Chapter 1

Southern Rights Inviolate

William Watson had not come to America to fight. Born in a small village outside Glasgow, Scotland, he migrated to Louisiana in the 1850s. Thirty-five years old when secession fever swept over the Pelican State, he was a man of property and standing in Baton Rouge. Part owner in several businesses, with interests in coal, lumber, and steamboats, he had no direct stake in slavery. Thus he watched with concern as the convention meeting at the statehouse in January 1861 declared Louisiana an independent republic. The following month, Louisiana’s representatives joined other Southerners in Montgomery, Alabama, to establish the Confederate States of America. Six months after that, Watson found himself staring into the muzzle of a twelve-pound howitzer as his regiment charged a Union battery at Wilson’s Creek.1

Of the states that contributed troops to the battle, Louisiana was the first to take up arms. William Watson went to war not because he was a Louisianan, but because he was part of a Louisiana community that expected him to fight. The road he followed to war had many parallels, North as well as South. The war concerned the future of slavery in American society, but social forces also exerted extraordinary force on those confronting the crisis. These forces included community values, social expectations, and Victorian concepts of courage, honor, and masculinity. The actions of generals and the movements of troops are relatively easy to trace. But a battle can be fully understood only when one also considers both the motivations and the experiences of the common soldier. In the case of Wilson’s Creek, the manner in which the troops were raised and organized, their past experiences and training (or lack thereof), their image of themselves, and their understanding of what they were doing directly influenced how the battle was fought and the soldiers’ interpretation of what they accomplished by fighting it. It was the first summer of the war, and both men and values were tested.

One of the ways Watson had established himself as a bona fide member of the Baton Rouge community was by joining a company of volunteers. Replete with “tinsel and feathered hats,” the Baton Rouge Volunteer Rifle Company, formed in November 1859 in response to John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, was typical of many such organizations that existed on the eve of the Civil War.2 Supplementing the largely moribund militia guaranteed to the states under the Second Amendment of the Constitution, some volunteer companies were primarily social organizations, while others took military training seriously. However varied in character, they were the nuclei around which were formed the regiments that were to clash at Wilson’s Creek.

The creation of those regiments is an interesting story. Studies of the coming of the Civil War naturally stress the divisions within American society, but an examination of how the opposing units came into being underscores their commonalities. The goal here is not to determine which of the Northerners who fought at Wilson’s Creek were abolitionists, or how many of the Southerners who sacrificed their lives there were impelled more by states’ rights than by a desire to perpetuate slavery. The goal is to understand these men in the context of their society and analyze their experiences, particularly in relation to their home communities. This is an inexact process, heavily dependent on the sources available for study, but it reveals much about the human condition.

Fort Sumter surrendered on April 14, 1861. In Washington Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers, and from Montgomery Jefferson Davis soon made a similar appeal. But companies had been forming spontaneously throughout Louisiana since the state’s secession in January. Government officials struggled to create the bureaucracy necessary to organize, arm, and sustain military forces adequate to meet the state’s needs. They had at their disposal substantial captured Federal property, including the armaments from the U.S. arsenal at Baton Rouge. But while key points were quickly fortified, most of the nascent soldiers remained at home until the Fort Sumter crisis made war a reality. Thereafter, the pace of preparation accelerated.3

As soon as word of the bombardment at Charleston harbor reached Baton Rouge, Watson’s unit commander, Captain William F. Tunnard, called his men together to consider the crisis. They voted to create a new company, the Pelican Rifles, and offer their services to either Governor Thomas O. Moore or the Confederate government, as needed. The local press reported that the Pelican Rifles were quite willing to go to “Sumter, to the d—l, or wherever the Governor might order them to go in defense of the state or the seven-stared Confederacy.”4

Significantly, the vote was unanimous. Watson had “no sympathy with the secession movement,” although he admitted irritation at the “shuffling and deceitful policy of Lincoln’s cabinet.” Yet he could have easily dissented, as a nonslaveholder, or abstained, as a foreigner by birth and a man past prime military age. Instead he voted to go, because, as he would recall, he sought adventure and feared that staying home would harm both his personal reputation and that of his business. As Baton Rouge had a population of less than 5,500, the positions taken by its leading citizens could not escape notice.5

As a Southerner by adoption, Watson may also have been influenced by the fact that the commander of the Pelican Rifles, William F. Tunnard, was a native of New Jersey. A carriage maker, Tunnard had moved to Baton Rouge with a family that included his son, William H. Tunnard. Twenty-four-year-old Willie, as the younger Tunnard was called, had also been born in New Jersey. He was educated at Kenyon College in Ohio, yet like his father he joined the local militia and supported the Confederacy. Tunnard was a sergeant in his father’s company.6

Across the state prewar volunteer units placed advertisements in the local papers to bring their strength up to wartime levels of approximately one hundred men per company. New companies were formed as well, as plans solidified for a rendezvous of the volunteers in New Orleans. Governor Moore first issued a general appeal for men and later announced procedures for contacting the state adjutant general and enrolling for service. The public response was enthusiastic. For example, within a week of the governor’s announcement, Shreveport raised two companies, one of which was Captain David Pierson’s Winn Rifles. A third unit was also forming, marking a substantial contribution for a community of less than 2,200. Nearby Morehouse Parish, with only about 800 registered voters, put over 400 men in the field.7

Going to war was preeminently a collective experience, for it involved the entire community, not just the men who became soldiers. This can be demonstrated in Louisiana, but to an even greater extent in other states, particularly in the North, where much more historical information has survived. Throughout the 1861 campaign in Missouri, the soldiers of both sides possessed a community identity that remained as strong, if not stronger, than their allegiance to their respective regiment, state, or nation. “The soldiers of 1861,” Reid Mitchell notes, “were volunteers—independent and rational citizens freely choosing to defend American ideals. In a sense, the soldiers’ reputation would become the home folks’ reputation as well.”8

Watson’s company required relatively little preparation. Already armed and uniformed in gray, the men lacked only camp equipage, yet the citizens competed with each other to see to their possible needs. Watson recalled that elderly men and women “furnished donations in money according to their circumstances,” while “merchants and employers, whose employees and clerks would volunteer for service, made provision for their families or dependents by continuing their salaries during the time they volunteered for service.” In many cases parish-level governments appropriated substantial sums of money to support both the enlistees and their families. No one expected a long war, and such encompassing community support left men of military age with few excuses for remaining at home. Women exerted direct social pressure on men to enlist. According to a young Louisiana volunteer, “The ladies will hardly recognize a young man that won’t go and fight for his country. They say they are going to wait until the soldiers return to get husbands.”9

Soldiers maintained a sense of community identity because most of them came from the same location and enlisted at the urging of some prominent member of their hometown, native village, or county of residence. One such man was Samuel M. Hyams, who despite nearly crippling arthritis raised the Pelican Rangers. A native of Charleston, South Carolina, he was a longtime resident of Louisiana, a planter and a lawyer, serving over the years as clerk of the district court at Natchitoches, register of the land office, sheriff, and deputy U.S. marshal. After the men were mustered into service, they elected Hyams captain. This was a typical pattern.10

Community pride ran high. The Baton Rouge Daily Advocate boasted that the city’s Pelican Rifles was the first company raised outside of New Orleans to offer to serve anywhere in the Confederacy. When companies such as Tunnard’s left for the New Orleans rendezvous, the local populace always turned out in force. Hundreds, for example, gathered at the wharf in Baton Rouge on April 29 to witness the arrival of the steamer J. A. Cotton to transport the city’s volunteers downriver to the Crescent City. The mayor made a few patriotic remarks, and when the boat came into view at 11:0 A.M. cannons boomed, cheers rose, and a local band struck up martial tunes. With some confusion, amid tears and final hugs from loved ones pressing closely in, Tunnard’s men finally got on board and the lines were cast off. Similar scenes were enacted across the state.11

Not surprisingly, conditions in New Orleans were chaotic and the process of mustering-in was somewhat haphazard. Watson recalled that they had no sooner docked on April 30 when Brigadier General Elisha L. Tracy boarded the vessel and without ceremony quickly swore them into Confederate service. Another soldier, however, remembered being sworn in on May 17, by a Lieutenant Pfiiffer, and official records back up this date. Because Tracy at that time held only a state commission in the Louisiana militia, Watson probably confused two separate occurrences, as most troops were first sworn into state service and later mustered into the Confederacy’s volunteer force, officially labeled the Provisional Army of the Confederate States.12

The arriving troops were quartered at Camp Walker, a training center that had been established at the Metairie Race Course, just upriver from New Orleans. As the racing season had ended on April 9, no sacrifice of entertainment was required of the local citizenry. Although placed on the highest ground in that area, the camp was surrounded by swamp and lacked both adequate shade and fresh water. The new recruits were immediately exposed to disease, the greatest killer of the Civil War. Although some 3,000 volunteers had assembled by the first week in May, only 425 tents were available. Men crowded into nearby buildings or simply sprawled in the mud, for it rained heavily. It was quite a change, wrote one volunteer, from “the comforts and luxuries of home-life.”13

On May 11 the Pelican Rifles became part of the 1,037 men organized as the Third Louisiana Infantry. The regiment was composed of companies raised in Iberville, Morehouse, Winn, Natchitoches, Caddo, Carroll, Caldwell, and East Baton Rouge Parishes. The companies were immediately given letter designations, yet contemporary newspaper articles, wartime correspondence, and the soldiers’ postwar recollections testify to the persistence of community identification. Although proud of their regiment, the men continued to think of themselves as the Iberville Grays, the Morehouse Guards, the Shreveport Rangers, or the Caldwell Guards. These designations, under which the volunteers had originally come together, were not nicknames but their primary identification, a bond with the home community. “Be assured, Mr. Editor,” a soldier wrote the Daily Advocate, “that the Pelicans will never give Baton Rouge cause to be ashamed of her young first volunteer company.” Hometown newspapers following the Third Louisiana and the other regiments, North and South, that participated in the 1861 campaign in Missouri continued to refer to “their” companies utilizing the local designations, such as Pelican Rifles, in preference to the regimental designation. They published soldiers’ letters that reported rather graphically to the community the welfare and status of the hometown company, paying particular attention to the sick, listing them by name and describing their condition. When “Bob” wrote his hometown paper that “I must give the full meed of praise which is due our worthy Captain and his officers, for their kindnesses to their men,” he was not engaging in idle flattery, but reassuring the homefolk of their fitness for command. “Under such officers,” he continued, “the Pelicans are bound to make their mark.” By extension, so would Baton Rouge.14

If anything, the Louisiana volunteers were overly sensitive about their reputation with the folks back home after departing for New Orleans. In May, the Pelican Rifles published statements in both the Daily Advocate and the Weekly Gazette and Comet of Baton Rouge to deny a rumor that they had been mistreated by the state authorities, were demoralized, and had threatened to desert. “We are perfectly satisfied and happy,” the statement ran, “and wish no better name than that of the Pelican Rifles, which none of us will ever dishonor.” Every member of the company signed the statement.15

Strong, if friendly, rivalries existed between the companies of the Third Louisiana, and these rivalries were based in no small part on community. George Heroman bragged about the Pelican Rifles to his mother: “When we passed through the city and whenever any visitors come here they always remark that our company is the best and the cleanest looking company on the grounds.” But he was only echoing the opinion of his hometown paper. “Amid all the other companies which have formed in our State,” ran one article in the Daily Advocate, “we will venture the assertion that this company can boast of as great a proportion of sterling worth—the real ‘bone and sinew’ of the country—as any other.” Watson also believed that the Pelican Rifles were “the crack company of the regiment,” noting that they worked to maintain their superiority over the others by proficiency in drill.16

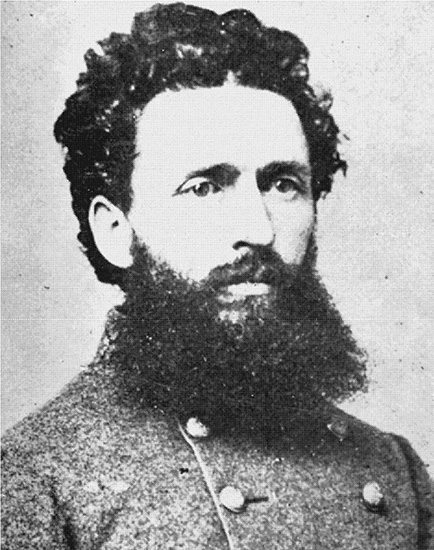

Drill was important to the regiment’s newly elected commander, Colonel Louis Hébert. Watson remembered Hébert as “something of a martinet,” a man who “took pride in his military knowledge” and was “a stickler for military form and precision in everything.” A forty-one-year-old native of Iberville Parish, Hébert had graduated from West Point in 1845 but resigned after only two years’ service to help manage his family’s sugar plantation.17 Because sugar produced through slave labor resulted in great wealth for Louisiana planters, Hébert’s reasons for backing secession might appear obvious. But who were the other men of the Third Louisiana and why did they enlist?

Unfortunately, detailed social studies exist for only a few Civil War regiments, and the Third is not one of them. We are left with the assessments made by the men themselves. Captain R. M. Hinson assured his wife that the Morehouse Guards—Company B—were “all high toned gentlemen” whom he felt honored to lead. One hesitates to question Hinson’s laudatory appraisal, as he paid for the privilege of leading these men by dying at Wilson’s Creek. But the Morehouse Guards—indeed, all the companies of the Third Louisiana—were probably a mixed lot. The best description comes from Watson, who recalled that his company contained planters and planters’ sons, farmers, merchants and sons of merchants, clerks, lawyers, engineers, carpenters, painters, compositors, bricklayers, iron molders, gas fitters, sawmillers, gunsmiths, tailors, druggists, teachers, carriage makers, and cabinetmakers. Although most of them were either natives of Louisiana or Southern-born, thirteen were from Northern states; there were also men from Canada, England, Scotland, Ireland, and Germany. Watson calculated that the number “who owned slaves, or were in any way connected with or interested in the institution of slavery was 31; while the number who had no connection or interest whatever in the institution of slavery was 55.”18

Colonel Louis Hébert, Third Louisiana Infantry (Library of Congress)

The Third Louisiana went to war under a blue silk flag bearing the state seal on one side and the words “Southern Rights Inviolate” on the other.19 Although the privilege of owning slaves was clearly among the rights that Southerners were determined to defend, Watson was convinced that “very few” of the soldiers actually enlisted over “the question of slavery.” The “greatest number were motivated only by a determination to resist Lincoln’s proclamation.” The Union president’s call for 75,000 men—seven times the force Winfield Scott had marched into the Halls of Montezuma during the Mexican War—was seen by some as evidence of a Northern determination not merely to restore the Union but to subjugate the South entirely. A member of the Third Louisiana wrote, “The sustained of the Lincoln Government sadly mistake the spirit, energy, and determination of the outraged and insulted people of the South if they suppose, for an instant, that we are to be intimidated by threats, or overawed by an appeal to arms.” There were ardent Secessionists in the regiment, of course, such as Captain Theodore Johnson, of Iberville, the regimental quartermaster, who had been a member of Louisiana’s secession convention. But there were also men like Captain David Pierson, a convention delegate who had voted against secession—one of only seventeen to do so. In a letter to his father Pierson took pains to explain why, having worked to preserve the Union, he raised a company of volunteers in Winn Parish for the Confederate army. Faced with the choice of fighting for or against the South, he chose the former. “I am not acting under any excitement whatever,” Pierson wrote, “but have resolved to go after a calm and thoughtful deliberation as to the duties, responsibilities, and dangers which I am likely to encounter in the enterprise. Nor do I go to gratify an ambition as I believe some others do, but to assist as far as is in my power in the defense of our common country and homes which is [sic] threatened with invasion and humiliation.” He was moved by a sense of community obligation as much as anything else: “I am young, able-bodied, and have a constitution that will bear me up under any hardships, and above all, there is no one left behind when I am gone to suffer for the necessities of life because of my absence. Hundreds have left their families and their infant helpless children and enlisted in their Country’s service, and am I who have none of their dependents better than they?”20

Regardless of the volunteers’ motives for enlisting, Camp Walker existed to transform them from individuals into members of disciplined military units. General Tracy established a rigorous training schedule, while Hébert, through his rigid enforcement of all rules, began to develop a reputation for exactitude, tempered by a genial manner and his obvious care for the men’s welfare. Overall, the recruits responded well to instruction, although some in the Third, experiencing the “Europeanized” culture of New Orleans for the first time, could not resist its temptations. Watson recalled that men “who had always before been strictly sober in their habits were now to be seen reeling mad with drink,” spouting obscenities and picking fights with their comrades.21

Such problems did not make Hébert’s regiment different from the three thousand other volunteers at Camp Walker, and when on May 7 a military review was held on nearby Metairie Ridge, under the eyes of Governor Moore and a great crowd of the citizenry, the colonel had reason to feel proud. By now the Third was reasonably well equipped with tents, blankets, knapsacks, and canteens. Each of the regiment’s separately raised companies wore uniforms manufactured by the folks in their hometowns. The cut and quality must have differed substantially, but apparently all of their uniforms were gray. Watson’s company, now commanded by Captain John P. Vigilini, as Tunnard had been elected major, wore large brass belt buckles emblazoned with a Louisiana pelican. As a legacy of their prewar organization, the Pelicans of Baton Rouge carried Model 1855 Springfield rifles. Some companies of the Third carried Mexican War vintage Model 1841 “Mississippi” rifles, and the rest were issued smoothbore muskets, both percussion and flintlock.22

Back in camp, training continued. As each day passed the number of sick in Camp Walker increased. Governor Moore became so alarmed that he ordered Tracy to transfer all of the units except the Third Regiment to other locations. The Third was now ready for war, and most of the men eagerly anticipated orders that would dispatch them to Virginia. But those who read the New Orleans papers would have noted increasing coverage of events in Missouri. On May 16, the day before the Third was sworn into Confederate service, the Daily Picayune reported the massacre of civilians in St. Louis on May 10 by troops under a Union officer named Nathaniel Lyon. Succeeding articles painted a portrait of a state on the verge of civil war, as both pro- and anti-Secessionists forces rushed to arms.23

It thus was not a complete surprise when orders came for the Third to proceed to Fort Smith, Arkansas, to help defend the Confederacy’s northwestern boundary. Late in the afternoon of May 20 the regiment marched from Camp Walker to Canal Street, its progress marked by “one grand oration” from thousands of men, women, and children who lined the street, balconies, and rooftops to bid them farewell. At the river, the men crowded onto four steamers and the expedition got under way at 9:00 P.M. Progress up the Mississippi was slow, for they did not reach Baton Rouge until the following evening. Word of their coming had preceded them by telegraph, and the governor and a military band were ready to greet them. The city’s own Pelican Rifles were the only troops allowed ashore, but their brief reunion with loved ones proved memorable. “The landing was packed to its utmost capacity,” one soldier recalled, and “the scene that ensued beggars all description.” When after half an hour of celebration the company reboarded and the vessels pulled away, fireworks shot up from the levee and burst over the river, bright flashes gleaming off the dark water. This was a final gift from “a large number of patriotic ladies who had collected for this purpose.”24

The boats reached Vicksburg on May 23, but after a brief halt they continued north and finally turned west into the Arkansas River. Time passed slowly and the men, crowded together without proper facilities, washed their clothing by towing it behind the boats strung on fishing lines. On May 27 they reached Little Rock, where they were immediately caught up in the Confederacy’s somewhat confused plans to defend Arkansas, secure the Indian Territory, and, if possible, assist Missouri.25

Because of the peculiar circumstances under which Arkansas left the Union, the state contributed two different types of forces to the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. Some men were enlisted in the Confederate army, while others belonged to the Arkansas State Troops, the militia guaranteed to the state by the Confederate Constitution. These must not be confused with the prewar Arkansas state militia.

Although thoroughly Southern, Arkansas in 1861 was in many ways a frontier state. It possessed only a few miles of railroad, going nowhere in particular, and not until January of that year was the state capital connected with the rest of the nation by a telegraph running to Memphis, Tennessee. Governor Henry M. Rector favored secession, and he encouraged (some would even say he instigated) the unusual events that occurred at the Federal arsenal in Little Rock on February 6. These happenings involved, among others, the Totten Light Battery, Captain William E. Woodruff Jr., commanding.26

The Woodruff family name was “a household word all over Arkansas,” thanks to the various newspaper enterprises and political activities of Woodruff’s father, William Sr., who had moved to Arkansas in 1819. The younger Woodruff, born in 1831, absorbed Democratic party politics on his father’s knee and culture from his father’s extensive library. He graduated from Kentucky’s Western Military Institute in 1852 and eventually studied law, opening a practice in Little Rock in 1859.27

When a volunteer artillery battery was organized at the state capital in 1860, Woodruff’s social position and military training ensured his election as captain. The unit was christened the Totten Light Battery in honor of William Totten, a popular local physician. The name also honored his son, Captain James Totten, who arrived in Little Rock in November 1860 with sixty-five men of the Second U.S. Artillery to garrison the previously unmanned Federal arsenal. The captain had generously assisted the Arkansans in their artillery training.28

When in late January 1861 Little Rock’s new telegraph line brought the news (false, as it later turned out) that reinforcements were on their way to the arsenal, prosecession volunteers poured into the capital. By the second week in February they numbered almost 5,000, and Governor Rector “intervened” by asking Totten to surrender before bloodshed occurred. Although the captain had dutifully prepared to defend the arsenal, he had no desire to harm the local populace, which contained many friends, much less fire on the battery bearing his family name. Failing to receive instructions from Washington, Totten announced that he would withdraw his forces to St. Louis.29

Totten had been born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, but raised in Virginia, and most people assumed that if sectional differences led to war, he would side with the South. Indeed, when the captain and his men boarded a steamer for St. Louis, an almost carnival-like atmosphere prevailed. The ladies of Little Rock even presented a sword to the departing Union commander as a token of their esteem. No one could imagine that six months hence Totten would draw that same sword against the Totten Light Battery amid the hills of southwestern Missouri.30

More irony was in the making, as events in Arkansas soon precipitated another near clash between men who would later meet in deadly earnest at Wilson’s Creek. A convention assembled in Little Rock in March to consider the state’s position on secession but adjourned without taking action. After the firing on Fort Sumter in April, it reconvened and finally took Arkansas out of the Union on May 6. But even before secession occurred, Woodruff’s battery and more than two hundred other volunteers were on the move to Fort Smith in the northwestern corner of the state, where a Federal garrison under Captain Samuel D. Sturgis guarded the border with the Indian Territory.31

Sturgis was a thirty-eight-year-old West Point graduate and native of Pennsylvania, and his garrison consisted of eighty-three men of Company E, First U.S. Cavalry. When word arrived that prosecession units were on their way upriver, he gathered as much government property as he could and decamped on the night of April 22. Although he moved west, his ultimate destination was Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. This had significant consequences for the forthcoming campaign in Missouri. It also brought Sturgis into what would be a most unhappy relationship with the Union volunteers even then organizing in Kansas.32

When Sturgis left, he was short one man, his erstwhile second-in-command, Captain James M. McIntosh. A Florida native and West Point graduate now in his mid-thirties, McIntosh ended eight years of service by tendering his resignation. Having just received word of its acceptance, McIntosh was moving downriver on April 23 when he met the Totten Light Battery and the other volunteers traveling upstream on the Lady Walton. After advising them of conditions at the fort he departed, intending to go to Richmond to seek a Confederate commission. He did join the Confederate army, but circumstances kept him in Arkansas and eventually pitted him against Sturgis at Wilson’s Creek.33

Colonel James McQueen McIntosh, Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles (Archives and Special Collections, University of Arkansas at Little Rock)

When the expedition found Fort Smith deserted, a garrison was established and Woodruff’s men, together with most of the other volunteers, returned to Little Rock. There, after the state formally left the Union and joined the Confederacy, they became enmeshed in the general scramble to prepare for war. This was not done smoothly, as Governor Rector became involved in a bizarre struggle with the secession convention. Because of complex political rivalries in Arkansas, the convention continued to meet and attempted to keep military affairs out of the governor’s hands. It set up a military board to raise forces and divided the state into two districts, assigning to command them men who were strong Unionists, barely reconciled to recent events.34 Most prewar militia units, such as the Totten Light Battery, now joined the Arkansas State Troops.

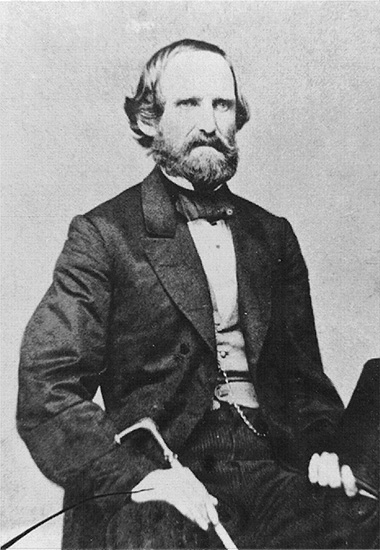

The western district (or First Division) went to Nicholas Bartlett Pearce, a thirty-eight-year-old native of Kentucky. Nicknamed “Nota Bene” Pearce by his classmates at West Point, he graduated in 1850 and served in the Seventh Infantry. He resigned in 1858 to follow business interests with his father-in-law at Osage Mills in northwestern Arkansas. As a brigadier general of Arkansas State Troops, Bart Pearce began recruiting men for the defense of the state, not the Confederacy. The state’s leading Secessionists were outraged. But whatever his own views, Pearce was well aware of the shift in public opinion. Back in April he had been listening to a political speech at a pro-Union public meeting in Bentonville when a stage coach brought the news of Lincoln’s call for volunteers to put down the rebellion. “The effect was wonderful—all was changed in a moment,” he recalled. “What! Call on the Southern people to shoot down their neighbors . . . No, never.”35

Brigadier General Nicholas Bartlett Pearce, commander of the Arkansas State Troops (National Park Service)

Pearce initially made his headquarters at Fort Smith but set up a training facility much farther north on Beatie’s Prairie, a high point between Maysville and Harmony Springs. This site was christened Camp Walker. Together with Fort Smith and the state capital, it became a rallying point for volunteers, who arrived in large numbers, in varying degrees of preparation, some seeking service with the state and others eager to join the Confederate forces. Raised at the county level by community leaders following public meetings, they represented a cross section of the state. Although motivations for enlistments varied, popular sentiment can be measured by the resolutions that were adopted by the communities sponsoring the soldiers. These almost universally portrayed the Lincoln administration as “black abolitionists” and aggressors, citing the need for Arkansas to side with the other slave states in defense of liberty. The cause was personal and the crisis urgent. For example, on accepting a flag for his regiment, one colonel stated simply: “We are going to our Northern borders to battle for the rights and sacred honor of the fair and lovely daughters of our sunny South. If the enemy cross the line and invade your homes ‘they will have to walk over our dead bodies.’”36

As in Louisiana, prewar volunteers companies in Arkansas formed a core around which larger units were organized. The Hempstead Rifles, an old militia unit commanded by John R. Gratiot, were the first to arrive at Camp Walker. Passing through Fayetteville en route, they received a flag from the local citizens. Reverend William Baxter, president of Arkansas College in Fayetteville, noted of the Hempstead Rifles that “their drill was perfect, their step and look that of veterans, their arms and uniforms all that could be desired.” From Nashville in the same county came Joseph L. Neal’s Davis Blues, sporting frock coats with eight rows of fancy trim and twenty-four buttons across the chest. In Van Buren, on the northern bank of the Arkansas River not far from Fort Smith, Captain H. Thomas Brown led the Frontier Guards, who represented “the flower of Van Buren chivalry.” The local paper boasted that these men, “the very elite of the city—‘gentlemen all,’” were the best drilled in the state. They were certainly among the better dressed. Raised back in January, they wore dark blue coats and sky blue pants that had been manufactured in Philadelphia. At the extreme of sartorial splendor, however, were the Centerpoint Rifles, under Captain John Arnold, a local physician. Thanks to the hard work of the ladies of Centerpoint, they wore matching checked shirts called hickory, adorned with five red stripes across the chest. Their blue trousers also had red stripes down the outside of each leg.37

Communities did everything they could to support “their” companies, whether they existed prior to the conflict or were newly organized. In some cases, the level of involvement was remarkable. Fort Smith, which had a population of only 1,529 in 1860, fielded five companies numbering more than eighty men each. According to the Herald and New Elevator, almost every adult male of military age in the community was under arms. A total of $2,000 was raised to support the men, and a subscription fund was started with the ambitious goal of supplying $1,000 per month to the families of the volunteers during their absence. Local women made uniforms for all five companies and for several other volunteer units that arrived in Fort Smith without them. The local paper noted proudly that “one widow lady, who makes her living by the needle, spent at least eight weeks in work for the soldiers, and that too, without pay.”38

Although Unionist sentiment was strong in northwestern Arkansas, Captain Brown of Van Buren’s Frontier Guards observed that defense was a great motivator. On May 2 he wrote his sister: “There is but one voice everywhere I have been, ‘resistance till death, to the North.’ There is a perfect upheaval of society; all classes are becoming aroused, and the merchant, the planter, the lawyer, and even doctors are enlisting.” Enthusiasm was not as nearly universal as Brown indicated, but it was marked. Joining the enlistees at Camp Walker was an even older unit, Johnson County’s Armstrong Cavalry, raised in October 1860. All seventy-three men in the unit were farmers, and all but one were Southern-born.39

The homogeneity of the Armstrong company was not unusual for units raised in rural areas. For example, the muster roll of Captain John R. Titsworth’s company from Franklin County reveals many men with the same last names, suggesting that brothers and cousins frequently joined simultaneously. The oldest member in Titsworth’s unit was Charles Ohaven, fifty-one, whose son Charles Jr. was at age eighteen among the youngest. In towns or villages, however, some ethnic diversity existed. Fort Smith’s contributions included the Fort Smith Rifles, raised by James H. Sparks, editor of the Herald and Times, and Captain John G. Reid’s Fort Smith Battery. But it was also home to a prewar unit, the nearly all-German Belle Pointe Guards. For dress parade they wore fancy frock coats with heavy gold epaulets and tall plumed shakos bearing the brass letters “BPG.”40 Van Buren had German enlistees too, among them a twenty-four-year-old Jewish immigrant from Baden named Baer who decided soldiering held more prospects than clerking at Alder’s, a local clothing store.41

Woodruff’s Totten Light Battery was not at Camp Walker, for it had returned to Fort Smith. Thanks to captured materiel and hard work, it was the best equipped and drilled unit of the Arkansas State Troops. Like many early war artillery units, the Tottens, as they called themselves, were fully armed with rifles and trained to fight as infantry if needed. But they soon gave their shoulder arms away in order to concentrate on their main function. The battery had two 6-pound bronze guns and two 12-pound howitzers, with caissons and full equipment.42

Woodruff’s artillerists now sported gray jean uniforms trimmed in red, compliments of the ladies of Little Rock. These apparently replaced a prewar uniform of unknown type. The women of Little Rock sewed uniforms not only for eight companies raised locally, but for several other units stationed there as well. Such community-level support was as important for volunteers in Arkansas as it had been for those in Louisiana. General Pearce, struggling to acquire weapons and bring order out of chaos, was fully aware of the many contributions women made. “Our lovely women were as earnest, as patriotic, as any of the stronger sex,” he recalled. He credited their “devotion and example” with “stimulating to exertion their dear ones, fathers, husbands, sons, and brothers.” Others were also grateful for the efforts women made. The Fort Smith Parallel showered praise on the town’s “patriotic ladies” for their “untiring perseverance” in equipping the local men for war. Some women were apparently not content with a supporting role. A soldier from Rocky Comfort boasted, “Our females are somewhat like the Spartan women, and wish to fight also in person.”43

At the same time that Pearce was struggling to train his men at Camp Walker and the Third Louisiana was arriving in Little Rock, another portion of the forces that would fight for the South at Wilson’s Creek was coming together in Texas. Texas contributed a single regiment of cavalry to the battle, but it also sent the state’s most famous Texas Ranger, Ben McCulloch.

Texas had left the Union on February l, 1861, reverting briefly to its status as an independent republic before joining the Confederacy. Because of the state’s geographic position, defense against Native Americans was the most pressing concern, although in the northeastern counties along the Indian Territory, slaveholders feared a sudden descent of abolitionists from Kansas. This meant a busy spring for Ben McCulloch, who along with his brother Henry and John S. “Rip” Ford, was appointed a colonel in the Army of Texas, a force established by the secession convention to meet the state’s military needs until a working government under the Confederacy was set up.44

McCulloch would command the Southern forces at Wilson’s Creek, but were it not for a twist of fate he would have died at the Alamo. Born in Rutherford County, Tennessee, in 1811 and raised in the western portion of the state, where one of the family acquaintances was Congressman David Crockett, McCulloch had no schooling past the age of fourteen. Like his sometime mentor Crockett, Ben grew up in a frontier environment where he became a master of woods lore. He worked on the Mississippi and spent some time as a trapper, venturing as far west as Santa Fe, but did little of note before following Crockett to Texas in 1836. “Following” is the key word, for McCulloch missed an appointed rendezvous with Crockett, and although he rushed to catch up, he soon fell ill. By the time he recovered, Crockett was a martyr to the cause of Texas independence. McCulloch joined Sam Houston’s army and participated in the revenge at San Jacinto on April 21, displaying in this battle the bravery and aggressiveness for which he soon became famous.45

Brigadier General Ben McCulloch, commander of the Western Army (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Whereas “Davy” Crockett’s legend as a heroic frontiersman was largely created by Whig politicians and perpetuated by popular writers after his death, Ben McCulloch was the genuine article. He was the archetype of the long rider, strong and self-reliant, keeping his own counsel. One biographer described him as “a self-contradictory blend of the Victorian gentleman who drank sparingly, never indulged in the use of tobacco, treated ladies with utmost respect, and settled his personal quarrels by the rules of the code duello, and the southwestern brawler capable of smashing a chair over the head of an antagonist in the dining room of a Washington hotel.”46

Following the Texas War for Independence McCulloch settled in Gonzales, working as a surveyor and serving in the legislature. More important, as a Texas Ranger he participated in a number of expeditions against Native Americans. When Texas was admitted to the Union in 1845, McCulloch was appointed a major general of the state militia, but he resigned to serve with Colonel John C. Hay’s regiment in the Mexican War. He fought throughout the campaigns in northern Mexico, and General Zachary Taylor credited him with gathering vital intelligence that contributed to the American victory at Buena Vista on February 23, 1847. Moreover, word of his exploits reached a national audience through the publication in 1850 of The Scouting Expeditions of McCulloch’s Texas Rangers, a laudatory work by one of his subordinates.47

By the time this book was in press, McCulloch was in California. “I am after money,” he wrote frankly to his brother Henry as he departed for the gold fields, but there was more to it than that. Despite his many accomplishments, McCulloch was approaching forty and despaired of finding a wife. His features have been described as rugged and weather-beaten, but photographs suggest a man at least as handsome as his contemporaries. Yet McCulloch considered himself so “confounded hard looking” that without wealth he would be condemned to bachelorhood, “the last thing any sensible man would wish.” Give a man money, he noted with sarcasm, and “you give him everything, at least it will answer all purposes,” for it magically “renders the possessor witty or wise” in the eyes of society.48

But in California McCulloch found neither wealth nor wife. The state’s rejection of slavery in 1850 dismayed him, for he and his family were strong supporters of that institution, and he disliked the Northerners who were flocking to the west coast. After two years as sheriff of Sacramento, he returned to Texas. For much of the next eight years he served as a Federal marshal in his adopted state. During this time he worked hard to obtain a commission as colonel of cavalry in the U.S. Army, believing that his practical experience and extensive private study of military texts outweighed the teachings of the Military Academy at West Point, an institution he despised. Yet when offered a lieutenant colonelcy in the Second Cavalry in March 1855, he refused to accept the number-two position. The episode reveals in McCulloch an inflexibility and inability to compromise that would have important consequences later on.49

An enthusiastic supporter of secession, McCulloch was instrumental in securing Federal property within Texas once the state left the Union, and he served as a commissioner to purchase additional arms. He was actually in New Orleans when he heard that Fort Sumter had been bombarded, and from there, too, he learned that he had been commissioned a Confederate brigadier general and assigned to a district “embracing the Indian Territory lying west of Arkansas and south of Kansas.” He left immediately for Fort Smith, as that post’s river communications and position made it the most logical place to gather Confederate forces. Although McCulloch’s high rank certainly reflected great honor, when the old Texas Ranger arrived at Camp Walker in early May he may have wondered whether the war would be over before he could accomplish anything in such a “backwater” region.50

McCulloch expected troops from Texas to join him as speedily as possible, but there were delays. These were caused by logistical difficulties and the geographic distances involved, not by any lack of enthusiasm on the part of the people. In eastern Texas the key figure was Elkanah Greer, who received a Confederate colonel’s commission and instructions to raise a regiment of cavalry. A native of Mississippi and a member of Jefferson Davis’s regiment during the Mexican War, Greer had been a resident of Marshall, Texas, since 1851 and was now well known throughout the Lone Star State. An ardent Democrat and a fiery Secessionist, he led the Texas branch of the Knights of the Golden Circle, an organization that sought to add new slave territory to the Union. By local standards he was part of the planter elite, possessing twelve slaves and property worth $12,000. When on May 4 Governor Edward Clark called upon “every community” to raise a company “to repel the vandals of the north,” prospective soldiers flocked to join Greer in Dallas.51

As in Louisiana and Arkansas, the companies that arrived had been raised at the community level. The Marshall Texas Republican reported an epidemic of “war fever” throughout the region. “It pervades all classes of society—young and old, male and female.” Meetings at Marshall, the seat of Harrison County, resulted in plans to organize a unit. Two thousand dollars in public funds were appropriated for its support, while handbills were printed and distributed to drum up recruits. From his pulpit Reverend T. B. Wilson urged the young men of his congregation to enlist, proclaiming: “In the name of God I say fight for such sacred rights. Fight for the principles and institutions bequeathed to you by the blood of revolutionary sires.”52

As the Marshall company began filling its ranks, it was joined by another raised at Jonesville in the northern portion of the county. The two units eventually merged, elected Thomas W. Winston captain, and adopted the name Texas Hunters. Courtesy of the women of Harrison County, they wore cadet gray uniforms and bore an elaborate silk banner, one side of which was emblazoned with the words “Texas Hunters” above a painted hunting scene; the other side was a version of the Confederate national flag. With Colt’s revolving rifles, they were probably the best-armed unit in the state at that time.53

South of Marshall, across the Sabine River in Rusk County, a company was organized at Henderson. Its ranks included a young music teacher, Douglas John Cater. Although a relatively new resident of the community, he rushed to join the “leading citizens” of his adopted town in defending Texas against the “Black Republicans.” Cater was appointed bugler, although he took along his violin so that he and another musician, Jim Armstrong, could entertain the men. The Rusk County Cavalry, as the recruits called themselves, went off to war nattily attired. Although their trousers were plain brown jeans, they wore matching black wool coats and vests and tall black boots. Cater added a white shirt and black silk cravat to his ensemble. “It looked well enough,” he recalled, “but was very hot to wear in the summer.”54

In all, ten companies assembled in Dallas, some in uniform and some in civilian clothes. Because Greer expected to assist McCulloch in defending the border region, he called his regiment the South Kansas-Texas Cavalry, but for the moment the men’s real identity lay at the company and community level. Literally emblematic of this fact were ten flags manufactured by the ladies of Dallas, bearing not only each company’s new letter designation but its “real” name as well. The Cypress Guards, Lone Star Defenders, Ed Clark Invincibles, Smith County Cavalry, Wigfall Cavalry, and Dead Shot Rangers had been raised at the villages, post offices, and county courthouses throughout eastern Texas. Local support was crucial at the beginning, and it remained so during the early part of the war. With pledges of lump sums up to $10,000, or monthly supports in the range of $200, the homefolk committed themselves to the soldiers’ welfare. This was appropriate, as these men were, the Dallas Herald boasted, the “very flower of the land—the chivalry, ‘the bone and sinew’ of the country . . . engaged in the holy cause of defending their rights and liberties.”55

Thanks to the exhaustive scholarship of Douglas Hale, more is known about the composition of Greer’s regiment than any other unit that fought at Wilson’s Creek. The men were overwhelmingly Southern by birth, but they were not average Southerners. “Considered as a whole,” Hale writes, “the officers and men of the regiment came disproportionately from the wealthier classes in their society.” The elected company captains “were men of mature years and prominent leaders in their communities.” All of them owned slaves and on average possessed more than three times the wealth of the enlisted men of the regiment. Two-thirds of the enlisted men, however, also owned slaves—almost exactly the reverse of Confederate enlisted personnel nationally. With the planter and professional classes disproportionately represented in the ranks, their educational level was high. Only 14 percent of the common soldiers came from “the ranks of the poor.” Their average age was twenty-three, but Private Nelson Walling was sixty-three and thirteen-year-old Walton Ector accompanied his father Matthew. The elder Ector was appointed regimental adjutant. His reasons for taking his son with him to war are unknown.56

Clearly the liberties these Texans gathered to defend included the right to own slaves. Indeed, they took their slaves to war with them. The record of these African American participants is almost entirely lost. Among the slaves accompanying the Texas Hunters, however, was Ned Buchanan, who not only was at Wilson’s Creek but also “served” until the end of the Civil War. He owned a farm following the conflict and attended reunions of Confederate veterans.57

Greer’s men formed many attachments with the citizens of Dallas, then a community of fewer than eight hundred people. Local merchants charged fair prices, and the women of the city gave the regiment a Confederate flag. But Greer fumed at the slow pace of organization. As his men camped in and around the town, he struggled to assemble wagonloads of supplies and hired Mexican Americans as teamsters. Many of his men had arrived without weapons, and it seemed like a promised supply from San Antonio would never appear. Meanwhile, as May ended and June began, news of events in Missouri gradually reached Texas. From the Southern point of view, the news could hardly have been more alarming.58