Part Two

From Contact to Conversion: Bridging Religion and Politics, 1720s–1760s

The spring of 1709 offered a bounty of bison for groups of Cantonas, Yojuanes, Simaomos, Tusonibis, Emets, Cavas, Sanas, Tohahas, Tohos, Payayas, and many other peoples who moved seasonally through the lands around a central Texas river later known as the Colorado.1 In fact, there were so many bison herds on both sides of the river that about two thousand people had gathered together into one encampment while they pursued their hunting. The combined numbers allowed them to hunt more effectively while at the same time maintaining defensive safeguards for their children and elders against Apache raiders who might contest the hunting territory. No time lacked hardship, and mourning rituals following the death of four community members had recently required moving the extensive camp ten miles in order to put distance between the living and the site of the burials. Yet, wood for the temporary housing was plentiful, and they had quickly rebuilt 150 large, solid, and circular jacales (thatched grass huts) into yet another ranchería, or seasonal encampment, in the customary shape of a half moon. Prospects looked good for a spring and summer free of hunger, following the herds on their slow and meandering progression northward with the shifting growing season of regional grasslands.

Not ten days after the deaths, however, peace was again disrupted when two youths came rushing into camp one morning to tell their seniors of a possible threat south of the river. While out scouting the day before, they had seen copious amounts of smoke—clearly from people making no attempt to hide their presence—and had quickly gone to investigate. They had followed the direction of the smoke and by nightfall had arrived near an encampment. They kept a cautious distance, since they feared it might be a camp of Apache raiders from the northwest, who in recent years increasingly menaced their peoples’ hunting territories. Proudly the two boys explained that they had watched for movements at the camp, gradually approaching until they recognized—still at a safe distance—the distinctive military dress of a Spanish war leader. Once they had ascertained the identity and number of the newcomers, perhaps ten to fifteen men, they raced the twelve miles home to report their discovery.

Spaniards were preferable to Apaches, but recent conflicts over native refugees who had fled from Spanish religious settlements in the south to join relatives among the loosely united groups meant that peaceful interaction was not assured. Two years before, a Spanish war party had come to retake some of these refugees and “recruit” others by force, and thus relations were tenuous. Many in the encampment could have told stories of past encounters with the strangers. It had been almost ten years since a Spanish warrior, José de Urrutia, had left them after spending seven years in their camps. He had come to them wounded, and after nursing him back to health, they had taught him their languages, and he had chosen to live among them. Fighting side by side with their warriors against Apaches, he had proved an invaluable source for better understanding the foreigners to the south. He might be gone, but several principal men now had personal knowledge and experience with Spaniards and could act as interpreters. They chose one in particular, a Cantona leader, to head a delegation of seventy-seven Cantonas, Yojuanes, Simaomos, and Tusonibis quickly assembled to greet the Spanish party and discover what purpose had brought them so far north.

In the morning, they prepared to depart by gathering together gifts given them in the past by Spaniards—carvings, paintings, and banners—that they could display to signal peace and assuage possible Spanish fears about such a large group approaching the small camp. An early start ensured that they would cover the twelve miles in good time to arrive at the camp in the morning. The Cantona leader rode a horse while the others paced around and behind him on foot. Once they were in sight of the camp, those in the lead formed a single line, with the Spanish gifts held aloft and in clear sight—first, a bamboo cross, and then, two painted images and one engraving, all of a Spanish female deity in blue with light radiating out all around her. To complete the greetings, they approached the Spanish men—only seven or eight of them were there—and embraced them and touched their faces. Addressed simply as “Cantona” by the Spaniards, the party leader soon ascertained that the spiritual and war leaders of the Spaniards were away from camp but were expected to return by the end of the day. Forty delegation members chose to await their return in order to speak with them, and the other thirty-seven returned home to report events to their colleagues and families.

After dark, the missing Spaniards finally stumbled into camp. They had apparently gotten lost in the forest but happily had enjoyed a successful hunt, bringing back six bison carcasses with them, enough for a feast for themselves and their guests. Cantona and his colleagues embraced the newcomers in greeting, and the Spaniards honored them in return with gifts of tobacco, according to hospitable custom. Cantona received something further—a silvered-headed cane in recognition of his position of authority. Since night had fallen, the Indian delegation decided to stay at the Spanish camp until morning, using the time in between to talk with three Spanish officials: war leader Pedro de Aguirre and priests Isidro de Espinosa and Antonio de Olivares. Over the course of discussions, the Spaniards quickly made clear that they came not in search of more refugees but of news of Hasinais to the northeast, information the delegation could ably provide. Cantona explained that, no, the rumors about Hasinai migrations southward were false. No Hasinais had even joined them for the hunt this year, as they often had in the past, and they remained in the same villages they had occupied for untold years. Additionally, he felt obligated by his ties to Hasinai allies to tell the Spaniards that neither they nor any other Spanish people would find themselves welcome if they were to attempt to visit the Hasinai villages. Hasinai leaders well remembered the Spanish insults and conflicts of sixteen years before.

The news seemed to disappoint the Spaniards, and in the morning they announced plans to return south. Cantona and his colleagues quickly pointed out that the Spanish party had not yet visited their ranchería—where women, elders, and children as well as men awaited their appearance, as custom required. Recalled to their diplomatic obligations, the three Spanish leaders agreed to accompany the delegation home while seven of the soldiers remained behind to begin packing up the camp. Continuing to use the cross and three images of the female deity as a signal of the peaceful endeavor of the now combined party of Indians and Spaniards, they traveled across the country, following Cantona’s mounted lead. Another horseman, watching for their return, rode up as soon as they came within sight of the ranchería to confirm their identity before returning to the village to alert everyone of their arrival. People poured forth from the jacales, men leaving all arms behind and raising their hands in the air as both a greeting and an assurance of disarmament for the foreign men, who appeared intimidated by the size of the ranchería and the number coming forward to meet them. Men, women, and children soon surrounded the visitors, shouting their welcome, embracing them, caressing their faces and arms and then their own, making sure to include the faces of babies and infants in the exchange of caresses. The women then graciously accepted gifts of tobacco from their courteous guests, while allowing their children to take sweets from the strangers, now acknowledged as friends.

Unable to stay long, the Spaniards soon decided to return to their camp, and, when asked, delegation leaders agreed to accompany them in order to conclude their diplomatic discussions. Cantona soon discovered that the Spaniards wished him to take a message and a gift to Hasinai leaders in the form of one of their customary icons. The two priests quickly assembled a cross out of paper and then decorated and painted it, asking Cantona to pass it along to Hasinai caddís. They wished him to extend an invitation to Caddo leaders to come enjoy the hospitality of their rancherías to the south. They seemed to hope Cantona’s influence might carry weight with the caddís, since they asked him further to show them the silver-headed cane he had accepted as a gift from them. Since he and his people would meet with some Hasinais after the hunting season to trade bison meat and hides in exchange for agricultural produce, such a request could easily be met, so Cantona agreed. He had warned the Spaniards of his Hasinai allies’ lack of receptivity to their overtures, so he assumed they understood the likelihood of yet another rejection. Cantona and the other leaders were more interested in maintaining peaceful relations with the Spaniards, because if Apache raiders continued to cause them problems, one day soon they might need all the allies they could get. Spaniards, though few in number, at least came with guns and horses. Their Apache foes did not have guns, so those were less crucial, but horses were becoming increasingly important, and at present, they had only a few. Yes, the possibility of Spanish alliance bore consideration. . . .

This story takes us back in time to 1709, just before the Caddos allowed Spaniards to return to their lands, in order to introduce early exchanges between some of the Indian peoples living in the area of present-day central Texas and some of the Spaniards marching to and from Caddo lands. Following their eviction from Hasinai villages, Spaniards had fallen back to the Rio Grande, where they built a presidio and three missions: the Presidio de San Juan Bautista and the Missions San Juan Bautista, San Francisco Solano, and San Bernardo. That location provided a base for Spanish expeditions into Texas for the next twenty years. In the 1710s, as Spanish expeditions renewed their treks into Caddo lands to challenge French claims to Caddo alliance, their routes took them through the territories of Cantonas, Payayas, and many others in and around joint settlements that the Spaniards referred to as “Ranchería Grande.” These native peoples were tied into far-ranging, multiethnic coalitions made up of small subset populations of mobile hunting and gathering bands, who together controlled chosen geographic regions and resources. The information networks that stretched throughout those coalitions were as attractive to Spanish officials as their souls were to Franciscan missionaries.2

“Ranchería grande” was at first a general Spanish term for the kind of confederated, semisedentary encampments they found in that area of Texas. But they soon came to use it to specify certain bands of Indians they encountered time and again encamped at different sites between the Colorado and Brazos Rivers as they traveled more frequently through the region after 1709. As a result of those encounters, a series of negotiations began between Spaniards and affiliated Indian peoples that eventually led to the establishment of three shared settlements of Spaniards and Indians based around San Antonio de Béxar. The choices made by these native peoples illustrate a new way that Indian families determined mission-presidio complexes to be of use to their survival. They meant the settlements founded with Spaniards to be a means of formalizing an alliance, not of declaring subordination to Spanish rule. As fray Benito Fernández de Santa Ana explained to his superiors, the Indians of the region who joined mission settlements “want no subjection to royalty. . . . Their first interest is in temporal comfort.” So, why did their response to Spanish missions, tempered though it was, differ so much from that of the Hasinais?3

Different communal and social patterns as well as more recent demographic decline and increasing threats from Apache encroachment set the stage for native peoples of central Texas to view Spanish diplomatic overtures in a new light. Like the Caddos, they had suffered population losses, but theirs had been more recent and more destructive. Indian bands living in southern and central Texas in the 1700s had also coalesced into confederacies for greater strength, subsistence, and defense. Yet, unlike Caddoan peoples, their socioeconomic systems had resulted in political structures less centralized and less hierarchical than the three Caddo confederacies. Most striking of all, the experiences of many of the Indians (such as Cantonas and Payayas) reflected the impact their societies had already sustained from a Spanish presence south of the Rio Grande during the seventeenth century.4

The rituals enacted in the 1709 meeting hint at their prior experiences with Spaniards. The carefully orchestrated use of a cross and the iconography of the Virgin of Guadalupe by Cantonas, Yojuanes, Simaomos, and Tusonibis might appear to echo the early contacts of Caddos and Spaniards, but in fact a different political context put a different spin on the use of Spanish symbols. Like the Hasinais, these native leaders had their own uses for the icons and rosaries given to them by previous Spanish expeditions. In this native world, it was not the female gender of the Virgin’s image that connoted peace. Instead, the iconography represented former gifts that had been given and accepted by male leaders in friendly exchange and now served as mnemonic icons of that previous, peaceful encounter. The more loosely structured confederations of these hunting and gathering bands—who coalesced and dispersed seasonally over the year—required that “groups and individuals maintain a vast network of friendly contacts, that individuals be easily identified while traveling, and that people abide by recognized and expected behavioral rules.” With such expectations, the crosses carried by Spaniards became a kind of passport in that native region.5

Spaniards thus found crosses, rather than the standard and its image of the Virgin, to hold greater meaning for native leaders of central Texas. In 1691, Spaniards traveling on their way to the Hasinai villages had passed through a Payaya encampment where a tall wooden cross had been erected in the midst of their jacales. The inhabitants explained that they knew Spaniards put crosses in their houses and settlements in order to please or appease their gods, so they hoped similar spiritual benefits might accrue to their community if they did the same.6 Perhaps they endowed the talisman from the south with power in order to deal with dangers from the south—disease and marauding Spanish soldiers. More often, crosses became symbols of diplomacy. In 1716, five hundred Payayas, Cantonas, Pamayas, Ervipiames, Xarames, Sijames, and Mescales took Spanish missionaries to a ranchería grande, shared food and traded with them, and marked the site of the peaceful exchange with a wooden cross.7 The Spaniards responded in kind, using crosses to announce their passage through the region. In 1719, Spaniards recorded that “Some crosses were left on the trees for the Indians as a sign, and on them some leaves of tobacco were hung, in order that, coming to reconnoiter, they would see that we were Spaniards.”8

Why the later preference for crosses over images of the Virgin? As opposed to Spanish-Caddo contacts that had begun in peace and then were interrupted by violence, Indians of south and central Texas had had only violent encounters with Spaniards in the seventeenth century. For them, peace had to be forged in an atmosphere of distrust and suspicion. Cantonas, Payayas, and their multiple allies never had the chance to read (or misread) the Virgin Mary as a female symbol of greeting. Their earliest exposure to the Spanish standard had been in war—war waged by Spanish raiders or militias who, throughout the seventeenth century, crossed the Rio Grande bent on capturing Indian men, women, and children and imprisoning them for work camps or missions, two indistinguishable institutions from an Indian perspective. If they had singled out the Virgin, she would have resonated more with sixteenth-century Spanish imagery of La Conquistadora. When these Indian peoples later zeroed in on the cross as a diplomatic symbol to use with Spaniards, they did not choose the iconography of a male Jesus over a female Mary. Rather, they chose crosses based on their own diplomatic protocols. Crosses were the gifts received from more recent, and more peaceful, Spaniards, and their protocols called for a display of past exchange items if and when such peaceful visitors returned.9

These Indians peoples, their parents, and their grandparents had suffered at the hands of Spaniards long before this new round of contacts began in the eighteenth century. The advance of the Spanish frontier northward into present-day Nueva Vizcaya, Coahuila, and Nuevo León over the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries had gradually pushed Indian peoples northward. Yet, it was not Spanish settlement but the spread of European diseases and the intrusion of slave-raiding expeditions seeking forced labor for Spanish mines and ranches—inexorable forces that preceded much of the colonization of those northern regions—that put native peoples in flight. Epidemics that began in the 1550s had, by the 1700s, decimated native populations across northern regions of Mexico, scything their numbers by 90 percent.10 Over the same period, Spanish demands for labor in their farms, ranches, and mines brought its own brand of annihilation. By 1600, trafficking in enslaved Indians had become an established way of life in Nuevo León. Then, once the Spanish population had killed off all the nearby Indian peoples by congregating them in crowded, unsanitary work camps where they died from disease or overwork, the Spaniards extended the relentless reach of their slave raids northward.11

To escape that reach, remnants of multiple bands who had lost family and community to death or enslavement gradually moved northward in search of new lands, new hunting territories, and new consolidations of kin and alliance. Although they had originally lived in regions far different and distant from one another—some native to the region, others migrants from lands ranging across present-day northeastern Mexico—multiple groups had coalesced in shared, mobile encampments in northeastern Coahuila and south Texas. By the end of the seventeenth century, south Texas provided sanctuary for an impressively diverse if ravaged congregation of native peoples and displaced refugees. Yet, their northward progression put them in the path of another danger: newly mounted Apaches from farther northwest, whose own hunting and raiding economy brought them south, following the migrations of bison herds and the lure of Spanish horses. In response, natives and refugees increasingly consolidated their numbers for communal shelter, subsistence, and defense in south and central Texas.

The resultant hunting and gathering groups tended to live in small, family-based bands, moving regularly in response to seasonal subsistence patterns in specific territorial areas. The small size and geographical dispersion required by their socioeconomic systems limited their social and political organization, yet many groups maintained both smaller camps made up of individual ethnic groups and, at other times, larger shared settlements where two or more groups came together for purposes of hunting and defense. Archaeological evidence indicates that both types of settlement existed during the precontact period, but shared encampments became notably more frequent during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, reflecting the upheavals caused by Spanish and Apache invasions.12

These shared encampments and shifting group associations have made identifying the linguistic and cultural affiliations of many of these peoples difficult and often impossible. The language and ethnic origins of the Cantona groups encountered by the Espinosa-Olivares-Aguirre expedition in 1709, for example, are a mystery. From 1690 onward, they shared settlements variously with Caynaaya, Cholomé, Cíbola, and Jumano peoples from western Texas, with Coahuilteco speakers such as Payayas, Xarames, Mescales, and Ervipiames who had migrated from northeastern Mexico, with Tonkawa speakers such as Cavas, Emets, Sanas, and Tohahas from north-central Texas, and with Wichita speakers such as Yojuanes who had migrated from north of the Red River in Oklahoma.13 Such relationships among so many different peoples leave scholars to guess at the parties with whom Cantonas may have shared the closest ties.14

For a long time, many scholars erroneously referred to all hunting and gathering peoples of northeastern Mexico and south Texas—those most noted in association with Spanish missions at San Juan Bautista, Coahuila, and at San Antonio, Texas—as “Coahuiltecans,” implying a linguistic and cultural relationship unifying untold numbers of people merely by their regional location and periodic residence in the missions there. Recent research, however, has shown that in fact this myriad of native peoples represented hundreds of small, autonomous bands who may have shared certain general traits but whose local and regional variations differentiated them quite distinctly. Most notably, at least seven different language groups—Coahuilteco, Karankawa, Comecrudo, Cotoname, Solano, Tonkawa, and Aranama—can be distinguished in Spanish records. Part of the scholarly confusion arose because the ties that developed among these peoples—begun in their shared encampments and continued in the missions—eventually led to the use of Coahuilteco as the lingua franca by the late eighteenth century. Yet, beyond consideration either as a broad regional categorization or as a language group, the term “Coahuiltecan” cannot be used accurately to define a single group of people. As one archaeologist asserts, “We know a little about many of the Coahuiltecan groups but not much about any one of them—or any one aspect of their lifeway.” Such a quandary testifies not only to the tragic consequences of European disease but also to the success of native confederations.15

In addition to the multiple allies and neighbors of Cantonas and Payayas in south and central Texas, coastal-dwelling Indian peoples also established on-again, off-again relations with Spanish Franciscans. These were marine-adapted hunting and gathering groups who lived along the present-day Gulf coast of Texas: Akokisas, Aranamas, Atakapas, Bidais, and Karankawas (who included Cocos, Copanes, Cujanes, Coapites, and Karankawas proper). Similar to the Indian groups of south Texas, these peoples lived in small, kin-based bands moving strategically between the mainland, coast, and barrier islands to take advantage of a variety of key resources when and where they were most abundant. They spent the spring and summer months dispersed for seasonal subsistence rounds in the salt marshes and upland prairies of the coastal plains, where they hunted bison, deer, and small animals and gathered nuts, roots, fruits, and greens. In the harsher months of fall and winter, though, they congregated together in estuarine bays, lagoons, and a narrow chain of barrier islands along the coast to form large fishing encampments focused on saltwater fish and shellfish. The islands also offered invaluable defensive positions for confederated settlements against native and European enemies alike. Unlike others, they did not feel the full brunt of Apache expansion into the south-central regions of Texas.16

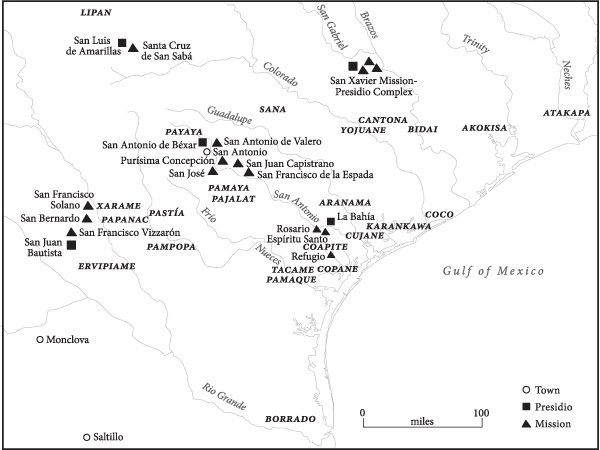

Territories and locations of Indian peoples who used the Spanish missions at San Juan Bautista, San Antonio de Béxar, and La Bahía as joint settlements. Map drawn by Melissa Beaver.

The strategy of seeking safety in shared settlements may have encouraged many of the central and coastal native peoples to consider Spaniards possible partners or allies in a new form of mutual encampment via mission-presidio complexes. It can be no coincidence that the heart of Spanish missionary settlements in Texas took hold at a site long used for shared encampment, shelter, hunting, and defense—a site that natives called “Yanaguana” and Spaniards would come to call “San Antonio de Béxar.” It was in the mid-eighteenth century that crosses became political tools of truce and later symbols marking the sites of diplomatic alliance between Spaniards and Indian peoples. Yet, that transformation—sought by the joint efforts of Spanish and Indian leaders alike—was never complete. The early battles against European disease and Spanish raiding parties colored the eighteenth-century struggles of Indian men and women as they sought to maintain not only the physical but also the social and cultural integrity of their families from within the fortifications of missions. Although we tend to assume missions were European-directed spaces in which Indians could only “resist,” the power relations within mission-presidio complexes of south and central Texas clarify how Indians could, in fact, exert control over the terms by which they lived together with Spaniards. In this setting, a different kind of tightrope bridged Spanish and Indian visions of male and female behaviors to define their carefully negotiated steps toward peaceful coexistence at midcentury.