Chapter 5

Nothing Was Clear Cut—It Was Simply Missouri

Some of Nathaniel Lyon’s men were already on the road to battle, for his operations since the skirmish at Boonville on June 17 included major accomplishments. Although his own column stalled at the Missouri River for a considerable time, the column he dispatched from St. Louis under Captain Thomas W. Sweeny was able to move swiftly, thanks to better communications provided by the railroad as far as Rolla. In a continuation of the unorthodox events in Missouri, the forty-one-year-old Sweeny had been “elected” a brigadier general by the Missouri Union volunteers. As these regiments still had no legal standing under state or federal law, the Missourians could vote anyone whatever rank they pleased. The War Department never recognized the title, however. Even the puppet government the Federals eventually established in Jefferson City did not allow generals in the state forces to be elected.1

Colonel Franz Sigel led the vanguard of Sweeny’s column with nine companies of his own regiment, the Third Missouri, seven companies of the Fifth Missouri under Colonel Charles E. Salomon, and two batteries of artillery, each with four guns. Sigel left St. Louis on June 13, reaching Rolla quickly by rail. From there he began moving on foot to Springfield, hoping to cut off the retreat of the Missouri State Guardsmen whom, he learned, Lyon had defeated at Boonville. The track followed by Sigel’s small brigade was commonly called the Springfield Road by travelers heading west. Some veterans in their memoirs confused its name with that of the Telegraph or Wire Road (so called because the wire-strung poles lining it were a relatively unusual sight in that day and time), which linked Springfield with Jefferson City to the north, and Fayetteville, Arkansas, to the south.2

Sigel reached Springfield on June 24. Although thoroughly drenched by a recent downpour, his men proudly marched into town, preceded by a brass band. Because the majority of people in Springfield favored the Union, the soldiers felt welcome, but the local citizenry could not have been impressed by the physical appearance of these representatives of the Federal government. Private John Buegel recalled the tattered condition of the Third Missouri. “The majority of our regiment was in deplorable condition,” he wrote. “We resembled a rabble more than soldiers. . . . Some had no trousers any more. In place of trousers they had slipped on sacks. Others had no shoes or boots any more, and were walking on the uppers or going barefooted. Still others had no hats or caps and used flour sacks for head covering.” Otto Lademann, a private in the same unit, also noted their poor condition:

Our equipment for field service was a very poor one. We had no blankets, no knapsacks, no great coats, and barely any camp and garrison equipage. Our whole outfit consisted of an uncovered tin canteen and white sheeting haversack, rotten white belts, condemned since the Mexican War, and cartridge boxes made by contract—flat, shaped like cigar boxes, without tin racks to hold the cartridges in place. Consequently, in a week’s marching you had your cartridge box full of loose powder and bullets tied to the paper cases. Each company possessed one-half dozen Sibley tents and the same number of camp kettles and mess pans.3

After making his headquarters at the Bailey House hotel, Sigel immediately began confiscating wagons, horses, and mules. Although such actions were essential to the success of his operations, a member of Backof’s Missouri Light Artillery recalled their consequences. He wrote: “It would seem that at Springfield General Sigel either ordered or permitted his command to seize horses and other property from the Secessionists in that region for the benefit of the Government. The execution of such an order was well calculated to raise strange and confused notions of property in the minds of an ill disciplined Army of three month Volunteers. Nor were these confused notions at all cleared up or corrected by the conduct of several of the officers of these volunteers.” In fact, many of the officers simply stole local horses and sold them at the expiration of their service.4

Troops viewing the seat of Greene County for the first time estimated its population to be between 1,500 and 2,500. Their reactions to it differed considerably. One soldier, while praising the surrounding agricultural region, wrote his family that “Springfield is yet what we term a ‘one horse’ town.” But another Northerner, who obviously considered himself to be deep in an alien land, described it as “decidedly the most New England-like town I have seen since I left America.” Thomas W. Knox, a journalist for the New York Herald who arrived shortly after Sigel’s men marched into the town square, left a more objective, penetrating analysis in his memoirs: “Springfield is the largest town in Southwest Missouri, and has a fine situation. Before the war it was a place of considerable importance, as it controlled the trade of the large region around it. . . . Considered in a military light, Springfield was the key to that portion of the State. A large number of public roads center at that point. Their direction is such that the possession of the town by either army would control any near position of an adversary of equal or inferior strength.”5

When Knox checked into a local hotel, he was surprised to find but one sheet on the bed. The porter who escorted him to the room explained: “People here use only one sheet. Down in St. Louis you folks want two sheets, but in this part of the country we ain’t so nice.” Knox was known for his sarcasm.6 Despite his allegations of provincialism, Springfield was a substantial, prosperous community. The town boasted the Western Commercial College, which taught bookkeeping, and the Springfield Academy, a coeducational facility whose curriculum included Latin, Greek, anatomy, and physiology. Professor Charles Carlton, who headed the academy, was a native of Britain and an ordained minister. Unlike most teachers of his day, he emphasized the development of his students’ analytic ability rather than rote learning. Springfield was home to several banks, including a branch of the Missouri State Bank, and a number of large mercantile establishments where patrons could buy furniture, clothing, dry goods, and general merchandise. A music store offered lessons, music books, pianos, and organs, together with all sorts of stringed instruments. There was a nursery featuring a wide variety of fruit trees, bushes, shrubbery, and flowers. Druggists, watchmakers, and cobblers competed for business. Grocers offered, among other things, mackerel, herring, oysters, and canned peaches. There were both saloons and a Temperance Hall on the town square. Springfield residents could have their photographs made, buy a plow or kitchen stove, or have a carriage built. They could also purchase slaves.7

Most residents of Springfield and the surrounding region were strong Unionists. Meetings were held in Greene and adjacent Christian County denouncing the creation of the Missouri State Guard and pledging resistance if conscription was attempted. The leading figure was Congressman John S. Phelps, of Springfield, who was instrumental in organizing a Home Guard. The town did have a substantial number of Secessionists, as well as many who may not have endorsed secession but denounced Lyon’s overthrow of the legal state government. Professor Carlton, for example, favored disunion, and prosecession meetings were held in Springfield until mid-June. When Unionists led by S. H. “Pony” Boyd tried to break up a gathering at the courthouse on June n, the most prominent Secessionist speaker, John W. Payne, kicked Boyd down the courthouse steps. The news of Sigel’s approach, however, produced a stream of hasty departures. The Secessionists’ fears were justified. For despite his lack of authority, one of Sigel’s first actions was to arrest enough people on suspicion of disloyalty to fill the local jail.8

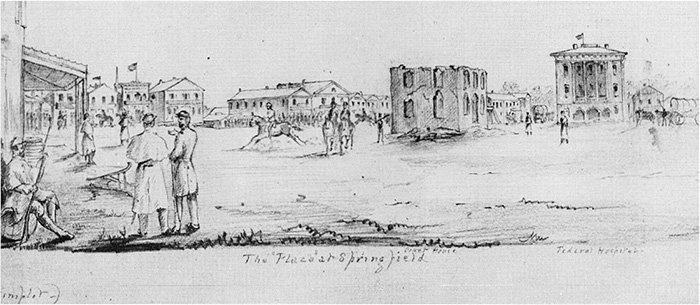

A drawing by Alexander Simplot of the plaza or public square in Springfield, Missouri (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

The day before Sigel entered Springfield, Sweeny switched his headquarters from St. Louis to Rolla, where he began building up a substantial supply depot. He continued to funnel men toward Springfield but kept some in Rolla to guard the rail head. Newly arrived troops included Colonel John B. Wyman’s Thirteenth Illinois Infantry. Organized in May at Camp Dement in Dixon for three years’ service, the men of the Thirteenth were clad in gray uniforms and indifferently armed. With companies raised in Dixon, Amboy, Rock Island, Sandwich, Sycamore, Morrison, Aurora, Chicago, and Naperville, they possessed the same close community identification as other volunteers. “We called ourselves ‘one thousand strong,’” a regimental historian recalled. “But was it not true that one half our strength was never seen in either camp or the battlefield. It was found in the homes and hearts left behind.” When Sweeny needed guards for a supply train he was sending to Springfield, Wyman drew two men from each of the regiment’s ten companies and placed them under the command of Lieutenant James Beardsley. The wagons reached Springfield in early August. The bulk of the regiment remained in Rolla, but the twenty-one men who found themselves in Springfield took part in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek.9

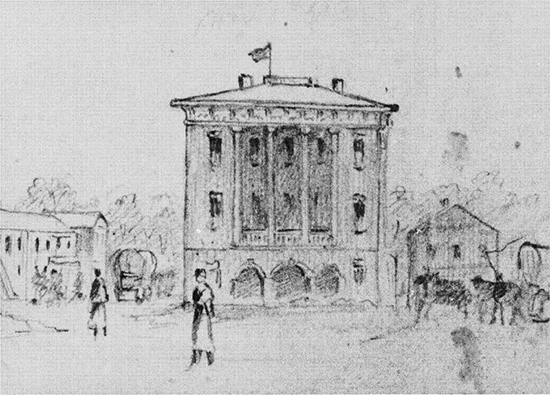

Detail from Simplot’s drawing of the Greene County Court House, used as a hospital before and after the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Sigel, meanwhile, had moved west of Springfield, occupying the villages of Mt. Vernon, Neosho, and Sarcoxie. Having heard rumors (which proved false) of another battle between Lyon and the Missouri State Guard, he dutifully dispatched scouts northward. Before these reported back, Sigel received exciting intelligence. Sterling Price, who had preceded Missouri’s fleeing governor in order to raise troops in the southwestern portion of the state, was only a few miles south of Neosho at Poole’s Prairie, and he had only seven hundred to eight hundred men. The bulk of the State Guard, under Jackson’s overall command, had been retreating slowly southward ever since Boonville, steadily gathering recruits. Sigel learned that it was now camped near Lamar. As Lamar was twenty miles north of Sarcoxie, this meant that Sigel’s dispersed units were in between his enemies. Even though the governor’s force reportedly outnumbered him substantially, Sigel decided to concentrate his men, to attack first Price and then Jackson before they could unite.10

Although this ambitious plan revealed in Sigel a willingness to take dangerous risks, such risks, combined with aggressive action, were arguably necessary if Lyon’s grand strategy was to succeed. But events did not turn out as Sigel envisioned. He learned almost immediately that Price’s force had decamped southward, heading toward the Arkansas line. Rather than follow the smaller force he decided to concentrate against Jackson, who was the greater threat. Unfortunately, he boasted of his intentions in the presence of civilians who were Southern sympathizers, and they quickly carried warning to the Missouri governor.11

Claiborne Jackson had discovered that it was one thing to create a Missouri State Guard by an act of the legislature but quite another to translate such plans into an effective field force. Following his meeting with Lyon at the Planters’ House, the governor issued an appeal for 50,000 volunteers “to rally under the flag of the State, for the protection of their endangered homes and firesides, and for the defense of their most sacred rights and dearest liberties.” But he and Sterling Price were hampered by numerous difficulties, not the least of which was Lyon’s immediate seizure of Missouri’s railways and central river network. This robbed them of precious time and the resources of the most prosperous and populous areas of the state.12

Price was not present at the Boonville skirmish, having proceeded to Lexington to organize troops to repel an expected invasion from Kansas. Lyon’s occupation of Jefferson City and victory at Boonville left the newly appointed State Guard commander no choice but to abandon central Missouri and withdraw to the southwest. There he could rally the citizens loyal to the state and appeal for help to Ben McCulloch, who was known to be commanding Confederate forces in northwestern Arkansas. Price was also hampered by a recurrent illness. He therefore left Brigadier Generals William Y. Slack and James S. Rains to assemble their divisions near Lexington and move south with Governor Jackson as quickly as possible. Riding toward the southern border with his staff, Price did gather some forces along the way, and rendezvous camps were established at Houston, seventy miles east of Springfield, and Cassville, fifty miles southwest of Springfield.13

Because sentiment in Missouri was deeply divided, the men who joined the State Guard may not have enjoyed as high a degree of community support as the soldiers from other states did, but it was nevertheless strong. Since the Guard was organized along geographic lines, each volunteer company, whether infantry, cavalry, or artillery, was assigned to a numbered unit. But those who fought at Wilson’s Creek rarely referred to themselves as members, for example, of the First Regiment, Seventh Division; they were Wingo’s Regiment of McBride’s Division. Moreover, like their fellow soldiers North and South, their identity lay primarily at the company level. The names they chose for themselves demonstrated links to their home communities and their leaders. Examples include Captain F. M. McKenzie’s Clark Township Southern Guards, Captain John S. Marmaduke’s Saline County Jackson Guards, Captain George Vaughn’s Osceola Infantry, and Captain Joseph O. Shelby’s Lafayette County Mounted Rifles.14

Yet the average Missouri State Guard company is hard to typify. Some numbered around one hundred, but many others entered the field only days after their initial organization and never recruited up to strength. Consequently, the Guard had an even greater surplus of officers than most volunteer organizations. Parsons’s Division represents an extreme case. Quartermaster records indicate that between the time of its organization and the Battle of Wilson’s Creek supplies were issued to thirty-five separate companies, each commanded by a captain. These included the Henry County Rangers, the Morgan Rifles, the Miami Guards, the Columbia Grays, the Osage Tigers, and Guibor’s Missouri Light Artillery. Yet Parsons’s “division” fielded between 523 and 601 men at Wilson’s Creek. If all thirty-five companies were present at the battle, and apparently they were, each company averaged only 15 to 17 men.15

One of Price’s first acts as commander of the State Guard had been to instruct his men to carry a blue banner, measuring four by five feet, bearing the Missouri coat of arms in gold. These flags were presumably manufactured by the women of each company’s hometown. But as most units departed for service soon after their formation, the sort of public flag presentation ceremonies that cemented company and community ties for other soldiers did not occur as often for members of the State Guard. Distinctive uniforms, another important community tie, were also largely absent. When prewar units like the Independence Grays or the Washington Blues of St. Louis joined the State Guard, they retained their old militia uniforms. But if few of the newly raised companies had matching outfits it was certainly not from community indifference. In a short space of time the women of Warsaw managed to clothe two State Guard companies and sew them a flag. One company wore blue, the other gray, the colors having yet to take on any political significance. Although a full uniform was doubtless planned, one volunteer company from Bolivar had only matching pants—brown jeans with red calico stripes down the outside seams. Several companies designating themselves “Rangers” were quite fancifully uniformed. Those from Plattin wore red caps and shirts with gray pants, while the men of Moniteau sported gray shirts, gray pants, and water repellent oil-cloth caps. DeKalb County sent its mounted company to war in gray hunting shirts and caps, and black trousers with yellow stripes, to mark their cavalry service. The LaGrange Guards also had gray caps and shirts, but trimmed in blue, and their pants were white with black stripes. But for style none could beat the Polk County Rangers, who adopted a uniform of baggy red Zouave trousers and short gray jackets. Nevertheless, probably no more than 15 percent of the State Guard wore uniforms made by their home folk at the onset of the war. Information about them is scare and often obtuse. A typical reference, drawn from the Glasgow Weekly Times, states simply that most of the officers and men in companies raised in Jackson, Clay, and Carroll Counties were “handsomely uniformed,” without giving further details.16

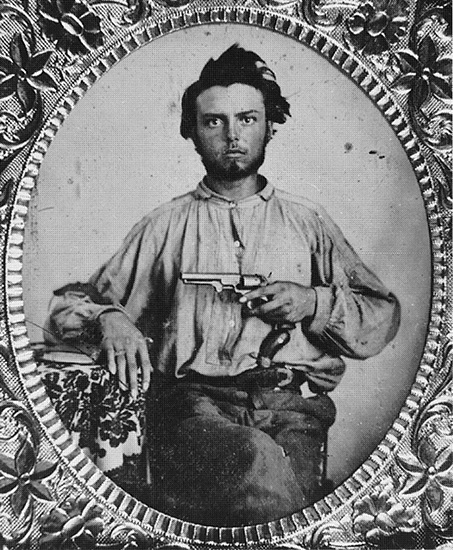

Private Henderson Duvall, Missouri State Guard (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

No social analysis of the State Guard exists. Muster rolls are incomplete and often fail to give full information about the recruits’ backgrounds. It was “a delightfully informal army, which rarely bothered with paperwork. Even when it did, because of its limited resources and habit of being self-sufficient, the morning muster-rolls were likely to be used in the evening as cartridge paper.”17

Questions about the composition and character of the State Guard cannot be answered with great precision. In 1866, however, Southern journalist and historian Edward Pollard described it thus: “It was a heterogeneous mixture of all human compounds, and represented every condition of Western life. There were the old and the young, the rich and poor, the high and low, the grave and gay, the planter and laborer, the farmer and clerk, the hunter and boatman, the merchant and woodsman.” As was the case in other states, some veterans left impressions of their comrades. James E. Payne described the volunteers from Cass, Johnson, Lafayette, and Jackson Counties in west-central Missouri as “principally farmers, though quite an important minority represented other walks in life. There was a sprinkling of merchants and merchant’s clerks, mechanics, lawyers, doctors, and laborers.” He also identified plainsmen, Indian fighters, Mexican War veterans, and filibustered associated with William Walker’s failed Nicaraguan ventures.18

As an admittedly arbitrary sample, a hospital register kept between July 5 and August 10, gives details on over one hundred patients from four of the five divisions present at Wilson’s Creek. In this sample, the youngest soldier was sixteen, the oldest was fifty-three, and the average age twenty-four. Of the half that can be identified by nativity, 30 percent were born in Missouri. Alabama, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia contributed 32 percent, while only 8 percent were from the North. Foreigners, all but two of them Irish, made up another 30 percent. The Irish came from Colonel Joseph M. Kelly’s largely Irish prewar militia company of St. Louis. Occupations included baker, blacksmith, boatman, bookkeeper, cabinetmaker, carpenter, clerk, grocer, merchant, miner, shoemaker, stonecutter, teacher, and teamster. The largest categories, however, were farmer (45 percent of those identified) and common laborer (9 percent).19

The Missouri State Guard made no provisions for mail service during the first months of its existence. Because of Lyon’s swift action, many of the Guard’s soldiers were from locations behind enemy lines. They were unable to write letters to their home folk and hometown newspapers chronicling their trials and tribulations as newly enlisted soldiers in the same manner that soldiers from other states did. But if information comes largely from postwar reminiscences, these reveal similar experiences. One of the first and greatest challenges facing those who wanted to join the Guard was simply locating it.

Joseph A. Mudd’s journey is one example of the confused conditions many of the enlistees faced. He was in St. Louis when he learned that Lyon had declared war on Missouri. To reach his home in Millwood, a village almost sixty miles to the northwest, he took a train as far as Wentzville. The same train carried two companies of German American Unionists from Colonel B. Gratz Brown’s Fourth Missouri Infantry. They were heading up the rail line to act as bridge guards. Mudd examined the arms and equipment of these new enemies carefully before leaving the train. Once home, he joined a company being raised by John Q. Burbridge in the nearby village of Louisiana. Soon more than two hundred men from both infantry and cavalry companies had assembled in the area. Many were armed with old muskets that Burbridge and other Secessionists had taken from the Missouri Depot near Liberty in April.20

Their march southwest to join Governor Jackson “was a triumph,” Mudd recalled. Units from the counties they traversed joined the column, swelling its ranks to almost one thousand. After slipping across the Missouri River, they marched for ten days on short rations to reach a State Guard camp just south of the Osage. Continuing on, they arrived at the main rendezvous, Camp Lamar, near the village of Lamar, in early July. There Mudd’s company became part of the division-in-exile being organized by Brigadier General John B. Clark Sr. The infantry companies were consolidated into a single regiment, 270 strong, which elected Burbridge colonel. The division’s 273 mounted men, likewise consolidated, were led by Colonel James Patrick Major, a West Point graduate who had resigned his lieutenancy in the Second U.S. Cavalry only ten weeks earlier.21

Henry Guibor had an even rougher journey. A thirty-eight-year-old native of St. Louis who initially practiced the carpenter’s trade, he saw military service in the Mexican War and was active in border raids against Kansans in the 1850s. He was deputy marshal for the criminal court in St. Louis when, as commander of a battery of militia artillery, he was captured at Camp Jackson. Guibor was released after swearing not to take up arms against the Federal government, but like other parolees he dismissed that oath on the grounds that it had been forced on him at gunpoint by a man who had no authority or legal basis for demanding it. Nevertheless, Guibor remained neutral, looking after his widowed mother, until friends warned him that he was about to be arrested on suspicion of treason. Obviously civil courts could offer no protection for anyone who provoked Blair or Lyon. So together with William P. Barlow, a friend and fellow artillerist who also feared arrest, Guibor fled the city on horseback on June 13, heading for Jefferson City to join Price.22

Avoiding Unionist Home Guards who were scouting in the area, they approached the state capital only to find it already in Lyon’s hands. Told that Price was in Versailles, they rode to that village and were promptly arrested by the local “Committee of Public Safety” on suspicion of being spies working for Lyon. They eventually convinced the leader of the State Guard company being organized there that they were loyal Missourians and were released to continue their search for Price. At Warsaw they were again arrested as spies. Price was not there, but when Governor Jackson arrived with a column of troops, one of his staff officers recognized Guibor. Promptly released, he was eventually given command of a battery consisting of four Mexican War vintage six-pound guns taken from the Missouri Depot. Officially designated the First Light Artillery Battery, Parsons’s Division, like many batteries it was more often called after its commander: Guibor’s Battery. Its personnel were mostly St. Louis Irishmen.23

Some Missourians were simply caught up in the flow of events. Daniel H. McIntyre, a senior only days short of graduation from Westminster College in Fulton, was eating lunch at the school when he and a friend received an urgent message to go to the town square. Leaving their textbooks open and their meal unfinished, they hurried out to find groups of men drilling in the streets. “When we got there we found we’d been elected officers,” McIntyre recalled. “We moved on to join General Price and never returned to college.”24

Henry M. Cheavens was a thirty-one-year-old schoolteacher in Boone County. Although born in Philadelphia, he had been raised in Missouri. Educated at Yale and Amherst, he taught in Illinois and Minnesota before returning to his adopted state. The account he wrote a few days after being wounded at Wilson’s Creek gives no explanation for his decision to join the State Guard, but it details his experiences vividly. Shortly after the fight at Boonville, Cheavens joined a group of eighty horsemen trying to reach Jackson’s army. His military kit consisted of a white blanket, a Mississippi rifle, and a bowie knife. He soon lost not only the blanket but his coat as well and broke his glasses. But unlike some of his comrades, he never turned back. Dodging various Unionist Home Guard patrols as they moved south, the riders brushed past the First Iowa, which was then heading west. “We received the acclamations of the people, who seemed rejoiced to see us,” Cheavens wrote, but the would-be soldiers took care to obtain local guides and whenever possible stopped only at the farms of known Secessionists. Somewhere north of the Osage River they finally located the divisions of Generals Rains and Slack and accompanied them thereafter. The pace was hard and their route sometimes confused, as Cheavens wrote of a long countermarch. As rain turned the roads to muck, “men fell from their horses with fatigue.” When time allowed, he worked to sew a tent for himself and his friends. Finally, on July 3, they reached Camp Lamar, where troops from Parsons’s and Clark’s Divisions were waiting. Cheavens’s horse was so worn out that he traded it for a draft animal, but for him the trip ended on a happy note. The quartermaster issued him a new pair of pants, and a Major Bell recommended snakeroot for his diarrhea. It worked.25

Virginia native Edgar Asbury provides another example. Asbury moved to Missouri in 1857 and opened a law practice in Houston. A “strong secessionist,” he served in the state convention and was in Jefferson City when Governor Jackson returned to the capital following the Planters’ House meeting with Lyon. Jackson asked Asbury to escort three wagons loaded with gunpowder to safety in the southern part of the state and to deliver a State Guard general’s commission to Judge James H. McBride in Greene County.26

The trip south was a nightmare. Secrecy and speed were vital, so in addition to the civilian teamsters, Asbury took only two men, Wood Rogers and W. H. H. Thomas, with him to guard the precious cargo. The powder was stored in a variety of containers in the wagons, and the “rough and stony flint roads” they traveled “bursted and broke the packages so that it was constantly streaming and leaking the powder along the road.” Fearing an explosion, Rogers and Thomas deserted, but Asbury saw the mission through to its end, although, he recalled, “my hair literally stood out straight on ends.”27

McBride appointed Asbury a lieutenant colonel and aide-de-camp on his staff and promptly gave him another assignment: to deliver State Guard commissions to loyal Missourians in Springfield. This was “a very difficult and hazardous undertaking,” as Unionists were firmly in control there. Asbury again accomplished his mission—by sneaking into town at dawn. Before he could leave, he met a former acquaintance, Mordecai Oliver, who was now a major in the local Union Home Guard company. When Oliver asked about his business in town, Asbury “told him a great, big lie.” Indeed, he damned Secessionists so thoroughly that Oliver invited him to dinner later that day. “He had a very pleasant family, two handsome daughters among the rest,” Asbury later wrote, “but I decided it was best for me to get out of that place.” Instead of keeping his appointment with Oliver, he rode to Houston, where a rendezvous camp for the men of McBride’s Division had been established. After almost a month of training and organization there, they received orders to join Price at Cassville. By that time so much of southwestern Missouri was in Union hands that they crossed into Arkansas before moving west, approaching Price’s camp from the south.28

Finally, Colonel Joseph M. Kelly’s Washington Blues illustrate the connections between prewar militia units and those of the Missouri State Guard. They were formed in 1857 as an offshoot of the St. Louis Washington Guards. Although the Blues were Irish, most belonged to a local temperance organization and their leader, Captain Kelly, was a former British soldier who demanded exacting discipline. After 1858 the unit wore dark blue frock coats and sky blue trousers and carried the Model 1855 Springfield rifle. With white waist belts and cartridge box slings, and tall shakos for dress parade, they made a natty appearance.29

In early May, while other units of the Missouri volunteer militia trained at Camp Jackson, Kelly’s unit escorted a shipment of two hundred muskets and seventy tons of powder from St. Louis to Jefferson City. There the men learned of Lyon’s capture of the state militia and the subsequent “Camp Jackson Massacre.” When the state legislature created the Missouri State Guard, the Blues volunteered, technically forming a new unit but retaining their name. They promptly elected Kelly their captain. Eventually combined with other companies, including men raised by John S. Marmaduke and Basil Duke, they formed the nucleus of a First Rifle Regiment in Parsons’s Division.30

While Price continued to assemble men at Cassville, the bulk of the State Guard was camped farther north, just outside Lamar, under Jackson’s overall command. Although the men were enlisted only in the service of their state, some of the Missourians displayed Confederate banners. While this was forbidden under Price’s standing orders, no effort was made to remove the Confederate flags, which raises questions concerning the allegiance of the State Guard. Governor Jackson had contributed substantially to the ambiguity of their loyalty by the carefully calculated wording of his June 12 proclamation calling on Missourians to join the Guard in order to resist Lyon. Making no mention of his own negotiations with the Confederacy, Jackson focused on the unconstitutional actions of Lyon, Blair, and Lincoln. He reminded Missourians that as American citizens they were bound by the Constitution and Federal law. But their first loyalty, he argued, should be to their state, and they were “under no obligation whatever to obey the unconstitutional edicts of the military despotism which has enthroned itself at Washington.”31

No comprehensive study of the motivations of the men who served in the State Guard exists. One historian expresses the quandary thus: “For these were STATE troops in capitals. They were not yet Confederates officially, some of them would never be. They were in many cases fighting solely for Missouri, and Missouri was in trouble. . . . nothing was clear cut—it was simply Missouri.”32

Some 20,000 Missourians served in the State Guard from its organization in 1861 until August 1862. At that time, all but a handful of its members either entered Confederate service or went home. Thousands chose the latter course, but whether from fatigue or faint heart, or because their political convictions made Confederate service anathema, will never be known.33 Nor can one determine with accuracy the motivations of the more than 5,000 troops of the State Guard who fought at Wilson’s Creek. The range of their views can be sampled, however.

Long after the war, one veteran asserted that the State Guard had been “typical of the cause and the times” because it was raised in “a popular outburst against the tyranny of Federal power.” Contemporary evidence confirms the old soldier’s memory, at least in the case of some Missourians. The Polk County Rangers are an example. Organized in 1860, long before the secession crisis, they particularly prized their beautiful silk national flag, made by the ladies of Greenfield and presented to them on the Fourth of July. But in late April 1861, following Lincoln’s call for volunteers, the Rangers returned this banner to the donors. In a letter to the local press, they explained that because a “narrow-souled and fanatical minority-President” had ignored “his Constitutional obligations” and the “Rights of the States as sovereignties,” they could “no longer, consistent with honor and justice, march under or fight for the Northern flag.” It was now “the peculiar banner of cutthroats, murderers, and Abolitionists.” But although they proclaimed their loyalty to the South and sympathy for the Confederacy, these Missourians were not Secessionists. For they also pledged that “should our deplorable national difficulties ever be adjusted and the different sections of our country be again united, as God grant that it may,” they would “gladly take back from your fair hands” the Stars and Stripes.34

The Polk County Rangers were conditional Unionists. They wanted neither war nor independence, but their political views and, equally important, their corporate sense of honor, left them no choice when events forced them to choose sides. Early in May the ladies of Greenfield made a “Southern flag” for the Rangers, which was presented at a community picnic. After the Missouri State Guard was formed, these Polk County volunteers, under Captain Ashbury C. Bradford, became part of the large cavalry brigade commanded by Colonel James Cawthorn of Rains’s Division.35

Warner Lewis linked his State Guard service and that of fellow Vernon County residents to fears of attack by Kansas “Jayhawkers,” a name given to bands of antislavery activists who had raided western Missouri frequently during the previous six years. “At the first call for volunteers,” he remembered, “the men in the border counties flew to arms as one man.” Though Lewis doubtless exaggerates the unanimity of sentiment in western Missouri, his explanation of motives is revealing. “These people,” he claimed, “were not all rebels, nor disunionists, but believed that they were serving the lawfully constituted authorities of the State, in repelling invasion and in protecting their homes and firesides.” The Federal government was “lending aid and comfort to the enemies of the State.” Consequently, “it was not possible that an honorable, self-respecting and courageous people would tamely submit to its authority.”36 Although Lewis wrote long after the war ended, his explanations indicate that a corporate sense of honor and community reputation was as strong a motivation for Missourians as it was for soldiers elsewhere.

There is no question that many Missourians fought to preserve slavery, but at the level of individuals information is frustratingly scarce. Take, for instance, James H. McNeill, a Virginian who moved with his slaves to Missouri in 1848. When the war erupted, he owned a three-hundred-acre farm in Davies County, but his real wealth was tied up in neither land nor slaves, but cattle. At age forty-six he might have sat out the conflict without incurring social ostracism, but instead he raised a company of cavalry that included all three of his sons. McNeill’s decision to take up arms eventually cost not only his own life, but that of one of his sons, yet he left no record of his motives. No one was more blunt about the role of slavery in motivating Missourians than John D. Keith, who stated after the war that he had fought “to maintain the integrity of the white race.” Prominent slaveholder John Taylor Hughes also placed race at the center of the question. “The Blacks and Unionists are now all one with us,” he wrote a friend. “We must all share the same fate, and submit to the conquering hosts of abolition, or maintain our independence of them at the point of the sword and bayonet.” Hughes was motivated by more than just a desire to protect the “peculiar institution.” He took up arms, he explained, for “our ancient rights, secured to the people by the Constitution of the State, and of the United States, but now denied to us, and ruthlessly trampled under foot by tyrants and usurpers.” Hughes was a Whig, but although his party had effectively ceased to exist he was a man of influence. A Kentucky native, he was a veteran of the Mexican War, a newspaperman, a school superintendent, and a former state representative. He gave numerous speeches throughout northwestern Missouri and helped raise five companies for the State Guard. When the Caldwell Minute Men, Carroll Light Infantry, Stewartville Rifles, and others were organized into one regiment as part of Slack’s Division, they elected Hughes colonel. But whether they did so because they valued his military experience, endorsed his views on race, or shared his opinion of the political situation is unknown.37

Like most soldiers, North and South, the average Missouri State Guardsman went to war for a variety of reasons. Among them, no doubt, were both a genuine sense of community honor and a fear of the social ostracism that failure to volunteer might incur. There was a determination to protect the status quo and defend hearth and home, which included an assumption of white supremacy and deep alarm at any hint of interference with the institution of slavery. Most supported the right of a state to secede and were shocked by the manner in which Lincoln, Lyon, and Blair violated the Constitution. They were either unaware of, or unconcerned by, Governor Jackson’s direct negotiations with the Confederacy.38

Although there was no shortage of Irish and German Americans in the Guard, one must also wonder about the role of ethnicity in the conflict. The rapid influx of immigrants between 1850 and 1860 made St. Louis one of the fastest-growing cities in the nation. The ability of Lyon, Blair, and Sigel to raise and equip German American regiments rapidly signaled a profound shift in Missouri’s political and social makeup. Power was moving out of the hands of the agriculturally oriented planters of the Missouri River valley. As they spent only a few weeks a year in the rather sleepy state capital, their strength was rural and local. Their orientation, when it went beyond the state, was Southern. The German Americans who followed Sigel, and Republicans like Blair who were eager to cooperate with them, reflected the rise of urban influences. Increasingly tied together by railways, they were national rather than sectional in outlook. Lyon’s actions made St. Louis the true center of political power in Missouri. The troops that marched across the countryside under his direction would help determine, by their success or failure, just what sort of state Missouri would be.