diminished native population numbers as the century wore on, it did so unevenly, allowing some, like Comanches (who did not suffer their first smallpox outbreak until 1779), to avoid exposure for most of the century, while others implemented strategies to respond to population losses through adoption, intermarriage, and confederation with extended kin and allies.

In the eyes of Apaches, Comanches, Wichitas, and Caddos, Spaniards operated as just another collection of bands like themselves in an equal, if not weaker, position to compete for socioeconomic resources in the region. Throughout the century, different Indian groups made it clear that they viewed each Spanish settlement as an individual entity. At midcentury, allied Wichitas, Caddos, and Tonkawas maintained peace with Spaniards living at Los Adaes while making war against those at San Antonio de Béxar and the nearby mission-presidio complex at San Sabá. Karankawa peoples along the coast saw no conflict between keeping up a long-running war with the people of La Bahía while entertaining diplomatic negotiations with San Antonio officials. Conversely, coastal-dwelling Akokisas saw no reason to petition the governor of Texas for a mission while visiting San Antonio because they believed each Spanish settlement to govern itself independently and so queried authorities in La Bahía instead, since that was the settlement nearest their own.

The attenuated position of Spaniards in Texas was no mere fancy of Indian observers. Spaniards did indeed operate similarly to Indian bands, living in farming and ranching settlements, loosely allied so that their small contingents of soldiers came to one another’s aid if and when able to do so in times of threat. Economically, they were often worse off than their Indian neighbors, as high risks and high costs of transporting imports over great distances stymied a reliable supply of goods from Veracruz. Exports also remained almost nonexistent due to the lack of production of domestic trade goods and the absence of mining. What little market economy emerged consisted of mission and civilian farms and ranches supplying food to the military. In turn, only presidio payrolls brought cash into Texas. Ranching did not take off until the 1770s and 1780s, when peace agreements with Wichitas and Comanches slowed the raiding of herds and market conditions in northern Mexico and Louisiana encouraged the Texas industry to expand beyond subsistence into cattle drive exports. Trade to the west with New Mexico required practically impossible passage across Comanchería, and thus routes, much less exchange, remained nonexistent until the end of the eighteenth century. Saltillo (south of the Rio Grande) emerged as the nearest market center for Texas residents, and even then, Texas Spaniards only began attending the annual trade fairs there regularly in the 1770s. Along the Texas-Louisiana border to the east, isolated Spaniards in Los Adaes and later Nacogdoches (est. 1779) depended upon exchange with Caddos and Frenchmen for their very survival (despite Spanish trade prohibitions that only periodically relaxed to allow for trade in food). All these problems reflected and refracted Spanish officials’ failures to attract a growing population to Texas in the face of the ever-present threat of Indian neighbors—creating what David Weber has termed a common conundrum in much of the northern provinces: “there would be safety in numbers, but they could not raise the numbers without guarantees of safety.”6

Spaniards in Texas therefore struggled to establish a presence among multiple native groups who had no need for mission salvation or welfare, no fear of Spanish military force, and no patience for the lack of Spanish markets or trade fairs (especially in comparison with those offered by Frenchmen in Louisiana and by Spaniards in New Mexico). The primary power relations were not European versus Indian, but relations among native peoples. At stake were regional networks and territories that could be used to the advantage of individual groups in order to protect and to expand their domestic political economies. Resource management, trade, and economic well-being determined territorial imperatives. When it came to Spaniards, Indian groups like Comanches and Wichitas had an easy choice: if they could not trade for Spanish guns and horses, they simply would take them by force. Thus, for much of the eighteenth century, Spanish settlements in Texas earned native attention only as targets for raids. As a result, Spanish-Indian contact long remained limited to an exchange of small-scale raids and attacks from which no stable structures of interchange developed. With little incentive to be in contact, much less to seek accommodation, Indians and Spaniards found that disorder and violence defined their relations in the region as much as, or more than, order and peace. In this particular “colonial” world, Indians not only retained control of the region but also asserted control over Spaniards themselves.7

Texas thus does not fit any of the usual categories posited in colonial and Native American historiography. No stories of Indian assimilation, accommodation, resistance, or perseverance here. Eighteenth-century Texas, instead, offers a story of Indian dominance. As such, Texas forces us to reconsider the expectations we bring to European-Indian encounters in early America. Our very term for the period, “colonial America,” not only describes the relationship between colony and mother country but also presumes European political domination over the territories and peoples of this supposedly “New World.” To paraphrase Daniel Richter (a bit out of context), “invasion” and “conquest” trip all too easily off our tongues because the “master narrative of early America remains essentially European-focused.” That easy-if-lamentable conquest model triggers certain formulaic assumptions that are rarely questioned because it is so terribly difficult to reverse our perspectives—not only to reimagine the past from Indian frames of reference but to rid ourselves of 20/20 hindsight that tells us “how it all turned out”: the United States in control of North America and much-reduced native populations living as semisovereign nations on reservations within the U.S. domain. No matter how determined the attempts to envision Indian perspectives or to champion Indian “agency,” our foundational model always puts Indians on the defensive and Europeans on the offensive. But Texas was different. There, not even a “middle ground” emerged, because this was not a world where a military and political standoff could lead to a “search for accommodation and common meaning,” as drawn so persuasively by Richard White for the Great Lakes region. In Texas, native peoples could and did gain their ends by dominant force.8

The first aim of this book, then, is to reframe the picture by visiting a world in which Indians dictated the rules and Europeans were the ones who had to accommodate, resist, and persevere. This story qualifies the narrative of “colonial America” by countering teleological visions of European invasion and Euroamerican manifest destiny leading inevitably to the creation of the United States. The first step is to invert our standard model. Studies of Spanish American borderlands, for instance, recognize so-called frontiers as “zones of constant conflict and negotiation over power,” but only because such regions were “boundaries beyond the sphere of routine action of centrally located violence-producing enterprises” (i.e., those of the state). From a Spanish perspective, the frontiers and borderlands of New Spain’s far northern provinces were indeed peripheries, far from the imperial core. And from this perspective, the question of control in these peripheries measured the extent or limit of New Spain’s ability to exercise a “monopoly on violence” over Indian subjects, or potential subjects, far from its institutional center. Yet, it is impossible to understand Texas without recognizing it as a core of native political economies, a core within which Spaniards were the subjects, or potential subjects, of native institutions of control. Spanish authorities encountered already existent and ever-expanding native systems of trade, warfare, and alliance into which they had to seek entry. Control of the region’s political economy (and with it, the “monopoly on violence”) rested in the collective (though not united) hands of Apaches, Caddos, Comanches, and Wichitas. By extension, native raiding served geopolitical and economic purposes, not as a form of defensive resistance or revolt, but of offensive expansion and domination.9

In turn, the second aim of this book is to illustrate the ways in which Indians dictated the terms of contact, diplomacy, alliance, and enmity in their interactions with Spaniards. More specifically, I seek a means of expanding our understanding of Indian-European relations and how we might delineate expressions of Indian power in a period that offers no records written from that perspective. To pursue this perspective, we need to move away from the European constructions of power that are so familiar to us—those grounded in ideas of the state and of racial difference—and try to understand the world as Indians did—organized around kinship-based relationships. To understand the institutions and idioms of power within this Indian-dominated world, we then need to analyze the ways various participants used languages of gender to understand and misunderstand each other.

Because no one Indian group ruled the entire region, and because native polities did not resemble those of Europeans, native institutions of control were not expressions of power by a dominant state within a clearly bounded society. Instead, they were negotiations of power between separate societies and nations. Different groups wielded power in different ways vis-à-vis Spaniards. Still, the fluidity of native political configurations as individual or allied bands, tribes, or confederations organized around familial, cultural, and linguistic affinity does not negate their structural integrity or the aptness of categorizing them as “nations.” A body of people, recognized as a nación by Spaniards, might represent both a cultural group of affiliated communities and a political entity controlling certain geographical territory. In turn, the vehicles of control through which native nations institutionalized their power over Europeans were not institutions like Spanish missions or presidios.10

Rather, networks of kinship provided the infrastructure for native political and economic systems and codified both domestic and foreign relations. “Kinship, society, politics, economics, religion,” anthropologist Raymond DeMallie explains, “are not for Native American peoples differentiated into independent institutions.” A certain holism prevails. At root, Indians used principles of kinship to classify people and their relationships with others. Such classifications determined peoples’ attitudes, behaviors, rights, and obligations to one another in every aspect of life. Those principles shaped relationships outside of society as well. For Indian leaders in Texas, the Spaniards who sought access to their political and economic networks did so as “strangers” to kinship systems of familial relations and political-economic alliances. Kin designations were a prerequisite for interaction and thus were extended to Europeans (as they were to native strangers); social, political, and/or economic ties could not evolve otherwise. In response, Europeans were expected to abide by the expectations of that kin relationship. In this way, kinship ties were not simply metaphors but the very foundation of Spanish-Indian relations.11

As a relational model for native societies, kinship provided a certain system of categories that operated both socially and politically. Categories help people to establish a framework that makes sense of the world and the ordinary and extraordinary events of everyday life. People thereby use these categories “to comprehend the natural world and to organize the division of labor and the distribution of material goods, rights, obligations, status, honor, respect.” Categories are relative to others and so often appear as paired or contrasting sets that oppose and balance one another—earth and sky, man and woman, human and supernatural, order and chaos. As such, they emphasize the importance of relationships to the welfare of the human community. Kinship systems, in turn, rely on categories of gender and age as the primary determinants of peoples’ identity, status, and obligation vis-à-vis others.12

In contrast, by the eighteenth century, Europeans drew on categories of race and class to explain the social, economic, and political customs and laws governing all aspects of life. In colonial Latin America, for instance, a diversity of racial constructions (sistema de castas) developed over the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as Indian and African peoples were incorporated into Spanish society. Believing the success of their earlier conquests in Central and South America to lie in the superiority of their Christian “civilization” over native pagan “savagery,” Spaniards drew distinctions between Europeans and Indians, expanding the categories of conqueror and conquered into a caste system of sociocultural rankings. Categorizations that constituted differences of culture as differences of race reflected Spanish colonial domination. It was only with the establishment of hegemony and the ability to cast a relationship as one of subordinate and superior, however, that hierarchies of difference, constituted as race, developed. Thus, expressions of race became a signature of European power in cross-cultural relations.13

Because Spaniards never enjoyed such power in Texas, such a language of hierarchy rarely emerged outside of civil proceedings within its central town of San Antonio de Béxar. It was not that Spaniards did not think in racial terms, but they could rarely act upon them. The only Indians who fell into Spanish racialized caste systems meant to structure rank and order were those individuals who became a part of Spanish society. Indian peoples included in these social orders were those who had been officially “reduced” by the church and the state. Indian nations remaining outside the purview of Spanish society and government—the native majority in Texas—were not incorporated into such categorizations. In the upper echelons of Spanish imperial bureaucracy, officials might refer rhetorically to indios bárbaros or other generic groupings of Indians, yet even then the label was not used to convey a racial or cultural identity but rather a political one designating Indians independent of Spanish rule. Still, at the day-to-day level of provincial life in Texas, a man’s survival might depend on his ability to distinguish between Apaches and Comanches, and Spaniards did not have the luxury of lumping all Indian peoples into a single category. They depended on the amity of some groups against the enmity of others for the safety and well-being of their own families and communities.14

While some Indian peoples in North America expressed awareness of European categories of race in the eighteenth century, gender was the organizing principle of kin-based social, economic, and political domains within and between native societies. Therefore, gendered language appears “in descriptions of kinship and in the metaphors used in diplomatic negotiations, it affects perceptions of power and authority, practices and beliefs surrounding rituals, cosmology and spirituality, as well as production, reproduction, life and death, numbers, and mediations.” Groups in Texas related to one another as kin or as strangers, allies or enemies. Leading chiefs and warriors cast the bonds of military and trade alliances as “brotherhood” and the fictive kinship of male sodalities. Exchanges of women through marriage, captivity, and adoption provided further ties of both real and fictive kinship as different peoples became incorporated into one another’s trade networks, political alliances, and settlements. Men and women were both makers of kin. In turn, such practices weighted political and economic interactions with gendered standards of honor associated with family, marriage, and social relations. Masculinity and femininity were not fixed or static categories but were defined and produced by the interactions and relationships between men and women, among men, and among women. For Indians, the prism of kinship thereby defined political as well as social and economic relationships within the terms and expectations of male and female behavior.15

Spaniards, of course, were no strangers to ideals and standards of manhood and womanhood. European societies used gender and honor systems to structure relations between and among men and women, to allocate power in their civil, economic, and political systems, and to structure racial caste systems. The majority of studies examining the intersections of Latin American kinship and honor systems within Spanish-Indian relations have done so primarily in terms of enslaved, missionized, or subjugated Indians who were incorporated into Spanish society. The influential works of James F. Brooks and Ramón A. Gutiérrez on New Spain’s northern provinces document closely how Spanish society in New Mexico (where detribalized Indian captives and slaves made up almost one-third of that society) did or did not incorporate different native groups into systems of gendered honor and kinship, how kinship and honor in turn became bound up in class and race identity and hierarchy, and how native peoples within Spanish society sought to shape for themselves the codes governing their lives. Notably, Brooks draws a pointed comparison of Spaniards’ more rigid racial codifications of the enslaved Indians held in their settlements versus native kinship systems, like those of Comanches and Kiowas, that opened up a range of identities and ranks for the captured women and children they incorporated into their communities.16

Because gender operates as a system of identity and representation based in performance—not what people are, but what people do through distinctive postures, gestures, clothing, ornamentation, and occupations—it functioned as a communication tool for the often nonverbal nature of cross-cultural interaction. Gendered codes of behavior could convey either peace or hostility, power (submission or domination), and strength (bravery or cowardice). In the face of multiple dialects and languages, Indian peoples in Texas relied upon sign language in trade and diplomacy to communicate with one another, and these signs offered a starting point for their communications with Europeans as well. Spanish missionaries in the earliest expeditions described Indians “so skillful in the use of their hands for speaking that the most eloquent orator would envy their gestures.” Fray José de Solís asserted in 1767 that Indian sign language was common to all and that with it Indians could “converse for days at a time.” Such communication appeared so crucial to Spaniards, Solís wrote, that newly arrived missionaries to Texas “lose no time in learning these signs, so as to understand so many different tribes and so as to make themselves understood by them.” Without a shared spoken language, then, Europeans and Indians could use sign, object, appearance, gesture, action, ritual, and ceremony to express and interpret one another’s intent and purpose. The presence of translators did not obviate the need for signs and actions. As late as 1781, Wichita and Spanish men in an unexpected encounter “looked each other over” and made “many kind gestures,” even as a French interpreter stood by translating their words fluently.17

The often contentious tenor of relations encouraged Europeans and Indians to evaluate one another by visible dispositions, postures, and actions. In fact, transmissions of meaning were often made more powerful through visible demonstrations than through verbal declarations that could prove false, be misunderstood, or remain incomprehensible. For instance, one Spanish official worried about relations with Wichitas, fearing that “our lack of deeds cannot fail to estrange them, for words unaccompanied by acts do not suffice.” It was a two-way street, however. During negotiations the same year, another diplomat pleaded with Wichita leaders to “refrain from moving their lips to invent excuses which sooner or later their deeds would belie.” The Apache expletive “mouth of the enemy!” suggests the associations they made between enmity, speech, and lies. Quite simply, actions spoke louder than words. Thus, diplomacy’s gift giving, titles of honor, and hospitality rituals and warfare’s battlefield stances, trophy taking, and violent mutilation all became decipherable codes between men. The participation of women too—in rituals of respect, hospitality, and intermarriage or in hostage taking, ransom, and violence—gave expression to amity and enmity in gendered terms. In search of peace, Spaniards and Indians might find a seeming resonance across their gender practices—a common ground of meaning or cultural cognates—by which to relate to the other. Yet, as the term “cognate” suggests, Europeans and Indians did not always conceive of gender standards in the same way.18

Europeans and Indians alike measured military, and thereby political and economic, power in terms of warrior numbers and ability. The character of contact over the eighteenth century gave greater authority to certain kinds of masculinity associated with a military identity. Honor codes among multiple Indian peoples in the region were in the process of militarization as the spread of European horses, guns, and disease influenced hunting patterns, seasonal migrations, territorial and settlement locations, and balances of power—changes that increased the authority of war chiefs and warriors. The constancy of raiding and warfare also heightened concepts of militarized honor for the Spanish men who were called to defend against them, coloring their confrontations and negotiations with Indian nations. Dating back to the reconquista (reconquest) of Spain when Spaniards fought to reclaim Iberia from Moorish control after the Muslim invasion from North Africa in 711 (a struggle that finally ended successfully in 1492), Spanish society linked male honor with violence, warfare, and military occupation. Later Spanish conquests in the Americas only reinforced such associations. Spanish machismo had as much to do with exerting power—often violently—over other men as it did with exerting power over women. Indian and Spanish men thus interpreted and judged one another’s actions by their respective male honor.19

As Spanish and Indian men in Texas defined hostile actions primarily as masculine endeavor, the involvement of Indian women in cross-cultural relations assumed specific importance of its own. This is not to say that women were incapable of violent acts and men of peaceful ones, but the power of elemental associations of masculinity and femininity held sway, especially in unstable times. Indian peoples in this region had long associated women with peace—Cabeza de Vaca’s experiences in the sixteenth century indicated how native women moved freely across social and political boundaries as mediators and emissaries. The role of Indian women could equally serve more symbolic than active purposes when it came to political and economic diplomacy. Either way, relations with women opened up the potential of expressing peace rather than hostility, and alliance rather than enmity. While the presence of women offered the possibility of stabilization, however, the relative lack of women as actors on the Spanish side of the equation often brought an imbalance to these relations and meant that interactions remained only between sets of men. Women’s absence often had an important, negative effect on Spanish-Indian negotiations, making it harder for Spanish groups to break the cycles of hostility and tension that so dominated their interactions with Indian nations. As was the case with the Comanche emissaries of 1772 with whom this introduction began, enmity might define the tone and idiom of even the most ardent Spanish efforts at peace. As the century progressed, then, coercion and violence increasingly shaped political interpretations of native femininity and the political realities of native female experience.

Although all these factors—the lack of a common language, the use of nonverbal signs, a seeming universality of gender categories, and unstable political relations—played a role in making gender so prevalent in Spanish-Indian diplomacy, the central reason was simple: Indians in Texas controlled their political and economic relations with Spaniards, so that their kinship systems for ordering and understanding relationships provided the structure for cross-cultural diplomacy. And just as race was a construction of European power in other areas of colonial America, gender emerged as a signature of Indian power in interactions with Europeans here. This was a world dominated by Indian nations and to enter that world meant that Europeans had to abide by the kinship categories that ordered it and gave it meaning. To ignore or transgress that system meant that one became a source of chaos and disorder, and Spaniards did so at their own risk.

The succeeding chapters roughly follow the chronological order in which different Indian peoples came into contact with Spaniards over the eighteenth century. The six chapters fall into three period groupings, and each of the three has its own introduction to set the time, place, and actors from an Indian perspective. Chapters 1 and 2 explore the first three decades of the century, during which Caddo chiefdoms established relations with Spaniards who sent expeditions to Caddo territories beginning in 1689. Small contingents of Spanish missionaries and soldiers tried to make allies of the powerful and populous Caddos as the only means of defending New Spain’s northern provinces against feared French invasion. As both Frenchmen and Spaniards entered their lands, Caddos sought to ascertain their intentions and, if deemed potentially valuable allies, find a place for them in their economic and political networks. Through public rituals of greeting and hospitality, theocratic leaders of Caddo communities first incorporated visiting Europeans into their diplomatic ranks as men of recognizable status and honor. When Spaniards and Frenchmen expressed interest in settling in Caddo lands, Caddo conventions then required that they be assimilated as “kin” for permanent relationships to become possible. The different forms of French and Spanish incorporation into the Caddo world via female-informed practices of familial union illuminate the resourcefulness of Caddo social controls.

The third and fourth chapters turn to south-central Texas from the 1720s through the 1760s, when bands of Coahuilteco, Karankawa, and Tonkawa speakers used Spanish mission-presidio complexes to broker political and economic alliances. Within those complexes, Spanish and Indian peoples came together for subsistence, defense, and family building, and therein native standards of male and female identity and labor defined the form and practice of their political union. Apaches saw a different kind of political potential in the mission-presidio complexes, first subjecting them to raids as a new resource by which to expand the horse herds so valuable to their hunting and warfare needs. By midcentury, however, challenges from Wichita and Comanche competitors led Apaches to negotiate terms by which the Spanish complexes might become institutions of military alliance between European soldiers and Apache warriors, even as Apache leaders sought to keep their families separate and their women out of the reach of Spanish men.

The final two chapters explore Wichitas’ and Comanches’ economic and political transition from indifferent enemies to diplomatic neighbors of Spaniards in the 1770s and 1780s, when peace rather than war finally appeared to provide greater advantages to their communities. Spaniards responded eagerly, seeking to gain these fear-inspiring nations as new friends. Wichita and Comanche leaders used male honor codes to establish truces on terms that transformed military opponents into military “brothers.” Hostility and violence had such a strong hold over Wichitas’ and Comanches’ contacts with Spaniards, however, that women emerged as crucial components of diplomatic efforts to ensure that a nominal truce became a permanent peace. Both the coercive trafficking in women through hostage taking and ransoming as well as the mediating involvement of women as symbolic and active emissaries of peace offered a key to solidifying amity between Spanish, Comanche, and Wichita peoples by the late 1780s.

Plunged into a world ruled by Indian politics, Spaniards found they could not assert control beyond the boundaries of south Texas and had trouble negotiating the native power relations outside those boundaries. Without the force to conquer or the finances to trade, Spaniards had to accommodate themselves to native systems of control if they wished to form viable relationships with Comanches, Apaches, Wichitas, Caddos, and others. Thus, it would take nearly the entire century for Spaniards to succeed in selling themselves as better allies than enemies, for native groups to find the terms by which they could tolerate if not benefit from the Spanish interlopers, and for a tenuous peace to finally emerge. The prevalence of gendered codes of rank, status, and identity forcefully demonstrated natives’ power to make Spaniards accede to the concepts and rules governing native polities. As Spaniards struggled to play by those rules, the predominance of gender in their diplomacy served as a barometer of native power and European powerlessness.