Part One

Turn-of-the-Century Beginnings, 1680s–1720s

One day in the late spring, a Hasinai Caddo man hurriedly rode into his home town, bringing with him two men.1 Like many men from the town, he had been out on a deer hunt with his wife and children since the spring planting of corn, beans, tobacco, and sunflowers had been completed. He had had a successful trip, but that was not what brought him home with such speed. Rather, he came to announce the approach of a group of twenty-four men who had entered Caddo hunting territories and merited the hospitality of his community. He had found them carrying all their belongings on their backs while walking in the general direction of the Hasinai villages. They must have been far from home, because they were unknown to the man. Because they looked footsore and hungry, he had left one of his horses and some of the meat from his hunt with the man he could tell was a leader among the wanderers. After inviting them to visit his village, the man had gone ahead to alert village caddís (headmen) of their approach while his wife and children remained with the strangers as a pledge of his return. He took two of the newcomers with him as an answering pledge—so he understood—from the strangers that they would await his return; they could not speak his language, nor he theirs, so he had to interpret their intentions as best he could. Such pledges were customary gestures to him, but caution dictated that he not leave his family too long alone in the company of the strangers, despite indications of their goodwill. Oddly, no women traveled with the newcomers—an absence that normally would indicate a raiding party—so there was some room to wonder at his family’s safety among them. Yet, at the same time, the strangers carried heavy bundles that seemed more indicative of trade supplies than of weaponry. He could only hope he had understood their signs and behavior correctly. It had taken him half a day to get home, and it would be another day before he could speak with village leaders and a greeting party could be assembled to return to the meeting place.

In his account to Caddo caddís, several factors may have shaped the Hasinai man’s reading of the newcomers’ intent and purpose in Caddo lands. They bore no paint or decorations of war. Their clothes and belongings looked like those of traders displaying their wares. Members of the party wore dress similar to that worn by, and sometimes given to Caddos by, their Jumano trading partners to the west. Since Jumanos had acquired the accoutrements from settlements further west, perhaps these travelers came from those far western peoples. If Hasinai Caddos could obtain more from the newcomers, all the better. The new cloth and decorations made appealing additions to the turquoise and cotton cloth they already had gotten from those lands.2 Yet, unlike Jumanos and others to the west, the travelers came on foot, and their lack of horses might indicate that they came from a less prosperous nation. Their horselessness could also mean they were from the east; the Hasinais’ own well-established horse herds gave them an edge over their eastern neighbors who did not yet have them. Since the strangers had approached from a southwesterly direction, however, an origin nearer the Jumanos seemed more likely. Thus, although the strangers and their language were unknown to Caddos, aspects of their appearance gave the impression of a trading party like those they had hosted many times before. As it turned out, a Jumano trading party was at the Hasinai village when he arrived, so perhaps they could identify the newcomers if and when they were brought into town.

In response to the man’s report, several Hasinai caddís rode out, accompanied by a small contingent of amayxoyas (noted warriors), bringing with them two more horses loaded with food provisions, as hospitable custom demanded and as the practicalities of travel required. Members of the party had dressed in fine deerskin clothes and feather adornments and carried with them a ceremonial pipe (also ornamented with feathers) for their greeting rituals. Once the party of strangers was found and the ritual pipe smoke shared, the Hasinai men escorted the wanderers back to town. There, a great concourse of people inspected and greeted the visitors as they wound through the many hamlets making up the settlement on their way to a ceremonial compound where they would meet the principal caddí at his home. The size and breadth of the settlement, stretching for over twenty leagues, seemed to overwhelm the strangers, another hint that their nation might not be so large or prosperous as that of the Hasinais. In accordance with Caddo custom, the Hasinai escort directed the leader of the trading party to lodging within the principal Hasinai caddí’s household, while the rest of the party were told where they could camp outside the village for the four days that trading negotiations lasted. Regardless of this precaution, young Hasinai men stood guard in shifts day and night throughout the settlement.

Not surprisingly, given the poor condition of their party, the strangers wanted horses and food for the continuation of their journey, and since Hasinais could easily provide both, they offered five horses in addition to provisions and received some knives, axes, and ornaments in exchange. The visitors expressed equal interest in the Jumano traders already lodged at the Hasinai village, yet it was interest not in their goods but in the news they might have from the west. Contrary to what the Hasinais might have expected, the strangers knew neither the Jumanos nor the sign language that most nations in the region used to communicate during economic and political exchanges. Yet, the Jumanos certainly seemed to think they knew the strangers or people like them, so the Hasinai leaders let them take the lead in seeking to identify and communicate with the visitors.

The Jumano representatives thought one man in particular, an elder dressed in robes rather than the leggings of the others, might be able to communicate with them. They tried different signs, alternatively touching their chests in a pattern of motions with one hand, kneeling, and raising their arms to the skies. Finally, they drew an image on bark of a man being tortured on a post while a woman looked on weeping, an image that seemed to have some impact on the strangers. When the elder expressed excited recognition of these body movements—sign language, the Jumanos explained, that had been taught them by people in the west with whom they had been trading for quite some time, the strangers then indicated their desire to know the direction to those people. In response, the Jumanos drew a map on bark to indicate the region as a whole, rivers and landmarks, the location of neighboring nations, and a description of these particular people to the west.

Once the strangers learned the identity of the western-dwelling people, they seemed eager to disassociate themselves from them. Their leader began a long speech, with intermittent gestures at the sky (or was it the sun?—the Hasinai and Jumano onlookers were not sure), in which he seemed to recite mighty deeds of war. Although the stories remained indecipherable, the enmity he felt for the people in the west became clear. In response, the Jumanos tried to explain that the people of the west had recently angered them too. Just three years before, Jumano leaders had sent a delegation to the westerners’ settlement to seek explanation for their failure to honor trade agreements. In return, they had gotten a half-hearted commitment of military alliance against their Canneci enemies that had proven ineffectual or unfulfilled within less than a year.3 Now, they were considering a battle or raid against the western people and invited the newcomers to join them if they wished.

After five days, the strangers finally went on their way with what the Hasinais hoped would help their travels: five horses and a supply of maize, beans, and pumpkin seeds. A few days later, however, news arrived that did not surprise those in the Hasinai settlement. Under cover of night, four men from the trading party had reappeared at a neighboring Caddo village, that of Nasonis. Apparently not wishing to travel further, the men had left their leader and comrades and returned to the village to ask whether they might stay among the Caddos. The Nasonis sympathized with their needy situation and offered them new homes, at least temporarily. To the Hasinais, the desertions may have bespoken a failure of leadership.4 The strangers’ party had not seemed well-equipped to survive; beyond their lack of supplies, many did not appear to have a warrior’s strength and fortitude required for a long journey. Indeed, events a few months later confirmed these suspicions. Hasinais and Nasonis (in whose society domestic murder was unheard of) watched with shocked dismay as the strangers killed their caddí and then turned against one another, until the dissension ended in three more murders.

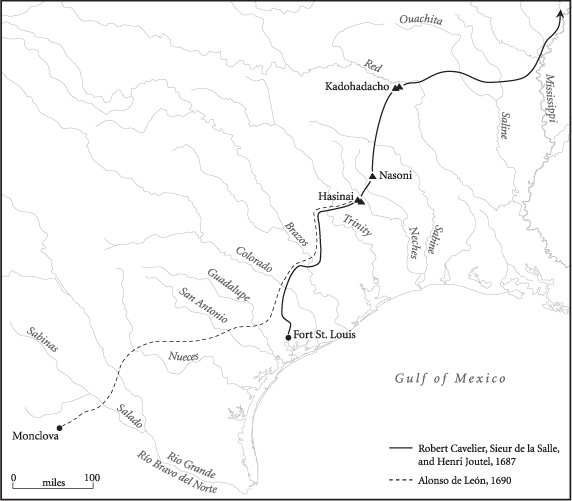

This passage tells the story, from a Caddo perspective, of the first contacts between Caddos of the Hasinai confederacy (who would later be known as “Cenis” by Frenchmen and as “Tejas” by Spaniards) and René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle, and members of his 1685 expedition into the region that would memorialize Hasinais in its name: “Texas.” The Frenchmen who arrived at the Hasinai villages that spring were survivors of an excursion sent to find, chart, and claim the Mississippi River for France. Failing to recognize the mouth of the Mississippi River, however, La Salle’s ships had landed on the Texas coast in January 1685, where they established a settlement named Fort Saint Louis in or near Karankawa territories. La Salle had then sent parties inland in hope of finding an overland route to the Mississippi River and a way back to French settlements in Illinois and Canada, and their northward searches took them through Caddo lands.

Their Hasinai hosts were members of one of three affiliated confederacies among Caddoan peoples. Caddos had maintained a thriving culture in the region for over eight hundred years, with agriculturally based communities spread thickly over an area that encompassed hundreds of miles in parts of present-day Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. Although their numbers had declined drastically from an estimated 250,000 people in 1520, they remained the dominant power in the region. The majority of the 8,500 to 12,675 people had coalesced, by 1690, into three confederacies, or chiefdoms, known as Hasinai, Kadohadacho, and Natchitoches.5 Twenty member bands of these confederacies and at least three other independent Caddo bands now clustered in fertile river valleys of present-day northwestern Louisiana and northeastern Texas, along the Angelina, Neches, Sabine, and Red Rivers. As fray Isidro de Espinosa, a Franciscan missionary who lived among Hasinais from 1716 to 1722, described, the Hasinai nation “extends in each of the four principal directions for more than one hundred leagues.”6 The governance of the multicommunity chiefdoms remained quite similar to their earlier political systems. Town centers, surrounded by a multitude of temple mounds built by their ancestors up through the fourteenth century, still served as both the residence of paramount chiefs and the locus for public gatherings and ceremony. Kin-based hamlets located near agricultural fields radiated out from these centers. A balanced kinship system structured Caddo societies. Matrilineage defined the ranks and divisions within their communities, while hereditary hierarchies that passed power independently via a patrilineage governed the bands and confederacies. Caddo economies rested upon steadily intensifying agricultural production and a far-reaching commercial exchange system trading hides, salt, turquoise, copper, marine shells, bows, and ceramic pottery long distances into and out of the regions of New Mexico, the Gulf coast, and the Great Lakes.7

The effects of European contact had begun to reach Caddoan peoples long before these French visitors arrived at the end of the seventeenth century. Another straggling expedition, the exploratory party of Hernando de Soto, led by Luis Moscoso after Soto’s death, had rampaged through their lands in 1542.8 Almost one hundred and fifty years passed before La Salle’s venture to Caddo lands, and no Caddos seemed to know about the earlier European visitors. Yet, the effects of the sixteenth-century contact—long-term population decline in response to the epidemic diseases that Soto’s expedition had left in its wake—had certainly made its mark on Caddoan peoples. Though their dispersed settlement patterns had reduced the spread and severity of disease, smaller populations made the previously high number of independent agricultural communities more difficult to defend and encouraged the consolidation of Caddo bands into the confederacies that Frenchmen and later Spaniards encountered in the 1680s.

Despite that population decline, the Caddoan world remained impressive in size, breadth, and development. French priest Anastase Douay described his first sight of the great Hasinai settlement in 1686: “This village, that of the Cenis, is one of the largest and most populous that I have seen in America. It is at least twenty leagues long, not that it is constantly inhabited, but in hamlets of ten or twelve cabins, forming cantons, each with a different name. Their cabins are fine, forty or fifty feet high, of the shape of beehives.” He concluded they were a people “that had nothing barbarous but the name.”9 Because of their confederacies’ economic and political strength, Caddo leaders viewed European newcomers as insignificant. Yet, as increasing numbers of regular visitors replaced the early wanderers, these leaders saw that perhaps Spaniards and Frenchmen might be usefully incorporated into their already extensive political economies by carrying Caddo trade goods in new directions and bringing new ones back to them in return. Still, Europeans from the northeast and southwest entered Caddo orbits only as aspirants.10

In 1686, Caddos greeted the newly arrived Frenchmen hospitably, with little reason to associate them with past events or past foreigners. Caddo custom dictated the rituals offered to La Salle as leader of the visiting party—housing in one of the caddís’ homes, presentations of food, pipe-smoking ceremonies, and diplomatic exchanges. For the French party, though these early exchanges were a success, the initial trip northward was a failure. La Salle was murdered by several of his own men on his second attempt to reach the Mississippi (just a few miles from the Hasinai settlements), but seven survivors eventually made it to Illinois posts in 1687. Meanwhile, in 1688, Karankawas destroyed the struggling settlement on the coast in response to repeated French thefts and harassment. As a result, Hasinais encountered more French deserters and survivors (eight of whom remained to live among them) while other Caddos to the northeast met rescuers from Illinois under the leadership of Henri de Tonti, who came in search of the lost French settlement. The friendliness of these early exchanges later convinced French officials in Illinois and France that Caddos could be key to expanding their economic networks in Louisiana in pursuit of trade both with Native American peoples in the south and southwest and with Spaniards in New Mexico. Within the next fifteen years, trading outposts in Illinois and seaports in France would send more Frenchmen to Caddo lands.

Routes of the earliest French and Spanish visitors to Caddo lands in the 1680s and 1690s. Map drawn by Melissa Beaver.

Meanwhile, as reports of La Salle’s venture filtered in from different sources in the Spanish empire, officials in New Spain began to spin out a quite different narrative of the events they believed to be taking place in the “land of the Tejas.” In 1685, reports had reached viceregal officials in Mexico City and, eventually, the Council of the Indies in Madrid of a serious threat to Spain’s colonial possessions in the Americas. All told, the reports indicated that a “Monsieur de Salaz” had gathered a maritime expedition made up of four ships carrying 250 people, including soldiers, craftsmen, missionaries, settlers, and at least four women, to establish a colony at a place called “Micipipi” along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico in Spanish territory. Well-provisioned with guns, tools, and merchandise for trade, the Frenchmen, it seemed, planned to build a fortress from which they could win over Indian allies and ultimately assert control over the rich mines they had been told lay within reach of the Mississippi. The Spaniards could only conclude that these mines were in fact their own and that the colonization plans represented a scheme to conquer the northern settlements of New Spain.11

Over the next four years, Spanish officials sent eleven different expeditions, five by land and six by water, in search of the rumored French colony. When in 1690 a party led by Alonso de León finally found La Salle’s Fort Saint Louis on Matagorda Bay, it had been destroyed by disease and a Karankawa attack. Only a handful of French deserters and children living among and adopted by Caddos and Karankawas remained to tell Spaniards of the initial goals and ultimate fate of La Salle and his colony. It mattered not to Spanish officials that the expedition lay in ruins and the expedition leader himself had died at the hands of his own men, however. Protection against another attempted French intrusion had to be secured.12

Spanish state and church officials had been discussing the potential of trading posts and even presidial settlements for the region to the east of New Mexico for over fifty years, ever since the 1620s when Jumanos had first traveled west to initiate contact with Spaniards. Since 1650, Spaniards in the province of New Mexico had been sending scheduled trading expeditions, under military escort, to Jumano settlements at the confluence of the Nueces and Colorado Rivers to exchange Spanish products first for pearls (from river shells) and later for deerskins and bison hides. A growing eastern Apache presence in the region made the military escort a necessity, and the need for defense against Apaches had further encouraged some Jumanos’ interest in a potential alliance with Spaniards. The increasing dangers in fact eventually stopped the Jumanos’ visits to New Mexico and forced Spanish expeditions to come to them instead if they wanted to maintain contact. The continuing expeditions attest to Spanish interest not only in the Jumano peoples but also in their Caddo trading partners, whom the Jumanos had spoken about in glowing terms to Spanish officials.13

From Jumano reports, Spaniards in New Mexico gathered that the “Kingdom of the Tejas” was a populous and powerful nation, with a “king” or “great lord” who ruled with “lieutenants” over a people so numerous their cities extended for miles, so powerful that their warriors were feared by all neighboring groups, and so organized that they had a hierarchical governing system. Balancing “civilization” with strength, the Hasinais enjoyed an agricultural economy successful enough to produce surplus grain for their horse herds, worshiped a single omnipotent deity, and maintained a material trade that supported a well-dressed and well-housed people. As a result, Spanish officials thought they recognized in the Hasinai world social, political, and economic practices not too unlike their own, and in the Hasinai people, good candidates for alliance and religious conversion.14

At the same time, Jumano traders carried to the Hasinais both Spanish goods and their own impressions of Spanish soldiers. Viewing Spanish horses, ornamented swords, and items of personal adornment such as lace, silver, and military clothing and listening to stories of Spanish warfare, slave raiding, and missions, Hasinais too may have recognized attractive characteristics in Spaniards—a people with warriors as reputable and decorated as their own, riders of heralded horsemanship, and traders interested in mutually profitable exchange. The predominance of horses already in Caddo settlements (that Frenchmen had carefully noted) suggested that Caddos would view Spaniards as an invaluable trade source for expanding their horse herds. Yet, by the 1680s, Jumano reports to the Caddos also came with a warning: Spaniards had not proved reliable trading partners since the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 in New Mexico. Moreover, the revolt had completely removed a Spanish presence from the Pueblo region, pushing them back to a location along the Rio Grande, where they had established a new settlement called “El Paso del Norte.” Not only had the revolt disrupted all political and economic relations that Spaniards had sought to maintain among several native populations, it had also suggested to native leaders a real weakness in Spanish military capabilities—all of which may have reduced the Spaniards’ appeal as allies of any kind, be it for trade or diplomacy. That appeal had certainly declined in the Jumanos’ opinion, but Caddos as yet had little reason to decide either way.15

Even as Spaniards struggled to find the means to reestablish a presence in New Mexico, they faced a new, French challenge from the east. Fortuitously, it seemed to viceregal officials, the search for La Salle’s colony had fixed Spanish attention upon “Tejas” Indians. Alonso de León and fray Damián Mazanet, who headed the 1690 expedition that found the remains and the survivors of the ill-fated French colony, elaborated upon earlier Jumano reports of the advanced “civilization,” commercial power, and political influence of the Hasinais and their many fellow Caddo allies along the Red River. Their reports encouraged Spanish officials to conclude that the Hasinais represented both promising converts to Christianity and important allies to be won against the French. Since La Salle’s expedition had proved the Spaniards’ vague fears of French expansionism to be real, Spanish officials quickly initiated plans to court a Hasinai alliance in earnest. Thus, Spaniards envisioned a bulwark against French aggressions created through settlement in the “land of the Tejas.” Whether Hasinais would offer the same welcome to Spaniards that had comforted the French stragglers and survivors of La Salle’s failed expedition, however, remained to be seen.