Chapter Five

Contests and Alliances of Norteño Manhood: The Road to Truce and Treaty

The power of the Comanche and Wichita military presence and their trade ties with Caddos and Frenchmen momentarily had led desperate Spaniards and Apaches to seek one another’s aid against this united foe in the 1750s and 1760s. The strength of their foe, however, had just as quickly torn apart that tenuous alliance when Spanish officials decided to abandon the Lipan Apaches and negotiate with Comanche and Wichita bands instead. From the Comanche and Wichita perspective, Spanish communities in Texas had held little relevance before their relationship with the Lipan Apaches brought the Spaniards to their attention as new enemies and thus new targets for raids. When, in the 1770s and 1780s, some reason to establish peace arose, their hostile history would make efforts to replace enmity with diplomacy that much harder.

When the Spaniards approached this new set of potential native allies, Caddo, Wichita, and Comanche standards of diplomacy set the rules, as had those of previous groups. Male-dominated rituals shaped through militarization increasingly defined politics in the province as well as regional European and Indian economies, governing systems, social hierarchies, and ceremonial lives. In ranked societies like those of the Comanches and the Wichitas, prestige circumscribed men’s social status. Through war deeds, raiding coups, generosity, and medicine power (what Comanches called “puha”), men gained honor that in turn translated into authority, access to status positions, and standing in their relations with other men. Puha and generosity were intrinsically tied to a man’s achievements in raids and war, since those activities supplied the goods, horses, or captives by whose distribution he demonstrated his generosity, while medicine power was requisite for and reflected by war honors. Men’s generosity not only tied people and families to each other; it enhanced the men’s standing and that of their kin in the eyes of others. By extension, personal or medicine power was the foundation of rank and relations between men. As Athanase de Mézières wrote of Wichita leaders, “they pride themselves on owning nothing, and, as they are not recognized as chiefs except in recognition of their deeds, the most able and successful warrior is the one who commands, authority falling to him who best uses it in the defense of his compatriots.” Among Caddos over the eighteenth century, men’s war deeds came to hold more sway within the cultural categories determining male rank and status, as horses and guns offered new routes to social distinction for men and as the basis of status positions shifted from sacred to secular authority and from heredity to individual achievement. Though Spaniards at the beginning of the century had imagined Caddos primarily as peaceful agriculturalists, Caddo men inspired one Anglo-American agent at the end of the century to compare their martial spirit to that of the Knights of Malta.1

During this period, Spanish government structures also reflected the region’s increasing orientation toward war. Inspections of Spanish defensive capabilities across the far northern frontier in the 1760s led to the designation of the two Californias, Sonora, New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, Texas, and Coahuila as the “Interior Provinces” in 1776, all placed under the command of a military governor (entitled “commandant general”). Within Texas, as in other northern provinces, governors came from the military, ensuring that judicial, civil, and military authority rested in the hands of officers of the rank of colonel or lieutenant colonel. This culture of militarism led even Spanish missionaries to cast their work as manly and virile, arguing that religious conquest was itself a battle and a martyr’s death as heroic and valorous as that of a soldier in war. But missionaries would not be called upon anymore. During the 1770s and 1780s, officials secularized New Spain’s “Indian policy”; the state would no longer rely on missionaries or religious considerations to determine the course of negotiations with Indian nations. The takeover of Louisiana influenced these policy shifts in the northern provinces, as Spanish officials tried to emulate their successful French rivals by reversing former prohibitions denying guns and ammunition to Indians, by making it standard practice to employ French traders as mediators and translators for all negotiations with Indian leaders, and by instituting formal gift and trade supply lines to allied Indian nations.2

Because of these transformations within Spanish and Indian leadership ranks, individual men could exert significant influence over diplomacy—a certain power of personality prevailed. Consensual politics among Comanche, Wichita, and Apache bands demanded that leaders demonstrate not only bravery and fighting prowess but also the foresight, wisdom, and charisma reflective of personal puha, or medicine power. The capacity of individuals to determine the success or failure of diplomatic endeavors was even more critical to Spaniards, given their weak position vis-à-vis their Comanche, Wichita, and Apache counterparts. War or peace might hinge on certain men’s ability to relate to Indian leaders, to convey respect, and to solicit trust. In the 1770s and 1780s, Athanase de Mézières, Juan María Ripperdá, Domingo Cabello, and Rafael Martínez Pacheco, for better or worse, swayed the political pendulum by their very personalities. Ripperdá and Cabello were both outsiders—formal military men for whom Texas was an undesirable posting. Yet, while Cabello’s old-school military mind-set made him cautious and deeply suspicious of Indian diplomats, Ripperdá’s internationalist outlook meant that he was far more open to working with French officials in Louisiana as well as with Caddo and Wichita leaders. Mézières and Martínez Pacheco were products of the borderlands, having lived and worked closely with numerous Indian peoples in a variety of settings in Louisiana and Texas, respectively. Mézières had such singular standing among Caddo and Wichita leaders that his death in 1779 nearly derailed the diplomacy of both provinces. In the years that followed, San Antonio officials struggled to fill his place by bringing a number of former French traders and translators into the Spanish diplomatic core—just to replace one man. The evaluation of individual male interactions—across negotiating tables rather than battlefields—thus became all the more personal in these later years.3

In a sense, Spaniards were back at square one by 1770—seeking first contacts with which to begin building diplomatic relations—though they did not enjoy the clean slate of 1690, but a bloodied one, stained by mutual violence. When representatives of the Spanish, Comanche, and Wichita nations met, they entered negotiations with grievances or demands that flowed from earlier raids and battles. Recognizing past Spanish misdeeds, the San Antonio cabildo worried about the lack of a foundation upon which to build peace in the 1760s, arguing that many of the Indian nations with whom Spaniards had warred “are naturally prone to break relations and are persuaded to do this by the merest breeze that brings to their remembrance the death or captivity of some son, mate, or parent that will stimulate that lust for vengeance to which they have such inclination and propensity.” And Spaniards too had their own grievances. The only common ground therefore was one of shared tension and mistrust.4

The language of diplomacy used by Comanche and Wichita leaders rested upon highly masculine and militarized terms of warfare to an even greater degree than that used by Apaches. By symbol and rhetoric, protocols had to establish a mood and a situation in which men would open themselves to the negotiation itself. Rituals of respect functioned as the redemptive erasures of past slurs on the battlefield. Turning truce into alliance in this hostile situation meant diplomacy took its most powerful form in military commitments. Thus, pledges to fight jointly against common enemies (primarily Apaches) dominated diplomatic discussions among Spaniards, Caddos, Wichitas, and Comanches. Rituals and gifts that followed lent a further martial air to negotiations, transforming fellow warriors into comrades and brothers. To forge bonds that could join rather than separate men on the battlefield, Comanches and Wichitas also appealed to a language of military titles and male kinship. Warrior prestige found expression in titles of “captain,” “medal chief,” and “capitán grande” as Spaniards and native men endeavored to extend respect to each other. Such exchanges often occurred with little shared understanding of the meanings each group read into them, however, and ignorance yet again could work to everyone’s benefit. Each man could interpret the exchange as he was wont to do and walk away pleased.

Many times over the 1770s and 1780s, Spaniards feared their willingness to discuss peace might appear to be a sign of weakness or cowardice, particularly when they themselves viewed valor as synonymous with a “disposition to carry on offensive warfare and to defend [oneself].” Diplomat Athanase de Mézières questioned orders to seek peace with “haughty” Comanche warriors, writing, “Why should I go? . . . To fondle and protect barbarians whose crude understanding would ascribe our conduct to fear?” Yet, fear did define Spanish views of Apaches, Comanches, and Wichitas, as well as their view of the future of the province. In 1777, the commandant inspector of the interior presidios, Hugo O’Conor, argued that, of all of New Spain’s northern provinces, Texas held the greatest strategic importance as the sole bastion against the French and the British, but that it had also been the most costly, of least use, and “produced the most hostilities.” Apaches, he explained, were “every one of them enemies of our provinces” and thus the “most feared,” Comanches ruled as “lords of the wide land,” and Wichitas had been provoked repeatedly into war by Spanish mistreatment. Thus, as Teodoro de Croix expressed it, provincial officials had to use diplomacy as a means of “gentle persuasion which they [Native Americans] could never attribute to our weakness.” Or, as Mézières put it, a diplomatic alliance with Indian leaders should function “to obtain from their aid the benefit promised, without giving them reason to think that we depend too much upon it.”5

Meanwhile, Caddo, Wichita, and Comanche men still did not have much reason to seek out Spaniards as allies—they had little to gain from them, and so they set the bar high for Spanish proofs of commitment and value as “brothers.” More often than not, as Spaniards tried to walk the fine line set for them by these dominant Indian nations, they erred by not paying due attention to the rules of a diplomacy in which they had little say. Because war so overshadowed the negotiations, honor was at risk, and peace remained contingent upon the precarious expressions of respect and reciprocity fundamental to native systems of alliance. Negotiators maintained a constant vigilance against perceived insult in the behavior or words of others. As a result, diplomatic relations that were difficult to achieve proved even harder to maintain, and a return to the battlefield often seemed likely. In such a context, Spanish failures to understand native codes of honor could very easily become acts of war. The actions of men therefore had to bring Wichitas and Comanches to a negotiating table with Spaniards, but as will be seen in Chapter 6, women provided the seal by which they did or did not cement the agreements made at those tables. Thus, Chapters 5 and 6 each take up a different half of the gendered politics that ruled the diplomacy of the 1770s and 1780s.

At the end of 1769, Caddos took the lead among their Norteño allies in establishing the terms by which newly established Spanish representatives from Natchitoches might assume the standing previously enjoyed by French officials within Caddo economic and political networks. At the diplomatic level, Spanish officials hoped to gain new kinship roles among Caddo leaders using political gifts and commercial trade. That is, they wanted the ties that Caddos had formed at the local level with their Spanish neighbors around Los Adaes and the nearby missions to be extended to the entire province of Texas. Although the strengths such ties provided at the local level were clear, Spanish officials did not always see the evidence for what it was. In the midst of critical reports on the state of Spanish institutions in east Texas, commandant inspector Hugo O’Conor noted that “the land [around Los Adaes] is one of those on which the Lipan, Natages, and other Apache Indians have never set foot either in time of peace or in war,” and Nicolás de Lafora observed that the “savage tribes . . . are troublesome only at San Antonio de Béjar. . . . They never molest the presidio of Los Adaes.” Why not? Because the Spanish soldiers and settlers there enjoyed the alliance and protection of Caddo warriors. Officials did not need to worry about defending the Spanish settlement there, because Caddos took care of it. Inspectors might complain that the Los Adaes presidio lacked operable arms, with its mere two cannons in total disrepair and only two rifles, seven swords, and six shields for sixty-one soldiers; that the men wore nothing resembling a military uniform and were without the proper hats, coats, shirts, and shoes; and that the company lacked “everything necessary to carry out its obligations.” But Spaniards’ obligations at that villa and presidio did not lie in defense; instead, they maintained obligations of trade and alliance with Caddos and, in circuitous fashion, gained needed defense in return.6

Echoing Wichita distinctions among different Spanish communities, Caddos’ relations with Los Adaes residents had remained firm, but they viewed those at San Antonio with suspicion because of their Apache alliance. After the Louisiana cession, then, Caddo leaders chose not to approach Texas officials but instead worked through those at Natchitoches to convey their understanding of the shift in governance among their European trade allies. In effect, they were able to negotiate treaties with the new Spanish government of Louisiana that strengthened trade ties despite the new restrictions established by Governor O’Reilly. Although Caddos had participated in the raids against Apaches and the attack on San Sabá, the Spanish governments of Texas and Louisiana knew they could not enforce the trade prohibitions against “hostile” Wichitas and Comanches without Caddo aid.

The new commandant at Natchitoches, Athanase de Mézières, could ill afford to alienate Caddo leaders—their trade alliance was too important to the economies of both the Natchitoches post and the Louisiana colony, and their political alliance was crucial to the maintenance of peace in the region. He moved quickly to maintain diplomatic goodwill and the exchange of deerskins, bison hides, and bear fat for European material goods. This two-pronged strategy required two different lists of goods, one of the annual gifts that would be given to different Caddo confederations, the other of goods that licensed traders would contract to exchange in Caddo villages throughout the year. The two inventories shared many things in common, listing muskets, powder, musket balls, and gun flints to keep Caddo arms well supplied—notably, 89 muskets, 834 pounds of powder, 1,868 pounds of balls, and 2,000 flints. They also both included tools of daily life such as hatchets, knives, awls, kettles, mirrors, blankets, and red and blue Limburg cloth. Yet, other specialized goods designated on the “annual present” lists clearly targeted the need to solidify relations of honor between Caddo and Spanish leaders. Although much of the highly structured ceremonialism required by Caddo custom in their contacts with Europeans at the beginning of the eighteenth century had waned, the reciprocity of gift exchange had not. The gifts too reflected the militarization of Caddo leadership ranks: the theocratic position of the xinesí had disappeared, and the criteria for selection of caddís had shifted to battlefield strength and valor. Gifts of clothes marking male rank had become more elaborate so that caddís now received military uniforms, including hats trimmed with feathers and galloons (lace, embroidery, or braids of metallic thread), ornamented and laced shirts, flags, and ribbon with which to wear honorary medals.7

To convey that the Caddos accepted Spain’s assumption of France’s political obligations—that is, annual presents and the provision of licensed traders—Tinhioüen, a principal caddí of the Kadohadachos, and Cocay, a principal caddí of the Yatasis, traveled to Natchitoches in April 1770. Upon arrival, Tinhioüen and Cocay were feted in a solemn ceremony before an assemblage of Spanish officials, during which they received the king’s “royal emblem [a flag] and his august medal with the very greatest veneration”—each silver medal had on one side a portrait of the king with the legend “Carlos III, King of Spain and emperor of the Indies,” and on the other the words “In Merit,” surrounded by laurels.8

Key to the Caddos’ acceptance of such formalities, however, was that many of the assembled representatives of the Spanish government were the same Frenchmen they had long known and deemed kin. Mézières, a French soldier and trader now appointed commandant at Natchitoches, had married the daughter of Louis Juchereau de St. Denis, the French founder of Natchitoches back in 1716. Mézières enjoyed not only the benefits of inclusion within the powerful French family but also, by extension, their standing among Caddos as adopted kin. Indicating the central role these Caddo-related Frenchmen would play, Alexis Grappe stood beside the two Caddo leaders as their interpreter at the ceremony. Grappe was a trader and translator who had long lived among Kadohadachos at Fort St. Louis de Cadodacho, a trading post established at their central village along the Red River, with his wife, Louise Marguerite Guedon (daughter of Frenchman Jacques Guedon and Chitimacha Marie Anne de la Grand Terre), and their children. In addition to Grappe, Pierre Dupin (one of the other Frenchmen licensed to trade among Caddo villages) and Juan Piseros (the merchant who supplied traders in exchange for the products of Caddo hunters) also attended, representing the continuity of economic relations that bound the Caddo-Natchitoches communities together.9

In the ceremonial exchanges, Tinhioüen and Cocay promised that their men would continue “to employ themselves peacefully in their hunting,” while the leaders would turn over any illicit traders to Spanish officials. They thus assured those same French merchants and traders that valuable bison hides, bear fat, and most important, deerskins would continue to flow into Natchitoches warehouses. More critically, the two Caddo leaders “engaged to aid with their good offices and their persuasion, in maintaining the peace.” Tellingly, one of the ways in which Natchitoches officials requested the aid of Tinhioüen and Cocay was by asking them to curtail the arms trade with their Wichita and Comanche allies until the Texas government could forge a truce with them. Spanish officials clearly recognized that such a pact would not be achieved without Caddo help, and fewer than six months later, when Tinhioüen had put a peace process with the Wichitas in motion, Mézières attested to his superiors that indeed the “great loyalty of its inhabitants and the importance of their territory” made Caddos the “master-key of New Spain.” As key mediators in brokering an accord between Spain and the numerous and powerful Wichita bands, Tinhioüen, Cocay, and later, Hasinai caddí Bigotes increased their leverage and status even further.10

Some ritualized ceremonies could not so easily accomplish the transition from French to Spanish diplomacy, however. If Spaniards failed to follow native dictates previously accepted by Frenchmen in day-to-day interactions, Caddo leaders willingly resorted to threats or acts of violence to enforce their economic and political authority. In 1768, for example, when soldiers under the new commandant inspector of presidios based at Los Adaes sought to arrest a Frenchman named Du Buche while on his way from Natchitoches with merchandise for Yatasis, principal men of the village reacted vigorously. Du Buche had lived and traded among them for years, and they were not about to lose a man they deemed a valuable trader and a kinsman who had long maintained his obligations. A caddí named Guakan quickly assembled his warriors to attack Los Adaes in response to this Spanish affront to relations of honor. Only the intervention of another Frenchman, Louis de St. Denis (son of Louis Juchereau de St. Denis) forestalled the planned assault. Luckily for the Spaniards, Guakan went to St. Denis’s home, perhaps calling on him as kinsman to join the gathering warriors, and St. Denis instead dissuaded him from war, healing the diplomatic breach with presents to restore a reciprocal balance to the disrupted exchange.11

A life-and-death drama played out two years later when Kadohadachos tried to win the freedom of an adopted kinsman, thirty-five-year-old armorer and gunsmith François Morvant, who had lived among them for seven years. In 1770, Morvant responded to the official recall of all Frenchmen living in native villages but, upon reaching the Natchitoches post, was arrested for murder. Ten years before, in a heated altercation, he had killed the leader of an infamous band of illegal hunters and trappers based north of the Arkansas post. Fleeing for his life out of fear of the band’s revenge, he had wandered for three years along the Arkansas River, until Kadohadachos found him so ill and near death that they took the young Frenchman back to their village to care for him. As he regained his health, Morvant also gained the status of adopted kin and, though his presence at the principal Kadohadacho village was known to French officials, none tried to arrest him due to the protection he enjoyed there. When Tinhioüen and the principal men of the village learned that Morvant’s good-faith effort to abide by the recall in 1770—a decision they had urged him to take out of respect for the diplomatic agreements with their newly accepted Spanish allies—had threatened his life, they promptly went to negotiate his case with Mézières. Tinhioüen laid siege to Mézières and with great insistence pledged not to leave his side until Morvant was given his freedom. Clearly, his authority mattered, as Mézières and a council of Natchitoches officials decided after long meetings that they could ill afford to “displease an Indian of such good parts and distinguished services.” Mézières released Morvant back “under the protection” of Tinhioüen, a decision his superiors found a “very strange” contradiction of Spanish laws. Indeed, a top-down view of Spanish policy misses on-the-ground necessities within the kin-based world in which the Spaniards had only a tenuous place.12

The first meeting of Spanish and Wichita leaders, organized by Tinhioüen in the fall of 1770, clarified the Spanish government’s diplomatic dependence on the bonds of kinship formed between Caddo and French men. The Spaniards had no means of approaching Wichita peoples; no banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe or inclusion of women in a traveling party would suffice to convey peaceful intent after decades-long enmity. So, the Spaniards relied on the aid of male mediators, as Caddo leaders helped them to gain a hearing with the Wichitas. Tinhioüen had assiduously traveled to meet with his Wichita counterparts, leading men from different bands of Taovayas, Tawakonis, Kichais, and Iscanis, to propose meetings with the Spaniards. He offered as neutral ground his own Kadohadacho settlement for the site of such talks. Once he had persuaded them to hear the Spaniards out, Tinhioüen summoned Mézières and sent three leading men to escort him from Natchitoches to join seven leaders from different Wichita bands who had already assembled at Fort St. Louis de Cadodacho in his village. Mézières went at his bidding without waiting for the permission of his superiors, sure in the knowledge that if he failed to attend, the Wichitas and Caddos “will become disgusted, attributing [the nonappearance] to fickleness and lack of courage on my part . . . making difficult and even impossible their congregation and conquest in the future.”13

Of first importance was that Natchitoches officials incorporate Spaniards into the Caddo-French kin ties that had long bound Caddos and Frenchmen in relations of honor. The language of European treaty-making lent itself to Caddo appeal, as officials asserted the “sacred ties of consanguinity” that now united Frenchmen and Spaniards under the (Bourbon) family compact. Mézières carefully selected the members of his traveling party to convey symbolically to Wichita and Caddo men a new “brotherhood” between Spaniards of Texas and Frenchmen of Louisiana. A sergeant and four soldiers from the Los Adaes presidio as well as a Spanish missionary joined a sublieutenant and five people from the Natchitoches post in the trip to Tinhioüen’s village. At the October conference, Mézières pointed to the Spanish flag flying above the proceedings, using the symbolic object to assert that Wichita leaders “could not doubt, in view of that respectable flag which they saw hoisted, that we [the French] had become naturalized as Spaniards.” To establish the Spanish king as a man and ruler worthy of the alliance they had previously maintained with the French king, Mézières assured them of the “immense power” of the Spanish king, a man who wished them to become “brothers” of his other subjects. In his most potent statement, Mézières insisted to the listening Wichitas—listening through the translations of Alexis Grappe, because they too spoke the Kadohadacho dialect—that they could not have peace with Natchitoches and war with San Antonio. Taking the hand of each of the Spaniards standing near him, Mézières asserted that “the very name of Frenchman had been erased and forgotten” and that “we were Spaniards, and, as such, sensitive to the outrages committed [referring to San Sabá and El Cañón] as we would be interested in avenging them as soon as they might be resumed.”14

Yet, as Wichita leaders gravely explained in the Kadohadacho language, the Spaniards’ proven alliance with Apaches had made them targets of their hostility; it had nothing to do with Spanish-French relations. They had been attempting to make this point clear to Texas Spaniards since 1760. In fact, they pointedly asserted, their warriors had long known the location of the numerous horse and cattle herds of Spanish ranches, villages, and presidios and had never raided them until the Spaniards made themselves enemies through their aid to the Apaches. Concluding simply, the Wichita spokesmen avowed that they put their confidence in their ancient protectors, the French. Ritual behaviors surrounding the proceedings echoed this sentiment. Fray Miguel Santa María y Silva complained to superiors that he found it significant that as the calumet pipe repeatedly went around the circle of dignitaries—a pipe he knew to be “the chief symbol and the surest sign by which these people signify peace and show the tranquility and love of their hearts”—it bypassed him and the other Spaniards, despite his position beside Mézières and the others’ positions mixed in with the Frenchmen from Natchitoches. Even when they traveled through allied Caddo settlements where they were greeted with the Spanish flag, Caddo leaders regularly welcomed the Frenchmen with “much friendliness,” while displaying little but “an indifference which I cannot express” for him and his fellow Spaniards.15

In turn, Mézières exacerbated the Wichita headmen’s frustration by asking that they go to San Antonio de Béxar in order to “humble yourselves in the presence of a chief of greatest power who resides there [the governor of Texas],” if they wished to ratify a peace agreement. Essentially, he attempted to shame the Wichita men. Mézières compared them unfavorably to the Kadohadachos, who had demonstrated their bravery by repelling the Natchez attack on Natchitoches in 1731. In contrast, the Wichitas’ hands were stained with Spanish-French blood (which was now the same), having “exultantly beheaded” a helpless missionary at San Sabá. To give “full evidence of humility and repentance,” then, was the only answer for the “insults, robberies, and homicides” committed by Wichita warriors in the San Antonio vicinity. Not surprisingly, the chiefs “refused entirely to comply.” They would not even accompany Mézières to Los Adaes as a demonstration of good faith to Spaniards. Although their immediate explanations for the refusal ranged from a lack of horses for travel to the lateness of the season, their politeness could not disguise that the Wichita men clearly were not going to sacrifice their honor on an altar of Spanish pride. Mézières tried to tempt them with the presents that awaited their acceptance of peace, and again the leaders “unanimously and without perturbation” said no. Finally, as a last resort, Mézières tried to cow them with the threat that their refusal “would bring upon themselves the imponderable weight of [the king’s] arms,” but considering the categorical defeats already suffered by those arms at Wichita hands, such claims were wishful thinking at best.16

To Spanish officials, the Wichita leaders’ reluctance to accede to their wishes conveyed a dishonorable failure “to make any true sign of peace.” Although Luis Unzaga y Amezaga, the governor of Louisiana, wrote that Spaniards could not expect Wichita men ever to approach them in good faith, “because our lack of deeds cannot fail to estrange them, for words unaccompanied by acts do not suffice,” he still saw a threat to Spanish political standing in the region if they gave in to the Wichitas. Thus, when Mézières proposed to follow up by visiting Wichita leaders in their own villages with diplomatic gifts, the governor forbade it, because “this favor may not be conferred without strong proofs of fidelity and merit, lest the dignity of our nation be exposed to outrage.” Mézières repeated his request to visit the Wichita villages five months later, and again Unzaga y Amezaga refused him. Negotiations over male honor were derailing political discussion.17

Spaniards had not heard the last from Wichita leaders, however. In the spring, they sought to reopen talks, sending overtures through their Caddo allies to contact the Frenchmen representing the Spanish government in Natchitoches. Hasinai caddí Bigotes arrived at the Louisiana post in the late spring of 1771, bringing two painted bison hides conveying a peace message from Wichita leaders. They had painted one of the hides entirely white to symbolize the end of war, so “that the roads [between Wichitas and Spaniards] were open and free of blood.” The other they had painted with crosses, one for each of the bands of Taovayas, Tawakonis, Iscanis, Kichais, and Wichitas proper, having chosen the symbol of a cross because they knew it to be an “object of greatest veneration” among Spaniards. The two skins cast the Wichita and Spanish nations as equals in their truce without bowing to the Spanish desire for deference. Mézières recognized the hide treaty to have the “force of a contract” and called on the principal citizens of Natchitoches to attend a public reception in honor of Bigotes, the “considerable following of friendly Indians” accompanying him, and the welcome news they brought.18

Tawakoni couriers followed Bigotes to Natchitoches, and leading Taovayas working with Tinhioüen arrived at the post a month later with a diplomatic solution to the quandary facing the Wichita men. Since acts of violence had initiated Wichita-Spanish contact, they offered to disown the trophies from that violence as a codification of peace. Rather than humble themselves before the Texas governor, the Taovaya men offered to return two infamous trophies of war to the Spanish government: the cannons seized from Parrilla at the Red River in 1759. They had been offering them as a goodwill gesture off and on since 1760, but no one as yet had accepted. Now the Wichita men transformed the return of trophies of war into a gesture of alliance in the belief that their retrieval could redeem the dishonor their loss had meant for the Spaniards. Such thinking resonated with the Spanish men. Unbeknownst to Wichita leaders, Spanish officials for years had suffered angst over the retrieval of the cannons—not out of practical consideration for the Taovayas’ potential use of them as weapons, but rather because of the cannons’ symbolic importance to injured Spanish pride. Provincial officials wrote of Parrilla’s expedition as a “shame to our nation” and “disgrace to our arms.” Atonement might indeed be found in the restitution of these symbols of Spanish ignominy. And, as it turned out, in the formal treaty that finally emerged, the return of the cannons held equal place with the return of Spanish women still believed to be living in Taovaya villages.19

Nevertheless, the treaty negotiations that followed still hinged on the tensions of warriors seeking a means to maintain valor away from the battlefield. The peace could not require the sacrifice of warrior identity by either Spanish or Wichita men. Taovaya warriors promised to check in at the San Antonio de Béxar presidio if they passed that way in pursuit of Apache raiders, both to give notice of their intentions and to enjoy Spanish hospitality and entertainment. A Spanish flag given to them as a passport would ensure their welcome. In return, the Spanish military alliance would come in the form of a presidio built in Wichita lands—a proposition Taovaya leaders viewed as having some merit, since a presidio might bring arms and men that could supplement their forces against Osage raids. The final treaty stipulation promoted the idea of warriors no longer separated by war but united as allies by declaring that “as visible evidence of the reliability of their word, the war hatchet shall at once be buried by their hands in sight of the whole village, and that he who again uses it shall die.” To enact such ritual language, Spanish soldiers and Wichita warriors each buried a hatchet, one at the site of the meeting in Natchitoches and another six months later in San Antonio.20

Although Wichita headmen had willingly met with Mézières in Natchitoches to draw up the treaty, it was Hasinai caddí Bigotes who first went to San Antonio as their proxy representative carrying messages of peace for Governor Ripperdá. So, it was to Bigotes that Ripperdá extended the first military honors from the Texas government. In order to thank him for his invaluable aid as mediator and to tie the chief to Spanish Texas, Ripperdá “named him and armed him” as a capitán grande, decorated him with yet another royal medal and a military uniform, and did it all “in the presence of the portrait of the king, the troops under arms, and the principal personages, ecclesiastical and secular, the act being solemnized as well as was possible.” The Caddos appeared to respect these Spanish rituals of manly honor.21

Yet, acceptance of Spanish ritual could not be mistaken for acquiescence to Spanish power. Rather, honors were the means by which the groups could understand each other, whether in war or peace—at least well enough for now. More Wichita protocols followed as well. First, five Taovaya men with two chiefs traveled to San Antonio the following spring of 1772, carrying a Spanish flag emblazoned with the cross of Burgundy (given them in Natchitoches) to get them safely into the Spanish capital. Chief Quirotaches and Governor Ripperdá formally buried a war hatchet and exchanged diplomatic presents. Two months later, five chiefs and many principal men from Kichai, Iscani, Tawakoni, and Taovaya bands arrived to assert a balance of authority between their nations and that of Spaniards through Wichita rituals. In a public meeting formalized by an audience of four missionaries, two presidial captains, and San Antonio’s cabildo, the five headmen recognized Ripperdá as a fellow “chief” by performing a sacred feather dance, reciting prayers, and calling on the “creator of all things” to bless their Spanish counterpart and the peace he had just sworn with them. Like earlier French traders and diplomats had experienced, Governor Ripperdá found himself wrapped in feathers and bison hides to symbolize his new status among Wichitas. Such physical decoration held political import among Wichita men, who used it extensively to denote honors attained through the course of life, from tattoos on their hands that marked their first hunting achievements as boys to ones across their chests and arms that commemorated acts of valor. Thus, Ripperdá entered the dispersion of leadership within Wichita bands.22

Meanwhile, Spanish officials used a language of military titles to recognize the Wichita headmen as capitanes grandes. Some Spaniards wished to believe that such ceremonies authorized them to choose native leaders and command the selected leader’s subordination to the Spanish government through oaths of allegiance. From the perspective of Caddo, Wichita, and (later) Comanche men, however, the Spanish practice of handing out titles may have fused instead with two separate but interlinked native customs—one distinguishing men of battle valor with special names and another rewarding those same men with titles and positions of leadership. Comanche and Wichita men adopted names signifying war deeds by which they had earned reputations as men of valor. Comanches also chose names to reflect the qualities associated with male honor. Among Caddo bands, noted warriors who had achieved distinction in war earned the name amayxoya, translated as “great man,” and war chiefs were chosen among men distinguished for their acts of bravery. In other words, men from these bands likely viewed Spanish titling ceremonies as expressions of due respect. They also judged Spanish protocol by French precedents, and Frenchmen in western Louisiana had long offered similar deferential titles, such as “captain,” without claiming any form of authority over them.23

Spanish officials also began to accept diplomatic protocols of male kinship that Caddos and Wichitas had used with the French. To establish any kind of meaningful relationship—be it social, economic, or political—Caddo and Wichita leaders extended kin designations to those with whom they interacted. Appealing to obligations of kin, for instance, Wichita men often addressed the Spanish governor’s relationship to a band as that of a “father.” Spaniards wistfully envisioned the role of “father” as one of patriarchal authority to discipline, accompanied by the Wichitas’ filial responsibility to obey. Spanish officials therefore referred to the governor’s or king’s affection for “his children,” asked Wichitas to be “obedient sons,” and couched their exhortations and directives as those of a loving or true “father.” Athanase de Mézières, for instance, wrote of the achievement of peace as the transformation of Wichitas into “children” of the Spanish king.24

Wichita and Caddo men, in contrast, held a different understanding of the obligations invoked by familial metaphors. The forms of address that had worked with their French trading partners in Louisiana were not quite so simple or direct in meaning as Spaniards might have hoped. Frenchmen’s assertion of the title and role of “father” often did not carry with it much influence, because many of the native groups with whom they maintained relations had matrilineal kinship systems in which the role of father had little authority. The Caddos and Wichitas were just such matrilineal societies, with the primary male authority figure in the family being the eldest maternal uncle rather than the father, so the paternal role assumed by a Spanish governor came with little power. In fact, the very absence of authority may have made such French designations appropriate. Europeans might become kin, but only in related, not direct, lines of influence.25

In contrast to Spanish officials’ expressions, Caddo and Wichita men never referred to themselves by the diminutive term “children,” even when designating the Spanish governor a “father.” In a 1780 letter to Commandant General Bernardo de Gálvez, for example, Taovaya chief Qui Te Sain repeatedly addressed the commandant as “my father,” but the only ones identified as his “child” and “children” were the Spanish representative sent to Qui Te Sain’s village and the Spaniards of Texas, respectively. It was not for rule, direction, or dominion that Wichita chiefs looked to Spanish governors and commandants as “fathers,” but for more practical needs of economic trade and military alliance—needs which firmly established Spaniards in a role of reciprocal yet distant male standing—in a sense, as fictive members of a father’s clan.26

When metaphors of family bonds expressed diplomatic ties, Wichita and Caddo men more often called upon a language of “brotherhood,” particularly between soldiers and warriors. Yet, again they meant “brothers” in a distinctly native understanding of that male relationship. Spanish observers noted that men among Nacogdoches, Hasinais, Nasonis, and other groups making up Caddo confederacies “treat one another as brothers and relatives,” thus “they are always united in treaties of peace, or declarations of war.” Among Caddos, two men who fought side by side in battle might afterward consider one another in a special category of friend, “tesha,” which carried connotations of brotherhood. In similar fashion, “brother” conveyed bonds tying together various networks among men of Taovaya, Tawakoni, Kichai, and Iscani bands as well. By providing Spaniards with such kin designations, Caddos and Wichitas also provided the framework of terms and conditions within which they expected Spaniards to operate. The key seemed to be that family metaphors functioned well as false cognates. Both groups could use a language of kinship in ways that fit their own needs while unknowingly pleasing the other. Spaniards linked kinship to deference, dependence, and patriarchal hierarchy, while Caddos and Wichitas linked kinship to ideas of a balance between obligation and autonomy, with authority deriving from generosity and talent. But as long as Spaniards appeared to conform to native protocols, diplomacy worked.27

Honors, titles, and treaties meant little if the symbolic alliance was not confirmed by actions in accordance with the obligations of brotherhood, however, and in the years following the accords of the early 1770s, relations between Wichitas and Spaniards faltered. Negotiations over the terms of their alliance focused on three obligations Spaniards seemed unwilling or unable to fulfill: a presidio and settlement in Wichita lands, gifts and trade, and a military alliance against Apaches. Spanish officials had promised to institutionalize gift giving in annual ceremonies and to provide villages with resident licensed traders to replace former French trade networks. The “gifts” that concerned the principal men among Caddo and Wichita bands were not prestige items or medals but critical supplies of arms and ammunition. Yet, the Spanish government’s financial woes, turnovers in Spanish officials, and thus unstable diplomatic policies meant that these promises often went unmet in the 1770s and 1780s. In turn, Wichita and Caddo leaders understood the failure to uphold gift and trade obligations not only as diplomatic slurs but also as threats to their economic well-being and military survival.

Wichitas had first wrangled for a presidio that they hoped would ensure military provisions and economic trade. If, as Wichita leaders proposed, Spanish citizens also settled nearby, then the Spanish government would be even more compelled to guarantee that defensive and trade supplies regularly flowed into the area. Spanish diplomatic gift giving and economic trade networks were to replace not only French goods but also what Wichita men had previously taken as booty in raids on Texas ranches and presidios. Daily exigencies determined their choice between trade and raids, and if Spanish leaders could not uphold promises of the former, then Wichita leaders would have a difficult time restraining their warriors from returning to the latter. Raiding did not signal a declaration of hostility or war; it was simply an economic alternative to trade. They needed arms and ammunition if they were to face the increasing pressure of Osage raids from the north. At the same time, the contrabandista traders from Louisiana and growing numbers of English traders (who were also arming their Osage enemies) wished to trade with Wichitas, and their presence ensured that an exchange could be had for raided Spanish horses and mules.28

Local Spanish officials tried to comply with the Wichitas’ wishes, seeing in a presidio an answer to their needs as well. In Natchitoches, Mézières repeatedly pressed the advantages of such a plan, arguing that New Spain needed to fulfill the desires “unanimously” expressed by Taovaya, Tawakoni, Kichai, and Iscani leaders. A presidio, moreover, would provide a crucial Spanish base amidst Wichita villages that he hoped to unite into a northern cordon to protect the provinces of New Mexico and Texas from the invasion of “notorious” traders from the English colonies. If Comanches could be won over to the alliance, the cordon would stretch into the mountains of New Mexico. In San Antonio, Ripperdá seconded this call and proposed that Louis de St. Denis be made the commandant of the projected presidio. St. Denis’s standing among Wichita men as well as his extensive knowledge of their languages and of the intricacies of their diplomatic customs was invaluable, because good relations could be “disconcerted at the slightest cause when their mode of intercourse is ignored.” In other words, regional Spanish officials knew that diplomacy would take place on Wichita terms or not at all.29

Yet, the presidio did not materialize, a failure exacerbated by disconnects between Texas and Mexico City bureaucrats that made it even more difficult for local officials to meet military obligations by providing guns and ammunition to their new Norteño allies. Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa angrily asked Governor Ripperdá what assurances he had that Wichitas would not change their “variable moods,” destroy the province of Texas using the arms supplied them, and then proceed south to attack towns like Saltillo and San Luis Potosí. Trade restrictions set by the viceroy drew no distinction between hostile Comanches and the now peaceful Wichita bands. Wichita leaders learned of this mistake when a 1773 military escort of twenty-two soldiers led by Antonio Treviño accompanied a Taovaya party home from a visit to San Antonio de Béxar and passed through the Wichita villages to distribute gifts but were strictly prohibited from giving or exchanging “arms or warlike stores” while doing so. To compound this problem, the viceroy stopped all diplomatic communication between San Antonio and Natchitoches and curtailed all trade between the two provinces, even to the point that traders sent into Texas with trade licenses from the Louisiana government were subject to arrest. Spanish policy in Texas thus gave little indication of unity with their so-called Spanish brothers in Louisiana, much less their Wichita and Caddo brothers closer to home. Officials in Mexico City seemed unable to let go of their earlier awe and dread of the Norteños of San Sabá infamy, worrying even that a Texas governor’s decision to give some Wichitas a passport to Mexico City had enabled them to learn the routes into Coahuila and the state of Spanish defenses all the way to the capital.30

When Spaniards did not act as brothers according to Wichita expectations, Wichita men appealed to kin obligations in Louisiana and reverted to raiding in Texas. Two French traders’ experiences while on a diplomatic expedition to Wichita villages on behalf of the Spanish government highlighted these strategies. Throughout the mission, the agents’ dependence upon Wichitas for escort, hospitality, and safety gave Wichita men repeated opportunities to extract goods from the Spanish representatives at the same time that it pointed up the failure of Spanish trade obligations. During the month it took to escort the two men to Taovaya villages, one of them named Gaignard recorded that principal men and warriors “make me give them booty” and “obliged me to give them each a Limbourg blanket.” Once they arrived, a Taovaya chief called a council, praised Natchitoches officials for sending him a flag to make peace with Spaniards, promised to “love them like the French,” but concluded by saying a “small present for his young men” was necessary. He at once garnered for his warriors eight pounds of powder, sixteen pounds of shot, twenty-four hunting knives, tobacco, and more from Gaignard and the other trader, Nicolas Layssard (Mézières’s nephew). Gaignard sought to emphasize French-Spanish unity, arguing that “it is the same mouth which speaks; it is the same heart and the same blood,” so he urged the leaders to recommend that their warriors not steal more horses and mules from Spaniards in Texas. Almost as though they got the idea from him, Gaignard learned a week later that warriors were about to go on just such a raid. The price for stopping them, explained the head chief, would be a letter written by Gaignard to the governor of Texas asking him to “send presents to stop the warriors.” This time, the Taovaya leader demanded horses, bridles, and sabers for his men. Again, Gaignard responded promptly, though tellingly he sent a messenger not to San Antonio but to Natchitoches to explain the chief’s requirements.31

The costs of French and Spanish “oneness” rose even higher during the following two months, as Wichita men used—to their benefit—evidence of both Texas officials’ aid to enemy Apaches and Louisiana officials’ failure to stop illicit French trade with Osages. First, some warriors insisted Gaignard pay them for the scalp of an Osage enemy if he truly wished to prove Osages were a shared enemy of Wichitas and Frenchmen. Then, when a group of Comanches arrived to report that in a recent fight Apaches had carried Spanish guns, Taovaya leaders argued that only more presents would heal the French betrayal and Spanish lies and “make their hearts content.” Next came contraband traders from the Arkansas River, presenting the Taovaya chief with another opportunity to emphasize to Gaignard the failings of Spanish trade. The headman pointedly explained that these newly arrived traders still accepted horses, mules, and war captives in exchange for the arms and goods needed by Wichitas. That same month, Gaignard’s complaints that his hosts refused to feed or even sell him food indicated that the representatives of the Spanish government no longer merited the ritual obligations of Wichita hospitality. The lengthy visit ended only when Louisiana officials sent more traders with more goods, at which point Gaignard and Layssard made their way—without guide or escort—back to Natchitoches.32

In other situations, principal men from various Wichita bands adeptly manipulated a political language of kinship as well as former diplomatic gifts and prestige objects given them by Spaniards to meet their political and economic needs. Two incidents illustrate how they manipulated such titles and objects with Spaniards and Frenchmen to quite different effect. In 1780, Taovaya chief Qui Te Sain welcomed Louis de Blanc de Villenuefve (St. Denis’s grandson) to his village as a representative of Louisiana governor Bernardo de Gálvez, seeking to expand the trade supplies coming out of that province. Referring to Gálvez as “my father,” Qui Te Sain first directed De Blanc to convey his thanks to the governor for sending his “child” (De Blanc) to him. He wished a reciprocal visit to New Orleans were possible, the Taovaya leader continued, but “the road from your village to mine is too obstructed to enable me to go and taste of your drink and tobacco.” Osage raids required that he remain to defend his people and his village, but he asserted his trust in Gálvez, “offering you my hand, as do all the people of my village.” His trust would not be betrayed, Qui Te Sain was sure; Gálvez would aid them with supplies and a blacksmith, which they needed because they had “neither hatchets, nor picks, nor rifles, nor powder, nor bullets with which to defend ourselves from our enemies.”33

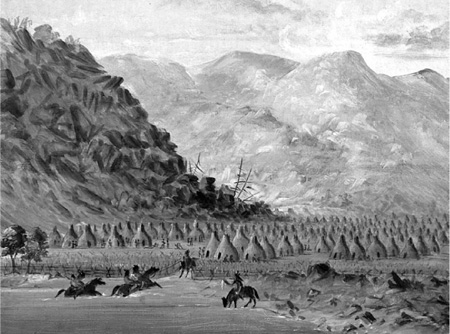

Village of the Pawnee Picts [Wichitas], by George Catlin, 1834–35. Courtesy of the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Quite a different tone was struck when disputes erupted between Spaniards in Texas and Frenchmen in Louisiana over trading privileges with the Wichitas, and Wichita leaders used diplomatic language and objects masterfully to play the two provinces’ traders against one another. In one instance, Wichita leaders confronted Spaniard Antonio Gil Ibarvo over the higher prices and woeful stores he offered them in comparison with Frenchmen in Natchitoches by “destroying at every step my flags, staff of command, and medals, saying that they cannot live on the luster of these,” Ibarvo recorded. Two years later, another conflict began when Ibarvo tried to extend his trading jurisdiction from Kichai villages on the Trinity River to those along the Red River near the Kadohadachos by declaring that Frenchmen from Natchitoches were unlicensed to trade there. Kichai men simply refused to recognize Spanish dictates about trading partners and challenged Ibarvo directly when he traveled to their village to demand explanation for their continued trade with Louis de Blanc Villenuefve and his cousin Bouet Laffitte (also of the St. Denis family). They explained that the two Frenchmen gave them ten musket balls for each deerskin, as opposed to the five offered by Ibarvo. In a tidy twist—unknown to Ibarvo—Kadohadacho chief Tinhioüen had used the vying trade to make French officials at Natchitoches adhere to the same price of ten balls and ten shots of powder for their hides just two months before.34

Kichai men had far more to say in response to Ibarvo’s attempt to undercut them. To communicate why “they had always traded with the French” and “would always trade with them, even a small child, and not with the people of Nacogdoches,” Chief Nicotaouenanan devoted some time explaining to Ibarvo the kin relations between French and Kichai men that underlay his village’s economic ties to De Blanc and Laffitte. He first asserted that the two men always opened their homes to Kichais, where they were treated and fed well, and that they had maintained the trade even during times of scarcity. They thus met the obligations of generosity required of any respected kinsman. Most important, the Kichai leader continued, the “real chief for them was the chief with the big leg [De Blanc’s grandfather, Louis Juchereau de St. Denis] . . . who had first opened the trails in all their nations . . . who had provided all manner of help to them,” and though he had died, “he had left one of his descendants, and that it was him whom they regarded as their chief and that they would similarly look upon all his descendants, as long as there would be some.” How could Ibarvo or any Spaniards compete with kin ties so close that they reached down through a family lineage to maintain the standing of each generation of St. Denis men within Wichita ranks? To express the finality of their rejection of Spaniards, Nicotaouenanan called for an end to all ritual hospitality, declaring that Ibarvo “must never come to their house, as they wouldn’t go to his house either,” and taking the Spanish medal hanging around his neck, hurled it away from him.35

Meanwhile, Wichita men used raids to rein in their defaulting Spanish allies in San Antonio. Raiding that began in the winter of 1783 brought Spaniards back to the negotiating table by the summer of 1784. The first hints of trouble came in the winter of 1783–84 when, despite a blistering snowstorm, horses tied to their owners’ doors throughout San Antonio vanished. Pursuers tracked them through the snow with no success. The following spring, Spaniards from San Antonio rounding up wild cattle out by the Guadalupe River suddenly found themselves challenged by young warriors. They fled in fear, returning later to find many of the beeves slaughtered and eaten. The next month, the governor’s own household was struck. Warriors broke through a neighboring building, found access to the stables of the governor’s residence, took his two best horses along with two servants’ horses, and made their way out through the governor’s garden, where they wreaked havoc in the beds of melons, squash, and corn. In pursuit of this last raiding party, Spanish soldiers finally learned the culprits’ identity—not because they overtook them, but because an escaped captive, a Spanish youth from New Mexico named Francisco Xavier Chaves, turned up with an account of the recent events.36

It turned out that, with little reason to respect their leaders’ claims of Spanish alliance when Spaniards themselves ignored them, young Taovaya and Wichita warriors had spent the year in and about the San Antonio region on a coup-gathering venture. In May, the young men had broken off from a larger campaign of allied Wichita warriors seeking revenge for recent attacks by Lipan Apaches to look for their own raiding targets. Thus, while senior Wichita warriors met with presidial commander Luis Cazorla at the Bahía presidio to explain that the aim of their party was a fight with Apaches, not Spaniards—as a diplomatic courtesy in exchange for his hospitality—the younger men defiantly went off to prove otherwise. And impressive coups they indeed earned—taking horses from the midst of a sleeping settlement, especially horses of a man of rank like the governor, at the risk of death if they were caught.37

Brought together again by the raids of the young Wichita men, Spanish and Taovaya leaders pursued new means to reassert a truce through diplomatic rituals of mutual respect. The governor of Texas, Domingo Cabello, turned to a Frenchman to make his overtures for him. He sent Jean Baptiste Bousquet, a trader who had once lived in a Taovaya village, to pay special respect to Taovaya leaders Gransot and Quiscat. Along the way, though, he was also to carry goodwill messages from the governor to leaders at Iscani, Flechazo, and Tawakoni villages. Upon arrival at the Taovaya settlements, Bousquet discovered that Chief Gransot had recently died and the Taovayas had chosen a leading man named Guersec as his successor. The turnover in leadership offered both Taovayas and Spaniards a serendipitous opening to mend their breach through the political ceremonies surrounding Guersec’s succession. After pledging to redirect his young men’s military energies to maintaining an active war against enemies whom Wichitas now shared with Spaniards, Guersec ordered four of his men to accompany Bousquet to San Antonio to renew relations with the Texas government through the formalities attendant on Spanish recognition of Guersec’s new rank. Notably, Guersec did not go in person to meet with Cabello but delegated that duty to other, lesser, men.

From a Spanish perspective, the investiture of Guersec was a perfect opportunity to extend Spanish hospitality to Wichita leaders for the first time in a long while, and Bousquet readily grabbed at the chance to escort Guersec’s chosen emissaries to San Antonio. The formal recognition of Guersec’s succession further provided Governor Cabello the means by which to send the Taovaya leader diplomatic honors and gifts without seeming to relent about the recent raids. Ultimately, from the coups of their young warriors, the Taovayas extracted a “captain’s uniform” and other “gear appropriate for [a chief]” for Guersec, a horse and gifts for each of the men in the Taovaya delegation sent to San Antonio, and annual gifts for the “body of the nation.” Having pronounced Guersec “a person who had all the good qualifications of valor and affection for the Spaniards,” Cabello also sent him gifts and an official confirmation stating his standing in Spanish eyes as “chief and governor of the nations of the Taboayazes to the end that he may lead and govern them in time of peace as well as in war” and asking that he “assemble his people to go out on campaigns against those who may be enemies of His Majesty.” Again, military commitments defined the relationship between Spaniards and Taovayas.38

Only a month later, a Spanish military detachment escorting forty-nine representatives from Taovaya, Tawakoni, Iscani, and other Wichita bands homeward from San Antonio after a diplomatic visit had the chance to confirm in blood that military relationship when they discovered tracks of Comanche warriors along the way. The officer in charge, alférez (sublieutenant) Marcelo Valdés, quickly grasped the possibilities of diplomatic gain if they were to “apply all possible means to succeed in overtaking the enemy so that the Friendly Indians could see how the Spaniards could do their duty.” After the Spanish and Wichita group found the Comanches and killed eight of the ten warriors, while losing only one soldier, the Wichita delegates declared themselves convinced that the “Spaniards were most valiant and very much their friends, since one of them had died defending them.” In a final show of honor, Valdés turned over to the Wichita observers all the trophies taken, including five horses and “all the chimales [round leather shields], spears, arrows, and scalps that belonged to the enemy.”39

In turn, Spanish officers interpreted as reciprocal honor the Wichita men’s expressions of grief and mourning over Corporal Juan Casanova, who lost his life in the battle. At the battle site, Wichita warriors demonstrated “such sorrow,” governor Cabello later wrote, “that it would have seemed the dead man was their own chief.” Wichita leaders promptly dismissed the soldiers from their obligation to escort them farther in order that they could hurry home with the fallen man “so that his wife . . . might mourn him.” In a further gesture greatly impressing Spanish officials and civilians alike, one of the Wichita chiefs sent a warrior to attend Casanova’s funeral in San Antonio, where in mourning on behalf of Wichitas, he cut his hair, as he would have for his own brother, and reputedly wept more than the soldier’s own relatives.40

Newly committed Wichita and Spanish allies now decided that if their brotherhood was to succeed, they had to turn Comanches from competitors into kin as well. Wichita negotiations with Spaniards had caused friction with their former allies and trading partners, and they wanted their Comanche brothers back. The Spaniards, as always, hoped simply for peace. As Caddo leaders had helped Spaniards achieve an accord with Wichitas, now Wichita men would take the lead as male mediators whose own past relations of honor with Comanches might get Spaniards safely into Comanchería under their escort. Spanish efforts to reestablish standing among Wichitas had also gained them new interpreters to aid in this new endeavor. Two Frenchmen and one Spaniard who had been living among Taovayas went to San Antonio with the Wichita party to celebrate Guersec’s inauguration. By the spring of 1785, Spanish officials had pardoned the three men—Alfonso Rey, Pedro Vial, and José Mariano Valdés—for their unlicensed residence among Indians. They then agreed to live at San Antonio de Béxar and commit their skills as, respectively, blacksmith, medical practitioner, and interpreter to the community and presidio. The serendipitous arrival in San Antonio of Francisco Xavier Chaves (the escaped captive who identified the Wichita youths as the authors of San Antonio’s mysterious horse thefts) also proved valuable to Spanish officials. Chaves had been captured near Albuquerque, New Mexico, as a young boy, had been adopted by a Comanche mother to replace a son she had lost, and then had been sold to the Taovayas years later, after her death severed his Comanche connection. In the summer of 1784, he had accompanied the young Taovaya warriors on their raiding coups but then escaped to present himself at the San Antonio de Béxar presidio. Although he had spent much of his youth among Taovayas, he still retained enough knowledge of Comanche language and culture to aid Cabello. Taovaya chiefs Guersec and Eschas would now try to get Vial and Chaves a hearing with Comanche leaders so they could plead a case for Spanish diplomacy.41

The daunting question, however, remained whether or not Comanche leaders had reason to respond to joint Taovaya-Spanish overtures. For the preceding fifteen years, they had watched as their former Wichita allies had drawn closer to Spaniards in Texas without gaining much in exchange. Eastern bands of Comanches who had traded horses, mules, and captives to Wichitas in exchange for their agricultural products and French armaments had equally reliable trading partners in Pawnees on the Northern Plains and in western Comanche peoples who alternately traded with or raided Spanish and Pueblo communities in northern New Mexico. With so many economic options, Comanches had no need to pursue peace and trade instead of war and raids in Texas. As long as horses and mules gained in raids supplemented their growing pastoral herds and markets remained for the products of their bison hunting, they had little inclination to accommodate San Antonio officials desperate for conciliation.

In the 1780s, however, environmental and demographic upheavals tempered Comanche viewpoints. A severe drought across the Southwest in the late 1770s hindered agricultural production in many of the communities on which western Comanches relied for subsistence products and reduced grazing lands upon which the bison they hunted and the horses they raised depended. At the same time, both western and eastern Comanche bands suffered their first devastating smallpox outbreaks in a series of epidemics between 1778 and 1781 that ravaged Spanish and Indian settlements across Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, and the Southern Plains. Demographic losses compounded a period of limited trade resources to give Comanches a new sense of vulnerability. For the first time, they confronted increasing dependence on factors and people beyond their own control. To ensure their continued socioeconomic strength, they sought new commercial and political opportunities in both Texas and New Mexico.42

There were peaceful moments between Spanish and Comanche peoples in Texas between 1769 and 1785, but those moments had been fleeting and always framed by a violent context from which Spaniards seemed incapable, and Comanches unwilling, to extricate themselves. The negotiations that had first brought Wichita leaders to San Antonio de Béxar in 1772 had also marked the first peaceful visit by a Comanche leader, principal chief Evea, who accompanied Wichita allies to the Spanish settlement with five hundred of his own people. But intervening Comanche raids on Spanish horse herds and Spanish deportation of captive Comanche women had derailed all possibility of a truce (as will be seen in Chapter 6). At that point, neither Comanche leading men nor Spanish officials could separate their politics from warfare.43

When the French trader J. Gaignard had visited Taovaya settlements along the Red River in October 1773, Comanches periodically met him there as well and expressed pleasure at seeing him. Yet, like the Wichitas, they stressed that their friendliness rested in his identity as a Frenchman and that “they would listen to the word of the French.” Gaignard eventually met with Evea himself but primarily took away from the meeting a sense of awe at the display of Comanche power. The number of people who came in Evea’s party so impressed the Frenchman that he thought that the Comanche leader had brought with him “the whole nation.” Gaignard did try to stress French-Spanish unity and, in supplication to the Comanche leader, asked Evea to “forbid the young men to make war on the Spaniards,” now that Spaniards and French “are one.” To “open Comanche ears and hearts to peace,” Gaignard presented Evea with a Spanish flag to signal amity, a blanket to cover the blood spilt between them, knives to straighten the crooked trail of their relations, and tobacco to be smoked by the young men “so that war may be at an end.” “Charmed” to have the flag, Evea proclaimed his intention “to place it over his cabin, that all the Naytanes [Comanches] might see it.” Nevertheless, peaceful encounters would be few and far between as long as raids gained Comanches far more than trade ever would. Even the viceroy at one point had to admit his admiration for warriors who could raid the presidial herds at San Antonio de Béxar “so adroitly that to their satisfaction and pleasure, they were able to choose the best horses for themselves.”44

Another passing moment of diplomatic opportunity to appeal to Comanche bonds of camaraderie and “brotherhood” had come in 1778, but Spanish bungling instead pushed Spanish-Comanche détente from raids to war. Decisions by the 1777–78 junta de guerras finally enabled plans for a joint Norteño-Spanish campaign against Apaches. Spaniards hoped not only to mollify estranged Wichita leaders but also to persuade Comanches that an alliance with Spaniards would be more profitable than enmity. With Comanches the clear “masters of the region” and Wichitas the “master-key of the north,” Texas officials well knew that the welfare of the province would rise or fall upon their “alliance, companionship, aid, knowledge, and intrepidity.”45

A military campaign would allow Spaniards to attain the respect and allegiance of Comanches, who “excel all the other nations in breeding, strength, valor, and gallantry.” In effect, Spaniards had to prove their valor and honor to these indomitable warriors if they were to enjoy their alliance. “Whenever they [Comanche men] go to the aid of any warlike tribe,” Mézières had explained in 1777, male comrades “are given the name Techan, similar in meaning to comilito of the Romans, and comrade in our language, and there results at once among those who use it a sort of kinship, a very firm union of interests, a complete sharing of common injuries, and a deep-seated opinion that the violator of so sacred a pact will receive the punishment which the supreme being has ready for liars.” To approach such Comanche men, Mézières had called upon the aid of a young Comanche warrior who had been wounded in battle and captured, and whom both Ripperdá and Mézières had come to “look upon more as a son.” They sent the young man home carrying Spanish diplomatic overtures to Comanche leaders.46

Subsequent events, however, went so horribly awry that the Comanches ended up with only a need to exact vengeance in exchange for Spanish dishonor. In response to the Natchitoches official’s invitation to meet, a party of Comanche warriors led by chief Evea’s son had traveled to the new Spanish town of Bucareli in search of Mézières after not finding him at the Taovaya villages (where his message had told them to expect him). They camped outside town and released their horses to graze. They had not yet approached the settlement or discovered that Mézières had departed that very day, when Bucareli citizens attacked them. The Spaniards killed several warriors and forced the rest to withdraw. In his subsequent denunciation of the townspeople, Mézières decried their knee-jerk hostility, arguing that the Comanche men’s actions—turning their horses loose and sitting down to rest—“did not give them the appearance of enemies.” All the Spanish settlers had seen, though, was a party of Comanche men, and as Mézières angrily recorded, “without first asking the important questions of who they were, what they were seeking, and where they were going . . . by which conference and calmness it is probable that a disastrous attack would have been averted and our moderation and prudence established—they opened fire, killed several Indians, wounded others, put the rest to flight, and despoiled them of their horses.” The Spanish men’s violence brought the wrath of Comanche warriors down upon the province for the next seven years.47

Raids and counterattacks intensified in concert as Comanche war parties avenged the sullied honor of their fallen comrades. They first focused their ire on Bucareli itself, in October 1778 taking 240 horses in a raid meant to lure pursuers into an ambush precisely where the Spaniards had attacked Evea’s son. Another raid netted 202 horses. One family fled with such speed they left a fire burning in a fireplace that burnt down their house, spread to surrounding structures, and razed half the settlement. It didn’t matter, because everyone had left for the safety and sanctuary of neighboring Caddo and Wichita villages. All too soon, Comanche targets expanded to the San Antonio area, where for a time Spaniards and Comanche men seemed locked in a violent one-upmanship that would allow no other rivals.48

Warriors and soldiers alike seemed to view their struggles as referendums on their national and individual honor. Comanches lost no opportunity to flaunt their dominance over Spaniards. After a battle that pitched a small, poorly armed presidial force against Comanches with superior numbers and weapons, warriors wearing the coats of killed soldiers rode by San Antonio to alert the fort of their fallen comrades. Upon arrival at the battle site, Spaniards found six men set around a tree, all scalped and some missing noses and fingers, with sticks propped in their eyes to keep them open—open to their unmanning? Spanish victories, on the other hand, were far fewer, and commanders often bemoaned the difficulty of dividing up the belongings of one or two fallen Comanches into trophies for more than seventy soldiers. Thus, imagine their delight when an assembled force of Spanish soldiers, citizens, and mission residents surprised a group of Comanche warriors near the Guadalupe River and killed nine or ten Comanche men, counting as their coup a gun, three spears, eight many-feathered headdresses, several bows, quivers, and arrows, an English ax, and most notably a feathered halberd taken from a chief. Tellingly, when Apache warriors traveled to San Antonio hoping to buy some of these trophies, Governor Cabello flatly refused, telling them to overcome cowardice and achieve their own victories if they wished trophies of Comanches. In this way, Cabello used trophies taken from a feared foe to castigate Apaches as failed allies as compared with their “valiant” Comanche enemies, while also bolstering Spanish valor for having, at least momentarily, won a victory over that enemy. Neither Spanish nor Comanche valor was for trade or purchase in that high-stakes warfare.49

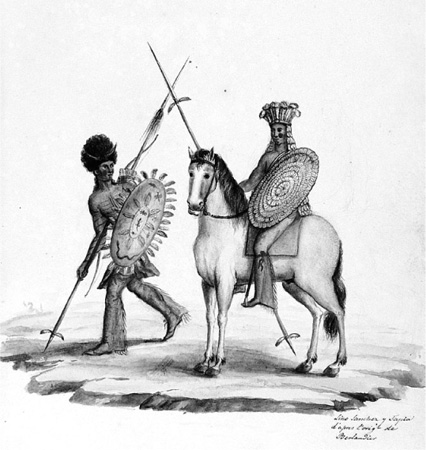

Comanches of western Texas “dressed as when they are going to war.” One wears a feathered head-dress and the other a buffalo-hide cap; their faces are painted red and their chests and arms with black stripes; and they are armed with long-shafted lances with sharp metal heads, a bow and a quiver of arrows, and shields, one feathered and the other painted rawhide. Watercolor by Lino Sánchez y Tapia after the original sketch by Jean Louis Berlandier, a French botanist who traveled through Texas as a member of a Mexican boundary and scientific expedition in the years 1828–31. Courtesy of the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Another exchange in 1780 crystallized the high costs of the dueling Spanish-Comanche animosity at both provincial and individual levels. That year, Governor Cabello presented Comanche men with an irresistible opportunity for both profit and coup: a herd of two thousand cattle to be sent from Texas to Louisiana to supply Spanish forces fighting in the American Revolution. Setting up encampments in the woods between the Guadalupe and Colorado Rivers—an area so rough and impenetrable to all but Comanches that it was called the “Monte del Diábolo” (Devil’s Mountain)—Comanche men established a semipermanent base from which to launch raids on both ranches and any supply trains daring the roads throughout the San Antonio region. As the raids mounted, so too did the humiliations, especially as each strike ended when retaliatory Spanish parties, one after another, pulled up short at the Guadalupe without the strength or courage to cross into a zone of Comanche control. At the sight of Comanche warriors, one unit abandoned horses and arms in their rush to flee—a disgrace that led Cabello to indict the leading officer on formal charges for “cowardice.” Another presidial commander, Marcelo Valdés, tried to persuade one group of ninety-one soldiers, settlers, and mission Indians to continue by promising to find a small enough group of Comanche men to beat in order to salve Spanish pride. He actually sent a patrol up and down the Guadalupe looking for likely opponents. The plan failed miserably, though, when word arrived that, while they had been patrolling, Comanches had routed the first one thousand head of cattle Cabello had purchased from multiple mission ranches. In the wake of such devastation, no one in San Antonio would risk the loss of more cattle or endanger their own personal safety while driving them. Thanks to the Comanches’ power—and their imperative to avenge warriors’ deaths—the American Revolution would proceed without Spanish aid from Texas.50