Chapter 3

Mark Well the Spot Where They Meet

Nathaniel Lyon did not ask permission to wage war on the state of Missouri. He did not request detailed instructions from Washington or wait for orders from the War Department. Indeed, after Lyon “tasted power,” he could no longer tolerate “anyone riding herd on him in Missouri.” He simply informed his superiors of his overall intentions and interpreted their silence as endorsement for his course of action.1 Although Lyon was apparently correct in his assumption of approval, the fact that he chose to operate in such a manner reveals much about his personality.

Lyon never intended to abide by any of the arrangements made between Harney and Price. A week before the Planters’ House meeting at which he precipitated the crisis, he informed the War Department that he feared a dual invasion of the state by Confederate forces in northwestern Arkansas and western Tennessee. To counter this, he recommended a reinforcement of Cairo, Illinois, at the strategic junction of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. Then, if reinforcements were sent to him from Kansas, Iowa, and Illinois, he would undertake a movement from St. Louis “towards the southwest.”2 Whether anyone in Washington realized that this meant Lyon would drive Missouri’s legally elected officials from the state capital and battle the militia guaranteed to Missouri’s citizens under the Bill of Rights is unknown.

The day of the Planters’ House meeting, the War Department promised Lyon 5,000 muskets and instructed him to raise as many volunteers from within Missouri as he thought necessary. Lyon now also had on hand a battery of artillery under Captain James Totten. This was Company F of the Second U.S. Artillery, but by the custom of the times it was referred to as Totten’s Battery. Reinforcements were on the way, but Lyon, characteristically, did not wait for them. He moved immediately on Jefferson City.3

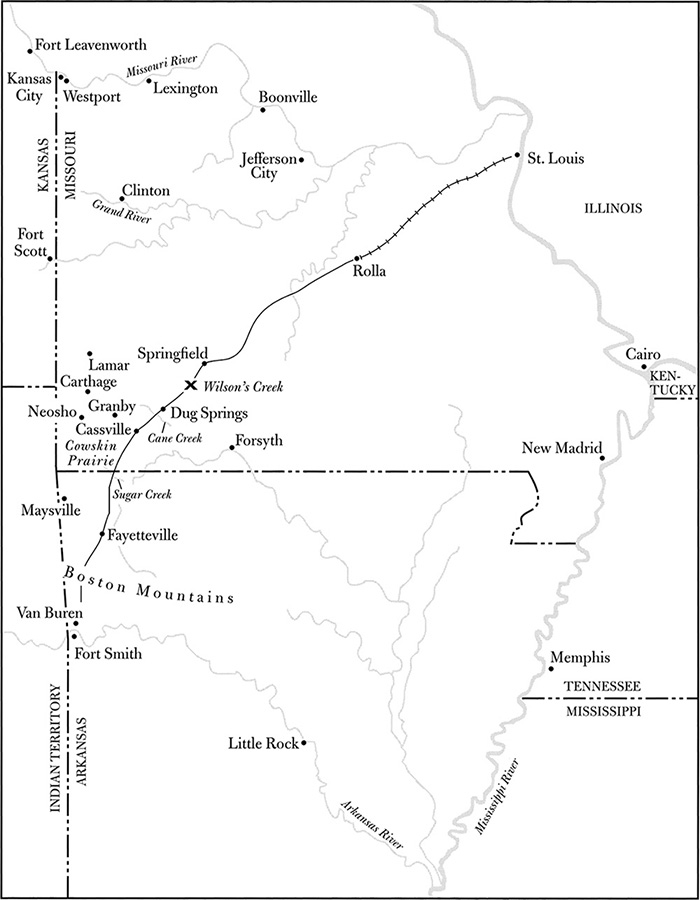

Lyon’s overall strategy was simple in concept but difficult to execute. It involved three columns operating nearly simultaneously, the first two launched from St. Louis, the third from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The first column from St. Louis would move up the Missouri River, capturing Jefferson City as the initial step in controlling the key railway and water connections in the central portion of the state. A second column would move by rail from St. Louis to Rolla, where the tracks ended, proceeding by road to Springfield in the southwestern corner of the state. The Leavenworth column would proceed southeast, uniting with the first column near Clinton, Missouri. Together they would move toward Springfield. Governor Jackson’s Missouri State Guard would either be scattered before it could organize or be trapped between the converging columns.4

Although Lyon has been hailed as the man who saved Missouri for the Union politically, most historians have underrated his military achievements. When Lyon began executing the strategy outlined above, he became the first commander in the Civil War to make strategic use of steamboats and railroads. Although the forces he eventually brought into battle at Wilson’s Creek were small compared to those engaged east of the Mississippi River, his theater of operations was vast. By the time Lyon’s forces converged on Springfield, the main column had traveled over 260 miles. A similar advance southward by Union forces from Washington, D.C., and Louisville, Kentucky, would have reached Raleigh, North Carolina, and Decatur, Alabama, respectively.

Lyon moved quickly. Requisitioning steamboats, he reached Jefferson City on June 15, only to discover that almost every member of the state government had fled the capital. Although he soon occupied the public buildings, his protection of state property did not extend to the governor’s mansion, which was systematically looted. A newspaper correspondent reported: “Sofas were overturned, carpets torn up and littered with letters and public documents. Tables, chairs, damask curtains, cigar-boxes, champaign-bottles, ink-stands, books, private letters, and family knick-knacks were scattered everywhere in chaotic confusion.”5

Eleven years earlier Lyon had demonstrated his conviction that war should mean extermination when he not only massacred an Indian tribe but also burned its village to the ground. Jefferson City contained too many loyal citizens for Lyon to destroy it, but he had no intention of protecting the property of those he considered to be traitors, not even state governors. This time, however, his quarry got away without the thorough punishment that Lyon desired. Jackson had ordered a force of some 450 of the Missouri State Guard, under Colonel John Sappington Marmaduke, to make a stand farther upriver at Boonville. Lyon’s attack with 1,700 men routed them easily, but the governor and most of the men escaped to fight another day. Barely large enough to call a skirmish, much less a battle, the incident at Boonville nevertheless received enormous press coverage throughout the North. Lyon became a hero. Cartoons were published depicting him as a lion chasing off Jackson, who was portrayed as a jackass. If the public made too much of Lyon’s exploits on the “battlefield,” the strategic significance of his victory can hardly be exaggerated, as it cemented the Federals’ control of the state’s all-important railroad and water networks.6 But to carry out the remainder of his plans, Lyon needed more troops than he had raised in St. Louis. Help would have to come from outside the state.

The Wilson’s Creek campaign

Of the reinforcements sent to Lyon, those that eventually fought at Wilson’s Creek were the First and Second Kansas Infantry, the First Iowa Infantry, a twenty-one-man detachment of the Thirteenth Illinois Infantry, and several companies of infantry, cavalry, and artillery from the Regular Army. As was the case with the Northern and Southern forces previously described, the volunteers were raised at the community level. Two units, the First Iowa and the Second Kansas, were enlisted for only ninety days. As they returned home to the accolades of their loved ones after the battle, they provide an opportunity to study the full range of the soldiers’ experiences in the 1861 campaign in Missouri.7

Granted statehood in 1846, Iowa was home to a number of largely social prewar militia companies, including the Muscatine Light Guard, the Washington Guards of Muscatine, the Mt. Pleasant Grays, and the Iowa City Dragoons. A number of relatively new units, such the Burlington Zouaves, were formed in the late 1850s in a burst of enthusiasm for volunteering that occurred after Elmer Ellsworth of New York toured the country with a colorful drill team, clad in the flashy garb of the Zouaves, Algerian soldiers serving in the French colonial armies. Leopold Matthies, a native of Bomberg, Prussia, military academy graduate, and former German army officer, put his past training and experience to work by organizing his fellow countrymen residing in Burlington into the German Rifles. Dubuque boasted the Governor’s Grays, named in honor of former governor Stephen Hempstead. Davenport, home to the Davenport Rifles since their organization in February 1857, also sponsored the Davenport Guards and the Davenport Sarsfield Guards, both formed in March 1858. These volunteer companies may have enjoyed picnics more often than target practice, but they gave the state a substantial body of men who possessed at least some military training.8

When newspapers and telegraph lines spread the news of the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Iowans reacted in the most American way possible. Between April 18 and 20 they met in their local communities to determine a course of action, responding to Lincoln’s call for volunteers and Governor Samuel J. Kirkwood’s subsequent instructions concerning Iowa’s quota. In Muscatine, for example, they gathered in an abandoned dry goods store and passed resolutions to “stand by the stars and stripes wherever they float, by land or sea.” Sixty-three men signed up to organize a company. During the early evening hours of April 18, concerned citizens in Iowa City nailed up hastily printed posters announcing a meeting to be held at the courthouse later that night. Despite the short notice, the crowd that gathered was too big for the facility. Men and women were forced to stand outside in the street, straining to catch the words of the patriotic addresses delivered by the mayor, local politicians, leading businessmen, and community clergy. When Captain Bradley Mahana of the Washington Guards appealed for volunteers to bring the city’s peacetime militia unit up to wartime strength, forty-three men rushed forward. The meeting also secured pledges of $3,000 to support the families of the volunteers. Most of this came from two local banks. Two days later an even larger meeting was held on the grounds of the local college. Governor Kirkwood, though ill, was on hand to make a speech. The Washington Guards completed their recruiting, the subscription fund reached $8,000, and steps were taken to give land bounties to those who served their ninety days honorably. In Burlington, the citizens met on April 20 and made plans to support their prewar companies. The city council pledged $1,000 to equip the volunteers more fully, and men and women formed committees to assist the soldiers and care for their families while they were absent. In Dubuque, Mt. Pleasant, and Davenport young men competed for space in the rapidly swelling prewar companies, while brand-new companies sprang up like mushrooms across the state. Ladies everywhere began rolling bandages. Meetings were held even in the smallest communities, such as Hampton, in northern Iowa, where the local paper announced the procedures for volunteering: “In every neighborhood volunteers should form into companies of seventy-eight men each. Each company will elect a Captain and two Lieutenants, who will be commissioned by the Governor. . . . Companies as soon as organized should notify the Governor and hold themselves in readiness for orders. Regiments of ten companies each may be formed, and regimental officers elected.”9

For the moment, at least, patriotism seemed to prevail over party politics. “War! war! is the all absorbing topic of conversation,” wrote a correspondent in Davenport. “Men of all parties—ignoring former party names—are rallying under the old Flag, and keeping step to the music of the Union.”10

During the remainder of April and the initial days of May, the ten companies that eventually formed the First Iowa completed their recruiting and prepared to gather at Keokuk, on the Mississippi River near the Missouri border. One company, the Governor’s Grays under Captain Frank J. Herron, contained a large number of Irish, while three units—the Burlington Rifles, the German Volunteers of Davenport, and the Wilson Guards of Dubuque—were composed exclusively of German Americans, many of whom spoke little or no English. Proportionately, more Germans volunteered for the Union than any other group of immigrants. In Iowa, the Germans’ ethnic identity was so strong that when those living in Keokuk could not raise enough men for a separate company, they went north to join the Burlington Rifles rather than merge with any of the companies native-born Americans were organizing in their city. After the First Iowa was created, the German companies tended to stick together, socializing among themselves, but they rarely encountered overt ethnic hostility. Captain Matthies of Burlington, for example, was respected throughout the regiment for his demonstrated ability, soldierly demeanor, and unfailing good humor.11

There were many foreign-born people living in Iowa in 1861, particularly in river cities such as Burlington, where one in every three adult males was German. As a voting bloc German Americans had won the state for the Republican Party in the recent national election. Their patriotism was widely praised in newspapers, which pointed out that many of them had military experience from the revolutions in Europe. Precisely how many of the First Iowa’s Germans were veterans is unknown. Captain Augustus Wentz and Lieutenant Theodore Guelich of the Davenport company took part in the Mexican War. Another member of their unit reportedly fought in nineteen battles in Europe and America. Others were identified as having experience in the German, Austrian, and Hungarian armies.12

In addition to Germans and Irish, the regiment contained men born in Canada, England, Scotland, Wales, the Netherlands, Sweden, France, Switzerland, and Norway. Besides Iowa, fourteen Northern and eight Southern states, plus the District of Columbia, were represented. At the time of their enlistment all but seventeen men were residents of Iowa. The average age was twenty-one. No analysis of their occupations exists. The Dubuque Weekly Times claimed that the Governor’s Grays was “composed largely of businessmen.” John S. Clark, a twenty-year-old who with-drew from Iowa Wesleyan University to join the Mt. Pleasant Grays, recalled after the war that the regiment contained “scholars, classical students, men of high standing in all the learned professions as well as expert artisans in all lines.” Franc B. Wilkie, a correspondent for the Dubuque Herald who accompanied the First Iowa, was more cynical or perhaps honest in his postwar reminiscence of the regiment’s personnel, writing: “They were clerks on small salaries; they were lawyers with insufficient business; they were farmer’s boys disgusted with the drudgery of the soil, and anxious to visit the wonderful world beyond them. To these were added husbands tired of domestic life, lovers disappointed in their affections, and ambitious elements who saw in the organization of men opportunities for command. Others, differing but little from the last named, scented political preferment, and joined the popular movement.”13

Although the desire to advance oneself, to escape from ordinary routine, and to experience adventure were doubtless among the motives for enlistment, there is no reason to discount the Iowans’ patriotism. State newspapers in April and May 1861 were filled with letters and editorials equating support of the Union with a sacred duty the people of the Hawk-Eye state owed both to the nation’s Revolutionary War ancestors and to the framers of the Constitution. As Earl J. Hess and James M. McPherson note in recent studies, the language of nineteenth-century patriotism may strike modern readers as flowery and pretentious, but it asserted deeply held convictions. The Davenport Daily Democrat & News predicted a titanic struggle precisely because the soldiers of both the North and South were so committed: “Each army will be composed of men who are no mercenary hirelings, but whose hearts and souls are in the work,” wrote the editor. “Mark well the spot where they meet. It will be known in history to the last generation of man.”14

There is only scant information on how the men who joined the First Iowa perceived the war or why they enlisted. Their ideas were doubtless shaped in part by what they read in the letters and editorials appearing in their hometown newspapers. These made little mention of slavery, perhaps because it was unnecessary to do so. More often, they wrote of the need to punish treason and uphold national honor. The Mt. Pleasant Home Journal spoke of resisting the attempt by “seventy-thousand negro drivers” of the South to “compel five million white men” of the North to abandon the principles of democracy. But it also referred to honor, labeling the fall of Fort Sumter a “damming blot on our national escutcheon” that “must be wiped out.” The Burlington Daily Hawk-Eye wrote, “Not the name of Lincoln, not the prestige of the administration, but the Stars and Stripes, has called together the thousands of free men now resolved to uphold the mighty interests represented by it.” When the citizens of Iowa City presented Captain Mahana of the Washington Guards with a sword, they charged him to use it “to uphold the Constitution and the laws, and vindicate the wounded honor of the nation.”15

When Horace Poole, who was originally from New England, joined the Governor’s Grays, he wrote back to his father’s newspaper in South Danvers, Massachusetts, that he sought to defend the Constitution and “our glorious Flag.” In fact, the company flags the Iowans took with them, made by hometown ladies and presented in elaborate ceremonies, said something about their reasons for enlisting. Matthies’s German Rifles carried a silk banner inscribed “We Defend the Flag of Our Adopted Land,” while the flag of the Burlington Zouaves bore the words “The Union As Our Fathers Made It.” But the best articulation of motives occurs in a set of resolutions adopted by the Washington Guards. They identified their “holy and just cause” as “the maintenance of the Constitution and Union and the enforcement of law.” They fought to preserve “the wisest political arrangement possible,” namely “a representative government with short terms of office, established and maintained by the will of majorities.” They asserted that “the will of the minority,” the South, was “entirely subversive to democratic Republicanism, and if not controlled affords us the death knell of constitutional freedom throughout the world.”16

Eugene F. Ware, who served with the Burlington Zouaves, recalled the unpopularity of abolitionists in Iowa. Some members of his company were indeed against slavery, but only because they believed it harmful to the future of free white labor, not because they felt sympathy for the slaves themselves.17 “Happy Land of Canaan,” a song of 217 verses that was wildly popular with the First Iowa, included many overtly racist lyrics, such as the following:

It’s a funny thing to me why the nigger he should be

The question everybody wants explaining.

But there’s not a single man for the nigger cares a damn,

But to send him from the happy land of Canaan.18

Given such sentiments, it is not surprising that when the regiment was on campaign and escaped slaves sought refuge in its camp, the Iowans seized them and returned them to their masters. They did, however, use free blacks as camp servants throughout the regiment’s service.19

While the First Iowa was in Missouri, the state’s numerous newspapers printed soldiers’ letters and reports from special correspondents covering almost every aspect of the unit’s participation.20 As was the case with other regiments, hometown papers focused on “their” company. The link between local communities and individual companies was particularly strong because the men expected to return home and give an account of their behavior after only three months’ service. “The community,” observes Reid Mitchell, “never entirely relinquished its power to oversee its men at war.” Community pride helped men accept a degree of discipline that would have been anathema in civilian life. It also sustained them in battle. “A man who skulked or ran faced not just ridicule from his comrades but a soiled reputation when he returned to civilian life.”21

Mitchell also notes the larger consequences of Civil War armies having their origins at the community level. After studying the Northern war effort he concludes: “[The] voluntary organization of small communities into a national army, the amalgamation of civic pride and national patriotism, serves as an example of how the volunteers imagined the Union should function. In 1861, a Union which went to war by creating a centralized army would have been unrecognizable to them. The local nature of the companies and regiments faithfully mirrored the body politic at large.”22

The Iowans enjoyed intense community support from the beginning. “Everybody, old and young, vied with one another to do honor to the young volunteers,” one soldier recalled. In Cedar Rapids, Dubuque, Davenport, Mt. Pleasant, Burlington, Iowa City, and Muscatine (the towns that contributed one or more companies to the regiment) committees of citizens raised thousands of dollars to help equip the soldiers and support their families. “Those who defend the hearthstones of our country should not be forgotten by those who have the ability,” wrote a Davenport editor. Newspapers printed the names of relief committee members, along with those of contributors and the amount of their donations. Local physicians often pledged free medical treatment for the families of recruits.23

While Governor Kirkwood struggled vainly to procure uniforms for the state’s troops, local men and women joined together to clothe the soldiers of their community. A Dubuque paper reported daily on the work of the Ladies Volunteer Labor Society, which supported the Wilson Guards. In Muscatine more than one hundred men and women put aside religious scruples to assemble on Sunday, sewing all day to have their men ready to leave the following day. “There is no Sunday in time of war,” a newspaper reporter explained. In Iowa City professional tailors, who were presumably men, worked on coats while “generous ladies” produced trousers. Many accounts mention the use of sewing machines, often giving the brand name. As each company selected its own style and colors, the results were startling. When the regiment was formally organized, the men were found to possess overshirts, hunting shirts, jackets, and frock coats in dark and light blue, gray, bluish-gray, and even black and white tweed. Pants were gray, bluish-gray, black, and pink; coats and pants were trimmed in dark and light green, dark blue, black, red, yellow, and orange.24

The Iowans obviously did not blend together in the anonymity of a common uniform, but instead, through their colorful dress, retained a sense of distinctiveness that reminded each soldier of his hometown identity. During the first week in May, the companies proceeded individually to Keokuk, where on or about May 15 they were mustered into Federal service as the First Iowa. They remained at the river city for a month, until June 13, two days after the Planters’ House meeting, when they were called into the field as reinforcements for Lyon. Throughout this period circumstances mitigated against their forming a bond at the regimental level strong enough to supplant their ties with their home communities.25

At Keokuk the companies were quartered separately in vacant buildings and only gradually, as tents became available, moved into a military camp in a grove of trees just west of the city. This process took until May 30. Although the companies drilled daily by themselves, no attempt at regimental drill appears to have been made until after arms arrived in late May. More important, thanks to the relative ease of river transportation, the companies never lost contact with home. During the rendezvous process, civilians accompanied “their” companies to Keokuk and remained for some time. As the days passed, visitors from home brought large quantities of food, ranging from staples to luxury items. These were always distributed to the community’s own soldiers, never to the men of the regiment at large, even when logistical difficulties placed the First on short rations. On June 7, for example, the Mt. Pleasant Grays received individually wrapped packages containing food and a letter from a female volunteer worker. On the day before the regiment left for Missouri, a Keokuk newspaper reported that the Muscatine Grays had just received “an immense dray load of strawberries, tobacco, cakes, and other sweetmeats from the ladies of Muscatine,” while the Burlington Rifles and the Wilson Guards “received hogsheads of potatoes from the Germans of Burlington.”26

Rivalries kept community identity alive. The Burlington Zouaves persisted in following a distinctive drill and considered themselves an elite unit. They were particularly proud of being chosen the color company of the regiment. All the other companies of the First Iowa disliked the Governor’s Grays of Dubuque intensely. Jealousy was partly the cause, for the Governor’s Grays arrived equipped with the modern rifles they had carried as a prewar unit, whereas the rest of the regiment was issued outdated smoothbore muskets. The Governor’s Grays also initially received better quarters at Keokuk as a result of the intervention of a state supreme court judge. The soldiers in the other companies believed that the Governor’s Grays looked down their noses at the rest of the regiment and accused the Grays, who wore frock coats and white gloves on dress parade, of putting on airs. A Burlington soldier reported through his hometown paper that when the Governor’s Grays schemed to replace the Zouaves as the regiment’s color company, “the Zouaves responded that they would have it over their dead bodies, and prepared to defend themselves.” Actual violence was narrowly averted on the evening of June 4, when the Governor’s Grays, assigned the duty of camp guards, chased from the parade ground at bayonet point some men who had been playing baseball or some other sport. The other companies immediately armed themselves, poured onto the field, and began threatening the Grays. The regimental commander, Colonel John Francis Bates, was forced to order everyone confined to quarters.27

In some ways Bates himself symbolized the divisions in the First Iowa, for the election of regimental officers on May 11 had been highly controversial. Long after the war, John Clark of Mt. Pleasant recalled that the men selected were Democratic politicians who neither possessed nor developed military talent. “I have always believed,” he wrote in his memoirs, “that there was an understanding between Lincoln and the governors of the northern states that the Democrats should be favored in order to secure the loyalty of that party to the Union cause.” Though Clark’s suspicions were unjustified, politics played a heavy hand in the election, despite appeals that the senior officers be selected purely on the basis of military ability.28

Speculation about the election began even before the companies reached Keokuk. Candidates for office were numerous and interest in the election, which the state adjutant general set for May 10, ran high. Three officers and two privates were appointed judges and clerks to oversee the procedure. Rather than leave things to chance, ten company captains caucused at a local hotel and announced an “official” slate of candidates. This struck some in the regiment (probably those not selected) as undemocratic, and a rival slate appeared. Then, for reasons that are unclear, the company commanders had the election delayed until May 11, a Sunday. When the ballots were counted, Bates was declared colonel, but two “opposition” candidates had also triumphed. William H. Merritt became lieutenant colonel by six votes, and Asbury B. Porter became major by two votes.29

Lieutenant Colonel William H. Merritt, First Iowa Infantry (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Charges of fraud arose immediately, based on the fact that the date of the election had been changed and on allegations that more ballots were cast than there were men in the regiment. A soldier from Burlington declared that “the low tricks of politicians” and “the ‘skull-duggery’ of the roughs” had been “successfully practiced.” Another, from Davenport, charged that “several gentlemen from a certain city” had used “every unfair means which their dishonest hearts could suggest to bring about the election of the present officers.” Officers from one of the Muscatine companies, the two Burlington companies, the Dubuque German company, and the Davenport company petitioned the adjutant general to declare the election illegal, but it was allowed to stand. Indeed, the somewhat confused evidence available suggests that what really happened was that by voting as a bloc for favorite sons, some of the companies canceled out their influence, thereby producing unanticipated results.30

The Davenport Daily Democrat & News referred to the regiment sarcastically as the “First Dubuque,” because Bates, Merritt, and George W. Waldron, who was appointed adjutant, had all been associated with that city. But one must not exaggerate the problems within the First Iowa, as the majority of the men apparently accepted Bates without too much rancor. A native of Utica, New York, who had raised himself from poverty by continuous hard work, Bates had been a newspaperman, bookkeeper, mercantile agent, land broker, and insurance salesman before establishing himself in Iowa as a county-level politician. He was clerk of the district court for Dubuque County when the war broke out.31

Meanwhile, some forces drew the regiment together rather than apart. Prayer meetings, which crossed company lines, enjoyed substantial attendance. On rainy days there were impromptu stag dances, fiddlers in the regiment playing “The Arkansas Traveller” and “Old Dan Tucker.” The more refined could listen to Wunderlich’s Brass Band of Dubuque, which joined the regiment in late May. The Iowans paraded as a unit in elaborate ceremonies marking the death of Stephen A. Douglas, Illinois senator and former presidential candidate. The men of the First Iowa were also brought together by adversity, particularly the failure of the state government to supply adequate arms and accoutrements in a speedy fashion or pay them for their brief period in state service before their Federal muster. Then there was growing tension and joint frustration as the Iowans learned of the exciting events in Missouri and itched to cross the border to take on the “secesh.”32

Also, at least initially, there were mutual complaints about conditions in Keokuk and the manner in which local merchants seemed bent on making profits off of patriotism. Most soldiers considered the town, which they completely overran, to be primitive. It had no telegraph service and the delivery of mail was slow. Gradually, however, relations between the town and the soldiers changed. In late May the ladies of Keokuk sponsored an enormous picnic for the volunteers on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi. “The tables,” a soldier recalled, “were decked with flowers and groaned under the good and fat of the land; they formed two vast hollow squares, enclosing in the centre of each a brilliant gathering of the beauty of Keokuk, who with gracious smiles prepared themselves to wait on us.” Entertainment included a performance by young Leonidas Fowler, a company drummer in the Muscatine Volunteers, who pretended to be an African American delivering a speech advocating woman’s rights. This was—at least according to white male observers—a crowd pleaser.33

The day ended with an unusual ceremony. Two of the German companies marched to the nearby home of Julius Benecke, a friend of Captain Augustus Wentz of Davenport. Benecke’s six-month-old son, Garibaldi, had been baptized the previous day. Now on the shaded lawn the companies formed a circle around the father, family, and guests. Captain Matthies wrapped himself and the child in the Stars and Stripes, while Lieutenant Theodore Guelich, the regimental quartermaster, dedicated the child “to the Goddess of Liberty; to the defense of the liberty of the country it was born in, and that of all oppressed humanity.” The two hundred soldiers who were present signed a document witnessing this second, political baptism.34

The First Iowa left Keokuk suddenly, with little ceremony. Around 12:00 A.M. on June 13 Bates received orders to move his men by steamer to Hannibal, Missouri. He sounded reveille at 4:00 A.M., and as word spread of the regiment’s destination cheers rose up from tent after tent. But breaking camp took all day, and it was 6:00 P.M. when the regiment marched down to the levee as Wunderlich’s bandsmen played “Dixie.” Although in light marching order, as they boarded the Jennie Deans their baggage included two canines, a Newfoundland named “Union” and a mongrel christened “Lize.” They left behind a third mascot, an eagle that had been presented to them by the state legislature. Their only trepidation about the possibility of facing the enemy concerned their ponderous smoothbore muskets. Flintlocks manufactured in the 1820s and converted to percussion three decades later, they were the oldest type weapons that the government had held in storage. “If fire-arms had been in use at Noah’s time,” one soldier joked, “ours must have been the identical weapons that sentinels stood duty with over his collection of wild animals.”35

When the First Iowa landed at Hannibal around 1:00 A.M. on June 14, they found that the Secessionists had fled and Union Home Guards were firmly in control. Although some of the Iowans referred to all Missourians as “pukes” and immediately set out souvenir hunting, others were pleased by the cordial welcome accorded them by the Union ladies of the town. The regiment was soon dispersed, some companies remaining in Hannibal to watch over government supplies, while others guarded nearby railroad bridges and depots. On the fifteenth it reassembled at Macon City, where former typographers in the regiment took over an abandoned “rebel” printing press to produce a camp newspaper, Our Whole Union. This was edited by Franc Wilkie, the civilian correspondent for the Dubuque Herald, whom some believed accompanied the regiment primarily to promote the reputation of Colonel Bates. The next day the Iowans traveled by rail to Renick, then proceeded west on foot, commandeering supplies and wagons along the way. While en route they returned six escaped slaves to their masters, as noted earlier. A soldier whose letters appeared regularly in the Davenport Daily Democrat & News assured his hometown folk that the First Regiment had no interest in “stealing negroes,” although in a second incident they merely whipped an escaped slave out of their camp rather than turn him over to the authorities. On June 20 the Iowans joined Lyon’s growing force at Boonville, taking up quarters on two steamboats docked at the bank of the Missouri River. Like all new soldiers, they found their first march fatiguing, but they were pleased to be with Lyon, whose reputation for swift, decisive action met their approval.36

Opinions differed sharply on the performance of the First Iowa’s commander during the initial phase of the campaign, including the stay at Boonville while Lyon struggled to assemble a logistical support system. A Muscatine soldier wrote that Bates had “won praise from all quarters for his coolness, courage, and his good care of his men.” Another soldier from the same city concluded that “Col. Bates has gained very much in favor with his men during this march. He evinced an anxiety for the comfort of his men which endeared him to them, and he assumes a respectful independence in the presence of his superiors which the citizen soldier likes to see.” But a soldier from Iowa City reached different conclusions, perhaps because he had seen Bates join enlisted men in the looting of private property, grabbing a hat and a pair of boots from a Missouri country store. He wrote that Bates “has not a redeeming quality, and therefore not even the correspondent which he has hired to puff him can find anything to say of him. . . . As an officer he is the laughing stock of everybody, from Gen. Lyon down to the servants, and the vain fool thinks he is popular.”37

One thing the Iowans could agree on was that their fancy uniforms, the product of so many hours of hard work by their loved ones back home, did not stand up well to the rigors of campaigning. A Davenport soldier described his company’s worn-out trousers as “really indecent.” One of the Burlington Zouaves stated that “foraging parties have been out for pants” as some men had “only their drawers.” He joked about the prospect of using fig leaves in the near future. Wilkie informed Dubuque readers that the regiment was so shabby that it resembled “a crowd of vagabonds chased from civilization.” More important from a strictly military point of view, many of the men were now barefooted, their shoes having worn out. This severely impeded their ability to perform their duties. But despite these problems, morale remained high. The Iowans’ most fervent complaints concerned the constant postponements in starting after Governor Jackson and General Price.38

Lyon was even more eager to get at the enemy. His goal was to move overland against the Missouri State Guard with his assembled force of 2,400 men. This was not a large military body by later war standards, but the logistical aspects of Lyon’s operations were highly demanding. Reserve ammunition, tents, and camp equipage had to travel by wagon. Although the soldiers marched, each man required 3 pounds of food daily; anything less would sap his strength rapidly. Moreover, Lyon’s force also included more than 200 horses, many of them belonging to the artillery. Regulations specified that each horse should receive 12 pounds of grain daily (10 pounds for mules), supplemented by an additional 14 pounds of fodder or hay per day obtained by foraging. Consequently, Lyon needed to establish a continuous supply line, anchored on the Missouri River, capable of providing his men and animals with approximately 9,600 pounds of food and grain every day. In addition, to keep his horses fit he needed to collect every day from local sources en route 2,800 pounds of hay.39

Setting June 26 as his departure date, Lyon began purchasing or impressing wagons, horses, mules, and oxen across central Missouri. Time was of the essence, as he had already ordered Major Samuel Sturgis at Fort Leavenworth to meet him at Clinton, Missouri, with his Regulars and Kansas volunteers. It would not do for punishment to be delayed.40