Chapter Three

Civil Alliance and “Civility” in Mission-Presidio Complexes

The exigencies of daily life in south-central Texas—a world fundamentally shaped by the regular occurrence of epidemic diseases and Apache raiders—led Spanish and Indian peoples to join forces for survival and defense beginning in the 1720s. Mission-presidio complexes provided the locus of such alliances. Once they had all been brought together, the five missions, presidio, and Spanish villa along the San Antonio River “form[ed] one community,” fray Benito Fernández de Santa Ana claimed in 1740. Another community of Spanish and Indian settlers developed around the missions and presidio of La Bahía, closer to the coast. From the perspective of Spanish record keepers, these locales looked like familiar sites of religious conversion and regional defense as set up throughout New Spain. From the perspective of semipermanent native residents, the communities looked equally familiar, but as sites for socioeconomic alliance and communal ritual that existed across southern Texas and northern Coahuila. Though known by their Spanish names and with architecture outwardly reflecting the form of Spanish institutions, the native use of the community complexes resembled far more the joint settlements and confederated encampments that had been customary in the region long before the arrival of Europeans.

Indian peoples of southern and coastal Texas were no more inclined to forsake their settlement and subsistence patterns than the Caddos, but their socioeconomic systems allowed them to integrate part-time residence at missions into their seasonal calendars. From the 1720s through the 1760s, many never joined Spaniards in their settlements, however, and most made only periodic visits to the complexes as part of their annual subsistence cycles. For those who did visit, Spanish missions suited a different kind of settlement-as-alliance strategy, as Spanish and Indian men agreed to bring their wives and children together in shared communities. The transitory residence of south-central natives and the greater vulnerability to Apache raids felt equally by Indians and Spaniards gave Indian peoples the power to exert control over their relations with Spaniards—power that would be grounded in the gendered terms by which they would live together.1

Over the middle years of the eighteenth century, Coahuilteco-, Tonkawa-, and Karankawa-speaking peoples incorporated the sites of Spanish missions into an old pattern of subsistence, seasonal migration, settlement, and alliance. Indian families sought a semisedentary encampment where they could gather to acquire food, shelter, and defense. By their own custom, aggregate settlements were the locations for annual or biannual practices that served to renew alliances through communal rituals of healing and spirituality, exchange, joint hunting expeditions, and feasts. These gatherings also offered the opportunity for courtship and intermarriage that extended economic and political relations into the realm of kinship. Indians brought similar expectations to the settlements established with Spaniards, but they were not always met. Constant problems with the supply of material goods and foodstuffs promised by missionaries, the encroachment of ranches and farms into traditional hunting territories, the growing threat of Apache raiders attracted by Spanish cattle and horse herds, and the far more deadly threat of European diseases all fatally detracted from the initial appeal of mission-presidio complexes. Spaniards also put conditions on the exchanges they were willing to make with their new Indian allies. They tried to assert that their own practices and ceremonies take precedence over native ones within the confines of the settlements.

Spaniards thus fundamentally challenged native notions as to the form that joint settlements should take. Franciscans who came to Texas in the eighteenth century saw the “civilization,” or what historians have referred to as “hispanization,” of Indians as crucial to the process of Christian conversion. Their mission was twofold: first, teaching the fundamentals of Christian worship and administering the holy sacraments; second, the more temporal task of instructing Indians in how to live as Christians, or more aptly, as Spaniards. The hispanization program endeavored to instill conditions in the lives of Indians that would encourage a “virtuous” life: recognition and respect for royal government and law; life in a communal, town setting; Euroamerican material accoutrements, such as dress and housing; and Euroamerican familial and sexual practices, particularly monogamy formalized through a marriage ceremony. The temporal training of Indians, fray Mariano de los Dolores y Viana explained, would teach them “to live the common and civilized life,” a necessary lesson, because “without the human strength the spiritual would not be gained.” Similar to their opposition to syncretism in religious concepts or rituals, missionaries did not imagine it possible to interweave Indian and Spanish social practice. Instead, they believed that Indians’ “savage” lifeways had to be destroyed and replaced with Euroamerican customs congruent with Christian ethics and morals.2

Yet, the contest between differing visions of social organization took place within an unstable demographic and geopolitical setting that limited both the Spaniards’ ability to assert their demands and the degree to which any Indians would commit to joint settlements with them. This period was marked by disease repeatedly cycling through Spanish settlements, hitting native residents the hardest, and economic instability caused by fitful Spanish supply routes and Apache raids disrupting efforts at agriculture, ranching, and trade with other Spanish provinces to the south. Disease exacted the greatest devastation, as Indian populations faced epidemics in the region at least once every decade. When that was combined with low fertility rates, high infant mortality, and high female mortality in childbirth, records indicate that, until the 1780s, only the recruitment of new residents maintained a “nominal stability” in Indian populations living in San Antonio. When the Spanish alliance did not meet their material needs or set terms that they were unwilling to meet, many Indians left to rejoin relatives and allies in settlements elsewhere. Most kept their visits to the missions brief and while present expressed but a superficial and temporary adherence to Spanish practices. Thus, missions functioned solely as a temporary seasonal base at which individuals and family bands could meet periodically to marshal resources, intermarry, and regroup socially and culturally. With families moving in and out of the missions on a constant basis, Franciscans negotiated their hoped-for reforms with peoples who could and did remain closely tied to their own customs and belief systems. Equally important, when Indians were in residence, the subsistence and defense needs of the mission populace continued to rely upon native socioeconomic and military knowledge and skills. Although Franciscans urged Indian men and women to abandon their customary norms and behaviors as a step toward “civilization,” the survival of Spanish and Indian populations in and around the missions often depended precisely upon the maintenance of native gender conventions.3

Constructions of masculinity and femininity lay at the heart of Spanish “civilization,” while gender was equally important to Indian conceptions of who they were as peoples and cultures. As a result, the customs that missionaries most sought to change were the ones that Indians most sought to maintain. Thus, the struggle over the terms governing their joint settlements more often than not drew its battle lines along contrasting notions of manhood and womanhood. Still, the realities of a world defined by European disease and Apache raids meant that the battles of eighteenth-century daily life did not end up waged over competing concepts of civilization (or God); they were fights for safety and subsistence. In that contest, native-dictated patterns of domestic and diplomatic alliance were crucial to both Spanish and Indian survival and thereby proved to carry the day.

On August 16, 1727, two days after recording that they had crossed the “creek of Los Payayas, named for a nation of Indians who live much of their lives on it,” Pedro de Rivera and his inspection team rode up to the Presidio San Antonio de Béxar. Two “small pueblos” of Indians each stood about a mile away, one to the northeast, the other to the southwest, both inhabited by Mesquites, Payayas, and Aguastayas. Each was associated with a different mission: one with San Antonio de Valero, the other with San José y San Miguel de Aguayo. Yet, to observer Rivera, it was not two missions but two Indian settlements that stood in company with the presidio. In similar language four years later, fray Benito Fernández de Santa Ana recorded the transfer of three nominal missions from Caddo lands as the addition of three “Indian villages” side by side with the newly named Spanish villa of San Fernando de Béxar along the river.4

Indian names as well as settlements dominated the landscape, marking the land as theirs. Located in the “best position of any [he] had seen,” Rivera remarked upon San Antonio’s potential for farming and ranching but found that fifty-three soldiers, a captain, and two lieutenants at the presidio spent all their time on military patrols and convoys aimed at holding off Apache raiders from “la Lomería,” the hill country to the northwest of the settlement. Rivera’s emphasis on the predominance of soldiers among the Spaniards, the lack of a civilian population, the location of the presidio situated to contain the “Apaches de la Lomería,” and the soldiers’ constant occupation in patrols and convoys indicated that the joint settlement looked most like a defensive fortification. Moreover, he noted in his report the potential rather than present use of the land for farming and ranching as well as the need for “people to work the land.” Apparently, the Spanish and Indian settlers did not yet have significant crops or cattle under cultivation, and the Indians were not providing the labor force expected by the Spaniards. Tellingly, Rivera observed, the countryside and its rivers offered an abundance of wild animals, particularly bison and deer, but also bears, turkeys, and catfish, suggesting that the actual sources of subsistence were hunting and fishing. Along with the military men’s wives and children and four civil residents, Governor Fernando Pérez de Almazán estimated the total Spanish population to be about 200 by 1726. Six years before, Juan Antonio de la Peña had recorded that the two Indian settlements at Valero and San José had 240 and 227 residents, respectively (and that number did not include the neighboring Indian settlement at Ranchería Grande); thus, the Indian population, when present, was more than twice the size of its Spanish neighbors. Pointedly, when Rivera discovered that the presidial captain had stationed two soldiers at each mission settlement to assist in defense, he deemed this protection unnecessary, given the presence of able Indian warriors among the residents. Altogether, the picture Rivera painted was one of Spanish and Indian settlements side by side, living in close proximity in a mutually dependent relationship of subsistence and defense.5

How had those allied but still separate Spanish and Indian communities come into being in the nine years preceding Rivera’s visit? Individual negotiations between officials of the Spanish church and state and the male heads of different family bands had created the settlements one by one. The first mission-presidio complex in this area of Texas officially appeared in 1718, when Franciscans transferred Mission San Francisco Solano, originally established in northeastern Coahuila in 1700, to a site called “Yanaguana” by Xarames, Payayas, and Pamayas. The community there would be known as Mission San Antonio de Valero by Spaniards. Ten Spanish soldiers and their families along with seventy members of the Xarame, Sijame, and Payaya confederation moved together from Coahuila. Though Payayas represented one of the more numerically dominant groups in the regions surrounding both the Coahuila and Texas sites, only Marcela, a twenty-five-year-old woman, and Antonio, a young man of unknown age, actually moved from Coahuila. No one came from the Yanaguana area at all, and it took two months for the Coahuila migrants to persuade some of their Payaya and Pamaya allies and relatives to join the settlement. Slow beginnings indeed.6

Strikingly, although Spanish political ritual and nomenclature—as conveyed through Spanish records of events—colored this diplomacy, native conventions of male-led family bands determined the structure of the joint settlement. Payaya, Pamaya, and Xarame headmen at the new Valero pueblo divided up among themselves the titles of gobernador (governor), mayordomo (superintendent), justicia (judge), regimiento (town council), and alcaldes (magistrates) to reflect balances of power and obligation among the three groups’ leaders. Spaniards further recognized the men with special clothes, gifts, and batons of command, thereby acknowledging the headmen’s political standing within the new settlement and in the day-to-day functioning of the mission communities. Martín de Alarcón might claim to have instituted such offices “so that thus they [the Indians] might enter better into the art of government,” but the “choices” of recognized leaders suggest deference to native hierarchies of authority and governance.7

Families of Pampopas, Pastías, and Sulujams established a second settlement in the San Antonio area known as San José y San Miguel de Aguayo. Three of their headmen, one from each of the groups, had met with fray Antonio Margil de Jesús in 1719 to discuss the possibility of establishing an allied village with the Spaniards but had made clear that they desired one separate from the Payaya-dominated community at Valero. Margil, in commenting on both their large numbers and the respect they instilled in other area Indians, emphasized that Pampopas, Pastías, and Sulujams operated from a position of power when demanding that Spaniards ally with them separately. In their turn, Xarame and Payaya leaders at Valero tried to ensure that this second proposed settlement did not infringe upon their territory. Fray Antonio de Olivares joined the Valero council in presenting a formal request to Juan Valdéz, captain of the Béxar presidio and judge of the commission delegated by the provincial governor to establish San José, that he enforce Spanish law requiring a minimum of three leagues between frontier settlements. Thus did Spaniards comply with the demands of the two native confederations.8

On February 23, 1720, Captain Valdéz stood in for the absent marqués de Aguayo in formalizing a settlement site three leagues from Valero for Pampopa, Pastía, and Sulujam family bands. In ceremonial recognition of their possession of the site, Valdéz grasped hands with native leaders, accompanied them on an inspection tour of the boundaries and water resources, and watched as the men ritually pulled up grass, threw rocks, and sliced branches from the brush to signal that land clearing would soon begin. As with the Payaya confederation, in recognition of their civil and criminal jurisdiction, Captain Valdéz gave insignias of office to Pampopa headman Juan, who would serve as gobernador of the settlement; to Sulujam headman Nicolás, who would be alcalde; to Pastía headman Alonso, as alguacil (sheriff); and to a Pampopa named Francisco and a Sulujam named Antonio, who would serve as regidores (councilmen). Valdéz provided Spanish ritual to the occasion when he exhorted Indian leaders that they govern, set up a watch, maintain good conduct, construct homes and beds so as to sleep off the ground, raise chickens, promote the progress of their village, follow the guidance of the missionaries, and have their families do so as well “for the service of God.” The directives’ content, translated for the Indians by Captain Lorenzo García as best he could, reflected Spanish goals of conversion, but the ceremonies nevertheless made clear that political, civil, and diplomatic authority resided with Pampopa, Pastía, and Sulujam leaders, leaving missionaries to act as a new kind of shaman in native, if not Spanish, eyes.9

A third set of negotiations had begun shortly before, in 1719, between Spaniards and the Indian residents of the Ranchería Grande, although they took much longer to come to fruition. That year, Alarcón formally recognized the authority and leadership of an Ervipiame named “El Cuilón” (“Juan Rodríguez” to Spaniards) with a gift of a “baton of command.” Rodríguez was then about forty years old, had been born in Coahuila, and passed time at the mission established in 1698 for Ervipiames, before they abandoned the Spaniards in 1700. Since then, he, his wife, Margarita (an Iman Indian), and their children, Ana María, Miguel Ramón, and Francisco, had been living among their relatives in Texas and, with them, had joined the Ranchería Grande. Spaniards clearly depended upon the aid and diplomacy of this group, since the 1719 Alarcón expedition remained stranded in San Antonio until a Payaya and a Muruame from the Ranchería Grande agreed to guide them to the Caddo villages in the east.10

Spanish diplomatic exchanges with Ranchería Grande leaders only turned into an alliance when the marqués de Aguayo met with Juan Rodríguez and fifty families in 1721, exchanged gifts, and discussed erecting a third, separate settlement within the Yanaguana area. Interestingly, these negotiations may have been rooted in the Spaniards’ need for Rodríguez’s aid in their diplomacy with the Caddos. Rodríguez and other leaders from Ranchería Grande had gathered information for their own ends about Indian bands—many of whom came from the Ranchería Grande itself—who had met in convocation with the Frenchman Louis Juchereau de St. Denis that year. When Aguayo went east to meet with the Caddos and to confront St. Denis, Rodríguez agreed to accompany him on the trip. Spaniards needed the alliance of the large confederation not only for overtures to the Caddos but because they also feared losing Ranchería Grande residents to a French alliance. This concern had been made all too apparent when confederated Ranchería Grande leaders greeted Aguayo by unfurling a French flag when he arrived at an encampment on the road to the Caddo villages. All Aguayo could do was request that the Spanish standard be added to their flagpole along with the one given them by Frenchmen—he had no power to displace it. Gifts of tobacco, cattle, food, and clothes followed as Aguayo worked to win them over. In similar spirit to his diplomatic ploys with Caddo leaders days later, Aguayo called his men into a square battalion formation with a trumpet call “so that the [Ranchería Grande] Indians would be loyal to the Spaniards out of love and fear.” Adding to the display, his men urged him “to ride his horse in the Spanish manner, to impress the Indians with the advantages of a horsemanship that they had never seen.” Aguayo thereby “maneuvered [his horse] masterfully with all the different turns and styles that are customary” before assuming his place at the head of the battalion and leading the soldiers in a ranked procession. Thus did he woo the Ervipiame leader Rodríguez and his colleagues with advertisements of the advantages offered by a Spanish alliance—numerous fellow warriors, guns, and horses.11

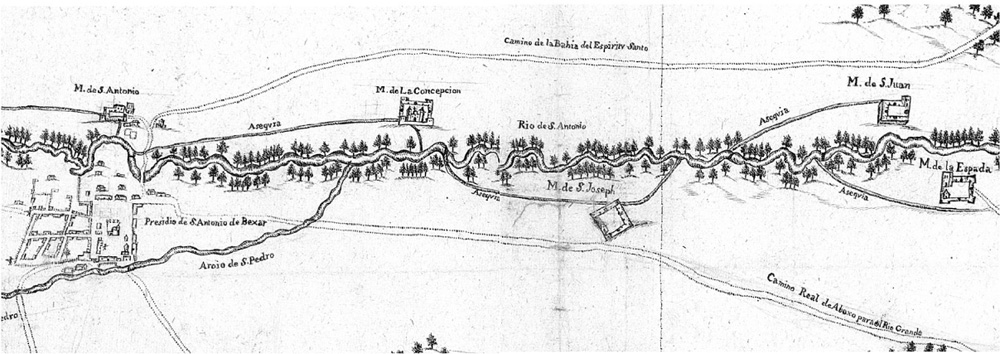

The five missions, military presidio, and civilian villa of San Antonio de Béxar, all located along the San Antonio River. Map drawn by the presidio commander, Luis Antonio Menchaca, in 1764. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, Providence, R.I.

The following year, 1722, Rodríguez and several families from the Ranchería Grande finally accepted the Spanish invitation to form a settlement called “San Francisco Xavier de Nájera.” As in their earlier negotiations, military ceremony continued to make clear that this was an alliance being brokered between Indians represented by Rodríguez and Spaniards represented by Aguayo. The officer corps of Aguayo’s battalion attended the ceremonies and stood witness to the presentation of “an entire suit of English cloth in the Spanish style” to Rodríguez, again emphasizing Spanish recognition of his authority. Spanish officials well understood the military and diplomatic gains to be made through alliance with leaders such as Rodríguez and confederations like that of the Ranchería Grande. In the Yanaguana/San Antonio area, these men would be crucial to Spaniards in the concerted defense needed to curtail the ever-expanding raiding territories of Apaches. Although the Nájera settlement soon disappeared, new ones sprang up along the river when three missions were transferred from east to central Texas in 1731 under new names—San José de los Nazonis became San Juan de Capistrano, San Francisco de los Neches became San Francisco de la Espada, and Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción replaced “de los Hainais” with “de Acuña.” Defense needs grew apace, as the now five Indian villages, one Spanish villa, and one presidio gained still more unwanted Apache attention.12

The spirit and form of mission-presidio complexes reflected their function as shared settlements of Spaniards and Indians coming together for defense and subsistence, even as individual communities—the Spanish villa of Béxar and the five native mission settlements—governed themselves independently. Just as the Spanish families of Béxar had their own gobernador, alcaldes, justicia, and regimiento, so too did each Indian community. Spanish-designated positions for decision making within the new mission settlements resonated with precontact practices. When groups dispersed into individual bands (usually constituting an extended family) for summer hunting and gathering, whoever was deemed the male head of the family led them, and it was only at encampments of multiple congregated bands that “headmen” or “chiefs” assumed leadership. Though Spanish government officials and Franciscan missionaries superimposed Spanish titles of office over already existing lines of native authority, in effect they simply gave notice of their own awareness of interband diplomatic alliances. At San José, for instance, the Spanish meanings of individual titles held by Pampopa headman Juan, Sulujam headman Nicolás, and Pastía headman Alonso meant little; what was important was that the three men continued to share the leadership of their united family bands. The confederated settlement at the mission thereby gave physical form to political alliance.13

Far from mere formalities, the titles and offices accorded male officeholders continued through the century and marked mission governance with the customary kinship organization that had long structured the hierarchy of family bands. Offices tended to remain in the control of certain “old families,” with Xarames dominating at Valero, and positions of gobernador and alcalde alternating annually between Pajalats and Tacames at Concepción. The mix of civic and military officials ensured that Indian leadership ranks would “exercise military and political jurisdiction, and their tribunals impose penalties without shedding blood.” Special clothes for office-holders became commonplace in mission supplies. For instance, Nicolás Cortés, the Xarame mayordomo, and Hermenegildo Puente, the Papanac fiscal (an official in charge of maintaining mission lands), at Valero were singled out with cloaks made of Querétaran fabric, shag garments lined with Rouen linen, and shirts of the same fabric. Guidelines for the missions directed that each year gobernadors would receive new Spanish coats and alcaldes new capes and designated special benches for the men’s use. Such men also remained exempt from obligations of manual labor within the missions, a mark of prestige legally recognized even after mission secularization in 1794.14

Mission and presidio architecture also reflected the coming together of Indian and Spanish cultures. All original buildings—chapels, Spanish and Indian quarters, granaries, and nearby civilian homes and military barracks—were of jacal construction, thatched huts that could be made variously of straw, mud, and adobe. Only over several decades were they gradually replaced with the stone preferred by Spaniards. The jacales, with poles set into the ground and interlaced with flexible straw or grass, plastered with mud or adobe, and roofed with thatch, closely resembled the structures erected by many of the native groups of the region. Native housing in southern Texas usually consisted of round huts built around a hearth area and covered with cane or grass, depending on available construction materials. Further south, in the Rio Grande delta area, groups chose various structures, again depending on their environment, including brush arbors called “ramadas” consisting of support poles and a flat roof made of leafy tree branches, huts built of palm fronds called “toritos,” and houses covered by mats and thatch that were easily transportable. Along the coast, houses were also built around a pole in a circular style and covered with mats or hides—all materials chosen for easy set up, dismantling, and transportation by canoe. Since native construction focused on temporary structures made from locally available materials, it is not surprising that their housing styles predominated at settlement sites where the need for shelter and defense was immediate but residency was not year-round. In the early days, too, Spanish soldiers and missionaries lived just as did the Indians, with presidios following the same patterns as jacal mission settlements, reflecting their own jacal tradition that had been brought with them from the interior of Mexico and that represented a hybrid of Old and New World construction techniques.15

Notably, even as stone gradually replaced jacal construction in church buildings and in missionary and soldier quarters, most Indian quarters remained jacales. Stone construction for Spaniards was a sign of affluence as much as preference, so it is difficult to disentangle native influence on housing from a lack of financial and material resources available to mission residents. The advantage of adobe and stone was greater protection in the case of enemy raids and greater security in the event of fire. At the same time, however, because jacal construction was meant to be temporary, its continued use may have signaled the transitory nature of native residency in San Antonio. Indeed, if natives used the missions in a seasonal manner similar to the way they used their other joint encampments, then only jacal housing would be necessary. It was not until 1749 that fray Ignacio Antonio Ciprián reported that San José Mesquites and Pastías had “houses of stone built with such skill that the mission is a fort.” Xarames, Payayas, Sanas, and others at Valero had stone quarters in 1762, but only by 1772 did all resident Pajalats, Sanipaos, Manos de Perro, Pacaos, and Borrados at Concepción live in stone houses built along the outside wall. Yet, that same year, stone housing had only begun to be built at San Juan de Capistrano and San Francisco de la Espada and would never be completed for all resident Indians. At Nuestra Señora del Rosario and Nuestra Señora del Refugio along the coast, jacales remained the only shelter ever used by Karankawas, Cocos, Copanes, Cujanes, and Coapites during their periodic visits. That Ciprián used “fort” to describe San José houses might well explain the shift to stone as defensive strategy rather than Spanish preference.16

Stone came to dominate, but mission settlements maintained the physical feeling of native encampments and living spaces—even the church structures. As stone chapels arose under the direction of Franciscans, Indian residents influenced their decoration. Though the major forms and symbols found in the architecture, carvings, and decor of mission chapels remained Spanish, the Pampopa, Xarame, Tilpacopal, Pamaque-Piguique, Payaya, Ervipiame, and Pajalat men listed among the recorded masons, carpenters, and blacksmiths interpreted them as they built. Carvings at Valero, Concepción, and San José reflected a “fusion of Spanish and Indian tradition,” with “Christian symbols or the classic orders of Greco-Roman buildings” transformed by native artisans. Multicolored murals painted in the original church at Rosario exhibited a free-flowing design of “scored half circles or lunettes” and flora resembling yucca plants found within Karankawan coastal territories, expressing the natives’ imaginations reproducing images taken from environments they knew so well.17

Painted decorations in the form of birds, flowers, chevrons, circles, simple waves, and continuous, vinelike lines attributed to Indian workmanship that adorn the walls of the chapel (now confessional room) at Mission Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción de Acuña. Courtesy of the Texas Historical Commission, Austin, Texas.

Although Spaniards controlled much of the structure for this new form of settlement, native usage followed precontact patterns. Just as they had moved between shared and unshared encampments of their own, so too did they come and go from Spanish missions in accordance with subsistence needs, diplomatic alliances, and kinship obligations. The same loosely allied bands that gathered together at confederated settlements did so at missions. From San Juan Bautista in northern Coahuila to San Antonio de Béxar in Texas, native families joined missions nearest their hunting ranges and long-used encampment sites. Often a mission represented one or more particular confederacies, as allied families entered missions in both Coahuila and Texas as groups. In turn, missionaries identified and named each affiliation after the group who had numerical dominance within it, such as the Terocodame and Xarame confederacies of Coahuilteco speakers at San Francisco Solano, the Sana confederacy of Tonkawa speakers at San Antonio de Valero, and the Pajalat confederacy of Coahuilteco speakers at Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción.18

At the same time, the independence of kinship groups, even under the leadership of confederation headmen, also remained intact. When families made the decision to join native or mission settlements, they did so in family units. Missionary reports regularly recorded that headmen came to the various missions bringing with them their wives and children or even larger family groups. Once they were inside the mission settlements, housing patterns seem to have reflected these extended family groupings, such as the eight larger units divided by band at San José. One Tacame family group tried out several missions, shifting from San José to Espada to a native settlement on the Colorado River and then back to San Antonio at Valero before finally settling at Concepción, where they became a leading family in mission governance. Others knew what they wanted ahead of time. When allied groups of Mayeyes, Yojuanes, Deadoses, and Bidais first discussed joining a mission, fray Mariano de los Dolores y Viana asked them to visit San Antonio, but they explained that the Indians there “were not related to them, nor did they come from their locality, and for that reason they could not live with them.” Insisting instead on a mission settlement within their own territories, they said that “they could not move so far away from their relatives . . . nor could they leave their neighboring and allied nations because they were all intermingled and had intermarried.” The power of kin-based requirements resulted in the establishment of the San Xavier missions in the 1740s in their lands along the present-day San Gabriel River, east of San Antonio.19

Just as Indians came to missions in family groups, so too did they leave that way. As fray José Francisco López reported, “one after another they have followed their kin.” Thus, the Spanish settlements held no more sway than other settlements visited during seasonal migrations around San Antonio and among relatives and allies spread throughout hunting territories all the way down to Coahuila. Fray Antonio Margil and fray Isidro de Espinosa lamented that too many Indians “live on their ranches and do as they wish. . . . There is no force able to subdue them and oblige them to live in a pueblo under Christian management.” In a 1737 report, fray Benito Fernández de Santa Ana had to admit that in the month of August Mission Espada had “very few” present, Mission San Juan de Capistrano stood “abandoned,” and Mission Concepción “runaways” had fallen victim to Apache raiders during their migrations. Three years later, writing another report on the state of the missions, Fernández de Santa Ana lamented, “It is the exception who does not flee to the wilderness two or three times and so far away that sometimes they go so far as 100 leagues away.” What missionaries often characterized as “running away” represented customary migrations between encampments of kin groups living in much the way they always had.

Ironically, after judging Indians to be without a sense of “family,” missionaries confronted undeniable family cohesion as families united in acceptance or rejection of mission residence. In 1753, five families of Pamaques, Paguacanes, and Piguiques left San Juan de Capistrano to rejoin relatives at Mission San Francisco de Vizarrón near the Rio Grande in Coahuila. They soon intermarried with several Vizarrón residents, and the increased kin ties strengthened the families’ refusal to return to Capistrano when the two missions began fighting over jurisdiction of the family groups. Thus, they successfully used the unions to stay together and to remain at the settlement of their own choosing. In turn, the extended nature of these families often represented kin ties of intermarriage rather than multigenerations of long duration. When fray Jesús Garavito conducted a census of Indians at Refugio before they left for their winter camps on the coast, he listed three groups—Karankawas from Rosario, Cocos from Rosario, and Karankawas from Refugio, each with its own “captain,” respectively Manuel Zertuche, Pedro José, and Diego—representing three extended families. A Rosario census from the year previous listed Manuel Zertuche as a twenty-five-year-old captain with a twenty-year-old wife, María, and their four children: Margarita, seven; Ysabel, four; José Guadalupe, three; and José María del Pilár, one. The youth of these families showcased the hardships of subsistence, raids, and disease shaping their lives. Not surprisingly, as Rosario collapsed in the early nineteenth century, many resident Indian families chose to move to Refugio “in order to be with those they are related to by marriage.”20

Family bands’ coherence also had the power to destabilize mission settlements. The encampment at San Francisco Xavier de Nájera lasted for only four years, and it was known during that brief period as the Ervipiame “barrio.” The number willing to stay year-round steadily languished over those years, and by 1726, the twelve remaining residents, including Juan Rodríguez, Margarita, and their children, moved to Valero. San Francisco Xavier de Nájera shut down. But Ranchería Grande did not. Mayeyes, Yojuanes, and various other Tonkawa speakers maintained their shared encampments and continued to be known as the Ranchería Grande. In turn, it continued to serve as a destination for independent families, refugees who left missions, and those who moved between the two kinds of settlements—native and Spanish—according to the seasons of the year. Ervipiames, Payayas, Cocos, and Mayeyes all appear on lists of “fugitives” from Valero, and missionaries attributed the nearby presence of the Ranchería Grande as both a constant lure and an asylum for any Indians who wearied of mission regimens or short supplies. As early as 1727, when Pedro de Rivera passed through the region, he recognized the Ranchería Grande as a “republic” that offered safe haven to Indians from other mission settlements, especially as the “republic” refused to give up “escaped” Indians to the Spaniards who came to encourage or coerce their return to San Antonio.21

Three later missions established along the San Gabriel River in the 1740s attempted unsuccessfully to draw the Ranchería Grande residents, as well as the Bidais and Akokisas, into an alliance, but they failed within ten years. Keeping a focus on Akokisas in the 1750s, Spaniards built another complex along the Trinity River, with the Presidio San Agustín de Ahumuda and the Mission Nuestra Señora de la Luz (together called “El Orcoquisac,” from “Orcoquizas,” another name for Akokisas). Spanish officials hoped an Akokisa alliance might help to forestall intrusions of illicit French traders among Indian bands living along the lower Neches, Trinity, and Brazos Rivers. To offset French trade, Spaniards thereby wooed Akokisas and, by extension, their Atakapa allies and kinsmen with promises of weekly supplies of beef and corn. Yet, when Spanish transportation lines proved unreliable, the Akokisas and Atakapas simply cut visits to the missions from their customary seasonal movements between fall/winter aggregations on the coast and spring/summer dispersals inland. When the marqués de Rubí traveled through the province on his 1766–68 inspection tour, he added the mission to his “empty and abandoned” list, while noting populations of Aranamas, Cocos, Mayeyes, Bidais, and Akokisas living in shared and independent encampments in numbers far greater than those ever counted in mission censuses.22

Along the coast, families of Karankawas, Akokisas, Atakapas, Bidais, and Aranamas found the least reason of any Indians to reside with Spaniards during their customary seasonal migrations. Early on in 1719, Martín de Alarcón reported that “proud” Aranamas rejected Spanish overtures, saying that they were “as brave as the Spaniards,” thereby implying that they did not see any need for alliance with the intrusive Europeans. The security of their encampments in coastal marshes and barrier islands—rather than a valor differential—set these groups apart from those in the San Antonio area. That left only supplementary subsistence resources to attract coastal natives into contact with Spaniards—which was not often enough. In 1723, at the complex of Mission Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga and Presidio Nuestra Señora de Loreto (together known as “La Bahía”), the native community collapsed after only a two-year existence due to a complete Karankawa desertion. Spaniards attempted another coastal venture at Mission Nuestra Señora del Rosario in the 1750s, but all too soon it ended in failure as well. In 1767, Rubí declared that any number he might attempt to offer as a count of the Cocos, Cujanes, Karankawas, and Aranamas reputedly resident again at Mission Espíritu Santo was “less certain, for they frequently desert and flee to the coast.” Moreover, he implied, the count of converts was zero, since “it is evident that the mission is composed mostly of pagans.”23

Most missionaries’ understanding of Karankawa movements between mission and coast remained limited to responses to conditions at the mission—food shortages, conflicts with soldiers, or sheer stubbornness. Yet, visits and periodic residence at missions did not represent “random or haphazard events,” as the missionaries believed, but rather strategically designated times in seasonal rounds when mission offerings would be most useful. Since missions like Espíritu Santo, Rosario, and later Refugio were built on sites of the Indians’ spring and summer hunting camps in the coastal plains and prairies, periodic visits to the Spanish institutions fit naturally into old subsistence patterns. Fray José Francisco Mariano Garza, for instance, wrote to Governor Manuel Muñoz one summer that as Karankawa family bands began to shift inland to spend the season at their prairie camps, they dropped by Refugio, received a supply of tobacco, and promptly left to gather prickly pear at Copano Bay and along the Aransas River. Karankawa family bands stayed to hunt in the vicinity of the missions during those months and then returned to their fishing camps along the coast in the fall and winter. Missions functioned within their regular subsistence patterns as just another ecological resource. Before bringing their families to the missions, headmen and warriors even made preliminary inspection visits to ensure sufficient food supplies were on hand. “All of them, and especially the chief referred to [Fresada Pinta],” Garza complained, “have come with the selfish intention of seeing if the provisions of foodstuffs and clothing which they say Your Lordship promised them are in the mission yet.” Equally, though, the missions seem to have been mere camping sites, as archaeological remains of whitetail deer, alligators, turtles, ducks, herons, turkeys, beavers, fish, and freshwater mussels as well as wild plants, such as mesquite beans, seeds, and pecans, demonstrate the variety of foods that coastal Indians brought into Rosario, Espíritu Santo, and Refugio themselves. It was only in the 1790s that missionaries seemed to accustom themselves somewhat to Karankawa movements and simply kept track of Indian families at Rosario and Refugio, taking censuses before they departed each year.24

The ravages of European diseases also encouraged regular residential and subsistence movements of Indian families. As happened throughout the Americas, once native peoples congregated in or near Spanish settlements, they put themselves in reach of epidemics that could strike in particularly pulverizing fashion, returning every decade to decimate new resident populations. Indians lost the isolation and thus protection afforded by the small size and mobility of hunting and gathering bands when they joined others in settlements where diseases swept through with all-encompassing and thus devastating effect. Epidemics in turn precipitated flight back to native settlements far from the specter of death. Newcomers from regions increasingly distant from Spanish contact then arrived and became the next group to fall victim to the next wave of disease.25

In San Antonio, epidemic outbreaks occurred in 1728, 1736, 1739, 1743, 1748, 1749, 1751, 1759, 1763, and 1786. Thus, although mission counts indicated fairly steady population numbers at the San Antonio missions from 1720 to 1772—sometimes listing an annual total of over one thousand people for all five missions between 1745 and 1772—it was only an appearance of stability. The numbers did not reflect the continuity of a self-reproducing community (through steady birthrates and/or declining death rates) but rather the constant recruitment of new residents by Spanish church and state officials. Exacerbating the losses from disease, infant mortality and female mortality in childbirth were so high that two-thirds of children born in the missions died before reaching three years of age. Life spans shortened by disease and ill health further decreased fertility rates. The mean age of Indian populations in the San Antonio missions was roughly twenty-six years old. It was not until the 1780s that an increase of children in the population, a decrease in the number of widows and widowers, and an increase in the median size of families from 2.7 to 3.5 heralded gradual stabilization of Indian populations associated with the Spanish community.26

Such demographic factors meant that native populations in San Antonio consisted of a constantly shifting and predominantly young population for whom daily life was fraught with instability due to high mortality for all ages. As late as 1789, fray José Francisco López recorded that despite the age of the missions, the Indian residents were mostly children of “uncivilized” Indians. Thus, a majority of those Indians who interacted with missionaries over the century did not begin life in mission settlements, maintained the ties and communal practices of the families into which they had been born, and viewed relations with Spaniards as a new and unfamiliar experience.27

Within that destabilized setting, where daily survival was a struggle for Spaniards and Indians alike, mutual need served to maintain a balance of power, and day-to-day subsistence and defense earned the greatest attention from Indian headmen and Spanish leaders. The need was clear even to officials in Mexico City. In 1733, judge advocate Juan de Oliván Rebolledo advised the viceroy that an alliance with the Indian peoples of central Texas, who could augment Spanish forces with their own, would be essential if Apaches were to be compelled to make peace. Spanish and Indian peoples thereby each played a role in the security and subsistence of the community—Indian warriors with their skills of hunting and defensive combat, and their Spanish counterparts with material supplies as well as fortifications, guns, and ammunition that supplemented the warriors’ lances and bows and arrows. And security came first, as Apaches stepped up their raids against San Antonio communities in often unrelenting fashion from the 1720s until the 1750s.28

Spanish contributions to fortifying their communities indicated that joint Indian-Spanish settlement represented first and foremost a defensive alliance for mutual protection. Citing the vulnerability of the San Antonio area to Apache attack, the marqués de Aguayo was the first to order fortifications built in the form of a presidio, “with four baluartes [bastions] proportioned for a company of fifty-four men.” Yet, in the eyes of missionaries and Indian residents, the presence of a presidio did not provide sufficient defense for the individual mission settlements surrounding it, because as the missions took form, their own defensive architecture and armaments competed for importance with chapels and church furnishings within the mission grounds. Stone walls to enclose and protect jacal housing always came before the building of stone churches.29

By midcentury, San José’s outer wall boasted parapets, battlements, and tower bastions at all four gateways, from which sentinels kept guard. A granary and well were located inside the walls in case of siege, and the trees and brush that stood outside the walls were cut down to safeguard against surprise attacks. In addition, fray Juan Agustín Morfi noted that loopholes had been made through the outer walls into the adjoining Indian quarters so that warriors could fire guns from cover if the mission were stormed. The San José armory held guns, bows and arrows, and lances with which to equip the warriors, and a plaza de armas (military plaza) provided space for the warriors’ military drills as well as bow and arrow and musket practice. On Saturdays, during processions of the Feasts of Christ and of the Virgin Mary, armed warriors stood guard and sentinels on horseback stationed themselves outside the ramparts to ensure security.30

Meanwhile, just a league and a half away, San Antonio de Valero had stone walls, fortified doors, and a watchtower with loopholes for three swivel guns (cannons), along with muskets, shotguns, powder, and ammunition for the warriors who defended the mission community. Concepción, Capistrano, and Espada between them had an assortment of cannons at each gate, swivel guns, “slingers,” and general arms and ammunition to aid warriors in defense of their walls as well. Despite missionary claims for the primacy of religious conversion and social “hispanization,” these were in fact embattled settlements marshalling the strengths of all inhabitants for a united defense.31

Aerial view of Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo, c. 1944, indicating both the size and defensive structure of the mission. Courtesy of the San Antonio Conservation Society Foundation, San Antonio, Texas.

That is not to say that Franciscans did not attempt to use the labor demands within mission communities for “civilizing” purposes. Missionaries had a threefold purpose in trying to divide labors between Indian men and women residents at missions. First, although missions received financial support from the Crown, each had to be largely self-sustaining. Second, self-containment of the mission community aimed to keep Indian peoples safe from what Franciscans believed to be the potentially detrimental influences of “unsavory” Spanish settlers. Maintaining a distance from the presidial and civil populations of nearby settlements required that missions provide their own skills, crafts, and services. Thus, the native workforce had to be capable of providing their families with food and sustenance. Third, Franciscans hoped that in the process of securing the mission communities’ subsistence, they could teach Indian residents labors that ideally would serve them well once the missions were secularized and the Indians became citizens of Spanish society. “To make this method work,” fray Mariano de los Dolores y Viana wrote, the Indians must “work their own fields, open up their irrigation ditches, build their houses and churches, breed cattle, protect and maintain them; eat and dress themselves and have the necessities for civil and rational style of living.” Attaining these skills and industry would make them “gather more readily in the new Pueblos, embracing our Religion and becoming subjects of His Majesty,” according to Commandant General Pedro de Nava. Instruction in work roles commensurate with Christian living, church and state officials asserted, would enable Indian men to provide for themselves and their families and teach them to be respectable, contributing—and manly—members of Spanish society.32

Because of agriculture’s social and cultural importance within Spanish society as well as its economic importance to the mission’s food supply, farming was key to the ideology and mores that were to be taught Indians—particularly Indian men—through labor. Both Old and New World Spanish societies based their socioeconomic systems on land ownership and cultivation. Land tenure formed the principal basis of wealth, prestige, social hierarchies, and political rights among Spanish men. In the attempt to make native labor practices conform to Spanish norms, Franciscans wanted to structure labor systems at the missions around clear divisions of gender that located men in the fields and women within the confines of mission living quarters.

These divisions’ importance rested in both the spatial location of male and female labor and the meaning of the work itself. For men, gendered divisions of labor reflected what Spaniards understood to be the proper distribution of authority and power within a family. Thus, to the missionaries, women’s seclusion and men’s control of farming would firmly establish Indian men as patriarchal heads of household and family providers. In the ceremonies surrounding the initial establishment of mission settlements, Spanish officials ritually called upon Indian men to assume new labor routines and to pass them down to their sons in accordance with divine law and patriarchal custom. Captain Juan Valdéz’s description of the formal promises elicited from Pampopa, Pastía, and Sulujam male leaders at the 1720 founding of the San José mission outlined this commitment: “Not only did they agree to dig their irrigation ditches and cultivate their lands, but also promised to teach their sons to do the same, insisting that they want to obey the law of God.” In this spirit, missionaries, or more likely civilian and military overseers, sought to teach Indian men “how to plant, how to cultivate the crops, and how to harvest them.” A diversity of tasks associated with running mission farms and ranches also fell to Indian men, including irrigating, weeding, gathering in seeds, tilling and plowing fields, mending fences, burning cane, working fruit orchards, herding and branding the mission cattle, horses, and oxen, and herding and shearing sheep.33

While men were to work in agricultural fields, women were to learn to remain secluded from them. The Spanish emphasis on the domestic seclusion of women in the home concerned control of female sexuality. Early modern European ideas about women’s “natural” susceptibility to sinful temptation led many in Counter-Reformation Spain and New Spain to believe the “enclosure” of women to be a protective measure for ensuring female chastity and family limpieza de sangre (purity of bloodlines). Conceptions of male honor thus depended upon the supervision of female sexuality. In this way, the household became a “sacred” male domain where the property of men—wives, daughters, sisters, and mothers—needed to be protected. Within the home, men ideally guarded the purity of their female family members and, in turn, the honor of their name and lineage. Keeping Indian women out of the fields reinforced not only women’s sexual seclusion but also, simultaneously, men’s role as family patriarch and provider. As one mission manual explained, “the women should be in their homes grinding grain and preparing the meals for their husbands and not be going through the fields doing men’s work.”34

The necessities of daily life regularly thwarted missionary ideals, however. Resident male populations rarely could meet all the labor needs required by mission farms and ranches, and women labored side by side with their husbands, brothers, and sons, even though missionaries wrote reassuringly to their superiors that women did so “only when necessity demands it because of the scarcity of men.” Claims concerning “proper” gender divisions of labor among mission Indians, especially protections for women, reportedly reached the highest levels of Spanish bureaucracy. In 1768, for example, a military captain at La Bahía found himself caught in the middle of struggles between presidio and mission personnel at Espíritu Santo over the work assignments of Indian men and women as well as over Indian complaints of excessive work demands. In his attempt to sort out the controversy, Francisco de Tovar cited viceregal authority, asserting that “His Excellency [the viceroy] does not want the [Indian] women to work on those occupations not proper for women.”35

If they could not always keep women out of the fields, Franciscans tried to emphasize that their labor within mission quarters was the primary and most identifiable work of women. Missionaries tried to structure women’s labor by designating certain tools and provisions “for women,” locating their work within the living quarters of the missions, and even determining the foods that Indian women might cook. At Mission San José, each home in the Indian quarters came supplied with stones for grinding corn (metates), grills for making tortillas, water jars, and adjoining patio areas with ovens “reserved for the private use of the Indian women.” Inventories show that every mission supplied women of Indian families with pots, earthenware pans, griddles, kettles, dippers, and various other “domestic utensils.” The material limitations of mission supplies might sometimes require the women to cook together communally but still allowed the construction of an ideological domain of female labor and activity in service to their husbands and children. Mission dictates further determined that it would be the women who assembled regularly to receive rations of salt, fruit, beans, vegetables, and meat, marking their responsibility for food preparation even as they were nominally prohibited from its cultivation.36

Mission plans also purported to train Indian men and women in distinctly gendered skilled labors and crafts. Inventories documented that every mission in the San Antonio area included rooms with spinning wheels where Indian women spent hours cleaning, drying, carding, combing, and spinning cotton and wool. Then, once male weavers who were hired from the nearby Spanish villa had woven the cloth, all the members of a family received their ration so that their wives or mothers could sew clothes for them. Beyond spinning and sewing, all other skilled labors were supposedly reserved for men, who were to learn mechanical trades such as blacksmithing, carpentry, and masonry work. Yet, it was not until the 1770s that Indian men began to appear on lists of trade specialists in mission records and that fray Juan Agustín Morfi could write that Pampopa and Mesquite men of San José “know how to work very well at their mechanical trades.” For most of the century, Spanish citizens from the nearby villa assumed all skilled positions of blacksmith, carpenter, stonemason, tailor, shoemaker, candlemaker, cañero (in charge of San José’s sugar mill), and vasiero (in charge of breed herds of sheep and goats). This time lag likely reflected the rarity of those skills and the lack of demand for them among the Spanish as well as Indian populations.37

These labor guidelines illuminate what Franciscans envisioned for their missions but reveal little of the day-to-day reality in the San Antonio communities. Petitions asking that at least one soldier be stationed at each mission—not as a defender but as an overseer, “so that respect for him will make the Indians do the work necessary for maintaining civilized life and the holy Faith”—indicates the futility of missionary efforts to require Indian residents to pursue work not of their own choosing. That appeared particularly true when the work challenged native gender divisions of labor. Many men and women simply left, traveling back to the community life and work they had known previously. “Returning then to their old means of sustenance,” fray Dolores y Viana bitterly wrote, Indians “leave the missions and gladly live in the woods as before.” Upon arrival back in native settlements, Toribio de Urrutia feared, many “runaways” told family and friends that in the missions they had been made servants of Spaniards.38

Many others did not abandon mission settlements, but neither did they accept labors charged them by Franciscans. Fray Dolores y Viana noted that Indian men in the fields worked so carelessly “with the usual slowness, characteristic of their innate indolence,” that “it is necessary always that some Spaniard direct them; what could be done by one person is usually not done by four.” Men also simply left for short periods of time as a break from work. In fact, Indian men proved to be such “enemies of work” that “on many occasions they arm themselves in order not to be forced to do anything for long periods of time.” Franciscans read the Indian men’s refusal to carry out the labors requested of them as signs of “laziness.” As fray Manuel de Silva explained, “It takes great effort to make the Indians work, for idleness pleases them much more. But this is contrary to civilized life, and little by little I manage to get them to work moderately.”39

Missionaries ignored or were incapable of perceiving the gendered meanings behind Indians’ labor choices, however. Despite their own observations, they remained blind to the fact that Indian men refused to do only certain kinds of work. As one Franciscan recorded, “any work, other than hunting and fishing, was excessive to the Indian male,” while another argued that they wanted nothing more than to hunt wild game and wage war. Indeed, men did work, but it was work consistent with their own communal patterns. Indian peoples of southern and coastal Texas who made up the majority of mission populations generally practiced little if any plant cultivation, living instead by hunting, fishing, and gathering. For Indian men, missionary labor demands cut into the time necessary for the appropriate male labors of hunting and fishing. Presumably, too, they might have asked: did not agricultural production represent one of the contributions that Spaniards were supposed to bring to the mission-presidio complex alliance?40

While Indians’ very conception of maleness rested in hunting skills, women’s work had customarily been tied to plant-based subsistence and craft production, which apparently translated more readily into Spanish labor roles. “The women are given more to work than the men,” fray Manuel de Silva asserted, “and are most always busy” spinning cotton and wool, making pots, earthen pans, and other items of clay, which they traded or sold to Spanish women living nearby. Tellingly, in comparison to men, women’s work skills and responsibilities within the divisions of labor of family and band matched those of missionary ideals. The mortars and pestles of native cultures closely resembled in form and use the metates and manos given to women to grind corn in the mission complexes. Harvesting agricultural crops may have echoed the gathering of berries, roots, and other plant foods customarily done by women. Similarly, native economies already assigned women responsibility for making clothes from animal skins, so women simply added cloth to their supplies of chamois and bison hides. Cloth did not replace them, though. Fray José de Solís noted that bison hides still shared space with cotton and wool blankets on beds in the Indian quarters of San José in 1767. Even lessons in weaving cloth would have been familiar to Karankawan women who erected and moved the portable dwellings that often included woven reed or grass mats. Thus, the domestic chores that missionaries believed they were teaching in accordance with “civilized” life differed little from the work roles Indian women brought with them to mission settlements.41

Native gender patterns predominated, whether the Spaniards fought them or encouraged them. In addition to crossovers between Indian and Spanish work regimens, traditionally defined native labors also played a crucial role in day-to-day subsistence within mission communities. The product of men’s hunting and women’s gathering continued to enliven both their living spaces and their diets. Disappearances called “flight” by missionaries in reality reflected the freedom with which Indians came and went from the missions in pursuit of their own socioeconomic activities. Though mission crops and cattle herds offered steady food supplies in San Antonio (though not at Espíritu Santo, Rosario, or Refugio along the coast), Indians continued their own subsistence technologies throughout the eighteenth century. In doing so, they not only supplemented and diversified the foods from mission farms and ranches but also maintained familiar gendered work roles and statuses. Indians left the San Antonio missions in the summer so that women could collect prickly pear fruit and men hunt deer and bison. Women at Concepción had a “habit of leaving the mission toward evening to eat tunas [prickly pears], dewberries, cuacomites, sour berries (agritos), nuts, sweet potatoes (camotitos), and other fruit and roots from the field.” Faunal remains at San Antonio mission sites highlight Indian preference for diets of indigenous wild game, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians (despite ready supplies of beef cattle)—proof that choice, not necessity, guided their selection of the bounty of men’s hunts. At San Juan de Capistrano, archaeological evidence of the diets of Pajalats, Pitalacs, Orejones, Pamaques, Piguiques, Chayopins, Pasnacans, and Malaguitas provide further indication of intermittent residence at the mission and continued reliance on coastal foodstuffs.42

More evidence of the prevalence of native gendered divisions of labor in mission communities lies in Spanish complaints about the difficulty in cultivating gardens and orchards because Indian women kept “gathering” fruit before it had ripened. And Indian men, even when they relied on mission cattle herds for their meat, transferred native butchering techniques to the domesticated animals. In similar spirit, in the coastal missions that depended not on agriculture but on cattle ranching for mission food supplies, missionaries recorded that Karankawa men—with better horses and arms than the Spanish vaqueros hired to care for the herds—arrived in bands of ten to twelve to “hunt” the cattle during the spring and summer. Such Karankawan hunting expeditions used mission cattle as a primary substitute for diminishing bison herds. As fray Antonio Garavito at Rosario lamented, “I fear that if the Indians from Rosario do not have enough to eat in their mission, they will wander about doing damage. . . . the cattle will be destroyed, the herds driven off, the tame horses taken, and nothing will remain that they will not steal.” On the other hand, missionaries increasingly visited Karankawa bands in their hunting camps at intervals over the summer, and after enjoying their hospitality, one named fray José María Sáenz regularly brought back wild game and fruit to Refugio to liven up even the missionaries’ diets. In 1805, Francisco Viana, the commander of La Bahía presidio, reported that local Indian populations continued to spend most of the year in their own territory, coming in periodically to receive blankets and other gifts from the missionaries and to trade the products of their hunting and gathering—such as nuts and bear lard—at the presidio. In support of their independent economic pursuits, Indian warriors even received musket balls and gunpowder from the Franciscans. In short, Karankawas and others used the Spanish institutions as a resource and buffer attuned to their own economic needs and gendered work customs.43

Archaeological finds at mission sites also include a profusion of arrow points, stone tools, and pottery—testifying to the native technologies and gendered divisions of labor that defined work there. The presence of arrow points shows the continued pursuit of traditional hunting skills by Indian men concurrent with their adoption of guns. Warriors appear to have preferred lithic arrow points and projectile points, though they sometimes incorporated metal and glass into their manufacture as well. A gradual shift from Perdiz to Guerrero points indicates that shared encampments with new Indian (as well as Spanish) neighbors influenced adaptations among diverse native manufactures. At the same time, they also transformed chert chips and flakes into gun flints, adapting their own manufactures to Spanish muskets. The presence of lithic blades and scrapers demonstrates that women too continued to choose chipped stone tools for processing animal and plant materials hunted and gathered by their family members.44

Indian preference for their own crafts and technologies ensured the persistence of the gendered divisions of labor that had long produced them. In the San Antonio missions, men hunted with bows and lithic arrow points made by women, while women tanned the hides from that hunt and made ceramic bowls, candlesticks, pots, jars, pipes, and whistles with animal bones marked by native decoration. Native manufacture of ceramic pottery in San Antonio—usually a craft production of women—continued virtually unchanged with bone-tempering, coil manufacture, clay and paint colors, polishing and burnishing with river pebbles, and water-proofing methods characteristic of precontact technologies. Ceramics found in mission contexts called “Goliad” ware did not differ from pottery at late pre-Hispanic sites identified as “Leon Plain” ware. Meanwhile, untempered or shell-tempered ceramics made of sandy clay with asphaltum decoration found at Rosario and Refugio and called “Rockport” ware reflected coastal workmanship like that of the Karankawas. Women also continued to make ornaments and beads from shell and bone or used trade beads given them by missionaries or other Indians to fashion into their own jewelry. Interestingly, archaeological digs have uncovered examples of Indian-interpreted rosaries made from trade beads restrung in combination with crucifixes.45

Unlike their contrasting notions of the sexual division of labor, Spanish and native ideas of manliness meshed when it came to defending their communities in the San Antonio area. The need for fighting men enhanced Indian men’s responsibilities and made them essential to the survival of all residents. Within the context of escalating warfare brought about by the dual invasions of Spaniards and Apaches since the seventeenth century, fighting had served as primary employment for men, structured social and economic hierarchies, and provided the grounds for choosing both civil and military headmen. These functions continued unchanged within the mission-presidio complexes. Over the eighteenth century, the San Antonio presidial company, like many across the northern provinces of New Spain, suffered debilitating shortages in men and armaments and thus joined forces with civil as well as mission populations for offensive and defensive measures against enemies.46

In fact, Indian men by far made up the greatest percentage of fighting men in San Antonio, giving them plenty of opportunity to meet customary standards of manhood. As discussed earlier, church officials in the San Antonio and La Bahía areas kept armories at the missions with guns, ammunition, lances, bows, and arrows ready in case of attack. Many Indian men became trained fusileros (fusiliers). During a 1767 inspection tour of the Texas missions, fray José de Solís paid strict attention to each community’s defensive readiness, counting 110 warriors among the population of 350 at San José, 45 of whom used guns while the remainder still preferred bows and arrows, spears, and other native-made weapons. The military force at San José alone outnumbered the San Antonio de Béxar presidio force more than two to one. Similarly, at Mission Espíritu Santo, Solís found 65 warriors, 30 armed with guns, and 35 armed with bows and arrows, spears, and boomerangs. Farther south, fray Juan de Dios María Camberos counted 400 Cujane, Coapite, and Copane men at Rosario able to bear arms, and to that number, he argued, could readily be added those warriors among the Karankawa proper. During that 1767 inspection tour, fray José de Solís noted in detail the military parades of Indian warriors through plazas de armas that took pride of place in welcoming ceremonies put on by each mission. At Espíritu Santo, Indian men twice provided formal displays of their defensive capabilities in honor of Solís’s visit. In these instances, 40 armed Indian horsemen assembled to parade in double file and then continued their demonstrations with symbolic battle skirmishes. Such military drills confirmed the importance and status of Indian warriors within mission communities. Fray Solís gained personal appreciation of their valor when two warriors from Espíritu Santo who were escorting him on to the next mission saved his life when Aranamas attacked the party.47

Defensive demands increased in importance as horse and cattle herds at missions, presidios, and private ranches grew and in turn attracted Apache and later Wichita and Comanche raiding parties. Fray Dolores y Viana recorded that it was only the presence of Indian warriors from the mission settlements that ensured Apache raids were repelled in 1731. “They were the ones who up till now in all the campaigns and uprisings have come out against the Apache tribe, followed their tracks and spied upon their ranches with great loyalty and such manly spirit that without them not even the Spaniards would have entered,” Dolores y Viana argued, “and even if [the soldiers] had, they would not have been victorious or saved their lives; they would have retreated in shame.” On June 30, 1745, over 100 Indian warriors from Concepción and Valero routed the largest raiding party ever seen in San Antonio, 350 Lipan and Natage Apaches. When a Spanish lieutenant ordered soldiers and warriors to turn back after pursuing Apache raiders into their own lands without overtaking them, an Indian leader protested, reputedly saying, “Sir, you go back to watch the presidio, for I will go with my men to look for the Apaches.” Failing to spur the Spaniard to action, the Indian governor and his men returned with the soldiers “much ruffled” at neither gaining their objective against Apaches nor receiving the credit due them “after they had saved the presidio and the villages from complete destruction, as all acknowledged.”48

Increasingly, Indian warriors also offered their services as military escorts for cargo trains to and from Coahuila as Apache raiding routes shifted southward. In 1750, officials at the newly established missions in east-central Texas along the San Gabriel River were thrown into serious disarray in the midst of a series of Apacheraids. Skilled Bidai, Akokisa, and Deadose horsemen and riflemen chose to leave Mission San Ildefonso, taking their families with them, when they were exhorted by an allied confederacy of Ais, Hasinais, Kadohadachos, Nabedaches, Yojuanes, Tawakonis, Yatasis, Kichais, Naconis, and Tonkawas to join a general campaign against Apaches. Despite promises to return in two months, the warriors and their families remained absent almost eighteen months while the men’s military commitments took precedence over settlement ones.49

When the Indians of south-central Texas agreed to cast their lot with Spaniards in joint mission settlements, Spanish officials and missionaries alike often portrayed them as men who checked their valor at the mission door. The idea of missions as institutions through which to “conquer,” “subdue,” “pacify,” and “subjugate” Indians was so firmly locked in their imaginations that they refused to acknowledge the reality of their situation. Despite such stereotypes (more often found at higher levels of administration), in day-to-day life the warriors at the San Antonio missions were crucial to the defense of the mission-presidio complexes, and the Spaniards knew it. In a 1744 letter to Viceroy conde de Fuenclara, Governor Tomás Felipe Winthuysen praised the Indian men at Valero, describing them as “among the most warlike and skillful in shooting arrows.” As a member of the 1766–68 Rubí inspection team sent to evaluate defensive capabilities across the northern provinces, Nicolás de Lafora argued that presidial guards stationed at the San Antonio missions were unnecessary because the one hundred “bow and arrow men” living there put the missions “beyond reach of any local or outside attack.” When Hugo O’Conor, the commandant inspector of presidios for the northern frontier, requested assessments of the province of Texas’s capability to muster forces against a feared invasion by allied Wichitas and Comanches in the 1770s, three different military officials—Rafael Martínez Pacheco (twenty-year veteran and commandant of the El Orcoquisac presidio), Luis Antonio Menchaca (thirty-year veteran and commandant of the Béxar presidio), and Roque de Medina (adjutant-inspector of the interior presidios)—all counted mission Indian warriors as critical components of the “forces of the province.” O’Conor responded with directives that Indian men at the five San Antonio missions receive 132 pounds of gunpowder, the same provisions allocated to the Béxar presidial company.50

Although the necessities of daily life kept Spaniards and Indians alike focused on subsistence and defense and ensured the continued value of native-defined divisions of labor, another potential arena for conflict between Spanish and Indian communal patterns emerged from Franciscan efforts to use the mission settlements to achieve the social “civilization” of Indian residents. Their attempted reforms centered on family and sexuality as they endeavored to make Indian men and women conform to Franciscans’ definitions of Christian morals and Spanish mores. Here, they confronted the power of different patterns of kinship, which with constitutive relations and behaviors for men and women, were the central organizing principles of Indian communities in south and central Texas. With bands that each represented an extended family, kin relations defined not merely social units but political units, economic divisions of labor, and leadership and authority hierarchies. Therefore, when missionaries sought to influence Indian conceptions of “family” and its corresponding roles for men and women, they challenged constructs fundamental to their cultures and polities, constructs that natives sought to revitalize through joint settlement. Once again, such meddling on the part of relatively powerless Spaniards was largely doomed.

Indians who periodically joined mission communities constructed family units in various ways, which did, on the surface, resemble missionary ideals of a nuclear family composed of a husband, wife, and children. Indeed, the nuclear family formed a key social unit for them, but Spanish ideas posited these as patriarchal households, whereas native families were grounded in separate but complementary gender roles in extended kin networks. Most of the bands of southern and coastal Texas lived in consanguineous units constituted as extended family households or family bands within which nuclear families were subsumed. Whole villages or camps might represent one lineage, or when disease took its toll, remnants of families formed new ties and new villages through intermarriage. As fray Vicente Santa María argued of Indian bands in the area that became Nuevo Santander, “that which among themselves and by us are designated nación is nothing other than an aggregate of families.” Levirate and sororal polygyny as well as matrilineal and bilateral kinship and matrilocal and bilocal residence often further differentiated Indian ideas of “family” from those of Spaniards. “Levirate” refers to the marriage of a man to his brother’s widow (in addition to his own wife), and “sororal polygyny” is the marriage of one man to two or more sisters at the same time. “Matrilineality” traces kinship from mother to daughter, and “bilateral kinship” traces family lineages through both parents equally. “Matrilocal residence” means that when a couple is married they live with the woman’s family, while “bilocal” practices give the couple a choice of residence with either the wife’s or the husband’s kin. Extended family settings further diffused the possibility of hierarchies between men and women, with age rather than gender serving as the more important basis of authority. Courtship and marriage practices also lessened potential imbalances in male-female power relations. Early marriage age, scarcity of unattached adults, and high rates of remarriage indicated Indians’ recognition that it was hard to survive with out the contributions of a spouse and that men and women merited equal value in their respective labors. Practices of sororal and levirate polygyny, birth control, and easy divorce limited male authority further by giving women more freedom within family units.51