Chapter Four

Negotiating Fear with Violence: Apaches and Spaniards at Midcentury

In July 1767, as the marqués de Rubí inspected the defensive capabilities of the northern provinces, riding up from Coahuila toward the Presidio San Sabá northwest of San Antonio, he passed through the Nueces River valley, where he found the remains of two missions, San Lorenzo de la Santa Cruz and Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria del Cañón, established for Apaches a mere six years earlier. In the eight days it had taken him to travel from Presidio Santa Rosa (in Coahuila) to the missions, his expedition had passed numerous Apache rancherías, some in which the Indians were farming along the Rio Grande, others in which they were traveling to trade with Coahuila residents and soldiers. The farther north he moved into Texas, though, the fewer he had seen, finding instead abandoned encampments alongside the sad stubble of crops from years past. Upon reaching the river valley known as El Cañón where the missions had stood, he camped at the “unpopulated ruins” of Candelaria—consisting of only a house with a small chapel and a large hut—before proceeding on to inspect the twenty-one soldiers (from Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas far to the north along the San Sabá River) who were garrisoned at Mission San Lorenzo, a place he also found “to be without a single Indian.” He concluded that they could only be called “the imaginary mission[s] of El Cañón,” while the Apaches were a “never-realized congregation.” How had the project come to such an ignominious end in so little time?1

To associate Apaches with Spanish missions might seem rather strange. At midcentury, Spaniards and Apaches had been combatants far longer than allies. By the time Spaniards moved into Texas permanently in the 1710s, long experience in New Mexico had established in Spanish imaginations that Apache men were such fierce warriors that “in the end, they dominate all the other Indians.” Viceregal authorities had initially identified Apaches as such a powerful nation that the Spanish government needed to form with them a “perpetual and firm confederation.” They hoped that such an Apache alliance would serve as the equivalent of a northern cordon of armed garrisons protecting Spanish dominions from French aggressions. Yet, in Texas their attempts to ally with Caddos automatically put Spaniards into a hostile position vis-à-vis Apaches. The Spanish expeditions sent to Caddo lands and the missions and presidios that Spaniards erected there made a Spanish-Caddo alliance clear to Apaches. When native groups pledged alliance with each other, they simultaneously pledged their enmity against one another’s enemies. No possibility of dual allegiance existed. Neither did they draw lines among economic, civil, political, and military relations—an alliance in one area meant alliance in all others. Thus, Spaniards became enemies of Apaches without even meeting them. The Spaniards’ joint settlement in the mission-presidio complex at San Antonio with Indian bands of central Texas such as Payayas and Ervipiames (who also counted Apaches among their foes) only strengthened this enmity further.2

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, moreover, the spread of Spanish horses and French arms was reorienting native power relations across Texas and the Southern Plains, a development that did not bode well for Spaniards in Texas. Though now less well-known than their western relatives, Lipan Apaches represented a widespread and formidable power at this time. Eastern Apaches living in what is now Texas—primarily Lipan Apaches but also some Mescaleros, Natages (a division of Mescaleros), and Faraones (a division of Jicarillas)—had gained an early advantage there when they acquired horses in the seventeenth century through trading and raiding in New Mexico. By the 1740s, “Lipan” had become the designation used by Spaniards to refer to the easternmost Plains Apache groups variously identified as Ypandes, Ysandis, Chentis, and Pelones. Like their multiple Apache relatives to the west (Chiricahuas, Mescaleros, Jicarillas, and Navajos), Lipans spoke dialects of the southern branch of the Athapaskan language group. Their economy centered on hunting and raiding for bison and horses, which did not allow for permanent settlement, although they did practice semicultivation.3

Consisting of matrilocal extended families but often named after strong male leaders, Lipan social units farmed and hunted in individual rancherías that might cluster together for defense and ceremonial ritual. Usually numbering around four hundred people, such units aggregated ten to thirty extended families related by blood or marriage that periodically joined together for horse raids, bison hunts, and coordinated military action. No central leadership existed, and group leaders made decisions in consultation with extended-family headmen, but unity of language, dress, and customs maintained their collective identity and internal peace. An estimated twelve groups of Lipan Apaches, each incorporating several rancherías, lived in central Texas and used horses to expand their control over bison territories and to better secure their individual rancherías from attack during the agricultural cycles that alternated with bison hunting over the year. As horses’ importance rose, so too did the raiding that maintained Lipan herds and sustained their economy.

Yet, the acquisition of horses by the oft-allied Comanches, Wichitas, and Caddos to their north and east soon neutralized the Apaches’ advantage. More important, this triumvirate was the first to gain European arms through French trade to the east, while they simultaneously cut off the Lipans from trading posts in Louisiana that might have provided them with guns. By the 1720s, Apaches in Texas began to experience new pressures, caught as they were between Spanish settlements to their south that allied with their Caddo-, Tonkawa-, and Coahuilteco-speaking enemies and Comanche and Wichita bands to their north who were moving into hunting territories that Apaches claimed as their own. As the security and defense of their families became even more linked to the ability to move quickly, a regular supply of horses became all the more critical to Apaches’ survival. The horse herds of Spanish missions, presidios, and settlements proved irresistible to increasingly vulnerable Apaches.

Apache domestic economies and power relations together became more defined by warfare. Lipan Apaches oriented their subsistence into seasonal patterns that allowed them to plant crops in the early spring and then move their entire bands through bison areas for extended periods of hunting in spring and fall, returning only after the hunting season ended to harvest crops. But farming was on the decline in the eighteenth century as economic activities that were centered on the care of horse herds and the production of saddles, bridles, and leather armor for both horses and warriors expanded along with increased hide processing. Band life thus became even more focused on the acquisition of horses and bison. Increased prestige for the warriors who supplied both followed apace as the reputations won or lost in raids and hunts became more central components to internal social, economic, and political relations and hierarchies. Women who practiced limited horticulture also gathered plant foods and traded with other native groups for agricultural products. At the same time, the larger size of raiding and hunting parties meant that women and children traveled with warriors, assisting men in maintaining camps, processing hides, and even making arrows. As they hunted in family bands, women might even participate directly in hunting deer, antelope, and rabbits.4

Apache adaptations of kin-based gender roles to these historical changes, however, could have unintended and deleterious effects. Women’s presence in raiding and hunting parties put them in the line of hostile fire and capture by Spanish forces seeking retaliation for raids that were gutting their herds. For Spanish observers, Apache socioeconomics seemed to mute or disguise gender divisions of labor, though it was not always clear whether they could not or chose not to recognize them. Either way, Spaniards had little understanding of Apache women as noncombatants and thus made little association of those women with peace. Indeed, at times, Spanish authorities officially categorized Apache women as a “regular reserve corps” of Apache military forces. Attitudes such as these put Apache women squarely in harm’s way when it came to Spanish hostility and battlefield violence.5

Lipan Apaches north of the Rio Grande. The man has a painted buffalo robe draped over his shoulder, and the woman wears a fringed chamois skirt, poncho, leggings, and moccasins. Watercolor by Lino Sánchez y Tapia after the original sketch by José María Sánchez y Tapia, an artist-cartographer who traveled through Texas as a member of a Mexican boundary and scientific expedition in the years 1828–31. Courtesy of the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

But for Lipan Apaches, their mobile lifestyle kept inviolate their kin-based definitions of gender and the accompanying social and political roles for men and women. Though they traced their lineage bilaterally (through both parents), they organized their family bands by matrilocal residence. In a sense, female-defined households balanced male-defined raiding and hunting economies. The origin or emergence myth for Lipan people sanctified this order in the story of a divine heroine, Changing Woman, and her son, culture hero Killer of Enemies, who together created the world. Under his mother’s guidance and direction, Killer of Enemies slew monsters who threatened the people, persuaded horses, antelope, and buffalo to provide for the people, and then taught the people how to raid and war. Once he had established peace and equipped the people for life on their own, Killer of Enemies returned to live in Changing Woman’s home. From there, the two deities offered supernatural aid as well as a continued model of a matrilocal household and male-centered political economy. Thus, Spaniards not only refused to recognize divisions between Apache men and women. When they attacked kin-based rancherías and took women captive, Spaniards also struck at the peaceful order and gender balance within Apache polities.6

Apache raids and Spanish reprisals sparked a cycle of violence that lasted thirty years. If Apaches extended kin classifications to all with whom they interacted, then Spaniards represented the negation of brothers. Strangers were only potentially dangerous; enemies were a proven commodity. And Spaniards were clearly enemies. Raiding did not always signal war; it could be merely an alternative to trade. But in the case of Spaniards in the first half of the century, Apache raiding was an instrument of both economic gain and political competition. Yet, if Spanish-Apache relations were the antithesis of kin, even that relationship came with prescribed ritual and behavior. From the 1720s through 1740s, Spanish violence against Apache women via captivity and enslavement alternated with Apache violence against Spanish men via bloodshed and humiliation, as both groups became increasingly demoralized by the other. Spanish soldiers could not prevent Apache raids or bring about their complete defeat, despite numerous efforts to chase down Apache raiders and challenge them in battle. So, instead, they exploited the only vulnerability they could find in such an invincible foe: women and children. In the wake of daybreak attacks on their villages, Apache men answered the loss of family members at Spanish hands by cutting off those hands, often literally, with rare but potent displays of combat and mutilation on the battlefield.

At midcentury, however, when Spanish and Apache men came to realize that a far greater threat to both their women and families appeared with expanding Comanche and Wichita bands, they saw reason to make amends and then form an alliance for the first time. Past conflict inevitably shaped their first peace accord, nevertheless, and Spaniards and Apaches opened their diplomacy with handicaps when they pursued a relationship through bonds of fictive and real kinship. Mission-presidio complexes again became a focus of such efforts. Taking a more martial tone than that found in the San Antonio region, however, Spanish-Apache negotiations established these sites to ally Apache warriors and Spanish soldiers in defense rather than as an alliance of families joined in settlement. If the diplomatic pendulum had first swung far in the direction of male violence in the first half of the century, its swing in the opposite direction toward female mediation was a slow one. Replacing enmity with peaceful alliance did not prove easy, and Spaniards and Apaches spent the next twenty years (1750s and 1760s) sparring over how they might achieve that goal as Apache women asserted a more pacific role in diplomatic gambits.

Apache men’s need to defend the women of their families and communities, on the one hand, and Spanish men’s coercive use of those same women to manipulate Apache men, on the other, often put women at the center of violence and diplomacy. By a not too circuitous route, Spanish men’s fear first led to Apache women’s captivity. Construction on settlements at San Antonio had barely broken ground when Apaches declared war by planting arrows with red cloth flying from their shafts like small flags near the presidio site. As Apaches mounted raids on the horse herds of San Antonio missions, civilian ranches, and the presidio beginning in the 1720s, frustration escalated into terror among Spanish settlers, soldiers, and officials. The idea of Apaches as inveterate raiders became so fixed in Spanish minds that they attributed any attack by unknown raiders in the San Antonio area to them. Presidial forces’ inability to stop the warriors’ relentless attacks transformed simple horse raids into what Spaniards believed to be signs of a “war of extermination” against them. Thus, the tacticians of raids so profitable they took hundreds of horses became, in the Spanish telling, “enemies of humanity” terrorizing civilian populations of women and children. By such constructions, Spaniards transformed their soldiers and officers into chivalrous defenders of “civilization” while reducing Apache warriors to “unmanly” cowards preying on the “most defenseless of innocents.”7

Death counts to the contrary, military and diplomatic officials labeled Apache warriors barbaric killers of women and thus characterized them as men without honor. Whenever Spanish officers and soldiers found themselves in a weak situation, they cast blame outward by projecting upon Apache men a “savage” nature that could not be answered in kind. It was no coincidence that the Apache bands who posed the greatest challenge to Spanish authority figured prominently in Spanish images of Indian warriors so cruel they “killed regardless of sex and age.” Spanish officials stubbornly turned a blind eye to the economic considerations behind Apache men’s raiding and instead ascribed only motivations of irrational bloodthirstiness to their actions.

Despite Spanish claims, however, horses were the attraction for Apache raids, and generally the only people injured or killed were ranch hands or soldiers trying to prevent the theft of animals. The burial records of Mission Valero, for instance, indicate that out of 1,088 deaths recorded between 1718 and 1782, only 15 people died at the hands of hostile Apache, Comanche, or Coco raiders (1.3 percent)—and Apaches did not even bear sole responsibility for the deaths. Moreover, the danger of injury rested outside the settlements, primarily where horse herds were maintained at nearby ranches or presidio corrals, away from the arenas and activities of women and children. Fray Benito Fernández de Santa Ana noted that although enemy Apaches “can travel through the land as they please,” it was the “shepherd Indians” who were the most endangered. Fray Ignacio Antonio Ciprián similarly pointed out in the 1740s that “although [mission Indians] are in constant danger of attack by the Apaches (a very bold enemy who has dared to enter the presidio even in day time and roam the streets), they have never entered this mission grounds.” Apaches only once approached the San Antonio community itself, and that, as will be discussed later, was an unheralded response to Spanish slave raids on Apache rancherías.8

Indeed, it was actually Apache women who became the primary targets of violence. In a series of retaliatory strikes after horse raids, Spanish forces aimed at the capture of Apache women and children. Echoing policies adopted late in the sixteenth century against Chichimecas who fought to keep Spanish invaders out of their lands in north-central Mexico, officials in Texas sought to use offensive raids on Apache encampments to exterminate or enslave as many as possible in order to “pacify” the regions nearest their settlements. Technically, any Indians captured in a “just war” were to be sentenced as criminals to a finite term of enslavement, but perpetual servitude was touted as the only means of achieving peace. The language used to describe the Apache threat bore a striking resemblance to what had been said over one hundred years earlier of Chichimecas, as Spaniards writing from a siege mentality rhetorically denounced Apaches as “barbarous enemies of human-kind,” while strategizing that the opportunity to gain Indian slaves would be sufficient incentive to motivate soldiers and civilians to take up arms for the state. Their repeated decisions to attack rancherías while the Apache men were gone on bison hunts made it clear that the Spaniards were not in search of peace but of women and children to enslave.9

In turn, Spaniards rationalized their decision to keep these captives in bondage as necessary for defense and, by sleight of interpretation, deemed Apache women and children captured by Spanish forces not cautivos but prisioneros (prisoners of war). By taking Apache women out of the category of noncombatants, Spaniards deprived them of the consideration and protection that Spanish codes of war dictated for women—in effect, a denial of their identity as women eligible for the privileges of respectful Spanish womanhood. They believed that if violence against Apache women helped to protect Spanish women by providing officials with pawns with which to manipulate Apache men, then so be it. In turn, Lipan oral traditions would later declare that raids on Lipan encampments by enemies who attacked women and children as they stood right by their homes were “not the way men fight.”10

Telling incidents reveal the process by which captive Apache women and children became political capital. Spanish captive-taking began within five years of the establishment of the San Antonio de Béxar presidio, when Spanish military officials decided something had to be done about Apache raids. Following a raid by five Apache warriors that netted fifty horses early in 1722, Captain Nicolás Flores took ten men in pursuit of the raiders and retrieved all the horses. The Spaniards also marked the success of their punitive expedition by triumphantly bringing back to San Antonio four of the Apache men’s heads as trophies. Within a month, Flores had received a promotion in his commission at the presidio. But still the raiders came. The next year, when Apaches showed up Spanish forces by carrying off eighty horses from the presidial herds despite the presence of ten soldiers guarding the gates, Flores opted for a more drastic plan to thwart the Apache men. After he and his soldiers had pursued the raiders for twelve hours without catching them, they returned to the presidio for reinforcements so that they could take living trophies—wives and children—from Apache rancherías.11

Following signs that the Apache raiding party had divided into five groups, going off in as many directions (suggesting that warriors from five bands took part in the raid), Flores, thirty soldiers, and thirty-three Indians from mission communities chose to follow only one. For thirty-six days, they tracked what they believed to be the raiders’ path until they reached a ranchería of eight to nine hundred Apaches, more than a hundred leagues away from San Antonio. The combined presidio and mission forces made a surprise attack and fought Apache warriors for six hours before claiming to have killed thirty-four warriors, including one chief. Reports—including the testimony of four soldiers present at the battle—indicated that in fact Flores’s forces had attacked an Apache band innocent of the raids, had shot men in the back as they covered the retreat of their families, and had killed and captured women and children as they tried to escape. From the belongings left at the ranchería by fleeing Apache families, Flores’s men also plundered 120 horses, saddles, bridles, knives, and spears. Yet, their more significant war booty was twenty women and children.12

Upon their return to San Antonio, conflict immediately flared between military and church officials over the fate of the captives. Objecting to the tactics that had won Flores his human prizes, Franciscan fray Joseph González, one of the missionaries at San Antonio de Valero, demanded that, rather than dividing them up among the men along with the rest of the booty as planned, the captives be repatriated in order to reestablish peace. One Apache woman emerged as both pawn and agent in negotiations when fray González determined that if sent back to her village as a diplomatic overture, she “could be the most opportune means of bringing about peace with Apaches and the safety of the presidio.” As a mark of goodwill, and perhaps as advertisement of the benefits of conversion, the missionary dressed her “after the Spanish fashion” as best he could, using a petticoat, blouse, white embroidered hose, ribboned hat, and green skirt borrowed from soldiers’ wives. To mark the peaceful spirit of her mission, he presented her with “an inlaid cross, which was very beautiful and which she should wear on her neck, with an embossed ribbon which Father took with great faith, since it had served as the ribbon to the key of the depository [of the mission’s sacred vessels].” With a flint and a rock for making fires along the way, she left for home with a group of soldiers to escort her out of town.13

Twenty-two days later, the captive woman returned to San Antonio accompanying a principal Apache man with his wife at his side and three warriors at his back. With no translator, communication was reduced to symbolic gestures. When greeted by Spanish officers, the Apache leader presented Flores with both a baton of command (as a sign of his chief’s political authority) and a bison hide painted with the image of the sun (as a sign of Apache deities’ spiritual power). The Spaniards interpreted them simply as “a sign of peace” sent by Apache leadership. Meanwhile, the captive woman greeted fray González with gestures of joy and, when introduced to the missionary, the principal man too placed his hand on his chest to convey his pleasure at meeting the man who had emancipated her. González and other missionaries then conducted the Apache delegation to Valero, where the Franciscans quickly donned formal vestments and had the church bells rung and mass celebrated in thanksgiving for the Apaches’ arrival.14

The delegation tarried for three days, housed variously in Mission Valero and in the homes of soldiers. Nothing, however, could alter the fact that even as the female emissary had traveled home with González’s peace commission, Flores and his soldiers had divided the remaining nineteen women and children among themselves, some of them being taken to the Bahía presidio, while others were deported to lands even more distant. In the end, the delegation departed with only gifts scrounged up by Valero missionaries: five rosaries and five knives for Apache chiefs, two bunches of glass beads, earrings, tobacco, brown sugar candy, and ground corn. Two months later, when thirty Apaches came again for their lost family members, a chief endeavored to end Flores’s stonewalling about the captives’ fate by offering four Apache men as hostages if the Spanish commander would at least free the children. Flores flatly refused. Four soldiers later testified that as Flores spoke heatedly, the Apaches gathered their belongings to depart the meeting room, and one chief took the hand of one of the little girls held captive, turned with her to face Flores, and gestured as if to say, “‘This is what you want, not peace.’”15

The experiences of Cabellos Colorados’s family band a decade later illustrates most poignantly the devastation that could be wrought by Spanish military policy. In December 1737, the chief and his party approached San Antonio seeking trade with Spanish residents, as members of his band had done intermittently in past years. The equal number of men and women in the party suggested their peaceful intent, yet Spanish forces were looking for someone to nab for recent horse raids, and the Apache group’s arrival appeared too providential to pass up. When twenty-eight armed soldiers rode out, Cabellos Colorados and his men clearly did not expect a fight and thereby were quickly surrounded and captured. As an indication that the Spaniards had no evidence that the men in this group were actually raiders, they insisted on hearings in order to gather proof.

In June of 1738, Governor Prudencio de Orobio y Basterra thus proceeded to solicit testimony on the “infidelity of Apaches”—implicitly deeming them all one united group—although Cabellos Colorados and his people were the designated targets on hand. In the end, the “evidence” against them amounted to assertions based on coincidence, rumor, and prejudice. First, Spaniards saw as suspicious that Cabellos Colorados’s ranchería, of all the Apache rancherías known to them, was located closest to San Antonio. Second, various soldiers testified that no “assaults” had taken place since their capture, so the raiders must be the ones in jail. Third, presidio commander José de Urrutia identified Cabellos Colorados as a man of standing and reputation among Apaches—so much so that he claimed to have heard rumors that the leader had bragged to a nonexistent entity, a fictional capitán grande of the Apache nation, that he would raid all the presidial horse herds of San Antonio, Coahuila, San Juan Bautista, and Sacramento and then slaughter all the inhabitants. Such rhetoric implied that Cabellos Colorados was a powerful man whose downfall might strongly enhance the reputation of the Spaniard who brought it about.

Last but not least, the Spaniards recognized Cabellos Colorados’s wife to be one of three women who had earlier come with a man to trade in San Antonio, and by roundabout logic, they argued that her presence among those arrested meant that she had been a part of a surveillance party sent to scout troop movements. In turn, if the four Apaches had been there to scout troop movements, the Spaniards surmised, then the family band must be guilty of the later raids. Since Spanish battlefield tactics omitted Apache women from the category of noncombatants meriting exemption from harm and instead viewed them as targets for enslavement, unsurprisingly, Spanish officials ignored the fact that warriors would not allocate the male-defined task of warfare to women and that a party of three women was most likely simply there to trade. In the end, Cabellos Colorados and the sixteen men and women were held responsible not just for one raid but for all the crimes of the preceding years.16

In the meantime, Cabellos Colorados tried to negotiate with his captors, relying on female hostages as mediators, by requesting that Spaniards allow one of the women to return to his ranchería to get horses with which to buy their freedom. Over several months between the December capture and the June hearings, Apache women traveled back and forth between Apache and Spanish settlements, trying to exchange horses for the captives. A subsequent attack on their ranchería by Hasinai Caddos killed twelve, captured two boys, and stole all their horses, however, severely limiting the Apaches’ ability to produce enough horses to appease Spanish officials. In the meantime, the women brought bison meat for their captive kinsmen and bison hides as gifts of goodwill for Spanish officials. In August, an elderly man accompanied the women and brought news that, although they could not supply any horses, he had visited with all the Apache bands and asked them to stop all raids, and he now offered this peace agreement to the officials in exchange for the captives. Governor Orobio refused him. The elderly man then tried to exchange a horse and a mule in an effort to free his elderly wife who was among the captives. The governor rebuffed him again.

No peace offering could offset Spanish desire to punish someone for the deeds of Apache raiders who had long made a mockery of their presidial forces. Ultimately, Orobio consigned Cabellos Colorados and his entire family to exile and enslavement. In his order of February 16, 1739, he refused to spare the women and even went so far as to specify the inclusion of a baby girl in the punishment, declaring that “the thirteen Indian men and women prisoners in the said presidio, [shall be taken] tied to each other, from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, to the prison of the capital in Mexico City, and that the two-year-old daughter of chief Cabellos Colorados, María Guadalupe, shall be treated in the same manner.” The collera (chain gang; literally, “horse collar”) of Apache prisoners—seven men, six women, and one infant—left on February 18, escorted by a mixed guard of soldiers and civilians.17

They traveled for 102 days on foot—the men shackled each night in leg irons, stocks, manacles, or ropes—before reaching Mexico City in late May, where they were incarcerated in the viceregal prison, the Real Carcel de la Corte (the “Acordada”). Two of the fourteen died en route to Mexico City, and fewer than six months later, seven more had succumbed in the disease-ridden prison or work-houses. Whether any of the other five survived is unknown; the last records say only that prison officials sent two men to a hospital, while two women, although very ill, went into servitude in prominent Spaniards’ private homes. Little María Guadalupe was left without her mother, and later efforts to reunite them failed when the appointed “guardian” absconded with Cabellos Colorados’s wife. This family would not be the last to suffer such a fate.18

Taking the legal distinction between cautivos and prisioneros as a free pass for wartime enslavements, soldiers and civilians gradually but inexorably ravaged Apache family bands for their kinswomen and children in the 1730s and 1740s. The Apache women and children who served as human trophies of war were parceled out among soldiers and citizens to be used in their homes as slaves or sold for profit to Mexican mining districts or West Indian labor camps. Spanish military men might proclaim their capture as proof of the reassertion of Spanish honor, but in practice, expeditions reputedly sent to “punish” Apaches amounted to little more than slave-raiding parties. A 1787 memorial from the San Antonio cabildo, or city council, proudly promoted the deeds of the “flower of our ancestry” who had fought a “glorious war” in the 1730s and 1740s by seeking out Apaches in their own lands, where they “killed them, destroyed them, routed them, and drove them off.” “They conquered them and formed chains of prisoners,” it continued, “and spared the lives only of those captives who were likely to be converted to the faith, and the children, whom they brought back to increase the missions and the villa.”19

The immediate baptism of captured Apache children further indicates that their Spanish captors had no intention of using the children to barter for peace. Rather, it signaled their new status as slaves of Spanish owners. Texas colonists, like their New Mexico neighbors, called enslaved children “criados” (literally, “those raised up”) to signify that, in return for their rearing, these children owed a labor debt to their saviors. In this way, the trade in Apache children also circumvented legal prohibitions against Indian slavery. Franciscan missionaries did not accept this subterfuge and offered harsh criticism of the military’s tactics. Fray Benito Fernández de Santa Ana argued that nothing was gained by the raids except increasing the Apaches’ hatred, and that it was “ridiculous” that soldiers and citizens who pledged their service to the king in fact sought only their own gain through the “capture of horses, hides, and Indian men and women to serve them.” With such vile intentions, their actions would result in an equally vile outcome, he concluded.20

Vile outcomes did indeed follow. Apache warriors responded to Spanish slave raids with their own carefully chosen violent expressions. Evolving European and Indian practices of mutilation and trophy taking held a crucial place in Spanish-Apache warfare. Spaniards severed the heads of Apache men before taking their wives. Similarly, Apaches took scalps from the heads of fallen foes as well as the military dress and decoration that marked them as warriors. Native fighting men in Texas displayed their war records in body painting, headdresses, and specially decorated spears or lances, and they recognized that Spanish uniforms and devices served the same purpose. Stripping a dead foe of the dress and markers of valor he had earned as a warrior or soldier stripped him of that identity.21

With such deeds, Spanish soldiers and Apache warriors inscribed expressions of valor and emasculation onto their warfare. Lipan Apache oral traditions directed that warriors in battle were to “keep it up till they find out who are the best fighters.” Pointedly, a 1719 expedition diary recounted some soldiers’ encounter with Apache men along the Arkansas River who fired insults at the Spaniards, calling them “mujeres criconas” (female genitalia). By extension, Spanish officials interpreted Apache raids as “insults” indicative of the Indian men’s “insolence” and “haughtiness.” Any chance to defeat them was the chance to “beat down their pride.” Espousing such sentiment, Commandant Inspector Hugo O’Conor declared that, after various expeditions against Apaches, he and his men had “made evident to the barbarians what the arms of the King were like when there were serious attempts to make them glorious,” thereby “reestablishing the honor of the King’s arms.”22

Spanish-Apache exchanges of vicious retaliations began in March 1724, less than three months after failed negotiations with Flores over the return of the first group of Apache captives held in San Antonio. Apache men attacked two Spanish military couriers fifteen leagues outside of the town who were bringing dispatches from the San Juan Bautista presidio on the Rio Grande. One man escaped and brought soldiers from the Béxar presidio back to the site of the attack, where they discovered soldier Antonio González’s nude body mutilated with arrows in the stomach and back, a spear wound, flesh torn from one calf, and scalp taken. The discovery of his hat and shield a short distance away, in addition to the removal of his uniform, attested to his attackers’ intent to strip him of warrior trappings. But then they found all of it—González’s scalp, clothes, hat, and shield—abandoned a short distance away, perhaps left behind as a sign that Apaches did not even deem them worth taking as trophies.23

Warriors extended their scorn to an entire unit of Spanish soldiers in 1731. That year, an Apache raid that took sixty horses from the San Antonio presidio in broad daylight came to a crushing end for the Spanish military when the six soldiers who had been guarding the corrals decided to pursue the raiders, followed close behind by nineteen more men. When the reinforcements caught up with the six soldiers, they found them losing a fight with forty Apache warriors, and—to make matters worse—a reputed five hundred Apache warriors riding up (the number likely an exaggeration meant to excuse the Spaniards’ defeat). “They attacked us with the greatest audacity,” Captain Juan Antonio Pérez de Almazán reported of the ensuing two-hour battle, explaining, “They advanced in a crescent, pressing our center as vigorously as they did both wings, but because my men were so few we could not defend all sides at once.” The Lipans accomplished all this armed with bows and arrows, while Spanish guns proved ineffective against mounted warriors who protected themselves and their horses with what the Spaniards could only describe as “armor” made of bison hides. The Apaches used the crescent-shaped line to surround the twenty-five overmatched Spaniards at the foot of a tree, whereupon “the enemy, for no apparent reason, took off at top speed and disappeared.” A Spanish officer who judged victory in the number of dead left on a battlefield could not see the reasoning behind the Apache warriors’ actions: for warriors who did not count victory in the number of enemy dead, two soldiers killed, seventeen more wounded, including the commander, and the complete dominance over them all established quite clearly the Apaches’ superiority.24

Other Spaniards seemed to have reached the same conclusion about the Apaches’ successful assertion of superiority, as Governor Juan Antonio de Bustillo y Ceballos soon set out to respond in kind with an expeditionary force made up of 175 Spaniards, 60 mission Indian warriors, 140 pack loads of supplies, and 900 horses and mules—an expeditionary force large enough to ensure the reestablishment of the “honor of the king’s arms.” They marched for six weeks, winding their way, and perhaps periodically losing their way, over two hundred leagues through Apachería before locating four separate Lipan and Mescalero Apache rancherías, with an estimated population of 2,000 men, women, and children spread out for a league along the San Sabá River. A majority of the men, some 500 warriors, were away hunting bison, so prospects for an easy victory appeared within the Spaniards’ grasp.25

Spanish forces launched a daybreak attack, which the reduced number of warriors held off for five hours. Then, Apache men covered the retreat of their families as Spaniards captured 700 horses, 100 mule loads of peltry, and 30 women and children. The next morning, Spanish forces awoke in camp to see armed Apache warriors watching them from vantage points all over the surrounding hills. The surveillance continued as they made their slow way home over the course of fifteen days, with warriors tracking them the entire way to San Antonio and ensuring their departure from Apache lands with the loss of as many horses as could be taken each day in payment for the abuses they had suffered. The captured women and children remained under guard and beyond retrieval.26

Upon their return, Governor Bustillo and many others seemed more cowed than bolstered by their deeds on the San Sabá River. A petition of the cabildo stressed the need to strengthen defenses in anticipation of an invasion by Apache warriors aimed at liberating their kinswomen. Soldiers, perhaps in mute recognition of the Apache men’s grief, wished to move their own families out of harm’s way—beyond the Rio Grande. The threat of Apache attack overshadowed even everyday labors in the town. Spanish and Indian vaqueros refused to go to outlying mission ranches to guard cattle. Soldiers charged with defending the San Antonio community became increasingly desperate, judging from an escalating rate of desertion and their own raids on mission livestock and cattle to fulfill subsistence needs.27

After seeing firsthand the extent of Apache bands living northwest of San Antonio, military veterans did not doubt the Apaches’ capability for revenge and within two days of their return petitioned the governor to negotiate with them, arguing that “Otherwise, this Presidio, with its town and Missions, will be exposed to total destruction by this host of enemies.” Citizen settlers who had previously clamored for Apache slaves now pleaded with Bustillo to prohibit distributing the most recent captives and instead hold them as hostages to negotiate a truce—a failed plan. When one Mescalero and one Lipan woman were freed with letters of truce from the governor, Apache warriors sent a clear message in response by ambushing Spanish soldiers. Accounts of the event variously attested to the bodies of dead soldiers “marked with fury and impiety,” “flayed” with pikes and arrows, and “in-humanly cut to pieces.” And so the bloody exchange of manly retribution continued, back and forth through the 1740s.28

Then, Spanish slaving campaigns in 1745 finally ignited concerted violence by Apache men. In an unprecedented move, Apache leaders sent four women to San Antonio first to warn the missionaries at Concepción (notably, fray Fernández de Santa Ana, who had been one of the few in the San Antonio community to work with them for their wives’ and children’s emancipation). Next, the women notified presidial officials that only Mission Concepción would be spared their vengeance. Over the following three weeks, Apache raiders killed nine people and subjected presidial, mission, and civilian herds—all except those at Concepción—to relentless raids. Fernández de Santa Ana claimed later that Apache warriors “made war more cruelly than I have ever experienced in the province.” San Antonio paid in lost lives and horses for the Apache women and children they had killed and enslaved over twenty-five years.29

Yet, the real measure of Apache fury came in a direct attack upon the presidio itself that same year—another unprecedented act in Apache warfare. Three hundred and fifty Lipan and Natage Apaches entered San Antonio at night and began their attack. As fighting broke out, an Apache captive held at one of the missions escaped to join the other Apache warriors. Once he was among them, a Natage chief immediately asked after the fate of his seven-year-old daughter taken captive two months before. The Spaniards in fact held not only the chief’s daughter but also her cousin and a woman in her twenties with two children—all from the chief’s family. Upon hearing that the captives were all well and in the missions, the Natage leader consulted with other band chiefs, and they called off their warriors. The attack’s impetus must have been the men’s belief that, like most of the captives before, their wives and children had already been sold away or deported, which required bloody revenge. The news that they were not lost to them was sufficient to stop the attack.30

Although Apache warriors took more Spanish horses and Spanish forces took more Apache captives before a truce was finally achieved, the fate of that Natage chief’s seven-year-old daughter ultimately helped to bring about the first peace accord between Spaniards and Apaches. From 1745 through 1749, a stream of women, both captive and free, moved between San Antonio and Apache rancherías as a human line of communication. The process began in August 1745, when the Natage father sent a woman bearing a cross to San Antonio, accompanied only by a small boy, to offer gifts to presidial commander Toribio de Urrutia as a pledge of Apache goodwill. Other Apache rancherías sent women along the same path. The Spaniards responded with freed Apache women who left San Antonio carrying Spanish pledges to release hostages from previous campaigns in return for peace. All the while, presidial commander Urrutia fought long battles to force San Antonio residents to relinquish Apache women and children held as slaves in their homes—reputedly risking death threats from some enraged citizens. Under orders from the viceroy, even Governor Pedro del Barrio y Espriella released two Apache girls and one boy whom he had spirited off to the capital at Los Adaes, sending them home with promises of freedom for all captives.31

Diplomatic overtures begun by Apache women ended with the meeting of Spanish and Apache headmen to hammer out a truce. Militarized pomp and protocols ratified the peace that finally came in the summer of 1749. In San Antonio, presidial, state, and church officials greeted delegations led by four Apache chiefs while Spanish troops lined up in formation. At a meeting hall built especially for the occasion, feasts were prepared, and Apache chiefs and leading warriors were lodged in the presidio and missions in deference to their rank. Spaniards freed the 137 women and children taken captive that spring (the fate of those captured in past years remained to be decided). Ceremonies celebrating the treaty culminated in the burial of items chosen especially to signify a mutual pledge to end the war between Spanish soldiers and Apache warriors. With Spanish soldiers, missionaries, and civilians lining one side of a plaza and Apache chiefs, warriors, and newly freed captives the other, male representatives of both groups worked together to bury a live horse, a hatchet, a lance, and six arrows in a large hole dug for the occasion. At the end, Spanish officers joined hands with the four visiting chiefs, and each promised to regard the other as “brothers” from then onward.32

It was not pure chance that led Apache and Spanish men to look more favorably upon one another’s peace overtures at the very time that Wichitas and Comanches were for the first time uniting in an alliance against which both Apaches and Spaniards would need all the help they could muster to defend their respective territories. By midcentury, Apaches were suffering high attrition rates due to years of hostility with Spaniards as well as intensifying conflicts with allied bands of Comanches, Wichitas, Caddos, and Tonkawas, a group that Spaniards began to identify collectively as “Norteños” (Nations of the North; literally, “notherners”). Spaniards meanwhile quailed at the notion that foes even more intimidating than Apaches were headed their way.

As Lipan-Spanish negotiations shifted toward institutionalizing the new alliance, Apache women continued to command center stage. The Spaniards’ refusal or inability to return captives who had been enslaved, deported, or sold long distances away remained a sticking point in Spanish-Apache relations, and Apache efforts may very well have reflected their belief that since the women would never return, family reunions had to be secured by other means. When women were not liberated, at least one Apache family simply chose to move to San Antonio to be near their lost relatives in lieu of an interminable and perhaps hopeless wait for Spanish policy to change. Chief Boca Comida went to San Antonio “without other escort than his relatives and household” in November 1749 and, after a formal meeting with the presidial commander, requested that housing near Mission Valero be established for his family band. He and his family thereby remained at Valero rather than return to Apachería, putting him on the spot for continued negotiations with Spanish officials. Baptism records ten years later list a twenty-year-old Lipan Apache named Pedro as son of “‘old captain Boca Comida,’” indicating that at age ten he had come to Valero with his father and mother (both of whom were identified as still unconverted to Christianity in 1759). The choices made by Boca Comida and his wife seem to reflect a strategy in the face of unyielding Spanish captive diplomacy. The couple might have joined the Spanish community and offered their son for baptism (perhaps as a political gesture), but they nevertheless remained true to their own belief systems. Boca Comida then sought to establish kinship ties for generations when he suggested that “the maidens of their nation should marry the Indians from the missions, and the young men should marry their daughters, for with these ties peace would be assured.”33

If the two sides were to build a relationship of peace, then Spaniards had to be made kin, and women of the Apache family bands stepped forward in a multitude of ways to pledge that alliance. As part of the 1749 peace treaty, Lipan leaders like Boca Comida proposed marrying some of their single women to mission Indian men at Valero. They did not seek unions with Spaniards, although whether they chose not to or the Spaniards rejected such proposals is unknown. The Apache headmen proposed the marriages as a means of creating kinship ties that would both solidify the alliance and perhaps win a measure of security and standing for Apache women within Spanish settlements. Pointedly, the young women involved in these political marriages were the very ones who had been held in the San Antonio missions for years as hostages. One of the girls was Chief Boca Comida’s niece, which surely added even greater weight to the suggested unions.34

The marriage proposals served as political investments in Spanish-Apache alliance. Records confirm twenty-three baptisms and at least ten marriages of Apache women at Mission Valero between 1749 and 1753. Several of the women married men of status within the mission communities; for instance, Clemencia, a Lipan woman, married Roque de los Santos, a Xarame man who was the Valero governor for nine years. Lipan children, too, often quickly rose to prominence, such as Benito and Anselmo Cuevas, who were captured as small boys in 1745, grew up at Valero, and became a fiscal (official in charge of maintaining mission lands) and an alcalde (magistrate) as adults. In letters to both provincial authorities as well as the viceroy, fray Mariano de los Dolores y Viana stressed the political importance of these unions and baptisms. He reported that he had baptized and married several Apache women to native men of the Valero pueblo, while other mission residents apparently were courting women in Apache encampments outside of town. He concluded that Apache headmen “demonstrated their stability and firmness, significant of the union they desire in having agreed that some Indian women marry those of Mission San Antonio [de Valero].”35

In response to the Apache marriage policy, Spanish captive policies shifted to using the ransom and redemption of female Apache hostages to communicate their own commitment to peace. Perhaps to make amends for the captives they themselves were unwilling or unable to regain from fellow Spaniards, officials focused on preventing other Indian bands from attacking Apaches and, when they could not stop them, “redeeming” captives for return to their families. In 1750, for example, when Caddo bands and their allies appeared at the San Gabriel mission-presidio complex seeking to recruit Bidai, Coco, Mayeye, and Akokisa warriors to accompany them in a massive campaign against Apaches, missionaries tried to persuade Caddo leaders to call off their plans. When that tactic did not succeed, presidial captain Felipe de Rábago y Terán ransomed two Apache women whom the Caddos had captured during a raid in the hope that restoring the women to their families would reinforce the Spanish-Apache accord. Governor Jacinto de Barrios y Jáuregui later commended Rábago y Terán’s efforts for bringing about “a better union.”36

Bolstering the ties created by exchanges of women, the 1749 treaty also declared Spanish and Apache men “brothers.” Thus, with treaty in hand, the next step for each was to make the other act upon the military alliance represented by the fictive kinship term. To do so, both Apaches and Spaniards saw a mission-presidio complex as a means of institutionalizing that alliance. Apache leaders hoped to gain European arms and a military supplement of presidial soldiers for their warriors and required that the complex be built in their own lands to the northwest of San Antonio. Provincial and viceregal officials rightly doubted that Apache interest in a mission complex would offer Franciscan missionaries much chance to convert them but instead recognized the opportunity to cement an alliance and what they hoped would be the “pacification” of the Apaches. The potential payoff lay not only in neutralizing the Apache threat. Admittance to Apachería also tempted them with the opportunity to explore for mineral wealth and to establish a trade route to Santa Fe—neither of which Spaniards had yet been able to pursue because of Apache animosity.37

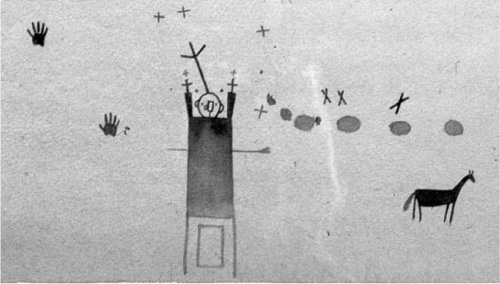

For Apache men, it may have seemed eminently logical to appeal to a religious institution for political and military purposes. Their years of combat against Spaniards provided the primary context within which to interpret Christian symbols and institutions. They knew that missions often had more soldiers than priests and served as fortresses of defense. Spanish military men carried rosaries and medallions into battle that became amulets of personal male power, or “medicine” in Apache understanding. In turn, by midcentury, Apache leaders had already put crosses to diplomatic use, as evidenced by the number of Apache women traversing the countryside with only handmade crosses to identify them as emissaries of peace. Indeed, throughout negotiations for a mission in Apachería, fray Benito Fernández de Santa Ana preserved two very well made crosses brought to him by such women.38

In the late 1750s, a mission-presidio complex in Apachería gave literal form to Spanish-Apache efforts at allied brotherhood, and it did so on Apache terms. Missionaries seemed to realize that they would play second fiddle to military men in interactions with Apache leaders, repeatedly admitting that an “authority of arms” would be essential to maintaining the respect of Apache warriors. Fray Fernández de Santa Ana argued that Apaches would never be pacified or converted if the mission “lacks the respect commanded by a presidio”; only military men—fellow warriors—garnered the esteem of Apache men. The defensive capabilities of Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá seemingly provided a welcome sight to Apache observers. A log stockade surrounded the mission, with only one gate as entry, secured with iron bars, and buildings that cut into the outer wall with loopholes through which defenders could shoot guns or arrows. Across the river and three miles away, Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas had room enough for three to four hundred soldiers and their families—seemingly a permanent commitment to joining Apache warriors in confrontations with Comanche and Wichita foes.39

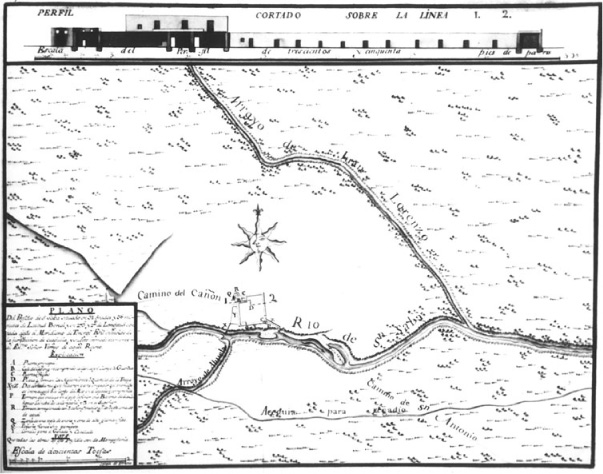

Plan of the Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas at San Sabá, drawn by José de Urrutia, 1767. The Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá, built for Lipan Apaches in 1757, the same year as the presidio, was located roughly four miles to the east on the opposite (south) side of the San Sabá River before it was destroyed by allied Norteños in 1758. Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors (mnm/dca), Santa Fe, New Mexico, neg. no. 15049.

Yet, as the complex went up during the spring, “no Apaches had been seen.” Mission superiors chose fray Benito Varela, because of the “special zeal he had displayed for their pacification,” to go in search of the wayward Apaches, and soon he had an explanation for their absence. After traveling for days without a sign of Apaches, he arrived at a small encampment along the San Marcos River, where he encountered an Apache woman who told him of her capture and escape from a raiding party made up of Hasinais and four apostate warriors from the San Antonio missions. The party had attacked the family band of Apache chief Casa Blanca’s brother, killing him, his wife, and their two children, before taking her, another woman, and two children captive. She later had escaped, bringing with her one of the little girls, who had been wounded by a bullet. Soon after, several Lipan bands, altogether numbering around three thousand, did appear at San Sabá and set up encampments, but in meetings that followed with Spanish military and religious officials, Apache leaders explained why this would be only a temporary visit.40

Avenging the loss or death of women and securing the safety of others determined the Apaches’ decision making, allowing little role for their as-yet-unproven Spanish brothers—especially when it was other native Spanish allies who had attacked them. Two chiefs, Chico and Casa Blanca, alternately pledged their continued friendship but hedged on the arrival date of all their peoples. In meetings with the commander of the new presidio, Colonel Diego Ortiz Parrilla, the headmen found it hard to settle on an explanation that would satisfy, without alienating, the Spanish missionaries and officers. Angered by the death of Casa Blanca’s brother and his family and the capture of his female relatives on the Colorado River, they demanded that the Spaniards bring the guilty mission Indians to San Sabá to be punished before Apache eyes. After Parrilla seemed to respond positively to their requests, they left and in three days returned with their families. Tellingly, however, they chose to pitch their tents not at the mission, but at the presidio where the colonel and his men were encamped.41

Despite Spanish gifts of tobacco and three head of cattle to “soothe his wrath” and “comfort” his grief, Casa Blanca brusquely concluded that “neither he nor his people would settle in a mission because that was not their choice.” More immediately, they had to leave to join other Apaches in a war against their Norteño enemies. Vengeance and the recovery of lost family members were required. Though Casa Blanca was firm in his rejection of settlement at the complex, Chico tried to be more conciliatory, resting his inability to settle with the Spaniards upon his responsibilities as male head of his family and his band. He and his men “need to go and lay in a supply of buffalo meat,” he explained, “and, not being able to deny his people what they asked of him on account of the love he felt for them, he had to accompany them.” Chico went on to say that as long as those hunts remained necessary, they had to keep their families together for fear of a Norteño attack.42

Meanwhile, the deaths of Chico’s brother and sister, who suddenly had fallen ill, cemented the Apache leaders’ determination to depart. Apache beliefs regarding death and the proper rituals of mourning required that family members and their community leave the site of death immediately. The Spanish missionaries noted how the deaths “terrified and stunned the mind and spirit of Chief Chico.” In speaking to fray Diego Jiménez after he and his people had concluded mourning ceremonies, Chico said simply that obligations of honor demanded that he aid the other Apache leaders who “had asked him with tears in their eyes not to abandon them at a time when they had decided on a campaign against the Comanches.” The Apache men further rejected fray Jiménez’s suggestion that they leave their women and children behind at the mission during the campaign. The tracks of Norteño foes could be seen everywhere, and the Apache leaders struggled to make clear to the Spaniards the danger of remaining in the area—implicitly indicating their lack of faith in the promise of safety heralded by the complex.43

Spanish officers and missionaries failed to register the meaning behind the actions of the Apaches who would be their allies, even as they recorded them in careful detail. Several small groups of Lipan warriors passed through in the fall of 1757, stopping only overnight at the mission, their fears manifest in their hurry to move onward in a southerly direction. Apache warriors proceeded to safer ground, distant from their Spanish allies and Norteño enemies, and sequestered their women and families far away from San Sabá. Meanwhile, rumors over the winter filtered into San Sabá that Norteños were massing to destroy Apaches, but well knowing that no Apaches could be found at the mission or the presidio, Spaniards dismissed the idea that the complex might be a target of attack. Rumor became reality when at midnight on February 25, 1758, warriors later identified as Comanches and Wichitas announced their presence by stampeding the presidio horse herd and driving off sixty animals. Although commanding officers sent fourteen soldiers in pursuit, twelve days of tracking garnered the patrol the recovery of only one animal and a disturbing new awareness that the countryside was full of unidentified warriors. Several days later, another squad sent to escort a supply train as it approached the complex fell under the attack of twenty-six Tonkawa, Bidai, and Yojuane warriors. And still the Spaniards failed to anticipate what was coming.44

At dawn on March 16, a united band of an estimated two thousand Comanches, Wichitas, Caddos, Bidais, Tonkawas, Yojuanes, and others (twelve different Indian nations in all) surrounded the mission. As soldiers reported it, the echoes of shouts, the nearby firing of guns, the puffs of powder smoke, and the pounding of horse hooves broadcast the sheer number of approaching Indians “until the country was covered with them as far as the eye could reach.” In the subsequent attack on the Spanish complex, the Norteños pillaged mission stores and herds, burned mission buildings to the ground, and killed Spaniards, including two missionaries who would go down in Catholic record books as martyrs in the cause of saving Apache souls. Spaniards took pointed note of the fact that the attacking Indians rode Spanish horses and carried European arms and ammunition, which they could only assume were the profits of raids on Spanish settlements and of trade in the French markets of Louisiana.45

The Norteños’ political economies in fact did guide their actions that day. With the bounty of raids against Lipans—Spanish horses and Apache captives—Comanches, Wichitas, Caddos, and Tonkawas maintained lucrative trade alliances with Frenchmen in Louisiana, gaining guns and ammunition in exchange. Comanches and Wichitas had not given Spaniards in Texas much attention (though Spaniards and Comanches had come into regular and unfriendly contact in New Mexico), but by midcentury, hostilities with Lipans had eventually brought them south to the fringes of Spanish settlement. As early as 1743, Comanches had pursued Apache raiders to the San Antonio area, and the Apaches’ destination alerted Comanche warriors to a possible association between them. The solid form of the San Sabá mission-presidio complex now confirmed that possibility. Signs of economic, military, and civil alliance were there for any to see. To Norteños’ eyes, the presidio conveyed the joining of Spanish soldiers with Apache warriors, while the mission represented material succor with its domesticated animals, agricultural fields, and regular supply of goods. Adding to Norteño suspicions of Spanish collusion in attacks on Comanche and Wichita rancherías, they had found Spanish goods carried by Apache raiders at the sites of raids. The complex, then, was a supply depot not merely for Apache settlers but also for Apache raiders. Thus, the same presidio-mission complex that Spaniards and Apaches, for different reasons, hoped would spell brotherly alliance transformed Spaniards from strangers to enemies in the eyes of Norteños who had watched its construction from a distance. With one turn of the political wheel, an alliance with one group again had begotten the enmity of another for the hapless Spaniards. The destruction of the San Sabá mission was the concerted Norteño response.46

So, what should be made of the Norteño attack at San Sabá? The first thing to note was that, despite clear numerical advantage, the Norteño allies never sought to engage the presidial forces in battle. The reputed 2,000 warriors did not once approach the presidio, located only three miles away and manned by only 59 soldiers. As a result, despite Spanish rhetoric that the attackers intended to “murder us all, including our wives and children,” all 237 of those women and children remained unthreatened and unharmed within the presidio walls—they were not the Indians’ target. During the three days it took to destroy the mission, Norteño warriors “were seen in the tree tops and on hillsides” around the presidio and clearly wanted their presence known since they “let themselves be seen.” Such a watch would have alerted them to the fact that 41 of the 100 soldiers assigned to the presidio were absent. Rather than attack, however, the warriors instead allowed the presidial forces to bring their herds into the presidio stockade, to send a squad of 14 soldiers and 3 Indians to spy out the “state of affairs” at the mission, and then, after reporting back to Colonel Parrilla, to continue along the road toward San Antonio to meet a supply train headed for San Sabá and even escort it safely into the presidio walls. Telling as well, the majority of the mission’s inhabitants—seven soldiers, one missionary, two soldiers’ wives, eight soldiers’ sons, three mission Indians, one Indian interpreter and his wife, one unnamed youth, and even two Apaches—safely traversed the ground between mission and presidio under the watchful gaze of Norteño lookouts, gaining the sanctuary of the presidio unchallenged. For three days, ultimately, Norteños kept the presidio waiting for an attack that never came.47

Meanwhile at the mission, the Norteños explained to the Franciscans who greeted them that they intended no harm to the Spaniards and sought only Apaches guilty of recent raids on their rancherías. The Spanish missionaries allowed the Norteños entry to the mission after interpreting their signs and gestures as ones of peaceful intent, although they actually indicated hostility with their war dress and decoration and their rejection of customary gifts of tobacco offered by the missionaries. Survivor fray Miguel de Molina described how he was “filled with amazement and fear when I saw nothing but Indians on every hand, armed with guns and arrayed in the most horrible attire. Besides the paint on their faces, red and black, they were adorned with the pelts and tails of wild beasts, wrapped around them or hanging down from their heads, as well as deer horns. Some were disguised as various kinds of animals, and some wore feather headdresses.” Soldiers, in contrast, recognized native battle dress and knew they were looking at a group bent on a fight. Juan Leal observed that “most of the enemy carried firearms, ammunition in large powder horns and pouches, swords, lances, and cutlasses, while some of the youths had bows and arrows.” “All wore battle dress and had their faces painted,” he continued, while “many had helmets, and many had leather jerkins, or breastplates like those of the French.”48

The missionaries’ statements and the evidence of their eyes told Norteño warriors that Apaches were not present (the few still there were hidden). Yet, they must have found plenty to enrage them even without Apaches. The mission and the nearby presidio were proof positive of the Spanish alliance with Apaches. Adding insult to injury, the Franciscans endeavored to mollify the visitors with gifts—gifts that surely advertised better still the goods that provisioned Apache raiding parties against Comanche and Wichita villages. In the absence of Apaches, then, the Norteño warriors instead set about to destroy all objects and structures signaling Spanish-Apache alliance.

Although often referred to as a “massacre” by Spanish contemporaries and historians alike, only 8 people died during the three days of ransacking and demolition that followed at San Sabá mission—6 out of the 31 people at the mission, and 8 out of the 368 at both the mission and the presidio. The fact that so few died offers insight into Norteño perspectives and intentions. As mentioned, the majority of the mission’s inhabitants—women, children, youths, several soldiers stationed to protect it, and two Apaches who were nominally the aim of the warrior party—were all allowed to escape. Half of the victims (4), including one of the missionaries, fray Alonso Giraldo de Terreros, fell in an initial rifle volley that cleared the mission grounds and allowed the attackers access to mission stores and supplies. Norteño warriors then set about destroying the mission itself, a systematic destruction that took many hours. Strikingly, they took very little for themselves, leaving smoldering remains to be found by the Spaniards, including “bales of tobacco, boxes of chocolate, barrels of flour, and boxes of soap, broken apart and burning.” Razing, not raiding, was their aim. In all that time, the Norteños made no effort to locate, much less kill, the hiding Spaniards and Apaches who had taken refuge in one of the buildings. Too, that building was the only one they did not set afire.49

Notable as well, the eight people killed at San Sabá were all men. Although Sergeant Joseph Antonio Flores attested that “our forces had endured much suffering and many deaths at the hands of the savage barbarians, who did not spare the lives of the religious, or those of women and children,” all the women and children at both the mission and the presidio escaped unharmed. One woman, the wife of mission servant Juan Antonio Gutiérrez, did momentarily fall prey to the attackers when they stripped her of her clothes (perhaps an act of plunder as much as humiliation—remember the different Indian and European understandings of nudity), but though surely terrorized, she was not injured bodily. The raiders saw no value in physically hurting Gutiérrez’s wife or any of the other women in the mission.50

The only individuals violently attacked after the first shooting were ones who interfered with the raiders. More interesting still, despite the arsenal of French guns that so exercised Spanish imaginations, Norteño warriors primarily chose beating as their means of attack. One missionary, fray José Santiesteban, upon fleeing the mission yard, unfortunately chose a storage room in which to hide. When the attackers entered in search of plunder and found him there, they “killed him with blows,” stripped him of his clothes, and beheaded him. Santiesteban’s decapitation was long remembered by Spaniards as a particular moment of infamy, especially when his head was found casually tossed aside outside the mission walls. Spaniards found a statue of St. Francis similarly beheaded, its head also left discarded on the ground. Outside the mission grounds, two warriors gave one of the mission guards, Juan Leal, a “sound beating with the handles of their lances,” stripped him of his clothes, but then stopped short of killing him at the urging of one of their Caddo allies. After the Caddo warrior had “protected him from the blows of the others” and patiently “took him by the hand and led him toward the Mission,” Leal later was among those who escaped to the presidio. Finally, when nine soldiers rode over from the nearby presidio, Norteños met them outside the mission, shot two, and sent six fleeing back to the fort unharmed. The last of the nine, Joseph Vasquez, received the only individual attention of the group, being “badly battered” with pikes or lances, stripped of his clothes, and left for dead. After regaining consciousness, Vasquez dragged himself into the mission grounds where, being discovered a second time by those busy with their demolition, again did not merit death but was casually picked up and tossed aside by the raiders. He too later escaped to the presidio.51

Violence is rarely arbitrary but, indeed, a means of communication, so what do these beatings say about the Norteños’ intent regarding their newly classified Spanish enemies? On the battlefield, Comanches, Wichitas, Caddos, and their allies recognized certain protocols of warfare based in concepts of male rank and honor. For a contest to be meaningful, opponents had to be equally matched, and fighting represented a duel. Victories were not measured by the number of dead but rather by “grades” of martial deeds demonstrative of a warrior’s prowess. Comanche men, for instance, defined a “coup” as an exploit in battle that involved direct contact with the enemy and that public opinion recognized as worthy of distinction. According to Comanche belief, “it required more bravery to hit an adversary with a spear or a war club than to pierce him at a distance with an arrow or a bullet.” The inherent risk involved in putting oneself in the proximity of an enemy was key to this code of coup honors, not the violence inflicted on the opponent. Moreover, the honor of coup did not require the death of an enemy.52

Thus, a warrior’s mode of combat communicated his estimation of the enemy he struck down. Spaniards, in fact, shared a similar honor-bound ideology. One Spanish official called upon a Latin saying, “Dolus, an virtus, quis in hoste requirat” (Whether it be craft or valor, who would ask in dealing with a foe?), as precedent for his argument that Spanish soldiers did not have to demonstrate or maintain valor against “inhuman” foes like Indians. For both Europeans and Indians, ritualized acts of coup or demeaning modes of attack could assert the honor of the aggressor, while at the same time impugning that of the victim. Actions that fell outside customary fighting tactics thus took on a significance of their own. In this case, Norteños appear to have deemed beating appropriate treatment for an ignoble enemy—a punishment befitting criminals, not battlefield opponents, in their societies. Tellingly, at San Sabá (and later at El Cañón, as will be seen), Norteño allies rejected all possible battle trophies of Spaniards. They scalped no one except for the mission steward Juan Antonio Gutiérrez, who did not escape with the others, and left the heads of fray Santiesteban (and St. Francis’s statue) where they fell, unscalped.53

As already mentioned, complicated systems of belief subtly linked together Spanish soldiers and Indian warriors across the region’s battlefields and found expression in trophy taking. Both took goods from fallen enemies, though they often chose only men who had distinguished themselves in battle, the choice denoting their belief that trophies served to transfer courage and strength from one bearer to another. Trophy taking took literal form in bodily mutilation, especially in the taking of scalps and sometimes entire heads, associated as they were with political rituals that identified the head as a site for conferring honor. For the victim, mutilation underscored trophy taking as desecration, but the victor’s incorporation of the scalp into his battle decorations transformed it into an emblem of his own bravery. Trophies also became focal points of elaborate rituals binding the enemy dead to the victor’s living community. Caddos buried the skulls and bones of an enemy killed in battle in the ashes of their sacred fire, over which the xinesí watched at all times, because they believed that if the fire went out, the Caddo people would die out too. Caddo ritual thus united the enemy dead with their own strength and destiny. Similarly, Spaniards compared the solemnity with which Wichita bands observed scalp rituals to “a religion that takes the form of sacrificing the scalps of their enemies and the first of their own fruits.” The ceremonial combination of trophies of war with products of cultivation recognized the equal importance of military and agricultural success to the survival of Wichita peoples. Despite the range of cultural differences, then, these groups seemed to share a similar warfare culture. Yet, Spaniards did not appear to rank within it.54

In sum, the Norteños at San Sabá never sought a fight with presidial soldiers; when forced to fight, they often stripped their opponents of clothes; they took no trophies; they chose beating as their form of attack; and upon leaving the area, they taunted the soldiers at the presidio who never came out to offer a fight. Combined with the number of people allowed to escape, the individual treatment of Spaniards seems to imply that the allied party of Comanches, Caddos, Tonkawas, and Wichitas did not view Spaniards as worthy of a fight, much less honorable warrior deaths. Rather than killing soldiers with customary weapons of arrow, lance, or gun, warriors beat Spaniards after having removed their battle dress and equipment, thus stripping them of their identity and rank as warriors. Obviously not a soldier, fray Santiesteban would automatically be discounted from such ranks, since opponents had to be warriors of equal skill, but the soldiers received the same ignominious assault. Except for the nine soldiers sent over by the presidio, the presidial forces (quite sensibly, given the odds) mounted no defense of the mission. That left the thirty-one mission inhabitants on their own to offer what feeble defense they could. The situation was not one to inspire the Norteños’ respect for a people already allied with their enemy. If the Spanish soldiers could not fulfill the part of warriors, they would not be treated as such. Every indication implies that once Norteños assumed cowardice and inferiority on the part of their foe, the violence handed out communicated derision and insult.55

La Destrucción de la Misión de San Sabá, oil on canvas, 83 0 115 inches, c. 1763, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City. Courtesy of Ron Tyler. Reproduction authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico City.

Meanwhile, the dominating appearance of this army of Indians had quite the opposite effect on Spaniards, sending shock waves of fear all the way down to Mexico City. It was one thing for leather-armored soldiers to fight Indians armed with bows and arrows; it was quite another to face a force united across multiple nations and armed with guns as good if not better than those of Spanish soldiers. Fray Miguel de Molina noted that one Comanche chief wore a well-decorated red jacket “after the manner of French uniforms.” “Never before,” one of the mission guards argued, “had he seen so many barbarians together, armed with guns and handling them so skillfully.” Colonel Parrilla concluded that the Spanish military in Texas faced a fearful native challenge, in sharp contrast to the “wretched, naked, and totally defenseless Indians of Nuevo León, Nueva Vizcaya, and Sonora.” “The heathen of the north are innumerable and rich,” he argued. “They enjoy the protection and commerce of the French; they dress well, breed horses, handle firearms with the greatest skill, and obtain ample supplies of meat from the animals they call cíbolos [bison]. From their intercourse with the French and with some of our people they have picked up a great deal of knowledge and understanding, and in these respects they are far superior to the Indians of other parts of these Kingdoms.”56