Chapter One

Diplomatic Ritual in the “Land of the Tejas”

In the 1680s and the 1690s, multiple Caddo groups within the Natchitoches, Kadohadacho, and most notably the Hasinai confederacies began to give hearings to the various European aspirants who came to their lands, seeing in them the possibility of meeting ever-increasing political and economic needs for horses, guns, and military allies. Over time, Hasinai goals and Spanish and French ability and willingness to meet those goals determined the shape and form of eighteenth-century socioeconomic relations. Yet, in the last two decades of the seventeenth century, these Europeans and Indians struggled simply to establish contact with one another. The earliest meetings between Caddos and their French and Spanish visitors delineated what might be imagined as the outer rings of cross-cultural interaction. Their encounters skimmed the surface of Caddo and European societies by calling into action only the most public manifestations of male and female honor required by formal diplomatic ceremony.1

Caddo, rather than European, custom dictated the ceremonies followed in the first meetings of these peoples, making clear the Caddos’ power over their European visitors. Unable to communicate well with each other through speech, Europeans and Caddos searched for other means to convey and interpret meaning—making object, appearance, expression, and action critical. They brought together their respective traditions of ceremony and protocol in efforts to establish diplomatic exchange. The Caddos’ advantages of home ground, superior numbers, and force offset any presumed military superiority afforded by European technology and arms. Frenchmen and Spaniards arrived in such small numbers relative to their Caddo hosts that aggression on their part would have been foolhardy and self-destructive. The European newcomers thus followed the Caddos’ lead in protocol.2

Caddo hospitality rituals conveyed and affirmed honor both domestically and diplomatically. Ceremonies of early contact included all members of Hasinai communities and reflected the civil and political dimensions of Hasinai identity, position, rank, and prestige. Welcoming rituals allotted to all persons a role commensurate with their position and contribution to the society and presented to observers the social value of each. Status position accorded by social order and hierarchies of age, lineage, and gender thereby determined individual and community roles in Caddo ritual performances. Caddo men and women of both elite and nonelite status had their parts to play. Europeans thus enjoyed a composite view of Caddo societies in their own villages, temples, and ceremonial centers—how adequately or poorly they interpreted what they saw was another matter entirely.3

In contrast, Caddos gained only a faint glimpse into Spanish or French cultures, their view being limited to the few men who wandered into and out of their lands in the 1680s and 1690s. They saw nothing of the Europeans’ own communities and socioeconomic systems, and among the groups with whom they did interact, Caddos could make judgments only of the divisions and ranks structuring relations among Spanish and French men because the parties were all-male. The Frenchmen and Spaniards that Caddos met also presented quite contrasting pictures to them. In 1689, for example, Alonso de León’s expedition included a military leader, about ten officers, eighty-five soldiers, two missionaries, one guide, one interpreter, and twenty-five muleteers, craftsmen, and laborers in charge of supplies, food stores, and manual chores. Those stores included seven hundred horses, two hundred head of cattle, and pack mules carrying eighty loads of flour, five hundred pounds of chocolate, and three loads of tobacco. In contrast, the French survivors and deserters from La Salle’s Fort Saint Louis came on foot, carrying their supplies and what goods they hoped to trade on their backs, and they arrived in much smaller numbers; twenty-four men made up La Salle’s first party and seventeen the second. At the beginning, then, cross-cultural understanding, if even possible, was inevitably uneven.

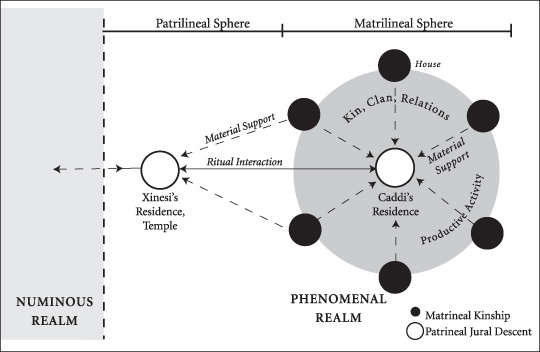

In the early stages of contact, when both the Europeans’ and the Caddos’ goals remained simply ascertaining a starting point for friendly relations, the key exchanges were those between elite men, mostly because of Caddo custom. Rituals reflected the sociopolitical categories of Caddo society, in which patrilineal descent of political and religious leadership existed within a larger matrilineal kinship system. Caddos lived in dispersed settlements, each of which consisted of multiple family farmsteads of generally equivalent status. These local communities allied together to form larger confederacies. Caddís, men of civil and religious authority, headed each village and were advised by councils of elders called canahas, while a xinesí functioned as a head priest at the level of the confederacy. These positions were all hereditary offices, almost all male (Spanish and French records indicate two historical moments in which extraordinary circumstances put women into positions as caddís), and passed by descent through a male line but within the matrilineal kinship system—for example, from a man to his sister’s son.4

Diagrammatic representation of houses and ceremonial centers (caddís’ and xinesís’ residences) as icons of matrilineal and patrilineal spheres, by George Sabo III, “The Structure of Caddo Leadership in the Colonial Era,” in The Native History of the Caddo: Their Place in Southeastern Archeology and Ethnohistory, ed. Timothy Perttula and James Bruseth, Studies in Archeology, no. 30 (Austin: Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, 1998). Courtesy of George Sabo III and the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, University of Texas at Austin.

Meanwhile, households under the authority of the matrilineal clan functioned as the basic social and economic unit of production. Women, as heads of clans, held primary authority in Caddo cultivation, organized divisions of farming labor, and controlled the agricultural produce. Caddo cosmology established the interdependence of patrilineal leaders and matrilineal clans in the origin story of Ayo-Caddí-Aymay, the Supreme Being, which fray Isidro de Espinosa recorded in the 1720s. In the beginning of the world, only one woman and her two daughters (one of whom was pregnant) existed, and one terrible day a demon in the form of a giant horned snake attacked and killed the pregnant daughter. A miracle saved the son she carried in her womb, and under the remaining women’s care, he grew to adulthood in two nights and immediately avenged his mother’s death by killing the demon with a bow and arrows crafted by his grandmother. The young man, accompanied by his grandmother and aunt, then ascended into the sky, where he began governing the world as the Supreme Being. Thus, a founding matrilineage of three women restored “positive conditions in the world by empowering male descendants to act on their behalf.” The women ensured the youth’s success in the male realm of warfare (and ultimately political leadership). Male skills, and the power they garnered, depended upon female skills in women’s realm of production and sustenance.5

Reflecting those sociopolitical divisions, public ceremonial life in Caddo societies took place in gendered spaces to which Europeans—as men—did not have equal access. The ritual performances held at temples and ceremonial compounds, in which native and European foreigners were more likely to be included, highlighted the authority of male political and religious leaders—the caddís, xinesí, and canahas. Women took part in ceremonies at the compounds, but their authority was not the focus of that venue. Rituals performed in individual homes emphasized the matrilineal structuring of clan, kinship, and socioeconomic units of production. Planting, first fruits, and harvesting ceremonies held in the home were public rituals reinforcing the social basis of kinship and women’s productive contributions to both family and community. Europeans, however, were far less likely to witness these seasonal ceremonies in their initial visits to Caddo lands. In turn, the potential gender biases of European men, whose own societies had no similar balance of public authority for women as well as men, did not initially have much bearing on diplomatic proceedings.6

Thus, from the beginning, gender influenced what Europeans learned and did not learn about their hosts. Europeans did not have a chance to be surprised by Caddo women’s power because they did not witness it, at first. The encounters recorded by Europeans between 1687 and 1693 make clear that Caddos welcomed Spaniards and Frenchmen only into the ceremonial compounds where male-defined rituals held sway. In these spaces, masculine power was the source of mutual understanding. As ethnohistorian George Sabo explains, “the ritual performances that were enacted in the context of encounters between Europeans and American Indians were staged . . . to convey those beliefs, values, or principles that one or the other (or sometimes both) of the participating groups considered appropriate or necessary for the situation at hand.” As symbolic communication, ritual performances “served, among other things, to define and categorize participants according to systems of social classification and to establish ‘ground rules’ for cross-cultural communication and interaction.” Until Spanish and French male leaders had passed the tests set for them by their Caddo counterparts, only the male domain of Caddo polities would be open to them. Only later, after the rules had been laid out and accepted, might the locus of cross-cultural interaction expand to include the more female-influenced kinship rituals of alliance and settlement represented by the matrilineal household.7

What protocols did Caddos enact when Europeans entered the outer limits of their lands? La Salle’s story provides some hints, but a more detailed accounting can be elicited from Spanish expedition records. Hasinais customarily met European parties a few miles outside their villages for the first round of greetings. Once lookouts sent word of Europeans’ arrival in the vicinity of their villages, the caddís rode out to greet them, accompanied by men, women, and children in groups numbering anywhere from ten to fifty. When within eyesight of one another, both the Europeans and the Caddos halted to salute each other and then advanced in “military formation” according to rank, with all cavalry, arms, and munitions on display. Caddos entered the meeting ground in three files, with the central one led by the head caddí, followed by other caddís and leading men, and with the remainder of the people making up the two side lines. Echoing the Caddo formation, Spaniards advanced with the military expedition leader carrying the royal standard painted with the images of Christ and the Virgin of Guadalupe, while missionaries and soldiers filed in on either side. The military captain then passed the standard to the head missionary, knelt before it in veneration, kissed the images, and embraced the missionary or kissed his hand or habit. Spaniards sang the Te Deum Laudamus as they processed, and in response, Caddo men gave another salute.8

Upon exchanging initial courtesies and gifts, the caddís would escort visitors into their village. Europeans sometimes proffered gifts to the man they assumed to be “head chief,” particularly gifts of clothes, so that he might carry or wear them into the village in symbolic recognition of the respect they had for him. As the Spaniards or Frenchmen entered settlements, entire bands of three to five hundred men, women, and children welcomed them. Entry to the village usually repeated the ranked processions for the benefit of the village audience, as all paraded to a public plaza where blanketed and adorned seats were set out. After more salutes (in early years, with hand gestures, but later with gunfire), Caddo men often took care to lay down their arms. Finally, before sitting, leading warriors and caddís embraced Spanish or French officers and missionaries, and the visitors then went through a purification ritual, often by having their faces washed or by smoking pipes.

During the formal meetings that followed, the leading men of both Caddo and European parties sat in a circle on special benches designated for them according to rank, and the people of the village ranged around the circle of dignitaries as audience. Caddo men brought out a pipe decorated with white feathers, and the caddís mixed their own tobacco with that given them by the visiting Spaniards or

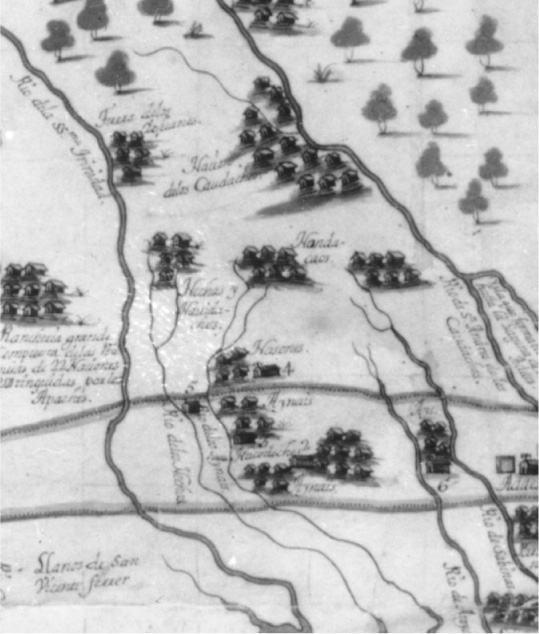

Detail showing the lands of the Tejas from the 1728 map drawn by Francisco Barreiro, the engineer who accompanied Inspector General Pedro de Rivera’s 1724–28 inspection tour of the defensive capabilities of New Spain’s northern provinces. Courtesy of The Hispanic Society of America, New York.

Frenchmen and blew smoke to the cardinal directions—east, west, north, south—and to the earth and the sky. Then they offered the pipe to their European counterparts and thereafter to all present, until it had passed through everyone’s hands. Next, the European and Indian leaders addressed speeches to one another, using interpreters to translate as best they could. Caddo women then brought forward corn, watermelons, tamales, and beans for the feasts that followed. In exchange, Spaniards and Frenchmen usually offered gifts of clothes, flannel, blankets, hats, and tobacco to be distributed among all the village inhabitants. European officers designated special gifts for the caddís, their wives, leading warriors, and any others deemed to be in positions of authority. Frenchmen also gave guns and ammunition. After these formalities, more feasts, dancing, singing, drumming, blowing of bugles and horns, and firing of salutes created a festive atmosphere as celebrations continued through the night. Caddís then insisted that expedition leaders and missionaries stay with them in their own households. For several days, this pattern of festivities continued, with groups from neighboring Caddo villages often coming to meet the Europeans, or with Spaniards and Frenchmen going to their settlements to enact similar rituals.

Through these rituals, Caddos, Spaniards, and Frenchmen sought to introduce themselves, to convey friendship, and to evaluate one another as potential military allies and trading partners. Europeans were not singled out for special treatment; these were the same ceremonies Caddo leaders used when entertaining native foreign embassies. As fray Espinosa later attested from firsthand observations, caddís received native ambassadors “with much honor,” meeting them leagues outside of villages with formal escorts, assigning them principal seats at meetings, and giving presents, dances, and festivals during their visits. Such foreign policy receptions were annual events among a number of different bands inside and outside the Caddo confederacies. Hasinais, for instance, welcomed diplomatic parties from the Gulf coast, “who are accustomed to come as allies of the Tejas in times of war . . . [thus] they entertain them every year after harvest, which is the time when many families of men and women visit the Hasinais,” Espinosa explained. It was also “the time when they trade with one another for those things lacking in their settlements.”9

Notably, native visiting parties included women and children to emphasize the diplomatic nature of the mission. Practical demonstrations of peace involved specific male and female behaviors. Europeans might focus on male actions, but for Caddos and other Indian peoples across Texas, the clearest signal of intent lay in the gendered makeup of visiting parties. For them, the inclusion of women and children in traveling and trading parties communicated a peaceful demeanor, because customarily, female noncombatants and families rarely accompanied raiding or warring parties. Thus, Caddo “welcome committees” sent out to greet visitors prominently advertised the presence of women and children. If women did not attend the first meeting, Indian leaders often insisted that Spanish and French expeditions return to their villages to greet their women and children there. French priest Anastase Douay, for example, recorded the “pressing” invitations of a caddí to visit his settlement and thus his people. In similar spirit, neighboring Yojuanes entreated the 1709 expedition of fray Isidro de Espinosa, fray Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares, and Captain Pedro de Aguirre to come with them to their settlement, arguing that their women and children would be “very sad and disconsolate” if they did not meet them. Caddo women’s and children’s involvement in visitor receptions served as marks of trust vested by Caddo hosts in their visitors. By presenting women and children, caddís acknowledged the visitors’ peaceful intent and conferred honor on them by conveying the leaders’ faith that the vulnerable or noncombatant members of their communities would be safe in the visitors’ company.10

Ritualized touching provided a physical extension of these gestures of peace for many Texas Indian groups. The very gestures established a bond by transferring touch back and forth between people. Thus, fray Isidro de Espinosa compared Indian caresses to a “manner of anointing.” Frenchmen of La Salle’s expedition were embraced and caressed all along their path from the coast to Caddo settlements. When some of La Salle’s men encountered Karankawas along the coast of Texas in 1685, the Indians approached as soon as the Frenchmen had disarmed at La Salle’s command and “made friendly gestures in their own way; that is, they rubbed their hands on their chests and then rubbed them over our chests and arms.” After this ritual, “they demonstrated friendship by putting their hands over their hearts which meant that they were glad to see us”—greetings that the Frenchmen returned “in as nearly like manner as we could.” The Indians further inland also signaled friendliness, according to Joutel, by putting their hands over their hearts and, he believed, communicated a desire for alliance with the Frenchmen by hooking their fingers together. Upon reaching Caddo settlements, Hasinais too embraced them “one after another” to demonstrate their affection.11

The act of touching transformed a greeting into a personal bond because the proximity and intimacy required for the act conveyed both trust in the visitor and sincerity in the host. Symbolically expanding the welcome to include the whole community entailed the involvement of men, women, and children in these ritual gestures. Thus, gender again served as a central means of communication and, as it would turn out, miscommunication. Europeans like Anastase Douay often particularly noted women’s participation in physical greetings, recording that Indians “received us with all possible friendship, even the women coming to embrace our men.” Captain Domingo Ramón argued that, in the Hasinai ceremony, first the caddí and then all the warriors, women, and children in succession “threw their arms around” him and the missionaries—and thus the ceremony took more than an hour to complete—which he decided must be “significant of friendship.” Fray Espinosa found that “there was not an Indian, man, woman, or child, who did not do his or her share of petting.”12

Europeans quickly adapted to native practice, as a missionary in the 1718 Alarcón expedition, fray Francisco de Céliz, recorded: “we caressed them by embracing them,” following their “customary signs of peace.” But adaptation did not come easily for them. European notions of male self-mastery associated masculine strength with control of thought, emotion, and body. Religious custom, which Spaniards hoped to encourage Indians to imitate, allowed for kissing Franciscans’ habits and sometimes their hands. Beyond that, however, they limited bodily contact to good friends and boon companions. When Indians made clear that their courtesies called for reciprocity, the struggles of Spaniards and Frenchmen to do so reflected their discomfort at this unfamiliar diplomatic requirement. Henri Joutel reported with seeming nonchalance an encounter with two women who “came to embrace us in their special way” and continued the gesture by “blowing against our ears.” Yet when several men followed suit by greeting the Frenchmen “in the same way the women had done,” Joutel and his companions broke out in nervous laughter.13

Since European expeditions precluded families, they had no women to offer the same assurances of peace. Not surprisingly, given the signal importance of women and children to regional Indian greetings, Caddo leaders noted with concern the “strange” absence of women among Spanish and French expeditions, an absence that potentially signaled hostile intentions on their part. Lacking a shared language or, for that matter, shared symbolism, European men had to find other gestures or actions with which to express an absence of hostility. Supplementing women’s presence, Europeans noted, Caddo custom often dictated that men assume nonhostile stances. Europeans thus recorded Caddo men’s ceremonial disarmings, laying down clubs, swords, bows, and lances. As Henri Joutel related, Hasinai men “indicat[ed] to us that they came in peace by putting their bows on the ground,” and in combination with other “signs,” such as dismounting from horseback, encouraged the Frenchmen of Joutel’s party to approach. Sometimes, as observed by Domingo Terán de los Rios, they came forward to meet Spaniards visibly bearing no arms. Here were gestures Spaniards and Frenchmen could answer in kind.14

The all-male delegations of Frenchmen were so small that they rarely represented a likely threat, and French efforts to match Caddo salutes and disarmings sufficed to offset initial suspicions. Spaniards, however, came in more extended and well-equipped expeditionary parties and thus presented a more alarming semblance of force. Though they came with no women, however, an unwitting exchange of female symbolism unexpectedly got Spaniards in the metaphorical door of Hasinai diplomacy in the 1680s and 1690s. In early efforts to introduce themselves to the Hasinais, Spaniards gave center stage to religious images of the Virgin Mary and to stories of María de Jesús de Agreda.

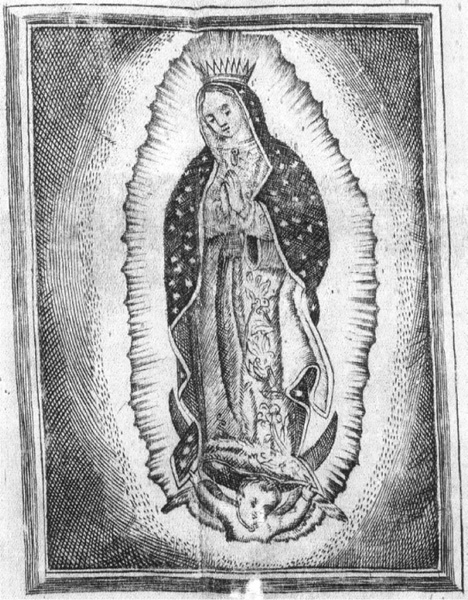

Engraving of María de Jesús de Agreda, the “Lady in Blue,” appearing before Indians to the east of New Mexico. Courtesy of the Catholic Archives of Texas, Austin.

According to legend, María de Jesús de Agreda was the first Spanish missionary to the Indian peoples of Texas, predating the Franciscans by almost one hundred years. According to historical record, she served as a major inspiration and catalyst for a missionary movement into the northern provinces of New Spain. In 1630, the custodio of the New Mexico missions, fray Alonso Benavides, informed the king of Spain and the Council of the Indies that God had marked the work of his Franciscan missionaries with special approval. Accounts had reached Benavides about a Franciscan nun, Agreda, living in Spain, who had traveled in spirit to the New World hundreds of times to instruct Indians in Christianity. Also recently, Indians to the east of New Mexico (later Texas) had approached his friars to request a mission for their people, telling of a “Lady in Blue” who had appeared in the sky and directed them to seek salvation from the missionaries. Benavides concluded that these events were miraculous.15

Nearly sixty years later, in 1689, when Spaniards pursued permanent settlement in the “land of the Tejas,” they recalled stories of Agreda’s prior visitations to the region and sought evidence of her that might serve as a touchstone for their own missionary efforts. Fray Damián Mazanet accompanied Alonso de León’s 1689 and 1690 expeditions to Caddo lands, and while military forces searched for signs of La Salle, Mazanet looked for indications of Agreda’s contact with the Caddos. Much to his delight, some Hasinais responded positively to his queries about her spiritual visits. Yes, he understood them to say, “they had been visited frequently by a very beautiful woman, who used to come down from the heights, dressed in blue garments, and that they wished to be like that woman.” This mysterious female figure had appeared among them, not in living memory, but in the past, as one caddí attested, according to stories told by his mother and other elders. To Mazanet, it was “easily to be seen” that the Caddo leader referred to Madre María de Jesús de Agreda.16

How fully did the Spanish missionary and the Hasinai caddí understand one another in this exchange? Certainly, Mazanet’s queries appeared to strike a chord; at the very least, the Hasinai leader heard the outlines of a story much like those told of one of his people’s own deities. One Hasinai creation myth, recorded by Franciscans two years after the caddí’s exchange with Mazanet, told of a woman in heaven who daily gave birth to the sun, moon, water, frost, snow, corn, thunder, and lightning. Another Caddo oral tradition, reported in 1763, told of a female goddess called Zacado who appeared to their ancestors to teach them how to survive in the world and then disappeared once they learned how to hunt, fish, build homes, and dress. Perhaps the Hasinais responded affirmatively to the familiarity of the missionary’s story of a spiritual apparition in female form who came to teach people how to live. Like Benavides, they too could have found the story of Zacado on the lips of a Spaniard to be a miracle.17

The iconography surrounding the Virgin Mary held even more crucial significance for initial Spanish-Caddo symbolic exchanges. To Spaniards, the Virgin’s image embodied who they were as a people, underscoring their religious identity as Catholics and their political and social identity as New World subjects of Spain. The Virgin served a multiplicity of roles as the patroness and protectress of the Church, the Franciscan order, the Franciscan colleges and missions of New Spain, New Spain itself, and all the people contained within it. More specifically in Texas, Spaniards proclaimed the Virgin—in her various manifestations as the Virgin of Guadalupe, Dolores, Luz, Refugio, Pilar, and Purísima Concepción—the source of spiritual guidance and protection for the members of all expeditions into the region during this period. In 1691, Domingo Terán de los Rios wrote that “the great power of our Lady of Guadalupe, the North Star and Protector of this undertaking, carried our weak efforts in this task to a successful ending.” Accompanying the Aguayo expedition in 1721, Juan Antonio de la Peña concluded his account with the declaration that “Our guiding light in this enterprise has been Our Lady of Pilar whom the governor selected as guide and patroness. As a shield on the Texas frontier he left this Tower of David so that she might protect it just as she had done when the Most Holy Virgin left her image and column of Non Plus Ultra at Zaragoza, which was then the edge of the known world of the Spanish people.”18

Spanish missionaries hoped that Our Lady of Pilar, whom they considered responsible for the conversion of old Spain, would work her old influence on the “edges” of New Spain as well. The Virgin Mary had earlier symbolized the conquest and conversion of non-Christian peoples during the Reconquest of Spain, when Spanish soldiers used her image to appropriate and transform mosques into churches. In the New World, the royal banner similarly flew as a sign of sovereignty over not only their encampments but also the territories they claimed in the name of the king. Yet, that message of conquest was not one meant for Indian observers but rather for rival Europeans who might otherwise challenge Spanish claims. When soldiers and missionaries marched into Caddo lands in the 1680s, the predominance of such banners also represented a shift in Spanish policy in response to the Crown’s 1573 Order for New Discoveries that prohibited violent conquest and instead promoted the “pacification” of Indian lands, with missionaries at the head of exploration and settlement. Though Franciscans in New Spain eschewed syncretism of the Virgin Mary and indigenous deities in the worship of their mission neophytes, they used her image to extend a promise of peace and protection to “the most remote people who have been discovered in America by the Spaniards.” When a Hasinai caddí inquired of a missionary the meaning of the sacred image on the Spanish altar, the Franciscan appealed to her identity as Christ’s mother and her intercessory role in the Catholic Church, characterizing her to the caddís as the “mother of help and of the religion of all human kind.”19

Spaniards displayed their religious icons to Indians because they believed there was no better image of peace (and, by extension, peaceful intent) than the cross and images of Christ, Mary, and the saints. In 1709, for instance, fray Espinosa used a cross fashioned out of paper and painted with ink as a calling card that was sent to the Hasinais when his expedition was unable to make it all the way to the eastern settlements. More important, though unaware of Caddos’ symbolic association of women with peace, Spaniards gave center stage to religious images of the Virgin Mary as their chosen sign of peaceful intent. The Virgin’s image was the focal point of Spanish self-presentation to Indians across the region—dominating as she did their rhetoric, prayers, banners, and rituals. Every Spanish expedition into Texas displayed the royal standard “bearing on one side the picture of Christ crucified, and on the other that of the Virgin of Guadalupe.” Each day, expedition leaders like Domingo Terán de los Rios chronicled their expeditions as the movements of “our royal standard and camp.” Routinely recording that “our royal standard went forward today,” Spanish officers and missionaries transformed the standard into a pronoun for themselves. Spaniards then took possession of lands by “fixing the royal standard” or leaving crosses as symbolic claims to territory. Spaniards also made Indians an audience to the regular performance of daily masses, processions, and celebrations of feast days in the Virgin’s honor before makeshift altars incorporating her image, thereby reinforcing the import of the Virgin’s presence within their expeditions.20

Fray Damián Mazanet, for example, took special care in planning the Spanish entry into one Hasinai village in 1690. “My opinion was,” he recorded, “that we four priests should go on foot, carrying our staffs, which bore a holy crucifix, and singing the Litany of Our Lady, and that a lay-brother who was with us should carry in front a picture on linen of the Blessed Virgin, bearing it high on his lance, after the fashion of a banner.” Mazanet further reported that the royal standard with its double picture of Christ and the Virgin of Guadalupe waved over the dedication of the first Tejas mission in 1690 during mass, a procession of the holy sacrament, the firing of a royal salute, and the singing of the Te Deum Laudamus in thanksgiving.21

In response to such declarations and ritual enactments, Indian peoples in Texas quickly came to associate Marian iconography symbolizing a powerful peacemaker specifically with Spaniards. The Virgin was not associated with Catholic Frenchmen (who until the mid-eighteenth century had few priests of their own in Louisiana, much less missionaries seeking to convert Indians). An episode related by French missionary Anastase Douay, one of the survivors of La Salle’s expedition, illustrates Caddo interpretations. Encountering a Hasinai man, Douay learned of the nearby presence of people who resembled Frenchmen and whom the man described by sketching “a painting that he had seen of a great lady, who was weeping because her son was upon a cross.” Much later, in the 1760s, fray José de Solís reported the still-powerful symbolic association of the Virgin with Spaniards. He told of a man from an Ais village (another Caddo band) who rejected the Spanish missionary’s preachings by asserting to Solís that “he loved and appreciated Misurí (who is the Devil), more than he did the Most Blessed among all those created, the Holy Mother Mary, Our Lady.”22

Image of the Virgin of Guadalupe printed on a pink silk banner, 1803. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Spaniards’ prominent display of the Virgin’s image did indeed succeed in giving signs of peaceful intent to Caddos, but not for reasons that Europeans would have understood. Caddos deemed Spaniards friendly because of the female, not the spiritual, embodiment of the figurative María. They, of course, did not understand Catholic iconography but instead translated it within the context of their own beliefs. Caddo responses indicate that they understood the Virgin’s image, not as a Spanish assertion of political identity or religious intent, but as an effort by Spaniards to compensate for their lack of real women and thereby to offset any appearance of hostility. Pierre Talon, one of the French youths from the La Salle expedition living among Caddos in 1690, described the initial appearance of Spanish expeditions while standing on the Hasinai side of the encounter: it was an overwhelmingly martial vision as men on horseback rode up “armed with muskets or small harquebuses, pistols, and swords and all wearing coats of mail or iron wire made like nets of very small links.” Though Talon did not make much of the banners emblazoned with a female figure, the Hasinai leaders did. In one of the earliest Spanish-Hasinai meetings, military commander Domingo Terán de los Rios reported what he believed to be the pacifying effect of the Virgin’s image on Caddos. He wrote that when faced with the difficult task of persuading the Hasinais of the sincerity of Spanish efforts to capture and punish the Spanish murderer of one of their people, he believed the Virgin “calmed and soothed” them, perhaps helping to communicate the expedition’s peaceful intentions in the face of such an act of violence.23

Most tellingly, Hasinais and other Indians directed customary renderings of welcome and honor to the figurative image of the Virgin Mary as they did to women of any visiting party. In the place of caresses reserved for real women, they might salute or kiss the standards bearing the Virgin’s image. Another native practice also incorporated her image. Indians normally put on display gifts received from allies in past ceremonial exchanges as a signal of welcome when those allies returned for later visits. When they extended similar gestures to Spanish visitors, objects carrying the image of the Virgin Mary were their choice for display. Time and again, Spanish missionaries wrote excitedly about Indians greeting them with images of the Virgin upon arrival at their villages. In 1709, as the Espinosa, Aguirre, and Olivares expedition approached a village of Yojuanes, a small group came forward in single file, led by a man carrying a cross made of bamboo, who was “followed by three other Indians, each one with an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, two of which were painted, and the other was an old engraving.” As they processed forward, they bowed and made other manifestations of peace toward the icons before approaching the Spaniards for customary embraces. The Indian men then formally requested that the Spanish representatives in turn go to meet the women of their village. Caddo leaders made even more direct their veneration of the female icon. When the Ramón expedition reached the Hasinai settlements in June of 1716, all the caddís and leading men came forward and kissed the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, “whom they all adored.” The Hasinais further honored the female presence of the Virgin by attending a mass presided over by her image. Missionaries later endeavored, unsuccessfully, to build upon what they saw as signs of native interest in Christianity; their failure to convert gave further proof that these gestures were indeed the Caddos’ efforts to recognize ceremonially a female presence among the Spaniards.24

Once both sides had established nonhostile intent, diplomatic protocols could get under way, calling upon each side to behave according to its customary, gendered notions of honor. For Caddos, initial meetings with foreigners involved only the establishing of acquaintance (alliance, trade, and relationships of any other kind were not yet being negotiated). At this point, they required primarily elite male leaders who stood for or embodied the community. Having vested authority in their leaders, Caddos established relations with other groups through these high-status individuals. Diplomatic rituals therefore linked together Caddo male elites with Spaniards and Frenchmen of analogous status in order to incorporate symbolically the foreigners into the Caddos’ ranked social systems—giving them the status and position required for interaction with the Caddo xinesí and caddís. Meanwhile, Europeans tried to ascertain which men represented the Caddo villages, and even more important, the confederacies, or “kingdoms,” and so had the authority to broker trade agreements and political alliances.25

With these goals in mind, both European and Caddo men spent much of their time in early meetings trying to read one another’s appearance, hospitality, and gift giving as indicators of status and power. Because Caddo ritual focused on linking together elite men from both sides of the cross-cultural encounter, efforts at communication reaped greatest success in contexts governed by rules of masculine conduct. The reception of foreign visitors offered a venue for conflated representations of national and male honor, especially when male elites vied to impress or outdo each other in display. The care Caddo men put into diplomatic ceremonies—reflected in the elaborate nature of feasts, dances, festivals, presentations of gifts, customary gala attire, and formal “harangues”—conveyed the significance of any invitation to share in such ritual. Congruence emerged between Spanish, French, and Caddo norms of masculinity when similar customs of militarized dress, displays of strength, and rituals of respect helped to enact public communications of honor between men. These shared bases of male honor facilitated good relations even if Spanish, French, and Caddo men did not grasp the nuances of each other’s behavior. As with the fortuitous misinterpretations of the Virgin Mary, in other words, each side appeared to conform to the other’s expectations of proper deportment toward fellow men, even while not fully understanding how and why.26

Caddo men greeted their European visitors with well-defined ceremonies to which like-minded Spanish and French men easily adapted because, coincidentally, they resembled their own. Europeans too came from worlds with long traditions of ceremony and rites of political, spiritual, and social meaning. Much in the rituals marking Hasinai diplomatic events resonated with French and Spanish men accustomed to civic and royal pageantry; the pomp of public entries, audiences, and departures; and the gift giving and banquets that surrounded the reception of foreign embassies and ambassadors. Caddo ceremony inspired fray Francisco Casañas de Jesús María to credit them with demonstrating “courtesies that Christians are accustomed to observe,” and he was particularly impressed with their deference to age. Twenty years later, fray Espinosa similarly asserted that Hasinais “most displayed their diplomatic policy in the embassies that they send to one another’s settlements.” Spaniards concluded from the formality of Caddo ceremony that any pledges given or taken would be strictly observed, while Frenchmen similarly read the ritual smoking of pipes (which they called “calumet” ceremonies) as a commitment of sincerity. From the symbolism inherent in many of these ceremonies, moreover, Europeans learned the protocols of respect due their native hosts. Arguing for the importance of these early meetings, one Spanish officer wrote that “much care is necessary, to the point that when the ways of the people are recognized, one arranges things to their taste.” By taking part in such rituals, Spaniards and Frenchmen communicated their respect for their Indian hosts and their awareness that they too must earn respect.27

For all these groups, civic and national displays of power took the form of male displays in military musters, oath swearings, and processions. Because of the times in which they lived, these European and Indian societies bound their concepts of political authority to military identity and ability. Growing challenges from expanding Apache and Osage bands over the eighteenth century were increasing the authority of war chiefs in relationship to the theocratic rule of the xinesí and the caddíswithin the Caddo chiefdoms. Tellingly, the status of amayxoyas (a category of warriors who earned the honorific title in recognition of valorous deeds and from among whom war chiefs were elected) appeared to be on the rise in response to these increasing tensions. Spanish, French, and Hasinai men established male honor through their deeds and accomplishments and expected public recognition of that honor through public ritual. In turn, for both Europeans and Indians, encounters with new groups required that men provide militarized displays and demonstrations of male prowess. Such rites determined the authority each brought to the following negotiations by establishing mutual, rather than hierarchical, honor and respect.28

At all stages of their journeys through Texas, Spanish officers thereby kept in mind the possibility of Indian surveillance and directed their expeditions to move in “military formation” to inspire the awe of onlookers. Although ceremonial formations and processions were a regular part of daily military life for the presidial forces, Spanish commanders clearly manipulated displays to achieve certain effects before Indian audiences. Concerned with their “mode of entry” to Hasinai settlements, commanders decided that a “good example would be set by having the priests and officers march in a procession,” followed by “all the cavalry, arms, munitions, and the necessary rear guard.” The retinue of supplies, munitions, and horses came last in the ranked orders. Such organized fanfare was not simply defensive but aimed to impress without antagonizing native groups targeted for diplomacy. The Hasinais met them with their own processions as caddís assembled their people, arranged them in the typical three files, and advanced to meet the Spaniards outside their villages.29

Next came the exchange of salutes. In the earliest meetings, Caddo men saluted by raising their arms and yelling in unison before approaching visiting Europeans. When survivors from La Salle’s party arrived at one Hasinai village in 1687, a dozen caddís and elders marched out in procession with warriors and youths “in the wings,” all wearing ceremonial dress. As soon as they drew near, Henri Joutel recorded, they all “raised their hands above their heads and came straight toward us uttering a certain unanimous howl.” By the 1710s, when French trade had increased the number of arms among Caddos, discharging guns replaced the yells as an imposing salute. In return, Spanish cavalry units discharged volleys, beat drums, and blew bugles. Both peoples endowed these exchanges of firepower with a dual purpose—as a literal “salute” of respectful greeting and as a figurative display of military strength. Fray Mazanet recorded that soldiers of the 1690 León expedition “had been given leave to fire as many salutes as they could during the procession, at the elevation, and at the close of mass.” The number of shots reinforced both the force and extent of the Spanish military power. Over time, greetings increased in intensity. As fray Francisco de Céliz described in 1718, “all the Indians came in marching order, firing their muskets with such precision that it seemed that they had been well disciplined in the militia; and as was noticed by all, the governor [Martín de Alarcón] was received with shots from more muskets than the said governor had on his side.” As early as 1718, then, Hasinais had closed the technological gap, and Spaniards found themselves outgunned. By 1721, the marqués de San Miguel de Aguayo felt compelled to bring out the big guns—quite literally—in order to outdo Caddo leaders. He divided his battalion into eight companies arranged in three files, placed cannons between them and fired three general salutes, and delightedly had his diarist record that the firing of the artillery and the companies’ volleys in concert had finally “created substantial wonder” among the watching Hasinai men.30

Once inside the Hasinai villages, both sides continued their displays of military presence and prowess unabated. Caddís stationed warriors as guards day and night as long as visitors remained present. Spanish expedition leaders similarly called officers and soldiers into military assembly to stand as an audience to ritual and rhetorical exchanges in the course of meetings. According to fray Espinosa, Hasinai men “do not yield a point in proving themselves warlike and valiant.” Guns only became available to the Caddos in the 1700s with the French trade, but because of trade with the Jumanos from the west, horses were well-established as a marker of male status by the time Europeans arrived in the 1680s, their value reflected by Caddo warriors’ choice to include their steeds among their prized burial goods at death. In later years, Caddo men thus chose their manner of display based upon their trade advantages in either guns or horses, Espinosa continued, and “make a show of wielding their guns with dexterity and racing their horses at great speed.” In the 1760s, a French traveler, Pierre Marie François de Pagès, related a strikingly similar performance by Hasinai men. In an encounter with a party on horseback, he recorded, Caddo men

were eager to display with much ostentation the swiftness and agility of their horses, as well as their own skill and dexterity in the art of riding; and it is but doing them justice to say, that the most noble and graceful object I have ever seen was one of those savages mounted and running at full speed. The broad Herculean trunk of his body, his gun leaning over the left arm, and his plaid or blanket thrown carelessly across his naked shoulders, and streaming in the wind, was such an appearance as I could only compare to some of the finest equestrian statues of antiquity.31

Responding in kind to such demonstrations, Spaniards mounted their own displays of armed cavalry performances to affirm their standing as formidable warriors and as men. In 1716, the Ramón expedition had to stop for a day of rest on their way to the Hasinai villages because cavalrymen—including Captain Ramón himself—had been racing and attempting stunts from horseback with such recklessness that several had suffered injurious falls. The 1721 expedition of the marqués de Aguayo, of all the Spanish entradas to Caddo lands, was the one most designed to impart Spanish power, with its five hundred men marching in eight companies. Expedition diarist Juan Antonio de la Peña recorded that the size of the army—as well as the train of cargo and livestock—did appear to impress Hasinai leaders. Beginning with meetings with a caddí named Cheocas, who was known to have a “great following,” and at each subsequent meeting with different Caddo groups, Aguayo repeated a scenario of putting his troops through their paces and having them pass in formal review before Caddo leaders and warriors.32

Orchestrated display shifted to the individual level when Caddos and Europeans had to identify elites. Spaniards, Frenchmen, and Hasinais based initial impressions on appearance, so dress and adornment held considerable importance. Using dress as a marker of identity was not always so simple, however. Europeans recorded instances when they failed to recognize Caddos at all, mistaking them because of clothing and manner as either French or Spanish. Henri Joutel made such an error in perception in 1687. One afternoon, he explained,

we saw three men, one of whom was on horseback. They were coming from the direction of the Cenis’ village and consequently straight to us. When they came close, I noticed that one was dressed in the Spanish manner, wearing a short jacket or doublet, the body of which was blue with white sleeves as if embroidered on a kind of fustian; he was wearing small, tight breeches, white stockings, woolen garters, and a Spanish hat that was broad and flat in shape. His hair was long, straight, and black, and he had a swarthy face. I therefore did not have much difficulty persuading myself that he was a Spaniard.

Joutel did not realize his mistake until the man responded to his attempts to speak “in a broken Spanish or Italian” by saying “Coussiqua,” which Joutel understood to be a Hasinai expression for “I have none of it,” or “I don’t understand it.”33

Indians too used dress and appearance to distinguish among foreigners, whether European or native. The vast array of different hair styles, clothing, tattoos, and body paint of Indian peoples in the region, noted carefully by Europeans, testified to the importance of distinct markers of identity. Yojuanes, Simonos, and Tusonibis told fray Espinosa that they recognized Spaniards by the red waistcoat worn by one of the officers. In interactions with Frenchmen, Hasinais referred to Spaniards by “depicting” their clothing. Similarly, Paloma Indians, perhaps trying to smooth over an unintended offense, once assured Frenchmen that they “did not look like Spaniards.” Not surprisingly, but much to the consternation of Europeans, however, Indians in the early period of contact often could not differentiate between Frenchmen and Spaniards. Since they used clothing as identity markers, they found Europeans much alike. The marqués de Aguayo explained to Viceroy Casafuerte that because “the Indians of all those nations [in the Texas province] do not distinguish between us,” they sometimes called both Spaniards and Frenchmen by the same term.34

European and Indian societies nevertheless similarly invested dress with significations of individual honor as well as social, political, and military rank, and so clothing emerged as a useful means of communication. Caddos reserved “gala attire” particularly for diplomatic feasts and celebrations in which “neither the men nor the women lack articles of adornment for their festivities.” “When the day arrives,” described fray Espinosa, “they get out all the best woolen clothing they have, which they reserve for this purpose, along with very soft chamois edged with little white beads, some very black chamois covered with the same beads, bracelets, and necklaces, which they wear only on this and other feast days.” Because these ceremonies revealed each person’s contributions to society and highlighted social and political authority and rank, dress took on significance as a symbolic extension of that status.35

In addition to the swords, clubs, and later guns carried by leading warriors as emblematic of their elite rank, European observers remarked that dress was an arena of particular male display and subsequently laid great import upon it in judging character. To Alonso de León, for instance, a Hasinai caddí he met was clearly a man of ability, because his appearance and comportment outweighed his “barbarian” identity. Jean Cavelier, La Salle’s brother, judged Hasinais to be the “most polished” of Indians based on appearance, arguing that “From the layout of their village and the style of their houses, from the cloth of bird feathers and hair of animals, they seem to be more intelligent and more clever than all the other nations we met.”36

What was so remarkable about the dress and decor of Caddo men? Hasinai men especially, explained fray Francisco Casañas de Jesús María, “pride themselves on coming out as gallants,” and some costumes were “of so hideous a form that they look like demons,” since some “go so far as to put deer horns on their heads.” Men displayed rank and occupation by choosing among elaborately decorated bison skins, feathers, jewelry, and battle trophies. Henri Joutel wrote that, when all the elders of one Hasinai community came out to greet French visitors, they appeared

dressed in their finery which consisted of some dressed skins in several colors which they wore across their shoulders like scarves and also wore as skirts. On their heads, they wore a few clusters of feathers fashioned like turbans, also painted different colors. Seven or eight of them had sword blades with clusters of feathers on the hilt. . . . they also had several large bells which made a noise like a mule bell. With regard to arms, some Indians carried their bows with a few arrows, while others carried tomahawks and had smeared their faces, some with black and others with white and red.

Painting their faces with vermilion (red pigment) and bear’s grease made their faces red and slick, according to Spanish observers. Feathers served as particular signs of prestige for men. Fray Espinosa wrote that “when they see the feathers of the chickens from Spain which we raise they do not stop until they have collected the prettiest colored ones,” saving them “to wear at their brightest.” Among the spiritual elites, feathers marked the personal insignia and ritual tools of Hasinai shamans, a predominantly, but not exclusively, male group. And at the highest level of all, as fray Espinosa described it, were the chests in the house of the cononicis (revered child spirits who acted as intermediaries between the xinesí and the Supreme Being, Ayo-Caddí-Aymay), which were filled with “many feathers of all sizes and colors, handfuls of wild turkey feathers, a white breast knot, some bundles of feather ornaments, crowns made of skins and feathers, and a headdress of the same”—all to be used by the xinesí in domestic and diplomatic rituals.37

Spanish and French men accurately assessed markers of Caddo male status when it came to warrior strength and valor (observations that Caddo male display often left little room to doubt). “In appearance,” fray Espinosa wrote of Hasinai men, “they are well built, burly, agile, and strong; always ready for war expeditions and of great courage.” Domingo Terán de los Rios similarly assumed Hasinai appearance to be indicative of warrior demeanor, because after watching their movements and expressions, he “concluded that [Hasinai men] were very brave, haughty and numerous.” Describing a ceremony he compared to a knighting, Frenchman Henri Joutel recognized the significance of clothing to a Hasinai male youth’s assumption of adult male position and status. Once a young man reached the age of becoming a warrior, he recorded, elders assembled an outfit and equipage for him, consisting of a garment made of tanned hide and a bow, quiver, and arrows over which was chanted a blessing. Tattoos also offered a visible record of male status and honor. Adult men’s body decorations focused on “Figures of living creatures, like birds and animals,” to reflect their role as hunters. Martial images depicted individual accomplishments in war. Hasinai warriors further carried as “arms and banners” the skins and scalps of defeated enemies. According to fray Francisco Hidalgo, they “wear the scalps of their enemies at their belts as trophies and hang them from reeds at the entry to their doors as signs of triumph.” Displays conveyed rank among men as well, when entire hanging heads and skulls marked the residence of the grand xinesí—trophies brought him by the warriors he commanded.38

Spanish and French officers and soldiers sought to impress Caddo men too with an appearance of courage and strength to win respect that could later be built upon to forge trust and alliance. Of first importance to Europeans was communicating to Indians that they met as equals and that it was not in the Indians’ interest to fight them. Europeans wished to convey that they were there as representatives of nations capable of offering military aid and alliance. The composition of the earliest expeditionary forces reinforced their efforts to appear powerful. With missionaries, officers, soldiers, and traders the sole members of the initial groups visiting Caddo lands, Spaniards and Frenchmen could not help but communicate a primarily militarized image of male strength. Officers and soldiers always dressed in full regalia, sporting military coats and hats, chain mail, and an assortment of armaments. One Spanish expedition leader delayed the departure of his forces for over a month while awaiting the delivery of new uniforms for the soldiers.39

If Caddos used their own theocratic hierarchies of male leadership to aid them in discerning the ranks among Spanish and French men, however, they likely concluded that no one within the visiting parties occupied the elite level of their xinesí or perhaps even their caddís. A xinesí was both a religious and a political leader, who did not hunt because his household was supported through gifts of food and meat from the surrounding communities; in fact, fray Casañas explained that “all of the Indians give him portions of what they have so as to dress and clothe him.” He maintained perpetually the sacred fire at the temple complex and mediated between the spiritual and human worlds. In turn, this mediation informed the guidance he offered the caddís and canahas as they assembled to make decisions about the welfare of their communities. Thus, the xinesí’s complex functioned as the center of both spiritual and political power, uniting the surrounding communities. Neither xinesí nor caddís carried weapons to mark their status, because although they held authority in military decisions, they were not warriors or war chiefs (a different political category with different symbols). Spanish military commanders, in contrast, did wear their arms as emblems of rank, and though their authority over soldiers was clear, by such appearance they were most analogous in standing to the Caddo war chiefs. The separation of religious and military leaders within Spanish expeditions and the subordinate status of missionaries to military commanders further prevented any association of the spiritual vocation of missionaries with that of the xinesís, leaving them analogous in rank to the connas (shaman priests) among the lower orders of Caddo nongoverning elites. During diplomatic meetings with Spaniards, then, caddís might oversee the rituals and ceremonies, but Spanish commanders and missionaries primarily shared status with the lower orders of governing and nongoverning elites—canahas, amayxoyas, and connas.40

After sussing out personal appearance and rank, rules of male precedence ordered Caddo hospitality customs of pipe-smoking and the seating, housing, and feeding of guests. Spaniards observed that each Hasinai household set aside a special seat for only the caddí to use when he visited, and that offers of hospitality served as payments of respect to leaders. In the caddís’ households, fray Mazanet and fray Casañas quickly learned not to approach, much less sit upon, a particular wooden bench in front of the fire; to do so constituted a breach of etiquette that might result in supernatural death because the seats were reserved for the xinesí alone. At a nonelite home that Terán de los Rios visited in the company of a caddí, the military commander noted that the caddí was offered a seat as soon as he crossed the threshold, “deference” that was shown to no others in the party. Caddos also provided leaders with special feasts, and rituals required the people of each household to present caddís and the xinesí with food and supplies on a regular basis. In public ceremonies, seating arrangements and orders of ritual always affirmed rank and prestige among the Hasinais.

Just as Caddos showed deference to their leaders, shamans, and caddís in civil ceremonies, so in turn did they reserve markers of prestige for respected visitors, seeking to unite host and guest in bonds of shared honor. Spaniards and Frenchmen recorded with appreciation that ritualized gestures and privileges that leading Caddo men and principal warriors enjoyed were ceremonially extended to their own leaders. At each visit, for instance, Hasinais accorded missionaries and officers the honor of staying within a caddí’s residential complex. At meetings, Hasinai leaders orchestrated the design and arrangement of seats to reaffirm and accord honor. Carpets of mats and blankets, roofs of tree boughs, and benches covered with bison skins decorated reception areas. Juan Bautista Chapa described the special benches brought forward by Hasinais when the León expedition first visited in 1689 and again in 1690 as a “civility that greatly surprised our troops.” The importance of such rituals was clearly borne home to Europeans, as evidenced by their efforts to match such hospitality when Caddos visited Spanish encampments away from their villages. When Spanish officers found themselves in the position of host, they carefully imitated Caddo custom in setting up similar housing and seating arrangements commensurate with the rank and status of the various members of the visiting group. As Captain Domingo Ramón made his first approach toward the Caddo villages in 1716, he knew that a welcoming party would be sent out to greet him, so he had his men build a structure of tree branches covered with blankets, with all the packsaddles available arranged around to serve as seats to allow him to greet Hasinai leaders in the appropriate fashion.41

The housing of visiting dignitaries held particular significance, indicating their honorary but probationary status within Hasinai settlements. Military commanders and missionaries thus found themselves housed in caddís’ ceremonial compounds, where “there was room for all,” explained one caddí to fray Mazanet. And room there was. Located near the geographic center of each Caddo community, but separated from the surrounding hamlets and farmsteads, the complex included the caddí’s residence, a building for public gatherings, and a residential building to house canahas when called into meetings by the caddí, all three built around a central plaza with a cane-covered arbor nearby—a two- to three-acre site altogether. The residence itself was the largest of the three—a circular pole-framed house with a thatched grass roof twenty varas in height (fifty-five feet), within which the focal point was a hearth fire “fed by four logs forming a cross oriented to the cardinal directions” and lit by embers brought from the sacred fire at the xinesí’s temple complex. “Ranged around one-half of the house, inside, are ten beds, which consist of a rug made of reeds, laid on four forked sticks,” described Mazanet. “Over the rug they spread buffalo skins, on which they sleep. At the head and foot of the bed is attached another carpet forming a sort of arch, which, lined with a very brilliantly colored piece of reed matting, makes what bears some resemblance to a very pretty alcove.” The other half of the house provided shelves upon shelves of storage as well as working areas for the ten women who oversaw the day-to-day functioning of the compound and prepared the feasts offered as part of the caddí’s hospitality. “Skillfully fashioned” wooden benches brought out into a patio fronting the plaza served as the dining area for guests.42

Visiting European and native diplomats became temporary residents of the compound like canahas, the ranking elders who left their own homes to take up temporary residence in the building designated for them when caddís called them to council duty. Both groups of men, whether domestic or foreign, were recognized as men of standing—secondary to caddís—who gathered at this site to take part in public ceremonies and rituals. Yet, the temporary housing of European visitors reflected not just the official nature of their visit but also their separation from the surrounding community. As George Sabo explains, “rituals performed in temples or at ceremonial centers emphasized the hierarchical priority of leaders as representatives of their communities,” thus distinguishing them as discrete from the rituals performed in individual houses throughout the Caddo community that reflected kinship, clan membership, and the matrilineages of those homesteads. To house (and confine) visitors at the caddí’s compound emphasized their standing as men of rank while at the same time keeping them distant from the Caddo community itself. The Caddos’ response to Spanish leaders who failed to abide by the rules indicates how important this separation was. Commander Domingo Terán de los Rios, for instance, managed to offend more than one caddí during his 1691 travels through Hasinai territory. One leader, who quickly developed hostile relations with Spaniards, never opened his home to Terán, leaving him to remain in the camp his men had pitched at a distance from the Hasinai villages. When the expedition moved on to another village, the caddí there offered his house as shelter to the military commander because of the bad weather but was displeased when Terán left the compound, “displeasure” that necessitated Terán’s hasty return to the complex. Telling as well, when the two men together visited another village across the river the next day, Terán noted that only the caddí was offered a seat by their host.43

When Europeans learned and obeyed the rules governing visits to Hasinai villages, they then participated in other ceremonies that reinforced shared male honors and prestige. Smoking ceremonial, or “calumet,” pipes—usually made of stone (but later sometimes brass), with a stem more than one vara (2¾ feet) in length, with numerous white feathers attached from one end of the stem to the other—held a central place in publicly joining together Caddo and European men of stature. Spanish officials interpreted the mixing of Caddo and European tobacco and the shared smoking of a pipe as signaling friendship, a “unity of their wills,” and mutual “compliments.” In French observances, the singing or chanting of the calumet similarly translated as a “mark of alliance” or promise of “good union.” While everyone in a Caddo community took part in the ceremony—reflecting the Caddo presumption that everyone had an investment in the union and spirit represented by the ritual—the order of smoking itself reconfirmed the position and power of governing male elites. The caddí prepared the tobacco on a “curious and elaborately painted deerskin,” lit the pipe, and blew the first smoke, before passing the pipe to their leading warriors, then to guests of analogous prominence, and eventually to all others. Although Caddo women and children took part in pipe ceremonies, they did not actually smoke the pipe, and the performance of the smoking ceremony aimed primarily at validating the honor and position of Caddo and European male leaders.44

Once status was clearly established, European men had to go through purification rituals that would admit them into Caddo male ranks, a diplomatic formality necessary before any kind of negotiation for trade or alliance could begin. Washing was one form of purification for strangers, as when some Caddos brought water and cleaned Henri Tonti’s face with such care that he concluded it must be a particular ceremony among them. Henri Joutel wrote that they actually wanted to bathe the Frenchmen entirely, but because of their unfamiliar clothing, elders chose only to apply fresh water to the visitors’ brows. Perhaps to make up for that limitation, one Caddo village farther north in present-day Arkansas made abbé Jean Cavelier part of a far more elaborate transformation or adoption ceremony. There, village leaders identified Cavelier as the “chief” of the party, to be honored in a calumet ceremony—reinforcing the impression that the Caddos had difficulty discerning leaders of equivalent status to their own. Elders accompanied by young men and women sang before the dwelling where Cavelier and other Frenchmen were housed, then led Cavelier outside to a prepared location, put a large handful of grass under his feet while two others brought out an earthen dish filled with clear water with which they washed his face. After this cleansing, he found himself seated on a specially prepared bison skin with a calumet pipe laid before him on a dressed bison skin and white deerskin, which were stretched over three forked pieces of wood, all dyed red. Surrounded by elders and men and women singing and shaking gourd rattles, a Caddo man stood directly behind Cavelier to support him and made him “rock and swing from side to side in rhythm with the choir.” Worse still from Cavelier’s perspective, two young women then came forward with a necklace and an otter skin to be placed on either side of the calumet and, with matching symmetry, placed themselves on either side of the Frenchman, facing one another with their legs extended forward and intertwined so that Cavelier’s legs could then be arranged across theirs. The ceremony wound on until Cavelier—reeling with exhausted embarrassment “to see himself in this position between the two girls”—signaled to his French companions (who were highly amused by his predicament) to extract him. The smoking of the pipe had to await the morning and the recovery of Cavelier’s dignity.45

Spanish expedition leader Martín de Alarcón’s experience in 1718 further illustrates the ritual elaborations by which Caddos consecrated foreign men of stature as dignitaries. As soon as Alarcón arrived in one Hasinai village, men came forward to take him from his horse, a caddí removed his sword and guns, and two warriors picked him up, one by the shoulders and the other by the feet, and carried him to the door of the house where he was to stay. Standing him on his feet, “they washed his face and hands gently and dried them with a cloth.” Again picking him up, they carried him inside and placed him on a special bench alongside several caddís with whom he “reciprocally performed” a pipe ceremony. Only after this ceremonial cleansing, followed by presentation into the company of Caddo leaders, did Caddo men formally “give him to understand how greatly they enjoyed his coming.” Smoking a pipe as well as washing thus appeared to be part of the induction rituals.46

Spanish and French officers sometimes received titles reflecting their new status among Caddos as diplomats and traders. At the close of purification rituals for Alarcón, one group of Hasinais declared that “they received him as their chief,” while another chose to address him as “Cadi A Ymat.” Observing the rituals as they took place, fray Espinosa, who had been living among Caddos for three years, explained that “this is the ceremony with which they declare someone a capitán general among them.” Hasinai leaders meant these titles to confer symbolic inclusion or membership among a community of leading men and warriors. Europeans appreciated but often did not fully understand this honor. Time and again, Europeans conflated titles conferred on them with the authority held by caddís, failing because of language barriers or ego to recognize the complexities of Caddo leadership hierarchies and their own subordinate status within them. Spaniards in particular often hoped that such ceremonies indicated Caddo acceptance of nominal Spanish rule—quite a leap of imagination in the absence of military conquest. Without being aware of European flights of fancy, however, Caddos used such titles to their own advantage. In response to French trader Jean Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe’s proposal to establish a trading post in their village, a Caddo band of Nasonis rewarded the Frenchman with a title of “calumet chief.” He soon discovered to his dismay that the title came with more obligations than privileges. In recognition of his newly conferred position—a position demanding displays of “chiefly” largesse and generosity—Nasoni leaders called upon him to supply them with gifts rather than simply the trade he had come seeking.47

To accompany such titles, Caddo leaders also presented Spanish and French men with dress and insignia reflecting native male rank and honor. After Jean Cavelier’s purification in Arkansas, Caddo elders tied up his hair and placed a dyed feather at the back of his head and, following the completion of the smoking ceremony, gathered the pipe and the red-dyed sticks upon which it had rested into a deerskin pouch and presented it to Cavelier as a token of peace, which he could use as a passport to other Caddo villages. Caddís placed on the head of Martín de Alarcón “some feathers from the breasts of white ducks and on his forehead a strip of black cloth which fell to his cheeks.” At about the same time that Alarcón was with the Hasinais, Bénard de la Harpe had moved on from the Nasoni villages to those of allied Wichita bands, where he received a grand reception. A Tawakoni chief recognized him by giving him “a crown of eagle feathers, decorated with small birds of all colors, with two Calumet feathers, one for war and the other for peace, the most respectable present that these warriors may give.” Ritual exchange continued the next day when the warriors painted Bénard de la Harpe’s face ultramarine blue and presented him with many bison robes. In the three ceremonies, feathers, which Europeans had noted to be signifiers of elite male status, appeared as a central decoration in the insignia offered foreign dignitaries.48

Once visiting leaders had been inducted into Caddo ranks, the entire community then welcomed them, and here women took center stage to emphasize the newcomers’ inclusion. Whether Spanish and French expeditions encountered Caddos along the roads or within villages, feasts and food items were always part of what Europeans understood as native “gifts” of hospitality. Away from villages, food was a key feature in the Caddos’ welcome committee greetings. When ninety-six Hasinais met the Ramón expedition several leagues outside of their villages in 1716, “gifts of ears of green corn, tamales, and beans cooked with corn and nuts” followed quickly upon the smoking of the calumet pipe at the impromptu feasting site. Once meetings moved to the more formal complexes of the caddís, women’s prominence in hosting the rituals clearly reflected that the bounty of feasts rested upon their successful direction of agricultural cultivation within the community. Fray Francisco de Céliz recorded that Caddo women “came from all the houses, offering their baskets of meal and other edible things . . . which was all that they had at that time.” As women brought ears of green corn, watermelon, beans, and tamales for the feasts, each woman designated for expedition leaders “a small gift of the food that they themselves eat.” Thus, domestic economies intertwined with political diplomacy to accord women (and the matrilineal households they represented) a place of honor in hospitality ceremonies. Nevertheless, European visitors remained within ceremonial compounds to which each household’s contribution was brought; they were not yet invited into the community itself.49

The honors implicit in Caddo leaders’ demonstrations of hospitality obligated a reciprocal “favor” from their Spanish and French guests, generally in the form of diplomatic gifts. Each side interpreted gift giving according to their own gendered view of what was necessary to maintain order. Gifts answered the debt incurred by partaking of the bounty of the caddís’ villages. As Bénard de la Harpe recorded, whenever a group honored him with the calumet ceremony, it “obliged” or “induced” him to reciprocate with gifts. Gift giving, hospitality, and reciprocity figured prominently in Spanish and French culture as well, rooted in ideals of the obligations of public and familial patriarchs, and were basic to European male honor. So gift giving was another custom that could promote cross-cultural communication while, yet again, not being fully understood by either side. Every expedition sent by the Spanish Crown to visit Indian nations carried with it “the stock and the supplies designated for use in gaining the friendship of the Indians and winning their affections.” While European representatives sought to impress with shows of generosity and the material benefits of their nations, however, Hasinais and other Caddo peoples accepted and interpreted these gifts according to their own definitions and beliefs regarding political courtesy.50

Just as Caddos showed deference and honor to their xinesí by giving items of value, and just as they exchanged similar items with neighboring Caddo allies, they also recognized European gifts as marks of honor, but not in quite the way Europeans expected. Caddís controlled all European gifts, as it was through their authority that items were redistributed to all others in Caddo communities. Bénard de la Harpe noted that when various Caddo bands celebrated the calumet, they “cast off all the clothes that they might have on” to give to others. Fray Francisco Hidalgo similarly remarked that despite Hasinais’ love of clothes, “what His Majesty has given them has been of but little use to them because they immediately divide it with their friends.” When Hasinai women piled foodstuffs at the center of an assembly of Caddo leaders and representatives of the Ramón expedition, Captain Ramón ordered an analogous stack of one hundred yards of cloth, forty blankets, thirty hats, and twelve packages of tobacco to be furnished for the Hasinai leaders to divide among their assembled peoples. The Spanish commander noted that once all had been distributed by the principal leaders, they had nothing for themselves—and “they were as happy as if they had received all of the goods themselves.” “Happy,” perhaps, because giving away, rather than amassing, wealth was how they established and reinforced their right to be honored and listened to by the rest of the community. In this way, they expanded the honor of the gifts to the entire community while at the same time reinforcing their own authority and the deference reserved for Caddo leadership.51