Chapter 16

Come On, Caddo!

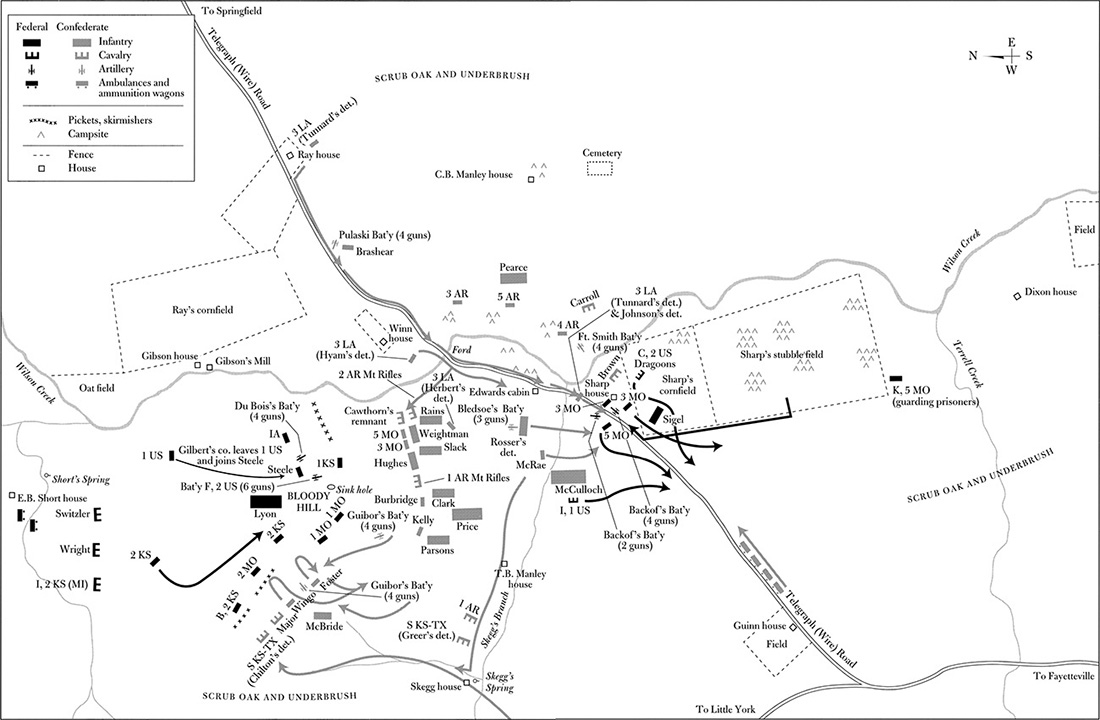

The Southern army’s commander was as anxious about Franz Sigel as Nathaniel Lyon was. After leaving Colonel McIntosh to handle the crisis in John Ray’s cornfield, Ben McCulloch rode down the Wire Road to determine the course of events at the Sharp farm. He apparently spent at least thirty minutes, until approximately 8:15 A.M., assessing the situation. What he observed must have been discouraging, for chaos reigned on the plateau where much of the Southern cavalry had camped at the beginning of the battle. While some of the horsemen were rallying near Wilson Creek and Bart Pearce’s Arkansas State Troops were well placed to challenge any crossing of Skegg’s Branch, Sigel had assumed a position across the Western Army’s line of communications. “Old Ben” did not require a West Point education to realize that this represented the worst possible development. He watched the Federals complete much of their maneuver before heading back up the Wire Road, searching for a way to deal with this new crisis.1

McCulloch had also witnessed how Sigel negated much of his previous accomplishment by deploying his force badly. The Federal commander placed the six pieces of Backof’s Missouri Light Artillery in the Sharp’s front yard, facing almost due north, to fire on the southern slope of Bloody Hill. The position was vulnerable, as some fifty yards to the front and right the plateau ended and the terrain dipped sharply toward Skegg’s Branch, creating a substantial “dead zone” that the Federal guns could not reach.2 Because the enemy might use this as a staging ground for a counterattack, the battery needed strong infantry support, including a heavy line of skirmishers to guard against surprise. But Sigel neglected these elemental precautions. He was apparently lulled into complacency by a steady stream of Southern stragglers who blundered into the Union lines and became prisoners. He placed only a single battalion of the Third Missouri, perhaps 250 men in all, in line to the right of the battery. Their selection was unusual, as they included some of the least experienced men in the brigade. The rest of the Third and all of the Fifth Missouri remained in reserve near the junction of the Wire Road and the farm road running along the western boundary of Sharp’s fields. Company K of the Fifth continued guarding prisoners, moving even farther to the rear.3

Sigel dismounted Captain Eugene Carr’s Company I, First U.S. Cavalry, to guard the left flank. The area it entered north of the Wire Road was wooded, and Carr repeated his error of earlier in the day by moving so deeply into the foliage that his men were beyond effective supporting distance. In fact, Carr soon lost all sense of direction. His men could no longer see, much less protect, the left flank of the battery. The other horsemen, Lieutenant Charles Farrand’s Company C, Second U.S. Dragoons, filed off to the right and rear, dismounting to take up a line within Sharp’s fences at or near the camp of Greer’s South Kansas-Texas Cavalry. As the Texans had encountered great difficulty exiting this area expeditiously, Farrand’s horsemen were not in the best position to respond quickly.4

The Federals in Sigel’s brigade had yet to suffer casualties. Having no immediate responsibilities, Dr. Samuel H. Melcher, assistant surgeon of the Fifth Missouri, rode over to the former Southern cavalry camp spread across Sharp’s fields. He discovered that some of the tents there used upended, bayoneted muskets for poles, the canvas being “caught in the flint lock.” Melcher and his orderly, Private Frank Ackoff, breakfasted on “coffee, biscuit and fried green corn” abandoned by their enemy. They also noticed a number of stragglers from the Missouri infantry who “set fire to some wagons and camp equipage.”5

Once his men were in position, Sigel ordered the artillery to shell units of the Missouri State Guard more than half a mile to the north. He assumed that they were part of the left flank of the forces facing Lyon. Despite the distance, the Southerners returned fire with both small arms and artillery. Their musket balls fell short, rattling the leaves and tree limbs above the heads of Carr’s advancing troopers without causing any harm. Many Southern artillery shells burst prematurely, adding to the cavalrymen’s discomfort but sparing the Federal gunners. When the enemy’s fire ceased after half an hour, Sigel halted his own. Identification was difficult at any sort of distance, and he was concerned about accidentally striking Lyon’s men on Bloody Hill. Whole squads of unarmed Southern soldiers approached via the Wire Road and surrendered as soon as they reached the plateau. Sigel also thought that he detected a large number of Southerners moving south along the ridges near the Manley farm, and he assumed that Lyon was driving the bulk of McCulloch’s army from the field in that direction. It was nearly 8:30 A.M. Events appeared to foretell a decisive Union victory, but for safety’s sake he ordered four of the artillery pieces shifted so that they faced up the Wire Road. The battery’s position was thus shaped almost like an inverted L. The battalion of the Third Missouri remained on the right flank, south of the Wire Road. Standing in its ranks, Private John Buegel wondered why, after such initial success, the Federals suddenly went on the defensive. “It was maddening,” he recalled.6

Bloody Hill and the Sharp farm, 7:30 A.M. to 8:45 A.M.

Despite Sigel’s confidence, the Federal column at the Sharp farm was in a perilous position, as thousands of enemy soldiers stood between it and Lyon’s forces stalled on Bloody Hill. Because of Sigel’s poor deployment, only four of Backof’s six guns and 250 infantrymen were positioned to defend against an attack coming from the Wire Road, the direction of the most likely danger. Sigel made no attempt to use his cavalry to contact Lyon, and he sent only a handful of skirmishers into the potentially dangerous blind ground to his front. He became completely passive at the very moment McCulloch was working to regain the initiative.7

Although more than two thousand of Pearce’s Arkansas State Troops had yet to see action, McCulloch decided not to use them against Sigel. His reasons are unclear. But as the reports that reached McCulloch regarding Sigel’s advance probably exaggerated the size of the Federal force, he may have wanted the Arkansans to remain on high ground, where they would have an advantage if attacked. Moreover, because Sigel had obviously moved around the Southerners’ eastern flank virtually undetected, McCulloch could not discount the possibility of yet a third enemy column approaching from due east, via the road leading to the Manley farm. If he moved Pearce’s men, an attack from that direction might penetrate far enough to threaten the rear of Sterling Price’s Missouri State Guard as it struggled to gain Bloody Hill. In any case, McCulloch made no major changes in their dispositions but went instead to check on the progress of McIntosh’s force, which he had earlier sent to fight Plummer in Ray’s cornfield.8

While moving toward his headquarters at the Winn farm, McCulloch encountered Lieutenant Colonel Hyams, who was near the Wire Road, rallying as many of the Third Louisiana as he could find. The Southerners who fought against Plummer in the Ray cornfield had become thoroughly disorganized in their flight from the Federal artillery fire. Hyams evidently informed McCulloch that, despite that retreat, the Southern right flank was secure. Free to concentrate on Sigel, and believing that there was not a moment to spare, McCulloch took command of the nearest two companies—the Pelican Rifles and the Iberville Grays—and started them across Wilson Creek. These were excellent troops. Because the Grays’ commander was absent, both companies were under the Pelicans’ own Captain John P. Vigilini, one of the most competent officers in the regiment. Sergeant Willie Tunnard recalled McCulloch encouraging them with the words, “Come, my brave lads, I have a battery for you to charge, and the day is ours!” Before leaving, McCulloch ordered Hyams to follow with the rest of the Louisianans as soon as possible. He also sent a messenger to McIntosh requesting all available support.9

Dr. Samuel H. Melcher, surgeon, who attended to Nathaniel Lyon’s body (The collection of Dr. Tom and Karen Sweeney, General Sweeny’s Museum, Republic, Missouri)

Hyams meanwhile struggled to re-form the Moorehouse Guards and Moorehouse Fencibles, the Winn Rifles, the Shreveport Rangers, and the two companies bearing the name Pelican Rangers. As they were lining up, Sergeant T. G. Walcott joined them with a few men from his company, the Monticello Rifles, as did about seventy members of the Missouri State Guard under a Captain Johnson.10 By the time they were ready to move out, McIntosh had arrived. He took charge of the column, hurrying it down the Wire Road. In retrospect, McIntosh might have done better to leave Hyams in command and remain behind to locate the missing portions of the Third Louisiana, which were still in the vicinity of the Ray farmhouse. But the wording of McCulloch’s message to McIntosh apparently stressed speed rather than numbers. As a result, fewer than four hundred men made the march. Much to McIntosh’s irritation, many of the Louisianans halted to fill their canteens from Wilson Creek. “The sun was now out bright and hot,” Sergeant William Watson recalled, “and the dust and smoke were stifling.” The men were so thirsty that they ignored the bodies of men and horses polluting the stream.11

When McCulloch led the two companies across Skegg’s Branch, the Federal skirmishers near there retired as they approached. Returning to the plateau, they reported that “Lyon’s men were coming up the road.” This was a grave mistake, of course, but Dr. Melcher, who had wandered in that direction, brought apparent confirmation. “It was smoky, and objects at a distance could not be seen very distinctly,” he observed. Nevertheless, when he saw “a body of men moving down the valley toward us,” he rode back and informed Sigel that they appeared to be one of Lyon’s regiments. He suggested that Sigel have the Stars and Stripes displayed conspicuously to avoid accidents.12

As both Dr. Melcher and the skirmishers withdrew from the “dead zone” in front of the Federal position without actually confirming the identity of the troops marching toward them, McCulloch was able to deploy not only his two companies but also all of the reinforcements under Hyams and McIntosh into line of battle without being observed. He was ably assisted by General Alexander Steen, drillmaster for the Missouri State Guard. Chronically ill, Steen was being “cupped” (a common medical procedure of the time) by one of the Missouri surgeons when the fighting began. Lacking a combat command, he probably spent some time reconnoitering Sigel’s position, as he was able to assist McCulloch by leading the Third Louisiana into position for the attack.13

While deploying the troops, McCulloch probably became aware of activity on his right flank by the Missouri State Guard. In response to Sigel’s fire on their rear, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas H. Rosser had assembled a force on the northern banks of Skegg’s Branch. This consisted of his own First Infantry, the Fourth Infantry under Lieutenant Colonel Walter Scott O’Kane, and Captain Hiram M. Bledsoe’s First Light Artillery, all of which were part of Rains’s Division. Sigel failed to notice these men, who completed their alignment just as McCulloch was ready to attack.14 McCulloch made no attempt to communicate with the Missourians or coordinate their actions with his own. Perhaps he believed that there was insufficient time to do so. In any case, he focused on positioning the Louisianans, whose assault he planned to lead in person. Like his foe Nathaniel Lyon, the former Texas Ranger forgot his responsibilities as an army commander. Caught up in the heat of battle, he concentrated on the placement of individual units. Tunnard noted McCulloch’s complete coolness and intense concentration. “His actions and features were a study for the closest scrutinizer of physiognomy,” the sergeant recalled. “Not a quiver on his face, not the movement of a muscle to betray anxiety or emotion. Only his grey eyes flashed forth from beneath his shaggy eyebrows a glittering, scrutinizing and penetrating glance.”15

At the Sharp farm, Sigel took pains to avoid friendly fire casualties. He cautioned the artillerymen not to engage the troops that would soon appear in their front. Colonel Charles Salomon warned his unit, the Fifth Missouri, while Lieutenant Colonel Anslem Albert carried a similar message to both battalions of his command, the Third Missouri. As an extra precaution, one of the Union color-bearers advanced and waved the national flag. Finally, Sigel dispatched a soldier from the Third Missouri to walk down the Wire Road and challenge any approaching troops. Sigel recalled that the man was a “Corporal Tod,” but records indicate he was Private Charles Todt of Company K.16

When Todt stepped into view, McCulloch ordered him to identify his unit. Todt obviously realized that he was facing the enemy, for after replying that he belonged to Sigel’s Union forces, he aimed his musket at the Southern commander. But he was not quick enough. A bullet fired by Corporal Henry H. Gentles of the Pelican Rifles saved the general, dropping Todt “without a groan.” McCulloch could hardly rebuke Gentles for firing without orders. “That was a good shot,” he said simply and turned to Vigilini, who stood at his side. “Captain, take your men up and give them hell.” McCulloch then moved to the left, passing the signal for the advance to the adjacent companies. When Lieutenant William A. Lacy of the Shreveport Rangers heard it, he leaped onto a log and waved his saber. “Come on, Caddo!” he shouted, his battle cry reminding his men that they represented Caddo Parish.17

McCulloch had apparently informed Vigilini that his men would be able to strike Sigel’s exposed right flank, as the Federal line had been facing north when McCulloch last observed it. The captain exercised discretion, nevertheless. When his men neared the rim of the plateau, he halted them and moved forward with Tunnard to see what lay beyond. “I was much surprised,” Vigilini recalled, “to find myself in front of and [within] about fifteen feet of the battery.” Instead of a flank attack, the Louisianans faced the prospect of charging directly into the muzzles of four enemy guns. Vigilini demanded the artillerymen identify themselves. If he meant this as a ploy to buy time, Tunnard spoiled it, for the sergeant cried out, “Look at their Dutch faces.” As the two Louisianans hastily withdrew, artillery fire erupted almost simultaneously from several directions.18

The Southern artillery actually fired first, for at this critical moment McCulloch received support from both the Arkansas State Troops and the Missouri State Guard. Throughout the early morning, Pearce had remained with Captain James Reid’s Fort Smith Light Battery on a hill above the Arkansans’ camps. He could not see the Sharp farm clearly, due in part to smoke drifting from the wagons burning in the fields, but he had no trouble detecting Sigel’s arrival at the Wire Road. Yet he did not open fire with his own artillery, even when the Federals began shelling Bloody Hill. Indeed, for more than thirty minutes after Sigel came into view, Pearce did nothing at all. He later insisted that the distance prevented him from knowing whether the force was friend or foe, but his explanation is hardly creditable. He could have sent Carroll’s Arkansas Cavalry Company to investigate, but these troops remained in a ravine. In any case, as the Southern army had neither infantry nor artillery at the Sharp farm prior to the battle, a force of such composition appearing there and firing on Bloody Hill could only be the enemy column that Southern fugitives had been reporting since shortly after dawn. Although McCulloch can be faulted for not making better use of the Arkansas State Troops, Pearce certainly did nothing to remind the army commander of their presence. He seems to have been content with a largely passive role.19

When Sigel’s color-bearer waved the U.S. flag in front of the Union position, Pearce finally ordered the Fort Smith battery to commence firing. By coincidence, Reid’s first shells exploded just as Vigilini and Tunnard scrambled back down the bank. Reid’s fire actually imperiled the Louisianans, as his guns were shooting over their heads and they were only yards from the Federals. In fact, it was probably a fragment from one of the Arkansans’ shells that wounded McCulloch’s horse at this time. Within moments, and also by happenstance rather than by design, Bledsoe’s First Light Artillery joined the fray and Rosser’s Missouri State Guardsmen surged forward. As Bledsoe’s three-gun battery was at an angle to McCulloch’s attack, its projectiles posed less danger of accidentally harming friends. Two of the guns from Backof’s Battery replied at once to the Southern onslaught.20

Battle having been joined, Vigilini quickly brought his two companies to the top of the plateau, where they fired into Sigel’s men at almost point-blank range. The remaining companies of the Third Louisiana, together with the Missourians under Captain Johnson, arrived right afterward and fired as well. McCulloch’s force was small, but he had concentrated superior power at the decisive point on the field. The Southern battle line was merely 400 yards long. But as a result of Sigel’s inept troop dispositions, they faced in their immediate front only four Federal artillery pieces and 250 men of the Third Missouri, who together occupied a front of only about 300 yards. More than a third of these Federals, most of whom were poorly trained recruits, probably became casualties to Southern musketry and artillery fire at the beginning of the struggle.21

Because they had been cautioned not to shoot at approaching friends, many of Federals believed that they were victims of mistaken identity. Just before the firing erupted, Farrand rode over from his position on the right flank, waving an Arkansas flag discovered by his dragoons. It is unclear whether he intended to consult with Sigel or simply wanted to present a trophy to him. Some feared that the Federal artillery on Bloody Hill, seeing this enemy banner, had concluded that Sigel’s men were Southerners. Melcher recalled, “The confusion was very great, many of the men saying ‘It is Totten’s battery! It is Totten’s battery!’”22 As neither army wore a standard color or style of uniform and Sigel’s men expected to link up with Lyon’s forces at some point, many also thought that the gray-clad Louisianans were members of the First Iowa, which possessed several companies wearing gray. Horrified by the apparent tragedy, Sigel lapsed into his native tongue, exclaiming “Sie haben gegen uns geschossen! Sie irrten sich!” or “They [are] firing against us; they [make] a mistake!”23 Similar cries, expressed in English, “spread like wildfire” through the ranks. Sigel recalled that the resulting “consternation and frightful confusion” nearly defied description.24

Sigel did not remain mystified for long, but even after realizing that the men shooting at him were Southerners, there was little he could do to save the situation. Some Federal soldiers returned fire, but others refused, continuing to believe that they faced friends. Colonel Salomon added to the confusion by filling the air with curses in German, English, and French. Any hope of the Federals making a stand evaporated when Rosser’s Missouri State Guard crested the plateau and struck their left. The Missourians had been forced to traverse rugged terrain on both sides of Skegg’s Branch to reach the Sharp farm, but because of the gap Carr left between his cavalry and the Federal infantry they faced no other impediments. They were joined soon afterward by a portion of Lieutenant Colonel Dandridge McRae’s undesignated battalion of Arkansas infantry. In response to McCulloch’s orders, McRae had shifted his Confederates from their initial assignment, supporting Woodruff’s Pulaski Light Battery, to join the assault on Sigel. During the movement a column of Southern horsemen cut across McRae’s path, dividing his unit into two columns. As the larger, rearmost group was delayed, only about 75 of McRae’s 220 men actually participated in the attack.25

Sigel exposed himself recklessly while attempting to rally his men, but the Federal brigade fell apart, despite the fact that it outnumbered its attackers three to one. The thin battle line crumbled and the survivors fled, abandoning the four guns and one of the caissons. Then this group of fugitives, led by three caissons driven at full gallop, ran into Sigel’s undeployed reserves. Although more than seven hundred strong, the Fifth Missouri and the remaining battalion of the Third could not fire without hitting their comrades. They panicked, dissolving into a mob with escape as its single goal. The two guns from Backof’s Battery that had been facing north barely had time to limber up and join the flight.26

It took the Southerners only a few minutes to gain complete control of the area around the Sharp house. The Louisianans quickly captured the four artillery pieces astride the Wire Road. One of these had been placed quite a distance to the rear of the others, perhaps so there was less of a gap between it and the two remaining guns facing north. The first Southerners to reach it were Corporal Henry H. Gentles, Corporal Thomas W. Hecox, and Private I. P. Hyams. A lone Union soldier, his name unknown, gave his life in a futile attempt to save the gun. At the same time, the left flank of the Southern line reached the northern border of Sharp’s fields and began firing at the retreating enemy. It was soon joined by the companies that captured the battery. The Federals put up little resistance in their flight, although one of their parting shots mortally wounded Hecox. Unluckily, Reid’s distant Fort Smith Battery mistook the rapidly advancing Louisianans for the enemy. Before the error was discovered, a shell exploded in the ranks of the Moorehouse Guards. Captain R. M. Hinson (the noblest gentleman and bravest soldier in the regiment, according to his commander) was killed as he cheered his men on. His brother-in-law, Private E. A. Whetstone, died at his side, and several others were wounded.27

Because of the continuing crisis on Bloody Hill, the Southerners did not make a coordinated pursuit of the Federals. When Pearce saw that a portion of the enemy was heading back toward the Dixon farm, he sent the Fourth Arkansas Infantry, commanded by Colonel Frank Rector, along the ridges overlooking Wilson Creek as a precaution. Joined by three companies from Colonel Tom Dockery’s Fifth Arkansas Infantry, the force eventually occupied a position near the point where Sigel’s guns had fired their first shots, but it saw no action. After the missing portion of McRae’s Battalion reached the Sharp farm, its commander moved his men a short distance along the Wire Road in response to reports that the enemy had rallied. Finding no one, they returned and took no further part in the battle.28

Other Southern units moved more quickly, but the Federals proved hard to catch. Some simply scattered. Private Buegel and three comrades ran cross-country, making their way independently back to Springfield. But most retreated in groups. Sigel, part of the Third Missouri, one piece of artillery, and several wagons headed south on the road leading to the Dixon farm, returning the way the column had entered the battlefield. The other gun, additional wagons, and all but a handful of the remaining Federal infantry fled southwest along the Wire Road. Colonel Salomon was the highest-ranking officer among those who went in this direction. Because of their positions, the Federal horsemen on the flanks were the last to leave. While both followed the Wire Road, they did so separately.29

The Federals fleeing along the Wire Road fell into several groups. The first consisted of Colonel Salomon and the Fifth Infantry, which had not fired a shot and had probably suffered few casualties. These men, about four hundred strong, moved quickly out of harm’s way, crossing a wooded hill and descending into a slight valley formed by an unnamed tributary of Terrell Creek. Here they encountered a Southern baggage train making its way toward the Western Army’s camp in blissful ignorance of the day’s events. At the sight of the Federals the wagoneers promptly wheeled about to make their escape. Fortunately for them, Salomon’s infantry was not interested in pursuit. After climbing a small rise, the Federals halted at a farm owned by a family named Guinn. There they captured Dr. R. B. Smith, who identified himself as a surgeon from Rains’s Division of the Missouri State Guard. His reason for being at the Guinn place is unknown, but after Dr. Melcher intervened he was released. The two physicians then rode back up the Wire Road, where they joined other doctors on the field, treating both Union and Southern casualties without regard to their affiliation. Salomon resumed his march after only the briefest pause. His group turned right onto the Little York Road and made its way to Springfield without incident.30

The second group departing via the Wire Road initially consisted of 150 “badly demoralized” infantry from both the Third and Fifth Missouri and one of the guns from Backof’s Battery. They had not gone far before they were joined by Carr’s cavalrymen. The captain had been ignorant of the disaster that had overtaken Sigel’s brigade until a staff officer located him in the woods and ordered him to retreat. The dragoons lost no time in doing so, forming an impromptu rear guard for the infantry and gun. As they approached the Guinn farm, a volley tore into the column’s flank from a bushy hillside on the right. This fire killed one of the wheelhorses drawing the gun and wounded another. In the ensuing confusion of tangled horses, the tongue of the limber drawing the gun broke. Carr’s men returned fire, driving away the men who had ambushed them, but they decided to abandon the artillery. In their haste to get away, they passed by the junction of the Wire and Little York Roads. Instead of turning right toward Springfield, as Salomon had, they continued south.31

Farrand’s dragoons were the final group to exit by way of the Wire Road. Dismounted behind the fences in Sharp’s cornfield, they had watched helplessly as their comrades ran away. Although they were initially handicapped by their commander’s absence, the real problem was their location. They were well placed to repel an attack against their front, but when danger appeared on their left they could not reposition themselves in time to affect the course of events. When Farrand returned, he ordered them to retreat. In some disorder, but ostensibly without panic, they crossed Sharp’s fields and headed southwest into the woods. They went only about half a mile, just over the rise south of the Sharp farm. On the way Farrand encountered and forcibly detained A. D. Crenshaw, one of the civilians who had guided Sigel’s brigade on its march to the battlefield. Farrand had no idea how to get back to Springfield in a westerly direction, and he had no desire to take chances.32

After gathering his horsemen and few stray Union soldiers who had also found safety in the woods, Farrand moved west until he reached the Wire Road. Almost immediately he discovered the artillery piece abandoned by Carr’s group. After cutting the dead and wounded horses from the traces of the limber, Farrand moved on, taking the gun with him. In a short time, the faster-moving riders began to leave the infantry behind. Farrand apparently never considered deploying some of his dragoons as skirmishers for a rear guard. Instead, he rode ahead of the entire party, accompanied by three men. Near the Guinn farm they discovered a caisson fully stocked with ammunition. It had obviously been left behind because several of the horses were wounded. Farrand decided to salvage this as well. Removing the wounded horses proved to be a difficult task, probably because the pain-stricken animals were skittish and uncooperative. As his small party worked, the dragoons passed by and the infantry caught up. Farrand recalled that he “tried to prevail upon some of the Germans to assist us . . . but they would not stop.” Perhaps they resented the fact that Farrand had done nothing to provide for their safety. In any case, Farrand eventually got the caisson under way, using “a pair of very small mules” that they probably stole from the Guinns. Soon the entire group turned right onto the Little York Road. It was almost to Springfield when some of the horses pulling the gun gave out. Farrand was forced to destroy the caisson and hitch its animals to the more valuable artillery piece. Once back in Springfield, he worked with Lieutenant Samuel Morris, an officer on Sigel’s staff, to send wagons to the battlefield to remove the wounded.33

Sigel accompanied the members of the Third Missouri who sped down the road leading back toward the Dixon farm. This meant they passed across the rear of Farrand’s dragoons while the dismounted horsemen were still in the northeastern corner of Sharp’s fields. As some point, perhaps near the Dixon farm itself, Sigel halted and took stock of his situation. After organizing the remnant of his brigade, which consisted of some 250 men and one gun, into four makeshift companies, he proceeded west. The column, which also contained some wagons, apparently followed a farm road that ran in that direction from the Dixon place, meeting the Wire Road about two miles south of the Sharp farm. Here the Federals turned right, heading back toward the battlefield. They hoped to join the other, larger group of fugitives and return to Springfield via the Little York Road, which joined the Wire Road a mile ahead. After traveling only about half a mile, the Federals encountered Carr’s party of men at Moody’s Springs, where the Wire Road crossed Terrell Creek.34

When Carr stated that his group had been attacked during their flight, Sigel decided to retrace his steps. The now-enlarged column moved south, looking for a road running east that would take it to Springfield. “So we marched, or rather dragged along as fast as the exhausted men could go,” Sigel later wrote. This time he took no chances with security. Carr “was instructed to remain in the advance, keeping his flankers out, and report whatever might occur in front.” The artillery was positioned near the head of the infantry column, “the whole flanked on each side by skirmishers.” They had gone no more than a mile and a half when good and bad fortune confronted them simultaneously. At the moment they reached the turnoff for a road back to Springfield, Carr’s scouts spotted a large body of enemy cavalry farther down the Wire Road.35

Once the Federals turned left, safety lay in speed, yet Sigel did not redeploy Carr’s cavalrymen as skirmishers at the crossroads to delay the enemy’s pursuit. His reason for not doing so remains unknown. Carr not only retained the lead, he apparently concluded that the column was doomed and it would be better to save part of it than see it all die together. He refused to slow his horsemen to the pace of the tired infantry. His explanation, given in his later report, was astonishingly candid and self-centered. “Colonel Sigel asked me to march slowly, so that the infantry could keep up,” Carr wrote. “I urged upon him that the enemy would try to cut us off in crossing Wilson’s Creek, and that the infantry and artillery should at least march as fast as the ordinary walk of my horses. He assented, and told me to go on, which I did at a walk, and upon arriving at a creek I was much surprised and pained to find that he was not up.” After watering his horses, Carr moved on. Although he paused again farther along the road, he sent no one back to investigate the fate of his comrades-in-arms. After waiting a few moments, he proceeded to Springfield.36

As one might imagine, Sigel was not pleased with Carr’s actions. When the artillery and infantrymen finally reached the creek, they were surprised that Carr was not waiting for them. One company of infantry crossed without incident, but while the gun and caissons were in midpassage, shots rang out from both banks. The Federals had lost the race.37

The Southerners’ success in trapping Sigel came more from happenstance than design. When McCulloch witnessed the Federals’ flight from the Sharp farm, his primary concern was for the baggage wagons that he knew were en route to the Western Army’s camp. He therefore ordered Colonel Elkanah Greer to send two companies from his South Kansas-Texas Cavalry in pursuit. Greer selected Captain Hinchie P. Mabry’s Deadshot Rangers and Captain Jonathan Russell’s Cypress Guards. They were joined along the way by Lieutenant Colonel James Major with the Windsor Guards, a cavalry unit from Clark’s Division of the Missouri State Guard. As senior officer present, Major took charge of the command, which numbered about three hundred men. They rode south along the Wire Road without incident until they saw, off in the distance, Sigel’s men turning left to head back to Springfield.38

The Federals failed to detect Major’s approach, as they were focused on the horsemen Carr had just discovered to the south. These were men from Colonel William Brown’s Cavalry of Parsons’s Division. It is not clear who gave them their assignment. Led by a Captain Staples, they numbered perhaps one hundred men and were divided into three groups. Staples had a cavalry battalion of his own, a Captain Alexander commanded another, and there was a battalion of mounted infantry under Captain Charles L. Crews. When the Federals first fled from the Sharp farm, Staples’s force had pursued them, firing into Carr’s flank and causing him to abandon his artillery piece. Instead of seizing the gun, Staples took his men through the woods, worked around Carr’s flank, and finally blocked the Wire Road in his front. The Southerners naturally concluded that this action forced Sigel to detour to the east, when actually the Federals had been seeking a route in that direction all along. After the Federals left the Wire Road, Staples’s men began to ride around their flank once more, while Major’s command closed on their rear. Although Carr managed to cross Wilson Creek safely near its junction with the James River, Staples reached the ford before Sigel and set up an ambush.39

The fight that ensued was brief but decisive. The odds were even—about 400 men on each side—but the demoralized Federals were caught by surprise for the second time that day. Staples’s fire pinned them down at the ford. When Major’s men arrived moments later and charged, the Federals scattered. Most fled toward Springfield, and a running fight developed that covered three miles of ground. There were many acts of individual courage, for Major himself testified that “General Sigel and his men fought with desperation.” The outcome was never in doubt, however, and the Federals who escaped did so individually. Many were rounded up throughout the day, as the Southerners scoured the countryside for fugitives. Together, Major and Staples took 147 prisoners, including Lieutenant Colonel Anslem Albert. They also captured several wagons, the gun from Backof’s Battery, and the colors of the Third Missouri. They reported finding 64 enemy bodies, but the actual total was probably higher. For example, 4 Union soldiers were discovered nearby at Nowlan’s Mill, hiding in the space where the water rushed over the mill dam. When they refused to come out, they were blasted with shotguns. Southern losses were negligible.40

The Southerners last saw Sigel when he dashed into a field and disappeared among the rows of corn. At some point during the fight Sigel had decided that discretion was the better part of valor. Before galloping off, he concealed his rank by wrapping a wool blanket about his shoulders. He and another soldier were chased for six miles before they eluded their pursuers. Sigel had a good horse and he was probably the first non-wounded soldier who fought at Wilson’s Creek to return to Springfield.41