Chapter 6

Good Tents and Bad Water

Ben McCulloch was a busy man. As he watched events unfold in Missouri, he continued to gather forces in the vicinity of Fort Smith. His task was made considerably easier when late in May the Arkansas secession convention—still holding meetings and feuding with Governor Rector—passed a resolution that required the Arkansas State Troops under Bart Pearce to cooperate with the Confederate commander. Not to be outdone, Rector sent McCulloch a message giving him command of all military forces in the state.1

As McCulloch was charged with defending the Indian Territory, and by implication the Confederacy’s boundary from Arkansas west to the Texas-New Mexico border, much of his time was taken up with Native American affairs. On May 30 he left his Fort Smith headquarters with Captain Albert Pike to meet with various tribes in the hope of securing treaties of alliance and recruiting Native American troops for the Confederacy. In the long run, this effort benefited the Confederacy considerably. The Cherokee Nation included a number of slaveholders, mostly men of mixed ancestry, whose sympathies lay with the South. Some of them began organizing immediately under Stand Watie and Joel B. Mayes, but only a small number of Cherokee would participate in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek.2

While McCulloch was thus occupied, troops continued to join his growing western army. Some reached Fort Smith quickly, while others took considerable time. The Third Louisiana was delayed in Little Rock because the water level in the Arkansas River had dropped. Their temporary camp, at a city park near the arsenal, reminded the European-born William Watson of “a nobleman’s park in the old country.” A fellow Pelican, Willie Tunnard, left a similar description. “The grounds,” he recalled, “were beautifully laid out, and shaded by large and handsome oaks.” The Louisianans drilled for six hours each day and in their spare time rolled cartridges for their muskets. Captain David Pierson informed his family back in Winn Parrish: “Our regiment is rapidly improving in infantry exercises. At first we were an awful green set but have improved so far that we do pretty well.” The ladies of the city made frequent visits to the camp, and not a few romantic attachments were made by moonlight. The Third Louisiana also participated in the ceremonial presentation of a flag to a Little Rock company that was part of the First Arkansas Mounted Rifles. The main address, by a Miss Faulkner, was “one of peculiar force and unsurpassed eloquence,” Tunnard recalled. She presented the banner as a constant reminder of the regiment’s duty to protect the state and its citizens from the “ruthless marauders” of the North, proclaiming: “Let it be borne aloft into the thickest of the fight—up to the highest eminence of honor. Let the sight of it animate and encourage you; nerving you in the hour of trial to the utmost pitch of fortitude and courage!” When the speech ended, the Louisianans passed in review, each company saluting the flag as the Arkansans cheered.3

The First Arkansas was organized by Thomas J. Churchill, who later became governor of the state. A native of Louisville, he had served in the Mexican War with a regiment of Kentucky mounted infantry. Moving to Arkansas following his discharge, he married the daughter of a prominent politician and settled down as a planter. His estate, which he named “Blenheim,” included about fifty slaves, making him one of the wealthiest men in the area. A longtime Democrat, he entered politics modestly as Little Rock postmaster in 1857, holding that appointive position until he resigned in 1861 to raise volunteers. The decision was a natural one, as he was already captain of the Pulaski Light Cavalry (also called the Pulaski Lancers), one of the county’s four prewar militia units. When enough mounted companies reached Little Rock to organize a regiment, Churchill was unanimously elected colonel.4

Churchill’s men came from ten different counties and most of their units bore names indicating their community roots. These included the Chicot Rangers, the Augusta Guards, the Yell County Rifles, the Des Arc Rangers, and the Independence Rifles. A notable exception was the Napoleon Cavalry, made up of men from both Little Rock and Fort Smith. The Napoleons contained some unlikely talent in the form of Charles Mitchell, who had attended the Western Military Academy at Nashville for a year, then transferred to St. John’s College in Little Rock. When Churchill’s men camped on the college grounds, Mitchell dropped out of school to enlist, although he was only three months past his fifteenth birthday. Toward the opposite end of the spectrum, in terms of age and education, was farmer John Johnson, a second lieutenant in the Pulaski Rangers. A North Carolina native and forty-eight-year-old father of six, he joined up along with his two oldest sons, Pleasant and Harrison. John and Pleasant Johnson would not survive the fight at Wilson’s Creek, nor would Harrison Johnson survive the war. John wrote dutifully to his wife during his relatively brief military service, but his surviving letters leave no clue about his reasons for enlisting.5

Like any good regimental commander, Churchill was serious about training. A Little Rock newspaper correspondent described his regiment as “very well drilled” and noted that the men were “burning with a desire to meet the impudent cohorts of republicanism.” During one parade the fifes and drums of the Third Louisiana stopped playing because they had spooked a line of Churchill’s horsemen. The colonel asked the musicians to continue so the animals could become accustomed to martial noises. Later Churchill acquired several bugles for the regiment. The horses’ subsequent antics can be imagined. The greatest problem in organizing the regiment was a shortage of weapons. Some companies had arrived expecting to receive arms from the captured Little Rock Arsenal. But there were not enough to go around and a few men returned home. “If we only had arms,” lamented Robert Neill to his home folk. He feared that “if Lincoln’s masters knew their power and our weakness and had courage they might almost devastate our state.”6

Standardization of arms was also a problem. Churchill provoked a near mutiny when he ordered the Pulaski Rangers to exchange their pistols and sabers for flintlock muskets. The men in Lieutenant Johnson’s company considered this an outrage, and Johnson himself, from a decidedly rural perspective, looked down on the “city fops” who made up much of the regiment’s officer cadre. Despite such problems, Churchill was a popular commander. “Everyone that I hear express themselves is pleased with Col. Churchill,” Neill wrote. “He seems a very plain man, yet has the appearance of being a thoughtful and energetic one.”7

By the time McCulloch returned from the Indian Territory in mid-June, the same rains that were to cause headaches for Lyon in Missouri raised the level of the Arkansas River sufficiently for the Third Louisiana and First Arkansas to start for Fort Smith. The trip was miserable, due to excessive heat and cramped conditions on the boats. Some officers of the Louisiana regiment were joined by their wives, who had accompanied them this far. Where they found accommodations in Fort Smith is a mystery, as the town was overcrowded. Men were camped in fields for miles around the fort. Willie Tunnard recalled that the men suffered severely from both the daily heat and an outbreak of measles that swept through the camp. A soldier in an Arkansas unit informed his wife: “We are camped about five miles south of Ft. Smith in the prairie where the sun pours her heat on us without a tree or bush to shade our heads. We have good tents & bad water to drink.”8

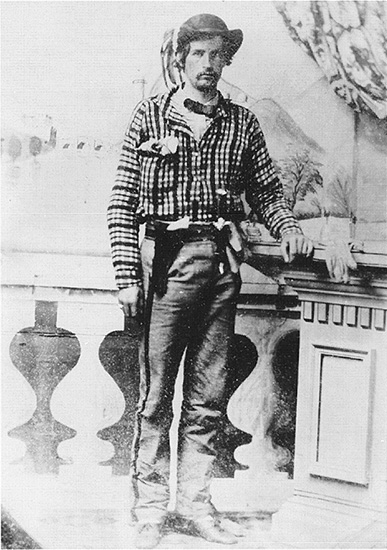

Lieutenant Dave Alexander, Napoleon Cavalry, First Arkansas Mounted Rifles (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Before the month ended some of the troops were shifted across the Arkansas to the town of Van Buren. Among them was the Totten Light Battery. Captain Woodruff’s men camped in the Van Buren courthouse square where the fences could act as a corral for horses. Heretofore the Tottens had exercised their guns by hand, but by purchase and impressment they now acquired the dozens of horses necessary to complete their battery. The maneuvers the men and horses needed to perfect in order to move, limber, or unlimber were quite complex. Woodruff realized to his horror that this portion of artillery drill, which he had last performed nine years ago at his military school in Kentucky, had escaped his memory. He therefore found a pretext to return to Fort Smith, where a few minutes observing Captain John G. Reid’s Fort Smith Light Battery at drill brought the procedures back to him.9

In time, the force available to McCulloch reached considerable proportions. In addition to Colonel Louis Hébert’s Third Louisiana and Colonel Thomas Churchill’s First Arkansas Mounted Rifles, his Confederate troops consisted of the Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles under Colonel James M. McIntosh and a battalion of infantry under Lieutenant Colonel Dandridge McRae. Together these units eventually totaled almost two thousand men, and Greer’s South Kansas-Texas Cavalry, still en route, would raise the number even higher. Although the men and animals stationed around Fort Smith consumed several tons of food and fodder daily, as long as they remained near the Arkansas River supply problems were not insurmountable, at least from the commander’s point of view. On June 14 John Johnson grumbled in a letter to his wife, “Our fare is very rough. Horse food scarce.”10

McIntosh led the Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles. He had earned a degree from West Point a year after the end of the Mexican War, a conflict that had taken the life of his father, a colonel in the Regulars. Although he graduated last in his class, by 1857 he was a captain in the First U.S. Cavalry. This was an astonishingly swift rise for peacetime service, and his regiment was considered by many to be the elite of the army. McIntosh resigned his commission in May 1861, while stationed at Fort Smith. He had no way of knowing that this action would profoundly affect his younger brother. Believing that James had disgraced the family name, John Baillie McIntosh volunteered for the Union forces. John eventually rose to the rank of major general, James to brigadier general, but only the brother in blue would survive the war.11

The companies that formed McIntosh’s unit came mostly from northwestern Arkansas. Although no statistical analysis has been made of it, names that might indicate foreign birth are conspicuously absent from its muster rolls. The information available suggests that leadership at the company level otherwise reflected a diversity common with other units. The captains included Ben T. Embry, a prosperous farmer and merchant who had organized a company at Galla Rock. Embry was forty-one, while John A. Arrington, who led a company from Bentonville, was only twenty-four. Mexican War veteran Henry K. Brown raised a company at Paraclifta, and George E. Gamble brought in a company from Hempstead. Gamble’s men joined the regiment late, on August 4, less than a week before the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. Whatever the cause of their delay, it allowed them time to receive a flag from the women of the county before leaving.12

The list of company commanders also included future Arkansas governor Harris Flanagin. Born in Rhodestown, New Jersey, he had attained only a common school education before becoming a teacher himself at the Clermont Seminary in Frankfort, Pennsylvania. In a short time he was made professor of mathematics and English. In 1838 he opened his own school in Paoli, Illinois, and the next year was admitted to the bar. Law had apparently been his ambition from the first, for he moved to Greeneville, Arkansas, in 1839 and set up a practice. Politically Flanagin was a Whig. He was a deputy sheriff for Clark County and served a term as state senator. Described as having “a mathematical turn of mind, precise and exact in all his dealings,” he was “a very poor orator unless his tongue caught fire from the force of his thoughts.” Although he had opposed secession, Flanagin raised a mounted company as soon as war broke out, riding into Fort Smith with eighty-eight volunteers for the Confederacy. They were armed with double-barreled shotguns and “large home-made knives ranging from twenty-five to thirty-six inches in length.” Bird, Flanagin’s part-Choctaw African American slave, accompanied him, as he would throughout the war.13

The unit commanded by Dandridge McRae had no numerical designation, being identified on muster rolls simply as McRae’s Battalion, Arkansas Volunteers. McRae, who was thirty-two, grand master of his Masonic lodge, and a slaveholder, was a native of Baldwin County, Alabama, and a graduate of the College of South Carolina. He moved to Searcy, Arkansas, in 1849, read law, and was admitted to the bar in 1854. Two years later he was elected county and circuit court clerk.14

When his state left the Union, McRae immediately raised a company of volunteers from White County. Shortly thereafter Governor Rector made him inspector general of Arkansas State Troops. During June and July McRae also assisted McCulloch in attracting recruits for Confederate service. His battalion was not large, fielding just over two hundred men at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. Surviving records, which are incomplete, reveal that its companies were a mixed lot. Levels of training ranged from “good” to “insufficient” and discipline from “fair” to “indifferent.” Arms were described as “indifferent,” varying from percussion muskets to “Common hunting guns of the country.” Some men had cartridge boxes, waist belts, canteens, and blankets, while others had none. Two thirds of the men were issued matching pants and blouses, apparently gray, but shoes were desperately needed.15

Records for the company raised by Captain C. L. Lawrence, a twenty-eight-year-old lawyer originally from Kentucky, are unusually complete. The company’s youngest member was William M. Sisco, at age fifteen only five feet tall. He was listed as a farmer and an Arkansas native. The oldest soldier, forty-seven-year-old Maston K. White, was also a farmer and a native of South Carolina. Most of the men gave their occupations as farmer, but there were also teachers, carpenters, and blacksmiths, a wood chopper, a painter, and a distiller. All but eight men were born in the South. The company contained two men born in Germany, two born in Ireland, and four born in Northern states. The battalion’s most interesting recruit was Mark Mars, a seventeen-year-old farmer who was listed as one-quarter African American and three-quarters Cherokee. By the social customs of the South he was considered to be a black man. Yet Mars was not a camp servant or a slave like Flanagin’s Bird, but a free man and a soldier. His motives for enlisting and his relationship with the white men in his unit remain a tantalizing mystery.16

When the Arkansas authorities gave McCulloch control over the state troops, they doubled the effective force available to the Confederate commander. Like McCulloch, Bart Pearce had been busy organizing and training his troops, a process that was not complete until late July. Although he had troops posted at several locations, his main facility, Camp Walker, was strategically located near Maysville, a small village in the extreme northwestern corner of the state. Roads leading due south linked it with Fort Smith, while those heading southeast gave access to Bentonville and Fayetteville, which were on the Wire Road that ran north to Springfield. The camp utilized a five-hundred-acre tract of land and set of buildings recently abandoned by the Harmonial Vegetarian Society, a failed perfectionist community. This made good sense, as the commune’s main building, three stories tall with ninety rooms, made an excellent barracks. But in early June, Pearce was accused of selecting the site to allow his father-in-law, Dr. John Smith, to sell the soldiers flour at inflated prices from his nearby gristmill. A board of officers conducting an investigation of the matter exonerated Pearce, but the episode was a major distraction.17

The force eventually assembled by Pearce consisted of two understrength cavalry units, three infantry regiments, and two artillery batteries. Colonel DeRosey Carroll led the First Arkansas Cavalry (also called the First Arkansas Mounted Volunteers). This was supplemented by a separate, smaller unit, known simply as Carroll’s Arkansas Cavalry, led by Captain Charles A. Carroll. Together they numbered almost 400 men. The three infantry units, roughly equal in strength, were 1,700 strong. Colonel John Gratiot led the Third Infantry, Colonel Jonathan D. Walker the Fourth, Colonel Tom P. Dockery the Fifth. They were supplemented by Reid’s Fort Smith Battery and Woodruff’s battery, each with four guns. In June Woodruff’s battery changed its name from the Tottens to the Pulaski Light Battery, as news from Missouri now made it apparent that Captain James Totten would be a future enemy.18

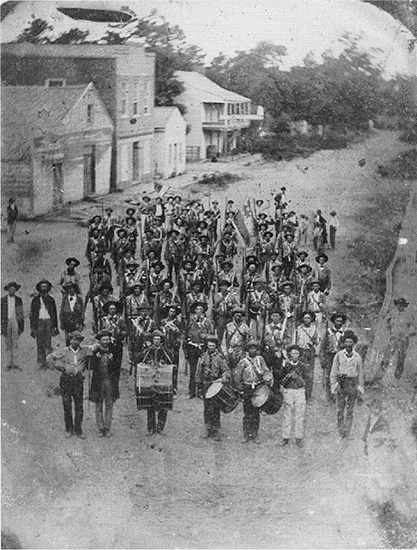

A rare prebattle photograph of Company H of the Third Arkansas Infantry, Arkansas State Troops (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

With the exception of Woodruff’s unit, even less is known about the Arkansas State Troops than the Missouri State Guard. Some of Pearce’s men had been examined by McRae back in early May, while he was acting as state inspector general. He described the volunteers as “the wildest blood in the South.” He meant this as a compliment, for his praise of them was extravagant, writing: “They are however the best men in the whole state. It makes the heart of any true friend of Arkansas thrill with pride to see what men we are enabled to turn out. There is no drunkenness, no noise, no confusion, and they cheerfully obey every order.”19 Although good troops, in reality the Arkansans fell considerably short of the sainthood McRae was willing to bestow on them.

When McCulloch learned that Lyon had negated the so-called Price-Harney agreement by declaring war on the state of Missouri, he immediately began shifting as many troops as possible from the Fort Smith-Van Buren area to join Pearce at Camp Walker. Units moved individually over a period of several weeks. Woodruff’s Pulaski Battery received quite a send-off, as “the mistaken hospitality of some of the Van Buren people had overflowed with something stronger than water.” In plain terms, some of the men were drunk. The first day’s march was a nightmare. Officers and men lacked experience, but worse still many of the horses had never been trained to harness. As a result the battery was soon strung out for miles. Although discipline improved over the next few days, crossing the Boston Mountains was onerous. The overall effect of the experience was positive, however, as it illuminated the battery’s defects. Once established at Camp Walker, Woodruff instituted a vigorous program of drills.20

The Third Louisiana was not ordered north until June 28. For reasons that are unclear, the regiment moved in two separate battalions, with a day’s interval between them. Like Woodruff’s artillerists, the Louisianans had logged more miles on steamboat than on foot. In fact, they had never marched with full equipment. Consequently, the movement to Camp Walker was long remembered by veterans of the Wilson’s Creek campaign. The trip commenced “amid the wildest enthusiasm” but proved to be a “severe experience.” Willie Tunnard recalled: “Shoulders grew sore under the burden of supporting knapsacks; limbs wearied from the painful march, and feet grew swollen and blistered as the troops marched along the dusty road. Knapsacks were recklessly thrown by the roadside or relieved of a large portion of their contents, under the intolerable agony of that first march of only nine miles.” But soon a routine was established, and the men bore their hardships “with fortitude and courage, keeping up their spirits with songs and jokes as they tramped steadily forward.” Because of the intense heat, reveille was usually sounded around 2:00 A.M., with a halt for the day called at noon. Crossing the Boston Mountains was so exhausting that for weeks afterward mere mention of them produced “expletives innumerable.”21

Captain R. M. Hinson of the Moorehouse Guards described the experience as “a hard march of seven days covered with dust & blistered feet.” But in a letter to his wife Mattie, he also noted traveling through “a beautiful valley from one to three hundred yards wide, with mountains on each side higher than any bluff you have seen on the Ark. river.” Nor had the trip been without its pleasures. At the home of a Mrs. Foster, who was apparently kin to his wife, Hinson and a friend obtained “a ham boiled & turkey baked which lasted us several days.” The captain apparently did not share this bounty with his enlisted men, but he refused an offer to stay overnight in the comforts of the Foster home, citing his command responsibilities.22

The battalion that included Hinson’s company had just reached the Boston Mountains when word arrived from McCulloch to make a forced march for Camp Walker. Although the prospect was dismaying, the reason for McCulloch’s orders brought unparalleled excitement to the Louisianans. Governor Jackson’s Missouri State Guard was reportedly about to be overwhelmed by the forces directed by Lyon. In response, “Old Ben,” the self-taught Texas Ranger who eschewed swords or uniforms, wore a dark civilian suit, and rode with a rifle across his saddle horn, had just initiated the first invasion of the United States by the Confederacy.23

McCulloch had been preoccupied with events in Missouri for some time. If Missouri joined the Confederacy, his task of defending the Indian Territory would be much easier, as thousands of Missourians could be expected to join Confederate regiments. But the present condition of affairs, a literal civil war between the legal state government and the administration in Washington, left McCulloch in a quandary. The Confederacy’s legitimacy rested on an expression of the will of the people in each state. How could Confederate authorities intervene in a state that was still in the Union and might remain so?

When McCulloch received a request for assistance from Governor Jackson, his response balanced political expediency with his own duties. On June 14 he asked the War Department for permission to move north through the Indian Territory to seize Fort Scott, Kansas. The Confederate government might proclaim that the Southern states merely wanted to depart in peace, but McCulloch considered a good offense to be the best defense. He was apparently untroubled by the larger implications of his suggestion. He believed that a movement into Kansas would probably force John Ross, the principal chief of the Cherokee, to abandon his current neutrality and begin recruiting regiments for the Confederacy. This would protect the Indian Territory, which was McCulloch’s primary responsibility. Moreover, the presence of his troops in Kansas would relieve pressure on the Missouri State Guard without placing a single Confederate soldier on Missouri’s sensitive soil. In response, the War Department on June 26 authorized McCulloch to move into either Kansas or Missouri, as circumstances warranted. The Texan then gave orders to concentrate all available forces in the vicinity of Maysville. Any action he contemplated would have to be prompt, for as the summer progressed the water level in the Arkansas River would decrease, exacerbating his supply problems.24

Although Arkansas officials had placed their state’s troops at McCulloch’s disposal, Arkansas was not part of his military department, and his requests to Richmond for permission to use them went unanswered. In fact, late in June the War Department appointed Brigadier General William J. Hardee, who was then in Memphis, commander of Confederate forces in Arkansas. But McCulloch did not know this, and in the absence of any prohibition he not only accepted command of Pearce’s troops but also issued a proclamation calling all Arkansans to rally to the defense of their state against the “Black Republicans” invading Missouri. Like Lyon, McCulloch was not a man to quibble over legalities when action seemed necessary.25

Soon after reaching Maysville, McCulloch met with Sterling Price, who had crossed into Arkansas to seek his help. The Missouri general provided firsthand information about the strategic position of the State Guard. Price had established a camp on Cowskin Prairie in the extreme southwestern corner of Missouri, assembling some 1,700 men. But Springfield was in Union hands and a column of troops under Sigel was reported to be near Neosho, between Price’s and Jackson’s forces. Should Sigel defeat Jackson, or should Jackson be caught between Sigel’s men and Lyon’s column, the Missouri State Guard might never be able to concentrate at one location to complete its recruiting and training. On the other hand, if Price, Pearce, and McCulloch rushed north, their combined forces and those of the Missouri governor might crush Sigel between them. Such a movement was clearly authorized under McCulloch’s June 26 dispatch from the War Department. A week after those instructions were written, the secretary of war, Leroy Pope Walker, informed McCulloch that a decision to invade the north was best left to the higher authorities. Yet he acknowledged that because of the circumstances and slow nature of communications, McCulloch might have to act on his own initiative. This loophole was fortunate for McCulloch. For on July 4, the very day Walker composed his letter in far-off Virginia, McCulloch led Confederate troops across the border. Recognizing both the peril and the opportunity, he and Pearce had agreed to assist Price.26

McCulloch intended to move with every available man—both the Confederate forces under his direct command, which were styled McCulloch’s Brigade, as well as the Arkansas State Troops, designated Pearce’s Brigade. But after receiving a message on July 5 that a battle between Jackson and Sigel was imminent, he pushed ahead with a vanguard of three thousand mounted men, drawn from both brigades. He had not gone far before learning that Sigel was now near Carthage, farther north than originally reported. Although this news made it unlikely that McCulloch’s troops could arrive in time to assist Jackson, he acted as aggressively as possible under the circumstances. While the main force went into camp after its hard march, he selected his freshest men and ordered them to press on to capture the small garrison Sigel had left behind at Neosho.27

The attacking force was led by Colonel McIntosh, who in addition to commanding the Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles held a position on McCulloch’s staff and acted, unofficially, as his second-in-command. The troops came from Churchill’s First Arkansas Mounted Rifles, supplemented by Carroll’s Arkansas Cavalry. The men moved in two columns, one under McIntosh, the other under Churchill, approaching Neosho from the south and west. Churchill arrived first and, fearing that the enemy would escape, attacked immediately. The result was anticlimactic, as the Federals surrendered without a shot. The first military engagement of the war involving substantial numbers of Confederate troops on Northern soil was a bloodless Southern victory.28

In addition to capturing Captain Joseph Conrad and 137 men of the Third Missouri Infantry, McIntosh netted a company flag, one hundred rifles, and seven wagons loaded with provisions. But this was no substitute for assisting Jackson. During the evening McCulloch heard artillery fire to the north. Consequently, he remounted his men for an all-night march. They joined McIntosh at Neosho in the morning of July 6 and after a short rest continued north. Some twenty miles beyond Neosho they finally encountered Jackson’s men. The Missouri governor was jubilant and rightly so. The day before the State Guard had defeated Sigel, redeeming the disgrace of Boonville and derailing Lyon’s strategy in one swoop.29

Although too small to be dignified by the term “battle,” the skirmish that began on the morning of July 5 was prolonged. Scouts had brought Jackson word on the previous evening that the Federals were camped to the south, in the vicinity of Carthage. Although one of his subordinates urged an immediate attack, the Missouri governor abandoned the element of surprise in order to choose a favorable position. On the morning of the fifth he aligned his men on the high ground above Coon Creek, several miles north of Carthage, and waited for Sigel to find him. His troops—the State Guard divisions of Rains, Clark, Slack, and Parsons—numbered over four thousand men and included two artillery batteries. But although this gave them a numerical advantage over Sigel’s reported force, the State Guard was poorly armed. Many soldiers had only shotguns or hunting rifles, and ammunition was scant not only for infantry but for artillery as well.30

Jackson’s position was not actually a trap, but it did allow Sigel to display his own rashness and ineptitude. When the Union commander discovered his enemy, he decided to attack even though he had only 950 infantry. Crossing the creek, he placed his artillery in advantageous positions. The fight began around 11:00 A.M. as an artillery duel that pitted Major Franz Backof’s Missouri Light Artillery against fellow Missourians in the State Guard batteries of Captain Hiram Bledsoe and Captain Henry Guibor. But when Sigel’s infantry advanced through the open prairie, flanks exposed and numerical inferiority plain to see, Jackson’s lack of military experience hardly mattered. When the State Guard began outflanking the Federals, Sigel was forced to withdraw. This pattern was repeated throughout the day, as Sigel made a fighting retreat all the way back into the streets of Carthage.31

To his credit, Sigel never panicked. His men fought well, allowing Sigel to extricate himself from a desperate situation with his force intact and safely take the roads that eventually led them back to Springfield. Because of the odds against them, both Sigel and his men considered the encounter a victory and their morale was not compromised. Casualties were inconsiderable—several dozen on each side—and the men gained valuable combat experience. The German Americans who made up the bulk of Sigel’s force now idolized their commander, who, thanks to national coverage of their skirmish, began to make a name for himself among his fellow immigrants across America.32

The fight, however, revealed much about Sigel that boded ill for the Union cause. He was laudably aggressive and willing to take risks; commanders who lack those qualities cannot win wars. But he failed to grasp the tactical situation because he neglected to perform basic reconnaissance. This was a mistake he would repeat at Wilson’s Creek and on other occasions throughout his career.33

Lyon received word of Sigel’s fight on July 9, and concluded that Sigel was in danger of being destroyed. Lyon’s entire column consequently began a forced march for Springfield, the freshest troops taking the lead. Eugene Ware of the First Iowa recalled: “Lyon wanted some men on the banks of the Osage river just as soon as he could get them there, and he thought the ‘greyhounds’ from Iowa could get there sooner than anybody. We struck up ‘The Happy Land of Canaan,’ and moved off, with General Lyon evidently pleased with our style, as he sat on his horse and watched us. Lyon did not smile when he was pleased—he just pulled his chin whiskers with his mouth half open.”34

Leaving tents and other baggage behind, the men trudged through blistering heat at a killing pace on short rations. There were few halts for rest. Indeed, at one point the Federals covered fifty miles in thirty hours.35 Ralph D. Zublin, a private in the Governor’s Grays of the First Iowa, left a particularly vivid description of a portion of the ordeal in a letter to his wife:

The dust and heat were oppressive. Along the road side were strewed by scores the regulars. . . . Out of our company of 97 men, only 27 marched into camp and stacked arms. Other companies were completely broke up. Of the Iowa City company in our regiment eight men came in. A company behind us came in twenty-one strong and not an officer. But to cap the climax we were wet with the dew and completely exhausted for the want of food and sleep. We had no place to sleep but in the wet weeds of a cornfield, as our blankets were miles back on the wagons. . . . Walking in a hot sun, carrying a ten pound musket, equipment, belts, cross belts, cartridge box, with forty rounds of cartridges in it, haversack, canteen, etc., slung on is a trial of endurance, and I find that I stand it as well as any man in the regiment. It surprised me to find out how much I could do.36

Riding ahead, Lyon reached Springfield on July 13. The column straggled in over the next few days. The Federal concentration was now complete, with over five thousand men occupying camps encircling the town.37 But the military situation had changed. Sigel’s withdrawal at Carthage meant that Lyon’s overall strategy had failed. Lyon had neither prevented Jackson and Price from raising an army to oppose him in Missouri nor trapped the Missouri State Guard forces retreating from the central portion of the state. True, Lyon had initiated the first major campaign of the war, and his operations were more complex than those that any other general, North or South, had yet attempted. But far from destroying Secessionist strength in Missouri, Lyon’s actions concentrated the State Guard in a location where it was now receiving Confederate support.

Several things should be considered in evaluating Lyon’s performance. In the initial movement of his own column and the one under Sweeny, Lyon had made masterful use of rivers and railways. Given the shortages of horses, mules, and wagons that he faced once all three of his columns left their river or rail connections, his operations were as swift as humanly possible. Civil War commanders rarely trapped or pinned down their enemies. In short, Jackson and Price escaped because Lyon’s strategy was too ambitious, not because its execution was poor. No officer in the Union army had accomplished more than Nathaniel Lyon had during the summer 1861. His subordinates Sturgis and Sweeny had performed creditably operating on their own, and the men Lyon had assembled at Springfield made a formidable team.

By mid-July the forces that would fight the second battle of the Civil War were largely in place. The commanders faced important decisions, and the officers and men under them still had much to learn about becoming soldiers.