Chapter 12

I Will Gladly Give Up My Life for Victory

The enlisted men in the Union army were not privy to the details of the plans discussed by their superiors, but word that a decision had been made to attack the Southerners swept through the ranks on August 9. In his diary William Branson wrote: “Great stir in camp this evening. General Lyon has issued an order that this night shall decide the fate of southern missouri. . . . We are going to march on them to night [and] are now making every preparation for moving.” Branson’s hope that a climax to their efforts might be near is understandable, for much had happened since the army’s initial skirmish with the Missouri State Guard at Boonville in June. The hardships had been severe. Soldiers unable to withstand the rigors of campaigning “had broken down and were things of the past.” When rations fell short and uniforms wore out, the soldiers had learned to forage for both food and clothing. In the Second Kansas, for example, a soldier in the Phoenix Guards recorded that while they still had their dark blue government-issued blouses, many men were barefoot. As replacements for the shirts and trousers brought from home they now had “a miscellaneous assortment of other clothing such as the country afforded,” together with every type of headgear imaginable. Nor were officers exempt from privations. The soldier noted that Lieutenant John K. Rankin was “in rags like the rest.”1

But with tribulation had come experience, and if the men were leaner they were also tougher. By early war standards, they were seasoned campaigners, having endured weeks of long, hot marches. Because the army’s quartermaster and commissary departments had been unprepared to meet the demands placed on them for this, the war’s first real campaign, the men had often gone hungry and they had made their camps with inadequate tentage and equipment. Yet they had acquired invaluable combat experience, having “seen the elephant,” at Boonville, Carthage, Forsyth, Dug Springs, or during the recent, almost daily skirmishing on Grand Prairie west of Springfield. Although these were brief, small-scale actions, they had allowed most of the units in Lyon’s army to hear the roar of artillery and the crash of muskets. These factors offered significant compensation for the enemy’s reported superiority in numbers.

Lyon knew that his men were about to face their greatest challenge yet, and as the army prepared for its night march, he moved among those close by with words of advice. His actions left a particularly strong impression on Eugene Ware. When the First Iowa responded to the bugle call to fall in, they formed an irregular line because there were no tents to serve as a guide. After standing in formation for “some minutes,” they observed Lyon, mounted on his dapple gray horse, riding toward the regiment. As the companies were widely spaced, he paused for about a minute before each one. Reaching the Burlington Zouaves, he said: “Men, we are going to have a fight. We will march out in a short time. Don’t shoot until you get orders. Fire low—don’t aim higher than their knees; wait until they get close; don’t get scared; it’s no part of a soldier’s duty to get scared.” Lyon doubtless meant his words to be encouraging, but Ware thought them “tactless and chilling,” and the only feeling they seemed to convey was one of exhaustion on the general’s part. Fellow private William P. Eustis simply asked, “How is a man to help being skeered when he is skeered?” Ware recalled this episode many years following the close of the war, but an Iowa soldier writing only a week after the battle also characterized Lyon as fatigued. When the general reached the Muscatine Grays, he appealed directly to their honor. He reminded them that as the army’s only representatives from Iowa, the people not only in their home state but also across the nation would judge them by their conduct in the coming battle. Victory would win the Iowans the thanks of the whole country, whereas defeat would mean surrendering the entire Ozarks region to the enemy. The general ended by telling the men that if they stood firm the enemy would not stand against them. Yet even as Lyon spoke, listeners could “detect traces of deep anxiety in his countenance and voice. The latter more subdued and milder than usual.” Overall, the Iowans might have been more inspired by the words reportedly spoken by Captain Thomas Sweeny to some of the cavalry: “Stay together, boys, and we’ll saber hell out of them.”2

After Lyon departed the Iowans drew ammunition, filling not only their cartridge boxes, but trouser and shirt pockets as well. Two days’ rations of beef and pork were also distributed. While they were cooking the meat, a wagon appeared and its driver tossed large turtle-shelled loaves of bread onto the ground, where they “bounced around in the dirt and bushes.” Because Ware had discarded his worn-out haversack, he was forced to employ inventive methods for carrying his rations. First, he took a loaf of bread and “plugged it like a watermelon and ate my supper out of the inside.” After frying his beef and pork, he stuffed the meat into the loaf and “poured in all the fat and gravy.” Finally, he recalled, “I took off my gun-sling and ran it through the hard lip of the loaf, hung them over my shoulder, filled my canteen, and was ready for the march.”3

Instructed to return to Deitzler’s Fourth Brigade, the Iowans marched into Springfield around 6:00 P.M. The disciplined regiments lining the streets presented a marked contrast to the civilian population. “The town was in utter confusion,” according to one soldier. “Merchandise and household goods were being loaded into wagons to be ready for the worst. The storekeepers and citizens distributed food to the soldiers with lavish hospitality, and wished them good luck in tones which betrayed forebodings of disaster.”4

Lyon’s feelings as the army assembled are unknown, but he may have been comforted by the knowledge that every possible preparation had been made for the coming contest. He led the main attack force, which had been organized into two brigades, in person. Major Samuel Sturgis’s First Brigade, which spearheaded the march, was the smallest in the army, with fewer than seven hundred officers and men. It was composed of Sturgis’s own infantry battalion of Regulars, now led by Captain Joseph B. Plummer; Major Peter J. Osterhaus’s battalion from the Second Missouri Infantry; Captain James Totten’s Company F, Second U.S. Artillery; Captain Samuel N. Wood’s Kansas Rangers (the mounted company of the Second Kansas Infantry); and Lieutenant Charles W. Canfield’s Company D, First U.S. Cavalry.5

The Regulars under Plummer headed the column. These three hundred men were from Companies B, C, and D of the First U.S. Infantry, plus a “company of rifle recruits.” Plummer commanded Company C, and, as senior captain, control of the battalion fell to him as well. Although an experienced officer, the forty-four-year-old Massachusetts native had seen no combat prior to the Civil War. A 1841 graduate of West Point, in the same class as Lyon and Totten, he was initially assigned to the First U.S. Infantry. After years of garrison duty he probably welcomed the Mexican War, yet he was forced to spend the first year of that conflict on sick leave. By the time he reached the field much of the action was over. As an officer with the forces garrisoning Vera Cruz and later Mexico City, he performed necessary service, but it was hardly exciting. Plummer became his regiment’s quartermaster when the war ended and spent most of the years before 1861 at various posts in Texas, reaching the rank of captain in 1852.6

Captain Charles Champion Gilbert, who led Company B, ranked twenty-ninth in the West Point class of 1846, which in addition to Sturgis had included A. P. Hill, Thomas J. Jackson, George B. McClellan, and George E. Pickett. Assigned to the Third U.S. Infantry, the thirty-nine-year-old native of Zanesville, Ohio, had fought at Vera Cruz during the Mexican War and had served as part of the occupation garrison after it surrendered. Promoted to first lieutenant following the war, he taught geography, history, and ethics at the Military Academy. In December 1855, he was promoted to captain and sent west. The mundane nature of the army’s constabulary duty was demonstrated by the fact that during six years on the Comanche frontier in Texas, he participated in only one fight.7

Captain Daniel Huston was in charge of Company D. Thirty-fifth in the West Point class of 1848, he began his military career in the Eighth U.S. Infantry but soon transferred to the First Regiment. Like Plummer and Gilbert, he spent most of his early career at various Texas posts. He was promoted to captain in 1856 and spent three years back east on recruiting duty. In 1859, however, he was reassigned to garrison duty in the West.8

Lieutenant Henry Clay Wood of Company D, First U.S. Infantry, commanded the company of recruits. Born in Winthrop, Maine, he graduated from Bowdoin College in 1854 (two years after Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, who was destined to win fame at Gettysburg). During the next two years Wood served as the clerk in the office of the Maine secretary of state and studied law. Though admitted to the bar in 1856, he chose a military career instead and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the First Infantry that year.9

In all, the officers of Plummer’s battalion combined sixty-five years of military service. Although only a minor portion of their service embraced actual warfare, they were veterans in the areas of discipline, training, organization, and other aspects related to the exercise of command. While forming but a small part of the Army of the West, they stood as perhaps the foremost example of the high degree of professionalism that lent disproportionate strength to Lyon’s force.

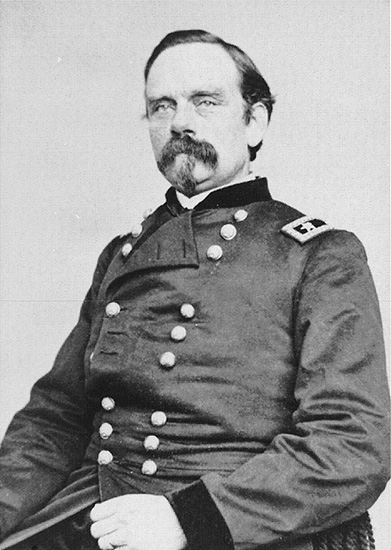

Thirty-eight-year-old Major Peter J. Osterhaus marched behind Plummer. His 150-man battalion consisted of Rifle Companies A and B of the Second Missouri Infantry. The bulk of the regiment had been left to garrison Jefferson City during the opening stages of the campaign. Originally from Coblenz in Prussia, Osterhaus was a graduate of a Berlin military school and a veteran of the 1848 revolution. After emigrating to the United States he settled initially in Illinois but later moved to St. Louis, probably attracted by its large German population.10

Major Peter J. Osterhaus, Second Missouri Infantry. This photograph was taken after his promotion to major general. (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Captain James Totten’s Company F, Second U.S. Artillery, followed next in line. Assisting the captain with his six-gun battery was Lieutenant George O. Sokalski. In 1857 the Polish American entered West Point, one month short of his seventeenth birthday. Probably ranked among the “Immortals” as a plebe, Sokalski stood fiftieth in a class of fifty-nine cadets at the end of the first year. But he persevered and became the first Polish American to graduate from the U.S. Military Academy. Sokalski ranked fortieth out of forty-five in the class of 1861. Commissioned a second lieutenant in the Second Dragoons in May, the twenty-two-year-old Sokalski spent most of that month drilling volunteers in Washington. Ordered to join his regiment, he accompanied Captain Gordon Granger, Lieutenant John Du Bois, and other officers in escorting a group of recruits to Fort Leavenworth. Like Granger and Du Bois, he was assigned to Sturgis’s column. After it joined forces with Lyon, he went to Totten’s Battery.11

Two mounted units completed the marching order of the First Brigade. These were Samuel Wood’s Kansas Rangers, about sixty effectives, and Lieutenant Charles W. Canfield’s Company D, First U.S. Cavalry. Wood was born and raised in Ohio. The son of Quaker parents, he taught school and acted as a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad. He also studied law, and after admission to the bar in 1854 he moved to Kansas, quickly earning a reputation as a leading antislavery advocate. He served as a delegate to both the Republican Party’s first national convention in 1856 and to the Kansas constitutional convention in Leavenworth in 1858. Twice elected to the territorial legislature, he was also chosen a state senator following the admission of Kansas to the Union in 1861. Canfield, from Morristown, New Jersey, had entered the U.S. Military Academy in 1853. He did so poorly academically that he was arrested and briefly confined to his quarters for “a general neglect of studies.” He withdrew from the academy shortly thereafter, but just two weeks following the firing on Fort Sumter, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Second U.S. Dragoons. With the rapid expansion of the Regular Army during the crisis, men with any degree of experience were valued.12

The Third Brigade, which came next in Lyon’s column, was over 1,100 strong. Led by the First Missouri’s Lieutenant Colonel George L. Andrews, it was composed of three units: Captain Frederick Steele’s battalion of Regulars (Companies B and E, Second U.S. Infantry), a company of “Regular Service Recruits,” a company of “Mounted Rifles, Recruits,” Lieutenant Du Bois’s four-gun battery, and the First Missouri Infantry. The command structure in the brigade demonstrates how in many cases the demands of war forced soldiers to exercise command at a higher level than their peacetime rank would have warranted.13

Battalion commander Frederick Steele was a New Yorker, born in 1819. Entering West Point in 1839, he ranked thirtieth in the class of 1843 and was assigned to the Second U.S. Infantry. During the Mexican War he participated in at least five combat actions, receiving brevets for his “gallant and meritorious conduct” at Contreras and Chapultepec. In the years leading up to 1861 he served in numerous posts, obtaining his captaincy in 1855. For want of officers, Companies B and E were led by their first sergeants. Technically, Nathaniel Lyon commanded Company B in his capacity as a captain in the Regular Army, but his responsibilities as brigadier general of volunteers naturally absorbed all of his attention. As the company’s first lieutenant, J. D. O’Connell, was absent on recruiting duty and no second lieutenant had been assigned to the unit, command fell to the senior noncommissioned officer, William Griffin. A native of Dublin, Ireland, Griffin listed his occupation as laborer when he joined Company B as a private in 1854. Army life must have suited him, for he rose to the rank of first sergeant by 1861. The captain of Company E, Frederick Steele, now commanded the battalion. The unit’s first lieutenant, James P. Roy, was on detached service at Fort Leavenworth, and Second Lieutenant Joseph Conrad had been reassigned to Lyon’s staff. Therefore First Sergeant George H. McLoughlin took charge. Originally from Roscommon, Ireland, he had been a clerk before joining the army the same year as Griffin. He had also adapted well to military life, rising to first sergeant in 1861. Warren L. Lothrop led the “Regular Service Recruits.” A native of Leeds, Maine, he joined the Corps of Engineers as a private in 1846 and rose slowly through the ranks. In 1857 he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Fourth U.S. Artillery. “Lance” Sergeant John Morine commanded the Mounted Rifles recruits company. A native of Dumfries, Scotland, and a coachman before joining the army in 1851, his career was most unusual. He obtained the rank of corporal but deserted in 1856. Apprehended in December 1860, he apparently escaped severe punishment, for he not only resumed his service but also within eight months had risen to the rank of sergeant.14

Although Steele’s battalion included only Steele and Lothrop in command positions, it did not lack experience at that level. Steele was a combat veteran with seventeen years in the military. Lothrop had been in the service for fourteen years, the last four as an artillery officer. The combined service of Sergeants Griffin, McLoughlin, and Morine totaled twenty years. In all, the leaders of Steele’s battalion had fifty years of experience in the Regular Army.

Lieutenant Colonel Andrews played no role in his brigade’s command during the battle. The First Missouri’s colonel, Frank Blair, had been ordered to remain in St. Louis, while its major, John Schofield, served as Lyon’s chief of staff. This left Andrews the senior officer, and his full attention was focused on his Missourians.15

The final brigade in Lyon’s column was commanded by Colonel George W. Deitzler. Composed of three infantry regiments—the First Kansas, Second Kansas, and First Iowa—the Fourth Brigade, with 2,300 foot soldiers, was the army’s largest. Also moving with Deitzler were 200 mounted Dade County Home Guards commanded by Captains Clark Wright and Theodore A. Switzler.16

All told, Lyon’s column numbered 4,300 effectives—3,800 infantry, 350 mounted men, and 150 cannoneers with 10 guns. Several local citizens, including Pleasant Hart and Parker Cox, volunteered to act as guides.17

To protect Springfield, Lyon left Captain David S. Stanley’s Company C, First U.S. Cavalry, the 1,200-man strong Greene and Christian County Home Guard, and a section of Backof’s Missouri Light Artillery. The Home Guards were instructed to patrol the Wire Road toward Wilson Creek and send word to Lyon if the Southerners moved up the road against Springfield. Meanwhile, preparations commenced for the planned Union withdrawal to Rolla, dictated by the logistical crisis regardless of the outcome of the battle.18

The opening scene of the final act of Lyon’s long campaign to punish Secessionists in Missouri began on August 9 at 5:00 P.M., when Sturgis’s brigade left its camp at the Phelps farm. The men marched about a mile north to the town square, then turned west onto the Mt. Vernon-Little York Road. Captain Gilbert’s Company B, First U.S. Infantry, led the advance. The Regulars had nicknamed Lyon “the Little Red Head,” and the sight of him, riding at the head of the army as drums sounded and flags were unfurled, was inspiring. The First Iowa probably followed, for Lieutenant Colonel William H. Merritt recorded the time as 6:00 P.M. when his Iowans “united with the forces at Springfield and commenced to march to Wilson’s Creek.” As the column moved out, Lieutenant Colonel Andrews noted that his own Missouri regiment joined the line of march at 6:30 P.M.19

Heading west, the column initially trudged past cornfields lining both sides of the road, but the men soon emerged onto Grand Prairie, with its rolling fields of grass and scattered trees. It was not a pleasant march. Although the setting sun shone directly into the soldiers eyes for only a short time, the shuffling of hundreds of feet kicked up a cloud of thick dust, enshrouding the men in a gloom that exceeded mere darkness. To help conceal the movement, Lyon had directed that noise be kept to a minimum. The hooves of at least some of the cavalry horses were wrapped in cloth up to the fetlocks, and blankets were tied around the wheels of the artillery to muffle the rumble of the gun carriages, limbers, and caissons.20

The Regular Army units maintained proper silence, but discipline was not enforced in some of the volunteer units, at least during the early phases of the march. From time to time the lyrics of various camp songs broke out along the column. Perhaps the men sought to release tension, but it is just as likely that they were excited by the prospect of finally coming to grips with the enemy that had eluded them for so long. Osterhaus’s Germans sang “Morchen Rote,” while the First Iowa intoned one of its favorites:

So let the wide world wag as it will,

We’ll be gay and happy still.

Gay and happy, gay and happy,

We’ll be gay and happy still.

The Iowans sang so loudly that some feared the Southern outposts might hear them, yet the Kansans, not to be outdone, belted out “Happy Land of Canaan” at the top of their lungs.21

Those not singing passed the time discussing various subjects. One soldier noted that Sam Wood of the Rangers “was chewing a paper wad as usual, and talking Kansas.” Colonels George Deitzler and Robert Mitchell, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Blair, and some of the company captains “were moving back and forth along the column giving orders, interchanging views, visiting, chatting with the men, and having a good time generally.” Major John A. Halderman of the First Kansas “was working on a series of lurid battle cries which were received with great approval by the hilarious crowd.”22

On a more serious note, the Iowans and Kansans also traded messages to give loved ones back home if they did not make it through the impending fight. Some gave detailed instructions on what material they wanted their coffins to be made of, while others exchanged personal items. Lieutenant Levant Jones (who had only about twelve hours to live) gave away a “beautiful bay mare” named Dolly that he had acquired during the campaign and had planned to take home to his wife. The troubled officer requested that word be sent “to all his friends in Kansas that they would find him at Wilson Creek!” When things became too serious, Charles F. Garrett, a sergeant in the Scott’s Guards of the First Kansas, would remark how the most difficult items for him “to part with were his ‘g-g-g-graybacks.’”23

After covering nearly six miles, the column moved south off the road. If any of the Federals saw the lightning or heard the thunder that indicated rain was falling on the distant Southern camps, they left no record of it. No rain fell on Lyon’s column. With the change of direction and enveloping darkness, the role of the volunteer scouts took on greater importance. Now at the mercy of the guides, the Federals followed local byroads or trails leading to a point north of the Southern army’s camp. As the column moved south, closer to Wilson Creek, it left the gently rolling terrain of Grand Prairie and entered rougher, hillier country of ravines and dry washes that fed into the creek from the west. A soldier from Emporia, Kansas, wrote that the men maintained “comparative cheerfulness” despite the tedious march. Ware recalled that the column moved only “short distances from 20 to 100 yards at a time, and kept halting and closing up, and making very slow progress.” The moon was a slender, waxing crescent, providing little illumination, but they could still see for a short distance by starlight, even with scattered clouds.24

Around midnight Lyon reiterated his order for strict silence in the ranks. When the Federals halted about 1:00 A.M., they could see the glow of the enemy’s campfires beyond the hills in the distance, and the sounds of braying mules occasionally drifted across the prairie. The Federals were surprised to find no outposts. They could not have known, of course, that the Southern pickets had been withdrawn early on the evening of the ninth in preparation for the attack on Springfield but had not been reestablished after rain postponed the movement. As everything had gone as planned, the Federals lay down to rest, waiting for dawn to approach so their attack could be coordinated with that of Sigel’s distant column.25

The main body of Lyon’s force rested on the farm of Milford Norman. Although this placed the leading units less than two miles from the Southern camp, the column itself was about a mile and a half long, which means that the men at its tail end still faced a considerable march. This was an inevitable element in military movements, but the difference in time it would take for the first and the last man in Lyon’s column to reach the battlefield would have a profound effect on the day’s events.26

As soon as the order to rest was given, the Regulars destroyed Norman’s fences, dragging the rails down to use as pillows. The men of the Burlington Zouaves lay down on a large rock. Ware recalled that, having become chilled in the damp night air, “the radiating heat that the rock during the day had absorbed, was peculiarly comfortable.” A soldier in the Second Kansas later wrote that “when we halted . . . the men lay down for a few hours rest, with all their accoutrements strapped around them, and their guns in their hands.” Lyon shared a blanket with Schofield, reclining between two rows of corn, while the rest of the staff stretched out nearby. The chief of staff later remembered that Lyon seemed depressed as he reflected on the failure of their department commander, General Frémont, to understand the importance of holding southwestern Missouri. Frémont was clearly willing to abandon the region without a fight, and Lyon feared that he “was the intended victim of a deliberate sacrifice to another’s ambition.” Nevertheless, he determined to fight, asserting, “I will gladly give up my life for victory.”27

South of Springfield, at Camp Frémont, Colonel Franz Sigel prepared the Second Brigade for its role in the impending battle. His command was composed of three units: eight companies of Third Missouri Infantry, nine companies of the Fifth Missouri Infantry, and the six pieces of artillery of Backof’s Missouri Light Artillery.28

The Third Missouri was Sigel’s own unit, formed initially from the Turnverein and other German Americans in St. Louis. As Sigel was responsible for the entire brigade, command of the regiment fell to Lieutenant Colonel Anselm Albert. A native of Hungary, Albert had received a military education and served as an army officer before resigning in 1845. Three years later he joined the fight for Hungarian independence. When the revolution failed, he fled to Syria. Sailing to America, Albert landed in New Orleans, moved up the Mississippi, and settled in St. Louis, where he became caught up in the outbreak of civil war. The regiment he led was not as large as it might have been. Rifle Company B had been captured at Neosho in July—a loss of 94 officers and men. Then, on the twenty-fifth of that month, the regiment lost another 400 members, who had been ordered to St. Louis for discharge due to the expiration of their ninety-day enlistments. By August 4 the regiment was down to only 700 effectives, many of whom were recent recruits still learning to drill.29

Colonel Charles E. Salomon, who commanded the Fifth Missouri, was, like Sigel, a native of Germany and a veteran of the fighting in 1848. He, too, had escaped to America, settling in St. Louis. The Fifth brought nine of its ten companies to southwestern Missouri, initially about 775 officers and men, but on August 4 Salomon listed regiment strength as 600. The diminution was probably caused by both the expiration of enlistments and men lost to illness. Worse still, the two regiments apparently lost an additional 300 members on the very eve of the battle (Sigel’s after-action report gives their combined strength as only 900). Existing records do not indicate whether these men departed because of expired enlistments or remained in Springfield as part of the covering force there. In either case, they were not available for the upcoming fight.30

Conditions in the artillery were even more disturbing. Backof’s Battery contained two brass 6-pound guns and four 12-pound howitzers, but most of its original gunners had departed at the expiration of their terms. Now most of its gunners were men from the Third Missouri Infantry who had had “only a few days instruction.” Finally, attrition among officers had been particularly severe due to resignations, transfers, and illnesses. Overall, Sigel’s brigade had only one-third as many officers as needed. Indeed, some companies had no officers at all, command falling to the senior sergeant.31

Between 4:00 and 5:00 P.M. Sigel received word from Lyon to be ready to begin his phase of the operation at 6:30 P.M. To provide mounted assistance, Company I, First U.S. Cavalry, and Company C, Second U.S. Dragoons, were transferred from Sturgis’s First Brigade to the Second Brigade. Captain Eugene Asa Carr, who was still free from arrest thanks to the continuing crisis, led the sixty-five members of Company I, First U.S. Cavalry. A native of Erie County, New York, he entered the U.S. Military Academy at age sixteen and graduated nineteenth out of forty-four in the class of 1850. Assigned to the Regiment of Mounted Rifles, he spent a good portion of the 1850s on the frontier, saw some combat with Indians, and was wounded in 1854. Between 1856 and 1857 he was involved in the army’s feeble attempts to bring peace to “Bleeding Kansas.” Promoted to captain in 1858, Carr was assigned to the famous First U.S. Cavalry Regiment and participated in actions against the Kiowa and Comanche. Lieutenant Charles E. Farrand commanded the sixty troopers in Company C, Second U.S. Dragoons. A native of New York and an 1857 West Point graduate, he spent the years prior to the Civil War in the Seventh and First U.S. Infantry regiments. He was assigned to the dragoon company while stationed at Fort Leavenworth in 1861, probably as a result of the absence of the unit’s officers.32

With the artillery, Sigel’s brigade had about 1,100 officers and men: 900 infantry, 125 troopers, and 85 artillerymen. Local civilians C. B. Owen, John Steele, Andrew Adams, Sam Carthal, and L. A. D. Crenshaw volunteered to serve as guides.33

At 6:30 P.M. the brigade marched south out of its camp down the Yokermill Road, Carr’s cavalrymen heading the column while Farrand’s dragoons guarded the rear. After crossing the James River and covering about five miles, the column moved southwest, probably following the old Delaware Trace Road. As the brigade moved through woods and past farms, the drizzle that caused the Southerners to cancel their own attack fell on the tramping men. The rain did not last long, but with almost no moon and scattered clouds, it was difficult to see the way. Only “with great difficulty” did the units manage to avoid getting lost or separated. Private Otto Lademann of the Third Missouri recalled: “On we marched in dead silence, smoking was prohibited, no commands were given aloud, a subdued, undellnable clanking of our arms and the rumbling of our artillery carriages being the only sounds emanating from our column.”34

As the lead unit, Carr’s command was ordered to seize anyone along the route who might alert the enemy to the Federal advance and to place guards at houses in the area so word could not be sent to the Southern camp after the Federals passed by. Around 11:00 P.M. Sigel halted the brigade for three hours of rest. The march resumed at 2:00 A.M. As the troops neared Wilson Creek and the Southern camps around 4:30 A.M., they captured about forty Southerners who were out foraging. Sigel turned them over to Company K of the Fifth Missouri, which had been assigned the task of guarding prisoners. Farrand spoke to one of the Southerners, who told him that reinforcements from Louisiana were expected and they had assumed the approaching Federals were those troops.35

The civilian guides had led Sigel’s command to a point close to Wilson Creek, just below where Terrell Creek joined the stream. At 5:00 A.M., around sunrise, the dragoons were ordered to the head of the column. Farrand led his company to its assigned position on the left, while Carr’s troopers took the right. Sigel rode with Carr as his company moved up onto a long hill that towered above the creek’s eastern side. From this high ground the two officers had a commanding view of the unsuspecting Southern cavalry camps that blanketed the fields on the Sharp farm along the creek’s western side.36

Sigel’s accomplishment was stunning. Thanks to the excellent performance of the First Cavalry, it appeared to the Federals that no word of their approach had leaked out. Despite darkness and unfamiliar terrain, Sigel had moved his force to a point where he was in a position to inflict terrible harm on the enemy. Two drawbacks remained, however. He was severely outnumbered and had no means of communicating with Lyon. If anything went wrong with the main column’s attack, Sigel’s supporting column faced not merely defeat but outright destruction. There was nothing for the Union soldiers to do except await the dawn.