Chapter 13

My Boys Stood It Like Heroes

Early on the morning of August 10, General James S. Rains was in his headquarters near Gibson’s Mill, discussing events of the previous night with Dr. John F. Snyder. Although a physician, Snyder was also a lieutenant colonel and the ordnance officer for Rains’s Division of the Missouri State Guard.1 As the two men conversed, a number of empty forage wagons thundered into camp. The wagoneers brought startling news, for while moving out onto the prairie north of camp they had observed a large column of the enemy. Rains immediately ordered Snyder to “ride up there and see what is the matter.” Within a few minutes, Snyder had Lyon’s column under observation. The Union force was actually quite small for its daring mission, but Snyder lacked military experience. He had seen very few of the Federals to date, and their numbers stunned him. He raced back and informed Rains that the enemy’s infantry, cavalry, and artillery blanketed the prairie. Ordered to repeat his message to Sterling Price, the colonel spurred his horse, galloping toward the headquarters of the State Guard commander, at the Edwards farm, about a mile to the south. Rains then dispatched a second rider to warn Ben McCulloch at the Winn farm, headquarters of the Western Army, just over one-half mile south.2

Neither the route that the forage wagons took nor their location when they spotted the Federals is known, but they inadvertently served as substitutes for the pickets that had been withdrawn the previous evening. The wagons probably followed a farm road that began on the left bank of Wilson Creek, across from Gibson’s Mill. This initially ran southwest into a ravine. Then, curving like a fish hook, it crossed the northern spur of the unnamed rise that in a few hours would earn the sobriquet “Bloody Hill.” Dropping off the spur, the road ran due north, past the 280-acre farm of Elias B. Short, and continued toward the Mt. Vernon Road, which Lyon had followed when leaving Springfield. The wagoneers apparently saw Lyon’s men to the northeast, at the earliest light, just after the Federals rose from their temporary rest at the Norman farm. Either chance or some undulation in terrain hindered the Federals from spotting the Southerners.

Nathaniel Lyon had resumed the advance around 4:00 A.M. To maintain the element of surprise, he avoided roads, turning his column due south to march cross-country. The prairie grass was wet with dew and there was a slight mist in the air. The Federals soon entered a long, low valley that provided some concealment, but as they expected to make contact with the enemy eventually, Lyon deployed Captain Charles Gilbert’s Regulars as skirmishers, while the main body marched in column of companies. After only a short time, they ran into a group of Southerners who fired a few shots before running away. Discipline in the Southern army was so poor that dozens of men had wandered from their camps. These men were merely foragers, but the Federals assumed that they were pickets, posted to give the alarm. Lyon therefore halted the column and formed its leading units into a line of battle. Captain Joseph Plummer’s battalion filed off to the left, Major Peter Osterhaus’s Second Missouri battalion took the right (singing “Morchen Rote,” as the need for silence was past), while Totten’s Battery, supported by Lieutenant Colonel Charles Andrews’s First Missouri, occupied the center. The march resumed, with the Federals maintaining a fairly rapid pace, but they encountered no more “pickets.” After following the valley for more than a mile, they discovered a farmhouse off to their right.3

The small white house with green shutters was home to the Shorts, relative newcomers who had moved to Missouri from Tennessee around 1851. Now in their late thirties, Elias and his wife Rebecca had six children, two young teenaged girls and sons ranging in age from four to sixteen. Their lives had already been thoroughly disrupted by the presence of the Southern army camped along Wilson Creek. Elias Short was a Unionist; as soon as he heard rumors of the Southerners’ approach, he moved most of his horses and cattle to a location northwest of Springfield to prevent them from falling into enemy hands. He was unable to save the honey from his fifty stands of bees, however, and his wife and daughters were frequently coerced into fixing meals for men who wandered over to their farm. Sterling Price eventually placed a guard at the house for the family’s protection, but this was withdrawn when the Southern army prepared to march on Springfield.4

On the morning of August 10, the Shorts rose at 4:00 A.M. Rebecca killed a chicken—the only one they had managed to save from the hungry Southerners—and the family was eating breakfast when suddenly their yard began to fill with Union soldiers, cavalry moving at a trot and the infantry at the double. As the children ran to the door to get a better look, they saw that these men were not coming south along the road, as one might have expected, but through the back fields, from the east. Yet no sound had betrayed them. The Shorts were victims of an “acoustic shadow,” a term used when people who should be able to detect noise fail to do so. It can be caused by thick woods, terrain features, wind, or “acoustic opacity” due to varying densities of air from location to location. A significant factor for the first time in the Civil War at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, this phenomenon was also reported at Seven Pines, Gaines’s Mill, Perryville, and Chancellors ville. In any case, the Shorts not only failed to hear the shots fired when Lyon’s men encountered the Southern foragers, they did not hear the 4,200 soldiers, ten pieces of artillery, and hundreds of horses of Lyon’s column until it reached their yard. Although a battle was obviously imminent, the Shorts remained in their home. Many years later, Elias’s son John, who was nine at the time of the battle, recalled that the sight of Lyon’s steady ranks and the general on his gray horse “filled my heart with joy.” He was certain that Price’s Missouri State Guard “would be wiped off the earth.”5

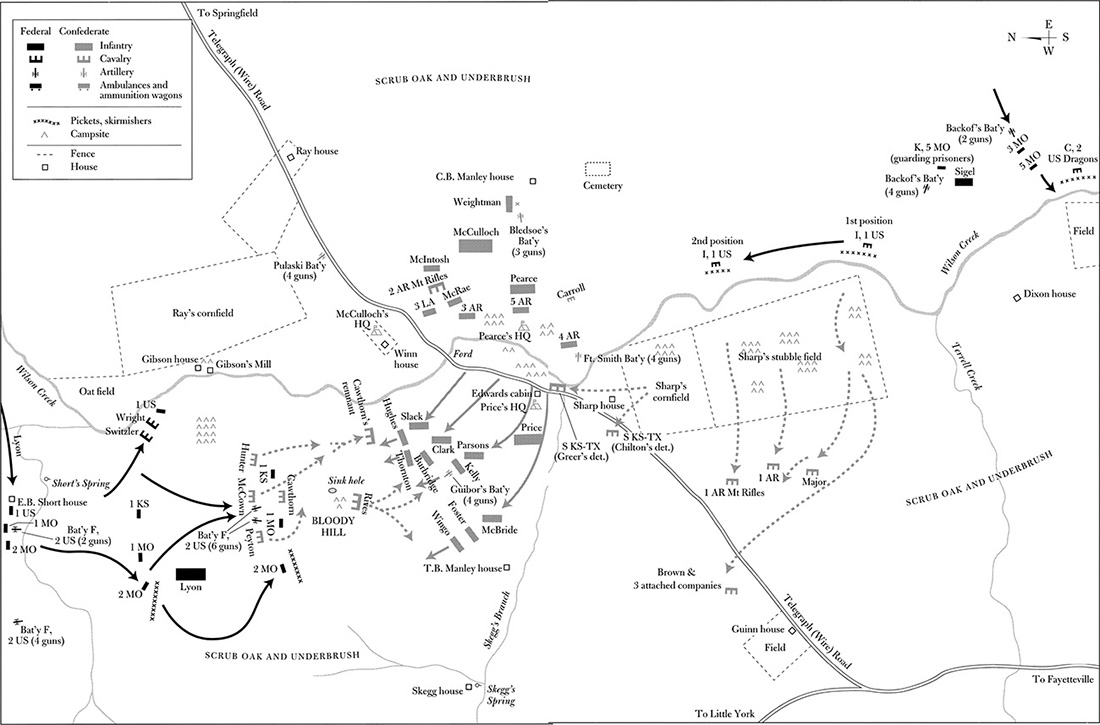

Lyon and Sigel attack, 5:00 A.M. to 6:00 A.M.

The first significant Southern response to Lyon’s approach did not result from orders given by Rains, but from the initiative of Colonel James Cawthorn, who commanded the mounted brigade of Rains’s Division. The foragers who fired on Lyon’s column were apparently Cawthorn’s men, as Cawthorn “became apprehensive and sent a patrol up the west side of Wilson Creek.”6 He was probably responding to the foragers’ report of the enemy’s presence, as the “patrol” he dispatched was actually a reconnaissance in force. It consisted of the 300-man regiment commanded by Colonel DeWitt C. Hunter, a thirty-one-year-old native of Illinois who had made Nevada, Missouri, his home. His unit had been raised in Vernon County, and its six companies bore names, such as Vernon Rangers and Vernon Guards, that reflected their strong community-level identification.7

When Hunter emerged from the ravine and onto the ridge forming the northern spur of Bloody Hill, he could see Lyon’s column entering the Short farm, not quite 450 yards distant. The shock must have been considerable, as all efforts on the Southern side had been concentrated on attacking Springfield. After sending word to Cawthorn of the enemy’s approach, Hunter formed his men in line atop the spur. Had the terrain been more favorable, he might have considered making a “spoiling attack,” deliberately sacrificing his unit to throw the enemy off balance, impede its movements, and buy time. But a ravine formed by a wet weather tributary of Wilson Creek separated the two forces. The slope leading down to it from the ridge top was steep and rocky, marked by a thin growth of hardwoods, and the conditions were about the same on the ravine’s northern side, where Lyon’s troops were taking position. Had Hunter charged, his command would have experienced difficulty maintaining its line, while facing a superior enemy possessing artillery support. Yet his defensive action had nearly the same effect as a spoiling attack, as the line he established on the high ground forced the Federals to halt. This gave Cawthorn time to sound the alarm and organize the rest of the division’s mounted troops, which were camped both in the Gibson’s Mill area and on the main portion of Bloody Hill itself.8

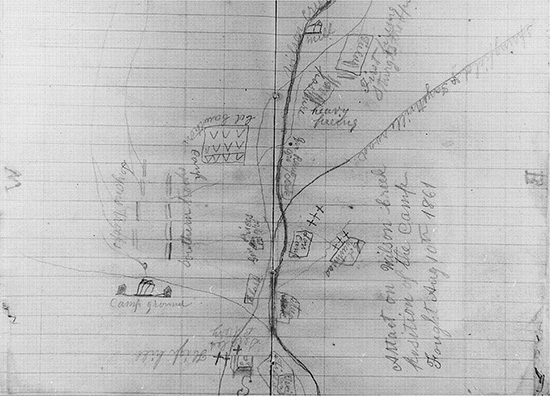

A map of the Wilson’s Creek battlefield from the diary of Captain Asbury C. Bradford, Polk County Rangers, Second Cavalry, Rains’s Division, Missouri State Guard, published here for the first time. The Sharp house is seen at left, Price’s headquarters at the Edwards farm in the center, and Gibson’s Mill at the far right. (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Hindsight suggests that Lyon’s leading elements could have easily brushed the Southern cavalry aside, but as the Union commander could not know what lay just over the ridge, he acted with understandable caution. On Lyon’s orders, Totten left a section under Lieutenant George Sokalski to maintain the center, then moved his remaining four guns along a trail to a small rise at the far right end of the Union line. From there he could support the advancing infantry by delivering enfilade fire against the enemy’s position atop the ridge. When Lyon gave the signal to advance, Sokalski’s guns fired the opening shots of the battle. It was no later than 5:00 A.M. and perhaps even a few minutes earlier.9

The Shorts had never expected a battle to begin in their yard. Elias was apparently anxious to stay, but once bullets began striking the house Rebecca insisted that the family leave. They headed northwest, walking five miles to a neighbor’s home, where they spent the day.10

As the Union formation considerably overlapped that of its opponent, the centrally positioned First Missouri met the most resistance. When word came to advance, Andrews sent Captain Theodore Yates’s Company H forward as skirmishers, while the rest of the regiment followed in column of companies. Once the skirmishers came under fire, Andrews reinforced Yates with Company B, led by Captain Thomas D. Maurice, and ordered the regiment into line. To their far left, Gilbert’s Regulars pushed through the rough terrain where the hillside sloped down to the creek.11

As the Southern horsemen were under artillery bombardment and outnumbered at least three-to-one, they gave way quickly, but not before inflicting the battle’s earliest casualties. These did not all occur on the front line. Like the rest of the reserve, the First Kansas was ordered to lie down, but something caught the attention of Lieutenant John W. Dyer of the Wyandotte Guards. When he rose up to look, a “ball struck him full in the mouth.” The bullet exited the back of his head, and without making a sound the officer “fell back dead.” Another stray bullet killed Shelby Norman, a seventeen-year-old private in the First Iowa’s Muscatine Grays.12

When Cawthorn heard the sound of Hunter’s engagement, he formed the rest of his mounted brigade, at least six hundred strong, into position on the crest of the main portion of Bloody Hill to create a second line of defense. He apparently did this on his own initiative, without waiting for orders from Rains. Colonel Robert L. Y. Peyton placed his regiment on the left, while Lieutenant Colonel James McCown aligned his troopers on the right. They dismounted to fight on foot, as they had at Carthage in July, sheltering their horses below the crest on the slopes behind them. When Hunter’s men retreated, they also found cover for their own horses, then joined Cawthorn’s line, extending it to the right. The position was good, but as one soldier in four held horses, fewer than seven hundred Missouri State Guardsmen stood in line between the enemy and the unprotected Southern camps.13

An 1880s photograph taken in what was once John Ray’s cornfield, the scene of fierce fighting. The view looks west toward Bloody Hill, which can be seen in the distance. (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

When Lyon reached the top of the northern spur of Bloody Hill, he was confident of inflicting a severe blow on his Southern enemies, remarking to Major John Schofield, “In less than an hour they’ll wish they were a thousand miles away.” From his position he was able to view Cawthorn’s abandoned camp at the bottom of the ravine to his front and left. He could also see, to his extreme left, some of the camps of other elements of Rains’s command near Gibson’s Mill. A mile away to the southeast, John Ray’s farmhouse stood in plain view beside the Wire Road. Because of the routes taken by Lyon’s and Sigel’s columns, the Southern army was now actually closer to Springfield than the attacking Federals. Therefore, before moving against Cawthorn’s men in his front, Lyon took steps to secure his left flank, even though it meant dividing his small command. He directed Plummer to take his battalion of Regulars, together with the mounted Home Guards of Captains Wright and Switzler, to the east side of Wilson Creek and “carry forward the left flank of the attack.”14

In continuing his advance, Lyon faced two challenges: the enemy immediately in his front and the remaining distance the Federals had to cross before they could accomplish their objective. After delivering supporting fire, Totten’s Battery had limbered up. The gunners, together with the rest of the infantry and mounted troops, had followed close behind the battle line as it swept up the northern spur of Bloody Hill. The Union column occupied so much space that its tail still rested on the Short farm. This was significant. The troops in the front of Lyon’s position would have to move about three-quarters of a mile, and those in the rear a full mile, before they could effectively deliver fire against the Southern camps. Under parade ground circumstances on flat terrain it might have taken the Federals forty minutes to move and deploy their entire force. As they faced both enemy resistance and rugged obstacles, there was not a moment to lose.

These considerations apparently influenced Lyon, for just after dispatching Plummer he decided to divide his force yet again. First, to press the attack, he called up Colonel George W. Deitzler’s First Kansas to strengthen his battle line, bringing it to a total of just over 1,650 men. When Deitzler received the order, he rode past his command, speaking “a few sharp emphatic sentences” that “electrified the spirits and hopes” of the men. He punctuated these words by standing up in his stirrups and exclaiming, “Boys, we’ve got them, d—m them.” Elated at the prospect of meeting the enemy at long last, the men from Atchison, Elwood, Lawrence, Leavenworth, and Wyandotte filed into line to the left of the First Missouri. Once they were in position, Lyon ordered the whole force forward. This time Totten’s guns followed close behind rather than deploying to assist the attack. Lyon apparently judged from his first encounter that artillery fire would not be needed to defeat Cawthorn.15

The distance from Lyon’s position on the northern spur of Bloody Hill to Cawthorn’s on the main ridge was about half a mile. So instead of following the Union battle line down into the ravine, the remainder of Lyon’s command moved southwest, traveling along farm roads to go around the head of the ravine. Although the distance to be traveled was over three-quarters of a mile, this maneuver made sense, as the troops would outflank Cawthorn on his left. The First Iowa, Lieutenant John Du Bois’s four-gun battery, Captain Frederick Steele’s battalion of Regulars, and Osterhaus’s Second Missouri battalion made the trek. Colonel Robert Mitchell’s Second Kansas acted as a reserve for the advancing battle line. It is not clear when the Kansans advanced, but they eventually occupied a position behind the crest of the hill, sheltered by its slopes. The horsemen of Wood’s Kansas Rangers guarded the right and rear. The location of Lieutenant Charles Canfield’s Company D, First U.S. Cavalry, is unknown, but the troopers probably served a similar function. The ammunition wagons and ambulances that had accompanied the column remained near the Short springhouse, located in the ravine below the house. The ambulances eventually moved to the ravine opposite Gibson’s Mill.16

The men of the First Kansas and First Missouri moved slowly, as the steepness of the ravine made it difficult to maintain their lines. But the issue was never in doubt. After a relatively brief exchange of fire they seized the crest, pushing Cawthorn’s troopers down the hill’s southern slope. Indeed, the impact of their attack was disproportionate to the casualties they inflicted. Perhaps because they could see that they would soon be outflanked, the Missouri State Guardsmen raced for their horses, and in the ensuing confusion men became separated. As a result, Hunter’s and Peyton’s units did not rejoin Cawthorn until much later that morning.17

Although successful, the Union advance took time. The Kansans and Missourians did not reach the crest until around 5:30 A.M. While waiting for the rest of Lyon’s column to join them, they could see a considerable portion of the Southern camps. Totten soon spotted the Pulaski Light Battery near the Winn farm, more than half a mile to the southeast. He had no way of knowing that the cannoneers in the distance were Captain William Woodruff’s men, whom he had helped to train in Little Rock only a short time ago. The Federals could also see many camps of the Confederates and the Arkansas State Troops on the east side of Wilson Creek. Because Bloody Hill was so broad, they still could not view Price’s headquarters or the majority of the camps of the Missouri State Guard. They did, however, notice a small group of cavalry to their right front attempting to form a line of defense. Both Totten’s Battery and the First Missouri hastened to respond.18

The Southern high command was utterly unprepared for Lyon’s attack. Around dawn Price had sent his adjutant, Captain Thomas L. Snead, to McCulloch’s headquarters to be apprised of his plans for the advance on Springfield. McCulloch failed to mention to Snead that several minutes earlier he had received word from Rains of enemy activity due north or that, in response, he had ordered his most trusted horsemen, Colonel Elkanah Greer’s Texans, to move from their camp at the Sharp farm to the ford of Wilson Creek on the Wire Road. He gave similar orders to Carroll’s Arkansas Cavalry company. McCulloch probably found Rains’s report hard to credit, as ever since “Rains’s Scare” at Dug Springs the State Guard horsemen had been the laughingstock of many in the army. He apparently planned to send the two cavalry units to investigate. When Snead arrived, McCulloch decided to confer with Price in person. He left his headquarters around 5:00 A.M. His departure was unfortunate. Had he remained for only a short time, he would have been able to view, in the distance, the opening scenes of the battle on the northern spur of Bloody Hill.19

It took McCulloch and his adjutant, Colonel James McIntosh, only a few minutes to reach the Edwards farm. William Edwards was a man of relatively modest means, a forty-one-year-old native of Tennessee whose wife, Mary, a year younger, was from Illinois. Residents of Missouri since at least 1841, they lived with their nineteen-year-old son James in what seems to have been a relatively rude cabin. They fared well, having increased their small holdings by purchasing an additional forty acres only three years earlier. The occupation of their farm by the Western Army was obviously an intrusion of almost unimaginable magnitude. Price was just sitting down to eat in the Edwards yard when McCulloch and McIntosh arrived. At his invitation they joined him for a breakfast of cornbread, lean beef, and coffee. Within minutes, John Snyder galloped into the yard, his horse flecked with sweat. Circumstances of an unknown nature had prevented him from arriving sooner, but he announced breathlessly that the enemy was “approaching with twenty thousand men and 100 pieces of artillery.”20 This wild report was not news to McCulloch, and he had already taken what he considered to be appropriate steps. Consequently, he instructed Snyder to return to his commanding officer saying, “Tell General Rains I will come to the front myself directly.” It was probably around 5:20 A.M., but the same acoustic shadow that had concealed Lyon’s approach from the Short family prevented the sound of the firing on the northern spur of Bloody Hill from reaching the Edwards farm, although the distance was less than a mile. Nor did the men eating breakfast there hear the first shots fired by Franz Sigel’s artillery against the Southern cavalry camped at the Sharp farm, one and one-quarter miles to the south. A few minutes later a second messenger arrived from Rains, announcing that “the main body of the enemy was upon him.” This was too much to ignore. At approximately 5:30 A.M., Price set out for Gibson’s Mill to confer with Rains, while McCulloch returned to his headquarters.21

As a result of the acoustic shadow, the 650 troopers of Benjamin A. Rives’s First Cavalry Regiment of Slack’s Division received a nasty surprise. Raised largely in Daviess, Carroll, Livingston, Ray, and Grundy Counties, these men had traveled more than two hundred miles from their homes north of the Missouri River under a colonel who was a physician in peacetime. Veterans of the fight at Carthage, their camp, located about three hundred yards south of the crest of Bloody Hill, marked the westernmost edge of the Southern army. For unknown reasons, the regiment’s drillmaster, Captain Watson Croucher, left camp early in the morning and blundered into the fighting on the hill’s northern spur. He soon returned with news that the enemy was approaching. Rives’s men had not heard the firing. Nor, because of the undulations and broad expanse of Bloody Hill, had they seen Cawthorn position his men just to the northeast only minutes earlier. Although the report was difficult to believe, Rives took no chances. He dispatched a patrol of twenty men to investigate and ordered the teams hitched to the regimental wagons. One man in six, rather than the usual four, led the horses down the hill to cover, while the remainder started forming into line. But before these assignments were completed, the patrol raced back into camp, confirming the enemy’s approach. Within moments, the Federals poured over the hilltop, just northeast of Rives’s camp.22

Andrews’s First Missouri, which was on the Federal right flank, shifted to face the Southerners. This created a gap of some sixty yards between it and the First Kansas, but Totten deployed his guns in between them, and both the Kansas infantry and the artillery opened fire. Rives described the incoming projectiles as “a tremendous shower of case-shot, grape, and minie-ball.” Fortunately for the Southerners, the Federal aim was miserable. Lieutenant Colonel A. J. Austin and two privates were killed instantly, but the regiment suffered no further casualties when, on Rives’s orders, it withdrew. In their panic to escape, Rives’s men split into two parties that were not reunited until the end of the battle. The Federals may have caused few deaths, but the element of surprise allowed them to reduce the combat effectiveness of their enemy substantially. With the crest of Bloody Hill clear, Lyon needed only to wait for the arrival of the troops he had sent around the head of the ravine before advancing to a position from which he could attack the Southern camps. But, as Andrews wrote, the Federal movement “unmasked one of their batteries.”23

Woodruff’s Pulaski Light Battery was not deliberately masked or hidden. It had simply gone unnoticed by many Federals up to this time. The Arkansans were camped just northeast of the Winn farmhouse, on a lightly wooded ridge that paralleled the Wire Road between the Ray farm and Wilson Creek. The southwestern end of the ridge commanded the ford. The artillerymen had risen early that morning to prepare a breakfast of green corn gathered from nearby fields the previous day. Just as they finished, “a great commotion was observed . . . in a direction northwesterly.” This was Cawthorn’s retreat. As Woodruff had seen the Missouri State Guard panic before, he was “not greatly disturbed,” yet as a precaution he ordered his gunners to their pieces and the drivers to their horses. No instructions came from headquarters at the Winn residence, because McCulloch had departed to meet with Price. After a short time, the Arkansans saw a battery rush into view atop Bloody Hill, more than half a mile away, unlimber, and fire. This was followed by “a second battery or section” that was soon in action not far from the first. Woodruff apparently sensed that the situation of the Southern army was critical. In fact, as he watched the Missouri State Guard being driven off Bloody Hill by the Federals, he was reminded of the Egyptians chasing the Israelites in the Book of Exodus. He had been awaiting orders, but, “satisfied the situation was grave,” he acted on his own responsibility.24

As the caissons rumbled to the rear, the unit’s two 12-pound howitzers and two 6-pound guns spun into battery. This “unmasking” activity attracted the attention of the Federal artillery, which immediately began to target them. Woodruff recalled proudly that the enemy was able to get off no more than four shots before the Pulaski Battery returned fire. Yet he knew that speed was not as important as accuracy and that artillery tended to shoot high. Because the battery had never been in action and ten of his soldiers were under the age of seventeen, he had standing instructions that in the first battle an officer would carefully direct each piece. Lieutenant Omer Weaver served Gun No. 1. Lieutenants William W. Reyburn and Lewis W. Brown were stationed at Guns No. 3 and 4, respectively, while Woodruff took Gun No. 2, to be near the center of the battery. Woodruff’s gun fired first, and soon case shot and shells from the whole battery were screaming toward Bloody Hill.25

The willingness of junior officers to take independent action served McCulloch’s army well on August 10, as it bought the Southerners badly needed time. Cawthorn had dispatched Hunter’s reconnaissance in force, which delayed the Federals on the northern spur of Bloody Hill. Cawthorn’s own battle line on the main ridge, together with that of Rives, further slowed them. Finally, Woodruff’s counterbattery fire helped to fix the Federals in place on Bloody Hill once they finally reached it. As a consequence, Lyon began to lose the initiative. Although speed was essential, the Union commander acted cautiously. Terrain probably affected his evaluation of the situation in a major way. Totten’s guns had a wealth of long-range targets. In addition to firing at the Pulaski Battery, they began striking the camps of the Confederates and the Arkansas State Troops on the far side of Wilson Creek. They also dropped a few shells onto the Missouri State Guard near the Edwards cabin. Although the range was shorter, the latter shots were fired blind, for effect, as the breadth of Bloody Hill, together with the occasional thickets dotting its slopes, prevented the Federals from seeing the enemy units closest to them clearly. Indeed, Lyon had no idea what lay directly in his front. His encounter with Rives’s men, just after driving Cawthorn away, may have been particularly unnerving. For all he knew, the hill’s broad expanse of folds and undulations might conceal other Southern encampments. Rather than continue forward, he began strengthening his existing battle line, feeding in troops as they arrived on his right flank and rear, via the farm roads leading around the head of the ravine.26

Totten’s Battery formed the center of the Union line, which faced due south. Six companies of the First Kansas, under Colonel Deitzler, were posted just to its left. The men of the First Iowa, many of whom had shed their coats and haversacks, marched at the double-quick into position on their flank, forming the far left of Lyon’s force. Lieutenant Colonel Merritt, who commanded in the absence of Colonel Bates, completed their multicolored appearance. Riding a white horse and wearing a white coat, he was particularly conspicuous. The remaining four companies of the First Kansas, commanded by Major John Halderman, were just to the right of Totten’s Battery. The line was extended by Andrews’s First Missouri and Osterhaus’s small battalion of the Second Missouri. Lyon apparently became caught up in aligning the infantry, for when Du Bois reached the hilltop with his four guns, he found no one to direct his placement. Making an astute assessment of the situation, he stationed his battery eighty yards to the left and rear of Totten and targeted the Pulaski Battery, whose fire was greatly impeding the Federal deployment. Steele’s small battalion of Regulars moved to support Du Bois. Lyon’s line of battle soon contained ten pieces of artillery and approximately 2,800 infantry.27

It took the Federals until almost 6:30 A.M. to consolidate their position on Bloody Hill. Although their artillery kept up a steady shelling that panicked some of the enemy, the Southerners were beyond rifle range. Despite the Federal fire, the Southern leaders were able get most of their men out of camp and into formation. Because of the position of the Missouri State Guard camps, the task of stopping Lyon fell initially to Sterling Price. A farm road ran directly from the Edwards place up to the summit of Bloody Hill. Price presumably followed this as he “rode forward instantly towards Rains’s position” on the battlefield. Haste did not cloud the Missourian’s presence of mind, however. Prior to leaving his headquarters, he had dispatched messengers to Generals Slack, McBride, Clark, and Parsons, ordering them to follow with their infantry and artillery as rapidly as possible. Price’s hope of reaching Gibson’s Mill was quickly dashed. After riding only a few hundred yards, he reached a clearing and “came suddenly upon the main body of the enemy, commanded by General Lyon in person.” Lyon was wearing a plain captain’s coat rather than his general’s uniform, but Price apparently had no difficulty recognizing him. Seven weeks had passed since their last meeting at the Planters’ House hotel. In the interval, the Missouri State Guard had more often than not retreated in the face of the Connecticut Yankee’s “punitive crusade.” Whether the Missourians retreated now depended in no small part on Price, who rode back down the hill to gather his forces.28

Because the Federals possessed the high ground, Price began by rallying a portion of Cawthorn’s command at the base of Bloody Hill, where the contours of the southern slope blocked the view of Lyon’s infantry and artillery. It took some time for other units of the State Guard to join him, as each one had to form up and march to the scene. Many of the men were understandably startled to find themselves under attack. The infantry of Slack’s Division was located between the Wire Road and Wilson Creek itself, a prime campsite as the trees lining the creek offered shade. Corporal Alonzo H. Shelton recalled that the men were at breakfast when they heard the boom of a cannon. This was instantly followed by a shell that “whistled along down the road close to where we were eating.” Shelton was a member of Captain Gideon W. Thompson’s Company B, from Platte County, which bordered the Missouri River north of Kansas City. It was one of three companies from that region organized into an Extra Battalion under Major John C. C. Thornton and assigned to Colonel John T. Hughes’s First Infantry. Many of these men had no weapons, so when the firing began they were ordered to the rear with regimental wagons. Shelton noted that many refused. Staying with the command to replace casualties, they “watched their chance to get a gun, and then went into the fight.”29

Hughes led these men into line on Cawthorn’s left and acted as overall commander of the two units, which had a combined strength of 650 men. They were in good hands. A Kentucky native but Missouri resident since the age of three, Hughes was a veteran of the Mexican War, having served in the First Missouri Mounted Volunteers. Although a prosperous businessman and slaveholder, he was also a Whig, favoring gradual emancipation. But after the “Camp Jackson Massacre” he became one of the state’s most vocal critics of Lyon and the Lincoln administration, whose actions he considered tyrannical and unconstitutional. Thus he brought both zeal and energy to the State Guard. “Missouri is my country,” he boasted, labeling its defense the “holy cause of liberty.”30

Colonel John Q. Burbridge’s 270-man First Infantry from Clark’s Division soon moved into line on Hughes’s left. The regiment had camped between the Wire Road and the base of Bloody Hill. Private Joseph Mudd of the Jackson Guards recalled that it took no more than twenty minutes for his own company to move “at quick step in line of battle.” Although the remainder of Burbridge’s men took a bit longer, Mudd remembered with pride that, considering their “want of drill and real discipline,” the Missourians “got to the firing line in good shape.” Another member of the regiment, however, was forced to scramble. Rising around dawn, Henry M. Cheavens helped some friends butcher a cow some distance from camp. On his way back he heard a rumor that the Southern army was “surrounded by Lyon’s 1/2 mile distant.” He refused to believe it, but on arriving in camp he saw his company being called into line. After washing his hands, he loaded his Mississippi rifle and hurried off without breakfast.31

Colonel Joseph M. Kelly marched the 142 soldiers of his battalion onto Burbridge’s left. These few men were the only infantry in Parsons’s Division, but the core of Kelly’s unit was formed by his own blue-coated, well-drilled Irishmen, the Washington Blues of St. Louis. They were followed by the four 6-pound field guns of Captain Henry Guibor’s First Light Artillery. Two infantry units from McBride’s Division, totaling 600 men, formed the far left flank of the initial battle line. Colonel John A. Foster’s men were just to the left of Guibor, while Colonel Edmond T. Wingo’s soldiers held the extreme left.32

These units added over 1,600 State Guard infantry to Price’s line. Also, Rives and about 70 of his dismounted troopers joined Hughes’s Infantry, while additional elements of his command fell in with other regiments as they moved into line. By around 6:30 A.M. Price may have had as many as 2,000 infantry and dismounted cavalry in line, plus Guibor’s Battery. Once these men were in position, they moved up the slopes to challenge Lyon for possession of Bloody Hill. The battle was now joined in earnest, and the level of fire soon grew so intense that it was heard as far away as Springfield.33

While Price established his battle line, McCulloch and Bart Pearce organized their commands on the eastern side of Wilson Creek. As was the case throughout the Southern camps, most members of the Arkansas State Troops were cooking breakfast when the battle erupted. Arising early, Pearce sent Captain Charles A. Carroll, whose forty-man Arkansas Cavalry company acted as the general’s escort and bodyguard, to McCulloch’s headquarters for orders. Carroll arrived just after McCulloch received his first report from Rains, and McCulloch ordered him to bring his company forward for a reconnaissance. But when Carroll returned to the Arkansans’ camps, he discovered that Pearce already knew of the enemy’s advance. This was another ironic example of the Southern army benefiting from its lack of discipline. In violation of orders, two of Carroll’s own men had left camp before dawn, heading east up a ravine in search of a spring. They probably followed a road that led from the vicinity of Pearce’s camp past the Manley farm. Both Caleb Manley, age fifty-seven, and his wife Rebecca, forty-nine, were natives of Virginia. They struggled to support three sons and a daughter, ranging in age from ten to eighteen, in very modest surroundings.34

It may have been close to the Manley place that Carroll’s soldiers encountered an unidentified group of Federals who fired on them. The Southerners fled precipitously, and it was approximately 5:00 A.M. when they returned to camp and informed Pearce that the enemy was advancing past the flank of the Western Army. This panicky assessment was both misleading and inaccurate, as Sigel was at that point already much farther south, preparing to attack. Carroll’s men had apparently encountered pickets detached by Sigel to protect the rear of his column. Pearce immediately sent the senior of the two miscreants, a Sergeant Hite, to warn McCulloch. Hite left only moments before Carroll arrived with news of the peril from the north. The Southern army was obviously in danger from at least two directions.35

Pearce was familiar enough with the surrounding terrain to anticipate the enemy’s possible avenues of approach. The day before he and Colonel Richard H. Weightman of the Missouri State Guard had conducted a thorough reconnaissance, probably to determine alternative routes to Springfield so the entire Southern army would not have to utilize the Wire Road for its planned attack. Placed unexpectedly on the defensive, Pearce chose his ground quickly. Perhaps because he heard Woodruff’s opening guns, he ordered the Pulaski Light Battery to hold its position at the Winn farm and sent Colonel John Gratiot’s Third Arkansas Infantry to its support. Gratiot’s regiment included a prewar militia unit, the bluecoated Van Buren Frontier Guards. They were armed with rifles and he could depend on them to be steady. Two days earlier one member of the Third, Ras Stirman, had written his sister that he expected to enter battle “with a brave heart trusting God for help.” Stirman asserted that faith had entirely removed his fear, but as most of the Arkansans were facing battle for the first time, it is unlikely that many shared his composure.36

To meet the threat to the flank and rear, Pearce ordered Captain John Reid to place the four guns of his Fort Smith Light Battery on a slight hill a few hundred yards east of the Arkansans’ camps. Colonel Tom Dockery’s Fifth Arkansas Infantry remained adjacent to the artillery, while Colonel John Walker’s Fourth Arkansas Infantry took up a position just north of them, in case the enemy approached from the road leading to the Manley farm. Because Walker was ill, Pearce’s adjutant general, Colonel Frank A. Rector, took his place. Finally, Pearce spread out Carroll’s Arkansas Cavalry as pickets, guarding Reid’s battery against surprise.37

Pearce’s hurried dispositions demonstrate the dilemma of the Southern forces, as well as the advantage the Union gained from both the element of surprise and by attacking in two columns. Pearce prepared to defend the high ground above his camps from three directions: north, east, and south. As an immediate response, his action is understandable, but it moved the Arkansas State Troops out of supporting distance of much of McCulloch’s Confederate brigade and all of Price’s Missouri State Guard. Pearce also lost contact with his cavalry units camped at the Sharp farm, and he made no attempt to use Carroll’s Arkansas Cavalry company for reconnaissance. Had he done so, he might have discovered that the ridge just south of his camp overlooked the farm. If the Fort Smith Light Battery had been placed on this higher ground with its better view, it might have greatly influenced the portion of the battle that soon unfolded in that area. But Pearce remained passive, making no effort to locate the Federals or understand their movements. He kept Reid in a position of limited visibility, his guns remaining silent for over an hour for lack of targets. Nor was the infantry well utilized, at least initially. While the 500 men of Third Infantry spent “some hours under a fire of shot and shell” supporting the Pulaski Light Battery, the remainder of the Arkansas infantry, some 1,200 men, stood idle in safety for at least two hours. Indeed, the 550 men of the Fourth Infantry never fired a shot in the battle and suffered no casualties. Pearce rode north to check on Woodruff, encountered McCulloch, and presumably consulted with him. Apparently, neither commander considered any immediate offensive role for the Arkansans.38

As Pearce was positioning his troops, to the north Plummer struggled to accomplish the mission Lyon had assigned him: to cross Wilson Creek and press the left flank of the Union attack toward the Wire Road. Instead of descending the northern spur of Bloody Hill to utilize the ford just south of Gibson’s Mill, he moved east to join Gilbert’s Regulars, dropping down the “rocky hillside.” He overtook Gilbert “in a deep jungle” where “he had been checked by an impassible lagoon.” Wilson Creek was not deep, but Gilbert had stumbled into an area of backwater between two dams built by John Gibson to provide a sufficient flow to operate his mill. “Much time was consumed in effecting the passage of this obstacle,” Plummer recalled. According to one soldier, on the far bank the Federals ran into another “jungle of willows and reeds, and had to push and pull each other through, our shoes being filled with water and sand.”39

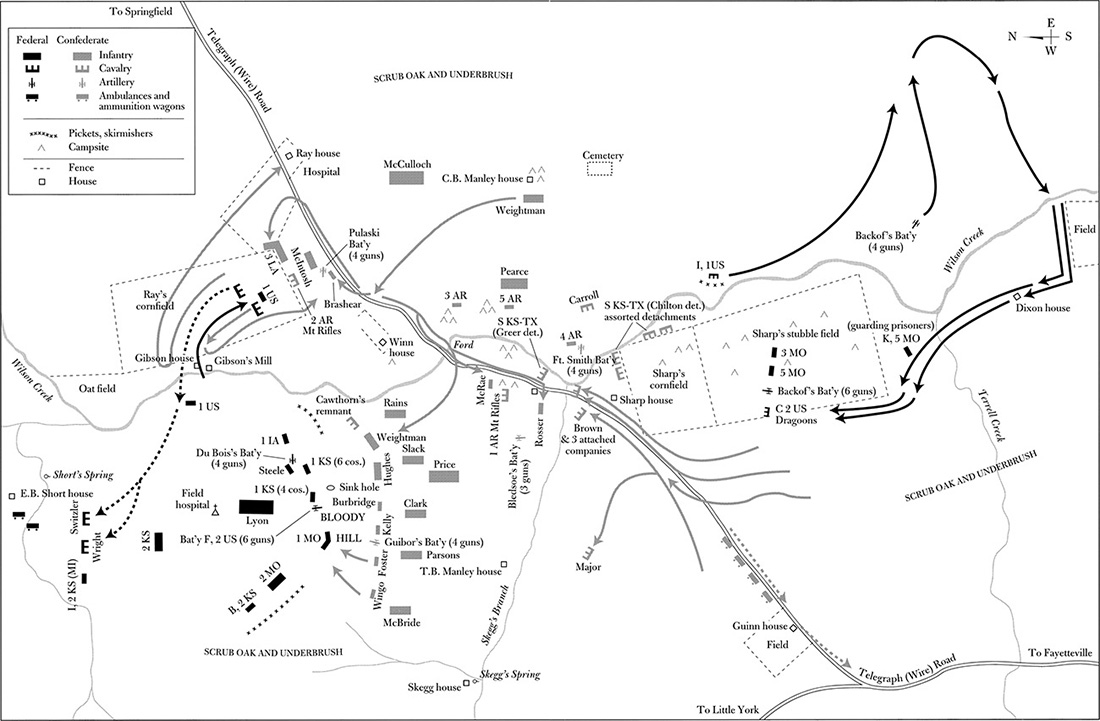

Bloody Hill, the Sharp farm, and the Ray cornfield, 6:00 A.M. to 7:00 A.M.

John Gibson may have wondered about the safety of his property as the Federals approached. A man in his fifties, he and his wife Martha were natives of Tennessee who had moved to Missouri in 1854. They arrived with their seven children (two boys and five girls), purchased eighty acres adjacent to Wilson Creek, and constructed both a mill and a substantial home. By 1861 only their youngest daughter, twenty-two-year-old Nancy, still lived with them, and they probably took in boarders. Missouri had been good to them, and their holdings, which included a few horses and cattle and a substantial field of oats, were valued at $3,000.40

Luckily for the Gibsons, their oats had already been harvested. Plummer’s force pushed quickly through their land and, around 6:30 A.M., entered the northern end of John Ray’s adjoining property. After crossing a rail fence, the Federal soldiers found themselves in a field of “Indian corn of moderate height.” By this time the main column under Lyon had reached the crest of Bloody Hill and was beginning to engage the Missouri State Guardsmen advancing up the slopes toward them. Plummer consequently began moving as fast as possible to bring the overall Union attack into alignment. The ground rose steadily as the Federals advanced toward the Ray farmhouse, but both the standing corn and occasional undulations in the ground hampered their view. As the battalion advanced, it suddenly came under fire from the left. Although some of the bullets clipped ears of corn and others ricocheted from bayonets, no one was injured. These shots probably came from some of Rains’s men camped on the east side of Wilson Creek who had fallen back during the opening phase of the battle. Although Plummer described this fire as “light and easily quelled,” the halt he made to deal with it slowed his already tardy maneuvers still further, allowing the Southerners even more time to respond to the Union advance.41

As Plummer approached the center of the cornfield, he observed the Pulaski Light Battery delivering enfilade fire against the main Union line across the valley atop Bloody Hill. He responded by leading his command toward the battery “with the intention of storming it, should the opportunity offer.”42 Unfortunately for the Union officer and his command, the opportunity never materialized.

Possessing a sufficient supply of ammunition, Woodruff’s gunners had maintained a steady fire since the opening of the battle. They also endured the incoming shells of the Federal guns. In a letter written the day after the battle, Woodruff stated with pride, “My boys stood it like heroes—not a man flinched, although the balls came like hail stones for all that time.” Yet he added, without any apparent sense of incongruity, that only two of his men were struck while the battery was in its initial position. To the inexperienced Arkansans the counterbattery fire directed against them seemed extraordinarily heavy, as exploding shells could have a psychological impact disproportionate to their actual lethality.43

The first casualty in the Pulaski Light Artillery was the popular young lieutenant, Omer Weaver, who was mortally wounded by a round that struck him in the chest and nearly tore off his right arm. Weaver remained conscious for some time, and after his comrades carried him to cover he may have thought about his family and clandestine sweetheart Annie back in Little Rock. Woodruff called for a surgeon, but the artillerist had no time to spare for Weaver, as he soon sighted Plummer’s approaching force, about half a mile distant. The captain sent a messenger to warn McCulloch, who had returned to the area of the Winn farm.44

Back at the Western Army’s headquarters, McCulloch began forming his Confederate brigade. He knew that Price’s Missourians were responding to the threat from Bloody Hill, and after consulting with Pearce he was assured that the Arkansas State Troops would soon be in good defensive positions. Messengers informed him, however, that chaos reigned at the Sharp farm only a short distance down the Wire Road. The enemy’s attack on the Southern cavalry forces camped there had created absolute panic. McCulloch had apparently just decided to shift all of his Confederate troops to quell the danger in his rear when Woodruff’s message alerted him to the more immediate peril posed by Plummer’s advance. He therefore instructed his adjutant, Colonel James McIntosh, to take his own unit, the Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles, together with Lieutenant Colonel Dandridge McRae’s undesignated battalion of Arkansas infantry and the Third Louisiana, to oppose Plummer. McCulloch assisted in assembling this force before returning his attention to the remaining Confederates—the First Arkansas Mounted Rifles and the South Kansas-Texas Cavalry—and the crisis at the Sharp farm.45

As was the case elsewhere, the men of McCulloch’s Confederate brigade were calmly eating breakfast when the Union attack shattered their complacency. The Louisianans had arisen early, falling in at the sound of a bugle for roll call. They were then dismissed to prepare coffee. The peculiar acoustic shadow prevented them from hearing the opening sounds of the battle. Instead, the scurrying of couriers and the frantic movements of other troops first alerted them to impending action. When Colonel Louis Hébert ordered the Third Louisiana to reassemble, many of the men responded in such haste that they left their coats behind, changing the solid gray lines of the neatly uniformed unit to a multicolored appearance. The sense of danger combined with the thrill of finally confronting the enemy to produce tremendous emotional release among the soldiers. While ordering his own Pelican Rifles to fall in, Sergeant William Watson heard some of his men cry, “We are going to have it now, boys.” The regiment’s lieutenant colonel, Samuel M. Hyams, was in acute pain, suffering not only from his usual arthritis, but also from a recent kick to the knee “from a sore-backed Indian pony.” Nevertheless, he “in some way got on his horse” and followed Hébert. Lieutenant O. J. Wells of the Shreveport Rangers was equally determined. He had been on the sick list for weeks, having lost thirty-five pounds due to chronic diarrhea, but once the firing began he “staggered up” to his company and “stood at his post.”46

The 700 men of the Third Louisiana moved into position on the Wire Road. McRae’s Battalion, which numbered 220, formed behind them. McRae was deeply proud of the progress his men had made since their enlistment only weeks before. Although their weapons were of inferior quality, the unit had gone from being one of the most poorly disciplined in the Southern army to one of the best. The battalion lacked tents and many of the men had no blankets, forcing them to sleep “upon the naked ground without anything to be on or cover with.” Under such circumstances, some officers might have encouraged their men to scrounge what they needed from any available source. But McRae threatened to shoot “like a dog” anyone who so much as insulted a woman, much less committed theft. McRae apparently had charisma, for instead of resenting his high standards, his men developed pride in both themselves and their commander.47

Because McIntosh was functioning as McCulloch’s adjutant and de facto second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin T. Embry assumed command of the four hundred men of the Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles, although McIntosh directed their initial movements in person. Leaving their camp amid “a terrible fire of grape shot and shell,” they passed around Hébert’s and McRae’s units. Proceeding up the Wire Road toward the Ray farm, they moved just beyond the Pulaksi Light Battery and dismounted where a small patch of woods offered safety for their horses. The passage of the horsemen to the front caused some delay, which an irritated McCulloch took out on Hébert. Sergeant Willie H. Tunnard of the Pelican Rifles recalled that McCulloch galloped up to Hébert and, in a combination of excitement and rage, shouted, “Colonel, why in hell don’t you lead your men out?” The inquiry was not repeated and the regiment began to move, with McRae’s Battalion bringing up the rear. About the time they joined Embry’s men, either McCulloch or McIntosh ordered McRae’s Battalion up onto the ridge to their left to support Woodruff’s battery. The remaining two regiments, a total of some 1,100 officers and men, continued along the road.48

As Hébert’s and McIntosh’s men advanced, they passed through the impact zone of the Union counterbattery fire against Woodruff’s guns. The tree cover along the road provided only limited protection for the soldiers. After moving a short distance, the column turned left onto a narrow farm road that tunneled through thick underbrush, down into a ravine, at the bottom of which sat a springhouse used by the Ray family. As the soldiers in the lead climbed to the top of the steep bank beyond, they saw immediately in their front a weed-choked rail fence that marked the southern end of John Ray’s cornfield. They were shocked to discover Plummer’s men just on the other side.49

Only two companies of the Third Louisiana had time to deploy into line before the Federals opened fire. Hébert estimated the distance to be “within fifteen paces at the most.” Tunnard judged it to be less than a stone’s throw, and Watson recalled it as about one hundred yards. The differences probably reflect the men’s positions in line at the time. In any case, the bulk of the Confederates were still in column, and it may have taken twenty to thirty minutes for McIntosh to get all of his men into position. The rail fence was initially in between the contending soldiers, and some of the Louisianans sheltered themselves by crouching in the adjacent brush and thickets. Eventually, both the Third Louisiana and the Second Arkansas, which deployed to the left, pressed up to the fence and used it for cover. As they fought, “Sergeant,” a mongrel who had attached himself to the Louisianans and become their beloved mascot, ran barking down the line. Although the men tried to call him back to safety, he was killed almost instantly, “the victim of his own fearless temerity.”50

Although Plummer had his men kneel or lie down for protection, the Federals were at a decided disadvantage. There was considerable confusion because in places the weeds were so thick along the fence rails that the Southerners were effectively hidden. One of the Regulars remembered that “men frequently asked, ‘Where are they?’ ‘What do you see?’ We were guided mainly by the sound of musketry and the voices of men concealed in the dense thicket in front.” Another Federal recalled that although his unit “lay close to the ground,” four men were shot right next to him, as the Southerners “fired very low.” Indeed, only the fact that the Federals caught the Confederates in mid-deployment allowed them to maintain their position for as long as they did. Plummer apparently mistrusted the ability of the mounted Home Guard companies under Switzler and Wright, for he kept them to the rear. This meant that his line of only three hundred infantrymen was outnumbered more than three to one, but most of the Union soldiers performed well. Plummer paced back and forth behind his battalion, calling out words of encouragement such as “Keep cool, my boys, you are doing well, you are mowing them down!” Although he “attracted swarms of bullets,” he remained unscathed, and his courageous example had a calming effect. One of the Regulars confessed: “In the beginning we felt nervous and confused, like anyone suddenly exposed to danger; but we became warmed up with the excitement, and most of the men acted as if they had found an agreeable employment.” But they soon realized that the enemy did not constitute the only danger. “Quarrels broke out among the men, for those in the front complained that their cheeks were singed by the fire of companions in the rear rank; and ramrods which had been left on the ground were taken up by others and not promptly returned.” As was often the case in combat, many felt that the odds against them were even greater than they were. Private James H. Wiswell, a nineteen-year-old native of Washington County, New York, was one of the “rifle recruits” in Plummer’s battalion. In a letter to his sister Mary, he wrote that the Confederates were “in some brush adjoining the cornfield and commenced playing upon us and we played back a little smarter then they did according to our number.” He estimated that the Southerners to their front numbered 3,000 and thought that another three regiments were sent to turn their left flank, placing them in a “cross fire from nearly 6000 men.”51

Actually, elements of the Third Louisiana ended up on the Federals’ left flank not from any plan, but because there was not enough room. As each company deployed to the right of the previous one, they reached the eastern end of the cornfield and continued north until the Confederate line assumed the shape of an L. The casualties they incurred while getting into position were particularly distressing, as they could not yet retaliate. One member of the Pelican Rifles noted that his company lost a dozen men at the enemy’s first volley. According to Tunnard, “Men were dropping all along the line; it was becoming uncomfortably hot.” After several minutes, the smoke grew so thick that it obscured targets. Both sides ceased fire as if by mutual consent and the soldiers began to exchange taunts instead of bullets. One Federal, frustrated with his side’s poor position, challenged the Confederates to come out into the open field.52

Concerned about the rate at which his men were suffering casualties, McIntosh ended the lull by having his troops charge. He apparently gave the order to the Third Louisiana first, as he led the Second Arkansas in person. This was brave, but he would have done better to command from the rear, where he could exercise proper control. For as a result of some misunderstanding, only half of the Arkansans moved forward. But even with reduced numbers, the Confederate advance threatened to overwhelm Plummer, as approximately 900 cheering soldiers moved against his 300-man battalion. Despite his arthritis, Lieutenant Colonel Hyams of the Third Louisiana dismounted and followed his men on foot. The Federals did not panic, but their retreat was certainly rapid; despite the close proximity of the lines, only a few lingered long enough to participate in hand-to-hand combat. Bob Henderson, a private from Shreveport, Louisiana, was clubbed down by one Union soldier’s musket, but he recovered and shot the man who struck him in the back as he ran away. When Sergeant Watson attempted to seize a small flag from a Union officer, he received a sword cut to his wrist for his pains. “I closed with him, but found the poor fellow was already sorely wounded, and he fell fainting to the ground, still holding onto the flag.” Watson pressed on, following the fleeing Federals all the way into Gibson’s oat field. There McIntosh, his lines disorganized by the advance, halted to close ranks and take stock of the situation. About this time McIntosh resumed direct command of the Second Arkansas from Embry. This was only temporarily, for shortly thereafter McCulloch called McIntosh away to perform other duties and Embry led the troops throughout the rest of the day.53

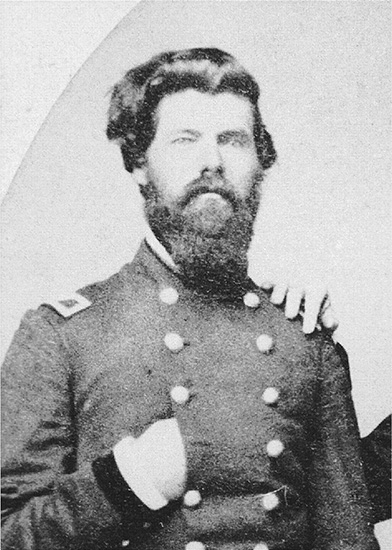

Captain Clark Wright, Dade County Union Home Guards (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

The Confederates had advanced well north of Gibson’s Mill, placing them in a position to threaten the left flank and rear of Lyon’s forces across Wilson Creek. They did not get an opportunity to do so. Over on Bloody Hill, Du Bois’s Battery had been assisting Totten’s gunners in delivering counterbattery fire. Captain Gordon Granger arrived with orders from Lyon to move the battery to the right. Du Bois was in the process of limbering the guns when he observed Plummer falling back through the cornfield. He thought that the “day seemed lost,” for the small battalion of Union Regulars was facing the “overwhelming force of the enemy.” Granger recognized the crisis as well, as he countermanded the move and ordered the Federal artillery to rake the exposed flank of McIntosh’s Confederates. A grateful Private Wiswell noted how “our batteries . . . began to throw ‘shell’ among them rather thick and thereby covered us in our retreat.” Plummer crossed back to the western side of Wilson Creek, taking the Home Guard horsemen with him.54

For the Third Louisiana, the experience of coming unexpectedly under artillery fire was psychologically devastating, even though it killed only two men out of a unit that at that point numbered more than six hundred. Watson remembered “a storm of shrapnel and grape,” whereas Tunnard recalled that “shot and shell were rained upon them until it became too uncomfortable to be withstood.” When Hébert ordered the regiment to fall back to the protection of some high wooded ground, the men obeyed “with zeal and alacrity.” Although not a rout, the withdrawal was highly disorganized, in part because many of the dispirited Louisianans threw themselves to the ground for safety whenever they heard a Federal artillery piece discharged. As a result, the regiment split into three groups during its retreat.55

Hébert rallied about one hundred of his command near the southern end of Ray’s cornfield, forming them into two companies. Major William F. Tunnard gathered a larger number in an open field behind the Ray house. This location was unexpectedly dangerous, as Tunnard’s men were the only enemy left in view of Du Bois’s gunners, who turned on the available target. Tunnard reported losing two men killed and several wounded before they moved behind the protection of a nearby hill. His command eventually rejoined Hébert, but not before a clumsy soldier in the Morehouse Fencibles accidentally discharged his musket, wounding three comrades.56

Firing from long distance, the Federals were unaware that the Ray home was being used as a field hospital because the Southern doctors had neglected to post the traditional yellow flag marking a medical facility. Once Tunnard’s group began to draw fire, the physicians promptly remedied the error and they were no longer targeted. The Ray house itself was never struck, although a nearby chicken coop was damaged.57

Sergeant Major J. P. Renwick, Morehouse Guards, Third Louisiana Infantry. Killed in the Ray cornfield fight, he was the regiment’s first casualty. (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Meanwhile, Hyams gathered the largest portion of the Third Louisiana near the ford of Wilson Creek on the Wire Road. As the men rested, Watson took time to bind his wound with the strip of white cloth that the Confederate troops wore around their left arms to distinguish themselves from the enemy. The Louisianans were joined by the Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles, which had withdrawn from the fight in much better order.58

Because reports did not always calculate losses on individual portions of the battlefield, the number of Confederates killed and wounded in the contest between McIntosh and Plummer cannot be determined precisely. Though Du Bois wrote that “the ground was covered with their dead,” he was too far away to make an accurate judgment. In all likelihood, the Southerners suffered about one hundred casualties.59 Plummer acknowledged nineteen killed, fifty-two wounded, and nine missing, or almost 27 percent of his total force. Although Plummer himself was among the wounded, having been struck during the retreat, he retained command and eventually re-formed his battalion in the ravine opposite Gibson’s Mill. There, unable to remain in the saddle, he turned command over to Captain Arch Houston. Except for part of Gilbert’s Company B, First U.S. Infantry, which moved forward and joined Steele’s battalion, Plummer’s command remained in reserve. The Home Guard companies under Switzler and Wright took up a position to guard against possible attempts by enemy cavalry to turn the Federal right and rear.60

The Confederates had defeated and driven an enemy column back across Wilson Creek and secured the northeastern section of the battlefield. This was a significant accomplishment, as it allowed McCulloch to concentrate on repelling Sigel’s attack from the south and assisting Price to the west. Although the fight in John Ray’s cornfield had been fierce and bloody, it had been relatively brief, lasting no more than about an hour. This would not be the case for the rest of the battle, especially on Bloody Hill.