Chapter Six

Womanly “Captivation”: Political Economies of Hostage Taking and Hospitality

Throughout Spanish efforts to make peace with Apaches, Wichitas, and Comanches in the 1770s and 1780s, male rituals may have dominated diplomatic language and ceremony, but the material terms of negotiation more often than not revolved around women. In varying diplomatic strategies, women were sometimes pawns, sometimes agents. Just as Apache, Wichita, and Comanche political customs reflected the more martial air of former enemies seeking to become new allies, so too did women initially enter these exchanges by coercive and violent routes. Women’s more active participation in intermarriage and hospitality rituals later reemerged in critical ways in different native groups’ “practices of peace.”

In their diplomacy with Spaniards, Comanche and Wichita men first turned to already established exchange networks of captive women that had developed out of their economic alliances with the French. Among Wichitas, Comanches, and Spaniards, however, such networks would be framed not as market exchanges but as hostage exchanges within the politics of postbattle reparations. Because the political use of captives had been a continuous thread running throughout Spanish negotiations with Lipan Apaches previously, that experience shaped the ways in which Spaniards responded to peace agreements initiated with Wichitas and Comanches. Captive exchange then developed directly out of past warfare. Women’s appearance within subsequent diplomacy highlights the periodic attempts of Spanish, Wichita, and Comanche men to transform transient truces into permanent peace.

Beginning in the 1760s, Wichita (and later Comanche) men searched for ways by which Texas Spaniards might replace Frenchmen as trading partners when Spanish authorities cut off licensed exchange networks into Louisiana in 1769. An essential ingredient of those networks had been female captives whom they had taken in war with native enemies and then traded for French arms and goods. Although Spanish horses, bison hides, deerskins, and bear fat had moved along French exchange networks to New Orleans and France, women tended to travel no farther than the households of European men living in Natchitoches and other western posts who desired domestic servants or sexual, and sometimes marital, partners. The continuing intimate and familial desires of European traders and hunters living in the hinterlands of Louisiana fueled a contraband version of that trade after 1769. But to supplement that market exchange, Comanche and Wichita men turned the Spanish trade prohibitions on their head, putting female captives to a new economic use by seeking profits from Spanish officials in Texas through what Spaniards preferred to call “ransom” or “redemption” payments.

That new form of exchange may have served native material needs, but from a Spanish perspective it could also be purely diplomatic. Unlike Spaniards’ earlier hostilities with Apaches—when they sent their own forces to take Apache women and children captive—Spanish officials now sought to acquire captive Indian women through ransoming, with the purpose of using them as lures with which to draw the women’s kin into political negotiation. Indeed, Spaniards could make diplomatic overtures to both the women’s captors and the women’s families. Notably, Spanish forces never risked the enmity of Wichita men with raids bent on capturing Wichita women. Because hostilities continued through the 1780s with Comanches, some Comanche women did fall prey to Spanish capture, although the military power of Comanche bands ensured that the much smaller and weaker presidial forces of Texas Spaniards managed to take only a very few.

The female sex of the majority of captives subject to such political exchanges still tapped into an association of women with peace. In the traffic itself, female captives became the bargaining chips by which male captors negotiated truce and alliance. As with the Apaches at midcentury, women also emerged as mediators, able to move back and forth between their own people and Spaniards when men from either group could not safely or successfully do so. Hence, the exchange of women—despite its violent and coercive origins—became a critical component in efforts to effect peace in the latter half of the century.

Spanish involvement in native systems of captive taking and exchange did not secure the peace with Wichitas in the 1760s and 1770s, but it did offer limited economic exchange when the Spanish viceroyalty dragged its bureaucratic feet in establishing the commercial trade demanded by Wichita alliances. Wichitas often found that it was captive Spanish women from New Mexico (whom they acquired through trade with, or raids on, the women’s original native captors) who best garnered Spanish attention and Spanish ransom payments. Furthermore, redeeming captive Spanish women repeatedly smoothed over conflicts when the horse raiding of young Wichita men made peace a tricky proposition through the 1780s. Some of these women, though, appear to have remained to live among the Wichitas or in the nearby Spanish villa of Nacogdoches. As ties among Caddo, Wichita, Spanish, and French peoples increased at the local level in mixed neighborhoods and settlements in eastern Texas, the responsibilities of Caddo and Wichita women within their societies’ systems of hospitality found new or renewed political currency in their diplomacy with Spaniards.

Meanwhile, Lipan Apaches, who had been shunted aside by Spanish officials seeking relations with their Norteño enemies, pursued a twofold strategy. They first tried to establish trade alliances with Caddoan and Tonkawan peoples to the east and then turned their attention to eliciting some limited form of defensive alliance with local Spaniards in San Antonio and La Bahía by settling their families nearby. Women stood at the center of both strategies. As the means to make amends for their former hostility, Lipan Apache leaders offered to return many of the captive women taken during earlier raids against Caddos and the loosely allied bands of Tonkawas, Bidais, Mayeyes, Akokisas, and Cocos living south and southwest of the Hasinais. Then Apaches forged new trade and military ties by uniting their own families with those of the Caddo and Tonkawa confederations through intermarriage.

Comanche women came to the political fore in Texas in the wake of the Spanish-Comanche peace treaty of 1785, playing powerful roles in the “practices of peace” by which Comanche men communicated and maintained ties of brotherhood with their new Spanish allies. The restoration or sale of female Indian captives periodically occurred in Comanche-Spanish exchanges as well (for both political and economic purposes), yet it was the presence of Comanche women in their bands’ diplomatic and trade parties to San Antonio that truly served as the barometer of Comanche relations of peace. The presence or absence of women indicated Comanche leaders’ estimation of their Spanish “brothers” at the time of meeting. Spaniards soon learned to reward the female members of delegations with gifts and services, recognizing their presence for what it was: signs of rapprochement.

The Spaniards’ ability to navigate these different diplomatic customs and strategies varied with individual Spanish leaders and with the financial and administrative support of their viceregal superiors. Spanish mistakes could be read as insults by native leaders who, of course, continued to hold the balance of power. Indeed, the Spaniards’ need for alliance with these bands—whether Caddos, Apaches, or Wichitas, whose economic strength waxed and waned, or Comanches, whose dominance had not yet even reached its peak—reflected their weak position in the region relative to their Indian peers. Such power differentials, in turn, demanded careful Spanish attention to native custom. Repeatedly, officials at all levels of government within Texas and the Interior Provinces directed that amity with Comanches, Wichitas, Apaches, and the “Friendly Nations” be secured at all cost. The native terms by which friendship would be maintained put women squarely at the heart of Spanish-Indian peace practices.

Unlike their Apache foes at midcentury, Wichita men were not seeking the return of their own wives, daughters, sisters, and mothers when in the 1760s and 1770s they first approached Spaniards in Texas with offers of female captive exchange. Such exchange tended to be more an economic and political rather than personal negotiation for Wichita leaders because Wichita women were not at risk of Spanish capture. Instead, Wichitas held captive women primarily from raids and skirmishes with native enemies or purchased them through trade with Comanches. Unlike their Comanche allies, Wichitas do not appear to have married many captive women or adopted many captive children, particularly Spanish captives, into their families. They even distinguished captives from Wichita women with body decoration. The extensive tattooing on women’s faces, necks, chests, and breasts varied only slightly among Wichita women living in the same community, indicating band as opposed to individual identification—differentiating them both from other native peoples and from the captives held in their settlements. Wichita captive trade first developed in response to French demand and continued in the 1770s and 1780s because of Spaniards’ lucrative “redemption payments.” The former garnered trade alliances with Caddos and Frenchmen, and the latter facilitated a new form of alliance with Spaniards. Because Wichita men neither formed marital unions with their captives nor brokered unions between their own women and the European men to whom they traded the captives, Wichita exchanges of women remained entirely outside the bonds of kinship. Nevertheless, they used both exchange systems to preserve the material and defensive security of their families and the extended kin networks that tied Wichita bands together.1

That new political value first became attached to captive Indian women back when Wichita-Spanish peace processes opened in the 1760s. Taking lessons learned in French markets about European desires for enslaved women, Wichita diplomatic overtures were made to Spaniards in the form of captive women. As a means of furthering talks following fray José de Calahorra’s visit to the Tawakoni-Iscani villages in 1760, Tawakoni warriors captured three Spanish women from Apaches who had originally taken them hostage in New Mexico. Tawakoni leaders traveled to the Nacogdoches mission to report their deed and in so doing emphasized that they had rescued the women “for this purpose” and “for this end.” During Calahorra’s next visit, Spaniards presented flags, armaments, and silver-mounted staffs of command to Tawakoni chief El Flechado en la Cara and Iscani chief Llaso in return for custody of the three captive women. Still more presents and goods then flowed into the stores of the two headmen after the exchange. By 1763, Calahorra’s negotiation with Tawakonis and Iscanis ultimately netted the Spaniards a total of eleven or twelve ransomed captives, including a Christian Apache woman named Ysabel (all originally taken by Pelone Apaches). Two years later, even the much-heralded return of Lieutenant Antonio Treviño came with accompanying offers from Taovaya chief Eyasiquiche of far more female captives than the lone man.2

Building on these early gestures, the Taovayas’ return of two Spanish women became just as important as the return of Parrilla’s two cannons in 1770 when peace negotiations finally began in earnest (see Chapter 5). The 1770 overture was a rare case in which adoption and kinship complicated the political process. Natchitoches commander Athanase de Mézières reported that the two women had lived so long among Taovayas that they had married and borne children and thus were no longer “slaves” but “free.” More important, despite the Taovaya leaders’ offer, Mézières knew the men conditioned the return on the women’s consent and doubted that they or their Wichita husbands would agree to tear apart their families. Not surprisingly, the following year, when the chief visited Tinhioüen’s village again to leave a message regarding his wish for harmony with Spaniards, he did not bring the women. Rather, he left two “hostages,” most likely Taovaya boys or young men, “in pledge of his promise,” who would remain there until he returned from meeting with Mézières. In the final peace agreement, the return of Christian captives living in Wichita villages held equal place with stipulations of a cease-fire, restoration of Parrilla’s cannons, military alliance, and diplomatic protocols, yet no record indicates that the women ever left the Taovaya villages.3

The story of one Wichita woman’s redemption illustrates the power of native custom in Spanish-Indian diplomacy, Spanish need and desire to conform to Indian expectations, and the central importance women played in paving the way for peaceful relations. When several principal men from Kichai, Iscani, Tawakoni, and Taovaya bands journeyed to San Antonio to ratify the peace with Governor Juan María de Ripperdá in 1772, a principal Taovaya chief told Ripperdá that he had received word that his wife, who had been captured by Apaches a few months before, had been sold by her captors to a Spaniard in Coahuila. He saw in the Spaniards’ desire for the Wichitas’ alliance a new opportunity to regain his wife in circumstances where he himself could not, and he asked what the governor could do to effect her return. “She is so much esteemed by him,” Ripperdá reported to the viceroy, “that he assures me that she is the only one he has ever had, or wishes to have until he dies, and, as she leaves him two little orphans, he begs for her as zealously as he considers her deliverance difficult.”4

Ripperdá quickly realized how critical it would be for him to rescue the Taovaya woman, for if he did not, “all that we have attained and which is of so much importance would be lost.” In other words, the success of the newly completed peace would rest upon the captive woman’s return. A month later, Ripperdá could only exult in his good fortune in another letter to the viceroy, because “having very urgently requested from the governor of Coahuila the wife of the principal chief of the Tauayas [Taovayas], whom the Apaches captured and sold to the Spaniards of that province,” she had been brought to San Antonio with a convoy of maize and was even then a guest in Ripperdá’s home. He had had to buy her from a Spanish dealer, since she had already fallen prey to Spanish enslavement. More to the point, he reiterated “that she may be the key that shall open the way to our treaties.”5

Ripperdá played host to the Taovaya woman for six months following her rescue, waiting for news of her release to travel via Natchitoches to the Taovaya villages. In February 1773, her husband finally arrived with eight warriors and a French trader to act as interpreter, and at last Ripperdá could write to the viceroy of the successful conclusion to the captive redemption. In March, the governor sent word that the happy husband as well as the entire Taovaya delegation was staying in Ripperdá’s home and wished authorization to continue on to visit the viceroy, presumably in thanks for the woman’s emancipation.6

At about the same time, Governor Ripperdá also resorted to more coercive measures in using captive women in negotiations with Comanches. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he bungled it badly. The governor initiated contact in 1772. In February, a detachment from the Béxar presidio returned to San Antonio with unheralded prizes: four Comanches, three women and one girl. Ripperdá already had three other Comanche women in his control who had been captured months before and who had been held so long in one of the San Antonio missions that all three had been baptized and two married off to mission Indian residents. As shortly became clear, however, these women desperately wanted to escape back to their own families. Because of their baptisms, the Spaniards would not return them to live in apostasy, but the governor decided that the four new captives could be put to diplomatic use. Since the Spanish government had recently completed new peace agreements with both Wichita and Caddo bands, he hoped for the first time to attract (or blackmail) Comanches to the negotiating table as well. With that intention, Ripperdá sent two of the women, under military escort, back to their village with political gifts to present to their chief, Evea. Meanwhile, he kept the other woman and the little girl as hostages.7

In response, seven Comanche warriors rode into San Antonio a month later, led by a woman carrying a cross and a white flag meant to secure their safe entrance into the Spanish town. Chief Evea and his leading men well knew that they had to put a woman at the head of that delegation. Hostilities had been the rule for too long for Spaniards to see a Comanche party composed only of men as boding anything but a fight. The woman leading the party was one of the female captives freed by Ripperdá and also the mother of the little girl still held hostage. Whatever Evea’s wishes or intent, she came for her daughter. Others in the party included the hostage girl’s father, the husband of the other hostage woman, and the brother of two of the three baptized Comanche women held in the missions. All together, everyone had a personal—kin—stake in this meeting.8

The group reunited with the two recent hostages, received more diplomatic gifts from Ripperdá, and upon departure, took their own form of ransom payment by making off with four hundred horses from the Béxar presidio herds. They also tried to liberate the three baptized Comanche women—together with their willing husbands, who apparently preferred a life among Comanches to whatever the mission had to offer. Spanish soldiers, however, stopped their escape. That one recaptured woman then tried to kill herself provides a painful glimpse at the level of despair and desperation faced by captives. The Comanche rescue party was itself not home free once it got away from the Spanish town. Apache warriors attacked them as they fled, killed seven men, captured half of the horses, three of the women and the little girl, and turned them back over to the Spaniards (probably for a ransom). The stalwart Comanche woman who had led the expedition managed to escape her Apache captors, but in her flight fell into the hands of still more Indian warriors from one of the San Antonio mission communities. They too returned her to Ripperdá’s control. Spanish officials, angered at what they labeled Comanche “treachery” for using women to feign peace (with the cross and white flag), sent all the women to different forms of enslavement in Coahuila. Though Ripperdá briefly tried to persuade Viceroy Bucareli y Ursúa to consider “sending the women back to their people”—even the missionized ones, because of “how little faith they profess”—the viceroy categorically refused. Thus, the two married Comanche women from the mission were destined for Coahuila missions accompanied by their husbands, while the single woman and the mother and daughter suffered more punitive fates, most likely servitude or labor camps, at the hands of the governor of Coahuila.9

At first this story suggests Spanish power (at least to exact revenge), but the governor’s rash actions caused far more problems for the relatively weak Spaniards. Comanche leaders were not yet done with Ripperdá, nor were they about to give up the fight for their female relatives. That summer, a number of them traveled to San Antonio in the company of allied Wichita chiefs to retrieve the women now in Coahuila. Chief Evea himself joined the conference. Ripperdá initially attempted to shame the Comanche men by displaying the “false” white flag of truce carried earlier by the Comanche woman. His efforts fell on deaf ears. Though he claimed to the viceroy to have sent the men away empty-handed, Ripperdá found himself upstaged by the husband of one woman, who had come well prepared to wait out the governor in protest of his wife’s enslavement. Either the warrior made quite an impression upon the besieged Ripperdá or the governor never had any intention of turning the formidable Comanche men away, because in the same letter where he bragged of cowing Evea with the “false” flag, he reported that he had advised the governor of Coahuila to ensure that the Comanche woman was not baptized, so that indeed she could be returned to her husband. The viceroy agreed with his decision, arguing that the “volubility” of the Comanche men over their women was proof that they would persevere until they got them back. Records fail to confirm whether she was indeed set free and returned to her family, but her redemption, if it even came, was certainly not sufficient to ease the Comanches’ hostility and need to avenge the others who were lost.10

When Spanish officials acquired Comanche women to coerce peace with their bands, they were trying to forge an alliance through an act of hostility. Spanish captive diplomacy may have also resonated, negatively, with social controls internal to Comanche societies. Indeed, to these men, Spanish policies targeting their wives or female family members may have most resembled practices of “wife stealing,” which were governed by codes of male competition. Though sometimes representing a woman’s effort to escape an unwanted marriage, wife stealing put male honor to the test, and so competition for male rank within Comanche communities sometimes involved taking wives from husbands. A loss of reputation, influence, and privileges might follow, as others assumed a lack of ability on the victim’s part that his male rivals, particularly the man who stole his wife, possessed. Moreover, in bride-service societies like those of the Comanches, nothing affected a man’s social and political rank as much as the loss of a wife. Without her, a man also lost home, shelter, and the provision of services that allowed him to offer other men hospitality. A man had to take action in response or suffer disgrace. If wives could not be regained, warriors demanded compensation through damage payments in goods, horses, clothing, and guns. The importance of such an exchange lay not in the actual value of the articles but in the maintenance of honor. If indeed Comanche men interpreted Spanish actions within the terms of their own social controls, it is not surprising that Spaniards encountered men who came to San Antonio and refused to leave until they regained their wives or exacted revenge by raids and warfare.11

In the meantime, Natchitoches officials led by Mézières sought a way to maintain the slave markets for Apache women still being captured by Wichita and Comanche warriors, as a means of wooing them to the negotiating table. Spaniards were no strangers to the idea of enslaved Apaches, and with promises of continued exchange, Spanish officials could offer themselves as worthy replacements for the French traders so beloved by Wichitas. The cession of Louisiana from French to Spanish control had direct ramifications on the trade networks among Caddos, Wichitas, and Comanches. Not only had the new Spanish governor of Louisiana, Alexandro O’Reilly, enacted trade restrictions against Norteños; he had also extended official Spanish prohibitions against the enslavement and sale of Indians to Louisiana. Yet, if the Spanish government did not find another channel for the Wichitas’ valuable traffic in women, others nearby would happily meet their needs. Taovayas, for example, pointed out that “they liked the French of the Arkansas River better than those of Natchitoches, since the latter wish nothing but deer skins, which they do not have, while those of the Arkansas River take horses, mules and slaves, by means of which they get what they need.” The combination of Spanish law and contraband competition meant that Mézières faced an uphill road in creating a new outlet for the captives Wichita and Comanche men continued to take in battle.12

The Arkansas post and the region surrounding it remained a hotbed of illicit exchange networks, despite all the Spanish laws, and the extralegal activities there could bring harm as well as profit to Wichitas. In 1770, Mézières wrote to the Louisiana governor about men who had deserted from troops or ships or who had committed robbery, homicide, or rape and were known to be living on the Arkansas River “under the name of hunters.” By taking their “pernicious customs” into these lands, they presented a problem to both the colony’s domestic and diplomatic policies. “They live so forgetful of the laws,” he wrote, “that it is easy to find persons who have not returned to Christian lands for ten, twenty, or thirty years, and who pass their scandalous lives in public concubinage with the captive Indian women whom for this purpose they purchase among the heathen, loaning those of whom they tire to others of less power, that they may labor in their service, giving them no other wage than the promise of quieting their lascivious passions.” Despite the crude implication that Indian women’s supposedly “lascivious” nature mitigated what was clearly abduction and rape, Mézières recognized the devastation rendered Wichita and Caddo communities by the Frenchmen’s extralegal market in captive Indian women. The French “malefactors,” he explained, used the lure of arms and ammunition to encourage Osage warriors living near them to attack and raid bands of Tawakonis, Iscanis, Kichais, and Taovayas “for the purpose of stealing women, whom [the Frenchmen] would buy to satisfy their brutal appetites; Indian children, to aid them in their hunting; horses, on which to hunt wild cattle; and mules, on which to carry the fat and the flesh.” To treat with the Wichitas, Spaniards needed to balance the purchase of Wichita warriors’ own captives with the protection of Wichita women from capture.13

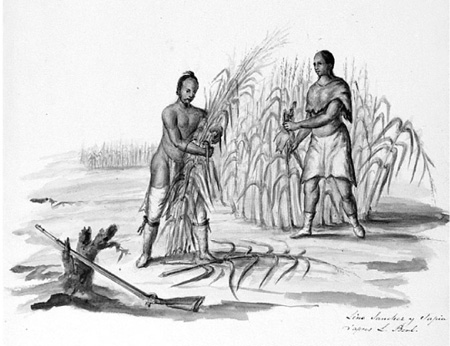

Tawakoni (Wichita) man and woman harvesting corn, illustrating the bounty of agricultural fields cultivated by Wichita women. Note the man’s long-barreled gun laid nearby, indicating the ever-present danger of Osage raiders. Watercolor by Lino Sánchez y Tapia after the original sketch by José María Sánchez y Tapia, an artist-cartographer who traveled through Texas as a member of a Mexican boundary and scientific expedition in the years 1828–31. Courtesy of the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

To secure the Wichitas’ alliance, Mézières argued that a critical element would be creating a market in San Antonio to which Wichitas could bring Apache captives taken in war. If Lipan Apaches could also be weakened through captive taking, then officials saw good reason to encourage it by keeping a market of some kind open for this trade. Unlike in New Mexico, where a traffic in captives took place within the context of ferias (trade fairs), similar commerce did not develop in Texas until after the 1790s, so Spaniards had to rely instead on the venue of diplomatic gift exchange to offer goods and horses to Comanches and Wichitas. Mézières wrote that it would be diplomatically savvy if “permission be given them to sell here the captives that they may bring, because their rescue will be an act of great humanity, as well as because it will serve to encourage such expeditions [against Apaches].” The phrasing of “rescue” and “act of great humanity” were no doubt a sop to Spanish authorities, casting the “sale” as redemption when, after all, Indian slavery was illegal. But sale it was, even if the proceeds went to the church, as he suggested, arguing that “it will be well to fix amicably a moderate price for each individual,” so that “this sale will compensate the missions for the injurious losses which they have suffered from epidemics, war, and the incessant flight of the apostates, while it is a ransom certainly worthy of the favor of the All Powerful.”14

Spanish officials recognized the opportunity both to negotiate an alliance with captors through the ransoming process itself and to obtain for themselves, by commercial rather than violent means, captive Indian women to be used in turn in diplomatic relations with the women’s families. Suggesting the changed value captive women held for Spanish officialdom in the second half of the century, captives were no longer to be included among the “booty” of war apportioned among Spanish soldiers and civilians as servants and slaves. Such distribution of captives, as the marqués de Rubí first expressed in his 1768 Dictamen, “makes impossible their return, which would be capable by itself alone of winning the good will of some nations less cruel than the Apaches.” The 1772 Reglamento followed Rubí’s recommendations to draw a new distinction between captured Indian men and women, directing that men—“prisoners of war”—be sent to Mexico City, where the viceroy would “dispose of them as seems convenient,” while women and children—“captives”—were “to be treated with gentleness, restoring them to their parents and families in order that they recognize that it is not hatred or self-interest but the administration of justice that motivates our laws.”15

Spanish officials in Texas pursued these gendered tactics with a number of different Indian groups and were willing to ransom captives from Apaches as well. When Lipan warriors captured a woman and two boys in a 1779 revenge raid on a Tonkawa ranchería, the governor of Texas offered the warriors eight horses for the three captives. He wanted the boys because they “could become Christians by virtue of their youth,” but his desire for the Tonkawa woman was purely political, since she could be restored to Tonkawa leaders as “proof of friendship.” Interestingly, the Apache men refused, not because eight horses represented an unfair price, but because they did not want to become obligated to the governor by the exchange. They too measured the political benefit-versus-cost ratio of such transactions.16

Then the viceroyalty threw an unexpected wrench into the debate over how to create a market for the Apache women captured by Wichitas, while protecting Wichita women from Osage encroachments. The 1772 Reglamento that guided the realignment of military policy across the northern provinces ordered the abandonment of all missions and presidios in Texas, except for those at San Antonio and La Bahía, in an effort to make the province more defensible. The directive encompassed the entire Spanish population living at the Los Adaes presidio and civil settlement as well as the three missions located among Nacogdoches, Adaes, and Ais bands. Caddo leaders responded with alarm. At a time when Osage, Choctaw, and Chickasaw raids were on the rise, the removal of those settlers signaled the sundering of Spanish alliances with Caddos and Wichitas that had been affirmed only two years before. Hasinai caddí Bigotes postponed a campaign against Osage enemies in order to lead a large contingent of Caddos to meet with Spanish officials at Mission Nacogdoches in protest. Hasinai caddí Texita accompanied Spanish representatives from Los Adaes to Mexico City in the winter of 1773–74 to petition the viceroy for permission for the Spanish families to return. In meetings with Spanish officials, Caddo discourse pointedly emphasized not the loss of Los Adaes soldiers but specifically that of the Spanish families of women and children, in explaining their anger.17

For Caddos, not merely a military alliance but a kin relationship was being broken. In 1768, when fray José de Solís had traveled through the Caddo and Spanish communities surrounding Los Adaes during an inspection of the missions there, the intertwined nature of Caddo and Spanish homesteads and the political significance of women within them was obvious. To visit a mission was to visit the surrounding Caddo hamlets, as families of Hasinais, Nasonis, Nacogdoches, Nabedaches, Ais, and Adaes with their caddís joined the resident Franciscan to greet the missionary’s arrival. They did so not as congregants but as neighbors. Caddo women wearing paint, tattoos, and chamois dresses bordered with numerous beads from European trade held center stage in welcome parties, just as they had so many years before. The women brought “presents” of hens, chickens, and eggs for Solís, and he reciprocated with piloncillo (brown sugar candy), pinole (a beverage made from parched, ground corn mixed with sugar and water), and biscuits. At one village, a woman named Sanate Adíva had even assumed the responsibilities of a caddí, with tanmas (administrative assistants) and connas (shaman priests) in her service.18

When fray Calahorra visited the Tawakoni villages in the 1760s, he too had been welcomed by groups of women and children and had been impressed by the hospitality of well-ordered settlements surrounded by bounteous fields. At the Taovaya villages in the 1770s, principal men greeted Antonio Treviño and Mézières as old friends and showed “the greatest pleasure at seeing and associating with the Spaniards from San Antonio for the first time” by “inviting the women and children to get acquainted with them.” So prominent were women’s labors in Wichita hospitality that Mézières could only conclude in a report to the commandant general that “Their government is democratic, not even excluding the women, in consideration of what they contribute to the welfare of the republic.” If Spaniards now withdrew all their women and families from the region, could there be any greater betrayal of “brotherhood” for Caddo and Wichita men who viewed fraternal families as uniquely tied to one another?19

The Spanish government once again was poised to undermine something they had inadvertently done right in accordance with Caddo and Wichita kinship-based diplomacy. Despite his objections, Governor Ripperdá had no choice but to implement the royal edict. Meanwhile, local Spanish residents were equally distressed at the rupture to their kin associations. Many of the estimated five hundred settlers refused to relocate to San Antonio de Béxar. Thirty-five Adaesano families and an equal number near Nacogdoches fled “into the woods” or to sanctuary in nearby Caddo hamlets. Spanish settlers’ actions clarify the contrast between top-down Spanish policy decided in Mexico City and the on-the-ground experience of Spaniards who understood better the nuances of native-controlled Texas.20

Other Spanish families left women and children among their native kin as a pledge that they would soon return, echoing symbolic Caddo acts at the beginning of the century. On the day of forced evacuation, for instance, twenty-four people stopped at El Lobanillo, the ranch of Antonio Gil Ibarvo’s family since the 1730s, saying that they would go no further. Some claimed illness, while others claimed the need to care for the sick. Altogether this female-dominated group counted at least ten women, including Ibarvo’s mother, sister, and sister-in-law. At the same time, consider what Caddos and Wichitas saw when the government’s orders gave Spanish families only five days to pack their belongings and forced them to leave behind planted fields weeks before harvest time. Commander José González had to go door to door to harry families to leave, while women and children marched on foot and were forced to sell clothes, rosaries, and other personal treasures to buy food along the way—all resulting in the deaths of ten children and twenty adults during the march and thirty more after their arrival in San Antonio.21

In the wake of Caddo, Wichita, and Adaesano determination to keep their communities together, Spanish officials in 1774 approved the establishment of a new town, Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Bucareli, centrally located between San Antonio and various villages of Wichitas, Caddos, and Akokisas, but that lasted less than four years. Tellingly, when Bucareli settlers (125 men, 89 women, and 128 children) fled their homes in the aftermath of the 1778 Comanche revenge raids, they did not run to the better-garrisoned town of San Antonio; rather, they again led their wives and children to asylum among their Caddo neighbors. Nor did they wish to reestablish Bucareli. They preferred to remain among the Hasinai and Nacogdoches villages, using the Comanche attack as an excuse to move back home where they had wanted to be since the evacuation of Los Adaes—in the midst of Caddo hamlets, the Natchitoches post, and the trade and kin networks uniting them. And if they couldn’t live there, they requested permission to move to Natchitoches. Athanase de Mézières’s answer in the face of Spanish predicament and native sentiment was simple: more women. “In order to infuse courage into these [Bucareli] families,” he suggested, “they should be strengthened by others from Los Adaes.” In 1779, again, a new intercultural settlement arose, this time nestled among Caddo hamlets near the former site of the Nacogdoches mission, which gave the new town its name. Spanish officials sought to adopt in limited form the policies of licensed traders and gift giving previously practiced successfully by the French government. To do so, diplomatic relations with Caddos and Wichitas, based first in Natchitoches, extended to Nacogdoches using the contacts and expertise of French traders who came to live in the new settlement. Reflecting the importance of the new community in maintaining good relations with Caddo and Wichita allies, it became the seat of the new lieutenant governor of the province—Ibarvo would hold the post until 1791—with a large stone house immediately erected as the commissary for Indian trade.22

In a region where a captive exchange network had marked the economy for over sixty years, Nacogdoches not surprisingly became not only a symbol of continued intermingling of Spanish, Wichita, and Caddo communities but also a key site for the ransom and restoration of captives—especially when those captives were Spanish women and children from New Mexico. The trade even marked the landscape, with a nearby creek long called “Cautivo.” It was often French traders at Nacogdoches, now Spanish citizens, who alerted Spanish officials to the presence of captives among Wichita bands and who led the diplomatic missions seeking to “redeem” those women and children. The number of traders with enslaved Indian consorts or freed wives also grew. Freed Apache slaves also remained in the area—one Apache man (enslaved as a boy) was even granted a subsistence allowance by the governor “to destroy any desire on his part to incorporate back into his [Apache] nation.” Official censuses only hinted at the numbers, and sacramental records—though listing almost two hundred Indian women and children in the Natchitoches area over the century—also offer only a partial accounting. Nevertheless, by 1803, almost one-quarter of the native-born European population in the region counted Indian slaves among their ancestry, and 60 percent of that number claimed descent directly from an enslaved Indian parent or grandparent.23

The same exchange networks that had been sending Indian women and children to French slave markets in Louisiana in the first half of the century thereby remained in operation, but their endpoints were now increasingly in Texas. In 1774, for instance, news reached Governor Ripperdá that two youths, a Spanish girl and a mulatto boy, had traversed quite a distance through the captive exchange networks crisscrossing New Mexico and Texas. They had first been captured by Apaches, had subsequently fallen into Comanche hands when taken by force from Apache warriors, and finally ended up in a Taovaya village after a Taovaya chief purchased them from the Comanches. Ripperdá tried to ensure that at least two more trips were added to their travels before they came to an end—transferring the children from Taovaya to Spanish hands in Nacogdoches and from San Antonio back to their New Mexico homes.24

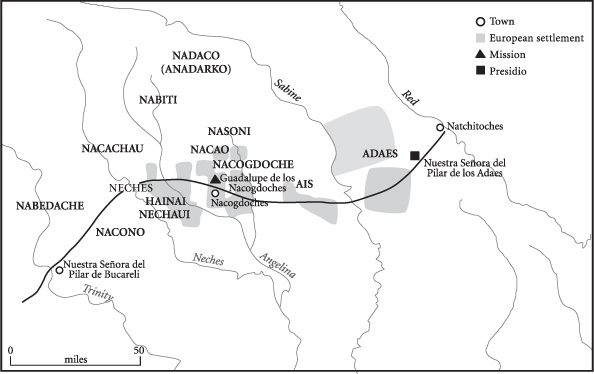

Spanish and French homesteads and settlements intermingled among Caddo hamlets by the mid-eighteenth century. Map drawn by Melissa Beaver.

The routes from New Mexico to Texas and Louisiana might not change, but the number of captive Spanish women and children traveling along it did. Spanish-Indian tensions, not only in Texas but also in New Mexico, made women of every sort, including Spanish, vulnerable to becoming diplomatic or economic pawns. Prior to the 1770s, Wichita and Caddo peoples had only occasionally ransomed Spanish women and children (gained originally from Comanches) through officials in Natchitoches, but in the 1770s and 1780s, records indicate a rise in the number of Spanish captives ransomed in Texas, perhaps reflecting their increasing value as a source of revenue in place of trade. Thus, during the very period when Comanches’ looming presence kept Spaniards mentally and physically besieged in San Antonio, news of their capture of women continuously filtered into town—news that could not help but increase the level of fear, even as more peaceful relations with Wichitas made the return of some of those captured Spaniards possible for the first time. Strikingly, however, every captive was taken in New Mexico, not Texas. The seeming rise in the number of Spaniards held as captives by Comanches might frighten the populations in San Antonio, but they were not personally touched by these losses.25

The ransom received by some Taovayas from Nacogdoches trader José Guillermo Esperanza for a Spanish woman named Ana María Baca and her six- or eight-year-old son spoke to the profits to be gained in the diplomatic trade. For Ana María, they received “three fusils [muskets], three cloth naquisas [netted cloth], two blankets, four axes, three hoes, two castetes [?] with their pipe, one pound of vermillion, two pounds of beads, ten belduques [knives], twenty-five fusil stones [flints], eight steels [for striking flints], six ramrods, six awls, four fathoms of wool sash, and three hundred bullets with necessary powder.” For Baca’s small son, the Taovayas received a similar set of items. Notably, Taovayas were not the only ones who planned to profit from Ana María’s captivity. A Nacogdoches lieutenant, Christóbel Hilario de Córdoba, to whom Esperanza had related his purchase, reported with outrage that Esperanza planned to take the woman and sell her in Natchitoches, “where there could not but be plenty of Frenchmen to purchase her and molest her, as is their custom, since she still is attractive.” Córdoba forestalled the woman’s sale into concubinage by taking her and her son into protective custody. Córdoba’s intervention (which Spanish officials vehemently supported) suggested how aberrant it was that Ana María’s Spanish identity had not excluded her from the category of women whom Esperanza felt he might acceptably sell into the sex trade. But perhaps this “Spanish” woman had developed a native-based identity—she might not have wanted to be redeemed—and that too would have imperiled her.26

She did not seem to fare much better at the hands of the Spanish government. When Governor Cabello began inquiries following her redemption, he received information suggesting that she had formed a union with a Taovaya man during her almost thirteen years in the Taovaya villages. Francisco Xavier Chaves, another former Taovaya captive who had become one of the governor’s interpreters and emissaries to the Wichitas, told Cabello that Baca was twenty-eight years old, a native of Tomé, New Mexico, and had been captured at the age of fifteen, most likely by Comanches, and then sold to the Taovayas. Her age and time in captivity made it clear that her six- or eight-year-old son must have had a Taovaya father. Though Cabello made no observation concerning the mixed-blood identity of Ana María’s son, in letters to the commandant general, he also made no mention of efforts to locate her family. His diffidence regarding reunification with her family was accompanied by the suggestive statement that “I have urged Captain Gil Ibarvo to take the greatest care not to let this woman be lost, as the aforementioned Chaves has informed me further that she is quite good looking.” Did he perhaps think that her family would not welcome her return but that her beauty would offset her experience so that he or his lieutenant governor could marry her off to a resident in Nacogdoches or San Antonio?—making Cabello little better than Esperanza.27

As Wichitas had begun to realize the rewards of ransoming New Mexican women to officials in Texas, Spanish officials tried to increase their financial means to keep such captive diplomacy afloat. Authorities within the Comandancia General used stories like that of Ana María Baca to establish a new program for collecting alms that would help underwrite the expenses of such ransoms across the northern provinces. From the late medieval period in Spain, Spaniards had long maintained such institutionalized collections by both the church and the state in militarized regions. Alms for the ransom of captive women and children had once been one of the “compulsory bequests” made by Texas citizens in their wills, but by the 1770s they had disappeared. Unofficial, ad hoc ransoms of Spanish captives had begun in the 1770s in Nueva Vizcaya, but such efforts had quickly run up against financial exigencies. The concern was that presidial forces would “shrink from actively seeking to secure the ransom or exchange of prisoners” if there were no guarantee of reimbursement for costs incurred. Many captives had no known relatives or their families were too impoverished to assume the costs of either ransoms or reimbursements. Commandant General Teodoro de Croix therefore declared that “since the establishment of this undertaking . . . is of direct concern to humanity, to the Faith, and to the state,” he would seek to create a fund to which the provinces under his command would make “pious contributions.”28

Although Croix made no explicit connection between this order and the ransoms offered to Wichita bands in Texas, his 1781 report on the state of the northern provinces made clear his awareness that Norteños “are particularly sensitive over the failure of their barter with the Louisiana merchants in hides, riding horses, and captives, in exchange for guns, powder, balls, knives, mirrors, vermilion, and other trinkets”—a “form of commerce they call treta.” His successors were far more pointed in making the connection. In 1784, Felipe de Neve’s official bando (edict) “promoting the greater relief of the poor Christians that have the misfortune of groaning under the yoke of captivity which they suffer among the savage Indians,” announced the questionable claim that 152 captives were held by “friendly heathens inhabiting the north of the province of Texas, between those of Louisiana and New Mexico.” Among those mythic 152, the only captives whose identity demanded redemption were captive Spaniards or Christian Indians, according to Neve’s order. Neve’s successor, José Antonio Rengel, reiterated the belief in 152 captives, though he specified even more directly that they were all “in the power of the Taovayas.”29

In 1780, alms gathering began anew in churches, but the “hand of Christian piety” soon proved insufficient, and Croix’s successor, Felipe de Neve, ordered that church collections be supplemented by cabildos throughout the provinces, which were to appoint individuals to “beg for alms from house to house” on one feast day each month. Magistrates and civilian judges would do the same among the “most conspicuous and zealous persons” in their districts. It was not until 1784 that pressure from Neve actually resulted in any alms collection in Texas. In response to Neve’s complaints that Texas officials had failed to contribute to the alms that Spanish law demanded all provinces collect for the ransoming of Christian captives, Governor Cabello explained simply that no captives from Texas had been taken and thus there was little local imperative to give to such a fund. Despite pressures from above, collections remained sluggish in the province. In 1784, for example, officials received 15 pesos and 4½ reales from residents of San Antonio, but nothing from La Bahía and Nacogdoches. The following year, total amounts rose to 35 pesos and 6 reales from San Antonio, 36 pesos and 4 reales from La Bahía, but a measly 6½ reales from Nacogdoches. In 1786, when only 12 pesos came from San Antonio, 20 pesos and 7 reales from La Bahía, and nothing from Nacogdoches, officials decided that downsizing collection responsibilities to a “single, appropriate individual” would be acceptable for the province’s fund. The fund totaled only 105 pesos and 7½ reales by 1788, and no payments had been deducted from it, again suggesting the lack of local demand for such aid in Texas. Again, settlers appeared far more attuned to the real priorities of native diplomacy.30

Indeed, sentiments in local Spanish communities such as Nacogdoches and Natchitoches—which were closely related to neighboring Wichita settlements—apparently diverged the most from those of provincial authorities. Throughout the years, as alms were collected for the ransoming of captive women and children, the Nacogdoches community living nearest the villages of the Taovayas—where the majority of captives were supposedly held—contributed the least to the funds. Their lack of action in either contributing alms or seeking other remedies for the reputed captivity of Spaniards so near their settlement suggests they knew that such inflated numbers had little to do with reality and more to do with political rhetoric. It may also imply localized exchanges taking place beyond the eyes or ears of provincial officials.31

For Wichita men, meanwhile, it was the safety of their own wives and children that increasingly drove their diplomacy as the raids of Osages menaced their families and made trade supplies (or ransom payments) from Spaniards all the more critical to their defensive capabilities. To this end, Wichita leaders put women—their need for well-provisioned male defenders—to rhetorical use within Spanish-Wichita diplomatic and economic exchange. Kichai men, for instance, used women symbolically to emphasize their determination to defend their trade interests. In 1783, an expedition from Nacogdoches led by Antonio Gil Ibarvo visited a Kichai village to persuade the leaders there to limit commerce to only Spaniards in Nacogdoches. Ibarvo particularly desired to cut off their exchange with the Louisiana competition represented by Louis de Blanc and Bouet Laffitte, two Frenchmen based in Natchitoches. Kichai leaders calmly explained that the Frenchmen better served them, offering twice the Spanish rate of exchange for their deerskins and customarily honoring Kichai men with more generous hospitality. In response to Ibarvo’s threat to arrest the French traders and take them off in shackles, enraged Kichai warriors said they would stop him by fighting until all was destroyed and all warriors dead. Even then, they continued, Spanish forces would not be done with them. At that point, Ibarvo “must also kill the women who would defend the French traders”; only then could he “take the traders and the children and bring them with them.” The Kichai men thus used the specter of women fighting to convey the depth of their community’s commitment to the defense of their trade interests and economies. Spanish soldiers would not only be met with a fight; they would have to become the killers of women to force their trade policies upon Kichai men.32

Spanish agents responded in kind, trying to strike fear in Wichita chiefs and warriors by countering with a threat of their own. Sent to meet with Wichita and Taovaya leaders about warriors’ raids in the San Antonio area in response to Spanish trade failures, Pedro Vial warned the men, “If you Taovayas and Wichitas are among those who send their people to make trouble at San Antonio, there will be no one to save you from those who may harm you.” Their raids, he continued, would prove to put not only warriors but also their women and children at risk. Vial asserted, “What you [must] wish is to see your villages destroyed and your families enslaved by other nations.” The destruction—of a quite thorough nature—would not come at the hands of Spanish soldiers, however. All that Spanish officials had to do, Vial threatened, was cut off the supply of trade goods and firearms that enabled Wichita men to defend themselves. Then their Indian enemies “will steal your sons and your women, and you will not be able to go out to hunt to support your families, or to sleep in peace, and then the other nations that are friends of the Spaniards will hate you.” In other words, the men would no longer be respected as men. To drive the point home that the warriors’ actions put their women in danger equal to that faced by men on the battlefield, Vial added that “if you wish to make war on the Spaniards, it is not necessary for the men to go; send the women—which will be the same.” He thus made more potent the Spanish threat by aiming it at Wichita women, but put the blame for any harm that might come to the women squarely on the shoulders of Wichita men. In the process, he defamed Wichita manhood for putting their women in danger.33

When such rhetoric did not work, Wichita leaders simply returned to the diplomatic use of captive women to gain leverage in negotiations. Thus did Taovaya chief Qui Te Sain offer five Spanish captives to Louisiana governor Bernardo de Gálvez as a means of getting material aid for his warriors who were struggling to hold off Osage onslaughts in 1780 with inferior weapons. In 1784, when newly elected Taovaya chief Guersec and his principal men endeavored to make amends for the horse raids of their young warriors, they sent four emissaries to San Antonio along with three European men who had been living among Taovayas for years. Guersec’s seven representatives carried with them a message that Taovaya leaders were prepared to release into Spanish custody “all captive men and women who remained with them and would do so as soon as a trade thereof was arranged.” One of the three European residents of the Taovaya village, Pedro Vial, carried with him proof of the captives living there: a six-year-old Apache child and an eighteen-year-old Spanish woman named María Teresa de los Santos he had purchased from Taovaya men before his departure. Only one of the girls garnered Cabello’s concern, as the governor wrote simply, “the Apache received none of my attention, but the other one did because she was a Spaniard and a Christian.” Cabello promptly gave Vial sixty pesos after being shown the list of goods that Vial had given the Taovayas for her; no amount was offered for the Apache girl, suggesting that she remained Vial’s property. In addition to renewing Spanish obligations to distribute annual presents and supplies (as promised in earlier treaty agreements), Cabello added five hundred pesos worth of goods to the total as ransom payment for the captives—who were to be brought the following summer to Nacogdoches, where Taovayas, Wichitas, Iscanis, and Tawakonis would claim their annual supplies. Thus, Wichita leaders secured a “bonus” in addition to the renewal of trade goods. So was a story line set that played out again and again, as Spanish and Wichita leaders used female captives to heal breaches created by their respective failures of trade and horse raiding.34

Lipan Apaches too pursued new forms of peace from the 1770s onward, but they faced a much rougher path to that goal because official Spanish policies directed that Texas seek the alliance of Wichitas and Comanches to the detriment of Apaches during this period. Recommendations from the Comandancia General repeatedly swung back and forth between war and peace, in tune with the wavering state of the treasury and the military, both of which determined whether the forces that could be put in the field had any chance of survival, much less success. De facto peace policies came into being in localities like Texas before they were institutionalized at the level of the commandancy. So Apaches had to persuade Texas officials first, and changes in Apachería aided that process. By the 1770s and 1780s, eastern Apaches had splintered into so many small bands that they were making decisions almost on a family-by-family basis. In this context, Lipan leaders developed dual strategies, one seeking peace and alliance with Bidais, Hasinais, and Tonkawas that would open up Louisiana markets to their trade, the other returning to former plans to establish civil settlements and mission residence in or near San Antonio that might by extension gain them a defensive alliance with Spaniards. Both plans placed women at the heart of Apache diplomatic efforts.35

Spanish policy shifts inadvertently opened up opportunities on which Lipan leaders could capitalize. Once Caddo and Wichita peoples had negotiated peace agreements with Spaniards in San Antonio in the 1770s, their raids on Spanish herds and a steady supply of horses for the Louisiana trade diminished. They had both built extensive herds that their defensive and commercial needs demanded be maintained. As a result, their trade with native peoples in central Texas expanded. The constant debt or lack of supplies of resident trader José María Armant, whom Spanish officials stationed at Nacogdoches in the 1780s, by default strengthened the Caddos’ ties to their native trading partners even further. Bidai allies with whom Hasinais had long shared ties through exchange and marriage had already established trade with Lipan Apaches by midcentury. French traders in turn had regularly visited Bidai rancherías along the Trinity River southwest of the Hasinai villages since the 1740s and by the 1770s had begun trading arms and ammunition in exchange for horses brought to the Bidais by Lipan Apaches. Thus, Bidai leaders represented crucial agents through which Lipan Apaches might seek inclusion in the kin ties the Bidais enjoyed with Hasinais. For Bidais and Hasinais alike, the Lipan Apaches could offer a new source of horses, while their trade contacts could bring Apaches their first chance to obtain French arms and ammunition.36

Apache overtures initially sought to open trade ties with offers of female captives taken earlier from Hasinai settlements—women whose return to their families might serve as gestures of conciliation. These gestures’ meaning increased in the wake of epidemics that devastated Hasinai families in 1777. Captive women provided a unique avenue by which Apaches could put the bounty of past hostilities to work in the name of peace with their former Caddo enemies. Captive diplomacy among Apaches, Bidais, and Hasinais would have to be effected in the face of Spanish opposition, however. When Apache leaders first made diplomatic overtures to Hasinais via their Bidai allies in the late 1770s, they did so right under the nose of Spanish officials. The Spanish settlements of San Antonio and La Bahía proved ideal locations to make contact with visiting Hasinai leaders, who traveled there to maintain relations with Spanish officials and thus came within the reach of Apache leaders who could approach them within the neutral confines of the two presidios.

News reached the Lipan encampments in 1779 that Hasinai caddí Texita had arrived at La Bahía with a delegation to meet with Governor Cabello concerning the shortage of traders and trade goods being made available to their villages—the news likely coming via Bidais who also visited the presidio that week. Lipan chiefs El Joyoso, Josef Grande, Josef Chiquito, El Manco Roque, and Manteca Mucho promptly gathered an estimated six hundred men and women to travel there as well—signaling their peaceful intent by both the women in their party and the four Hasinai captives they brought with them to return to Texita. Unfortunately, Cabello received word of their approach and hurried the Hasinais’ departure with false warnings that Apaches were coming with hostile purpose, sending a military escort of seven soldiers to ensure that the two groups did not meet. For Spaniards, only “disastrous results” could ensue from such a meeting, Cabello believed, fearing that such an alliance was sure to turn against Spaniards. Covering all his bases, Cabello similarly lied to Tonkawa leaders about Apache intentions a couple of months later in hopes of preventing their rapprochement as well.37

Apache leaders remained undaunted, however, and in the company of Bidais approached a small party of Hasinais visiting with Cabello at La Bahía the following year. Again, Cabello did everything he could to keep the two groups apart, this time barricading the Hasinai caddí, his wife, and two warriors in their quarters within the garrison to prevent contact. Yet, Lipan chief Chiquito and his men merely ignored the Spaniards and spoke through the door to the Hasinais, offering “to give them horses, arms, and even women” if they would go with them to another location to discuss peace and an alliance. Finding the two chiefs talking with one another thus, Cabello promptly expelled the Apache men from the presidio. Seeking to avert the “coalition” so desired by Apaches, Cabello tried to persuade the Hasinai leader and his wife that, once they were enticed away, the Lipan warriors secretly planned to kill them so that they could “dance many mitotes with their scalps.”38

Events two years later indicated that Cabello had failed again and, more significantly, that the Lipan leaders’ “enticements” through the door involved not only returning female Hasinai captives to their families but also uniting Lipan women in marriages with Hasinai men. Diplomatic doors could be opened with the return of captured women, and intermarriage could strengthen amity with kinship affiliation. Intermarriage, it seems, had become a crucial means of Caddo-Apache alliance. When a Hasinai man and his wife from the Angelina village visited San Antonio in 1782, Cabello learned, much to his chagrin, that the woman was not a Hasinai but a Lipana. She had been captured by Taovayas in 1779 and sold to a French trader in Illinois before the Hasinai man rescued her from enslavement. Now married, he was bringing her to visit with her family and hold diplomatic parleys with Apache men; they only passed through San Antonio because it offered a good resting point along the way to the Apache encampments. Not so coincidentally, that fall Lipan, Mescalero, and Natage Apaches attended a huge trade fair held by Hasinais, Bidais, Mayeyes, Akokisas, and Tonkawas, where they traded 1,000 horses in exchange for 270 guns and ammunition. Despite continued attempts by Spaniards to keep these groups at odds, signs of alliance only grew along with increasing Hasinai and Tonkawa resistance to Spanish proposals for campaigns against Apaches. As native relations yet again developed far from possible Spanish surveillance—despite Spanish spies being sent to the trade fairs—officials took special note of the identity of women in diplomacy parties whenever they came to San Antonio and La Bahía. In 1784, they recorded the visit of yet another party of Hasinais, including a Lipan woman among the dignitaries’ wives. An Apache woman named Teresa and her son seen at a Tonkawa village during another trade fair told them that intermarriages had also begun to link Lipan and Tonkawa communities together.39

From a Caddo standpoint, these unions were simply part of a long tradition of intermarriage as a means of forging alliances and, in concert with unions formed with Bidais, Mayeyes, Tonkawas, and other native groups of central Texas, helped replenish populations devastated by smallpox epidemics in the late 1770s. Newly brokered unions built on others with captive and enslaved Apache women and their descendants, whom the Wichitas and the Comanches had sold into Caddo territories in Texas and Louisiana throughout the century. Many of the European traders who bought and sold Apache captives and maintained their own unions (both licit and illicit) with Apache women may have also encouraged Hasinais to listen to Lipan peace and trade overtures late in the century. François Morvant, for instance, had lived as a resident trader among Caddos and later Wichitas with his Apache wife, Ana María, and their five children before moving his family to Nacogdoches in the last decades of the century. Marriage and baptism records testify to the presence of enslaved and free Apache women as concubines, wives, and mothers in Natchitoches and Nacogdoches well into the nineteenth century.40

These intertwined relationships mirrored a trade network that slowly emerged in the 1780s linking Natchitoches and another Louisiana outpost at Opelousas with Hasinais, Tonkawas, Bidais, Mayeyes, Atakapas, Akokisas, Cocos, and Apaches. Great trade fairs involving thousands of men, women, and children from these bands grew in number, bringing Apache family bands with horses and mules taken from Spanish settlements in Texas and Coahuila to trade for muskets, powder, and bullets. These native trade alliances held despite Spanish efforts to sever their ties—efforts that included cutting off annual gifts and supplies to the Caddos and their central Texas allies (now called the “Twenty-One Friendly Nations”), the assassination of Tonkawa chief El Mocho (an Apache who had been taken captive, adopted, and then assumed leadership among the Tonkawas, championing trade relations with Lipans), and the threat of assassination against his successor, El Gordo, if he did not cut off trade relations with Apaches. Yet, the kinship ties of intermarriage and the exchange of captive women and children had made Caddos, Bidais, and their allies “the most steadfast friends” with Lipans, friends who resented Spanish strategies that made them suffer.41

Relations between Spaniards and Lipans also gave proof of the disjuncture between official policy and life on the ground—even in San Antonio, under the very nose of diplomats such as Governor Cabello. Peaceful relations at the local level often gave the lie to official declarations of hostility between Apache and Spanish peoples of Texas. Indeed, Spanish policies vacillating between the desires for war at higher levels of the Spanish bureaucracy and the realities of friendships in San Antonio made diplomatic relations quite mercurial. Many a high-ranking official would have agreed with Commandant General Teodoro de Croix when he complained in 1781 that Apaches came to the negotiating table “overbearing and proud, and with hands bloody from victims, vassals of the king, whom they had sacrificed to their fury.” Rather than showing appropriate humility, the warriors arrogantly “demanded food, presents, and gifts.” For him and others in the Comandancia General, it took a royal order issued on February 20, 1779, temporarily halting the use of open war, to make them accept the need for negotiation. Croix tried his best, nevertheless, to restrict the use of diplomacy, directing that presents be given only “at suitable times so that [Apaches] may not be given cause for conceit or arrogance nor acquire our gifts as if we had been forced to give them,” and they should be given only to those Apache men who “evidenced voluntary and real subjection.” Such moments proved rare indeed. Yet, as Apache family bands in Texas turned to Spaniards for alliance and “protection,” their actions could be framed by local officials as constituting these bands’ acceptance of the commandancy general’s new peace establishments (establecimientos de paz) policy. In hopes of ending the Apaches’ raids and making them dependent on Spanish officials, the program in 1786 began offering them incentives—subsidies, goods, arms, and ammunition—if they agreed to settle near the watchful eye of presidios. They would be termed communities of “Apaches de paz.”42

In the meantime in Texas, Apache warriors and Spanish soldiers and citizens who interacted on a daily basis knew better than remote officials what the daily exigencies were that brought their families together. At this local and more personal level, Spanish-Apache ties could be seen more clearly, especially as Apaches increasingly sought out civil settlements near Spanish presidios like Béxar, where the defense of their women and children could be joined with that of Spaniards. Now it was families and not just warriors whom Apaches wished to unite at such sites. Since midcentury, Spanish residents had been visiting Lipan rancherías regularly, staying for days to trade (illicitly) guns, ammunition, French tobacco, and other goods in exchange for mules, horses, bison hides, and deerskins. Through the exchanges, some Spaniards learned the Lipan language. Others gained friends with whom they shed tears over Apache loved ones who were lost to Comanche raids.43

By the 1770s, friendly sentiment toward Lipans was widespread in the San Antonio community. In 1779, when rumors reached San Antonio of a proposed Coahuila-based campaign against Lipan Apaches, Cabello reported that in contradiction to his own support of the plan, a majority of civilians in town were “very anxious about the harm which will befall their friends the Lipan Apaches,” when soldiers and officers leaked the news to them. “For in spite of the injuries and damages suffered at the hands of these Indians,” Cabello wrote, “so much affection is held for them, that I fear, and not without reason, that these people are capable of warning the Apaches of this news.” That summer, Lipan chief El Joyoso visited the home of retired presidial captain Luis Antonio Menchaca to ask him where Spaniards in San Antonio stood vis-à-vis the situation in Coahuila. Menchaca, in the company of his Lipan friends, took the question directly to Governor Cabello. Before this gathering, Cabello agreed to support their permanent settlement in Texas under peace accords that would exchange defensive aid on the part of the Spaniards with the return of stolen horses and mules on the part of the Lipans. A month later, six hundred Apache men and women camped near San Antonio while their chiefs, El Joyoso, Josef Grande, Josef Chiquito, El Manco Roque, and Manteca Mucho, frustrated Cabello by their efforts to meet with Hasinai leaders. Yet, even then, Cabello had to admit that “these Indians were so human and were so admired by everyone here.”44

Whereas the security of Apache women had once kept Apache men suspicious of Spaniards, now it had the power to bring them together—perhaps because both Apache and Spanish women now lived in the same locale around San Antonio. The bonds between Spanish soldiers and Apache warriors reflected their shared struggles to defend their families and communities, oftentimes side by side. During the marqués de Rubí’s inspection of the Béxar presidio in 1767, a mustering of troops by Captain Menchaca had provided a startling sight for the marqués when the soldiers appeared in unofficial and rather unmilitary dress, each using handkerchiefs, lace, buttons, and gaudy ornaments to create his own individual colors and insignia—suggestive of the individual war dress and decoration of Lipan warriors alongside whom they had been fighting. The similarity of the Spaniards’ dress to that of their native allies may have reached such a degree that it became a concern for higher authorities. In 1777, orders came down from the Comandancia General specifying the proper uniforms to be worn by the military on the northern frontier—from detailed description of the cut and color of coats and trousers to the two musketlike ornaments made of five threads of gold that might adorn their collars—as well as immediately prohibiting “bragging” on oval leather shields via “extravagant design.” By regulation, only the name of the presidio, in medium letters, could appear on shields.45

Spanish-Apache friendships became multigenerational as time passed. Ten years after Captain Menchaca’s soldiers had shocked Rubí with their native-inspired dress, Menchaca’s son used his position as a powerful merchant and storekeeper in San Antonio to uphold his personal friendship with Lipan leaders, providing the Lipan men with food and goods for their wives and children, no matter what the official trade restrictions were. Thus, in 1779, when seven Lipan chiefs visited San Antonio, it was to his “very good friend” Luis Mariano Menchaca rather than to Governor Cabello that chief El Joyoso gave a ten-year-old captive Mayeye girl as a gift. The good faith shown by the San Antonio merchant did not merely help to supply Lipan families materially; Menchaca also was there at crucial moments to aid their safety and diplomacy. When one hundred Taovaya warriors came to the areas of San Antonio and La Bahía on a raiding spree for horses and Apaches in the summer of 1784, Menchaca quickly warned Lipan families and urged them to cut short a trip with other Apaches hunting for bison along the Guadalupe River. In 1786, after Tawakoni, Iscani, and Flechazo warriors attacked Lipan rancherías, San Antonio residents hastened to check on their Apache neighbors, only to find that the women, children, and elderly had been sent into the wilderness for safety while the men remained in such a state of mourning “that they [the Spaniards] hardly knew them, considering how humane and jovial they had been.”46

As official Spanish-Apache relations soured in the wake of the Comanche peace, the personal power of individual male leaders first imperiled and then saved the situation by strategic use of the symbolism and reality of women’s presence. Despite good relations between families of Lipan warriors and Spanish soldiers and citizens, in 1784 Governor Cabello joined his administrative peers in Coahuila and Chihuahua in declaring that Apaches deserved “no quarter” and encouraged Wichita and Comanche campaigns against Lipan bands. Four years earlier, when the smallpox epidemic swept through, this same man had said he hoped “that not a single Lipan Apache lives through it, for they are pernicious—despite their apparent peacefulness and friendliness.” In the same vein, following the Wichita raids on Lipan rancherías in 1786, Cabello used self-confessed “duplicity” and “tricks” in an attempt to set up chief Zapato Sas’s bands for an ambush by forcing them to move away from the San Antonio vicinity and into the area of San Sabá—the site of the infamous 1758 Norteño attack. Promising Spanish military support and trade, but only if the Lipans told him where they would establish a permanent encampment, the governor then turned around and sent word to Comanche and Wichita warriors where to find them. Even as he schemed at their destruction, Cabello also demanded rituals of humiliation as “proof of peace” from Lipan leaders—nothing short of their surrender or military defeat would serve his purposes. In response, Lipan leaders washed their hands of Spanish officialdom, exasperated at the lack of respect shown them by Cabello. Precisely at the moment when a truce seemed impossible, though, Spanish and Apache leaders found new means of conciliation. A change in administration at the end of 1786—with Governor Cabello replaced by Rafael Martínez Pacheco—ensured that the powder keg did not explode.47

Suddenly, Lipan leaders found their overtures about using a permanent mission and secular settlements to link their families more tightly with those of Spaniards welcomed by the new governor as well as by church and military leaders. Martínez Pacheco, a seasoned veteran of the Texas borderlands was a man Lipan headmen could trust. Apaches reenvisioned the mission-presidio complex at San Antonio as an ideal center from which to build a Spanish-Apache alliance. Martínez Pacheco agreed, reporting to his superiors that without a safe settlement for their families, the Apaches’ subsistence would have to rely on horse and cattle raiding that in turn would hurt Spanish families. San Antonio’s cabildo praised the permanent settlements arranged by Lipan leaders in conjunction with Governor Martínez Pacheco as a means of stopping the taking of mesteñas (wild, unbranded horses) and the illicit slaughtering of great numbers of domestic livestock and orexanos (wild, unbranded cattle) by Apache men seeking to feed their families. In an unusual twist, even Comanche leaders felt that such settlements would aid the peace, declaring they would attack Apaches only “as long as they do not find them settled in permanent towns with the Spanish.” Finally, Lipan leaders could build upon ties of friendship and kinship with the San Antonio community and do so with the support of the Spanish administration.48

Relations of honor between individual Spanish and Lipan men proved strong enough to overcome Apaches’ fears for the safety of their women and children. In 1787 soldiers from the Béxar presidio under the command of Lieutenant José Antonio Curbelo and alférez (sublieutenant) Manuel de Urrutia promptly went to the aid of families of Lipan Apaches moving from their gathering place at Arroyo del Atascoso to the town of San Antonio. Five chiefs, including Josef Chiquito and Zapato Sas, greeted them with “great affection as they had done on other occasions,” expressed the wish that the Spaniards had given warning of their coming so that they could have ridden out to greet them properly with a delegation, and gratefully received the provisions of corn, biscuits, meat, candy, and tobacco brought for their women and children. In thanks for the promised escort, horses to carry their women and children, and the goodwill supplies, one of the leaders warmly welcomed them to his home “along with all the other Indians and children, amid great rejoicing.” Evening prayers preceded a “great dance” lasting into the wee hours of the morning. Meanwhile, however, chief Casaca brought rumors from San Antonio that more soldiers were on the way to imprison and kill them, that other chiefs were even then imprisoned at the Béxar presidio, and that they would all be shackled and sent off to Veracruz and then to “some dwellings which were located in the middle of the ocean [Cuba], there to live out their days in labor,” a warning that sent the women and children fleeing in tears. Seemingly, the Apaches’ doubts had not all been put to rest, but after some hours, Curbelo, Urrutia, and the Lipan chiefs succeeded in calming everyone’s ragged nerves.49