Chapter Two

Political Kinship through Settlement and Marriage

In the 1680s and 1690s, Caddoan greeting ceremonies had welcomed, purified, and honored Europeans; rituals had remained public in scope; and exchanges had been those of elite men who were deemed, during the course of meetings, to be within the ranks of the Caddo leaders who greeted them. Caddo conventions of interaction shifted, however, when relations moved beyond initial visits to political and economic alliance. Simply put, when European peoples expressed interest in living permanently in or near Caddo settlements, the rules shifted to a different arena of Caddo politics. Between 1700 and 1730, handfuls of Europeans came and went from Caddo lands as two very small populations, one Spanish and the other French, established a long-term presence there. Throughout that time period, there was no question of who held the power to determine the terms by which the two groups would remain in the region—that power resided in the hands of Caddoan leaders and their people.

In order for Caddoan peoples to broker permanent relationships with Europeans, they had to incorporate the strangers as “kin.” At that point, the kinship system structuring Caddo society came into play, and the locus of interaction expanded to include that of individual, family, and household. Moreover, because that kinship system was matrilineal, except at the highest levels of leadership, relations grew beyond those of only the elite men who made up leadership ranks and began to involve Caddo women. Matrilineal kinship defined the basic social unit of Caddo communities and also relations of production, trade, and diplomatic alliance. Marriage and kinship thus functioned as a “meta-institution” that “underpinned the organization of economics, politics, religion” among Caddoan peoples. Principles of dual realms, or “paired categories or contrast sets,” structured not only the symbolism of rituals, cosmological beliefs, and mytho-historical traditions but also kinship and clan organization and the spatial relationship of individual homesteads and ceremonial centers. These contrasting pairs included order/chaos, phenomenal (human)/numinous (spiritual), inside/outside, junior/senior, and male/female. In turn, “the well-being of the human community depended on the maintenance of positive (orderly) relationships between the two realms.” These dual realms would necessarily help to determine the relationships Caddos formed with Europeans.1

The Europeans who bid for permanent residence among Caddoan peoples would be evaluated as individuals or families rather than as representatives of foreign nations, because each would assume a place in the order of the Caddos’ world. Caddo leaders’ demands that Spaniards bring women with them to Caddo lands did not simply reflect a desire to protect Caddo women from abuse. It also meant that they expected those who settled among them and became part of Caddo societies to be properly equipped to contribute to those societies. All members of expedition—now settlement—parties fell under the Caddos’ scrutiny, and the focus also tightened on individual leaders who in initial contact situations had been identified as men of like rank with Caddo leading men. Would they be true to the pacts agreed to in those early meetings, and could they sustain their people’s commitment to the mutual obligations of those pacts? In the Caddos’ eyes, those leaders who visited only briefly and then departed had far less significance than those who remained to live in Caddo territory. If the settlers or traders who proposed to live among Caddos were predominantly single men (and among both Spaniards and Frenchmen, they were), they had to be given some kind of kinship affiliation. The easiest way to accomplish that was through marriage. Thus, at this stage, Caddos put their association of women with peace to work politically through their kinship practices.

Spanish and French imperial goals of settlement reinforced the Caddoan locus of negotiation on the household, since French agents pursued relations primarily with individual hunters and traders, while Spanish missionaries focused their efforts of conversion on individuals and their families. As well, whether or not they fully realized it, Spaniards and Frenchmen used the gender identity of women to resolve the fine lines between expressing peace rather than hostility, and strength rather than aggression in their relations with Caddos. For the predominantly male European groups who moved into Caddo territory, women represented the key element needed to solidify relationships with Caddoan peoples. Settlement and marriage served as demonstrable acts of commitment. The presence of wives and the children they bore signaled European men’s ties to a location and their determination to settle, maintain, and defend it. That tie in turn helped ensure alliance. Women might also bind men to one another through the kinship relations formed in marriage. Intermarriage established a permanent basis for relationships that informed economic and political behaviors outside the familial and social domain of the relationship itself. It linked peoples as well as families together in networks of interaction and reciprocity.

Yet, different French and Spanish diplomatic strategies distinguished the ways in which each group was willing to integrate itself into the kinship-based organization demanded by Caddos. Spaniards’ mission-presidio diplomacy, though seemingly offering a kind of joint settlement and alliance, envisioned and demanded fundamental changes of their Caddo allies and did not allow their different socioeconomic and political visions to be ignored. Frenchmen, on the other hand, shared many compatible habits with Caddos when it came to family-based settlement and alliance, because it served their purposes of trade. As will be seen, Frenchmen established the province of Louisiana for purposes of commerce, which tied locales of French settlement closely to Caddos and other native trading partners. The gender relations of marriage in turn provided Frenchmen with immediate entry into Caddo social and economic networks. Frenchmen’s unions with Caddo women made real the fictive kin relationships forged by trade in hides, horses, and captive women. Through intermarriage, Frenchmen regularly entered Caddo systems of bride service with their attendant designations of sociopolitical honor and status. In the act of seeking wives, French traders and officials unknowingly deferred to Caddo custom and presented themselves to be ranked as men by Indian families and leaders. Ties of settlement, marriage, and trade provided untold diplomatic and economic advantages to the Frenchmen of western Louisiana as they competed with the Spaniards in Texas for the loyalty of powerful Caddo allies.

Meanwhile, Spaniards struggled to redeem themselves, seeking ways to erase memories of the violation of Caddo women and to build new relations focused around six mission and two presidio communities scattered among Caddo hamlets. It quickly became clear, however, that Caddo and Spanish ideas about the relationship between their communities diverged considerably. Both wanted the other as an ally, but Caddos sought to achieve that end by making Spaniards into kin through trade and marriage, while Spanish officers and missionaries envisioned Christian conversion as the means to achieve the “civilization” of Caddos. Both wanted to convert the other. At the heart of missionary goals lay the requirement that converted Indians become members of Spanish society, but the reverse was unthinkable—that Spaniards might enter Caddo society and live by their terms. Thus, both Caddo and Spanish leaders failed in their initial designs. The Hasinai Caddos’ rejection of Spanish mission projects in their lands and the Spanish rejection of any notion of intermarriage as a political tool in relations with “heathen” Caddos soon became clear. Spanish and Caddo emphases then gradually reoriented to affirming the common needs and ties of their neighboring civil settlements, especially as families increasingly made up the Spanish population in the region and the presence of Spanish women and children stabilized relations. Only then did Spaniards find a route, different from that of Frenchmen, into the realms of Caddo acceptance and extended-kinship status.

In order to more fully understand the Caddos’ perspectives that informed their relations with Spaniards in the early 1700s, it is instructive to look at French experiences in the land of the Tejas, in a sense looking down the road not taken by Spaniards. In the stories of Frenchmen may be seen the Caddos’ designs for relating to other peoples and nations through kinship—designs that did not work with Spaniards. Spanish officials and missionaries spent much of their time bemoaning the success of their French competitors, and thus the Caddos’ relationships with Frenchmen provide an illuminating context within which to explore comparative Spanish failures. To do so, we must first flash back to the 1680s when the handful of survivors and deserters from La Salle’s expedition found homes and families in Caddo villages. Just as the earliest contacts between Spaniards and Hasinais presaged the difficulties Spaniards would have in later years, so too did the experiences of French deserters foreshadow the better fit French cultural categories would have with Caddo polities. Though these Frenchmen did not, in the end, remain among Caddos permanently (four of them stayed four years), their experiences as recorded in the journal of Henri Joutel and in the interrogations of Pierre Talon offer detailed accounting of Caddo customs of inclusion via kinship.

A few months before the deserters and survivors first took up residence in Caddo lands in 1687, La Salle had left ten-year-old Pierre Talon to live among the Hasinais, hoping that the boy would learn their language and be able to act as translator for the Frenchmen. La Salle also may have intended to make a political gesture to the Caddos, since French experience had shown that some native societies exchanged children as a way of strengthening alliances. Indeed, ceremonial traditions among Caddoan peoples indicate that they may have exchanged children with other bands, each adopting the other’s children into their communities in reflection of a political alliance. In a “Baby Dance” practiced by twentieth-century Wichitas (relatives of the Caddos), participants dress a boy and a girl from another native group in Wichita clothing and symbolically adopt them as Wichitas in a ceremony, thus making the birth and adoptive parents ritual friends. Such practices suggest that Caddos may well have viewed La Salle’s actions in leaving Pierre with them as a signal of his wish for long-term relations of peace.2

Talon lived among the Hasinais for three years before the León expedition captured him and another French youth, Pierre Meunier, in 1691. Pierre Talon and his brother Jean Baptiste, who was found living among Karankawas along the coast, eventually testified before Spanish and later French officials about those experiences. In turn, the Talons would play a significant part in Frenchmen’s return into the good graces of Caddo leaders in the 1710s. Information gained from French officials’ interrogations of the two Talon boys convinced Louis de Pontchartrain and Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville that the boys could serve as passports into the Caddos’ realm. The Talon brothers accompanied d’Iberville’s second expedition to Louisiana in 1699, when the region was officially claimed as a province for France, and d’Iberville most likely sent them with his brother, Jean Baptiste Le Moyne Bienville, to explore trade possibilities among Caddos in 1701 (one of the first priorities of the officials of the new province). The brothers assuredly played a role in introducing Louis Juchereau de St. Denis, the founder of the first French trading post in Caddo lands, to Hasinai and Natchitoches peoples in 1714.3

In the thirteen years that had passed since Pierre Talon’s childhood years among the Hasinais, he had lost much of what had been his “perfect” knowledge of the Caddo language—though we may speculate that some of it surely returned once he was back among the people who had cared for him during a critical period of his youth. He had certainly cared for them, since he had tried so hard to resist the Spaniards who took him from his Caddo home back then: when word had come to the Hasinai village of the approach of the Spaniards in 1690, Talon and Meunier had tried unsuccessfully to flee to a nearby Tonkawa settlement in hopes of eluding capture, but Spanish troops discovered them en route. When Pierre Talon returned to the Caddos in the 1710s, he greeted them with the sign language that they had taught him. Perhaps more important, his tattoos identified the grown man as the boy they had adopted so many years before. Though French officials valued Pierre’s knowledge of the geography and the language, to Caddos, Pierre’s identity as kin—adoption having made him a Caddo—was crucial. By sending Pierre back to the Hasinai villages, French officials returned to them a lost son taken away by the Spaniards.4

Pierre’s earlier testimony about Caddoan peoples had illuminated the importance of kinship within the Caddos’ world. Pierre described the setting in which the boys found themselves among “the most gentle and the most civil of all the nations,” with settlements “divided into families” that lived in clusters reflecting the clan divisions, each with its own fields. Moreover, the ties formed through kinship meant that the “people of the same nation live among themselves in a marvelous union.” A caddí had chosen to adopt Talon, and the boy spent all his time at the side of him and the caddí’s father, a leading community elder. Talon remembered the home he and Meunier shared as one in which their new family “loved them tenderly and appeared to be very angry when anyone displeased them in any way and took their part on these occasions, even against their own children.” The boys had quickly been transformed into kin to make their inclusion in the community permanent. Because Caddos were “so desirous that others imitate and resemble them in everything,” they dressed and tattooed the two boys as their own. Thus, Talon and Meunier received tattoos “on the face, the hands, the arms, and in several other places on their bodies as they do on themselves,” with black dye made of charcoal and water inserted into the skin with thorns. The markings provided overt testimony of their adoption and tribal identification as Caddos.5

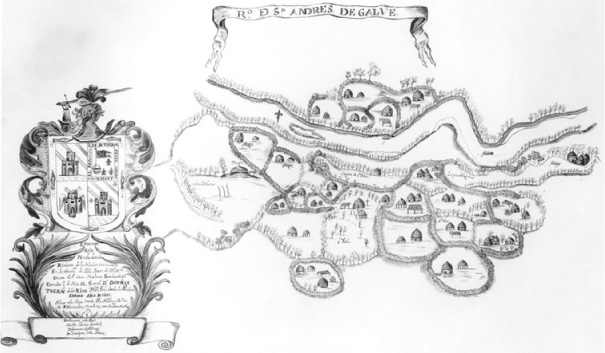

Map of 1691 of Caddo settlement patterns along the Red River, based upon the findings of the expedition led by Domingo Terán de los Rios in 1691–92. Hand copy of the original located in the Archivo General de Indias. Map collection, CN 00920, The Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

The boys then had to be taught the bearing and abilities of Caddo males. Their adopted fathers and brothers trained them to run and swim for strength and fleetness of foot, to shoot arrows for the hunt, and to fight in battle alongside their elders. Talon testified to the “brotherhood” implicit in men’s joint battle experiences when he told French superiors that “an unfailing means, other than small gifts that the Europeans still have of winning the friendship of the nations whose alliance could help them the most in their settlements, is to take part in the wars that they often wage against others.” Though the warriors valued the addition of European firearms among their weaponry, Talon cautioned that he and Meunier “do not think that they ever showed veneration for them.” Indeed, as will be seen, the standing given the adult French deserters who fought alongside Caddo warriors against Apache foes proved Talon’s claim. Instead, the gifts that Hasinais “love passionately” had to be “useful or ornamental,” seemingly to be worn as status markers in reflection of honor and rank or to be passed along to others, “since they give voluntarily of what they have,” as obligated by ties of reciprocity.6

The experiences of the French deserters who joined the two young Pierres to live among the Caddo settlements offered an adult version of the Caddos’ efforts to incorporate male strangers into their communal midst. Two different traveling parties from La Salle’s coastal Fort St. Louis visited Caddoan peoples, first in the summer of 1686 and then in the spring of 1687, during attempts to reach French settlements in Illinois and then Canada. During and after those visits, five French deserters—Jacques Grollet, Jean L’Archevêque, two known only as Rutre and La Provençal, and one unnamed man who died shortly—found not only sanctuary but also new lives among Hainai and Nasoni members of the Hasinai confederacy. In response to the Frenchmen’s supplications—they had arrived sick, exhausted, and clearly in needy condition—Nasoni leaders took them into their communities. As La Provençal attested, the Nasonis “had been very solicitous and taken very good care of him during his illness and had shown him friendship.” The observations of other Frenchmen and Spaniards who later witnessed the deserters’ relations with the Caddo communities provide a portrait of their adoptions.7

Once four of their French charges had recovered, Caddo leaders endeavored to transform the men so that they could find a place in their society, as had the two boys. First, they dressed the men. Henri Joutel, who passed through in 1687 on his way to Illinois, described seeing Rutre in “a paltry covering that the Indians of the area make with turkey feathers, joined together very neatly with small strings,” giving him what Joutel thought was the “naked and barefoot” appearance of having lived with the Caddos for ten years. “As a result, there was almost nothing about him that was unlike them except that he was not as agile”; in fact, upon their meeting, Joutel initially failed to recognize him as a fellow Frenchman. Beyond clothing, the men displayed body decorations—the same birds, animals, and zigzag patterns that marked and identified the faces and bodies of Caddo men. The tattoos signaled their status as men (that is, hunters) and also provided them with markings that would identify them as members of a Caddo society—tattoos that served as both passport and protection into and out of that society.8

Caddos further marked the Frenchmen’s acceptance into their community by providing them with shelter and dwellings. La Provençal lived in the home of a Hasinai caddí that, like most Caddo households of sixty feet in diameter with divided living areas, housed eight to ten families; Rutre and Jacques Grollet lived in the home of a Nasoni caddí in a neighboring settlement. By the time of Alonso de León’s 1689 expedition in search of La Salle’s colony, Spaniards found Grollet and L’Archevêque living in the company of a Hasinai caddí who was “keeping them with great care.” Like Joutel, Spaniards repeatedly commented about how the two Frenchmen were “streaked with paint after the fashion of the Indians, and covered with antelope and buffalo hides.” When Spanish officials later interrogated the two men back in Mexico City as to why they had allowed themselves to be so painted, L’Archevêque explained that, having been “importuned” by Caddo men and women, the Frenchmen had “thought it necessary to do this in order to please the Indians who were caring for them and supporting them.”9

Although the caddís clearly had made the decision to incorporate the men into the Caddo community, the adopted Frenchmen seemed well aware of the matrilineal and matrilocal organization of Caddo kinship and economy that put women at the head of families and households. They took special care to pay equal respect to the ranking women who had authority over the households within which they lived as they did to the caddís and canahas who had first welcomed them into the villages. Rutre, for example, in meeting with Joutel, asked him for “some strands of glass beads to make a present of them to the women of the hut.” The beads were not pretty baubles for girls, but signified a gift obligated by the rules of reciprocity. Joutel matched such deference to senior women whom he regularly referred to as “women of the hut.” Perhaps he followed the deserters’ direction, but he also noted for himself the authority the women exerted over the divisions of household and agricultural labor. While staying among Nasonis, before the Canada-bound party left on their journey north, Joutel recognized that there was a “mistress of women” who “had supremacy over the provision and distribution of food to each person even though there were several families in one hut.” A quick learner, “I took care to always give her something as well, sometimes this was a knife, another time beads or some rings and needles, and also some necklaces of false amber of which I had a number.” The Frenchmen appeared to have learned the everyday rhythms of Caddo reciprocity as well as the balance of power and honor between Caddo men and women.10

The deserters reached another level of kinship through marriages with Caddo women. La Provençal reported being “given a wife,” presumably as a means of providing him with family relations within the settlement. Though Joutel made specific reference only to La Provençal’s Hasinai wife, whom he met personally, he described the other Frenchmen as “addicted to the wantonness of the women who already displayed toward them a certain attachment,” indicating some kind of relationships, even if in his view they were not permanent or proper unions. Years later, Pierre Talon recorded that Rutre “had changed [wives] seven or eight times and left two children by one of these women, following in this, as in all the rest, the custom of the savages, who have in truth only one wife at a time, but who change them whenever they want to, which is to say often.” Just as Joutel framed his interpretation of Caddo women through a European lens that cast the women in an illicitly sexual light, Talon likely exaggerated his depiction of Caddo practices of serial monogamy. Nevertheless, reading between the sexualized European lines, both observations indicate that unions with Caddo women were key to the incorporation of the Frenchmen into not only Caddo society but also the kin relationships that gave a man standing and identity within the matrilineal society.11

Gender and kinship worked in tandem to determine people’s roles in Caddo society. A story Jean-Bernard Bossu later recorded of having met the “half-blood” son of Rutre during his own travels in 1751 points to another key to the Frenchmen’s acceptance among Hasinais and Nasonis: their fighting ability. Bossu claimed that the son told him how “his father had been found and adopted by the Caddo Indians.” “He was made a warrior and was given an Indian girl as his wife,” Bossu continued, “because he had frightened and routed the enemies of the Caddos by using his rifle, which was still an unknown weapon among them at that time.” Joutel similarly related that the four French deserters were “cherished by the Indians because they had gone to war with them.” Not only that, they had succeeded in killing one of their enemies, “quite opportunely with one shot of a pistol or musket,” which had “won them trust and a reputation among the Indians.” Another time, during Joutel’s visit to the Hasinai settlements, the Frenchmen went off to fight side by side with Caddo men in a battle against an unnamed enemy, in the course of which they and the warriors killed or captured forty-eight of the enemy, again with the help of French muskets, which killed several and forced others to flee.12

Hasinai and Nasoni leaders’ interactions with Joutel himself cast further light upon the ways in which Caddos incorporated strangers into their world. From the time he arrived, Hasinai elders “often visited to exhort” him to join their men as a fellow warrior, one time pointedly telling him that “I should be like [Rutre] and go with them to war.” Joutel doggedly refused, however, offering instead that once he reached Canada, he would gather more men and return to fight alongside them. Yet, the calls on Joutel to join Hasinai warriors in battle did not bespeak a need for military aid (as many Europeans assumed) as much as a call for him to prove his worthiness to join the ranks of Caddo men. His refusal must have baffled the Caddo men, especially when Rutre told them that, among the Frenchmen, Joutel was a high-ranking man, if not a caddí at least a “captain.” Thus, when they continued their exhortations, they addressed him as “cadi capita.” In the Caddo leaders’ view, Joutel’s refusals to fight eventually seemed to place him in a separate category of manhood. When the other Frenchmen went off to battle, Joutel and the two priests, Jean Cavelier (La Salle’s brother) and Anastase Douay, remained behind “with the women and several old men who were not able to go to war.” When word reached the settlement that the warriors were returning victorious, Joutel joined the Caddo women who sent out food for their husbands and sons by including his own offering to the fighting Frenchmen. For a week following their return, Joutel saw the Frenchmen and warriors only at public victory celebrations; otherwise, the fighting men spent all their time together in discussions and “amusement” to which Joutel clearly was not invited—surely signaling his exclusion from Caddo military ranks and thus manhood.13

Joutel also joined the two French priests in refusing unions with Caddo women, unions that Caddo leaders tried to broker. One morning, as Joutel was hard at work sewing into shoes some antelope skin he had gained in trade, an elder who had repeatedly urged Joutel to go to war with them “brought me a girl whom he made sit near me and told me to give her the shoes to sew.” Joutel could not explain how, but “he indicated to me in some way that he was giving her to me as a wife.” It seems possible that if the elder had failed to convince Joutel to fight (one way to form a bond with Caddo men), perhaps he viewed this as a different means of giving him standing within a Caddo kin group, or at least some kind of connection. But Joutel again resisted, and after he talked only halfheartedly to the woman, “she realized that I was not recognizing her presence and went away.”14

Senior Caddo women (Joutel’s “women of the huts”) echoed the sentiments of their caddís with solicitations that Joutel and the two priests go to war and with promises that “they would give us wives and build us a hut” if the Frenchmen wished to stay and live with them. Notably, father Anastase Douay had received no such offers of women during the first French party’s visit to the Hasinais a few months earlier—when the French party had made it clear they were only stopping to trade for supplies needed for their trip northward to Illinois. But after the deserters from this first party returned seeking residence in the Caddo villages, Caddo leaders may have assumed the later visitors of Joutel’s party to be seeking a permanent presence in the “land of the Tejas” as well. The implication behind the repeated exhortations about a wife seemed clear: if the foreigners were to remain among Caddos, they had to have the kinship ties of home and marriage necessary within Caddo society.15

These men’s experiences indicated that dress and tattoos may have marked the Frenchmen as adoptees of Caddo society and that fighting together may have made them “brothers” with fellow Caddo warriors, but it was unions with Caddo women that gave them a home, identity, and the kinship connections that were key to finding a place in the Caddoan realm. Caddo leaders and male elites readily formed alliances with strangers without bringing them into Caddo society, but the assimilation of strangers into their communities required the participation of women and took place at the level of individual household and family. Meanwhile, the political significance of the Frenchmen’s adoption into Caddo society was sufficient for the news to travel through native transregional networks. In January 1689, some Jumanos carried reports to New Mexico that, even though La Salle’s colony had been destroyed by neighboring Karankawas, as many as four or five strangers were living among the Hasinais, trading hatchets, knives, and beads to them, assisting them in their wars, and promising to be “brothers” or “relatives” with them in league against Spaniards “who were not good people.”16

In the long run, the adoption and attempted adoption of these few men into Caddo society in the 1680s bore little connection to the Caddo-French relationships that would develop almost thirty years later in the early eighteenth century. None of the men were to be found in Caddo villages when the first formal French post was established in 1716 among neighboring bands of the Natchitoches confederacy. When Spanish expeditions led by Alonso de León and fray Damián Mazanet went in search of La Salle, they found and captured Jacques Grollet and Jean L’Archevêque on the first trip in 1689 and the two boys Pierre Meunier and Pierre Talon on the second trip in 1690 (as well as three more Talon siblings living among Karankawan peoples along the Gulf coast). Rutre had died before the Spanish expeditions arrived, and Caddo men showed his grave and that of the fifth unnamed Frenchman to the Spaniards. The fate of La Provençal remains unknown. The four found living among Caddo communities along with the three children from the Karankawa settlement were taken first to Mexico City and then to Spain to be interrogated about all they knew of French imperial designs in the region. While Pierre and Jean Baptiste Talon eventually made it back to France and then Louisiana, Grollet and L’Archevêque spent thirty months in a prison in Spain before returning to North America, where they spent the remainder of their lives as settler-soldiers in Spanish New Mexico. Their experiences during those early years among Caddos do, however, offer a blueprint for the ways in which Caddos would accept and build kin ties with later French traders in the eighteenth century.17

Continuing along the road-not-taken by Spaniards, Frenchmen led trade expeditions to the Caddo and Wichita bands spread throughout the areas of present-day western Louisiana, northeastern Texas, and the lower Southern Plains after the founding of the province of Louisiana in 1699. When these new French traders came calling at the beginning of the eighteenth century, Caddo custom determined the form and meaning of exchange relationships, and that custom depended upon two types of exchanges of women, one via intermarriage and the other via an emerging trade in captive Indians. Again, an examination of the experiences of Frenchmen offers a contrasting perspective on how Spaniards failed to respond in the same spirit to Caddo overtures of union and alliance.

In 1700, a key commission of the first governor of Louisiana, Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, had been to send his younger brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville to promote trade among Caddoan peoples, but fourteen years elapsed before permanent posts and settlements began to spring up along the Red River. Having identified the numerous and prosperous Caddo settlements as crucial for entry into extensive native trade networks as well as a point from which to initiate expeditions to Spanish posts in New Mexico, Frenchmen established a military post named Fort St. Jean Baptiste aux Natchitoches, near a village of Natchitoches Indians in 1716, along with a subsidiary trading post farther upriver among the Nasonis in 1719 (followed later by Rapides, Avoyelles, Ouachita, Opelousas, and Atakapas posts along the Red River as well). A 1720 report to the French government, addressing the commercial potential of the Natchitoches post and its hinterlands, asserted that the most profitable trade with the Caddoan peoples of the area was in horses, hides, and Indian slaves. As Pierre Talon had testified twenty years before, the Caddos had so many horses that they both caught and raised (valuable to Frenchmen who had no other source for mules, horses, or cattle) that they would exchange them “for a single hatchet or a single knife.”18

At Natchitoches, permanent French settlement first took the form of a trading warehouse that gradually expanded to include a small military post and civil settlement. In the early eighteenth century, private trading companies rather than the French government directed much colonial development. Imperial officials licensed trading companies to oversee internal and external trade within the new French colony, thus giving the companies the power to form alliances in the king’s name, to build garrisons, to raise troops, and to appoint governors, majors, and officers for defense. Such licenses transformed individual traders who developed economic relationships with native peoples into representatives of the French government, putting them on a par with military and diplomatic officers of the Spanish government when it came to Caddo politics. As a result, French-Caddo relations along the Red River continued to take a more personal form at the level of the individual. At the same time, the Caddos’ incorporation of French newcomers into their network of kin relationships took place on a broader scale in the 1710s than it had in the 1680s.19

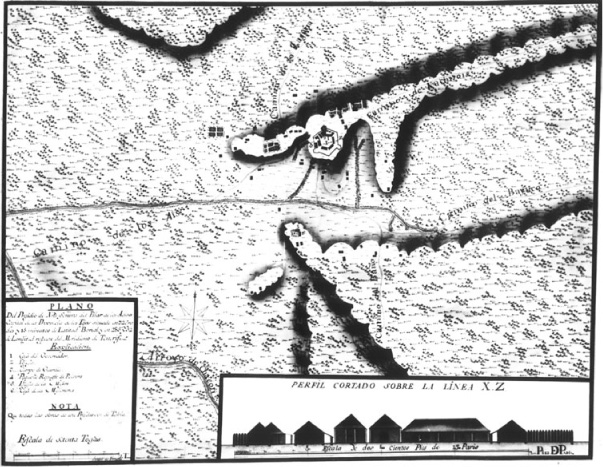

St. Jean Baptiste aux Natchitoches, c. 1722. In 1716, Frenchmen established this military and trading post near a village of Natchitoches Caddos. The map indicates the locations of leading traders’ homes. Map by J. F. Broutin. Courtesy of the Cammie G. Henry Research Center, Watson Memorial Library, Northwestern State University of Louisiana, Natchitoches.

Intermarriage had long served Caddos as a strategy for forming and solidifying political alliance. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, marriage and family linkages had brought together the three Caddo confederacies as well as unified villages and settlements. Europeans observed the power of these bonds in linking together numerous Caddoan polities and peoples. Jean Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe noted that though Caddos lived in different villages, they nevertheless “formed together” a united nation. Juan Agustín Morfi argued that shared friendships, relationships, and intermarriage had joined and made kin “under the general name Texas” remnants of the “Texas, Asinais, Nabedachos, Nacogdoches, Nacogdochitos, Nadocoges, Ahipitos, Cadogdachos, and Nasonis.” They had also allied bands of Caddos and Wichitas. Thus, to Caddos, intermarriage seemed an obvious and practical means of forming political ties and trade relations with Europeans as well.20

When Caddos sought to transform the Frenchmen who arrived in the 1700s into military allies and trading partners, they offered marriage. And Frenchmen accepted their proposals. French settlers and traders by and large came from Canada, where they already enjoyed a social and cultural heritage of intimate association with Indian peoples. Unions with women of allied nations, and later with captive Indian women they acquired from those nations for sexual exploitation, were not new to the Frenchmen who emigrated to Louisiana. Because single male traders and agents, who often lived among their native trading partners, originally predominated in the French occupation of Louisiana, Frenchmen needed to intermarry if they were to have wives and families at all. Abbé Gillaume Thomas François Raynal, writing in the 1770s and looking back over the century, argued that the French had brought to Louisiana “the custom of living with the savages, which they had adopted in Canada,” and which often involved marrying Indian women with the “happiest results.” “There was never observed the least coolness in the friendship between these two so diverse nations whom matrimony had united,” Raynal continued, because “they have lived in this intercourse and reciprocity of mutual good-will, which made up for the vicissitudes of events brought by the passage of time.” French demographic and settlement patterns made social and familial intermixing almost inevitable as they built their trading and military posts in or near native villages. Consequently, Frenchmen joined with native peoples not only for trade but also for subsistence, family building, and daily life. In settlements such as Fort St. Jean Baptiste aux Natchitoches, community ties brought Frenchmen into the heart of Caddo political economies and offered foundations for long-lasting alliances.21

By forming unions with Caddo women, Frenchmen who pursued trade among Caddoan peoples took part in bride-service customs that incorporated them into Caddo systems of male status and honor—whether the Frenchmen realized it or not. In the Caddo system of bride service, marriage was a negotiation between a suitor and a woman’s kin. As fray Francisco Casañas de Jesús María described, “If a [Hasinai] man wants a certain woman for his wife who he knows is a maiden, he takes her some of the very best things he has; and if her father and mother give their permissions for her to receive the gift, the answer is that they consent to the marriage.” Fray Isidro de Espinosa similarly observed that a man spent more time courting a woman’s kin than the woman herself, arguing that a man must “gain the goodwill of the fathers and brothers of his proposed bride by bringing them some deer or stag which he leaves at the door of their home without a word; if they accept and eat the meat, it is a sure sign of their consent [to the union].” Over the course of that negotiation, a man provided goods that demonstrated his ability as a hunter and warrior to defend and provide for a woman’s extended family. Services to a woman’s family continued after marriage to maintain the man’s relationship and status within the woman’s family and the greater clan-based community. Bridal goods thereby served as symbols of the man’s personal prowess. The goods a French trader had for exchange ably substituted for products of the hunt, and the promise of their continued availability brought a different kind of “income” to the clan.22

Membership in a clan in turn gave a man standing in the larger community. Having Caddo wives enabled Frenchmen to participate in customary male exchanges of hospitality and gift giving beyond those of the more formal diplomacy between nations. Marriage in a bride-service society was a key determinant of male rank. A married man, as opposed to a bachelor, had the benefit of a wife (and by extension, her relatives) who fed and cared for the family, who provided a home through her kin or by building shelters herself, and who provided him with sexual intimacy. More important, marriage in a bride-service society allowed a man “to become a political actor—an initiator of relations through generosity,” because “A man who has a wife and a hearth can offer hospitality to other men.” Thus, marriage elevated male status. In this way, initial French-Caddo bonds took place at the level of the family and household rather than at formal levels of diplomacy.23

Over the century, Caddo settlements accepted resident traders into their midst whose status, while not contingent upon intermarriage with a Caddo woman, could certainly be enhanced and strengthened by such a bond. Such relations increased as the number of traders operating directly out of native villages, often as independent entrepreneurs rather than officially licensed agents, grew in response to French commercial expansion. As Athanase de Mézières explained to the viceroy in 1778, every resident merchant sent from Natchitoches was a man “well-versed in writing, skilled in the language of the Indians with whom he deals, acceptable to them, and the best fitted obtainable to inculcate in them the love and respect which it is desired that they should have for us.” Resident traders, but especially “creoles,” De Mézières continued, learned native idioms and, having lived or been reared in Indian villages, knew “how to gain their good-will” and how to “maintain the general union.”24

The post at Natchitoches emerged as the focal point of French relations among the Caddo confederacies and their allies in western Louisiana and eastern Texas, serving as a nucleus of Louisiana’s trade for the remainder of the century. Two traders, Pierre Largen and Jean Legros, were among the first Frenchmen to settle in the Natchitoches area as members of St. Denis’s 1714 expedition, and both formed unions with Ais women (an independent Caddo nation located west of Natchitoches, with whom the Frenchmen lived). Their wives accompanied Largen and Legros as they traded extensively among different Caddoan peoples and must have aided in Legros’s establishment of a trading post among a Caddo band of Yatasis in 1722. Two other figures from Natchitoches’s early years, François Dion Deprez Derbanne and Jacques Guedon, brought wives with them to Natchitoches, Jeanne de la Grand Terre and Marie Anne de la Grand Terre, who were former Chitimacha slaves captured near Mobile in the 1710s. Although not related by marriage to Caddo families, the two couples lived among their trading partners for much of the year. Baptismal records identify their children as residents of Caddo villages, indicating their close ties to Caddos. For example, Louise Marguerite Guedon (daughter of Jacques and Marie Anne) appeared in church records as “a native of the Cadeaux.” Jacques Guedon held responsibility for establishing a subsidiary post at Bayou Pierre in 1723, which soon became known for its multiethnic population. The Derbanne family’s relationship with Natchitoches Indians earned François Derbanne a reputation among provincial officials as “a man reliable, faithful and necessary for the trade in the things that we need among the Indians.”25

Historical knowledge of French-Caddo unions rests upon French sacramental and notarial records, which unfortunately document only those couples who chose to confirm their marriages or the baptisms of their children in the Catholic Church or French courts. Such records tell us nothing of those couples who chose not to seek out such French institutions. Yet, the few who did left tantalizing hints about these relationships. A soldier named Jean Baptiste Brevel married a Natchitoches woman, “Anne of the Caddoes,” in 1736 and with her had two children, Jean Baptiste and Marie Louise, whom they raised “at the Caddoes.” Although their daughter married a Frenchman, as had her mother, their son spent much of his life with fellow Caddo and Wichita men, rounding up wild horses for trade in Louisiana. Other Frenchmen, such as Pierre Sebastien Prudhomme and Barthelemy Le Court, did not solemnize their marriages to Caddo women in the church but testified to the relationships by having their children baptized in the Natchitoches church, even as they and their families continued to live in Caddo villages. Thus, for example, Marie Ursulle of the Caddo nation agreed to Le Court’s wish to baptize their five children, though she herself never submitted to such sacraments. The children of these unions furthered the connections between Caddo and French families through their own marriages. Alexis Grappe, for instance, married Louise Marguerite Guedon, and he and his son, François, became two of the best-known Caddoan agents chosen to represent them in political and economic negotiations with French, Spanish, and later Anglo-American governments.26

In addition to brokering unions between women of their own nation and Frenchmen, Caddo leaders found that European newcomers also showed interest in enemy women, primarily Apaches whom Caddo warriors took captive in war. Prior to the arrival of Europeans at the end of the seventeenth century, Caddoan peoples did not use enemy captives as a source of labor but did capture a small number of women and children in warfare to avenge or replace their dead through adoption. Caddo contacts with Frenchmen soon diverted these captive women and children to Louisiana and began to change the nature of Indian captivity.

Unlike settlers in the British colonies and New France (Canada), those in French Louisiana made little systematic attempt to exploit enslaved Indians as a labor force. Louisiana colonists did hold as slaves some Indians whom French forces had defeated in wars—notably the Chitimachas in the 1710s and the Natchez in the 1730s—but such enslavement was an isolated practice belonging to the early period of French invasion and colonization. In fact, as early as 1706, French officials in Louisiana began lobbying their imperial superiors for permission to trade those Indian slaves for enslaved Africans from the French West Indies. A 1726 Louisiana census listed enslaved Africans as outnumbering enslaved Indians, 1,385 to 159, and this ratio continued to skew due to an ever-increasing African population. Yet, despite the growth in the enslaved African population, the number of enslaved Indians held steady, indicating that the size of the two populations bore little relation to one other. The explanation lay, instead, in gender differences. Even as the imported African slave laborers replaced Indian slaves on plantations and in larger settlements like New Orleans, enslaved Indian women remained fixtures of Indian trade and French family life in western outpost settlements. The minimal use of Indian slaves in the establishment of French plantation agriculture and the French preference for enslaved Africans as a servile labor force indicate that the Indian slave trade remained important primarily in serving male domestic demands in the hinterlands of French settlement. The value to French buyers of enslaved Indians lay in the fact that most of them were female.27

In other words, Frenchmen at posts such as Fort St. Jean Baptiste aux Natchitoches formed marital unions with their Caddo trading partners and sexual unions with the captive Apache women who were often the objects of French-Caddo trade. The slave trade played a crucial role in supplementing the female population at Natchitoches and other posts throughout the eighteenth century. Both licit and illicit relationships became notable enough to inspire heated complaints from French government and ecclesiastical officials that fueled escalating demands for the immigration of Frenchwomen and for official surveillance of interracial sex and cohabitation. Despite such concerns at the imperial and provincial levels, however, the proportion of Apache women among enslaved populations and in Louisiana households steadily increased as trade networks in hides, horses, and captives grew between the French and the Caddos and, through the Caddos, later extended to Wichitas and Comanches.28

Even though captive women could not be used to constitute affinal kinship, their exchange supplemented French-Caddo ties of settlement and family. To its Caddo participants, the slave trade that developed represented two sides of native conventions of reciprocity. Caddos attained their trade goods from a range of sources: the hides came from hunting, the horses from Wichita and Comanche trading partners who raided Spanish settlements in Texas, and the captives from warfare with Apache enemies. One aspect of native conventions dictated that they take captives primarily from those designated as enemies or as strangers to systems of kinship and political alliance—thus, they took captives only in the context of war. On the flip side, once captive women became desirable commodities in Louisiana, their trade served to bind Caddo and French men together.29

Reciprocal relations both required and created kinship affiliation. Participation in exchanges made groups less likely to engage in confrontation and violence and brought them into metaphorical, if not real, relations of kinship. Caddo men cast trade alliances in terms of fictive kinship categories of “brotherhood.” Unlike with marriage, the women who were the objects of exchange did not create the tie of personal or economic obligation; the exchange process itself did so, binding men to each other in the act of giving and receiving. Kinship moved far beyond biological relationships, economic ties could not be separated from political ones, and trading partners were also military and political allies. Meanwhile, the number of “Cannecis” (Apaches) among the enslaved Indian population in Louisiana became so predominant that the provincial governor, Louis Billouart de Kerlérec, argued in 1753 that trade was impossible with the Apache nations. Through intermarriage, adoption, reciprocity, and symbolic kinship relations, the French had become a subsidiary of the Caddos. They were family to the Caddos and enemies to the Caddos’ enemies.30

Returning to the starting point of Spanish-Caddo relations at the end of the seventeenth century, then, one can well imagine that Spaniards had not progressed beyond a Caddoan category of stranger, if not enemy, following their ruinous first contacts. French experiences in Canada, where the success of French trade goals had rested upon their adaptation to native customs, made them better prepared to negotiate Caddo politics. Spaniards in the northern provinces of New Spain had much less frequently dealt with Indian peoples on their terms. Although the Pueblo Revolt had driven all Spaniards out of New Mexico just eight years before the first Spanish entrada to Caddo lands, more commonly, the native peoples encountered by Spanish officers and missionaries had been conquered militarily or devastated by European disease, and Spanish misunderstanding of Indian customs had little consequence for the outcome of interactions where their domination was already assured. Experiences in eighteenth-century Texas proved quite different. When they met a people as powerful as the Hasinais, Spaniards entered negotiations on equal or lesser footing with Indians whom they had to persuade to form an alliance, and with whom misunderstandings could have fatal repercussions.

The events of 1690–93, when the rape of Caddo women by Spanish men brutally violated the sanctity of matrilineal households, heralded the difficulties Spaniards faced in meeting the Caddos’ terms in the wider realm of kin-defined politics. To the dismay of Spanish officials and missionaries, they could only watch from afar as French-Caddo relations grew over the first two decades of the eighteenth century. Monitoring the French presence in Caddo lands as best they could from the distance of Mexico City and the mission-presidio complex of San Juan Bautista along the Rio Grande (which, in the 1710s, represented the northernmost reaches of Spanish settlement), Spaniards had good reason to fear they would never regain a toehold in the good graces of the Caddoan peoples. Over those same years, missionaries who had lived oh-so-briefly among the Caddos kept up a steady barrage of requests to return and repair the damage that had so grievously destroyed their hopes of converting Caddos in the 1690s. But it was not until 1716 that an expedition finally set out for Caddo lands and began the process of rebuilding the missions that Hasinais had forced them to desert in 1693.31

Once back among the Caddos, Spaniards found Frenchmen well-established in Caddoan trading networks, exchanging French guns, clothes, and manufactured goods for animal skins, corn, horses, livestock, and Indian captives. Spanish observers noted first the trade and then the Frenchmen’s relationships with Caddo women. During his expedition to Caddo lands in 1718, Martín de Alarcón reported two Frenchmen living among Kadohadachos “who are the ones through whose hands the French acquire slaves and other things of that land from the Indians.” In 1722, fray Antonio Margil de Jesús, one of the missionaries sent to work among the Hasinais, reported that neighboring Frenchmen “mingle freely with the Indians who live there and some of them are marrying Indian women.” Fray Isidro de Espinosa even recorded that he baptized the son of a Hasinai woman and a Frenchman.32

In seeking to explain the Caddos’ devotion to the Frenchmen living among them, Spanish officials found a clear answer in the French influence secured by traders’ customs of marrying Indian women. The governor of Texas, Jacinto de Barrios y Jáuregui, asserted that the French “regard the Indians so highly that civilized persons marry the Indian women without incurring blame, for the French find their greatest glory in that which is most profitable to them.” Furthermore, missionary fray José de Calahorra y Sáenz had assured the governor “that it is the greatest vanity of the principal Indians to offer their women for the incontinent appetite of the French; to such a point reaches their unbridled passion for the French.” The commercial profit realized by Frenchmen was obvious, Governor Barrios concluded: “As a result [of these unions], no Caudachos, Nacodoches, San Pedro, or Texas Indian is to be seen who does not wear his mirror, epaulets, and breech-clout—all French goods.” Moreover, Spanish officials feared that residence among Caddo communities allowed Frenchmen to spy on Spaniards, “reconnoitering . . . all of this land and the posts that are in it” and “seeking the opportune moment in which to advise his fellow countrymen to send a troop of soldiers.” And of course, in such an attack, family linkages through marriage would ensure for Frenchmen the military help and alliance of the numerous and powerful Caddo bands.33

Most Spaniards remained blind to the Caddos’ initiative in these unions. Civic officials criticized the unions as a French tactic to gain Caddo alliance and trade, when it was really vice versa, while missionaries focused their condemnation on the Frenchmen’s lack of effort to teach Christianity to Caddos. Missionaries’ spiritual concerns found confirmation in the fact that many relationships lacked the sanctity of marriage, implying French deference to “heathen” Caddo practices. To many Spaniards, it was a toss-up who was most at risk of corruption—Frenchmen or Caddos. French acceptance and approval of “heathen” Caddo lifestyles, made implicit by their intermarriage and adoption of Indian customs, demonstrated a lack of concern for Caddo souls and encouraged the Indians’ “heedlessness of religion” with their own. Ambitious Frenchmen, José Antonio Pichardo explained, “corrupt [Indians] with their unbelief and execrable habits, abuse all the persons of the other sex that they can, dress themselves á la Indian—that is to say, they go about un-clothed as the Indians do, paint themselves, and live like them.” Spaniards thus differentiated themselves from Frenchmen, and the French model—the road not taken—remained a subject only for Spanish denigration.34

Although fearfully aware of the economic and political gains of Frenchmen’s receptivity to intermarriage, Spaniards did not emulate their imperial rivals, rejecting Caddos’ overtures of intermarriage. Why? Intermarriage with Indians was not uncommon in Spanish America. Such unions and the mestizo population that resulted reflected the inclusive character of intimate Spanish-Indian relations across New Spain. Conversely, the absence of Spanish-Caddo intermarriage marked the Spaniards’ exclusion from Caddoan political economies. The explanation rests both in Spanish and Caddoan determinations of acceptable behavior inside and outside the boundaries of society. In most parts of Spanish America, Spanish-Indian sexual relations and intermarriage took place within Spanish society. More specifically, it involved Indian populations who were members of conquered groups subject to the Spanish church and state. In other areas of Texas, such as the later villa of San Antonio de Béxar, Spaniards did form unions with Indians who had entered the missions there and converted to Christianity. But intermarriage with peoples of independent Indian nations had not been a tool of Spanish diplomacy beyond the first generation of conquistadores in the sixteenth century. Rather, it occurred only after Indians had been incorporated into Spanish society. Spaniards in Texas therefore rejected Caddos, despite the political and economic costs of rejection, because these nations represented so-called indios bárbaros, outsiders to Spanish society, religion, and authority. In the Texas borderlands where Spaniards were far from conquering any group, however, Spanish conditions upon intermarriage ensured their exclusion from Caddo kinship systems and thus from sociopolitical networks that would have proved advantageous to Spanish imperial goals.35

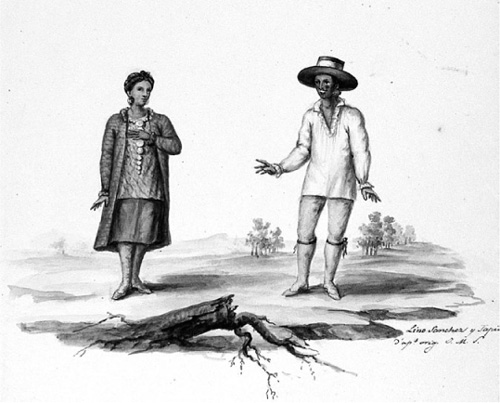

Caddo Indians dressed and decorated in trade items obtained from their Euro-American allies. Watercolor by Lino Sánchez y Tapia after the original sketch by José María Sánchez y Tapia, an artist-cartographer who traveled through Texas as a member of a Mexican boundary and scientific expedition in the years 1828–31. Courtesy of the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

So what did Spaniards attempt instead to satisfy the Caddos’ terms for accepting them back into their lands? Fortuitously for Spanish missionaries and officials, their return in 1716 was in fact aided by one of the Frenchmen already well-respected by Caddo leaders. In an effort to extend French trading networks into Spanish markets, Louis Juchereau de St. Denis—accompanied by twenty-five Hasinais and three Frenchmen—mounted an expedition to San Juan Bautista (along the Rio Grande) in 1714 and stunned the Spaniards there who greeted them. He came, he explained, in response to the bidding of fray Francisco Hidalgo, who had written Louisiana governor Antoine de La Mothe Cadillac in 1710 asking for French aid in reestablishing Spanish missions among the Hasinais. St. Denis further argued, seemingly on a side note, that this also seemed a good opportunity for Frenchmen and Spaniards to open trade with one another. Offering them reentry into Caddo territories, St. Denis’s appearance at San Juan Bautista energized Spanish officials. In response, in 1716 a Spanish expedition, under the leadership of the military commander at San Juan Bautista, Domingo Ramón, but guided by St. Denis, found welcome in Caddo lands. Hasinai, Adaes, and Ais Caddos allowed them to return, presumably in hopes that if, as it appeared, Spaniards were now in league with Frenchmen, then they would change their practices in such ways as would accord with Caddo customs.

The greetings with which the Hasinais welcomed the Spaniards to their villages twenty-three years after their eviction revealed that a Spanish presence there would now be shaped by the Caddos’ relationships with their new French kin. Upon entering Caddo lands, the expedition encountered Hasinai family parties out hunting who greeted them as usual with embraces and food, and one man led them to his hamlet, where more than twenty men and women welcomed the Spanish party with a feast. The next day, St. Denis went ahead to meet with the nearest Hasinai caddí to alert him of their approach; meanwhile, the Spaniards dawdled, traveling slowly and camping for two days in one spot and then another, to give the Frenchman sufficient time for his errand. Word finally arrived at the Spanish camp six days later that it was time to prepare for the arrival of the caddí and his attendants. At this point, the greeting ritual departed from what the Spaniards had expected. Thirty-four Hasinais approached, several releasing salutes with bows and arrows, before more men came on horseback, one by one in a single file, led by several caddís in the center and with St. Denis placed prominently within their ranks. Ramón was also quick to note nine muskets of French make carried by the Hasinai cavalrymen. The Spanish commander knew what was expected and promptly ordered his men into line to greet the Hasinais in matching single-file formation. Ramón himself carried the banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe, and he marched forward with soldiers on either side of him and missionaries behind. In the pipe ceremony, speeches, and feasts that followed, with everyone ranged around by rank in seats laid out by the Spaniards, St. Denis continued to act alongside the Hasinai leaders, translating their words to the Spaniards because he “understands and speaks their language quite well.”36

In the days that followed, the Spaniards were reminded repeatedly of St. Denis’s standing among the Caddos as they moved to new campgrounds and as increasingly larger groups of Hasinais arrived and asked the Frenchman to join their formations in greeting ceremonies. As they processed through the Hasinai villages, St. Denis again paced in ranked order within the three customary Hasinai columns, joining the caddís and leading men in the middle, while the Spaniards marched separately on their own. St. Denis even led them in kneeling to venerate the Virgin’s icon, now a religious symbol of peace that Frenchmen and Spaniards shared. Hasinai warriors continued to salute with French guns and, to top it all off, caddís on the third day brought out a calumet pipe made of brass (surely a product of French trade) to celebrate the proceedings. By that third day as well, the Franciscans were trying to write down some of the Hasinai language, using St. Denis as their interpreter and instructor. What else might they need to do to ingratiate themselves into a Hasinai network newly configured with French members?

By the time the second and third expeditions, in 1718 and 1721, came to settle Spaniards in Caddo lands, the French overshadowed their Spanish rivals all the more. Spaniards had established a presidio-mission complex and small villa at San Antonio de Béxar in 1718, but it was approximately four hundred miles from the political and economic centers of the Caddo confederacies. In 1721, the marqués de Aguayo’s approach to Caddo villages was greeted by repeated messengers notifying him that St. Denis had summoned convocations of Indians from multiple Caddo villages and neighboring native encampments to meet prior to the Spaniards’ arrival. Between San Antonio de Béxar and the westernmost Caddo communities, a united settlement of Bidais, Akokisas, and multiple others responded to Aguayo’s unfurling of the royal standard by unfurling one of their own: a white silk banner with blue stripes given them by Frenchmen. When on August 1 Aguayo finally met with St. Denis to confirm that the truce agreed to by France and Spain following the War of the Quadruple Alliance would be honored along the proclaimed Texas-Louisiana border, St. Denis rode over from his home in Natchitoches to hold the meeting among his Hasinai comrades. By this time, the French government had made St. Denis commander of the Natchitoches post and its surrounding population of French traders and their French and Indian wives, and from the Caddos, he had gained a title of honor translating roughly as “Big Leg.” Because of the location of the French stronghold amidst the powerful Caddoan peoples, the Spanish government threw down a gauntlet: in 1721, they designated the easternmost mission-presidio complex at Los Adaes the capital of the Texas province. The complex (also in the midst of Caddo lands) was built a mere seven leagues (seventeen miles) from Natchitoches.37

There were no gauntlets for Caddos, however, as Spaniards did their best to identify the demands of Caddo leaders and to devise plans that would meet them. Citing past violent crimes as the cause for the 1693 Spanish eviction, officials repeatedly expressed the hope that the presence of soldiers’ wives and families would ensure there was no repeat of the earlier abuses. Viceroy marqués de Valero ordered that only men with families be sent to Caddo lands because “the Indians find it strange that the soldiers do not bring women.” The presence of women and children promised the soldiers’ determination to join Caddo warriors in defense of the region as well as to avoid becoming a threat themselves. “The ties of matrimony,” auditor de guerra (judge advocate) Juan de Oliván Rebolledo argued, “will cause them to take root more firmly wherever they may be assigned on military duty; they will be able to fill their presidio with the children their wives will bear them; thus they will not vex either Indian women who have recently adopted Catholicism or gentile Indian women.” Oliván clearly knew that blame for the first missionary efforts’ failure among the Caddos rested entirely with the soldiers’ rape of Hasinai women. “This kind of disturbance caused much resentment among the Asinaiz that, with Roman tactics, . . . [Hasinai warriors] compelled them [Spaniards] to leave their lands.” In later recommendations, he further directed that the number of soldiers and missionaries be subject to the Hasinai caddís’ approval.38

Having seen the love that Hasinais had lavished on Pierre Talon and Pierre Meunier “as if they were their own,” fray Damián Mazanet had made his own proposal back in 1690, suggesting that Spanish children be taken to the Hasinais to be raised among them while remaining under the instruction of missionaries living there too. Thus, the children “would have a great love for the land”—and presumably remain as settlers—and Hasinais “would love them deeply”—and thus extend loving welcome to other Spaniards. Although no one followed up on that idea in the 1710s, both Spanish officials and Franciscans did emphasize that families, not just women, should make up significant portions of the groups sent to Caddo lands. Moreover, the settlement of families was to be focused around missions and presidios to offset the predominantly male population at each kind of Spanish institution.39

Spanish officials felt so strongly about women’s inclusion in settler groups that they were willing to invest money securing it. Fray Espinosa proposed paying and provisioning women independently of their husbands to encourage their participation in the settlement of Texas. Juan de Oliván Rebolledo made detailed plans for the viceroy, in a series of recommendations suggesting that a colony of Spanish families, each with an annual supplement of 300 pesos, and a colony of Tlaxcalan families (Indians from central Mexico), each with an annual supplement of 200 pesos, be paid and provisioned for ten years, each family receiving plots of land large enough to support themselves with farming and herding. In fact, twenty-five or thirty Indian families could be moved from Parras (at that time in the province of Nueva Vizcaya) to Texas, he argued, since they “are capable both in cultivating fields and in handling weapons,” while the Spanish families could be relocated from Saltillo (also in Nueva Vizcaya at that time) or the kingdom of León. Soldiers too needed to be married, dexterous with arms, and capable of farming, and they could earn an annual salary of 400 pesos (with 50 pesos taken out to pay for the transportation of their families to the land of the Tejas). Colonization plans even suggested that male and female vagrants, “persons of both sexes . . . without a trade,” and “any women taken into custody by court action” be sent as settlers and laborers. Clearly, the identity or status of the women mattered not; their physical presence within settlement groups was the whole point. Spaniards meant the presence of women and families to send a message of permanent residence and, by extension, imperial claim to the French as well. Despite all the plotting and planning, however, none of these settlement schemes ever materialized, as will be seen.40

Surveillance of French demographic patterns had brought Spaniards’ awareness of the significance of women within settlement projects into even clearer focus. Since the 1680s, Spanish officials had estimated French colonial expansion, strength, and permanence in the region upon the presence or absence of women. Such monitoring took an unexpected turn when Caddo leaders intervened in Spanish-French politics. When trader Louis Juchereau de St. Denis traveled from Natchitoches to San Juan Bautista for a second time in 1717, officials sent him to Mexico City, where he was imprisoned for contraband trade and forced to answer questions regarding the intent and destination of French frigates reportedly carrying “families, militia, and missionaries” to Texas. To the surprise of the Spaniards, even this far from Caddo lands, his Indian brethren were able to exert their power and intervene on his behalf. During his first trip to San Juan Bautista in 1716, St. Denis had married Manuela Sánchez Navarro, the granddaughter of Domingo Ramón, and the Hasinai caddís used the union to manipulate Spanish officials. When word reached Caddo lands in 1717 that St. Denis had been imprisoned in Mexico City, Caddo leaders promptly demanded of fray Francisco Hidalgo that Spanish authorities release the Frenchman. The Caddo leaders cagily promised to congregate in missions, Hidalgo reported to the viceroy, but only if and when St. Denis returned to their lands with his wife (who had not yet left her family at San Juan Bautista to join him in Natchitoches).41

Beyond manipulating Spanish authorities to win the release of their French trading partner, Caddos expressed their belief that the presence of St. Denis’s wife would be a sign of his permanent return from Spanish lands as well as his commitment to residing among them and, not incidentally, continuing to supply them with trade goods. In 1718, auditor Oliván forwarded to the king more documents, among which he cited a letter from fray José Diez (another missionary living near the Caddo villages) requesting that the trade goods confiscated from St. Denis at San Juan Bautista be restored “because he has married a Spanish woman” and that he be sent back to the Hasinai villages “because the love of the Indians for him is so great that if they lose him, there is danger of a general uprising.” The Spaniards rejected these Hasinai maneuvers, at first. St. Denis finally escaped confinement in Mexico City and returned to Louisiana in 1717, but without his new wife. Fray Espinosa and fray Margil de Jesús then sent a third round of letters from the heart of Caddo lands, this time to ask that Manuela be allowed to join him at Natchitoches, and finally she did. This tale of diplomatic intrigue revealed the power of Caddo kinship ties; Caddo leaders used their influence to make the Spanish imperial bureaucracy unite a Spanish wife and a French husband who was their trading “brother.”42

Although the highest levels of Spanish bureaucracy wanted to avoid a repeat of past abuses of the Caddos and to make viable a Spanish claim to Texas through a large female contingent among the settlers sent to Caddo lands, in practice, it proved difficult to find settler families for a post so distant from Spanish settlement and supply depots. In 1716, nine missionaries, twenty-five soldiers and officers, three Frenchmen (including St. Denis), sixteen laborers and servants, two Indian guides, and only eight women (wives of soldiers) and two children (for a total of sixty-five people) made up the members of the Ramón expedition. Alarcón’s expedition in 1718–19 brought seventy-two people to the province, including thirty-four soldiers, but only seven families, many of whom remained along the San Antonio River to establish the villa of San Antonio de Béxar instead of traveling all the way to Caddo territory. The final foundational expedition of this early period, that of the marqués de Aguayo in 1721–22, was by far the largest, with five hundred men in eight companies—a contingent that “astonished” the Hasinais—yet, nevertheless, of the one hundred soldiers Aguayo left to garrison the two presidios built in the midst of the Caddo hamlets, only thirty-one had families with them.43

Many of the Spaniards who remained in the land of the Tejas were therefore bachelors like their neighboring Frenchmen. And in Caddoan terms, men who lacked their own families and were unwilling to marry Caddo women meant trouble. Even in the absence of violence, the men, whether soldiers or missionaries, represented a group of individuals without essential kin ties and thus lacked the identity, stability, and commitment to the bonds of alliance they claimed to want with Caddoan peoples. In the initial years of settlement, physical separation added to the Spaniards’ social separation, as they isolated themselves in presidios and missions. In 1716, Spanish Franciscans and military officials established six missions (Nuestro Padre San Francisco de los Tejas, Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción de los Hainais, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de los Nacogdoches, San José de los Nazonis, Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de los Ais, and San Miguel de Linares de los Adaes) and two presidios (Nuestra Señora del Pilar de los Adaes and Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de los Tejas) spread throughout Caddo lands from the Neches River to present-day Robeline, Louisiana. Missionaries and military officers must be held responsible for the Spaniards’ separation from Caddo communities. Both groups tried to prevent abuses by keeping soldiers away from Caddo women. The Franciscans also demanded that if joint Caddo-Spanish communities were to be created, it would be only on Spanish terms—insisting that Caddos come into the missions as Christian neophytes and maintain a distance from those who chose to remain “heathens.”

Caddo leaders repeatedly refused the overtures of Spanish missionaries, politely citing their inability to leave their cornfields, their homes, and the obligations of the hunt—in sum, all that made up their kinship responsibilities. Yet, missionaries noted, Caddos regularly traveled for their own spiritual ceremonies at “houses of worship” where they had “a perpetual fire which they never let die out.” A xinesí served at each temple (fray Espinosa referred to them as a “parish church or cathedral” of the Caddos), which was a large, thatched structure containing an altar and a fire “always made of four large, heavy logs laid to face in the four principal directions.” One temple served Neches and Hasinais, while another was the gathering site of Nacogdoches and Nasoni worshipers, each located within traveling distance of their congregations. Just as Franciscans told Caddos about Christianity, Caddo leaders and priests shared their creation story, showing the Spanish religious men their temples and reciting their rites and beliefs. If not in words, then in actions, Caddos communicated that they were not looking to be incorporated into Spanish religion or society. As Franciscans repeatedly recorded, these “good-humored,” “joyous,” “pleasant,” and “intelligent” people had no need or desire for change. On the other hand, if the Spaniards wished to live among the Caddos, they were welcome to maintain their own spiritual beliefs. In fact, Hasinais argued that just as Spaniards had their heaven and Caddos their own, so too did each have their own god: the Spaniards’ god “gives them clothing, knives, hatchets, hoes, and everything else that they have seen among the Spaniards,” while the Hasinais’ god gives them “corn, beans, nuts, acorns, and other things from the land, with water for planting.” Each to his own. What Hasinai leaders did require was that the Spaniards abide by the conventions and customs that maintained balance, order, and reciprocity. The Spaniards were their supplicants, after all, not the other way around.44

Yet, Spanish efforts to maintain order and reciprocity proved difficult in the early years, especially in comparison with the stability of the neighboring French settlements. St. Denis commanded the Natchitoches post for forty-four years, offering significant continuity to Caddo-French relations, while Spanish presidial commanders came and went in a regular and frequent turnover. More important, St. Denis, and the French traders scattered throughout the Caddo villages, maintained personal contact, whereas Spanish expedition leaders with whom the Hasinai caddís forged pacts in ceremonies of 1716, 1718, and 1721–22 never remained to oversee their obligations of reciprocity and alliance, much less to relocate their wives and families. So, what did happen when these three Spanish expeditions requested residence among the Caddos without establishing a stable friendship?

An examination of housing—central to both Caddo rituals of incorporation and Spanish goals for alliance and conversion—reveals much about the disconnect between the two peoples. That the Caddos allowed missions and presidios to be erected does not indicate that they sought either Christian conversion or Spanish rule, which they clearly did not. Rather, the Caddos’ understanding of the purpose of the Spanish structures must be found within the bounds of their own customs and practices.

Housing had played a key role in hospitality rituals for visitors, and so too did it provide a focus for conventions marking the inclusion of newcomers within Caddo societies. “A Caddo house was more than an abode,” and “houses (or, more specifically, the households represented by the houses) were regarded as constituent elements of matrilineally organized communities.” In Caddo villages and hamlets, house building represented a communal effort, a house’s dimensions reflected the rank of its inhabitants and the organizing principles of the community, and a house’s location in proximity to temple fires, other homes, and the complexes of the caddís reinforced the interconnectedness of families and villages. Thus, in 1716, 1718, and 1721, when caddís offered Spanish leaders homes of their own rather than hosting them in their households, they were inviting them to become members of the Caddo realm.45