Part Three

New Codes of War and Peace, 1760s–1780s

In July of 1765, Taovaya leader Eyasiquiche led a small, weary party of Wichita men to a Spanish mission named for the Nacogdoches Caddos among whom it stood. Having traveled far to the east of their own lands, he and his men had been riding for some days since leaving their Red River villages. They had stopped along the way at Tawakoni-Iscani villages only long enough to add two Iscanis to the party who could act as mediators with the Spaniards Eyasiquiche was going to see. It had to be a quick trip because allied Wichita warriors, gathering for an expedition against enemy Osages, awaited Eyasiquiche’s return. The Taovaya leader came in search of Franciscan missionary fray José de Calahorra y Sáenz, one of the few Spaniards with whom he had had contact—peaceful contact, that is.

Eyasiquiche and his people—along with neighboring Tawakonis, Iscanis, Flechazos, and Wichitas—had not had much to do with Spanish people to the south; they had little need or desire to. French traders from the east regularly visited their villages and kept them supplied with European goods in exchange for Spanish horses brought to the Wichitas by Comanches and for the hides of bison and deer they hunted themselves. In fact, the Taovayas had moved to the Red River area precisely to position themselves better to participate in trade networks stretching from Louisiana to New Mexico (as well as to distance themselves from Osages). Although they preferred Frenchmen as trading partners, Eyasiquiche knew that various Caddo groups traded with the small Spanish community at Los Adaes as well as with Frenchmen at Natchitoches, and they seemed to maintain good relations with them both. At the urging of Hasinai Caddos, Tawakoni and Iscani leaders living in villages closer to Caddo territory had intermittently exchanged visits with fray Calahorra and other Spaniards settled nearby.1 Those leaders in turn had sought to include their other Wichita relatives and allies, but Eyasiquiche and his men had had to focus on defensive measures against Apache and Osage enemies who raided their villages. Moreover, the Spaniards whom Eyasiquiche was most familiar with were allied with Apaches, making them enemies.

But here he was now, riding to seek out Spaniards—at least some eastern-dwelling ones. Events had conspired to change Eyasiquiche’s view of them. Back in December, he and forty-seven Taovaya warriors with other allies had attacked the San Sabá presidio where their Lipan Apache enemies had found sanctuary and supplies, using it as a base from which to launch raids against Wichita villages. While keeping the presidio under surveillance, they had also witnessed Spanish warriors accompanying Lipan Apache men on buffalo hunts. To Eyasiquiche, the joint ventures further proved the friendly relations uniting Spaniards with their Lipan enemies. And so he and his warriors had raided them. As it turned out, one party they attacked was made up of only Spaniards, four men and a woman. After the first Spanish man had fallen and a second fled, one of the remaining two had killed the woman with two shots of his gun before the Taovaya warriors could stop him, so they in turn dispatched him. Yet, the determined stand made by the fourth man in the face of superior numbers had earned Eyasiquiche’s attention. Eyasiquiche ordered his warriors to spare him because of the valor he demonstrated in defending himself against forty-seven men, even after he received four bullet and two lance wounds.2

At first, Eyasiquiche had thought to add the man to his warrior ranks—permeable ranks that could always use more brave men to help counter Apache and Osage hostilities.3 So, he had brought the injured man home with him to the fortified villages along the Red River that had withstood an assault by Spanish and Apache forces six years before. Eyasiquiche’s new ward was the first Spaniard ever welcomed beyond the high earthen ramparts and deeply dug trenches protecting Taovaya homes. Eyasiquiche thus tried to ensure the man’s reception and security by sending word ahead of the bravery he had shown on the battlefield. Once home, though, the chief discovered that if the battle feat had won the Spaniard his life, what earned him the acceptance of Eyasiquiche’s relatives and comrades was the knowledge they soon gained that he came from the Spanish village at Los Adaes in Caddo territory rather than from San Sabá, where he had been captured. This discovery made sense to Eyasiquiche because the man’s courage proved he could not be “one of those from San Sabá” who always fled like cowards as soon as they saw a war party.4

Eyasiquiche had his Spanish adoptee’s wounds tended, and, over the following months, as they healed, so too did Eyasiquiche’s perception of his enemies change. By summertime, “Despite the great and extreme love everyone felt for him [the Spaniard],” Eyasiquiche decided to send him back to his own home and people as a gesture of friendship. So, they rode east to Mission Nacogdoches, the Spaniard looking like a Taovaya, dressed as he was in their clothes and accoutrements. His transformation back into a Spaniard could await their arrival. There were not many to receive them at the mission—fray Calahorra lived there with two soldiers and their families and some young farm-workers, though Nacogdoches, Nabedache, Hasinai, and Nasoni hamlets lay close by.5

Upon meeting the priest whom his Caddo friends so admired, Eyasiquiche sought to communicate his position with care, explaining via the translations of two Hasinai caddís named Sanches and Canos that this goodwill gesture extended only to the Spaniards “in this part of the country,” that is, those living in and around the Los Adaes presidio and Nacogdoches mission. Eyasiquiche and the Taovayas he represented did not, and could not, seek peace with the Spaniards to the south at the San Sabá presidio and nearby San Antonio de Béxar as long as they continued to associate with Lipan Apaches. Emphasizing this distinction further, Eyasiquiche offered to give the eastern-dwelling Spaniards two cannons left behind by the other, southern Spaniards after the failed attack on his village. He was willing as well to send five other Spanish adoptees, all women and members of his village for a long time, to live instead among the Nacogdoches and Los Adaes Spaniards. Again, though, he would not release them to Spaniards from the south but would deliver them only into the hands of any from Los Adaes who would come for them. When Calahorra asked him why he and his warriors “did not keep the peace with all Spaniards,” Eyasiquiche reiterated that as long as the Spaniards of San Sabá protected and defended Apaches who were his “mortal enemies” and who dared to attack Wichita villages, steal their horses, and capture their women and children, then Taovaya men “could do no less than carry out on those Spaniards all of the hostilities for which there was an opportunity.”6 Although his love and admiration for the adopted Spanish warrior had softened his opinion of Spaniards, Eyasiquiche was going to wait for the Spaniards of San Sabá and San Antonio de Béxar to prove themselves before changing his mind about them.7

The unofficial negotiations between Eyasiquiche and fray José de Calahorra brought about by presidial soldier Antonio Treviño’s brave stand in battle provide a unique glimpse of how some Indian peoples perceived power relations within the region. Eyasiquiche’s decision to differentiate between those Spaniards to the east at Los Adaes and at the Mission of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe at Nacogdoches—who maintained good relations with their Caddo allies—and those Spaniards to the south at San Sabá and San Antonio, who allied with Apaches, suggests that Wichitas and their Norteño allies believed Spaniards to live in bands similar to their own. To their eyes, Spaniards might speak the same language, wear the same clothes, and share the same culture but have individual political identities and affiliations, as did many Indian peoples. And they were not far wrong. The state of the Los Adaes presidio in the 1760s attested to the fact that the small Spanish community existed in a world far distant from the conflicts and hostilities of San Antonio de Béxar and San Sabá. Norteño enmity never descended upon it, and peaceful relations had allowed the garrison to lapse into somnolent disrepair. Indeed, after his 1766–68 inspection, the marques de Rubí recommended that viceregal authorities extinguish the Los Adaes presidio as “worthless” to the defense of New Spain’s northern provinces, a judgment they carried out in 1773.8

From various contacts in the 1760s, Spaniards gained new perspectives on Wichitas as well. Fray Calahorra had brought back the first reports of unstinting Wichita hospitality following a 1760 visit to the Tawakoni-Iscani villages along the Sabine River. There, four chiefs (two from each group) took turns honoring the visiting dignitary with bounteous feasts in their homes over the course of eight days. The hospitality reflected their economic prosperity, evident in abundant fields surrounding the two towns where they pastured fine breeding horses and cultivated maize, beans, and squash. The missionary praised Wichita communal agricultural labor and the equal division of their products at harvest. To protect such “riches of the land,” Calahorra noted, they were building a defensive fort with subterranean chambers similar to that at the Taovayas’ Red River settlement. Meeting with another Taovaya leader who traveled with twenty men and six women to talk with the missionary at the Tawakoni-Iscani villages, Calahorra also learned that they could add at least another 600 warriors to the 250 he estimated lived in the Sabine River towns. This knowledge further solidified Spanish views of the Wichitas as a military force to be reckoned with. On subsequent trips, Calahorra learned more about the Wichitas’ close ties to French traders, noting that a French flag regularly flew over the Tawakoni-Iscani towns and that five French traders from the Arkansas post lived near villages of Taovayas, Iscanis, and Wichitas proper along the Red River.9

Antonio Treviño—the brave soldier saved by Eyasiquiche—offered an even more compelling description of the powerful position Wichitas occupied in the economic and political relations of northern Texas and the Southern Plains. Eyasiquiche had allowed Treviño to participate in all aspects of male village life. Thus, the soldier could provide an insider’s perspective on the military defenses that had humiliated Colonel Diego Ortiz Parrilla’s forces in 1759. Questioned closely by Spanish officials, Treviño described in detail the fortress with its subterranean apartments, within which all the women, children, and elderly could take sanctuary during an attack; the split-log picket surrounding the fort through which men could fire their rifles; the four-foot earthen ramparts that ran outside the palisade as the second line of defense; and the four-foot-deep and twelve-foot-wide trench offering a third and final barrier, designed to keep mounted attackers at a distance. The steady stream of French traders Treviño witnessed there testified to the central place the Taovaya towns held in the region’s trade networks. Frenchmen from Louisiana brought to the Taovayas rifles, ammunition, cloth, French apparel, and material goods in exchange for bison hides and deerskins produced from the hunt, captive Apache women and children taken in war, and horses and mules raided from Spanish settlements to the south. Close ties with neighboring Wichitas and Iscanis meant that their three Red River communities alone could field five hundred warriors. The inner view of Wichita life impressed Treviño (and the Spanish officials who read his reports) with the military and economic power of Eyasiquiche’s world just as much as Treviño’s war deeds had impressed the Taovaya leader with the man’s valor.10

Wichita-speaking peoples had begun a southward migration from the area of present-day Kansas late in the seventeenth century in response to pressure from Osages to the east, who were newly armed with French and British guns, and from Comanches to the west, who were newly mounted on Spanish horses. The Wichitas’ acquisition of horses and guns accompanied their geographical movement and evolved more out of defensive needs than for hunting purposes. Wichita bands with a total population estimated between 10,000 and 30,000 at midcentury established fifteen to twenty consolidated, often palisaded, villages scattered across the northern regions of present-day Texas, concentrating particularly in fertile lands along rivers where they could successfully farm without jeopardizing their defensive capabilities. Although each village remained independent, leaders from larger settlements often exerted influence over others, and a loose confederation linked the scattered towns together, whether they were Taovaya, Tawakoni, Iscani, Kichai, Flechazo, or Wichita proper. Agriculture played a central role in Wichita socioeconomics and tied them to their matrilineal and matrilocal grass-lodge villages for much of the year while women farmed, but they spent the fall and winter in mobile camps when men hunted deer and bison. Yet, it was Wichita trade connections developed over the first half of the eighteenth century with Frenchmen and Caddos to the east and with newly allied Comanches to the west that secured a steady supply of guns and horses as well as critical alliances needed to defend these populous and productive communities against Osage and Apache raids.11

Their Comanche allies represented a branch of the northern Shoshones of the Great Basin region, whose acquisition of horses had led to their rapid evolution into a mounted, mobile military power. During the seventeenth century, they had first moved into the plains of eastern Colorado and western Kansas and then turned south, pushed by Blackfeet and Crows and pulled by abundant bison herds and Spanish horses. Much like the Wichitas, bands of Yamparicas, Jupes, and Kotsotekas had moved into the Southern Plains by the early eighteenth century, operating as independent, kin-based hunting and gathering groups loosely tied to one another in defensive and economic alliances. Yamparicas and Jupes focused their trading and raiding activities in New Mexico, while Kotsoteka bands lived to the east and interacted more with the native peoples of Texas.

By midcentury, these eastern Comanche bands had formed mutually beneficial relationships with Wichitas, allying militarily against common Apache and Osage foes and establishing trade ties that brought Louisiana material goods, Plains hides, and Spanish horses together for exchange. The trade secured both Wichita agricultural products and French guns and ammunition for Comanche communities, while sending a stream of horses and captives taken in New Mexico eastward to Louisiana markets.12 By 1770, Natchitoches diplomat Athanase de Mézières summed up the dominant position of Comanches in the region: “They are so skillful in horsemanship that they have no equal; so daring that they never ask for or grant truces; and in possession of such a territory that, finding in it an abundance of pasturage for their horses and an incredible number of [bison] which furnish them raiment, food, and shelter, they only just fall short of possessing all of the conveniences of the earth.”13

The lucrative political and economic ties among Comanche, Wichita, Caddo, and French traders had developed far from Spanish activity and observation. From 1758 onward, however, these ties commanded Spanish attention. In the wake of Mission San Sabá’s destruction in 1758, Parrilla’s ignominious defeat in 1759, and the ruin of the besieged El Cañón missions by 1767, Spaniards across the province feared for their lives, believing the Norteño allies’ “great acts of audacity and boldness” would accelerate because of evident Spanish weakness.14 And why not? When united, bands of Comanches, Wichitas, Caddos, and Tonkawas could field an estimated total of 10,000 men in comparison to Spanish forces that numbered between 150 and 200 men for the entire province.15 Taovaya and Tawakoni forts offered better fortifications and defenses for Wichita peoples than the leading presidio of Texas, at San Antonio de Béxar, did for Spaniards—a presidio that in 1778 was described by fray Juan Agustín Morfi as “surrounded by a poor stockade on which are mounted a few swivel guns, without shelter or defense, that can be used only for firing a salvo.” Three years later, even the paltry stockade had been destroyed in a storm.16

Echoing the worries within Texas, viceregal officials in Mexico City feared the loss of the entire province. “We shall have, it is undeniable, one day the Nations of the North as neighbors; they already are approaching us now,” wrote the marqués de Rubí in 1768. Not only did he concede that Spaniards could not expand further northward into the “true dominions” of Comanches and Wichitas, he also proposed drawing back Spanish borders with the evacuation of the San Sabá and Los Adaes presidios. In designing a cordon of fifteen presidios to protect New Spain’s dominions—which he located below the Rio Grande—he wanted to locate each fort no more than one hundred miles away from the next one, and the line of presidios was to stretch across the entire length of New Spain’s northern provinces, from Texas westward through New Mexico and Sonora. Rubí only reluctantly stopped short of calling for the abandonment of San Antonio de Béxar and the entire Texas province. Spanish officials also feared British threats to their claims to the Pacific coast of North America, claims they would soon confront by extending settlements there. If won over as allies, Spaniards speculated, perhaps the Norteños could aid Spain in slowing or stopping the British advancement across the Plains. At midcentury, Spanish civil and military officials thereby decided their best option for saving the province was to seek a truce and then diplomatic relations with the formidable Comanche and Wichita nations.17

With new diplomatic goals vis-à-vis the nations of the Norteño alliance, Spanish officials completely reversed their portrayal of Comanche and Wichita men. Warriors feared as barbarous and cruel enemies across a battlefield became men of bravery and valor when sought as allies across the negotiating table. Rubí was one of the first to voice the dual perceptions attached to warrior reputations when he wrote hopefully that the “warlike” Comanches and Wichitas, “whose generosity and bravery make them quite worthy of being our enemies, perhaps will not be . . . [since] they have what is necessary to know how to observe [amicable relations].”18 The ability to crush Spaniards in battle earned Comanche and Wichita warriors the respect of Spanish soldiers and officers. Many Spanish officials in turn envisioned an alliance with the seemingly indestructible Norteños against Apaches as the solution to all their problems. In one swoop, they would transform Comanche, Wichita, and Caddo enemies into allies while destroying Lipan Apaches entirely. Yet, winning over these powerful Indian nations would not be easy.

Local imperatives in the 1770s and 1780s eventually would encourage Wichitas and Comanches to consider Spanish overtures of peace emanating from San Antonio de Béxar. In the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War, Louisiana formally shifted from French to Spanish rule, and the Spanish assumption of control there in 1769, together with stringent new trade policies, began to hamper the steady economic and defensive supplies previously enjoyed by Comanches and Wichitas. Regulations passed that year by interim Louisiana governor Alexandro O’Reilly aimed at cutting off trade in the upper Red River valley that put guns into the hands of native groups in Texas. This policy did not simply represent the extension of New Spain’s general prohibitions against trading guns to Indians, however, but specifically targeted Comanches, Wichitas, and others identified as members of the Norteño alliance whom the Spanish government deemed “hostile.”19

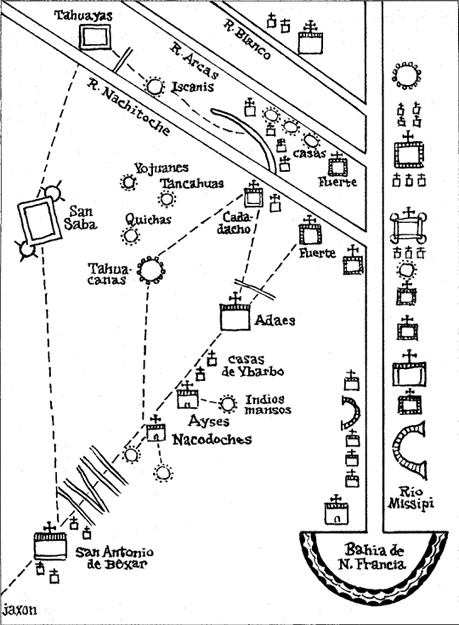

Presidio de San Sabá hasta Adaes, 1763. Diagrammatic map made by Frenchman Pierre Tamoineau for Spanish military commander Felipe de Rábago y Terán at San Sabá in 1763 showing the locations and potential threats of the allied Norteño nations who had been threatening Spaniards since 1758. With a base point at New Orleans, the map indicates the direction and distances of Caddo, Wichita, Yojuane, and Tonkawa settlements in relation to the three Spanish presidios of San Sabá, San Antonio, and Los Adaes and the Taovaya fort on the Red River, where Spanish forces were defeated in 1759. Courtesy of the Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

Modern rendering of the Tamoineau map of 1763. Tracing by and courtesy of Jack Jackson, from Shooting the Sun: Cartographic Results of Military Activities in Texas, 1689–1829 (Austin: Book Club of Texas, 1998).

Trade prohibitions also slowed the eastward flow of hides, horses, mules, and Apache slaves from Texas that had proven so profitable for Comanche and Wichita warriors. In accordance with O’Reilly’s directives, officials in Natchitoches not only forbade trade but recalled all licensed French traders, hunters, and illicit “vagabonds” from their subposts or homes among “hostile” Indians. Spanish officials in Texas counted on the ban to weaken the economic networks of formidable Comanche and Wichita bands whose raids had been devastating horse herds in civil and mission settlements across the province. With such an opening, Texas officials hoped to offer native leaders Spanish gifts and diplomacy in the place of French trade and thus win some breathing space for the province.

In their turn, Comanches and Wichitas faced limited prospects in seeking replacements for the decline in French trade goods. Continued raids on Spanish settlements in Texas to fulfill their horse supply could not fill the gap in arms and material goods formerly provided by Louisiana markets. While French traders associated with the Natchitoches and Arkansas posts remained active covertly and soon British traders began pushing into the region, the trade potential of Spaniards in Texas still began to appeal to Comanches and Wichitas. To build peace out of past hostilities, however, proved a longer and more difficult task than anticipated. Two more years would pass after Eyasiquiche’s 1765 visit before allied Norteños finished off the El Cañón missions, six more years before the first Wichita-Spanish treaty agreement, and twenty years before the first Comanche-Spanish peace accord.